Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through its Australian Passport Office

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- During the conduct of Auditor-General Report No. 13 2023–24 Efficiency of the Australian Passport Office, the ANAO observed procurement practices by the Australian Passport Office (APO) within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) that merited further examination.

- This audit provides assurance to the Parliament of the effectiveness and ethics of DFAT’s Australian Passport Office procurement activity in the context of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Key facts

- Between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023, the APO managed 331 contracts totalling $1.58 billion.

- In this period, 243 new contracts totalling $476.5 million were entered into, in addition to existing contracts.

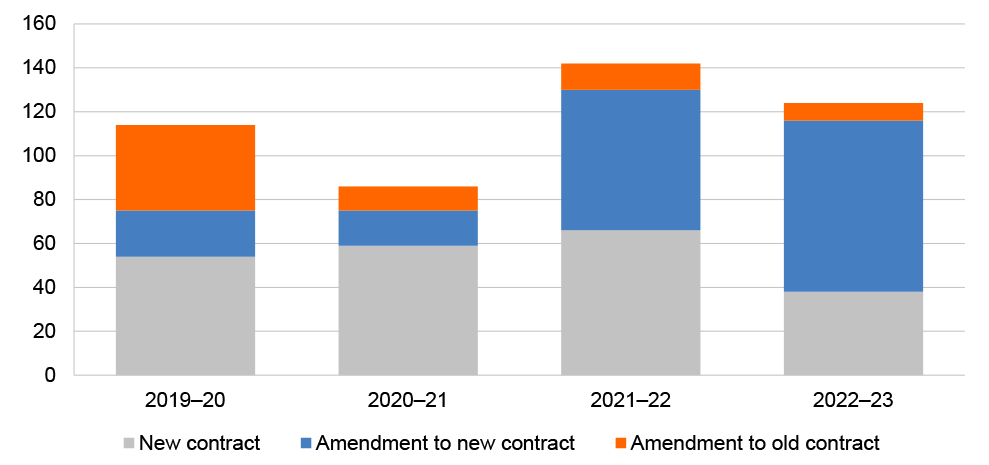

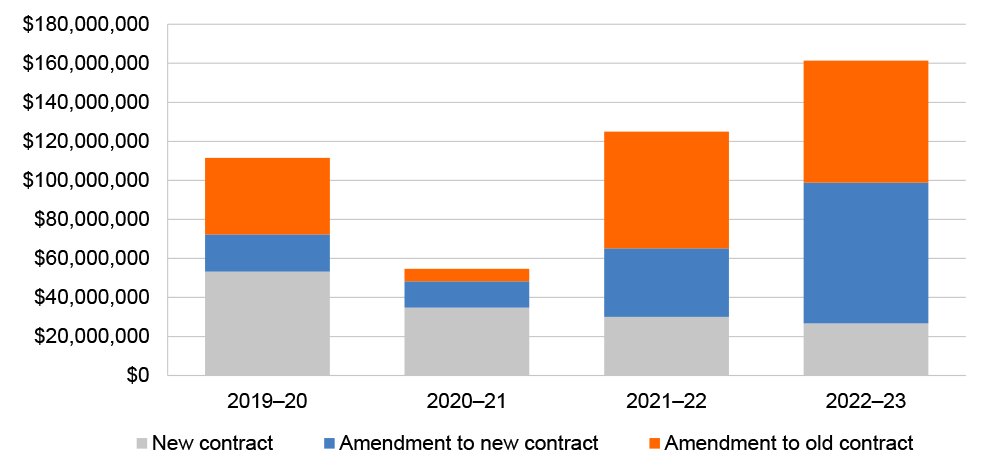

- In 2022–23, contract amendments represented 69 per cent by number, or 83 per cent by value.

What did we find?

- The procurements DFAT conducted through its Australian Passport Office did not comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and DFAT’s procurement policies, and did not demonstrate value for money.

- Open and competitive processes were not employed.

- Procurement decision-making was not sufficiently accountable and was not transparent. Procurement practices fell short of ethical standards.

What did we recommend?

- There were seven recommendations to DFAT. These focussed on: improving planning; obtaining value for money through open, transparent and effective competition; strengthening the department’s oversight and controls; and ensuring action is taken in response to ethical issues.

- The department agreed to all seven recommendations.

Nil

contracts entered into let via an approach to the open market.

29%

of 73 contracts examined were let via a genuinely competitive approach to market.

53%

of 231 approval records examined referred to value for money, although did not always demonstrate it had been achieved.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for issuing passports to Australian citizens in accordance with the Australian Passports Act 2005, with delivery of passport services in Australia and overseas being one of DFAT’s three key outcomes. In July 2006, DFAT established the Australian Passport Office as a separate division to provide passport services. The Australian Passport Office has offices in each Australian capital city and it collaborates with Australian diplomatic missions and consulates to provide passport services to Australians located overseas.

2. DFAT is also the entity responsible for Australia’s international trade agreements. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) incorporate the requirements of Australia’s international trade obligations and government policy on procurement into a set of rules. As a legislative instrument, the CPRs have the force of law.1 Officials from non-corporate Commonwealth entities such as DFAT must comply with the CPRs when performing duties related to procurement. Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The issuing of passports to Australian citizens is an important function of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, undertaken by its Australian Passport Office. Between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023, the Australian Passport Office managed 331 contracts totalling $1.58 billion.

4. During the conduct of an earlier audit, Auditor-General Report No. 13 2023–24 Efficiency of the Australian Passport Office, the ANAO observed a number of practices in respect of the conduct of procurement by DFAT through its Australian Passport Office that merited further examination. The Auditor-General decided to commence a separate audit of whether the procurements DFAT conducts through its Australian Passport Office comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and demonstrate the achievement of value for money.

5. The audit provides assurance to the Parliament of the effectiveness of the department’s procurement activities in achieving value for money, and the ethics of the department’s procurement processes, noting that procurement is an area of continuing focus by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.2

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to examine whether the procurements that DFAT conducts through its Australian Passport Office are complying with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have open and competitive procurement processes been employed?

- Has decision-making been accountable and transparent?

8. The audit focussed on procurement activities by the Australian Passport Office relating to contracts and contract variations that had a start date of between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023.

Conclusion

9. The procurements that DFAT conducted through its Australian Passport Office did not comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and DFAT’s procurement policies, and did not demonstrate it had achieved value for money.

10. DFAT did not employ open and competitive processes in the conduct of Australian Passport Office procurement. There were no procurements conducted between July 2019 and December 2023 by way of an open approach to the market. Of the 73 procurements examined in detail by the ANAO, 29 per cent involved competition where the department had not identified a preferred supplier prior to inviting quotes.

11. Procurement decision-making was not sufficiently accountable and was not transparent. Procurement practices have fallen short of ethical standards, with DFAT initiating inquiries of the conduct of at least 18 individuals, both employees and contractors, in relation to Australian Passport Office procurement activities examined by the ANAO.

Supporting findings

Open and competitive procurement

12. DFAT did not appropriately plan the procurement activities for its Australian Passport Office. There was no overarching procurement strategy. The department engaged a contractor to develop a multi-year procurement strategy that was never completed. Overall, only 15 per cent of the 62 approaches to market examined by the ANAO met the minimum requirements at planning stage. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.20)

13. None of the 243 contracts totalling $476.5 million the APO entered between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023 was let via an approach to the open market.

14. DFAT’s AusTender reporting indicates the APO procures by open tender from a panel arrangement 71 per cent of the time. The ANAO examined 53 contracts DFAT had reported this way and identified that for 15 contracts (28 per cent) the APO had deviated from the panel arrangement to the extent that the approach constituted a limited tender. The ANAO also examined 12 contracts valued over the $80,000 threshold reported by DFAT as let by limited tender. The approach taken for six of these contracts (50 per cent) did not demonstrably satisfy the limited tender condition or exemption from open tender that had been reported by DFAT. The department’s approach is inconsistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules which, in turn, reflect the requirements of the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (DFAT is the Australian Government entity responsible for Australia’s international trade agreements). (See paragraphs 2.22 to 2.50)

15. A competitive approach was used to establish only 29 per cent of the 73 contracts tested by number or 25 per cent by value. This involved the APO inviting more than one supplier to quote in a process that did not have a pre-determined outcome. On 19 occasions the procurement approach was not genuine as the purported competitive process did not, in fact, involve competition. (See paragraphs 2.51 to 2.70)

16. For 14 per cent of contracts tested, evaluation criteria were included in request documentation with those same criteria used to assess submissions. (See paragraphs 2.72 to 2.77)

17. There was not a documented approval to approach the market for 36 per cent of the 73 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO. Advice provided to approvers on the outcomes of approaches to market in most cases did not demonstrate how value for money was considered to have been achieved. Three-quarters of the time the approval was requested by an embedded contractor, often populating a template as an administrative function and sometimes at the direction of the approver telling them what to recommend.

