Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Risk Management in the Processing of Sea and Air Cargo Imports

The objective of the audit was to assess Customs and Border Protection’s use of risk management to assist in the processing of sea and air cargo imports.

Summary

Introduction

1. Australia’s border is a complex environment. The majority of people and goods entering and leaving the country pose no threat. However, the entry of some people and goods into Australia do present risks. These can take the form of major threats– such as those posed by the entry of terrorists and illicit drugs– to more moderate threats such as the non payment of customs duty and the importation of restricted goods without the appropriate permit.1

2. Working closely with other government and intelligence agencies, the role of the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs and Border Protection) is to facilitate legitimate trade and travel while seeking to identify and target those people and goods that present a risk of contravening the laws designed to protect our borders. It is also responsible for collecting customs duty and border-related taxes and charges, which totalled $9.6 billion in 2010–11.2 As at 30 June 2011, Customs and Border Protection employed 5 674 staff in Australia and overseas, supported by surveillance and intelligence systems.

The import process

3. All cargo3 arriving in Australia is subject to customs control and cannot be released into ‘home consumption’ without Customs and Border Protection’s permission.4 All those involved in the importation of cargo are required by law to provide Customs and Border Protection with a variety of reports prior to, at, and following the arrival of the aircraft or vessel and the actual importation of the cargo.5 Cargo reports, which include a description of the cargo, must be input electronically into Customs and Border Protection’s Integrated Cargo System (ICS) not less than 48 hours before arrival for sea cargo, and not less than two hours for air cargo. This allows Customs and Border Protection to commence risk assessing the cargo before it has actually arrived.

4. A formal declaration relating to the cargo can be made by the owner, including an importer or a broker on their behalf, by providing either a Self Assessed Clearance (SAC) Declaration (for consignments with a value of $1 000 or less) or a Full Import Declaration (FID). These declarations provide additional information about the cargo and may either be given a ‘held’ status if Customs and Border Protection wish to obtain more information or examine the cargo, or a ‘clear’ status. Cargo that receives a ‘clear’ status can be released once all customs duty and border-related taxes and charges have been paid. In 2010–11, there were 13.9 million air and 2.3 million sea cargo consignments reported.

Customs and Border Protection’s Regulatory Philosophy

5. Customs and Border Protection’s Regulatory Philosophy recognises that the majority of individuals and entities involved in the importation of cargo intend to comply with regulatory requirements and should be permitted to operate in a self assessed environment with minimal or no intervention. It recognises that there is a compliance continuum ranging from importers who comply with border related legislative requirements, through to those who inadvertently fail to comply, to serious criminals who actively seek to evade border controls. Thus, Customs and Border Protection measures its success in terms of the proportion of cargo that passes unimpeded through the import process as well as the number and type of prohibited or restricted goods detected and revenue collected.6

6. Customs and Border Protection describes its approach to managing the flow of sea and air cargo imports as ‘intelligence-led and risk-based’. This approach is aimed at assessing the risks that prohibited or restricted goods present at the border, and designing ways to treat these risks that are commensurate with the level of the risk and the resources available.

Customs and Border Protection’s risk management framework

7. In the Customs and Border Protection context, risks primarily relate to protecting Australia from the unauthorised entry of prohibited and restricted goods.7 Prohibited goods such as illicit drugs and terrorism related goods pose the highest risks and the appropriate treatment is to detect them in the cargo stream and intercept them at the border, so that they do not enter the country. The importation of some other prohibited and restricted goods, and the short payment of customs duty present a lower level of risk to the community and can reasonably be dealt with at the border or after importation.8

8. Customs and Border Protection’s border management approach is ‘intelligence led and risk based’. This means using intelligence led risk management processes, including advanced analytical techniques and tools, that allow Customs and Border Protection to focus on high risk goods. In simple terms, risks are assessed according to the likelihood of an event occurring (such as the undetected importation of illicit drugs) and the severity of the consequence if the event occurs. Consistent with the international standard, Customs and Border Protection uses risk matrices to categorise the risks it has identified. This assessment is important in determining the level of resources to be applied to risk mitigation strategies aimed at preventing, deterring, detecting and disrupting the movement of prohibited and restricted goods across the border. Within Customs and Border Protection, risks are assessed and managed at three levels: strategic, operational and tactical.

