Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Supporting Good Governance in Indigenous Corporations

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) supports good governance in Indigenous corporations consistent with the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Indigenous groups seeking to gain the benefits of incorporation can generally choose between incorporating under mainstream Commonwealth or state and territory legislation or under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) Act 2006 (CATSI Act), which is regulated by the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC). As at May 2017, there were 2910 Indigenous corporations registered under the CATSI Act, which is estimated to represent over a third of incorporated Indigenous organisations in Australia.

2. ORIC’s primary responsibilities are:

- maintaining public registers to support the transparency and accountability of Indigenous corporations;

- monitoring and enforcing Indigenous corporations’ compliance with the accountability and governance requirements of the CATSI Act; and

- supporting good governance in Indigenous corporations through providing information, advice and education.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess whether ORIC supports good governance in Indigenous corporations consistent with the CATSI Act.

4. To form a conclusion on the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Does ORIC maintain registers in accordance with relevant requirements?

- Does ORIC effectively monitor and enforce compliance with the CATSI Act?

- Does ORIC provide effective information, advice and education?

Conclusion

5. ORIC supports good governance in Indigenous corporations by maintaining public registers, monitoring and enforcing compliance, and providing information, advice and education, consistent with the CATSI Act.

6. In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains registers on its website that provide information to stakeholders on the status and operation of Indigenous corporations and officers who are disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation. The ANAO found: minor data quality issues with the Register of Indigenous Corporations; and procedural issues with the registration of new corporations and the Register of Disqualified Officers. ORIC recently instituted a quality assurance framework that is intended to address data quality issues with its corporations register database. ORIC currently exchanges data with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission. There is scope for ORIC to explore data exchange arrangements with other corporate regulators.

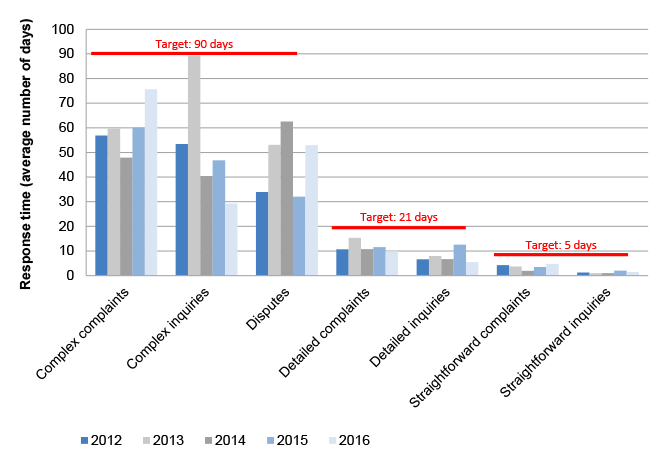

7. ORIC’s ongoing focus on Indigenous corporations’ compliance with annual reporting requirements has led to a significant improvement in reporting response rates for Indigenous corporations over the past decade. It has also undertaken successful civil and criminal proceedings against officers of Indigenous corporations. ORIC’s other regulatory interventions include conducting examinations and special administrations.1 While internal data suggest these interventions are relatively successful, ORIC could employ a more structured approach to risk profiling corporations so as to better target its examinations. ORIC publishes data on its regulatory activities in an annual yearbook, but in recent years it has not committed to, or reported against, regulatory performance targets.

8. ORIC produces a range of useful guidance materials and templates, provides well-received training courses and has established other free services to support good governance in Indigenous corporations. While ORIC’s provision of information and advice to stakeholders meets internal timeliness benchmarks, it could improve its performance measures and commit to external performance targets. ORIC has introduced a quality assurance program and has some internal processes to ensure the consistency and accuracy of its information and advice. It no longer seeks structured feedback from stakeholders on its support services to promote continuous improvement.

Supporting findings

Maintaining public registers

9. In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains a database of information and documents relating to the Register of Indigenous Corporations. It makes relevant material from this database available publicly on its website, which provides transparent information to stakeholders about the status and operation of Indigenous corporations. The ANAO found minor data quality issues in the register database. ORIC has recently established a quality assurance process for the register database, which is intended to improve data quality over time.

10. ORIC has an established process and procedural guidance for staff assessing applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation. There is scope to improve guidance to better support staff in the exercise of their decision-making responsibilities.

11. In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains a Register of Disqualified Officers, which is publicly accessible on its website. However, ORIC does not have adequate procedures to ensure persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are promptly listed on the register following disqualification and required documents are stored on its register database.

12. ORIC has an established data exchange arrangement with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, which minimises reporting burden on Indigenous corporations. There is scope for ORIC to explore options for establishing data exchange arrangements with Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Australian Financial Security Authority and/or the Australian Taxation Office.

Monitoring and enforcing compliance

13. ORIC’s ongoing emphasis on monitoring and enforcing Indigenous corporations’ compliance with annual reporting requirements has achieved a significant improvement in reporting response rates over the past decade. It also conducts an annual rolling program of routine examinations to monitor large, essential or publicly funded corporations, which frequently identifies compliance issues that trigger further regulatory action.

14. ORIC can generate risk ratings for corporations in its corporations register database, but due to limitations with the methodology these ratings provide limited value to ORIC’s regulatory program. While ORIC considers various matters in targeting its examinations, it does not systematically analyse the outcomes of interventions to improve its regulatory strategy.

15. ORIC’s program of special administrations has returned a majority (around 90 per cent) of Indigenous corporations to members’ control, and the majority of these corporations (more than 90 per cent) have not subsequently been deregistered. These outcomes suggest the program is well targeted and leads to more sustainable Indigenous corporations.

16. ORIC has initiated enforcement action, including civil proceedings and criminal prosecutions for breaches of the CATSI Act. The majority (around 95 per cent) of criminal prosecutions initiated by ORIC have been for breaches of annual reporting requirements by Indigenous corporations; an approach that has contributed to ORIC’s high rates of reporting response rates. ORIC’s other criminal prosecutions and civil proceedings relate to the behaviour of officers of Indigenous corporations, and have resulted in disqualification, fines and, in some cases, imprisonment.

17. ORIC has internal regulatory performance targets, against which it monitors progress. It also publishes performance information in its annual yearbook. However, in recent years ORIC has not committed to external performance targets. In response to a recent review and the preliminary findings of this audit, ORIC developed a revised suite of corporate documents.

18. ORIC is covered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s policy and procedures on conflicts of interest, which requires ORIC to maintain a register of any real or perceived conflicts of interest identified by its staff.

Providing information, advice and education

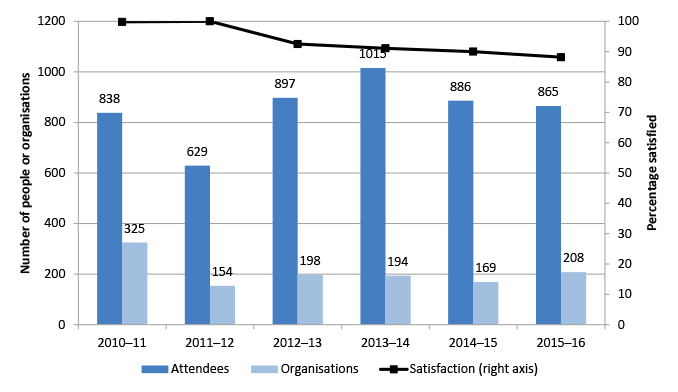

19. ORIC provides a range of useful guidance materials and templates to support registered Indigenous corporations and groups considering incorporating under the CATSI Act. Its education and training program provides free training in corporate governance to a large number of individuals and corporations and achieves high satisfaction levels. It has also established free services to assist corporations with recruitment and legal advice.

20. ORIC receives around 6000 requests for information and advice per year, most of which are straightforward inquiries to which it responds promptly. The majority of its more complex requests, including handling of complaints and disputes relating to Indigenous corporations, are completed within benchmark timeframes. ORIC does not commit to performance targets in its client service charter.

21. ORIC’s recently established quality assurance program includes an assessment of records relating to information and advice provided to stakeholders. It has developed processes to promote consistency and accuracy in its responses.

22. ORIC previously conducted a client survey, which provided structured feedback on its support services. ORIC does not currently seek structured feedback from its stakeholders on the guidance and templates on its website or the information and advice provided by its staff.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.18

ORIC should review and update its guidance and procedures for assessing applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.28

ORIC should establish procedures to ensure that persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are promptly listed on the Register of Disqualified Officers, relevant documents are stored on the register, and such disqualified persons do not continue to hold the positions of director or secretary in Indigenous corporations.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.25

ORIC should refine its risk rating system in ERICCA to better support its regulatory program.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

23. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations’ response appears in Appendix 1 of this report. A summary of the response is below:

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (the department) and the Office of the Registrar of lndigenous Corporations (ORIC) welcome the audit report and the ANAO’s overall conclusion that ORIC supports good governance in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations consistent with the intent of the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act). The department and ORIC agree to the three recommendations made by the ANAO.

ORIC has already taken action to implement the recommendations.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Incorporation enables groups engaging in business activities to establish a separate legal entity that can: limit the personal liability of members; remain the same despite changes in membership; acquire, hold and dispose of property; incur debt; and sue and be sued. Indigenous groups seeking to form business entities can generally choose between establishing:

- a proprietary or public company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act)—regulated by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC);

- an incorporated association or cooperative under state and territory legislation—regulated by fair trading, consumer or business services agencies in each state and territory; or

- an Indigenous corporation under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) Act 2006 (CATSI Act)—regulated by the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC).

1.2 Indigenous groups holding or managing native title under the Native Title Act 1993 and Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 must incorporate under the CATSI Act. In addition, since 1 July 2014, Indigenous groups receiving grant funding of $500,000 (GST exclusive) or more in a single financial year from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet may be required as condition of funding to incorporate under the CATSI Act.

1.3 As at May 2017, there were 2910 Indigenous corporations registered under the CATSI Act. While it is difficult to measure how many Indigenous groups have chosen to incorporate under the Corporations Act or state and territory legislation2, ORIC has estimated the total number of incorporated Indigenous organisations in Australia to be between 6000 and 90003—meaning Indigenous corporations registered under the CATSI Act represent over a third of incorporated Indigenous organisations.

History of Indigenous corporations legislation

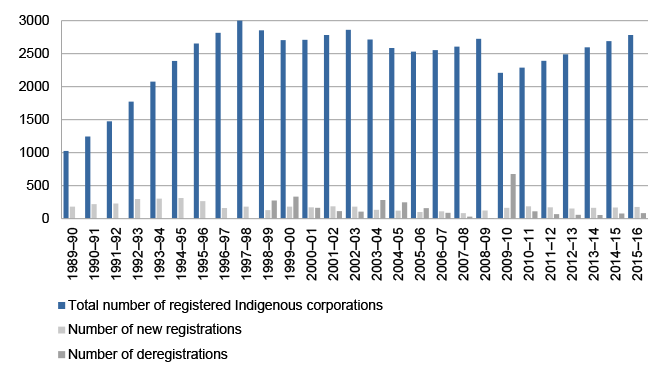

1.4 The first Indigenous corporations legislation, the Aboriginal Councils and Associations Act 1976 (the ACA Act), commenced on 14 July 1978. The number of registered Indigenous corporations under the ACA Act increased steadily during the 1980s and 1990s, reaching a peak of 2999 corporations in 1997–98 (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Registered Indigenous corporations 1989–90 to 2015–16

Source: ORIC, Yearbook 2007–08 & Yearbook 2015–16.

1.5 Following a 2002 review that recommended comprehensive legislative reform, the ACA Act was replaced by the CATSI Act from 1 July 2007. The CATSI Act was designed to ‘[maximise] alignment with the Corporations Act where practicable, but [provide] sufficient flexibility for corporations to accommodate specific cultural practices and tailoring to reflect the particular needs and circumstances of individual groups’.4 Special features of incorporation under the CATSI Act, which were developed to promote flexibility and meet the specific needs of Indigenous groups, are outlined in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Special features of CATSI Act incorporation |

|

Support functions: ORIC’s functions, established under section 658-1 of the CATSI Act, include supporting good governance in registered corporations through providing advice and public education, assisting corporations with disputes and complaints, and conducting research. Special powers: The CATSI Act provides ORIC with special powers to intervene in a corporation’s affairs, including powers to convene meetings, change a corporation’s rule book, direct a corporation to change its name, or conduct an examination of its books. Special administration: When an Indigenous corporation is at risk of failure, ORIC can appoint a special administrator to take control of the corporation. Special administration differs from ordinary administration under the Corporations Act in that its primary objective is returning the corporation to its members rather than protecting the interests of creditors. |

Role of Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations

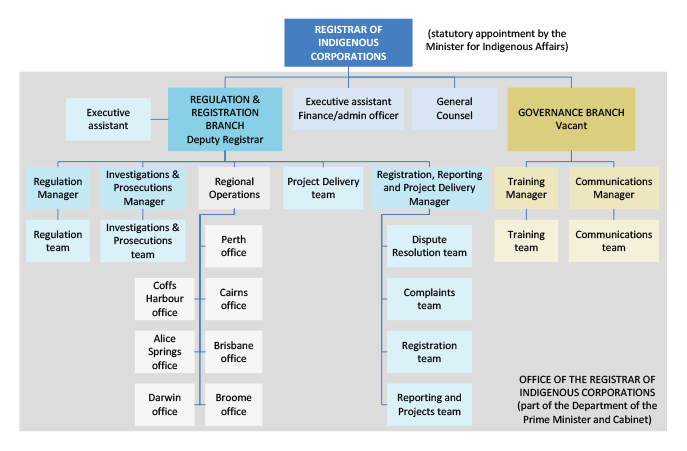

1.6 The Registrar of Indigenous Corporations5 is an independent statutory office holder appointed under the CATSI Act by the Minister for Indigenous Affairs. The Registrar is supported by ORIC, whose staff are employed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. ORIC’s staffing structure is set out at Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Structure of ORIC

Source: ORIC internal organisation chart (as at February 2017).

1.7 During 2015–16, ORIC had a budget of $8.38 million and 46.6 full-time equivalent staff. While the majority of ORIC’s staff are based in Canberra, it maintains a small network of out-posted officers across seven of the Department’s regional offices (Perth, Coffs Harbour, Cairns, Brisbane, Alice Springs, Darwin and Broome).

1.8 ORIC’s primary responsibilities are:

- maintaining public registers to support the transparency and accountability of Indigenous corporations;

- monitoring and enforcing Indigenous corporations’ compliance with the accountability and governance requirements of the CATSI Act; and

- supporting good governance in Indigenous corporations through providing information, advice and education.

Key functions that ORIC undertakes relating to these responsibilities are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Key functions undertaken by ORIC

|

Maintaining public registers |

Monitoring and enforcing compliance |

Providing information, advice and education |

|

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of ORIC information.

Profile of registered Indigenous corporations

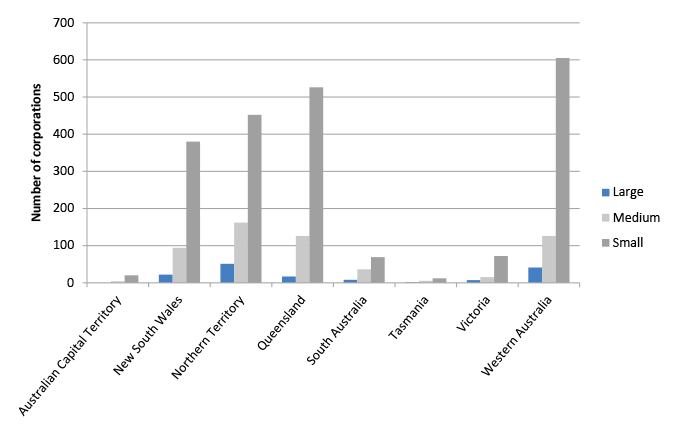

1.9 Under the CATSI Act, to determine reporting and structural requirements, an Indigenous corporation is registered as ‘small’, ‘medium’ or ‘large’ based on its annual operating income, assets and number of employees.6 Table 1.2 outlines the current criteria for classifying corporation size, as prescribed in the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) Regulations 2007 (CATSI Regulations). As Figure 1.3 illustrates, the majority (74.9 per cent) of registered Indigenous corporations are small; 147 corporations (5.2 per cent) are currently classified as large. Geographically, Indigenous corporations are primarily based in Western Australia, Queensland, the Northern Territory and New South Wales.