18. One quarter of the time, approval was given within a week of the expected contract start date. A 2022–23 practice of approving commitments on the understanding that the Department of Finance would later agree to additional funding to cover the costs was not sound financial management. (See paragraphs 2.79 to 2.104)

Accountable and transparent decision-making

19. For 71 per cent of the procurements examined by the ANAO, an appropriate contractual arrangement was in place prior to works commencing and after approval had been obtained to enter the arrangement. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.13)

20. Sound and timely advice was not provided to inform decisions about whether to vary contracts. In aggregate, the contracts the APO entered between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2023 doubled in value during that period through contract amendment. The approval records for contract variations did not include advice on how value for money would be achieved and, for a number of high value contracts, approval was sought after costs were incurred. A quarter of the variations tested were entered after the related services had commenced and/or costs incurred. (See paragraphs 3.14 to 3.35)

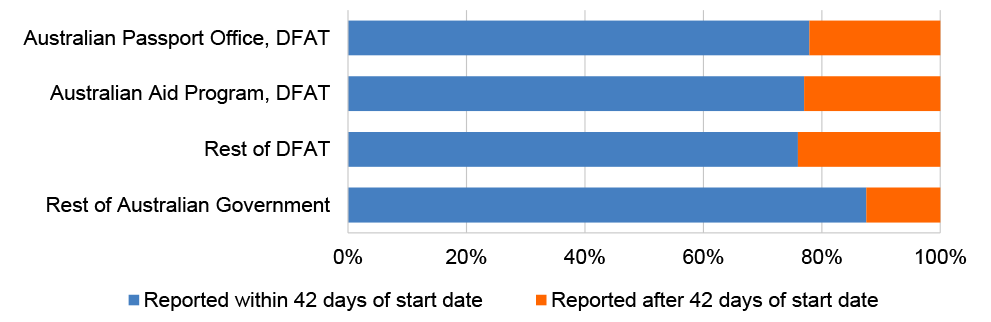

21. ANAO analysis of AusTender data between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2023 indicated that DFAT did not meet the Commonwealth Procurement Rules requirement to report contracts and amendments within 42 days of execution at least 22 per cent of the time. The extent of non-compliance increased to 44 per cent when the analysis was based on ANAO examination of the departmental records in a sample of 230 contracts and amendments. The AusTender reporting of 70 APO contracts examined was largely accurate. The reported descriptions of the goods or services procured was usually applicable but was also usually lacking in detail. The reported reasons given for 112 contract amendments examined did not contain sufficient detail to meet the minimum instructions in the AusTender reporting guide 81 per cent of the time. (See paragraphs 3.37 to 3.52)

22. Procurement activities fell short of ethical requirements. In response to ethical findings made by the ANAO in relation to a number of the procurements examined as part of this performance audit, the department advised the ANAO that it considers there are clear indications of misconduct involving a number of current or former DFAT officials and contractors as well as clear cultural issues. The department has commenced, or is considering, investigation (or referral) activity in relation to the conduct of at least 18 individuals in relation to various procurements examined by the ANAO. (See paragraphs 3.53 to 3.83)

23. The department’s central procurement team has not exercised sufficient oversight of the APO’s procurement activities. Departmental risk controls that have been documented have not been complied with by the APO and this non-compliance should have been evident to the central procurement team, and addressed. The department also does not have adequate arrangements in place for the identification and reporting of breaches of finance legislation. (See paragraphs 3.85 to 3.105)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.21

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve its planning of procurement activity for the Australian Passport Office, including but not limited to taking steps to assure itself that procurement planning requirements (internal to the department as well as those required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules) are being complied with.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.71

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade strengthen its procurement processes for the Australian Passport Office so that there is an emphasis on the use of genuinely open competition in procurement to deliver value for money outcomes consistent with the requirements and intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.78

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade include evaluation criteria in request documentation for all procurements undertaken for the Australian Passport Office, and procurement decision-makers ensure those criteria have been applied in the evaluation of which candidate represents the best value for money.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.106

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to strengthen its procurement policy framework by directly addressing the risk of officials being cultivated or influenced by existing or potential suppliers.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.36

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade strengthen its controls to ensure any contract variations are consistent with the terms of the original approach to market, and that officials do not vary contracts to avoid competition or other obligations and ethical requirements under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.84

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade examine whether procurements not included in the sample examined by the ANAO also include ethical and integrity failures, and subject any such procurements to appropriate investigatory action.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.94

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade strengthen oversight by its central procurement area of the procurement activities of the Australian Passport Office. This should include being represented on the evaluation team for each procurement activity of higher risk or value.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

24. The proposed report was provided to DFAT. Extracts of the proposed report were also provided to Alluvial Pty Ltd, Brink’s Australia Pty Ltd, Compas Pty Ltd, Community and Public Sector Union, Customer Driven Solutions Pty Ltd, Datacom Systems (AU) Pty Ltd, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, Department of Finance, Grosvenor Performance Group Pty Ltd, Hays Specialist Recruitment (Australia) Pty Ltd, Mühlbauer ID Services GmbH, Peoplebank Australia Ltd, Procurement Professionals Pty Ltd, Propel Design Pty Ltd, Randstad Pty Ltd, Serco Citizen Services Pty Ltd, Services Australia, UiPath S.R.L, Verizon Australia Pty Ltd and Yardstick Advisory Pty Ltd. The letters of response that were received for inclusion in the audit report are at Appendix 1. Summary responses, where provided, are included below.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The department values the ANAO’s independent review of procurement practices at the Australian Passport Office (APO). The audit came at a time when the department was assessing the effectiveness of the current procurement model. As a result of both reviews, the department’s procurement practices will be amended to improve compliance and efficiency. This will include the Finance Division taking more centralised and direct control over procurement activities, and additional resources to implement changes and provide enhanced oversight.

The ANAO audit highlighted the proactive steps the current Executive Director APO took to address procurement and cultural issues when she commenced with the department in early 2023. Work has continued, leading to the creation of a new Procurement, Finance and Assurance Section within APO. Additionally, the Internal Audit Branch has initiated a wide-ranging internal audit of procurement activities across the department.

Following the ANAO audit report and internal reviews, the department will also revise its Compliance and Assurance Framework as it relates to Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 obligations. The updated Framework will be purpose-built, adopt a risk-based approach, and include effective assurance mechanisms. The department has initiated activities to address specific areas of concern regarding actions of staff.

Compas Pty Ltd

Compas is concerned that the Proposed Report conveys an imputation that it has engaged in conduct that may not be in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Such an imputation is incorrect.

The relevant evaluation process was an internal DFAT process over which Compas, rightly, had no visibility. Given this, Compas cannot respond to, nor is it privy to, what processes were taken by DFAT to address the Panel Member’s affiliation to it.

Any deficiencies in the evaluation process cannot be attributed to Compas, and the final report should make this expressly clear in its findings. Any failure to do so could result in a reader being under a misapprehension that Compas had the ability to influence the process, did in fact influence the process improperly and, as a result, gained an improper advantage or benefit.

Should such a misrepresentation occur, this would have an unreasonably adverse effect on Compas’ reputation that it has built over nearly 40 years and have a deleterious effect on our business.

Propel Design Pty Ltd

Propel Design notes the extract provided by the ANAO. Propel Design submitted its tender for the procurement in question in accordance with all requirements under the Digital Marketplace (now BUYICT) and was not aware of any individuals appointed to the evaluation panel. We believe our employee was selected as the preferred contractor based on their skills and experience, as set out in their resumé and our responses to the selection criteria.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

25. Below is a summary of key messages that have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance

Procurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian citizens are entitled to be issued with a passport under the Australian Passports Act 2005 (the Passport Act). A passport enables travel across borders (with the necessary visas or entitlements) and within Australia it can also act as important proof of identity. Non-citizens may be eligible to apply for other types of travel documents.3

1.2 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for issuing passports to Australian citizens in accordance with the Passport Act, with delivery of passport services in Australia and overseas being one of DFAT’s three key outcomes. In July 2006, DFAT established the Australian Passport Office as a separate division to provide passport services. The Australian Passport Office has offices in each Australian capital city and it collaborates with Australian diplomatic missions and consulates to provide passport services to Australians located overseas.

1.3 DFAT is also the entity responsible for Australia’s international trade agreements. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) incorporate the requirements of Australia’s international trade obligations and government policy on procurement into a set of rules.

1.4 As a legislative instrument, the CPRs have the force of law.4 Officials from non-corporate Commonwealth entities such as DFAT must comply with the CPRs when performing duties related to procurement. Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.5 The issuing of passports to Australian citizens is an important function of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, undertaken by its Australian Passport Office. Between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023, the Australian Passport Office managed 331 contracts totalling $1.58 billion.

1.6 During the conduct of an earlier audit, Auditor-General Report No. 13 2023–24 Efficiency of the Australian Passport Office, the ANAO observed a number of practices in respect of the conduct of procurement by DFAT through its Australian Passport Office that merited further examination. The Auditor-General decided to commence a separate audit of whether the procurements DFAT conducts through its Australian Passport Office comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and demonstrate the achievement of value for money.

1.7 The audit provides assurance to the Parliament of the effectiveness of the department’s procurement activities in achieving value for money, and the ethics of the department’s procurement processes, noting that procurement is an area of continuing focus by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.5

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.8 The objective of the audit was to examine whether the procurements that DFAT conducts through its Australian Passport Office are complying with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

1.9 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have open and competitive procurement processes been employed?

- Has decision-making been accountable and transparent?

1.10 The audit focussed on procurement activities by the Australian Passport Office relating to contracts and contract variations that had a start date of between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023.

Audit methodology

1.11 The audit methodology included: examination of DFAT records; testing of a sample of procurements that established and amended contracts; analysis of DFAT’s SAP Contracts database6; analysis of AusTender data; and engagement with DFAT. The criteria applied to identify the audit population were as follows:

- procurement undertaken by the APO within DFAT, inclusive of contract amendments;

- inclusive of services procured from or through other Australian Government entities;

- inclusive of contracts procured by the APO and later transferred to the Information Management Division (IMD) in DFAT when the APO’s IT functions were consolidated into the IMD in 2022;

- with a maximum value of $10,000 or above, inclusive of contracts valued above this threshold where actual payment made fell below $10,000; and

- were active at any time between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023.

1.12 In summary, ANAO testing and analysis of APO procurement covered:

- high-level analysis of the 331 contracts totalling $1.58 billion that met the above criteria, of which 243 contracts (73 per cent) totalling $476.5 million (30 per cent) started after 30 June 2019;

- detailed examination of the establishment and variation of 73 contracts totalling $405.1 million that started after 30 June 2019, which equated to a sample size of 30 per cent by number or 85 per cent by value from this cohort;

- detailed examination of any post 30 June 2019 variations to 15 contracts totalling $1.02 billion that started before this date, which equated to a sample size of 17 per cent by number or 93 per cent by value from this cohort; and

- high-level analysis of contract notices on AusTender with a reported start date of 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023, which included 217 new contracts totalling $144.9 million and 249 amendments to new and existing contracts totalling $307.6 million published by DFAT for its APO conducted procurements.

1.13 The ANAO has co-operative evidence gathering arrangements in operation with entities. On 25 October 2023 the ANAO requested that DFAT provide relevant email account data by 8 November 2023. DFAT advised the ANAO on 15 November 2023 that it had downloaded the requested data, and then advised the ANAO on 23 November 2023 that it was withholding that data. As DFAT would not voluntarily provide the email account data, on 8 December 2023 the Auditor-General issued DFAT with a notice to provide information and produce documents pursuant to section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 by no later than close of business 11 December 2023. The process of providing the email account data to the ANAO was completed on 14 December 2023.

1.14 During the conduct of the audit, the ANAO provided detailed analysis of a number of procurements to DFAT. DFAT responded with clear statements as to where it considered practices had fallen short of the financial, procurement and/or ethical standards the entity expected. The ANAO’s analysis informed DFAT’s decision making as advised to the ANAO by the department in relation to 18 individuals already under investigation or considered to be ‘persons of interest’ by DFAT.

1.15 All financial values presented in this audit report are GST inclusive and have been rounded to the nearest dollar, where applicable. The financial values are as per those specified in the contract and/or reported on AusTender and may not reflect actual expenditure. The paragraph references to the CPRs in this report relate to the June 2023 version, which was in effect at the time of audit fieldwork. An updated version of the CPRs came into effect on 1 July 2024.

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $526,000.

1.17 The team members for this audit were Tracey Bremner, William Mussared, Jocelyn Watts, Joshua Carruthers, Michaelia Liu, Tracy Houston, Lachlan Miles and Brian Boyd.

2. Open and competitive procurement

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether open and competitive procurement processes had been employed.

Conclusion

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) did not employ open and competitive processes in the conduct of Australian Passport Office procurement. There were no procurements conducted between July 2019 and December 2023 by way of an open approach to the market. Of the 73 procurements examined in detail by the ANAO, 29 per cent involved competition where the department had not identified a preferred supplier prior to inviting quotes.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations with a particular focus on DFAT obtaining value for money in its procurement for the Australian Passport Office, including through greater use of open and effective competition, and on transparent selection processes. The ANAO also identified an improvement opportunity for the department.

2.1 Competition is a key element of the Australian Government’s procurement framework. Effective competition requires non-discrimination and the use of competitive procurement processes.7

2.2 Generally, the more competitive the procurement process, the better placed an entity is to demonstrate that it has achieved value for money. Competition encourages respondents to submit more efficient, effective and economical proposals. It also ensures that the purchasing entity has access to comparative services and rates, placing it in an informed position when evaluating the responses. Openness in procurement involves giving suppliers fair and equitable access to opportunities to compete for work while maintaining transparency and integrity of process.

Were the procurements appropriately planned?

DFAT did not appropriately plan the procurement activities for its Australian Passport Office. There was no overarching procurement strategy. The department engaged a contractor to develop a multi-year procurement strategy that was never completed. Overall, only 15 per cent of the 62 approaches to market examined by the ANAO met the minimum requirements at planning stage.

Australian Passport Office procurement planning

2.3 In order to draw the market’s early attention to potential procurement opportunities, each relevant entity must maintain on AusTender an annual procurement plan. The plan is to include the subject matter of any significant planned procurement and the estimated publication date of the approach to market.8

2.4 DFAT maintains an annual procurement plan on AusTender. As at June 2024 it did not include any planned procurement by the APO. Further, none of the 217 APO contracts reported on AusTender from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023 were linked to an approach to market that had been published in DFAT’s annual procurement plan.

2.5 The APO also does not have an overarching procurement plan or strategy in place. This is the case notwithstanding the department had, in September 2021, engaged a contractor through Procurement Professionals Pty Ltd at a cost of $102,168 to develop a multi-year procurement strategy, and to undertake a stocktake of APO memoranda of understanding (MOU). While invoices for the contractor’s services were paid, neither product was completed. A draft procurement strategy that was incomplete in significant respects was presented to the department in November 2021 which was followed by the contract being amended to increase the time period for delivery by more than six months (with no increase to the contract value) with DFAT advising the ANAO that it did not have a finalised APO Procurement Strategy (the hours remaining under the contract for this work were redistributed to increase other line items on the Purchase Order). The most recent version of the MOU register in the department’s records was incomplete and not as described in the contract9 and, instead of being developed by the contractor, a register was subsequently developed internally by the department in 2023. The procurement did not deliver value for money and had not been conducted ethically.

Estimating the value of a procurement

2.6 The value of a procurement must be estimated before a decision on the procurement method is made in order to assess whether or not the procurement value is greater than the relevant procurement threshold, which in this case is $80,000. If the procurement value is greater than the relevant procurement threshold, an Open Tender must be used or a Limited Tender condition sought. Additionally, DFAT’s procurement policy has extended the Mandatory Set-Aside arrangements of the Indigenous Procurement Policy to cover procurements with an estimated value between $10,000 and $200,000.10

2.7 Notwithstanding these requirements, 24 of the 73 contracts (33 per cent) examined in detail by the ANAO did not include any cost estimate. This is not in line with the CPRs and does not provide the department with the capacity to select the appropriate procurement method.

2.8 Where estimates were prepared, they were often unreliable. For the 49 contracts where there was an estimate, the aggregate contract value at 31 December 2023 was 139 per cent higher than the estimates. This included three contracts where the actual cost was less than half the estimate, and 14 contracts where the actual cost was more than double the estimated value.

2.9 The two most significant cost underestimations were a bulk labour hire contract with Randstad Pty Ltd (‘Randstad’) and contact centre contract with Datacom Systems (AU) Pty Ltd (‘Datacom’). The value of these two contracts at 31 December 2023 ($60.3 million and $91.2 million) were nearly seven times the estimated total costs. Further, the contract with Datacom has extension options remaining. For example, an amendment published on AusTender in July 2024 increased its value to $133.0 million for the first three years and two months — 10 times the five-year estimate of $13.2 million. The increase in cost through variations was not reflected in the risk rating, with all amendments assessed as ‘low risk’.

2.10 A common error in DFAT’s estimating was to not include the expected value of any extension options (although this was not the reason for the under-estimation of the Randstad or Datacom contracts, which were varied prior to any extension options being used). For 26 of the 49 contracts (53 per cent) where an estimate was prepared, that estimate did not include any extension options. The department’s approach is not compliant with the CPRs which requires (at paragraph 9.2) that ‘The expected value is the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract.’ (See also paragraph 2.17 below on advice to approvers.)

Individual procurement planning

2.11 DFAT has comprehensive, step-by-step guidance on its intranet to assist staff to plan and conduct procurements. The guidance is supported by a suite of departmental templates, links to Australian Government information and contact details for further assistance.

2.12 DFAT’s templates include a procurement plan for use in the scoping and pre-approvals phase of procurements valued over $1 million or assessed as medium or high risk. The ANAO examined 23 approaches to market that met this criterion, which established 31 of the contracts tested. A procurement plan was not completed for any of these 23 approaches to the market.

2.13 DFAT’s templates also include an email-based and a minute-based request for approval to approach the market. These are to evidence appropriate planning and to obtain financial delegate approval to seek quotes or tenders from potential suppliers. DFAT’s requirement to obtain delegate approval is consistent with Department of Finance guidance.11

2.14 Delegate approval was required for the 62 approaches to the market that established 70 of the 73 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO. (The APO used price lists when procuring the other three contracts, which were with Australian Government entities.) Delegate approval was obtained prior to approaching the market for 38 of the 62 approaches (61 per cent). Ten of the 24 approaches to market that breached this requirement were to establish contracts valued over $80,000.

Scale, scope and risk

2.15 The procurement method recommended to the delegate, and selected, should be the most appropriate for the procurement activity given the scale, scope and risk of the business requirement.12

2.16 In terms of scope, the requests to the delegate for all 38 approaches to market for which prior approval was obtained contained a description of the proposed goods or services and related timeframe (such as the initial contract term and proposed extension options). A draft Request for Quote was also included with 25 of the 38 requests for approval (66 per cent).

2.17 In terms of scale, the expected value of a procurement must be estimated before a decision on the procurement method is made. The expected value is the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract.13 Of the 38 approaches to market, the request to the delegate for:

- 13 approaches (34 per cent) contained the expected value of the proposed contract/s inclusive of any extension options;

- 24 approaches (63 per cent) contained an expected value that did not include the proposed extension options; and

- one approach did not contain an expected value.

2.18 Entities must establish processes to identify, analyse, allocate and treat risk when conducting a procurement.14 DFAT’s procurement templates include a risk register for assessing risks and for recording and monitoring controls. DFAT guidance outlines that procurement managers ‘must’ complete a risk assessment using the template for panel procurement valued at $1.5 million or over and for non-panel procurement at $1 million or over, and ‘should’ complete it for procurements below these thresholds. The risk register template had not been completed for any of the 62 approaches to market tested.

2.19 The request to the delegate for 35 of the 38 approaches to market for which prior approval was obtained contained a risk rating. In all 35 cases the risk rating was ‘low’, including for a procurement to engage seven suppliers at an estimated total value of $76.1 million. Of the three requests to the delegate that did not contain a risk rating:

- one was for an approach to market with an expected total value of $13.2 million (see paragraph 2.9);

- one was for an approach to market with an expected total value of $32.6 million (the approver was advised a risk assessment would be conducted as part of the evaluation, with the evaluation outcome minute recording an overall risk rating of ‘medium’); and

- one had not used DFAT’s request for approval template and resulted in a low value contract ($13,860).

2.20 Overall, for 11 of the 62 approaches to market examined (18 per cent) there was prior approval from a delegate that set out the procurement scope, expected maximum value and risk. Two of these 11 were over the threshold for requiring a procurement plan and a risk register — which none had — thereby decreasing the percentage of approaches that met the minimum requirements at planning stage to 15 per cent.

Recommendation no.1

2.21 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve its planning of procurement activity for the Australian Passport Office, including but not limited to taking steps to assure itself that procurement planning requirements (internal to the department as well as those required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules) are being complied with.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

To what extent were open approaches used?

None of the 243 contracts totalling $476.5 million the APO entered between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023 was let via an approach to the open market.

DFAT’s AusTender reporting indicates the APO procures by open tender from a panel arrangement 71 per cent of the time. The ANAO examined 53 contracts DFAT had reported this way and identified that for 15 contracts (28 per cent) the APO had deviated from the panel arrangement to the extent that the approach constituted a limited tender. The ANAO also examined 12 contracts valued over the $80,000 threshold reported by DFAT as let by limited tender. The approach taken for six of these contracts (50 per cent) did not demonstrably satisfy the limited tender condition or exemption from open tender that had been reported by DFAT. The department’s approach is inconsistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules which, in turn, reflect the requirements of the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (DFAT is the Australian Government entity responsible for Australia’s international trade agreements).

Requirement to use open tenders

2.22 Australia is party to a range of international trade agreements that include specific government procurement commitments. The Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines of January 2005 gave effect to Australia’s obligations for government procurement under the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement. Major changes to procurement requirements included the classification of procurements over a specified value as ‘covered procurements’ to which mandatory procedures applied and a general presumption of open tendering, with limited tendering available only in specific circumstances.

2.23 The relevant international trade obligations have continued to be incorporated in what are now the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The obligations are implemented through Division 2 of the CPRs. To a lesser degree, Division 1 also implements relevant obligations such as the requirement to treat all potential suppliers equitably and to publicly report contracts. Compliance with the CPRs therefore ensures compliance with those obligations.15

2.24 The CPRs are part of finance law and legally binding. As the Australian Government entity responsible for Australia’s international trade agreements, DFAT has the opportunity to demonstrate compliance with requirements to other public sector entities.

2.25 Australian Government procurement is conducted by open tender or by limited tender.

- Open tender ‘involves publishing an open approach to market and inviting submissions’.

- Limited tender ‘involves a relevant entity approaching one or more potential suppliers to make submissions, when the process does not meet the rules for open tender’.16

2.26 Officials must comply with the ‘rules for all procurements’ listed in Division 1 of the CPRs. Officials must also comply with the ‘additional rules’ listed in Division 2 when the estimated value of the procurement is at or above the relevant procurement threshold and when an exemption at Appendix A of the CPRs does not apply.17 As Department of Finance guidance has noted, open tender ‘is the “default” for all procurements valued above the relevant thresholds’.18 The relevant threshold for procurement by DFAT through its APO is $80,000.

Reported use of open tenders

2.27 Relevant entities must report contracts valued at or above the reporting threshold by publishing contract notices on AusTender. DFAT’s reporting threshold is $10,000. The information on contract notices includes the procurement method used to establish the contract. For purchases from panel arrangements, the original procurement method used to establish the standing offer is reported.

2.28 The ANAO examined the distribution by procurement method of the 217 contracts with a start date of 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023 that DFAT had reported for its APO activities as at 30 September 2023. The ANAO used DFAT’s reporting on its Australian Aid Program and on its other non-APO procurement activities, as well as the contract notices published by other Australian Government entities on AusTender, as comparator data.

2.29 DFAT had reported 73 per cent of its APO contracts as being procured by open tender, compared with 66 per cent of its Australian Aid Program contracts and 48 per cent of its other contracts. These proportions are higher than the 46 per cent collectively reported by other Australian Government entities. The results align with the relative proportions of contracts valued over the $80,000 threshold. Specifically, 71 per cent of the APO contracts had an initial value of $80,000 or more compared with 56 per cent of Australian Aid Program contracts, 43 per cent of other DFAT contracts and 42 per cent of other Australian Government contracts.

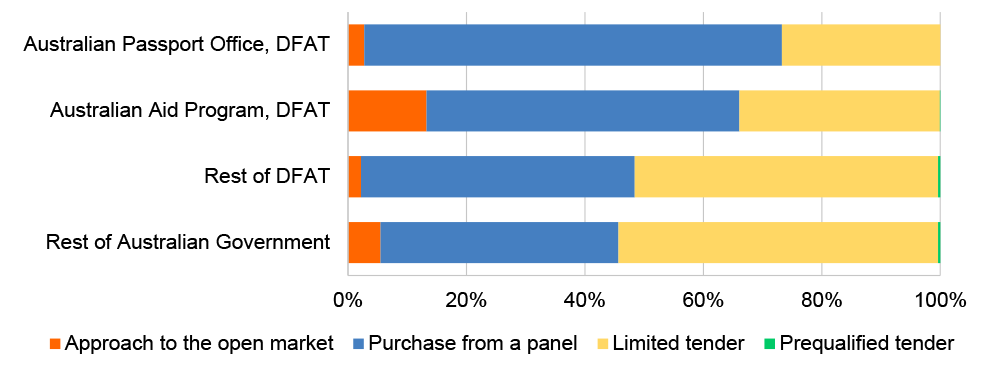

2.30 The ANAO separated the reported use of open tenders into two categories: contracts procured by approaching the open market, such as by publishing an open request for tender; and purchases from panel arrangements that were established by open tender.19 As per Figure 2.1, the APO reported using panel arrangements more frequently (71 per cent of the time) than the comparators (40 to 53 per cent of the time).

Figure 2.1: Contracts by reported procurement method by number

Note: Since 1 July 2019, the prequalified tender method was removed from the CPRs and phased out. There were no APO contracts reported against this method.

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data as at 30 September 2023 for parent contracts with a reported start date of 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023.

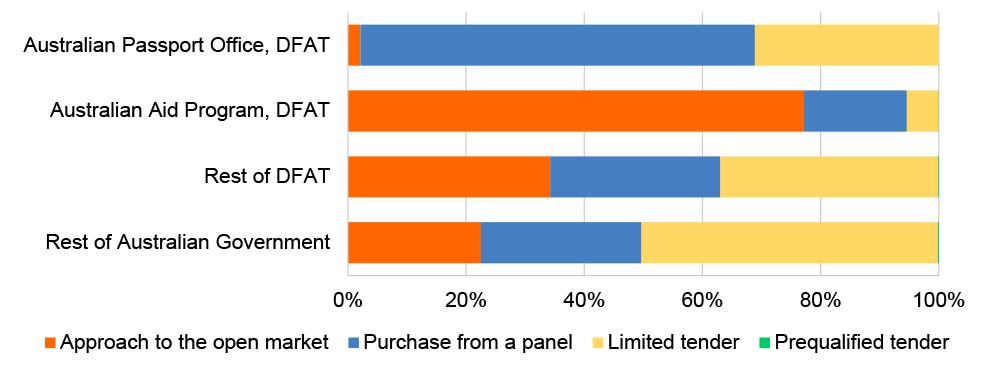

2.31 As the method selected should reflect the scale, scope and risk of the procurement, it would be expected that an analysis of procurement method by contract value would see an increased proportion of approaches to the open market. This was the case for the comparators, for which the proportion of approaches to the open market increased substantially when calculated by contract value (Figure 2.2). There was little difference, however, between the APO’s reported usage when calculated by contract value (Figure 2.2) as by contract number (Figure 2.1). This result is reflective of the APO’s approach of preferring to issue work orders under panel arrangements, which was evident from the ANAO’s testing of individual procurements as outlined below.

Figure 2.2: Contracts by reported procurement method by initial value

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data as at 30 September 2023 tor parent contracts with a reported start date of 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023.

Use of approaches to the open market

2.32 DFAT had reported six of the 217 APO contracts (three per cent) as procured by approaching the open market (Figure 2.1). The ANAO examined these six contracts and identified that all had been misreported. Five were purchases from panel arrangements established by open tender and so should have been reported as a use of the particular panel. The other one was a purchase from a standing offer established by limited tender and so should have been reported as a limited tender under a panel.

2.33 More broadly across the APO’s procurement activities, none of the 243 APO contracts totalling $476.5 million entered between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023 had been procured by publishing an open request for tender.

Procurement of secure delivery services

2.34 Running an open approach to the market may not necessarily generate effective competition if officials do not understand the market and what they are procuring, and/or if the specifications are unnecessarily restrictive. CPR 10.10 includes that, ‘In prescribing specifications for goods and services, a relevant entity must, where appropriate: set out the specifications in terms of performance and functional requirements …’.

2.35 An APO contract for the secure delivery of Australian travel documents had been let by direct source20 following an unsuccessful open request for tender, which itself had followed an unsuccessful panel approach. Despite two of the three methods used having met the reporting definition of ‘open tender’, DFAT had failed to generate competition despite there being a competitive market for those services.21 DFAT’s corporate procurement and security teams had provided feedback to the APO on its draft request for quote, with both questioning whether the highly prescriptive security requirements were appropriate. The security team suggested the APO ‘consider allowing the service provider to determine the operational requirement … What you want is assurance the service provider provides the appropriate vehicle to carry each shipment and has security measures in place to protect the shipment’. This advice was not followed. Instead, the requirements remained highly prescriptive.

2.36 Commencing August 2023, the contract was with Brink’s Australia Pty Ltd (‘Brink’s’) for the secure delivery of Australian travel documents and related items between the production centres in Craigieburn and Epping in Victoria and passport offices in each state and territory capital.

- The predecessor contract for secure delivery services was entered with G4S International Logistics (Australia) Pty Ltd (‘G4S’) in February 2017. G4S subsequently sold its Australian operations to Brink’s and the contract was novated to Brink’s in June 2020 on the existing terms.

- The contract with Brink’s was due to expire in February 2022. Although all extension options were exhausted, in the same month the contract was due to expire (February 2022) DFAT extended the contract to February 2023.22

- To establish a new contract, in December 2022 DFAT issued a request for quote to suppliers under the two-supplier ‘Courier and Transport Services for IT and Secure IT Equipment’ panel. Neither supplier quoted, with one explaining: ‘your RFQ’s statement of security requirements … fall well above the parameters of the Panel’.

- The department extended its contract with Brink’s by a further six months to 26 August 2023.

- The department published an open request for tender for ‘secure freight services’ on AusTender on 5 April 2023, which closed on 8 May 2023. No tenders were received.

- The department then conducted a direct-source limited tender with Brink’s and engaged them for an initial three-year term at $858,000.

2.37 In addition to not running a competitive limited tender, the department did not compare the pricing it received by direct source against that of other suppliers in the market when assessing value for money. It had been 11 years since it had last done so, as outlined below.

- The department benchmarked Brink’s 2023 proposed pricing schedule against Brink’s existing schedule.

- Brink’s existing schedule was established in 2017 via the procurement of G4S, which had submitted the sole compliant bid in an open tender and was the incumbent supplier.23

- The department had benchmarked G4S’s 2017 pricing schedule against G4S’s existing pricing schedule, established in 2016 via a direct-source limited tender with G4S.24

- The department had benchmarked G4S’s 2016 pricing schedule against G4S’s then existing pricing schedule. It was from a contract signed in February 2015, for services that had commenced in November 2014, which was attributed to a request for open tender published in July 2012. That open tender had attracted two bids, with the then incumbent G4S being the successful tenderer.25

Use of panel arrangements

2.38 DFAT had reported the majority of its APO contracts (71 per cent) as procured from a panel established by open tender. The ANAO’s detailed testing of 73 contracts included 53 contracts (73 per cent) that DFAT had reported as having been established this way. The ANAO identified that 15 of these 53 contracts (28 per cent) were procured by the APO in a manner inconsistent with the panel arrangement, with the effect that the procurement process constituted a limited tender approach.

2.39 When undertaking a panel procurement, every firm approached is to be an approved seller of those goods or services, otherwise it constitutes a limited tender. This was outlined in a previous ANAO audit that identified DFAT having engaged in the practice of requesting a quote from a supplier not on the panel and already working in DFAT.26 This was a practice observed in two of the contracts tested in this current audit indicating the department has not taken effective action to embed appropriate practices to address the issue raised in the 2014–15 performance audit. One instance resulted in a $704,949 contract as outlined at paragraph 2.67 and the other instance is a $133.0 million contract as follows.

2.40 On 23 February 2022 a contractor from the APO procurement team emailed two senior officials with decision-making responsibilities to advise them which out of five potential suppliers of inbound contact centre (call answering) services were on the Digital Marketplace panel. Two of the five were listed as ‘not included on the Digital Marketplace’. On 23 March 2022 one of the senior officials approved a request from APO procurement to approach three of the potential suppliers via the panel, including a supplier that was not on the panel. The request did not record that this supplier was not on the panel.

2.41 As one of the potential suppliers was not on the panel, the APO issued the request for quote by email instead of via the Digital Marketplace portal. The email stated the request had been sent to shortlisted suppliers under the Digital Marketplace panel. The matter was raised promptly by the potential supplier not on the panel upon receipt.

- The supplier emailed the APO on 24 March 2022 including: ‘I was wanting to confirm which [supplier] entity is shortlisted under the Digital Transformation Agency’s Digital Market Place that you have reached out to.’

- Within 10 minutes, the APO replied: ‘Is it possible to provide your phone number for a quick conversation regarding your query’.

- The supplier emailed the APO on 25 March 2022 including: ‘Thank you for the call yesterday – it really helped clear up my confusion around the Digital Marketplace … we are starting to work on our proposal as well as our assessment of the market place – and it is likely we will join it as recommended by you.’

2.42 All three invited suppliers submitted quotes. The relevant supplier was transparent about not being on the panel. The approved evaluation report, the approval to engage panel supplier Datacom for $6,990,553 and the three approvals to amend the work order with Datacom, inaccurately recorded that the APO had approached the Digital Marketplace panel. The amendments increased the value by 1,204 per cent to be $91,174,353, which DFAT reported as procured by open tender from a panel arrangement. The contract was amended in July 2024 to be $133,017,426; an increase of 1,803 per cent since it commenced in May 2022.27

2.43 As per Department of Finance guidance, a ‘panel cannot be used to purchase goods or services that fall outside the scope of the arrangement’.28 DFAT had used the Digital Marketplace Panel for two APO procurements of non-ICT services. Specifically, for an administrative assistant and for the services of an accountant.

2.44 Procurements from a panel are not subject to the rules in Division 2 of the CPRs.29 It does not follow that conducting a limited tender in breach of Division 2 can be remedied after the fact by issuing a work order under a panel. The APO’s practice of issuing work orders for procurements it conducted outside the panel arrangement is no different in substance to that explicitly prohibited by paragraph 10.36 of the CPRs, whereby ‘A relevant entity must not use options, cancel a procurement, or terminate or modify an awarded contract, so as to avoid the rules of Division 2 of these CPRs.’30 The related paragraph of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement explicitly prohibits entities from designing or otherwise structuring a procurement in order to avoid their obligations.31 DFAT is the Australian Government entity responsible for the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement.

2.45 The following provides an example of the APO conducting a limited tender by direct-source for services valued over its $80,000 threshold — in breach of the CPRs — and then using a work order as the contractual mechanism so as to report it as an open tender.

- An official from the APO had a ‘coffee catch up’ with a contractor from Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (‘Deloitte’) who was working elsewhere in DFAT.32 The official emailed the contractor later that day, including ‘The APO requires financial support … Please feel free to forward me a proposal and quote if you feel Deloitte’s has the capacity to assist us in this space.’ There was no reference to a panel arrangement in this invitation. Deloitte responded with a quote.

- The official forwarded the quote to the APO’s procurement team, including ‘Let me know what the next steps are to proceed’. The procurement team sent the official a request to enter into an arrangement with Deloitte to provide an accountant for 12 months at a cost of $330,000. The official approved the request as financial delegate. The approval record inaccurately stated that Deloitte had ‘provided an unsolicited proposal’.

- The approval record further stated that, ‘The method of procurement is considered Open tender by engaging Deloitte Consulting using a work order via the Digital Transformation Agency’s Digital Marketplace (SON3413842)’. The official had not approached Deloitte via this panel and the nature of the services fell outside the scope of the arrangement.33

- DFAT issued Deloitte a work order under the panel. The work order was varied eight times, with the value increasing by 989 per cent to be $3,592,589 and the term increasing from 12 months to 30 months, which was beyond the extension options provided. The approval records for the variations inaccurately said that ‘the original engagement process was conducted via the Digital Transformation Agency’s Digital Marketplace’. DFAT reported the procurement method as open tender from a panel arrangement.34

2.46 The APO had neither approached the panel, nor entered a work order under it, for one of the contracts it let by direct-source and then reported as a panel procurement.

- The instigation for the procurement was a director from Customer Driven Solutions Pty Ltd inviting a senior official out for coffee on 9 March 2022 and, following a discussion with that official and a contractor from the APO’s procurement team, emailing the official on 10 March 2022.

- On 11 March 2022, the APO invited the supplier to quote to provide services of the nature outlined in the supplier’s email of the previous day. There was no reference to a panel arrangement in this invitation. Customer Driven Solutions responded with a quote.

- The APO’s estimated value of the services, and the quote received, exceeded the $80,000 threshold and so the rules of Division 2 applied. CPR 9.5 states, ‘A procurement must not be divided into separate parts solely for the purpose of avoiding a relevant procurement threshold’. An official approved an initial $77,000, just under the threshold, with the record noting ‘any further funding can be approved under a separate Section 23 and contract variation’. A further $110,000 was approved within three months of the contract starting. Over the contract’s 15 month term, the value increased by a total of 276 per cent to be $289,773.

- The approval records for the initial contract and the variations inaccurately said ‘DFAT will use the Digital Transformation Agency’s Digital Marketplace (SON3413842) Deed of Standing Offer to enter into a work order with Customer Driven for these activities’. The APO did not enter a work order. Instead, it raised and amended a purchase order within its financial system (see paragraph 3.10). DFAT reported this direct-source limited tender as an open tender from a panel arrangement.35

Use of limited tenders

2.47 DFAT had reported 58 of the 217 APO contracts published on AusTender (27 per cent) as procured by limited tender (Figure 2.1). APO procurement with an estimated value at or above $80,000 can only be conducted by limited tender in accordance with paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs, or when the procurement is exempt as detailed in Appendix A of the CPRs. The relevant limited tender condition or exemption must be reported on AusTender. Officials must also prepare a written report that includes ‘a statement indicating the circumstances and conditions that justified the use of limited tender’.36

2.48 The ANAO examined the relevance of the limited tender condition or exemption DFAT had reported for the 12 out of the 58 APO contracts that had an initial value above $80,000. For six of the contracts checked, DFAT had reported a relevant exemption or limited tender condition and prepared a written record that justified its use.

2.49 For half of the contracts checked, the use of limited tender did not demonstrably comply with the CPRs. One contract was reported against the limited tender condition ‘Supply by a particular business: for works of art’, which was irrelevant to the security clearance services procured. Four contracts were reported against the limited tender condition ‘Supply by particular business: due to an absence of competition for technical reasons’ without a convincing justification. For example, on the recorded basis of there being ‘an absence of competition’, approval was given to invite eight suppliers to compete in a limited tender for customer survey services estimated at $550,000. That the invitation was issued to eight suppliers does not support the position recorded that there was no competition for the provision of customer survey services.

2.50 The other contract found non-compliant had been reported as exempt from the rules of Division 2 in accordance with paragraph 17 of Appendix A of the CPRs. The exemption is for procurement valued up to $200,000 from a small to medium enterprise (‘SME’) and it requires that the Indigenous Procurement Policy first be satisfied. The APO had not satisfied the requirements of this exemption, or of the Indigenous Procurement Policy which applied to the procurement, and the written records were not accurate or complete.

- The written approval to approach the SME and three other suppliers did not identify that the approver had already met with the SME (Grosvenor Performance Group) and received a 40-page quote for $103,273.

- A request for quote was then formally issued and two responses received: one from Grosvenor; and one from a ‘big four’ accounting firm. The approach to market did not therefore satisfy the Indigenous Procurement Policy.

- The recorded approval to engage Grosvenor at $103,273 inaccurately stated that the competing quote had been submitted by an Indigenous enterprise. The approver would have known this was not the case given the approver, and an official who worked to them, had assessed the quotes. The contract and the subsequent variation to $113,874 were incorrectly reported by DFAT as exempt under paragraph 17 of Appendix A.

To what extent were competitive approaches used?

A competitive approach was used to establish only 29 per cent of the 73 contracts tested by number or 25 per cent by value. This involved the APO inviting more than one supplier to quote in a process that did not have a pre-determined outcome. On 19 occasions the procurement approach was not genuine as the purported competitive process did not, in fact, involve competition.

Encouraging fair competition

2.51 The CPRs state that procurements should ‘encourage competition and be non-discriminatory’.37

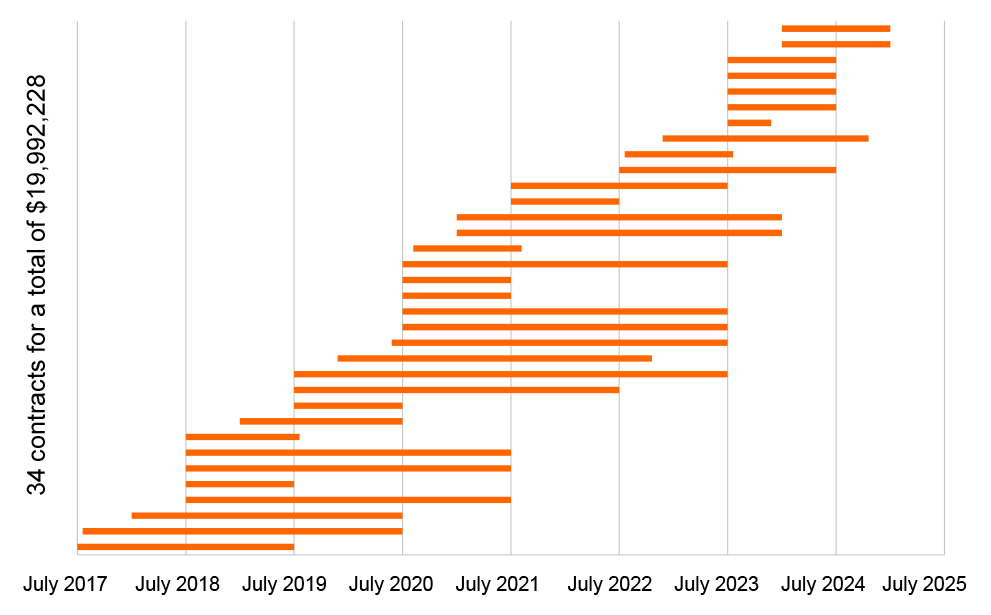

2.52 Releasing requests for tender to the open market encourages competition and provides all potential suppliers an opportunity to compete for work. As noted at paragraph 2.33 above, none of the 243 APO contracts entered between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2023 had been procured this way. Rather, the opportunity to quote for work totalling $476.5 million was by invitation.

2.53 Alluvial Pty Ltd (‘Alluvial’) was the most used supplier of the 155 suppliers represented across the 331 APO contracts in the audit population. Alluvial received 25 of the APO contracts (eight per cent) with Hays Specialist Recruitment (Australia) Pty Ltd (‘Hays’) and Infront Systems Pty Ltd receiving the equal next highest number at 13 contracts each (four per cent). Of the contracts with Alluvial reported on AusTender with a start date from 1 July 2017, DFAT accounts for 70 per cent by number and 76 per cent by value as at 23 July 2024. There were:

- 35 contracts with DFAT totalling $21,969,691 reported; and

- 15 contracts across five other entities totalling $6,945,033 reported.

2.54 Within the audit population, there were 158 APO contracts for non-bulk labour hire that totalled $98.8 million. Alluvial attracted the highest proportion of this work by contract number (16 per cent) and by contract value (17 per cent). The DFAT work flowing to Alluvial over the period July 2017 to December 2023 is presented in Figure 2.3. Twenty-six of the 34 contracts presented were procured by the APO. The other eight were procured by DFAT’s Information Management Division (IMD) between 1 August 2022 and 16 December 2023, with seven of those eight being the re-engagement of contractors initially procured by the APO.38 The 34 contracts with Alluvial covered the engagement or re-engagement of 19 individuals, two of whom were Directors of the firm.

Figure 2.3: DFAT contracts with Alluvial for labour hire as at 31 December 2023

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT data.

Extent to which a single supplier was invited to quote

2.55 During the scope of this audit, AusTender did not provide transparency on how many suppliers were invited to quote for each of the contracts reported. Changes introduced to AusTender from 1 July 2024 included: ‘Where a contract was procured via a limited tender, or standing offer arrangement the number of suppliers approached must be reported on the contract’.39 This change followed recommendations made to the Department of Finance by the ANAO40 and the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.41 Entities are to implement the AusTender reporting changes by 1 July 2025. As at 1 September 2024, DFAT had not implemented the 1 July 2024 changes.

2.56 The ANAO identified that the APO had invited only one supplier (‘direct-sourced’) for 33 of the 73 contracts examined in detail. This represents 45 per cent by number or 31 per cent by value. The ANAO also considered whether the supplier direct-sourced was the sole supplier available in the market or on a mandatory use panel. The results are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Number of suppliers invited to quote in each of the 73 contracts examined

|

On panel or in market |

One supplier was invited |

Multiple suppliers were invited |

||

|

|

Contracts |

Value ($) |

Contracts |

Value ($) |

|

Sole supplier |

6 |

22,528,382 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Multiple suppliers |

27 |

101,316,336 |

40 |

281,232,075 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT records, with contract values as at 31 December 2023.

2.57 The APO had direct-sourced 27 of the 67 contracts (40 per cent) for which multiple suppliers were available in the open market or on the panel approached. For 20 of these 27 contracts (74 per cent) there was no approval record setting out the basis for the direct-source approach (see paragraph 2.14). The ANAO identified that 11 of the 20 were with an incumbent supplier or contractor.

2.58 Of the seven contracts for which there was an approval to approach the market, the recorded basis for direct-sourcing for:

- five contracts totalling $50.4 million related to re-engaging the incumbent supplier or contractor (see example below);

- one $858,722 contract was that ‘The APO identified [contractor] through internal recommendations and word of mouth’; and

- one $632,104 contract, involved an approval related to a multi-supplier approach for a different procurement, with the APO then direct-sourcing one of the unsuccessful candidates into ‘a newly defined role’.

2.59 An example of a direct-source approach to re-engage an incumbent that has been reported as open tender was the procurement of an embedded contractor to manage the APO’s procurement team. The incumbent had been engaged by the APO for 10 years via various contracts with various suppliers through various procurement panels.

- The process was initiated by the manager emailing a subordinate in the procurement team, who was also a contractor, saying:

Hey mate, With my contract coming up – if APO wants to re-engage me – I would like to go through [staff member] at Peoplebank [Peoplebank Australia Ltd] for the engagement and preferably for six month contract terms, if possible. Happy to get that kicked off whenever you are.

- The subordinate replied:

To [sic] easy, I’ll get started on the approach direct to Peoplebank for your position.

I’ll do the internal paperwork and liaise with [the staff member] to receive a proposal.

- The approval to approach the market included a contradictory statement on the procurement method used, and recorded that:

The APO has an ongoing need for the continuation of this role and is looking to retain the services of the incumbent [manager’s name] due to [their] extensive knowledge and understanding of the APO environment … The procurement is subject to Division 2 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules … and will be conducted as an Open Tender under the [panel] … A direct approach to Peoplebank will be undertaken to re-engage the incumbent resource allocation of [manager’s name].

- The request for quote was emailed directly to the Peoplebank staff member whose details had been supplied by the incumbent. DFAT subsequently reported this direct-source procurement as open tender.

2.60 As manager of the APO procurement team, the above-mentioned contractor was in a position to influence the conduct of DFAT procurement. The ANAO identified examples where contractors with pre-existing social connections to this individual were engaged by DFAT. These included instances where the individual played a significant role in the procurement, such as requesting quotes, being a member of the evaluation panel and providing advice to delegates. For example, the department’s email and calendar records for the manager evidenced there had been regular social interactions with the contractor engaged to produce a procurement strategy (see paragraph 2.5). The manager was instrumental in that direct-source procurement. In a further instance, the manager had used their network of supplier contacts (including via their DFAT email account) to assist an individual introduced by a mutual acquaintance to find contract work in a different entity and was provided with a gift voucher as a gesture of thanks. The manager subsequently facilitated the engagement of that individual by the APO via a direct-source approach.42

Direct sourcing from panel arrangements

2.61 The CPRs state that, ‘To maximise competition, officials should, where possible, approach multiple potential suppliers on a standing offer’.43 The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit recommended in August 2023 that ‘the Department of Finance amend its guidance on the use of panels to make it explicit that … panel procurement should involve multiple competing tenders from panel members, with sole-sourcing from a panel generally considered inadequate to demonstrate value for money’. The Department of Finance agreed to the recommendation.44

2.62 DFAT had reported 53 of the contracts examined in detail as let by open tender from a panel arrangement (see paragraph 2.38). The APO had approached a single supplier on a multi-supplier panel when establishing 13 of these contracts (25 per cent). DFAT reported eight of the 13 contracts (62 per cent) against the Digital Marketplace panel.

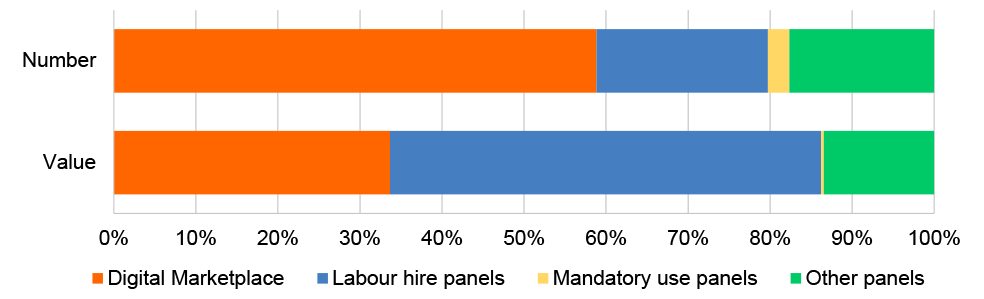

2.63 Becoming an approved seller on the Digital Marketplace does not involve a competitive process.45 Direct sourcing from the Digital Marketplace therefore means that both the Deed and the Work Order were established without competitive pressure being applied. Further, as at July 2024 there were 3,570 approved sellers across 18 service categories from which to generate competition. The Digital Marketplace was the most frequently used panel by the APO, as per Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: 153 APO contracts by panel arrangement by number and by initial value

Note: Digital Marketplace panel 1.0: SON3413842. Labour hire panels: SON867801; SON3557594; and SON3538332. Mandatory use panels: SON3622041; SON3390763 and mandatory component of SON3541738. Other panels: SON3403954; SON3637213; SON3463478; SON3490955 and non-mandatory component of SON3541738.

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data as at 30 September 2023 for APO parent contracts with a reported start date of 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2023 and procurement method of open tender from a panel arrangement.

Extent to which the multi-supplier approaches were competitive

2.64 The ANAO identified that the department had invited more than one supplier to quote for 40 of the contracts examined in detail, representing 55 per cent by number or 69 per cent by value (see Table 2.1). The number invited for 39 of these 40 contracts46 ranged from three to 27 and averaged nine suppliers. These figures include seven contracts for bulk labour hire services established in June 2019 following an approach to those seven suppliers. While it was a multi-supplier approach, it was not a competitive approach.

- The department identified the seven of its 15 incumbent suppliers with the highest number of ongoing temporary contractors engaged across the passport office network. The APO identified a panel that included the seven suppliers and then invited them to quote. The APO did not invite any of the other 28 suppliers on that panel (SON3557594).

- The department intended to re-engage all seven. They were not competing on price and capability for future work. While one supplier submitted its quote late it was not excluded. Further, while two suppliers were assessed by DFAT to not satisfy one or more of the evaluation criteria they were also not excluded. One supplier offered a discounted rate in its quote that the APO then did not include in the contract.

- The value of each contract had been determined prior to approaching the market, and the contracts with the seven suppliers pre-prepared prior to receiving the quotes. The department offered the seven suppliers contracts totalling $38,039,536. This included awarding contracts to two suppliers that had been assessed as offering ‘poor’ value for money.

2.65 In reference to the above procurement of bulk labour hire services, DFAT advised the ANAO in June 2024 that:

Competition is a key element of DFAT’s procurement framework as set out in the DFAT Procurement Policy and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. DFAT considers that this procurement process should have tested the market beyond a limited number of incumbent suppliers, selected based on volume of existing contractors, by providing new suppliers with an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities.

2.66 For one of the 40 contracts established following a multi-supplier approach, DFAT released the request for quote via the BuyICT portal47 to all 1,620 approved sellers of ICT labour hire services on the Digital Marketplace panel. The request was for the services of a ‘commercial relationship manager’. Fifty-two approved sellers responded, putting forward a total of 71 candidates. This, however, was not a genuinely competitive procurement process.

2.67 The department had separately emailed the request to a firm (Customer Driven Solutions) that was not an approved seller. Further, in a breach of probity, the department had emailed a contractor from that firm a copy of the approval to approach the market containing the estimated procurement value and hourly rate. The firm put forward two candidates. These two were the only ones out of the 73 potential candidates that the department assessed as ‘suitable’, with one then contracted into the position despite not holding the required security clearance. The process had not involved checking compliance with the security requirement, assessing quotes against the evaluation criteria or interviewing potential candidates. DFAT reported the $704,948 contract as let by open tender from the Digital Marketplace panel.48

2.68 Another example of an approach to market that was not genuine was a procurement intended to re-engage an incumbent contractor into a ‘change manager’ position. Prior to DFAT issuing a request to four sellers on the Digital Marketplace, the chair of the tender evaluation panel had already met with the incumbent supplier and received a proposal. While a further 18 sellers on the Digital Marketplace requested to be included none were given access by the department to the procurement opportunity, with the contract awarded to the incumbent.49

2.69 In total, the ANAO identified 19 procurement processes out of the 40 examined (48 per cent) where the purported competitive process did not, in fact, involve competition.50 This practice is inconsistent with both the intent and the requirements for fair treatment (such as CPR 7.12, 10.8 and 10.13). It is also inconsistent with CPR 5.2 which advises that participation in procurement imposes costs on potential suppliers and that those costs should be considered when designing a process (given the evidence is that suppliers were being asked to quote for work where there was already an intended candidate).

2.70 Overall, the department had already identified its preferred supplier or candidate prior to approaching the market for 52 contracts totalling $305.5 million, which equates to 71 per cent of the 73 APO contracts examined by number or 75 per cent by value.

Recommendation no.2

2.71 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade strengthen its procurement processes for the Australian Passport Office so that there is an emphasis on the use of genuinely open competition in procurement to deliver value for money outcomes consistent with the requirements and intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Were evaluation criteria included in request documentation and used to assess submissions?

For 14 per cent of contracts tested, evaluation criteria were included in request documentation with those same criteria used to assess submissions.

Evaluating submissions on a transparent basis

2.72 The CPRs require relevant evaluation criteria to be included in request documentation to enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair, common and appropriately transparent basis.51 Request documentation must include a complete description of evaluation criteria to be considered in assessing submissions and, if applicable to the evaluation, the relative importance of those criteria.

2.73 Of the 73 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO, 32 (44 per cent) included evaluation criteria in the Request for Quote documentation. As such, the majority were not compliant with paragraph 10.6.d of the CPRs.

2.74 For 14 of these 32 procurements (44 per cent) quotes were not then evaluated against criteria. This meant there was not a clear and transparent basis for the procurement outcome.

2.75 Of the 18 procurements where quotes were evaluated against criteria, in eight instances the criteria used were not those that had been included by DFAT in the request documentation. This meant that the suppliers invited to quote had not been informed by the department as to the basis on which the contract would be awarded. In two instances, the evaluation panel used different evaluation criteria from that advised to the potential suppliers in the request documentation and then referenced the original criteria when seeking delegate approval of the procurement outcome: