Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement of the International Centre for Complex Project Management to Assist on the OneSKY Australia Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to examine whether Airservices Australia has effective procurement arrangements in place, with a particular emphasis on whether consultancy contracts entered into with International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM) in association with the OneSKY Australia project were effectively administered.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The civil air traffic management system operated by Airservices Australia (Airservices) and the separate system operated by the Department of Defence for military air traffic are both due to reach the end of their economic lives in the latter part of the current decade. The December 2009 National Aviation White Paper identified expected benefits from synchronising civil and military air traffic management through the procurement of a single solution to replace the separate systems. Under the OneSKY Australia program, Airservices is the lead agency for the joint procurement of a Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS). A Request for Tender (RFT) for the joint procurement was released on 28 June 2013. The RFT closed on 30 October 2013, with six tenders being received (including from the incumbent providers of both the Airservices and Defence air traffic management platforms).

2. On 27 February 2015, it was announced that Airservices, in partnership with Defence, would be entering into an Advanced Work contracting arrangement with the successful tenderer, Thales Australia, as a next step for the delivery of the OneSKY initiative. As at April 2016, negotiations for the finalisation of acquisition and support contracts for the provision of the combined civil-military system were ongoing.

3. At a public hearing held on 18 August 2015 as part of its ongoing inquiry in the performance of Airservices, the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee (Senate Committee) raised a number of concerns regarding conflict of interest matters in respect to Airservices’ procurement of services via the International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM) to assist in the OneSKY Australia program. This audit was undertaken following requests subsequently received from the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development and the Senate Committee that the ANAO examine Airservices’ oversight and implementation of the OneSKY program.1

4. This audit is the first in a two-stage approach to those requests. Its objective was to examine whether Airservices has effective procurement arrangements in place, with a particular emphasis on whether consultancy contracts entered into with ICCPM in association with the OneSKY Australia program were effectively administered.

5. The second performance audit will examine the conduct of the OneSKY Australia tender process from initiation to finalisation of the selection and contracting process, with a focus on the achievement of value with public resources in accordance with appropriate probity protocols. The consideration of any probity impacts on the tender process will be examined within the scope of the second audit.

Conclusion

6. A key shortcoming in Airservices’ procurement policies and procedures is that they do not give appropriate emphasis to the use of competitive processes. In addition, Airservices routinely failed to adhere to its policies and procedures in procuring services from ICCPM. As a result, Airservices’ procurement of services from ICCPM, on an exclusively sole-sourced basis, did not deliver value for money.

7. Airservices demonstrated a lack of organisational commitment to the effective implementation of probity principles in respect to the ICCPM arrangements. It was reasonably foreseeable that Airservices’ contracting of ICCPM to assist with the OneSKY Australia project would give rise to perceptions of conflicts of interest and, potentially, actual conflicts of interest. But the ICCPM engagements were not effectively managed so as to ensure the OneSKY tender process was free of any concerns over conflict of interest that could impact on public confidence in the outcome.

Supporting findings

Airservices’ engagement of ICCPM

8. Over the period examined by the ANAO (2012 to the end of 2015), Airservices had in place a procurement governance framework that sought to achieve value for money from procurement processes. Two key shortcomings were that the procurement governance framework did not:

- address Airservices entering into strategic partnerships and alliances; or

- adequately contemplate, or regulate, non-competitive approaches being adopted for procurements with a value of $50 000 or more.

9. In May 2013, Airservices and ICCPM agreed to enter into a strategic partnership for the duration of the OneSKY program. There was no business case prepared. In addition, no performance indicators were established to enable monitoring and evaluation of whether the partnership was delivering the expected benefits. It was quite common for Airservices to use the relationship with ICCPM to engage individuals to undertake particular roles akin to an employee for extended periods, rather than build the organisation’s own capability.

10. The strategic relationship did not represent a procurement in itself. Each subsequent decision to engage specified personnel, or to acquire other services, via ICCPM represented discrete procurement decisions.

11. Airservices has made extensive use of ICCPM to assist with the delivery of the OneSKY Australia program. Since 2012, there have been 42 engagements of ICCPM employees and sub-contractors through 18 procurement processes. The engagements were given effect through six contracts, 10 contract variations and four uses of an on-call services schedule under one of the contracts. Under the various contractual arrangements, Airservices agreed to pay ICCPM total fees of more than $9 million.2

12. Departures from Airservices’ documented procurement policies and procedures were common in the approval processes for the various ICCPM procurements. Internal controls intended to promote compliance were regularly bypassed. Where they were applied, the controls were often ineffective. In addition, the records made by Airservices of each procurement decision were often perfunctory. This approach to recording decisions to spend money, together with internal controls being bypassed, contributed to a lack of transparency over the decisions to procure services from, or through, ICCPM.

13. Airservices sole-sourced each of the ICCPM procurements. It also largely operated as a price-taker. Quotes from ICCPM were accepted by Airservices without seeking to benchmark the proposed rates to similar services obtained by other Commonwealth entities3, or actively seeking to negotiate reduced rates particularly in circumstances where initial short-term engagements became extended into long-term engagements.

14. The daily rates agreed to be paid by Airservices for the services of individual contractors ranged from $1 500 per day up to $5 000 per day (for an eight hour day). The rates paid for initial, short-term high level strategic engagements were similar to, or the same as, those paid for the same individuals to deliver on long-term assignments that involved full-time, or close to full-time, work.

15. Overall, Airservices’ approach to contracting ICCPM to assist with the delivery of OneSKY Australia was ineffective in providing value for money outcomes.

Airservices’ probity management framework

16. Airservices’ documented procurement framework requires that probity be a key consideration in undertaking procurement processes. This includes requirements to effectively identify and manage potential, actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

17. Two internal audits of governance within Airservices’ Future Service Delivery (FSD) group (which incorporates the OneSKY program) have been undertaken, reporting in April 2014 and August 2015. Whilst the scope of the first report included some consideration of the probity records management associated with the Probity Plan for the CMATS tender, neither involved an examination of the conduct of the tender evaluation or contract negotiation processes from a probity perspective.

18. The Probity Plan and Protocols established for the CMATS joint procurement process, together with the engagement of an external Probity Advisor as well as an external Probity Auditor, provided a reasonable basis for managing the probity aspects of the tender process. But Airservices did not commission independent probity audits of any phase of the tender process subsequent to the release of the RFT.

Probity management in engaging ICCPM and its subcontractors

19. Neither the decision to enter into a strategic relationship with ICCPM for the duration of the OneSKY program, nor any of the 18 sole-sourced procurements that occurred both prior, and subsequent, to that relationship being established, addressed probity matters. In particular, on no occasion was there documented consideration as to whether the engagement would give rise to potential actual or perceived conflicts of interest that should either be avoided (by not proceeding with the procurement) or for which a specific management strategy should be established.

20. ICCPM sub-contractors with links to tenderers (including through past employment and as a result of the membership of the ICCPM board) became involved in the evaluation of competing tenders. They subsequently undertook contract negotiations with the successful tenderer. But Airservices did not identify or actively manage the attendant probity risks.

21. Overall, Airservices approach to administering declared conflicts and monitoring ICCPM subcontractors’ compliance with the Probity Plan and Protocols was inconsistent and largely passive. This was reflected in a number of missed opportunities to avoid or effectively manage potential conflict of interest concerns associated with engaging key subcontractors via ICCPM. There were also foregone opportunities to accept offers from ICCPM to establish assurance mechanisms at the corporate level, and to obtain and implement advice from the external Probity Advisor.

