Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement and Contract Management by Tourism Australia

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Payments to suppliers represented 74 per cent of Tourism Australia’s (TA) total expenses in 2023–24, and 73 per cent of its total budgeted expenses for 2024–25.

- This audit provides assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of TA’s procurement and contract management activities.

Key facts

- TA is a corporate Commonwealth entity that is subject to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

- As at 30 June 2024, TA had reported 55 contracts on AusTender with a start date falling between 2021–22 and 2023–24, valued at $265.6 million.

What did we find?

- TA’s procurement and contract management activities are not effective in complying with the CPRs and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

- TA’s procurement processes have not demonstrated the achievement of value for money.

- TA has not effectively managed contracts to achieve the objectives of the procurement.

What did we recommend?

- There were nine recommendations to TA aimed at improving its procurement processes and strengthening its contract management.

- TA agreed to all nine recommendations.

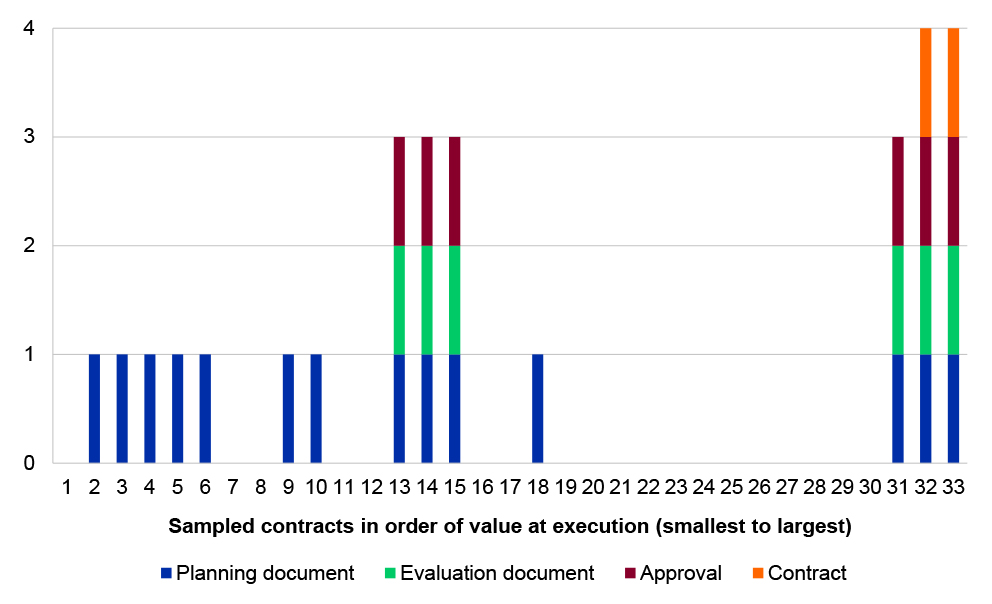

74%

of expenses in 2023–24 related to payments to suppliers.

70%

of procurements examined by the ANAO did not involve open competition.

Nil

contracts (of the 33 examined) had a contract management plan in place.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Tourism Australia (TA) was established in 2004 under the Tourism Australia Act 2004 (TA Act). Its corporate plan states that its purpose is to ‘grow demand to enable a competitive and sustainable Australian tourism industry’.1 The accountable authority for TA is the Board of Directors. TA reports having around 220 staff.

2. TA is a corporate Commonwealth entity within the Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio. It is subject to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) issued by the Minister for Finance under section 105B of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

3. According to its audited financial statements, payments to suppliers represented 74 per cent of TA’s total expenses in 2023–24. Of its total budgeted expenses for 2024–25, 73 per cent were attributable to supplier expenses. As at 30 June 2024, TA had reported 55 contracts on AusTender with a start date falling within the last three financial years, valued at $265.6 million (including contract amendments).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Noting that nearly three-quarters of organisational expenses relate to contracting suppliers, this audit provides assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of TA’s procurement and contract management activities.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess whether TA’s procurement and contract management activities are complying with the CPRs and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied:

- Do the procurement processes demonstrate the achievement of value for money?

- Are the contracts being managed appropriately to achieve the objectives of the procurement?

Conclusion

7. TA’s procurement and contract management activities are not effective in complying with the CPRs and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

8. TA’s procurement processes have not demonstrated the achievement of value for money. TA makes insufficient use of open and competitive procurement processes, with 70 per cent of the 33 procurements examined in detail by the ANAO not involving open competition. An appropriate procurement policy framework is not in place and TA’s conduct of procurement activities regularly fails to adhere to requirements under the CPRs such as:

- including evaluation criteria in request documentation and using those criteria to select the candidate that represents the best value for money;

- acting ethically including fair treatment of suppliers and through the declaration and management of any conflicts of interest2; and

- maintaining appropriate records commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

9. TA has not effectively managed contracts to achieve the objectives of the procurement. In relation to the 33 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO:

- none had a contract management plan, including some high-risk and high-value arrangements;

- for more than half (55 per cent), TA had not included clear performance requirements in the contract. There were also shortcomings in TA’s monitoring of contractor performance across the sample examined by the ANAO;

- contract variations are common, with 33 per cent of contracts examined by the ANAO being varied. None of the variations had records created and retained by TA that demonstrated that the variation represented value for money; and

- invoicing and payments for 64 per cent did not adhere to the contracts and/or requirements under TA’s policies.

10. TA has also not been meeting its AusTender reporting requirements.

Supporting findings

Procurement processes

11. An appropriate procurement policy framework is not in place. The two versions of the Procurement Policy in place for the period covered by this ANAO performance audit do not fully reflect, or address, the principles, prescriptive requirements and mandatory rules set out in the CPRs. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.19)

12. Based on TA’s AusTender reporting, the majority (62 per cent) of procurements valued at or above the $400,000 threshold set by the CPRs did not involve open approaches to the market. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.39)

13. A competitive procurement approach was evident in the establishment of 55 per cent of the contracts examined by the ANAO. For 36 per cent of the contracts, a non-competitive approach was taken and in nine per cent there were insufficient records maintained to evidence the procurement approach taken by TA. For 10 of the procurements (30 per cent) examined by the ANAO, it was evident from the evaluation records that TA had favoured existing or previous suppliers when evaluating competing offers through panel procurement or when deciding which potential provider(s) should be invited to participate in a limited tender. Favouring existing or previous suppliers in the conduct of procurement processes is inconsistent with the CPRs. (See paragraphs 2.40 to 2.63)

14. Relevant evaluation criteria were included in request documentation for 52 per cent of the contracts examined in detail by the ANAO. For the remaining 48 per cent, either the request documentation did not include any evaluation criteria (12 per cent) or there were no records of the request documentation on file (36 per cent). This situation is not consistent with the CPRs which require evaluation criteria to be included in the request documentation. (See paragraphs 2.67 to 2.69)

15. Just over half of the contracts examined by the ANAO were awarded to the candidate where records demonstrated that it had been assessed by TA to offer the best value for money. For the remaining 48 per cent of contracts where value for money outcomes had not been demonstrated, this was primarily the result of insufficient analysis being presented commensurate with the scale of the procurement, or insufficient documentation being maintained. (See paragraphs 2.72 to 2.83)

16. TA had not conducted procurements to a consistent ethical standard as required under the CPRs. Of note was that:

- conflict of interest declarations were not completed by all evaluation team members in four per cent of the contracts examined where there was sufficient documentation on file;

