Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Regulation of Unsolicited Communications

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Communications and Media Authority’s regulation of unsolicited communications.

Summary

Introduction

1. Unsolicited communications, which includes unsolicited telemarketing, fax marketing, commercial emails and short message service (SMS) and multimedia message service (MMS) messaging, cost the global economy billions of dollars each year1 and impose on Australians’ time and resources. The Australian Government has established a suite of legislation—including the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 (DNCR Act) and the Spam Act 2003—that is designed to minimise the impact of unsolicited communications on Australians.

2. Under Part 26 of the Telecommunications Act 1997, a person may complain to the Australian Communications and Media Authority2 (the ACMA) about potential breaches of the DNCR Act and the Spam Act. The Authority’s mandate is to deliver a communications and media environment that balances the needs of industry and the Australian community through regulation, education and advice.

3. The regulation of unsolicited communications differs from some other regulatory environments because the industry to which the DNCR Act and Spam Act apply is not clearly defined. These Acts may apply to any industry sector that markets by telephone or email to Australian consumers. In general, the ACMA actively monitors the compliance of an entity only if a complaint or report has been made in relation to the entity’s marketing activities.

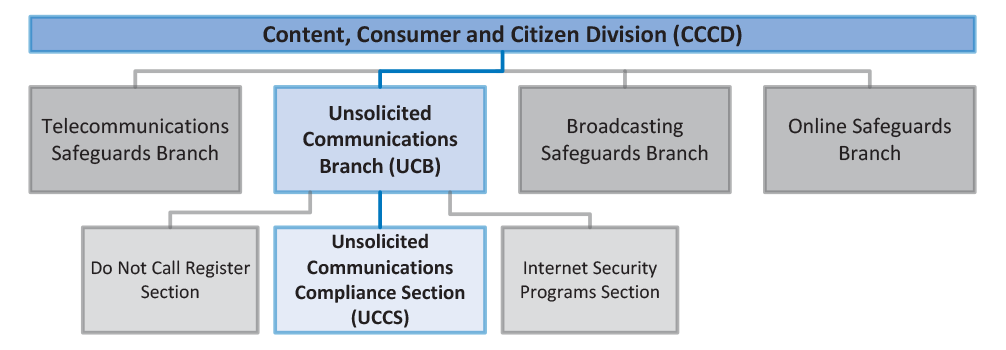

Unsolicited communications legislation

4. The DNCR Act, the Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard 2007 and the Fax Marketing Industry Standard 2011 set out the rules applying to telemarketing and fax marketing. The DNCR Act allows Australians who do not wish to receive telemarketing calls or marketing faxes to list their private-use fixed and mobile telephone numbers and fax numbers on the Do Not Call Register (DNCR).3 In February 2015, total DNCR registrations reached 10 million.

5. According to the DNCR Act, unsolicited telemarketing calls and marketing faxes are not to be made to numbers on the register. However, calls and faxes may still be made to registered numbers if they are research calls or fall into the category of designated calls and faxes. This designation applies to certain calls and faxes from registered charities, government bodies, members of parliament, political parties and educational institutions.

6. It is a breach of the Spam Act to send ‘unsolicited commercial electronic messages’ (known as spam) with an ‘Australian link’.4 The Spam Act covers email, SMS and MMS messaging and other electronic messages of a commercial nature. The Act also requires that commercial electronic messages are sent with the recipient’s consent, clearly identify the sender and include a functional unsubscribe facility.

Monitoring and addressing non-compliance

7. Consumers who have received unsolicited communications may lodge a complaint with the ACMA. In 2013–14, the ACMA received over 20 000 complaints in relation to non-compliance with the DNCR Act and almost 1400 complaints and 350 000 direct reports5 in relation to non-compliance with the Spam Act. The most common complaints related to telemarketing calls made to a DNCR-listed telephone number and entities sending commercial emails without first obtaining the recipient’s consent.

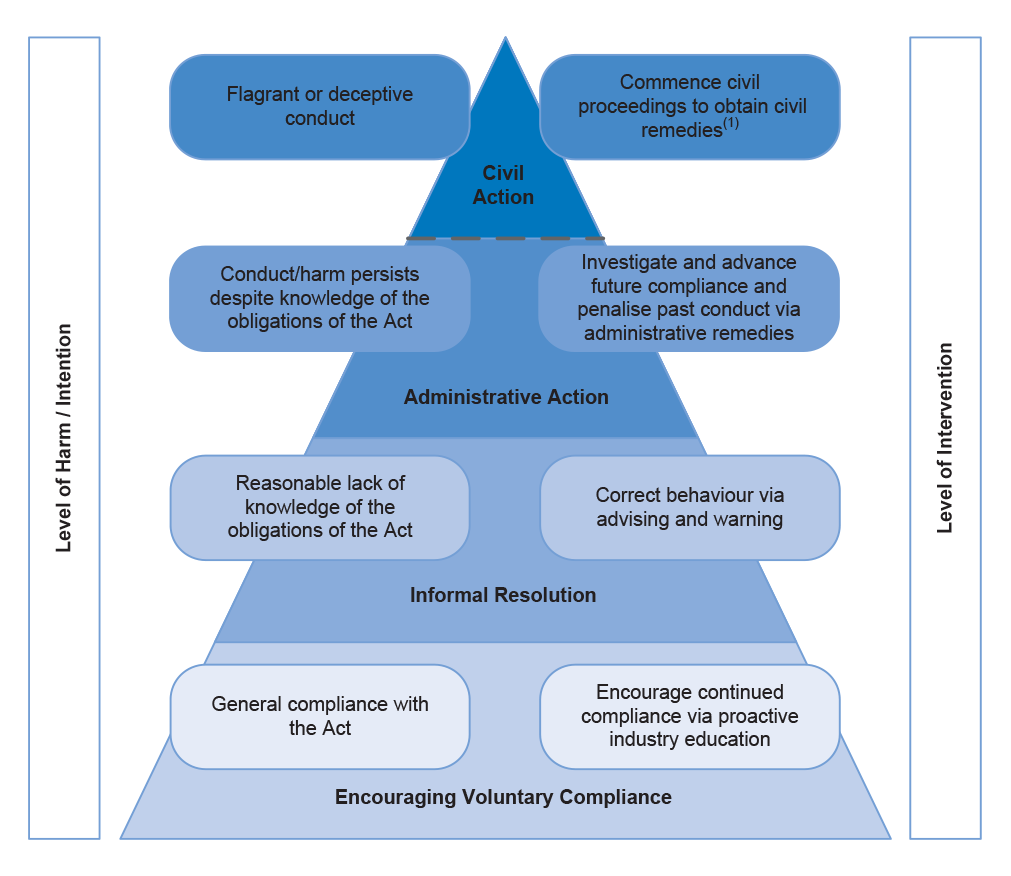

8. The graduated model used by the ACMA to respond to potential non-compliance ranges from encouraging voluntary compliance and informal resolution to administrative action and, where necessary, civil action. In 2013–14, the ACMA finalised 16 unsolicited communications investigations under the Telecommunications Act and took 14 enforcement actions—seven formal warnings, four infringement notices and three enforceable undertakings. For example, the ACMA issued a $20 400 infringement notice to a company that made telemarketing calls to telephone numbers listed on the DNCR and a $15 500 infringement notice to a company that sent spam emails that did not include adequate contact information or a functional unsubscribe facility.

Administrative arrangements

9. The ACMA’s Unsolicited Communications Branch (UCB) is responsible for the regulation of unsolicited communications. It is part of the Content, Consumer and Citizen Division (CCCD) and is based at the ACMA’s Melbourne office. Within this branch, the Unsolicited Communications Compliance Section (UCCS) manages compliance with both the DNCR Act and the Spam Act. In 2013–14, the UCCS had a budget of $1.8 million and 18 staff.

Audit objective and criteria

10. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Communications and Media Authority’s regulation of unsolicited communications.

11. To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an appropriate framework for assessing and mitigating risks and an effective strategy for monitoring compliance have been established;

- an effective risk-based program to communicate regulatory requirements and to monitor compliance with the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 and the Spam Act 2003 has been implemented; and

- non-compliance has been effectively addressed and resolved in accordance with established requirements.

12. The ACMA has been subject to ANAO audit coverage over recent years, including an audit in 2009–10 that assessed the Authority’s effectiveness in operating, managing and monitoring the Do Not Call Register.6 The audit made three recommendations, including one relating to the escalation of regulatory action. This recommendation was followed up as part of this audit’s examination of the ACMA’s monitoring of compliance with the DNCR Act.

Overall conclusion

13. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (the ACMA) is Australia’s regulator for broadcasting, the internet, radiocommunications and telecommunications. The ACMA is responsible for handling complaints from the Australian community about unsolicited communications, including potential breaches of the DNCR Act and the Spam Act, and for monitoring and addressing non-compliance with these acts. The ACMA’s graduated model for addressing non-compliance includes responses ranging from encouraging voluntary compliance and informal resolution to administrative action and, where necessary, civil action. In 2013–14, the ACMA received almost 22 000 complaints relating to unsolicited communications, issued approximately 6000 advisory and informal warning letters and conducted 16 investigations.

