Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Reforming the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess Defence’s implementation of the five recommendations in ANAO Report No.19 2014-15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment and the related recommendation in JCPAA Report 449 Review of Auditor-General's Reports Nos. 1-23 (2014-15).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Defence (Defence) manages some $42 billion1 worth of specialist military equipment including ships, vehicles, aircraft and weapons. When one of these items is surplus to, or no longer suitable for Defence’s requirements, Defence disposes of it by either: transferring it to an Australian government agency or another government, selling it, gifting it or destroying it.

2. In 2014, the ANAO conducted a performance audit of how effectively Defence managed the disposal of specialist military equipment. This audit—ANAO Performance Audit Report No. 19 2014–15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment (the previous audit)—was tabled in February 2015 and made five recommendations (see Box 1, in Chapter 1). Four of these recommendations were aimed specifically at strengthening Defence’s approach to managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. The fifth recommendation was aimed at strengthening Defence’s approach to managing conflicts of interest and post-separation employment issues. Defence agreed to all of the recommendations.

3. The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) reviewed the previous audit in early 2015 and published its findings in August 2015.2 The JCPAA made a further recommendation for Defence, aimed at strengthening the training Defence provides to staff involved in disposing of specialist military equipment (see Box 1 in Chapter 1). In February 2016 the Government agreed to this recommendation. The JCPAA also recommended that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a follow-up audit within 12 months to provide an update on Defence’s progress towards reforming its approach to managing the disposal of specialist military equipment.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess Defence’s implementation of the five recommendations in ANAO Report No. 19 2014–15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment and the related recommendation in JCPAA Report 449 Review of Auditor-General’s Reports Nos 1–23 (2014–15).

5. To form a conclusion against the objective the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence implemented the recommendations; and

- Defence effectively planned, monitored and reported on its implementation of the recommendations.

Conclusion

6. Defence has implemented the JCPAA recommendation and one of the five recommendations made in the previous ANAO audit. Defence has partially implemented the four remaining audit recommendations. While Defence planned for the implementation of all recommendations, its approach to monitoring progress was inconsistent and was not applied to the JCPAA recommendation. Defence’s process for determining that audit recommendations are implemented did not work effectively when applied to two of the previous audit’s recommendations. These recommendations were closed prematurely and without independent assurance to the Defence Executive by the Defence Audit and Risk Committee.

|

Recommendation |

Status |

|

JCPAA recommendation Staff training and hand-over briefs |

Implemented |

|

ANAO recommendation no. 1 Review framework of rules and guidance for disposing of equipment |

Partially implemented— significant progress made |

|

ANAO recommendation no. 2 Identify a project manager for each major disposal project |

Implemented |

|

ANAO recommendation no. 3 Identify and report significant costs for each major disposal project |

Partially implemented— limited progress made |

|

ANAO recommendation no. 4 Review guidelines for gifting Defence assets |

Partially implemented— significant progress made |

|

ANAO recommendation no. 5 Consistently apply conflict of interest and post-separation policies |

Partially implemented— work continues |

Note: See Box 1 in Chapter 1 for a full description of recommendations.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Supporting findings

Defence’s progress towards implementing the recommendations

7. Defence has made significant progress towards implementing recommendations 1 and 4 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence review and improve its framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment and gifting Defence assets.

8. There are more than 39 documents in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment. In response to the recommendations of the previous audit, Defence reviewed and revised Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, which is Defence’s principal instruction for disposing of specialist military equipment. The revised chapter is a significant improvement on the previous policy. In particular, it identifies the Assistant Secretary Disposals and Sales as the position responsible and accountable for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment; and it clarifies the roles and responsibilities of other positions and areas within Defence that are involved in the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment. As at June 2016, Defence was still undertaking work to align its policies and procedures with the revised chapter.

9. Some sections of the revised Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, Defence’s Accountable Authority Instruction 10 and Defence’s Finance Manuals that relate to the disposal of specialist military equipment, did not align with the Commonwealth resource management framework.

10. Defence has implemented recommendation 2 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence identify a project manager for each major disposal project. As at March 2016, Defence had established Integrated Project Disposal Teams to manage 19 of the 22 major disposal projects it was undertaking. All of these teams were chaired by a Director from Defence’s Disposal and Sales Branch, which is responsible for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. In practice the chair of a project team is responsible for completing a disposal in accordance with Defence requirements.

11. Defence has made limited progress towards implementing recommendation 3 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence identify and report on all significant costs associated with each major disposal project. Defence began work towards implementing this recommendation on 30 June 2016, when it made Group Chief Finance Officers responsible for certifying the costs associated with disposing of an item of specialist military equipment. This work remains ongoing.

12. Defence continues to work towards implementing recommendation 5 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence reinforce and consistently apply its conflict of interest declaration and post-employment notification policies across the organisation. In February 2016, Defence completed an internal audit of how it managed conflict of interest declarations and post-separation employment notifications. The internal audit made seven recommendations which Defence agreed to implement.

13. Defence has implemented the JCPAA’s recommendation that Defence develop comprehensive training programs and handover briefs for all staff new to the Disposals and Sales Branch. Defence has developed a set of PowerPoint slides to present to new Disposal and Sales Branch staff as part of their induction training and has identified a number of training courses that all Disposal and Sales Branch staff will undertake as part of their professional development. Record keeping in relation to staff training, and instruction procedure briefings was poor. Defence now develops a suite of documents for each major disposal project that forms a handover brief for any staff newly assigned to work on a project.

Defence’s management of implementing the recommendations

14. Defence planned its implementation of the recommendations of the previous audit and the JCPAA recommendation, but its approach to monitoring implementation was inconsistent and two of the recommendations were closed before they were implemented.

- Defence did not apply its established monitoring process to the JCPAA recommendation.

- Defence did not report to its Audit and Risk Committee on its progress towards implementing the audit recommendations.

Summary of Defence’s response

Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the audit report on Reforming the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment.

The Department of Defence has made significant progress to achieving recommendations which proposed improvement to, and review of, its framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment. Additionally, policy in relation to disposals through the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual has been revised and enhanced. Defence is working towards implementation of other recommendations and is on track to achieve these.