- for eight per cent of the contracts where advisers were appointed to assist with the procurement process, TA’s records did not include a complete list of the individuals involved; and

- the procurements of external probity advisers were deficient in relation to how those advisers were engaged as well as the limited scope of probity services obtained by TA. (See paragraphs 2.86 to 2.110)

17. TA did not maintain appropriate records commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement (which is what the CPRs require). Forty-eight per cent of contracts examined by the ANAO were missing one or more important documents. In addition, for those contracts where adequate records were available, more than half of the contracts involved work commencing before a contract was in place. (See paragraphs 2.113 to 2.132)

Contract management

18. TA’s reporting of contracts on AusTender was not compliant with the CPRs. TA accurately reported 19 per cent of the relevant contracts examined in detail by the ANAO within the required timeframe. Key information on contract values and contract start and end dates have been reported inaccurately with contract amendments usually not reported at all. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.17)

19. An appropriate contract management framework is not in place. None of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO had a contract management plan and none had a risk management plan. This included a five-year $311.3 million contract that relates to a key element of TA’s marketing efforts. (See paragraphs 3.18 to 3.32)

20. Less than half (45 per cent) of the contracts examined by the ANAO included clear performance requirements. Methods for monitoring performance were included for 79 per cent of contracts examined, including a number of contracts where performance requirements had not been specified (that is the monitoring arrangements, such as reporting and/or progress meetings, were not against a clear performance requirement). Further, TA has not consistently adhered to the performance framework set out in the contracts and it was common for there to be gaps in the records to evidence the contract management activities undertaken that TA was paying for. (See paragraphs 3.33 to 3.40)

21. For the procurements examined by the ANAO, TA has not consistently managed contracts effectively to deliver against the objectives of the procurements and to achieve value for money.

- Of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, 11 (33 per cent) had records of at least one variation being executed. None of the variations had supporting evidence of records to the delegate documenting the decision-making process and demonstrating that the variation represented value for money. Some variations have significantly increased the value of the contract (by up to 105 per cent) and retrospectively added additional services already delivered and/or paid for. There have also been instances of contracts continuing to operate past their stated completion date without being varied.

- Invoicing and payments under 21 of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO did not adhere to the contracts and/or requirements under TA’s policies. This has included instances of full payments being made before final deliverables under the contract are received and payments exceeding the contracted amount. (See paragraphs 3.41 to 3.51)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.20

Tourism Australia document a comprehensive procurement policy framework that gives full effect to the principles, prescriptive requirements and mandatory rules set out in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.64

Tourism Australia increase the extent to which it employs open, fair, non-discriminatory and competitive procurement processes.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.70

Tourism Australia strengthen its procurement controls to ensure that procurement request documentation includes:

- the evaluation criteria that will be applied, together with any weightings; and

- the way that prices will be considered in assessing the value for money offered by each candidate.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.84

Tourism Australia strengthen its procurement practices so that it can demonstrate that contracts are awarded to the candidate that satisfies the conditions for participation, is fully capable of undertaking the contract and will provide the best value for money as assessed against the essential requirements and evaluation criteria specified in the approach to market and request documentation.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 2.111

Tourism Australia engage probity advisers through transparent procurement processes and, where a probity adviser has been appointed, Tourism Australia actively engage and manage the adviser to ensure probity has been maintained during the procurement process.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 2.128

Tourism Australia improve its record keeping processes to ensure that business information and records are accurate, fit for purpose and are appropriately stored within entity systems.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 2.133

Tourism Australia strengthen its procurement controls to better address the risk of work commencing before a contract is in place.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.14

Tourism Australia:

- place greater emphasis on timely and accurate reporting of its procurement activities; and

- implement a monitoring and assurance framework over its compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules including for AusTender reporting.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 3.52

Tourism Australia strengthen its contract management including by:

- establishing and maintaining a contract register that contains details of all entity contracts, and implementing a quality assurance process to ensure that the information recorded is complete and accurate, and updated in a timely manner;

- documenting risk management and contract management plans for high-risk, high-value contracts;

- including clear performance requirements in contracts and applying contracted performance monitoring approaches in the management of contracts; and

- introducing effective controls over invoicing and payments under contracts.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

22. The proposed audit report was provided to TA. The letter of response that was received for inclusion in the audit report is at Appendix 1. TA’s summary response is provided below.

Tourism Australia acknowledges the ANAO’s report and is fully committed to implementing its nine recommendations to improve the agency’s procurement and contract management practices.

Tourism Australia had already begun to make improvements to its procurement and contract management systems ahead of the audit, and the agency is in the process of implementing remedial actions relating to the recommendations. This includes enhancing the agency’s records management framework and processes, implementing a new procurement and contract management system and adding resources to its corporate services teams. Additional training will also be provided to all staff to improve capability to ensure that decisions are compliant, defensible, and clearly demonstrate value for money.

Some of the report’s findings relate to work undertaken during the unprecedented events of the Covid-19 pandemic, when Tourism Australia’s primary focus was on the emergency response to support an industry in crisis. Nevertheless, Tourism Australia accepts the recommendations for improvement to ensure that it can better demonstrate that the agency’s procurement and contract management activities comply with Commonwealth Procurement Rules and achieve value for money.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Competitive processes

Procurement

Contract management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Tourism Australia (TA) was established in 2004 under the Tourism Australia Act 2004 (TA Act).3 Its corporate plan states that its purpose is to ‘grow demand to enable a competitive and sustainable Australian tourism industry’.4 The accountable authority for TA is the Board of Directors.5 TA reports having around 220 staff.6

1.2 TA is a corporate Commonwealth entity within the Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio. It is subject to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules issued by the Minister for Finance under section 105B of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.7

Procurement activities

1.3 According to its audited financial statements, payments to suppliers represented 74 per cent of TA’s total expenses in 2023–24. Of its total budgeted expenses for 2024–25, 73 per cent were attributable to supplier expenses.

1.4 As at 30 June 2024, TA had reported 55 contracts on AusTender with a start date falling within the last three financial years, valued at $265.6 million (including contract amendments). Recently completed procurements have included:

- a seven-year, $20 million contract to lease office space in Sydney;

- a three-year, $186.8 million contract for global media services;

- a three-year, $2.4 million contract for translation and transcreation services; and

- a three-year, $2.3 million contract for public relations services in North America.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.5 Noting that nearly three-quarters of organisational expenses relate to contracting suppliers, this audit provides assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of TA’s procurement and contract management activities.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.6 The audit objective was to assess whether TA’s procurement and contract management activities are complying with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and demonstrating the achievement of value for money.

1.7 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied:

- Do the procurement processes demonstrate the achievement of value for money?

- Are the contracts being managed appropriately to achieve the objectives of the procurement?

1.8 The audit scope encompassed TA’s:

- procurement and contract management framework; and

- procurement and contract management activities for contracts entered into in 2021–22 and 2022–23.

Audit methodology

1.9 The audit method involved:

- examination of TA records (including electronic documentation, and procurement and contract management reports) and AusTender reporting;

- targeted testing of a selection of individual procurements to provide coverage across the different procurement approaches employed by TA.8 In addition to examining records held by TA in the files for each procurement, in response to the preliminary audit findings in a number of instances TA identified and provided to the ANAO relevant procurement records that should have been included in the file for the procurement. This enabled the ANAO to update its analysis before finalising the report of this audit; and

- meetings with relevant staff.