14. Overall, the ACMA has established appropriate arrangements to underpin its effective regulation of unsolicited communications. In particular, the ACMA has implemented: processes to help ensure that risks are identified and managed; generally sound policies, processes and practices to support its communication of regulatory requirements and its compliance monitoring activities; and a graduated approach to addressing and resolving non-compliance identified through its regulatory activities. There was, however, scope to improve the following aspects of the ACMA’s regulation of unsolicited communications:

- written investigation plans and risk assessments were not prepared for any of the 16 investigations finalised in 2013–14 and, in general, complainants were not notified when investigations had been completed. The preparation of written investigation plans, the assessment of investigation risks and the timely notification to complainants of the closure of each investigation would help to improve the delivery and oversight of investigations and achieve compliance with established requirements; and

- the current performance measures and reporting arrangements have not provided stakeholders with a clear indication of the impact and effectiveness of regulatory activities. Reviewing the measures for the regulation of unsolicited communications and monitoring and accurately reporting against them would better position the Authority to demonstrate the extent to which it is achieving its regulatory objectives.

15. The ANAO has made two recommendations, which are designed to strengthen the ACMA’s regulation of unsolicited communications by improving the planning, monitoring and closure of investigations and the monitoring and reporting of performance.

Key findings by chapter

Monitoring Compliance (Chapter 2)

16. A graduated compliance and enforcement approach for unsolicited communications has been adopted by the ACMA. It is underpinned by guiding principles and strategies to encourage and enforce unsolicited communications compliance. The ACMA’s model for responding to potential non-compliance includes responses ranging from encouraging voluntary compliance and informal resolution to administrative action and, in some circumstances, civil action. The Authority has also established minimum standards for escalating the DNCR regulatory response from informal resolution to administrative action.7 In contrast, minimum standards for escalating cases of spam non-compliance are yet to be established, which has the potential to result in inconsistent regulatory responses to suspected breaches of the Spam Act.

17. The ACMA has developed a Communications Strategy and Communications Plan to encourage voluntary compliance, help entities meet their regulatory responsibilities and assist the public in responding to unsolicited communications. The Communication Strategy provides staff with clear guidance on the UCB’s communication objectives and stakeholder engagement activities, and the Communication Plan effectively outlines the UCB’s key activities, when these activities are to be undertaken and who is responsible for them. Targeted communication and educational activities, such as social media engagement and industry blogs, are delivered as part of the Communications Plan.

18. The arrangements to receive and handle complaints, related to both the DNCR Act and the Spam Act, have generally been managed effectively, with appropriate processes and practices implemented for the lodgement, assessment, acknowledgement and processing of complaints. In relation to the 2013–14 cases examined by the ANAO, the ACMA responded to 97 per cent of DNCR complainants and 81 per cent of spam complainants within an average response time of five days for DNCR complaints and one day for spam complaints. The examined complaints were also generally managed in a timely manner—with 91 per cent of DNCR complaints handled within 21 days of receipt (which exceeded the established target timeframe of 90 per cent) and 75 per cent of spam complaints handled within eight days of receipt (which was below the established target timeframe of 90 per cent).

19. The ACMA reported that it issued approximately 6000 advisory and informal warning letters in 2013–14 in relation to potential non-compliance with the DNCR Act and Spam Act.8 According to the ACMA’s 2013–14 Annual Report, the majority of companies contacted by the ACMA received only one advisory or informal warning letter during 2013–14.9

20. In relation to the spam informal warning letters examined by the ANAO, around 70 per cent related to only one spam report (and no complaints). These letters lacked sufficient information for people and companies to resolve the alleged issues, as letters sent in response to spam reports do not include details of the date the alleged spam message was sent or the email address or mobile number to which the spam message was sent. Further, these informal warning letters were sent, on average, 53 days after a spam report was received by the ACMA, which, when coupled with the limited information provided in the letters, generally made it difficult for people and companies to determine whether a breach had occurred and to address the issue, where necessary. During the audit, the ACMA informed the ANAO that it would amend its procedures so that it will not send informal warning letters to people and companies in circumstances where it is unable to provide sufficient details on the alleged spam message.

Addressing Non-compliance (Chapter 3)

21. The ACMA has established policies for conducting investigations. In 2013–14, the ACMA finalised 16 investigations into potential contraventions of the DNCR Act and the Spam Act. For all investigations, key decisions were made by an appropriate ACMA officer and appropriate documentation was retained on the relevant case files. However, written investigation plans and assessments of investigation risks were not prepared for any of the 16 investigations finalised in 2013–14. The preparation of written plans and risk assessments are outlined as recommended minimum standards in the Australian Government Investigations Standards (AGIS) and are required by the ACMA’s policies. The AGIS also outline that supervisors should review investigations at appropriate intervals to ensure adherence with the AGIS and investigation plans. In the absence of investigation plans, supervisors were not well placed to monitor the performance of the ACMA’s investigations.

22. In 2013–14, all entities that were investigated (the respondents) were notified of the closure of the investigation in a timely manner. In contrast, the consumers who had made the complaints on which the investigations were based (the complainants) were notified of the closure of the investigation for only three of the 16 investigations. In addition to being outlined as a requirement in the ACMA’s internal policies, notifying complainants is part of the ACMA’s published complaint handling policies.

23. Unsolicited communications legislation provides for several forms of enforcement action that may be used in response to non-compliance: formal warnings, infringement notices, enforceable undertakings and federal court action. In 2013–14, the ACMA took 14 enforcement actions—seven formal warnings, four infringement notices and three enforceable undertakings. All decisions to take enforcement action were appropriately documented and included the rationale for the selected action. All decisions were retained on the case files and signed by an appropriate ACMA officer. For all infringement notices, legislative requirements were met, payments were received on time and proof of payment was retained on the case files.

24. Since 2003, the ACMA has completed four prosecutions in the Federal Court, involving 12 respondents and resulting in $30.08 million in penalties. In relation to the one case involving the DNCR Act, the ACMA also obtained a five-year injunction that restricted the respondent from engaging in the telemarketing sector.10

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 4)

25. The ACMA has established appropriate administration arrangements to underpin its regulation of unsolicited communications, including oversight arrangements to monitor key aspects of regulatory activity and an established process for business planning. Sound guidance on risk management has been developed through a risk management framework review that had been underway at the ACMA between 2011 and early 2014. The Authority has also established appropriate arrangements to identify and manage conflicts of interest, including a management instruction outlining requirements and appropriate monitoring arrangements.

26. The ACMA regularly reports on its compliance activities to both internal and external stakeholders, primarily through monthly and quarterly management reports, annual reports, annual communications reports and monthly compliance activity statistics. There have, however, been some issues in relation to the accuracy of reporting, with inaccurate compliance activity data included in the ACMA’s 2013–14 Annual Report and, subsequently, in its 2013–14 Communications Report. In addition, there is a lack of alignment of performance measures across key planning documents and an absence of targets for objectively assessing performance. Existing measures provide limited insights into the impact or effectiveness of the regulation of unsolicited communications. Reporting against an appropriate set of performance measures would enable the ACMA to better demonstrate the extent to which it is achieving its regulatory objectives.

Summary of entity response

27. The ACMA’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (the ACMA) welcomes the ANAO’s report on its audit of the ACMA’s activities in the regulation of unsolicited communications.

The ACMA notes that the report presents, overall, a positive picture of the ACMA’s regulatory program for handling complaints about unsolicited communications, including potential breaches of the Spam and DNCR Acts, and for monitoring and addressing non-compliance with these Acts. I welcome the ANAO’s findings and recommendations as presenting opportunities to further enhance and improve this program.

The ACMA accepts the ANAO’s two recommendations contained within the report, and has already implemented and/or will complete implementation of these recommendations. In response to Recommendation 1, the ACMA now prepares and uses investigation plans to conduct investigations, and routinely notifies complainants of the closure of investigations. The ACMA is currently reviewing and enhancing its measures for regulation of unsolicited communications, in response to Recommendation 2, and will fully implement these performance measures during 2015–16.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.37 |

To improve the planning, monitoring and closure of investigations and to comply with established requirements, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Communications and Media Authority:

ACMA’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.48 |

To improve the effectiveness of its performance monitoring and reporting and to better inform stakeholders about the extent to which regulatory objectives are being achieved, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Communications and Media Authority:

ACMA’s response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides information on the Australian Communications and Media Authority’s regulation of unsolicited communications and sets out the audit approach.

Unsolicited communications

1.1 Unsolicited communications, which includes unsolicited telemarketing, fax marketing, commercial emails and short message service (SMS) and multimedia message service (MMS) messaging, cost the global economy billions each year11 and impose on Australians’ time and resources. The Australian Government has established a suite of legislation that is designed to minimise the impact of unsolicited communications on Australians. This legislation includes the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 (DNCR Act) and the Spam Act 2003.