9. Strategic risks are the high level, whole of agency border risks articulated in Customs and Border Protection’s Annual Plan and Annual Risk Plan, as well as the Government’s broader Strategic Border Management Plan. These risks are: terrorism; the unauthorised or irregular movement of people; biosecurity threats; the movement of prohibited and restricted goods; unlawful activity in the maritime zone; and the non payment of border related revenue (customs duty, taxes and charges).

10. After strategic risks have been identified and risk mitigation strategies developed,9 the implementation of these strategies is undertaken at the operational level through the Cargo Intervention Strategy (CIS) and the application of the Differentiated Risk Response Model (DRRM). At the border, profiles and alerts are the tactical risk management tools used to identify at risk consignments for inspection and examination.

Identifying high risk air and sea cargo imports

11. Profiles identify broad risks or sets of risk indicators and are based on intelligence either developed within Customs and Border Protection or passed to it by other agencies such as the Australian Federal Police. Alerts are entity specific but are also generally intelligence–based. In 2010–11, the Integrated Cargo System (ICS) contained 2 394 profiles and alerts, which led to two million ‘matches’. When import data matches a profile or alert, an officer (known as a profile owner) is alerted electronically and must decide whether the cargo requires further inspection or examination to ascertain its contents.11

Responding to air and sea cargo import risks

12. There has been considerable change in recent years in the way Customs and Border Protection plans for, and responds to, identified risks. In July 2009, Customs and Border Protection introduced a new Cargo Intervention Strategy. This strategy maintained the practice of examining all cargo identified as high risk but reduced the number of planned inspections by 76 per cent for air cargo imports and 24 per cent for sea cargo imports. As a result, 63 fewer staff were allocated to sea and air cargo inspections and examinations. Detections in sea and air cargo covering the period 2008–09 to 2010–11 are outlined in Table S.1.

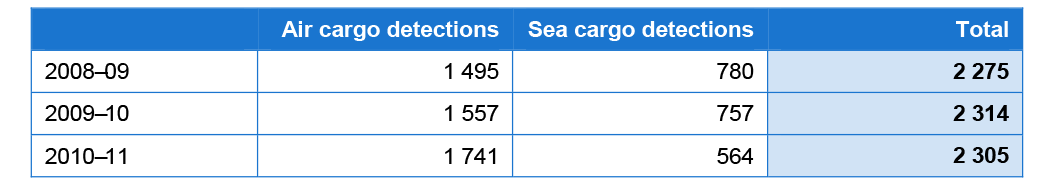

Table S.1: Detections of prohibited and restricted goods 2008–09 to 2009–10

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

Notes: Customs and Border Protection defines detections as ‘any examination result determined to be a breach of Customs related law at the time of examination’. Excludes referrals of potential quarantine items to the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS).

13. In July 2010, compliance activity also moved towards a more risk oriented, transaction-based approach through the implementation of the new Differentiated Risk Response Model (DRRM). A broader range of treatments was also adopted, including education, campaigns, pre-clearance monitoring and intervention, ‘saturation’ exercises and more focused field audits and visits.12 The implementation of the DRRM saw a reduction in the resourcing levels (24 staff) of Compliance Assurance Branch.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

14. The objective of the audit was to assess Customs and Border Protection’s use of risk management to assist in the processing of sea and air cargo imports.

15. The audit sought to determine whether Customs and Border Protection:

- has a soundly-based risk management model to support its management of the processing of sea and air cargo imports;

- uses risk management to determine cargo intervention and compliance activities; and

- supports risk management strategies with appropriate compliance measures.

16. International mail was not within the scope of the audit but has been listed as a potential audit in the ANAO’s 2011 Audit Work Program.