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $548,000.

1.11 The team members for this audit were Tiffany Tang, Tomislav Kesina, Sharini Arulkumaran and Brian Boyd.

2. Procurement processes

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the procurement processes demonstrated the achievement of value for money.

Conclusion

Tourism Australia’s (TA) procurement processes have not demonstrated the achievement of value for money. TA makes insufficient use of open and competitive procurement processes, with 70 per cent of the 33 procurements examined in detail by the ANAO not involving open competition. An appropriate procurement policy framework is not in place and TA’s conduct of procurement activities regularly fails to adhere to requirements under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) such as:

- including evaluation criteria in request documentation and using those criteria to select the candidate that represents the best value for money;

- acting ethically including fair treatment of suppliers and through the declaration and management of any conflicts of interest; and

- maintaining appropriate records commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made seven recommendations with a particular focus on TA obtaining value for money in its procurement activities, including through greater use of open and effective competition to transparently select suppliers based on a documented assessment against evaluation criteria that are included in an approach to market, more consistent adherence to ethical requirements and improved procurement record keeping.

2.1 To assess whether the procurement processes demonstrated the achievement of value for money, the ANAO examined whether an open and competitive procurement process was conducted in compliance with the CPRs. This reflects that competition is a key element of the Australian Government’s procurement framework.

Is there an appropriate procurement policy framework in place?

An appropriate procurement policy framework is not in place. The two versions of the Procurement Policy in place for the period covered by this ANAO performance audit do not fully reflect, or address, the principles, prescriptive requirements and mandatory rules set out in the CPRs.

2.2 A sound framework helps ensure that: procurements are undertaken in compliance with relevant rules and legislation; entities properly use and manage public resources; and procurements achieve value for money outcomes. The key procurement policy framework document for TA is its ‘Procurement Policy’. The Procurement Policy sets out TA’s requirements for ‘planning, implementing, approving and documenting procurements’.

2.3 For the period examined by the ANAO (contracts entered into in 2021–22 and 2022–23), TA had two versions of this policy in place. The current version, approved in December 2022 (the 10th version overall for TA), replaced a June 2021 version.9

2.4 Both versions of the Procurement Policy in place for the contracting period examined by the ANAO emphasised the importance of value for money and competition, for example:

Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs and of this policy. Staff responsible for procurements must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome for Tourism Australia. Procurements should:

- encourage competition and be non-discriminatory

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision-making

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk

- be commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.

2.5 Each version of the policy identified monetary thresholds so as to require that higher value procurements would involve greater levels of competition for what TA describes as ‘standard procurements’, which is defined in the policy as ‘where Tourism Australia alone is purchasing goods or services and committing money.’ TA also enters into ‘Partnership Marketing Agreements (PMAs)’, ‘Sponsorship Agreements’ and ‘Cooperative Broadcast Agreements’ which the policy describes as involving ‘a third party, typically in a joint marketing effort with Tourism Australia’. The Procurement Policy requires that:

PMAs must be developed and implemented in line with the Partnership Strategy and Guidelines10, as updated from time to time. Sponsorship Agreements and Cooperative Broadcast Agreements must be discussed with the Procurement and Legal teams to determine the most appropriate procurement approach.

2.6 In March 2020, TA obtained legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor that it was reasonable for it to proceed on the basis that entry into a PMA does not involve a procurement for the purposes of the CPRs, on the basis that the agreement is not concerned with the acquisition of goods or services from the partner, provided that:

- the underlying purpose of the arrangement is to engage in joint marketing activities (not to acquire something from the partner); and

- any goods provided by the partner are merely incidental to the arrangement (e.g. the goods provided are not of significant value/the only contribution made by the partner towards the joint marketing activity).

2.7 TA’s Procurement Policy has not been drafted to reflect that there may be circumstances where a PMA does involve a procurement.11 For example, in June 2023 TA entered into an agreement with JTB Corp. that required TA to provide Japanese yen (¥) 10,300,000 with JTB Corp. required to use that money as well as its own contribution12 to purchase specific goods and services in which TA and JTB Corp. would jointly own and control the intellectual property. This agreement was not treated as a procurement even though TA acquired intellectual property.

Opportunity for improvement

2.8 Tourism Australia could expand the guidance in its Procurement Policy to identify the circumstances in which a Partnership Marketing Agreement involves a procurement.

Open and effective competition

2.9 The CPRs state that procurements should ‘encourage competition and be non-discriminatory’.13 TA’s Procurement Policy provides limited support for the adoption of competitive procurement processes.

2.10 The monetary thresholds identified for ‘standard procurements of goods and services’ suggest that higher value procurements should have greater competition. There are various caveats and exceptions that undermine the adoption of competition. For example, procurements valued at $25,000 or more and less than $400,000 are ‘generally’ expected to involve ‘multiple quotes’ with proposed exceptions to be discussed and agreed with TA’s procurement team. As part of the audit, the ANAO asked TA to identify to the ANAO any procurements in this value range since 23 December 2022 where the procurement team did not agree to a proposal that multiple quotes not be obtained. No instances were identified to the ANAO by TA.

2.11 As set out in Table 2.2 on page 29, there was no competition for 12 (40 per cent) of the 30 TA procurements examined in detail by the ANAO where records were available.14 Eight of those 12 procurements involved values in the range of $103,156 to $394,680.

2.12 TA’s Procurement Policy states that ‘Publishing an open tender on AusTender is the default approach’ for contracts valued at or above $400,000. Under the CPRs, open tender is the default method for procurements of non-construction services valued at or above $400,000 (or $7.5 million for construction services) for prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the CPRs, such as TA. When the expected value of a procurement is at or above the relevant procurement threshold, and is not specifically exempt in accordance with Appendix A of the CPRs, then the rules in Division 2 must be followed. Division 2 requires an open tender unless the specified conditions for limited tender apply.

2.13 TA’s Procurement Policy does not distinguish between procurements of non-construction and construction services.15

2.14 There were 10 contracts in the audit sample with a value at the time of signature greater than $400,000 (59 per cent of the 17 contracts with a value above the $400,000 threshold when the contract was first signed and where records were available) where the procurement approach was an open tender. On each occasion, the contract was let following an approach to market being published on AusTender.

2.15 The four other non-competitive procurements in the sample examined by the ANAO involved values greater than the relevant threshold set out in TA’s Procurement Policy.16 For two of those four procurements, TA made a record of why it was not conducting an open tender. For the other two of those four procurements, no procurement planning documents were prepared and filed by TA in its record keeping system. There was also no request documentation on file, no evaluation report documenting how the procurement had been assessed to represent value for money, and no approval records for the procurement outcome.

- The first was an August 2021 contract for $440,000 with Zoe 8 Holdings Pty Ltd as Trustee for ZFB to engage one individual for marketing campaigns.17

- The second was a February 2022 contract for $585,585 (later increased to $737,555) with LVDI Pty Ltd for tourism operator shoots.18

2.16 TA’s Procurement Policy is largely silent on key procedural requirements to give effect to the CPRs, either by setting them out in the document or referencing the CPRs.19 For example, the Procurement Policy does not require that:

- evaluation criteria be included in request documentation to enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair, common and appropriately transparent basis (CPR 7.12). As set out at paragraphs 2.67 to 2.69, relevant evaluation criteria were demonstrably included in request documentation for just over half (52 per cent) of the contracts examined in detail by the ANAO20;

- suppliers be treated equitably, notwithstanding that this is required by the CPRs (CPR 5.4). For 10 of the procurements (30 per cent) examined by the ANAO, it was evident from the evaluation records that TA had favoured existing or previous suppliers when evaluating competing offers through panel procurement or when deciding which potential provider(s) should be invited to participate in a limited tender.

