Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Quality On Line Control for Centrelink Payments

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Centrelink’s QOL control, which supports the integrity of payments administered by DHS on behalf of the Australian Government.

Summary

Introduction

1. Every year, millions of Australians come into contact with Australian Government agencies that deliver a wide range of services to the community. Within the Human Services portfolio, Centrelink, Medicare, the Child Support Agency, CRS Australia (all within the Department of Human Services) and Australian Hearing deliver over 200 different services to the community and administer more than $130 billion in payments on an annual basis.

Reforming the delivery of human services

2. In December 2009, the Australian Government announced a redesign of the service delivery arrangements in the Human Services portfolio.1 The major structural and service delivery reforms foreshadowed were designed to improve collaboration between the human service delivery agencies and, by increasing coordination, improve access to services for the portfolio’s many and diverse customers.2

3. The Service Delivery Reform program3 is to be implemented between 2010 and 2021. Significant structural changes have already occurred, with the Department of Human Services (DHS) integrating Medicare Australia and Centrelink from 1 July 2011.4 The reconstituted DHS is responsible for the development, delivery, and coordination of government services, and the development of service delivery policy.5

Centrelink

4. In 2010–11, Centrelink was the largest single agency in the Human Services portfolio.6 Centrelink employed approximately 25 000 staff in 313 customer service centres and 25 call centres across Australia to deliver a range of services to 7.1 million customers and administer $90.5 billion in payments.7 Before July 2011, Centrelink operated in 15 defined geographical areas throughout Australia. Each area consisted of an Area Office and a number of customer service centres that delivered face-to-face services to the public. In July 2011, the Human Services portfolio, including Centrelink, moved to managing service delivery in 16 service zones across Australia, led by individual Service Leaders.8

5. Centrelink’s focus on providing high quality services to the community and ensuring payment integrity complements the Service Delivery Reform program. Payment correctness is an important element of Centrelink’s approach to quality management for assuring the integrity of payments administered by Centrelink on behalf of the Government. Centrelink defines payment correctness in terms of there being four pillars of payment correctness: right person; right program; right rate; and right date.9

Why quality and payment correctness matter

6. The nature of Centrelink’s operations makes it essential that it have in place a quality assurance framework and effective controls to support high quality service delivery, which minimises the risk of payment errors occurring. Administrative and customer error10 can result in a financial impact for customers’ payments, inconvenience to customers and/or additional work for Centrelink, and both require effective risk management. Centrelink seeks to mitigate the risk of administrative error through a range of procedural and system measures. Other key initiatives are staff training and monitoring the quality of work activities performed by staff.

7. For administrative error, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has previously reported that:

while an [administrative] error may be immaterial to payment today – such as a coding error – it represents the possibility that compliance controls could be precluded from identifying future payment inaccuracy…From this perspective, administrative errors – whether material to outlays or not – may contribute to underlying inaccuracy.11

8. A further consequence of administrative error can be a reduction in the public’s and Government’s confidence in the integrity of payments made by Centrelink.

Quality control and quality assurance

9. Centrelink’s approach to quality management in its customer operations and processing environments involves a range of quality controls and quality assurance processes. Quality controls relate to upfront, pre-payment measures and include electronic systems design and automated decision-making processes, security management for access to Centrelink systems, and delegations to perform certain work. Quality assurance processes within Centrelink refers to post-payment measures and includes Random Sample Survey (RSS) reviews12 and internal audits. Further assurance is provided about the conduct of Centrelink’s business by the publication of external audits and the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s reports.

10. The RSS is Centrelink’s primary assurance mechanism to measure the accuracy of program outlays on social security payments administered by Centrelink. Payment correctness is measured using RSS and reported in annual reports. The survey provides a point-in-time analysis of a stratified sample of customers’ circumstances designed to establish whether customers are paid accurately across the programs administered by Centrelink.

Quality On Line

11. Introduced in 2000, Quality On Line (QOL) is one of Centrelink’s main pre-payment quality control mechanisms for payment correctness. QOL is the first point of checking and is described by Centrelink as a preventative check.

12. The QOL process involves a checker reviewing a predetermined sample of a Centrelink Customer Service Adviser’s (CSA) work activities13 to check for correctness, in terms of processing a customer’s claim and the CSA’s data entry of details into Centrelink’s electronic customer database. Once an activity is entered into the database, it may be selected for QOL checking based on an assessment of risk, checked for error, and then either released for payment or returned to a CSA for correction.

13. A set of national standards for the operation of QOL is in place to provide a consistent approach to the use of QOL across the Centrelink network. Compliance with the national standards is a mandatory requirement for Centrelink staff. Centrelink records QOL checking results in order to monitor quality trends and to identify correctness rates and training needs for CSAs.

Check the Checking—quality assurance for Quality On Line

14. In response to ANAO Audit Report No.34 2000–01, Assessment of New Claims for the Age Pension by Centrelink, Centrelink introduced Check the Checking (CtC) arrangements ‘as a means of providing feedback and identifying training needs for QOL checking officers’.14 Centrelink operated a form of CtC for approximately 11 years, from 2000 to 2011, until the program was replaced in August 2011 by a new quality assessment and assurance process.

15. CtC was a quality assurance program that monitored the quality of the QOL quality control process. CtC involved rechecking a representative sample of QOL checked and released new claim activities to determine if they were checked correctly. CtC provided a limited level of assurance that QOL was an effective way to control the risk of administrative error, because QOL checks apply to both new claim and non-new claim activities (existing customer claims).15

16. Centrelink had considered the inclusion of non-new claim activities in CtC, but concluded that the complexity of retrieving paper records quickly from customer service centres, processing centres or record management storage facilities located around Australia was not feasible, and would be more difficult than checking new claim activities. Centrelink anticipates that the development of virtual QOL and the increasing use of digitised records in Centrelink will make it possible to review non-new claim activities in the future, using the replacement quality assurance process for CtC.

Overview and recent results

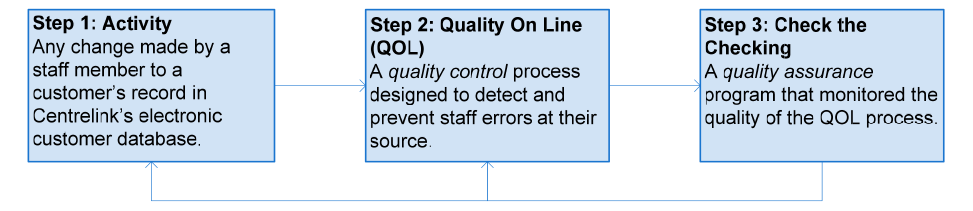

17. Figure S.1 is an overview of the respective roles of QOL and CtC and the relationship between them.16

Figure S.1: Overview of Quality On Line and Check the Checking processes

Source: ANAO analysis.

18. As shown in Figure S 1, outcomes from the QOL and CtC processes are used to correct administrative errors made by Centrelink staff when creating or changing customer records. While QOL checks are performed in close proximity to the processing of an activity—usually on the same day—CtC can be undertaken some months after a CSA processes an activity that was subsequently selected for a QOL check.17

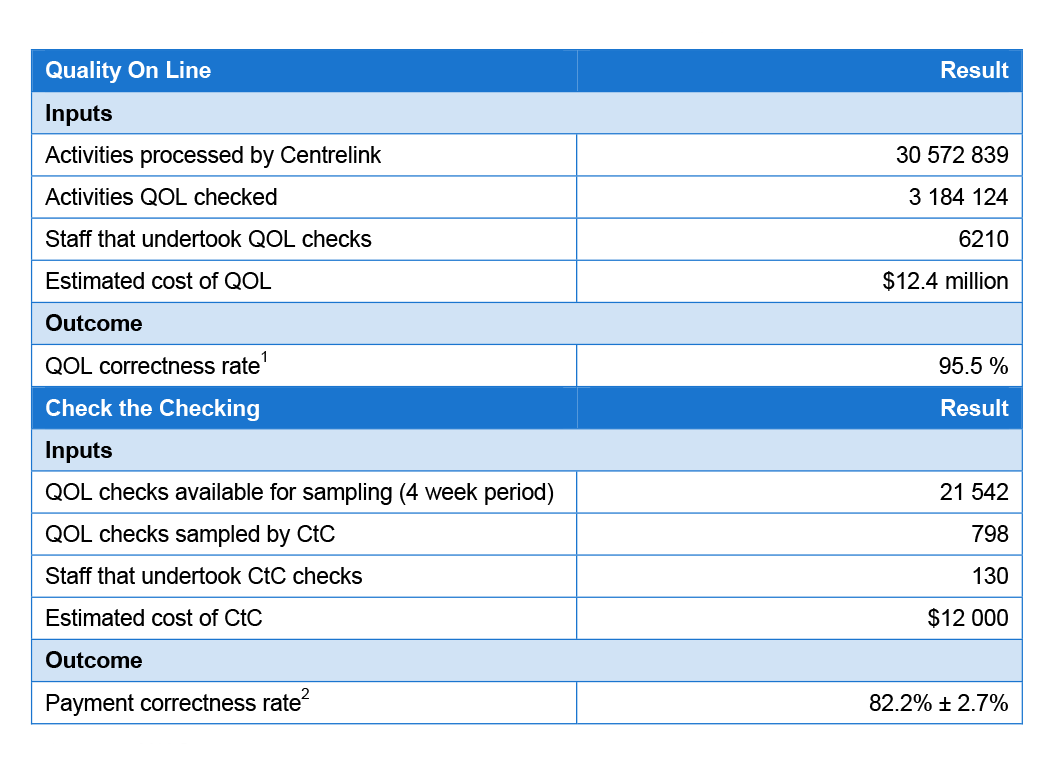

19. Table S.1 presents the QOL results for 2010–11 and the final round of CtC, which was conducted in 2010. The QOL and CtC processes are described and analysed in detail in Chapters 3 and 4 respectively of the audit report.

Table S.1: Quality On Line (2011-12) and Check the Checking (2010) results

Notes: (1) The QOL correctness rate shows the proportion of QOL checked activities that were released for payment following the QOL check.

(2) The CtC results indicate that there was a 95 per cent probability that the national level of payment correctness for QOL checked and released new claim activities was within 2.7 per cent of 82.2 per cent (between 79.5 and 84.9 per cent).

20. Table S 1 highlights the relative scale of the QOL process compared to the much smaller CtC process. In 2010–11, over 6000 Centrelink staff completed approximately three million QOL checks at an estimated cost of $12.4 million. By comparison, approximately 800 CtC checks were completed by 130 staff in 2010 at an estimated cost of $12 000.

21. QOL supports Centrelink in achieving payment correctness. However, QOL is an internal payment control and, unlike the RSS, which is an assurance measure, QOL results were not published in the agency’s recent annual reports (2006–07 to 2010–11). In Centrelink’s 2010–11 annual report, a new section on ‘Quality management’ was included that highlighted QOL as one of a large number of quality controls in place to support service delivery outcomes for customers and government.18

Future of Quality On Line

22. The ongoing implementation of Service Delivery Reform is leading to changes at all levels of Centrelink’s operations. Two areas of changed operation that are likely to affect QOL are:

- Customers’ use of online services. An increasing number of customers are using online services to perform some transactions: claiming a payment; reporting employment income; and updating or advising customer details. Centrelink has estimated that the customer self-service transaction model accounts for 25 per cent of transactions, compared to 75 per cent of transactions being performed by CSAs.19Customer self-service transactions are not currently subject to QOL.

- Staff use of digitisation.20

- The expansion of digitisation will mean that Centrelink can manage workloads nationally. For QOL, this means that virtual processing (sometimes referred to as remote processing) of QOL checks will be more widely available across the Centrelink network.21

23. Since 2000, both the QOL and CtC processes have been reviewed by Centrelink. Centrelink has considered how best to align QOL and CtC to meet current and future business needs in response to changes to organisational structure, information technology (IT) systems, and business processes. QOL is being reviewed again in 2011–12 (see Chapter 3) and CtC has been replaced with a new quality assessment and assurance process (see Chapter 4).

24. In the foreseeable future, Centrelink will continue to use QOL as the main quality control mechanism for payment correctness. Therefore, it is important that QOL operates effectively and contributes to supporting the integrity of payments administered by Centrelink.

25. As part of Service Delivery Reform, DHS may also integrate the currently independent quality frameworks that operate in Centrelink, the Child Support Agency and Medicare, which will also affect QOL.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

26. Previous ANAO performance audits, since 2000, have examined aspects of Centrelink’s payment control and quality assurance frameworks, such as the Random Sample Survey, and included findings about the operation of QOL. The ANAO has not previously undertaken an audit that focuses exclusively on the operation of QOL and its role in Centrelink’s payment control framework.

27. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Centrelink’s QOL control, which supports the integrity of payments administered by DHS on behalf of the Australian Government.

28. Centrelink’s performance was assessed against three high-level audit criteria:

- QOL is an effective quality control process for checking payment correctness;

- management information from QOL is monitored and reported to identify trends and inform changes to business processes that will lead to a reduction in administrative error; and

- CtC is an effective quality assurance program for QOL.

29. The audit scope did not include an examination of training for QOL and CtC as there was no indication of a systemic problem with training either when planning the audit or during the conduct of audit fieldwork.

Overall conclusion

30. Before Centrelink was integrated with DHS in 2011, it was the largest single agency in the Human Services portfolio. In 2010–11, Centrelink delivered services and administered $90.5 billion in payments to 7.1 million customers.22Administrative error caused by Centrelink staff, systems, or ambiguous rules can adversely affect customers’ payments, inconvenience customers, and lead to additional work and expense for Centrelink. Achieving payment correctness in Centrelink—paying the right person at the right rate, under the right government program, and on the right date23—supports the integrity of payments made to customers on behalf of the Australian Government and contributes to the efficiency and effectiveness of Centrelink’s operations.

31. A better practice model for achieving payment correctness would feature a quality control and related quality assurance process, with both elements contributing to minimising administrative error and the risk of payment error occurring. In 2000, Centrelink adopted Quality on Line (QOL) as a quality control and subsequently developed Check the Checking (CtC)24as the complementary quality assurance measure. Today, QOL remains as one of the key internal quality controls used by Centrelink to support payment correctness.

32. The QOL process is a preventative check that involves a QOL Checker reviewing a predetermined sample of a Customer Service Adviser’s (CSA) work activities.25 QOL checks for correctness focus on whether a CSA has accurately processed a customer’s claim for a social security benefit. In 2010–11, approximately 10 per cent (three million) of the 30.6 million activities processed by CSAs were QOL checked. The checks, undertaken by approximately 6000 Centrelink staff, cost an estimated $12.4 million. The QOL correctness rate, which shows the proportion of QOL checked activities that were released for payment following the QOL check, was 95.5 per cent.

33. QOL provides a limited level of assurance and is effective at the local level in Centrelink—in customer service centres and Smart Centres26 as a routine control process for identifying administrative errors, providing feedback to CSAs about their processing of activities, and identifying training needs for individual CSAs. Common administrative errors made by CSAs that could potentially affect customers receiving the right rate of payment relate to coding and verification errors for customers’ income and asset details, and errors with rent assistance payments.27 While QOL is effective at the local level, there remains scope to better utilise its potential through improvements to both its operation and the manner in which QOL results are used at the national level.

34. There is scope for Centrelink to improve the operation of QOL by reviewing the underlying risk-based sampling approach and refocusing QOL towards higher-risk activities and excluding or reducing the sampling of low-risk activities where administrative errors are less likely to occur. An analysis of the available 2010–11 QOL data indicated that lower QOL correctness rates were associated with the processing of new claim activities for customers, which suggests that Centrelink could also refine its sampling for QOL to target a greater volume of new claims and reduce the checking of non-new claims (existing customer claims).28

35. There is currently no control to provide assurance that administrative rework identified during QOL checking is being corrected by CSAs. Centrelink advised that, in the future, it anticipates addressing rework for QOL by a variety of means, including by: publishing recommended procedures to manage QOL feedback and rework; improving the reports available from QOL’s central database of results; and potentially, adding further controls to the QOL software tool used by QOL Checkers.

36. QOL checks apply to both new claim and non-new claim activities. As a quality assurance measure for QOL, CtC only provided a limited level of assurance that QOL was an effective means to control the risk of administrative error. This was due to CtC only reviewing QOL new claim activities, rather than both new claim and non-new claim activities.29 Even with the limitation on sampling (excluding non-new claim activities), the CtC results demonstrated that QOL was less than a fully reliable indicator of the level of administrative error. The 2010–11 QOL data showed a payment correctness rate of 95.5 per cent across all QOL checked activities. In contrast, the CtC results in 2009 and 2010 indicated a national outcome30in the range of 73.5 per cent to 84.9 per cent31 for the samples of QOL checked and released new claim activities. The difference between the CtC and QOL results lends support to Centrelink’s approach to QOL, which treats QOL as only one control available to Centrelink to reduce administrative error.

37. In Centrelink, the devolution of administrative arrangements for QOL to local supervisors and managers means that the daily operation and performance of QOL is less visible at the national level to strategic management committees. While Centrelink has established both IT system-based mechanisms and a procedural framework that provide an effective basis for the operation of QOL, national-level monitoring of the effectiveness of QOL is constrained and Centrelink has not developed performance indicators to measure and report on QOL’s effectiveness at the national level. In order to maximise the potential usefulness of QOL and its contribution to managing Centrelink’s administrative error rate, there would be benefit in Centrelink improving its reporting capability to support national-level monitoring of key measures of QOL’s performance. As part of improving its reporting capability, capturing a longer time series of data to support trend analysis32 and analysing the feedback comments from QOL Checkers to CSAs to identify training needs at the national level, would be beneficial. Access to better management information for QOL at the national level would enable Centrelink to focus on improving the performance of existing business processes with a view to reducing administrative error and maintaining, or improving, payment integrity outcomes to the benefit of customers.

38. The QOL process aligns with the ongoing focus in DHS on Service Delivery Reform and providing a better experience for customers of government services. Administrative errors can result in post-QOL rework by Centrelink to correct underpayments or initiate debt recovery action for overpayments to customers. Using QOL to improve the quality of CSAs’ original decision-making could lessen appeal fatigue for customers involved in seeking reviews of administrative decisions33 and decrease the amount of rework for Centrelink. In this context, Centrelink’s current review of QOL is a timely opportunity to determine if QOL is effectively and efficiently meeting business needs. Any major changes made to QOL, as an outcome of the review, would benefit from a post-implementation review to identify the lessons learned.

39. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving the effectiveness of QOL and maximising QOL’s contribution to Centrelink’s payment integrity performance by: examining the current approach to risk-based sampling rates for QOL; and ensuring that a quality assurance mechanism is maintained to underpin QOL.

Key findings

Governance, Policy and Guidelines (Chapter 2)

40. Centrelink’s governance arrangements for monitoring the operation of QOL at a national level could be improved, in particular for the National Quality Sub-Committee—the main governance committee for quality-related matters. While there was no routine QOL or CtC reporting against agreed key performance indicators, the Sub-Committee has endorsed significant changes to QOL and CtC. Monitoring QOL performance at a national level could be improved if routine reporting was introduced. This reporting could focus on agreed key performance indicators against which QOL or CtC equivalent results could be measured and, if necessary, trigger remedial action nationally.

41. Underpinning the day-to-day operation of QOL (and previously CtC) is a series of policies and guidance that, among other things, are designed to align with Centrelink’s approach to payment correctness and administrative priorities. By its nature, QOL is a risk mitigation strategy for payment correctness. However, the policies and guidance should be supported by a risk management plan that identifies the risks to the operation and performance of QOL and identifies risk mitigation treatments.

42. During the fieldwork stage of the audit, Centrelink developed a risk assessment for QOL, which indicated that Centrelink’s IT systems do not fully support the implementation of QOL’s operational guidance or the generation of national reports. A current review of QOL provides Centrelink with an opportunity to finalise a risk management plan for QOL, which addresses the risks that are specific to the operation of QOL.

Quality On Line (Chapter 3)

43. The software tool supporting QOL uses a risk-based approach of targeting QOL checking at activities and staff deemed to be of higher risk of making a processing error. However, currently there is no central oversight or regular review of the sampling regime, including the sampling rates. Further, Centrelink’s draft overarching risk assessment for QOL does not comprehensively identify the risks associated with processing each activity or establish a methodology for ranking the risks of processing different activities.

44. For QOL to be most effective, it is important that Centrelink establish and maintain the risk-based sampling rates. This should be premised on a systematic approach to assessing the risks of processing individual activities and include periodic reviews of the level of risk and rate of QOL sampling for each claim processing activity. The development of a risk management plan for QOL in the future could be used to inform the setting of risk-based sampling rates in QOL, which would improve the effectiveness of QOL and, potentially, produce a cost benefit for Centrelink.

45. The administrative arrangements in place to support the assessment of staff proficiency (level of accuracy in processing activities) and the annual certification of QOL Checkers are central to the effective functioning of QOL—for targeting activities for checking and the integrity of individual QOL checks. Centrelink currently devolves responsibility for administering those processes to local supervisors and managers. As a result, Centrelink has no performance indicators against which to support a national assessment of QOL’s effectiveness.

46. While Centrelink’s software for QOL provides a degree of functionality at the individual and office level that allows areas for improvement to be identified and targeted, QOL results are not regularly monitored and reported at a national level. Access to information about QOL’s performance would support national-level decision-making about the operation of business integrity controls in Centrelink. However, the operation of the QOL software provides little scope for national-level monitoring, including reporting basic metrics (the number of QOL Checkers and the average time taken to complete a check), or identifying areas for systemic improvement. Currently, Centrelink also has limited visibility over how much rework is being generated by QOL, whether this work is being completed, and both the ongoing cost of rework and full cost of QOL. Readily available access to such information would assist Centrelink to obtain assurance about the effective operation of QOL and the success or otherwise of modifications to the process.

47. The QOL process has been in place for more than 10 years and Centrelink will need to consider the role and effectiveness of QOL in the context of the Service Delivery Reform program. Greater use of digitisation for customers’ records has the potential to improve Centrelink’s capacity to manage QOL workloads and build expertise. A significant shift towards customers using self-service options (online and phone) has also placed transactions outside the current QOL process and could lead to the QOL process being transformed at some future point in time. In this regard, Centrelink’s 2011–12 review of QOL will inform the future development and effectiveness of the QOL payment control within Centrelink’s broader quality framework and business operating environment.

Check the Checking (Chapter 4)

48. Centrelink operated a form of CtC for approximately 11 years from 2000 to 2011 to monitor the quality of the QOL process. The CtC results provided a limited level of assurance to Centrelink that the QOL system worked effectively. CtC results were stable over time and demonstrated that QOL was less than fully reliable as an indicator of the level of administrative error occurring in work performed by CSAs processing activities for customers of Centrelink. An average payment correctness level of approximately 78.8 per cent for the final three rounds of CtC checks in 2009 and 2010 was consistent with an earlier series of checks.

49. Before 2011, the decreasing visibility and functionality of CtC—due to suspensions of CtC, reduced rounds of checking and loss of detail in reporting the results—combined with predictable results, eroded the value of CtC over time and contributed to Centrelink’s decision to replace CtC. A new quality assessment and assurance (QAA) program, introduced in August 2011, is developmental.34Centrelink intends that the new program will incorporate lessons learned from CtC about the skill level of checkers, results from previous CtC checking rounds, and the potential to improve database management for CtC. However, it is too early to assess the effectiveness of QAA as a replacement quality assurance process for QOL.

Summary of agency response

50. The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report and considers the implementation of its recommendations timely given the reforms currently being undertaken. The department has commenced work on analysing the opportunities to amalgamate Quality Frameworks, including investigation of quality control and assurance processes.

Footnotes

[1] The Hon Chris Bowen MP, Minister for Human Services, Address to the National Press Club, Service Delivery Reform: Designing a system that works for you, Canberra, 16 December 2009 [Internet]. Available from <http://www.chrisbowen.net/media-centre/speeches.do?newsId=2809> [accessed 28 October 2011]. In December 2009, the Human Services portfolio incorporated the Department of Human Services, Centrelink, Medicare Australia, the Child Support Agency, Australian Hearing and CRS Australia.

[2] ibid.

[3] Service Delivery Reform has three objectives: to make people’s dealings with government easier through better delivery and coordination of services; to achieve more effective service delivery outcomes for government; and to improve the efficiency of service delivery.

[4] In July 2011, the Human Services Legislation Amendment Act 2011 integrated the services of Medicare Australia and Centrelink into DHS. Australian Hearing remains under the Human Services portfolio, but is a statutory authority separate from the department.

[5] Commonwealth of Australia, Administrative Arrangements Order, 9 February 2012, p. 27.

[6] In this report, references to Centrelink’s activities prior to July 2011 are references to Centrelink as an agency. References to Centrelink’s activities after July 2011 are references to the activities of DHS, which delivers Centrelink services and payments.

[7] Department of Human Services, Centrelink Annual Report 2010–11, DHS, Canberra, 2011, p. 17.

[8] In this report, either ‘area’ or ‘zone’ will be used to refer to the arrangements in existence at the time.

[9] Centrelink, The Four Pillars of Payment Correctness, 2002.

[10] Administrative error includes error caused by Centrelink staff, systems or ambiguous rules. Customer error is an error or omission by the customer in providing information to Centrelink.

[11] ANAO Audit Report No.43 2005–06, Assuring Centrelink Payments—The Role of the Random Sample Survey Programme, p. 22.

[12] Further information about the RSS can be found in ANAO Audit Report No.43 2005–06, Assuring Centrelink Payments—The Role of the Random Sample Survey Programme.

[13] An ‘activity’ refers to any change made by a staff member to a customer’s record in Centrelink’s Income Security Integrated System (ISIS—an electronic customer database). For example, customers applying for a Centrelink benefit, or supplying information that leads to a reassessment of an existing entitlement or an update to personal details.

[14] ANAO Audit Report No.34 2000–01, Assessment of New Claims for the Age Pension by Centrelink,

p. 99.

[15] In 2010–11, new claim activities represented 18.5 per cent of the total QOL activities processed that year.

[16] Centrelink discontinued CtC in August 2011 during the fieldwork stage of this audit.

[17] In 2009 and 2010, CtC was to be repeated three times a year, allowing one month to complete the checks followed by three months between rounds.

[18] Department of Human Services, Centrelink Annual Report 2010–11, DHS, Canberra, 2011, p. 145.

[19] Fifty-three million customer self-service transactions were reported in 2010–11, including online (update and view) and interactive voice recognition. Department of Human Services, Centrelink Annual Report 2010–11, DHS, Canberra, 2011, p. 17. A key performance indicator for DHS in

2011–12 is ‘Increase in the proportion of transactions completed through electronic channels’. Department of Human Services, Portfolio Budget Statements 2011–12 Human Services Portfolio, DHS, Canberra, 2011, p. 38.

[20] Digitisation means that Centrelink customers’ paper documents can be scanned locally or centrally and a digital image of the original document attached to the customer’s electronic record.

[21] QOL checks were referred to as virtual QOL in the former call centres, which are now known as DHS Smart Centres and include national processing teams.

[22] Department of Human Services, Centrelink Annual Report 2010–11, DHS, Canberra, 2011, p. 17.

[23] Centrelink, The Four Pillars of Payment Correctness, 2002.

[24] Centrelink discontinued Check the Checking in August 2011 during the fieldwork stage of the audit. Centrelink is developing a new quality assessment and assurance program to support the QOL process (refer to Chapter 4). It is too early to assess if the new program will be able to measure the quality of QOL Checkers’ work and report on the effectiveness of QOL.

[25] The CSA’s minimum correctness rate for processing activities determines their QOL proficiency level and sample size, which ranges from two per cent (Proficient) to 100 per cent (Learner) of their work being sampled.

[26] Call centres and national processing teams are now known as DHS Smart Centres.

[27] Centrelink, Check the Checking Round 3 Analysis, October–November 2010, January 2011, p. 9.

[28] During 2010–11, more than 80 per cent of Centrelink’s QOL checks related to non-new claims, with less than 20 per cent of QOL checks relating to new claims. However, the QOL correctness rate relating to new claims was 91.2 per cent, or 5.2 per cent lower than the rate for non-new claims

(96.4 per cent).

[29] In 2010–11, new claim activities represented 18.5 per cent of the total QOL activities processed that year.

[30] The national outcome is the overall payment correctness for QOL checked and released new claim activities, for all benefits combined (refer to Chapter 4).

[31] The average payment correctness level for the final three rounds of CtC performed in 2009 and 2010 was 78.8 per cent. The payment correctness rate presented in Table S 1, and Note 2, is only for CtC results in 2010.

[32] Centrelink stores QOL results in a central (DB2) database for a rolling period of 14 months.

[33] ANAO Audit Report No.16 2010–11, Centrelink’s Role in the Process of Appeal to the Social Security Appeals Tribunal and to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, examined customer requested reviews or appeals of decisions made by Centrelink.

[34] QAA has a dual purpose—to assess the causes of administrative error in Centrelink and to provide assurance about the operation of QOL and other work processes used by CSAs to process customers’ claims for the payment of social security benefits.