Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Security Assessments of Individuals

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of ASIO’s arrangements for providing timely and soundly based security assessments of individuals to client agencies.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) was established in 1949 as Australia’s national security intelligence service. The agency operates under the direction of the Director-General of Security who is accountable to the Attorney-General. ASIO’s role is to identify and investigate threats to security, wherever they arise, and to provide advice to protect Australia, its people and its interests.1 ASIO’s roles and responsibilities are set out in the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (the ASIO Act).

2. One of ASIO’s key responsibilities is to provide security assessments of individuals to other Australian Government client agencies. These assessments are defined in the ASIO Act and other legislation. The main types of assessments are:

- visa security assessments—undertaken for the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC)2;

- personnel security assessments—undertaken for the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) and AGSVA-exempt agencies3; and

- counter-terrorism security assessments—undertaken for AusCheck4 and the AFP.5

3. In the last six years, ASIO has completed, on average, 179 847 security assessments annually.6 The number of security assessments completed varies from year to year and between assessment types. Over this period (from 2005–06 to 2010–11), ASIO completed between:

- 34 000 and 73 000 visa security assessments annually (around 20 per cent to 40 per cent of the annual security assessment caseload);

- 18 000 and 31 000 personnel security assessments annually (around nine per cent to 16 per cent of the annual caseload); and

- 65 000 to more than 135 000 counter-terrorism security assessments annually (around 40 per cent to 66 per cent of the annual caseload).

4. Demand for security assessments and the complexity of the security assessment caseload fluctuates, driven by changes in the security environment and other factors. For example, Aviation Security Identification Card (ASIC), Maritime Security Identification Card (MSIC) and National Health Security (NHS) checks generally require counter terrorism security assessments every two years.7 By contrast, demand for visa security assessments is affected by factors such as changes in the movements of people, particularly those seeking to claim protection, and in Government policies in relation to such people.

5. ASIO security assessments can range from a basic check of personal details against intelligence holdings, to a complex, in-depth investigation to determine the nature and extent of an identified threat to Australia’s national security. Generally speaking, while any security assessment can be complex, the more complex cases fall predominantly within the visa security assessment caseload. Cases where the identity of an individual is hard to verify, or where it is difficult to obtain and assess the necessary background information about the individual (for example, where this information, if it exists, is held overseas, or where the reliability of information may be in question) can be particularly complex.

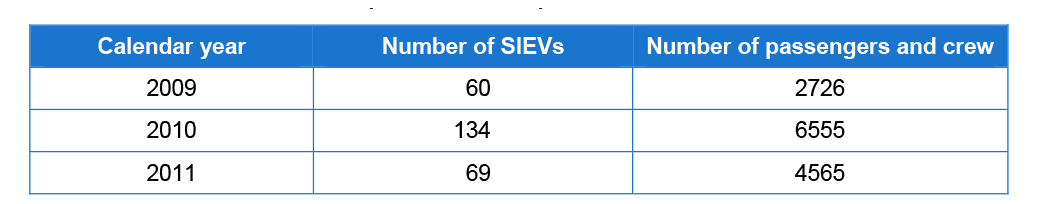

6. The Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs) component of the visa security assessment caseload is noteworthy for its complex nature. IMAs typically arrive without proper documentation and, when required, IMA-related security assessments generally entail extensive ASIO investigation. While the total number of completed security assessments has fluctuated, without a discernable trend, the complexity of the security assessment caseload has increased markedly in recent times, driven by the sharp increase in IMAs since 2009. In the six years prior to 2009, between four and seven suspected illegal entry vessels (SIEVs) arrived annually, carrying between 11 and 161 passengers and crew.8 Table S1 shows the number of SIEV arrivals, including their passengers and crew, from 2009 to 2011.

Table S1 SIEV arrivals to Australia (2009 to 2011)

Source: ASIO.

