Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Supporting the Australian Antarctic Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), a division of the Department of the Environment, to support Australia’s Antarctic Program.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Antarctic Program is administered by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), a division of the Department of the Environment. AAD’s purpose is to Advance Australia’s strategic, scientific and environmental interests in the Antarctic through the following objectives:

- conduct and facilitate scientific research;

- protect the Antarctic environment;

- preserve Australia’s presence and sovereignty in the Australian Antarctic Territory; and

- contribute to Antarctica’s freedom from strategic and political confrontation.1

2. To achieve these objectives, AAD maintains four permanent stations in the Antarctic and subantarctic region: Casey, Mawson and Davis stations on the Antarctic continent; and Macquarie Island station in the subantarctic Southern Ocean. AAD transports around 400 staff to its stations each summer and supports small ‘over-winter’ crews of around 15–20 people at each station. AAD operates each station on a ‘small town’ basis, with sufficient supplies and technical expertise to survive the isolated winter months and cope with unexpected events at any time of the year (such as medical emergencies, rescues of Australian or international expeditioners, or delayed resupply due to weather or ice conditions).

3. AAD also coordinates and supports the Australian Antarctic Science Program, administers regulatory responsibilities under relevant legislation, and participates in international meetings relating to the Antarctic Treaty system. AAD has an annual budget of around $100 million (reducing to $90 million over the forward estimates), each year entering contracts worth over $60 million for the provision of goods and services in support of the Australian Antarctic Program.2

Audit approach

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established to support Australia’s Antarctic Program. To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO examined whether the AAD had established:

- sound oversight, planning and reporting arrangements;

- robust asset and contract management arrangements; and

- effective arrangements to manage the workforce required to deliver AAD’s objectives (including recruitment and training of expeditioners and managing their work, health and safety while in Antarctica).

5. The audit did not examine AAD’s: management of the Australian Antarctic Science Program; engagement with international Antarctic organisations; discharge of its limited regulatory responsibilities; or the procurement of the new icebreaker vessel (as the tender process was live during the audit).

Conclusion

6. As would be expected given AAD’s long history in administering Australia’s Antarctic Program, mature policies and frameworks are in place to support the effective delivery of key program responsibilities. These include strategic and operational planning, risk management (including risks to the health and safety of staff and expeditioners), and expeditioner recruitment, induction and training. AAD has also established sound administrative practices to support program delivery, including the management of a large number of diverse contracts for the provision of goods and services, a public communications program and a range of support services for expeditioners and their families.

7. As with all long-term programs, there is scope for AAD to regularly review the effectiveness and appropriateness of policies, frameworks and administrative practices for the Antarctic Program, particularly in light of reduced program funding over time and the resulting need for more efficient operations. In this context, there would be benefit in AAD initially focusing on: the establishment of a fit-for-purpose asset management strategy and supporting policies; strengthening IT project governance and management arrangements; and improving the management of work, health and safety investigations. Further, improving the existing program performance measurement framework, through expanding existing KPIs and/or developing additional measurement tools, would contribute to improved accountability and support more effective program management.

Supporting findings

Managing the Australian Antarctic Program (Chapter 2)

8. AAD has established sound arrangements to provide oversight of its responsibilities under the Australian Antarctic Program. These include a clearly-defined organisational structure and reporting responsibilities, with an Executive Committee that monitors key program risks and program deliverables. There has also been additional oversight and scrutiny of AAD’s operations, including internal audits, regulation of specific operational activities, and external reviews.

9. An effective strategic and operational planning framework to support the broad range of activities undertaken, and to manage the risks involved in the delivery of these activities, has been established by AAD. In particular, AAD has a strategic planning approach and related practices in place that align to Environment’s strategic planning framework, with an annual business planning model that includes tiered levels of information about objectives, planned activities, risks and operational level key performance indicators to measure progress.

10. AAD has a mature and comprehensive approach to managing risk, underpinned by sound policies and guidance for staff, with the approach and policies appropriately aligned to the department’s risk framework. The approach is multi-layered to account for the range of AAD’s activities, including a number of inherently high and extreme risks arising from its activities. AAD has developed and maintained comprehensive risk registers that outline risk mitigation strategies, assign responsibilities and identify timeframes for delivery of mitigation strategies/activities. The risk registers are also regularly reviewed by the AAD Executive and a Senior Executive from Environment.

11. While the performance measures established for the Australian Antarctic Program provide insights into the delivery of program activities, they do not clearly indicate the extent to which the overall objectives set for the program are being achieved. To better inform stakeholders about progress towards achieving the Government’s stated outcome and objectives, AAD should improve the effectiveness of its performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the program.

Managing contracts (Chapter 3)

12. AAD has established an appropriate contract management framework based on a ‘decentralised’ approach, whereby individual contracts are primarily managed by staff across line areas. To better support this decentralised operating model, AAD should improve the policies and guidance for its staff with contract management responsibilities. The planned implementation of a centralised contract register should also provide insights into potential areas for improvement in contract management practices.

13. Overall, AAD manages its contracts in accordance with sound contract management principles, including the requirements established under the Australian Government’s financial management framework. For higher-risk contracts, particularly in terms of value and/or their importance to the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program, AAD should formalise contract management arrangements through the development of fit-for-purpose contract management plans. The establishment of such plans would contribute to more consistent contract management practices across the division and reduce the impact of staff turnover and the resulting loss of corporate memory.

Managing assets and inventory (Chapter 4)

14. The procedures and systems that are in place, in the main, underpin the effective management of the broad range of assets required to deliver the Australian Antarctic Program. To supplement existing arrangements, AAD is implementing a system to better manage asset maintenance that, when fully implemented as planned, should enable the integrated planning and recording of all asset maintenance. In addition to the work being undertaken to establish an asset maintenance system, AAD should establish an overarching, fit-for-purpose asset management policy to better inform asset decision-making over the longer term and ensure that operational-level asset management plans are regularly updated.

15. AAD does not have an effective inventory management system in place even though the need for such a system has been highlighted in a number of internal reviews over the last 10 years. While AAD commenced a project in 2012 to develop an end-to-end inventory management system, it is yet to be completed. The project has substantially exceeded its original timeframe and budget, with revisions to the project over time resulting in a significant reduction in proposed system functionality.

Recruiting, training and supporting expeditioners (Chapter 5)

16. AAD has established sound recruitment approaches, including the provision of training, guidance and specialist support to those conducting recruitment processes, and refining arrangements on the basis of feedback from applicants. There are also suitable training arrangements in place to prepare the expeditioner workforce for Antarctic service, with a series of reviews conducted by AAD to identify areas for improvement. AAD is, however, yet to implement a Training Management System (TMS)—which was recommended by an internal review in 2010—to improve the management of training records.

17. A suitable range of support mechanisms has been made available to expeditioners and their families, including: a psychological debriefing process at the end of Antarctic service; access to the Employee Assistance Program; a 24-hour free helpline; and a package of information, resources and links to support networks for families and friends. The majority of expeditioners have reported satisfaction with the support AAD provides during and after their work in Antarctica—both for themselves and their families.

Managing work health and safety (Chapter 6)

18. A strategic approach has been established to manage work health and safety (WHS) risks within the Australian Antarctic Program. The WHS Management System is underpinned by a high-level framework and supported by a range of tools to identify, control and manage the risks inherent in the workplace—particularly the hazardous environment of AAD’s Antarctic stations. These systems and tools are supported by structured training and induction programs for staff and expeditioners. The effective oversight of the system is, however, impacted by the absence of regular on-station WHS Committee meetings (under the WHS System these committees are required to meet quarterly).

