Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIT’s and Centrelink’s1 administration of TFES.

[1] From 1 July 2011, Centrelink became a master program within DHS.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government has provided financial assistance to shippers of freight between Tasmania and mainland Australia under the Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme (TFES, or the Scheme) since July 1976. The Scheme aims to assist in alleviating the sea freight cost disadvantage incurred by shippers1 of eligible non-bulk2 goods moved between Tasmania and the mainland of Australia by sea. The Scheme's objective is to:

... provide Tasmanian industries with equal opportunities to compete in mainland markets, recognising that unlike their mainland counterparts, Tasmanian shippers do not have the option of transporting goods interstate by road or rail.3

2. TFES is an executive scheme established under the Ministerial Directions for the Operation of the Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme of the Minister for Infrastructure and Transport. The Ministerial Directions establish the structure of the program’s various components, the eligibility criteria for claimants and goods, and the parameters used to determine the levels of assistance provided for different freight scenarios.

3. The administration of the Scheme is shared between the Department of Infrastructure and Transport (DIT) and the Department of Human Services (DHS).4 Between 2002 and 2011, this arrangement was established in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the then Department of Transport and Regional Services (DOTARS, now DIT) and Centrelink.5 In August 2011, DHS and DIT signed a new Head Agreement.6 DIT (as the principal agency for the Scheme) is responsible for policy formulation and advice, and for the overall management of the program. DHS (as DIT’s agent) is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the Scheme, which it delivers, through Centrelink, as part of the Tasmanian Transport Programs (comprising TFES, the Tasmanian Wheat Freight Scheme and the Bass Strait Passenger Vehicle Equalisation Scheme). Specifically, Centrelink assesses claims for TFES assistance, makes payments to eligible claimants, and conducts a number of quality assurance, compliance and review activities designed to support payment accuracy.

4. The Scheme is demand driven, and while an annual budget is set for the total assistance available for claimants, in practice there is no upper limit to the total annual payments that could be made to claimants. In 2010–11 the budget for the Scheme was $114.4 million. The combined forward estimate for the Scheme over the four years to 2013–14 is $485.6 million.

5. In 2010-11, Centrelink received $1 million (including GST) in revenue from DIT to deliver the Tasmanian Transport Programs.7 The Tasmanian Transport Programs are delivered by a team of Centrelink officers located in Hobart, with support from Centrelink National Office in Canberra for program and relationship management issues with DIT. The number of team members has varied between 10 and 20 over time. Support is also provided by an IT development and maintenance team within National Office.

TFES eligibility and claiming rules

6. TFES comprises three components (northbound, southbound and intrastate8 sea freight), and three special categories (sports persons, professional entertainers and brood mares). All claimants are required to submit a claim form containing up to 17 fields of information relating to the goods shipped, and the majority of claimants must also attach supporting freight documentation to their claim forms. Some claimants must also register their businesses and the goods for which they wish to make a claim before a claim may be submitted.

7. The eligibility criteria and payment calculations for the Scheme are complex, reflecting the large number of variables that could affect the level of freight disadvantage facing Bass Strait shippers. Separate program components cover the payment of freight assistance depending on the source and destination of the relevant goods. Each of these components establishes different eligibility requirements for claimants and for goods, and these requirements also affect the level of assistance that may be paid to eligible claimants. Factors taken into consideration when determining whether a particular claimant is eligible for assistance include:

- the type of goods, including whether the goods are ‘high density’9 refrigerated, or transported in a packaged or loose form;

- the origin and end use of the goods, with particular rules for the mining, agriculture, forestry and fishing industries; and

- the destination of the goods, including whether goods will be transported to other Australian states, exported overseas or returned to Tasmania.

TFES claimant and claim profile

8. In 2010-11, 1544 businesses and individuals lodged a total of 11 233 claims for assistance under the Scheme, resulting in the payment of a total of $100 million to eligible claimants. Three industries - the food and beverage industry; the agriculture, forestry and fishing industry; and the wood and paper industry - constitute the largest groups of claimants both in terms of amount of assistance received and number of claimants accessing the Scheme.