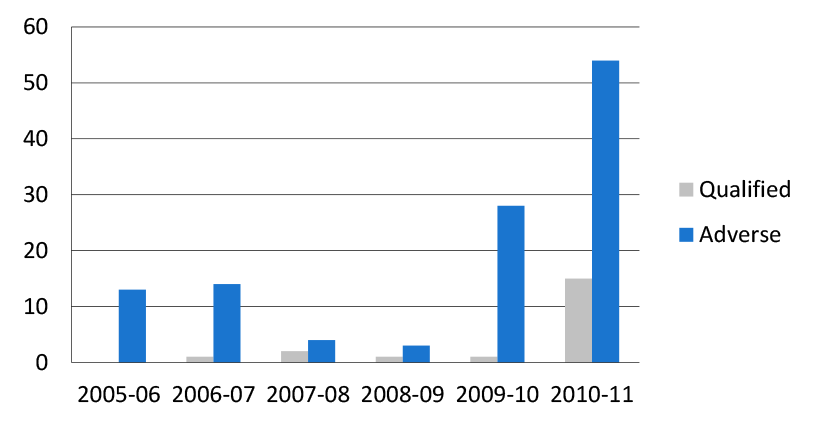

7. Upon making an assessment, ASIO may provide one of three types of advice for the client agency to take into account in relation to the individual concerned. The advice may be: non-prejudicial; or prejudicial—either qualified or adverse.9 Reflecting the increased complexity of the cases that are being processed, the number of prejudicial assessments has more than doubled over the last six years, but remains small overall (see Figure S1).

Figure S1 Prejudicial assessments 2005–06 to 2010–11 (number)10

Source: ANAO based on ASIO classified and unclassified Reports to Parliament.

8. Primarily, adverse security assessments have come from the visa security assessments stream (that includes the IMAs), and qualified security assessments from the personnel security assessments stream.

Public concerns about the security assessment process

9. Aspects of the security assessment process have attracted recent public comment. In particular, it has been noted that the time taken to complete certain security assessments, particularly for IMAs in detention, has affected the speed with which visa outcomes have been achieved for these individuals. In addition, the consequences of adverse assessments for these individuals have been the subject of public concerns. In certain IMA cases, the individual has been assessed by DIAC as meeting the definition of a ‘refugee’, but has also been given an adverse security assessment by ASIO. Such people are not eligible for the grant of a permanent Protection visa and, under current policy parameters, are presently ineligible for release into community detention. Unless an alternative country can be found for settlement, the individual can, in practice, remain in detention indefinitely.11

Audit objective, criteria and scope

10. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of ASIO’s arrangements for providing timely and soundly based security assessments of individuals to client agencies.

11. The audit assessed whether ASIO has:

- effective governance arrangements, including an appropriate risk management framework, to support the management of the security assessment process;

- a sound and timely security assessment process that is consistently applied and well supported by adequate resources; and

- appropriate client management arrangements to effectively process the security assessments of individuals.

12. The audit did not examine ASIO’s broader intelligence systems and assessment capabilities or the operations of Australian Government client agencies. The ANAO used a stratified random sample of 411 cases across six security assessment categories from 2009–10 and 2010–11 to assess compliance with procedures and to better understand issues affecting the processing of the caseload. The audit also took into account previous ANAO activity12 and other external reviews.13

13. In conducting this audit, the ANAO necessarily held discussions and reviewed documents which reflected matters that are sensitive from a national security and operational perspective (such as detailed information about ASIO’s sources, intelligence systems and methods, or resources). In line with previous practice, these matters are not discussed in detail in this report as this would not be in the public interest. It nevertheless reflects positively on public administration in Australia that the Auditor-General Act 1997 provides for performance audits of organisations such as ASIO, with appropriate reporting of their performance to the Parliament.

Overall Conclusion

14. The provision of security assessment advice of individuals to Australian Government client agencies is one of ASIO’s key responsibilities. For the past six years ASIO has finalised, on average, nearly 180 000 security assessments annually in relation to people who have applied for visas, Australian Government security clearances, access to sensitive air and maritime port areas, and health security checks. The environment within which ASIO provides this service is dynamic, with demand for security assessments, and the complexity of the caseload, fluctuating substantially. In seeking to meet the changing demand for particular security assessments, and to take into account government and client agencies’ policies and processing priorities, ASIO also applies an approach that gives precedence to Australia’s national security considerations.

15. ASIO security assessments can range from a basic check of personal details against intelligence holdings, to a complex, in-depth investigation to determine the nature and extent of an identified threat to Australia’s national security. Complex investigations can take a considerable time to complete. While any security assessment can be complex, the more complex cases fall predominantly within the visa security assessment caseload, particularly in the IMA component of this caseload.

16. ASIO’s capacity to respond to changes in its security assessment operating environment was challenged in 2009–10 and 2010–11 when demand for more complex assessments increased, in line with the increase in IMA cases. A backlog of security assessments ensued and the processing times of certain security assessments, particularly for IMAs who were in mandatory detention, attracted public comment and criticism. The ANAO’s sample included some cases with prolonged processing times (up to 918 days), particularly in the visa security assessments stream. For visa security assessment components that had informal time standards in place, around 51 per cent of sampled cases met expected timeframes.14 However, personnel security and counter-terrorism security assessments were generally processed more promptly—75 per cent of personnel security cases were processed within one day, and 90 per cent of counter-terrorism cases were processed within five days.

17. A range of factors have contributed to the time taken to process security assessments. The most influential factors identified by ASIO were the increase in the number and complexity of cases in the visa security assessments stream, and changes in Government policies and client agencies’ priorities, particularly DIAC. While some of these factors were environmental, and beyond ASIO’s direct control, ASIO has sought to inform Government and client agencies of the effects of particular policy approaches on the security assessment caseload. Areas of particular focus in this regard include decisions by Government and DIAC to suspend, and then subsequently, to prioritise elements of the IMA caseload. Assessment data shows that the number of pending cases has fallen from its peaks, as recent management initiatives, discussed below, have taken effect.

18. Within this context, the ANAO concluded that ASIO’s arrangements for providing security assessments of individuals to client agencies are robust and, broadly, effective. The agency has a sound governance framework in place, including strategic risk management arrangements that are updated regularly. There is an effective mechanism to report to the ASIO Executive and the Government on risks that affect security assessment processes, including most recently, the emerging area of risk arising from the rapidly increasing number of security checks for immigration community detention cases.15 However, at an operational level, there are some aspects of the security assessment regime that deserve further focus. These aspects limit assurance that the agency is making sound assessments that result in non-prejudicial advice, and that the recent initiatives implemented to reduce the IMA security assessment caseload are being managed sustainably. It is also important to address impediments to mutual accountability between ASIO and its client agencies, and that ASIO puts in place workforce planning strategies to respond to future changes in demand for security assessments.

Assurance that security assessments are soundly based

19. ASIO staff are well-trained and follow clearly defined procedures in conducting security assessments.16 All 411 cases examined by the ANAO complied fully with ASIO’s processes and procedures. In terms of the quality of the judgements made by ASIO assessors17, there are quality assurance processes in place for the small proportion of security assessments that result in prejudicial advice. However, for those assessments that result in non-prejudicial advice, the quality assurance processes are not as robust and vary across assessment categories. Given that a security assessment may contribute to a client agency’s decision to allow a person entry to Australia or access to sensitive information and/or locations, it would be prudent for ASIO to have in place a consistent quality assurance process to regularly validate, on a sample basis, its non-prejudicial security assessments.

Sustaining successful initiatives to improve IMA processing

20. ASIO and DIAC have worked together to streamline the IMA security assessments caseload. In particular, the introduction of a risk-based ‘triaging’ approach has successfully reduced the IMA backlog, and eased pressure on the overall security assessment function. However, the approach, which involves an ASIO team conducting an initial security check of IMA cases to decide whether the IMA will be referred to ASIO for a thorough security assessment, or sent back to DIAC for protection visa processing, could have been introduced in a more timely fashion. It would also be strengthened with documented guidance and a more robust IT supporting system.

Formalising relationships with key client agencies

21. ASIO has an ongoing working relationship with three key client agencies (DIAC, AGSVA, and AusCheck), and has in place a formal arrangement with one, AusCheck, which clearly articulates the responsibilities of both agencies. However, the absence of such arrangements with DIAC and AGSVA impedes the accountability of ASIO and the client agencies to each other in relation to the conduct of security assessments. Presently, there are no formally settled processing times, or service standards, for ASIO’s security assessment of non-complex cases, nor any agreed arrangements for ASIO to proactively provide to client agencies regular updates on the status of complex cases—particularly those that may have lengthy processing times. At the same time, the quality of the data provided by DIAC and AGSVA, upon which ASIO depends, has frequently been poor, and required re-work, which has delayed processing. Formalising arrangements with client agencies would provide a basis for better managing mutual expectations and responsibilities in relation to these matters.

Workforce planning strategies for the security assessment areas

22. To manage the allocation of staffing resources across the whole organisation, ASIO has developed a strategic workforce plan. However, given its agency-level focus, this plan does not address the needs of individual operational areas. The security assessment areas have specialised staffing requirements that have historically proved difficult to fill. At the time of the audit, these areas were significantly under-staffed—by some 30 per cent. The agency has sought to respond to staffing shortfalls through temporary measures such as internal staffing, re-allocations and overtime. However, going forward the agency’s capacity to respond, at an operational level, to future changes in the security assessment caseload would be strengthened by putting in place more long-term workforce planning strategies, including for a contingency or ‘surge’ capacity for this function.

Recommendations

23. Against this background, the ANAO has made four recommendations aimed at strengthening the effectiveness of ASIO’s arrangements for providing timely and soundly based security assessments of individuals to client agencies. The recommendations relate to: implementing quality assurance processes for non-prejudicial assessments; sustaining the risk-based ‘triaging’ initiative for IMA cases; formalising agency relationships; and strengthening workforce planning strategies for the security assessment areas.

Key Findings by Chapter

Governance arrangements (Chapter 2)

24. Changes in demand for security assessments, particularly as a consequence of the sharp increase in IMAs, have had profound impacts on a number of government agencies, including ASIO. Such a dynamic environment places a premium on responsive and adaptive governance and management arrangements. The ANAO observed that:

- ASIO’s governance framework, including risk management, is robust;

- roles and responsibilities of the areas within the agency that conduct, manage and issue security assessments have been clearly documented and are well understood by relevant staff; and

- there is clear and timely reporting to the Executive and to government, where necessary, on emerging risks that affect security assessment processes and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

25. Operationally, there is room for improvement in two key areas: client agency relationship management and workforce planning.

26. ASIO has a current Memorandum of Understanding with AusCheck. However, there are no formal arrangements in place between ASIO and its other key client agencies, DIAC and AGSVA. ASIO has expressed a general reluctance to be ‘tied-down’ to specific service standards or timeframes with DIAC and AGSVA, given the complexities surrounding particular security assessments that can prolong the process.

27. The data provided by DIAC and AGSVA to ASIO has frequently been incomplete or of poor quality. For example, in relation to the ANAO’s sample, 38 per cent of permanent visa referrals and 30 per cent of temporary visa referrals had incomplete mandatory information, and/or data quality issues, which required the case to be sent back to DIAC. The time taken to provide the complete information was lengthy in some cases. Similarly, ASIO advised that there have been referrals returned to AGSVA, with error codes that relate to missing mandatory information.

28. In addition, ASIO is not able to provide its client agencies with the underlying reasons as to why some complex cases are taking longer to process or specific aspects of a security assessment investigation, as the provision of substantive security information on an individual could constitute ‘security advice’ under the ASIO Act. Such advice is only given at the conclusion of a security assessment. These issues should be taken into account in any steps taken to formalise arrangements between ASIO and its client agencies.

29. To manage the allocation of staffing resources across the whole organisation, ASIO has developed a strategic workforce plan, which details, among other things: a scan of the current internal and external workforce environment, the challenges facing ASIO over the coming years, and ASIO’s approach to these challenges. The strategic workforce plan is high level and, given its focus, does not address the needs of individual divisions or branches. While systemic workforce shortages have been raised corporately by the security assessment branches, there is no long-term strategy in place to address these issues or to develop a contingency, or surge capacity, to respond to future changes in demand for security assessments. In practice, ASIO has found it difficult to recruit assessors to perform work on security assessments. The staffing complement of the security assessment areas has been consistently below authorised levels—in early 2012 the shortfall was around 30 per cent.

Conduct of security assessments (Chapter 3)

30. ASIO’s security assessments range from relatively straightforward checks of names against data holdings to more complex investigations where an in-depth knowledge of an applicant (for a visa, for example) is obtained, and this knowledge is used to make more informed investigations, evaluations and determinations.

31. The ANAO examined a sample of 411 cases drawn from six security assessment categories.18 The results of ANAO’s analysis are very positive: all 411 cases complied with the agency’s defined processes and procedures for security assessments.

32. The ANAO did not seek to ‘second guess’ the judgements arrived at by ASIO officers conducting particular security assessments, however, the agency’s processes to assure itself as to the quality of assessments were examined.19 Quality assurance arrangements vary across ASIO’s security assessment categories. There is a robust, quality assurance system in place for all security assessments that have been issued with prejudicial advice, but quality assurance for security assessments that have been issued with non-prejudicial advice is inconsistent. For example, there is a quality assurance process to validate security assessments for IMAs, personnel security and counter-terrorism cases. However, for other visa security assessments, there is no process in place.

The Security Triaging Framework

33. Prior to April 2011, all IMAs that arrived in Australia were subject to ASIO security assessments that involved a full investigative process. Under a parallel processing arrangement, ASIO conducted its investigations of IMAs at the same time as DIAC was determining the IMA’s claims to refugee status. The approach proved difficult to sustain when the number of IMAs arriving increased so markedly.

34. In late 2010, the Government made two significant decisions to streamline the security assessment process. The first was that DIAC would only refer IMAs to ASIO for security assessment who had already been accorded refugee status, or whose refugee claims could be accepted by DIAC.

35. The second decision agreed by the Government in late 2010 was to streamline the security assessment process for IMAs, to further reduce the number of IMA cases referred to ASIO for assessment. The revised risk based assessment is more closely aligned to the process applied to every other visa applicant. This process is known as the Security Triaging Framework (STF), and involves an ASIO triaging team processing the IMA referrals from DIAC that have been confirmed as meeting the definition of a ‘refugee’20 and may require a security assessment. The triaging team conducts an initial security check, based on ASIO’s security indicators, and then decides whether the IMA will be referred to ASIO for a thorough security assessment, or sent back to DIAC for protection visa processing. The STF was implemented in April 2011, following riots at the Christmas Island detention centre the previous month.

36. While the Government and DIAC’s responses to the STF have been positive, and security assessment and related visa backlogs within both agencies have been reduced, the ANAO identified administrative weaknesses in the triaging process. There are no documented standard operating procedures for the STF function, and the team is heavily reliant on the team leader’s expertise. Further, the IT tools used by the triaging team are very basic and potentially unstable. The triaging team uses Excel spreadsheets received from DIAC, which are manually ‘cleaned’, copied and pasted to produce various reports prior to triaging. There is a clear risk of losing important data and introducing, or retaining, errors in such a manual process. Consideration should be given, on a cost-benefit basis, to enhancing the supporting IT tools for the STF initiative.

An emerging area of risk: security checks for community detention cases

37. In October 2010, the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship announced the expansion of the existing ‘residence determination’ program (also known as community detention) to children and vulnerable family groups. Community-based detention arrangements were introduced in June 2005 to enable people to reside in the community without needing to be escorted. Only the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship can approve residence determination for people in immigration detention.21

38. DIAC and ASIO agreed to implement a streamlined security check for IMAs identified for residence determination, but who had not yet received a full security assessment in relation to the granting of a visa. At the time of the announcement, it was expected that around 900 IMAs would be moved into community detention between October/November 2010 and June 2011. Of these 900, ASIO expected to be referred around 200 cases for streamlined security checks, based on ASIO’s understanding that these individuals were low-risk (adults drawn from a cohort comprising vulnerable family groups and unaccompanied minors). In an eight month period, the cumulative number of security checks increased by almost 500 per cent, from 644 cases in April 2011 to 2858 cases in December 2011. The trend is likely to continue as DIAC has now requested that all IMAs be referred to ASIO for community detention security assessments rather than the initial, smaller, low-risk cohort.

39. Initially, ASIO applied specific security indicator thresholds to its community detention assessments that were consistent with the overall low-risk nature of the expected caseload. In November 2011, ASIO appropriately revised its security assessment thresholds for community detention in light of the changing risk profile of the community detention cohort. The same threshold now applies across all IMA security assessments. This means that ASIO will issue an adverse security assessment in relation to community detention if the IMA was assessed as representing a direct or indirect risk to security.

40. ASIO advised that there have been between five and 10 cases where IMAs have been referred to ASIO for community detention security assessments despite ASIO having already issued an adverse security assessment or qualified security assessment in relation to a grant of a visa. Such persons are presently not eligible for release into community detention.

Workload and performance trends for security assessments (Chapter 4)

41. With the increase in IMAs stretching the processing capacity of ASIO, turnaround times for processing security assessments exceeded expected timeframes across all security assessment categories that have specified time standards. Backlogs ensued as the demand for security assessments exceeded the output capacity of ASIO staff.

42. In its public reporting, ASIO has only ever reported on the number of assessments completed. Such output measures do not give a complete picture of trends in the assessment caseload. In particular, trend data on referrals received from client agencies, cases on-hand (‘pending’) and processing times for key security assessment categories would provide greater insight into the management of this important function.

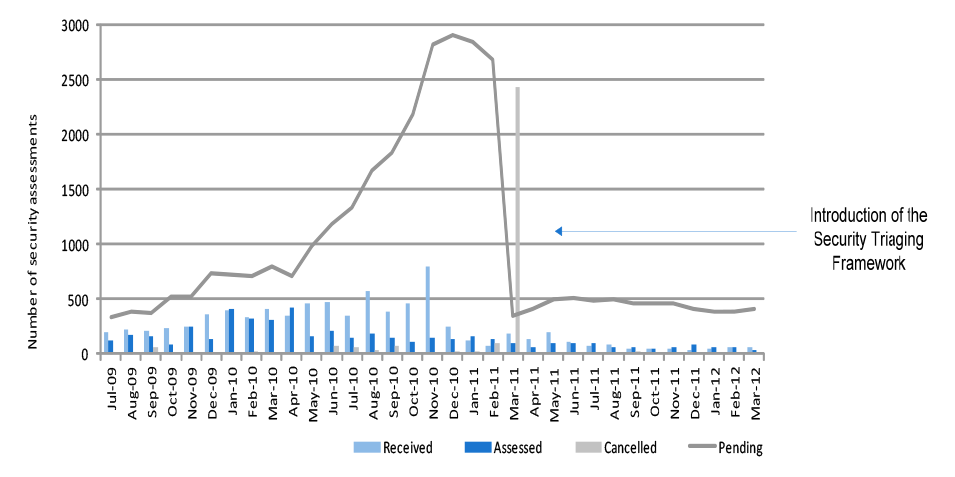

43. Since 2009, the trend in referrals and pending cases across the security assessment categories followed a consistent pattern, albeit with differing case numbers over specific time periods. In each category, assessment output remained fairly constant as referrals, and consequently the number of pending cases, grew rapidly over a period of months. The backlogs fell as management initiatives brought the caseload under control. For the IMA caseload in particular, the substantial decline of referrals in the first half of 2011 reflects the new intelligence-led, risk based approach being taken, including the STF (see Figure S 2).

Figure S2 IMA caseload trends (June 2009 to March 2012)

Source: ANAO analysis of ASIO data.

44. The aspect of ASIO’s security assessment process that has attracted the most public comment and criticism in recent years is its timeliness. Given the importance of ASIO security assessments in progressing client agency processes, it would be reasonable to expect that ASIO and its client agencies would have formally settled on service standards or timeframes for the provision of security assessments. However, the ANAO found that in relation to:

- visa security assessments: no time standards have been formally settled between ASIO and DIAC, although informal standards have been set for some visa security assessment types;22

- personnel security assessments: there are also no time standards, formal or informal, settled between ASIO and AGSVA; however,

- counter-terrorism security assessments: time standards have been formally set between ASIO and AusCheck in their Memorandum of Understanding. In most cases, identities of these applicants are known and easily verified.

The absence of any formal arrangement on reasonable processing times limits the accountability between ASIO and its key client agencies and should be a consideration when developing formal arrangements with these agencies.

45. The ANAO’s analysis of the 411 case sample showed that, for security assessment categories that had specified time standards in place, 34 per cent of cases exceeded expected timeframes. In particular, 71 per cent of security assessments for protection visas exceeded the informally agreed timeframes. Similarly, the increase in the volume and complexities of IMAs, compounded by internal staffing issues, caused prolonged processing of IMAs. These caseloads were also particularly affected by changes in Government policies and/or DIAC processing priorities. Given the complexity of such cases, it is impractical to specify an expected processing time—however, it should be possible for arrangements to be put in place for ASIO to proactively provide regular updates to client agencies on the status of such complex cases without prematurely disclosing information that could constitute security advice.

46. Conversely, for permanent visas and temporary visa cases, 65 per cent and 58 per cent of cases sampled were processed within the informally agreed timeframes. Seventy-five per cent of personnel security assessments were processed within one day, although no processing standard has been agreed for this assessment type. Ninety per cent of counter-terrorism cases were processed within the formally agreed timeframe of five days.

47. A number of factors can affect the length of time it takes to process security assessments. Some key factors identified by the ANAO from its sample include:

- quality of information/data received from referring agencies;

- the increase in the number and complexity of cases;

- changes in government policies and client agencies’ priorities (such as suspending processing of certain groups and prioritising the processing of others); and

- staffing levels and backlogs.

ASIO management particularly highlighted the combined operational impact of changes in Government policies and client agency processing priorities in the visa security assessment stream.

Summary of agency response

48. The full proposed report was provided to ASIO and extracts of the proposed report were also provided to DIAC, AGSVA and Auscheck for commentASIO’s full response is at Appendix 1. Its summary response is as follows: ASIO welcomes the findings of the audit report, in particular the assessment that ASIO’s arrangements for providing security assessments of individuals are robust and effective. ASIO agrees with the recommendations of the report, and notes the following:

- ASIO regularly assesses staffing levels across the Organisation in the context of its Strategic Risk Management Framework and intelligence priorities.

- ASIO will continue to progress MoUs with client agencies, noting that unlike processing matters, timeframes for investigations must necessarily be indicative only.

- In relation to regular updates, ASIO will continue to liaise with client agencies as required on these cases.

- ASIO notes that in relation to IMA cases, quality assurance procedures are already in place to all non prejudicial assessments.

- ASIO notes that documented standard operating procedures exist for staff undertaking triaging in relation to IMA cases.

Footnotes

[1] <www.asio.gov.au/About-ASIO/Overview.html> [Accessed 30 January 2012].

[2] Any person applying for a visa to travel to, or remain in, Australia may have the application referred by DIAC to ASIO for a security assessment. In most visa categories, a visa may not be issued where ASIO determines the applicant to be a risk to ‘security’, as defined in the ASIO Act. ASIO’s security intelligence investigations will from time to time determine that the holder of a valid visa presents a risk to Australia’s security. In these circumstances, ASIO may make an adverse assessment and the visa will be cancelled.

[3] AGSVA undertakes security clearances of employees, prospective employees or contractors on behalf of most Australian Government agencies. ASIO provides a security assessment on applicants to determine whether they pose a national security threat if allowed to access classified material.

[4] AusCheck coordinates background checks and assesses the overall suitability of persons seeking identity cards that enable access to sensitive air and maritime port areas—Aviation Security Identification Cards (ASIC) and Maritime Security Identification Cards (MSIC). ASIO may recommend against issuing an ASIC or MSIC on the basis of counter terrorism security concerns.

[5] ASIO also provides (via the AFP) counter-terrorism security assessments for access to sensitive or dangerous goods such as explosives and radiological material (for example, ammonium nitrate, explosives and access to the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation), and to support accreditation for special events (such as the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and the Commonwealth Games).

[6] ASIO’s security assessments may also apply to certain applications for Australian citizenship (citizenship may not be approved where ASIO has made an adverse or qualified security assessment), and in relation to certain passports (ASIO may request on security grounds the cancellation of an Australian passport, or that an application for an Australian passport is declined. An adverse ASIO security assessment can also be grounds for the Foreign Minister to demand the surrender of a foreign travel document, such as a passport).

[7] See ANAO Report No.39 2010–11 Management of the Aviation and Maritime Security Identification Card Schemes.

[8] ASIO advised that not all 161 SIEV arrivals were referred to ASIO for security assessment. Crew were not referred, and at that time only adult IMAs who met the referral criteria (minority of IMAs) were referred for security assessment.

[9] Non prejudicial advice means that ASIO has no security related concerns about the action proposed in respect of the individual concerned. Qualified advice generally means that ASIO has identified information relevant to security, but is not making a recommendation in relation to the proposed action. Adverse advice means that ASIO recommends that ‘prescribed administrative action’ be taken (such as: declining an application for a visa, or personnel security clearance, or for ASIC or MSIC).

[10] Excludes ASIO security assessments relating to passport cancellations.

[11] ASIO noted that options for return; consistent with Australia’s international protection obligations (that is when it is safe to do so); review of protection obligations; and third party resettlement, may be available to government. However, these options are either not practical or have not been achievable to date.

[12] For example: ANAO Audit Reports No.39 2010–11, Management of the Aviation and Maritime Security Identification Card Schemes; No.4 2010–11, National Security Hotline; and, No.35 2008–09, Management of the Movement Alert List. The ANAO also has a long-standing program of auditing visa related programs that include the following: Management of Student Visas (Audit Report No. 46 2010–11); Visa Management: Working Holiday Makers (Audit Report No. 7 2006–07) and Onshore Compliance—Visa Overstayers and Non-Citizens Working Illegally (Audit Report No. 2 2004–05).

[13] For example, the Final Report of the Joint Select Committee on Australia’s Immigration Detention Network (March 2012), canvassed issues to do with security assessments, including the length of time taken to complete security assessments; the need to detain people for the duration of the assessments; and adverse assessments and the lack of opportunity for review. The report of the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security Inquiry into allegations of inappropriate vetting practices by the Defence Security Authority and related matters (February 2012), also involved aspects of ASIO’s personnel security assessments.

[14] ASIO has informally set time standards with DIAC for the security assessment of applicants for visas in the: temporary and permanent residence, onshore protection, and offshore refugee and humanitarian visa classes. The standards range from one to six months, depending on the visa class.

[15] On 1 November 2011, the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security announced that she had commenced an inquiry into community detention security assessments and related matters.

[16] The procedures followed by ASIO are classified. The ANAO based its analysis on the application of these procedures.

[17] The ANAO did not seek to ‘second guess’ the judgements arrived at by ASIO officers conducting particular security assessments.

[18] The six categories examined were: temporary visas, permanent residence, onshore protection and offshore refugee/humanitarian, IMAs, personnel security and counter-terrorism security assessments.

[19] The ANAO also notes that the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security provides independent assurance for the Prime Minister, senior ministers and Parliament as to whether Australia’s intelligence and security agencies act legally and with propriety by inspecting, inquiring into and reporting on their activities (see <http://www.igis.gov.au/> accessed 26 April 2012).

[20] As a member of the international community, Australia shares responsibility for protecting refugees and resolving refugee situations. The 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees states that a person is owed protection if that person is outside their country and is unable or unwilling to go back because they have a well-founded fear that they will be persecuted because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group.

[21] The Minister must consider what is in the public’s best interest when making, varying or revoking a residence determination under the Migration Act 1958. Community-based detention arrangements do not give a person any lawful status in Australia, nor do they confer the rights and entitlements of a person who holds a visa (for example, the right to study or work). The person remains, administratively, detained under migration law while living in the community. Conditions include a mandatory requirement to report regularly and reside at the address specified by the Minister.

[22] ASIO has informal agreement with DIAC on time standards for the security assessment of applicants for visas in the: temporary and permanent residence, onshore protection, and offshore refugee and humanitarian visa classes.