22. That those opportunities were not taken up by Airservices, together with other shortcomings identified by the ANAO in the management of probity, is indicative of an inadequate appreciation within Airservices of probity principles and their effective implementation.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.35 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia address systemic failures in the adherence to the organisation’s procurement policies and procedures and the cultural underpinnings of those failures. Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 2.54 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia improve the value for money it obtains from major and strategic procurement activities by:

Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 3.19 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia improve its procurement framework by including enhanced guidance in relation to:

Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 4.96 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia proactively manage probity in procurement activities by:

Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.5 Paragraph 4.100 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia’s governance arrangements address:

Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.6 Paragraph 4.154 |

The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia enhance its procedures for managing probity in procurement processes to require documented consideration of the potential for actual or perceived conflicts of interest to arise when engaging external contractors to participate in tender evaluations and contract negotiations and, where relevant, the management strategies that are to be applied. Airservices Australia response: Agreed. |

Entity response

23. Airservices Australia provided formal comments on the proposed audit report, which are included at Appendix 1. Its summary response is set out below. Formal comments were also provided by four other recipients of the proposed report (ICCPM, Ashurt Australia, Mr Harry Bradford and Mr Andrew Pyke). They are also included in appendices.

Airservices’ summary response

Airservices acknowledges that improvements can be made to its procurement framework and accepts the recommendations made by the ANAO in the proposed audit report. Airservices has initiated action to address each of the recommendations.

However, Airservices holds significant concerns about commentary in the report regarding the management of probity as it relates to the overall OneSKY tender process, which could lead the reader to draw conclusions in relation to the integrity of the tender process that are not supported by evidence.*

Airservices maintains that the tender evaluation arrangements in place were robust, and strongly refutes any suggestion that perceived conflicts at any stage created, or had the potential to create, an actual conflict of interest that could adversely impact the integrity of the OneSKY tender process.

ANAO comments on Airservices’ summary response

* The analysis and findings that support the audit conclusions are set out in detail in the chapters of the audit report. Based on the audit work undertaken to date, the ANAO has not made a conclusion as to whether actual conflicts of interest arose and impacted on the actual tender process (a matter that will be examined in the second performance audit—see paragraph 1.12).

1. Background

The OneSKY Australia program

1.1 Airservices Australia (Airservices) is responsible for managing Australia’s airspace in accordance with the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation.4 Airservices is principally funded by revenue from industry, involving charges for enroute, terminal navigation and aviation rescue and firefighting services. The level of charges is based on five year forecasts Airservices prepares of activity levels (including traffic volumes), operating costs and capital expenditure.

1.2 Airservices provides civilian airspace management via The Australian Advanced Air Traffic Management System (TAAATS).5 The existing air traffic management (ATM) platform is operated under contract by Thales Australia (Thales), utilising hardware originally installed in 1996. There has been a continual program of incremental software upgrades to meet new requirements and technologies. The platform’s life and associated contract with Thales were due to expire in 2015. A further hardware upgrade and associated deed of variation to the existing support contract with Thales extended the operational capacity of the existing system, but Airservices identified limits to the capacity to extend the economic life of type beyond 2018. The program initiated by Airservices for consideration of future ATM options was the Air Traffic Management Future Systems program (AFS program).

1.3 The Department of Defence (Defence) is responsible for military aviation operations and air traffic control (including at airports with a shared civil and military use). At approximately the same time as the TAAATS platform was commissioned, Defence commissioned a separate ATM platform for military aircraft, known as the Australian Defence Air Traffic System (ADATS). ADATS is supplied under contract by Raytheon Australia Pty Ltd (Raytheon). ADATS is similarly due to reach the end of its useful life in the latter part of this decade. Following the cessation of initial consideration of systems harmonisation, Defence initiated phase three of Project AIR5431 to replace ADATS.

1.4 The December 2009 National Aviation White Paper identified expected benefits from synchronising civil and military air traffic management. The activities identified in the White Paper for the implementation of a comprehensive, collaborative approach to nation-wide air traffic management included the procurement of a single solution to replace the separate systems.

1.5 Delivery of the joint initiative commenced in 2010, with a Request for Information being issued to industry. The Airservices AFS program and Defence AIR5431 Phase 3 project are now represented jointly as OneSKY Australia. Within the overall OneSKY Australia program, Airservices is the lead agency for the joint procurement of a Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS). CMATS is intended to be delivered through contracts between Airservices and the successful tenderer, with a separate agreement being established between Airservices and Defence for the on-supply of services and goods/supplies. A Request for Tender (RFT) for the joint procurement was released on 28 June 2013. The RFT closed on 30 October 2013, with six tenders being received (including from the incumbent providers of both the Airservices and Defence ATM platforms).

1.6 On 27 February 2015, it was announced that Airservices, in partnership with Defence, would be entering into an Advanced Work contracting arrangement with the successful tenderer, Thales, as a next step for the delivery of the OneSKY initiative. As at April 2016, negotiations for the finalisation of acquisition and support contracts for the provision of the combined civil-military system were ongoing.

Matters raised by Senate Inquiry

1.7 At a public hearing held on 18 August 2015 as part of its ongoing inquiry in the performance of Airservices, the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee (Senate Committee) raised a number of concerns regarding conflict of interest matters in respect to Airservices’ procurement of services via the International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM) to assist in the OneSKY Australia program. In particular:

- the engagement of a member of the ICCPM Board to undertake the Lead Negotiator role involving contract negotiations with the successful tenderer Thales, whose Managing Director was also (then) Chair of the ICCPM Board; and

- the role of an Airservices employee (and former ICCPM employee and subcontractor to Airservices) in recommending approval of a substantial extension to a contracting arrangement with ICCPM, given his spouse’s role as ICCPM Managing Director and CEO.

1.8 The Committee sought assurances from Airservices as to how the apparent actual and/or perceived conflicts of interest had been managed. The Committee expressed dissatisfaction with the advice provided by Airservices, including in relation to whether the Airservices Board had been made aware of relevant matters relating to the ICCPM arrangements.

Allens probity review

1.9 Following the Committee hearing, the Airservices Board commissioned an external review of the probity arrangements in relation to the OneSKY program, focussed on the matters raised by the Senate Committee. The review was conducted by legal firm, Allens Linklaters (Allens). A draft report was provided to the Airservices Board on 9 September 2015 and the final report on 27 October 2015. The Board agreed to implement all recommendations arising from the report of the Allens review by 30 November 2015 and, in May 2016, Airservices advised the ANAO that this occurred.

1.10 Not all relevant information relating to Airservices’ relationship with ICCPM was provided to Allens. In particular, Airservices did not provide Allens with advice or documentation associated with a May 2013 decision (see paragraph 2.13) to establish a ‘strategic partnership’ with ICCPM for the duration of the OneSKY program. Airservices also did not provide Allens with all documentation concerning the role played by ICCPM sub-contractors in the evaluation and contract negotiation processes.6 Nor did Allens engage with ICCPM in conducting its review. Further, the Allens review did not address the question of advice provided to the Airservices Board of any conflict of interest matters caused by ICCPM’s involvement in the OneSKY project.7

Audit approach

1.11 This audit was undertaken following requests received in August 2015 from the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development and the Senate Committee that the ANAO examine Airservices’ oversight and implementation of the OneSKY program. The requests were made as a result of issues raised in the context of the Senate Committee’s inquiry.

1.12 This audit is the first in a two-stage approach to those requests.8 Its objective was to examine whether Airservices has effective procurement arrangements in place, with a particular emphasis on whether consultancy contracts entered into with ICCPM in association with the OneSKY Australia program were effectively administered. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Does Airservices have appropriate procurement policies and procedures in place?

- Was the engagement of ICCPM in association with each phase of the OneSKY project based on transparent and effective procurement and contract management procedures?