19. AAD has an effective system in place for reporting WHS incidents. As required by established internal procedures, the majority of incident reports recorded in the system are risk-rated, the underlying cause of incidents is recorded, and corrective actions are identified and undertaken. A recent focus on the timely closure of incident reports has also yielded positive results. However, the conduct of incident investigations, particularly in relation to more significant incidents, is an area that requires further attention. To effectively manage risk and to meet its WHS obligations, AAD should improve its management of incident investigations, in particular the timely completion of all required investigations.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.15 |

To improve accountability and support the effective management of Australia’s Antarctic Program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 4.8 |

The ANAO recommends that, to underpin an effective approach to the management of Antarctic Program assets, the Department of the Environment develop a fit-for-purpose strategic asset management policy supported by asset management plans and procedures that are regularly reviewed and updated. Environment’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.27 |

The ANAO recommends that, to support the successful delivery of future Antarctic Program IT projects, the Department of the Environment implement:

Environment’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 6.24 |

To effectively manage risk and to ensure compliance with its Work Health and Safety obligations, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment strengthen its WHS practices, particularly in relation to the management of WHS investigations. Environment’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

20. The Department of the Environment’s summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department welcomes the performance audit on Supporting the Australian Antarctic Program and agrees with the ANAO’s findings and recommendations. The report accurately presents the unique challenges in administering the Australian Antarctic programme and the conclusion gives recognition to the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD)’s long history in administering the programme and the existence of mature policies and frameworks that support the effective delivery of key programme responsibilities. The Department agrees that the recommendations represent improvement opportunities for enhancing policies, frameworks and administrative practices for the Australian Antarctic programme and advises that steps to implement the recommendations have already begun.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Antarctica, which covers over 13 million square kilometres—nearly twice the size of Australia—is the highest, driest, windiest and coldest continent in the world. Activities undertaken in Antarctica and its surrounding seas are governed by the Antarctic Treaty, which came into force in 1961.3 The underpinning premise of the Antarctic Treaty is that Antarctica should be used exclusively for peaceful purposes, in particular scientific research. The Treaty also sets aside the potential for sovereignty disputes by maintaining the status quo for existing territorial claims, and providing that no new or enlarged claims can be made.4

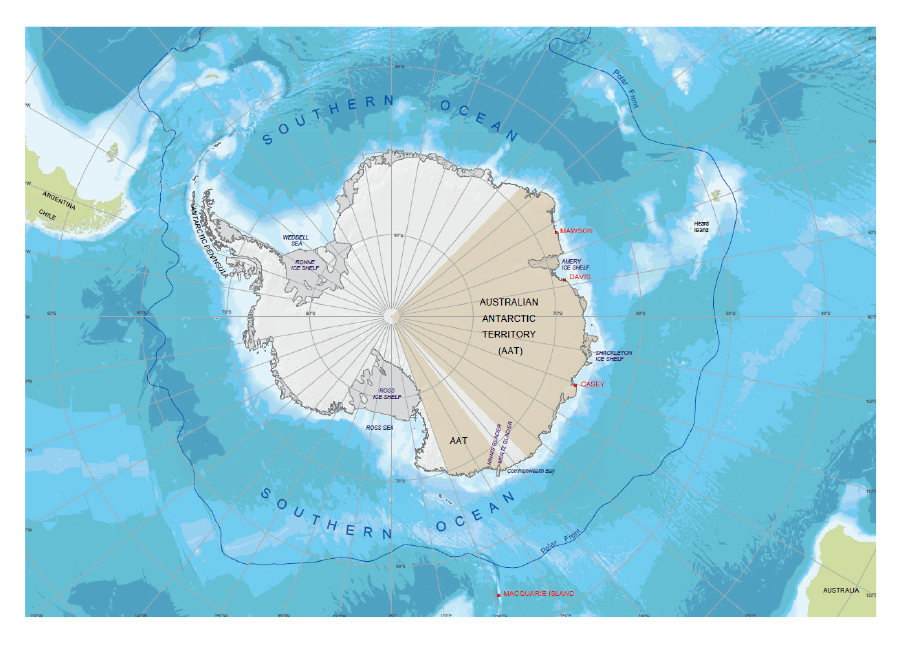

1.2 The Australian Antarctic Territory (see Figure 1.1) covers 5.8 million square kilometres (comprising 42 per cent of the total area of Antarctica—equivalent to nearly 80 per cent of the total area of Australia).5

Figure 1.1: Australian Antarctic Territory

Source: Australian Antarctic Division.

Australian Antarctic Division

1.3 The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), which was established in 1949, is a Division within the Australian Government Department of the Environment. AAD is based near Hobart, Tasmania, and has approximately 300 permanent staff and 100–200 contracted ‘seasonal’ staff. AAD’s purpose is to Advance Australia’s strategic, scientific and environmental interests in the Antarctic through the following objectives:

- conduct and facilitate scientific research;

- protect the Antarctic environment;

- preserve Australia’s presence and sovereignty in the Australian Antarctic Territory; and

- contribute to Antarctica’s freedom from strategic and political confrontation.6

1.4 Australia maintains four permanent stations in the Antarctic and subantarctic region: Casey, Mawson and Davis stations on the Antarctic continent; and Macquarie Island station in the subantarctic Southern Ocean.7 AAD also coordinates and supports the Australian Antarctic Science Program, discharges regulatory responsibilities under relevant legislation and participates in international meetings relating to the Antarctic Treaty system.

Australia’s Antarctic stations

1.5 The four Australian southern stations8 are operated year-round (maintaining a permanent presence in the Australian Antarctic Territory assists Australia to maintain its claim of sovereignty). Australia’s Antarctic activities are delivered across two ‘seasons’ per year—the summer season from early November through to mid-April, and the winter season, from March/April to October, during which stations are maintained by a small ‘over-winter’ crew. Key events for AAD’s management of the Australian Antarctic Program throughout the calendar year are outlined in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: AAD activities over a calendar year

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD information.

1.6 The summer season is focused on supporting scientific research on-station and in the field, and on undertaking capital works and maintenance activities at the stations (for example, a new wastewater treatment facility is being built at Davis Station over five summer seasons).

1.7 A key activity for AAD is planning and conducting the station resupply voyages during the summer season. These voyages must deliver all food, fuel, equipment, plant, machinery and parts and other supplies that will be needed on-station over the following 12 months, with few opportunities to ‘top up’ supplies that are not delivered by the resupply voyage. The majority of summer and winter station staff and scientists are also transported to and from the stations via the resupply voyages.9

1.8 The challenges and risks of operating in the harsh Antarctic environment have been illustrated by a number of recent incidents, highlighted below.

|

Case study 1. Recent incidents in Antarctica involving AAD |

|

Note a: The Akademik Shokalskiy is a private research/tourism vessel not affiliated with AAD. AAD has advised the Parliament that it is pursuing compensation costs from the company involved.

Source: AAD information.

AAD funding

1.9 Around 90 per cent of AAD’s annual budget is expended on maintaining, staffing and supporting the four Australian Antarctic stations. Over recent years, funding for Australia’s Antarctic Program has reduced, with $129 million provided in 2013–14, $114 million in 2014–15 and $104 million in 2015–16, with estimated funding of around $90 million per annum over the next three years (to 2018–19). The reduction in funding levels is primarily a result of lapsing programs and a reduction in own-source income.

Recent developments

1.10 In October 2013, the Government engaged Dr Tony Press10 to produce a 20 Year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan. Dr Press’s plan, which included 32 recommendations, was publicly released in October 2014. It stated that:

Australian leadership in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean is eroding. As Australia’s logistic and scientific capabilities stagnate through historical erosion of funding and the aging of its assets, other countries are ramping up their investments in Antarctic science, logistics and infrastructure.11

1.11 A number of the recommendations included in the plan, if accepted by government, would involve major new expenditure. As at January 2016, the Government had not released its response to the report.

1.12 The Aurora Australis, AAD’s icebreaker vessel, is nearing the end of its service. A procurement process for a company to design, build, operate and maintain a new icebreaker commenced in early 2013. In October 2015, DMS Maritime Pty Ltd was announced as the preferred tenderer and contract negotiations commenced, with the new vessel expected to be commissioned in 2019.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

1.13 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established to support Australia’s Antarctic Program. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- oversight, planning and reporting arrangements for AAD are sound;

- AAD has established robust asset and contract management arrangements; and

- effective arrangements are in place to manage the workforce required to deliver AAD’s objectives.

1.14 The audit focused on AAD’s planning, preparation and implementation activities in support of the Australian Antarctic Program. The audit did not examine AAD’s: management of the Australian Antarctic Science Program; involvement with international Antarctic organisations; discharge of its limited regulatory responsibilities; or the procurement of the new icebreaker (as the tender process was live during the audit).

1.15 In addressing the audit objective and criteria, the audit team: reviewed AAD documentation; interviewed key AAD staff and a range of stakeholders; and conducted detailed analysis, including reviewing a sample of contracts, testing the accuracy and completeness of data held in, and reported from, AAD’s asset maintenance system, and examining a sample of cases recorded in AAD’s Work Health and Safety (WHS) case management system.12

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards, at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $558 000.

2. Managing the Australian Antarctic Program

Areas examined

This chapter examines AAD’s arrangements for oversight, planning, risk management and performance measurement and reporting for the Australian Antarctic Program.