Table 1.2: Criteria for large, medium and small corporations

|

Criteriaa |

Corporation size |

||

|

Small |

Medium |

Large |

|

|

Consolidated gross operating income (in last financial year) |

< $100,000 |

$100,000 – $4,999,999 |

≥ $5,000,000 |

|

Value of consolidated gross assets (at end of financial year) |

< $100,000 |

$100,000 – $2,499,999 |

≥ $2,500,000 |

|

Number of employees (at end of financial year) |

< 5 |

5 – 24 |

≥ 25 |

Note a: A corporation is classified as small, medium or large if it meets at least two criteria for that category.

Source: CATSI Act, CATSI Regulations.

Figure 1.3: Number of Indigenous corporations by size and location

Source: ANAO analysis of ORIC data.

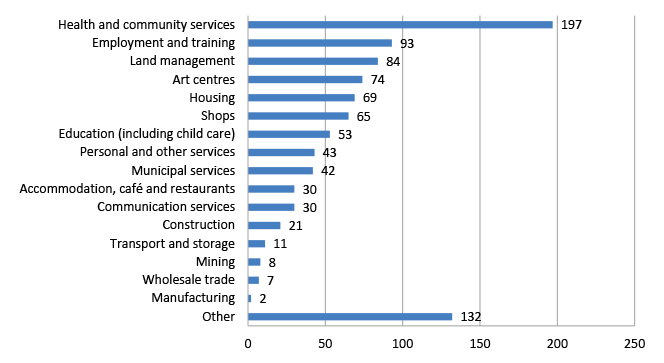

1.10 Figure 1.4 provides a breakdown of the sectors in which the top 500 Indigenous corporations operate. In 2014–15, the top 500 Indigenous corporations had a combined income of $1.88 billion, assets of $2.22 billion, and employed 11,095 full-time equivalent staff.7 In 2014–15, 43 per cent of the top 20 Indigenous corporations’ income was self-generated, 39.3 per cent was from government funding and 17.7 per cent was from other sources.8

Figure 1.4: Number of top 500 Indigenous corporations by sector, 2014–15a

Note a: Totals by sector do not add to 500 as some corporations operate across multiple sectors.

Source: ORIC, The top 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations 2014–15.

Audit approach

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess whether ORIC supports good governance in Indigenous Corporations consistent with the CATSI Act.

1.12 To form a conclusion on the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Does ORIC maintain registers in accordance with relevant requirements?

- Does ORIC effectively monitor and enforce compliance with the CATSI Act?

- Does ORIC provide effective information, advice and education?

1.13 The audit method included: reviewing relevant documentation, systems and processes; analysing ORIC data; examining a sample of records to assess compliance with procedural requirements; and interviewing relevant stakeholders. In addition, the ANAO sought feedback from registered Indigenous corporations and received 21 submissions.

1.14 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $336,000.

1.15 The team members for this audit were Daniel Whyte, Matthew Birmingham and Deborah Jackson.

2. Maintaining public registers

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether ORIC maintains public registers in accordance with relevant requirements.

Conclusion

In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains registers on its website that provide information to stakeholders on the status and operation of Indigenous corporations and officers who are disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation. The ANAO found: minor data quality issues with the Register of Indigenous Corporations; and procedural issues with the registration of new corporations and the Register of Disqualified Officers. ORIC recently instituted a quality assurance framework that is intended to address data quality issues with its corporations register database. ORIC currently exchanges data with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission. There is scope for ORIC to explore data exchange arrangements with other corporate regulators.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at establishing consistent procedures for registration of new corporations and updating the Register of Disqualified Officers.

Does ORIC maintain a Register of Indigenous Corporations in accordance with requirements?

In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains a database of information and documents relating to the Register of Indigenous Corporations. It makes relevant material from this database available publicly on its website, which provides transparent information to stakeholders about the status and operation of Indigenous corporations. The ANAO found minor data quality issues in the register database. ORIC has recently established a quality assurance process for the register database, which is intended to improve data quality over time.

2.1 The CATSI Act requires ORIC to maintain a Register of Indigenous Corporations, which contains information and documents relating to the registration of Indigenous corporations (including corporations that have been deregistered). While the CATSI Act and CATSI Regulations specify the types of information that should be held and what information can be obtained by the public, they do not prescribe the form the register should take.

2.2 ORIC stores information and documents relating to the register, along with internal records relating to its advice and compliance functions, in a database called the Electronic Register of Indigenous Corporations under the CATSI Act (ERICCA). It makes information and documents from ERICCA, other than exempt documents, available to the public via a searchable interface on its website.9

2.3 Maintaining the quality of data held in its corporations register is central to ORIC’s statutory aims of facilitating and improving the performance and accountability of Indigenous corporations and providing certainty to stakeholders. Consequently, it is important that ORIC has appropriate quality assurance processes in place to ensure the accuracy and currency of the information stored in ERICCA and published on its website.

Quality assurance of ERICCA data

2.4 While ERICCA has a series of automated checks, built-in prompts and review steps to support data quality, much of the data in ERICCA is entered manually by ORIC staff, or by Indigenous corporations submitting forms electronically, which introduces potential for data entry errors.10 ORIC undertakes some recurring business processes that support data quality, such as verifying financial data recorded in ERICCA in preparing its annual report on the top 500 Indigenous corporations, running various tests for anomalous data, and holding regular training sessions for staff prior to annual reporting periods.

2.5 ORIC identified data quality in ERICCA as a weakness in 2011. It established a quality assurance program in March 2012, but ORIC informed the ANAO that this was discontinued after a few months as it was over engineered for an entity of ORIC’s size.

2.6 ORIC’s internal business plan for 2015–16 identified ‘[increasing] the quality of public register documents, correspondence and internal record keeping’ as a key internal priority. In May 2016, ORIC adopted a ‘Quality assurance and accountability framework’, which includes:

- monthly manual checking of ERICCA tasks, focussing on obvious errors and omissions;

- monthly authentication tests and exception reporting of data entered into ERICCA;

- an internal email account for reporting errors, omissions and inaccuracies;

- monthly reporting to senior managers on assessment results; and

- an annual review of the quality assurance system.

2.7 Manual checking of a five per cent sample of tasks during the first six months of the quality assurance program found an average error rate of 23.7 per cent, which falls outside ORIC’s acceptable error rate of 5 per cent. ORIC defines ‘errors’ for its internal reporting as issues ranging from typographical errors and incorrect formatting through to exemptions not being recorded, forms not being signed, or documents not being published to the public register. ORIC does not categorise these errors by severity in its monthly reporting.

2.8 Authentication testing focuses on very specific types of errors that can be checked electronically: invalid email, physical or mailing addresses; document registration details; and breaches of certain requirements relating to directors (a majority of directors must be Indigenous and corporations cannot have more than twelve directors unless their rule book allows this).11 It is performed on all database entries and has found low error rates of between 0 and 3.59 per cent over the first six months, which fall inside ORIC’s acceptable error rate of 5 per cent.

2.9 To identify broader errors with existing corporation records stored in ERICCA, ORIC relies on staff or users of the online register reporting them, and the annual reporting process from corporations, which involves providing updated details of addresses, officers and members. ERICCA has been in use since 2007, so the error rate in the manual testing results (23.7 per cent for new tasks since August 2016) suggests there are likely to be data quality issues with existing records in ERICCA.

2.10 The ANAO reviewed ERICCA records12 and found: incorrect incorporation dates for two Indigenous corporations; five registered Indigenous corporations without an associated registered office address or document access address (a CATSI Act requirement); incorrect date of birth records (for example, directors born in 1838, 1858 and 2016); and data entry errors with annual returns records.

2.11 Following feedback from stakeholders about inconsistencies and errors in ORIC-initiated corporation rule books, ORIC has also initiated a project to review rule books. As at April 2017, this project was still in its early stages, so the ANAO has not reviewed its progress.

2.12 The quality assurance framework and rule book review project are positive developments. Errors are being corrected as they are discovered, which improves data quality. ORIC’s quality assurance framework includes a commitment to provide refresher training for staff on required standards, templates and key processes, which should help to reduce error rates over time. To provide greater assurance of the quality of information stored on its corporations register, ORIC should consider analysing and classifying errors by severity and undertaking broader corrective action where there is a high risk of incorrect information being published on the public register.

Does ORIC appropriately assess applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation?

ORIC has an established process and procedural guidance for staff assessing applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation. There is scope to improve guidance to better support staff in the exercise of their decision-making responsibilities.

2.13 Prior to registering an organisation as an Indigenous corporation, the CATSI Act requires ORIC to assess compliance with a series of basic requirements. The processes ORIC undertakes upon receipt of an application for registration under the CATSI Act are outlined at Figure 2.1. ORIC has discretion to grant an application for registration if some of the basic requirements (such as the minimum number of members and age of members requirements) are not met; however, it must not grant an application if a corporation would not meet:

- the Indigeneity requirement—at least 51 per cent of members must be Indigenous;

- the internal governance rules requirement—a ‘rule book’ must be submitted that includes certain mandatory rules and meets other requirements (such as being in English, internally consistent, and providing adequate coverage of replaceable rules);

- the name requirement—the corporation name must clearly indicate that it is an Indigenous corporation and meet other rules (such as being unique, inoffensive and not including restricted words, phrases or abbreviations).

Figure 2.1: Processing applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation

Source: ANAO analysis of ORIC internal procedures.

2.14 During 2016, ORIC received 212 applications for registration—as at 20 April 2017, 165 of these applications had been approved for registration, 24 cancelled, 17 refused and six withdrawn. The ANAO examined a sample of 20 approved, 13 refused and all six withdrawn applications (from the population of 212 applications received in 2016) and assessed compliance with internal instructions and statutory requirements.

2.15 The ANAO found inconsistencies in the timeframes given by ORIC to applicants to provide extra information and in ORIC’s approach to resolving issues with rule books. For nine of the twenty approvals, ORIC did not document its rationale for approving applications where insufficient evidence was provided to demonstrate that non-mandatory requirements had been met. The ANAO also found minor classification errors and recordkeeping issues (such as applications classified as withdrawn that should have been classified as refused and application files that contained information relating to other applications).

2.16 ORIC’s recently instituted quality assurance framework, which includes assessment of registration tasks, is intended to assist in identifying and addressing errors and recordkeeping issues with processing applications. With regard to inconsistencies, ORIC informed the ANAO that its staff exercise discretion, with oversight from their managers, in setting flexible timeframes and resolving rulebook issues on a case-by-case basis, depending on factors such as whether an organisation is using a professionally qualified person (such as a lawyer) to assist with its application or applying without such assistance.

2.17 ORIC publishes external policy statements and fact sheets that provide guidance on legislative requirements for registration as an Indigenous corporation. It also has detailed internal procedural manuals for staff that provide technical instruction on how to process applications within ERICCA. These guidance documents do not provide sufficient guidance to staff on aspects of registration decision-making such as: when to approve applications that do not meet non-mandatory requirements; timeframes and protocols for seeking additional information from applicants; and protocols for making Registrar-initiated changes to rule books. Providing staff with principles-based guidance and procedures could help to ensure the quality and consistency of registration decisions, while still allowing staff to exercise flexibility and discretion in their assessment processes, where appropriate.

Recommendation no.1

2.18 ORIC should review and update its guidance and procedures for assessing applications for registration as an Indigenous corporation.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

2.19 To assist and support staff with administering the CATSI Act, including applications for registration, ORIC has a comprehensive suite of procedural manuals, internal fact sheets, policy statements and regular guidance notes.

2.20 ORIC maintains the Electronic Register of lndigenous Corporations under the CATSI Act (ERICCA) database that provides a workflow for ORIC business processes. It has built in automated and manual checks to identify issues of non-compliance with the CATSI Act. These processes incorporate role components, that is, independent checking by an officer independent of the receiving officer. For the application for registration process, there are two quality assessments: a review process by a second officer; and approval by a senior ORIC officer.

2.21 ORIC complements this checking at the time of processing with sampled follow up testing. Every month a sample of new registration jobs are checked for a range of quality issues such as data accuracy, adherence to assessment process, completeness of supporting documentation, and accessibility standards.

2.22 ORIC agrees with the proposed audit report that procedures for documenting such decisions and other similar issues in quality control can be improved.

Does ORIC maintain a Register of Disqualified Officers in accordance with requirements?

In accordance with the CATSI Act, ORIC maintains a Register of Disqualified Officers, which is publicly accessible on its website. However, ORIC does not have adequate procedures to ensure persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are promptly listed on the register following disqualification and required documents are stored on its register database.

2.23 In addition to the Register of Indigenous Corporations, the CATSI Act also requires ORIC to maintain a Register of Disqualified Officers, which contains information and documents relating to people disqualified from managing Indigenous corporations by a court (under ss. 279-15, 279-20 and 279-25) or by ORIC (under s. 279-30).13 The Register of Disqualified Officers is published on ORIC’s website, linking to data stored in ERICCA.14 As at 23 March 2017, there were twelve disqualified officers listed on the register.

2.24 Disqualified officers cannot manage an Indigenous corporation—which means they cannot be a director, secretary (for large corporations) or contact person (for medium or small corporations)—unless they have been granted permission by ORIC or leave by the Court. ORIC must store copies of any permission or leave granted, as well as other relevant notices and orders, on the register.

2.25 The ANAO reviewed the register and found15:

- one officer disqualified from 16 April 2015 to 15 April 2019 was listed as a current director for a registered Indigenous corporation as at 23 March 201716;

- while most listings for civil matters were prompt, three officers disqualified from 20 September 2016 were not listed on the public register until 27 October 2016; and

- copies of court disqualification orders were stored in ERICCA for only two of the ten officers disqualified by a court under s. 279-15.

2.26 The CATSI Act does not require ORIC to list officers automatically disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation under s. 279-5 on the Register of Disqualified Officers. However, ERICCA was designed with the functionality to allow such disqualified officers to be listed. The ANAO found two officers automatically disqualified under s. 279-5 for five years due to criminal offences from 23 November 2012 and 28 February 2013 were listed on the public register on 27 November 2015 (after ORIC had received an inquiry from a member of the public about the status of one of the individuals); five other officers automatically disqualified due to criminal offences had not been listed on the public register. ORIC should be consistent in its treatment of automatically disqualified officers and list either all or none on the register.

2.27 ORIC has an ERICCA procedural manual, REG–110: Disqualify Person(s), which outlines procedures to list a disqualified officer on the Register of Disqualified Officers. In addition, ORIC has an Investigations and Prosecutions—Consolidated Manual, which includes sections relating to disqualified persons. These documents do not include:

- procedures to ensure persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are promptly listed on the register following disqualification;

- instruction on what documents should be stored on the register and where they should be stored; and

- checks to be undertaken to ensure persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar do not continue to hold director or secretary positions within Indigenous corporations; and

- guidance on the treatment of persons automatically disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation under s. 279-5.

Recommendation no.2

2.28 ORIC should establish procedures to ensure that persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are promptly listed on the Register of Disqualified Officers, relevant documents are stored on the register, and such disqualified persons do not continue to hold the positions of director or secretary in Indigenous corporations.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

2.29 ORIC currently has an investigations and prosecutions manual in place that comprehensively documents operating procedures for the conduct of investigations and prosecutions. These procedures are currently being reviewed and will be updated to ensure:

- consistency of treatment of persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar

- persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar are published in a reasonable timeframe

- correct documentation is stored on the public register.

2.30 ORIC is also undertaking an audit of corporation records in the Register of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations to ensure persons disqualified by a court or the Registrar do not hold the positions of director or secretary in Indigenous corporations.

Does ORIC exchange data from its registers with other corporate and non-for-profit regulators?

ORIC has an established data exchange arrangement with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, which minimises reporting burden on Indigenous corporations. There is scope for ORIC to explore options for establishing data exchange arrangements with Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Australian Financial Security Authority and/or the Australian Taxation Office.

2.31 Indigenous corporations will often also be registered with the Australian Business Register (to obtain an Australian business number or ABN) and, if they are a charity or not-for-profit organisation, with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC). In addition, a person is automatically disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation if they are disqualified under the Corporations Act or are bankrupt. ASIC maintains a banned and disqualified register and the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) maintains the National Personal Insolvency Index, which includes details of people who are bankrupt.

2.32 ORIC has memoranda of understanding (MoUs) in place with ASIC and ACNC, but not with AFSA or the Australian Taxation Office, which manages the Australian Business Register. ORIC had agreed a target to negotiate ‘three new MoUs with external agencies to provide for information exchange and greater regulatory cooperation’ by 31 March 2016. This target was included in ORIC’s internal business plans for 2014–15 and 2015–16. ORIC has not met this target; the most recently negotiated MoU with an external regulator commenced on 19 August 2013.

2.33 ORIC’s MoU with ASIC allows for data exchange, but ORIC and ASIC do not regularly exchange register data. ACNC is the only regulator with which ORIC has an established data exchange arrangement. ORIC and ACNC exchange data from their registers half yearly, including corporation details, deregistered corporations and corporation directors. ORIC and ACNC have also put in place arrangements to ensure Indigenous corporations registered with both regulators only need to lodge an annual report with ORIC.

2.34 To support its compliance and enforcement program, ORIC should explore options to establish data sharing arrangements with ASIC and negotiate new MoUs with AFSA and the Australian Taxation Office.

3. Monitoring and enforcing compliance

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether ORIC effectively monitors and enforces compliance with the CATSI Act and whether it measures and reports on its regulatory performance.

Conclusion

ORIC’s ongoing focus on Indigenous corporations’ compliance with annual reporting requirements has led to a significant improvement in reporting response rates for Indigenous corporations over the past decade. It has also undertaken successful civil and criminal proceedings against officers of Indigenous corporations. ORIC’s other regulatory interventions include conducting examinations and special administrations. While internal data suggest these interventions are relatively successful, ORIC could employ a more structured approach to risk profiling corporations so as to better target its examinations. ORIC publishes data on its regulatory activities in an annual yearbook, but in recent years it has not committed to, or reported against, regulatory performance targets.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at refining its risk rating system in ERICCA to better support its regulatory program. The ANAO suggested ORIC report Indigenous corporations’ reporting compliance rates as at the legislative deadline.

Does ORIC monitor Indigenous corporations’ compliance with legislative requirements?

ORIC’s ongoing emphasis on monitoring and enforcing Indigenous corporations’ compliance with annual reporting requirements has achieved a significant improvement in reporting response rates over the past decade. It also conducts an annual rolling program of routine examinations to monitor large, essential or publicly funded corporations, which frequently identifies compliance issues that trigger further regulatory action.

3.1 Under both the CATSI Act and common law, registered Indigenous corporations and their directors must comply with a range of requirements. For corporations, obligations include:

- lodging an annual report by 31 December (unless an exemption has been granted);

- holding an annual general meeting between 1 June and 30 November (unless an exemption is granted);

- maintaining up-to-date financial records and registers of members and former members;

- keeping ORIC informed of relevant changes to the corporation; and

- following rules set out in its rule book, such as keeping minutes of meetings.

In addition, directors of Indigenous corporations have legal duties to act with reasonable care and diligence, act in good faith in the best interests of the corporation, not improperly use their position or information, disclose material personal interests, and not trade while insolvent.

3.2 ORIC monitors the compliance of Indigenous corporations and their directors with these requirements through:

- ensuring corporations comply with their annual reporting obligations and reviewing information lodged by corporations;

- using information from complaints, disputes and intelligence gained through its support activities to identify potential instances of non-compliance or risks of corporate failure; and

- undertaking a routine program of examinations targeted at large, essential or publicly funded corporations.

Compliance with reporting requirements

3.3 The deadline for most Indigenous corporations to lodge their annual reports is 31 December each year (six months after the end of the financial year).17 Requirements for annual reporting are determined by an Indigenous corporation’s registered size and its annual operating income (see Table 3.1).18 Corporations may seek exemptions from lodging a particular report or to extend the deadline for reporting, which ORIC considers on a case-by-case basis.

Table 3.1: Annual reporting requirements for Indigenous corporations

|

Registered size and income of corporation |

Report(s) required |

|

Small corporation with consolidated gross operating income less than $100 000 |

|

|

Small corporation with consolidated gross operating income between $100 000 and $5 million Medium corporations with consolidated gross operating income less than $5 million |

|

|

Large corporations or any size corporation with a consolidated gross operating income of $5 million or more |

|

Source: ORIC, Corporation Reporting Guide, October 2014, p. 3.

3.4 Since the 2006–07 reporting period, ORIC has implemented an annual communication and support program to encourage (and, if necessary, compel) Indigenous corporations to comply with reporting requirements. The program involves a graduated series of actions including:

- reminders in ORIC publications and on its website;

- follow-up with key groups and sectors (such as Native Title Corporations);

- face-to-face visits by ORIC’s regional officers;

- telephone reminders to newly registered corporations; and

- outreach and formal warning notices to corporations in breach.

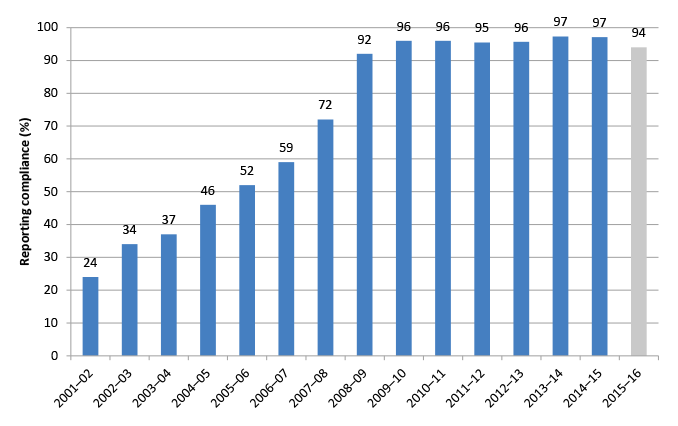

3.5 For yearbook reporting, ORIC defines reporting compliance as the final response rates for corporations, rather than the percentage of corporations meeting the legislative deadline of 31 December. Figure 3.1 outlines the percentage of Indigenous corporations that submitted annual reports from 2001–02 to 2015–16. These results demonstrate that ORIC’s communication and support program achieved a sharp increase in response rates, with over 95 per cent of corporations submitting reports since 2009–10. To be consistent with the CATSI Act requirement, ORIC should report compliance as at the legislative deadline, as well as the number of corporations that submit reports after the deadline. For 2015–16, the compliance rate as at 31 December 2016 was 84.8 per cent; as at 22 March 2017, the response rate for 2015–16 was 94 per cent.

Figure 3.1: Annual reporting response rates, 2001–02 to 2015–16a

Note a: Data for 2015–16 is as at 22 March 2017

Source: ORIC, Yearbook 2015–16, p. 15 and ORIC internal reporting (2015–16)

3.6 After annual reports have been received from corporations, ORIC staff enter data into ERICCA, check entries and commit reports to the corporations register. Once reports have been committed, they can be downloaded from the public register.

Complaints, disputes and other intelligence

3.7 Among ORIC’s functions are to assist with complaints and disputes involving Indigenous corporations and to provide other support functions such as corporate governance training (see Chapter 4 for discussion of ORIC’s support functions, including statistics relating to complaints and disputes). Monitoring and assessing intelligence gathered through these support activities forms a component of ORIC’s compliance monitoring strategy.

3.8 Complex and serious issues identified through support activities that may require regulatory or enforcement action are referred to one of two internal standing committees for further consideration:

- Corporations Complaints Panel—which considers complaints and disputes involving Indigenous corporations and may refer matters to the Regulation team for a targeted examination; and

- Regulation and Litigation Committee—which considers matters that may require investigation and enforcement action (enforcement outcomes are discussed later in this chapter).

Examinations

3.9 Under Division 447 of the CATSI Act, ORIC has the power to send an authorised officer (an examiner) to examine the books and records of an Indigenous corporation. Examinations involve assessing an Indigenous corporation’s standards of corporate governance and financial management, including:

- compliance with the CATSI Act and the corporation’s rules;

- the viability and solvency of the corporation;

- whether any directors have material personal interests and, if so, whether they have been properly managed;

- whether there is any evidence of corruption or misuse of corporation resources for personal benefit;

- any lack of control, direction and management of the affairs of the corporation by the directors.

3.10 ORIC’s policy statement, PS–25: Examinations, outlines two categories of examinations:

- an ‘annual rolling program’ of routine examinations targeting ‘large, essential or publicly funded corporations’; and

- targeted examinations triggered by disputes, complaints, financial or operational irregularities, or intelligence about other problems (targeting of examinations is discussed later in this chapter).

3.11 ORIC’s policy statement previously stated its rolling program would include approximately 30 to 40 of the largest 200 Indigenous corporations each year, with an aim to examine large corporations at least once every three to five years. After the ANAO informed ORIC that it had not been achieving this benchmark in recent years, ORIC removed reference to the timeframe and frequency of examinations from its policy statement. The revised statement, in place from 26 October 2016, states: ‘The number of corporations examined each year under the rolling program will depend on the resources available to the Registrar in each year’.19

3.12 For the 2016–17 year, the Regulation team was allocated a budget of $550 000 and committed to a target of completing 50 examinations by 30 June 2017, based on an average cost of $11 000 per examination.20 For its 2016–17 rolling program of routine examinations, 19 large corporations and six medium and small corporations were identified, which represent 50 per cent of the annual budget and target.21 In previous years, its routine examinations have represented between 15 and 53 per cent of the annual total.

3.13 The potential results of an examination for an Indigenous corporation include:

- management letter—a letter indicating that no further regulatory action is required, which may include reference to minor instances of non-compliance or other issues identified through the examination that the Indigenous corporation should address;

- compliance notice—a notice issued under s. 439-20 of the CATSI Act requiring the corporation to take specific action to address serious non-compliance issues identified through the examination (compliance notices are actively monitored by ORIC and if a corporation does not comply ORIC may proceed to a show cause notice);

- show cause notice—a notice issued under s. 487-10 of the CATSI Act requiring the corporation to explain why it should not be placed under special administration (depending on the corporation’s response, ORIC may initiate a special administration, undertake other regulatory actions, such as issuing a compliance notice, or take no further action); and

- deregister or wind up—if a corporation is found to be insolvent or inactive it may be deregistered or wound up.

3.14 Table 3.2 shows the reported results of examinations conducted since 2007–08 (when the CATSI Act commenced). These results show 73.2 per cent of examinations conducted over this period identified serious issues leading to further regulatory action. Of those examinations that result in a management letter, the overwhelming majority identify minor instances of non-compliance or other issues.22

Table 3.2: Reported examination results, 2007–08 to 2015–16

|

Examination result |

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

Management letter |

11 |

17 |

13 |

29 |

19 |

22 |

12 |

16 |

6 |

|

Compliance notice |

40 |

49 |

56 |

34 |

31 |

26 |

26 |

33 |

27 |

|

Show cause notice |

5 |

11 |

3 |

7 |

9 |

1 |

7 |

10 |

4 |

|

Deregister/wind up |

1 |

2 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

TOTAL |

57a |

79a |

77 |

72 |

61 |

51 |

46 |

59 |

39 |

Note a: The totals reported by ORIC for 2007–08 (60) and 2008–09 (81) have been amended in this table as they did not equal the sum of reported examination results for these years.

Source: ORIC, Yearbook 2011–12, p.43 & Yearbook 2015–16, p. 27.

3.15 The ANAO was unable to validate the reported examination results in Table 3.2 due to minor discrepancies between the reported figures, outcomes recorded in ERICCA and those recorded in an Excel spreadsheet the Regulation team has been using to manage and report on its compliance program since 2002. ORIC should either:

- build greater functionality into ERICCA (so the Regulation team no longer needs to use a separate spreadsheet to manage and report on its activities); or

- upgrade the spreadsheet by reformatting worksheets to allow for ease of analysis, using consistent category descriptions and linking to data held within ERICCA.

3.16 ORIC should also reconcile its compliance data to ensure figures reported in Yearbooks are consistent with its internal records and publish corrections where errors are found.

Does ORIC take a risk-based approach to regulatory intervention?

ORIC can generate risk ratings for corporations in its corporations register database, but due to limitations with the methodology these ratings provide limited value to ORIC’s regulatory program. While ORIC considers various matters in targeting its examinations, it does not systematically analyse the outcomes of interventions to improve its regulatory strategy.

3.17 ORIC can draw on a graduated range of regulatory and enforcement powers under the CATSI Act, including powers to:

- examine the books and records of an Indigenous corporation (Division 447) and seek a warrant to obtain books not produced (Division 456);

- issue a compliance notice (s. 439-20) requiring a corporation to take specific action;

- place a corporation under special administration (Division 487) and remove directors from office during the period (Division 496);

- disqualify people from managing corporations (s. 279-30);

- initiate criminal or civil proceedings against corporations or officers for various offenses or breaches (discussed later in this chapter); and

- wind up (Division 526) and/or deregister (Division 546) a corporation.

3.18 As noted in paragraph 3.2, ORIC receives intelligence relating to potential non-compliance or corporate failure risks from various sources, including annual reporting, examinations, complaints, disputes and support activities. If there is an indication of potential non-compliance or other problems (such as allegations made through complaints or intelligence gathered through support activities), as noted in paragraph 3.10, ORIC may initiate an ad hoc targeted examination to investigate the issue. Where there is clear evidence of a breach of legislative requirements or a serious problem with an Indigenous corporation, ORIC may immediately issue a compliance notice, initiate a special administration or wind up of the corporation, or commence an investigation into civil or criminal matters.

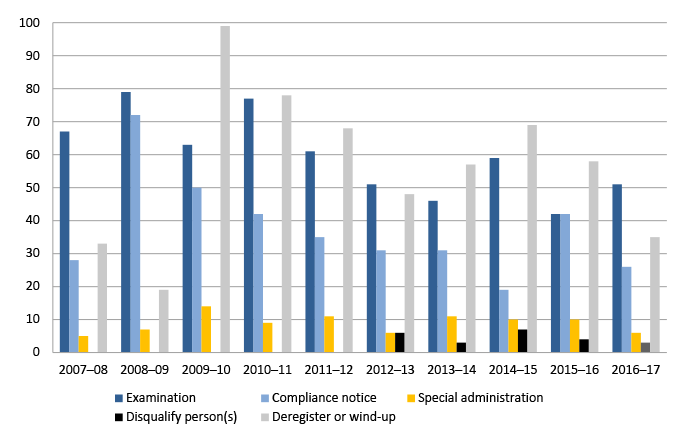

3.19 Figure 3.2 provides a breakdown of regulatory intervention tasks initiated within ERICCA for each financial year since 2007–08. While the number of interventions has fluctuated from year to year, the use of examinations and compliance notices has declined slightly in recent years.

Figure 3.2: Regulatory intervention tasks initiated, 2007–08 to 2016–17a

Note a: Data for 2016–17 is as at 31 March 2017.

Source: ANAO analysis of ERICCA data.

Risk rating in ERICCA

3.20 When ORIC processes annual reports from Indigenous corporations, ERICCA can generate automated risk assessments based on eleven weighted risk factors23; the resulting risk scores are rated as ‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’ or ‘extreme’. System documentation for ERICCA refers to the ‘ORIC Compliance Model’, which associates regulatory instruments with each risk rating level (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3: ERICCA risk ratings and ORIC compliance model

|

Risk rating |

Risk score |

Regulatory instruments |

Corporations with ratinga |

|

|

Extreme |

> 1.5 |

Deregistration |

86 |

3.1% |

|

High |

1.0 – 1.5 |

Audit (with or without penalty) |

538 |

19.4% |

|

Medium |

0.5 – 1.0 |

Real time business examinations, record keeping reviews |

1374 |

49.6% |

|

Low |

< 0.5 |

Training, education, record keeping, service delivery |

771 |

27.8% |

Note a: Ratings recorded in ERICCA as at 28 March 2017.

Source: ERICCA system documentation; ANAO analysis of ERICCA data.

3.21 The ANAO examined a random sample of 80 current assessments, 20 at each risk rating level, to review how risk factor scores contributed to ratings, and found:

- Only two factors, liquidity and net trading result, have a significant influence on risk ratings (each factor has a maximum score of 0.85). All other factors have an insignificant influence on ratings due to their low weighting (the maximum score for any other factor in the sample was 0.25) or are not used.

- To achieve an extreme risk rating, a corporation needs to trigger both the liquidity and net trading result factors, meaning its current liabilities equal or exceed current assets and its expenditure exceeds revenue.

- Due to a system anomaly, small corporations that have no liabilities or assets receive the maximum risk score (0.85) for liquidity, which leads to a medium or high risk rating. Based on the level of nil financial returns in the ANAO’s sample of 80 assessments, it is likely that around 40 per cent of corporations fall into this category. These anomalous ratings inflate the number of corporations receiving medium or high risk ratings, making it difficult to identify corporations that are truly medium or high risk.

3.22 Due to the large numbers of corporations receiving high and medium risk ratings, ORIC does not follow the strategies and instruments identified in the ORIC Compliance Model. Instead, it only follows up on extreme ratings. This involves contacting extreme risk corporations to determine if there is a reasonable explanation for their reported trading loss and liquidity results; if a reasonable explanation is not provided, the corporation is referred to the Corporation Complaints Panel or the Regulation and Litigation Committee to consider further regulatory action.

3.23 The risk rating system in ERICCA is a sophisticated tool for monitoring regulatory risks posed by Indigenous corporations. However, due to the way it is currently calibrated and used, it provides limited value to ORIC’s compliance program.

3.24 ORIC does not systematically analyse the outcomes of its regulatory interventions to identify the extent to which the risk criteria in ERICCA correlate with instances of non-compliance or corporate failure, so as to refine its regulatory strategy. Recalibrating the risk rating system, and analysing data from regulatory interventions to further refine the system, would provide ORIC with a more structured and evidenced-based approach to regulatory decision making.

Recommendation no.3

3.25 ORIC should refine its risk rating system in ERICCA to better support its regulatory program.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations response: Agreed.

3.26 ORIC has already commenced reviewing its operating procedures manuals and guidance for key business processes. Deficiencies and known problems in the risk rating system in ERICCA will be addressed when information technology resources become available.

3.27 The recommendation also reflects the direction ORIC has already taken in reviewing and publishing its regulatory approach and strategic risk frameworks. Key documents already published on oric.gov.au include:

- ORIC regulatory approach—which sets out the regulatory mission, why there is a need to regulate, ORIC’s approach to regulation and how this is informed by risk

- ORIC strategic risk framework—which describes risk processes, from the information collected and how it is used to evaluate risk priorities, through to planning meaningful measurable responses. The framework guides ORIC on how to identify where and how to focus its resources

- ORIC case categorisation and prioritisation model—which describes the decision-making processes that takes place within ORIC to select, categorise and prioritise matters; and the principles according to which those decisions are made

- ORIC performance measurement framework—which describes how ORIC measures the value of the work it does. ORIC focuses on measuring outputs, outcomes and regulator performance.

Targeting examinations

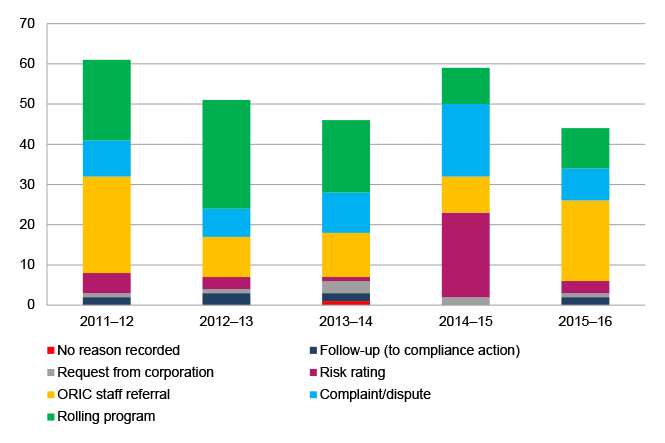

3.28 Figure 3.3 outlines the reasons for initiating examinations (as recorded in the Regulation team’s Excel spreadsheet) since 2011–12. These results show significant disparity from year to year in the proportion of examinations initiated for different reasons; for example, in 2011–12 and 2015–16 staff referral was the most common reason, in 2012–13 the majority of examinations were identified as part of the rolling program, whereas complaints/disputes and risk ratings were the most common reasons in 2014–15.

Figure 3.3: Reasons for examinations, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO analysis of ORIC records.

3.29 While ORIC’s examinations policy statement outlines various matters that ORIC considers in targeting examinations, its approach to targeting examinations is relatively unstructured and relies primarily on the experience and intuition of staff. Refining the risk rating system in ERICCA (see Recommendation No.3) and making greater use of risk ratings in targeting examinations would provide a more structured approach to determining its examination program.

Does ORIC’s special administration power lead to more sustainable Indigenous corporations?

ORIC’s program of special administrations has returned a majority (around 90 per cent) of Indigenous corporations to members’ control, and the majority of these corporations (more than 90 per cent) have not subsequently been deregistered. These outcomes suggest the program is well targeted and leads to more sustainable Indigenous corporations.

3.30 As noted in ORIC’s policy statement, PS–20: Special administrations, special administration is ‘a form of external administration unique to the CATSI Act’.24 Unlike external administration under the Corporations Act, which usually aims to protect the interests of creditors, the primary objective of special administration is to restore an Indigenous corporation to financial and organisational health and return it to its members’ control.

3.31 Grounds for ORIC placing an Indigenous corporation into special administration are broad, and include:

- the corporation trading at a loss for six of the past twelve months;

- the corporation failing to comply with requirements of the CATSI Act;

- a serious dispute occurring within the corporation;

- officers acting in their own interests or contrary to the interests of members; and

- the public interest.

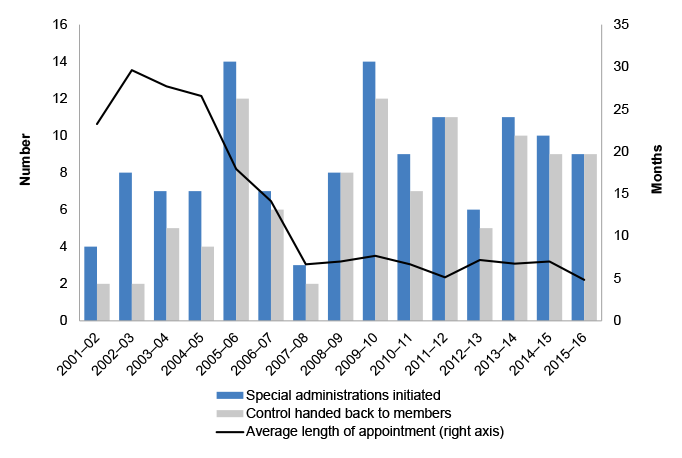

- In addition, a majority of directors or a certain number of members may request that a special administrator be appointed.25

3.32 Special administration is a time and resource intensive regulatory intervention. ORIC usually appoints a special administrator from a panel of external providers, with a target of achieving business turnaround and handing control of the corporation back to members within six months; however, some special administrations can continue for more than a year. The average direct cost to ORIC of special administrations initiated since 2009–10 (not including the cost of ORIC staffing) is $163 329 (excluding GST). Consequently, ORIC needs to consider the size, nature and ongoing viability of an Indigenous corporation before making a decision about whether to appoint an external administrator.

3.33 Figure 3.4 shows the number of special administrations initiated each year since 2001–02 and the number where control of the corporation was returned to members (including through amalgamation with other Indigenous corporations). Since 2005–06, a high proportion (89.2 per cent) of special administrations have succeeded in returning control to members (compared with 50 per cent from 2001–02 to 2004–05). Figure 3.4 also shows the average length of special administration appointments, which has reduced significantly since the early 2000s and stabilised at around seven months.

Figure 3.4: Special administrations, 2001–02 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO analysis of ORIC records.

3.34 Following a special administration, ORIC undertakes intensive monitoring of a corporation for the next eighteen months. While ORIC has not undertaken longitudinal analysis of the longer term outcomes for corporations that have been placed under special administration, the ANAO found only six of the 103 corporations returned to members’ control over the period of 2001–02 to 2015–16 have subsequently been deregistered.26

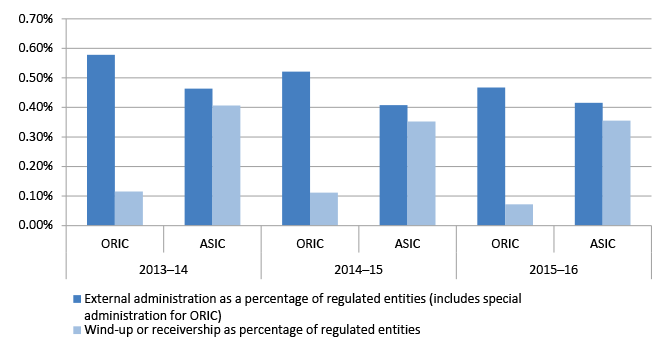

3.35 In addition to special administration, Indigenous corporations can be placed under other types of external administration through the appointment of a receiver, administrator or the winding up of the corporation (in same way as Corporations Act companies). Figure 3.5 provides a comparison of external administration appointments reported by ORIC and ASIC as a proportion of their regulated entities.27 This comparison shows the percentage of all external administration appointments (including special administrations) is slightly higher for ORIC; whereas the proportion of wind-up or receivership appointments is generally lower. This suggests ORIC’s special administration power is relatively successful in restoring an Indigenous corporation to financial and organisational health.

Figure 3.5: External administration statistics, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO analysis of ASIC and ORIC data.

Does ORIC take appropriate enforcement action when breaches are identified?

ORIC has initiated enforcement action, including civil proceedings and criminal prosecutions for breaches of the CATSI Act. The majority (around 95 per cent) of criminal prosecutions initiated by ORIC have been for breaches of annual reporting requirements by Indigenous corporations; an approach that has contributed to ORIC’s high rates of reporting response rates. ORIC’s other criminal prosecutions and civil proceedings relate to the behaviour of officers of Indigenous corporations, and have resulted in disqualification, fines and, in some cases, imprisonment.

The CATSI Act contains civil penalties and criminal offences relating to the conduct of Indigenous corporations and their directors and officers. Civil penalties apply, for example, to breaches of officers’ duty to exercise care and diligence, to act in good faith, and to not misuse their position or information.28 Criminal offences include:

- relatively minor offences, such as a corporation failing to provide governance material to a member upon request29; and

- offences punishable by substantial fines and five years’ imprisonment (the maximum penalty under the Act), such as for making false or misleading statements.30

3.36 ORIC also cooperates with state and territory police where breaches of criminal law outside the CATSI Act, such as theft or fraud, may have occurred.

3.37 The ANAO reviewed outcomes of ORIC’s civil proceedings and criminal prosecutions, as published on its website as at 10 April 2017. The records covered the period 28 September 2010 to 17 February 2017 and related to 14 civil matters and 137 criminal matters.

- The 14 civil matters related to the behaviour of officers of Indigenous corporations, such as not exercising powers with reasonable care and diligence and using their position improperly. Outcomes and penalties ranged from freezing orders to protect the assets of a corporation to heavy fines, compensation orders and disqualification from managing a corporation. All 12 individuals who were subject to civil proceedings were subsequently listed on the Register of Disqualified Officers. The highest penalty awarded was disqualification for 15 years and compensation orders and fines exceeding $1.2 million plus court costs.

- Of the 137 criminal prosecutions, 130 (94.9 per cent) addressed reporting compliance by Indigenous corporations.31 As noted in paragraph 3.4, ORIC seeks to encourage high rates of reporting compliance. If corporations do not meet reporting requirements after reminders and outreach, ORIC refers breaches to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions for prosecution. Outcomes of reporting compliance prosecutions have ranged from discharge without penalty through to fines of up to $14 000.

- The seven other criminal prosecutions related to criminal breaches of the duties of officers of Indigenous corporations. All resulted in imprisonment (for periods of between three and 15 months), disqualification from managing a corporation, as well as orders to pay compensation and court costs. Two of the seven individuals prosecuted were listed on the Register of Disqualified Officers (see paragraph 2.26 above).

3.38 The ANAO found civil proceedings relating to three former directors of an Indigenous corporation, which were concluded on 20 September 2016, had not been updated on ORIC’s ‘Prosecution outcomes’ website. Two of the individuals were disqualified from managing an Indigenous corporation for five years and fined $38 500 each; as at 23 March 2017, both were listed on the Register of Disqualified Officers.

3.39 ORIC has had a performance target of 75 per cent successful outcomes in litigation since 2008–09. The last time it externally reported a result for this target was in 2009-10, when it achieved 83 per cent successful outcomes. ORIC’s internal reporting to senior managers indicates that it has continued to maintain a success rate for litigation outcomes of higher than 75 per cent.

Does ORIC measure and report on its regulatory performance?

ORIC has internal regulatory performance targets, against which it monitors progress. It also publishes performance information in its annual yearbook. However, in recent years ORIC has not committed to external performance targets. In response to a recent review and the preliminary findings of this audit, ORIC developed a revised suite of corporate documents.

3.40 ORIC sets qualitative and quantitative targets for its regulatory activities as part of its annual business planning, which occurs in May or June ahead of the new financial year. ORIC’s business plan for 2015–16 outlined the following regulatory targets:

- three new MoUs with external agencies to provide for information exchange and greater regulatory cooperation;

- assess complaints and refer appropriate matters for investigation and prosecution;

- 75 per cent successful outcomes in litigation;

- ensure 90 per cent of corporations are compliant with reporting requirements;

- carry out 45 examinations; and

- complete special administrations within six months, achieve business turnaround and successful outcomes (returning a corporation to members’ control).32

3.41 ORIC monitors and internally reports progress against these targets fortnightly. While ORIC has not published its performance targets externally since 2009–10, it has continued to report on performance against some of the indicators in its annual yearbook (without referencing its internal targets).33 It also publishes statistics about corporations entering external administration and complaints on its website.

3.42 As a regulator, ORIC is required to self-assess and publish its performance annually in accordance with the Regulator Performance Framework.34 Between June and September 2015, ORIC created a set of performance indicators against which it could self-assess and report its performance as a regulator under the framework. However, in January 2017, ORIC was advised to delay the implementation of its indicators pending the outcomes of an internal review.

Review of ORIC

3.43 In September 2016, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (the department) commissioned a review of the performance of ORIC and aspects of the operation of the Act. The review concluded that ORIC was ‘doing a good job, in a challenging regulatory environment’35. The review also made various recommendations for improvement, including that:

- the Minister for Indigenous Affairs send ORIC an updated Statement of Expectations, articulating the Government’s expectations for its role and strategic direction36;

- ORIC develop a strategic risk management framework to support the effective management of corporate governance and financial management compliance risks;

- ORIC publish its three year strategic plan, refreshed annually, linked to its regulatory approach, which explains how its current priorities and compliance projects are explicitly targeted to addressing existing and emerging compliance issues; and

- ORIC develop a performance reporting framework that demonstrates links between specific issues, actions to address issues and outcomes achieved (drawing on the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Regulator Performance Framework guidance).

3.44 The department advised the ANAO that the Government is considering its response to the ORIC review report and expects to publicly release the report in due course.

Revisions to ORIC’s corporate documents

3.45 In response to the review and the preliminary findings of this audit, ORIC held a strategic planning workshop in February 2017 attended by all senior managers, to develop a suite of corporate documents. On 12 May 2017, ORIC published the following corporate documents on its website:

- Strategic plan: 2017–20—a high-level overview of ORIC’s vision, aim, values, business model and strategic priorities ;

- Corporate plan: 2017–20—expands on the Strategic plan by providing detail on activities to achieve strategic priorities and ORIC’s risk and performance frameworks;

- Regulatory approach—describes ORIC’s regulated entities, its regulatory purpose, posture and toolkit, and its risk principles;

- Strategic risk framework—outlines ORIC’s principles and processes for managing strategic risk;

- Performance measurement framework—sets out current output measures, potential outcome measures and revised indicators for the Regulator Performance Framework; and

- Case categorisation and prioritisation model—an overview of ORIC’s approach to determining what cases it will intervene in.

3.46 As these revisions occurred after fieldwork for this audit had concluded, the ANAO has not assessed the implementation of these corporate documents. In line with ORIC’s recent approach, external performance measures do not include commitments to performance targets.

Does ORIC have appropriate mechanisms for managing conflicts of interest?

ORIC is covered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s policy and procedures on conflicts of interest, which requires ORIC to maintain a register of any real or perceived conflicts of interest identified by its staff.

3.47 As a regulator, it is important that ORIC has appropriate and accessible mechanisms in place to ensure its staff maintain independence from the entities it regulates and conflicts of interests, whether real or perceived, are identified and managed appropriately.37 Since ORIC is a small regulator and cannot fully segregate its regulatory and support functions, the risks to regulatory independence are heightened.

3.48 As at April 2017, ORIC’s intranet included a link to ‘Recognising and managing conflicts of interest’, which was published in April 2009. The document included references to the previous department that ORIC had been part of, prior to the machinery of government change in September 2013 that brought ORIC into the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

3.49 ORIC informed the ANAO that the document had been superseded by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s policy and procedures for managing conflicts of interest. In June 2017, ORIC informed the ANAO that the superseded document had been removed from its intranet and replaced with a link to the department’s policy.

3.50 The department’s policy requires staff who have identified a real or perceived conflict of interest to a complete declaration of interests form and forward it to their manager and Branch Manager. Completed forms should be kept on a register within the Branch. ORIC should ensure that it actively manages conflicts of interest in accordance with this policy.

4. Providing information, advice and education

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether ORIC supports good governance in Indigenous corporations through providing information, advice and education.

Conclusion