9. The number of claims paid has increased steadily between 2004-05 (6377 claims paid) and 2009-10 (12 929 claims paid). Concurrently, the average amount of assistance paid per claim has decreased significantly, from approximately $14 000 in 2004-05 to $7735 in 2009-10. These figures reflect that, while the number of claimants and claims has been progressively increasing, the value of the claims submitted has been, on average, lower than in previous years. These two factors combined to lower the overall average value of claims over this period. There has been a small reversal in 2010-11, with the number of claims paid dropping slightly to 10 094, and the average claim value rising to $9907.

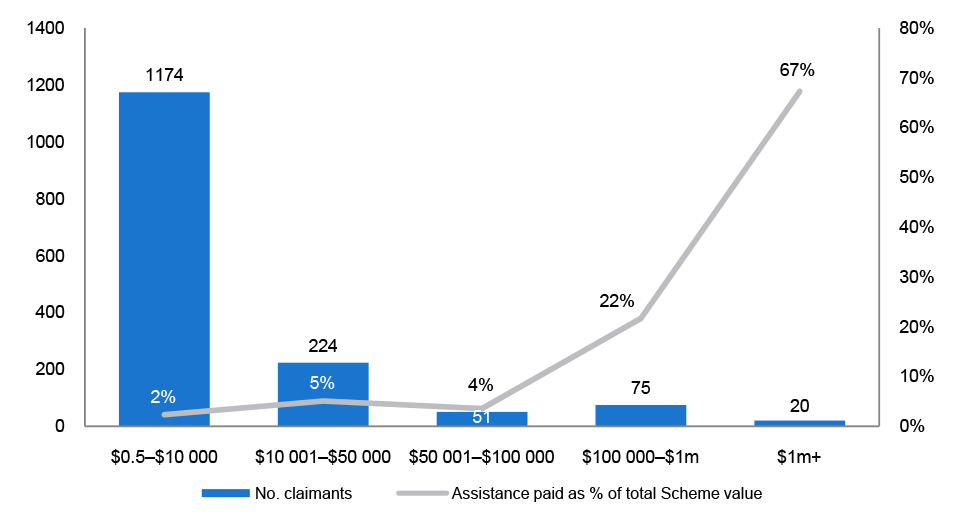

10. The amount of assistance paid varies greatly between claimants (Figure S.1). In 2010-11, the largest annual total of assistance paid to a single claimant was $15.2 million, and the smallest annual total was 54 cents. A small number of claimants receive the majority of assistance paid under the Scheme. In 2010-11, one per cent of claimants (20 claimants) received 67 per cent of the total value of the assistance paid under the Scheme, with an average claim value of $3.4 million. Five of these 20 claimants, all businesses from the food and beverage industry, received in total $32.5 million of the $100 million paid under the Scheme in 2010-11.

Figure S.1: Distribution of TFES assistance, 2010-11

Source: ANAO analysis

Recent reviews of the Scheme

11. There have been a number of reviews of the processes underlying the Scheme’s administration, and of the parameters used to determine eligibility and payment amounts for each component. In 2006, a review conducted by the Productivity Commission concluded that ‘there [was] no sound underlying economic rationale for the Scheme’ and that the Scheme was affected by ‘significant design and operational problems'.10 Following the Australian Government’s decision that the Scheme would continue unchanged, the Productivity Commission made a series of recommendations aimed at improving the rules for claiming TFES payments and the overall administration of the Scheme.

12. In 2008, to address one of the Productivity Commission's recommendations, the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) reviewed the Scheme’s assessment and payment methodology, making a number of suggestions to update the Scheme’s parameters.11 The Australian Government subsequently announced that it considered that ‘adjustments to the parameters would significantly reduce overall assistance levels resulting in a significant negative impact on Tasmanian businesses at a time of global financial uncertainty’12, and decided to maintain the existing levels of assistance by continuing to use the parameters that were set in 1996-97.13

13. In late 2010, DIT commenced a review to identify opportunities to simplify the Scheme. The ’Simplification Review’ was used to inform advice provided by DIT to its Minister in February 2011 to prepare for the 2011–12 Federal Budget. The advice indicated that:

- the purpose and Ministerial Directions for the Scheme are dated after 35 years of operation leading to the potential that payments are made to those who are not the intended beneficiaries;

- TFES complexity contributes to errors in assessing eligibility and payments; [and]

- large numbers of claims attract very small payments.14

14. The advice also included a number of recommendations to simplify the Scheme and address the issues identified during the Simplification Review. Nevertheless, no ministerial decisions have subsequently been made in relation to potential changes to the structure of the Scheme’s components or to the parameters used to determine eligibility and payment amounts. The Scheme’s funding levels were also maintained in 2010-11.

Audit objective and scope

15. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIT’s and Centrelink’s15 administration of TFES.

16. The audit scope included the arrangements established by DIT and Centrelink to administer the Scheme, including activities to promote claimant access, and to assess and pay the claims submitted by claimants. The audit also examined the program management arrangements established by the two agencies to support the delivery of the Scheme. The agencies’ systems and processes were assessed in terms of three high-level audit criteria:

- the Scheme is accessible to eligible claimants;

- claims are assessed and paid in a transparent, accurate and timely manner; and

- program management arrangements (including evaluation, reporting and monitoring activities) support the delivery of the Scheme.

Overall conclusion

17. After more than 30 years of operation, the Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme (TFES, or the Scheme) is a well-established program in the Tasmanian economy, providing a total of $100 million in assistance to 1544 claimants in 2010-11. For a range of businesses and individuals, the Scheme plays an important role subsidising the cost of sea freight. Over time, TFES’ operating rules and the parameters used to determine eligibility and assistance payments have become more complex. Multiple reviews have recommended simplification in order to remove some of the main design and operational complexities and to improve the administration of the Scheme. While some changes have been made to the Scheme’s operational arrangements, successive governments have decided to retain the underlying rules and parameters without change since 1998. A further review of the Scheme has been announced for 2011-12.

18. As a small industry support program, TFES is fundamentally different to the large social welfare programs typically administered by Centrelink. Accordingly, Centrelink, in collaboration with DIT, established distinct arrangements to administer the Scheme. While these arrangements have been reasonably effective in facilitating access to the Scheme for claimants, there are shortcomings in several key areas of program administration, which include the absence of a risk-based approach to claims processing, limitations in the compliance and quality assurance arrangements, and weaknesses in the management of claimants and claims information and in the monitoring of TFES IT data integrity.

19. Between 2004–05 and 2010–11, the number of TFES claims has increased by 58 per cent, and the number of claimants by 19 per cent. This, together with the Scheme’s longevity and widespread recognition among relevant stakeholders, point positively to the Scheme’s accessibility. Several hundred of these new claimants have engaged a third party organisation to apply for assistance on their behalf on a fee-for-service or commission basis. While clearly reflecting business decisions on the part of these claimants, this development is also an indication of the complexity of the Scheme’s arrangements. The increase in the number of claims and claimants has also affected the timeliness of TFES claims processing. Between July 2009 and June 2011, Centrelink met their monthly 15 and 30 days processing targets only nine times. Claim processing timeliness was an area of focus for questioning of departmental officers from DIT and Centrelink during several relevant Senate Estimates hearings in 2009 and 2010. DIT’s one-off increase to Centrelink’s operational budget, and Centrelink’s work to reduce a backlog of claims, have resulted in a significant improvement in the time taken to process claims, with the number of claims processed in less than 15 days increasing from 57 per cent to 79 per cent between 2009-10 and 2010-11.

20. The Scheme’s internal appeal and review mechanisms are appropriate and operating effectively, and in March 2011, Centrelink established a system to receive feedback from claimants, including complaints. There is scope for more effective communication with program stakeholders about current appeal and review arrangements. This includes the need to highlight that a two-tier Centrelink-DIT review process is in place, and to make clear to claimants that they are entitled to seek a review by the Commonwealth Ombudsman following a decision by Centrelink or DIT.

21. At the time of audit fieldwork, Centrelink’s approach to the assessment of claims was characterised by time- and labour-intensive processes which gave equal attention to all claims. As a result, most of Centrelink’s operational budget was directed toward managing claims that represented only a small fraction of the Scheme’s overall financial risk. Further, Centrelink did not have a systematic approach in place to check and update key information used to support the accuracy of claims assessments and payment calculations. Centrelink had also implemented a pre-payment quality assurance process, but did not analyse the results of this process in order to identify systemic issues and inform business management decisions. Centrelink’s post-payment processes to monitor and report on payment accuracy were also limited, and the compliance activities for the Scheme were restricted and not fully effective.

