Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Rural and Remote Health Workforce Capacity - the contribution made by programs administered by the Department of Health and Ageing

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing's administration of health workforce initiatives in rural and remote Australia.

Summary

Introduction

Australia's health system

The health system in Australia is a blend of Australian Government and State/Territory Government responsibilities with a mix of public and private funding. Constitutional powers identify the scope of Commonwealth responsibility and the residual powers that pertain to the States concerning health matters.1

The Australian Government has a leadership role in the development of health policy, particularly in relation to national issues such as public health, research and national information management. The Australian Government funds most out of hospital medical services through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), and most health research. The Australian Government also funds the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), private health insurance rebates, residential aged care services, services for veterans and primary health care for Indigenous Australians.

The States and Territories are primarily responsible for the delivery and management of public acute and psychiatric hospital health services and a wide range of community and public health services including school health, dental health, maternal and child health and environmental health programs. The States and Territories are also responsible for maintaining direct relationships with most health care providers, including the regulation of health professionals.

Public hospitals and community care for aged and disabled persons are jointly funded by the Australian Government and the States and Territories.2

Health workforce roles and responsibilities

In common with the rest of the health care system and systems overseas, Australia's health workforce arrangements are complex and interdependent. The most prominent entities that control or impact on workforce deployment and scopes of practice include: governments; bodies with delegated powers (including registration boards and some accreditation agencies); employers; educators and trainers; professional associations; industrial associations; and health insurers. State and Territory Governments play a particularly important role, so that even where national approaches are adopted, the ability to ‘make things happen' often lies with those jurisdictions.3

Roles and responsibilities in rural and remote areas

In rural and remote Australia, the State and Territory Governments provide the majority of the health services infrastructure through rural health and hospital services.

The role of the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) in enhancing the rural and remote health workforce has been to increase the number of General Practitioners (GPs) working in rural and remote Australia through programs that focus on the use of Overseas Trained Doctors (OTDs); bonded medical places; scholarships for students from rural areas; and retaining GPs already working in rural and remote Australia through the provision of access to continuing education, locum services and retention payments. In addition, there are incentives to increase the number of nurses working in general practice in rural and remote Australia.

Health status of Australians living in rural and remote areas

While the general health level of Australians is quite high, the same is not true for those Australians living in rural and remote areas. Around one–third of all Australians live outside of major metropolitan areas4, yet the proportion of primary care health practitioners in these regions is notably lower. As geographic isolation becomes more pronounced, the numbers of Indigenous Australians living in these areas rise compared to other Australians, for example, 26 per cent of the Indigenous population lives in areas classified as ‘remote or very remote' compared to 2 per cent of the non–Indigenous population.5 The health status of Indigenous Australians, on average, is very poor compared to non–Indigenous Australians.

Following a request from the Prime Minister in December 2007, the Minister for Health and Ageing requested DoHA to undertake an audit of the shortage of doctors, nurses and other health professionals in rural and regional Australia, and to describe the extent of these shortages by profession. The Report on the Audit of the Health Workforce in Rural and Regional Australia confirmed that the distribution of health professionals in relation to the distribution of the population in Australia was uneven, and particularly lacking in regional and remote Australia. Medical practitioners were in low supply relative to the population in the Northern Territory and Western Australia generally, compared to the rest of Australia. Other health professionals, particularly dentists and some allied health professionals were also unevenly distributed. Nurses, on the other hand, were relatively evenly distributed across Australia. The Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification structure is the current basis for the allocation of incentives to encourage doctors to practise in rural and remote Australia. RRMA is based on 1991 population Census data and is widely regarded by stakeholders as ‘antiquated' and unsuitable6. The Minister for Health and Ageing announced in April 2008 that all geographical classification systems would be reviewed as part of an overall review of all rural health programs. The department is currently undertaking this review and will provide the outcomes to the Minister for consideration.

Supply of health professionals by geographic region

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) as the foundation for its spatial statistical collection. The ASGC consists of the following geographic regions—Major City, Inner Regional, Outer Regional and Remote/Very Remote. The ASGC is routinely updated to take account of population dispersion and the provision of services. One of ASGC's strengths is that it is the basis of many national statistical collections where geographical location is an important determinant.

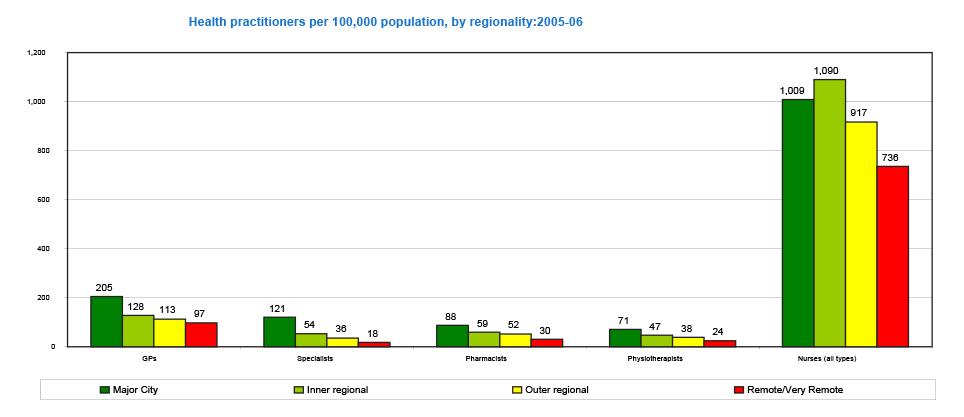

Figure 1 illustrates the variation in health professional supply across Australia's geographic regions.