- Were the ICCPM engagements effectively managed so as to ensure the CMATS joint procurement tender process was free of perceived, potential or actual conflicts of interest that may impact on public confidence in the outcome or, where conflicts arose, they were appropriately managed?

1.13 The audit methodology involved examining relevant Airservices records, including emails, relating to: procurement policies and procedures; selection, engagement and tasking of ICCPM in association with OneSKY; the involvement of ICCPM personnel in each phase of the CMATS tender process and related communications of tender information; the establishment and administration of probity protocols, particularly conflict of interest and information disclosure provisions; and the conduct, consideration and outcomes of the Allens review. In addition, evidence (including sworn testimony from a number of persons and documentation from ICCPM and Allens) was obtained using the powers provided by section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997.

1.14 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $420 000.

2. Airservices' engagement of ICCPM

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether Airservices has appropriate procurement policies and procedures in place, as well as whether the various engagements of ICCPM were based on transparent and effective procurement processes.

Conclusion

Airservices’ procurement policies and procedures seek to achieve value for money from procurement processes. But a key shortcoming is that they do not give appropriate emphasis to the use of competitive processes.

In May 2013, Airservices and ICCPM agreed to enter into a strategic partnership for the duration of the OneSKY program. There was no business case prepared and no performance indicators were established to enable monitoring and evaluation of whether the partnership was delivering the expected benefits. The strategic relationship did not represent a procurement in itself. Each subsequent decision to engage specified personnel, or to acquire other services, via ICCPM represented discrete procurement decisions.

Airservices has made extensive use of ICCPM to assist with the delivery of the OneSKY Australia program. Since 2012, there have been 42 engagements of ICCPM employees and sub-contractors through 18 procurement processes, via six contracts. Under the various contractual arrangements, Airservices agreed to pay ICCPM total fees of more than $9 million.a

Airservices sole-sourced each of the ICCPM procurements. It was common for the key elements of the processes employed to be inconsistent with the organisation’s procurement policies and procedures. In addition, the records made by Airservices of each procurement decision were often perfunctory. This approach to recording decisions to spend money, together with required internal controls over the approval processes being bypassed on a number of important occasions, contributed to a lack of transparency over the decisions to procure services from, or through, ICCPM.

In addition to applying no competitive pressure, there were few occasions where Airservices attempted to benchmark the quoted rates, or to negotiate on those rates. The daily rates agreed to be paid by Airservices for the services of individual contractors ranged from $1 500 per day up to $5 000 per day (for an eight hour day). The rates paid for initial, short-term high level strategic engagements were often similar to, or the same as, those paid for the same individuals to deliver on long-term assignments that involved full-time, or close to full-time, work. Overall, Airservices’ approach to contracting ICCPM to assist with the delivery of OneSKY Australia was ineffective in providing value for money outcomes.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations. The first emphasises the importance of adhering to the organisation’s procurement policies and procedures. The second is focused on value for money being obtained when Airservices procures consultancy services, with a particular focus on greater use of competitive selection processes.

Note a: All figures in this ANAO report are GST exclusive.

Does Airservices Australia have appropriate procurement policies and procedures in place?

Airservices’ procurement policies and procedures are, in most respects, appropriate. However, a key shortcoming is that they do not give appropriate emphasis to the use of competitive processes.

2.1 Under the Commonwealth’s financial framework, Airservices is not required to comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which are issued by the Finance Minister and apply to all non-corporate Commonwealth entities. Rather, as is the case with most corporate Commonwealth entities9, Airservices develops and implements its own procurement policies and procedures. Those policies and procedures are required to meet general obligations on the organisation that it promote proper use of resources and employ effective internal controls.

2.2 Over the period examined by the ANAO (2012 to the end of 2015), Airservices had in place a procurement governance framework that included:

- a Finance Policy issued by its Board;

- various versions of a procurement management instruction;

- documented procurement workflows, updated from time to time and tailored according to the estimated whole of life value of the goods and/or services being procured;

- a documented contract variations workflow, which was updated from time to time; and

- a delegations structure to govern the exercise of financial powers and functions.

2.3 The Finance Policy is sound. It refers to the importance of making efficient, effective, ethical and economical use of resources. It also seeks to promote the achievement of value for money from procurement processes.

2.4 In many respects, the procurement management instructions and workflows were also sound. For example, the documented processes sought to promote open and effective competition for procurement opportunities; there are requirements to retain appropriate documentation of procurement processes; and the procedural documents advocate the importance of probity and ethical behaviour (including in relation to identifying and managing conflicts of interest).

2.5 In addition, the contract variation workflow clearly sets out processes for identifying: the reason for any variation; the development of a variation strategy; the development, approval and signing of variation documentation; and management of the variation. Consistent with better practice procurement processes10, the contract variation workflow specifies that:

If the variation is for additional scope and term, a determination will be made by the Procurement Manager as to whether the additional requirement is significant or not significant. If the variation is significant, this will be treated as a new procurement.

2.6 Two key shortcomings are that the procurement governance framework does not:

- address Airservices entering into strategic partnerships and alliances. This is notwithstanding that the organisation had agreed, in response to a 2009 internal audit, to develop a considered approach to managing strategic partnerships11; or

- adequately contemplate, or regulate, non-competitive approaches being adopted for procurements with a value of $50 000 or more. Specifically:

- a minimum of three quotes are required to be obtained for procurements valued between $50 000 and $300 000 (identified as ‘major’ procurements in the Airservices framework). The documented workflow provides that the ‘Manager, Organisational Procurement’ can approve an exemption where Airservices is ‘unable to seek three quotes’. But:

- no version of the documented framework outlined the criteria that would be applied when deciding whether to grant any such exemptions, or set out any recordkeeping or accountability requirements12; and

- the method to be used when seeking approval for an exemption (specified in an earlier version of the workflow) is no longer specified; and

- adopting an open approach to the market is not explicitly specified as the required or preferred approach to procurements of $300 000 or more (identified as ‘strategic’ procurements). Rather, the requirements include developing:

- an acquisition strategy that, among other things, addresses market research, project timings and resources, the procurement methodology and an evaluation plan; and

- a suite of tender documents including conditions of tender, the scope of work, draft conditions of contract and tender response schedules.

- a minimum of three quotes are required to be obtained for procurements valued between $50 000 and $300 000 (identified as ‘major’ procurements in the Airservices framework). The documented workflow provides that the ‘Manager, Organisational Procurement’ can approve an exemption where Airservices is ‘unable to seek three quotes’. But:

2.7 In May 2016, Airservices advised the ANAO that a Management Instruction in relation to strategic alliances had been issued with effect from 4 April 2016.

What is the International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM)?

ICCPM is an unlisted non-profit public company limited by guarantee under the Corporations Act 2001. It was originally established with the assistance of the then Defence Material Organisation (DMO) in 2007 as the College of Complex Project Managers Limited to support and encourage research and learning in the field of complex project management. It changed its name to ICCPM in October 2008. In 2011, ICCPM commenced an income diversification strategy to generate alternate revenue from sources other than fees from its partner organisations. Airservices has been the largest financial contributor to the revenue that ICCPM has generated from consulting work. For example, the $4.8 million in consultancy fees and expenses paid by Airservices between 2012–13 and 2014–15 equated to 75 per cent of the revenue reported by ICCPM over that period from consulting work. A further $1.0 million had been paid to December 2015 (when ANAO audit fieldwork was undertaken).

No performance indicators were established to enable monitoring and evaluation of whether the strategic partnership between Airservices and ICCPM was delivering the expected benefits (including, the extent to which Airservices’ internal capability was being built). It was quite common for Airservices to use the relationship with ICCPM to engage individuals to undertake particular roles akin to an employee for extended periods, rather than build the organisation’s own capability.