Overall conclusion

17. Achieving a balance between facilitation and control in managing sea and air cargo imports into Australia is a challenging task for Customs and Border Protection, particularly against a background of increasing cargo volumes. In 2010–11, there were a total of 16.2 million sea and air cargo imports13 and Customs and Border Protection has estimated that by 2020 this figure will rise to around 27 million. To inspect and/or examine all consignments would be a costly, resource intensive and time consuming exercise for Customs and Border Protection and importers. As this approach is neither desirable nor practical, it is essential that those consignments that present the highest border security risk are identified and dealt with appropriately.

18. Customs and Border Protection effectively uses risk management strategies to process sea and air cargo imports. The agency has a sound risk management framework with mature strategic and operational risk assessment and planning arrangements that are underpinned by a well-developed set of system-based profiles and alerts. Customs and Border Protection employs a number of cargo intervention and compliance strategies to mitigate identified risks. These strategies range from education through to audits of importers and the seizure of goods as well as other tools, such as administrative penalties. Customs and Border Protection has enhanced its risk management arrangements over time and, more recently, has developed a multi year planning and budgetary framework to align decisions on resource allocation with the assessment of organisational and border related risks.

19. The majority of sea and air cargo imports pass unimpeded across Australia’s border. However, assessing the effectiveness of Customs and Border Protection’s risk management strategies is difficult. While Customs and Border Protection is able to measure the volume and number of prohibited and restricted goods it detects and seizes, it is difficult to know the proportion of these goods that cross Australia’s border undetected. In the face of this uncertainty, accepted practice is for agencies to assess the effectiveness of their intervention and compliance strategies and risk assessment processes, and refine their approach in the light of experience. For Customs and Border Protection, this means evaluating its profiles and alerts and assessing the effectiveness of the CIS and the DRRM approach to compliance.

20. Profiles and alerts are Customs and Border Protection’s primary risk management tools. The design, testing and implementation of profiles have been substantially strengthened in recent years, including through the establishment in 2008 of a centralised National Profiling Centre. However, Customs and Border Protection has been slow to evaluate the effectiveness of its profiles and alerts, which the ANAO first identified as important in 2002. Three reviews in 2009 and 2010 have led Customs and Border Protection to introduce a Profile Governance Board and, in July 2011, to develop a Profile Effectiveness Review implementation plan.14 These recent initiatives are designed to enable Customs and Border Protection to assess whether its cargo profiles and alerts are identifying at-risk sea and air cargo imports.

21. Customs and Border Protection’s Cargo Intervention Strategy (CIS) was introduced in July 2009 and places greater emphasis on the use of intelligence to identify high risk consignments and to reduce the number of inspections and examinations that produce a nil result. Since 1 July 2009, the implementation of the CIS has seen a substantial reduction in the annual number of inspections (76 per cent in air cargo and 24 per cent in sea cargo) as air cargo is no longer being mass screened. As shown in Table S 1, the number of detections of prohibited and restricted goods in air cargo increased in 2009–10 by four per cent and increased by a further 12 per cent in 2010–11. For sea cargo, there was a slight (three per cent) decrease in 2009–10 followed by a decrease of 25 per cent in 2010–11. Whilst Customs and Border Protection sees detections as an important measure of success, assessing the effectiveness of the CIS will also require analysis of profiles and alerts data, and inspection and examination outcomes, and their interrelationships.

22. Customs and Border Protection introduced the Differentiated Risk Response Model in July 2010 to streamline and target its compliance intervention strategies. The new model reduces the emphasis previously placed on intensive audits of importers to the use of a broader suite of more risk oriented compliance activities. These include education and saturation exercises15 in addition to focused audits. With 2010–11 being a transitional year, it is not possible to reliably compare the outcomes of the new model with previous years.

23. To both encourage compliance and to discourage non-compliance, Customs and Border Protection introduced an administrative penalties regime in 1989. The scheme was replaced in 2002 by the Infringement Notice Scheme (INS).16 The INS process is considered to be difficult, time-consuming and cumbersome and Customs and Border Protection has made infrequent use of the scheme. On average, during the period July 2007 to June 2010, just over six penalties per month were issued for a total penalty amount of $273 877. This is in contrast to a similar scheme operating in Canada where an average of more than 660 penalties per month were issued over the same period for a total penalty amount in excess of $27 million.17 In an environment of increasing imports and reduced resourcing for intervention activity, a review of the appropriateness of the current INS is warranted.

24. Each year, Customs and Border Protection estimates customs duty and GST revenue leakage (that is, the difference between what should be collected and what is actually collected). However, it does this for one segment of the importing population only: those importers that are considered to be ‘compliant’. Focusing these estimates on compliant importers only makes it extremely difficult to compare the leakage estimates with the additional revenue Customs and Border Protection actually detects and collects. If this estimate is to be reliable, the sampling methodology should include all import populations, the approach Customs and Border Protection adopted for several years.

25. An emerging compliance risk facing Customs and Border Protection is Self Assessed Clearance Declaration importations. With the increase in online shopping, the number of goods being imported with a declared value of $1000 or less has more than tripled in the past five years to 10.5 million in 2010–11. These importations are exempt from the payment of customs duty and GST, and require less detailed information to be provided. The vast majority of these consignments are brought into the country by air express couriers whose business model places a premium on speedy delivery to customers. The ANAO’s analysis identified numerous SACs that, on the face of the available evidence, presented elevated risks for the importation of potentially prohibited or restricted goods and revenue evasion.18 Furthermore, often poor data quality compromises Customs and Border Protection’s ability to use profiles and alerts to effectively identify at risk SACs for closer scrutiny. A review of SAC processing arrangements would allow Customs and Border Protection to better assess the risks associated with this import stream.

26. The ANAO has made three recommendations aimed at improving Customs and Border Protection’s use of penalties as a compliance improvement tool, its revenue leakage estimation and the management of the risks associated with SACs.

Key findings

Development of the risk management framework and risk plans

27. In 2008, in conjunction with the other border agencies, Customs and Border Protection participated in the development of a Strategic Border Management Plan. Customs and Border Protection also reviewed its risk management arrangements to better integrate border risk management practices within an enterprise risk management framework.

28. Customs and Border Protection’s risk management framework covers all levels of risk– strategic, operational and tactical– and works to appropriately integrate these levels. Strategic risk planning in Customs and Border Protection is undertaken at the corporate level and the overall responsibility for risk management in the agency rests with the Chief Risk Officer (who is also the Chief Operating Officer) who chairs the Customs and Border Protection Risk Committee and reports to the Chief Executive Officer. The risk management framework is consistent with both the World Customs Organization’s Risk Management Guide and the International Risk Management Standard. While the overall risk management framework is effective, more work remains to be done, particularly in relation to the development of risk reporting templates19 and linking the risk management process with the resource allocation process. Customs and Border Protection intends that this work will be completed by 2012–13.

29. Operational risk planning is effectively undertaken by the Border Targeting, Compliance Assurance and Trade Policy and Regulation Branches. This planning forms the basis of Customs and Border Protection’s cargo interventions and compliance management strategies which are delivered through the Cargo Intervention Strategy and the Differentiated Risk Response Model. Identifying high risk air and sea cargo using profiles and alerts

30. Customs and Border Protection uses profiles and alerts extensively and, at any given time, there are approximately 2 500 profiles and alerts in the ICS. Profiles and alerts are triggered by matches to a range of import documents and are considered in conjunction with other information to identify high risk in sea and air cargo. Technical analysis by the ANAO confirmed that all sea and air cargo reports are ‘run’ against these profiles and alerts.

31. Customs and Border Protection has established a National Profiling Centre to manage the creation, testing and implementation of profiles. There are well documented processes for profile and alert creation and approval and they are subjected to robust testing in a test environment before being released into production.

32. Cargo targeters are responsible for creating profiles and alerts. They are also expected to monitor the day to day performance of these profiles and alerts by deleting or modifying a profile or alert that is resulting in a large number of unsuccessful matches and examinations or is due to expire. However, there is only limited guidance and system reminders to assist staff to monitor profiles.

33. The inspection or examination of goods can take the form of an x-ray of the consignment or the container in which the goods are located or physical opening and examination of containers or parcels. Inspections or examinations are labour intensive, particularly where an entire container needs to be unpacked. With more than two million profile and alert matches in 2010–11, resulting in the inspection and examination of 101 900 TEU20 and almost 1.5 million air cargo consignments, it is important that Customs and Border Protection monitors and evaluates the effectiveness of its profiles and alerts to minimise, as far as possible, inspections and examinations that yield no result. While comprehensive profile data is not readily available, analysis by Customs and Border Protection showed that for one cohort of profiles (air cargo), in one eight month period, there were 35 profiles that triggered some 240 000 matches, leading to 10 000 physical examinations, for just 18 positive results.

34. In six previous audit reports between 2002 and 2007, the ANAO had expressed concern (and made recommendations) about the lack of an effective mechanism to strategically evaluate the performance of profiles and alerts across all areas which use them. Progress on this issue has been slow. Three reviews in 2009 and 2010 led to the creation of a Profile Governance Board in April 2011. This Board will be responsible for standardising procedures across the agency and assessing the overall effectiveness of profiles and alerts to ensure that new profiles and alerts reflect identified changes in risks. A detailed implementation plan for reviewing profile effectiveness was completed in July 2011.

35. The importation, possession and use of illicit drugs, precursors and goods for a terrorist related purpose are serious criminal offences. Given this, and the high risk that such goods present to the community, the only effective treatment is to detect them in the cargo stream and seize them before they enter the country. Up to July 2009, Customs and Border Protection had set targets for the number of air consignments and sea cargo containers it would inspect (and examine if necessary): 6.2 million air cargo consignments21 and 134 000 TEU sea cargo containers. The pressure to meet these targets meant that Customs and Border Protection tended to concentrate on a limited number of high volume depots and warehouses because the large number of HVLV items these importers handled facilitated meeting the targets.

36. In July 2009, Customs and Border Protection introduced its Cargo Intervention Strategy (CIS) which places greater emphasis on the use of intelligence and techniques such as statistical analysis and data mining, coupled with profiles and alerts to identify high risk consignments. While it still has targets for the number of examinations, these have decreased to 1.5 million for air cargo consignments and 101 500 TEU. The CIS has also seen the reduction of 63 staff and a consequent saving of $49.5 million over the four years from 2009–10 to 2012–13.

37. There has been a decline in the total number of detections22 in sea cargo over time, although air cargo detections have increased over the same period. While detection outcomes may indicate some measure of success, the level of this success is not known as the undetected population of prohibited and restricted goods is also unknown. To determine how effective the CIS has been in identifying high—risk cargo, it will be important for Customs and Border Protection to analyse profiles and alerts data and inspection and examination outcomes, and their interrelationships.

38. Detections are classified and reported within Customs and Border Protection as either ‘major’ or ‘other’. The definition of ‘major’ is very broad, and includes, among other things, all detections of illicit drugs, regardless of the type or quantity.23 Major detections have included two cannabis seeds, an empty bullet casing and a single slingshot. In response to this audit, Customs and Border Protection has advised that it is reviewing this definition. Treatment of risks relating to cargo processing, regulated trade and revenue.

39. Risks relating to the processing of sea and air cargo imports, regulated trade and revenue may range from importers failing to comply with reporting requirements due to inadvertence or lack of knowledge through to individuals who seek to avoid the payment of customs duty or GST or to import prohibited goods or goods which require a permit (such as steroids).

40. Prior to the introduction of the new DRRM compliance model in July 2010, the primary treatment for these risks had been post-transaction audits. These audits could be resource intensive and time consuming. The new compliance model focuses on targeting non compliant transactions and behaviours and is more consistent with an intelligence-led risk based approach. Customs and Border Protection has also expanded its range of compliance activities to include education, campaigns, pre-clearance monitoring and intervention, ‘saturation’ exercises and more focused field audits and visits.24 The adoption of this new model has seen the reduction of 24 staff and a consequential saving of $8.1 million over the four years from 2009–10 to 2012–13.

41. It is too early to draw a firm conclusion whether the new compliance model (DRRM) has been effective, since the introduction of new compliance activities prevents ready comparisons with previous years. Based on the ANAO’s analysis of Customs and Border Protection’s performance reports to its Operations Committee, there have been improvements over time in a number of indicators, including an increase in the detections of underpayments of customs duty and GST.25 There was also an increasing trend in adjustments to revenue payments of $1000 or more from 29 per cent in 2005–06 to 80 per cent in 2010–11. These early indicators would suggest that the new model may achieve comparable results when dealing with risks to revenue.

42. The DRRM introduced a number of new or changed risk treatments. However, the compliance manual on Customs and Border Protection’s intranet was prepared in 2005 and had not been updated to reflect current organisational arrangements, numerous changes to Customs legislation since 2005 or current Compliance Assurance Branch business practices. There was also little recent material available on Customs and Border Protection’s website to explain the new model to its clients (such as importers, Customs brokers and depot and warehouse licensees), including their rights and responsibilities.

The Infringement Notice Scheme

43. Customs and Border Protection’s Infringement Notice Scheme (INS) allows it to impose penalties for offences ranging from a misleading statement in relation to imported goods to moving, altering or interfering with goods that are subject to Customs control without proper authorisation.26 The current INS is considered to be difficult, time-consuming and cumbersome. Over three years between July 2007 and June 2010, only 228 penalties (or just over six per month) were issued with a total penalty amount of $273 877. In 2010–11, the number of penalties increased to 338 (or 28 per month) with a total penalty amount of $338 573. Other Customs administrations have similar schemes and, in contrast to Customs and Border Protection, in the period from July 2007 to June 2010, the Canadian Border Services Agency issued 23 810 penalties (or 661 per month), with a total penalty amount of $27 687 100, suggesting much greater use is made of penalties when dealing with non compliance.

Estimation of revenue leakage

44. In 2001, Compliance Assurance Branch sought to develop a ‘statistically valid measure of client revenue compliance’. Until 2009, this approach involved undertaking ‘benchmark’ audits where the importations by a sample number of selected companies were examined for accuracy. In 2009, Customs and Border Protection used a Compliance Monitoring Program under which a randomly selected number of importers were asked to supply copies of commercial documents to verify data input to the ICS. Under both models, statistical analysis was then used to extrapolate the potential amount of revenue leakage (that is, the difference between customs duty and GST that were actually paid and the amount that should have been paid).

45. Customs and Border Protection varied this methodology in recent years and now bases its analysis on a sample of companies which it considers are ‘compliant’. As a result, the leakage estimates are inconsistent with the additional revenue Customs and Border Protection actually collects from its compliance activity. For example, in 2008–09 its GST leakage estimate was $1.7 million but it actually detected and collected $181.2 million. In reporting the results of the benchmark audits and Compliance Monitoring Program, which showed leakage at less than one per cent, Customs and Border Protection did not clearly state that it was measuring revenue leakage from compliant companies only. If this estimate is to be reliable, the sampling methodology should include all import populations, the approach Customs and Border Protection adopted for several years.

46. Since the introduction of the ICS in 2005, the Customs Act 1901 (the Customs Act) has allowed the importation of goods with a total value of $1 000 or less to be reported using a streamlined reporting process known as a Self Assessed Clearance (SAC). There are three types of SAC, with the most common, the Cargo Report Self Assessed Clearance (CRSAC) accounting for more than 10 million air cargo importations in 2010–11, a more than three-fold increase since 2005–06.27 This large increase is due to the increasing popularity of online shopping.

47. Customs and Border Protection officers have on numerous occasions expressed concerns about the risks posed by CRSACs. These include misdescription and undervaluation of goods (which can present risks both in terms of revenue evasion and importation of prohibited and restricted goods), inaccurate, incomplete and nonsensical goods descriptions. In 2011, Customs and Border Protection conducted an operation aimed at ‘ensuring that the current GST and customs duty thresholds were not being abused’. During the three months of the operation (from January to March 2011), 31 801 CRSACs were assessed.28 Proof of the purchase price paid was requested in 11 699 instances (36.8 per cent). Of those, 1 604 (13.7 per cent) resulted in the payment of $625 286 in additional customs duty or GST. Of the 31 801 consignments assessed during the three months of the operation, only 123 (0.4 per cent) were physically opened.

Cargo Report SACs data analysis

48. Given the concerns previously expressed by Customs and Border Protection officers, the ANAO downloaded and analysed data from a sample of approximately 1.3 million CRSACs submitted in 2010 (which represented about 13 per cent of the total number in the period). Given the historical nature of the data, it was not possible to physically examine the consignments. However, the ANAO’s analysis identified evidence that is indicative of a range of risks associated with CRSACs including:

- 1.2 million consignments with very low reported values ($0 to $10)29;

- consignments such as luxury car parts and new technology where the declared value appears inconsistent with the weight and description of the goods;

- consignments where the goods description appears inconsistent with the business of the consignor and consignee;

- consignments which were clearly described as alcohol and are not permitted to be entered on a CRSAC; and

- consignments where the goods description was incomplete or inaccurate (for example, ‘TBA’, ‘electronic stuff’, ‘sample’ or ‘# 70 010761’).

49. Given these risk indicators and the large increase in the number of CRSACs since 2005–06, there would be benefit in Customs and Border Protection reviewing its arrangements for SAC processing.

Summary of agency response

50. The proposed report was provided to Customs and Border Protection for formal comment. Customs and Border Protection provided the following summary response, and the formal response is shown at Appendix 1.

Customs and Border Protection welcomes the audit report, which confirms that the agency effectively uses risk management strategies to process sea and air cargo imports. Customs and Border Protection agrees with the recommendations in the report, which provide useful perspective on areas where improvement strategies can be explored to ensure the best possible approach to processing air and sea cargo.

Footnotes

[1] There is a large range of goods which governments have decided should either be prohibited from entering Australia altogether under any circumstances or which have legitimate uses but in respect of which a permit is required at the time of importation to ensure that they are not misused (such as tablet presses).

[2] A number of different currencies are used in this report. Where amounts are in Australian dollars (or have been converted into Australian dollars), they are expressed as, for example, $1000. Where they are in foreign currencies, the International Standards Organisation currency code is used (such as EUR 1000 or USD 1000).

[3] For the purposes of this report, references to ‘cargo’ encompass goods that are subject to Customs controls.

[4] ‘Home consumption’ means that the goods enter into the commerce of Australia.

[5] This can include airlines, shipping companies, air express couriers, freight forwarders and consolidators, aircraft and vessel owners, customs brokers and owners of cargo.

[6] Customs and Border Protection’s annual Time Release Study 2009 showed that 79 per cent of sea cargo and 71 per cent of air cargo were risk assessed prior to arrival and allowed to pass without impediment.

[7] Risk is defined as ‘the effect of uncertainty on the achievement of objectives’. (International Standards Office ISO 31000:2009 Risk management–principles and guidance).

[8] Border Targeting Branch is responsible for the highest risk areas of illicit drugs, precursors and terrorism. Trade Policy and Regulation Branch has policy responsibility for the remaining prohibited and restricted goods and Compliance Assurance Branch manages cargo control and revenue collection risks.

[9] Risk mitigation strategies can range from educating people about their obligations to comply with border legislation, the imposition of financial penalties to the seizure of goods, prosecution and imprisonment.

[10] Customs and Border Protection defines intervention as ‘use of any or all processes, including risk assessment, inspection and examination, in order to prevent the import or export of prohibited items and to control the movement of restricted items. Inspections may include the use of detector dogs, non-intrusive examination through the use of x-ray technology (static or mobile), trace particle detection or a physical examination of the cargo’. Examinations are defined as the ‘physical examination of the cargo by a Customs officer’.

[11] Air cargo inspections decreased from 6.2 million in 2008–09 to 1.5 million in 2010–11 and sea cargo inspections decreased from 134 000 in 2008–09 to 101 500 in 2010–11.

[12] Campaigns are national planned programs of activity aimed at testing assumptions about the level, extent or severity of risks. Pre-clearance monitoring includes checking a random selection of import declarations and, if necessary, seeking additional or clarifying documentation before the goods are released. Saturation exercises involve a tightly-focused short term activity and may involve, for example, screening all packages from a single airline flight.

[13] These comprised 13.9 million air and 2.3 million sea cargo import consignments.

[14] The Profile Governance Board will be responsible for standardising procedures across the agency, assessing the overall effectiveness of profiles and alerts and ensuring that new profiles and alerts reflect identified changes in risks.

[15] Saturation exercises are tightly-focused short term activities and may involve, for example, screening all packages from a single airline flight.

[16] Where an error or omission results in the short‑payment of customs duty, the penalty is 20 per cent of the short‑paid duty. For errors or omissions not resulting in a short‑payment, the penalties range from $55 to $1 320.

[17] While Canada has imports arriving by road and rail in addition to sea and air, the overall volume of imports is similar: in 2009–10, Canada had 11.9 million imports of all types compared with 13.6 million for Australia in the same period. The comparison period is July 2007 to June 2010 because 2010–11 Canadian data was not available. In 2010–11, the number of penalties issued by Customs and Border Protection increased to 338 (or an average of 28 per month) with a total penalty amount of $338 573.

[18] For example, in 2010, there were more than 1.2 million consignments with a declared value of less than $10 (not including legitimately low‑value goods such as business and personal documents). From a sample of approximately 1.3 million SAC transactions analysed by the ANAO, there were 2 194 consignments described as ‘new mobile phones’, all with a declared value of $0, 26 798 consignments described as ‘garments’ with a declared value of less than $10 and 42 consignments described as DHEA (a restricted anabolic steroid) which were not intercepted.

[19] In order to standardise the format and content of reports relating to each major risk area.

[20] Sea cargo shipping containers may either be 20 feet (6.1 metres) or 40 feet (12.2 metres) in length. For convenience, the trading community expresses all container measures in Twenty Foot Equivalent (TEU).

[21] In the early 2000s, a number of events occurring overseas (such as foot and mouth disease and equine influenza) led to additional resources being provided to Customs and Border Protection (and other agencies) to mass screen air cargo.

[22] This includes all prohibited items, but not referrals of potential quarantine material to AQIS which may not lead to a seizure. Air cargo detections increased from an average of 125 per month in 2008–09 to 145 in 2010–11 and sea cargo detections declined from an average of 65 per month in 2008–09 to 47 per month in 2010–11.

[23] In addition to any quantity of illicit drugs, Customs and Border Protection’s definition of major includes, for example, all fauna detections, anything with a suspected terrorism significance and anything which may be the subject of a media release or media interview.

[24] Campaigns are national planned programs of activity aimed at testing assumptions about the level, extent or severity of risks. Pre-clearance monitoring includes checking a random selection of import declarations and, if necessary, seeking additional or clarifying documentation before the goods are released. Saturation exercises involve a tightly-focused short-term activity and may involve, for example, screening all packages from a single airline flight.

[25] Detections of underpayments of customs duty increased from $12.4 million in 2006–07 to $37.0 million in 2010–11 and detections in underpayments in GST increased from $35.0 million to $47.7 million over the same period.

[26] Where an error, omission, timeliness in reporting or unauthorised movement of goods results in the short‑payment of customs duty, the penalty is 20 per cent of the short‑paid duty. For errors or omissions not resulting in a short‑payment, the penalties range from $55 to $1 320.

[27] The other SAC types are known as Short and Full format SACs which can be used to report consignments which contain alcohol or tobacco (which always attract customs duty, GST and Wine Equalisation Tax (if applicable)) or which require a permit to be imported.

[28] This included 11 199 CRSACs that Customs and Border Protection would have monitored under its ‘Business-as-usual’ monitoring program and an additional 20 602 assessments.

[29] Some shipments might legitimately have a very low monetary value, particularly those which comprise business and personal documents. Goods with such descriptions were excluded from the ANAO’s sample.