22. In August 2011, DHS and DIT signed a new Head Agreement, replacing an earlier Memorandum of Understanding first signed in 2002. The Head Agreement took into account this audit’s preliminary findings, establishing more clearly the framework of responsibilities and expectations for the delivery of TFES. Nonetheless, some important elements of program administration are not covered in the new Agreement, or are left open to future improvements and modifications. To help ensure that the benefits anticipated by the new Agreement are fully realised, both agencies will need to maintain the momentum necessary to pursue the development and implementation of changes in these areas.

23. To support the agencies’s efforts to make ongoing improvements to administration arrangements for TFES, the audit has made three recommendations. These recommendations concern improving the accuracy of information used to calculate payments; strengthening quality assurance activities; and developing more effective integrity testing arrangements for the Staff Online system.

Key findings

Claimants’ access to the Scheme and rights of review (Chapter 2)

24. As DIT’s agent under the terms of the Head Agreement, Centrelink (now DHS) has primary responsibility for providing the public and potential claimants with access to information about TFES, and uses its website as the main channel to promote TFES. Centrelink also conducted a small number of site visits aimed at helping specific claimants lodge their claims. Although promotion and stakeholder activities have decreased in frequency and diversity over time, overall, the longevity of the Scheme has created a high level of awareness among relevant Tasmanian businesses and industries.

25. A survey conducted by the ANAO of a sample of TFES claimants16 revealed good levels of satisfaction with Centrelink’s customer service and with claimants’ knowledge about the Scheme’s eligibility requirements. Nonetheless, the survey also pointed to the need for greater transparency of payment calculation, with a large proportion (40 per cent) of respondents indicating that they had difficulties understanding TFES payment calculations.

26. An indicator of the Scheme’s complexity, and of the extent to which this complexity is reflected in the arrangements for making TFES claims, is the emergence of a third party organisation that makes claims for TFES assistance on behalf of eligible businesses and individuals on a fee-for-service or commission basis. An analysis of claims data indicates that the activities of the third party organisation resulted in a 16 per cent increase in the number of TFES claimants between 2007–08 and 2009–10. In 2010–11, this organisation was also the largest claimant in terms of number of claims paid (30 per cent of all claims that year) and the second largest claimant in terms of assistance paid (representing nine per cent of the value of assistance paid through the Scheme that year).

27. DIT and Centrelink had implemented appropriate internal appeal and review mechanisms (including providing claimants with opportunities for more than one review of any decision). In March 2011, Centrelink established a formal mechanism to receive claimants’ feedback, including complaints, and the new 2011 Agreement between DHS and DIT requires DHS to report to DIT on the number and type of customer complaints. There is scope to provide more comprehensive advice to TFES claimants about current review and appeal arrangements, and to highlight claimants’ right to seek a review by the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

28. Between July 2009 and June 2011, Centrelink met its monthly timeliness Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) less than half the time (nine months out of 24). The time taken by Centrelink to process claims, and the potential impact of inconsistent processing and payment times on businesses, were raised as issues through relevant Senate Estimates hearings in 2009 and 2010, the media, direct representations to the agencies and in the TFES claimants survey conducted by the ANAO. Centrelink largely attributed the backlog to the year-on-year increase in the number of TFES claims between 2004–05 and 2009–10. A decrease in the number of claims in 2010–11, and a one-off increase to Centrelink’s operational budget for administering the Scheme that year, impacted positively on Centrelink’s timeliness performance.

Processing claims for assistance (Chapter 3)

29. Under the terms of the Head Agreement, DHS, through Centrelink, has primary responsibility for the processing of claims, including assessment and payment activities. TFES is a scheme with a set of complex eligibility and claiming requirements, covering a large and diverse range of goods, businesses and individuals, and comprising several distinct components to which different rules apply. For the major components of the Scheme, Centrelink has implemented standardised claiming requirements and processes for claimants. While some claimants undertake a pre-claiming business registration process, all claimants are required to submit the same shipment information using a single form and there are minimal variations in the claiming requirements to access TFES assistance.

30. Since 2009, Centrelink has been using a new IT system called Staff Online to process TFES claims, which automatically calculates the assistance payable for each shipment and the total assistance for each claim.17 Staff Online (and other separate databases) also stores extensive information relating to particular goods and businesses, mostly based on information provided by claimants over the years. This stored data provides an essential repository of knowledge that assessors can draw upon when assessing the amount of assistance to be paid.

31. While the IT system provides essential support to assessors, Centrelink’s approach to assessing TFES claims remains focused on processes that involve extensive manual upfront checks and verification of claim and claimant information. Almost all claims are captured within this time- and resource-intensive process, which relies heavily on the experience of assessors, on the claimants’; vigilance, and on the accuracy of the goods and businesses information kept on file by Centrelink. Using out-of-date or incorrect goods and businesses information has a direct impact on the accuracy of claim assessments and the amount of assistance payable. Nonetheless, until August 2011, there was no systematic process in place to ensure that the information kept on file about goods and businesses remained current.

32. While the new Head Agreement introduces a provision to review some of this information every 12 or 24 months, in the absence of an implementation plan, the intended impact of this provision may not be realised in a timely fashion. Also, as the relevant provision only relates to some of the information held in databases that is required for the calculation of assistance, it only partially mitigates the risk that out-of-date or incorrect information will affect payment accuracy. There is scope for DIT and Centrelink to develop a more effective, risk-based approach to identifying the TFES information held in relevant databases and on file that could substantially affect payment accuracy, and to reviewing and updating this information.

Calculating and paying assistance (Chapter 4)

33. Agencies providing assistance under Australian Government programs seek to calculate and pay accurate amounts to eligible claimants. However, it is likely that a number of payments will be assessed and paid incorrectly, as a result of either administrative or customer errors. In addition to implementing measures to keep pre-payment errors to a minimum (including quality assurance activities), agencies must also develop risk-based post-payment administrative processes to monitor and report on payment accuracy, and to detect and recover incorrect payments. For TFES, the responsibility for the calculation and delivery of accurate payments lies with Centrelink. Nonetheless, DIT remains accountable for the quality of the program and for making effective use of Commonwealth resources.

34. While Centrelink implements a pre-payment quality assurance process, the individual results are only used to manage assessors’; performance, and do not create an incentive to identify or resolve inaccurate payments. Based on the analysis of the quality assurance results, the ANAO identified that between nine and 19 per cent of all TFES claim assessments are likely to contain a critical error.18 Such analysis is not conducted by Centrelink and, consequently, is not used to identify systemic issues and inform business management decisions.

35. Post-payment, Centrelink relied on three mechanisms to detect incorrect payments: compliance activities; assessors’; vigilance in the course of their work; and claimants’; self-reporting. Centrelink recorded the individual incorrect payments thus identified on Staff Online, but until August 2011, did not monitor, analyse or report on identified incorrect payments.19

36. These mechanisms, combined, did not provide enough confidence that all substantial incorrect payments could be identified: compliance activities were limited, not always effective and did not target the areas of highest financial exposure; and Centrelink did not provide the support and incentives that would have ensured assessors’; and claimants’; effective contribution to the detection and reporting of incorrect payments. Further, claimants are not necessarily in a strong position to identify and report errors: the ANAO’s survey of claimants identified that only 27 per cent of respondents agreed that understanding how TFES payments are calculated is easy. Centrelink also did not always implement appropriate rules when entering and managing data relating to incorrect payments on Staff Online, and did not conduct routine data integrity checks to identify anomalies in data recording. Consequently, while the number and value of identified incorrect payments for 2009–10 and 2010–11 remained at modest levels (less than two per cent of total assistance paid annually), tightening the review and compliance processes would help Centrelink improve its confidence in the integrity of payments made under TFES.

37. Once Centrelink’s officers have assessed and entered the claims data on Staff Online, the system automatically applies the parameters and formula prescribed by the Scheme’s Ministerial Directions to calculate the amount of assistance payable. This amount is then transferred to Centrelink’s payment system Infolink, before being forwarded to the claimants’; bank account. The tests conducted by the ANAO provided a level of confidence that the parameters and formula built into Staff Online were correct and consistent with the Ministerial Directions.20 The 2009–10 and 2010-11 TFES payments had also been correctly transferred from Staff Online to Infolink.