Defence has also implemented the JCPAA recommendation that comprehensive training programs and handover briefs for all new staff to the Disposals and Sales Branch be provided. Staff now receive a formalised induction to the branch and can access training programs as part of ongoing professional development.

Defence has further strengthened its process of closure of ANAO recommendations going forward. A new review process is now in place to ensure that the Management Action Plan proposed by Defence for all future audits aligns with the intent of ANAO Recommendations. Further to this, SES Band 2 sign off is now required on all ANAO closure packs.

1. Background

1.1 The Department of Defence (Defence) manages Commonwealth assets worth some $80 billion and over half of these assets are items of specialist military equipment3, including ships, vehicles, aircraft, and weapons. Defence disposes of these items when they are either surplus to, or no longer suitable for Defence’s requirements.

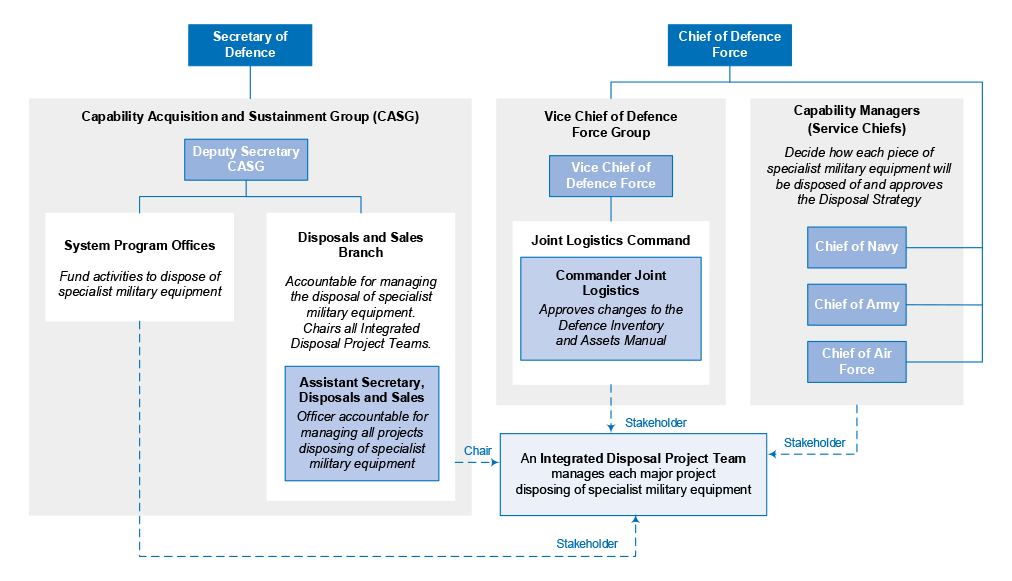

1.2 Figure 1.1 shows the current high-level organisational arrangements within Defence for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment.

Figure 1.1: Organisational arrangements for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

1.3 As at 1 March 2016, Defence was undertaking 33 projects to dispose of items of specialist military equipment. These projects are listed in Appendix 2. Defence was managing 22 of these projects as major projects and had established Integrated Disposal Project Teams to oversee 19 of them. Defence was managing the remaining 11 projects as either minor or heritage projects.

The previous audit and the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit’s review

1.4 ANAO Performance Audit Report No. 19 2014–15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment (the previous audit) was tabled in February 2015. In the previous audit, the ANAO made five recommendations, four of which were aimed specifically at strengthening Defence’s approach to managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. The fifth recommendation was aimed at strengthening Defence’s approach to managing conflicts of interest and post-separation employment issues (see Box 1 below). Defence agreed to all the recommendations.

1.5 The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) reviewed the previous audit in early 2015 and published its findings in August 2015.4 The JCPAA made a further recommendation for Defence aimed at strengthening the training Defence provided to staff new to the Disposals and Sales Branch. The Government agreed to this recommendation in February 2016. The JCPAA also recommended that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a follow-up audit within 12 months to provide an update on Defence’s progress towards reforming its approach to managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. The Auditor-General decided to undertake this performance audit in March 2016.

|

Box 1: The recommendations of the previous audit and the JCPAA review |

|

ANAO Recommendation No. 1 To rationalise and simplify its existing framework of rules and guidelines for disposal of specialist military equipment, the ANAO recommends that Defence:

The Department of Finance supported this recommendation. ANAO Recommendation No. 2 The ANAO recommends that, to improve the future management of the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment, Defence identifies, for each major disposal, a project manager with the authority, access to funding through appropriate protocols and responsibility for completing that disposal in accordance with Defence guidance and requirements. ANAO Recommendation No. 3 The ANAO recommends that, to improve the future management of the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment, Defence puts in place the arrangements necessary to identify all significant costs it incurs in each such disposal (including personnel costs, the costs of internal and external legal advice, management of unique spares and so on), and reports on these costs after each such disposal. ANAO Recommendation No. 4 To bring its instructions and guidelines that address gifting of Defence assets into alignment with the requirements of the resource management framework, the ANAO recommends that Defence promptly review all such material. This could be undertaken as part of the review recommended in Recommendation No. 1. ANAO Recommendation No. 5 The ANAO recommends that Defence:

JCPAA Recommendation No. 6 The Committee recommends that the Department of Defence develop comprehensive training programs, instruction procedures and handover briefs for all new Australian Military Sales Office staff. In February 2016, the Australian Military Sales Office changed its name to the Disposals and Sales Branch. |

Audit approach

1.6 The audit objective was to assess Defence’s implementation of the five recommendations in ANAO Report No. 19 2014–15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment and the related recommendation in JCPAA Report 449 Review of Auditor-General’s Reports Nos 1–23 (2014–15).

1.7 To form a conclusion against the objective the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence implemented the recommendations; and

- Defence effectively planned, monitored and reported on its implementation of the recommendations.

1.8 The scope of this follow-up audit was whether Defence had implemented the five recommendations of the previous audit and the JCPAA recommendation, a year after the previous audit tabled. This audit did not review Defence’s progress in addressing the full range of issues identified in the previous audit.

1.9 The ANAO reviewed Defence records and interviewed relevant Defence personnel.

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $240 519.

2. Defence’s progress towards implementing the recommendation

Areas examined

This Chapter examines Defence’s progress towards implementing the recommendations of the previous ANAO audit and the related JCPAA recommendation.

Conclusion

Defence has implemented the JCPAA recommendation and one of the five recommendations made in the previous ANAO audit. Defence has partially implemented the four remaining audit recommendations. Of these four recommendations, Defence has made significant progress towards implementing two, and continues to implement one. Defence has made limited progress towards implementing the recommendation relating to identifying and reporting on the significant costs associated with each major disposal project. This recommendation will require ongoing management attention to ensure its timely implementation.

2.1 Figure 2.1 summarises Defence’s approach to, and progress in implementing the five recommendations of the previous audit. Defence did not use this approach to implement the JCPAA recommendation.

Figure 2.1: Implementing the recommendations of the previous audit

Note: Defence’s Audit Recommendation Management System is a database on the Defence network.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence process.

Has Defence reviewed and improved its framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment and gifting Defence assets? (ANAO recommendations 1 and 4)

Defence has made significant progress towards implementing recommendations 1 and 4 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence review and improve its framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment and gifting Defence assets.

There are more than 39 documents in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment. In response to the recommendations of the previous audit, Defence reviewed and revised Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, which is Defence’s principal instruction for disposing of specialist military equipment. The revised chapter is a significant improvement on the previous policy. In particular, it identifies the Assistant Secretary Disposals and Sales as the position responsible and accountable for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment; and it clarifies the roles and responsibilities of other positions and areas within Defence that are involved in the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment. As at June 2016, Defence was still undertaking work to align its policies and procedures with the revised chapter.

Some sections of the revised Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, Defence’s Accountable Authority Instruction 10 and Defence’s Finance Manuals that relate to the disposal of specialist military equipment, did not align with the Commonwealth resource management framework.

2.2 The previous audit found inconsistencies between documents in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment, and that this framework:

- presented a confused picture of who was responsible for what when disposing of an item of specialist military equipment;

- did not correctly reflect the rules for gifting Commonwealth assets established by the Commonwealth resource management framework; and

- lacked a well-defined and robust process for conducting a tender, and practical procedures for disposing of specialist military equipment.

2.3 These findings informed recommendations 1 and 4 of the previous audit which proposed that Defence review its framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment and gifting in order to ensure: that it is concise, complete and correct; and that all instructions and guidelines for gifting Defence assets align with the Commonwealth resource management framework. Defence agreed to both these recommendations.

Improving Defence’s framework of rules, instructions and guidelines

2.4 At the time of the previous audit, Defence’s principal instruction for disposing of specialist military equipment was Defence Instruction (General) LOG 4-3-008 Disposal of Defence Assets. In December 20145, Defence replaced this instruction with a new chapter in its Defence Inventory and Assets Manual. Chapter 10 of this manual is now the principal instruction for disposing of specialist military equipment and refers to more than 39 other documents—including Australian legislation; international obligations; and Defence policies and procedures (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment

Note: This is not a comprehensive list of all legislative instruments, policies and procedures referenced by the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, Chapter 10 Defence Disposal Policy.

Source: ANAO from Department of Defence documents.

2.5 Defence assigned responsibility for implementing recommendations 1 and 4 of the previous audit to Joint Logistics Command, the area with the authority for changing the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, but not all the other documents in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment.6

2.6 As set out in the Management Action Plan, Joint Logistics Command established a Disposal Policy and Functional Reform Project; and in April 2015 started a review of the newly released Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual and other high level disposal policy documents. During this review Joint Logistics Command requested that each Defence Service and Group report back to them on:

- the roles and responsibilities for disposing of Defence property within their Group or Service; and

- the legislative requirements, policies, rules and guidelines that governed those roles and responsibilities.

2.7 The terms of reference for the Disposal Policy and Functional Reform Project stated that the project would: clarify the legislative requirements, policies, rules and guidelines that governed the disposal of Defence property; and revise Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual to align with these legislative requirements, policies, rules and guidelines.

2.8 Defence released a revised version of Chapter 10 of its Defence Inventory and Assets Manual in April 2016. It reflects changes Defence has made to its arrangements for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment since the previous audit, and is a significant improvement on the Disposal of Defence Assets Instruction.7 In particular, the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual identifies the Assistant Secretary Disposals and Sales as the position responsible and accountable for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment; and it clarifies the roles and responsibilities of other positions and areas within Defence that are involved in the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment (see Figure 1.1). The Manual also sets out processes for different types of disposals and refers to the Defence Procurement Manual for information about how to conduct a tender.

2.9 The revised version of Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual requires that all Defence Groups and Australian Defence Force Services:

ensure that all processes and procedures required for the effective implementation of this policy are clearly promulgated within six months of this policy being issued.

2.10 As at June 2016 Defence was still undertaking this work.8

References to the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework

2.11 Recommendation 4 of the previous audit proposed that Defence align its instructions and guidelines for gifting Defence assets with the Commonwealth resource management framework. The previous audit noted that Defence could undertake this action as part of the review of rules and guidelines proposed by recommendation 1. The previous audit also proposed that Defence consult with the Department of Finance, which has whole-of-government responsibility for the Commonwealth resource management framework, as part of this review. Defence advised the ANAO that it consulted with the Department of Finance in January 2016.

2.12 The ANAO reviewed three documents in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment that advise on the application of the PGPA Act within Defence. The documents were:

- Accountable Authority Instruction 10—Managing Relevant Property;

- Finance Manual 2—Financial Delegations; and

- Finance Manual 5—Financial Management.

2.13 The ANAO found that in some places the wording in these documents continued to reflect the requirements of the resource management framework that applied under the superseded Financial Management and Accountability Act 19979, rather than the current requirements (see Appendix 3).

2.14 Defence has also incorporated the section of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013—Gifts of relevant property—into Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual.10 However, Defence has inaccurately summarised the requirements of the resource management framework in the chapter, stating that:

… the Finance Minister is the only Minister who can authorise the gifting of property within Defence. The Finance Minister has in turn delegated this authority in accordance with FINMAN 2 Schedule 13 Delegation to approve gifts of relevant property, to delegates within Defence.11

2.15 An accurate summary of the resource management framework’s requirements for gifting relevant Defence property is that:

- the Finance Minister is the only Minister who can authorise the gifting of relevant Defence property;

- the Finance Minister has delegated this authority to the accountable authority in Defence12, who is the Secretary of Defence; and

- the Secretary of Defence has, in turn, delegated this authority to a number of positions in Defence which are specified in Defence’s Financial Delegations Manual (FINMAN 2).13

Is Defence appointing a project manager to manage each major disposal project? (ANAO recommendation 2)

Defence has implemented recommendation 2 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence identify a project manager for each major disposal project. As at March 2016, Defence had established Integrated Project Disposal Teams to manage 19 of the 22 major disposal projects it was undertaking. All of these teams were chaired by a Director from Defence’s Disposal and Sales Branch, which is responsible for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. In practice the chair of a project team is responsible for completing a disposal in accordance with Defence requirements.

2.16 As discussed in paragraph 2.2, the previous audit found that Defence’s framework of rules and guidance for disposing of specialist military equipment presented a confused picture of who was responsible for what when disposing of specialist military equipment. Recommendation 2 of the previous audit proposed that Defence identify a project manager for each major disposal project with the authority, access to funds and responsibility to complete the project. Defence agreed to this recommendation.

2.17 In its Management Action Plan, Defence outlined that it would determine how it would identify a project manager for each major disposal project as part of its review of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual. Defence has now identified Integrated Disposal Project Teams as the key oversight body for each major disposal project. These teams comprise representatives from different areas of Defence with relevant expertise, or with an interest in addressing the issues associated with disposing of a particular item of specialist military equipment. The objective of each project team is to:

- discuss the issues that need to be addressed in order to dispose of a particular item of specialist military equipment; and

- develop a Disposal Strategy which recommends the team’s preferred method of disposal.

2.18 Defence has used project teams as part of its process for managing major disposals since at least October 2013. At that time, a review commissioned by Defence found that these teams were ‘relatively informal.’ To address the findings of the previous audit, Defence updated the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual in March 2015 to state: ‘the [Integrated Disposal Project Team] will be chaired by [Disposals and Sales Branch] Director of Disposal Projects.’14 A revised version of the manual release in April 2016 stated that: ‘the [Integrated Disposal Project Team] will be chaired by [Disposals and Sales Branch].’

Integrated Disposal Project Teams in practice

2.19 As at March 2016, Defence was managing 33 projects disposing of specialist military equipment. Of these 33 projects15, 22 were major projects and 11 were heritage and minor projects.16 In the case of the 22 major projects:

- Defence had established project teams to manage 19 of them, and these teams had met;

- Defence informed the ANAO that it had established project teams to manage a further two projects, but these teams had not yet met; and

- one project was on hold.

2.20 All 19 active project teams were chaired by a director from within Defence’s Disposal and Sales Branch who were appointed by the Assistant Secretary Disposals and Sales, the officer responsible and accountable for managing the disposal of specialist military equipment. In practice, the chair of a project team is responsible for completing each disposal in accordance with Defence requirements.

Is Defence identifying and reporting all significant costs associated with a major disposal project? (ANAO recommendation 3)

Defence has made limited progress towards implementing recommendation 3 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence identify and report on all significant costs associated with each major disposal project. Defence began work towards implementing this recommendation on 30 June 2016, when it made Group Chief Finance Officers responsible for certifying the costs associated with disposing of an item of specialist military equipment. This work remains ongoing.

2.21 The previous audit found that Defence did not have an enterprise-wide method for identifying and reporting on the significant costs for each major disposal project. When disposing of an item of specialist military equipment, Defence can incur substantial costs17, and while Defence entered these costs into its accounting system it did not always link them to the disposal of the item of specialist military equipment to which they related.

2.22 Recommendation 3 of the previous audit proposed that Defence identify all significant costs for each major disposal project and report on these costs when the project is complete. Defence agreed to this recommendation and in its Management Action Plan set out a number of actions that it would complete, by 30 June 2016, to implement this recommendation. These actions included that Defence would: identify the significant costs of disposing of an item of specialist military equipment in the Disposal Strategy for that item; have these costs endorsed by the relevant Group Chief Finance Officer; and then compare actual costs to these estimated costs at the end of the project.

2.23 Defence had made limited progress towards implementing this recommendation until the ANAO made available the preliminary findings of this audit in early June 2016. On 30 June 2016, Defence made Group Chief Finance Officers responsible for certifying that the costs associated with disposing of an item of specialist military equipment are correct, within two weeks of Defence disposing of that item. Defence also made its Director Asset Accounting responsible for providing accounting services to personnel entering costs associated with the disposal of an item of specialist military equipment into Defence’s accounting system. As at July 2016, Defence was still working towards implementing this recommendation.18

Has Defence reinforced, and consistently applied, its conflict of interest and post-separation employment policies? (ANAO recommendation 5)

Defence continues to work towards implementing recommendation 5 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence reinforce and consistently apply its conflict of interest declaration and post-employment notification policies across the organisation. In February 2016, Defence completed an internal audit of how it managed conflict of interest declarations and post-separation employment notifications. The internal audit made seven recommendations which Defence agreed to implement.

2.24 The previous audit found, in the disposal projects that it examined, a number of situations where a conflict of interest could arise. Generally, these involved individuals working for Defence who accepted positions with external organisations doing business with Defence. These findings informed recommendation 5 of the previous audit, which proposed that Defence reinforce and consistently apply its conflict of interest declaration and post-employment notification policies across the organisation.

2.25 In its Management Action Plan, Defence outlined that it would conduct an internal audit by August 2015 of how it manages conflict of interest declarations and post-separation employment notifications. Defence completed this internal audit in February 2016 and identified a need to improve its capability: to verify self-declared conflicts of interest; act on declared conflicts of interest; and identify undeclared conflicts of interest. The internal audit also found that Defence needed to update its policy framework and align it with current legislation. It made seven recommendations addressing these findings, which Defence agreed to implement.

2.26 Defence also outlined in its Management Action Plan that it would revise its conflict of interest and post-separation employment policies by 31 December 2015, and would include an article in its ‘Ethics Matters’ newsletter discussing these policies. In September 2016, Defence advised the ANAO that it was continuing to review its conflict of interest policies, and that it expected to complete this review by the end of September 2016. Defence also advised the ANAO that an article on this conflict of interest review would appear in the November 2016 issue of ‘Ethics Matters’.

Conflict of interest declarations for major disposal projects

2.27 Defence policy relating to conflict of interest requires all personnel to bring actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest to the attention of their branch heads or commanding officers, along with strategies for dealing with these conflicts. However, it is not mandatory for Defence personnel to sign a conflict of interest declaration to do this.19

2.28 Branch heads and commanding officers are responsible for assessing each situation that is reported to them, determining whether a conflict exists, and deciding which strategy is the most appropriate for dealing with the conflict. Defence requires branch heads and commanding officers to keep records of the facts surrounding each conflict of interest, and the relevant management actions taken. In addition to this, Defence requires members of its Senior Leadership Group20 to submit an annual written declaration of their financial and other interests.

2.29 For each major disposal project, the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual required the team that managed the project to develop a Legal Process and Probity Plan for the project. This plan required all personnel involved in a disposal to sign a conflict of interest declaration; and, if during the course of a disposal a conflict of interest arises, the conflicted person must declare it as soon as possible by updating their conflict of interest declaration. The plan also assigned responsibility for managing an actual, perceived or potential conflict of interest to the chair of the project team, rather than a branch head or commanding officer. The chair is expected to ‘act promptly and give such directions as they see fit to address, manage or remove the conflict where it exists.’

2.30 As at June 2016, Defence had not collected signed conflict of interest declarations for all personnel working on the 22 major disposal projects it was undertaking. In June 2016, the legal area in Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group clarified for the Disposal and Sales Branch that Defence has no mandatory requirement for personnel to sign conflict of interest declarations, but that it was good practice for all participants in a complex tender evaluation to do so. In July 2016, Defence revised the requirement in the Legal Process and Probity Plan template to state:

All APS and ADF personnel involved in the disposal (with actual, perceived or potential conflict of interest) … are required to sign a Conflict of Interest Declaration.21

Has Defence developed comprehensive training programs, instruction procedures and handover briefs for all new Disposals and Sales Branch staff? (JCPAA recommendation)

Defence has implemented the JCPAA’s recommendation that Defence develop comprehensive training programs and handover briefs for all staff new to the Disposals and Sales Branch. Defence has developed a set of PowerPoint slides to present to new Disposal and Sales Branch staff as part of their induction training and has identified a number of training courses that all Disposal and Sales Branch staff will undertake as part of their professional development. Record keeping in relation to staff training, and instruction procedure briefings was poor. Defence now develops a suite of documents for each major disposal project that forms a handover brief for any staff newly assigned to work on a project.

2.31 In August 2015, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) recommended that Defence ‘develop comprehensive training programs, instruction procedures and handover briefs for all new Australian Military Sales Office staff.’22

2.32 In February 2016, Defence informed the JCPAA that:

- all Disposals and Sales Branch personnel were studying for Diplomas of Project Management and that new-starters would undertake the same study;

- Defence had developed an induction course for all new Disposals and Sales Branch staff, and that Defence would update this course when the revised Defence Inventory and Assets Manual was released;

- Defence would mentor and provide on-the-job training for all new Disposals and Sales Branch staff; and

- Defence had briefed all Disposals and Sales Branch personnel on the use of relevant document templates, and workplace health and safety requirements.

Training programs

2.33 In June 2014, Defence undertook a training needs analysis to determine the training needs of personnel working on major disposal projects. This analysis recommended that Defence develop a new training course for these personnel. This recommendation was not adopted, and Defence decided that all Disposal and Sales Branch personnel would instead undertake a number of Defence provided courses23, including a Diploma of Procurement and Contracting and a Diploma of Project Management.24 In June 2016, Defence decided that the requirement to undertake a Diploma of Project Management would apply to all executive level personnel of the Disposal and Sales Branch, while personnel below executive level would be required to complete a project management training program.

2.34 The ANAO found that Defence had also developed a set of PowerPoint slides to present to new Disposals and Sales Branch staff as part of their induction. Defence advised the ANAO that ‘all [Disposals and Sales Branch] staff have been trained in the framework of rules and guidance for disposing of SME,’ using these PowerPoint slides. Defence had not kept records of this training.

Instruction procedures

2.35 The ANAO found that Defence had developed, and was using templates for the key project documents: Integrated Disposal Project Team Terms of Reference; Disposal Strategy; Legal Process and Probity Plan; and Disposal Implementation Plan. Defence had not kept records of who had been briefed in the use of these templates.

Handover briefs

2.36 On 29 February 2016, the JCPAA wrote to Defence requesting further information on whether Defence had developed handover briefs and/or similar documents, noting that this information had not been included in Defence’s February 2016 response to the JCPAA. In May 2016, Defence informed the JCPAA that it prepares a suite of documents to record the current status and history of each major disposal project. These documents include:

- minutes from project team meetings;

- Disposal Strategies and other project documents for each project; and

- monthly disposal project status reports which summarise key project information for each project.

2.37 The ANAO found that, as at June 2016, Defence had developed these documents for the 19 active disposal projects it was undertaking.

3. Defence’s management of the implementation of the recommendations

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Defence effectively planned, monitored and reported on its implementation of the recommendations.

Conclusion

Defence planned for the implementation of all recommendations but its approach to monitoring progress was inconsistent and was not applied to the JCPAA recommendation. Defence’s process for determining that audit recommendations are implemented did not work effectively when applied to two of the previous audit’s recommendations. These recommendations were closed prematurely and without independent assurance to the Defence Executive by the Defence Audit and Risk Committee.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one suggestion: that when Defence closes a recommendation in its Audit Recommendation Management System it should be satisfied that it has implemented the recommendation.

Did Defence plan, monitor and report on its implementation of the recommendations?

Defence planned its implementation of the recommendations of the previous audit and the JCPAA recommendation, but its approach to monitoring implementation was inconsistent and two of the recommendations were closed before they were implemented.

- Defence did not apply its established monitoring process to the JCPAA recommendation.

- Defence did not report to its Audit and Risk Committee on its progress towards implementing the audit recommendations.

Planning

3.1 Defence started preparing the Management Action Plan for implementing the recommendations of the previous audit in December 2014 and completed it by July 2015. Defence prepared the Management Action Plan for implementing the JCPAA recommendation in September 2015. These Management Action Plans addressed:

- the actions Defence would take to implement the recommendations;

- the area and senior officer within Defence responsible for undertaking each action; and

- the target date by which each action would be complete.

3.2 In September 2016, Defence advised the ANAO that, in response to the findings of this audit, it had changed its process for reviewing and endorsing Management Action Plans for implementing ANAO recommendations. These plans will now be endorsed by the relevant First Assistant Secretary or Division Head, and reviewed and approved by the First Assistant Secretary Audit and Fraud Control.

Assigning responsibility and monitoring progress towards implementing the recommendations

3.3 Defence assigned responsibility for implementing the previous audit’s recommendations and the JCPAA recommendation to different areas within Defence (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Areas within Defence responsible for implementing recommendations

|

Recommendation |

Officer responsible for implementing |

Target Date for completing actions |

|

ANAO recommendation 1, 2 and 4 |

Joint Logistics Command |

31 December 2015 |

|

ANAO recommendation 3 |

Chief Finance Officer Group |

30 June 2016 |

|

ANAO recommendation 5 |

Audit and Fraud Control Division |

31 December 2015 |

|

JCPAA recommendation 6 |

Disposals and Sales Branch |

February 2016 |

Source: ANAO summary of Defence documents.

3.4 Defence recorded the details of the previous audit’s recommendations and the Management Action Plan in its Audit Recommendation Management System. This is a database on the Defence network and is the Defence-wide system for monitoring Defence’s progress towards implementing audit recommendations. Defence required the areas responsible for implementing the recommendations to update this system, at least monthly, with details about progress. Defence did not use the Audit Recommendation Management System, or a similar system, to monitor or report on its progress towards implementing the JCPAA recommendation.

3.5 During 2015, Joint Logistics Command updated the Audit Recommendation Management System four times on its progress towards implementing the three recommendations of the previous audit for which it was responsible. In addition, it reported upwards on its progress towards implementing these recommendations in its Vice Chief of the Defence Force Group Audit Activity Weekly Report.

3.6 As at April 2016, Defence’s Chief Finance Officer Group and Audit and Fraud Control Division had not updated the Audit Recommendation Management System on their progress towards implementing the recommendations for which they were responsible.

Reporting on progress towards implementing the recommendations

3.7 Using the information in its Audit Recommendation Management System, Defence reports to the Defence Audit and Risk Committee25 and the Enterprise Business Committee26 on the number of audit recommendations it is currently implementing, and the number of these that are overdue.27 In addition, Defence reports to the Enterprise Business Committee on the progress of audit recommendations that are either overdue by more than 121 days, or considered by Defence to be of high importance.

3.8 As none of the previous audit’s recommendations were overdue by more than 121 days or considered by Defence to be of high importance, Defence was not required to report the progress of these recommendations to the Enterprise Business Committee.

Closing the recommendations

3.9 Defence closed ANAO recommendation 2 in its Audit Recommendation Management System in September 2015 and recommendations 1 and 4 in January 2016. Audit and Fraud Control Division reviewed evidence submitted by Joint Logistics Command before closing the recommendations.

3.10 Defence closed ANAO recommendations 1 and 4 while it was still undertaking work to implement them.28 The rationale provided by Joint Logistics Command for closing the recommendations was that Defence had reviewed and revised Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual.

[The] Defence Disposal Policy and Functional Reform Project led by a 1 Star Project Director established a … Disposal Integrated Project Team. … [This team] conducted a whole of Defence review and has aligned higher level policy across Defence, in the re-write of [Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual].

3.11 The revised version of Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual was still in draft form in January 2016, when Defence closed recommendations 1 and 4. Defence did so on the basis that:

…while audit recommendations requiring policy changes are normally closed after [a new policy is formally released and available for use], it is agreed that, in this case, the requirements for recommendations 1 and 4 would be met with the endorsement of the draft policy by the Defence Logistics Committee, this endorsement was given by the Defence Logistics Committee on 4 December 2015.29

3.12 The Defence Inventory and Assets Manual is only one instruction in Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment.30 Closing recommendations 1 and 4 had the effect that Defence stopped using the Audit Recommendation Management System to monitor its progress towards implementing the totality of the recommendations, which was to review and revise all Defence’s rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment.

3.13 Defence has a control process for closing audit recommendations. This process did not work effectively on this occasion because Defence lost sight of the totality of recommendations 1 and 4.

3.14 An entity’s audit committee can also play an important role in providing independent assurance to its Accountable Authority31 that actions to implement audit recommendations are appropriate and complete. The ANAO has highlighted the benefits of audit committees actively overseeing an entity’s implementation and closure of audit recommendations.32 As discussed in paragraph 3.7, Defence did not report to its Audit and Risk Committee on its progress towards implementing the previous audit’s recommendations and the JCPAA recommendation. Defence also did not involve this committee in its decision to close two of these recommendations.

3.15 The ANAO suggests that when Defence closes a recommendation in its Audit Recommendation Management System it should be satisfied that it has implemented the recommendation. An effective monitoring process, senior executive sign-offs, and audit committee scrutiny can provide assurance to the Accountable Authority.

3.16 In September 2016, Defence advised the ANAO that, in response to the findings of this audit, it had changed its process for closing ANAO audit recommendations in its Audit Recommendation Management System. Defence now requires that the relevant First Assistant Secretary or Division Head authorise that actions to implement an ANAO audit recommendation are complete.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Entity response

Appendix 2 Defence disposal projects underway as at 1 March 2016

|

Disposal project description |

Planned/actual withdrawal date |

Disposal project type |

Status of project team |

Status of Disposal Strategy |

|

|

22 Major disposals |

|||||

|

1 |

Landing Ship Heavy—HMAS Tobruk. |

July 2015 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

2 |

Adelaide Class Guided Missile Frigate (FFG)—HMAS Sydney. |

November 2015 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

3 |

Adelaide Class Guided Missile Frigates (FFG)

|

December 2017 August 2018 January 2019 |

Major |

Project team established for HMAS Darwin Other projects on hold pending outcomes of HMAS Sydney disposal. |

On hold pending outcomes of HMAS Sydney disposal. |

|

4 |

6 x Chinook CH-47D helicopters, associated support equipment and spares. |

April 2015 to July 2016 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

5 |

16 x Seahawk S-70B-2 helicopters and associated support equipment including flight simulator, aircraft maintenance trainer and spares. |

December 2018 |

Major |

Project team established |

Chief of Navy considering |

|

6 |

38 x Kiowa B206-1 helicopters and associated spares and support equipment. |

December 2019 |

Major |

Project team established |

Draft |

|

7 |

13 x Squirrel AS350BA helicopters and associated spares and support equipment. |

2018 |

Major |

Project team established |

Draft |

|

8 |

34 x Black Hawk S-70A-9 helicopters |

2018 to 2022 |

Major |

Project team established |

Draft |

|

9 |

Iroquois Helicopter Spares (8799 items) |

2007 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

10 |

Caribou Aircraft, including props, blades and spare parts 7 x aircraft, 2 x hulks, 56 containers, and 148 crates of spares. |

February 2009 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

11 |

14 x AP-3C Orion aircraft. |

Phased withdrawal from 2015 to 2019. |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

12 |

Up to 71 x FA/18A and 18B Hornet aircraft, and unspecified number of F404 engines. |

Phased withdrawal from 2019 to 2023 |

Major |

Project team established |

Draft |

|

13 |

PC-9 Pilatus pilot training aircraft (unspecified number) |

December 2019 |

Major |

First meeting scheduled July 2016. (Defence advice) |

Draft |

|

14 |

Up to 12 300 vehicles, comprising:

|

November 2012 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

15 |

50 x Truck, Aircraft Loading (TALU) including Truck, Aircraft Side Loading (TASLU); and Truck, Aircraft Loading Unloading (Super TALU 74) Project also includes a number of Marco Airfield Rollers. |

March 2016 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

16 |

201 x M113A1—Tranche 2: Scrapping 31 x M113A1—Tranche 1: Heritage |

2013 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

17 |

Hamel Guns (L119)— 104 x guns and 108 x Abbot Conversion Kits |

2014 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

18 |

35 x M198 Howitzer |

2013 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

19 |

4288 x RT—F200 Raven Radio (disposal on hold until re-use option considered) |

2015 |

Major |

Project on hold |

Draft |

|

20 |

Ground Telecommunications Equipment assets (various) |

2018 to 2020 |

Major |

Project team established |

Draft |

|

2 Government-to-Government sales (Major disposals) |

|||||

|

21 |

5 x Weapon Locating Radar AN/TPQ-36 |

2012 |

Major |

Defence informed the ANAO that Defence has established a project team, but this team has not yet held a meeting. |

Approved |

|

22 |

3 x Landing Craft Heavy ex-HMA Ships Balikpapan, Betano, and Wewak |

2014 |

Major |

Project team established |

Approved |

|

8 Heritage disposals |

|||||

|

23 |

1 x Wessex helicopter (Training aid, single airframe, no inventory) |

1989 |

Heritage |

Defence has decided that a project team is not necessary for this disposal as it is not a major disposal. |

Draft |

|

24 |

Various assets to Australian War Memorial:

|

Unknown |

Heritage |

As above |

Various stages from draft to approved. |

|

25 |

185 (approx.) x M16A1 rifles |

c. 1989 |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

26 |

56 (approx.).303 calibre heritage weapons |

c. 1950s and before |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

27 |

65 x Legacy Heritage Weapons—Self Loading Rifles (SLR) |

Heritage |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

28 |

39 x Legacy Heritage Weapons—M2A2 Howitzer |

Heritage |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

29 |

37 x Legacy Heritage Weapons—M60D Helicopter Door Machine Gun |

Heritage |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

30 |

46 x Legacy Heritage Weapons—0.30 Cal Machine Gun |

Heritage |

Heritage |

As above |

Approved |

|

3 Minor disposals |

|||||

|

31 |

1 x Australian Submarine Rescue Vehicle Remora, Launch and Recovery System and associated support equipment. |

2007 |

Minor |

Defence has decided that a project team is not necessary for this disposal as it is not a major disposal. |

Draft |

|

32 |

3 x Chubby MK1 Mine Detection Equipment |

2004 |

Minor |

As above |

Approved |

|

33 |

Ex-HMAS Hobart Fire Control System radar equipment |

c.2002 |

Minor |

As above |

Approved |

Source: ANAO from Department of Defence information.

Appendix 3 Examples of Defence documents which are not aligned with the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework

|

Defence document & section |

Wording in document |

ANAO comment |

|

Accountable Authority Instruction 10 Section 10.12.1.1.2 |

The Commonwealth’s general policy on the disposal of relevant property is that, wherever it is economical to do so, the property should be sold at market price or transferred (with or without payment) to another Commonwealth entity with a need for the property. |

This wording reflects Section 17.2 of the Financial Management and Accountability (Finance Minister to Chief Executives) Delegation 2010, which was made under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997. The current overarching principle for disposing of Commonwealth property is set out in Section 10.2 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Finance Minister to Accountable Authorities of Non-Corporate Commonwealth Entities) Delegation 2014 which is made under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. Section 10.2 (see below) removes the requirement for the entity disposing of the property to transfer it to another Commonwealth entity only if it is economical to do so. This condition now applies only if the entity is selling the property at market value.

|

|

Finance Manual 2: Financial Delegations Manual Schedule 15—Delegation to approve the disposal of relevant property Secretary’s Directions no. 3 |

Where it is economical to do so, relevant property is to be disposed of by:

|

As above. |

|

Financial Manual 5: Financial Management Manual Section 2.6.18—Gifting |

Defence’s policy for the disposal of relevant property is that the most economical means is to prevail, wherever practical. The property being disposed of is to either be sold at market price in order to maximise the return to the government or transferred (with or without payment) to another government agency with a need for such assets. A departure from that policy, encompassing disposal by gifting, is permitted if the relevant property in question is:

|

As above. In addition, Section 10.2 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Finance Minister to Accountable Authorities of Non-Corporate Commonwealth Entities) Delegation 2014 (see below) also permits an entity to depart from Commonwealth’s overarching principles for disposing of Commonwealth property if the property is of low value and is either otherwise uneconomical to dispose of, or the gifting of it supports an Australian Government policy objective.

|

Source: ANAO analysis

Footnotes

1 This valuation of Defence’s specialist military equipment is as at June 2015.

2 Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Report 449 Regional Development Australia Fund, Military Equipment Disposal and Tariff Concessions, Review of Auditor-General Reports Nos 1–23 (2014–15) (2015).

3 These valuations of Defence’s assets and specialist military equipment are as at June 2015.

4 Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Report 449 Regional Development Australia Fund, Military Equipment Disposal and Tariff Concessions, Review of Auditor-General Reports Nos 1–23 (2014–15) (2015).

5 Two months before the previous audit was tabled in Parliament.

6 The authority for changing the other documents in this framework is spread across Defence. For example, the Chief Finance Officer Group is responsible for changes to Accountable Authority Instruction 10 and Finance Manuals 2 and 5; the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is responsible for changes to Disposal and Sales Branch templates and the Acquisition and Sustainment manual; the Defence People Group is responsible for changing the Defence Work Health and Safety Manual; and each ADF Service is responsible for its own policies and procedures.

7 The Disposal of Defence Assets Instruction was Defence’s principal instruction for disposing of specialist military equipment at the time of the previous audit.

8 In response to this audit report, Defence advised the ANAO that it is implementing an ‘Inventory Reform and Optimisation Strategy,’ and has established a committee with the responsibility for ensuring ‘that disposal policy is applied correctly’.

9 On 1 July 2014, the PGPA Act replaced the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997.

10 Defence Inventory and Assets Manual, Chapter 10 Defence Disposal Policy, Annex N, paragraph 1.

11 Ibid, paragraph 2.

12 The Finance Minister delegated this authority under section 107 of the PGPA Act and as specified in Part 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Finance Minister to Accountable Authorities of Non-Corporate Commonwealth Entities) Delegation 2014. The Finance Minister has not delegated the authority to gift military firearms.

13 In September 2016, Defence advised the ANAO that it will incorporate this summary into the next update of Chapter 10 of the Defence Inventory and Assets Manual.

14 Previously, the policy required the chair of the Integrated Disposal Project Team to be a person from the System Program Branch/Division which had been responsible for sustaining the item of specialist military equipment being disposed of.

15 See Appendix 2 for a full list of Defence’s disposal projects as at March 2016.

16 Recommendation 2 of the previous audit focused on major disposal projects. Defence does not usually use an Integrated Disposal Project Team to manage the disposal of a heritage and minor item of specialist military equipment.

17 For example, Defence estimated that the disposal of ex-HMA Ships Canberra and Adelaide cost the Commonwealth about $13 million. See ANAO Report No. 19 2014–15 Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment, p. 63.

18 For example, Defence was updating its Finance Manuals to reflect how it required the costs associated with disposing of an item of specialist military equipment to be entered into its accounting system.

19 The Defence Procurement Policy Manual states that:

Defence officers are expected to avoid, or take steps to avoid, any actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest. In the context of procurement activity, this will usually involve the individual providing a conflict of interest declaration.

20 Defence’s Senior Leadership Group includes all Star Ranked Officers, all active Star Ranked Reserve Officers, Senior Executive Service (SES) Officers and Chiefs of Divisions.

21 In addition to this, in September 2016, Defence advised the ANAO that all staff involved in a major disposal project are ‘provided with a probity brief and a copy of [that project’s] Legal and Probity Plan’ at the start of the project.

22 In February 2016, the Australian Military Sales Office changed its name to the Disposal and Sales Branch.

23 Defence did not document the rationale for this decision.

24 The Diploma of Project Management course is provided by the Institute of Management which is a Registered Training Organisation. As at September 2016, half of the Disposal and Sales Branch personnel required to undertake the diploma had completed it.

25 The Defence Audit and Risk Committee provides independent advice to the Secretary and Chief of the Defence Force on all aspects of Defence’s governance, including audit, assurance, financial management, and risk management.

26 The Enterprise Business Committee is a subsidiary of the Defence Committee and is responsible for: Defence’s corporate planning; monitoring and reporting of Defence’s performance; Defence’s approach to managing enterprise risks; and reforming Defence’s approach to service delivery.

27 Defence categorises an audit recommendation as overdue when it has passed the target date for implementation that was agreed to in the Management Action Plan, or a subsequently revised target date.

28 Recommendations 1 and 4 related to the whole of Defence’s framework of rules and guidelines for disposing of specialist military equipment.

29 Defence consulted with the Department of Finance, as the ANAO proposed in recommendation 1, on the same day that it closed ANAO recommendations 1 and 4 in its Audit Recommendation Management System.

30 The authority for changing the other documents comprising this framework is spread across Defence. For example, the Chief Finance Officer Group is responsible for changes to Accountable Authority Instruction 10 and Finance Manuals 2 and 5; the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is responsible for changes to Disposal and Sales Branch templates and the Acquisition and Sustainment manual; the Defence People Group is responsible for changing the Defence Work Health and Safety Manual; and each ADF Service is responsible for its own policies and procedures.

31 In Defence, the Accountable Authority is the Secretary of Defence.

32 ANAO audit report No. 5, 2015–16, Implementation of Audit Recommendations (Department of Veterans’ Affairs), p. 14. See also ANAO audit report No. 25, 2012–13, Defence’s Implementation of Audit Recommendations, p. 55.