Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Recovery of Centrelink Payment Debts by External Collection Agencies

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Human Services' arrangements for engaging and managing External Collection Agencies to recover debts arising from Centrelink payments.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Department of Human Services (DHS) provides policy advice on service delivery to the Australian Government and delivers a range of health, social and welfare payments, and services to the Australian community. In 2012–13, DHS expects to deliver approximately $149.4 billion in third party payments on behalf of other Australian Government agencies.1

2. DHS makes core Centrelink payments such as Newstart Allowance on behalf of the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, and Age Pension payments on behalf of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

3. Incorrect Centrelink payments can result in underpaying or overpaying DHS customers. Debts for customers can arise from: overpayments, because customers have not notified DHS of a change in their circumstances or have provided incorrect information; or, less often, through administrative errors being made by departmental staff.2

4. DHS is required under legislation to recover all Centrelink payments to customers that have been made incorrectly.3 If a debt is raised with a current customer of DHS—someone in receipt of a Centrelink payment—then the debt cannot be recovered in such a way that the person will experience severe financial hardship.4 DHS adopts a similar approach when recovering debts from non-current customers, so as to avoid people having to return to Centrelink payments for financial support.

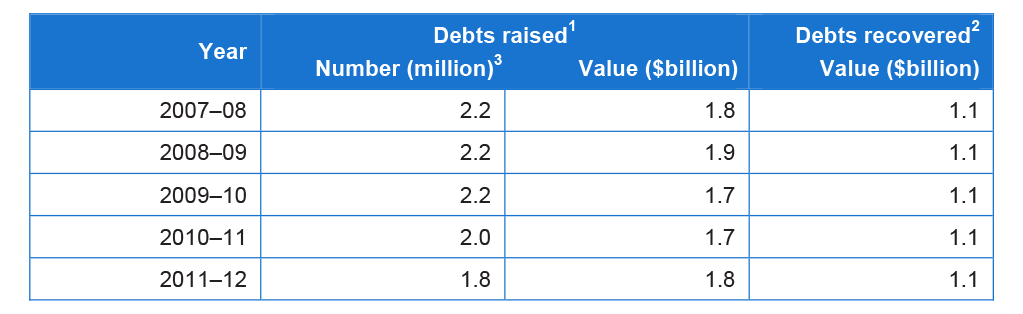

5. Debt management is an ongoing and mature function within DHS with expenditure on Centrelink payment debt recovery estimated to be $29.8 million5 in 2011–12. DHS is responsible for managing a significant number of Centrelink payment debts incurred by current and non-current customers. Table S1 presents a five-year overview of the payment debts raised and recovered by Centrelink and DHS (from July 2011).

Table S 1 Centrelink payment debts raised and recovered: 2007–2012

Source: Centrelink and DHS annual reports.

Notes:

(1) Total debts raised, including Family Assistance Office (FAO) debts. FAO debts are recovered annually at the time the FAO reconciliation is completed.

(2) Debts raised in a specific year are not always recoverable in the same year. In order not to cause financial hardship for individuals and families, repayment arrangements for debts can be lengthy. Sometimes, the contact details for non-current customers are no longer up-to-date, which extends the time required for the recovery process.

(3) The number of debts does not equate to the number of people with debts, because some current or non-current customers have more than one debt.

6. Table S 1 shows that while the number of Centrelink payment debts raised annually has declined in recent years (from 2.2 million to 1.8 million), the value of the debts recovered annually has remained at the same level ($1.1 billion). A number of factors can influence debt raising and recovery activity, including external economic conditions such as those that affected Australia during the recent global financial crisis, and the need for DHS to divert agency resources to support national disaster and emergency responses.

7. The debt base for Centrelink payments is the cumulative difference between the number of debts raised and recovered annually by DHS. The long‑term trend is for the value and age of the debt base to increase. At the end of 2011–12, the debt base was $2.5 billion and the number of debts in the debt base that were more than two years old was 455 000 (46.2 per cent of the total number of outstanding debts). However, the ratio of Centrelink payment debt to total social security payments is low: $96.97 billion in payments were made in 2011–12, compared to the debt base of $2.5 billion. DHS attributes the rising trend in the debt base in recent years to: improved compliance and detection methods, which have increased the amount of debt being detected and raised; and social security payment recipients having limited capacity to repay debts because of their financial circumstances, which makes it difficult to recover debts.

Recovering payment debt: external debt collection agencies

8. Centrelink payment debts can be repaid by current or non-current customers by: mail; telephone; in person; or online. Arrangements can also be made for electronic payment using direct debit or BPAY.

9. If a debt is not repaid and an extension of time has not been agreed, DHS can: reduce the amount of any current Centrelink payments6; garnish wages, tax refunds, other assets and income; or refer the matter for legal action.

10. Since 1996, external debt collection agencies (ECAs) have been contracted as mercantile agents7 to recover social security payment debts owing by non-current customers. The ECAs are paid a commission on the amount recovered for each debt. DHS currently contracts two private sector ECAs to undertake debt recovery for Centrelink payment debts: Dun & Bradstreet and Recoveries Corporation. The current arrangement is a standing offer for debt recovery services from both suppliers for the period February 2011–February 2014. While it is not possible to provide a final contract value, in 2012–13, DHS raised initial purchase orders for a total of $8 million (GST exclusive) to cover the expected ECA commissions.8

11. DHS debt recovery staff will attempt, in the first instance, to recover any outstanding debt from non-current customers who DHS has lost contact with. If unsuccessful, debts that meet a set of standard criteria (including that the person is no longer receiving Centrelink payments and has failed to make or maintain a recovery arrangement) can be referred to an ECA for recovery action.

12. In 2011–12, DHS recovered $1.1 billion in total debt repayments. The ECAs’ contribution to the total amount recovered was $114.3 million (10.4 per cent). While the amount recovered by DHS in the previous two years has remained the same at $1.1 billion, the ECAs’ contribution to the total amount recovered has almost doubled since 2009–10, when it was $60.8 million or 5.5 per cent.9

Audit objective, criteria and scope

13. Debt management is an established function within DHS comprising four main elements: prevention; identification; raising; and recovery. While the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has conducted two previous performance audits examining customer debt management by Centrelink10, this audit focuses on one element of debt recovery in DHS—the arrangements for external debt recovery of Centrelink payment debts.

14. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DHS’ arrangements for engaging and managing ECAs to recover debts arising from Centrelink payments.

15. The department’s performance was assessed using three audit criteria:

- DHS effectively engages ECAs as part of a debt recovery strategy for Centrelink payment debt;

- DHS has adequate administrative and contractual arrangements for managing the services contracted from ECAs; and

- performance monitoring by DHS is effective and supports management reporting and external accountability.

Overall conclusion

16. Social security law11 requires DHS to recover Centrelink payment debts from current and non-current customers, and government partner agencies12 expect DHS to actively seek to recover debts that have arisen because of customer error or administrative error made by departmental staff. Payment debt recovery is an ongoing function within DHS with more debt raised than is recovered annually. In 2011–12, DHS raised 1.8 million new Centrelink payment debts13, valued at $1.8 billion, and the department recovered $1.1 billion in outstanding debts. Also in 2011–12, DHS referred Centrelink payment debts—when a debt recovery arrangement was not made or maintained by a non-current customer—to a panel of external collection agencies (ECAs)14 for recovery.15 The referrals were valued at $703.7 million. The ECAs recovered $114.3 million, which was 16.2 per cent of the value of the debts referred16, and approximately 10 per cent of the total debt recovered by the department in 2011–12 ($1.1 billion). The Centrelink payment debt base, which is the cumulative difference between the number of debts raised and recovered annually by DHS, was $2.5 billion in June 2012.

17. By way of background, almost two decades ago in 1996 the then Department of Social Security identified the potential for ECAs to undertake social security payment debt recovery.17 The use of ECAs at that time was seen as offering a new way to locate customers that the department could not, and to cost-effectively recover certain debts. In 2012, DHS reviewed the debt operating model for non-current customers, which includes the use of ECAs, but did not form a view about the ongoing role of ECAs in undertaking debt recovery on its behalf. However, with the department’s current ECA contracts scheduled for review before February 201418, there is an opportunity for DHS to determine the future role of ECAs in recovering Centrelink payment debts.

18. The department’s administration of the current ECA contracts for the delivery of Centrelink debt recovery services is generally effective, and DHS has a constructive working relationship with the ECAs. DHS is largely compliant with key contractual requirements for the provision of customer data to the ECAs. The quality of the data being referred to the ECAs is also sufficient to conduct Centrelink payment debt recovery on behalf of DHS and, during the current contracts with the ECAs, no significant issues have been identified with the IT systems used by DHS to manage and transfer debt data to the ECAs.

19. However, there is room for improvement in DHS’ administration of two important activities under the current contracts: the administration of contract variations and the conduct of formal audits of the operation of key contractual requirements. There would be benefit in the department examining opportunities to avoid a recurrence of the lengthy delay, of over a year, in formalising a recent contract variation with the ECAs relating to an important operational change. Further, DHS has not undertaken any formal audits, since the contracts began, of the IT, physical and personnel security requirements contained in the contracts. DHS’ current approach to auditing under the contracts is not supported by a risk assessment, and an appropriately designed audit program, or similar approach, would provide assurance to DHS that customer information is being managed securely by the ECAs.

20. The general reporting and monitoring framework established by DHS for management of the ECA contracts is appropriate. There is sufficient management information available to effectively support DHS’ monitoring of the ECAs and, overall, the ECAs’ reporting is consistent with the contractual requirements. DHS also has processes in place to respond to feedback or complaints received from customers about the quality of their experience with the ECAs. There is, however, scope for DHS to improve the level of information available about the ECAs’ recovery work in its annual report, which would improve the level of transparency for this relatively small, but high profile activity.

21. The ANAO has made one recommendation to improve DHS’ administration of external debt recovery services for Centrelink payment debts. The recommendation focuses on DHS verifying compliance with key contractual obligations for the ECAs to ensure that DHS customer information is managed securely.

Key findings

Debt Recovery Strategy and External Collection Agencies (Chapter 2)

22. To support the achievement of service delivery outcomes for the Government, DHS needs to have in place clear policy and operational guidance for its staff and stakeholders. At an operational level, e‑Reference—an online reference tool for staff to access guidance on policies and procedures—supports the conduct of debt recovery activities in DHS’ national network.

23. DHS is considering alternative future models for debt recovery. A recent review of the debt operating model for non-current customers showed that DHS has not determined what the future role of the ECAs should be. However, this work provides a sound basis from which DHS can develop a strategy to inform decision-making about the future direction of debt recovery in the agency across a number of payment programs, including the Medicare program.

Contract Management and Services (Chapter 3)

24. The department’s administration of key elements of the ECA contracts for the delivery of Centrelink debt recovery services is generally effective, and DHS has established a constructive relationship with the ECAs based on successfully working together over a number of years.

25. While reviews of the Service Level Agreement with the ECAs have been conducted by DHS in accordance with the requirements in the Head Agreements, there is scope for DHS to improve its administration of two important activities under the contract. DHS’ administration of formal contract variations has been mixed, with a lengthy delay in formalising a variation to reflect an operational change made over a year earlier. Further, DHS has not conducted formal audits of the ECAs’ compliance with requirements in the Head Agreements for IT, physical and personnel security that protect DHS customer information. Given the potential benefit for DHS of increased assurance about those key aspects of contract management, and particularly in light of the relocation of one of the ECAs’ business centres in December 2012, there would be merit in DHS undertaking an audit or similar activity in the near future to verify the ECAs’ compliance with contractual requirements.

26. ANAO analysis of debt data, collected between August 2012 and February 2013, showed that DHS was largely compliant with key contractual requirements for the provision of customer data to the ECAs19 and the data provided to the ECAs was consistent with the expected operation of the Debt Management Information System (DMIS).20 The quality of the data referred to the ECAs was sufficient to enable them to conduct Centrelink payment debt recovery on behalf of DHS. During the current contracts with the ECAs, no significant issues have been identified with the IT systems used by DHS to manage and transfer debt data to the ECAs and, in 2011–12, DHS successfully implemented major changes to DMIS for ECA debt recovery. During the six‑month period from August 2012–February 2013, 99.7 per cent (approximately 153 000) of the debt referrals made by DHS to the ECAs were for individuals with payment debts, and the remaining 477 debt referrals (0.3 per cent) were for organisations with debts due to the payment of Paid Parental Leave. The value of the debts referred during the period was $368.6 million.

27. There are areas where the future direction of the ECA contracts could be varied by DHS with a view to improving performance. Currently, DHS is considering the introduction of a performance monitoring scorecard to measure and compare the ECAs’ performance in key areas such as: debt recovery; customer feedback (satisfaction and/or complaints); and compliance with contractual obligations.

Performance Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 4)

28. DHS has an appropriate reporting and monitoring framework for the management of the ECA contracts. Overall, the ECAs’ reporting is consistent with the contractual requirements and sufficient information is provided for DHS to monitor performance under the contracts. DHS is considering the future of the contractual reporting requirements and how best to tailor the content of the ECAs’ reports to meet DHS’ emerging needs. There is an opportunity for DHS to improve the quality assurance work conducted on site before the quarterly performance review meetings, which involves DHS staff listening to operators’ calls to non-current customers about their debt(s) and providing timely feedback to the ECAs.

29. DHS has processes in place to respond to feedback or complaints received from current or non-current customers.21 Complaints about the ECAs are recorded against one of four categories out of a total of 14 categories of complaints made about Centrelink debt recovery. The ECAs’ recovery activity generated 27 per cent of the total number of complaints received from customers about debt recovery. DHS also has long-standing working relationships with key government and non-government stakeholders with an interest in debt recovery and meets with the latter to discuss issues that affect their clients.

30. The ECAs’ reporting under the contracts is a sufficient basis from which DHS can generate management information for DHS staff that are responsible for implementing and overseeing debt recovery operations. However, there is an opportunity to improve the department’s external reporting of ECA activity in its annual report, which currently does not include separate reporting on the ECAs’ contribution to debt recovery compared to the total amount of debt raised and recovered annually by DHS. An alternative model of annual reporting, which merits consideration, is adopted in the Australian Taxation Offices’ annual report for 2011–12. The Australian Taxation Office reported on: the number of debt cases referred to the ECAs, including their value; and the amount of debt recovered by the ECAs.

Summary of agency response

31. DHS’ summary response is provided below:

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report and considers that implementation of its recommendation will enhance the recovery of Centrelink payment debts by External Collection Agencies. The department is committed to the introduction of security audits, consistent with the contractor’s responsibilities, for the Protection of Information contained in the Head Agreements.

This added compliance measure will increase confidence that debtor information, passed to the External Collection Agencies for the purpose of debt recovery, is secure and debtor’s privacy and confidentiality is being risk managed appropriately.

The department agrees with the recommendation outlined in the report.

32. DHS’ full response to the proposed audit report is contained in Appendix 1.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 3.18 |

The ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services periodically verify compliance with the IT, physical and personnel security requirements contained in the current contracts with external collection agencies, to gain assurance that DHS customer information is being managed securely. DHS’ response: Agreed. |

Footnotes

[1] Department of Human Services, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2012–13, DHS, Canberra, 2013, p. 15.

[2] In 2011–12, the department reported payment correctness of 97.6 per cent.

[3]Social Security Act 1991, Chapter 5, Part 5.2—Amounts recoverable under this Act.

[4] ibid., Chapter 5, Part 5.3—Methods of recovery, subsection 1231 (1AA)(a).

[5] The expenditure is DHS’ direct costs for undertaking debt recovery at the operational level, including DHS staff salaries and commission paid to external debt collection agencies. The total does not include other DHS business costs such as IT maintenance, infrastructure, and departmental services, such as records management.

[6] The standard withholding repayment rate for Centrelink payment debts is 15 per cent.

[7] Mercantile agents act as an agent for the original creditor, collecting the debt on their behalf—in this case, the Australian Government. Alternatively, debt purchaser businesses buy the right to collect the debt at a discount from the face value of the outstanding debt.

[8] Details of the contracts are available on Austender—the Australian Government’s web-based procurement information system, see <http://www.tenders.gov.au>. [accessed 28 June 2012 and 10 August 2012].

[9] In 2010–11, the ECAs’ contribution to the total amount of debt recovered was $82.2 million (7.5 per cent).

[10] ANAO Audit Report No.4 2004–05, Management of Customer Debt, and ANAO Audit Report No.42 2007–08, Management of Customer Debt—Follow-up Audit.

[11]Social Security Act 1991, Chapter 5, Part 5.2—Amounts recoverable under this Act.

[12] For example, the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

[13] The number of debts does not equate to the number of people with debts, because some current or non‑current customers have more than one debt.

[14] The panel is comprised of two private sector ECAs: Dun & Bradstreet and Recoveries Corporation.

[15] If an ECA does not receive any repayments for a debt at the end of a 180 day referral period, all debts for that individual will be recalled by DHS for consideration of further debt recovery action. DHS can also temporarily suspend recovery action for debts until a later date if, for example, an individual’s whereabouts are unknown.

[16] The Australian Taxation Office also uses ECAs to recover taxpayer debt, albeit under different contractual arrangements. In 2011–12, the agency referred $1.6 billion in debt cases to its panel of four ECAs and the amount of debt recovered was $1.3 billion (81.3 per cent of the total value referred).

[17] It was not until 2007 that the Australian Taxation Office established a panel of four ECAs to collect taxpayer debts.

[18] The contracts commenced in February 2011 for an initial three-year period. They contain an option to extend the term for two further periods of one year.

[19] The exception is data for the ‘reason for referral’. While the data is listed in the contract requirements, there is no specific data being sent to the ECAs. The referral reason in each case should be that the debt conforms to a set of standard rules for referring debts to the ECAs. For future contracts, DHS could consider deleting this redundant requirement.

[20] DMIS is a mainframe computer system in DHS that is used to manage a national database of Centrelink payment debts.

[21] In 2011–12, DHS received 51 155 complaints (representing 0.7 per cent of Centrelink customers) about Centrelink services and payments, including debt recovery.