Program management arrangements (Chapter 5)

38. As previously discussed, DIT is the agency with primary policy responsibility for the Tasmanian Transport Programs, including TFES, and Centrelink (now DHS) operates as DIT’s agent. However, key aspects of the Scheme’s design and delivery can only be changed with the approval of the Australian Government. While this arrangement limits the capacity of either agency to make significant reforms to program delivery arrangements, both agencies should continue to explore opportunities to make incremental improvements within these parameters to improve the overall performance of the Scheme.

39. Negotiations for an agreement updating the responsibilities for TFES administration had been ongoing between DIT and Centrelink since 2009. The new Head Agreement signed by DHS and DIT in August 2011 takes into consideration the ANAO’s preliminary audit findings, and establishes a number of key mechanisms that were either absent or not fully successful, in the previous MoU, in ensuring that TFES was delivered in a fully effective and accountable manner. These new mechanisms include improved management information and change management requirements, a framework for a risk-based management of compliance activities, an assurance framework and new or revised KPIs.

40. While the new Agreement represents a valuable instrument establishing more clearly the framework of responsibilities and expectations for the delivery of TFES, the document is presented as a ‘work in progress’ and a number of important features of program administration are not covered in the changes described in the Agreement or are left open to future improvements and modifications. The effectiveness of the changes set out in the Agreement will be heavily dependent on the agencies’; commitment to maintaining the momentum required to pursue the implementation and further development of the Agreement. While a date of review of the Head Agreement is scheduled for three years after the commencement date, the Quarterly Business Meetings set out in the new Agreement should represent a useful means of assessing progress towards the Agreement’s objectives.

41. Until November 2011, there was no overarching risk-based compliance strategy for the administration of TFES. The compliance activities conducted for TFES were limited in their scope and effectiveness: two of the activities identified by DIT and Centrelink as compliance activities were better defined as reports on claimants’; self-declarations, thus presenting some inherent limitations with respect to the level of assurance provided; two other compliance activities were either not fully effective at detecting non-compliance, covered a limited number of claimants and claims, or did not target areas generating the higher financial exposure.

42. The 2011 Agreement states that DHS and DIT would endeavour to reach an agreement on a full risk-based compliance strategy within 60 days of signing of the Head Agreement and to vary the Agreement to reflect the strategy.21 Keeping in mind that compliance activities need to be commensurate with the size, characteristics and available operational budget, this strategy should better position DIT and DHS to deploy the Scheme’s limited resources more effectively and ensure that greater emphasis is given to those areas presenting the greatest financial risk. DIT provided a draft compliance strategy to the ANAO on 4 November 2011, and DIT and DHS indicated their commitment to finalise the document by mid-November 2011. The ANAO was not able to review the draft compliance strategy or verify that DIT and DHS had met their timeframe before the publication of this report.

43. Prior to the new Head Agreement, TFES’ performance was monitored mostly through KPIs set out in the MoU between DIT and Centrelink.22 The extent to which the agencies reported and achieved these KPIs was variable. The main internal report on TFES’; operations, the monthly report provided to DIT by Centrelink, was not sufficiently comprehensive to effectively monitor performance and review overall progress and trends. The Head Agreement sets the framework for improved monitoring and reporting of TFES and should, once the tasks required to finalise the KPIs are completed, help the agencies gain a higher level of confidence that the Scheme is delivered effectively and that accountability measures are in place.

Summary of agency response

The Department of Infrastructure and Transport (DIT)

44. DIT provided the following summary comment to the audit report:

The Department of Infrastructure and Transport (DIT) notes the findings and recommendations made in the ANAO’s audit of the Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme. DIT commenced work to implement the recommendations during the audit and this work remains an ongoing focus. The Department accepts the recommendations (which were directed at the Department with the Department of Human Services). The Department supports improvements to the compliance and quality assurance processes. Consistent with the recommendation by the ANAO, the Department with DHS, has worked to establish a compliance strategy as part of it management of the Scheme.

DIT's full comments are included at Appendix 1 of the report.

The Department of Human Services (DHS)

45. DHS provided the following summary comment to the audit report:

The Department of Human Services welcomes this report and considers that implementation of its recommendations will enhance the administration of the Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme. The Department of Human Services agrees with the recommendations in the report.

DHS’s full comments are included at Appendix 1 of the report.

Footnotes

[1] Shippers or claimants are companies and individuals that incur the costs of shipping eligible goods.

[2] Goods that have some form of unitisation or packaging and that are not shipped loose in a ship’s hold or tanks.

[3] Department of Infrastructure and Transport website, <http://www.infrastructure.gov.au/transport/programs/maritime/tasmanian/scheme.aspx> [accessed 28 March 2011].

[4] In July 2011, the Human Services Legislation Amendment Act 2011 integrated the services of Medicare Australia and Centrelink into DHS. In this report, references to Centrelink’s activities prior to July 2011 are references to Centrelink as an agency. References to Centrelink’s activities after July 2011 are references to the activities of DHS, through the Centrelink program.

[5] Centrelink and the Department of Transport and Regional Services, Memorandum of Understanding between Centrelink and DOTARS, August 2002.

[6] Department of Human Services and Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Head Agreement between DHS and DIT, 19 August 2011.

[7] In addition, a one-off funding of $220 000 (GST inclusive) was provided in the last quarter of 2010–11 by DIT to Centrelink to eliminate the backlog of claims. Centrelink has also received $1.6 million from DIT since 2007–08 for the development and maintenance of a new IT system, Staff Online (see Glossary).

[8] ‘Intrastate’ freight refers to freight between the main island of Tasmania and either King Island or the Furneaux Group. The Furneaux Group is a group of more than 50 islands situated in the eastern Bass Strait, of which Flinders Island is the largest.

[9] High density or heavy cargo which when efficiently packed has a stowage factor of 1.1 cubic metre or less per tonne. Volume is a more important cost consideration for sea freight than weight.

[10] The inquiry covered TFES and the Tasmanian Wheat Freight Scheme. Tasmanian Freight Subsidy Arrangements, Productivity Commission Inquiry Report No. 39, 14 December 2006, pp. iv and xxii.

[11] BITRE, Tasmanian Freight Scheme Parameter Review, Department of Infrastructure and Transport, 2008.

[12] Hon Anthony Albanese MP, Freight Subsidy Schemes to Continue Ongoing Financial Assistance for Tasmanian Industry, Media Release, 6 November 2008, <http://www.minister.infrastructure.gov.au/aa/releases/2008/ November/AA164_2008.aspx> [accessed 6 April 2011].

[13] BITRE completed another parameter review in November 2010, and reiterated that the sea freight disadvantage had decreased for many Bass Strait shippers due to the increase in road freight rates. The parameter review also suggested that, in this context, TFES parameters should be updated but that consequently, payments to most shippers would be significantly reduced. BITRE, Tasmanian Freight Scheme Parameter Review, Department of Infrastructure and Transport, November 2010, p. v (unpublished).

[14] Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Tasmanian Freight Equalisation Scheme – ANAO Audit, Scheme and Parameter Review and MoU with Centrelink, eWorks number 00380-2011, February 2011.

[15] From 1 July 2011, Centrelink became a master program within DHS.

[16] In March 2011, the ANAO sent an email survey to 925 TFES claimants. Two hundred and twenty-five claimants (28 per cent of all surveyed) responded to the survey.

[17] A single claim can include multiple shipments eligible for assistance.

[18] Critical errors are defined by Centrelink/DHS as having the potential to have a material impact on the assistance calculation and the assistance paid to the claimant.

[19] The new Head Agreement between DHS and DIT now requires DHS to report on over- and underpayments.

[20] In order to gain full assurance of the accuracy of the formulas developed in the database, a comprehensive review would need to be conducted within the database programming language. This was not within the scope of the audit.

[21] Department of Human Services and Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Head Agreement between DHS and DIT, 19 August 2011, Services Schedule 3, Subsection 1.3.

[22] Memorandum of Understanding between Centrelink and the Department of Transport and Regional Services, August 2002.