2.17 Procedural requirements for the preparation of procurement plans and evaluation reports for procurements valued at greater than $100,000 were frequently not complied with (14 of the sampled procurements above this threshold had no procurement plan, and six of these procurements also had no evaluation report).21 Further, for 12 procurements (36 per cent of those examined by the ANAO) TA did not have a record of what, if any, request documentation was issued to the candidate(s).

2.18 For example, in its procurement of Quiip (Holdings) Pty Limited in 2023 for a $103,156 contract for community management services TA did not prepare a procurement plan.22 With respect to procurement planning, TA advised the ANAO in August 2024 that ‘Advice was given from TA’s procurement team on the procurement process to the Business Unit.’ This advice from TA’s procurement team was provided after TA had already approached Quiip, and TA’s procurement team did not raise the lack of a procurement plan with the business unit. Further, there was no probity adviser for the procurement due to its value being below TA’s $400,000 threshold.23 TA recorded in the evaluation report for the procurement that it approached Quiip ‘on the basis of its reputation in the market’24 and also recorded that, while the hourly rate proposed was ‘higher than both the existing agency and the average freelance rate’, the ‘added value of Quiip’s proposal was worth the additional cost.’25

2.19 Non-compliance with the requirement for procurement plans to be prepared was also raised in the ANAO’s 2008–09 performance audit of TA. Specifically, that audit concluded that, for two of the three major procurements examined, procurement plans were not developed (although they were required by TA’s policies).26 The findings of this current performance audit indicate that TA has taken inadequate steps to address this earlier audit finding.

Recommendation no.1

2.20 Tourism Australia document a comprehensive procurement policy framework that gives full effect to the principles, prescriptive requirements and mandatory rules set out in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

2.21 Tourism Australia has a procurement framework in place, comprising a principles-based Procurement Policy, Delegations Instrument, Code of Conduct, and Contract Management Guidance, supported by supplementary training decks, procedures and processes documents and standard templates. Tourism Australia will enhance this framework to incorporate appropriate best practice guidance.

ANAO comment

2.22 The recommendation relates to the audit findings set out at paragraphs 2.2 to 2.19.

To what extent are open approaches used?

Based on TA’s AusTender reporting, the majority (62 per cent) of procurements valued at or above the $400,000 threshold set by the CPRs did not involve open approaches to the market.

2.23 Openness in procurement involves giving suppliers fair and equitable access to opportunities to compete for work while maintaining transparency and integrity of process. Under the CPRs, procurement is conducted by open tender or by limited tender.

- An open tender involves the entity publishing an open approach to market and inviting submissions.27 An open approach to market is any notice inviting all potential suppliers to participate in a procurement.28

- A limited tender involves the entity approaching one or more potential suppliers to make submissions, when the process does not meet the rules for open tender.

2.24 Under the CPRs, the expected value of a procurement must be estimated before a decision on the procurement method is made.29 When the expected value of a procurement is at or above the relevant ‘procurement threshold’, additional rules in the CPRs must also be followed unless an exemption applies.30 Primarily, those additional rules require that, except under specific circumstances, procurements valued at or above the relevant threshold must be conducted by an open approach to market.31 For prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities, the threshold is $400,000 for procurements of non-construction services and $7.5 million for procurements of construction services.32

2.25 Limited tenders, although permitted, may not be appropriate for procurements under the relevant threshold. The CPRs specify that the scope, scale, level of risk and market conditions must be considered to determine an appropriately competitive procurement process that will achieve value for money.

Proportion of contracts let by open tender

2.26 As at 30 June 2024, TA had reported 45 contracts on AusTender valued at $260.7 million (excluding contract amendments) with a start date between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2023.33 Of those 45 contracts:

- 38 per cent by number or 80 per cent by value were reported as being let through open tender34; and

- 62 per cent by number or 20 per cent by value were reported as being let through limited tender.

2.27 The difference between TA’s contract number data and its contract value data is influenced by the largest value contract accounting for 72 per cent of the total value of its procurements.

2.28 As an indicator of whether the proportion of contracts let by open tender was relatively high or low, the ANAO compared TA’s data against that reported by other prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities (given they are also subject to the CPRs and to the same procurement thresholds).35 To increase the suitability of the comparator, the ANAO used the data reported for contracts valued at $400,000 or above in its analysis because the CPRs do not mandate (subject to exceptions and exemptions listed in the CPRs) the use of open tenders for procurements below $400,000.

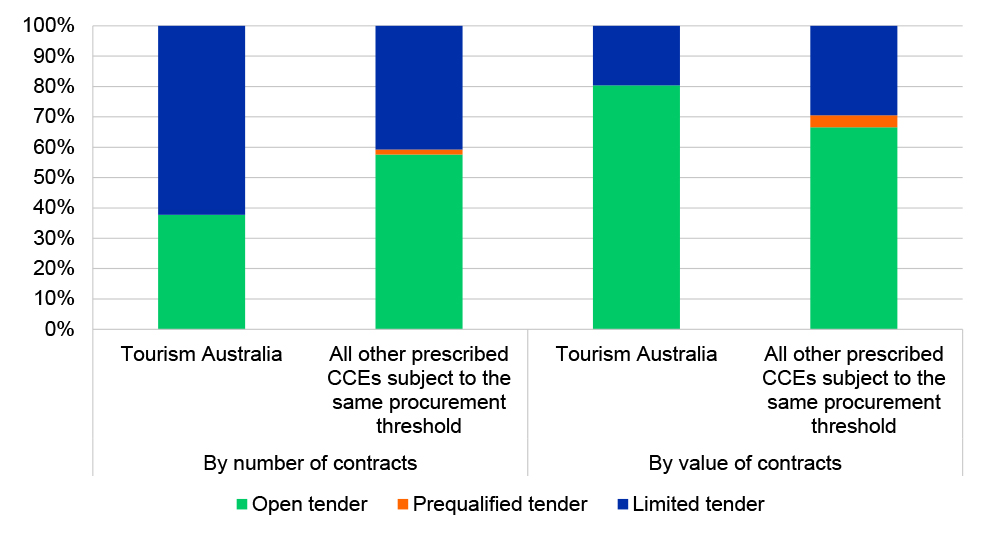

2.29 As shown in Figure 2.1, the proportion of contracts valued at or above $400,000 reported by TA on AusTender as being let through open tender (38 per cent) is smaller by number than that reported by all other applicable prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities (58 per cent). Whereas the proportion of open tenders reported by TA is relatively high by value (80 per cent compared to 67 per cent).

Figure 2.1: Contracts let by procurement method as reported on AusTender with a start date between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2023 valued at or above the $400,000 threshold

Note: The data presented is as reported on AusTender. The ANAO did not examine the accuracy of the information reported except for those procurements examined in detail as part of the audit sample (see further detail on the audit sample at paragraph 1.9).

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data.

Selecting the procurement method in sampled contracts

2.30 The CPRs state that a thorough consideration of value for money begins by officials clearly understanding and expressing the goals and purpose of the procurement. For 14 (42 per cent) of the 33 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO, there were no procurement planning documents maintained on file to evidence that the expected procurement value was estimated before a decision on the procurement method was made.

2.31 In June and July 2024, TA advised the ANAO that a procurement plan was ‘Not Required’ for six of these contracts. For three of the contracts, no further explanation was provided justifying why a procurement plan was not required in the circumstances. For the remaining three, TA advised that a procurement plan was not required on the basis that two were ‘direct engagements’ and the last was a ‘continuation of existing service’. The value of these six contracts, at contract execution, ranged from $103,156 to $1.2 million (with an average value of $348,720 and aggregate value of $2.1 million).

2.32 In August 2024, TA further advised the ANAO in relation to two of these six contracts that:

Talent / broadcasting project is covered by the exemption for government advertising services (Appendix A of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules refers), which allows a limited tender. In practice, TA would rarely approach the market for broadcast projects. Instead, opportunities are often presented by production companies and/or state and territory tourism organisations and subject to a relatively standardised evaluation approach, as detailed in the relevant evaluation report.

2.33 The ANAO’s analysis is that TA’s approach is inconsistent with the CPRs and TA’s internal policy.36 In particular, Finance guidance states that ‘Exempt procurements remain subject to other requirements of Division 1 of the CPRs, especially the core principle of value for money. Use of an exemption should be clearly documented by the decision maker, including for subsequent audit scrutiny.’ Consistent with this, TA’s Procurement Policy states that ‘The relevance and practical implications of those various exemptions [under the CPRs] should be discussed with the Procurement team and documented in a procurement plan at the start of a procurement process.’

2.34 For the remaining 19 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO where appropriate planning documents were maintained, the expected procurement value was estimated to be:

- above the relevant threshold for 15 contracts; and

- below the relevant threshold for four contracts.

2.35 As shown in Table 2.1, an open approach was taken for the majority of procurements where the estimated value was above the relevant threshold.

Table 2.1: Extent to which open approaches were used

|

|

Estimated value below threshold |

Estimated value above threshold |

|

Open approach |

||

|

Open tender |

0 |

10 |

|

Approach to a panel established by open tender |

1a |

2 |

|

Limited approach |

||

|

Limited tender |

3 |

3 |

Note a: TA identified that this was a procurement for construction services and as such, the relevant procurement threshold was $7.5 million (the estimated value was below this threshold at $6.2 million). The ‘panel’ accessed was the NSW Government’s ‘Construction Scheme for Works between $1 million and $9 million’.

Source: ANAO analysis of TA records.

Panel arrangements

2.36 A panel or standing offer arrangement is a way to procure goods or services regularly acquired by entities. In a panel arrangement, suppliers have been appointed to supply goods or services for a set period of time under agreed terms and conditions, including agreed pricing. Once a panel has been established, entities may then purchase directly from the panel. To maximise competition, entities should, where possible, approach multiple potential suppliers on the panel.37 Each purchase from a panel represents a separate procurement process, and must demonstrate the achievement of value for money and comply with the rules in Division 1 of the CPRs.

Use of procurement arrangements established by other entities

2.37 As a corporate Commonwealth entity, it is not mandatory for TA to use Whole of Australian Government Arrangements. Rather, it can choose to opt-in to specific arrangements.38 Joining such arrangements can provide benefits including: increased efficiencies in the procurement process; better prices, services and quality; increased transparency; standard terms and conditions; and improved contract management for entities and suppliers.

2.38 TA’s Procurement Policy states:

Tourism Australia can access a range of coordinated procurement arrangements, like panels, administered by other entities that are part of the Australian Government and other jurisdictions. The use of these arrangements is strongly encouraged to reduce direct costs and can streamline procurement processes, as it removes the requirement to publish an open tender. The Procurement team can assist with identifying relevant arrangements.

2.39 For three of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, TA used an existing arrangement established by other entities.

- In two instances, the procurement arrangement was established by another Commonwealth entity. Both of these panels were established by open tender with TA approaching:

- In one instance, TA accessed an existing prequalification scheme administered by the New South Wales Government and approached only one supplier on the scheme.41

To what extent are competitive approaches used?

A competitive procurement approach was evident in the establishment of 55 per cent of the contracts examined by the ANAO. For 36 per cent of the contracts, a non-competitive approach was taken and in nine per cent there were insufficient records maintained to evidence the procurement approach taken by TA. For 10 of the procurements (30 per cent) examined by the ANAO, it was evident from the evaluation records that TA had favoured existing or previous suppliers when evaluating competing offers through panel procurement or when deciding which potential provider(s) should be invited to participate in a limited tender. Favouring existing or previous suppliers in the conduct of procurement processes is inconsistent with the CPRs.

2.40 Competition is a key element of the Australian Government’s procurement framework. Effective competition requires non-discrimination and the use of competitive procurement processes. Generally, the more competitive the procurement process, the better placed an entity is to demonstrate that it has achieved value for money. Competition encourages respondents to submit more efficient, effective and economical proposals. It also ensures that the purchasing entity has access to comparative services and rates, placing it in an informed position when evaluating the responses.

2.41 As outlined in Table 2.2, TA used a competitive procurement approach to establish 18 (55 per cent) of the 33 contracts, totalling $359 million at contract execution.42 Ten were by open tender and the other eight by inviting more than one supplier to tender for the work.

Table 2.2: Contracts examined by procurement method

|

|

Number |

Value at contract execution ($ m) |

Value as at 30 Dec 2023 (inclusive of variations) ($ m) |

|

Open approach |

|||

|

Open tender conducted |

10 |

333.9 |

334.7 |

|

Competitive approach to panel let by open tender |

1 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Non-competitive approach to panel let by open tender |

2 |

6.4 |

6.7 |

|

Limited approach |

|||

|

Competitive approach |

7 |

24.3 |

24.3 |

|

Non-competitive approach |

10 |

3.6 |

4.0 |

Note: For three (nine per cent) of the 33 contracts examined in detail by the ANAO, there was insufficient information maintained to evidence the procurement approach used by TA and so these three are not included in this table.

Source: ANAO analysis of TA records.

Open tenders conducted

2.42 While open tenders (which at a minimum must be published on AusTender) mean any and all interested suppliers can view the procurement opportunity, ANAO performance audits have identified that a procurement approach that commences with an open approach to the market does not necessarily mean that the procurement process promoted effective competition.43

2.43 Relevant entities may specify conditions for participation that potential suppliers must be able to demonstrate compliance with in order to participate in a procurement.44 Care must be taken when specifying any conditions for participation, as the CPRs require entities to reject any tenders that do not meet those conditions for participation.

2.44 All 10 of the contracts examined in detail by the ANAO that were let by open tender listed conditions for participation in the request documentation. Common conditions included:

- being financially solvent;

- compliance with relevant legislation including the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 and Work Health and Safety Act 2011;

- agreement to the public disclosure and the right of audit requirements of the Commonwealth; and

- acknowledgement and willingness to cooperate with TA’s public accountability requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and adhere to relevant internal TA policies.

Selecting suppliers invited from panels

2.45 The CPRs state that officials should, where possible, approach multiple potential suppliers on a standing offer to maximise competition.45 Finance guidance further states that:

Irrespective of the value, an entity must be able to justify the decision to use the panel and demonstrate value for money. This is particularly relevant where only one supplier has been approached. Decisions should be documented and proper records maintained in accordance with the CPRs [7.2–7.5].

2.46 For three of the 33 contracts examined (nine per cent), TA used an existing arrangement by other entities.

- In the one instance where TA employed a competitive approach in accessing a panel established by open tender by another Commonwealth entity, the records indicate that the three suppliers approached were selected ‘due to their strong industry reputation for providing end to end services and delivery capability’.

- In the instance where TA approached only one supplier on a panel established by open tender by another Commonwealth entity, the supplier selected had previously provided services to TA. TA’s records state that there ‘are efficiencies to be gained by using the same supplier to extend the existing methodologies for each of the three projects’.46 Such an approach of approaching existing or previous suppliers, and no other potential suppliers, is not consistent with the CPRs which, instead, require that entities treat all tenderers, and potential tenderers, in a fair and non-discriminatory manner.

- In the instance where TA accessed an existing prequalification scheme administered by the New South Wales Government, the records indicate that the one supplier approached had previously been engaged by TA and that ‘TA has no concerns about its performance’.47 Again, approaching incumbent or previous providers, and no other potential suppliers, is not consistent with the CPRs.

Limited tenders conducted

2.47 Seventeen (52 per cent) of the sample of 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, with an aggregate value of $27.9 million at execution48, were let through limited tender.

Justifying the use of limited tenders

2.48 Under the CPRs, for each contract awarded through limited tender, an official must prepare and appropriately file within the entity’s records management system a written report that includes:

- the value and type of goods and services procured;

- a statement indicating the circumstances and conditions that justified the use of limited tender; and

- a record demonstrating how the procurement represented value for money in the circumstances.

2.49 Of the 17 contracts let through limited tender:

- 11 (65 per cent) had written records on file that included a statement indicating the circumstances and conditions justifying the use of limited tender, and a record of how value for money was achieved;

- one (six per cent) had a record documenting a justification for using a limited tender process but no record demonstrating how the procurement represented value for money;

- two (12 per cent) had written records setting out how the procurement represented value for money but no justification for using a limited tender process; and

- three (18 per cent) did not have sufficient documentation maintained on file.

2.50 For the 12 contracts where available documentation included a justification for using limited tender selection processes:

- seven were justified on the basis of being a procurement with a value below the relevant procurement threshold of $400,000;

- one was justified on the basis of limited tender condition 10.3.d.iii ‘when the goods and services can be supplied only by a particular business and there is no reasonable alternative or substitute … due to an absence of competition for technical reasons’; and

- four were justified on the basis of one of the exemptions listed in Appendix A of the CPRs:

- one under exemption 1 ‘procurement (including leasing) of land, existing buildings or other immovable property or any associated rights’;

- two under exemption 8 ‘procurement of goods and services (including construction) outside Australian territory, for consumption outside Australian territory’; and

- one under exemption 12 ‘procurement of government advertising services’.

Selecting suppliers invited in limited tenders

2.51 Of the 17 contracts examined, the records for four were insufficient to identify the basis on which TA selected the suppliers to participate. For three of these four procurements, other available TA records indicated that the supplier invited to tender had been previously engaged by TA. From the procurement records and other TA records it was evident that current or previous experience as a supplier to TA was favoured by TA in eight of the 17 limited tender procurements examined by the ANAO.

2.52 For example, Sayers Advisory Pty Ltd was procured in 2022 to support the development and implementation of an upcoming procurement by TA of creative agency services.49 TA’s evaluation report identified that the basis for approaching a sole supplier related to past work with TA (TA described this past work as placing the supplier in a ‘unique position’50) such that no other potential providers were afforded the opportunity to compete for this work. TA’s evaluation report for this procurement states that ‘Sayers was approached by Marketing in March 2022 for an initial proposal’ and that ‘TA met with Sayers on 22 April 2022 to clarify its expectations, including in relation to the variables that informed the proposed costs. Sayers was given a more comprehensive brief discussions led to refined costs within the indicative range that Sayers had originally proposed but no substantive variance.’ There were no records evidencing why Sayers was approached nor what was discussed in meetings with Sayers.

Procurement of talent

2.53 For three of the 10 procurements conducted by TA through non-competitive limited tender, totalling $657,299 at contract execution, TA advised the ANAO in August 2024 that:

Procuring talent for Tourism Australia is always done as a “Direct Source Exemption” and is not a service we can tender to market. This is for a variety of reasons:

- Our talent requirements are highly bespoke and specific to the type of project, brief or campaign;

- Creative ideas are often written for specific talent, so we cannot swap out between vendors;

- We often try to work with talent because of their unique intellectual property, their unique network or other benefits that they can bring to TA that other vendors can’t;

- We have a very rigorous Advocacy Selection Criteria that has been endorsed by the Board51, and we use this to vet talent in the initial stage to ensure TA is getting value for money, before we progress with the official procurement process of the Evaluation Report and delegation approvals.

2.54 TA advice to the ANAO in August 2024 was that the ‘official procurement process’ begins after it had identified the talent that would be engaged. At odds with TA’s approach, the CPRs state that the procurement process ‘begins when a need has been identified and a decision has been made on the procurement requirement’. For a limited tender procurement, decisions about which candidate(s) will be afforded the procurement opportunity is a key part of the procurement process and appropriate records (documenting the requirement for the procurement and the process that was followed) must be maintained.

2.55 None of the three ‘talent’ procurements included in the ANAO’s sample had a procurement plan or request documentation maintained on file. TA advised the ANAO in June and July 2024 that such documents were ‘Not Required’.

2.56 In addition, although TA advised the ANAO that the Advocacy Selection Criteria is used to ‘vet’ talent to ensure value for money is obtained, TA was unable to provide the ANAO with a completed Advocacy Selection Criteria for two of the three ‘talent’ provider procurements. The one completed Advocacy Selection Criteria document that TA was able to provide to the ANAO had been completed for an earlier procurement, and was not updated for the later procurement examined by the ANAO (the Advocacy Selection Criteria include considerations, such as social media reach and risk considerations such as whether there has been any evidence of inappropriate behaviour, that require update to remain relevant).

2.57 Furthermore, none of the three procurements had procurement records referencing the ‘Advocacy Selection Criteria’52 or demonstrating how the suppliers were assessed as meeting these criteria as part of the procurement process. In addition, there were no other possible candidates considered. Advice provided by TA in October 2017 to its board was that the Advocacy program was launched in 2010 and at that time there were more than 150 ‘Friends of Australia’ under this program, in addition to ‘influencers’.

2.58 Overall, TA’s approach to procuring talent is inconsistent with the CPRs.

Use of TA’s own panel arrangement

2.59 In 2021, TA established by open tender the National Experience Content Initiative (NECI) panel comprising 32 suppliers to provide photographic and videographic services.53 TA entered into a Deed of Standing Offer with all but one of the suppliers on the panel for an initial term of two years from the date of execution.54 Under clause 2.2, TA had the discretion to ‘extend the term of the agreement for two 12-months … by giving written notice to the Contractor at least 30 days before the end of the Initial Term.’

2.60 In August 2024, the ANAO asked TA to advise whether any of the extension options were exercised and provide supporting evidence. No advice or evidence was provided by TA.

2.61 For two of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, TA purported to use the NECI panel arrangement. The ANAO’s analysis of TA records was that separate procurement processes were not undertaken by TA when purchasing from the panel. Rather TA directly entered into work orders with the two suppliers, totalling $980,265 at execution. No records were maintained demonstrating how these engagements represented value for money.

2.62 TA referred the ANAO to the procurement plan and evaluation report relating to the procurement process to establish the NECI panel. In August 2024, TA advised the ANAO that ‘The total approved funds did not change. However, TA was required to amend the allocation of funds to suppliers mentioned in the Evaluation Report in situations such as the inability of the supplier to travel to the specified regions or their inability to meet TA’s requirements’. For each of these two procurements, TA did not develop a procurement plan to subsequently engage the supplier in 2022, only one firm was invited to quote55 and there was no evaluation report prepared.56

2.63 TA’s approach to using its NECI panel is not consistent with the CPRs. It is also reflective of practices criticised by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit57, and is at odds with guidance from the Department of Finance that58:

Once a panel has been established, an entity may then purchase directly from the panel by approaching one or more suppliers.

Each purchase from a panel represents a separate procurement process. When accessing a panel, you must be able to demonstrate value for money has been achieved for each engagement.

Procurements from existing panels are not subject to the rules in Division 2 of the CPRs. However, these procurements must still comply with the rules in Division 1 …

As advised at paragraph 9.14 of the CPRs, wherever possible, you should approach more than one supplier on a Panel for a quote. Even though value for money has been demonstrated for the supplier to be on a panel, you will still need to demonstrate value for money when engaging from a Panel, and competition is one of the easier ways to demonstrate this. Where you only approach one supplier, you should provide your delegate with reasons on how value for money will be achieved in the procurement …

Irrespective of the value, an entity must be able to justify the decision to use the panel and demonstrate value for money. This is particularly relevant where only one supplier has been approached. Decisions should be documented and proper records maintained in accordance with the CPRs (refer paragraphs 7.2 – 7.5).

Recommendation no.2

2.64 Tourism Australia increase the extent to which it employs open, fair, non-discriminatory and competitive procurement processes.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

2.65 Whilst Tourism Australia notes that many limited tenders may have been justifiably conducted in line with CPR’s, Tourism Australia will increase the extent to which it employs open procurements.

ANAO comment

2.66 The recommendation relates to the audit findings set out at paragraphs 2.23 to 2.63, including identifying how Tourism Australia’s approach to limited tenders has not been consistent with the CPRs.

Are evaluation criteria included in request documentation and used to assess submissions?

Relevant evaluation criteria were included in request documentation for 52 per cent of the contracts examined in detail by the ANAO. For the remaining 48 per cent, either the request documentation did not include any evaluation criteria (12 per cent) or there were no records of the request documentation on file (36 per cent). This situation is not consistent with the CPRs which require evaluation criteria to be included in the request documentation.

2.67 The CPRs require relevant evaluation criteria to be included in request documentation to enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair, common and appropriately transparent basis.59 Request documentation must include a complete description of evaluation criteria to be considered in assessing submissions and, if applicable to the evaluation, the relative importance of those criteria. Additionally, if the entity modifies the evaluation criteria during the course of a procurement, it must transmit all modifications to all the potential suppliers, and allow adequate time for potential suppliers to modify and re-lodge their submissions if required.

2.68 For 12 (36 per cent) of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, TA records did not include the relevant request documentation.60 Of the remaining 21 contracts where request documentation was maintained on file:

- 17 included evaluation criteria. Common evaluation criteria included the tenderer’s capability and experience, the proposed approach or methodology, resources including key personnel, and value add. Price/costs were included as a criterion for three (18 per cent) of these procurements. For 15 of these procurements the criteria were weighted (88 per cent) and for two they were not.

- four did not include any evaluation criteria in the request documentation:

- for one of these four procurements, the procurement plan had identified the evaluation criteria. This related to TA’s procurement of Running PR (Xiamen) Co. Ltd to provide event management services for the Business Events Australia Asia Showcase 2022 – China event held in March 2022.61 A limited tender request for quotation was issued in November 2021 to three candidates identified in the procurement plan with Running PR later added as a fourth candidate (the subsequent evaluation report stated that the fourth candidate was added because it ‘had capacity’). The request documentation identified conditions for participation but did not identify any evaluation criteria.62 The evaluation report identified that five weighted criteria were applied to the two responses received to select Running PR at a fee of RMB500,000 with a cap of RMB1 million for fees plus expenses.

- for the remaining three procurements, TA had approached the market without a procurement plan having been prepared or approved.63

2.69 ANAO analysis on the application of the evaluation criteria during the evaluation process is discussed in paragraph 2.79.

Recommendation no.3

2.70 Tourism Australia strengthen its procurement controls to ensure that procurement request documentation includes:

- the evaluation criteria that will be applied, together with any weightings; and

- the way that prices will be considered in assessing the value for money offered by each candidate.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

2.71 Although Tourism Australia notes that evaluation criteria are included in its standard templates and in the majority of the sample, Tourism Australia will ensure evaluation criteria and price considerations are more consistently applied.

Are contracts awarded to the candidates assessed as providing the best value for money?

Just over half of the contracts examined by the ANAO were awarded to the candidate where records demonstrated that it had been assessed by TA to offer the best value for money. For the remaining 48 per cent of contracts where value for money outcomes had not been demonstrated, this was primarily the result of insufficient analysis being presented commensurate with the scale of the procurement, or insufficient documentation being maintained.

2.72 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. Officials responsible for a procurement must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome.

2.73 Under the CPRs, unless the entity has determined that it is not in the public interest to award a contract, a contract must be awarded to the tenderer that the entity has determined:

- satisfies the conditions for participation;

- is fully capable of undertaking the contract; and

- will provide the best value for money, in accordance with the essential requirements and evaluation criteria specified in the approach to market and request documentation.64

2.74 The ANAO examined TA’s procurements in terms of whether the records demonstrated that successful tenderers were assessed as providing the best value for money. The ANAO factored the scale, scope and risk of the procurements into its examination.

Late submissions

2.75 The CPRs state that late submissions must not be accepted unless the submission is late as a consequence of mishandling by the entity. In two instances where there was sufficient documentation maintained, the records indicated that tenders submitted after the closing date were accepted and progressed to evaluation notwithstanding that the circumstances were not consistent with those the CPRs says enable a late tender to be accepted.

- In the first instance, one tenderer submitted late but was nonetheless included for evaluation as it ‘presented a good option for TA’.65

- In the second instance, a tender was received late and by an alternative communication channel. The reason recorded for progressing this tender to evaluation was that the TA procurement team ‘understands that there can often be significant delays with emails in to and out of mainland China’ (notwithstanding that the other four tenderers were able to submit a response by the closing date) and that ‘Procurement is comfortable there was no significant advantage or disadvantage with the short delay.’

2.76 In neither instance was the late tender successful.

Screening of tenders

2.77 Further consideration must be given only to submissions that meet minimum content and format requirements.66 In all contracts examined where sufficient documentation was maintained by TA, tenderers assessed as meeting the requirements were appropriately progressed to evaluation.

2.78 In two instances, the records indicated that tenderers who had been assessed as failing the minimum requirements were progressed and assessed, an approach that is inconsistent with the CPRs.

- In one instance, five of the seven tenderers invited did not complete the conditions of participation as required but were progressed to evaluation (one of these suppliers was awarded the contract). The evaluation report stated that the ‘Committee understands that such conditions are not common practice in the property sector and [the external adviser engaged by TA to conduct the procurement on its behalf] did not emphasise their importance to prospective respondents’.