Figure 1: Health professionals by remoteness category

Source: Most recent data on the distribution of health professionals provided by the Department of Health and Ageing to the 2020 Summit, 2008.

Since 1994, governments have responded to the challenges of health workforce shortages and their uneven distribution through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). In particular, following COAG endorsement in 2006 of the Productivity Commission recommendations into Australia's health workforce, there was a renewed national effort through peak inter-governmental Ministerial Councils to resolve systemic supply and demand issues concerned with the adequate supply and distribution of health professionals, including in rural and remote Australia.

The Australian Government and its health and ageing administration agency, DoHA, have a substantial and pivotal leadership role in ensuring that Australians, including in rural and remote Australia, have access to a supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector. DoHA administers around 60 programs directed at workforce distribution, health service delivery, and contributing to the education and training of health professionals in rural and remote Australia.

DoHA's programs directed at workforce distribution contribute to a number of Outcomes which are reported in the Health Portfolio Budget Statements, and which directly impact on the supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector, including in rural and remote Australia. The principal Outcome group is Outcome 12: Health Workforce Capacity. DoHA's Mental Health and Workforce Division (MHWD) has responsibility for this outcome.

In 2007, the Minister for Finance and Deregulation announced a set of reforms to improve the transparency of government financial information. The reforms focus on improvements in agency Portfolio Budget Statements so that they are relevant, strategic and are performance oriented. The intention was to ensure that readers of Portfolio Budget Statements have a clear and transparent account of an agency's planned performance for the Budget year and the resources to be used.

It is against this background, that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) audited the effectiveness of DoHA's administration of health workforce initiatives in rural and remote Australia.

Audit scope and objective

Audit objective

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing's administration of health workforce initiatives in rural and remote Australia.

Audit criteria

To form its opinion, the ANAO used the following criteria:

- DoHA has strategies in place to maximise its contribution to the Australian Government's specified Health Workforce Capacity outcome;

- DoHA has effectively implemented Australian Government programs addressing health workforce shortages in rural and remote Australia; and

- DoHA monitors and evaluates its health workforce programs for rural and remote Australia.

Audit scope

The audit focuses on the effectiveness of initiatives for the primary care health workforce in rural and remote areas. The audit scope concentrates on DOHA's responsibility for health workforce distribution and its limited responsibility for health workforce education and training. The audit scope did not include the administrative role of State and Territory Governments and the Indigenous health workforce.

Audit methodology

To gain a suitable understanding of the broader environment in which DoHA is delivering the Government's objective concerning health workforce capacity in rural and remote Australia and to identify the primary issues and evidence necessary to support an audit conclusion, the ANAO used the following evidence–gathering techniques: an analysis of key planning, policy and program documents; interviews with departmental staff and stakeholders; an in–depth analysis of eight rural and remote health workforce capacity programs; and a stakeholder survey.

Rural and remote health workforce capacity programs

In deciding which programs to examine in more detail, the ANAO, after consultation with the Mental Health and Workforce Division, the Primary and Ambulatory Care Division and the Aged Care Division, selected eight programs. The programs selected reflect the department's specific areas of responsibility for the health workforce in rural and remote Australia outlined above, and included:

- seven rural and remote health workforce capacity programs, almost all of which are distribution initiatives; and

- one health service delivery program with a health workforce capacity component—the Medical Specialists' Outreach Assistance Program (MSOAP).

While the programs represent a cross section of rural and remote activities and the results of the program analysis are indicative of DoHA's approach, the sample of programs was not designed to provide statistically significant results and the data obtained from the program analysis cannot be extrapolated to all health workforce capacity and health service delivery programs.

Stakeholder Survey

The delivery of the department's rural and remote health workforce capacity programs are outsourced to organisations in the health sector that have on-the-ground experience with health care arrangements in rural and remote areas of Australia.

The ANAO undertook a survey of external organisations, nominated by the MHWD as stakeholders. The ANAO invited 168 stakeholder organisations to participate in the on–line survey. Of the 168 stakeholder organisations approached, 126 responded to the survey. This equates to a high response rate of 75 per cent.

As one of the key inputs to the audit, the ANAO obtained feedback from a broad range of stakeholders regarding their opinion of how well they considered that the department had:

- engaged with stakeholders to inform policy advice and program delivery;

- delivered programs addressing health workforce shortages in rural and remote Australia and managed the performance of service providers; and

- evaluated and improved rural and remote health workforce capacity programs.

The opinions of stakeholders are an important complementary input to the audit, as these stakeholder organisations are well placed to provide a perspective on DoHA's administrative performance and engagement of stakeholders. Of those stakeholders that responded to the ANAO survey, 71 per cent deliver rural and remote health workforce capacity programs under contract with DoHA.

Conclusion

The availability and quality of health care services across Australia is contingent upon the supply and distribution of health professionals. Over the last decade, Australia has experienced workforce shortages in a number of health professions, particularly in rural and remote regions. The ongoing shortage of doctors and nurses in these areas of the country has many characteristics in common with difficult social policy issues – it is multi-causal with many interdependencies, has no clear or definitive solution, is not the responsibility of any one jurisdiction and, ultimately, requires health professionals to move to, or work for a longer period in, a rural and remote area.

To ensure that Australia's health workforce has sufficient numbers of high quality doctors, nurses and allied health professionals to meet the health service needs of the community, the Australian Government created a specific Health Workforce Capacity outcome in DoHA in 2006. The health workforce statement adopted for DoHA's Outcome 12 is: Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce. Within this Outcome, the aim of the department's health workforce programs in rural and remote Australia has been to increase the number of doctors and nurses working in general practice. The broader, aspirational nature of DoHA's Outcome 12 recognises that rural and remote health workforce capacity is a subset of a much larger health workforce capacity issue and while it is important to give attention to the issue of the rural and remote health workforce, it cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader context.

In pursuing Outcome 12, DoHA works in an environment where its programs provide only part of the total funding for health workforce initiatives. Its advice on policy options requires it to work with a range of entities, including the States and Territories, in order to maintain an overall picture of the national health workforce. In this challenging administrative environment, DoHA has key roles in influencing the achievement of the intended outcome, implementing policies and programs that take into account the operation and coverage of existing initiatives, measuring the progress being made via the Australian Government programs it administers, and providing advice to Ministers on any further measures or initiatives needed to improve access to an enhanced health workforce.

In this context, DoHA's approach to address health workforce issues in rural and remote Australia in a strategic way requires a clear appreciation of: the overall context, DoHA's particular role, and how the department's contribution to improving the situation will be measured and assessed. Such an approach would be expected to be underpinned and informed by: the identification, treatment and monitoring of the risks in DoHA's operating environment that affect the success of the department's programs; the measurement and tracking of the impact and ongoing relevance of the health workforce programs implemented by the department; and appropriate data on health care needs and health workforce capacity.

While DoHA has put in place structural arrangements to administer its direct program delivery responsibilities, the department has not yet developed a cohesive approach to inform its strategies and to report on its contribution to health workforce outcomes in rural and remote areas of Australia. The department's ability to set organisational strategies to achieve the outcome being sought: Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce in rural and remote areas of Australia has been hindered by:

- limited monitoring of key risks identified by DoHA, particularly: insufficient supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector;

- DoHA's lack of a performance information strategy to inform government and the Parliament about the quality of the health workforce and its distribution across rural and remote Australia, and the level of access to health services by Australian citizens in rural and remote areas; and

- the use of old and unsuitable Census data and geographic classification systems as the basis for providing incentives to health professionals to work in rural and remote areas of Australia.

Over the past year there has been considerable activity in other jurisdictions and within DoHA directed at improving health workforce capacity in rural and remote Australia. In April 2008, the Minister for Health and Ageing announced that there would be a review of all targeted Australian Government programs in rural and remote Australia and that all geographic classification systems would be reviewed. In July 2008, DoHA re-established the Office of Rural Health. And in November 2008, COAG agreed to a significant health workforce package of $1.6 billion underwritten by the Commonwealth. These developments underline the importance of DoHA taking steps to improve its approach to managing and reporting on its contribution to health workforce outcomes in rural and remote areas of Australia.

Monitoring and managing key risks

The department has appropriately recognised the importance of performance information and identified inadequate knowledge and information management as a key risk affecting its ability to deliver against Outcome 12. This risk has materialised and there is a significant shortfall in information on the status and trends concerning the health workforce in rural and remote Australia. Until this risk is ameliorated, lack of information on the health workforce at the national level will continue to be a significant hindrance to the effective administration of rural and remote health workforce capacity programs managed by DoHA as well as the capacity of DoHA to provide evidence-based policy advice to government. DoHA's ability to manage this risk would benefit from a more active approach to monitoring the key risks identified by the department including at the program level.

Adopting a performance information strategy

DoHA manages many, relatively small health workforce programs and it is often difficult to monitor and assess their contribution to the broader outcome or gauge their relationship with similar or complementary programs both within the department and in other agencies. Performance monitoring and evaluation are complementary elements of a sound performance information strategy that can be used to provide a picture of program performance so that, over time, a better understanding of the critical success factors is developed.

Currently, DoHA's performance measures for Outcome 12 focus on outputs, and the department reports on the number of student scholarships provided and the number of nurses re-entering the workforce. These measures are not sufficient to capture the intended impact of this outcome. At the program level, the emphasis placed on evaluation varied across the rural and remote health workforce programs examined by the ANAO and the frequency and nature of the evaluations undertaken was not co-ordinated.

For DoHA to be in a position to determine its contribution to the outcome, it should develop and make use of appropriate effectiveness indicators and an evaluation strategy. A strategic approach to program evaluation would, in particular, enable DoHA to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the performance of its rural and remote health workforce programs, collect and analyse more comprehensive data, focus on key performance indicators and enable clearer identification of the causal links between program outputs and achieving the desired outcome. The combined use of effectiveness indicators and an evaluation strategy would assist DoHA, over time, to better assess the achievement of selected programs against a set of higher level outcomes, even when more than one agency is influencing the results, and to make judgements about the continued appropriateness of the programs the department administers or suitable amalgamations of programs.

When considering effectiveness, it is useful to take into account the perspectives of a range of stakeholders or to seek their views. Of the 126 organisations which responded to the ANAO Stakeholder Survey, 89 (71 per cent) deliver rural and remote health workforce capacity programs under contract to DoHA. While stakeholders are likely to make judgements based on their perceptions, the attitudes of stakeholders can also have a significant impact on the success of policy and program delivery. DoHA's capability to use and build on its experience in implementing health workforce policy and programs in rural and remote Australia could be enhanced by improving the quality of the health workforce information gathered from stakeholders and by better using this information to inform policy and program approaches.

Use of appropriate and up-to-date data

DoHA relies on a number of data sets to inform its policy advising and program management responsibilities. Programs involving incentive payments to doctors to practise in rural and remote Australia are linked to two classification structures: the Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification structure, which uses 1991 Census data; and the General Practitioner Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (GPARIA) classification which was last updated in 2001. Because of their age, these classification structures have been increasingly questioned by stakeholders (including the current Minister for Health and Ageing) as suitable instruments to determine incentives for doctors who practise in rural and remote areas.