2.8 ICCPM is an unlisted non-profit public company limited by guarantee under the Corporations Act 2001. The entity was originally established with the assistance of the then Defence Material Organisation (DMO) in 2007 as the College of Complex Project Managers Limited. It changed its name to ICCPM in October 2008. The company constitution outlines that:

The ICCPM is established as a public benevolent institution to support and encourage research and learning in the field of complex project management around the world and will pursue these purposes and activities for the public benefit.

The predominant object for which the ICCPM is established is to facilitate the management and delivery of complex projects around the world.

The ICCPM may also do such other things as are incidental or ancillary to the attainment of the predominant object of the ICCPM including (without limitation);

(a) act as a peak body for complex project management;

(b) advance complex project management knowledge and practice; and

(c) educate persons in complex project management.

2.9 In its initial years of operation, ICCPM was primarily reliant upon the annual fees paid by entities that had agreed to become funding partners. This included DMO and certain aeronautical and defence industry participants, including Thales Group (incorporating Thales Australia), Boeing (incorporating Boeing Defence Australia), Lockheed Martin and BAE Systems Australia (each of which was a respondent to the CMATS RFT).13 Given the likely complexity of the OneSKY Australia program and its lack of recent experience with a project of that magnitude, Airservices became an ICCPM corporate partner in September 2010 so as to be eligible for representation in advisory groups, focus groups and communities of practice.

2.10 In March 2011, the ICCPM Board agreed to the introduction of a revised Partner Charter that included the introduction of an Associate Partner level. This led to the establishment of the ICCPM’s Associate Partner Network. This Network consists of a range of individuals, companies and education providers with expertise in various fields related to complex project management. Each Associate Partner is contracted directly to ICCPM. Their services are provided to organisations via a subcontracting arrangement through ICCPM. The organisation’s Strategic Overview 2014–2019 outlined that the establishment of this ‘professional solutions’ stream was an alternate revenue generation strategy for ICCPM.

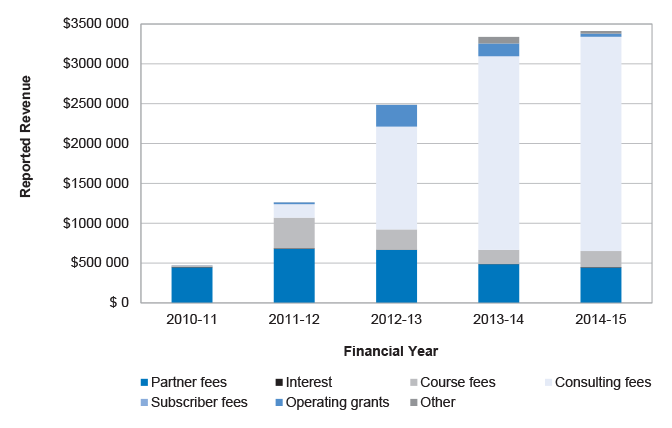

2.11 Between 2011–12 and 2014–15, ICCPM’s reported revenue from partner fees reduced by more than one-third from $676 643 to $443 207. As illustrated by Figure 2.1, over the same period revenue from consulting fees increased 15-fold from $170 775 to nearly $2.7 million.

2.12 Between 2012–13 (when Airservices started obtaining consulting services through ICCPM) and December 2015, Airservices paid ICCPM a total of $5.8 million in consultancy fees and expenses. Between 2012–13 and 2014–15, the payments from Airservices equated to 75 per cent of the revenue reported by ICCPM as deriving from consulting work. This indicates that Airservices has been the single largest contributor to the substantial growth reported by ICCPM from its ‘professional solutions’ revenue generating strategy.

Figure 2.1: ICCPM Revenue: 2010–11 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of financial statements lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Strategic partnership between ICCPM and Airservices

2.13 In May 2013, Airservices wrote to ICCPM accepting a proposal from ICCPM in relation to the AFS program (renamed on 1 July 2013 as OneSKY Australia).14 Specifically, the correspondence signed by Airservices:15

- agreed that the relationship would be in the nature of a strategic partnership for the duration of the OneSKY program (with that arrangement being in addition to, and separate from, the existing corporate partnership agreement under which Airservices pays an annual membership fee of $50 000 to ICCPM);

- stated that the building of capability within Airservices ‘must be a focus of ICCPM at all times’;

- outlined an intention to use an existing contract between Airservices and ICCPM as the engagement mechanism, with ICCPM to prepare schedules to that contract so that assistance with strategic planning and tender evaluation planning/implementation could commence in May 2013; and

- stated that each contractor engaged through ICCPM would be required under the probity plan established for the CMATS tender to have a probity briefing and execute a conflict of interest declaration prior to commencing work.

2.14 The approach taken to developing and formalising this strategic partnership did not involve any approach to the market that would have identified any other possible strategic partners, what they could offer the organisation and the related costs and benefits. As it eventuated, the cost of the partnership has been significant.

2.15 It was also inconsistent with key elements of the strategic alliance management instruction that had been approved in July 2010, but not published. For example, there was no business case prepared by Airservices and no performance indicators were established to enable monitoring and evaluation of whether the partnership was delivering the expected benefits (including, the extent to which Airservices’ internal capability was being built). In this latter respect, the ANAO’s analysis was that it was quite common for Airservices to use the relationship with ICCPM to engage individuals to undertake particular roles akin to an employee for extended periods, rather than build the organisation’s own capability.16

How extensively has Airservices contracted with ICCPM in relation to the OneSKY Australia program?

Airservices has contracted extensively with ICCPM in relation to the OneSKY Australia program. The contracted services have been very broad, with 42 engagements made in areas such as training and project management education, provision of strategic advice, delivery of technical services, general managerial support, assistance with the evaluation of tenders and the negotiation of contracts, including with the successful tenderer. The 42 engagements have been transacted under six contracts, involving total payable fees of more than $9 million. One of the contracts was varied on two occasions and another on eight occasions. In addition, an on-call services schedule under one of the contracts was exercised on four occasions.

2.16 Between April 2012 and August 2015, Airservices procured consultancy services from ICCPM on 18 occasions. For these 18 procurements, Airservices entered into six consultancy contracts with ICCPM. One of those contracts was varied and extended on two occasions. Another was varied and extended on eight separate occasions. One of those variations established an on-call services schedule under the contract, which Airservices made use of on four occasions (see further at paragraphs 2.22 to 2.25).

2.17 Figure 2.2 provides an overview of the various procurements. It illustrates that, while some contract variations extended the timeframe over which already contracted services would be delivered, it was more common for Airservices to use contract variations to obtain further services from ICCPM instead of, or in addition to, extending the delivery timeframes for already contracted services. In one instance, a contract with an initial value of $589 100 was varied and extended on a number of occasions involving a total potential contract value of $8.3 million.

Figure 2.2: Overview of Airservices’ OneSKY Australia contracts with ICCPM

Source: ANAO analysis of data from Airservices and ICCPM.

Strategic relationship with ICCPM

2.18 As outlined at paragraph 2.13, in May 2013 Airservices and ICCPM agreed by way of an exchange of letters to enter into a strategic partnership for the duration of the OneSKY program. Airservices did not document at that time, or subsequently, the nature of the services it intended to obtain from or through ICCPM, the expected cost or how it would satisfy itself that sole sourcing consulting assistance from or through ICCPM would provide value for money. Further, it was not until December 2013 that contractual arrangements were put in place to give effect to the strategic partnership. This involved the third variation to Contract 2013/7595 that had been signed in April 2013. Drafts of this variation had begun to be prepared in June 2013, but it took some six months for this particular contract variation to be finalised and signed.