Conclusion

Overall, AAD has established appropriate oversight, planning and risk management arrangements to underpin the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program. While AAD has developed performance measures for the program and subsequently publicly reported against these measures, the performance information did not adequately inform stakeholders about progress towards achieving the Government’s stated outcome and objectives for the Australian Antarctic Program.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the monitoring of, and reporting on, the performance of Australia’s Antarctic Program.

Introduction

2.1 The Australian Antarctic Program is conducted in an extremely remote and challenging environment. The successful, safe and efficient delivery of the program relies to a large extent on effective oversight, strategic and operational planning, and risk management practices. Further, appropriate internal and external performance reporting informs program management and allows stakeholders to determine the extent to which AAD is meeting the objectives set by the Government for the Australian Antarctic Program.

Has AAD established appropriate oversight arrangements for the Australian Antarctic Program?

AAD has established sound arrangements to provide oversight of its responsibilities under the Australian Antarctic Program. These include a clearly-defined organisational structure and reporting responsibilities, with an Executive Committee that monitors key program risks and program deliverables. There has also been additional oversight and scrutiny of AAD’s operations, including internal audits, regulation of specific operational activities, and external reviews.

Organisational structure

2.2 As a division within the Department of the Environment (Environment), a departmental First Assistant Secretary is responsible for overseeing the AAD’s activities and reporting on divisional performance to one of the department’s three Deputy Secretaries. As at January 2016, AAD comprised four branches (Strategies, Support and Operations, Science, and Modernisation Taskforce).13

2.3 Overall, roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and communicated within AAD. There is also a high degree of collaboration between AAD sections during planning and delivery of each Antarctic ‘season’. For example, the Operations Section works closely with the Supply Services Section to ensure all projects and planned activities can be supported (that is, all of the equipment and people needed to carry out a particular science or infrastructure project can be accommodated by that season’s logistics).

Internal and external oversight arrangements

2.4 AAD has sound internal governance arrangements, including an Executive Committee that meets monthly to consider program implementation, risk (considered quarterly), and people management issues, including work health and safety. There is also a range of internal committees that report to the Executive Committee, and provide oversight and specialist advice across a range of matters such as environmental protection, work health and safety, operational planning, and corporate issues such as staff consultations, information management, ICT and procurement.14

2.5 Additional external oversight and scrutiny of AAD’s activities has also been provided by:

- AAD initiated internal audits (on topics such as the management of hazardous materials on Antarctic stations);

- Environment’s internal audits (the most recent examining supply chain management), which are subsequently reviewed by the department’s Audit Committee;

- regulatory regimes, such as those for quarantine, aircraft safety, shipping, and environmental management;

- ANAO financial statements audits and performance audits; and

- Parliamentary hearings/inquiries and external reviews, such as the 20 Year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan.

Is the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program underpinned by an effective planning framework?

An effective strategic and operational planning framework to support the broad range of activities undertaken, and to manage the risks involved in the delivery of these activities, has been established by AAD. In particular, AAD has a strategic planning approach and related practices in place that align to Environment’s strategic planning framework, with an annual business planning model that includes tiered levels of information about objectives, planned activities, risks and operational level key performance indicators to measure progress.

Strategic planning

2.6 AAD has two long-term strategic planning documents (AAD Strategic Directions 2012–2022 and the AAD Science Strategic Plan 2011–12 to 2020–2021), which provide direction for AAD’s key activities, and are aligned to the Government’s stated Outcomes for the Antarctic Program. AAD indicated that the Strategic Directions document is likely to be reviewed in the context of the Government’s response to the 20 Year Strategic Plan, when released. Under AAD’s business planning model, annual plans have been produced for the Division, each branch and section, that are appropriately aligned to Environment’s Corporate Plan 2015–16 and identify objectives, strategies, planned activities, risks and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

Seasonal operational planning

2.7 AAD has implemented a comprehensive operational planning framework that is overseen by a range of internal planning committees and the AAD Executive. Each season plan is accompanied by a risk assessment (discussed further in the following section) and well-documented procedures and planned approaches for each season, such as:

- Standard Operating Procedures for key operational activities, including shipping and small watercraft, aviation, station activities, field activities (off-station, such as visiting a wildlife breeding area for research purposes) and emergency response; and

- a Service Level Agreement between AAD’s Operations Section and the leader of each project to be supported throughout the summer season. All activities such as scientific research projects, AAD staff projects, and visits from dignitaries or media representatives, must be outlined in an agreement that details the scope of the project, support to be provided by AAD and roles and responsibilities.

Has AAD appropriately considered risks and determined and implemented appropriate mitigation strategies?

AAD has a mature and comprehensive approach to managing risk, underpinned by sound policies and guidance for staff, with the approach and policies appropriately aligned to the department’s risk framework. The approach is multi-layered to account for the range of AAD’s activities, including a number of inherently high and extreme risks arising from its activities. AAD has developed and maintained comprehensive risk registers that outline risk mitigation strategies, assign responsibilities and identify timeframes for delivery of mitigation strategies/activities. The risk registers are also regularly reviewed by the AAD Executive and a Senior Executive from Environment.

Policy and guidance

2.8 AAD had in place a risk management strategy, policy and guidelines that provide a clear framework for managing risk within the Antarctic Program. AAD staff have appropriate access to guidance materials through AAD’s intranet, with regular seminars and training also provided to staff on risk assessment.

Risk assessments and risk registers

2.9 The risk assessments examined by the ANAO were comprehensive and appropriately identified a range of risks to the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program, with assessed ratings from ‘low’ to ‘extreme’.15 The assessments had been prepared in accordance with the policy and guidelines and identified mitigation strategies, risk levels after applying these strategies, and responsibilities. The assessments recognised that some risks, such as those posed by the extremely remote and harsh environment, would remain at ‘extreme’ irrespective of the mitigation treatments applied by AAD.

2.10 AAD maintains three risk registers to track all risks that have been assessed as ‘high’ or ‘extreme’: a Business Risk Register; a Work Health and Safety Risk Register; and Environmental Aspects and Impacts Risk Registers.16 Under the AAD’s risk management framework, each register should be reviewed and updated annually. There was evidence that this occurs, with the registers current at the time of ANAO fieldwork.

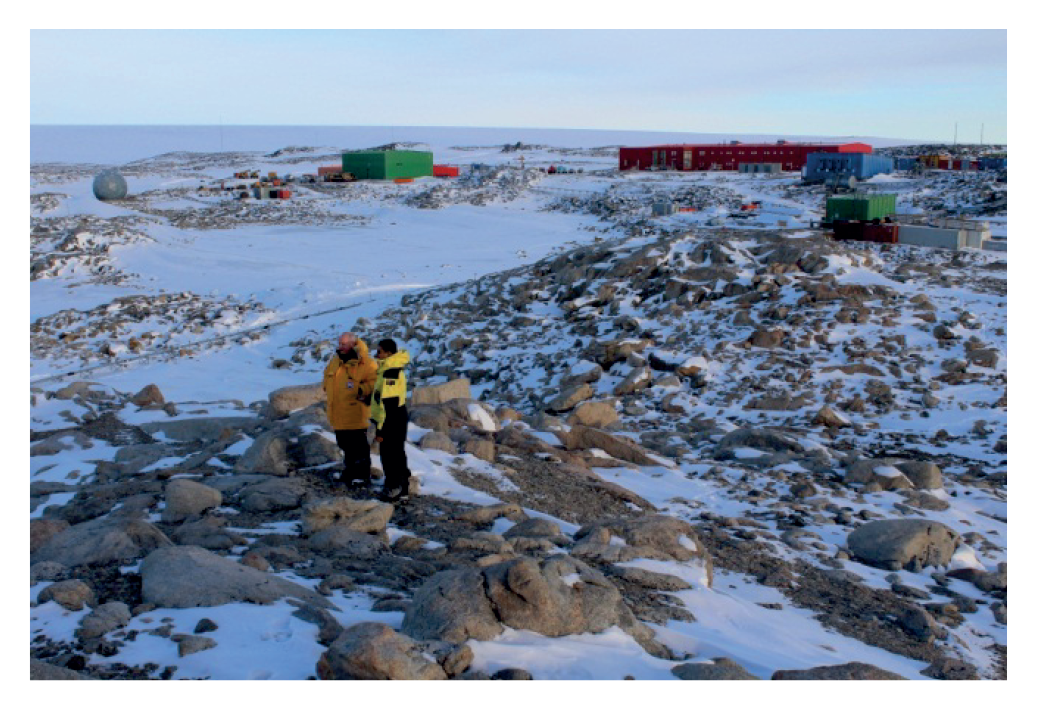

Figure 2.1: Illustration of the challenging environment in which the Antarctic Program is delivered

Source: Photograph, ANAO visit to Casey Station, March 2015.

Monitoring and reporting

2.11 There are suitable risk monitoring and reporting arrangements within AAD and at the departmental level.17 This includes a quarterly risk review by the AAD Executive Committee, and recognition of AAD risks in the department’s Enterprise Risk Register.18 AAD and Environment’s approach to ‘treat and accept’ its severe delivery risk is reasonable, considering the scale and significance of the risk factors involved in the delivery of the Antarctic Program. Nonetheless, it is important for AAD to regularly assess its risk exposure and to consider additional treatments to help mitigate risks to the achievement of program objectives.

Has AAD implemented effective arrangements to provide information to stakeholders about the performance of the Australian Antarctic Program?

While the performance measures established for the Australian Antarctic Program provide insights into the delivery of program activities, they do not clearly indicate the extent to which the overall objectives set for the program are being achieved. To better inform stakeholders about progress towards achieving the Government’s stated outcome and objectives, AAD should improve the effectiveness of its performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the program.

Performance measurement

2.12 Public sector entities are required to set out their outcomes, programs, expenses, deliverables and KPIs in their Portfolio Budget Statements (published as part of the Federal Budget each year) and to subsequently report against these measures in their annual report. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act), which came into effect on 1 July 2014, introduced new arrangements for measuring and reporting performance across Commonwealth public sector entities, including the preparation of corporate plans and annual performance statements.19

2.13 AAD’s activities are included in Environment’s Portfolio Budget Statements under Outcome 3: Advance Australia’s strategic, scientific, environmental and economic interests in the Antarctic by protecting, administering and researching the region.20 AAD’s stated outcome, strategy, objectives and deliverables have remained largely static over the last four years (from 2012–13 to 2015–16). The KPIs identified in each year’s PBS have also remained static, although in the 2015–16 PBS they were presented as a mix of ‘deliverables’ and specific KPIs (this was the case for a number of programs in Environment’s 2015–16 PBS).

2.14 While the current performance measures provide insights into AAD’s activities, they do not clearly outline to stakeholders the extent to which AAD is meeting the established outcome for the Australian Antarctic Program. The recent introduction of the enhanced Commonwealth performance framework provides an opportunity for AAD to review its performance measurement and reporting framework, including the further development of KPIs and the option of introducing additional measurement tools. In undertaking this work, AAD should focus on the development of an appropriate set of performance measures that enable stakeholders to draw clear links between the use of public resources and the results being achieved.21

Recommendation No.1

2.15 To improve accountability and support the effective management of Australia’s Antarctic Program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

- expand existing KPIs and/or develop additional measurement tools to better inform an assessment of the extent to which the objectives for the program are being achieved; and

- publicly report on established performance measures.

Environment’s response: Agreed.

2.16 In accordance with the requirements of the Department of the Environment’s new Evaluation Policy 2015–2020, which was launched in November 2015, for the 2016–17 financial year, the AAD will develop an overarching programme logic and an appropriate suite of performance measures and additional measurement tools in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the performance of Australia’s Antarctic Program. Results of these performance measurement approaches will be publicly reported through the Department’s Annual Performance Statements in the Annual Report for 2016–17 onwards.

External reporting

2.17 The primary means by which AAD reports externally on its performance is through Environment’s annual report. In the department’s annual reports published over recent years22, AAD has reported against the KPIs in the corresponding PBS, as required. In addition to the reported performance against each indicator, the reports have included a broad overview of the program’s achievements. As outlined earlier, the development of a set of relevant, reliable and complete KPIs and the use of additional measurement tools to supplement the use of KPIs would provide more meaningful insights into AAD’s achievements against its objectives.

2.18 In addition to the material produced as part of the annual reporting process, AAD has established a communications program that includes regular media releases, the use of the Internet and social media, and other activities such as public seminars.23 In addition, AAD maintains the Australian Antarctic Data Centre website24, which allows researchers to share data from research conducted in the Antarctic, including Macquarie Island.

2.19 AAD has also established a media program under which at least one media representative is provided with transport and accommodation to an Antarctic station each summer season. While the selection process requires applicants to outline the proposed focus of their work in Antarctica, and agree to AAD’s arrangements regarding logistics, medical clearance and training, AAD does not have editorial control over the content produced or published/broadcast under the media program. The following case study provides information on a recent media program placement.

|

Case study 2. AAD Media Program |

|

In 2013–14, a journalist and a photographer from the Sydney Morning Herald were participants in the AAD’s media program, including travelling on the Aurora Australis for the Casey Station resupply voyage. In addition to a number of articles relating to the Australian Antarctic Program, the journalist and photographer reported on unfolding events on the Aurora Australis as it assisted the Akademik Shokalskiy, a research/tourist vessel trapped in the ice shelf off the coast of Antarctica. |

Source: Sydney Morning Herald online website, available from: <http://www.smh.com.au/interactive/2014/stuck-in-the-ice/> [accessed 13 November 2015].

3. Managing contracts

Areas examined

This chapter examines AAD’s contract management framework and the division’s practices for managing contracts once they are established. The audit focused on established contracts, rather than procurement practices.

Conclusions

AAD has established a sound contract management framework, with contracts managed in accordance with documented contract management principles, including the requirements of the Australian Government’s financial management framework.

In the case of higher-risk contracts, particularly in terms of value and/or their importance to the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program, AAD should formalise contract management arrangements through the development of fit-for-purpose contract management plans.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has suggested that AAD review its guidance materials to staff regarding the management of established contracts, and develop contract management plans for higher risk contracts, which would assist in ensuring consistency of approach across the division.

Introduction

3.1 AAD relies on contracted goods and services to deliver many of its core activities, including goods such as fuel, medical supplies, food and clothing, plant, machinery and parts, and key services such as shipping, aviation, telecommunications, medical screening and training. AAD informed the ANAO that it is the largest purchaser (by volume) within Environment each year entering into around 2500 contracts (the majority valued at less than $10 000).25 In 2014–15, these contracts amounted to expenditure of over $64 million.26

Figure 3.1: The aircraft used in the AAD’s Hobart to Wilkins (Casey) flights

Note: The aircraft is leased and operated through a contract administered by AAD.

Source: Photograph, ANAO, March 2015.

3.2 AAD administers contractual arrangements primarily under two contract types, which are outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Contract types

|

Type |

Description |

Number |

|

Deed of Standing Offer |

An arrangement (Deed) setting out the terms and conditions, including a basis for pricing, under which a supplier agrees to supply specified goods and services to the agency for a set period. Individual contracts are then agreed for specific instances of goods/service provision. |

42 Deeds of Standing Offer (as at 1 July 2015). In 2014–15, AAD entered into 147 individual contracts (valued over $10 000) under these Deeds of Standing Offer. |

|

Contract |

An arrangement where, as a result of a procurement process, an entity enters into a written agreement (contract) for the provision of goods or services from a supplier. |

In 2014–15, AAD entered into 248 contracts valued over $10 000 and 1922 contracts valued under $10 000. |

Source: AAD information. AAD also procures a small number of contracts through whole-of-government panel arrangements, for items such as IT hardware.

Deeds of Standing Offer

3.3 Most of AAD’s Deeds of Standing Offer are for the delivery of key goods/services for the Australian Antarctic Program, such as shipping, aviation, fuel, clothing, food and household supplies, drugs and medical equipment, and health screening services.27 The majority of these deeds are established for a three-year period, with the option to extend for up to two years. This approach provides certainty for both AAD and the supplier, and helps to build sound relationships and supplier expertise in the particular requirements for the Australian Antarctic Program (for example, packaging of goods to meet quarantine requirements).

3.4 While contracts let under Deeds of Standing Offer account for a small percentage of the total number of AAD contracts entered into each year28, approved expenditure on these contracts comprises over 70 per cent ($46.85 million–see Figure 3.2) of AAD’s total contract expenditure.29

Figure 3.2: Value of Deed of Standing Offer contracts, 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender information and information supplied by AAD (regarding shipping costs).

Note: The shipping costs include hire and crew and life extension works for the Aurora Australis. The air transport costs include flights between Hobart and Antarctica, and fixed-wing and helicopter services within Antarctica. The training and clothing costs reflect those that are let under Deeds of Standing Offer. AAD also lets a number of ‘direct’ contracts for these goods/services each year. ‘Other’ contracts are those let under Deeds for a range of goods and services such as: wastewater treatment and disposal, communications services, building and electrical services.

Direct contracts

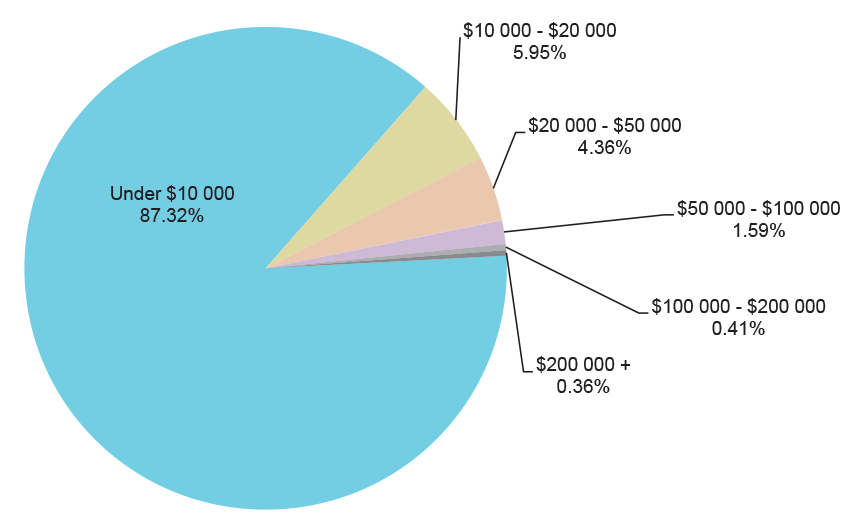

3.5 AAD establishes over 2000 ‘one-off’ contracts each year for a broad range of items (including building materials, machinery parts and trades equipment) and services (including specialist advice). In general, these contracts are low in dollar value, as illustrated in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Value of direct contracts let during 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data (over $10 000) and information provided by AAD (under $10 000).

Has AAD established a contract management framework that includes clear lines of responsibility and accountability, policies and guidance for staff?

AAD has established an appropriate contract management framework based on a ‘decentralised’ approach, whereby individual contracts are primarily managed by staff across line areas. To better support this decentralised operating model, AAD should improve the policies and guidance for its staff with contract management responsibilities. The planned implementation of a centralised contract register should also provide insights into potential areas for improvement in contract management practices.

Roles and responsibilities

3.6 AAD has established a ‘decentralised’ contract management framework, with individual contracts managed by staff in the responsible line areas, with support from AAD’s Contracts and Payments Processing sections. Key contracts (primarily those established under Deed of Standing Offer arrangements) have a dedicated staff member with contract management responsibilities. AAD contract managers interviewed by the ANAO demonstrated a clear understanding of their role in managing deeds and contracts under their responsibility.

Policies/guidance for staff

3.7 AAD has developed a range of policies, procedures and guidance materials for staff regarding procurement, which align with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Commonwealth Procurement Rules. These include a flowchart outlining procurement thresholds and approval requirements, templates for preparation of procurement plans for open and limited tender procurements (across the different dollar value approval thresholds), and links to further training materials and guidance on the Environment and Department of Finance websites.

3.8 In contrast to procurement activities, there is less guidance for AAD staff regarding the processes to be employed for managing contracts once they are executed. As outlined earlier, the majority of contracts let by AAD can be characterised as ‘simple’ in nature and, as a consequence, do not require comprehensive contract management oversight. However, AAD also manages a number of Deeds of Standing Offer and direct-let contracts that have a significant material value and/or impact on the effective delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program. As such, there is scope for AAD to provide its staff with further guidance regarding the management of these contracts, including by developing contract management plans (as outlined further at paragraph 3.13).

Monitoring and reporting contract performance

3.9 In the absence of a centralised, online contract register, AAD manages contracts using a combination of paper-based and electronic files. A centralised contract register can assist entities to meet their financial reporting responsibilities, monitor contract completion dates, and exercise options to extend contracts where it is considered prudent to do so. When linked to an entity’s financial management information system, a register can also provide managers with insights into the contracting activities of their entity and expenditure against contracted commitments.

3.10 In 2015, Environment initiated a project to implement an ‘end-to-end’ system for procurement and contract management, using the department’s existing financial management information system. The department informed the ANAO that the system was expected to be implemented in late February 2016.

Does AAD manage its contracts in line with sound contract management principles?

Overall, AAD manages its contracts in accordance with sound contract management principles, including the requirements established under the Australian Government’s financial management framework. For higher-risk contracts, particularly in terms of value and/or their importance to the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program, AAD should formalise contract management arrangements through the development of fit-for-purpose contract management plans. The establishment of such plans would contribute to more consistent contract management practices across the division and reduce the impact of staff turnover and the resulting loss of corporate memory.

Managing Deeds of Standing Offer

3.11 The ANAO examined whether AAD administered Deeds of Standing Offer in accordance with sound contract management principles (including meeting the Commonwealth’s financial framework requirements). The results of this analysis are outlined in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: ANAO analysis of a sample of Deeds of Standing Offer1

|

Contract management principle2 |

Did AAD practices align with this principle? |

Comments |

|

An executed contract (Deed of Standing Offer) was in place. |

Yes |

All sampled deeds had an executed contract in place. Extensions had been made in accordance with the deed’s conditions, where applicable. |

|

Deeds of Standing Offer and associated contracts were accurately reported on AusTender within 42 days of execution. |

Yes Partially |

Deed details, such as the provider, goods/services to be provided, and the duration of the deed, had been accurately reported on AusTender. In all but one of the sampled deeds, contracts raised under the deeds had also been correctly reported on AusTender. |

|

Contracts (Deeds) adequately set out the expectations for both AAD and the provider, including Key Performance Indicators and contract review mechanisms. |

Yes |

Overall, the sampled deeds clearly set out the requirements for both AAD and the provider. Some older contracts did not include KPIs. AAD indicated this would be addressed when new contracts were negotiated. |

|

A suitable contract management plan is in place, including a risk assessment. |

Partially |

While AAD had a simple checklist for each deed in the sample, it had not prepared a more detailed contract management plan commensurate with the risk that contract failure would pose to the successful delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program (see discussion at paragraph 3.13). |

|

The provision of the good/service commenced after the execution of the contract. |

Yes |

In each of the sampled deeds, there was evidence the good/service was provided after the deed’s execution. |

|

Scheduled reports, meetings and other interactions between AAD and the provider are undertaken. |

Yes |

Overall, there was evidence that AAD had undertaken active management of Deeds of Standing Offer, for example by receiving, reviewing and accepting monthly or quarterly reports from the provider, and by holding and recording meetings to discuss pre-season planning or to conduct a post-season debrief. |

|

Contract payments were satisfactorily managed (correct invoice received; AAD verified satisfactory provision of the goods/service; payments aligned with approved expenditure; payments were approved by a person with the appropriate delegation, and were made within 30 days). |

Yes |

AAD had satisfactorily managed contract payments for sampled deeds. |

|

Processes to address issues in the contract or to manage poor performance are managed in accordance with the contract’s terms and conditions. |

Yes |

Only one of the nine sampled deeds had encountered major issues or poor performance. In relation to this contract, there was evidence of AAD’s attempts to improve contractor performance. However, the issue was eventually addressed by AAD not exercising the option to extend the contract. |

Note 1: The ANAO examined documentation for nine of the 42 deeds held by AAD in 2015 (a 20 per cent sample) and interviewed AAD’s contract managers for the sampled contracts.

Note 2: The contract management principles outlined in the table are based on the Australian Government’s policies and guidance for managing contracts (available from <www.finance.gov.au>) and the ANAO’s Better Practice Guide on Developing and Managing Contracts (2012).

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD and AusTender information.

3.12 AAD has established generally sound contract management practices for the Deeds of Standing Offer reviewed by the ANAO. However, AAD had not reported all of its expenditure on contracts issued under one Deed of Standing Offer during 2014–15 (for the Aurora Australis charter hire, with a total value of around $18 million). To facilitate transparency of the Australian Antarctic Program’s contract costs, and meet reporting requirements under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, this expenditure should have been reported. AAD acknowledged this reporting oversight and stated its intention to ensure that this expenditure information is reported as required.