As these data sets become less relevant, the risk of producing outcomes which are inconsistent with the policy goal of Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce increases. DoHA recognised these anomalies when it conducted a review of RRMA for the then Minister for Health and Ageing in 2005. In April 2008, the Minister for Health and Ageing announced a review of all remoteness classification systems to ensure that incentives and rural health policies respond to current population figures and need.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made three recommendations designed to improve DoHA's capability to respond to the risks identified, especially the lack of accurate information on the status of health services across rural and remote Australia; to monitor and evaluate the department's relatively large number of small programs using a performance information strategy; and to obtain appropriate and up-to-date data to better inform program delivery and policy advice, including the use of feedback from key stakeholders that deliver the department's rural and remote programs. Adopting these recommendations will assist DoHA to guide, manage and report on its contribution to the Australian Government's health workforce capacity outcome.

Key findings by Chapter

Chapter 3—DoHA Strategies for Health Workforce Capacity in Rural and Remote Australia

The ANAO examined the strategies that DoHA has in place at the enterprise and Divisional levels to improve health workforce capacity in rural and remote Australia.

Strategies at the enterprise level

Key aspects of strategic planning include appropriate attention to:

• enterprise risks; and

• performance information.

DoHA's risk management framework includes an Enterprise Risk Management Plan (ERMP). The ERMP identifies those enterprise level risks that may have an adverse impact on the department's ability to achieve the outcomes set out in its Portfolio Budget Statements and/or other corporate objectives. The ERMP includes one of its key risks as: insufficient supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector.

While this is a national risk, internally, DoHA allocated its treatment to the department's Mental Health and Workforce Division (MHWD). Notwithstanding DoHA's active approach to identifying the obstacles to a sufficient supply of adequately trained personnel in Australia's health sector, the ANAO found that the department had not monitored the effectiveness of the treatments put in place by the MHWD to ameliorate the inherent risks. There was, for example, no provision to monitor and report on progress being made over time and to provide DoHA's Executive with the information necessary to make informed decisions as to whether enterprise risk treatments were adequate and being appropriately progressed.

More broadly, the resolution of the health workforce risks identified by DoHA requires the department to work collaboratively with a range of bodies including departments of health in the States and Territories. While DoHA recognised this context, the department had not monitored the effectiveness of the treatments it put in place concerning collaboration with other jurisdictions. Given the complexity of the problem and the numerous stakeholders involved, a more rigorous approach to risk management is required. In particular, the use of oversight and monitoring arrangements to allow for regular assessments of the status of the overall risk identified by DoHA, that is, insufficient supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector, and whether the actions being taken by DoHA were effective or alternative approaches were needed, appropriate to the department's level of responsibility and control.

DoHA's Corporate Plan 2006–09 has a high level Performance Information Framework that was designed to guide the development of performance information management arrangements in lower level business plans. In the preamble to the Corporate Plan, DoHA's Secretary notes that to achieve the direction outlined in the Plan, team leaders and staff can only genuinely contribute when they have a direct ‘line of sight' from their own work through to the department's priorities, values and responsibilities.

While DoHA has an overarching framework in place, through its Corporate Plan, to assist business groups to manage risks likely to impact on the achievement of business objectives, a challenge in any large organisation is maintaining ongoing alignment between corporate strategies, business plans and individual programs. Nevertheless, such alignment is influential in ensuring that the strategies adopted by an organisation to manage its risks, to undertake its planning, and to monitor and report on its performance are integrated at all levels.7

Strategies at the Divisional level

DoHA's Risk Management Policy advises that:

risk management principles are to be applied and integrated into all the Department's strategic planning, business planning, policy development, program delivery, project management, grant management, procurement, service/product delivery, and all other decision making.8

DoHA's MHWD is responsible for Outcome 12 and is the risk owner of the high–level enterprise risk identified in the ERMP: insufficient supply of adequately trained personnel to work in the health sector.

The MHWD's Risk Management Plan (incorporated in the Business Plan) identifies six risks, including the following three which relate to health workforce capacity:

• inability to deliver Government priorities and expected outcomes;

• inadequate knowledge and information management; and

• ineffective client/stakeholder management.9

MHWD manages a number of programs ‘from a range of Outcomes in the Portfolio Budget Statements'. The department's current management strategies do not take into account the risks involved in designing, managing and reporting the department's cross portfolio activities in the area of rural and remote health workforce capacity. This increases the risk of program overlap and duplication and program objectives not being sufficiently aligned.

The MHWD has two program areas: Program 12.1—rural health workforce and Program 12.2—health workforce (general). In addition, the Division administers workforce distribution, and education and training programs ‘from a range of Outcomes in the Portfolio Budget Statements'.10 Each of these programs has an annual budget and there is clarity around the program description and objective. In a complex environment where a number of departmental Outcome groups are involved in achieving a stated government Outcome such as Outcome 12: Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce, a structured approach to managing performance across the relevant Outcome groups is required.

The ANAO reviewed performance information in the Health and Ageing 2008–09 Portfolio Budget Statements and found that there were no effectiveness indicators in place for Outcome 12 or for the other relevant Outcome groups—2, 3, 5, 6, and 8—where the MHWD has responsibility for co-ordinating, planning and managing rural and remote health workforce capacity programs. The performance measures that DoHA has in place focus on outputs, for example, the number of student scholarships provided and the number of nurses re-entering the workforce. These measures do not capture the intended impact of Outcome 12.

When determining an appropriate set of effectiveness indicators, an important contextual consideration is that Australia's health workforce environment is characterised by programs that cut across jurisdictions, departments and divisions within the department.

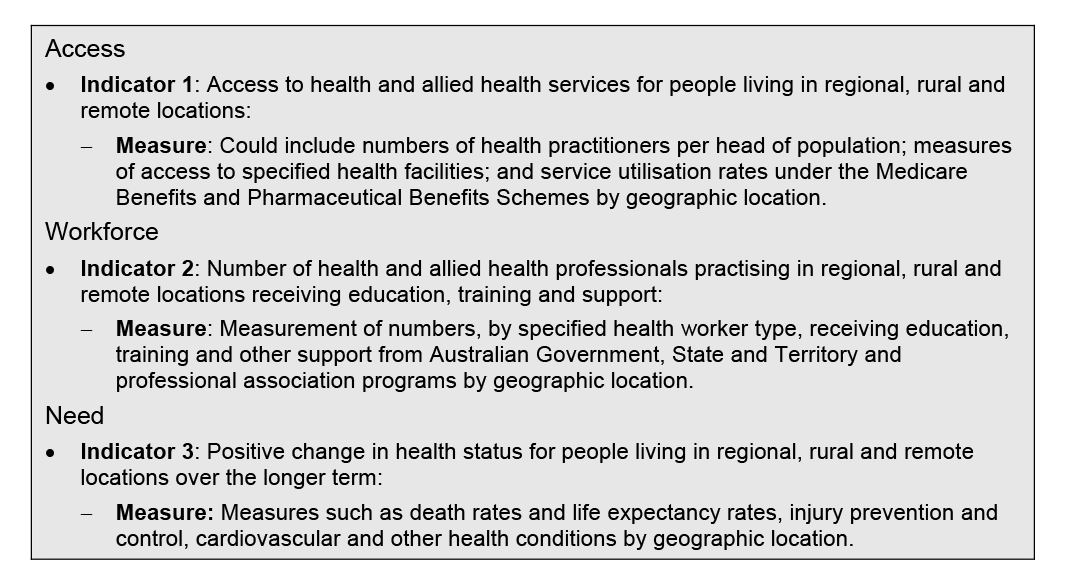

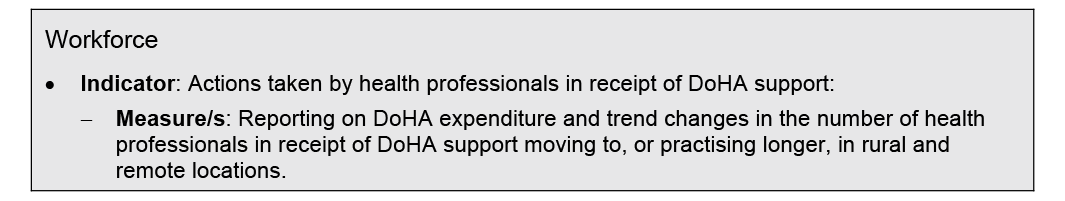

Useful contextual indicators would include information on trends over time that relate to the area targeted by DoHA's Outcome 12. These could include trends in the utilisation of Medicare benefits by geographic region (access), trends in the number and type of health professionals by region (workforce), and trends in diseases by region (need). Such ‘gross' trends, however, will not necessarily represent DoHA's contribution to the outcome.

More specific indicators of ‘net' effectiveness are required to draw out the positive contributions made by DoHA, filtering out the impact of other influences. Regular surveys could be used as an indicator of whether health professionals had moved to or practised longer in rural and remote areas and could identify the factors that influenced changes.

In this context, to report on the effectiveness of the contribution of its outputs and/or administered items to: Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce; DoHA could use or adapt the following measures, which enable stakeholders to understand DoHA's contribution within the context of the broader outcome.

Context/trend indicators

Specific DoHA effectiveness measure for rural and remote health workforce capacity

Chapter 4—Program Implementation

The department's MHWD manages around 35 rural and remote health workforce capacity programs. In addition to these programs, other divisions manage a number of health workforce capacity programs—such as the Office of Aged Care; and rural and remote health service delivery programs—such as the Primary and Ambulatory Care Division.

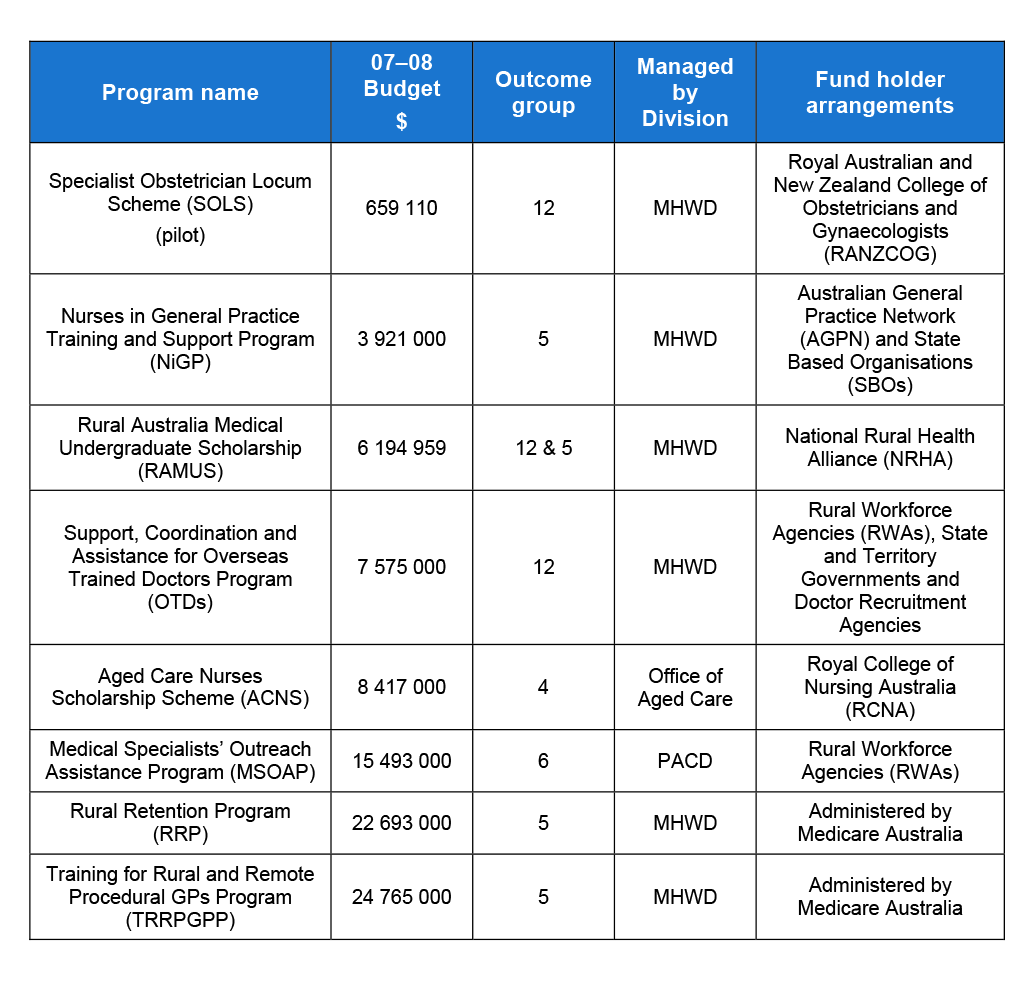

The ANAO selected, in consultation with DoHA, eight programs to examine in detail. The selection included health workforce education and training programs, workforce distribution programs and a health service delivery program with a workforce component. Table 1 lists the eight programs (including one pilot) selected.

Table 1: Selected rural and remote health workforce capacity programs

Source: ANAO.

Note: Mental Health and Workforce Division (MHWD) and Primary and Ambulatory Care Division (PACD).

Successful program implementation is characterised by the following features:

• business planning processes to identify and treat program risks; and

• the planning and collection of program level performance information

Risk management

Risk management is applicable to all levels in an organisation: at the enterprise level, the Divisional level, and at the program level. Alignment between these levels helps to ensure that strategic and operational risks are managed consistently.

Integrating risk management into the governance, planning and management processes within an agency provides purpose in applying the risk management process and relates risk back to the agency's core business.11 When integrating risk management, it is important to consider an agency's operating environment and, through deliberate planning, consider how risk management processes can be embedded into management activities such as business planning, decision making and reporting.12

Program level risks

As with any major departmental initiative, coordination of risk planning and management activities across a department is important. The involvement of staff from DoHA's program areas in identifying, monitoring and treating program risks that are important in managing broader exposures is vital to department-wide coordination and lays the foundation for effective risk management.

The ANAO assessed program risk management arrangements for each of the eight programs identified in Table 1. The risk management criteria were: link to Enterprise Risks; link to MHWD risks; risk context established; risks identified; risks analysed; risks evaluated; risks treated; risks monitored and reviewed.

ANAO analysis demonstrates that the eight rural and remote health workforce capacity programs do not place an equal emphasis on risk management. None of the eight programs demonstrated clear links to DoHA's enterprise risk concerning health workforce supply. As well, no clear links were articulated against MHWD risks. It needs to be noted that two programs—the Aged Care Nurses Scholarship Scheme (ACNS) and the Medical Specialists' Outreach Assistance Program (MSOAP) are delivered by other Divisions within DoHA.

Program performance information

Increasingly, performance information is being used to measure the success or otherwise of government programs. Performance measurement is characterised by ongoing and regular tracking of activities, outputs and while difficult, the contribution of the program to broader outcomes.

Performance information includes both quantitative and qualitative measurement and assessment. Such information is often readily available at the output level (i.e. the specific goods and services delivered by the program). However, as agencies seek to assess and track the impact of these goods and services being delivered to the community, information on the contribution of the program to intermediate and final outcomes becomes important.

The ANAO assessed program performance information management arrangements for each of the eight programs identified in Table 1. The program performance information management criteria were: link between programs and DoHA outcomes; link to similar or complementary programs; clear and measurable program objectives; mix of performance indicators; continuous improvement; monitoring and reporting systems; and quality data underpinning performance indicators.

ANAO analysis demonstrates that the eight rural and remote health workforce capacity programs do not place an equal emphasis on performance information management. While all programs were mentioned in recent Portfolio Budget Statements (PB Statements), not all programs were able to demonstrate clear links to these higher level outcomes. Two of the eight programs—RAMUS and NiGP—were able to demonstrate clear links to higher level DoHA outcomes. This was because these programs had effectiveness indicators in place which were able to demonstrate program contributions to the higher level outcome sought by government. However, no program was able to demonstrate clear links with similar or complementary programs.

Performance management should be a key feature underpinning all of DoHA's rural and remote health workforce capacity programs. The main findings in relation to DoHA's performance information management are:

-

the lack of alignment between program performance information and higher level performance information required by DoHA to allow the department to track and report on the achievement of government outcomes; and

-

there is little indication that rural and remote health workforce capacity programs are compared with similar or complementary programs within DoHA, other Australian Government departments or with other jurisdictions.

Chapter 5—Information for Policy and Program Advice

DoHA has a two fold responsibility. As the principal agency charged with achieving the Government's priorities (outcomes) concerning the health care and ageing needs of all Australians, one of its core activities is to provide quality, relevant and timely advice for Australian Government decision–making. Secondly, it is responsible for producing relevant and timely evidence–based policy research to support its advisory function.13

The department's MHWD Risk Management Plan identified six business risks including the risk most relevant to information for policy and program advice: inadequate knowledge and information management.

Health workforce data

To assess the appropriateness of representative14 data for policy and program advising purposes, the ANAO examined the tertiary data sources used by DoHA, including the quality of the sourced data. The tertiary data sources examined include:

- Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification;

- General Practitioner Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (GPARIA) classification;

- the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)—Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC); and

- proposals for a National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) for a number of health professions.

Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA)

DoHA is currently reliant on the Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification as an eligibility criterion for many of its programs and related incentives. The RRMA classification was developed in 1994 as a remoteness classification based on 1991 population Census data.

DoHA recognised these anomalies when it conducted a review of RRMA for the then Minister for Health and Ageing in 2005:

the accuracy and appropriateness of RRMA as a classification system has been increasingly questioned by stakeholders. The needs and characteristics of many regions throughout Australia have changed, and as RRMA has not been officially updated, it has not kept pace with these changes. It no longer accurately measures health or other need.15

General Practitioner Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (GPARIA)

The General Practitioner Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (GPARIA) was developed specifically for the Rural Retention Program (RRP) which commenced in 1998. The objective of the RRP is to encourage GPs to stay longer in targeted rural and remote locations through the provision of financial incentives.

Because of their age, the suitability of the RRMA and GPARIA classification structures, as instruments on which to base the incentives that doctors who practise in rural and remote areas currently receive, is deteriorating.

In April 2008, the Minister for Health and Ageing announced a review of all remoteness classification systems as part of the overall review of all rural health programs. The review is currently being undertaken by the department.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)—Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC)

The ABS developed the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) remoteness structure as a system that classifies Australia into five areas according to their relative remoteness and is now reported routinely by ABS, for many national collections, including in reports produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

It is important that DoHA uses sound evidence to inform its policy advising function concerning incentives for doctors in rural and remote Australia.16

Proposals for a National Registration and Accreditation Scheme

COAG signed an Intergovernmental Agreement in 2008 for a National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) to register and accredit ten health professions: medical practitioners, nurses and midwives, pharmacists, physiotherapists, psychologists, osteopaths, chiropractors, optometrists and dentists.

NRAS will maintain a public health register for each health profession. A secondary benefit of the national scheme is the requirement for a national collection of health workforce data. The NRAS data will assist with national workforce planning and evaluation of national progress against health workforce priorities. However, this is subject to agreement by Health Ministers.

Opinion–based data sources

As one of the key inputs to the audit, the ANAO obtained feedback from a broad range of stakeholders regarding their opinion of how well they considered that DoHA has engaged with stakeholders to inform policy advice and program delivery. One hundred and twenty six stakeholder organisations17 responded to the ANAO stakeholder survey. Of those that expressed an opinion on these particular issues18:

- one-third were of the view that, overall, DoHA effectively consults stakeholders in relation to policy issues; and

- approximately half (48 per cent) were of the opinion that, overall, DoHA effectively consults stakeholders in relation to program delivery issues.

When considering effectiveness, it is useful to take into account the perspectives of a range of stakeholders or to seek their views. While stakeholders are likely to make judgements based on their perceptions, the attitudes of stakeholders can have a significant impact on the success of policy and program delivery. DoHA's capability to use and build on its experience in implementing health workforce policy and programs in rural and remote Australia could be enhanced by:

- improving the quality of the health workforce information gathered; and

- better use of this information to inform policy and program approaches.

Chapter 6—Evaluation and Continuous Improvement

Program evaluation and performance information are complementary tools for program management. Evaluations can provide an invaluable perspective on program performance, especially over a number of years. In contrast, performance indicators provide information for day-to-day management.

While program evaluation is not a requirement of the Outcomes and Outputs framework, the Productivity Commission has identified the importance of evaluations in providing an evidence base to underpin reform processes. The Productivity Commission also suggests that the lack of evaluation activity makes it difficult to comment on the effectiveness or otherwise of government interventions.19 Evaluations can assist managers and other decision–makers to: assess the continued relevance and priority of program objectives in the light of current circumstances, including government policy changes; test whether the program is achieving its stated objectives; ascertain whether there are better ways of achieving these objectives; assess the case for the establishment of new programs, or extensions to existing programs; and decide whether the resources for the program should be continued at current levels, be increased, reduced or discontinued. Evaluations also have the capacity to establish causal links. Over time, an evaluation strategy has the potential to provide credible, timely and objective findings, conclusions and recommendations to aid in resource allocation, program improvement and program accountability.

The ANAO assessed program evaluation management arrangements for each of the eight programs identified in Table 1. The evaluation management criteria were: link to DoHA outcomes; link to an evaluation strategy; lessons learned; contribution to outcome achievement; clear contribution to higher level outcomes; prior evaluations; and robust and appropriate evaluation methodology.

ANAO analysis demonstrates that the eight rural and remote health workforce capacity programs do not place an equal emphasis on evaluation management.

While all programs were mentioned in recent Portfolio Budget Statements (PB Statements), not all programs were able to demonstrate clear links to these higher level outcomes. As discussed in Chapter 4 on program performance information management, two of the eight programs—RAMUS and NiGP—were able to demonstrate clear links to higher level DoHA outcomes. This was because these programs had effectiveness indicators in place which were able to demonstrate program contributions to the higher level outcome sought by Government. The lack of program effectiveness indicators also impacts on an agency's capacity to evaluate programs to provide assurance that programs remain relevant in the context of government outcomes.

None of the eight programs were able to demonstrate a clear link to an evaluation strategy. A strategy would assist DoHA to evaluate the contribution of its health workforce capacity programs to the department's Outcome 12: Australians have access to an enhanced health workforce and, where appropriate, other relevant DoHA outcomes.

DoHA administers around 60 programs directed at workforce distribution, health service delivery, and contributing to the education and training of health professionals in rural and remote Australia. In addition, there are a number of health workforce and health service programs being individually delivered by State and Territory Governments. In this context, an evaluation strategy would enable DoHA to identify program interdependencies and the contribution of individual programs (both internal and external) to the national health workforce objective. An evaluation strategy would also ensure value for money by targeting DoHA evaluation work in this regard.

DoHA recognises the importance of program evaluation and advised the ANAO that during its review of all targeted, Australian Government funded rural health programs, the department will consider the parameters of evaluation strategies for existing rural and remote workforce initiatives.

Continuous improvement

DoHA operates in an environment of continuous improvement where the importance of using ‘lessons learned' is well recognised within internal templates, strategies and accountability documents that guide staff within the organisation.20 However, DoHA had not adopted a consistent approach to monitoring and improving its health workforce program performance through adopting ‘lessons learned' from evaluations. A ‘lessons learned' approach would allow program managers and the department to identify and consider the presumed causal links between health workforce capacity program inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes, and to improve overall performance.

Summary of agency response

Health workforce capacity is complex with a range of organisations involved including:

- jurisdictions that are the major employers of the health workforce;

- State and Territory registration boards that register a number of professions;

- universities and the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) sector that educate health workers; and

- the department, whose main areas of focus have been on the distribution of general practitioners, funding of some specific rural and remote health services, and some training and education of the health workforce in respect of some known skills shortages.

The department works to improve health workforce capacity within the framework.

The department agrees with and has undertaken activities that address the three recommendations made by the ANAO in this report. As stated in the report there is considerable activity already underway, much of which has been underway for some time directed at sustainable improvement in health workforce capacity in rural and remote Australia.

COAG announced a significant health workforce package underwritten by the Commonwealth including a National Health Workforce Statistical Register at its 29 November 2008 meeting. In addition, the Office of Rural Health has commenced a review of all targeted Commonwealth funded rural health programs. The review was announced by the Minister in April 2008 when she released the department's Report of the Audit of Health Workforce in Rural and Regional Australia.

The COAG package involves a fundamental change in the way clinical training for health professionals is provided, includes some significant investment in workforce planning data and includes measures that will have a positive impact on the number of health professionals. The Commonwealth took the lead with this package and the department undertook a significant piece of work over a long period of time in consultation with jurisdictions to make this happen.

The department is working with the Department of Finance and Deregulation to develop the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) under the reforms established by the Government to ensure that the PBS are relevant, strategic and performance focused. The ANAO have noted the complex environment the department operates in and has demonstrated how this impacts on the ability to develop performance measures that take out all other influences. The department will review its performance indicators for health workforce in that context.

Footnotes

[1] The Australian Constitution, s.51 (xxiiiA).

[2] Department of Health and Aged Care, Financing and Analysis Branch, September 2000, The Australian Health Care System: an outline, p. 1-2.

[3] Productivity Commission, 2005, Australia's Health Workforce, p. 51.

[4] ibid.

[5] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2007, Year Book Australia.

[6] Minister for Health and Ageing, April 2008, Press Release—Report of the Audit of Health Workforce in Rural and Regional Australia and the ANAO Stakeholder Survey.

[7] This approach also helps to support integration between the outcomes being sought and the design and performance of individual programs. ANAO analysis, on the degree of integration between DoHA's corporate/ business level controls and their alignment with its rural and remote programs can be found at paragraph 71 in the report. Overall, the ANAO found that two of the eight programs that were examined in more detail as part of the audit were able to demonstrate clear links to higher level DoHA outcomes.

[8] Department of Health and Ageing, 2005, Risk Management Policy.

[9] Mental Health and Workforce Division, 2007–08, Business Plan.

[10] These Outcome groups include: Outcome 2—Access to Pharmaceutical Services; Outcome 3—Access to Medical Services; Outcome 5—Primary Care; Outcome 6—Rural Health; and Outcome 8—Indigenous Health.

[11] Comcover, June 2008, Better Practice Guide, Risk Management, p. 20.

[12] ibid, p. 28.

[13] Health and Ageing portfolio, 2008–09, Portfolio Budget Statements.

[14] Data that is deemed to be representative is accurate, reliable, reflects current realities and representations of real world facts.

[15] DoHA, 2005, Review of RRMA (unpublished).

[16] The Minister for Health and Ageing, Media Release, 30 April 2008.

[17] The sample of stakeholder organisations included: deliverers of rural and remote health workforce programs on behalf of DoHA; Divisions of General Practice; education and/or training providers; peak/representative groups other than Divisions of General Practice; Medical Colleges or health professional associations; research organisations; and Rural Workforce Agencies (RWAs).

[18] Stakeholders were excluded who did not respond to the particular question or who indicated that they ‘neither agreed nor disagreed' with the statement. Less than 16 per cent of respondents were excluded on this basis.

[19] Gary Banks, Productivity Commission, February 2009, Challenges of evidence-based Policy Making.

[20] DoHA, Policy Formulation and advice – advanced Version 3, p. 177.