2.19 Over time, Airservices’ reliance on ICCPM resources grew considerably in terms of scope, duration and influence. This was particularly the case after the strategic partnership had been agreed.

2.20 Prior to the strategic relationship being agreed, the initial contracts involving ICCPM were education-related or for the provision of short-term strategic or organisational planning advisory services, and of relatively low value. After the exchange of letters agreeing to a strategic partnership, Airservices began contracting more extensively with ICCPM for strategic advice, as well as for high level reviews of the OneSKY program. This was followed by contracts to provide project management assistance to senior managers of the OneSKY project so as to progress the preparation and release of the CMATS RFT. It also extended to ICCPM providing more general staff support to senior managers, in the nature of chief of staff services, executive support services and assistance with strategic planning.

2.21 The more long-term, and expensive, contracts were entered into after the CMATS RFT had been issued on 28 June 2013. ICCPM sub-contractors played important roles in the tender evaluation process, in terms of the overall approach/strategy, providing subject matter/technical expertise and contributing to key decisions. In addition, ICCPM sub-contractors were engaged by Airservices for contract negotiation assistance, both at a technical level and to fill the Lead Negotiator and Deputy Lead Negotiator positions.17

Establishment of the on-call services arrangement

2.22 The third variation to Contract 2013/7595 established an on-call services schedule. This schedule provided Airservices with flexibility to engage services from ICCPM in seven ‘activity areas’. These were: Tender Evaluation Working Group evaluation member of subject matter expert; collaboration cell; secretariat services; day courses; organisational change; project management; and team selection and composition.

2.23 In effect, the on-call services schedule established a panel consulting arrangement, albeit with only one provider on the panel. As indicated by Figure 2.2, Airservices used the on-call services schedule on four occasions, as follows:

- at the time the schedule was established in December 2013, Airservices accepted a quote for 11 engagements to the value of $1.36 million (two of the quoted engagements did not have a cost quoted, with Airservices clarifying in January 2015 that the value of those two engagements was $347 500);

- in May 2014, Airservices agreed to a quote for obtaining the services of both a Lead Negotiator and Deputy Lead Negotiator via ICCPM for six months from 1 April 2014 to 30 September 2014. Airservices operated on the basis those engagements were able to be accessed via the on-call services schedule despite contract negotiation services not being reflected in any of the listed ‘activity areas’;

- in October 2014, the Lead Negotiator and Deputy Lead Negotiator’s engagements were extended for a further eight months (to 31 May 2015); and

- in June 2015, the Lead Negotiator and Deputy Lead Negotiator’s engagements were extended for a further twelve months (to 31 May 2016), and three other engagements made. The total value of the engagements executed through the June 2015 process was $2.03 million.

2.24 The total contract value of the four occasions the on-call services schedule was used across 15 engagements was $6.17 million.

2.25 The contract variation to include the on-call services schedule was undertaken without the endorsement of Airservices’ Office of Legal Counsel (OLC). In June 2015, in light of concerns raised by OLC, the contract was varied to revise the process for preparing and authorising an order for on-call services, and to expand the definition of on-call services to include contract negotiation support.

Payments made

2.26 To deliver the contracted services to Airservices, ICCPM sub-contracted to seven member companies of its Associate Partner Network as well as to a professional services firm. Two ICCPM employees were also involved in providing various contracted services. In total, 12 individuals (including the two ICCPM employees) were involved in delivering the contracted services to Airservices across 42 engagements.

2.27 The total fee value associated with the various contracts between Airservices and ICCPM (including variations) was $9.01 million.18 The majority ($6.47 million or 72 per cent) of this was to be on-paid by ICCPM to the relevant sub-contractor. ICCPM was entitled to retain $1.56 million of the fees Airservices had agreed to pay for ICCPM sub-contractors. In addition, two ICCPM employees were engaged by Airservices to provide support to senior executives, with fees of $971 551 contracted to be paid to ICCPM.19

2.28 As at January 2016, the total amount paid to ICCPM in relation to the various OneSKY consultancy contracts was $5.78 million (see Table 2.1). The difference between the contracted amount and the amount paid largely reflects:

- that it was common for Airservices to enter into a new contract, or vary an existing contract, before the original contract had been fully drawn down; and

- the Lead Negotiator contracted through ICCPM resigned in November 2015, with the Deputy Lead Negotiator taking on the role of Lead Negotiator and an Airservices employee then being appointed to the Deputy role. Consistent with a recommendation from the Allens review, the new Lead Negotiator contract was signed directly between Airservices and the contracted personnel’s company (Keyholder Pty Ltd) rather than via an ICCPM sub-contracting arrangement.

Table 2.1: Payments made by Airservices to ICCPM in relation to OneSKY Australia contracts: July 2011 to January 2016

|

|

Fees paid for |

ICCPM sub-contractor payments |

|

||||

|

Nature of services |

ICCPM employees $’000 |

HC Bradford & Associates P/L $’000 |

Keyholder P/L $’000 |

Other sub-contractors $’000 |

Fees retained by ICCPM $’000 |

Expenses reimbursed $’000 |

Total $’000 |

|

Strategic advice, reviews and education |

27 |

121 |

27 |

75 |

52 |

14 |

315 |

|

Support to Airservices executives |

612 |

72 |

10 |

118 |

61 |

4 |

878 |

|

Request for Tender preparation and issue, and program delivery |

Nil |

126 |

362 |

Nil |

118 |

10 |

615 |

|

Tender evaluation and contract negotiation, and establish commercial arrangements with Defence |

Nil |

1 265 |

1 218 |

499 |

678 |

308 |

3 968 |

|

Total |

639 |

1 584 |

1 616 |

692 |

909 |

336 |

5 777 |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of Airservices and ICCPM records.

Was the approval of the various ICCPM procurements in accordance with Airservices’ procurement framework?

Departures from Airservices’ documented procurement policies and procedures were common in the approval processes for the various ICCPM procurements. Internal controls intended to promote compliance were regularly bypassed. Where they were applied, the controls were often ineffective. In addition, the records made by Airservices of each procurement decision were often perfunctory.

2.29 For 15 of the 18 procurements, the decision to engage ICCPM was recorded by way of one or more approval memos. Memos were prepared and signed in relation to each of the larger value procurements, but not the lower value procurements, as follows:

- there were no approval memos prepared for the first and second contracts for ICCPM to assist with OneSKY Australia (signed in April/May 2012 and June 2012), with values of $25 000 and $20 000 respectively;

- an approval memo was prepared on 18 July 2012 in respect to the $117 600 third contract (2012/6665), and memos were also prepared for the September 2012 and November 2012 variations to that contract that had aggregate values of $412 000;

- a memo was prepared in April 2013 to enter into Contract 2013/7595 with a value of $589 100. Approval memos were also prepared for the eight variations to that contract between July 2013 and May 2015 (one of which was to revise the process for preparing and authorising an order for on-call services, and expand the definition of on-call services to include contract negotiation support) and the four occasions on which Airservices accessed the on-call services scheduled under that contract. The variations to that contract and the accessing of the on-call services schedule had a combined total value of $7.72 million;

- there was no approval memo for a $27 000 contract signed in October 2013 for a review of tender evaluation readiness; and

- approval memos were prepared in June and August 2015 for a $100 000 engagement for a progress and status review of the OneSKY program.

2.30 For those 15 procurements where approval memos were prepared, they set out the need/reason for the procurement, some relevant background and the purpose of each engagement covered by the procurement. The memos also evidenced involvement by senior Airservices executives in the procurement processes.20

2.31 Airservices’ procurement processes and workflows require approval memos and the underlying document to be endorsed by OLC and the Manager, Organisational Procurement prior to a contract being executed. Only eight of the 15 procurements where a memo was prepared were endorsed by both OLC and the Manager, Organisational Procurement. Of the remaining seven procurements:

- four were not endorsed by either OLC or the Manager, Organisational Procurement;21

- two were endorsed by the Manager, Organisational Procurement but not by OLC; and

- one was endorsed by OLC but not by the Manager, Organisational Procurement.