1.2 Under Part 26 of the Telecommunications Act 1997, a person may complain to the Australian Communications and Media Authority (the ACMA) about potential breaches of the DNCR Act and the Spam Act. The ACMA is a statutory authority within the federal Communications portfolio and Australia’s regulator for broadcasting, the internet, radiocommunications and telecommunications. The ACMA’s mandate is to deliver a communications and media environment that balances the needs of industry and the Australian community through regulation, education and advice.12

1.3 The regulation of unsolicited communications differs from some other regulatory environments, because the industry to which the DNCR Act and Spam Act apply is not clearly defined. These Acts may apply to any industry sector that markets by telephone or email to Australian consumers. In general, the ACMA actively monitors the compliance of an entity only if a complaint or report has been made in relation to the entity’s marketing activities. In 2013–14, the ACMA received almost 22 000 complaints and 350 000 direct reports from the Australian community about potential breaches of unsolicited communications legislation.

Do Not Call Register Act

1.4 The DNCR Act, the Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard 2007 and the Fax Marketing Industry Standard 2011 set out the rules applying to telemarketing and fax marketing. The DNCR Act allows Australians who do not wish to receive telemarketing calls or marketing faxes to list their private-use fixed and mobile telephone numbers and fax numbers on the Do Not Call Register (DNCR).13 As at 30 June 2014, more than 9.6 million numbers had been listed on the register, representing around half of Australia’s fixed-line numbers, 4.1 million mobile numbers and 377 000 fax numbers, as outlined in Figure 1.1. In February 2015, total DNCR registrations reached 10 million.

Figure 1.1: Numbers on the Do Not Call Register (2009–10 to 2013–14)

Source: ACMA’s 2013–14 Annual Report, p. 120.

1.5 According to the DNCR Act, unsolicited telemarketing calls and marketing faxes are not to be made to numbers on the register. However, calls and faxes may still be made to registered numbers if they are research calls or fall into the category of designated calls and faxes. This designation applies to certain calls and faxes from registered charities, government bodies, members of parliament, political parties and educational institutions.

1.6 To avoid breaching the DNCR Act, telemarketers and fax marketers are to submit their contact lists for checking against the register. In 2013–14, over 1.1 billion numbers were checked or ‘washed’ against the register by 1189 telemarketers and fax marketers.

1.7 The Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard and the Fax Marketing Industry Standard set out the rules all telemarketers, fax marketers and researchers must follow, including: not making telemarketing and research calls or sending marketing faxes during prohibited calling times14; ending telemarketing calls when requested; providing opt-out functionality for marketing faxes; and including a valid calling line identification number. All consumers are protected by the requirements of the industry standards, whether or not they have listed their numbers on the DNCR.

1.8 Consumers who have listed their number(s) on the register may make complaints to the ACMA about unsolicited telemarketing and fax marketing calls. The most common DNCR-related complaint relates to telemarketing calls made to a listed telephone number, which is a potential breach of the DNCR Act. The ACMA has the power to investigate and, where necessary, take enforcement action in response to breaches of the legislation. All Australians are able to make complaints to the ACMA about potential breaches of the industry standards. In 2013–14, the ACMA received over 20 000 complaints in relation to non-compliance with the DNCR Act and industry standards and conducted a range of compliance activities, as outlined in Table 1.1.

1.9 The ACMA has adopted an ‘advise, warn, investigate’ approach to DNCR compliance, applying a graduated level of intervention and focusing on industry education and stakeholder engagement. When the ACMA is able to identify the entity that is the subject of a telemarketing or fax complaint, it sends an ‘advisory’ letter, providing the party with information about its legislative obligations and advising that its compliance will be monitored for 180 days. During 2013–14, the ACMA issued 940 advisory letters to entities identified as potentially in breach of the requirements of the DNCR Act and industry standards, as outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: DNCR complaints and compliance activities (2012–14)

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Complaints |

19 677 |

20 462(1) |

|

Advisory letters |

918 |

940(2) |

|

Informal warning letters |

139 |

114(3) |

|

Investigations finalised |

11 |

6 |

|

Enforcement actions |

8 |

5 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Note 1: The ACMA informed the ANAO that this is the number of DNCR complaints received and classified in 2013–14. The number of complaints is higher than the number of advisory letters for two main reasons: (1) 20 per cent (4178) of DNCR complaints received in 2013–14 were assessed as being ‘no breach’; and (2) advisory letters are not sent for each complaint. Advisory letters are sent when one complaint is received and the entity is subsequently monitored for 180 days. No further advisory letters are generally sent during the monitoring period (even if further complaints are received). However, if five or more complaints are received during the period, an informal warning letter may be sent.

Note 2: The ACMA informed the ANAO that the number of advisory letters listed in the 2013–14 Annual Report (951) was incorrect. The ACMA provided the revised figure (942) to the ANAO in October 2014. The ANAO’s analysis identified two additional cases where reported advisory letters had not been sent, which brings the total down to 940.

Note 3: The ANAO’s analysis identified that two listed informal warning letters had not been sent, bringing the reported figure of 116 down to 114.

1.10 Where the ACMA receives five or more complaints about the same entity during the 180-day monitoring period, it may issue an informal warning letter, which provides more detailed information about the complaints received (including the date, time of call and substance of complaint) and provides the party with a further opportunity to address issues on a voluntary basis. In 2013–14, the ACMA issued 114 informal warning letters to entities that were the subject of multiple DNCR complaints.

1.11 Where non-compliance continues after an entity has been advised and warned, the ACMA considers whether to proceed to an investigation. During 2013–14, the ACMA finalised six telemarketing-related investigations under Part 26 of the Telecommunications Act. As a result of these investigations, the ACMA issued one infringement notice, accepted two enforceable undertakings, issued two formal warnings and closed one investigation with no enforcement action being taken.

Spam Act

1.12 It is a breach of the Spam Act to send ‘unsolicited commercial electronic messages’ (known as spam) with an ‘Australian link’.15 The Act covers email, SMS and MMS messaging and other electronic messages of a commercial nature. The Act requires that commercial electronic messages: are sent with the recipient’s consent; clearly identify the sender; and include a functional unsubscribe facility.

1.13 Consumers may make complaints about spam to the ACMA, with the most common spam-related complaint relating to companies sending commercial emails without first obtaining the recipient’s consent.16 Consumers may also report spam to the ACMA by forwarding a spam email or SMS to the Authority’s Spam Intelligence Database. Unlike complaints, reports are not necessarily reviewed individually, but they contribute to intelligence about spam trends and prevalence. Of the direct reports reviewed by the ACMA in 2013–14, the most common breach identified was the same as for complaints—that an email had been sent without the recipient’s consent.

1.14 In 2013–14, the ACMA received 1387 complaints and almost 350 000 direct reports about non-compliance with the Spam Act. In response, the ACMA issued 4967 informal warnings, as outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Spam complaints, reports and compliance activities (2012–14)

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Complaints |

1246 |

1387(1) |

|

Reports |

409 761 |

346 592 |

|

Informal warning letters |

7105 |

4967(2) |

|

Investigations finalised |

10 |

10 |

|

Enforcement actions |

9 |

9 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Note 1: The number of complaints is lower than the number of informal warning letters because the ACMA also sends informal warning letters in response to some spam reports.

Note 2: The ACMA informed the ANAO that the number of informal warning letters published in the 2013–14 Annual Report (5002) was incorrect, providing the revised figure (4967) in October 2014.

1.15 When multiple informal warnings have been issued to an entity and voluntary compliance is not forthcoming, the ACMA considers whether to proceed to an investigation. In 2013–14, the Authority finalised 10 spam-related investigations, which resulted in nine enforcement actions—five formal warnings, three infringement notices and one enforceable undertaking.

Gathering intelligence

1.16 The ACMA gathers intelligence though direct complaints and reports from the public about potential breaches of DNCR and spam legislation. The ACMA also receives over 20 million ‘indirect reports’ of spam annually—from a variety of sources, including ‘spamtraps’.17 These spam messages are stored, along with direct reports, in the Spam Intelligence Database. The ACMA uses software tools to analyse this large volume of spam to identify messages that are likely to have the greatest impact on Australians. The Spam Intelligence Database is also used to identify trends, such as prolific senders, and the incidence of malware18 within spam messages.