3.13 The ANAO also noted that AAD had not prepared contract management plans for any of the Deeds of Standing Offer or significant direct-let contracts reviewed by the ANAO.30 The development of such plans would help to clarify management arrangements for these contracts and would also help to ensure continuity of management in the event of staff turnover.

Managing direct contracts

3.14 The ANAO also examined AAD’s management of directly let contracts (that is, not through Deeds of Standing Offer).31 This analysis indicated that AAD had managed these contracts satisfactorily. There was an issue identified relating to the timeliness of reporting contractual information on AusTender, with five of the 49 sampled contracts reported after the required deadline. Four of these were published 22 days or less after the required date. The fifth was published 84 days late.

End of contract evaluation/reporting

3.15 Over recent years, AAD has included performance indicators in many of its Deeds of Standing Offer, with a requirement for payments to be determined on the basis of performance against these KPIs included in some deeds. Performance against KPIs is also taken into consideration by AAD when determining whether a deed will be extended (as per the deed conditions). In a number of the deeds examined by the ANAO, there was evidence that performance against these indicators had been considered by AAD and informed a decision regarding whether the deed would be extended. While an assessment of KPIs provides insights into contractor performance, there is also value in considering and recording ‘lessons learned’ and better practices applied in the management of significant contracts, such as Deeds of Standing Offer, to help build capability across the organisation.

4. Managing assets and inventory

Areas examined

This chapter examines AAD’s: asset management strategy, policies and procedures; approach to maintaining assets; and approach to managing inventory.

Conclusion

AAD’s approach to managing its assets would be improved by the development of an overarching asset management strategy, supported by current policies and procedures. The proposed asset maintenance system, once fully implemented as planned, should provide an effective basis on which to manage AAD’s complex asset maintenance requirements.

AAD has not established an effective inventory management system. While AAD has commenced a project to develop an end-to-end system to manage program inventory, the project has exceeded its initial timeframe and budget, and now has a reduced scope.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving AAD’s strategic approach to asset management and at strengthening the management of IT projects.

Introduction

4.1 Over its more than 60 years of operations in Antarctica, AAD has built and acquired assets ranging from large buildings and infrastructure (such as water treatment facilities), machinery and technology (such as specialised over-snow vehicles) to sophisticated communications equipment. The ongoing management and maintenance of these assets is vital to the safety of expeditioners living in Antarctica and to the efficient delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program.

4.2 AAD values its assets at around $277 million and categorises32 them as:

- buildings;

- infrastructure (for example, waste water treatment facilities, fuel and water tanks);

- plant and machinery, equipment (covering a broad range of items including scientific and medical equipment);

- IT and communications;

- computer software (off-the-shelf); and

- AAD collections (historical artefacts).

4.3 Inventory is a sub-set of assets, usually characterised by a high turnover rate and low individual value when compared to other asset types. AAD’s inventory includes items to be consumed (for example, food, household goods, and machinery/equipment parts) or small items that are used once or multiple times (for example, clothing and footwear).

4.4 The remoteness of the Antarctic stations and their inaccessibility for many months over the course of a year influences AAD’s approach to the management of inventory items. Sufficient food, household items and other consumables must be provided, including a certain level of redundancy, to ensure there are adequate supplies in the event of unforeseen circumstances such as a delay in a resupply voyage.

Does AAD have an effective asset management framework in place, and adequate systems to manage asset maintenance?

The procedures and systems that are in place, in the main, underpin the effective management of the broad range of assets required to deliver the Australian Antarctic Program. To supplement existing arrangements, AAD is implementing a system to better manage asset maintenance that, when fully implemented as planned, should enable the integrated planning and recording of all asset maintenance. In addition to the work being undertaken to establish an asset maintenance system, AAD should establish an overarching, fit-for-purpose asset management policy to better inform asset decision-making over the longer term and ensure that operational-level asset management plans are regularly updated.

Asset management framework

4.5 Given the broad variation in the type, economic life and scale of the assets it manages, it is important for AAD to have in place an appropriate framework to track, manage, repair or replace each asset over time. Ideally, asset management will be incorporated into an organisation’s corporate and strategic planning to assist in:

- planning expenditure for purchasing or building new assets; and

- operating, repairing and decommissioning existing assets.33

4.6 The AAD’s current asset management framework is outlined in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 AAD’s asset management framework

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD information. This figure was developed by the ANAO, in the absence of an AAD-documented framework. The figure is based on the ANAO Better Practice Guide on the Strategic and Operational Management of Assets by Public Sector Entities, September 2010; and International Standard ISO 55000: Asset Management, 2014.

4.7 While AAD has implemented, or is in the process of developing, many of the components expected under a sound asset management framework (as outlined in Figure 4.1), there are a number of areas that require further attention, including:

- AAD’s overarching asset management policy, which was first drafted in 2009, has not been finalised:

- a fit-for-purpose asset management policy/strategy should set out AAD’s strategic goals and the optimal asset base that is necessary to support program delivery requirements and provide an overview of the asset management framework as a whole;

- two operational-level plans (for acquisitions and disposals) had not been reviewed for at least 10 years:

- up-to-date plans should identify priorities, roles and responsibilities, and set out (or reference) procedures that reflect current legislative and departmental policy requirements; and

- maintenance planning is underpinned by an agreed workflow, however, other aspects that would be expected in an operational-level plan, such as an outline of priorities, roles and responsibilities and relevant policies, are not documented.

Recommendation No.2

4.8 The ANAO recommends that, to underpin an effective approach to the management of Antarctic Program assets, the Department of the Environment develop a fit-for-purpose strategic asset management policy supported by asset management plans and procedures that are regularly reviewed and updated.

Environment’s response: Agreed.

4.9 The Department agrees that the AAD’s approach to the management of Antarctic programme assets, which has been found to be generally effective, could be enhanced through the development of an underpinning strategic asset management policy and related planning documents. A new strategic asset planning function is being established and resourced within the Antarctic Modernisation Taskforce to implement this recommendation.

Asset maintenance systems

4.10 Maintenance is a critical activity in the life cycle of an asset, with poor maintenance often leading to a shorter useful life than that envisaged in design specifications. Certain types of assets, such as plant and machinery and fire sprinkler systems, have legislated maintenance schedules (for example, under the Building Code of Australia) to help ensure their safety and reliability.

4.11 Since mid-2011, AAD has used an IT system (Maximo) to manage asset maintenance. Maximo is a commercial off-the-shelf product that includes a number of modules that can be used for asset and inventory management. Prior to the implementation of Maximo, maintenance was largely managed through a series of spreadsheets that contained data on assets, their maintenance history and scheduled maintenance, supported by handbooks and Standard Operating Procedures outlining the maintenance requirements for particular assets. This data has progressively been migrated to Maximo. As at October 2015, data for all mechanical assets (for example, vehicles and cranes) had been entered into Maximo. Data on infrastructure assets (such as buildings) was in the process of being entered. AAD informed the ANAO that it was unable to provide a timeframe for completion of data migration, mainly due to resourcing pressures.

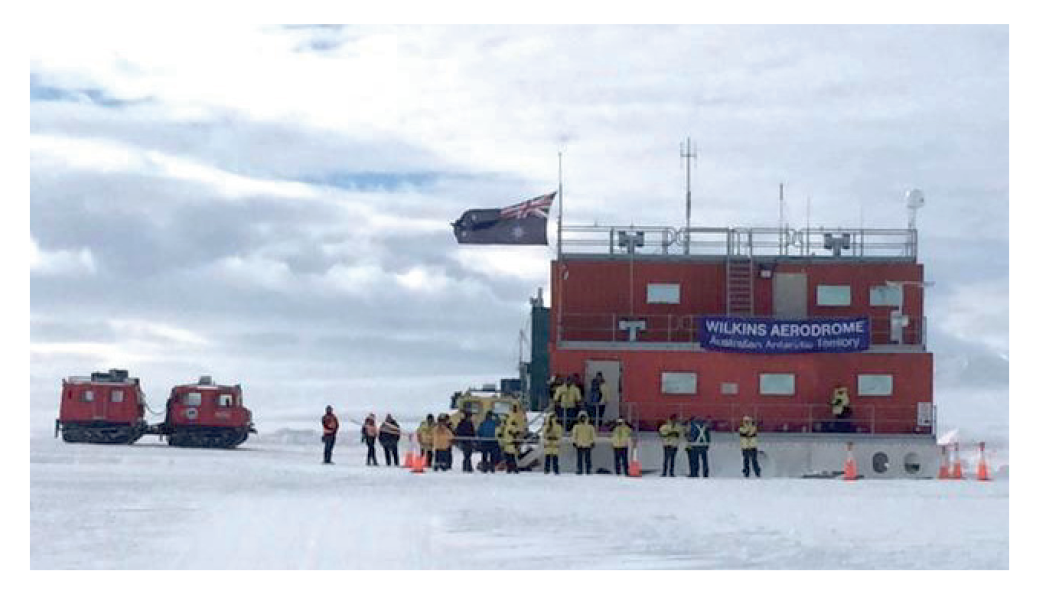

Figure 4.2: Examples of assets managed by AAD include Hagglund over-snow vehicles and the Wilkins Aerodrome buildings

Source: Photograph, ANAO, March 2015.

4.12 Maximo provides a record of asset maintenance history (including for Work Health and Safety compliance) and is used to generate work orders. The system has the capacity to include links to electronic material such as registration certificates, instruction manuals and checklists, and Standard Operating Procedures for maintenance tasks.

4.13 The ANAO’s analysis of data in Maximo indicated that around 3000 work orders were entered into Maximo in 2014–15, with a break-down of the types of work orders provided in Figure 4.3.34

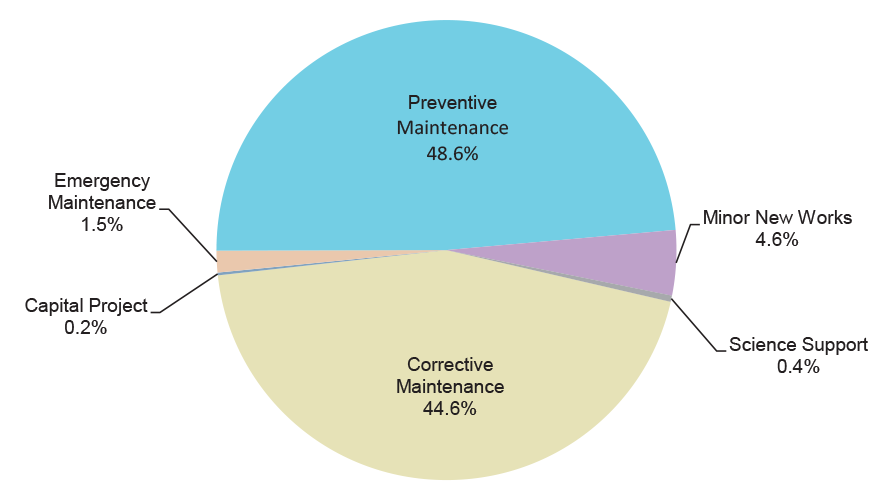

Figure 4.3: Ratio of Work Order types in Maximo, 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD information (percentages have been rounded).

4.14 The ANAO’s analysis identified discrepancies regarding categorisation of work orders. For example, tasks such as servicing were entered as Preventive Maintenance and at other times as Corrective Maintenance. The incorrect categorisation of maintenance work impacts on the accuracy of reports produced from Maximo that are used to inform managers and the AAD Executive. While acknowledging these discrepancies, AAD advised the ANAO that a recent focus on staff training and increased supervision of the use of Maximo had improved accuracy of data entered into the system.

4.15 In relation to data retained by AAD on maintenance activities, the planned or actual labour hours against each work order or the actual dates that maintenance commences and concludes was not consistently recorded.35 As a result, there was a lack of information, apart from anecdotal evidence and corporate knowledge, about those work orders that are most labour-intensive. The collection of additional data on labour usage and completion times would enable AAD to better plan the mix of work orders for any given period and in planning future deployment of expeditioners—for example, upcoming maintenance tasks such as a major service on a piece of equipment, may justify the deployment of additional staff for a summer season. AAD advised the ANAO that it is re-introducing the recording of planned labour hours in Maximo. While AAD had considered also introducing a requirement for staff to enter actual labour hours into the system, ultimately it had decided that any potential benefits would be outweighed by the costs (such as additional resources to train staff, and to verify the accuracy of entered data).

Has AAD implemented a robust inventory management system?

AAD does not have an effective inventory management system in place even though the need for such a system has been highlighted in a number of internal reviews over the last 10 years. While AAD commenced a project in 2012 to develop an end-to-end inventory management system, it is yet to be completed. The project has substantially exceeded its original timeframe and budget, with revisions to the project over time resulting in a significant reduction in proposed system functionality.

Current inventory management

4.16 AAD has not established an integrated IT system to manage and track its inventory items, despite inventory playing a critical role in the success of AAD’s operations. Information on elements of AAD’s overall inventory are retained on a range of databases and/or spreadsheets—for example, a clothing database, medical supplies database, and the ‘WhereIs’ system that receipts goods arriving to the AAD warehouse at Kingston. However, the databases/spreadsheets currently in use are not linked, and they do not track inventory items as they are deployed to an Antarctic station, record where they are stored on-station, or record when they are used and, therefore, need to be re-ordered and delivered on an upcoming resupply voyage.

4.17 AAD manages the provision of supplies based on historic use, with manual stocktakes conducted on-station annually. Under the current approach, AAD intentionally ‘over-supplies’ key items such as food, fuel, household goods, essential machinery and parts, as a means of managing unexpected events. Under this risk-based approach, AAD has accepted that there will be a certain level of inefficiency or ‘waste’, such as excess food spoiling before it can be used. However, AAD’s limited ability to effectively track the location and quantity of its inventory items leads to other, preventable inefficiencies such as: purchasing and shipping items despite excess stock existing on-station (as well as representing unnecessary expenditure, inventory items that are not required consume valuable cargo space on resupply voyages and storage space on-station); and staff on-station taking longer than necessary to locate parts required to undertake maintenance, or not being able to locate them, therefore postponing work until resupply.

4.18 The ability to effectively and efficiently track, locate and re-order inventory would enable AAD to:

- purchase and transport only those supplies that are necessary (taking into account AAD’s desired approach to ‘over-supply’ certain goods);

- minimise wastage and reduce costs for returning waste to Australia36;

- store items in a safe manner (for example, certain chemicals should not be stored in close proximity to other chemicals);

- easily locate inventory when needed, therefore, gaining efficiencies in labour costs, including for asset maintenance activities; and

- facilitate knowledge transfer—each new team on-station relies on information supplied by the outgoing team.

Inventory Management Project

4.19 In response to a number of internal reviews raising similar issues to those outlined above (dating back at least ten years), AAD commenced an Inventory Management Project in 2012. The stated purpose of the project was to deliver an integrated, dynamic, whole of life-cycle inventory management system, at a budgeted cost of approximately $1.6 million. The initial plan was for a new, Maximo-based Inventory Management System to be implemented by the end of 2014. However, as at September 2015:

- the project remained ‘under development’, with delivery of ‘Stage 1’ planned for June 2016; and

- the project’s budget had increased to $2.7 million.

4.20 In 2015, there was renewed impetus within AAD, and from Environment’s Executive, to progress the project. Subsequently, in June 2015, the AAD Executive approved a revised project plan with a significantly reduced scope (as outlined in Figure 4.4 on the following page).

Figure 4.4: Scope comparison—Inventory Management Project

Note 1: Stage one is to include the development of a strategy for the replacement of eCon (not development/implementation of a new system).

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD information.

4.21 AAD documentation indicated that a number of issues had contributed to slower than planned progress on the project, including:

- a decision by Environment (mid-2013) to adopt Maximo as an enterprise-wide system for asset management. AAD delayed its Inventory Management Project to work with the departmental IT teams to integrate AAD’s stand-alone Maximo system with the department’s system (in November 2015 AAD advised that it expected this project to be completed early in 2016);

- AAD’s cargo consignment system (eCon37) becoming increasingly unstable and unreliable. The project team awaited a decision from the AAD Executive about whether/when to replace eCon, as this would have a significant impact on the project’s scope (in December 2015 AAD advised that Stage 1 of the Inventory Management Project now includes the ‘development of a strategy for the replacement of eCon’);

- an APS-wide recruitment freeze during 2014 meant staff vacancies in the project team were not filled;

- the small project team’s time was diverted responding to internal audits on supply chain and project management;

- delays in sourcing expert advisers to assist with the technical aspects of the project, with contractors costing more than planned; and

- disruptions to the 2013–14 shipping schedules, meaning planned work on stations, such as replacing/upgrading storage facilities, could not be completed.

4.22 A number of these factors should have been more effectively managed at either the AAD or departmental level, for example by redeploying appropriately qualified/experienced staff from within the department to address project vacancies. In addition to the matters identified by AAD, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the following two factors had the most significant impact on delivery of the project:

- implementation of planned governance arrangements; and

- lack of adequate planning and resourcing for the project in the early stages.

Governance arrangements

4.23 The Project Plan (approved in August 2012) outlined a governance structure that included a Steering Committee, Project Sponsor and Project Owner and identified roles within the project team. The project was also due to report to the AAD Executive at its monthly meetings. However, the Steering Committee, which planned to meet every six weeks, only met infrequently in the first three years (there were records for two meetings in 2012, none during 2013 and one during 2014). The project team provided monthly project status reports to the AAD Executive in 2013, but this reporting became less frequent as the project stalled from mid-2013. Ultimately, there was a need for greater oversight and involvement from the Steering Committee, particularly when the project lost momentum during 2013 and 2014.

Planning and resourcing

4.24 As outlined earlier, the Inventory Management Project—as originally envisaged—was to involve a significant change to AAD’s supply chain function, bringing together many separate databases/systems and requiring integration with other key AAD systems, including SAP (purchasing) and eCon. The initial project plan underestimated the resources that would be required to deliver the project as originally proposed, and did not consider ongoing costs, such as the number of Maximo licences that would be required for the large number of AAD staff that were expected to use the inventory management system.

4.25 To support sound project delivery practices across the department, Environment has established a project management framework, including templates for planning, budgeting, reporting and a support unit based in Canberra. While the Inventory Management Project team followed aspects of the framework (such as the use of planning and reporting templates), AAD did not regularly draw on the available departmental expertise as the project encountered implementation issues, and in turn, the department’s support unit did not actively support the Inventory Management Project team. A greater involvement of this unit would have assisted AAD to both anticipate and respond to the delivery challenges encountered during implementation of the Inventory Management Project.

4.26 There was considerable scope for AAD to have strengthened governance arrangements and planning and resourcing practices for the project, with identified weaknesses including:

- an over-ambitious project scope given the limited resources that were available;

- a failure to implement planned governance arrangements, in particular regular Steering Committee meetings;

- delayed decisions on the future of key AAD systems; and

- a failure to draw on departmental support and expertise, particularly when project implementation issues became apparent.

Recommendation No.3

4.27 The ANAO recommends that, to support the successful delivery of future Antarctic Program IT projects, the Department of the Environment implement:

- appropriate scoping and detailed budget planning processes to ensure adequate resources will be available to deliver the planned outcomes; and

- sound project governance arrangements.

Environment’s response: Agreed.

4.28 A revised approach to project management has been adopted for the Inventory Management project and other ICT projects at the AAD, providing opportunities to overcome a number of the barriers that the ANAO has identified. The changes include a more systematic approach to up-front business analysis, enhanced processes for management oversight and consultation across the AAD, and closer integration with Departmental ICT planning and project management processes.

5. Recruiting, training and supporting expeditioners

Areas examined

This chapter examines AAD’s recruitment and training activities for expeditioners and the support provided to expeditioners and their families.

Conclusion

AAD’s approach to recruitment of its expeditioner workforce is, in the main, effective, and recognises the need to recruit people with an appropriate mix of technical and social/community skills required to contribute to a successful Australian Antarctic Program.

AAD has suitable training arrangements in place to prepare its expeditioner workforce for Antarctic service. However, AAD is yet to implement a Training Management System (TMS) to improve the management of training records, including tracking the currency of required licences/qualifications for particular roles.

The support services provided by AAD to expeditioners and their families are appropriate, and most expeditioners have expressed satisfaction with AAD’s approach.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has suggested that AAD develop a more strategic approach to its workforce recruitment activities and prioritise the implementation of a Training Management System to provide appropriate management of its training records.

Introduction

5.1 Each year, AAD recruits and trains a diverse workforce of ‘expeditioners’ to support the operations of its Antarctic stations. Employment in these seasonal, non-ongoing positions can run from a period of a few weeks to 20 months. AAD recruits for a wide range of positions at its Antarctic stations each season.38 As well as assessing applicants’ technical abilities, AAD’s selection process has a particular focus on selecting people with personal qualities who will contribute to a harmonious and productive community on-station. Given the isolated work environment and the limited ability to replace personnel (particularly over winter), AAD conducts a comprehensive multi-stage selection process, designed to minimise the risk of selecting unsuitable expeditioners.

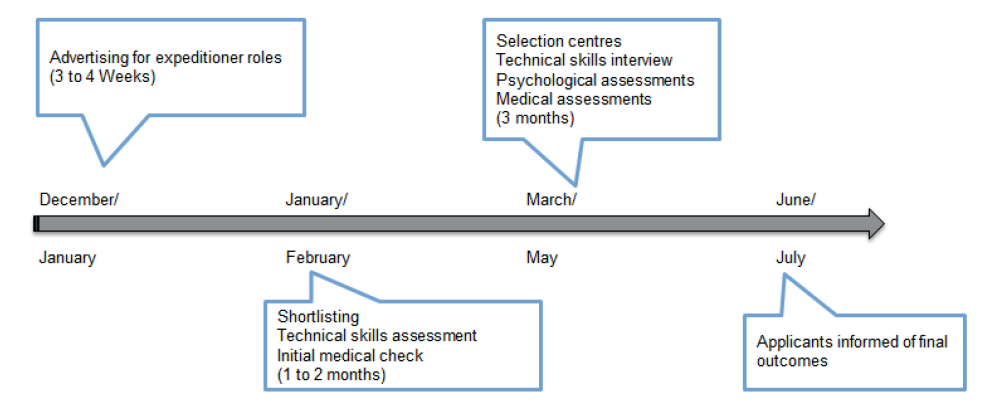

5.2 The stages and timeframes of AAD’s selection process are outlined in Figure 5.1. There are around 180 offers of employment made each year out of around 2000 applications.39

Figure 5.1: Stages of expeditioner selection process

Source: ANAO analysis of AAD information.

5.3 The two key components of AAD’s selection process are selection centres and psychological assessments:

- Selection centres involve groups of applicants taking part in a series of group exercises over two half days, which simulate living and working on an Antarctic station. AAD uses a panel of six assessors to observe behaviour and identify any concerns about the applicant’s suitability for station life. For the 2014–15 season, AAD conducted 14 selection centres in Hobart, Brisbane and Adelaide, attended by 240 applicants. It costs AAD around $250 000 per annum to conduct selection centres (half of its recruitment budget).

- Individual psychological assessments are also used to select a suitable mix of personnel. The assessment consists of: the completion of a consent form; personality screening using a questionnaire; and a face-to-face interview. The assessment culminates in a written report. The assessment also provides an opportunity for education of the applicant, helping them to prepare for Antarctic employment should they be successful.

Does AAD have an effective approach to recruiting and training its expeditioner workforce?

AAD has established sound recruitment approaches, including the provision of training, guidance and specialist support to those conducting recruitment processes, and refining arrangements on the basis of feedback from applicants. There are also suitable training arrangements in place to prepare the expeditioner workforce for Antarctic service, with a series of reviews conducted by AAD to identify areas for improvement. AAD is, however, yet to implement a Training Management System (TMS)—which was recommended by an internal review in 2010—to improve the management of training records.

Workforce planning and retention strategies

5.4 AAD staff informed the ANAO of a range of the organisation’s key workforce risks and challenges, including:

- competition from other industries for skilled labour (for example, the mining sector is considered to have drawn potential applicants away from the AAD);

- key skills shortages (for example, AAD has had difficulty attracting doctors to take up the critical positions of polar medical officers on Antarctic stations); and

- expectations that the Australian Antarctic Program’s objectives will continue to be delivered from a declining funding base.

5.5 AAD has not, however, established a workforce plan for its expeditioner workforce.40 The development of such a plan, underpinned by a workforce risk assessment and analysis, would enable AAD to better manage its workforce needs over the short, medium and longer term. As AAD has mature planning frameworks in place to prepare for each season’s operations, workforce planning would complement these existing planning activities, integrating strategic considerations relating to challenges to the expeditioner workforce with operational and business planning.

5.6 Retention refers to expeditioners applying for another season of Antarctic service, with around 40 per cent of expeditioners returning for employment in a future season. Experienced expeditioners help new recruits adapt to station life and are familiar with long-term projects (for example, infrastructure or science projects that are delivered over several summers). AAD’s considerable investment in training is also lost when expeditioners do not return.

5.7 AAD is attempting to lift the expeditioner retention rate by: