Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Sport Integrity Australia (SIA) was established on 1 July 2020 by the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020.

- SIA is the national anti-doping organisation for Australia under the United Nations Anti-Doping Convention and the World Anti-Doping Code. It has responsibility for managing a National Anti-Doping Scheme.

- The government has noted the importance of effective anti-doping measures to protect the integrity of Australian sport.

Key facts

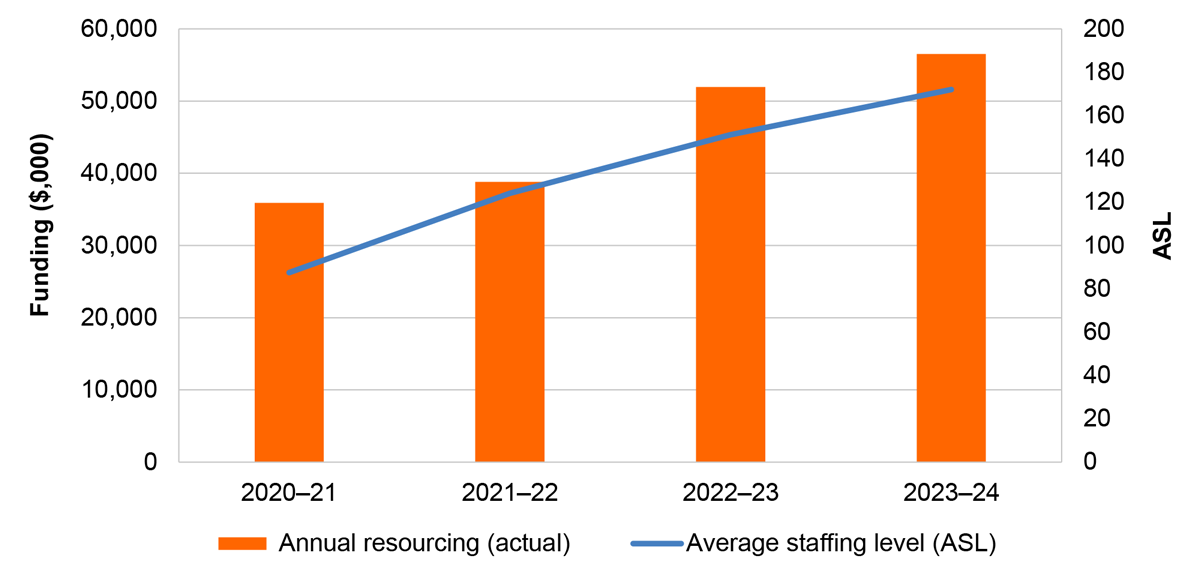

- In 2023–24, SIA’s total resourcing was $56.5 million, with an average staffing level of 172.

- 98 sporting organisations in Australia have adopted the National Anti-Doping Policy.

- As the national anti-doping organisation for Australia, SIA has primary authority and responsibility at the national level to collect and test samples from athletes for the purpose of detecting anti-doping rule violations.

What did we find?

- SIA’s management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme is partly effective.

- Governance arrangements for anti-doping are partly fit for purpose.

- Anti-doping prevention and detection is largely effective for sports that have government funded testing arrangements, and partly effective for sports that have ‘user pays’ arrangements.

- SIA’s arrangements to investigate and respond to anti-doping rule violations are partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were seven recommendations relating to: performance measures; regulatory capture risks; procedures for test distribution planning; evaluation methodology; risk-based planning; investigative procedures; and quality assurance over investigations.

- Sport Integrity Australia agreed to all seven recommendations.

15,131

Anti-dopingsamples collected between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024

38

Anti-doping rule violation investigations commenced between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024

15

Number of sanctions issued to athletes (from 21 investigations commenced and closed between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024)

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. On 5 August 2017, the Minister for Health and Aged Care announced a review of Australia’s sport integrity arrangements. The Report of the Review of Australia’s Sport Integrity Arrangements (the Wood Review) was presented to the government in March 2018 and made 52 recommendations, including the establishment of a national sports integrity commission.1 In its February 2019 response to the Wood Review2, the Australian Government agreed, agreed in part, agreed in principle or noted all recommendations. Sport Integrity Australia (SIA) was established on 1 July 2020 by the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020 (SIA Act).

2. The object of the SIA Act is to establish SIA to prevent and address threats to sports integrity and to coordinate a national approach to matters relating to sports integrity in Australia. A National Anti-Doping Scheme is required under section 3 of the SIA Act and is set out in Schedule 1 of the Sport Integrity Australia Regulations 2020 (SIA Regulations). The SIA Regulations outline the powers and functions of the SIA Chief Executive Officer, which include having the role and responsibility of a ‘national anti-doping organisation’ for Australia under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Anti-Doping Convention and the World Anti-Doping Code.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. In its response to the Wood Review, the Australian Government committed to ‘comprehensively protecting the integrity of Australian sport for the benefit of the entire Australian community’ and to establishing a national sports integrity commission (SIA). The government also noted the importance of effective anti-doping measures to protect the integrity of Australian sport.

4. The audit provides assurance to the Parliament as to whether SIA has established effective governance arrangements for anti-doping and is effectively managing the National Anti-Doping Scheme.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The purpose of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Sport Integrity Australia’s management of the National Anti-doping Scheme.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements?

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established effective arrangements to prevent and detect anti-doping rule violations?

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established effective arrangements to investigate and respond to possible anti-doping rule violations?

7. The period covered by the audit is 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2024. Anti-doping matters prior to the establishment of Sport Integrity Australia on 1 July 2020 are not within the scope of this audit.

Conclusion

8. Sport Integrity Australia’s management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme is partly effective. SIA has adopted a different approach to anti-doping regulation, depending on how anti-doping samples and testing are paid for. Regulatory responsibilities are more effectively carried out for sports that receive government funded anti-doping testing. For sports where testing costs are partially recovered from the sport, regulation is not demonstrably risk-based and data driven — a key principle of good regulation. There are deficiencies in anti-doping investigation practices.

9. SIA’s governance arrangements for the National Anti-Doping Scheme are partly fit for purpose. There are largely fit-for-purpose oversight and assurance arrangements. Risk management, including for regulatory capture risks, is not fit for purpose.

10. SIA’s arrangements for preventing and detecting doping are largely effective for sports that have mainly government funded anti-doping sample collection arrangements, and partly effective for the major professional sports that have mainly ‘user pays’ anti-doping sample collection arrangements, due to the way SIA has chosen to administer ‘user pays’ arrangements.

- There is a fit-for-purpose national anti-doping framework, which is supported by a national anti-doping policy that is adopted by 87 national sporting organisations. Another three national sporting organisations have an SIA-approved anti-doping policy.

- SIA has effective arrangements to prevent anti-doping rule violations through anti-doping education plans that are implemented and evaluated.

- For sports that have mainly government funded testing arrangements, test distribution planning is generally risk-based. Transparency could be enhanced through more comprehensive documentation of planning methodology and record keeping.

- For the six major sports that have mainly user pays testing arrangements, test distribution planning is not demonstrably risk-based. The number and distribution of tests are negotiated with national sporting organisations under a service agreement. This is not consistent with World Anti-Doping Code principles or SIA’s responsibilities as a regulator of these sports.

11. SIA’s arrangements to investigate and respond to anti-doping rule violations are partly effective. The procedural framework for investigations is partly fit for purpose, including processes related to quality assurance. There were irregularities in the triage and conduct of 38 investigations commenced in the three years to 30 June 2024, when compared to existing procedures. Investigations did not consistently meet timeliness targets. SIA’s actions in response to proven anti-doping violations were appropriate.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

12. SIA has responded to the Minister for Sport’s statement of expectations with an appropriate statement of intent. There are management arrangements and governance bodies that give consideration to anti-doping matters. These include advisory bodies that have been established in accordance with the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020. Governance bodies operate in accordance with legislative requirements or terms of reference, except for the declaration of interests on two key advisory bodies. SIA’s public performance reporting includes measures related to anti-doping. There is no performance reporting specifically related to anti-doping testing and investigations — a key regulatory function. There is no measure that goes to the effectiveness or efficiency of SIA’s anti-doping activities. Performance reporting on anti-doping in 2023–24 was not fully accurate. SIA reports integrity and anti-doping matters of significance to the Minister for Sport. (see paragraphs 2.2 to 2.20)

13. Sport Integrity Australia established a risk management policy in 2021, which was updated in 2023. Risk appetite statements provided in different documents are inconsistent. There is an enterprise risk register, which was last updated in November 2021. Operational risk registers for specific business areas or activities, including for anti-doping, are not maintained. SIA undertook a review of its risk management framework in 2024, which concluded that the risk management framework required ‘significant’ work to comply with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. SIA commenced a body of work to improve SIA’s risk management framework. There is a largely fit-for-purpose policy framework for regulatory capture risks, including risks arising from conflicts of interest; external employment; gifts, benefits and hospitality; and sports betting. The policies are poorly implemented. (see paragraphs 2.21 to 2.43)

Anti-doping prevention and detection

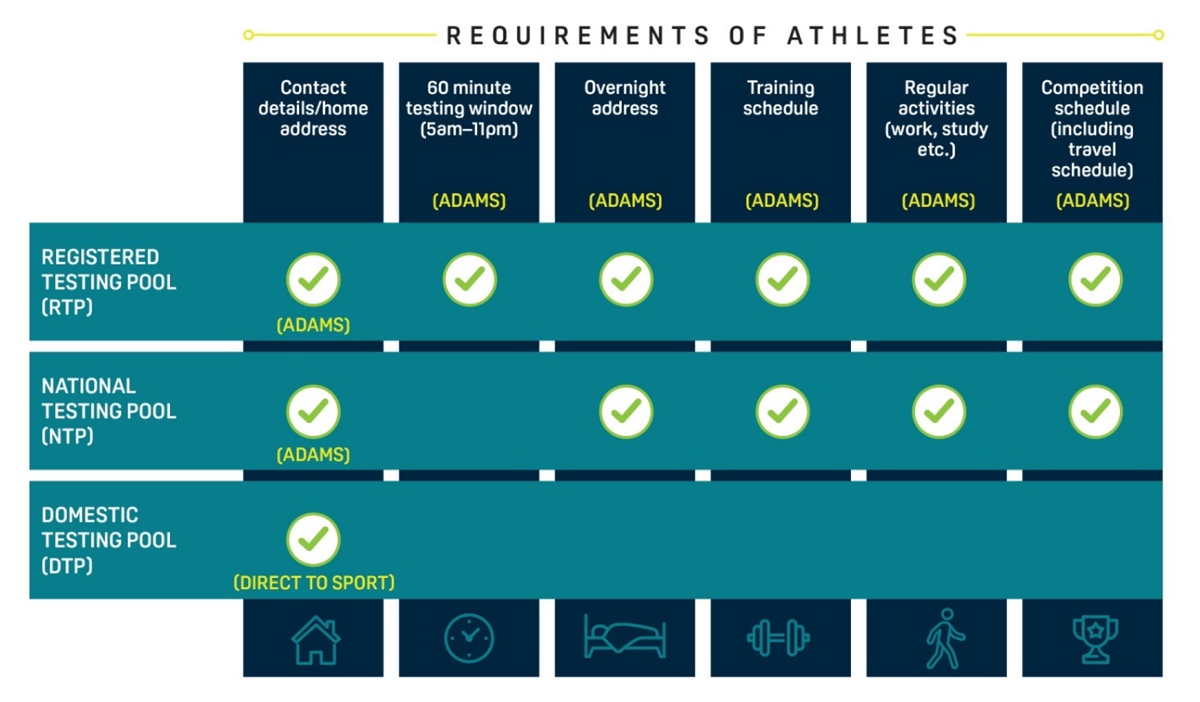

14. The Sport Integrity Australia Regulations 2020 establish the SIA CEO’s functions and powers in relation to anti-doping, which include sample collection and results management for ‘sporting administration bodies’, defined as ‘national sporting organisations for Australia’. SIA has established an Australian National Anti-Doping Policy (NAD Policy) that aligns with the World Anti-Doping Code and which, as of September 2024 had been adopted by 98 sporting organisations in Australia, including 87 national sporting organisations for Australia. Anti-doping policies for the remaining three national sporting organisations that have adopted alternative policies were not approved by SIA in a timely way using documented criteria.

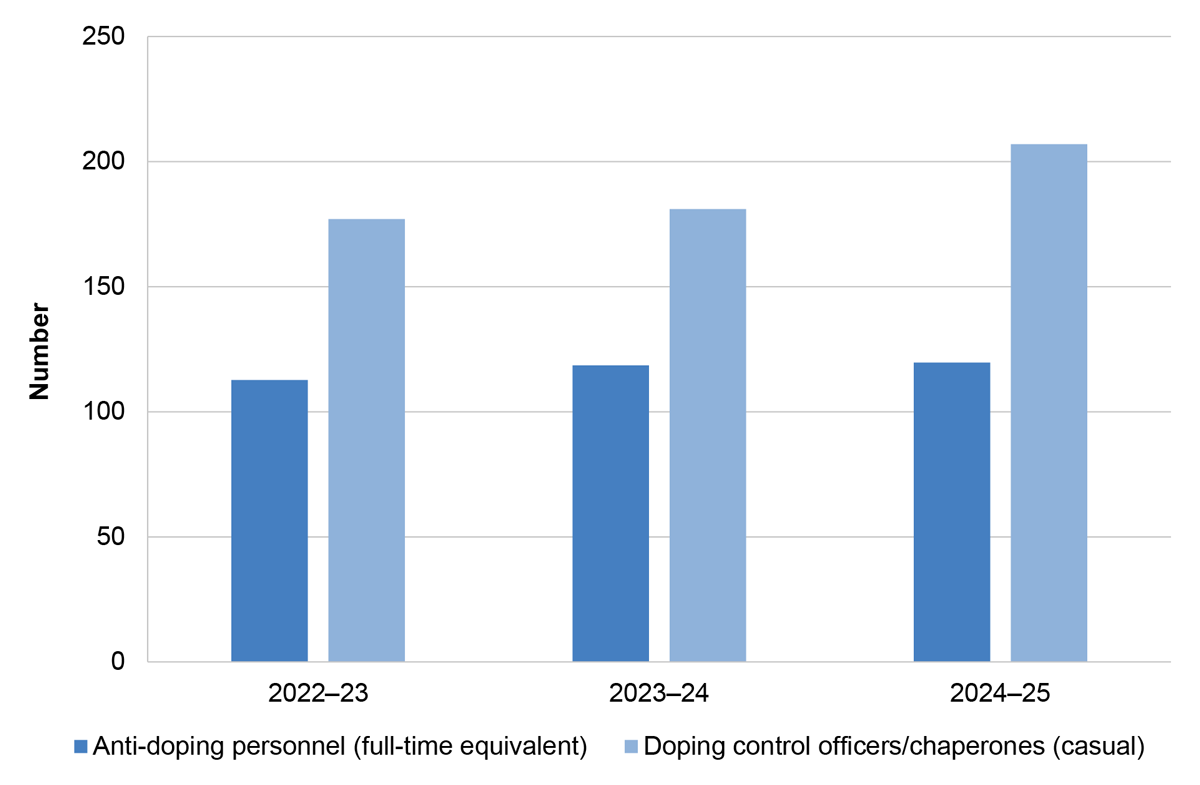

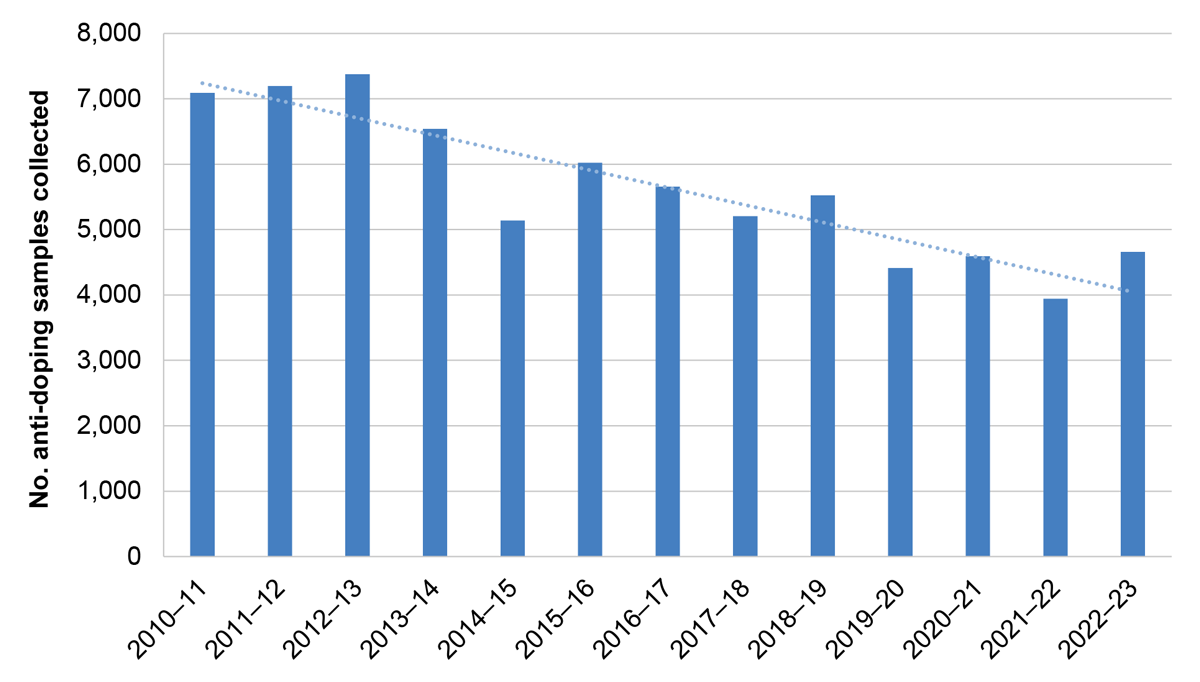

15. SIA’s annual anti-doping activities are supported by approximately 300 full-time equivalent (FTE) and casual employees. Budgeted average staffing levels increased by six per cent for FTE staff and 17 per cent for casual staff between 2022–23 and 2024–25. The total number of anti-doping samples collected by SIA declined by 34 per cent between 2010–11 and 2022–23.

16. SIA provides anti-doping sample collection and analysis under two general funding models: government-funded and user pays. User pays arrangements involve partial cost recovery, an approach which was approved by government in March 2024. Six professional sports (Australian football, cricket, football (soccer), rugby league, rugby union and basketball) have mainly user pays arrangements. There are no documented criteria for when to apply which funding model, however SIA has advised that it depends in part on the sporting organisation’s ability to pay for its own anti-doping testing.

17. The average cost of testing increased in the five years to 2022–23 and decreased in 2023–24. SIA has assessed the value-for-money of its laboratory testing arrangements. (see paragraphs 3.7 to 3.24)

18. SIA has developed national anti-doping education plans in each year between 2021–22 and 2023–24, as required by the World Anti-Doping (WAD) Code and SIA Regulations. SIA’s 2023–24 national education plan is consistent with requirements of the WAD Code. Sport specific education plans were developed for all sampled sports except one in 2023–24, following failure to develop sport-specific education plans for one sampled government funded sport and most sampled user pays sports in 2021–22 and 2022–23. SIA has fit for purpose arrangements to evaluate the effectiveness of the national education plan. Evaluations have found that most deliverables and outcomes relating to the national education plan were met. SIA has evaluated sport-specific education plans. (see paragraphs 3.25 to 3.42)

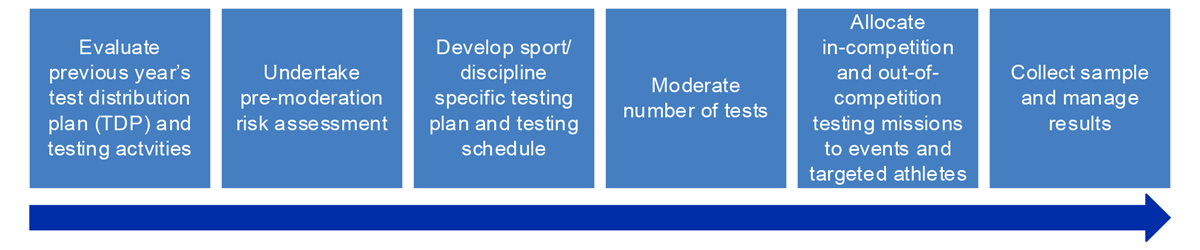

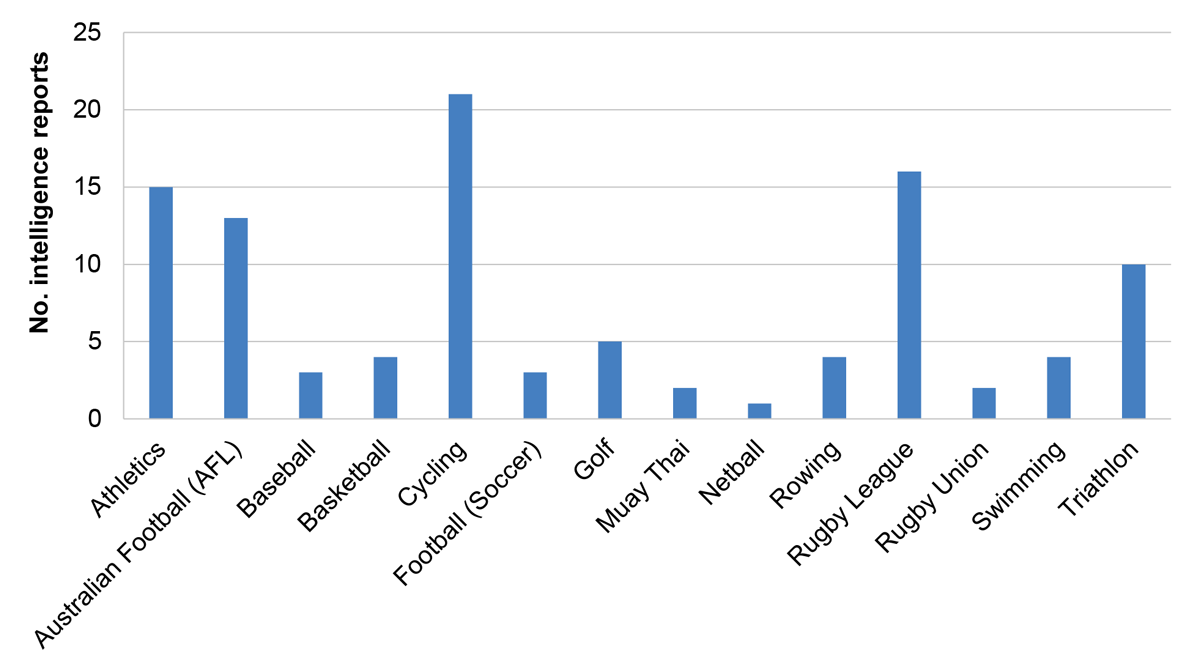

19. SIA undertakes an annual anti-doping test distribution planning process that is consistent with the World Anti-Doping (WAD) Code for sports with mainly government funded testing arrangements. Evaluation of previous years’ plans (one component of the WAD Code requirements) to inform improvements to current year planning is not supported by a clear methodology and could be better documented. SIA alters (moderates) the results of the risk-based test planning process using an undocumented methodology.

20. SIA’s test distribution planning for sports with mainly user pays testing arrangements is deficient in terms of systematic risk analysis informing the total number and distribution of planned tests. The total number and distribution of tests are negotiated with national sporting organisations representing user pays sports under a service agreement. Testing arrangements for user pays sports do not fully cover the off-season and pre-season.

21. In a sample of 25 government funded and user pays sports/disciplines, SIA’s testing activities for 2023–24 were mostly consistent with its planned test distribution planning. The minimum levels of analysis required under the WAD Code were achieved for all but one government funded and one user pays sport. (see paragraphs 3.43 to 3.85)

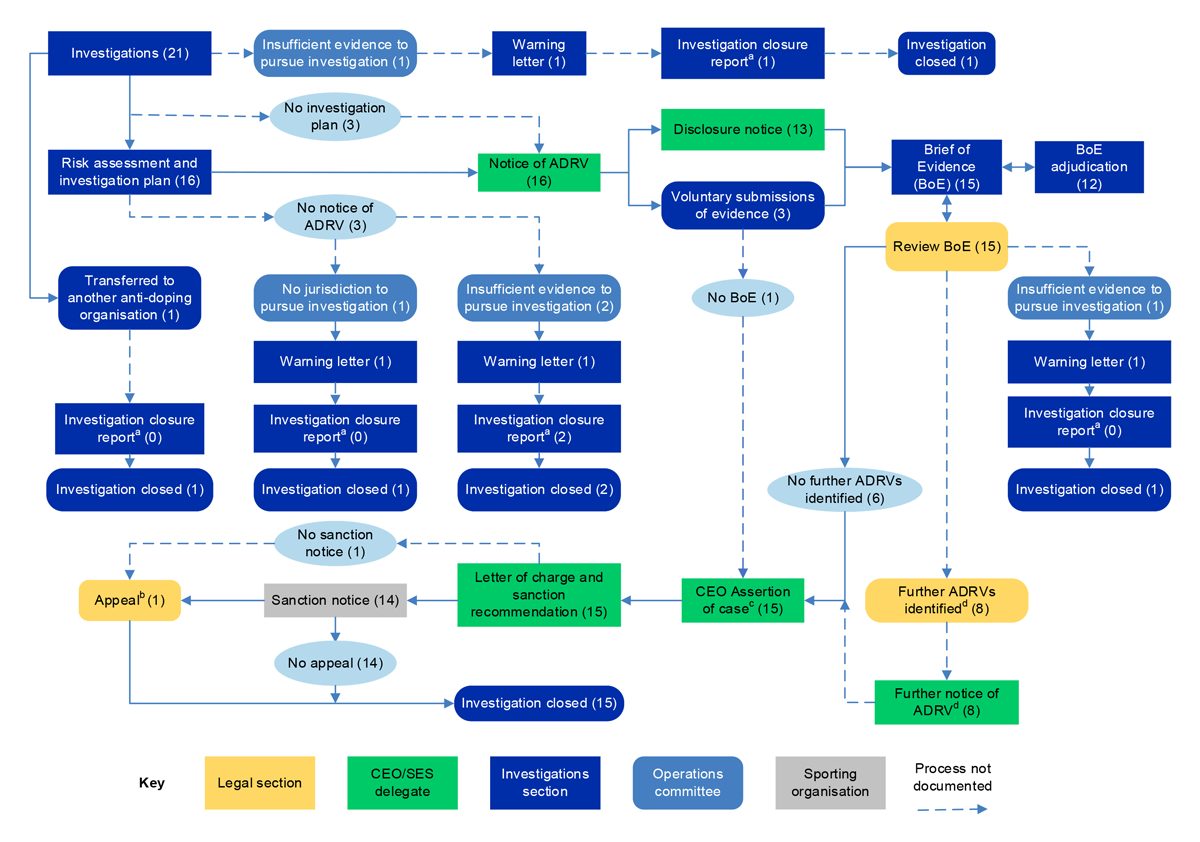

Anti-doping investigations and response

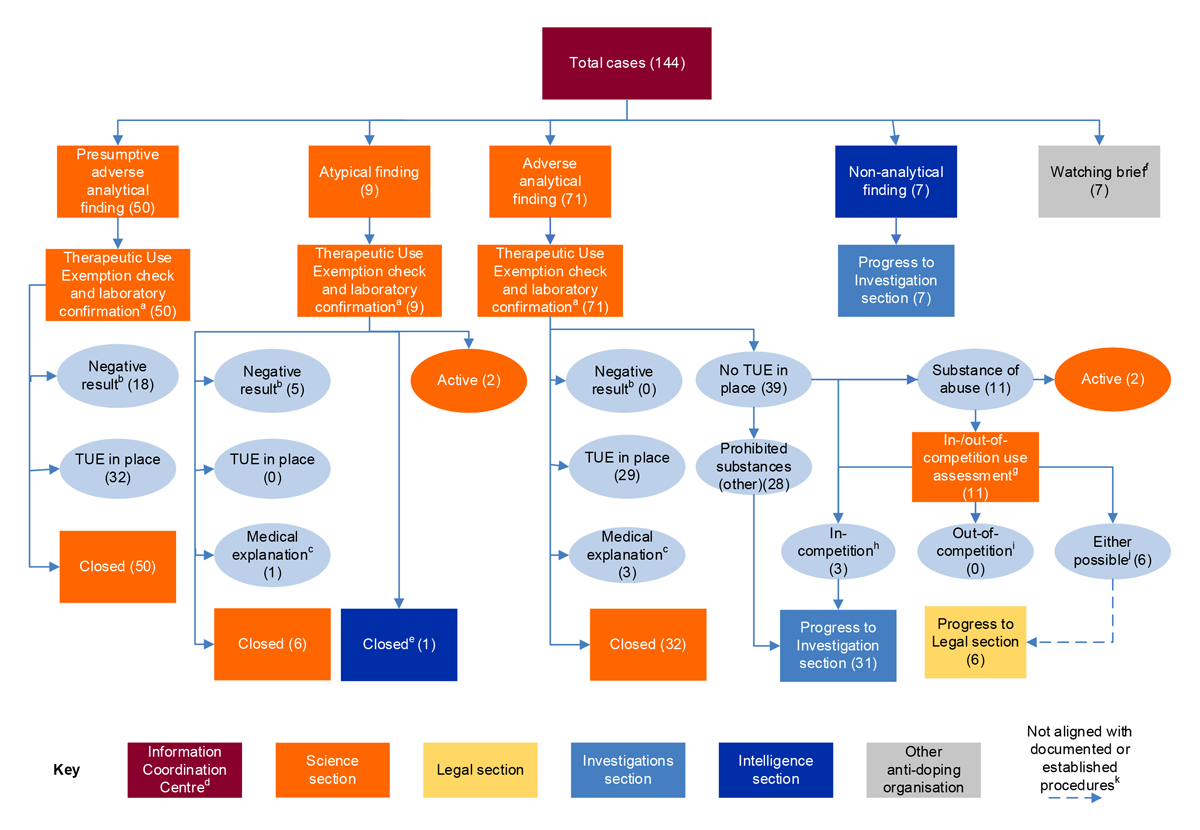

22. SIA established an investigations manual in 2020, which as of September 2024 had not been updated to align with the Australian Government Investigations Standard 2022. Elements of AGIS requirements related to information and evidence management, investigative personnel and investigative practices could be better reflected in SIA’s framework for conducting investigations. Quality assurance processes for investigations have largely not been established.

23. Between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024, 144 anti-doping rule violation cases were recorded in SIA’s case management system, and 38 proceeded to an investigation or ‘administrative’ treatment. There is a lack of documented procedures for a type of case (non-analytical findings) and treatment of these cases was inconsistent.

24. Six of 38 investigations commenced between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024 lacked investigation plans, with no documented reason for five. SIA does not have a procedure for the preparation and service of disclosure notices to athletes, and disclosure notice practices were inconsistent. SIA did not follow up using established mechanisms on athlete non-compliance with disclosure notices. A brief of evidence adjudication was appropriately prepared for 19 of 26 investigations involving a brief of evidence. Of the 38 investigations commenced since 1 July 2021, 21 were finalised by 30 June 2024 (15 resulting in a sanction). SIA states that it prepares closure reports only for matters where the decision is ‘no further action’. Three of five investigations resulting in ‘no further action’ had a closure report. Closed investigations did not meet timeliness benchmarks. (see paragraphs 4.2 to 4.54)

25. Anti-doping rule violation sanctions imposed by SIA between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024 were largely consistent with WADA requirements. (see paragraphs 4.55 to 4.62)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.17

Sport Integrity Australia develop effectiveness and efficiency measures and targets for anti-doping testing and investigations activities, consistent with requirements established in the Commonwealth Performance Framework.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.44

Sport Integrity Australia improve its controls for identifying and managing potential conflicts of interest, including those arising from gifts and benefits.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.45

Sport Integrity Australia establish a procedure for the test distribution planning process for user pays sports.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.50

Sport Integrity Australia establish a documented methodology for evaluating test distribution planning for government and user pay sports, and document outcomes from evaluations.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.61

Sport Integrity Australia undertake annual risk assessment to inform test distribution planning for all sports subject to regulation, including user pays sports.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.9

Sport Integrity Australia establish controls to ensure its documented investigative practices and procedures are implemented, or update procedures to reflect current endorsed practice.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.16

Sport Integrity Australia implement a quality assurance process for investigations that captures all types of investigations.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

26. The proposed audit report was provided to SIA. SIA’s summary response is reproduced below. The full response from SIA is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed at Appendix 2.

Sport Integrity Australia welcomes the findings in the ANAO audit report on Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme and agrees with the recommendations.

These recommendations will further contribute to our continuous improvement along with our obligations to implement and enforce rules and policies relating to anti-doping in Australian sport.

The National Anti-Doping Scheme provides Australia with the legislative basis to implement obligations under the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport, and in turn, the World Anti-Doping Code (the Code). The Code, and its associated mandatory International Standards, create an important, but complex set of global expectations for all National Anti-Doping Organisations.

The World Anti-Doping Agency through its most recent Code Compliance process (2022–2023) found Sport Integrity Australia to be fully compliant with all aspects of the Code. Indeed, this process highlighted the capabilities of Sport Integrity Australia far exceed many other national anti-doping agencies.

The ANAO recommendations (noting the recommendations are limited to a small section of just one of the five relevant International Standards), are valuable as we look to continually improve our program. To this end, we have already begun taking steps to implement all recommendations.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

27. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

Integrity in Australian sport

1.1 On 5 August 2017, the Minister for Health and Aged Care announced a review of Australia’s sport integrity arrangements as part of the development of the National Sport Plan.3 The Report of the Review of Australia’s Sport Integrity Arrangements (the Wood Review) was presented to the government in March 2018.4 The Wood Review made 52 recommendations across five key themes, comprising: a stronger national response to match-fixing; Australian sports wagering scheme; enhancing Australia’s anti-doping capability; a national sports tribunal; and a national sports integrity commission. The Australian Government released its response to the Wood Review, Safeguarding the Integrity of Sport, on 12 February 2019.5 The government agreed, agreed in part, agreed in principle or noted all 52 recommendations.

Sport Integrity Australia

1.2 Recommendation 38 of the Wood Review was6:

That the Australian Government establish a National Sports Integrity Commission to cohesively draw together and develop existing sports integrity capabilities, knowledge and expertise, and to nationally coordinate all elements of the sports integrity threat response including prevention, monitoring and detection, investigation and enforcement.

1.3 The Australian Government’s response to the Wood Review stated it would establish a national sports integrity commission, which would be called Sport Integrity Australia (SIA).7 SIA was established on 1 July 2020 by the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020 (SIA Act).8

1.4 The object of the SIA Act is to establish SIA to prevent and address threats to sports integrity and to coordinate a national approach to matters relating to sports integrity in Australia, with a view to: achieving fair and honest sporting performances and outcomes; promoting positive conduct by athletes, administrators, officials, supporters and other stakeholders, on and off the sporting arena; achieving a safe, fair and inclusive sporting environment at all levels; and enhancing the reputation and standing of sporting contests and of sport overall.9 SIA assumed responsibility for sport integrity functions that were being undertaken by the Department of Health’s National Integrity of Sport Unit10, the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA)11 and the Australian Sports Commission.12

1.5 SIA is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity in the health and aged care portfolio and is a statutory agency. The accountable authority of SIA is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). In 2023–24, total administered and departmental resourcing was $56.5 million and the average staffing level was 172 (Figure 1.1).13

Figure 1.1: Annual resourcing and average staffing level, 2020–21 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of SIA annual reports.

1.6 SIA is responsible for implementing several components of the government’s response to the Wood Review including: enhanced anti-doping and criminal intelligence capabilities; reforming sports wagering to protect the integrity of sport; and ratifying the Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions (Macolin Convention).14

National Integrity Framework and National Anti-Doping Scheme

1.7 The National Integrity Framework (NIF) is a set of templated integrity policies that all members of a sport should follow in relation to their behaviour and conduct in sport. The NIF is supported by the Sport Integrity Standards, which set out mandatory policy inclusions for national sporting organisations that do not adopt the NIF-templated integrity policies.15 SIA states that the NIF was developed in consultation with the Australian Olympic Committee, Paralympics Australia and Commonwealth Games Australia, following a 2020 Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) review into integrity issues in gymnastics.16

1.8 As of September 2024, 94 sporting organisations had signed up to the NIF, including 81 national sporting organisations and national sporting organisations for people with disability and 13 other sporting organisations.17 As of September 2024, nine national sporting organisations had not signed up to the NIF. These nine organisations are the Australian Football League, Basketball Australia, Cricket Australia, Football Australia, National Rugby League, Netball Australia, Rugby Australia, Surf Life Saving Australia, and Tennis Australia.

1.9 A National Anti-Doping Scheme (NAD Scheme) is required under section 3 of the SIA Act and is set out in schedule 1 of the Sport Integrity Australia Regulations 2020 (SIA Regulations).18 The SIA Regulations outline the powers and functions of the SIA CEO in implementing the NAD Scheme, which include having the role and responsibility of a ‘national anti-doping organisation’ for Australia under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Anti-Doping Convention and the World Anti-Doping Code (WAD Code).19

1.10 The UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport20 is based upon the WAD Code, which was released by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)21 and first adopted in 2003. The WAD Code is the core document that harmonises anti-doping policies, rules and regulations around the world.22 It works in conjunction with eight ‘International Standards’, which aim to foster consistency among anti-doping organisations.23 The most recent version of the WAD Code was effective as of 1 January 2021.

1.11 SIA’s role as the ‘national anti-doping organisation’ for Australia under the WAD Code means that it is the entity designated within Australia as possessing the primary authority and responsibility to adopt and implement anti-doping rules, direct the collection of samples, manage test results and conduct results management, at the national level.24 The SIA Regulations state that the functions of the CEO under the NAD Scheme include providing services relating to sports drug and safety matters to a ‘sporting administration body’; and sample collection and undertaking results management for a ‘sporting administration body’, regardless of whether or not the CEO has conducted the sample collection. The SIA Regulations set out the authority for the CEO to exercise certain powers in relation to ‘sporting administration bodies’. The SIA Regulations define a ‘sporting administration body’ as a national sporting organisation for Australia.25

Sporting organisations

1.12 The Australian Sports Commission (ASC) reports on almost 400 different sports and activities in Australia through its continuous AusPlay survey.26 The ASC defines ‘organised sport’ as that which is differentiated by ‘the degree of organisation or institutional structure that surrounds and influences the sport’.27 In Australia, some organised sports are represented by national sporting organisations (NSOs) or national sporting organisations for people with disability (NSODs). NSO and NSODs are organisations that the ASC supports to achieve the Australian Government’s sporting objectives, including through funding.28 NSOs and NSODs are formally ‘recognised’ by the ASC and listed in the Australian Sports Directory.29 Organisations recognised as NSO/NSODs have met certain criteria that assist the ASC in determining whether an organisation is ‘considered the pre-eminent body for the sport they represent in Australia, has sufficient standing within its sport and has adequate governance’.30 As of September 2024, there were 81 recognised NSOs and nine recognised NSODs.31

1.13 ASC NSO/NSOD recognition criterion 8 (integrity) includes that the sporting body has adopted, implemented, and enforced an anti-doping policy that has been approved by SIA and that complies with the WAD Code and NAD Scheme.32 NSOs and NSODs have anti-doping functions and responsibilities under the SIA Regulations.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.14 In its response to the Wood Review, the Australian Government committed to ‘comprehensively protecting the integrity of Australian sport for the benefit of the entire Australian community’ and to establishing a national sports integrity commission (SIA).33 The government also noted the importance of effective anti-doping measures to protect the integrity of Australian sport.

1.15 The audit provides assurance to the Parliament as to whether SIA has established effective governance arrangements for anti-doping and is effectively managing the National Anti-Doping Scheme.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The purpose of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Sport Integrity Australia’s management of the National Anti-doping Scheme.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements?

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established effective arrangements to prevent and detect anti-doping rule violations?

- Has Sport Integrity Australia established effective arrangements to investigate and respond to possible anti-doping rule violations?

1.18 The period covered by the audit is 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2024. Anti-doping matters prior to the establishment of Sport Integrity Australia on 1 July 2020 are not within the scope of this audit.

Audit methodology

1.19 The methodology involved:

- examining SIA documentation including annual reports, policy documents, minutes of meetings, anti-doping education and test planning documents, investigation records and emails;

- high-level examination of relevant record management systems and associated data;

- meetings with SIA personnel;

- meetings with representatives of NSOs and NSODs; and

- analysing 31 submissions to the audit from individuals and sporting bodies.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $690,000.

1.21 The team members for this audit were Michael Commens, Lily Engelbrethsen, Katiloka Ata, Mahkaila Sansom, Amanda Elliot and Christine Chalmers.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Sport Integrity Australia’s (SIA’s) governance arrangements for its anti-doping activities are fit for purpose.

Conclusion

SIA’s governance arrangements for the National Anti-Doping Scheme are partly fit for purpose. There are largely fit-for-purpose oversight and assurance arrangements. Risk management, including for regulatory capture risks, is not fit for purpose.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving performance reporting of anti-doping activities and managing regulatory capture risks. There was one opportunity for improvement relating to advisory committees.

2.1 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out requirements for Australian Government entities, including regulators, to establish systems of internal control and to inform the minister on the activities of the entity.34 Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk oversight and management for the entity. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy sets out the principles and mandatory requirements for managing risk.35 To assist entities in managing integrity risks, the National Anti-Corruption Commission has developed a Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework which outlines eight integrity principles derived from Australian Government integrity laws, policies and procedures. The eighth principle is to periodically assess the maturity of the entity’s management of integrity risks.36

Are there fit-for-purpose oversight and assurance arrangements?

SIA has responded to the Minister for Sport’s statement of expectations with an appropriate statement of intent. There are management arrangements and governance bodies that give consideration to anti-doping matters. These include advisory bodies that have been established in accordance with the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020. Governance bodies operate in accordance with legislative requirements or terms of reference, except for the declaration of interests on two key advisory bodies. SIA’s public performance reporting includes measures related to anti-doping. There is no performance reporting specifically related to anti-doping testing and investigations — a key regulatory function. There is no measure that goes to the effectiveness or efficiency of SIA’s anti-doping activities. Performance reporting on anti-doping in 2023–24 was not fully accurate. SIA reports integrity and anti-doping matters of significance to the Minister for Sport.

Statements of expectations and intent

2.2 Statements of expectations articulate ministers’ expectations for regulators’ strategic direction, reference projects, reforms and key developments. The Minister for Sport’s (the minister) expectations of SIA in relation to anti-doping are for it to ‘implement the World Anti-doping Code [WAD Code] and deliver a comprehensive anti-doping program to protect the health of Australian athletes and the integrity of sport’.37

2.3 Resource Management Guide 128 – Regulator performance (RMG 128) states that the regulator’s response to the statement of expectations should be in the form of a regulator statement of intent.38 The minister’s 2023 statement of expectations and SIA’s corresponding 2024 statement of intent are published on SIA’s website, replacing the 2020 statements of expectations and intent.

2.4 SIA’s 2024 statement of intent lists anti-doping as one of its nine priorities.39 In relation to its practical implementation of the anti-doping priority, it refers to its implementation of the WAD Code (see paragraph 1.10), an anti-doping program, anti-doping testing activities, and educational initiatives, citing 2022–23 statistics relating to these activities.40 The statement of intent does not specifically refer to how it is implementing the government’s response to the Wood Review (see paragraph 1.1), including agreed recommendations related to anti-doping. The statement of intent provides a status update on the adoption of the National Integrity Framework (see paragraph 1.7) by national sporting organisations (NSOs) and national sporting organisations for people with disability (NSODs) (see paragraph 1.12) and on the implementation of the Australian Sports Wagering Scheme.41

Line management and governance committees

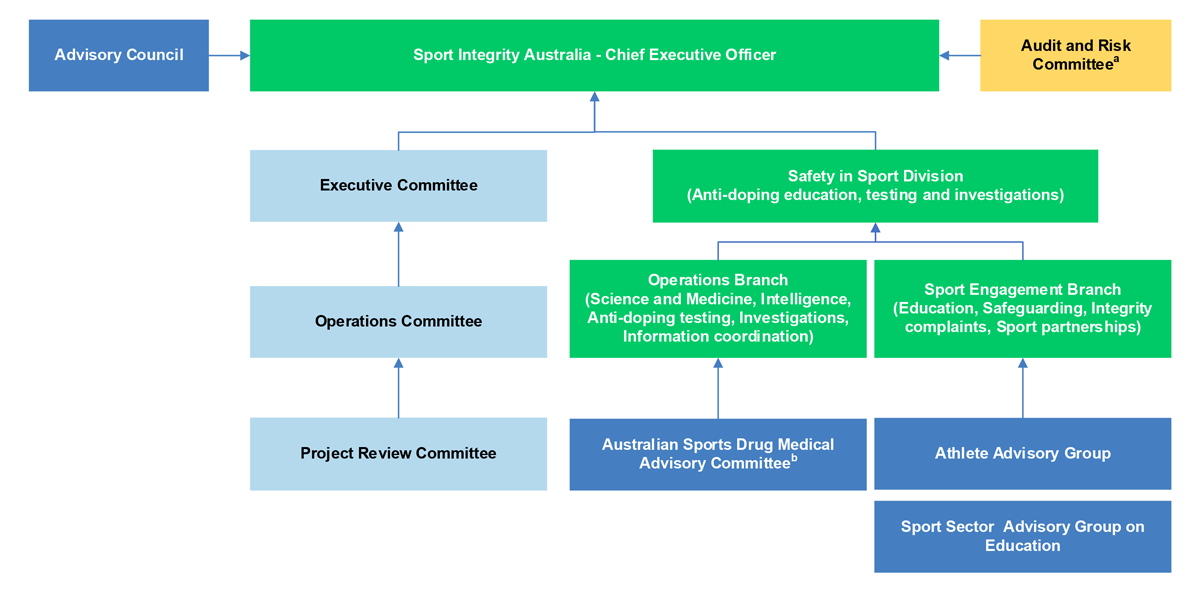

2.5 Figure 2.1 sets out SIA’s management and governance committees relevant to the administration of the National Anti-Doping (NAD) Scheme (see paragraph 1.9).

Figure 2.1: Management arrangements and governance committees relevant to the NAD Scheme

Note a: SIA’s Audit and Risk Committee receives reporting from SIA and is responsible for providing assurance advice to SIA.

Note b: The Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee’s primary role is to manage Therapeutic Use Exemptions (TUEs), it also provides advice on anti-doping and safety in sport.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.6 Appendix 3 examines terms of reference, membership, meeting frequency, functions, management of potential conflicts of interest, management of risk and discussion of anti-doping and other integrity matters for each oversight committee and advisory body shown in Figure 2.1. In summary:

- Terms of reference — The committees and bodies have terms of reference that set out functions and other requirements, except for the Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee (ASDMAC), the functions for which are established in the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020 (SIA Act). Terms of reference for three oversight committees (the Executive Committee, Operations Committee and Project Review Committee) were established in 2024.

- Membership and composition — Terms of reference or SIA Act requirements for three of four advisory bodies (the ASDMAC, Athlete Advisory Group and Sport Sector Advisory Group on Education) indicate that diversity of membership or specific qualifications are required. ASDMAC and the Athlete Advisory Group maintained appropriate membership arrangements, including arrangements for diverse representation where relevant. NSODs or people from First Nations backgrounds are not represented on the Sport Sector Advisory Group on Education. SIA advised the ANAO in November 2024 that ‘In alignment with [terms of reference], diversity of membership is to be met “where possible”. No [expressions of interest] were received from members of NSODs or people from First Nations backgrounds’. SIA did not undertake any additional activities to achieve diverse representation.

- Meeting frequency — The oversight committees and advisory bodies met as required under terms of reference, except for the Operations Committee and Sport Sector Advisory Group on Education.

- Management of potential conflicts of interest — Terms of reference for advisory bodies require declarations be made to the minister or chair of the body, depending on the body.

- Advisory Council — Section 33 of the SIA Act requires members to disclose interests to the minister. The charter states that members will be asked to complete a deed poll at the commencement of the appointment and annually thereafter. December 2022 advice to the minister included disclosures of private interests for all eight members. However, an annual deed poll was not completed as required in 2024 for any members. One member did not disclose their interests in a business contracted to undertake work for SIA. Based on meeting minutes, several Advisory Council members with wagering interests did not consistently declare these interests at meetings where wagering was discussed.42

- ASDMAC — Section 58 of the SIA Act requires members to disclose interests to the minister. There were 10 instances where declarations of personal interests were not made as required to support the appointment and reappointment of ASDMAC members by the minister. Declarations of member interests are documented in minutes for each meeting of ASDMAC.

- Athlete Advisory Group — Declarations were made by the 11 members on appointment. Potential conflicts of interest were not disclosed or discussed at any meetings.

- Sport Sector Advisory Group on Education — There were no documented declarations of conflicts of interest in meeting minutes or otherwise declared to the Chair in the time period examined by the audit.

- Management of risks —

- The Executive Committee, which has responsibility for risk identification, discussed operational risks at 27 of 98 meetings (28 per cent) where minutes were taken. These included risks relating to the management of conflicts of interest and anti-doping. There is no evidence from the minutes that the Executive Committee considered the enterprise risk register.

- The Audit and Risk Committee noted SIA’s enterprise risk register or deficiencies in SIA’s risk management framework at 14 of 16 meetings held in the period examined. Papers relating to enterprise risk management were either ‘taken as read’ or ‘noted’. The Audit and Risk Committee requested some changes to the policy, including that timeframes are clearly defined, and language is kept consistent. The Audit and Risk Committee prepares written advice for the SIA CEO annually through an annual report. The Audit and Risk Committee advised the CEO in December 2023 that SIA’s system of risk oversight and management improved during 2023 but was still developing and that SIA would benefit from further work on embedding the risk appetite and tolerance statements, and re-developing the enterprise risk register. The Audit and Risk Committee’s 2024 annual report was not complete as of 31 January 2025.

- Consideration of anti-doping — All committees and bodies considered anti-doping matters consistent with the applicable charter or terms of reference.

Opportunity for improvement

2.7 Sport Integrity Australia could:

- make proactive efforts to appoint representatives from National Sporting Organisations for People with Disability and First Nations peoples to the Sport Sector Advisory Group on Education, in accordance with the intent of the terms of reference for this committee; and

- review its controls for the appropriate declaration of interests on the Advisory Council and Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee.

Performance reporting

2.8 RMG 128 states that regulator statements of intent should, among other elements, outline how progress against meeting the minister’s expectations will be measured and reported on.43 The minister’s expectations with regard to SIA’s general regulatory functions include that:

I expect you to incorporate regulator performance reporting into the entity’s reporting processes, as required under the [PGPA Act] and [PGPA Rule].44

2.9 SIA’s statement of intent does not explain how progress against meeting the minister’s expectations will be measured and reported on, beyond a general statement that it ‘has incorporated regulator performance reporting into the agency’s reporting processes, as required under the [PGPA Act] and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014’.

2.10 The Commonwealth Performance Framework45, RMG 12846 and RMG 13147 establish requirements for the development and implementation of annual performance measures that include measures of the entity’s outputs, efficiency and effectiveness. SIA publicly reported its performance results in annual performance statements. SIA’s 2021–22 annual performance statements comprised five measures without targets, and the 2022–23 annual performance statements comprised four of the five measures from 2021–22. Anti-doping regulation was considered in the context of three of the four 2022–23 measures. SIA stated that it ‘met’ all five measures in 2021–22 and all four measures in 2022–23, including the three related to anti-doping regulation.

2.11 New performance measures were set out in the 2023–2027 Corporate Plan, which had a greater focus on quantitative measurement of outputs. There were four new measures and seven ‘performance results’. SIA’s 2023–24 performance measures were mostly activity or output measures and did not include measures of effectiveness or efficiency.

2.12 SIA’s 2023–24 annual performance statements stated that of seven ‘performance results’, it met four, substantially met two and did not meet one. Results for five ‘performance results’ that had a direct anti-doping element are described in Table 2.1. These were all reported as ‘met’ or ‘substantially met’.

Table 2.1: Annual performance statements (selected measures related to anti-doping), 2023–24

|

Measure |

Performance result |

Anti-doping element |

SIA assessment |

Result |

|

|

1.1 |

Design of a survey |

Survey includes questions related to anti-doping |

Met |

A ‘Positive Behaviours in Sport’ survey of participants and coaches was designed in 2023–24 and was intended to be delivered in August 2024.a |

|

1.2 |

Completion of education programs |

Education programs include those on anti-doping |

Met |

119,252 education program completions against a target of 88,000. |

|

|

2.1 |

Design and implementation of sport integrity threat assessmentsb for five sports |

Threats include improper use of drugs and medicine in sport |

Met |

Threat assessments were conducted for weightlifting, gymnastics, cycling (BMX), swimming and football. |

|

2.2 |

Review of recognised sports’ integrity policies and recognised sports’ compliance with anti-doping policy requirements |

Consideration of anti-doping policies |

Met |

100 per cent of recognised sports’ integrity policies reviewed and 98 per cent of recognised sports compliant with anti-doping policy requirements. |

|

|

3.1 |

Publication of threat assessments and analytical reportsc |

Threat assessments addressed doping methods |

Substantially met |

Ten threat assessments published against a target of ten and three analytical reports published against a target of five. |

Note a: SIA advised the ANAO in September 2024 that the ‘Positive Behaviours in Sport’ survey had not yet been implemented due to ‘IT and security-related delays’.

Note b: Threat assessments provide an assessment of an emerging or enduring threat posed by, or to, a specific sport, person, or cohort.

Note c: Analytical reports address threats to sports integrity such as doping methods, manipulation of sporting competitions and the sharing of operational information relating to the safety of sporting participants.

Source: ANAO analysis of SIA 2023–2027 Corporate Plan and 2023–24 Annual Report.

2.13 SIA inaccurately reported its performance against performance measure 3.1 (publication of threat assessments and analytical reports) as ‘substantially met’.48 Six of 10 (60 per cent) threat assessments were completed and published and three of five (60 per cent) analytical reports were completed and published in 2023–24.49 In calculating that it had met the performance measure for threat assessments, SIA included six threat assessments and four ‘intelligence briefs’. The length, format and breadth of analysis in an intelligence brief is different to that of a threat assessment.

2.14 Anti-doping sample collection and investigations are significant elements of SIA’s regulatory responsibilities. SIA reported in its 2022–23 Annual Report that 58 per cent of NSO representative respondents to a stakeholder survey said SIA was effective in helping them detect sports integrity threats in their sport through testing and investigations.50 Anti-doping sample collection and investigations were not directly incorporated into performance reporting in 2021–22, 2022–23 or 2023–24, reducing transparency over a key regulatory activity.

2.15 Article 14 of the WAD Code states that at least annually, national anti-doping agencies like SIA are to publish a general statistical report of their doping control activities, with a copy provided to WADA at least annually. WADA annually publishes statistical reports as reported by the WADA-accredited laboratories and national anti-doping organisations.51 SIA publishes in its annual report the number of samples collected by year since 2002–03 and the number and type of disclosure notices (see paragraph 4.38) for the current year.52 This is not provided to WADA however the annual report is available on SIA’s website.53

Recommendation no.1

2.16 Sport Integrity Australia develop effectiveness and efficiency measures and targets for anti-doping testing and investigations activities, consistent with requirements established in the Commonwealth Performance Framework.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

2.17 While no globally recognised measure of effectiveness exists for anti-doping testing, we have previously recognised the need to include such measures in our reporting. We will continue to explore options for the most appropriate measure/s, available to us at this point in time, to include in our 2025/26 Corporate Plan and seek to develop longitudinal datasets to inform future effectiveness and efficiency measures.

Advice to government

2.18 Under section 21 of the SIA Act, the CEO of SIA is obliged to inform the minister about matters relating to any of the CEO’s functions. Between 2021–22 and 2023–24, SIA advised government on a range of strategic and operational anti-doping matters, as well as broader integrity issues in sport, such as the Australian Sports Wagering Scheme, ratification of the Macolin Convention (see paragraph 1.6) and implementation of the National Integrity Framework. SIA did not provide advice to government on some anti-doping risks (for example, risks associated with delays in the finalisation of several NSO anti-doping policies, or risks associated with sports outside of SIA’s regulatory remit or user pays sports (see paragraph 3.17).

2.19 Section 67A of the SIA Act outlines the meaning of protected information in the context of the SIA Act, which is information obtained under or for the purposes of the SIA Act and that relates to the affairs of a person, or identifies, or is reasonably capable of being used to identify, the person. In February 2023, SIA obtained internal legal advice affirming that under section 68(c) of the SIA Act, SIA was authorised to disclose protected information to the minister. Between May 2023 and February 2024, SIA advised the minister on matters relating to anti-doping investigations involving individual athletes, which included protected information. The purpose of the briefings was to provide background information and ‘talking points’ for the minister in recognition of the likely media interest. No decision or direction was sought from the minister in accordance with subsection 24(2) of the SIA Act (which does not permit the minister to give directions to the SIA CEO in relation to a particular athlete who is subject to the NAD Scheme or anti-doping testing).

2.20 Resource Management Guide 135 Annual reports for non-corporate Commonwealth entities establishes requirements for the accountable authority to certify in annual reporting that fraud has been appropriately dealt with by the entity.54 In 2021–22, 2022–23 and 2023–24 annual reports, SIA’s accountable authority provided this certification, including that the agency had prepared fraud risk assessments and fraud control plans. SIA prepared fraud risk assessments but did not prepare fraud control plans in 2021–22 or 2022–23. A fraud and corruption control plan was drafted in July 2024 and endorsed in October 2024. A fraud and corruption control procedure (which states that it should be read in conjunction with the fraud and corruption control plan) was finalised in July 2024.

Is there fit-for-purpose risk management, including for regulatory capture risks?

Sport Integrity Australia established a risk management policy in 2021, which was updated in 2023. Risk appetite statements provided in different documents are inconsistent. There is an enterprise risk register, which was last updated in November 2021. Operational risk registers for specific business areas or activities, including for anti-doping, are not maintained. SIA undertook a review of its risk management framework in 2024, which concluded that the risk management framework required ‘significant’ work to comply with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. SIA commenced a body of work to improve SIA’s risk management framework. There is a largely fit-for-purpose policy framework for regulatory capture risks, including risks arising from conflicts of interest; external employment; gifts, benefits and hospitality; and sports betting. The policies are poorly implemented.

Risk management policy

2.21 SIA has a Risk Management Policy which was established in March 2021 and last updated in March 2023 The policy was due to be updated in March 2024 but as of September 2024, SIA has not reviewed or revised the Risk Management Policy.

Risk appetite

2.22 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy states that an entity’s risk management framework should include a risk appetite statement.55 SIA’s risk appetite is set out in its Risk Management Policy (Box 1). The Risk Management Policy refers to a December 2022 Risk Appetite and Tolerance Matrix, which uses a different risk tolerance rating scale to that set out in the SIA Risk Management Policy.56 Each sub-category of risk is assigned both an appetite and tolerance.57 The overall risk appetite statement in the SIA Risk Management Policy and the risk appetite assessments in the Risk Appetite and Tolerance Matrix are not consistent.58

|

Box 1: Sport Integrity Australia’s risk appetite for anti-doping risks |

|

Risk appetite is described in the Risk Management Policy as low for:

Risk appetite is described in the Risk Management Policy as higher for:

Anti-doping is addressed under the legal/compliance and reputational risk categories in the Risk Appetite and Tolerance Matrix. In relation to anti-doping, the risk appetite statement is that SIA has ‘no appetite’ for non-compliance with WADA and other international requirements; and ‘no appetite’ for reputational damage resulting from poor, inaccurate or misleading advice and support, especially in relation to anti-doping practices. |

Identification and assessment of risks

2.23 The SIA Risk Management Policy includes requirements to establish an enterprise risk register. The Risk Management Policy is supported by a Risk Management Procedure (March 2023, due for review in March 2025), which includes instructions for identifying, assessing, categorising and reviewing risks. Identified risks are to be reported, actively managed and monitored on at least a weekly basis for extreme risks and on at least a monthly basis for high risks.

2.24 An enterprise risk register was created in October 2020 and last updated in November 2021. The November 2021 enterprise risk register included 22 risks (comprising three high, nine significant, nine medium and one low) across three types (enterprise, general and capability). A significant anti-doping risk was ‘Compliance with the [WAD Code] and International Standards —Any function of the agency errs towards non-compliance with the [WAD Code] and/or doesn’t uphold any of the [International Standards]’. SIA maintains a separate fraud risk register.

2.25 Risk types do not align with the risk categories in the Risk Appetite and Tolerance Matrix or the Risk Management Procedure.59 Due to the use of different categories in the risk register to those set out in the tolerance statement, it is unclear if residual risk ratings after the application of controls are within accepted tolerance levels.

2.26 The 2022 Commonwealth Risk Management Policy includes requirements for non-corporate Commonwealth entities to define risk management responsibilities (element four); and periodically review the effectiveness of risk controls (element five). The November 2021 risk register includes references to controls and treatments for all risks as well as references to risk stewards by position. SIA has completed internal audits examining the effectiveness of some controls including: the fraud risk assessment and control plan (December 2021); contract management (March 2023); and corporate credit card use (January 2024).

2.27 In March 2024 SIA presented to SIA’s audit and risk committee a plan for an internal audit on the effectiveness of its risk management framework, which was to be completed by May 2024. In September 2024 the audit and risk committee was advised the report was complete and would be presented to it in December 2024. The draft report concluded that SIA’s risk management framework and supporting artefacts required ‘significant work to ensure alignment with the revised Commonwealth Risk Management Policy’. In March and September 2024, the audit and risk committee received a risk management update which stated that SIA had commenced a project to consolidate, refine and simplify enterprise risks and risk management artefacts. This included introducing a single overarching risk appetite statement.

2.28 The risk management updates provided to the audit and risk committee in March and September 2024 described several changes to be made to the enterprise risk register comprising: aligning enterprise risks to six risk themes60; refining enterprise risks to nine distinct risks61; refining tolerance statements to align with the new risk themes; ‘reengineering’ the register to align with a Department of Health and Aged Care template; and identifying emerging risks in an emerging risks register. The work was to be completed by Quarter 4, 2024–25.

2.29 The proposed enterprise risks do not specifically refer to anti-doping work or the National Integrity Framework. Operational risk registers for specific business areas or activities, including for anti-doping and the work of the Operations and Sport Engagement branches (see Figure 2.1) are not maintained. SIA advised the ANAO in November 2024 that ‘information on more targeted risk events that relate specifically to a certain operational capability or regulated business function will be detailed in section level risk registers as part of the business planning process currently being re-developed’. A business planning template that includes an area for listing and analysing ‘section level risk events’ was developed in January 2025.

Regulatory capture risks

2.30 The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services’ 2019 report on oversight of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) defines regulatory capture as instances where regulators are excessively influenced or effectively controlled by the industry they are supposed to be regulating.62 Other than references to general fraud and corruption risks, SIA has not identified or assessed its regulatory capture risks and has not evaluated its regulatory capture risk maturity. There have been no internal audits that examine regulatory capture risks.

2.31 Conflict of interest risks, including through a regulator’s acceptance of gifts and benefits or through secondary employment, are a type of regulatory capture risk.63 The Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) which governs members of the Australian Public Service (APS)64 includes the APS Values and Code of Conduct. These outline requirements for APS employees in managing conflicts of interest.65 The Australian Public Service Commission’s (APSC’s) APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice outlines requirements for at least annual Senior Executive Service (SES) declarations66; notifications of outside employment67; and avoiding the acceptance of gifts or benefits.68 The APSC also issues Guidance for agency heads — gifts and benefits.69 This states that any gift or benefit accepted by the agency head with a value of more than $100 must be disclosed in a public register on the agency’s website.70 Although not a requirement, the guidance states that ‘there is a strong expectation that agency heads will also publish gifts and benefits received by staff in their agency that exceed the threshold of [$100]’.71

2.32 SIA must also comply with the conflict of interest requirements set out in the WADA Guide for the Operational Independence of National Anti-Doping Organizations72, the SIA Regulations 2020 and the WADA International Standard for Testing and Investigations (see paragraph 3.6).

Policy framework

2.33 SIA has established policies and disclosure requirements for conflict of interest; outside employment; and gifts, benefits and hospitality.

- Conflict of interest — There is a Conflict of Interest Policy, which was endorsed in June 2021 with a review date of June 2022. The Conflict of Interest Policy was reviewed and updated in September 2024. The June 2022 policy applies to SIA employees, secondees, contractors, consultants, the CEO and Advisory Council members. The policy draws attention to the unique operating environment and business of SIA by noting that membership or participation in a sport, sporting organisation, or sporting environment may give rise to a conflict. The SIA Conflict of Interest Policy states that, in accordance with the SIA Regulations, SIA requires those engaged in anti-doping sample collection73 to disclose any personal interests as a condition of service.74

- Outside employment — There is an Outside Employment Policy, which was endorsed in May 2021 with a review date of June 2022. As of September 2024, the Outside Employment Policy had not been reviewed. The policy states that employees must complete and submit a ‘notification of outside employment form’ for consideration by the SIA delegate, upon commencement with SIA or upon undertaking outside employment. Where the delegate considers that the outside employment would represent a real or apparent conflict of interest with official duties, they can direct the applicant not to engage in outside employment.

- Gifts and benefits — There is a Managing an Offer of a Gift or a Benefit Policy and Procedure, which was endorsed in May 2022, and updated in August 2024. The policy applies to employees (ongoing/non-ongoing), secondees, contractors, consultants, the CEO, Advisory Council members, and family members where there is a clear link to official duties.75 Gifts and benefits (including sponsored travel and hospitality) offered to SIA employees must be ‘carefully considered’ before acceptance or rejection. Offers of gifts, whether accepted or declined, with a value exceeding $50 must be declared in SIA’s gifts and benefits register, and approval to accept gifts must be obtained by the deputy CEO or CEO before accepting the gift where possible. A decision tree and guidelines on when to refuse offers (including offers from people or organisations subject to regulatory decisions) are outlined in the policy.

2.34 SIA maintains a separate gambling policy that states SIA officials are prohibited from placing a bet (or any other form of financial speculation) on any sport where SIA has a relationship with the NSO or NSOD for that sport.

Management of conflicts of interest, outside employment and gifts and benefits

Conflicts of interest

2.35 SIA has a conflict of interest register, which contains 111 entries for non-SES staff that were submitted between April 2021 and March 2024.76 Almost half (N=49) were submitted in 2021. The register is incomplete for declared conflicts, including information about whether the delegate considered the declared conflict, and the risk associated with the declared conflict. The conflict of interest register contains two entries for SES staff (out of eight as of July 2024). One SES officer declared a conflict of interest in November 2022 through a conflict of interest declaration form that was not recorded in the conflict of interest register. There is a separate 2024–2026 register for casual doping control officers77 and chaperones78 which includes declared conflicts. Conflicts include sports betting accounts and relationships with SIA officials.

2.36 According to the Conflict of Interest Policy, on commencement and annually, SIA employees must declare all conflicts of interest (real, apparent or potential) by completing a conflict of interest declaration. There is a conflict of interest form for declarations. The form includes space for a management plan.

2.37 The ANAO reviewed conflict of interest declarations for: all SES officials engaged by SIA as of 1 July 2024 (N=8), and all non-SES SIA officials with a declared conflict of interest assessed as medium or high risk in the conflict of interest register (N=13).

- Senior Executive Service — SES declarations were not made in each applicable year for all SES officials. None of eight SES officials completed an annual declaration form for 2023–24.79 Of the four SES officials who made at least one declaration of a conflict in the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2024, none of the forms were complete, including in terms of the CEO’s review and required management of declared interests. It is unclear from all four SES forms as to whether the CEO considered the declared conflict to be material. For the four SES officials where there was at least one form in the period, none set out a management strategy.

- Other officials — Of the 13 non-SES officials with a declared conflict on the conflict of interest register that was assessed as medium or high risk, 12 had an approved conflict of interest declaration form. A management plan was documented for nine out of 11 conflicts where a plan was required. The one unapproved declaration had no specified plan.

Outside employment

2.38 Four out of the 21 officials examined (two SES and two non-SES) declared conflicts of interest relating to outside employment on a conflict of interest disclosure form. Between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2024, one ‘notification of outside employment form’ was submitted in accordance with the Outside Employment Policy.80 Conflict of interest forms do not require the same detail as the ‘notification of outside employment form’, such as information about the nature of the employment, the actual and perceived conflicts arising from the employment, or what was considered by the delegate in deciding whether to approve the arrangement.

2.39 For the five instances of outside employment disclosed, employment was with regulated entities or in a sport-related occupation. In two of the five forms, the delegate declared the described conflict (which may include multiple interests, besides outside employment) as constituting a real, apparent or potential conflict of interest and a management plan was established. The remaining three forms were incomplete and there was no indication if the delegate considered the conflict to be material. Management plans were not established in these three instances.

Gifts and benefits

2.40 As outlined at paragraph 2.31, Australian Government policy is that any gift or benefit accepted by an agency head with a value of more than $100 must be disclosed in a public register on the agency’s website. SIA publishes quarterly updates of the CEO’s gifts and benefit disclosures in accordance with its policy and Australian Government requirements.81 The public register also includes accepted gifts to other officials exceeding $100 in value.

2.41 As of May 2024, the quarterly public disclosures showed the acceptance of three gifts or benefits received between 1 January 2020 and 31 March 2024, with the highest value gift valued at $5,400. A 2020 gift to the CEO of Qantas Chairman’s Lounge membership was first disclosed in January 2024 and valued at $0.

2.42 The ANAO, through non-exhaustive analysis of email correspondence, identified that the CEO received at least 22 invitations to sporting or sports-related events from World Athletics, the Australian Olympic Committee, ACT Brumbies, Football Australia and the Australian Rugby League Commission. None of these offers were documented in the public register. There is evidence of the CEO accepting one invitation from the Australian Olympic Committee. Two other invitations were declined due to the CEO being unavailable. SIA did not maintain records of whether invitations and offers were declined or accepted by the CEO.

2.43 In addition, SIA maintains an internal register of gifts and benefits offered to SIA officials other than the CEO. All offered gifts exceeding $50, whether accepted or declined, must be declared on the internal register. Between July 2022 and September 2024, SIA officials disclosed eleven gifts or benefits, with the last entry made in December 2023. Through a non-exhaustive review, the ANAO identified that SIA officials accepted but did not disclose VIP tickets to a 2022 Women’s World Cup Basketball event and tickets to the Hancock Prospecting 2023 Rower of the Year Awards.

Recommendation no.2

2.44 Sport Integrity Australia improve its controls for identifying and managing potential conflicts of interest, including those arising from gifts and benefits.

Sport Integrity Australia response: Agreed.

2.45 We updated our process and systems for declaring conflicts of interest in September 2024. All Sport Integrity Australia staff were required to re-submit and have approved any previous or new potential conflicts. The Gifts and Benefits policy was updated in August 2024 and the process for declarations and delegate review is currently being streamlined, including documenting offers declined to sports-related events.

3. Anti-doping prevention and detection

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Sport Integrity Australia (SIA) has effective arrangements for implementing the National Anti-Doping Scheme including arrangements for anti-doping education and testing.

Conclusion

SIA’s arrangements for preventing and detecting doping are largely effective for sports that have mainly government funded anti-doping sample collection arrangements, and partly effective for the major professional sports that have mainly ‘user pays’ anti-doping sample collection arrangements, due to the way SIA has chosen to administer ‘user pays’ arrangements.

- There is a fit-for-purpose national anti-doping framework, which is supported by a national anti-doping policy that is adopted by 87 national sporting organisations. Another three national sporting organisations have an SIA-approved anti-doping policy.

- SIA has effective arrangements to prevent anti-doping rule violations through anti-doping education plans that are implemented and evaluated.

- For sports that have mainly government funded testing arrangements, test distribution planning is generally risk-based. Transparency could be enhanced through more comprehensive documentation of planning methodology and record keeping.

- For the six major sports that have mainly user pays testing arrangements, test distribution planning is not demonstrably risk-based. The number and distribution of tests are negotiated with national sporting organisations under a service agreement. This is not consistent with World Anti-Doping Code principles or SIA’s responsibilities as a regulator of these sports.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving the anti-doping detection process: documenting a methodology for sample collection distribution planning for user pays sports; improving evaluation of previous years’ test distribution planning; and undertaking risk-based test distribution planning for all regulated sports, including user pays sports. The ANAO identified two opportunities for improvement regarding documenting assessment criteria for sports’ anti-doping policies; and documenting anti-doping test planning moderation methodology.

3.1 Section 3 of the Sport Integrity Australia Act 2020 (SIA Act) and Schedule 1 of the Sport Integrity Australia Regulations 2020 (SIA Regulations)82 require SIA to establish a National Anti-Doping (NAD) Scheme that implements the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport (UNESCO convention). Article 3 of the UNESCO convention sets out that state parties to the Convention (including Australia) are required to adopt anti-doping measures at the national and international levels that are consistent with the principles of the World Anti-doping Code (WAD Code) (see paragraphs 1.9 to 1.10).83

3.2 Article 18 of the WAD Code states that education programs:

Are central to ensure harmonized, coordinated and effective anti-doping programs at the international and national level. They are intended to preserve the spirit of sport and the protection of [athletes’] health and right to compete on a doping free level playing field … Education programs shall raise awareness, provide accurate information and develop decision-making capability to prevent intentional and unintentional anti-doping rule violations and other breaches of the [WADA] Code.84

3.3 The SIA Regulations require SIA to plan, implement, evaluate and monitor education and information programs for doping-free sport for all participants and non-participants. One of eight International Standards introduced by World Anti-doping Agency (WADA) (see paragraph 1.10) is the International Standard for Education (January 2021).85 This sets out mandatory standards that support signatories in planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating effective anti-doping education programs.

3.4 SIA’s role as the ‘national anti-doping organisation’ for Australia under the WAD Code means that it is the entity designated within Australia as possessing the primary authority and responsibility to adopt and implement anti-doping rules, direct the collection of samples, manage test results and conduct results management, at the national level.86 The SIA Regulations state that the functions of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) under the NAD Scheme include providing services relating to sports drug and safety matters to a ‘sporting administration body’; and sample collection and undertaking results management for a ‘sporting administration body’. The SIA Regulations set out the authority for the CEO to exercise certain powers in relation to ‘sporting administration bodies’. The SIA Regulations define a ‘sporting administration body’ as a national sporting organisation for Australia (NSO).87 NSOs and national sporting organisations for people with disability (NSODs) are organisations that the Australian Sports Commission supports to achieve the Australian Government’s sporting objectives.88 NSOs and NSODs are formally ‘recognised’ by the ASC and listed in the Australian Sports Directory.89 As of September 2024, the Australian Sports Commission recognised 90 NSOs and NSODs (see paragraph 1.12).90

3.5 Article 5 of the WAD Code is concerned with anti-doping testing and investigations, and states that:

Testing and investigations may be undertaken for any anti-doping purpose. Testing shall be undertaken to obtain analytical evidence as to whether the [athlete] has violated Article 2.1 (Presence of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers in an Athlete’s Sample) or Article 2.2 (Use or Attempted Use by an Athlete of a Prohibited Substance or a Prohibited Method) of the [WADA] Code.91

3.6 The WAD Code states that anti-doping organisations should conduct test distribution planning and testing as required by the January 2023 International Standard for Testing and Investigations (ISTI).92 The ISTI sets out that effective and proportionate test planning will begin with a risk assessment that is informed by intelligence.93 The Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide 128 Regulator Performance (RMG 128)94 and August 2024 Regulatory Policy, Practice & Performance Framework95 establish a principle that regulators should take a risk-based, data-driven approach to regulation, among other principles.

Has Sport Integrity Australia established an effective anti-doping framework?

The Sport Integrity Australia Regulations 2020 establish the SIA CEO’s functions and powers in relation to anti-doping, which include sample collection and results management for ‘sporting administration bodies’, defined as ‘national sporting organisations for Australia’. SIA has established an Australian National Anti-Doping Policy (NAD Policy) that aligns with the World Anti-Doping Code and which, as of September 2024 had been adopted by 98 sporting organisations in Australia, including 87 national sporting organisations for Australia. Anti-doping policies for the remaining three national sporting organisations that have adopted alternative policies were not approved by SIA in a timely way using documented criteria.

SIA’s annual anti-doping activities are supported by approximately 300 full-time equivalent (FTE) and casual employees. Budgeted average staffing levels increased by six per cent for FTE staff and 17 per cent for casual staff between 2022–23 and 2024–25. The total number of anti-doping samples collected by SIA declined by 34 per cent between 2010–11 and 2022–23.

SIA provides anti-doping sample collection and analysis under two general funding models: government-funded and user pays. User pays arrangements involve partial cost recovery, an approach which was approved by government in March 2024. Six professional sports (Australian football, cricket, football (soccer), rugby league, rugby union and basketball) have mainly user pays arrangements. There are no documented criteria for when to apply which funding model, however SIA has advised that it depends in part on the sporting organisation’s ability to pay for its own anti-doping testing.

The average cost of testing increased in the five years to 2022–23 and decreased in 2023–24. SIA has assessed the value-for-money of its laboratory testing arrangements.

National Anti-Doping Policy

3.7 SIA established the NAD Policy on 1 January 2021. The purpose of the NAD Policy (Box 2) is to ‘have a single and consistent set of anti-doping rules across all sports in Australia’.96

|

Box 2: The Australian National Anti-Doping Policy |

|

The NAD Policy is comprised of 21 articles that cover requirements for prohibited substances, testing and investigations, analysis of samples, hearings, sanctions and consequences, confidentiality and reporting, education, and research, among other matters. Key aspects of the NAD Policy include:

|

Note a: Sport Integrity Australia, Anti-doping rule violations, SIA, available from https://www.sportintegrity.gov.au/what-we-do/anti-doping/anti-doping-rule-violations [accessed 9 September 2024].

Note b: Sport Integrity Australia, Substance banned in sport, SIA, Canberra, 2021, available from https://www.sportintegrity.gov.au/what-we-do/anti-doping/prohibited-substances-and-methods/substances-banned-sport [accessed 9 September 2024].

3.8 On November 2020, WADA confirmed that the draft NAD Policy appeared to be in line with the WAD Code, pending the implementation of minor edits proposed by WADA. The NAD Policy applies to ‘sporting administration bodies’ (defined as an NSO/NSOD97); member or affiliate organisations; board members, directors, officers and specified employees; and ‘delegated third parties’98 and their employees.

3.9 The SIA Regulations state that a sporting administration body must at all times have in place, maintain and enforce anti-doping policies and practices that comply with the mandatory provisions of the WAD Code, International Standards and the NAD Scheme.99 SIA assesses and reviews sporting bodies’ applications for adoption of the NAD Policy, which are approved, refused or revoked by the CEO. NSOs were required to have a SIA-approved, WAD Code-compliant anti-doping policy in place by 1 January 2021. Section 2.04 of the SIA Regulations state that a sporting administration body must not adopt or substantively amend its anti-doping policy unless approved by the CEO.

3.10 As of September 2024, 98 sporting organisations had adopted the NAD Policy, including 87 NSOs/NSODs and 11 other (non-recognised) sporting organisations.100 Three NSOs (Australian Football League (AFL), Australian Rugby League Commission (ARLC) and Football Australia) have not adopted the NAD Policy. AFL has its own anti-doping policy as a direct signatory to the WAD Code101, which SIA approved in March 2021. ARLC and Football Australia also have their own anti-doping policies, which were approved by the CEO in accordance with the SIA Regulations and the Australian Sports Commission NSO recognition criteria (see paragraph 1.12).102 Football Australia’s anti-doping policy was approved in June 2022 and ARLC’s anti-doping policy was approved in July 2022. During the period in which SIA worked with these NSOs to develop updated policies, they operated under previously approved anti-doping policies.