2.32 In two instances, a memo was endorsed by a procurement or legal officer within Future Service Delivery (FSD), being the division within Airservices responsible for the OneSKY program. However, reliance on staff from within the business division undertaking the procurement runs counter to the intention of the procurement procedures (of ensuring compliance across all business groups).

2.33 In any event, the ANAO’s analysis was that obtaining the required endorsements was ineffective as a control for ensuring compliance with Airservices’ procurement policies and procedures. Specifically, despite most of the approval memos carrying one or both of the endorsements required from the OLC and the Manager, Organisational Procurement, the ANAO’s analysis of the various memos was that key elements of Airservices’ procurement policies and procedures had not been adhered to. Of particular significance was that:

- memos for only two of the 15 procurements with a memo explicitly outlined that ICCPM was being sole sourced. Memos for four procurements noted that contracting was necessary as Airservices lacked the required capability. That alternative external sources for the contracting task had been considered was raised in only one instance. Overall, the approach was inadequate in providing a rationale for, and accountability over, the decision to sole source more than $8.9 million in consultancy contracts;

- value for money was not discussed in the approval memos supporting eight of the 15 procurements. Of the seven that mentioned value for money, in one case (being the memo for the engagement of a configuration manger) there was a specific section on the subject of value for money. This section falsely claimed that the rates ‘were market tested and found to be competitive against comparable service offerings from other service providers’.22 Memos supporting another procurement stated that costs would be monitored to ensure value for money was obtained, but there was no documentary evidence that this was actually done. Approval memos for three other procurements suggested that Airservices had attempted to negotiate on the consultancy rates;

- there was no consistency in Airservices’ approach to including or excluding GST from the estimated cost of a proposed engagement; quantifying the possible cost of any extension options; and providing an estimate for reimbursable travel and other expenses; and

- the approach to including quotations to support the approval memo also varied markedly. Quotes were attached to the memos for eight of the procurements, but not for the other seven. In one instance, the quote was incomplete—the November 2013 quote was for $1.36 million, and this was the amount the then Chief Executive Officer (CEO) was asked to approve (and did approve). However, the quote did not include expected outlays for two of the line items (for two separate ‘Strategic Advisers’). In January 2014, Airservices wrote to ICCPM advising that the quote of $1.36 million had been approved by the CEO and clarifying that the amount for the two Strategic Advisers was capped at $347 500 for the 2014 calendar year (based on total number of days work). This means that, as a consequence of Airservices not having defined the work effort expected to be required of the two Strategic Advisers, the quoted amount, and the amount submitted for approval, had been understated by 26 per cent.

2.34 On two occasions, the procurement memo identified that the cost of the proposed ICCPM engagement was not provided for within the existing project budget. In both cases, approval was nevertheless recommended notwithstanding that the memo did not include any proposal for funding the procurement. On two occasions, the memo advised the approver that the relevant positions would be funded ‘within the OneSKY Australia program’. The remaining memos were silent on whether funds to meet the estimated cost of engaging ICCPM were available within the project budget. In this context, Airservices has identified an increase in OneSKY program costs as one of a number of factors contributing to the organisation’s overall costs being greater than had been projected when the current Long Term Pricing Arrangement was finalised.

Recommendation No.1

2.35 The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia address systemic failures in the adherence to the organisation’s procurement policies and procedures and the cultural underpinnings of those failures.

Airservices Australia response: Agreed.

Did Airservices’ procurement processes achieve value for money?

Airservices did not achieve value for money through its procurement of ICCPM. It applied no competitive pressure in the engagement processes and the records of the engagements made little or no reference to how the entity was satisfied that value for money was being obtained. Airservices also largely operated as a price-taker; obtaining quotes from ICCPM without seeking to benchmark the proposed rates to similar services obtained by other Commonwealth entities, or actively seeking to negotiate reduced rates particularly in circumstances where initial short-term engagements became extended into long-term engagements.

2.36 Applying open and effective competition in procurement processes assists entities to obtain value for money. This approach also provides suppliers with fair and equitable access to government supply opportunities.

2.37 Not one of the ICCPM contracts resulted from a competitive procurement process. Rather, on each occasion, Airservices sole sourced directly from ICCPM. Significantly, although Airservices documented the approval of each procurement valued at more than $50 000, the relevant approval memos did not state that the sole sourcing approach was at odds with a key element of its procurement framework, as follows:

- there were eight procurements between $50 000 and $300 000. Airservices’ documented procedures requires three quotes for procurements in this value range but in each instance Airservices only obtained a quote from ICCPM; and

- procurements valued at greater than $300 000 are required to have an acquisition strategy in place that addresses market research; a suite of tender documents (conditions of tender, scope of work, draft conditions of contract and tender response schedules) is to be prepared; and, as part of the ‘Approaching the Market’ stage, an evaluation plan is to be prepared before the tender documents are released to potential providers. None of these activities were undertaken for the seven ICCPM procurements valued above $300 000.23

2.38 More broadly, Airservices’ records of engaging ICCPM also made little mention of value for money considerations. Although it was common for the approval memos to set out both the expected cost of the engagement(s) covered by the particular procurement, and the total amount of estimated expenditure to date awarded to ICCPM, they did not address the basis on which it had been concluded that the cost of the procurement for the scope of work and timeframe could be considered to provide value for money. Two key aspects in that respect that should have been addressed were:

- the daily fee rates being agreed to by Airservices; and

- the terms of the sub-contracting arrangements between ICCPM and the various members of its Associate Partner Network that were to provide services to Airservices.

Fee rates

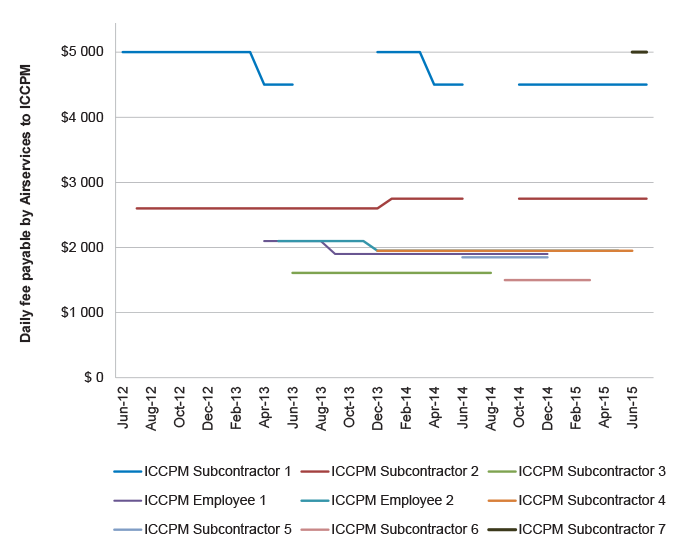

2.39 Apart from those engagements that involved the delivery of training or workshops where fixed fees to the total value of $75 090 applied, Airservices engaged ICCPM employees and subcontractors on daily rates. The daily rates agreed to be paid by Airservices for the services of individual contractors ranged from $1 500 per day up to $5 000 per day (for an eight hour day), as illustrated by Figure 2.3. These rates did not result from competitive procurement processes. In addition, rates were the same or similar for an individual engaged to provide strategic advice for a limited number of days each week for a relatively short period of time as were paid for the same individual to be engaged on a full-time, or close to full-time, basis for many months as part of tender evaluation and/or contract negotiation activities.

