Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Promoting Compliance with Superannuation Guarantee Obligations

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office's activities to promote employer compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Superannuation Guarantee (SG) Scheme was introduced in 1992 to reduce, over time, reliance on the age pension as a means of funding the retirement of individuals and to provide a higher standard of retirement living.1 The Scheme is one of the three pillars of Australia’s retirement income system2, and it is envisaged that the proportion of the population who receive part-rate, rather than the full, age pension will increase as a result of the system maturing.

2. Since 1 July 2014, the minimum SG contribution is 9.5 per cent of an employee’s ordinary time earnings.3 In 2014, some 846 000 employers were required to make SG payments on behalf of approximately 11.7 million employees to around 548 000 superannuation funds.4 Total superannuation contributions for the year ending December 2014 were $100.6 billion, of which employer contributions totalled $77 billion.5

3. The Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (the SG Act) sets out the administrative arrangements for the operation of the SG Scheme. The Commissioner of Taxation is responsible for the day to day administration of the SG Act, and the role of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is to ‘support employers to comply with their superannuation guarantee obligations and identify and deal with those who do not.’

Superannuation Guarantee Scheme operation

4. The SG Scheme operates largely without intervention from the ATO, with employers making SG contributions to the superannuation fund of the employee’s choice. Where employers do not pay adequate SG contributions to the employee’s nominated fund on time, they may be liable for a SG charge. The SG charge consists of: the amount of superannuation not contributed (the ’shortfall’); an interest component (currently 10 per cent a year); and an administrative fee of $20 per employee per quarter. The employer is required to lodge a SG charge statement with the ATO, calculate the amount of SG charge payable, and pay the SG charge by the due date for the relevant quarter. The ATO forwards the shortfall and interest component (10 per cent) to the employee’s superannuation fund.

5. An employee who believes that SG contributions have not been paid can lodge an enquiry with the ATO (an employee notification). The ATO aims to investigate all employee notifications and, where it considers appropriate, audits employers to verify that correct SG payments have been made. In addition to responding to employee notifications, the ATO initiates a range of compliance activities to encourage compliance and to detect and address employer non-compliance. Within the ATO, the Superannuation business line, which is part of the Compliance Group, administers aspects of the superannuation system, including the SG Scheme.6

6. The SG Scheme’s operation directly involves other stakeholders, particularly superannuation funds. Among these, industry funds7 hold almost 40 per cent of all member accounts and many have a responsibility to verify employers’ compliance with award requirements, which count towards SG obligations. These funds often have intervention strategies to pursue and collect contributions in arrears, and employ debt collection services.

Administrative complexity of the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme

7. Some features of the operation of the SG Scheme present practical challenges for employers, employees, and the ATO, including:

- calculating SG amounts is not always straightforward for employers and employees. Also, the ATO does not have access to all the information that would support an accurate estimate of the SG contributions that should be or have been paid by employers;

- the penalties when employers pay their employee SG contributions late (through the SG charge) have been described by the ATO as punitive and inequitable8;

- as employees have a choice of superannuation funds, employers may be required to make payments to multiple funds, incurring additional administrative costs; and

- while employers are required to indicate on payslips the amount of SG contributions accrued, this does not necessarily mean that this amount was actually paid to the superannuation fund. In addition, SG payments are generally made quarterly, but employees often receive a statement from their fund annually. Consequently, an employee may not detect the non-payment or under-payment of SG contributions until almost 12 months after the payment was due. These factors also increase the difficulty for the ATO to identify and investigate non-compliance in a timely manner.

8. These challenges can underpin employer non-compliance with their SG obligations. The ATO has analysed the main characteristics of non-compliance and considers it to be more prevalent among micro and small businesses.9 It may also form part of a broader picture of non-compliance, with employers also failing to withhold employee’s income tax, paying wages in cash or incorrectly treating employees as contractors.10 The industry sectors where these practices occur more frequently include construction, transport, accommodation and hospitality. The ATO considers that employer non-compliance with SG obligations is primarily driven by business difficulties affecting cash flow, resulting in employers using SG contributions to fund other business operating expenses. The ATO has also identified a level of disengagement with the SG Scheme among some employers, where SG is given a low priority.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s activities to promote employer compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations.

10. To form a conclusion against this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) adopted the following high-level criteria:

- administration and compliance activities are supported by effective management arrangements;

- compliance risks are identified through effective risk assessment processes and a comprehensive compliance strategy is in place;

- compliance activities, associated objections and debt collection arrangements are conducted effectively; and

- performance monitoring demonstrates the extent to which outcomes and objectives have been achieved.

Overall conclusion

11. The Superannuation Guarantee (SG) Scheme was designed to help Australians, particularly lower paid workers, enhance their incomes and improve their living standards in retirement. As the system matures, it is also expected to supplement or reduce reliance on the age pension.11 The age pension is the Commonwealth’s largest spending programme, with annual expenditure of $39.5 billion in 2014, growing at 3.7 per cent per year in real terms to 2023–24.12

12. For the SG Scheme to operate effectively, the ATO has an important role to play, supporting employers to comply with their SG obligations and dealing with those that do not. The ATO carried out a wide range of activities to promote compliance and help employees and employers to understand their SG rights and obligations. These activities include responding to over 18 000 employee notifications, and conducting 5000 to 6000 audits of employers at risk of non-compliance with their SG obligations every year between 2010–11 and 2013–14.13 As a result of these compliance activities, the ATO has raised on average $640 million each year in SG charge liabilities, collecting approximately half of this amount.

13. Overall, the ATO’s administration of the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme has been generally effective, particularly having regard to the scale of the Scheme and substantial flow of legislated revenue generated. Nevertheless, to better target its activities and more effectively promote employer compliance with SG obligations, the ATO should gain a greater understanding of the levels of non-compliance with SG obligations across industry sectors and types of employers. This is important given the potential impact of non-compliance on the retirement income of employees, and the role of the Scheme in reducing reliance on the age pension.

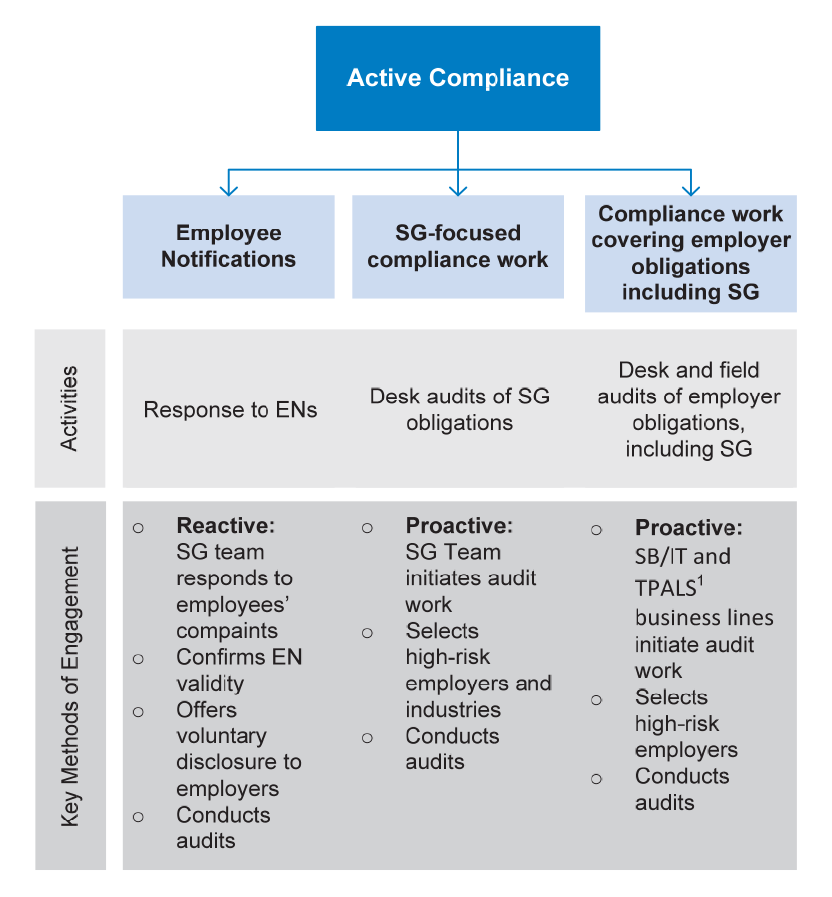

14. The ATO’s public assessment is that, ‘overall employers demonstrate high levels of voluntary compliance’.14 However this view, based largely on total employer contributions as a proportion of total salary and wages, does not adequately reflect the level of non-compliance in specific groups of employers and industry sectors. The ATO’s own internal risk assessment indicates that as many as 11 to 20 per cent of employers could be non-compliant with their SG obligations, and that non-compliance is ‘endemic15, especially in small businesses and industries where a large number of cash transactions and contracting arrangements occur.16 Importantly, this non-compliance primarily affects lower paid employees and those are most likely to rely on the age pension in later years. While the ATO has conducted an evaluation of the effectiveness of its SG compliance strategy at regular intervals (every year between 2010–11 and 2013–14), the most recent of these evaluations, completed in 2014, was not sufficiently robust to enable a reliable assessment of the ATO’s effectiveness in addressing the risks of non-compliance with SG obligations.

15. The ATO has established a number of forums to consult with superannuation industry stakeholders. As previously discussed, these stakeholders often play an active role in pursuing non-compliance. There is scope for the ATO to explore the more extensive use of compliance information retained by some of these stakeholders (such as the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman17), including the larger superannuation funds (provided these funds are willing to share their information18). A closer collaboration would offset some of the disadvantages of the SG Scheme operating largely without intervention from the ATO, and could improve the ATO’s ability to assess compliance risks and detect non-compliance earlier.

16. In encouraging compliance, the ATO has predominantly focused on communicating recent legislative changes19 affecting SG. Giving greater emphasis to explaining the role the ATO plays in dealing with non-compliance would improve community perceptions that the ATO is not active in addressing non-compliance with SG obligations. In addition, while a range of education resources are available to employees, employers and superannuation stakeholders, there would be merit in improving the useability of some of the electronic tools accessible from the ATO website.20

17. In dealing with non-compliance, the ATO has dedicated most of its Superannuation business line’s compliance resources in recent years to addressing the 18 000 employee notifications it receives on average annually. The ATO has regularly met and often exceeded its timeliness standards and has improved the way it informs employees of the progress of their notification. Audits are undertaken by both the Superannuation business line and the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers business line.21 These audits have been successful in identifying non-compliant employers and raising unpaid SG, with strike rates22 in excess of 70 per cent. Given this success rate, the commonalities in risk profiles, and to optimise compliance resources, there would be benefit in better aligning the SG compliance strategy with the compliance activities undertaken by the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers business line. Within this context, there is also scope to increase the cooperation with other relevant ATO business lines to include SG compliance as part of their audit activities.

18. The amount of SG charge collected by the ATO represented approximately half the amount it raised in liabilities (in 2013–14, $844 million in SG charge was raised, and $395 million was collected). At 30 June 2014, SG debt reached over $1 billion and has been growing at a rate of 12 per cent per annum since 2011–12. Two main factors affect SG charge collections: delayed compliance intervention and employer insolvencies. Since June 2012, the ATO has been able to issue Director Penalty Notices (DPNs), which make company directors personally liable for unpaid SG amounts. While the ATO described this measure as a powerful tool to enhance employer compliance, especially in cases of insolvencies, it issued notices to only 219 insolvent companies with a SG charge debt in 2013–14. Given the ATO was unable to advise the size of the relevant population (directors of insolvent companies) that should have received a DPN, it was not possible to evaluate the effectiveness of this new measure.

19. The ATO is implementing a number of initiatives to further strengthen the effectiveness of its SG compliance strategy, including the Tailoring the Employer Experience for Superannuation Guarantee project23 and a new debt collection strategy to recover debt earlier and more effectively24. To further support the ATO’s effort, the ANAO made four recommendations aimed at better promoting SG compliance. The recommendations relate to: better analysing non-compliance and further engaging with superannuation stakeholders; emphasising the ATO’s enforcement role; better coordinating compliance activities within the ATO; and evaluating the effectiveness of compliance activities.

Key findings by chapter

Assessing Overall Compliance Risk (Chapter 2)

20. As mentioned previously, the ATO stated in its 2013–14 Annual Report that, ‘overall, employers continue to demonstrate high levels of voluntary compliance with their superannuation guarantee obligations’.25 This assessment was largely based on two key measures: overall employer SG contributions exceeding the statutory percentage of salary and wages paid (9.5 per cent in 2013–14); and employee notifications received by the ATO being low as a proportion of all employees (less than 0.02 per cent in 2013–14).

21. The ATO’s assessment of the rate of SG contributions is subject to limitations, including that it:

- does not account for the fact that some employers contribute higher than legislated levels of SG and others pay less or no contributions;

- does not capture data relating to employees receiving no SG contributions at all, for instance because they are in a sham contracting arrangement; and

- is based on data from third-party sources (primarily, the Member Contribution Statement provided to the ATO by superannuation funds) and employer self-reporting (through the reportable employer superannuation contributions26 facility), which do not align sufficiently well to allow accurate matching.

22. In relation to the low proportion of employee notifications as an indicator of employer compliance with SG obligations, research commissioned by the ATO demonstrates that employees are reluctant to complain to the ATO about unpaid SG; and the measure does not account for the complaints to, and the compliance work conducted by, other superannuation stakeholders.

23. Further, the ATO’s public assessment of the risk of non-compliance with SG obligations is at odds with many external superannuation stakeholders’ views that employer non-compliance is likely to be widespread in small businesses and in businesses where a large number of cash transactions and contracting arrangements occur. These are also the industries where employment is the most transient, where salaries are more likely to be low, and the workforce young, employed on a part-time or casual basis, or from migrant backgrounds and with low levels of skills and literacy. The ATO’s public statement also contradicts its internal risk assessment that estimated that between 11 and 20 per cent of employers were not meeting their SG obligations, and that non-compliance is endemic.

24. Many superannuation industry external stakeholders (including industry superannuation funds, superannuation debt collection services and the Fair Work Ombudsman) have early visibility of possible non-compliance and conduct compliance activities. Developing a closer relationship with these stakeholders would enhance the ATO’s risk identification processes and allow the ATO to more promptly and effectively address non-compliance.27 There is also potential for the ATO to increase the use of external compliance information sources, in order to undertake a more complete analysis of non-compliance with SG obligations.

25. The ATO’s current work on estimating the ‘superannuation gap’28 should improve the ATO’s capacity to assess and identify non-compliance with SG obligations overall. However, there is scope for the ATO to revise its assessment in the groups of employers and industry sectors most at risk.

Promoting Voluntary Compliance (Chapter 3)

26. The ATO website is the main repository of publicly available information on taxation and superannuation matters, and includes general facts, technical rulings and law administration practice statements. Employers and employees can access the information about their obligations and entitlements through a fast and simple navigation of the website. As such, the website represents a valuable resource and also an important channel for disseminating other forms of communication, such as media campaigns.

27. The website also enables access to four online decision tools and calculators that are designed to assist employers and employees to determine and manage their SG obligations and entitlements. Two of these tools, the employer SG charge statement and calculator tool, and the employee SG calculator29, were relatively difficult and time consuming to use, and could act as a deterrent to both employers and employees in engaging with the ATO to ensure their SG rights and obligations are met.

28. Overall, the ATO’s education strategies and campaigns recognise the critical role played by employers and key stakeholders in the effective operation of the SG Scheme. Also, the strategies focusing on specific employee population groups are appropriately informed by market research and active compliance work. Most recent education messages have focussed on the impact of the SuperReform30 changes for employers, and on the increase in the rate of SG. While not specifically targeting SG compliance, these campaigns can indirectly contribute to raising awareness of SG obligations and entitlements among employers and employees.

29. Market research conducted by the ATO and the ANAO’s consultation with superannuation stakeholders have identified that while most employers now have a good understanding of their SG obligations, they:

- are not generally aware of the role of the ATO in relation to the operation of the SG system;

- do not view the ATO as the primary source of information on SG; and

- are not concerned about being penalised in the event of non-compliance.

30. There is scope to further strengthen, in future marketing and education initiatives, messages aimed at raising employer and employee awareness of the ATO’s role in addressing non-compliance with SG obligations.

Addressing Non-Compliance (Chapter 4)

31. Under the SG compliance strategy, active compliance work comprises two main tasks: responding to employee notifications (ENs); and selecting and conducting proactive audits (that is, audits based on information from sources other than ENs). When employers are identified as non-compliant with their SG obligations, the ATO raises and attempts to collect the SG charge.

Responding to employee notifications

32. Between 2010–11 and 2013–14, the ATO received, on average, over 18 000 ENs annually. Approximately half (46 per cent)31 the ENs finalised by the ATO during this period were verified as presenting a compliance issue and led to an SG charge being raised.

33. Of the 54 per cent of ENs finalised as ‘no further action’, around one in three were finalised due to employer insolvency, which meant that although employers were non-compliant and an SG amount was due, it was likely to remain unpaid. In one in four ENs, the employers had paid the SG contribution late or the ATO did not identify that they had an SG obligation.

34. Overall, the ATO has met and often exceeded its timeliness standards over the past several years, reaching a decision within four months for 70.7 per cent of ENs and within 12 months for 99.8 per cent of ENs. However, these standards could be more meaningful if they included, in addition to the time taken by the ATO to reach a decision, the time required for ENs to be finalised, that is for the notifier to know whether or not any potential unpaid SG has been recovered (this took more than 300 days for 30 per cent of ENs).

35. Given the large proportion of ENs finalised as ‘no further action’ the implementation of the 2015 ATO project Tailoring the Employer Experience for SG is timely and presents potential for improving the ATO’s efficiency in responding to ENs.32

Conducting proactive audits

36. On average each year between 2010–11 and 2013–14 the ATO has raised $176 million in SG liabilities, as a result of conducting:

- 660 audits focusing solely on compliance with SG obligations, carried out by the Superannuation business line; and

- 5000 audits, undertaken by the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers business line, of compliance with employer obligations more broadly, and including SG.33

37. These two types of audits presented distinct characteristics and results. In particular, there were fewer SG-only audits, which took longer to complete (34 per cent of the SG-only audits were completed within four months or less, compared with 60 per cent of the audits of employer obligations more broadly); and had a lower strike rate (for 2013–14, 62 per cent of the SG-only audits were successful in identifying non-compliance with SG obligations, compared with 88 per cent of employer obligations audits). However, the SG-focused audits raised a much higher amount of liability, on average, per audit (for 2013–14, over $116 000 compared with approximately $36 000 for employer obligations audits), and the total direct time spent on each case was considerably less (for 2013–14, 24 hours compared with 48 hours for employer obligations audits).

38. There is a strong correlation between non-compliance with SG obligations and non-compliance with employer obligations more broadly. In 2013–14, 88 per cent of employers selected by the ATO for an employer obligation audit were found to also be non-compliant with their SG obligations. The ATO has also identified that non-compliance is more prevalent in small and micro businesses, particularly those involved in cash transactions, sham contracting and phoenix activities.34 Given these similarities, there is scope for the Superannuation business line to more closely align its SG active compliance strategy with the active compliance activities conducted by the Small Business and Individual Taxpayer business line, with a view to increasing the scale of, and returns from, audits addressing SG risks. More broadly, greater collaboration with other relevant ATO business areas to include SG in their compliance work would help to ensure that SG compliance issues are addressed in a more effective and timely manner and across a wider range of employers.

Collecting and transferring the SG charge

39. Between 2010–11 and 2013–14, the ATO raised on average each year $640 million in SG charge liabilities. Around two-thirds of these liabilities ($431 million) were from employers voluntarily lodging an SG charge statement. The balance ($210 million) was the result of compliance work conducted by the ATO through responses to ENs and proactive audits. The ATO collected approximately half ($331 million) of the SG charge liabilities raised, and a significant proportion ($54 million or 15 per cent on average) of SG payments made to superannuation funds was returned to the ATO.35

40. The SG debt on hand reached $1.021 billion in 2013–14, with an average annual growth of 12 per cent between 2010–11 and 2013–14. The main factors affecting ATO’s ability to recover the SG charge were delayed compliance interventions and employers becoming insolvent (in 2013–14, around half of the debt on hand was due to insolvencies). As previously discussed, issuing DPNs more systematically and promptly after a suitable case is identified would increase the likelihood of recovering unpaid SG.

Quality Assurance, Review Process and Evaluation (Chapter 5)

41. In addition to routine quality checks by approving officers at key decision points, the ATO applied, until June 2014, a quality assurance framework that aimed to continuously improve and assure the consistency and correctness of administrative decisions made by staff (the Integrated Quality Framework—IQF).36 The IQF assessed 424 closed superannuation audits between 2010–11 and 2013–14, detecting a range of technical and staff capability issues and undertaking corrective actions that resulted in the improvement of most quality measures. Two measures continued to be below the quality benchmark in 2013–14, ‘transparency’ (including inadequate record keeping) and ‘integrity’ (including insufficient adherence to security procedures when using email and proof of identity checks).37 The ATO advised that these issues were present across all business lines and a continuing theme under the new quality framework.

42. The ATO’s review process allows employers to disagree with a decision made by the ATO in relation to their SG charge liabilities by asking for an amendment or making an objection to the ATO’s assessment.38 If they still disagree with the ATO’s review outcome, employers can lodge an appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, the Federal Court of Australia or the High Court of Australia.

43. Between 2010–11 and 2013–14, the ATO completed 5694 amendments and objections relating to SG charge (1400 on average each year). It has achieved its timeliness standard (completion within 56 days) in 89 per cent of cases (against a benchmark of 70 per cent). More than two in three (70 per cent) of these amendments and objections were allowed in part or in full. The main reason for this outcome was the provision of additional facts and evidence by the employer after the completion of a compliance case.

44. During the same period, 108 appeals were made to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (98 appeals), the Federal Court or the High Court (10 appeals). Of these, 46 appeals were settled and 44 withdrawn or dismissed. Fourteen were decided in part or in full against the employer, and four against the ATO.

45. Complaints are another form of feedback that employers and employees can use if they are dissatisfied with an ATO decision or administrative process. Between 1 January 2012 and 31 October 2014, the ATO received 553 complaints related to SG matters (less than one per cent of the 30 000 complaints the ATO received each year over this period). This relatively low number contrasts with Commonwealth Ombudsman’s information indicating that superannuation was the fourth most common theme of complaints received about the ATO between 2011–12 and 2013–14, representing some 10 per cent of ATO complaints. Most complaints made to the Ombudsman related to unpaid SG contributions and were typically made (as were complaints lodged directly with the ATO) by individuals concerned about delay, lack of information or uncertainty about the ATO’s progress towards collecting unpaid superannuation; and small business employers disagreeing with audit actions.

46. Since 2008, the ATO has used a compliance effectiveness methodology to measure the effectiveness of its compliance strategies in treating specific compliance risks. The ATO has applied this methodology to evaluate the effectiveness of the SG compliance strategy at regular intervals (every year between 2010–11 and 2013–14), with the last completed evaluation conducted in August 2014. However, the absence of reliable performance indicators and a clear conclusion reduced the usefulness of this evaluation to improve the SG compliance strategy and address compliance risks.

Summary of entity response

47. The proposed audit report was provided to the ATO. The ATO’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the formal response is provided at Appendix 1.

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our activities promoting compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations.

We are committed to fostering willing participation with superannuation guarantee through improved services as well as committed to dealing with non-compliance by striking the right balance between encouragement and enforcement according to individual circumstances

The review acknowledged work that the ATO is currently progressing to promote and improve compliance with superannuation guarantee that will complement the recommendations contained in the report.

The ATO agrees with the four recommendations contained in the report.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.49 |

To provide greater assurance of the level and nature of non-compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations, the ANAO recommends that the ATO:

ATO response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.29 |

To more effectively encourage employers to comply with their Superannuation Guarantee obligations, the ANAO recommends that the ATO increases the emphasis on the ATO’s role in enforcing compliance in its communication and marketing activities. ATO response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.40 |

To improve the effectiveness of the ATO’s Superannuation Guarantee compliance activities, the ANAO recommends that the Superannuation business line better aligns its Superannuation Guarantee compliance strategy with the compliance activities conducted by other relevant business lines. ATO response: Agreed. Continued on next page |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 5.37 |

To enable a reliable assessment of the effectiveness of compliance strategies to address the risks of non-compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations, the ANAO recommends that in future Compliance Effectiveness Methodology evaluations, the ATO:

ATO response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information on the Australian Taxation Office’s approach to promoting compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations. It also outlines the audit approach, including the objective, criteria, scope and methodology.

Introduction

1.1 Superannuation is a significant element of Australia’s financial system. It represents the largest source of long-term savings in Australia and the second most significant source of wealth for many Australians, after the family home.39 In December 2014, total superannuation assets were estimated at $1.93 trillion, and superannuation contributions for the year ending December 2014 were $100.6 billion, of which employer contributions totalled $77 billion.40

1.2 The superannuation industry has benefited substantially from the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) Scheme in 1992.41 The SG Scheme is a compulsory system of superannuation support, paid to superannuation funds by employers on behalf of their employees, and is one of the three pillars of Australia’s retirement income system.42 Under this system, it is expected that most people’s retirement income will be funded from a combination of superannuation and the age pension. As the system matures, it is envisaged that there would be an increase in the proportion of the population who receive part-rate, rather than the full, age pension.43 In 2014, the age pension was the largest Commonwealth spending program, with annual expenditure of $39.5 billion, growing at 3.7 per cent per year in real terms to 2023–24.44 The SG Scheme was introduced to reduce, over time, reliance on the age pension as a means of funding retirement for individuals and to provide a higher standard of retirement living.45

Operation of the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme

1.3 Under the SG Scheme, in excess of 800 000 employers are required to make SG payments on behalf of approximately 11.7 million employees to some 548 000 superannuation funds.46 The Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (the SG Act) sets out the administrative arrangements for the operation of the SG Scheme.

1.4 Since 1 July 2014, the minimum SG contribution is 9.5 per cent47 of the employee’s ordinary time earnings (OTE), up to a maximum contributions base of $49 430 a quarter (or $197 720 a year).48 For the purposes of calculating an employee’s SG contribution, OTE are the salary or wages paid to employees for their ordinary hours of work.49

1.5 Employers must make SG contributions for all eligible employees who earn $450 or more (before tax) in a month, whether they are full time, part time or casual, either permanent or temporary residents of Australia.50 A contractor paid wholly or principally for labour is considered an employee for superannuation purposes and entitled to SG contributions under the same rules as employees.

1.6 On 1 July 2005, amendments to superannuation legislation, commonly known as ‘Choice of Funds’, came into effect. The amendments required employers to allow eligible employees51 to choose the superannuation fund into which their SG contributions would be paid. Where an employee does not choose a fund, the employer must advise the employee in writing of the name of the employer-nominated super fund (the default fund). Employers must also keep records that show: that eligible employees have been offered a choice of superannuation fund; the amount of superannuation paid for each employee and how it was calculated; and how any reportable employer superannuation contributions were calculated.

1.7 Under tax and superannuation law, employers are not required to report to employees SG contributions made on their behalf. However, the Fair Work Act 2009 and the Fair Work Regulations 2009 require relevant employers to include in payslips the amount of superannuation contributions they are liable to make or have made, and contact details of the superannuation fund into which the contributions have been or will be made.

1.8 Where employers do not pay adequate SG obligations to the employee’s nominated fund on time, they may be liable for a SG charge. The SG charge consists of: the amount of superannuation not contributed (the ‘shortfall’); an interest component (currently 10 per cent a year); and an administrative fee of $20 per employee per quarter. The employer is required to lodge a SG charge statement with the ATO, calculate the amount of SG charge payable, and pay the SG charge by the due date for the relevant quarter. The ATO forwards the shortfall and interest components to the employee’s superannuation fund. Employer contributions to a complying superannuation fund are generally tax deductible, but the SG charge is not.

1.9 The ATO website encourages employees to: check their payslips and superannuation fund statements to ensure correct payments; and follow-up any unpaid superannuation contributions with their employer, superannuation fund, and the ATO. An employee who believes that SG contributions have not been paid can submit an ‘employee notification’ (EN) to the ATO (either by telephone, online or in writing). The ATO aims to investigate all ENs and, when it considers appropriate, audits employers to verify that correct SG payments have been made.

ATO role in administering the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme

1.10 The Commissioner of Taxation is responsible for the day to day administration of the SG Act. The ATO’s role in relation to compliance with SG obligations is outlined in the ATO’s Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS), and states:

The ATO administers the [Superannuation Guarantee] programme by supporting employers to comply with their superannuation guarantee obligations and identifying and dealing with those who do not.52

1.11 Relevant activities undertaken by the ATO include:

- educating employers and employees about their SG responsibilities;

- responding to ENs;

- monitoring employer compliance with SG obligations and investigating employers for possible breaches of the SG legislation;

- administering the SG penalty regime; and

- advising the Department of the Treasury (the Treasury) of changes required to superannuation law, including the SG Act.

1.12 The SG Scheme largely operates without intervention from the ATO, with employers making SG contributions to employees’ funds or via clearing houses.53 As presented in Figure 1.1, the ATO’s direct intervention is limited to those cases where:

- employees do not believe that they have received their full superannuation entitlements or been provided a choice of fund, and notify the ATO through lodging an EN;

- employers do not comply with their obligations and notify the ATO by lodging a SG charge statement; and

- the ATO, through its risk-based compliance work, detects and addresses an employer’s non-compliance.

Figure 1.1: ATO’s role in administering the SG Scheme

Source: ANAO analysis, based on ATO documents.

1.13 As the SG Scheme operates largely independently of the ATO, the Office only has partial visibility of the flow of money and information between employers, employees and superannuation funds, affecting its capacity to encourage compliance and address non-compliance with Scheme obligations.

Role of superannuation funds in promoting compliance

1.14 The SG Scheme’s operation is also characterised by the direct involvement in compliance activities of other stakeholders, particularly superannuation funds. Superannuation funds are broadly categorised by the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 into large funds, regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), and self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs), regulated by the ATO. While SMSFs have just three per cent of all members, they account for the vast majority of all superannuation funds (99.9 per cent).54 Within APRA-regulated funds, several types of funds exist, as outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Fund types regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, June 2013

|

Fund type |

Description |

Member accounts (‘000) |

|

Retail |

Retail funds are open to anyone and are usually run by banks or investment companies. The company that owns the fund aims to retain some profit. |

14 395 |

|

Industry |

The larger industry superannuation funds are open for anyone to join. Others are restricted to employees in a particular industry. They are ‘not for profit’ funds, in that all profits are returned to the fund to benefit members. |

11 524 |

|

Public sector |

Public sector funds were created for employees of federal and state government departments. Most are only open to government employees. Profits are returned to the fund to benefit members. |

3 337 |

|

Corporate |

A corporate fund is arranged by an employer, for its employees. Some larger corporate funds are ‘employer sponsored’, as the employer also operates the fund. Other corporate funds are operated by a large retail or industry super fund (especially for small and medium-sized employers). Funds run by the employer or an industry fund will return all profits to members. Retail companies that run corporate funds will retain some profits. |

512 |

Source: APRA, Annual Superannuation Bulletin, June 2013 (revised February 2014), p. 19, and ASIC, MoneySmart website, Types of super funds.

1.15 Industry funds, which hold almost 40 per cent of all member accounts, play a significant role in supporting employers’ compliance with SG obligations. They often have intervention strategies to pursue and collect superannuation contributions in arrears, and also employ debt collection services, such as the Industry Funds Credit Control.

Complexity of the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme

1.16 Some features of the law setting out the operation of the SG Scheme present practical challenges for employers, employees, and the ATO. As mentioned previously, SG amounts must be calculated on the basis of OTE. The ATO distinguishes over 30 different types of possible earnings, from base salary and wages (the most common) to overtime, shift loading and pay for sick leave taken.55 Differentiating OTE from other types of payments (and therefore calculating SG amounts correctly) is not always straightforward, for employers and employees. These factors make it difficult for the ATO to correctly estimate the amount of SG contributions that should be paid by employers.

1.17 Determining whether and how much SG contributions are payable can also be difficult in situations where the employment status of the worker is not straightforward. Employers generally do not have to pay SG contributions on behalf of their contractors (unless the contractor is paid wholly or principally for labour). Establishing whether a worker is an employee or a contractor for SG purposes can be difficult.56 Also, a number of employers may try to avoid their SG responsibilities (and other employer obligations) by treating workers as contractors when they really are employees—a practice sometimes referred to as ‘sham contracting’.

1.18 As with pay as you go (PAYG) withholding for income tax purposes, employers must make SG payments on behalf of their employees, with transfers to funds occurring at least quarterly. The ATO has identified that one of the main causes of late SG payments is cash flow problems, especially among small businesses.57 Employers who wish to be compliant, but pay their SG obligations late and lodge an SG charge statement, are subject to penalties that the ATO has described as punitive and inequitable.58 For example, the owner of a motel employing 25 to 30 people who had fully paid all superannuation, albeit with a delay of a few days or months each quarter, was found liable to pay almost $80 000 in interest accrued over four years and over $10 000 in administrative fees.59

1.19 As employees have a choice of superannuation funds, employers may be required to make payments to multiple funds, incurring additional administrative demands, especially when using manual processes such as paying by cheque. While small businesses are able to use the free services of the Small Business Superannuation Clearing House, administered by the ATO, the proportion of business who do so remains low60, and these multiple payments can be an administrative burden for many employers.

1.20 For employees, as previously mentioned, establishing the correct amount of SG payment that they are entitled to is difficult, unless their working arrangements are straightforward (in particular, no salary sacrifice, overtime or shift work). Further, while generally employers are required to indicate on payslips the amount of SG contributions accrued, this does not mean that the amount was actually paid to the superannuation fund.61 Additionally, as SG payments are made quarterly, but employees often receive a statement from their fund annually, they may not be able to detect non-payment or under-payment until almost 12 months after the payment was due.62 In other situations, employees do not complain to the ATO of unpaid superannuation until after they have left their employers, for fear of retribution.63 These factors contribute to the ATO’s difficulty in identifying and investigating non-compliance in a timely manner, and are problematic where an employer has become insolvent in the meantime.64

The Treasury’s and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s role in the operation of the SG Scheme

1.21 The Treasury has responsibility for superannuation and retirement savings policy, including the SG Scheme. The Treasury and the ATO have a commitment to work collaboratively to provide advice to government on law design and policy issues affecting the tax and superannuation systems. A protocol underpins this commitment, which outlines the:

- approach to policy and legislation design, development and implementation;

- costing process for new and updated policy proposals; and

- provision of advice by the ATO to Treasury when the ATO has identified that enacted law is not operating consistently with the policy intent of the law.65

1.22 APRA’s role is to develop and enforce a robust framework of legislation, prudential standards and guidance that promotes prudent behaviour by authorised deposit-taking institutions (such as banks), superannuation funds, general insurers, and life insurers and friendly societies. The ATO and APRA have longstanding formal arrangements to facilitate the exchange of superannuation related information.66

ATO administrative arrangements and resourcing

1.23 The Superannuation business line, which is part of the Compliance Group, administers aspects of the superannuation system, including the SG Scheme. As at July 2014, the Superannuation business line had a budget of $103.4 million and 917 full time equivalent (FTE) staff engaged in superannuation activities. Of these, approximately 360 FTE were allocated to SG activities, including 236 FTE to compliance activities. The total program expenses for the special appropriation for the SG Act have almost doubled from 2008–09 to 2014–15 (from $217 million to $468 million), and are expected to grow moderately across the forward years (to $510 million in 2017–18).

1.24 For governance and operating purposes, the Superannuation business line is divided into segments and further into product teams or functional units. Responsibility for administering the SG Scheme rests with the SG Product Management Team (SG Team). The SG Team is responsible for:

- managing SG across the ATO;

- identifying and managing SG risks, including developing strategies to mitigate those risks;

- recommending law and policy changes to the Treasury; and

- administering bilateral superannuation agreements, including the implementation of new agreements and processing certificates of coverage.

1.25 A feature of the administration of the SG Scheme is the number of areas within the ATO that have responsibility for some element of its administration. As a result, many tasks are undertaken in teams other than the SG Team, for example, most marketing activities are conducted at the Superannuation business line level.

Previous audits and reviews

1.26 ANAO Audit Report No.16 1999–2000, Superannuation Guarantee, examined the ATO’s administration of the SG Scheme. The Report concluded it was effective overall, and made eight recommendations.

1.27 In March 2010, the Inspector-General of Taxation published a report on his review of the ATO’s administration of the SG charge.67 While the report concluded that the SG Scheme worked well for most Australians, it found the employees most at risk (working in micro businesses, contracted and casual, and younger employees) were also the least empowered and those most reliant upon compulsory superannuation contributions for a higher standard of living in retirement, beyond the age pension. The review also noted the significant variance between SG charges raised and collected. The Inspector-General of Taxation made twelve recommendations to improve the early identification of any SG shortfall, the timely handling of employee notifications and the prompt collection of the outstanding SG charge. Of these recommendations, seven were directed in full to the ATO, three were directed in part to the ATO, and two were policy matters requiring government consideration. The ATO agreed with nine of the 10 recommendations directed to it fully or in part, and disagreed with one recommendation proposing to significantly expand SG audit activities.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective and criteria

1.28 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s activities to promote employer compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations.

1.29 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- administration and compliance activities are supported by effective management arrangements;

- compliance risks are identified through effective risk assessment processes and a comprehensive compliance strategy is in place;

- compliance activities, associated objections and debt collection arrangements are conducted effectively; and

- performance monitoring demonstrates the extent to which outcomes and objectives have been achieved.

Methodology

1.30 The ANAO reviewed relevant documentation, interviewed key staff at the ATO, and consulted industry and other stakeholder groups. The ANAO also undertook substantive testing and analysis of the ATO’s databases, systems and processes as they related to the management of SG compliance.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO audit standards at a cost of approximately $635 000.

Structure of the report

1.32 Table 1.2 outlines the structure of the report.

Table 1.2: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2 |

Assessing Overall Compliance Risk Examines the ATO’s approach to assessing the overall risk of non-compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations, which is integral to the development of the Superannuation Guarantee compliance strategy. |

|

3 |

Promoting Voluntary Compliance Examines the ATO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations. Also assesses the ATO’s contributions to improving Superannuation Guarantee legislation. |

|

4 |

Addressing Non-Compliance Examines the approach used by the ATO to identify and address non-compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations. Assesses how the ATO selects different categories of employers for active compliance activities. Also examines the two main aspects of its Superannuation Guarantee active compliance strategy: responding to employee notifications and conducting proactive audit work. |

|

5 |

Quality Assurance, Review Process and Evaluation Examines the ATO’s arrangements for continuous improvement, including how it: assures the quality of Superannuation Guarantee compliance cases; responds to objections, appeals and complaints; and evaluates the performance of Superannuation Guarantee compliance strategies and activities in mitigating compliance risks. |

2. Assessing Overall Compliance Risk

This chapter examines the ATO’s approach to assessing the overall risk of non-compliance with Superannuation Guarantee obligations, which is integral to the development of the Superannuation Guarantee compliance strategy.

Introduction

2.1 To fulfil its SG responsibilities, the ATO must understand the overall risk of non-compliance, those industries or market segments at highest risk and the main triggers of non-compliance. Understanding compliance risks is particularly important as it underpins the SG compliance strategy, and the extent and nature of the ATO’s compliance activities.

2.2 The ATO considers that overall, based on its risk analysis, the SG Scheme works well. This analysis focuses on the value of SG contributions as a proportion of total salary and wages, and on the number of employee notifications (ENs) in relation to the overall number of employees. However, some stakeholders have conducted research that challenges this view, as discussed later in this chapter.

2.3 The ANAO examined the appropriateness of the ATO’s assessment of the overall risk of non-compliance with SG obligations, in particular:

- the ATO’s assessment of compliance risk;

- external stakeholders’ assessment of compliance risk; and

- the ATO’s use of external information sources.

ATO assessment of Superannuation Guarantee compliance risk

2.4 The ATO uses an Enterprise Risk Management Framework to record, categorise and manage risks that ‘may compromise either [the ATO’s] outcome or community confidence in the fair and effective administration of Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems’.68 The Enterprise Risk Management Framework defines three categories of risks: enterprise risks, relating to a core or enabling business function or process; operational risks, which are a component or a part of an enterprise risk; and tactical risks, associated with localised events or activities such as transactions, incidents and cases.

2.5 Of the four enterprise risks identified for superannuation, one relates directly to SG, and of the 20 superannuation operational risks, two involve SG.69 Table 2.1 describes the three SG risks, and the ATO’s rating and mitigation status for each risk, as at June 2014.

Table 2.1: SG enterprise and operational risks, June 2014

|

Name |

Description |

Residual Rating |

Mitigation Status |

|

SG (enterprise) |

‘Our aim is to have employers engaged and complying with their SG obligations. This will contribute to the integrity of the retirement income system and build community confidence.’ |

Significant |

Green |

|

SG legislation complexity (operational) |

‘The complexity of SG legislation leads to lower levels of compliance as stakeholders may not understand or be aware of their obligations and entitlements.’ |

Moderate |

Green |

|

SG employer obligations (operational) |

‘Employers actively seeking to avoid their SG obligations and our failure to identify non-compliance due to lack of reporting data leads to reduced employer compliance and an undermining of community confidence.’ |

Low |

Green |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

2.6 The ATO assessed the mitigation status for these risks as green, which means there were no significant obstacles to the existing risk mitigation strategies working.

2.7 As indicated previously, the ATO uses two key measures to support this assessment: at the macro level, employer SG contributions exceed the statutory percentage of salary and wages; and employee notifications received by the ATO remain very low as a proportion of employee populations. In his 2013–14 Annual Report, the Commissioner states:

Overall, employers continue to demonstrate high levels of voluntary compliance with their superannuation guarantee obligations. Total employer contributions as a proportion of total salary and wages were above the base rate of nine per cent for SG contributions in the 2012–13 year. (…) Only a relatively small number of individuals notified us that their employers had not paid their SG entitlements.70

2.8 The view that the SG Scheme is operating successfully overall was reinforced in the ANAO’s discussions with ATO executives, and through conclusions drawn by the ATO from 2013 commissioned research:

Overall, research found employees’ lack of concern about and engagement with superannuation guarantee suggests the system is working well for most, so much so that minimal intervention is required.71

2.9 While considering that the SG Scheme works well overall, the ATO has analysed ENs to gain a better understanding of the profile of non-compliant employers (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Case study—characteristics of non-compliant employers

|

Most ENs received by the ATO relate to employers in either micro businesses (70 per cent) or small businesses (23 per cent). There is also a relatively high number of ENs lodged by employees from the following sectors:

Not meeting SG obligations often occurs together with non-compliance with other employer obligations, such as failure to withhold employee’s income tax (which may arise through paying wages in cash or incorrectly treating employees as contractors). Industries where these two practices are more prevalent are also sources of frequent non-compliance with SG obligations. These industries include construction, transport, accommodation and food. According to the ATO, employer non-compliance with SG obligations is driven mainly by cash flow issues, resulting in employers using SG funds as business operating expenses. However, there will also be a level of disengagement with the SG Scheme among some employers, where SG is given a low priority. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

Estimating Superannuation Guarantee contributions as a proportion of salary and wages

2.10 One of the two measures used by the ATO to assess the risk of non-compliance with SG obligations is the overall rate of SG contributions. In addition to providing an indication of the level of employer compliance with SG obligations, this measure is used for accountability purposes: the ‘adjusted employer superannuation contributions as a proportion of adjusted salary and wages’ is one of three key performance indicators relating directly to superannuation in the ATO’s Portfolio Budget Statements in 2013–14.72

2.11 Calculating this measure is not straightforward. The information available to the ATO from employers, employees and funds has historically been reported at an aggregated level, which means that it does not allow for an exact reconciliation of amounts paid at the individual level.

2.12 In 2010, the Inspector-General of Taxation recommended73 that the ATO develop a more sophisticated analysis of the level of non-compliance with SG obligations and its impact on employees. Concurrently, the Government introduced a new reporting measure that required employers to include, from 2009–10, ‘reportable employer superannuation contributions’ (RESC)74 in employee payment summaries, which enabled the ATO to separate salary sacrifice amounts from SG amounts more accurately. Using RESC and the member contributions statements provided annually by superannuation funds, the ATO’s Revenue Analysis Branch (RAB)75 developed and implemented a new methodology to calculate the rate of SG contributions. On the basis of this new methodology, the Commissioner of Taxation has stated, consistently since 2011–12 (including in the 2013–14 Annual Report76) that the level of employer contributions was above the statutory SG rate. As at June 2013, the ATO estimated the level of SG contributions to be at 9.5 per cent against a legal requirement of nine per cent.

2.13 While this methodology provides some improvement over previous estimations, RAB has identified that it has a number of significant shortcomings, including:

- the high-level estimation masks the fact that at a disaggregated level, significant disparities may exist between industries (or within industries and between business sizes). RAB warns that ‘as some employers pay more than the minimum SG, this could cancel out employers who do not pay’;

- employees who do not receive any SG contributions at all (either because they are in a sham contracting arrangement, or their employer is non-compliant with their SG obligations or involved in the cash economy) are not captured by RAB’s calculations;

- employers do not report to the ATO on SG contributions made, only on RESC made on behalf of employees. To estimate SG amounts RAB must rely on a third-party data source, the Member Contribution Statements, which poses challenges for identity matching and consistency of reporting; and

- the reliability of ATO’s estimation of the level of SG contributions depends on employers accurately calculating SG amounts. The complexities involved in calculating SG amounts when an employee salary sacrifices could lead the ATO to overstate or understate the level of SG contributions.

2.14 The ATO could reconsider the confidence afforded to the current estimate, when reporting against their PBS key performance indicator, and in concluding that overall, employers are highly compliant with their SG obligations. This view of SG compliance is in contrast to the assessment of a range of external superannuation stakeholders, as discussed in the subsequent sections of this chapter. It also contrasts with internal ATO documents evaluating the SG risk, which state that non-compliance is ‘an endemic part of the superannuation system’77; and a ‘probable estimate of employers not meeting their SG obligations is between 11 and 20 per cent’.78 Further the ATO’s indicator of SG outstanding debt (related to ATO compliance outcomes) is showing a persistent increase: from under $500 million in July 2008 to over $1 billion at June 2014.79

Employee notifications as a proportion of population of employees

2.15 The number of ENs in proportion to the overall number of employees is the other main measure used by the ATO to assess the risk of non-compliance with SG obligations. According to the ATO, the fact that only a small minority of employees (less than 0.2 per cent in 2013–14, or approximately 20 000 individuals) notify the ATO of a potential breach with SG obligations, is another indicator that, for the most part, the SG Scheme is working well.

2.16 However, there are shortcomings in using this approach as it assumes that employees are in a position to readily identify unpaid superannuation and willing to report it to the ATO. Based on research commissioned by the ATO in 201380, there is evidence that employees, in general and more so among those industries most at risk, are not receiving their SG entitlements. The research reported that the causes of this non-compliance, included that employees:

- may be unaware of their entitlement to SG, are not interested in superannuation or do not know how to check that their SG has been paid (while nine in 10 employees surveyed considered it important or extremely important that employers pay SG, one in two did not know what to do and where to go if they had questions about the SG Scheme);

- do not know that the ATO is responsible for ensuring that employers are making SG contributions (this was the case for four in 10 employees surveyed);

- choose not to complain—among the minority of employees who had wanted to make a complaint about SG payments, just over half said they would do nothing about it, citing fear of losing their job or angering their employer.81 ATO and ANAO analysis of ENs also reveals that approximately 70 per cent of the notifications are received only after the employee has left the company (Chapter 4 Table 4.2); and

- may be discouraged by the complexity of lodging an online complaint (EN) with the ATO.

2.17 A number of stakeholders also address employer non-compliance with superannuation obligations, which means that a significant number of complaints never reach the ATO. Most industry superannuation funds have processes to pursue arrears in award superannuation payments with employers.82 For instance, one industry fund collected over $53 million in arrears in 2013–14, and the Industry Funds Credit Control (IFCC) website states that ‘during the 2011–12 financial year, IFCC collected more than $100 million of outstanding member entitlements’.83

2.18 Consequently, the number of ENs received is not a reliable indicator of the level of non-compliance. Given the diverse and sometimes cumulative barriers to lodging a complaint with the ATO, the ENs received could represent a fraction of the potential complaints.84 For this indicator to be more reliable, it is important that the ATO measures the impacts of these barriers on complaints lodgement, and also takes into account the complaints received and activities conducted by other stakeholders involved in award superannuation compliance work.

Measuring the ‘superannuation guarantee gap’

2.19 The tax gap is defined by the ATO as:

… the difference between the actual tax liability reported to us, or that we raise, and the tax liability that should be reported. That is to say, tax that would be reported assuming that all businesses and individuals fully complied with their tax-reporting obligations.85

2.20 The ATO has reported on the tax gap for the goods and services tax for a number of years and in 2014 commenced a project to measure the gap for other taxes, and more broadly for the Australian tax system.86 In a similar way, assessing the magnitude of, and trends in, the ‘SG gap’ would assist the ATO to understand the level of compliance with SG obligations, and more accurately assess the risk of non-compliance. Until 2014, the ATO had not undertaken any work in this direction. However, the ATO has advised that it commenced, during the course of this audit, work to estimate the ‘SG gap’, as part of the wider internal project to measure the ‘tax gap’.

External stakeholders’ assessment of compliance risk

2.21 In its 2010 report on the ATO’s administration of the SG charge, the Inspector-General of Taxation stated that he was ‘not convinced that the ATO’s macro picture [was] representative of the true level of non-compliance’.87 Estimates submitted to the Inspector-General of Taxation in a joint submission88 suggested that more than 500 000 employees were not receiving their full superannuation entitlements.

2.22 Through the consultation process conducted by the ANAO for this audit89, a range of stakeholders from the superannuation industry advised that the extent of non-payment or under-payment of superannuation contributions in specific employment sectors could be significant. According to Industry Super Australia, a research and advocacy body for industry superannuation funds, ‘SG compliance in certain industries is well below acceptable levels’.90 The IFCC, which collects outstanding super contributions and entitlements for the members of seven industry superannuation funds91, estimated the level of non-compliance among employers in general at between 12 and 17 per cent.92

2.23 A research paper commissioned by Cbus, an industry superannuation fund with more than 722 000 members (from the building, construction and allied industries and general public members), estimated that non-compliance with SG payments was equivalent to $2.5 billion in 2012 alone, with approximately 650 000 employees missing out on some or all of their superannuation contributions each year.93 The Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) considers the construction industry to be the worst offender in SG non-compliance, with missing contributions totalling $300 million to $450 million each year as a result of sham contracting, and $105 million to $350 million a year as a result of phoenix activity.94

2.24 ASIC statistics on unpaid employee entitlements by companies in external administration offer an additional insight on potential levels of unpaid SG entitlements. They show that in 2012–13, ‘at the very least $83 million in SG contributions were not paid by companies in external administration’.95

2.25 Stakeholders’ consistent feedback was that employer non-compliance was likely to be widespread in small businesses and in businesses where a large number of cash transactions and contracting arrangements occur. These are often the industries where employment is the most transient, salaries are more likely to be low, and the workforce young, employed on a part-time or casual basis, or from migrant backgrounds and with low levels of skills and literacy.96 Further, for some individuals, the impact of unpaid superannuation can be immediate; when SG payments are not made, the income protection insurance attached to some superannuation policies may also lapse, leaving the worker or their family exposed in case of injury or death. Table 2.3 presents an illustration of SG non-compliance in the clothing, restaurant and cleaning industries, as reported by some of the stakeholders consulted by the ANAO.

Table 2.3: Case study—unpaid superannuation in the clothing, hospitality and cleaning industries

|

Example 1 A Melbourne-based clothing company manufacturing women’s fashion garments entered into administration. The company had around 12 employees, mostly women from migrant backgrounds with limited English and computer literacy skills. The minimum weekly award rate payable was $685 before tax (for full-time employment). Around half of these employees had salary sacrificed additional superannuation contributions; however, the company had never made any award superannuation contributions or remitted any salary sacrificed amounts. One employee with more than 10 years employment, retired at age 65 (before the company entered into administration) with no superannuation. Shortly after the company entered into administration, the owners commenced trading under a new company name from the same premises. Most of the employees were re-employed by the new company. Example 2 Chris was working as a head-chef at a restaurant in Adelaide when he noticed some discrepancies in his pay, and that his superannuation was not being paid. He approached his employer, and was told the superannuation payments were correct, even though Chris’ superannuation fund statements showed otherwise. Chris was later made redundant. His employer had not paid him any superannuation for several years, and he was owed over $9000. Example 3 Most workers in the office and commercial cleaning industry are migrants on temporary visas, including international students. Ahmed is a cleaner working in a suburban shopping centre. Before commencing employment, his employer asked him to complete an application for an Australian Business Number with the intent of treating him as a contractor. While working, he wears a company uniform, works to a roster and is required to follow management directions. He receives no leave or other entitlements such as superannuation and the company does not withhold and remit income tax to the ATO on Ahmed’s behalf. Ahmed has never worked under an Australian Business Number before and does not understand that he is liable for his own income tax payments. |

Source: ANAO analysis of stakeholder submissions.

ATO use of external information sources

2.26 The ATO supports its assessment of superannuation compliance risk using a number of external information sources, including: data matching; third-party referrals; and consultative forums and other forms of engagement with external stakeholders.

Data matching

2.27 Data matching uses information from a variety of sources that are compiled electronically to support a range of education and active compliance activities. The ATO is authorised by the Taxation Administration Act 195397 to collect information from superannuation funds, through the annual Member Contribution Statements report. This information includes the superannuation fund and member tax file numbers, other member details, and the contributions made to members’ superannuation accounts. Before July 2013, Member Contribution Statements only reported on members for whom contributions had been received that year. From 1 July 2013, the statements report on all members.98

2.28 One factor that limits the completeness of this reporting, and the ATO’s ability to gain a comprehensive view of an employee’s SG contributions, is that employer details are not compulsory on the Member Contribution Statements. As a consequence, in a large number of cases the ATO can extract the financial value of employer contributions but cannot link this amount to particular employers.

Third-party referrals

2.29 Third-party referrals are tip-offs about individual employers that may not have complied with their SG obligations. These referrals are received from members of the public, unions and other superannuation stakeholders (including the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman) and ATO officers99, and have been collected by the ATO since November 2007.

2.30 Since 2010–11, the ATO has received an average of 220 referrals each year (Table 2.4). The main contributors to third-party referrals are ATO officers (44 per cent); members of the public (25 per cent); and superannuation funds (24 per cent).

Table 2.4: Third-party referrals received, 2010–11 to 2013–14

|

Information Sources |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

Total |

|||||

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

|

ATO officers |

59 |

29 |

71 |

37 |

85 |

40 |

169 |

63 |

384 |

44 |

|

Members of the public |

60 |

29 |

71 |

37 |

35 |

16 |

58 |

22 |

224 |

25 |

|

Superannuation funds |

78 |

38 |

39 |

20 |

67 |

31 |

31 |

12 |

215 |

24 |

|

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

16 |

7 |

5 |

2 |

26 |

3 |

|

Other, including trade unions and tax agents |

6 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

11 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

30 |

3 |

|

Total2 |

206 |

100 |

192 |

100 |

214 |

100 |

267 |

100 |

879 |

100 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

Note 1: The ATO advised that the 26 referrals from the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman included in this table are sourced from press releases issued by that Office. These referrals are in addition to the lists provided by the Fair Work Ombudsman since 2012 (see paragraph 2.33).

Note 2: Percentage totals may not add to 100 due to rounding.

2.31 Over the four-year period, unions contributed only three of all referrals received, and while superannuation funds lodged almost one quarter of all referrals, the number overall is small (54 a year on average). Promoting third-party referrals was a recommendation of a 2011 joint ATO and Industry Funds Forum project.100 In response, the ATO developed an information sheet in March 2012 and promoted the third-party referral process to a number of superannuation entities in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Despite this, stakeholders consulted by the ANAO were not always aware of the third-party referral process.

2.32 To assist in discharging its functions and powers under the SG Act, the ATO has entered into agreements to exchange protected information relevant to SG with two Australian Government entities101: the Department of Human Services102; and the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the FWO).103 The Department of Human Services provides the ATO with statistical reports containing personal information on employers and employees as part of the department’s administration of the Small Business Superannuation Clearing House. However, the ATO indicated that using this information for SG compliance purposes is not a priority because the client base, having taken the step to register with the Clearing House to pay their SG contributions, is at lower risk of non-compliance.

2.33 The FWO, under an information sharing agreement signed in 2012, provides the ATO with personal information about entities and individuals suspected of engaging in fraudulent phoenix activities, and employers audited by the FWO that appear to have not met their SG obligations. Since entering into the agreement, the FWO has provided the ATO’s SG Team with two lists of employers that may not have met their SG obligations—in March 2013 and March 2014, totalling 812 employer records.

2.34 The ATO has applied different treatments to referrals received from the FWO and to the other third party referrals presented in Table 2.4. Third-party referrals are subject to individual assessment and, for the period 2010–11 to 2013–14, 55 per cent of these referrals were escalated to audits. In contrast, the FWO’s lists are assessed collectively, using a risk assessment and case selection approach aimed at selecting a small number of the highest risk cases for audit (see Chapter 4, paragraph 4.27). Consequently, of the 812 records provided by the FWO since March 2013, only 21 (three per cent) were escalated to audit.

2.35 The ATO has limited resources to conduct active compliance work, in particular audits, and only escalates those cases it considers to be the highest risk. Nevertheless, the employers referred by the FWO represent a readily identified source of likely non-compliance. The ATO could more thoroughly assess the FWO records, and if not selecting these cases for audit, could consider a ‘lighter touch’ approach such as sending a letter to the employers identified by the FWO indicating that the ATO has received information on their potential non-compliance, and requesting them to check their records and address any discrepancies.

Consultative forums and other forms of stakeholder engagement

2.36 The ATO engages and communicates with stakeholders on SG matters via joint projects, public interventions (speeches, media communication) by senior ATO officials, and five key consultative forums on superannuation matters. From time to time, the ATO may also establish special purpose groups to consult on specific matters, or partner with a superannuation industry entity for specific projects. One such partnership was undertaken in 2011 with the Industry Funds Forum.

2.37 The ATO’s consultative arrangements for superannuation are a mix of strategic, stakeholder management and information sharing forums, and provide the ATO with an opportunity to engage with stakeholders on major policy and administrative issues affecting the superannuation system. Although the ATO determines the membership of all forums, there is representation from the range of superannuation industry entities. Individuals and entities can also register their interest in participating in some stakeholder forums through the ATO consultation hub.104