Collaboration and international engagement

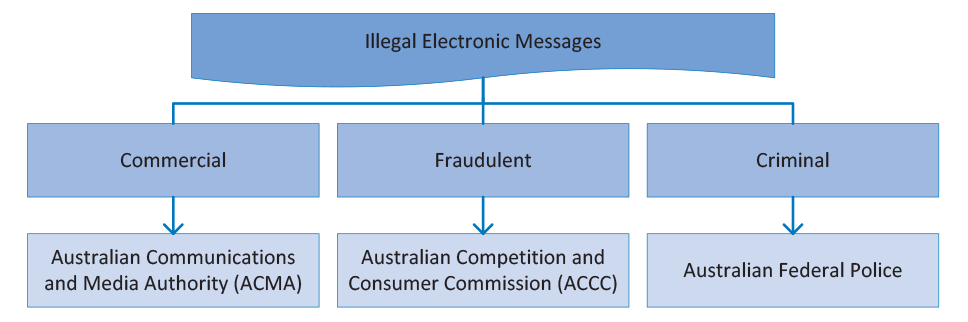

1.17 A number of federal government entities have responsibilities regarding illegal electronic messages. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)19 is responsible for handling fraudulent messages and scams, and the Australian Federal Police is responsible for high tech crime offences, such as the distribution of malware (see Figure 1.2). While the ACMA is responsible for all commercial electronic messages under the Spam Act (regardless of their content), it has discretion to pursue a matter under the Spam Act and/or refer it to another relevant agency.

Figure 1.2: Federal responsibilities for the regulation of illegal electronic messages

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

1.18 The ACMA also participates in the Australasian Consumer Fraud Taskforce, which comprises 22 government entities with responsibility for consumer protection regarding frauds and scams.

1.19 Further, the ACMA seeks to collaborate with overseas counterparts on common problems and to share information, with the goal of reducing the impact on Australians of unsolicited communications originating offshore. For example, the ACMA participates in the London Action Plan—an international network that was founded in 2004 with the purpose of promoting international spam enforcement cooperation. It has since expanded its mandate to include additional online and mobile threats, including unsolicited telemarketing calls and administering Do Not Call schemes. The network has 45 government members and 28 industry participants.

Administrative arrangements

1.20 The ACMA’s day-to-day activities are managed by an executive team comprising: the Chair; the Deputy Chair; one full-time Member20; four general managers; and 11 executive managers. General Managers are currently responsible for four divisions: Content, Consumer and Citizen; Communications Infrastructure; Corporate and Research; and Legal Services. In 2014–15, the ACMA’s budget was $99.3 million21, and it employed approximately 450 staff.22

1.21 The Unsolicited Communications Branch (UCB) is part of the ACMA’s Content, Consumer and Citizen Division (CCCD) and is based at the ACMA’s Melbourne office. Within this branch, the Unsolicited Communications Compliance Section (UCCS) manages compliance with both the DNCR Act and the Spam Act.23 In 2013–14, the UCCS had a budget of $1.8 million and 18 staff.

Previous reviews and audit coverage

Review and amendment of the Do Not Call Register

1.22 In February 2014, the DNCR Act was amended by the Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (Consumer Protection) Act 2014 to enable the ACMA to more effectively pursue telemarketers that use third parties overseas and other intermediaries to reach Australian consumers, in breach of the DNCR Act.

1.23 In mid-2014, after releasing a discussion paper and receiving 1300 submissions on the optimal period of registration for the DNCR24, the Department of Communications submitted legislation to the Parliament to amend the DNCR Act. In April 2015, the resulting legislation, the Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (Deregulation) Act 2015, amended the DNCR Act to make the registration period of the register indefinite, which is intended to reduce the administrative burden on consumers.

ANAO performance audit coverage

1.24 The ACMA has been subject to ANAO audit coverage over recent years, including:

- ANAO Audit Report No.46 2007–08 Regulation of Commercial Broadcasting; and

- ANAO Audit Report No.16 2009–10 Do Not Call Register.

1.25 The objective of the 2009–10 audit of the DNCR was to assess the ACMA’s effectiveness in operating, managing and monitoring the register, including compliance with legislative requirements. The audit concluded that, overall, the ACMA had implemented arrangements that effectively supported its regulatory oversight of the register. The audit made three recommendations that focused on information technology (IT) security management practices, complaint handling and the escalation of regulatory action, including Recommendation 3:

To further improve transparency and minimise the risk of inconsistency in compliance enforcement decision making, the ANAO recommends that ACMA set minimum standards in its procedures for escalating regulatory action.

1.26 This audit followed up on Recommendation 3 as part of its examination of the ACMA’s monitoring of compliance with the DNCR Act.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Objective

1.27 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Communications and Media Authority’s regulation of unsolicited communications.

Criteria

1.28 To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an appropriate framework for assessing and mitigating risks and an effective strategy for monitoring compliance have been established;

- an effective risk-based program to communicate regulatory requirements and to monitor compliance with the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 and the Spam Act 2003 has been implemented; and

- non-compliance has been effectively addressed and resolved in accordance with established requirements.

Scope

1.29 The audit focused on the regulatory aspects of the DNCR Act and the Spam Act. The audit did not examine the day-to-day administration of the DNCR, the ACMA’s contract arrangements with the third-party operator of the DNCR or the Authority’s internet security activities.

Methodology

1.30 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO: examined policy documents, guidelines and standard operating procedures; reviewed files and records; interviewed relevant ACMA staff; examined a random sample of 2013–14 compliance monitoring activities related to the DNCR Act and the Spam Act25; and examined all 16 investigations and 14 enforcement actions finalised in 2013–14.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $354 500.

Report structure

1.32 The structure of the report is set out in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Outline |

|

2. Monitoring Compliance |

Examines the ACMA’s monitoring of compliance with unsolicited communications legislation. |

|

3. Addressing Non-compliance |

Examines the ACMA’s approach to addressing and resolving non-compliance with unsolicited communications legislation. |

|

4. Governance Arrangements |

Examines the governance arrangements in place to support the ACMA’s regulation of unsolicited communications. |

2. Monitoring Compliance

This chapter examines the ACMA’s monitoring of compliance with unsolicited communications legislation.

Introduction

2.1 The Unsolicited Communications Compliance Section (UCCS) undertakes compliance monitoring activities and investigations of potential breaches of the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 (DNCR Act), the Spam Act 2003 and associated industry standards in response to complaints and reports made to the ACMA by the public. The UCCS’s objectives are to ‘minimise unsolicited telemarketing calls and faxes to citizens; spam emanating from Australia; and the impact of spam on citizens’.

2.2 The ANAO examined the ACMA’s compliance and enforcement policies and the manner in which the ACMA monitors compliance with unsolicited communications legislation, including its activities for:

• communicating with stakeholders and encouraging voluntary compliance;

• assessing complaints and reports; and

• responding to non-compliance.

Compliance and enforcement policies

2.3 The ACMA has adopted a compliance and enforcement approach for unsolicited communications that is underpinned by guiding principles and strategies to encourage and enforce unsolicited communications compliance. This graduated approach seeks to: educate the industry about its regulatory obligations; encourage a culture of compliance; promote better practice; and achieve compliance with minimal intervention. The ACMA’s unsolicited communications compliance strategy outlines its DNCR and spam compliance mission and business objectives. The ACMA has also developed a Compliance and Enforcement Manual, which covers: ACMA enforcement and regulatory policy; scoping and planning of investigations; evidence gathering; decision-making; compliance and enforcement options; and information management procedures. It was most recently updated in April 2014.

2.4 In addition to established corporate policies and manuals, the UCCS has standard operating procedures for complaint handling and compliance monitoring.

Graduated response to non-compliance

2.5 A graduated approach to compliance allows a regulator to either escalate action if an entity does not respond appropriately to initial regulatory action or reward an entity for improved performance with reduced compliance activity. In addition, the flexibility of a graduated approach allows a regulator’s response to: be proportionate to the risks posed by the non-compliance; recognise the capacity and motivation of the non-compliant entity to return to compliance; and signal the seriousness with which a regulator should view the non-compliance.26

2.6 The graduated model used by the ACMA to respond to potential non-compliance in relation to unsolicited communications includes responses ranging from encouraging voluntary compliance and informal resolution to administrative action and, where necessary, civil action (see Figure 2.1). When determining the appropriate response, compliance officers are to take into account: the regulatory objectives of the legislation breached; the nature of the breach; the entity’s compliance history; and the entity’s level of cooperation with the ACMA.

Figure 2.1: Compliance and enforcement response model

Source: UCCS Compliance and Enforcement Approach diagram (reproduced by the ANAO).

Note 1: In specific circumstances, matters may be referred for criminal prosecution.

2.7 The UCCS has developed business rules to guide compliance officers through its graduated response model. As outlined in Table 2.1, the number of compliance activities escalated during 2013–14 decreased at each compliance tier, aligning with the expected graduated response pattern.