Figure 2.3: Daily consultancy fee rates paid by Airservices to ICCPM

Source: ANAO analysis of Airservices and ICCPM data.

Note: Some ICCPM engagements did not involve daily fees but fixed fees (for example, for delivery of a particular training course).

2.40 Five of the approval memos made reference to the negotiation of consultancy rates. But there were few records supporting that any such negotiations had been undertaken. In the absence of such records, key Airservices personnel involved in the engagements that were interviewed by the ANAO were unable to describe any steps they had taken in this respect. Rather, having decided to sole source from ICCPM, Airservices typically operated as a price-taker with only four instances across the 42 engagements where rates were reduced. This comprised:

- a $500 reduction proposed by a sub-contractor in March 2013 as a volume discount (from a rate of $5 000 per day that had been paid by Airservices up to that point) for a 25 to 35 day engagement undertaking a review of the RFT prior to it being issued. The rate returned to $5 000 per day for the next engagement (which was approved in December 2013) for up to 20 days strategic advisory services on an ‘as required’ basis up until 31 December 2014;

- the $5 000 per day for this sub-contractor for review services was usurped in May 2014 when Airservices approved the engagement of HC Bradford and Associates, via ICCPM, to undertake the Lead Negotiator role for an ‘initial’ six month term of up to 104 days, with this lower rate being continued throughout the contract negotiation role. The daily rate to be charged returned to the $4 500 rate previously agreed as a volume discount for a 25 to 35 day engagement;24

- a $200 reduction in the daily rate for an ICCPM employee contracted for executive services, from $2 100 to $1 900; and

- a $150 reduction in the daily rate for an ICCPM employee contracted initially for executive services at a daily rate of $2 100 and later for a Chief of Staff role at a rate of $1 950 per day.

2.41 In one instance, the daily rate of an ICCPM subcontractor was increased from $2 600 for strategic advisory services to $2 750 for work described in similar terms as well as a later (long-term) contract negotiation role. The approval memoranda for these procurements did not note the increase in the rate or mention any negotiations with regards to this increased rate.

2.42 With one exception25, Airservices also did not seek to benchmark the rates to those paid for similar services by other Commonwealth entities so as to be assured that it was obtaining value for money.

2.43 For example, Airservices was aware that the previous negotiation role undertaken for the Commonwealth by HC Bradford and Associates through ICCPM was for Defence. That was under a contract signed in July 2013 for the Helicopter Aircrew Training System (HATS) for Army and Navy. While Airservices saw the HATS engagement as relevant in making the decision that HC Bradford and Associates would be capable of undertaking the OneSKY Lead Negotiator role, it did not obtain reliable information from Defence as to the rate paid by Defence.26

2.44 Information obtained by the ANAO from Defence was that the lead negotiator contract for the HATS project was capped at $400 000 for fees and expenses for up to 100 days of consultancy services over a term of up to fourteen and a half months (from mid July 2013 to 30 September 2014). The daily rate contracted and paid by Defence to ICCPM for negotiation services from HC Bradford and Associates was $3 454.55.

2.45 Through three consecutive engagements27 Airservices engaged HC Bradford and Associates via ICCPM for up to 536 days of lead negotiation services over a 26 month term commencing on 1 April 2014 with a total contract value of $2.41 million. The arrangements for reimbursement of travel and other expenses under the Airservices and Defence contracts were similar (reimbursement of expenses at SES rates, and time spent travelling reimbursable at 50 per cent of the daily consulting rate), although Defence capped the total contract cost whereas Airservices did not.28

2.46 The daily rate paid by Airservices for lead negotiation services was $4 500. This was 30 per cent higher than the rate paid by Defence for similar services. Over the term of the Airservices engagements, this meant that Airservices agreed to pay consultancy fees $560 361 higher than had it contracted at the same rate Defence had agreed with ICCPM for lead negotiation services from HC Bradford and Associates (during overlapping periods of time).

2.47 The daily rate of $4 500 had been proposed to Airservices by the sub-contractor in March 2013 as a volume discount (from a rate of $5 000 per day that had been paid by Airservices up to that point) for a 25 to 35 day engagement undertaking a review of the RFT prior to it being issued. It returned to $5 000 per day for the next engagement (which was approved in December 2013) for up to 20 days strategic advisory services on an ‘as required’ basis up until 31 December 2014. This was usurped in May 2014 when Airservices approved the engagement of HC Bradford and Associates, via ICCPM, to undertake the Lead Negotiator role for an ‘initial’ six month term of up to 104 days. The daily rate to be charged returned to the $4 500 rate previously agreed as a volume discount for a 25 to 35 day engagement. There was no attempt by Airservices to negotiate any further reduction for the ‘initial’ Lead Negotiator engagement, or in respect to the subsequent engagements of 172 days over eight months or 260 days over twelve months. In February 2016, the sub-contractor advised the ANAO that:

I set the rates for which I am prepared to work, and as a general rule I do not negotiate these rates. My clients either accept my costs or not—it is up to them. For the most part, my rates are not a critical determinant of my engagement.

2.48 As discussed (see paragraphs 2.23 to 2.25), Airservices operated on the basis that the Lead Negotiator services were being accessed via the on-call services schedule to its existing contract with ICCPM. Airservices did not seek to establish any framework of specified deliverables against which the Lead Negotiator’s performance would be assessed. Nor did the contractual arrangements establish any financial incentives in respect to the successful conclusion of negotiations within specified timeframes.

2.49 When the Lead Negotiator ceased providing those services in November 2015, Airservices engaged the Deputy Lead Negotiator (directly from Keyholder Pty Ltd, who had until that time been engaged on a sub-contractor basis through ICCPM to perform the Deputy Lead Negotiator role) to take on that role. That arrangement coincided with implementation by Airservices of a recommendation from the Allens review that, to avoid conflict of interest perceptions, the Lead and Deputy Lead Negotiators be contracted directly, rather than via ICCPM.29 The fee now payable under the direct contract with Keyholder Pty Ltd for the Lead Negotiator services was $3 500 per day. This was the rate put forward by the contractor without any negotiation by Airservices. Further, while Airservices obtained information from Defence on rates for various types of consultants on the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Support Services panel30, this data was not referenced in the approval record for the engagement of a new Lead Negotiator. Rather, Airservices limited itself to comparing the rate it was agreeing to pay for Keyholder to provide the Lead Negotiator services with the rate it had agreed to pay ICCPM for a sub-contractor (HC Bradford and Associates) to provide those services.

2.50 The $3 500 per day rate contracted to be paid direct to Keyholder was a significant reduction on the rate that had previously been paid by Airservices to ICCPM for a sub-contractor to provide those services. But, on a like-for-like basis, this rate was not substantially different to the underlying commercial arrangements that had previously applied between ICCPM and HC Bradford and Associates. Specifically HC Bradford and Associates had been sub-contracted to Airservices through ICCPM, with ICCPM retaining $900 (20 per cent) of the daily fee and passing the remaining $3 600 per day onto the sub-contractor.

Fees retained by ICCPM

2.51 As outlined at paragraph 2.10, in 2011 ICCPM established a ‘professional solutions’ stream as an alternate revenue generation strategy. For its Associate Partner Network, this involves ICCPM retaining a proportion of the consulting fees paid by a client. For each of the 18 procurements, in addition to not negotiating on the daily fee rate that was payable, Airservices did not seek to inform itself as to the proportion of the fee that was to be retained by ICCPM; seek to negotiate with ICCPM on that proportion (including in circumstances where the engagements were to be long-term of six months or more); or consider whether the same services could be obtained by contracting directly with particular sub-contractor.

2.52 In this respect, the Allens review:

- opined that ICCPM performs ‘a bare administrative role’; and

- as noted, recommended that Airservices contract directly rather than through ICCPM.

2.53 There were three engagements with a total contract value of $79 200 where ICCPM did not retain a proportion of the fee paid by Airservices. For the remaining procurements, ICCPM retained between 13 per cent and 26 per cent of the fee where the services were sub-contracted rather than being delivered by an ICCPM employee. This amounted to total potential fee revenue of $1.56 million to be retained by ICCPM, or 19.7 per cent of the total fees contracted to be paid by Airservices. In his testimony to the ANAO, Mr Bradford stated that his approach involved:

Directing, where the opportunity presented itself, work to my company through ICCPM because that was beneficial to ICCPM. It’s not a cash rich organisation and any work I could bring into ICCPM was helpful for their financial position.

Recommendation No.2

2.54 The ANAO recommends that Airservices Australia improve the value for money it obtains from major and strategic procurement activities by:

- requiring that, except in genuinely rare circumstances, competitive procurement processes are to be employed; and

- on those rare occasions when competitive procurement processes have not been able to be employed:

- documenting the reasons why a competitive approach was not employed;

- benchmarking the quoted rates/fee and making records of the basis on which it was decided that the contracted rate/fee represented value for money; and

- reporting any such instances to the Airservices Australia Board.

Airservices Australia response: Agreed.

3. Airservices’ probity management framework

Areas examined

ANAO examined whether Airservices has appropriate policies and procedures in place for the management of probity, including conflicts of interest, in undertaking procurements generally and for the CMATS joint procurement in particular.

Conclusion

Airservices’ documented procurement framework requires that probity be a key consideration in undertaking procurement processes. This includes requirements to effectively identify and manage potential, actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

The Probity Plan and Protocols established for the CMATS joint procurement process, together with the engagement of an external Probity Advisor as well as an external Probity Auditor, provided a reasonable basis for managing the probity aspects of the tender process. But Airservices did not commission independent probity audits of any phase of the tender process subsequent to the release of the RFT.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation that Airservices’ procurement framework better address the use of probity auditors and probity advisors.

Has Airservices established appropriate procedures for managing probity in procurement decisions?

Airservices’ documented procurement framework requires that probity be a key consideration in undertaking procurement processes, including the need to effectively identify and manage conflicts of interest, whether potential, actual or perceived.

3.1 Airservices’ suite of policies and procedures emphasise that probity31 and ethics are key to undertaking procurement activities, and integral to achieving value-for-money outcomes. Probity is identified as including the management of conflicts of interest, whether actual or perceived. Procurement governance is similarly identified as important, including for ensuring that each activity is undertaken with high standards of transparency, probity and integrity.

3.2 Airservices has also promulgated a Code of Conduct and associated Management Instruction, which set out the standard of conduct required of all Airservices employees, contractors and consultants. The Code includes a requirement that individuals must immediately disclose in writing (and preferably avoid) any actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest as soon as it arises in connection with their engagement with Airservices. Under the Management Instruction, each Business Group or Division is required to maintain a conflict of interest register and gifts and benefits register. Following an internal risk review, the requirement for conflict registers to be maintained was reinforced to Airservices managers in September 2015.

Was an appropriate probity management framework established for the CMATS joint procurement?

Two internal audits of governance within Airservices’ Future Service Delivery (FSD) group (which incorporates the OneSKY program) have been undertaken, reporting in April 2014 and August 2015. Whilst the scope of the first report included some consideration of the probity records management associated with the Probity Plan for the CMATS tender, neither involved an examination of the conduct of the tender evaluation or contract negotiation processes from a probity perspective.

In conjunction with the engagement of an external Probity Advisor, the Probity Plan and Protocols established for the CMATS joint procurement process provided a reasonable basis for managing the probity aspects of the tender process. An area for improvement related to the approach taken to identifying the role of a probity auditor, and documenting the rationale for not commissioning independent probity audits of any phase of the tender process subsequent to the release of the RFT.

Probity Plan and Protocols and external Probity Advisor

3.3 The legal firm Ashurst Australia32 (Ashurst) was first engaged by Airservices to act as external Probity Advisor to the process for procuring a future air traffic management system in February 2010. Ashurst was selected from a legal services provider panel established by Airservices.33 A Probity Plan and Probity Protocols for the (then) AFS program, prepared in conjunction with Ashurst, were endorsed in April 2010. That plan applied to Airservices participants only during the process of developing, with Defence, a joint Request for Information (RFI) for a future civil-military ATM platform. The RFI was released to industry in May 2010, with the responses received being used as a basis for developing a business case and options for progressing the ATM replacement processes for Airservices and Defence.

3.4 Following confirmation that the subsequent approach to market would be based upon the provision of a harmonised civil and military ATM solution, a Joint Probity Plan and associated Protocols were promulgated in December 2011. Under that Plan, Ashurst became the Probity Advisor to both Airservices and Defence. Program Directors in Airservices and Defence were jointly responsible for administering compliance with the Probity Plan and Protocols.

3.5 The Probity Plan and Protocols were updated in April 2013, including to reflect the agreement that Airservices would be the lead agency for the joint procurement. The position of Manager Acquisition within Airservices became solely responsible for overall management of the Probity Plan and Protocols.34 Minor further updates were made in a further version of the Plan promulgated in September 2013.35

3.6 The stated objectives of the Probity Plan, and attached Protocols are to:

- identify probity issues relevant to the program;

- determine the most appropriate controls to deal with the identified probity issues;

- publish, and make Program Participants aware of, the potential probity issues and their responsibilities; and

- ensure that Airservices and Defence adopt and implement a process which will sustain any internal or external scrutiny of the program.

3.7 The role of the Probity Advisor, as set out in the Probity Plan, is to independently monitor procedural aspects to ensure compliance with program documentation and governance documents and to advise Airservices and Defence in relation to such matters. Ashurst has provided signoffs in relation to each phase of the tender evaluation completed to date.

3.8 The Manager Acquisition is responsible for taking reasonable steps to ensure that the program is at all times conducted in a manner that is consistent with the Probity Plan and Protocols and any other approved program plans. The Manager Acquisition is responsible for nominating as Program Participants those persons who either require access to commercial-in-confidence information, or need to deal with a person who could affect the probity of the program.

3.9 The Probity Plan and Protocols set out a range of obligations on Program Participants relating to maintaining confidentiality. There are also obligations for the on-going declaration of existing or potential conflicts of interest, whether actual or perceived, including proposals for managing each conflict. Upon being nominated as a Program Participant, individuals are required to receive a probity briefing to assist them in understanding their obligations. The Protocols apply until a Program Participant is informed by the Manager Acquisition that they no longer apply. The Protocols also stipulate that the specified confidentiality obligations apply indefinitely, unless advised by the Manager Acquisition that the information is no longer confidential.36

Tender Evaluation Plan and Contract Negotiation Strategy

3.10 The Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) established for the joint procurement articulated the probity obligations applying to members of the Tender Evaluation Organisation (TEO), which consisted of the various governance structures and teams responsible for evaluating tenders and making procurement decisions. Those obligations reiterated the requirement to observe the Probity Plan and Protocols, as well as articulating specific procedures for the disclosure and management of conflicts of interest that arose during the tender evaluation process.

3.11 The TEO structure included a Procurement Governance Advisor. That position was responsible for monitoring procedural aspects of the evaluation process to ensure compliance with the published documentation (including the TEP and Probity Plan and Protocols) and to advise relevant TEO members in relation to such matters. The TEP provided that the Probity Advisor may be consulted by the TEO, through the Procurement Governance Advisor, if there were any probity issues or as otherwise required in relation to the evaluation or the TEP.