Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Second Follow-up Audit into the Australian Electoral Commission's Preparation for and Conduct of Federal Elections

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the Australian Electoral Commission’s implementation of those recommendations made in Report No. 28 2009–10 relating to:

- a more strategic approach to election workforce planning;

- the suitability and accessibility of polling booths and fresh scrutiny premises; and

- the transport and storage of completed ballot papers, in respect to matters not fully addressed in ANAO Audit Report No.31 2013–14.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Electoral Commission’s (AEC) responsibilities include conducting Federal elections in accordance with the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The AEC operates through a three tier structure of a national office in Canberra, state and territory offices, and divisional offices responsible for electoral administration across Australia’s 150 electoral divisions. The AEC employed nearly 850 ongoing staff as at 30 June 2013. For each Federal election, the AEC recruits a large temporary workforce and operates a significant number of polling places.

2. In April 2010, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) tabled a performance audit report on the AEC’s preparation for and conduct of the 2007 Federal election.1 ANAO made nine recommendations, including four relating to the AEC improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll. Other recommendations included the AEC improving its workforce planning, and enhancing the accessibility and suitability of polling booths and scrutiny centres. ANAO also recommended that the AEC identify and assess options that would provide greater physical security over the transport and security of completed ballot papers.

3. In this latter respect, during the conduct of the 7 September 2013 Federal election, 1370 Western Australian (WA) Senate ballot papers were lost. This situation led to:

- the voiding of the election of six Senators for WA and a new election for WA Senators being held on 5 April 2014, with a different political outcome when compared with the counting of votes lodged at the September 2013 election; and

- the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM or the Committee) writing to the Auditor-General requesting performance audit activity relating to the AEC’s implementation of earlier recommendations made by the ANAO.

Audit objective and scope

4. In view of the importance of the AEC’s functions and responsibilities and the interest shown by JSCEM in the AEC’s implementation of the ANAO’s earlier recommendations, and to address the matters raised by the Committee in a timely manner, the Auditor-General decided to conduct three related performance audits.

5. The report of the first audit was tabled in May 2014 (ANAO Audit Report No.31 2013–14). Its objective was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the recommendation made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 relating to physical security over the transport and storage of completed ballot papers. The follow-up of implementation of that recommendation was prioritised as it was an area of particular interest to the Committee.

6. The objective of the second audit, which is the subject of this report, was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the Australian Electoral Commission’s implementation of those recommendations made in Report No. 28 2009–10 relating to:

- a more strategic approach to election workforce planning, with a particular focus on the selection, recruitment, training and performance evaluation of election officials (Recommendation Nos. 5 and 6);

- the suitability and accessibility of polling booths and fresh scrutiny premises (Recommendation No. 7); and

- the transport and storage of completed ballot papers (Recommendation No. 8(b)), in respect to matters not fully addressed in ANAO Audit Report No.31 2013–14. Specifically, compliance with new policies and procedures introduced to address the Keelty report2 recommendations for the WA Senate election 2014.

7. A third audit of the AEC’s implementation of recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 has been included in the ANAO’s 2014–15 forward work program. The third audit is expected to focus on the recommendations relating to the AEC improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll.

Overall conclusion

8. Each Federal election is a complex logistical event, with a wide range of preparation tasks required to be completed before polling day. For the 2013 Federal election, this included the AEC employing 68 834 people to fill 72 224 election roles.3 In addition, the AEC established 7697 static polling places for people to vote in person, on election day, and arranged scrutiny centres for vote counting across the 150 divisions, as well as central Senate scrutiny centres in each state.

9. ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 concluded that the AEC’s planning and preparation for the 2007 election was effective, but there was evidence that elements of the existing approaches may be reaching their limit in terms of cost-effectiveness. This led ANAO to make three multi-part recommendations (Recommendation Nos. 5, 6 and 74) in relation to election workforce planning, the selection, recruitment, training and performance assessment of election officials, and the suitability and accessibility of polling and scrutiny premises. By March 2012, the AEC had informed its audit committee that implementation of each recommendation had been completed.

10. Notwithstanding the advice provided to its audit committee, the AEC has not adequately and effectively implemented each element of Recommendation Nos. 5, 6 and 7 from ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10. Some improvement is evident in relation to aspects of those recommendations, in particular more timely recruitment of election officials, and improved approaches to their training. However:

- there was little change evident between the 2007 and 2013 elections in how the AEC selects premises for voting and vote counting purposes;

- the AEC has yet to develop a workforce plan to assist with addressing the challenges associated with retaining, recruiting and training a large number of temporary election officials, and responding to continuing high levels of temporary staff turnover between elections;

- records of the recruitment of polling place staff for the 2013 election demonstrate that 34 per cent of people appointed to those roles had not been assessed as to their suitability;

- it is relatively common for people employed as election officials to not complete some or all of the assigned training; and

- performance assessment ratings have not been recorded for all election officials at either the 2010 or 2013 elections (compliance with this requirement was 87 per cent and 80 per cent respectively).

11. ANAO has made a further five recommendations in relation to these matters. The first two recommendations are particularly important. They relate to improvements to existing approaches to the provision of polling and scrutiny premises, and the development of a temporary election workforce plan. Their implementation can be expected to improve the effectiveness of the AEC’s conduct of future elections as well as deliver cost savings (as a result of needing to recruit and train fewer staff for static polling places). In turn, these savings could contribute significantly to the costs of implementing other reforms proposed following the 2013 election.5

12. Similar to the messages in ANAO Audit Report No.31 tabled earlier in 20146, to protect the integrity of Australia’s electoral system and rebuild confidence in the AEC, it is important that the AEC’s governance arrangements emphasise continuous improvement and provide assurance that the action taken in response to agreed recommendations effectively addresses the matters that lead to recommendations being made. In this context, although lacking rigour in certain respects, the arrangements adopted to monitor implementation of interim measures to respond to the Keelty report, and assess their effectiveness, demonstrate a greater commitment to organisational learning and improvement than has previously been evident. The challenge for the AEC is to sustain and build on this greater commitment so as to take advantage of the opportunities that are evident to re-engineer long-standing election planning and preparation activities which can be expected to provide more efficient and cost-effective services to the electorate.

13. ANAO plans to undertake a follow-up audit following the next Federal election to examine the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the five recommendations made in this audit report, as well as the three recommendations included in Audit Report No.31 2013–14.7

Key findings by chapter

Polling and Scrutiny Premises (Chapter 2)

14. The significant majority of Australians who vote do so in person either at a Pre-Poll Voting Centre (PPVC) prior to election day or on the Saturday of the election at a static polling place. At the 2013 election more than 91 per cent of the 14.7 million votes counted were received at either a PPVC (18.1 per cent) or static polling place (72.9 per cent). The provision of these voting facilities involved a considerable logistics workload for the AEC at divisional office level including:

- inspecting potential premises in advance of the election;

- making arrangements to access the premises and setting them up for polling purposes; and

- recruiting and training the temporary employees required to staff the static polling place premises and PPVCs.

15. ANAO’s earlier audit of the 2007 election concluded that there was evidence that elements of existing election planning and preparation approaches may be reaching their limit in terms of cost-effectiveness. One area where this was the case related to the approach taken to polling and scrutiny premises, with one of ANAO’s recommendations suggesting various ways the AEC could improve the suitability and accessibility of polling and scrutiny premises.

16. Notwithstanding that the AEC considered it had implemented the earlier ANAO recommendation it had agreed to, there was little change evident in how the AEC went about arranging premises for voting and vote counting purposes at the 2013 election. Of particular note in this respect was that unless the premises used at the 2010 Federal election were not available for hire, the AEC has continued its practice of re-using the same premises at successive elections irrespective of whether those premises meet the needs of voters and/or election officials, and with little consideration given to the availability of more suitable premises (including community facilities funded by the Australian Government). As a result, for example, a significant proportion of polling place premises continue, on the basis of the AEC’s own assessments, to not be fully accessible to voters.

17. In addition, while the AEC has advised JSCEM that the trend towards early voting8 needs to be assimilated as a critical element of the environment in which elections are delivered, the organisation has been quite inconsistent in its response to this trend. For example, the AEC has not consistently reflected this trend in its approach to securing polling premises. Specifically, while the number of PPVCs was significantly increased following the 2007 election reflecting the increasing popularity of early voting, there was no commensurate action to reduce the number of static polling place premises. Rather, the AEC has provided some 7700 static polling places at each of the last four elections, when it could have effectively serviced the declining proportion of the electorate that vote on Saturdays by employing significantly fewer polling place premises, with flow-on benefits in terms of reducing the number of polling place staff that need to be recruited and trained.9

18. In addition, the AEC’s staffing of polling premises has not reflected the continuing decline in the extent to which Australian’s vote on election Saturday. At the 2010 election, static polling places received 10.8 million votes, or 82 per cent of all votes. For the 2013 election, the AEC’s staffing of polling places was based on an aggregate estimate of these places receiving 11.47 million votes, an increase of nearly 630 000. This suggests that the AEC expected around 82 per cent of the population would continue to vote on the Saturday, which was at odds with a continuing trend towards early voting. As it eventuated, the AEC over-estimated by 1.39 million (13.8 per cent) the number of votes that would be received at static polling places, with fewer than 73 per cent of total votes counted being received at a static polling place. The AEC in applying its existing staffing allocation model, significantly over-estimated staffing requirements in static polling places nation-wide.10

Workforce Planning (Chapter 3)

19. For each Federal election, the AEC employs a large temporary workforce to assist with the preparation for, and conduct of, voting and vote scrutiny. Over the course of the last decade, agencies have been encouraged to adopt more disciplined approaches to workforce planning so as to ensure they have the capability to deliver on organisational objectives now and in the future. In this context, ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 recommended that the AEC improve its workforce planning by critically examining its future election workforce needs and composition. The AEC had advised its audit committee that a workforce plan would be developed to implement the ANAO recommendation, but implementation action for this recommendation was recorded as having been completed without such a plan being developed.

20. The importance of a disciplined approach to workforce planning is evident from the size of the election workforce, with 68 834 people employed to fill 72 224 roles for the 2013 election.11 In addition, the AEC experiences high turnover in temporary staff between elections.

21. Rather than develop a workforce plan for the temporary election workforce as the AEC had initially proposed in response to the recommendation, it has continued to focus on operational workforce matters, particularly in relation to the recruitment and training of election officials. This has resulted in the AEC missing opportunities, for example, to:

- adopt more efficient resourcing approaches in relation to static polling places that could have significantly reduced the number of election officials that needed to be recruited and trained, as outlined at paragraph 17; and

- address risks to the delivery of future elections. In this respect, the composition of the AEC’s 2013 election workforce was largely unchanged from the 2007 election, including an ageing workforce (an issue identified in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 as worthy of management attention). Notwithstanding that two elections have since been held, the AEC’s submission to the JSCEM inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 election did not identify that strategies had already been developed but, rather:

… an aging workforce is an issue the AEC may need to address in coming years as part of workforce planning.

Recruiting Election Officials (Chapter 4)

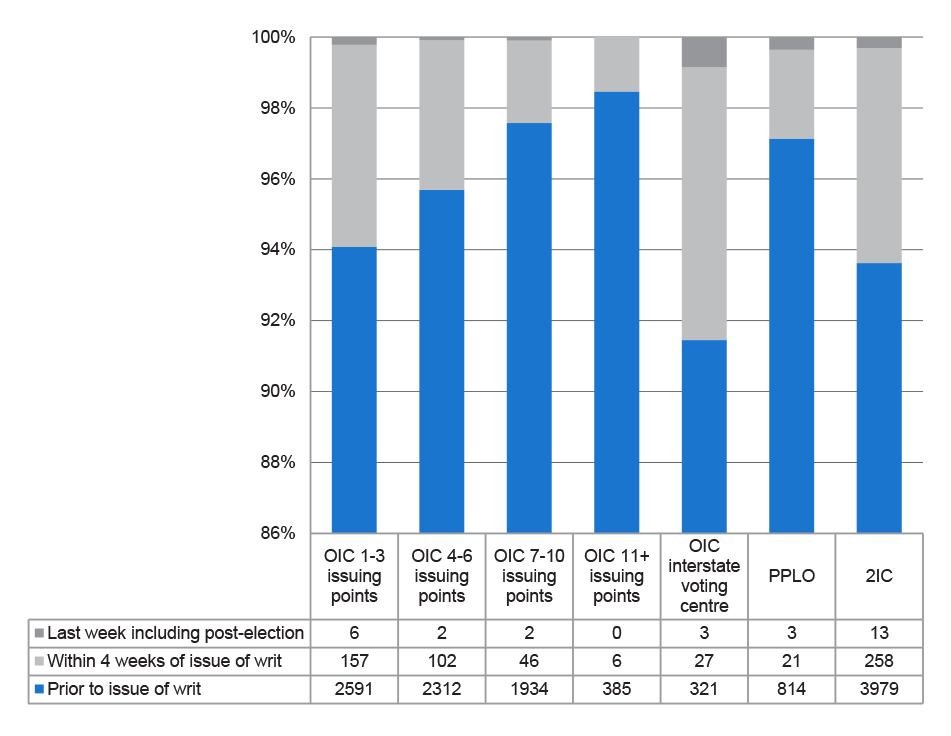

22. Late recruitment, particularly of senior election officials, was a significant issue during the 2007 election. The AEC’s recruitment of temporary employees to work on polling day for the 2013 election was significantly more timely. Of note was that the AEC has implemented a continuous recruitment model, supplemented by targeted recruitment activities to engage with selected sections of the community. These approaches assisted the AEC to fill more than 78 per cent of election day roles with people registered for temporary employment with the AEC prior to the issuing of the writ.

23. The AEC was particularly successful at prioritising the recruitment of senior election officials. In this respect, 95 per cent of polling place officers-in-charge (OICs) were recruited prior to the 2013 election being announced, and almost all of these roles had been filled within four weeks of the writ being issued.

24. A key aspect of the AEC’s recruitment policies and procedures is that persons interested in working at an election be assessed as to their suitability. In addition to being consistent with recruitment based on the principle of merit, only appointing those people that the AEC has assessed as suitable for employment, in combination with the completion of appropriate training and the provision of adequate supervision, can be expected to increase the likelihood that officials will satisfactorily undertake their assigned role. However, for the 2013 election, 34 per cent of election roles were filled by people where there was no record of them having been assessed for suitability.

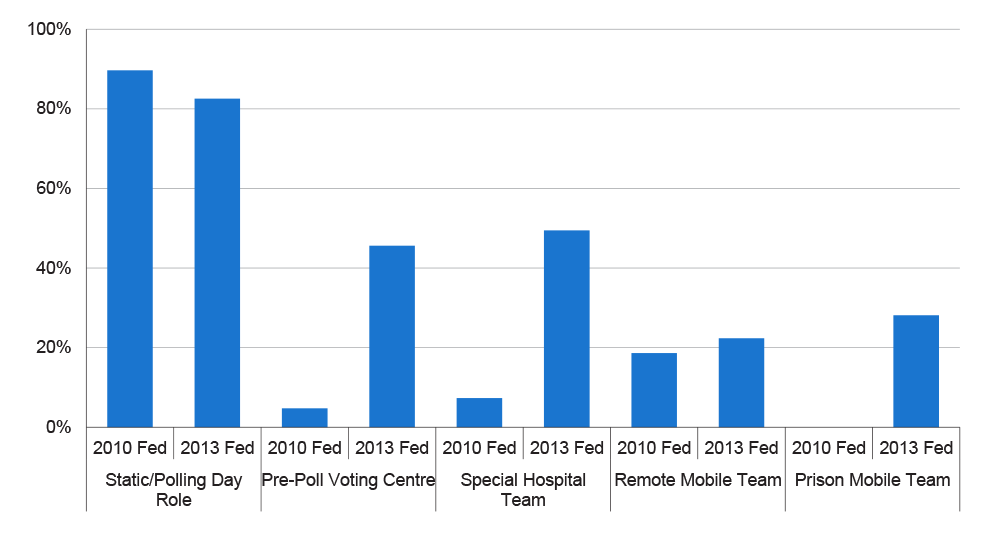

25. The retention of people with past election experience is valuable in maintaining the skills base of the election workforce, and is particularly important for senior roles. In this context, ANAO’s survey of a sample of the AEC’s temporary election workforce for the 2013 election identified that overall satisfaction with the AEC is high, with 93 per cent of respondents indicating they would be prepared to work for the AEC at future election events.12 However, indications of high satisfaction with the AEC have not been reflected in low turnover between election events, with only a slight improvement between the 2010 and 2013 elections. There would be benefit in the AEC seeking to understand the reasons for the continuing high turnover in the temporary election workforce and developing strategies that will enable it to reduce turnover at future elections (with particular emphasis given to more senior polling roles) in the context of a temporary election workforce plan.

Training Election Officials (Chapter 5)

26. The training of people employed as election officials is a key part of the preparation for a Federal election. The AEC has established minimum training requirements, with a particular emphasis on more senior polling roles, including the OIC for each polling place. The AEC’s policy position is that election officials must complete the required training if they are to have the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively perform their allocated role. There are three main training methods employed by the AEC.

Election Procedures Handbook

27. The AEC produces nine roles based versions of the Election Procedures Handbook, that are provided to all election officials, after they accept an offer of temporary employment. It covers administrative and operational requirements, emergency and security procedures, workplace health and safety requirements, and other general information. Of the more than 4500 temporary employees who responded to an ANAO survey, 95 per cent recalled receiving a copy of the Handbook, with most respondents receiving the Handbook between two and four weeks in advance of the election. Further, 93 per cent of respondents were either very satisfied or satisfied that the Handbook helped them to prepare to perform their assigned role.

Home-based training

28. The implementation of online modalities for the delivery of home-based training since the 2010 election has enhanced the AEC’s ability to monitor the completion of this aspect of training. For the 2013 election, people filling 32 855 election roles were required to complete home-based training.

29. ANAO analysis of the AEC data revealed that online home-based training was completed by people filling 80 per cent of election roles with a training requirement. Of the remaining 20 per cent, 3 per cent had not been assigned to undertake the training, 5 per cent had only partially completed the training and 12 per cent had not completed the training.

30. Further, in relation to the important senior role of election day OIC, only 82.5 per cent of roles were filled by people who had completed the required home-based training. As a consequence, more than 1.2 million votes were received at 1141 static polling places for the 2013 election where the AEC had no central records of the responsible polling place OIC having completed all elements of the required home-based training.

Face-to-face training

31. Face-to-face training sessions are conducted for senior polling place roles and aim to provide additional information, particularly about areas of high risk or changes in procedure. The face-to-face training sessions are mostly delivered by the divisional returning officers (DROs) and can be customised to meet local training needs. Of the 2583 survey respondents who informed ANAO that they completed the face-to-face training, 82 per cent were satisfied with the training. While still a generally positive result, the result was a marked reduction when compared to the level of satisfaction with the AEC’s other training modalities. In comparison to the AEC’s other training, survey respondents did not feel that the face-to-face training as clearly explained AEC election procedures and requirements, or that the training gave them a good understanding of their role and responsibilities.

32. Participation in face-to-face training is mandatory for senior roles, but prior to the Griffith by-election in early 2014, records of attendance were held only by the divisions. In light of the Keelty report, the AEC implemented new business processes whereby completed records of attendance were required to be forwarded to the AEC National Office. This information has been subsequently entered into the Election Training System and transferred to a locally developed reporting tool. The training assurance process was time consuming and labour intensive and, accordingly, is unlikely to be feasible for a general election. Further, the approaches were not fully effective in ensuring all mandatory training requirements were met. In this respect, ANAO analysis of training completion data was that nine per cent of officials for the WA Senate election did not complete all of the required training.

33. More broadly, in responding to various matters that arose concerning the conduct of the 2013 election, the AEC has emphasised the importance of improving its training of election officials. The AEC has also recently advised JSCEM that it has embarked on the largest review of learning and development in its history, covering both the content and delivery of training. This work is important, but as indicated by the key findings of this audit, it is also important that the AEC give greater attention to being satisfied that the people engaged to fill election roles complete the training that is expected of them.

Performance Assessment (Chapter 6)

34. A performance rating process for election officials was introduced by the AEC in 1997 with people to be assessed as meeting the required standard, being below it, or above it. The intention of the rating system was to measure the overall performance of election officials, especially those in key roles, with a view to assessing the effectiveness of training and ensuring that offers of future employment are directed to people with proven records of performance.

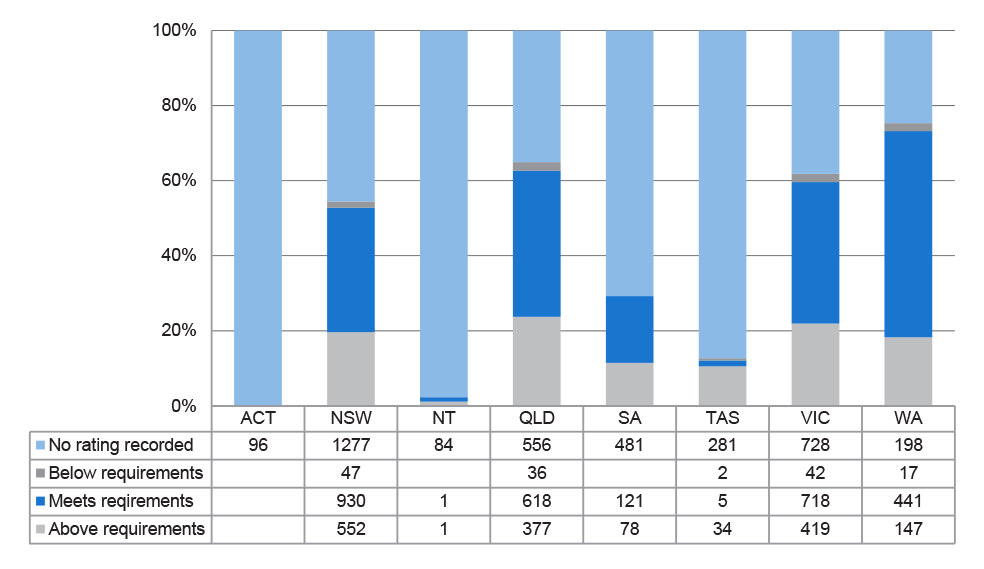

35. ANAO’s audit of the conduct of the 2007 election had recommended that the AEC complete performance appraisals for election officials and record these in the relevant systems in order that this data could be used to inform and improve recruitment practices for future electoral events. Some of the process shortcomings that informed this recommendation have been addressed by the AEC through improved administrative arrangements. However:

- a significant proportion of election officials, including senior election officials, surveyed by ANAO indicated that they were not aware of the AEC’s performance standards; and

- the extent to which performance ratings for staff were recorded declined between the 2010 and 2013 elections, with 20 per cent of roles at the 2013 election having no performance rating recorded.

36. Failure by the AEC to undertake performance assessments and record performance ratings against election roles, especially senior roles such as OICs, has significantly reduced the business benefits expected to be derived from the performance appraisal process. In particular, the available data suggests that previous election performance is a useful indicator of how people who are re-employed will perform at a subsequent election.

The AEC’s Interim Response to the Keelty Report (Chapter 7)

37. The arrangements adopted to monitor implementation of interim measures developed to respond to the Keelty report, and assess their effectiveness, demonstrate a greater commitment to organisational learning and improvement than was evident in the AEC’s response to ANAO’s earlier audit of the conduct of the 2007 election. However, by mid-September 2014 a detailed implementation plan for the 32 agreed recommendations had not yet been developed, some nine months after the Keelty report was received and the recommendations accepted. An implementation plan could also usefully incorporate action to be taken in response to the three recommendations made by ANAO concerning ballot paper transport and storage that were agreed to by the AEC in ANAO Audit Report No. 31 2013–14.

38. In addition, there were a number of aspects of the approach taken that reduced the assurance that can be provided about the extent to which the Keelty report recommendations were effectively implemented for the 2014 WA Senate election, and will be further progressed subsequently. Of particular note was that:

- the polling places and scrutiny facilities visited by the AEC were not selected in order to provide either a representative sample or to focus attention on areas of higher risk13;

- not all planned visits were undertaken; and

- the checklists developed to collect data on the implementation of the improved processes that had been developed were not adequate for their intended purpose, and insufficient steps were taken to promote complete and consistent assessments.

39. Further, in a number of respects, ANAO analysis of the records of the Keelty Implementation Team Extended (KITE)14 does not support the high levels of implementation of the interim measures that has been reported by the AEC. For example:

- the AEC advised JSCEM in March 2014 that every polling place for the WA Senate election would have a ballot box guard allocated. However, seven of the polling places inspected by KITE teams did not have a ballot box guard as part of the staff allocation;

- analysis by the AEC suggested that 186 of the 203 polling places inspected met the interim ballot paper secure zone requirements. However, for 49 of the 203 polling places the inspection records did not demonstrate that this requirement had been met. Further, the AEC’s summary report stated that ‘most ballot paper secure zones were signposted’ when ANAO analysis was that only 50 of the 203 inspection checklists specifically referred to ballot secure zone signage; and

- internal AEC reporting was that 92 per cent of polling place OICs were ‘comfortable with the new procedures’ relating to packaging and parcelling of election materials. However, ANAO’s analysis of the KITE checklists was that the AEC had wrongly counted 18 per cent of OICs as being clear about the new procedures.

Summary of entity response

40. The AEC’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response at Appendix 1.

Since the 2013 federal election, the AEC has been in a period of self-analysis, reflecting on existing operations in addition to the implementation of ANAO recommendations (Report No.31 2013–14 and Report No. 28 2009–10) and the recommendations from the Keelty Inquiry into the 2013 WA Senate Election. During this period, the AEC has also implemented recommendations, where possible, in the delivery of two highly scrutinised elections: the 2014 Griffith by-election and the 2014 WA half-Senate election.

The AEC is continuing to rebuild its reputation with the community and its stakeholders, supported by work to ensure the fundamental principles of integrity, quality and transparency are integrated throughout all aspects of the AEC’s operations. The AEC acknowledges that the issues identified in the ANAO report relate to areas of development for the AEC, particularly planning and implementation across the entire organisation. Implementation of the ANAO recommendations outlined in this report will support this process.

Recommendations

Set out below are the ANAO’s recommendations and the AEC’s abbreviated responses. More detailed responses from the AEC are shown in the body of the report immediately after each recommendation.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.52 |

To provide a greater organisational focus on improving its approach to the provision of polling and scrutiny premises, and to better manage the related task of recruiting and training temporary election employees, ANAO recommends that the AEC: (a) abolish, replace or consolidate (as appropriate) static polling places that are expected to receive relatively few votes, or where the premises have been assessed as not suitable for voters and/or election officials; and (b) review at a national level the reasonableness (in the context of identified and/or expected trends in voter behaviour) of divisional office estimates of the number of votes expected to be received at static polling places. AEC response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.20 |

To better position the organisation to efficiently and effectively deliver future election events, ANAO recommends that the AEC: (a) develop a workforce plan for its temporary election workforce well in advance of the expected timing of the next election; (b) periodically update this plan; and (c) actively monitor, at a National Office level, the implementation of the strategies included in the plan, and evaluate their effectiveness. AEC response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 4.32 |

To further improve the recruitment of election officials, ANAO recommends that the AEC implement appropriate controls that ensure persons interested in working in election roles have been assessed as suitable before any offer of employment is made. AEC response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 5.28 |

To be assured that people employed to fill election roles possess the knowledge and skills to perform their assigned duties, ANAO recommends that the AEC implement an efficient means of tracking the completion of its various training requirements in the lead up to future elections. AEC response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 5 Paragraph 6.36 |

Recognising the benefits that accrue to the AEC in re-employing election officials that have previously performed at or above the required standard, ANAO recommends that the AEC: (a) more clearly and consistently outline to temporary election employees the performance standards of the role to which they have been assigned and will be assessed against; and (b) implement controls that ensure the timely completion of performance assessments, including the recording of ratings in the relevant system and each temporary election official being advised of their rating. AEC response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background to the request from the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters for ANAO audit activity to follow-up the Australian Electoral Commission’s implementation of earlier ANAO recommendations. It also sets out the audit objective, criteria and methodology.

Background

1.1 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is responsible for conducting federal elections, maintaining the Commonwealth electoral roll and administering the political funding and disclosure requirements in accordance with the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). In addition, the AEC conducts referendums in accordance with the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984. The AEC also provides a range of electoral information and education programs in Australia, as well as in support of Australia’s international interests. Its stated outcome is to:

Maintain an impartial and independent electoral system for eligible voters through active electoral roll management, efficient delivery of polling services and targeted education and public awareness programs.

1.2 The AEC has a three-person Commission comprising the Chairperson, the Electoral Commissioner and a non-judicial member. It operates through a three tier structure of a national office in Canberra, State and Territory offices as well as divisional offices (both standalone and co-located in the form of larger work units) responsible for electoral administration across Australia’s 150 electoral divisions. The AEC employed nearly 850 ongoing staff as at 30 June 2013. For each Federal election, the AEC recruits a large temporary workforce (for the 2013 election, 68 834 people were employed) and operates a significant number of polling places (7697 static polling places and 645 pre-poll voting centres were used for the 2013 election).

1.3 In April 2010, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) tabled a performance audit report on the AEC’s preparation for and conduct of the 2007 Federal election.15 ANAO made nine recommendations, including four relating to the AEC improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll. Other recommendations included the AEC improving its workforce planning, and enhancing the accessibility and suitability of polling booths and scrutiny centres. ANAO also recommended that the AEC identify and assess options that would provide greater physical security over the transport and security of completed ballot papers.

1.4 In this latter respect, during the conduct of the 2013 election, 1370 Western Australia (WA) Senate ballot papers were lost. This situation led to:

- the voiding of the election of six Senators for WA and a new election for WA Senators being held on 5 April 2014, with a different political outcome compared with the counting of votes lodged at the September 2013 election; and

- the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM or the Committee) writing to the Auditor-General requesting performance audit activity relating to the AEC’s implementation of earlier recommendations made by ANAO.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.5 In view of the importance of the AEC’s functions and responsibilities and the interest shown by JSCEM in the AEC’s implementation of the ANAO’s earlier recommendations, and to address the matters raised by the Committee in a timely manner, the Auditor-General decided to conduct three related performance audits.

1.6 The report of the first audit was tabled in May 2014 (ANAO Audit Report No.31 2013–14, The Australian Electoral Commissions’ Storage and Transport of Completed Ballot Papers at the September 2013 Federal General Election). Its objective was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the recommendation made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 relating to physical security over the transport and storage of completed ballot papers. The follow-up of implementation of that recommendation was prioritised as it was an area of particular interest to the Committee.

1.7 The objective of the second audit, which is the subject of this report, was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the Australian Electoral Commission’s implementation of those recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 relating to:

- a more strategic approach to election workforce planning, with a particular focus on the selection, recruitment, training and performance evaluation of election officials (Recommendation Nos. 5 and 6);

- the suitability and accessibility of polling booths and fresh scrutiny premises (Recommendation No. 7); and

- the transport and storage of completed ballot papers (Recommendation No. 8(b)), in respect to matters not fully addressed in ANAO Audit Report No.31 2013–14. Specifically, compliance with new policies and procedures introduced to address the Keelty report16 recommendations for the WA Senate election 2014.

1.8 A third audit of the AEC’s implementation of recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 has been included in the ANAO’s 2014–15 forward work program. The focus of the third audit is expected to be on the recommendations that relate to the AEC improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll.

1.9 The remaining recommendation made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 (Recommendation No. 9) related to the AEC developing comprehensive performance standards for the conduct of elections. The AEC advised the March 2012 meeting of its Business Assurance Committee (BAC) that implementation of that recommendation had been completed in February 2012.17 However, advice provided by the AEC to JSCEM in July 2014 suggested that implementation of this recommendation was ongoing, as well as incorrectly advising JSCEM that implementation of this recommendation was within the scope of the second ANAO follow-up audit, which is the subject of this report.18

Criteria and methodology

1.10 To form a conclusion against the objective for this audit, described in paragraph 1.6, the ANAO adopted high-level criteria relating to whether the AEC responded adequately and effectively to address the matters raised by ANAO that led to the recommendations being made.

1.11 The methodology employed for the audit has included:

- examining AEC documentation, such as guidelines, training materials, reports, contracts and briefing materials;

- examining and analysing relevant records, including from relevant information technology systems concerning the recruitment, training and payment of temporary employees engaged to assist with the conduct of the 2013 election;

- interviewing AEC staff and requesting relevant records;

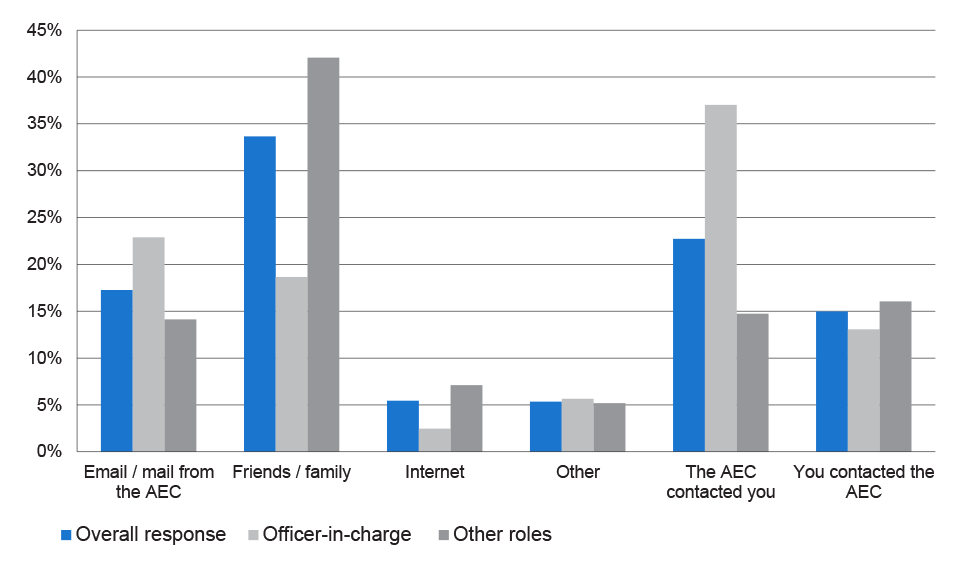

- surveying a sample 8500 people employed by the AEC as election officials during the 2013 election. The survey focused on gauging people’s views on the AEC’s management of the temporary election workforce, and also sought information about their experiences during recruitment, training, pre-polling and on election day; and

- examining the establishment and activities of the teams tasked with assessing and inspecting compliance with the interim policies and procedures adopted for the April 2014 WA Senate election to address the Keelty report recommendations.

1.12 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $607 000.

Structure of the report

1.13 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Polling and Scrutiny Premises |

Examines the action taken by the AEC in response to ANAO’s earlier recommendation concerning improved approaches to polling and scrutiny premises. |

|

Workforce Planning |

Analyses the response by the AEC to ANAO’s earlier recommendation that it improve its election workforce planning by critically examining its future workforce needs and composition. |

|

Recruiting Election Officials |

Examines whether the AEC has strengthened its recruitment of election officials in order that suitable persons were recruited in a timely manner for the 2013 election, with priority given to senior polling roles. |

|

Training Election Officials |

Analyses the extent to which election officials were trained prior to the 2013 election, and how useful participants found their training. |

|

Performance Assessment |

Examines the extent to which the AEC completed performance appraisals of election officials employed for the 2013 election. |

|

The Australian Electoral Commission’s Interim Response to the Keelty Report |

Examines the AEC’s implementation of interim measures introduced during the 2014 WA Senate election to address the recommendations of the Keelty report, with a particular focus on matters relevant to ballot paper transport and storage. |

2. Polling and Scrutiny Premises

This chapter examines the action taken by the AEC in response to ANAO’s earlier recommendation concerning improved approaches to polling and scrutiny premises.

Introduction

2.1 The significant majority of Australians who vote do so in person either at a pre-poll voting centre (PPVC) prior to election day or on the Saturday of the election at a static polling place. For example, at the 2013 election more than 91 per cent of the 14.7 million votes counted were received at either a PPVC (18.1 per cent) or static polling place (72.9 per cent). The provision of these voting facilities involved a considerable logistics workload for the AEC at divisional office level including:

- inspecting potential premises in advance of the election;

- making arrangements to access the premises and setting them up for polling purposes; and

- recruiting and training the temporary employees required to staff the static polling place premises and PPVCs.

2.2 Divisional and state offices are also required to arrange premises for the fresh scrutiny count of votes received.

2.3 The seventh recommendation from ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 suggested various ways the AEC could improve the suitability and accessibility of polling and scrutiny premises. ANAO analysed the AEC’s implementation of each part of that recommendation.

Pre-poll voting centres and fresh scrutiny premises

Early voting at pre-poll voting centres

2.4 PPVCs are established to allow voters who will not be able to visit a polling place on the day of the election to cast their vote in advance as an alternative to postal voting. This is known as ‘pre-poll voting ‘and, together with postal voting, is a type of early voting. The AEC’s PPVC policy requires that pre-poll voting facilities be provided at all divisional offices19 and that each division will offer pre-poll voting services at a PPVC established in at least one other site within the division.

2.5 Eligible voters are increasingly seeking to vote early, particularly at PPVCs. In this respect, the AEC advised JSCEM in its submission to the Committee’s inquiry into the 2010 election that the trend towards early voting:

…needs to be assimilated as a critical element of the environment in which elections must now be administered.

2.6 Consistent with this view, the AEC significantly increased the number of PPVCs for the 2010 election. Based on figures advised to JSCEM by the AEC, the number of PPVCs increased by nearly 59 per cent between the 2007 and 2010 elections. This assisted the AEC to accommodate a 38 per cent increase in the number of pre-poll votes between the two elections.

2.7 The number of PPVCs the AEC reported as having been employed for the 2013 election fell slightly from the 682 used at the 2010 election to 645 (a reduction of 5.3 per cent).20 The AEC expected to receive, in aggregate, 1.77 million ordinary and declaration votes at those PPVCs and at pre-poll voting facilities provided by divisional offices.21 This was an estimated 18 per cent increase on the number of votes received at PPVCs for the 2010 election, indicating the AEC expected the trend towards PPVC voting to increase, but less significantly than had occurred at the 2010 election (where nearly 34 per cent more votes were received at PPVCs than had been received at the 2007 election).

2.8 The AEC significantly under-estimated the number of votes that would be received at PPVCs. As it eventuated, more than 2.5 million ordinary and declaration votes were received at the 2013 election, an increase of 63.7 per cent on the number received at the 2010 election. The AEC’s estimation of the number of pre-poll declaration votes was, in aggregate, within 10 per cent of the number of such votes received. However, the AEC’s estimation of the number of ordinary pre-poll votes was quite inaccurate, with the aggregate estimate being 35 per cent lower than the actual number of such votes received. As a result, PPVCs collectively handled significantly more votes than had been estimated as part of election planning and preparations, as well as significantly more than had been accommodated at earlier elections.

Scrutiny premises

2.9 The initial scrutiny of all ordinary votes taken at polling places and PPVCs centres commences after the polls close. After election night, the results of the election night count are rechecked in the fresh scrutiny.22 For House of Representatives votes, the fresh scrutinies are conducted at scrutiny centres arranged by the divisional office, which is followed by the full distribution of preferences (which determines the formal result of each election). For Senate votes the fresh scrutinies of above-the-line and obviously informal votes are completed at divisional office scrutiny centres. All other Senate ballot papers are sent to a Central Senate Scrutiny (CSS) location in each state and territory.

2.10 The AEC’s scrutiny policy outlines that divisional returning officers (DROs) are responsible for determining when and where a scrutiny will be conducted, as well as for deciding on the number and types of scrutinies to be conducted. The CSS premises are organised by State Offices.

Use of Australian Government agency premises

2.11 In respect to the premises used as PPVCs and for fresh scrutinies, ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 observed that the:

- difficulties being experienced with hiring suitable static polling place premises were compounded in relation to PPVCs. Among other factors, this reflected that the AEC needed short-term leases for a three to four week period which was shorter than what the market wanted to offer; and

- the lease costs of PPVCs and fresh scrutiny centres varied markedly, with some considerable increases in the costs between the 2004 and 2007 elections.

2.12 Similarly in this latter respect, in its primary submission to JSCEM’s inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 election, the AEC stated that one of the factors that contributed to higher overall election costs was ‘increased property and venue hire costs due to additional premises requirements for pre-polling’.

2.13 The Australian Government has a significant non-Defence domestic property portfolio, although there have been changes over time in the extent to which these properties are leased rather than owned. By way of context, in 2012 the Government’s non‐financial assets of land, buildings, investment property, plant and equipment was valued at approximately $94 billion.23 In addition, expenditure on property represents a considerable use of government resources: in 2011–12 operating lease rental expenses alone were over $2.6 billion; with lease commitments of over $9.8 billion for the five‐year period to 2015–16.24

2.14 Notwithstanding the size of the Australian Government’s domestic property portfolio, at the time of the 2007 election the AEC made little use of Australian Government owned or leased property to assist with pre-poll voting or the conduct of fresh scrutinies. Specifically:

- across Australia, only two Australian Government premises were used as a PPVC; and

- 40 Australian Government premises were used for fresh scrutiny across three states (no Australian Government premises were used in the remaining three states and two territories).

2.15 ANAO identified that there was an opportunity for the AEC to seek to make greater use of the Australian Government’s domestic property portfolio for election purposes. Accordingly, the third element of Recommendation No.7 in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 was that the AEC:

negotiate the use of suitable Commonwealth-agency venues, in particular as pre-poll voting centres and fresh-scrutiny centres.

2.16 Initially (in March 2011) the AEC advised the BAC that it would implement this part of the recommendation by approaching relevant agencies with a view to identifying and using suitable Australian Government premises for election period activities. Such an approach would have been consistent with the ANAO recommendation. In this context, ANAO sought advice from the AEC as to which agencies had been approached together with relevant supporting documentation (such as correspondence and records of meetings). The AEC’s response did not identify that a range of agencies had been approached, but stated that:

The primary agency that the AEC works with to assist with election period venue sharing is the Department of Human Services. Two major agreements were in place for the 2013 Federal election, relating to:

- the use of DHS premises to house election service centres; and

- the use of DHS facilities and infrastructure support to support remote mobile polling across Northern Australia.

There was some consideration of also using DHS premises for early voting at pre-poll voting centres (PPVCs) however it became clear that Centrelink and Medicare offices are not suitable to reconfigure as early voting centres to service the volume of electors that pass through PPVCs. DHS offices hold stocks of AEC forms, such as enrolment forms, and provide access to the AEC website (for electors to enrol and apply for postal votes) via its online access terminal.

The AEC and DHS jointly engage in ongoing dialogue via a formal Strategic Governance Committee which meets regularly to discuss, amongst other items, shared services. The ongoing existence of this group will facilitate ongoing identification of opportunities for collaboration in the delivery of election services.

2.17 ANAO’s recommendation was explicitly focused on the greater use of Australian Government owned or leased premises as PPVCs and fresh scrutiny centres. The arrangement with DHS did not relate to PPVC or fresh scrutiny premises. Further, the AEC did not identify to ANAO that it had approached any other Australian Government agencies with a view to using premises those agencies owned or leased as a PPVC or fresh scrutiny centre. In October 2014, the AEC advised ANAO that it:

intends to use the success of this engagement and build on the approach for Election Service Centres with DHS at the next election, identifying opportunities for further cooperation.

2.18 By the November 2011 BAC meeting, the AEC was no longer proposing to approach relevant Australian Government agencies as had been indicated to the BAC in March 2011. Rather, the BAC was advised that:

Securing of venues for voting and scrutinies is a divisional office responsibility. The recommendation has been referred to the Election Procedures Manual review team to build into policy materials as part of the 2011–12 review of the Election Procedures Manual.

2.19 In advising ANAO on the steps it had taken to implement Recommendation No. 7 from ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10, the AEC did not identify what changes had been made to the Election Procedures Manual to assist divisional offices make greater use of Australian Government premises as PPVCs and fresh scrutiny centres. ANAO’s analysis was that the Election Procedures Manual for the 2013 election did not seek to progress greater use of Australian Government agency premises as PPVCs or fresh scrutiny centres. This matter was also not addressed in the AEC’s PPVC policy or the scrutiny policy, with the later simply stating:

The DRO will make arrangements to hire suitable premises (if required) and to employ an adequate number of suitable staff.

2.20 ANAO also asked the AEC to identify the fresh scrutiny premises used in each of the 150 divisions, and provide ANAO with a copy of the agreement signed for the use of these premises. There were no instances where the information provided to ANAO by the AEC identified that Australian Government premises had been used for fresh scrutiny purposes. Rather, the information provided to ANAO identified that divisional offices typically sought to identify suitable premises that would be available for lease commercially.

2.21 For example, including the CSS premises, there were six scrutiny premises used in South Australia. The State Office records provided to ANAO outlined that the approach taken in respect to premises25 for the Central Election Tri (comprising the divisions of Adelaide, Hindmarsh and Sturt) did not include considering surplus space available in premises occupied by other Australian Government entities.26 Rather:

We have been searching for a suitable space for a period of 12 months. Whilst I looked at a number of different properties, across the centre of metropolitan Adelaide, over this time only three potential spaces were suitable. Two properties met our budget and other requirements and we obtained a quote from both of them. The third property was ultimately deemed unsuitable for a number of reasons. A number of owners were unwilling to negotiate a short term lease and the size and structure of many properties did not give us flexibility.

2.22 Key parameters of the premises sought for the Central Election Tri was at least 1500 square metres of space for a short term lease of two months, with options for a longer period. At this time, the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO27) Adelaide Central Business District premises had significant unused capacity, in excess of that required by the AEC. However, the AEC did not seek to engage with the ATO as to the potential practicalities of the AEC making use of the unused space. Similarly, three other ATO leased properties in locations close to those used by the AEC for fresh scrutiny centres28 had significant unused capacity at the time of the 2013 election but the AEC similarly did not engage with the ATO in relation to the practicalities of unused space being used for vote counting purposes.

Static polling place premises

2.23 The provision of adequate voting facilities to any elector who wishes to attend a polling place is important to the effective delivery of elections. The AEC recognises that there would be significant consequences should there be insufficient facilities to support voters on election day. In this context, in October 2014 the AEC advised ANAO that:

While the trend for voting on polling day is decreasing, the total number of eligible electors will increase over time. It is difficult to accurately project the impact of these trends on the need for available polling places, further complicated by the variable timing of federal elections and concomitant elector behaviour. Early voting patterns are impacted by a range of factors, including individual circumstances and other events external to the election (for example, school holidays), complicating the projection of early voting uptake and the number of premises required to support the Australian electorate.

Estimating the number of votes at static polling places

2.24 The number of ordinary votes estimated to be received at each polling place is an important factor in determining the number of staff the AEC allocates to a polling place and therefore needs to recruit and train. In this context, ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 observed that the output of the AEC’s predictive model of voter numbers agreed well with the actual number of ordinary voters who passed through polling booths at the 2007 election.

2.25 At the 2010 election, static polling places received 10.8 million votes, or 82 per cent of all votes. For the 2013 election, the AEC’s staffing of polling places was based on an aggregate estimate of them receiving 11.47 million votes, an increase of nearly 630 000 on the number received at the 2010 election. In this context, there would have been benefit in the aggregate of these estimates being critically reviewed at a national level given they meant divisions were forecasting that, nation-wide, the trend away from voting on election day at static polling places towards early voting had ended. Specifically:

- the increase in the number of votes expected to be received at static polling places (629 925) was slightly more than the 624 539 increase in the number of persons enrolled to vote between the close of rolls for the 2010 election and the 2013 election, indicating little allowance was being made for newly enrolled voters to vote at PPVCs, or for voters from the 2010 election who visited static polling places in 2010 to move to early voting;

- the percentage of votes expected to be received at static polling places, as a percentage of all votes received, was expected to remain at around the 82 per cent figure that occurred at the 2010 election, rather than reducing as voters increasingly vote early. As it eventuated, fewer than 73 per cent of total votes counted were received at static polling places; and

- the aggregate estimate was 2.4 per cent higher than the 10.08 million ordinary votes received at static polling places during the 2010 election.

2.26 In this context, it was unsurprising that the number of votes received at static polling places on 7 September 2013 was significantly less than the estimates used by the AEC to allocate staff to polling places. Specifically, the AEC over-estimated by 1.39 million (13.8 per cent) the number of votes that would be received at static polling places. The greatest number of over-estimated votes related to ordinary votes with the AEC over-estimating by 1.02 million (11 per cent) the number of such votes that would be received. In percentage terms the error was greater in relation to declaration votes, with the AEC over-estimating by 47.5 per cent the number of such votes that would be received at static polling places. ANAO analysis indicated that estimates with a similar level of accuracy to those at the time of the 2007 election (see paragraph 2.24) would have reduced by more than 6000 (or over 8 per cent) the number of polling staff allocated for the 2013 election.

Number, location and size of polling place premises

2.27 In its primary submission to the JSCEM inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 election, the AEC observed that it:

…experiences increased volumes at almost all of the logistical and operational pressure points during the election delivery period. This is consistent with experience of increasing volumes over the last four federal elections.29

2.28 However, one area where the AEC experienced a significant decline in volume related to the number of electors who voted on polling day at a static polling place. ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 outlined that the trend to early voting (through pre-poll, mobile or postal voting) has important effects on the number and location of static polling place premises, and the staff required to be recruited and trained to work at those polling places.

2.29 As outlined at paragraphs 2.5 to 2.8, the AEC responded to the trend towards greater early voting by increasing the number of PPVCs between the 2007 and 2010 elections. For the 2013 election, the number of PPVCs did not change significantly, but the number of votes received at PPVCs increased significantly meaning that, on average, PPVCs handled more votes than at the 2010 election.

2.30 Similarly, it would be reasonable to expect that the trend towards early voting, and the general expectation that Australian Public Service agencies will pursue efficiencies in delivery methods, would have caused the AEC to give management attention to the number, location and size of static polling places. However, the number of static polling places has remained largely unchanged across the last four elections, at around 7700 premises30, with the same premises typically used at each successive election unless they are not available (see further at paragraph 2.37). In this context, although a key driver of the number of polling place staff that it needs to recruit and train, the AEC has no efficiency targets or measures for its polling places. Rather, the AEC’s Static Polling Place Policy of March 2013 outlines that:

- commonality with State and Local Government polling places is an ‘important consideration’ when selecting polling places;

- as there are many different circumstances affecting polling places, there are no ‘fixed rules’ regarding the size and number of polling places in each division;

- the ‘preferred maximum size’ of a polling place is 4000 to 5000 votes, as polling places that exceed this size are difficult for one officer-in-charge (OIC) to manage; and

- there is no fixed voter figure for the appointment of a polling place, however a polling place serving fewer than 200 electors would be an ‘exceptional case’ and that:

in major urban areas, a benchmark figure of 1,000 to 1,200 votes should be considered as the minimum polling place size when appointing new polling places. However, no action should be taken on any existing polling place solely because it does not meet this minimum size.

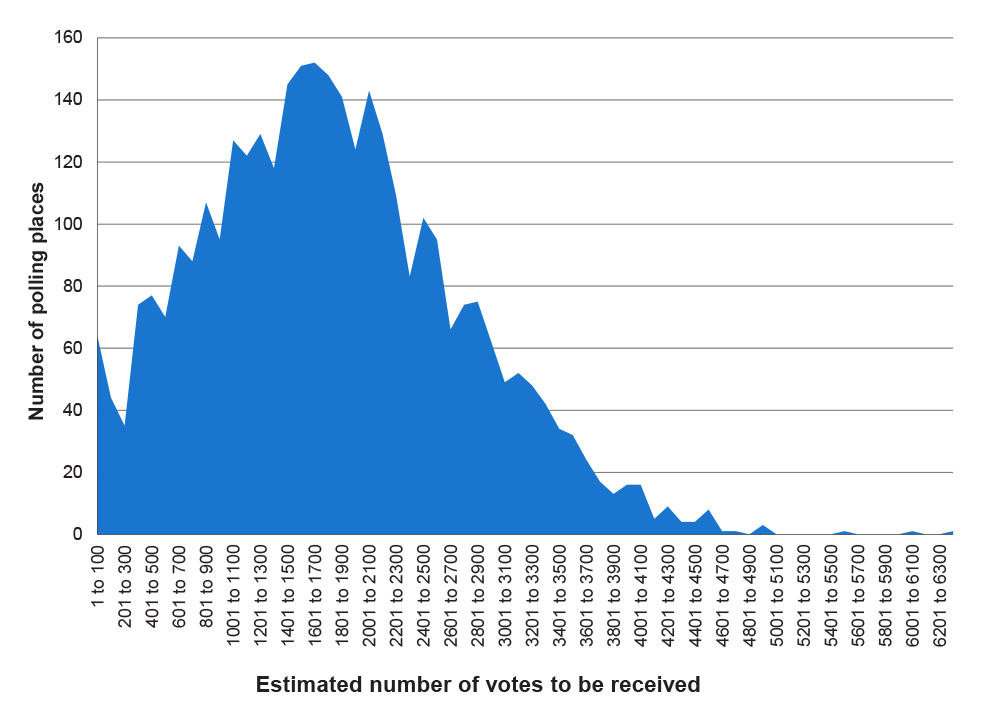

2.31 There were relatively few polling places at the 2013 election where the AEC expected, or received, votes consistent with the ‘preferred maximum size’ of 4000 to 5000 votes. Particularly in metropolitan divisions, it was quite common for the AEC to use a large number of polling place premises, often located in close proximity to one another, with most of these polling places expected to receive a relatively small number of votes (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Votes estimated to be received in metropolitan division polling places at the 2013 election

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC data.

2.32 This situation indicates that the AEC has not been sufficiently attuned to the opportunity it has had to significantly reduce the number of polling place staff that need to be recruited and trained by employing fewer, and more suitable31, polling places by:

- abolishing32, replacing or remediating static polling place premises that are identified in the program of polling place inspections to not fully meet the needs of voters and/or election officials (along the lines previously recommended by ANAO); and

- rationalising the number of polling places, including by seeking to use newer, larger community facilities funded by the Australian Government (as previously recommended by ANAO, and discussed further at paragraphs 2.40 to 2.45).

2.33 For example, in metropolitan divisions alone, ANAO analysis indicates that abolishing polling places expected to receive relatively few votes and combining polling places located relatively close together could require the AEC to recruit and train up to 4600 fewer polling place staff. In this context, the AEC advised ANAO in October 2014 that it:

will continue to examine its methodology in identifying smaller polling places that could be closed without compromising voter services, and acknowledges that cost savings may be achieved. However, it is important to note that there is unlikely to be a straight linear relationship between a reduction in polling places and a reduction in staff required. For example, there may be a ‘displacement effect’ where voters instead access services at nearby polling places, thereby changing the staffing mix at those venues.33 The AEC is also mindful of the reputational damage that can result when a community feels that ‘their’ polling place has been closed or moved, regardless of the logical basis for such a move.

Polling place inspection program

2.34 Both static polling places and PPVCs are subject to an AEC inspection program. The AEC has advised JSCEM that the purpose of the inspection program is to ensure that each polling place:

- meets the AEC’s legislative and operational requirements; and

- satisfies the requirements of the Workplace Health and Safety Act 2011.

2.35 Similar to the situation identified at the time of the 2007 election in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10, at a national level the AEC continues to not collect or analyse data on the results of the polling place inspection program. Such a situation did not place the AEC in a strong position to implement Recommendation No. 7(d) from the earlier audit report, which included systematic post-election evaluation of the polling place inspection program.

2.36 In the absence of national data, as part of this follow-up audit ANAO sought copies of polling place inspection reports for a sample of polling places used at the 2013 election, as well as (for comparative purposes) the reports of inspections conducted prior to the 2010 election where the premises were used at both elections. However, for:

- 19 per cent of the premises that were used at both elections, the AEC was unable to provide the ANAO with a copy of a completed report for an inspection undertaken prior to the 2010 election. In a number of instances, the AEC advised the ANAO that the reports had been destroyed after the 2013 election; and

- 11 per cent of the premises used at the 2013 election, the AEC was unable to provide the ANAO with a copy of a completed report for an inspection undertaken prior to the 2013 election.

2.37 Where reports were available, it was common for them to evidence that the inspection had identified that the polling place premises were less than fully satisfactory. Specifically, for 88 per cent of the sampled inspections undertaken prior to 2013 election where a report was able to be provided to ANAO, the inspection identified shortcomings with the premises. This was most often the case in relation to the provision of access for voters with a disability, and the provision of amenities for polling place staff. However, the AEC’s policies and procedures are silent on the action, if any, that is to be taken when a polling place inspection identifies that the premises are not fully satisfactory. In this respect:

- over 90 per cent of the premises used as a static polling place for the 2010 election were used again at the 2013 election, a situation similar to that observed by ANAO at the 2007 election; and

- in only 9 per cent of those instances sampled by ANAO where the inspection of the sampled polling place had identified shortcomings, did the division advise ANAO that it had considered alternative premises to those that had been identified as being deficient. Advice provided to ANAO by the sampled divisions outlined that, in the main, alternative premises are only considered when previously used premises are not available.

2.38 This situation helps to explain why the AEC has not made significant progress in delivering upon its publicly stated34 aim to maximise the number of polling places at each election which have full or assisted wheelchair access. In this respect, the proportion of polling places assessed by the AEC as providing full access has fallen from 29.5 per cent at the 2007 election, to 16 per cent at the 2010 election35 to 11.8 per cent at the 2013 election (noting that a new building accessibility standard36 commenced operation on 1 May 2011).

2.39 Consistent with one of the action items under the AEC’s Disability Action Plan 2008–2011, the new building accessibility standard was reflected in an update to the AEC’s Polling Premises Suitability Inspection Tool. It was also reflected in the AEC’s inspection of some polling places before the 2013 election involving a downgrade of the previous assessment of the extent to which the premises were accessible. In this respect, for 18 per cent of the polling places in ANAO’s sample, the AEC inspection had concluded the premises did not provide wheelchair access.37 However, in none of these instances did the AEC seek to identify an alternative polling place premise that would provide improved accessibility or to engage with the premises owner about possible modifications, a situation that does not sit comfortably with the AEC’s Disability Inclusion Strategy. In this context, in July 2013 the AEC advised JSCEM (in response to a 7 July 2013 letter from the Committee Chair) that:

For the 2015 inspection program AEC staff have been asked to approach premises owners in cases where small modifications to a premises would allow a premises to be rated as fully accessible. For example, by opening up a staff car park for disabled electors where this is closer to the polling place entrance than the general parking facilities, a premises that may have been rated as not accessible in 2013 could be rated as accessible at the next election

Opportunities to benefit from Australian Government funding for community infrastructure

2.40 ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 outlined that it was common for community facilities used as polling places to have been constructed many years earlier, and that some polling places were less than optimal. Given the age of some polling place premises and the shortcomings often identified by polling place inspections, ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 suggested that the AEC seek to secure improved facilities for elections. In this respect, the first element of Recommendation No. 7 of ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 was that the AEC work with Australian Government agencies that provide funding for the construction, upgrade and/or maintenance of community facilities that may be suitable for future use as polling places so as to identify opportunities to secure access to these facilities for electoral events.

2.41 When informing the BAC that implementation of ANAO Recommendation No. 7 had been completed, the AEC advised that it had held discussions with agencies. Accordingly, as part of this follow-up audit, ANAO sought advice from the AEC, and copies of any meeting records or related correspondence, as to which specific Australian Government agencies the AEC held discussions with in the context of Recommendation No.7(a). However, the AEC was unable to identify to ANAO any Australian Government agencies that it had engaged with.38

2.42 Since ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 was tabled, ANAO has audited a number of programs that have funded community infrastructure facilities of the type that have been used by the AEC as polling place premises. However, in only one instance was a project funded under one of those programs used by the AEC as a polling place for the 2013 election. This reflected the initiative of a DRO for one Victorian division who was aware of the new facilities that were being constructed with funds awarded under the Better Regions Program, rather than any systemic action on the part of the AEC. Specifically, having not engaged with the administering agency, the AEC National Office had not identified other projects funded under that program that would also have been worth being considered for use as polling place premises for the 2013 election.

2.43 Similarly, the AEC did not engage with the administering department of other programs audited by ANAO that were awarded funding for the construction or upgrade of community infrastructure of the type often used as polling place premises. As a result, for example, there were no instances where a project funded under the following programs was used by the AEC as a polling place premise for the 2013 election:

- the $550 million Strategic Projects Component of the Regional and Local Community Infrastructure Program. A significant proportion (35 or 26 per cent) of the 137 projects approved for funding were the types of community facilities that have been used by the AEC for electoral purposes (such as town halls and community centres); or

- the Regional Development Australia Fund (RDAF), which was the former government’s flagship program to support regional infrastructure projects. The first four rounds of RDAF were conducted between 2011 and 2013, with a total of $575.8 million being approved to fund 202 capital infrastructure projects across Australia, including town halls, community centres and cultural centres.

2.44 In a number of instances, premises funded under the Australian Government community infrastructure programs that were not considered for use at the 2013 election were located in close proximity to the premises that were used at the 2013 election. In a sample of such instances examined by ANAO, it was common for:

- the AEC’s pre-election inspection of the premises used at the 2013 election to have identified that the facilities did not meet the needs of either AEC polling place staff or of voters (for example, in relation to accessibility); but

- DROs to advise ANAO that alternatives to those premises assessed by the AEC as not fully meeting its needs were not considered.

2.45 As the Australian Government continues to implement community infrastructure funding programs, there remain opportunities for the AEC to implement Recommendation No. 7(a) from ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 by its National Office engaging with the agencies that administer those programs. There would also be benefits in the AEC examining community infrastructure funded under past Australian Government programs so that explicit consideration might be given by divisional offices to using larger, more modern premises as static polling places.

Standing arrangements with venue owners

2.46 The second element of Recommendation No. 7 from ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 related to the AEC seeking to implement standing arrangements with venue owners, particularly state governments, to secure suitable and accessible polling booths. AEC’s response to this recommendation outlined that it already had formal arrangements with some state government venue owners and informal arrangements with others, and acknowledged that there would be benefits in expanding the range of formal arrangements.

2.47 In relation to implementing this element of the recommendation, the BAC was advised in March 2011 that ‘State managers will be tasked with identifying other opportunities for standing arrangements that would facilitate better access to suitable polling venues’. Accordingly, ANAO sought from the AEC a copy of the instruction given to State Managers to undertake this work as well as copies of any standing arrangements entered into with venue owners.

2.48 The AEC was unable to provide ANAO with a copy of any records of the instruction given to State Managers.39 Nevertheless, ANAO was provided with advice and information in respect to any standing arrangements entered into by the State Offices.

2.49 The agreements provided to ANAO typically involved extending an agreement that was in place prior to ANAO’s recommendation being made, or agreements being entered into after the BAC had been informed that the recommendation had been implemented. Further, the agreements provided to ANAO were few in number and, in the main, related to state education departments and the use of school facilities as static polling places. This information did not indicate that there had been any significant expansion in the extent to which the AEC had implemented standing arrangements with venue owners. For example, for :

- Western Australia, the only agreement provided to ANAO was with the state Department of Education, and this was signed in December 2013, such that, there was no agreement evident as being in place prior to the September 2013 election let alone in 2011 prior to the BAC being informed that implementation of the recommendation had been completed;

- Victoria, the State Office advised that:

… there were mixed results. During 201240 the Victorian State Manager contacted the Victorian Education Department to attempt to set up a meeting to negotiate a consistent costing framework for the hiring of public school premises. This engagement was being sought as our divisional staff were being quoted vastly different amounts when approaching public schools to discuss the hire of premises as static polling places. Unfortunately, the State Manager was not able to progress this arrangement as the Department was not responsive to requests for dialogue on this matter.

Conclusion

2.50 The AEC’s approach to implementing ANAO’s earlier recommendation concerning polling and scrutiny premises was inadequate. As a result, there was little change evident between the 2007 and 2013 elections in how the AEC goes about arranging premises for voting and vote counting purposes. Of particular note in this respect was that:

- unless the premises used at the 2010 election were not available for hire, the AEC has continued its practice of re-using the same premises at successive elections irrespective of whether those premises meet the needs of voters and/or election officials and with little consideration given to the availability of more suitable premises (including community facilities funded by the Australian Government);

- the number of static polling place premises has remained largely unchanged across the last four elections, notwithstanding the continuing trend towards early voting rather than voting on election Saturday. In metropolitan divisions alone, ANAO analysis indicates that abolishing polling places expected to receive relatively few votes and combining polling places located relatively close together into newer, larger premises (where available) could require the AEC to recruit and train 4600 fewer polling place staff; and

- the AEC staffed static polling places on the basis that the trend towards early voting had ended. More accurate estimates would have reduced by more than 6000 the number of election officials allocated for polling day for the 2013 election.

2.51 In July 2014, the AEC advised JSCEM that the ongoing implementation of reforms that were proposed following the 2013 election may present financial pressures, and that this is a matter that would be put before the Department of Finance. In this context, improvements to existing approaches to the provision of polling and scrutiny premises can be expected to not only improve the effectiveness of the AEC’s conduct of future elections but also deliver cost savings particularly as a result of needing to recruit and train fewer staff for static polling places. Judgements will necessarily be required to balance the various relevant considerations involved in appointing and abolishing polling premises, but there are real benefits in the AEC considering a wider range of options for premises.

Recommendation No.1