Table 2.1: UCCS compliance and enforcement responses (2013–14)

|

Compliance Tier |

Compliance Activity |

DNCR Act |

Spam Act |

|

Informal resolution |

Advisory letters |

940 |

— |

|

Informal warning letters |

114 |

4967 |

|

|

Administrative action |

Investigations |

6 |

10 |

|

Enforcement actions |

5 |

9 |

|

|

Civil action |

Federal court action |

0 |

0 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Minimum standards for escalating regulatory action

2.8 The ACMA has established minimum standards for escalating the DNCR regulatory response through the informal resolution tier and from informal resolution to administrative action. According to UCCS business rules, an entity is to be:

- issued with an advisory letter when one (or more) complaints are received by the ACMA;

- moved from advisory letter stage to informal warning letter stage if the ACMA receives five or more complaints about the entity during a 180-day monitoring period (which commences from the date of the advisory letter); and

- moved from informal warning letter stage to consideration for possible investigation if the ACMA receives five or more complaints during an additional 180-day monitoring period (which commences from the date of the informal warning letter).

2.9 In contrast to DNCR regulatory activities, minimum standards for escalating spam regulatory responses have not been established. Informal warning letters are generally sent to an entity every month that spam complaint(s) and/or reports(s) are received until compliance officers determine that voluntary compliance is not likely to occur and they recommend that the entity be considered for possible investigation. The establishment of thresholds for escalating compliance activities for non-compliance with the Spam Act would help to deliver more consistent regulatory responses.

Communicating with stakeholders and encouraging voluntary compliance

2.10 The relationships that a regulator establishes with regulated entities and other stakeholders can make an important contribution to the effective administration of regulation. Effective stakeholder engagement has many benefits, such as allowing a regulator to: effectively elicit compliance; identify and address compliance issues as they emerge; and design appropriate responses to non‐compliance.

2.11 The ACMA engages in targeted communication and educational activities to encourage voluntary compliance, help entities meet their regulatory responsibilities and assist the public in responding to unsolicited communications. These activities include direct contact with stakeholders, industry blogs and social media engagement. The ANAO examined the ACMA’s approach to communicating with stakeholders, including: communication strategies; communicating regulatory responsibilities and encouraging voluntary compliance; and communicating enforcement action outcomes.

Communication strategies

2.12 The Unsolicited Communications Branch (UCB) is responsible for communication, education and public awareness activities related to the DNCR Act and Spam Act. These activities include: managing relevant pages of the ACMA website; preparing blog posts; issuing media releases and scam alerts; and engaging with stakeholders through social media.

2.13 The UCB has developed a Communication Strategy, which aims to: make citizens aware of the protections available against unsolicited communications, including their legislative limitations; encourage people and companies engaging in telemarketing and e-marketing to comply; and inform citizens and small to medium-sized enterprises of new security threats. It defines key stakeholders, communication objectives, key messages, priorities and measures of success. Measures of success include traffic to ACMA websites and blogs and engagement on social media. The ACMA uses web analytics to measure performance in these areas, and the media communications team provides monthly web analytic reports to the UCB and the Executive Group.27 The UCB revises the Strategy periodically, with the most recent version dated September 2014.

2.14 The UCB has also developed a Communication Plan, which establishes the goals, responsible parties, target audiences, key messages and measures of success for periodic and event-driven stakeholder activities. The plan outlines key activities, when activities are to be undertaken and who is responsible for them. It is reviewed periodically, with the most recent version, at the time of the audit, dated February 2014.

Communicating regulatory responsibilities and encouraging voluntary compliance

2.15 Effective two-way engagement and communication with regulated entities can lead to positive regulatory outcomes. When regulated entities have a clear understanding of their regulatory obligations, they are better able to comply.28 The UCB uses a variety of channels, including websites, blogs and social media, to provide DNCR Act and Spam Act guidance and educational material and advice to consumers on the scope and nature of the ACMA’s regulatory role, such as advice that the ACCC, rather than the ACMA, is responsible for scam calls.

Websites

2.16 The UCB maintains a number of pages on the ACMA website for the purpose of consumer and stakeholder education and guidance, including:

- Stay protected: web pages that target consumers and provide fact sheets and online forms to lodge complaints about unsolicited communications; and

- acma-i: a web page that targets industry, containing regulatory fact sheets and information on outcomes and statistics of complaints, investigations and enforcement activities.

2.17 In addition, the third-party Register Operator29 maintains the DNCR website, which provides information for citizens and companies on outcomes of investigations, scam alerts and facilities for registering phone numbers and lodging complaints.

2.18 Since February 2014, the UCB has collected web analytics data, such as the number of total and unique page views for key web pages and the average time spent on each page. The UCB uses this data to track and evaluate its stakeholder engagement and communication activities. In the period from February to August 2014, there was an increase in the total number of monthly views for the web pages that the UCB maintains (17 648 in February to 21 211 in August), with, on average, views for industry-related web pages representing 63 per cent of total page views and views for web pages targeting consumers representing 37 per cent of total views.

Blogs

2.19 The UCB also maintains several blogs that aim to provide industry with better practice guidance and to address developing industry trends (see Table 2.2). A key use of the blogs is regulatory education, with entities directed to blog posts by compliance officers in instances where potential non-compliance has been identified.

Table 2.2: Scope and number of the ACMA’s blog posts (2013–15)

|

Scope of Blog |

Number of Posts |

|

|

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Successful e-marketing…it’s about reputation |

||

|

Email and SMS marketing, covering topics such as: unsubscribe features; sender identification; purchasing contact lists; and overseas outsourcing. |

6 |

6 |

|

Better telemarketing…take the right line |

||

|

Advice on telemarketing and fax marketing processes and practices, insights into common consumer concerns and issues and simple ideas to make your marketing campaigns more effective. |

2 |

1 |

|

The guru guide |

||

|

Intended to give an insider’s view on what’s happening in the world of e-marketing, fax marketing and telemarketing compliance. |

3 |

0 |

|

Total |

11 |

7 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA blogs.

Social media

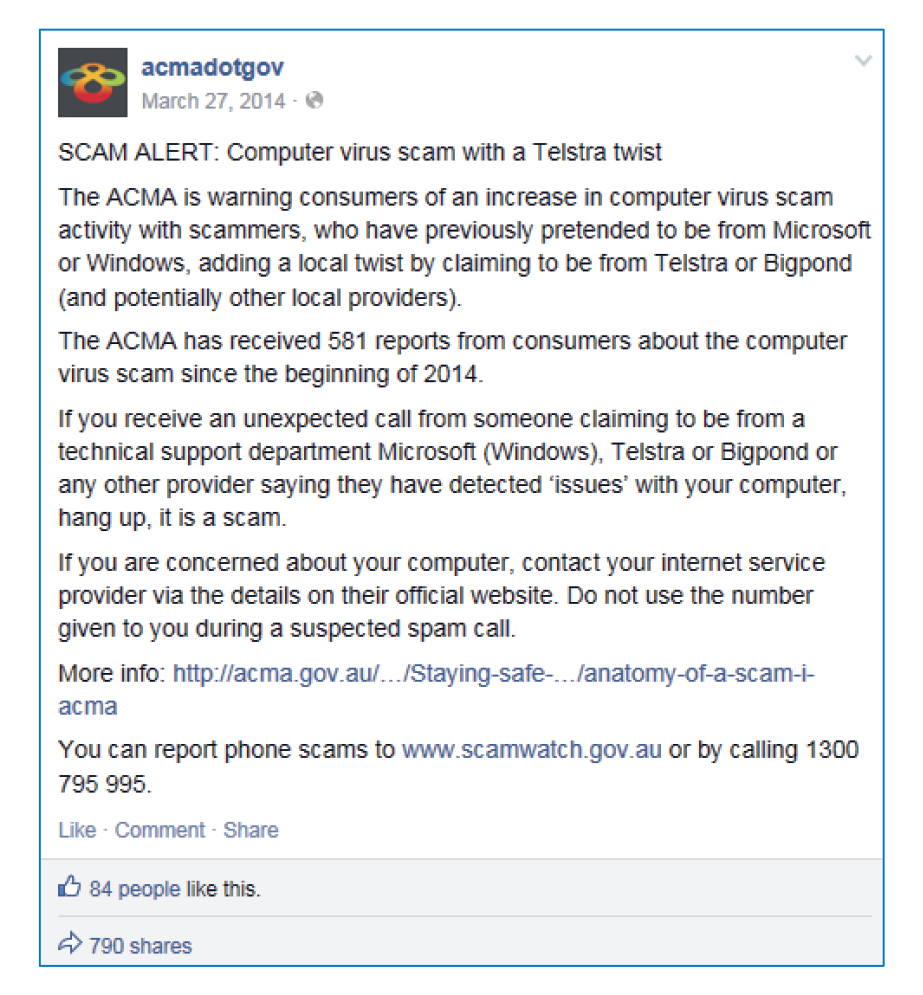

2.20 The UCB also provides announcements and links to blog posts, news articles and compliance outcomes on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. For example, the ACMA made an announcement on Facebook and Twitter when the 10 millionth telephone number was registered on the DNCR in February 2015 (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: ACMA Facebook announcement

Source: ACMA Facebook page.

2.21 Social media is also used to alert consumers to scams. For example, a post to the ACMA’s Facebook page in March 2014 warned of an emerging scam in which a caller claiming to be from a telecommunications provider would attempt to have a consumer install malware on their computer. The ACMA also used this opportunity to direct the public to the ACCC’s SCAMwatch website, as the ACCC is the federal entity responsible for responding to scams. The post was viewed by almost 50 000 people in the first 48 hours, and had been the most popular post on the ACMA’s Facebook page to date (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3: ACMA Facebook scam warning

Source: ACMA Facebook page.

Communicating enforcement action outcomes

2.22 The Australian Government Investigations Standards (AGIS) state that entities ‘are to have written procedures regarding liaison with the media and the release of media statements in regard to investigations’. In accordance with these standards, the ACMA has established written procedures regarding the release of investigation media statements. These procedures are outlined in the ACMA’s Compliance and Enforcement Manual and include specific procedures for each type of enforcement action. For example, the ACMA procedures indicate that media releases relating to infringement notices are not to be issued until the infringement notice has been paid.

2.23 Following the finalisation of enforcement activities, the ACMA may issue a media release and make the details of the enforcement action public when: a formal warning has been issued; an enforceable undertaking has been accepted; an infringement notice has been paid; or when civil proceedings have been filed.

2.24 At the conclusion of enforcement actions taken in 2013–14, the ACMA issued media releases for 79 per cent of the actions and published enforcement documents for 64 per cent of the actions, as shown in Table 2.3. All of the 2013–14 media releases that related to enforcement actions were issued in accordance with established procedures.

Table 2.3: Publication of enforcement action results (2013–14)

|

|

Total Cases (Enforcement Action Taken) |

Media Release Issued |

Enforcement Document Published |

|

DNCR |

5 |

5 |

4 |

|

Spam |

9 |

6 |

5 |

|

Total |

14 |

11 (79%) |

9 (64%) |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Assessing complaints and reports

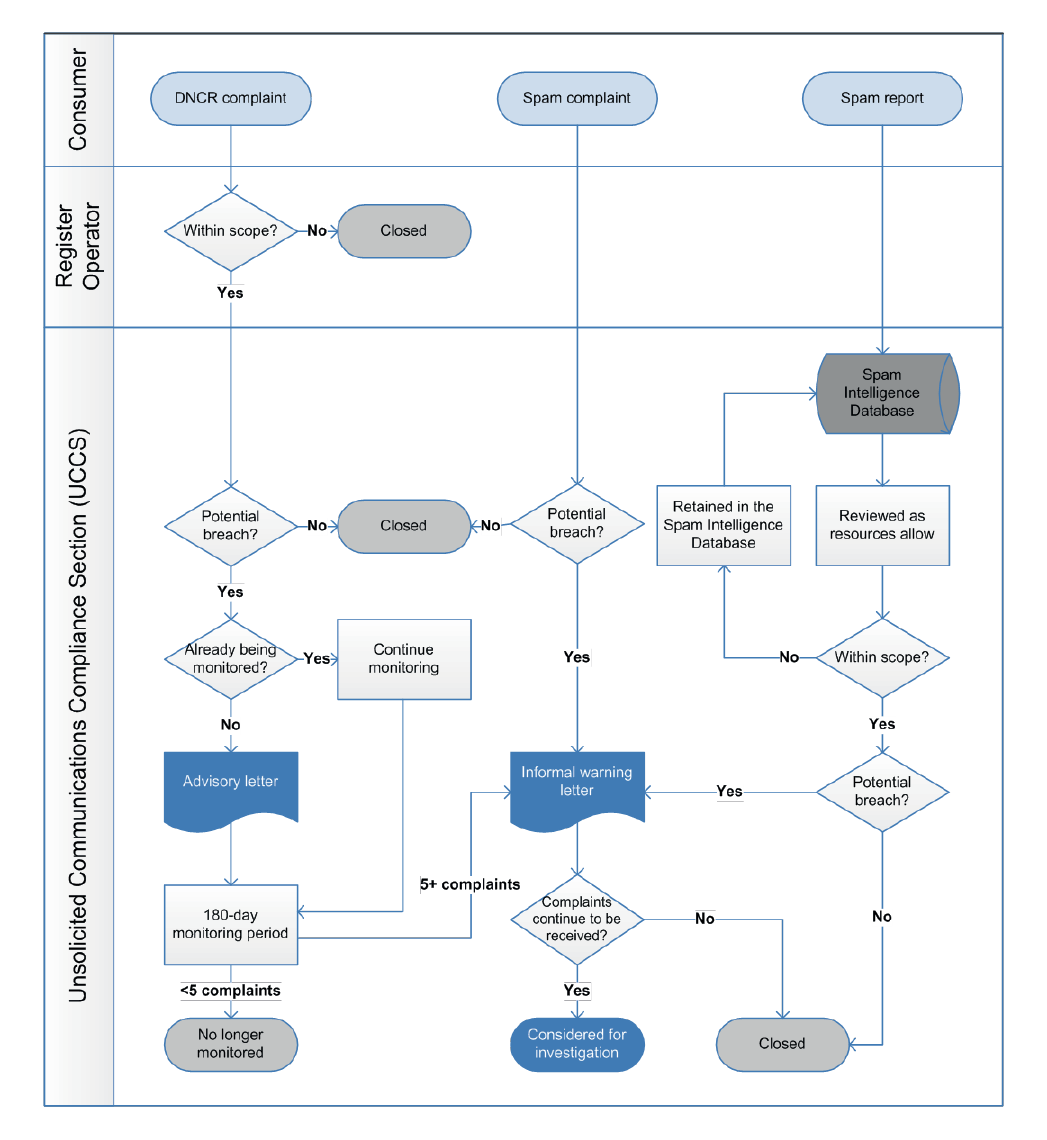

2.25 Consumer complaints and reports about telemarketing and spam are the UCCS’s primary source of compliance intelligence. The UCCS’s process for monitoring compliance with unsolicited communications legislation involves receiving and analysing complaints and reports from the public, issuing advisory and informal warning letters, monitoring potentially non-compliant entities to assess ongoing compliance and, where necessary, commencing investigations into entities that continue non-compliant activities, despite receiving warnings from the ACMA (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4: UCCS process for monitoring compliance

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

2.26 The ACMA has a Compliance and Enforcement Manual, standard operating procedures and other guidance in place to underpin the assessment of complaints and reports of unsolicited communications. In 2013–14, the ACMA received 20 462 telemarketing and fax complaints, 1387 spam complaints and 346 592 spam reports, as outlined in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: DNCR and spam complaints and reports (2012–14)

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

DNCR complaints |

19 677 |

20 462 |

|

Spam complaints |

1246 |

1387 |

|

Spam reports |

409 761 |

346 592 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

2.27 To assess how effectively the ACMA monitors compliance with unsolicited communications legislation, the ANAO examined a random sample of 271 (of 1054) DNCR compliance activities30 and 235 (of 4967) spam compliance activities for the period 2013–14.

Lodgement and assessment

2.28 Telemarketing or fax marketing complaints are made through the DNCR website or the 1300 number. These complaints are initially received and assessed by the Register Operator to determine whether the complaint is within the ACMA’s jurisdiction. Where the complaint raises a potential breach, the Register Operator forwards it to the ACMA for action. The most common DNCR-related complaint involves unsolicited telemarketing calls made to a listed telephone phone number.31 Where no potential breach has taken place, the Register Operator resolves the complaint. The ACMA is to review the initial assessment and amend it where necessary. In general, the ACMA does not amend the initial assessment by the Register Operator, with only one per cent (2 of 193) of the initial assessments in the ANAO’s sample amended.

2.29 Spam complaints are typically lodged through an online form on the ACMA website, but complaints can also be made by telephone. The most common spam-related complaint involves a company that has sent a commercial email without first obtaining consent.32 Complaints and reports are processed by compliance officers, who assign themselves specific cases in the relevant case management system.33

2.30 Direct spam reports are made by forwarding an unsolicited email to the ACMA’s reporting email address or forwarding an unsolicited SMS to a dedicated telephone number. Of the reports reviewed by the ACMA in 2013–14, the most common breach identified related to an email that had been sent without the consent of the recipient. As outlined earlier, reports of spam are stored in the ACMA’s Spam Intelligence Database. The ACMA receives an average of 950 direct spam reports each day, with complaints taking priority over reports. Compliance officers review spam reports in the Spam Intelligence Database, as resources allow, and, if it is determined that a message appears to be commercial and has sufficient information to identify the sender, it is transferred to the spam case management system for processing.

Scope of complaint

2.31 Once complaints are assigned to a compliance officer, the scope of the complaint is assessed to confirm that it is within the ACMA’s regulatory jurisdiction. To be actioned, complaints must relate to a potential breach of the:

• Do Not Call Register Act 2006 (DNCR Act);

• Spam Act 2003;

• Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard 2007; and/or

• Fax Marketing Industry Standard 2011.

2.32 For DNCR complaints, compliance officers confirm that the complainant has been registered on the DNCR for at least 30 days. Complainants do not, however, need to be registered to make complaints related to the industry standards.

2.33 For spam complaints and reports, compliance officers must determine whether the message: is a commercial electronic message34; has an ‘Australian link’; and is not a designated commercial electronic message.35

Australian link for spam complaints and reports

2.34 According to section 16(1) of the Spam Act, ‘a person must not send, or cause to be sent, a commercial electronic message that: (a) has an Australian link’. Section 7 of the Spam Act states that a commercial electronic message has an Australian link if, and only if:

(a) the message originates in Australia; or

(b) the individual or organisation who sent the message, or authorised the sending of the message, is: (i) an individual who is physically present in Australia when the message is sent; or (ii) an organisation whose central management and control is in Australia when the message is sent; or

(c) the computer, server or device that is used to access the message is located in Australia; or

(d) the relevant electronic account-holder is: (i) an individual who is physically present in Australia when the message is accessed; or (ii) an organisation that carries on business or activities in Australia when the message is accessed; or

(e) if the message cannot be delivered because the relevant electronic address does not exist—assuming that the electronic address existed, it is reasonably likely that the message would have been accessed using a computer, server or device located in Australia.

2.35 The ANAO examined a sample of 235 spam cases to determine whether an Australian link had been established. While for 97 per cent (229 of 235) of cases, the Australian link was apparent, the ACMA had not demonstrated that an Australian link had been established for the remaining six cases. All six cases related to a report (and not a complaint) and a company that was based overseas.36 The ACMA informed the ANAO that, although it is required to establish an Australian link before issuing a formal adverse finding against an entity, it does not establish an Australian link prior to issuing spam-related informal warning letters, as it considers it reasonable to operate on the assumption that consumers will complain or report about only those spam messages that have an Australian link.

Compliance history

2.36 The decision to respond to potential non-compliance can be informed by the compliance history of the party in question.37 To accurately record the compliance history of a person or company and to inform any future compliance activity, compliance officers attempt to assign the complaint to the appropriate entity in its case management system. Because some companies use a variety of trading names, compliance officers use a number of tools and methods to identify the relevant company.

2.37 The ANAO found that 33 per cent of entities against which DNCR complaints were made were identified in the ACMA’s database of potentially non-complaint entities38, and 46 per cent of spam complaints related to entities that had a prior history of potential non-compliance with the Spam Act.

2.38 The history of DNCR complainants is also reviewed by the ACMA when assessing new complaints. When providing acknowledgement that a DNCR complaint has been received, the ACMA will note any previous complaints by the complainant against different or the same entities. The ANAO found that 42 per cent of consumers who made a complaint in 2013–14 had made a previous complaint.

Responding to the complainant

2.39 Prompt acknowledgement that a complaint has been received, including an outline of the complaint process, is an important element in managing the complainant’s expectations and reassuring them that their complaint is receiving attention.39

2.40 Compliance officers are to respond to complainants to acknowledge that their complaints have been received. In 2013–14, the ACMA responded to 97 per cent of DNCR complaints and 81 per cent of spam complaints. For DNCR responses, there is a standard response template that the ACMA modifies for about half (47 per cent) of responses to note any previous complaints and to inform the complainant if the entity is already being monitored for previous cases of potential non-compliance. In relation to spam complaints, a standard response is generally issued automatically on receipt, but due to an IT issue with the new case management system, not all ‘auto responses’ were sent between October 2013 and February 2014.40 The ANAO’s analysis of response rates and times is outlined in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Complaint response rates and times (2013–14)

|

Type of Complaint |

Response Rate |

Average Response Time |

|

DNCR Act complaint |

97% |

5 days |

|

Spam Act complaint |

81% |

1 day(1) |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Note 1: Responses to Spam Act complaints are generally issued automatically on receipt.

Assigning potential breach types

2.41 Compliance officers are to assess complaints and reports to determine which, if any, potential breaches of legislation have occurred. In 2013–14, the majority of potential DNCR breaches identified by the ACMA related to the DNCR Act—particularly, section 11, which prohibits telemarketers from calling a number on the register. The majority of the potential spam breaches identified through consumer complaints related to section 16 of the Spam Act, which prohibits commercial emails being sent without consent.41

2.42 The 193 DNCR advisory letter cases and the 235 informal warning letter cases examined by the ANAO related to 174 potential breaches of the DNCR Act, 98 potential breaches of telemarketing and fax marketing standards and 267 potential breaches of the Spam Act, as outlined in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6: Identified potential breaches in ANAO sample (2013–14)

|

Legislative Instrument |

Number of Potential Breaches Identified |

|

DNC |

|

|

DNCR Act section 11: Calling a number on register |

165 |

|

DNCR Act section 12: Faxing a number on register |

9 |

|

DNCR Act Total |

174 |

|

Fax Marketing Industry Standard 2011 |

13 |

|

Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard 2007 |

85 |

|

Standards Total |

98 |

|

DNCR Total |

272(1) |

|

Spam |

|

|

Section 16: Messages must not be sent |

175 |

|

Section 17: Messages must include accurate sender information |

41 |

|

Section 18: Messages must contain a functional unsubscribe facility |

51 |

|

Spam Total |

267(1) |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Note 1: These figures do not align with the sample numbers because each compliance case could involve the identification of more than one potential breach.

Timeliness

2.43 The complaints and reports examined by the ANAO were initially assessed and classified, on average, within:

• five days of receipt for DNCR complaints;

• 10 days of receipt for spam complaints; and

• 40 days of receipt for spam reports.

2.44 The UCCS has established internal key performance indicators (KPIs) for the time taken to handle complaints42 (targets have not, however, been established for handling spam reports). The UCCS has reported internally that it generally meets these targets.43 The ANAO’s analysis of 193 DNCR Act complaints and 37 Spam Act complaints against these KPIs is outlined in Table 2.7.

Table 2.7: DNCR and spam complaint handling KPIs (2013–14)

|

Key Performance Indicator |

Target |

Actual |

|

DNCR Act |

||

|

Within 7 days of receipt |

50 per cent |

60 per cent |

|

Within 14 days of receipt |

75 per cent |

86 per cent |

|

Within 21 days of receipt |

90 per cent |

91 per cent |

|

Spam Act |

||

|

Within 8 days of receipt |

90 per cent |

75 per cent |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

2.45 As outlined in Table 2.7, in 2013–14, 91 per cent of DNCR complaints were handled within 21 days of receipt, with the remaining nine per cent of cases handled within 22 to 119 days. For spam complaints, 75 per cent were handled within 8 days of receipt, with IT issues—related to the transfer to a new case management system—causing delays in assessing and classifying complaints received between September 2013 and February 2014. In the sample examined by the ANAO, the average number of days between the receipt of a complaint or report and the issuing of an advisory letter or informal warning letter was: 11 days for DNCR complaints; 37 days for spam complaints; and 53 days for spam reports, as outlined in Table 2.8.

Table 2.8: Timeliness of regulatory response—issuing advisory letters (AL) and informal warning letters (IWL)

|

Complaint/ Report Type |

Average Days Between Receipt and Issuing of AL or IWL |

Minimum Days Between Receipt and AL or IWL |

Maximum Days Between Receipt and AL or IWL |

|

DNCR complaint |

11 |

1 |

119 |

|

Spam complaint |

37 |

4 |

96 |

|

Spam report |

53 |

9 |

137 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACMA information.

Responding to non-compliance

2.46 A flexible and graduated response to non-compliance can encourage compliance from regulated entities while reducing compliance costs to the regulator.44 The UCCS has adopted a tiered ‘advise, warn, investigate’ approach to DNCR non-compliance and a ‘warn, investigate’ approach to spam non-compliance.

2.47 In the first instance, for DNCR non-compliance, entities that do not have a recent history of non-compliance (over the previous 180 days) are to receive an advisory letter from the ACMA. The entity is then to be monitored for 180 days. If the entity has five or more complaints lodged against it during the monitoring period, the ACMA is to issue the entity with an informal warning letter. If non-compliance continues, the entity is to be considered for investigation and possible enforcement action.

2.48 For spam non-compliance, the ACMA may send out informal warning letters each month to entities that have been the subject of recent complaint(s) and/or report(s). If non-compliance continues, the entity is to be considered for investigation and possible enforcement action.

DNCR advisory letters

2.49 An advisory letter represents the first step in the DNCR non-compliance response strategy. The letter is sent when the first complaint is made against an entity or when a complaint is made following 180 days of previous compliance. The purpose of an advisory letter is to: advise the entity that a complaint has been received; provide information on DNCR legislation; and provide an opportunity to the entity to voluntarily comply.

2.50 Advisory letters are based on a variety of templates developed by the UCCS to respond to the various potential breaches that may be identified. The letter contains details on: the ACMA’s powers with regard to unsolicited communications; an overview of DNCR legislation; a summary of the complaint received; and a notice that additional complaints within the next 180 days may trigger additional compliance actions. The advisory letter also directs entities to ACMA educational material and contains extracts from the DNCR Act or standards that have been potentially breached. In 2013–14, the ACMA issued 940 advisory letters to entities identified as potentially in breach of the DNCR Act and industry standards. All of the 193 advisory letters in the ANAO’s sample had been retained by the ACMA and had been created using an established template.

DNCR informal warning letters

2.51 According to UCCS business rules, following the issuing of an advisory letter, compliance officers are to monitor DNCR complaints lodged against the entity for 180 days. Depending on the number of complaints received during the monitoring period, the following compliance activities may be undertaken:

• if no complaints are received, active monitoring of the entity ceases;

• if fewer than five complaints are received, additional advisory letters may be issued; or

• if an additional five (or more) complaints are received during the 180-day monitoring period, an informal warning letter may be issued.

2.52 In addition to the number of complaints received during the monitoring period, the ACMA may take into account the entity’s compliance history when determining the compliance activity to undertake. A demonstrated history of non-compliance may prompt the ACMA to proceed directly to the informal warning stage, with the ANAO observing this occurring in 15 per cent (12 of 78) of sampled DNCR informal warning letter cases.

2.53 To monitor compliance, a compliance officer is to determine, at least monthly, the number of complaints made against monitored entities within the past 180 days. In instances when an entity is approaching five complaints during the monitoring timeframe, the compliance officer may assess whether the evidence for a breach is ‘strong’ or ‘weak’, with the possibility of removing complaints with ‘weak’ evidence from the count. The DNCR standard operating procedures and UCCS business rules do not provide guidance on how compliance officers are to undertake this assessment. There would be merit in the ACMA documenting these procedures to help deliver more consistent compliance decisions.

2.54 When compliance officers determine that an informal warning letter should be sent, they are required to manually generate the letter from a template. The manual generation of letters has the potential to introduce transcription errors, with the ANAO’s analysis identifying that five per cent (4 of 78) of DNCR informal warning letters contained such errors—primarily relating to incorrect reporting of the complaint identification number or complaint date. The ACMA is aware of this issue and is in the process of moving to a more automated system to reduce these occurrences.

2.55 Informal warning letters include details on: DNCR legislation; previous non-compliance; the ACMA’s compliance strategy; and up to five recent complaints. The letters also outline further compliance actions that may be undertaken if non-compliance continues.

2.56 The ANAO found that the average time between the commencement of the monitoring period and the issuing of the informal warning letter was 160 days, with 35 per cent (23 of 65)45 of informal warning letters issued beyond 201 days (the 180-day monitoring period plus 21 days).

2.57 In 2013–14, the ACMA issued 114 informal warning letters to entities that were the subject of multiple DNCR complaints. In relation to the 193 DNCR advisory letters examined, the ANAO tracked the complaint history of the relevant entities over the subsequent 180 days and determined that 16 entities should have been issued with an informal warning letter because of five or more instances of potential non-compliance during the monitoring period. For 10 of these entities, an informal warning letter was appropriately issued. For two of these cases, notes were retained on file to indicate that the evidence for the potential breaches was reassessed as being ‘too weak’ to warrant an informal warning letter. For the remaining four entities, informal warning letters should have been sent, but were not.

Previous ANAO recommendation on regulatory action

2.58 As previously noted, the objective of the ANAO’s 2009–10 audit of the DNCR was to assess the ACMA’s effectiveness in operating, managing and monitoring the register, including compliance with legislative requirements. The audit made three recommendations that focused on IT security management practices, complaint handling and the escalation of regulatory action, including Recommendation 3:

To further improve transparency and minimise the risk of inconsistency in compliance enforcement decision making, the ANAO recommends that ACMA set minimum standards in its procedures for escalating regulatory action.

2.59 The ACMA has set minimum standards in its procedures for escalating regulatory action by:

- introducing a minimum standard for escalating the DNCR compliance response from advisory letter to informal warning letter (the receipt of five or more complaints in the 180-day monitoring period);

- establishing internal procedures for escalating DNCR compliance cases to investigation; and

- publishing information, such as the ACMA’s ‘Approach to Telemarketing Compliance’, on its website to outline its procedures and minimum standards for escalating DNCR regulatory action.

2.60 There is, however, scope to further improve the consistency and timeliness of the process for escalating compliance responses from advisory letter stage to informal warning letter stage.

Spam informal warning letters

2.61 The process for responding to spam complaints and reports differs from the DNCR process. Although informal warning letters are an escalated response to DNCR complaints, informal warning letters are the ACMA’s first point of contact with entities that are the subject of spam complaints and reports.

2.62 After spam complaints and reports are processed, the relevant entities are placed in a queue in the spam case management system. A running total is maintained of the number of complaints/reports lodged (and processed) against each entity in the queue. Each month, compliance officers are to generate informal warning letters. This process involves a template being automatically populated for each entity in the queue, and the informal warning letters are emailed directly from the case management system to the potentially non-compliant entities. In 2013–14, informal warning letters were not sent in October, December or January. According to the CCCD’s monthly management reports, this was largely due to IT issues related to the transfer to the new case management system.

2.63 The standard informal warning letter for potential breaches of the Spam Act includes:

- the number of complaint(s) and/or report(s) received since a particular date (generally the date of the first relevant complaint/report or the date of the last informal warning letter sent to the entity);

- the nature of the potential breach(es) (for example, ‘may have been sent without the permission of the recipient’);

- general information on the Spam Act, the ACMA and the e-marketing blog;

- the subject line/content of the message (when available); and

- a request that the entity take action to comply.

2.64 Informal warning letters do not, however, include:

- the date the unsolicited message was sent;

- the date the complaint(s)/report(s) were received;

- in the case of reports, the email address/mobile telephone number of the message recipient; or

- the specific sections of the Spam Act that have been potentially breached.

2.65 In response to 1387 complaints and approximately 350 000 direct reports about non-compliance with the Spam Act, the ACMA issued 4967 informal warning letters in 2013–14. The ANAO examined a random sample of 235 informal warning letters from 2013–14.46 The majority (69.5 per cent) of informal warning letters related to only one report and no complaints. All informal warning letters were retained on file and all provided information on the number of complaint(s)/report(s) and the nature of the potential breach(es).

Providing entities with sufficient information

2.66 In the ANAO’s sample, 18 per cent (42 of 235) of entities responded in writing after receiving a spam informal warning letter. Of these, 50 per cent (21 of 42) indicated that the informal warning letter did not provide sufficient information—19 of these letters were related to reports and did not provide information on the recipient of the unsolicited message. Examples of entities’ requests for further information are outlined below:

We have received your email, and are more than happy to take the appropriate steps to removing the person implied off our mailing list. To be able to do so though, we will require the name of the player who is being referred too. If you could please provide us with these details, we will in turn take the necessary steps.

***

Please note that Attachment A to your letter does not identify or list the electronic addresses that are required to be removed. Please can you forward those addresses to us so that they can be removed?

***

We take this matter seriously and want to resolve it. Are you able to provide the mobile number of the [reporter] to ensure they have been taken off our marketing list?

2.67 In response to these requests for further information, the ACMA generally replied that spam reports are made anonymously and it could not disclose further information.47

2.68 Relevant peak bodies contacted by the ANAO during the audit also commented on the utility of informal warning letters for reports of spam, with one peak body providing the following statement:

When an organisation receives a notification of alleged spam, the notification itself lacks sufficient detail for the organisation to investigate the date of the commercial electronic message and to whom it was sent. In our view, additional detail is crucial to enable targeted investigation given the volume of digital engagement undertaken within the industry.

2.69 As mentioned earlier, 69.5 per cent of the spam informal warning letters sent in 2013–14 related to only one report and no complaints. These letters appear to generate the most negative responses from entities as the letters do not provide sufficient information to allow the entity to investigate the specific issue, and the basis of the letter—only one report—on its face, may not warrant such intervention. This is particularly the case because:

• the ACMA is unable to provide the entity with sufficient information to resolve the specific issue (such as the email addresses or mobile telephone number of the message recipient);

• entities are notified, on average, 53 days after a report is made48 (and there is no restriction on how long after a message was sent that it can be reported by a consumer)—this delay reduces the effectiveness of the response, particularly as the entity is not told when the report was made;

• entities are not provided with the date of the report or the date the message was sent;

• there is a higher chance that a report (rather than a complaint) is unfounded—as it requires little effort to make a report and the reporter does not need to provide any statement or any proof that the message was sent without consent (which is the most common spam-related ‘potential breach’ identified by the ACMA);

• entities that are the subject of only one report are a lower compliance risk than entities that have multiple complaints and reports lodged against them; and

• the sending of informal warning letters imposes an administrative burden on industry and the ACMA.

2.70 There would be value in the ACMA reviewing the merits of its approach to responding to reports of spam—particularly given: