Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Strategies and Activities to Address the Cash and Hidden Economy

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office's (ATO) strategies and activities to address the cash and hidden economy.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) defines the cash and hidden economy (cash economy) as: businesses that deliberately hide income to avoid paying the right amount of tax or superannuation, which they mainly do by not recording or reporting all of their cash or electronic transactions. The ATO considers that the cash economy is most prevalent in the small business market segment, where approximately 1.6 million small businesses operating across 233 industries are more likely to have regular access to cash.

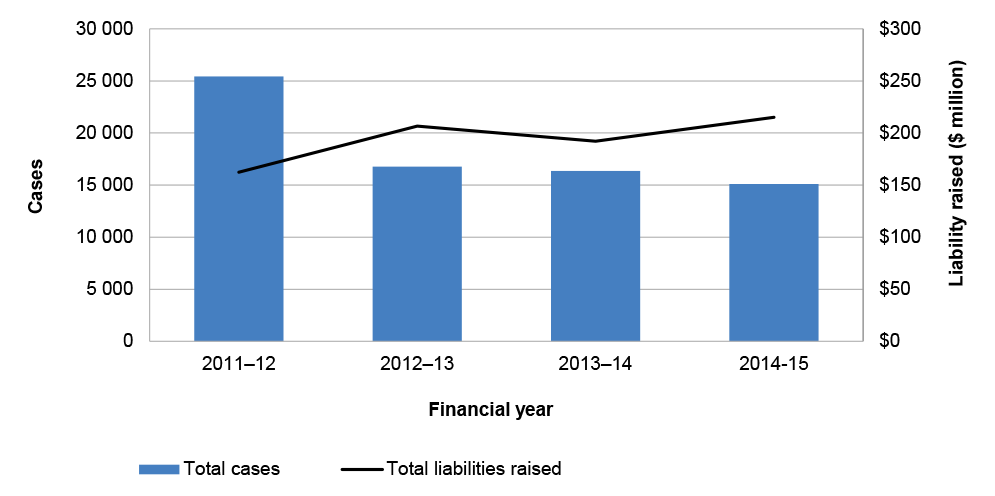

2. The ATO has identified the cash economy as a major tax integrity risk. The risk is managed by approximately 400 ATO staff, with a budget of $39.5 million in 2015–16. In the four years from 2011–12 to 2014–15, the average annual liabilities raised by the ATO from compliance activities with small business taxpayers to address the cash economy was $192.6 million, and an average annual of $114 million in cash was collected.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s strategies and activities to address the cash and hidden economy. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- effective management arrangements support the compliance strategies and activities;

- compliance risks are effectively identified and guide case selection; and

- compliance activities are conducted effectively to treat risks.

Conclusion

4. The ATO’s strategies and activities to address the cash and hidden economy are consistent with international approaches and guidance provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.1 The ATO’s planning, liaison and reporting arrangements have been sound, and risk management activities and case selection processes have supported increasingly cost-effective compliance cases being conducted with taxpayers in recent years.

5. The ATO is meeting its own revenue targets for compliance activities with taxpayers for the cash economy risk. However, the overarching strategic framework that guides the ATO’s cash economy activities does not contain defined indicators and targets for its success measures and the ATO is yet to measure its progress in implementing the new multi-year strategic framework, which was introduced in 2014–15.

6. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates that the cash economy has remained stable at up to 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product for the ten years to 2010–11.2 However, there is no robust estimate of the revenue at risk3 from the cash economy. Without a robust estimate of the revenue at risk, the effectiveness of the ATO’s activities on the cash economy cannot be reliably assessed. In 2016, the ATO intends to estimate the revenue at risk for the cash economy as part of its program to produce a range of estimates of small and medium business income tax gaps.4 The ATO could use this analysis to measure the impact of its current activities on the cash economy, and to determine the nature and extent of its future strategies and activities to address the cash economy.

Supporting findings

Management arrangements

7. The ATO established an overarching strategic framework in 2014–15 to address the cash economy—the Community Participation Assurance Framework. However, the framework lacks measures of success for its specified outcomes. While the framework has been supported by sound planning, liaison and staff capability arrangements in the ATO, various organisational changes have limited the level of assurance that can be given about the effectiveness of current management arrangements.

8. The ATO has regularly evaluated the effectiveness of its cash economy activities. While earlier evaluations were largely inconclusive due to data limitations and difficulty in attributing results to treatment strategies, a 2014 evaluation was positive and proposed future reviews of the risk. Additional reviews were not conducted during this audit.

9. The governance and reporting framework for the cash economy in the business line supports reporting processes. While there are no program-level performance indicators, the ATO’s cash economy activities are included in recent ATO annual reports, and are of ongoing interest to the Parliament.

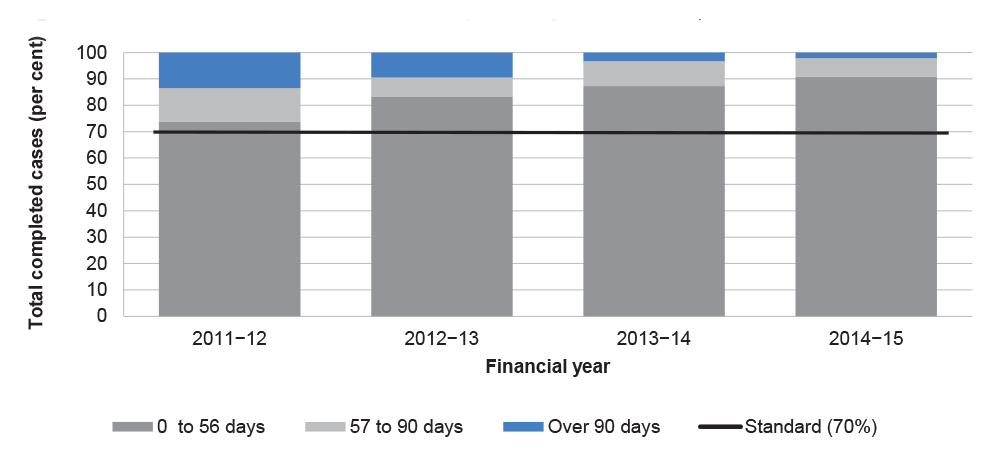

10. The revenue raised and cash collected from compliance activity for the cash economy was included in management reports in the former ATO business line administering that work.5 While monitoring was largely adequate, the project for one recent cash economy Budget measure was closed despite the ATO not having monitored whether a commitment made to the Government to raise indirect revenue from compliance activity had been met.

Risk management and case selection

11. The ATO has adequately defined and managed the cash economy risk by having in place a current and sufficiently detailed risk assessment, risk treatment plan and schedule for reviewing the cash economy risk, which collectively meet the corporate requirements for risk management. Additionally, a formal methodology is in place to prioritise and treat emerging issues for the cash economy.

12. While the risk population has been clearly identified, and the ATO has conducted some analysis, it does not have a robust estimate of the level of revenue at risk from the cash economy. The ATO should publish an annual estimate of the revenue at risk from the cash economy, which it has committed to doing in 2016.

13. The ATO has established effective processes for selecting cases for compliance activity, based on an assessment of risk. Multiple sources of information support the operation of two key risk tools for case selection: small business benchmarks and the Unrealistic Business Income model. The ATO is strengthening its processes for selecting cases for cash economy compliance activity, and there is also scope to streamline the process for allocating cases to the compliance teams.

Conducting compliance activities

14. The range of compliance activities undertaken by the ATO to address the cash economy —audit, obligation enforcement and review—is consistent with the practices of revenue bodies internationally and reflects a number of core elements identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as present in comprehensive strategies to address the underground economy. The compliance activities are based on determining and responding to the risk of businesses, industries and the community participating in the cash economy.

15. The ATO’s cash economy compliance activities are typically meeting internal performance targets, such as for liabilities raised and the timeliness of case completion. However, as no measures of effectiveness are in place, it is difficult for the ATO to assess the extent to which its compliance activities contribute to, and align with, the outcomes of the cash economy strategic framework. Developing measures of effectiveness as part of the Community Participation Assurance Framework would assist the ATO to determine the nature and extent of its future compliance activities to address the cash economy.

16. Cash economy compliance cases had only around half the return on investment of the average compliance cases the ATO conducted in 2015. While there are indications of increasingly effective case selection, the ANAO identified further opportunities for the ATO to improve the selection of cash economy compliance cases. By adjusting case selection parameters the ATO could take into account the: potential average liability that could be raised; distribution of cases across industries; size of the industry’s high risk population; and impost on lower risk industries of high case numbers.

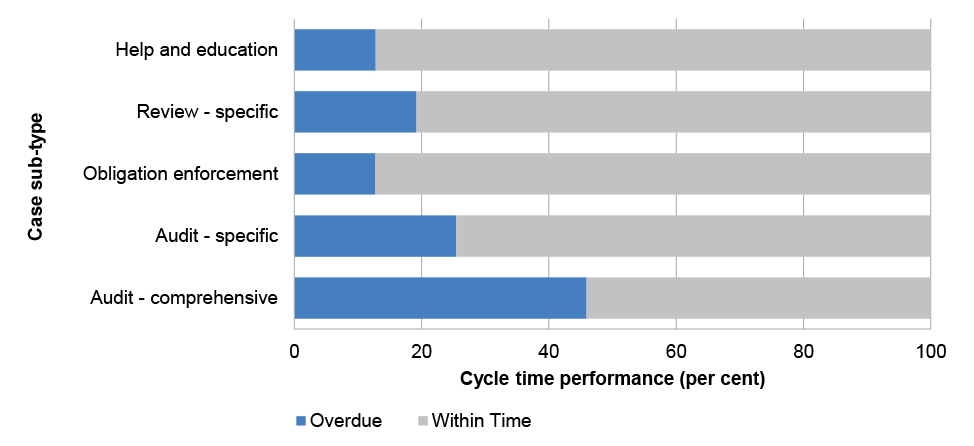

17. Even though over 80 per cent of compliance cases with taxpayers were completed within the allocated time for the ATO to conduct the case, the more complex audit and review cases that produce higher liabilities were more likely to be overdue. This means the ATO could improve the timeliness of its more complex cash economy review and audit cases.

Help and education

18. The ATO’s cash and hidden economy communications framework sets out the business intent, objectives and key messages for help and education activities that address the cash economy risk. The framework is evidence based and complemented by strategic activities that target specific groups and emerging cash economy risks identified through the ATO’s risk based work.

19. The ATO website provides a wide range of general and targeted information about the cash economy risk, including information on the small business benchmarks. Targeted information is consistent with the ATO’s omitted income risk assessment and risk treatment plan.

20. The ATO measures the audience reach of individual communication products, but has not comprehensively evaluated the effectiveness of its cash economy help and education activities against the evaluation measures in annual communications frameworks. Consequently, it has not measured the value for money from these activities. To measure behavioural change, the ATO conducts community and business surveys and, in 2015, developed evaluation measures for three targeted industry strategies. While not having completed this work, the ATO advised that initial results were promising.

Quality assurance and objections

21. The ATO has implemented processes that effectively assure the quality of cash economy compliance decisions and takes corrective actions to address identified issues. While the maturity of assurance processes varies, the current arrangements provide a sound foundation for continuous improvement of staff capability and the quality of cash economy compliance decisions.

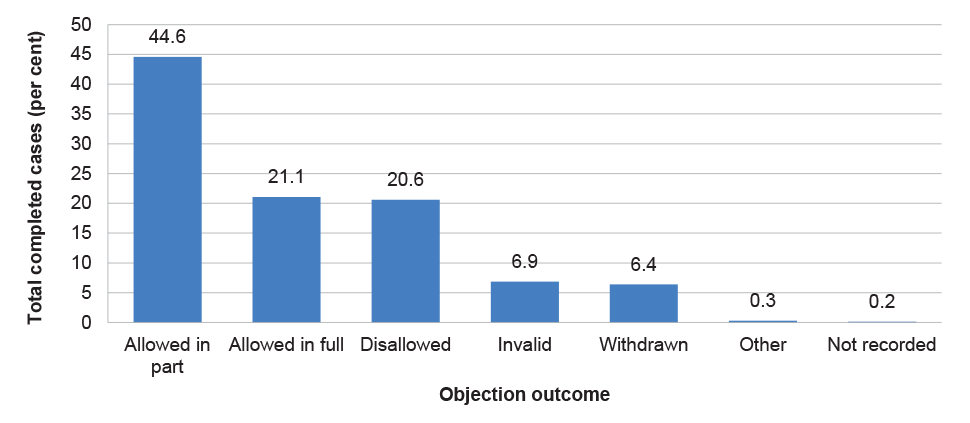

22. The number of objections and complaints made against cash economy compliance decisions is relatively low. Over four years (2011–12 to 2014–15), the ATO consistently exceeded and improved its performance against the timeliness service standard for completing objections against cash economy compliance decisions. Over the same period, objection decisions were subject to relatively few appeals (seven per cent).

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.6 |

To measure progress in achieving the outcomes in the ATO’s Community Participation Assurance Framework and to guide its future cash economy compliance activities, the ANAO recommends that the ATO establishes and reports against defined indicators and targets for the measures of success in the framework. ATO response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 2.25 |

The ANAO recommends that the ATO reports on the achievement of indirect revenue targets associated with Federal Budget funding for ATO cash economy activities. ATO response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

23. The ATO’s summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to managing the cash and hidden economy. The review recognises that our new approach is consistent with international approaches, that our planning, liaison and reporting arrangements are sound, our activities are increasingly cost effective and considerable attention was given to identifying and documenting how we would measure our success in tackling a problem that challenges all governments. The ATO agrees with the two recommendations contained in the report.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 In Australia, and similar countries internationally, the cash and hidden economy (cash economy) is a constant presence in the domestic economy. Sometimes also referred to as the ‘shadow’, ‘non-observed’ or ‘underground’ economy, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) defines the cash economy as referring to businesses that deliberately hide income, from cash or electronic transactions6, to avoid paying tax or superannuation obligations on the income they receive. The operation of the cash economy is a major, longstanding tax integrity risk for the ATO.

Scale of the cash economy and participants

1.2 By its nature, the size of the cash economy is difficult to measure and while the ATO has undertaken some analysis in this area, it does not have an estimate of the level of revenue at risk from cash economy activities. The ATO does however consider that the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest estimate (2013) of the non-observed economy—1.5 per cent of gross domestic product—sets an outer limit for the potential size of the cash economy.7 The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ estimate of the non-observed economy remained stable, at approximately 1.5 per cent, for the ten years from 2000–01 to 2010–11.

1.3 The ATO has identified that the population at risk of operating in the cash economy is approximately 1.6 million businesses (mostly micro and small businesses with an annual turnover up to $15 million) operating across 233 industries that are more likely to have regular access to cash. The ATO has also identified that 58 of those industries are at a higher risk of operating in the cash economy, particularly restaurants, cafes and takeaway businesses, building and construction, and personal services (hair and beauty). Owners of those types of businesses deal directly with their customers and can avoid their taxation and other obligations by under-reporting income, understating cash receipts, and/or overstating business expenses.

1.4 While cash remains the common payment method for low-value transactions, accounting for approximately 70 per cent of payments under $20, the amount of cash used in everyday transactions is decreasing.8 Cash transactions have declined for a number of reasons, including the adoption of electronic forms of payment, growth of online sales, and the introduction of contactless card payments such as eTags. There is evidence that businesses are using sales suppression software to manipulate records created by electronic cash registers or computerised point of sale systems to avoid their taxation obligations.9

Strategies and activities to address the cash economy

1.5 A 2012 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report10 described the approaches adopted by 26 revenue bodies (including Australia) to address the underground economy. While the report indicated that few revenue bodies had comprehensive strategies to address the problem at that time, eight core elements were identified from the existing strategies:

- whole of revenue body coordination;

- comprehensive research efforts;

- enhanced risk detection;

- a broad set of treatment strategies;

- effective whole-of-government cooperation;

- leveraging off key intermediaries such as tax practitioners and industry representatives;

- wide use of media; and

- evaluation of the effectiveness of compliance strategies.

1.6 Following the ATO’s participation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s report, the ATO’s approach to treating the cash economy risk shifted in 2014–15. From focusing primarily on audit activities, the ATO moved to a broad omitted income focus on registration, lodgment and correct reporting by small businesses as part of an overarching community participation and assurance framework. The strategies comprise two elements: community participation and engagement, using a range of media and social media channels; and compliance activities, including taxpayer audits and reviews.

1.7 The ATO uses risk assessment tools to automate the identification and risk assessment of non-compliant taxpayers. These tools draw on a range of data sources, including ATO internal data, industry data and third-party data (from merchants and financial institutions) and information from electronic retailers, community and other external referrals, and media information.

1.8 The ATO’s cash economy strategies and activities are primarily being conducted by 379 full-time equivalent staff in the Small Business line of the Client Engagement Group. The total budget for the cash economy function in 2015–16 was $39.5 million.

Compliance activity outcomes

1.9 In the last four years (2011–12 to 2014–15), the ATO completed approximately 74 000 compliance cases with taxpayers (an average of 18 500 cases annually). Figure 1.1 shows that the ATO raised an average of $192.6 million in liabilities annually and exceeded revenue targets for the cash economy for three of the previous four years.

Figure 1.1: Cash economy revenue details, 2011–12 to 2014–15

Source: ATO advice.

1.10 In the last four years, the ATO also finalised 1281 objections relating to cash economy cases—an objection rate of 7.1 per cent.11 The ATO collected an average of $114 million annually from cash economy compliance cases in the last four years.

Audit approach

1.11 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s strategies and activities to address the cash and hidden economy.

1.12 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- effective management arrangements support the compliance strategies and activities;

- compliance risks are effectively identified and guide case selection; and

- compliance activities are conducted effectively to treat risks.

1.13 The ANAO designated the ATO as the sole audited entity. Audit fieldwork was largely conducted between June and September 2015. During this time, the audit team: reviewed documentation and interviewed key staff at a number of ATO sites; analysed data for compliance activities, such as closed compliance cases, penalties, objections and appeals; and consulted with a broad range of stakeholder groups, including government entities, industry and taxation stakeholder groups.

1.14 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $520 000.

2. Management arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the ATO has effective management arrangements, including a strategic framework that aligns planning, operational activities and performance reporting activities, to support cash economy compliance strategies and activities.

Conclusion

Since 2014–15, the ATO has been implementing a new multi-year strategy aimed at providing a framework to address the cash economy. Planning, liaison and staff capability aspects of this framework have been sound, although the framework does not contain measures of success for its specified outcomes. In November 2015, the ATO moved the cash economy activity to a new organisational structure, which impacts on the level of assurance that can be given about the effectiveness of the current management arrangements. While monitoring the outputs from cash economy compliance activities has been adequate, a project for a cash economy Budget measure was closed without reporting on the achievement of indirect revenue targets.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at: measuring the outcomes from the strategic framework for the cash economy; and improving the ATO’s monitoring and reporting on revenue commitments for cash economy Budget measures. The ANAO also suggested (paragraph 2.5) that the ATO include the results from surveys of tax practitioners, industry associations or ATO staff working on the cash economy as indicators of progress against some of the high-level outcomes in the strategic framework for addressing the cash economy risk.

Is there a strategic framework, supported by adequate planning, liaison and staff capability arrangements, for managing the cash economy risk?

The ATO established an overarching strategic framework in 2014–15 to address the cash economy—the Community Participation Assurance Framework. However, the framework lacks measures of success for its specified outcomes. While the framework has been supported by sound planning, liaison and staff capability arrangements in the ATO, various organisational changes have limited the level of assurance that can be given about the effectiveness of current management arrangements.

Community Participation Assurance Framework

2.1 In 2012, an Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development forum, focusing on tax administration, recommended that revenue bodies consider the merits of developing an explicit overarching strategy to address tax compliance issues for their respective underground economies.12

2.2 Beginning in 2013–14, the ATO has been developing an overarching strategic framework for the cash economy, the Community Participation Assurance (COMPASS) Framework. The framework guides the ATO’s planning and operational activities for the cash economy risk. The ATO considers that COMPASS is a living document that summarises a new, expanded strategy for addressing the cash economy over the next three to four years. Table 2.1 outlines the proposed outcomes, measures of success and actions of the framework.

Table 2.1: Summary of the Community Participation Assurance (COMPASS) Framework, 2014–15

|

Outcome |

Measure of successa |

Actions |

|

Increasing community confidence:

Increases in:

Decreases in:

Ourselves:

|

Engaging with the community:

Working with our staff:

Managing our risk and work:

|

Note a: The framework contains a total of 15 ’measures of success’, which without clearly defined indicators and specified targets are unable to be measured and reported against.

Source: ATO, COMPASS Framework.

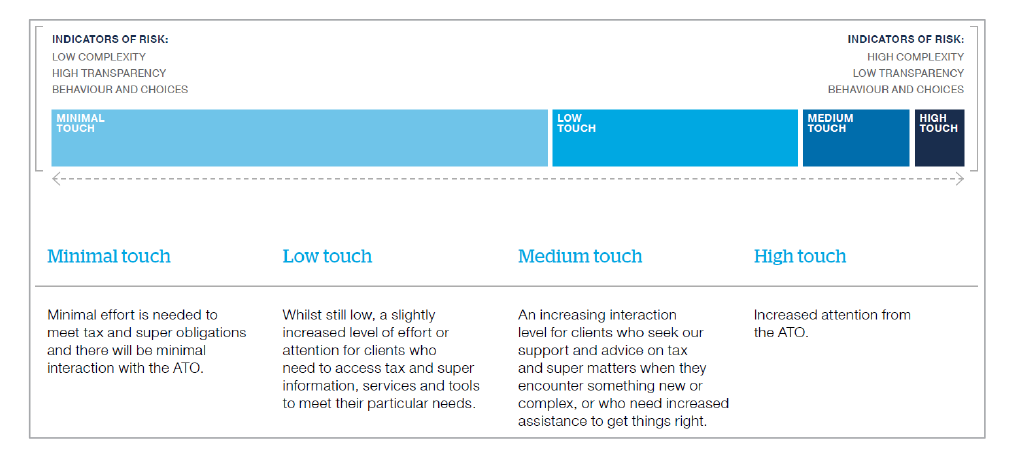

2.3 The framework explicitly incorporates the ATO’s risk based approach to engagement with people in the taxation and superannuation systems, from low risk (minimal touch) to high risk (high touch), and aligns the corporate approach to relevant cash economy activities. Figure 2.1 shows the approach of the ATO and COMPASS to differentiating treatments and minimising unnecessary compliance costs.

Figure 2.1: ATO tailored engagement based on risk

Source: ATO advice 2016.

2.4 In COMPASS: minimal–low touch is estimated to apply to 81.7 per cent of the target population; medium touch, 17.5 per cent; and high touch, 0.8 per cent. In 2015–16, ATO staff who deliver compliance activities for the cash economy receive technical support that is accessible, timely and addresses identified staff training needs.

2.5 The current version of COMPASS includes aspirational and operational statements that do not include details of how the high-level measures of success are to be measured. As the ATO already has the ability to measure community confidence through surveys, it could—through surveys of tax practitioners, industry associations or ATO staff working on the cash economy—include the results as indicators of progress against some of the outcomes in COMPASS. As discussed in Chapter 4, these measures of success would assist the ATO to determine the nature and extent of its future compliance activities to address the cash economy.

Recommendation No.1

2.6 To measure progress in achieving the outcomes in the ATO’s Community Participation Assurance Framework and to guide its future cash economy compliance activities, the ANAO recommends that the ATO establishes and reports against defined indicators and targets for the measures of success in the framework.

ATO response: Agreed.

2.7 As noted in the report, the ATO regularly evaluates the effectiveness of its cash economy activities. These evaluations are done at the program level (including work currently underway to measure a range of small and medium business income tax gaps) and at the tactical level, for specific industry focus areas.

2.8 The ATO is committed to improving the measurement of the outcomes of the work it undertakes across the range of activities it carries out to improve willing participation in the tax and superannuation systems. In developing the measures of success for its overarching framework for the cash and hidden economy the ATO will utilise a range of existing and new indicators and targets.

2.9 From 2011 to October 2015, the cash economy risk and related compliance activities were managed in another ATO business line—the Tax Practitioner, Lodgment Strategy and Compliance Support line. Effective from 1 November 2015, the cash economy activity and 379 full-time equivalent staff were integrated into a new Small Business line in the Client Engagement Group, which is the focal point for the ATO’s interaction with small business. A new Small Business line plan for 2015–19 is to include the cash economy work. The combination of this recent organisational change, the ongoing Reinventing the ATO program13 and the ATO’s commitment to the Government of reducing staffing levels by more than 3000 since July 2013, limits the level of assurance that can be given about the effectiveness of the ATO’s current management arrangements for managing the cash economy risk.

Liaison within ATO and with external forums

2.10 To support its work on the cash economy, the ATO has established liaison arrangements across different areas of the organisation, whole-of-government and internationally, which informs it about current and emerging issues, as shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Summary of liaison arrangements for the cash economy

|

Liaison arrangement type |

Activity |

|

ATO Client Engagement Group forum with other business lines |

|

|

Joint activities with other business lines in the Client Engagement Group |

|

|

Domestic forums |

|

|

ATO consultation groups |

|

|

International forums |

|

Source: ANAO research and analysis of information provided by the ATO during audit fieldwork, 2015.

Does the ATO evaluate performance and report on cash economy outcomes?

The ATO has regularly evaluated the effectiveness of its cash economy activities. While earlier evaluations were largely inconclusive due to data limitations and difficulty in attributing results to treatment strategies, a 2014 evaluation was positive and proposed future reviews of the risk. Additional reviews were not conducted during this audit.

The governance and reporting framework for the cash economy in the business line supports reporting processes. While there are no program-level performance indicators, the ATO’s cash economy activities are included in recent ATO annual reports, and are of ongoing interest to the Parliament.

Applying the Compliance Effectiveness Methodology

2.11 Since 2009, the ATO has been using a Compliance Effectiveness Methodology to measure whether the ATO’s compliance strategies have achieved positive and sustainable change in people’s tax compliance behaviour in a way that builds community confidence.

2.12 The Compliance Effectiveness Methodology was first applied to the cash economy risk in 2009 and the approach has evolved over time, including the strategies, goals and indicators of success. Both ATO Internal Audit (2012–13) and the ANAO (2013–14)14 have reviewed elements of the Compliance Effectiveness Methodology’s application to the cash economy and reported positively on the process. Table 2.3 sets out the two most recent Compliance Effectiveness Methodology evaluations for the cash economy that were completed, in 2013 and 2015.

Table 2.3: Current Compliance Effectiveness Methodology evaluations

|

Year / Focus of evaluation |

Success goals |

Indicators |

ANAO assessment |

|

August 2013 Cash Economy Macro Compliance Effectiveness |

6 |

19 Quantitative and qualitative |

Effectiveness results were mixed with limitations due to data unavailability and specific results not being attributable solely to the ATO’s treatment strategy. |

|

April 2015 Cash Economy Small Business Benchmarks |

4 |

18 Quantitative and qualitative |

Effectiveness results were mixed with limitations due to: data complexity; lack of evidence to support indicators; and specific results not being attributable solely to the ATO’s treatment strategy. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Compliance Effectiveness Methodology evaluation reports.

2.13 The ATO has no further Compliance Effectiveness Methodology evaluations currently planned that would assist with improving the compliance strategies and making resource decisions for the cash economy risk. The ATO advised that its future investments in cash economy activities are to be evaluated alongside evaluations of other key investments in compliance activities within the Client Engagement Group.

Annual review of the cash economy strategy

2.14 In late 2014, the ATO reviewed the cash economy strategy and provided the information to the ATO’s Audit and Risk Subcommittee in 2015. In considering the desired outcomes from COMPASS, the review positively assessed the effectiveness of the treatment strategies.15 The review’s commentary on the effectiveness of the ATO’s treatment strategies included: reference to a sample of cash economy industries that showed that compliance levels were either maintained or there was no significant decline over a ten-year period; and noted, since 2011, a general upward trend in community confidence about the ATO’s ability to deal with people who did not declare all of their income.

2.15 Future reviews of the risk were proposed with an increased focus on: evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment strategy; and consulting with industry and the tax profession about ways to effectively address the cash economy risk. No such reviews were conducted while this audit was being undertaken.

Governance and reporting

2.16 Topical matters for the cash economy risk are reported and discussed at various operational, planning and strategic forums in the ATO. Meetings are held routinely, for example, weekly Directors’ meetings and monthly Executive meetings for the business line and the ATO Executive. However, there are no specific performance indicators for the cash economy risk in ATO business line plans.

2.17 While the cash economy was not referred to in the Department of the Treasury’s Portfolio Budget Statements for the ATO in the last four years, advice is contained in the ATO’s annual reports for the same period that includes activities undertaken to address the cash economy. The topic is also regularly raised in parliamentary committee hearings, for example, by the Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue.

Is the ATO adequately monitoring revenue targets and collections?

The revenue raised and cash collected from compliance activity for the cash economy was included in management reports in the former ATO business line administering that work. While monitoring was largely adequate, the project for one recent cash economy Budget measure was closed despite the ATO not having monitored whether a commitment made to the Government to raise indirect revenue from compliance activity had been met.

2.18 Two key management reports (Dashboard and Snapshot) are used in the Tax Practitioner, Lodgment Strategy and Compliance Support business line to monitor and report on base (business as usual) compliance activities and separate Federal Budget revenue commitments to government. The reports are produced monthly and at the end of the financial year and are available to both operational and Executive staff in the business line. The Snapshot report contains detailed views of planned and actual performance, and commentary explaining any variances.

2.19 Table 2.4 sets out the cash economy revenue details for the previous four years (2011–12 to 2014–15). The total liabilities raised from compliance activities for the period was $770.5 million, and cash was collected of $456.2 million.

Table 2.4: Cash economy revenue monitoring, 2011–12 to 2014–15

|

|

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Revenue target ($m) |

145.5 |

173.5 |

230.9 |

218.2 |

|

Liabilities raised ($m) |

157.0 |

193.8 |

197.3 |

222.4 |

|

Strike ratea (per cent) |

28.6 |

57.1 |

63.0 |

53.2 |

|

Cash collected ($m) |

94.1 |

119.1 |

114.3 |

128.7 |

Note a: A compliance activity strike rate is the number of audit and enforcement cases completed with a result, as a percentage of all audit and enforcement cases completed. An outcome includes debits, credits or notional tax recorded against the case.

Source: ATO advice, 2015.

2.20 The ATO’s cash economy revenue target, which is based on liabilities raised, was exceeded for three of the previous four years. While revenue targets and the liabilities raised differ between ATO business lines, the cash collected in the Tax Practitioner, Lodgment Strategy and Compliance Support business line in 2012–13 for the cash economy compares favourably to other business line outcomes that year:

- Tax Practitioner, Lodgment Strategy and Compliance Support—cash collected for the cash economy—61 per cent (from liabilities raised of $193.8 million);

- Small Business/Individual Taxpayers—cash collected for capital gains tax from small businesses—28 per cent (from liabilities raised of $54.2 million)16; and

- Private Groups and High Wealth Individuals—cash collected for High Wealth Individuals—26 per cent (from liabilities raised of $1067 million).17

2.21 To increase the attention given to actual revenue raised, the ATO should consider setting targets for cash economy cash collection amounts, in addition to, or in place of, targets for liabilities raised.

Federal Budget funding measures

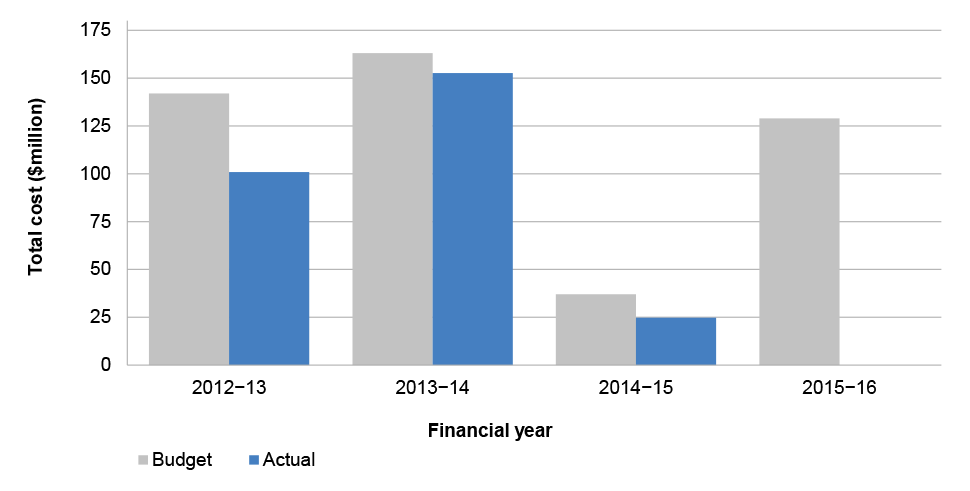

2.22 Since 2009–10, the ATO has received additional funding in the Federal Budget on three occasions for compliance activities in relation to the cash economy. This additional funding totalled some $144.8 million, and the ATO reported that the Budget funding was to be used to raise an additional $631.2 million in revenue. Only the measure for 2010–11 was devoted entirely to the cash economy risk. Table 2.5 summarises the status of those elements within each Budget measure that were devoted to cash economy activities.

Table 2.5: Additional Budget funding for the cash economy risk

|

Year |

Budget measure |

ATO revenue commitment |

Cash economy funding |

Status and ANAO assessment |

|

2009–10 |

Strategic compliance—promoting a level playing field for small business

|

|

$14.9 million over four years |

Completed:

|

|

2010–11 |

ATO compliance program—dealing with the cash economy |

$491.8 million |

$107.9 million over four years |

Completed:

|

|

2012–13 |

Tax compliance—maintaining the integrity of the tax and superannuation system

|

LPF: $60.3 million SF: $60.7 million |

LPF: $14.01 million over four years SF: $8 million over four years |

Still current:

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Budget papers and ATO documents.

2.23 The earlier two Budget measures have been completed and were managed as projects using standard ATO project management documentation. The outline and closure reports—for low profile, low impact projects—were mostly adequately completed for both projects.

2.24 The 2010–11 compliance measure had two components: direct and indirect revenue from liabilities. The ATO met the direct liabilities target and has closed the project.18 However, the ATO has not yet measured and reported on whether the indirect revenue commitments have also been met. A methodology is being developed for reporting the indirect commitments, which are described as consequential revenue from compliance activity, that is, a change in people’s behaviour after compliance action has been taken. The ATO intends to apply the methodology retrospectively to measure the indirect revenue outcome. Future ATO reporting on Budget commitments would be improved by more transparent and timely reporting during the period covered by the Budget funding.

Recommendation No.2

2.25 The ANAO recommends that the ATO reports on the achievement of indirect revenue targets associated with Federal Budget funding for ATO cash economy activities.

ATO response: Agreed.

3. Risk management and case selection

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the ATO’s risk management and case selection processes support an optimal selection of cases for compliance activity.

Conclusion

The cash economy is a major tax integrity threat for the ATO, with a high risk rating. The ATO has a clearly defined cash economy risk population. Within this population, the ATO has identified specific industries and potentially high risk taxpayers, but has not undertaken a robust estimation of the revenue at risk from the cash economy.

A comprehensive range of information sources, both internal and external to the ATO, support the identification of risks for the cash economy and various risk tools are used to identify and guide the selection of high risk cases for treatment. Case selection processes are evolving to better support an optimal selection of cases for compliance activity.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has noted the ATO’s commitment to publish an annual estimate of the revenue at risk for the cash economy (paragraph 3.7).

Has the ATO adequately defined and managed the cash economy risk?

The ATO has adequately defined and managed the cash economy risk by having in place a current and sufficiently detailed risk assessment, risk treatment plan and schedule for reviewing the cash economy risk, which collectively meet the corporate requirements for risk management. Additionally, a formal methodology is in place to prioritise and treat emerging issues for the cash economy.

While the risk population has been clearly identified, and the ATO has conducted some analysis, it does not have a robust estimate of the level of revenue at risk from the cash economy. The ATO should publish an annual estimate of the revenue at risk from the cash economy, which it has committed to doing in 2016.

3.1 The ATO’s first formal definition of the cash economy was in 1996. The cash economy risk is a major tax integrity threat for the ATO, with a high risk rating. The risk is described at an operational level as: the failure of cash economy businesses, including those outside the system, to report all of their income leading to lower levels of compliance with the taxation system. The ATO currently relies on multiple sources of information to define the cash economy risk, for example, information from: businesses and industry groups; tax practitioners and the community; involvement in international forums; and data matching activities.19

3.2 In 2015–16, a dedicated team is responsible for risk and strategy activities including: analysing the cash economy population; identifying emerging risks; and data analytics and case selection, which supported the delivery of compliance activities to address the cash economy. The team’s work is underpinned by the ATO’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework. Key risk documents—assessments, treatment plans and reviews—are stored in the Enterprise Risk Manager, which is an ATO-wide risk register. For the cash economy risk, the most recent version of the required documents stored in the Enterprise Risk Manager system, as at December 2015, were:

- Enterprise Risk Assessment, 2012;

- Risk Treatment Plan, 2014; and

- Risk Review (Quarterly), April 2015. An annual review, scheduled for 2015–16, was deferred by the ATO in order to incorporate findings from the ANAO’s audit of the cash economy risk.

The risk population and revenue at risk

3.3 For the ATO’s purposes, the cash economy risk population is approximately 1.6 million businesses (mostly micro and small businesses with an annual turnover up to $15 million) operating across 233 industries. The ATO has identified that 58 of those industries are at a higher risk of operating in the cash economy and, in 2012, accounted for 74 per cent of the risk population. Given the growth of the hidden economy, such as electronic payments through merchant facilities, specialised payment systems and e-commerce portals, as other channels to conceal income, the ATO acknowledged in 2013–14 that a review of the historical cash economy base population would be timely and could impact on its compliance activity. No change has yet been made by the ATO.

3.4 While the ATO has undertaken some work in this area, it does not have a robust estimate of the taxation revenue foregone from the cash economy population. The longstanding rationale is that the revenue at risk from the operation of the cash economy is a component of the entire tax gap. Difficulty in defining the overall tax gap, and the lack of a universally accepted methodology for measuring the tax gap, has resulted in the ATO not providing an accurate assessment of the amount of revenue foregone.20 The ATO does however consider that the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest estimate (2013) of the non-observed economy—1.5 per cent of gross domestic product—sets an outer limit for the potential size of the cash economy.

3.5 Similar to Australia, the Canada Revenue Agency uses underground economy trend estimates produced by Statistics Canada, in relation to gross domestic product, to increase its knowledge of the underground economy, but does not publish a tax gap estimate. In the United Kingdom, HM Revenue and Customs publishes tax gap analyses, including estimates of the value of the hidden economy, and tax evasion, as tax gap behaviours.21

3.6 As mentioned previously, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ estimate of the non-observed economy remained stable, at approximately 1.5 per cent, for the ten years from 2000–01 to 2010–11. However, without a reliable estimate of the revenue at risk for the cash economy, the impact of the ATO’s activities cannot be determined.

3.7 The publication of a robust estimate of the revenue at risk from the cash economy in Australia would contribute to increased transparency by the ATO—and enable the estimate to become a performance indicator for the ATO’s management of the cash economy risk over time. In this regard, the ATO advised it will include an estimate of the revenue at risk for the cash economy as part of its forward work program to produce a range of tax gap estimates. The ANAO also noted that, in 2015, the ATO advised the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue that it would produce tax gap estimates in 2016 of small and medium business income tax, which will address the estimated revenue at risk for the cash economy.22

Strategies and activities for treating the risk

3.8 A 2014 risk treatment plan describes the ATO’s approach to treating the cash economy risk and directly links to the 2012 risk assessment. Table 3.1 summarises key elements of the treatment plan. Among the stakeholders (risk participants) identified by the ATO are businesses and consumers, media, employees, tax practitioners, industry associations and the ATO. There are also four intended outcomes listed in the treatment plan that are consistent with the COMPASS framework.

Table 3.1: Key elements of the cash economy risk treatment plan, 2014

|

Risk drivers for non-compliant businesses |

Treatment strategy |

Treatment method |

|

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of the ATO Risk Treatment Plan–Omitted Income 2013–14 for the cash economy.

3.9 Since 2013–14, a formal methodology has been used to prioritise and treat emerging issues for the cash economy. In 2014–15 and 2015–16, a total of 24 separate issues were identified and considered for treatment as a pilot activity. Cash economy work: has been completed in relation to Bitcoin and pop-up shops (2014); is in progress for collaborative consumption23 and unmatched eBay data (2015); and is planned for sales suppression.24 Reports have been prepared for completed pilots that have contained recommendations for no further action, identified potential areas for improvement with existing compliance activities or recommended further research is undertaken.

Does the ATO have effective processes for selecting cases for cash economy compliance activity?

The ATO has established effective processes for selecting cases for compliance activity, based on an assessment of risk. Multiple sources of information support the operation of two key risk tools for case selection: small business benchmarks and the Unrealistic Business Income model. The ATO is strengthening its processes for selecting cases for cash economy compliance activity, and there is also scope to streamline the process for allocating cases to the compliance teams.

3.10 Target selection for the cash economy population is risk based, which means that the ATO uses a combination of risk models, information sources, lifestyle indicators and benchmarks to focus on the area of highest risk or of potentially greatest influence for compliance activity.

Sources of risk information

3.11 The cash economy risk and strategy team received a total of 21 683 referrals in the last two years (2013–14 and 2014–15) from a wide range of sources including: the ATO’s Tax Evasion Reporting Centre, which handles community referrals; other ATO business lines; ministerial correspondence; and government agencies, such as the Australian Federal Police. The referrals are stored in a central database, treated on a case-by-case basis, and the outcomes are recorded. Only high priority referrals are actioned, while medium and low priority referrals can be used to guide treatment strategies for specific industries.

3.12 The ATO undertakes data matching to identify potential cash economy cases using its own data, for example, income tax returns and business activity statements, and data sourced from third parties including merchant data (card transactions) and online retailing sites (such as eBay).

Risk assessment tools and reviews

3.13 An overview of the tools either in use or under development by the ATO to perform risk assessments specifically for the cash economy population is set out in Table 3.2. ATO enterprise-wide systems are also used to assess risks for the cash economy.

Table 3.2: Risk assessment tools for the cash economy

|

Tool |

Description |

Status |

|

Small Business Benchmarks |

|

Business-as-usual |

|

Unrealistic Business Income model |

|

Business-as-usual |

|

Risk Differentiation Framework |

|

Under development |

|

Cash Economy Analytical Model |

|

Under development |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents and advice during audit fieldwork.

3.14 The ATO is currently moving towards using the Risk Differentiation Framework as the primary case selection tool for the cash economy. In the interim, the ATO will continue to use a combination of risk factors derived from the small business benchmarks and Unrealistic Business Income model. However, the future direction could change in the context of the evolution of the Smarter Data program25 and movement of the cash economy workforce to the new Small Business line (as outlined in Chapter 2), where other risk models are in use.

3.15 In 2015, the ATO initiated a number of reviews to confirm the various risk tools were operating as expected and to identify improvements for future case selection and compliance activity, as follows:

- reviews of up to 700 closed cases were assessed to identify areas for improvement when selecting cases using the Unrealistic Business Income model and other potential risks, such as the small business benchmarks; and

- additional targeted case refinement work on 300 businesses was being undertaken to test the business rules in the Unrealistic Business Income model and support future case work.

3.16 Even though information on the small business benchmarks is maintained on the ATO’s website, information on the Unrealistic Business Income model is not published and the model’s business rules have not been subject to an annual review. The review of closed cases was finalised in 2015, and work on the outcomes is ongoing with the Smarter Data business line. However, the ATO advised in January 2016 that the case refinement work on 300 businesses was expected to be completed by the end of June 2016, with a view to also working with the Smarter Data business line to implement any suggestions for improvements.

Case selection and allocation processes

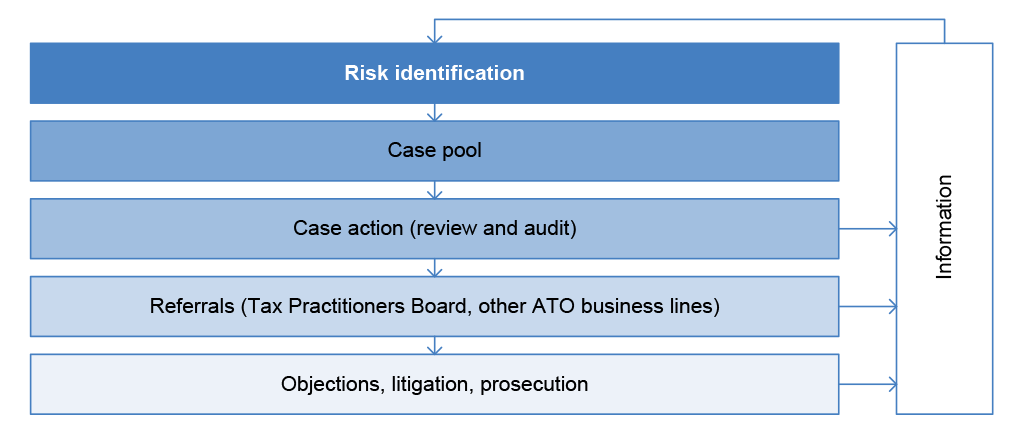

3.17 Figure 3.1 provides an overview of the case selection process and outcomes from cash economy compliance activities, including referrals to other ATO business lines and the continuous feedback of information to support risk identification activities.

Figure 3.1: Case selection and outcomes from cash economy compliance activities

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO diagrams.

3.18 While the potential case pool that can be generated for cash economy compliance activity is much larger, a high risk population of 200 000 potential candidates is maintained and refreshed. Based on a set of selection parameters, cases—either from the top 200 000 or the full population of cash economy businesses that have not lodged a business activity statement and are at risk—are matched to a particular treatment strategy (for example, a review or audit). The different treatment strategies used for the cash economy are discussed in Chapter 4.

3.19 The ATO’s risk and strategy team maintain a Demand Manager program and cases are loaded for allocation to ATO sites following an email request from a staff member to a central point of contact. The ATO has recognised that increased automation of that process would enable teams in different sites to better manage their case workload by directly selecting and requesting cases in a more timely way.

4. Conducting compliance activities

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the ATO’s compliance activities conducted for the cash economy were effectively treating the risk.

Conclusion

The ATO’s approach to treating the cash economy risk currently involves the ATO undertaking a wide range and large number of compliance activities. These activities are risk based and focus on treating industries identified by the ATO as high risk. From 2011–12 to 2014–15, the ATO completed over 70 000 compliance cases for the cash economy and raised around $780 million in liabilities from taxation revenue and penalties, of which around $456 million in cash was collected. In achieving these results, the ATO met its own liability targets for cash economy activities in three of the four previous years, and completed most compliance cases in a timely way. While there are indications of increasingly effective case selection, the ANAO identified further opportunities for the ATO to prioritise its cash economy compliance activities.

The ATO does not have measures of the outcomes of cash economy compliance activities. To enable a sound assessment of the extent to which compliance activities conducted for the cash economy are effectively treating the risk, the ATO should put in place measures of effectiveness as part of the Community Participation Assurance Framework (COMPASS).

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two suggestions, relating to: reviewing revenue targets in order to continually improve organisational efficiency and performance (paragraph 4.7); and refining case selection approaches (paragraphs 4.11–4.13).

Does the ATO conduct an appropriate range of compliance activities to address the cash economy?

The range of compliance activities undertaken by the ATO to address the cash economy—audit, obligation enforcement and review—is consistent with the practices of revenue bodies internationally and reflects a number of core elements identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as present in comprehensive strategies to address the underground economy. The compliance activities are based on determining and responding to the risk of businesses, industries and the community participating in the cash economy.

4.1 The ATO’s approach to treating the cash economy risk has evolved over time with a number of key milestones having influenced the current approach to conducting compliance activities. For example, in the 2009 Federal Budget, the ATO received funding to develop small business benchmarks and conduct related compliance activities.

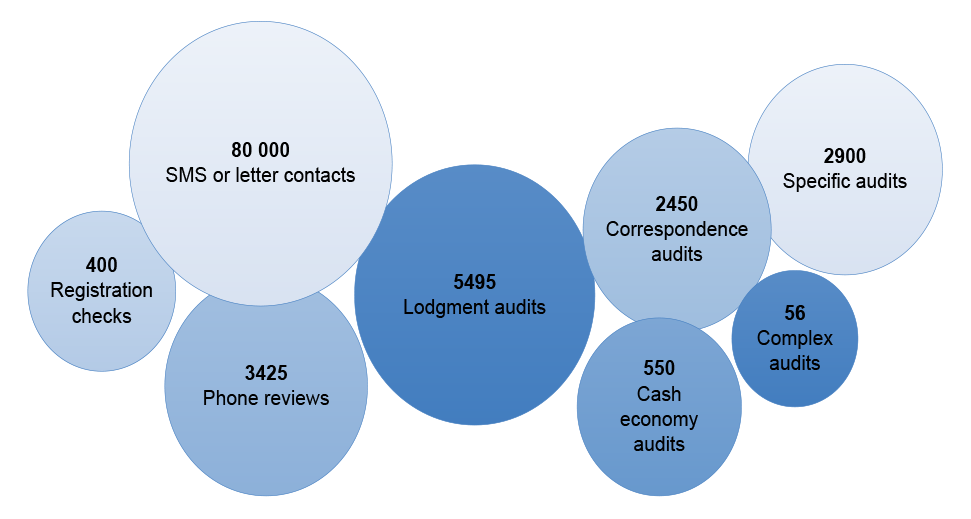

4.2 Figure 4.1 shows the range of compliance activities planned to address the cash economy risk in 2015–16.

Figure 4.1: Cash economy planned compliance activities for 2015–16

Source: ATO advice.

4.3 As described in Chapter 2, the compliance activities for the cash economy reflect the ATO’s risk based approach for the cash economy from low risk (minimal touch: SMS or letters) to high risk (high touch: complex audits). The compliance activities can be grouped into the following broad categories:

- help and education—sending correspondence to taxpayers and their tax practitioners to create awareness and provide information and, to a lesser extent, seek a response (which is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5);

- obligation enforcement—using a high volume of outbound telephone calls to taxpayers and their tax practitioners to support lodgment and correct reporting; and

- reviews and audits—while both are considered ‘tax audits’ by the ATO, they vary in their complexity. Reviews can be conducted without contacting taxpayers or by telephone and also allow the ATO to determine whether there are issues that require deeper investigation by an audit.

4.4 The ATO’s compliance activities for the cash economy are consistent with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s report (2012) on the underground economy and international practice by other revenue bodies. The report identified eight core elements that were common in existing strategies that address the underground economy (see Chapter 1). The ATO’s activities cover the four core elements specifically relating to compliance: the wide use of media; leveraging off key intermediaries such as tax practitioners and industry representatives; having a broad set of treatment strategies; and evaluating the effectiveness of compliance.

Are the ATO’s compliance activities effectively addressing the cash economy?

The ATO’s cash economy compliance activities are typically meeting internal performance targets, such as for liabilities raised and the timeliness of case completion. However, as no measures of effectiveness are in place, it is difficult for the ATO to assess the extent to which its compliance activities contribute to, and align with, the outcomes of the cash economy strategic framework. Developing measures of effectiveness as part of the Community Participation Assurance Framework would assist the ATO to determine the nature and extent of its future compliance activities to address the cash economy.

Cash economy compliance cases had only around half the return on investment of the average compliance cases the ATO conducted in 2015. While there are indications of increasingly effective case selection, the ANAO identified further opportunities for the ATO to improve the selection of cash economy compliance cases. By adjusting case selection parameters the ATO could take into account the: potential average liability that could be raised; distribution of cases across industries; size of the industry’s high risk population; and impost on lower risk industries of high case numbers.

Even though over 80 per cent of compliance cases with taxpayers were completed within the allocated time for the ATO to conduct the case, the more complex audit and review cases that produce higher liabilities were more likely to be overdue. This means the ATO could improve the timeliness of its more complex cash economy review and audit cases.

Compliance activities aimed at raising liabilities

4.5 The ANAO examined the results of cash economy compliance cases that were closed in the previous four years (2011–12 to 2014–15) and were aimed at raising liabilities (defined as total tax and penalties26). Figure 4.2 provides an overview of the total cases and liabilities analysed by the ANAO. The total number of closed cases over the four years that were analysed by the ANAO was 73 640 and the liabilities raised totalled $776.3 million. The ANAO’s following analysis is based on these figures.

Figure 4.2: Total cash economy cases and liabilities raised, 2011–12 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

4.6 Figure 4.2 highlights a trend towards fewer cases being required to raise an increasing amount of liabilities. The results indicate that the ATO has become more efficient in its compliance activities for the cash economy27, which is discussed in more detail later in this chapter (in relation to the return on investment).

4.7 The liability targets for cash economy activities have also been met in three of the four previous years (Chapter 1). The ATO should continue to review the targets in order to improve its efficiency and performance.

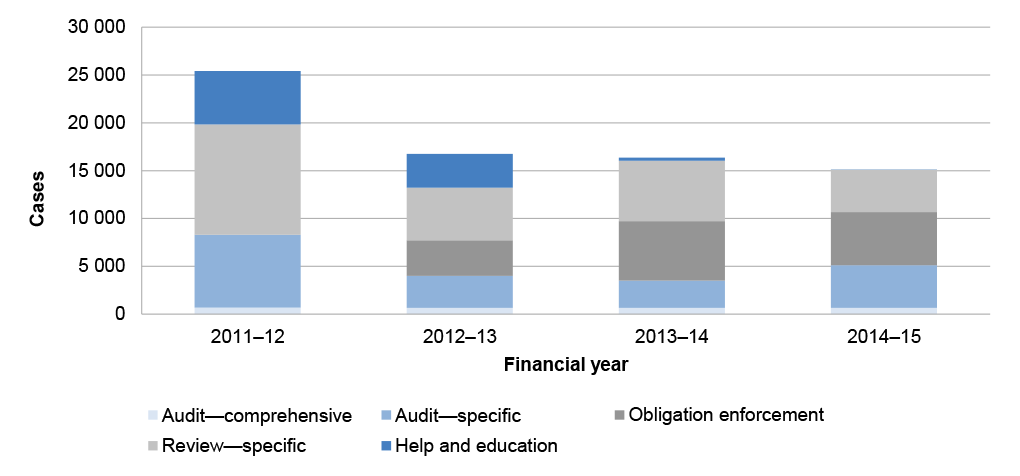

Types of compliance activity

4.8 Figure 4.3 provides an overview of the types of cash economy cases conducted each year for audit, obligation enforcement, review, and tailored advice (help and education). Tailored advice includes visits to tax practitioners on the basis that one tax practitioner can reach many clients and increase the ATO’s visibility.

Figure 4.3: Types of cash economy compliance activity, 2011–12 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

4.9 Figure 4.3 shows that the number of help and education cases decreased significantly from over 5500 (in 2011–12) to five (in 2014–15). These help and education activities were one-on-one record keeping assistance visits where ATO staff would visit a business to provide advice on record keeping. Over the period, the ATO advised that it migrated towards a greater level of one-to-many assistance approaches through communications products, self-help tools—such as the ability for businesses to calculate their own benchmarks—and industry partnership assistance. There was also a corresponding increase in the ATO’s use of obligation enforcement cases for awareness raising and educative purposes.

Case selection

4.10 Figure 4.2, showing total cash economy cases and liabilities raised, also suggests that the ATO’s case selection activities have become more effective over time and that the strategy of using a combination of sources to identify risk indicators—risk models, benchmarks, referrals and third-party data—is appropriate.

4.11 As discussed in previous chapters, the ATO has identified 58 industries that are at a higher risk of operating in the cash economy and omitting income. On average (from 2011–12 to 2014–15), the ATO selected 63.4 per cent of its compliance cases from the top 58 industries and 36.6 per cent of compliance cases from outside the top 58 industries. The ATO could potentially have raised additional liabilities over the four years by conducting a greater share of cases in other industries, given that the average liability raised was greater for cases outside the top 58 industries.28

4.12 The ATO could also consider, as an input to case selection, the potential average liability to be raised when selecting cases, both within and outside the top 58 industries (as well as the marginal impacts for industry based strategies). The ATO advised that there would be a benefit in conducting its own marginal impact analysis of a different approach.

4.13 The size of an industry’s high risk population and the impost on lower risk industries of a high percentage of cases being undertaken (relative to their top 58 industry ranking) are additional factors that could be considered by the ATO when determining case selection.

Overview of financial outcomes

4.14 Table 4.1 provides an overview of the compliance cases with a liability raised by the ATO for the cash economy from 2011–12 to 2014–15. Of the 73 640 cases finalised, which includes review and help and education cases where there was no expected revenue outcome, a liability was raised in 17 944 cases.29

Table 4.1: Cash economy cases with a liability raised, 2011–12 to 2014–15

|

Year |

Number of cases with a liability |

Percentage of total cases |

|

2011–12 |

3 839 |

15.1 |

|

2012–13 |

4 212 |

25.1 |

|

2013–14 |

5 060 |

30.9 |

|

2014–15 |

4 833 |

32.0 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

4.15 The proportion of cases where the ATO raised a liability has more than doubled in the last four years (from 15 per cent to 32 per cent). While this reflects the change in case type over the period (as discussed in paragraph 4.9), an important factor is also likely to be improvements to case selection—between 2011–12 and 2012–13, the proportion of audit and enforcement cases resulting in a liability increased from 25 per cent to 50 per cent.

4.16 The amount of liability raised over the four-year period is directly related to the type of compliance case that was undertaken:

- audit and obligation enforcement cases raised $695.5 million (from 36 413 cases, 49.4 per cent of the total cases finalised);

- review cases raised $80.7 million (from 27 779 cases, 37.7 per cent of the total cases finalised); and

- tailored advice cases raised approximately $70 900 (from 9448 cases, 12.8 per cent of the total cases finalised).

Return on investment

4.17 The ATO’s return on investment for cash economy activities is lower than the total for the Client Engagement Group and some individual risks, for example, high wealth individuals:

- former Compliance Group (now the Client Engagement Group), October 2015 (year to date), $6.0430; and

- high wealth individuals, 2012–13, $27.26.31

4.18 The ATO advised that the return on investment for the cash economy activity was $3.20 in 2014–15, which has increased over time from $2.00 in 2011–12. The ATO further advised that there are two main reasons for the lower return on investment:

- compliance activity for the cash economy is relatively labour intensive because compliance staff often need to undertake investigations to determine that income has not been declared, rather than, for example, requiring taxpayers to confirm claims for deductions or validate specific declarations of income from known sources; and

- linked to the above, there is a correspondingly lower level of automation possible for compliance activities, which means the work is more time consuming.

4.19 Similar liabilities were raised by the ATO for the cash economy risk in 2014 as in 2005 (some $200 million), but with a 36 per cent lower (full-time equivalent) staffing level: 381 compliance staff in 2014; compared to 600 compliance staff in 2005. The ATO considers that an increase in liabilities from 2010 to 2014, compared to the investment of staff, is indicative that the more recent strategy for the cash economy risk and case mix is delivering better results.

Measures of effectiveness of compliance activities

4.20 As discussed previously (paragraph 2.5), the current version of COMPASS does not include details of how its high-level measures of success are to be measured. These measures could provide useful information about the extent to which the ATO’s compliance activities contribute to, and align with, the desired outcomes of the cash economy strategic framework—engagement with the community, authority to act and outcomes for the community. As indicated in Recommendation No.1 (paragraph 2.6), the ATO should develop measures of success (effectiveness) as part of COMPASS, which would assist it to determine the nature and extent of its future compliance activities to address the cash economy.

Timeliness

4.21 In the four years of ATO case data, there were 29 types of compliance activity undertaken with a minimum cycle time of nine days (obligation enforcement) and a maximum cycle time of 250 days (complex audit).32

4.22 Following ATO advice, the ANAO analysed the 29 types of case activities based on the ATO’s grouping of five case sub-types: audit (comprehensive and specific); obligation enforcement; review; and help and education. Figure 4.4 provides a comparative view of the ATO’s performance for the cycle times contained within the five case sub-types.

Figure 4.4: Case sub-type and cycle time performance, 2011–12 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

4.23 Overall, 80.5 per cent (59 263 cases) were completed within the allocated cycle time, regardless of the type. Of the overdue cases, audit specific (25 per cent) and audit comprehensive (46 per cent) cases were more likely to be overdue and almost 20 per cent of review specific cases were overdue. The more complex audit and review cases that produce higher liabilities were also more likely to be overdue in their cycle time, which is not uncommon for these types of ATO compliance activities.33 However, taxpayers and the ATO would directly benefit from the ATO improving the cycle times for complex audits for the cash economy (and other elements of the tax system).

5. Help and education

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the effectiveness of the ATO’s communication activities to promote compliance with the tax system by addressing the cash economy, including through stakeholder and community engagement. The ATO refers to these activities as help and education.

Conclusion

The ATO’s help and education activities for the cash economy risk are planned, evidence based and targeted at key risks, and provide a wide range of general and targeted information to promote taxpayer compliance. However, the ATO has not evaluated the overall effectiveness of its help and education activities to address the cash economy risk.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has suggested that the ATO measures the value for money of its cash economy help and education activities (paragraph 5.19).

Is there a communications strategy aligned to the cash economy strategic framework that is evidence based?

The ATO’s cash and hidden economy communications framework sets out the business intent, objectives and key messages for help and education activities that address the cash economy risk. The framework is evidence based and complemented by strategic activities that target specific groups and emerging cash economy risks identified through the ATO’s risk based work.

5.1 Following the movement of the cash economy activity to the new Small Business line in November 2015, a draft communications framework for the cash and hidden economy risk was updated and finalised to realign the framework to the new business line. The framework seeks to: reduce tolerance of and participation in the cash economy by individuals and businesses; build community confidence in the ATO’s management of the cash economy risk; and increase the proportion of tax paid voluntarily by the population targeted by ATO activities. The framework supports the cash economy strategic framework (COMPASS), and is complemented by activities that target specific groups and emerging risks identified by the ATO’s risk based work. Table 5.1 shows the framework’s three areas for key messages.

Table 5.1: Communications framework areas for key messages about the cash economy

|

Key messages |

|

Source: Summarised from the ATO’s cash and hidden economy communications framework.

5.2 The ATO’s help and education activities are evidence based. The cash and hidden economy communications framework is informed by market research, developments and research undertaken in other jurisdictions, analysis of compliance outcomes and stakeholder feedback.

Does the ATO provide a range of information about the cash economy to promote taxpayer compliance?

The ATO website provides a wide range of general and targeted information about the cash economy risk, including information on the small business benchmarks. Targeted information is consistent with the ATO’s omitted income risk assessment and risk treatment plan.

Cash economy help and education activities

5.3 The ATO provides a wide range of general and targeted information to promote taxpayer compliance. The ATO website is a key communication channel with dedicated cash economy web pages. Most general information can be readily accessed from the principal cash economy web page, About the cash and hidden economy34, including information on the small business benchmarks and online tools.35 The ATO also has dedicated web pages for targeted communications.

5.4 The cash and hidden economy communications framework identifies key audiences including: existing and new small businesses; the Australian community; and key intermediaries (tax practitioners, industry associations and community partners). Since 2014, the ATO has increased its audience reach with a suite of communication channels that target small businesses (such as the small business newsroom and mobile phone app). The ANAO expects that the ATO will increasingly use these dedicated channels for communicating with small businesses, and for messages about the cash economy following the transfer of responsibility for the cash economy risk to the Small Business line.

Targeted communications

5.5 Targeted communications—at industry or other groups that exhibit cash economy risk behaviours or emerging issues, such as those discussed in Chapter 3—support the cash and hidden economy communications framework. Targeted groups have high rates of businesses: operating outside of industry benchmarks; under-reporting transactions and income; with poor lodgment history; and reported by members of the community for tax evasion.

5.6 Currently, the ATO has four multi-year targeted strategies (Table 5.2):

- three industry based strategies, for the building and construction; cafe, restaurant and takeaway; and hair and beauty industries; and

- a strategy for small business owners from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Table 5.2: Communications targeted at industry and other groups and localities, 2011–12 to 2014–15

|

Target communication strategies |

Timeframe |

|

|

Current strategies |

Commenced |

Duration |

|

Building and construction industry |

2013–14 |

3 to 4 years |

|

Cafe, restaurant and takeaway industry—cash only businesses |

2013–14 |

3 years |

|

Diverse audiences (taxpayers from non-English speaking backgrounds) |

2013–14 |

Ongoing |

|

Hair and beauty industry |

2013–14 |

3 to 4 years |

|

Completed strategies |

Commenced |

Duration |

|

Coffee shops |

2011–12 |

2 years |

|

Plasterers |

2011–12 |

2 years |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

5.7 All industries selected to date have been drawn from the top 10 industries that exhibit cash economy risk behaviours. The strategy for taxpayers from non-English speaking backgrounds targets four communities: the Arabic, Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese communities. The strategy has a particular focus on Chinese and Vietnamese communities given their strong representation in the hair and beauty industry. While the industry strategies consist of help and education and compliance activities, the diverse audience strategy consists only of help and education activities. The targeted communication strategies are consistent with the ATO’s risk assessment and risk treatment plan (discussed in Chapter 2).

Business to consumer transactions

5.8 The ATO first identified business to consumer transactions as a future challenge in the mid–2000s. ANAO Report No. 30 2005–06, The ATO’s Strategies to Address the Cash Economy, recommended that the ATO develop and implement a community education campaign on such transactions.

5.9 Between 2012–13 and 2014–15, the ATO’s communications framework documents increasingly identified business to consumer transactions as an area of ongoing focus. Recent treatments that specifically addressed this behaviour include the building and construction industry strategy.

Stakeholder and community engagement

5.10 Leveraging off key intermediaries is one of eight core elements of successful strategies for addressing the underground economy identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.36

5.11 Successive ATO communications framework documents have identified as an important activity leveraging off key ‘influencers’; in this context, tax practitioners, industry associations, community leaders and media. Tax practitioners are particularly influential, given that, in 2013–14 tax practitioners lodged 93 per cent of micro business37 returns and 46 per cent of business activity statement returns.

5.12 Strategic community engagement with key influencers is a feature of all three current industry based strategies, as set out in Case study 1.

|

Case study 1. Haymarket walk-ins |

|

In July and August 2014, ATO staff visited around 160 cafes and restaurants in Sydney’s Haymarket area to provide owners with information on their tax and superannuation obligations and identify potential businesses for audit. The ATO also held two town hall style information sessions to answer questions from business owners. The ATO worked closely with local councils and community and business groups beforehand. ATO staff found issues relating to Australian Business Numbers, tax file numbers, and outstanding lodgments of business activity statements and income tax returns. The ATO worked with businesses to correct mistakes and help ensure up-to-date lodgments. The ATO continued to monitor cafes and restaurants in the Haymarket area for cash economy behaviours for the next 12 months. Overall, the ATO met the project’s effectiveness measures, including building confidence, increased community awareness, and identifying and addressing non-compliance. As at October 2015, 23 cases resulted in revenue adjustments of more than $800 000. The ATO has since conducted similar exercises in other geographic regions for high risk industries with more planned for 2015–16. |

Has the ATO evaluated the effectiveness of its cash economy help and education activities in building community confidence?

The ATO measures the audience reach of individual communication products, but has not comprehensively evaluated the effectiveness of its cash economy help and education activities against the evaluation measures in annual communications frameworks. Consequently, it has not measured the value for money from these activities. To measure behavioural change, the ATO conducts community and business surveys and, in 2015, developed evaluation measures for three targeted industry strategies. While not having completed this work, the ATO advised that initial results were promising.

5.13 The cash and hidden economy communications framework states that: the ATO is developing a communication measurement framework; and, in the interim, the ATO will measure the impact of marketing and communication activities for the cash economy using the three measures38 and associated indicators set out in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3: Cash and hidden economy communications framework evaluation measures and indicators

|

Measure |

Indicators |

|

Comparing outputs against planned activities |

|

|

Communication metrics |

|

|

Ongoing analysis of community conversations |

|

Source: ATO cash and hidden economy communications framework.

5.14 While not measures of effectiveness as such (as acknowledged by annual communication frameworks), these measures can contribute to an overall picture of the effectiveness of the communications strategy for the cash economy. However, the ATO has not comprehensively evaluated the overall effectiveness of all cash economy help and education activities against these or similar measures contained in annual communications frameworks.

Measuring changes in community and business attitudes

5.15 The ATO uses quantitative and qualitative measures to monitor changes in community and business attitudes towards the cash economy. It uses a range of metrics to measure audience reach (visits to specific ATO website pages, messages by third parties in response to ATO activities, and social media activity) of individual communication products (videos, media releases, pilot issues) that seek to generate awareness and encourage community debate.

5.16 Between 2010 and 2013,39 the ATO measured changes in attitudes via its community and business perception surveys. These surveys found that community and business attitudes towards the cash economy remained constant, with individual taxpayers and micro businesses strongly opposed to a cash economy. The proportion of respondents that agreed the ATO is effective in combating the cash economy also remained constant (at approximately 57 per cent).40 However, another ATO survey41 found that attitudes towards the cash economy have fluctuated over time and that for a minority of businesses and individuals, not declaring cash transactions was expected (trade workers, retailers and restaurant owners for example) or considered necessary to survive in an increasingly competitive environment.