- In the second instance, one supplier was assessed as failing the minimum requirements with the tender presenting ‘some significant omissions and non-compliance’ but was nevertheless progressed to evaluation ‘due to the existing relationship with Tourism Australia, and the risk of souring that relationship if their response was not given due consideration.’ This supplier was not awarded the contract.

Evaluation of tenders

2.79 For 16 of the 33 contracts examined (48 per cent), the criteria and weightings (where applicable) applied by TA in the evaluation process were consistent with those advised to potential suppliers in the request documentation. Of the other 17 contracts:

- five (15 per cent) had some inconsistency evident:

- in four instances, evaluation criteria were applied notwithstanding that the request documentation did not include any evaluation criteria67; and

- in the last instance, the evaluation criteria applied were the same however TA assessed the tenderer as ‘acceptable’ rather than giving a weighted score as had been advised would occur in the request documentation.

- 12 (36 per cent) had insufficient documentation on file to demonstrate consistency.

2.80 While there were inconsistencies in the application of the minimum requirements and evaluation criteria, the records adequately demonstrated that contracts were awarded to candidates assessed as providing the best value for money in 17 (52 per cent) of the 33 contracts examined in detail. For 10 contracts (30 per cent), while the contracts were awarded to the highest ranked or sole tenderer, value for money outcomes had not been demonstrated with insufficient analysis being presented by the evaluation committee commensurate with the scale of the procurement. For instance, evaluation reports did not adequately explain the basis on which tenders had been assessed or why the proposed costs represented value for money in the circumstances. For the other six contracts (18 per cent), insufficient documentation was on file.

2.81 For competitive procurements, a value for money outcome was generally supported by the successful tenderer being the highest ranked against the evaluation criteria.68 For non-competitive procurements, the contract was awarded to the single supplier approached.

2.82 Benchmarking is valuable in non-competitive procurements, as it is more challenging to establish that a single bid is a reasonable market price and represents value for money. Benchmarking by TA was primarily undertaken by comparative analysis of the proposed prices against competing tenders, past contracts and TA’s internal project budget. Occasionally, TA also used other benchmarks including industry or market rates.

2.83 The ANAO identified the following shortcomings in its examination.

- Where select tenderers were invited to bid, it was common for evaluations to be less robust with tenderers’ capacity and capability largely assumed to be sufficient. For example, The Buzz Group was procured in 2022 to provide talent management and broadcast public relations support services.69 The evaluation report did not include any analysis of the proposal to support rating the supplier as ‘acceptable’ against the three unweighted evaluation criteria. Rather the supplier was identified as being ‘value for money based on successful previous cooperation on the projects’ and was awarded a contract valued at $110,000.

- It was common for records to provide limited or inadequate analysis when assessing price against benchmarks, particularly where there was only one tenderer being considered. For example, Infinity Squared Pty Ltd was procured in 2021 via a non-competitive limited tender to develop and deliver a video content series to support the Always On Creative Initiatives.70 Identifying directly comparable benchmarks can be challenging. In this instance, TA’s evaluation report advised that the proposal ‘compared favourably against recent benchmarks for work commissioned by TA’ (notwithstanding that the proposed cost was around six to eight times more expensive than the two examples referenced) and did not present further analysis explaining how this meant the proposal ‘compared favourably’. The contract was valued at $1.2 million.

Recommendation no.4

2.84 Tourism Australia strengthen its procurement practices so that it can demonstrate that contracts are awarded to the candidate that satisfies the conditions for participation, is fully capable of undertaking the contract and will provide the best value for money as assessed against the essential requirements and evaluation criteria specified in the approach to market and request documentation.

Tourism Australia response: Agreed.

2.85 Tourism Australia will strengthen its procurement practices to better demonstrate value for money and ensure evaluation criteria are appropriately documented.

Are procurement activities conducted ethically?

TA had not conducted procurements to a consistent ethical standard as required under the CPRs. Of note was that:

- conflict of interest declarations were not completed by all evaluation team members in four per cent of the contracts examined where there was sufficient documentation on file;

- for eight per cent of the contracts where advisers were appointed to assist with the procurement process, TA’s records did not include a complete list of the individuals involved; and

- the procurements of external probity advisers were deficient in relation to how those advisers were engaged as well as the limited scope of probity services obtained by TA.

2.86 Under the CPRs, officials undertaking procurement must act ethically throughout the procurement. Ethical behaviour includes:

- dealing with potential suppliers, tenderers and suppliers equitably71;

- carefully considering the use of public resources; and

- complying with all directions, including relevant entity requirements, in relation to gifts or hospitality, the Australian Privacy Principles of the Privacy Act 1988 and the security provisions of the Crimes Act 1914.

2.87 The CPRs also state that officials undertaking procurement must seek to prevent corrupt practices by recognising and dealing with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest and not accepting inappropriate gifts or hospitality.

2.88 Section 15 of the PGPA Act requires the accountable authority to govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources. The PGPA Act defines ‘proper’ as efficient, effective, economical and ethical.

Conflict of interest

2.89 Effective management of conflicts of interest should be a central component of an entity’s integrity framework. Poor practice, or the perception of poor practice, in the management of conflicts of interest will undermine trust and confidence in an entity’s activities. Where conflicts cannot be avoided, the relevant provisions of the PGPA Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 require that persons must disclose details of any material personal interest.72

2.90 Entity accountable authorities must promote the ethical management of public resources and establish and maintain appropriate systems relating to risk management and oversight and internal controls. This includes policies and procedures regarding the management of conflicts of interest.

TA internal policy

2.91 TA’s Code of Conduct requires staff to: disclose and take reasonable steps to avoid any conflict of interest (real or apparent) in connection with their employment; and act objectively, impartially and free of conflicts of interest in the conduct of their duties.

2.92 TA’s Procurement Policy states that:

Any potential or actual conflict of interest, involving either a staff member or their immediate family member, must be disclosed promptly in writing to your manager. As part of procurements valued at $100,000 or more, staff members are required to complete a conflict of interest declaration.

Evaluation members

2.93 Of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, in:

- 26 instances (79 per cent) records of completed conflict of interest declarations were maintained for all listed evaluation team members73;

- one instance (three per cent) declarations were not completed by all listed evaluation members; and

- six instances (18 per cent) there were insufficient information to enable reliable examination.

2.94 It was common for no management actions to be put in place to avoid or mitigate identified conflicts of interest, and no records documenting how conflicts had been managed.74 In August 2024, TA advised the ANAO that:

TA takes conflicts of interest seriously and believes that the management of conflicts of interest is an active process. In the sample tested, there were no material conflicts of interests recorded75, which is why management did not take any actions. In any instances where a material conflict of interest is recorded, management take appropriate action, for example excluding the individual from the scoring process.

Advisers

2.95 Of the sample of 33 procurements examined by the ANAO:

- 26 had advisers appointed during the procurement process:

- 24 had completed conflict of interest declarations for all listed adviser personnel maintained on file76; and

- two stated that advisers had been appointed but did not include a complete list of all relevant individuals involved in the procurement;

- one did not have any advisers appointed; and

- six had insufficient information to enable reliable examination.

External probity advisers

2.96 External probity advisers may be appointed where justified by the nature of the procurement. Finance guidance states that ‘The decision on whether to engage an external probity specialist should weigh the benefits of receiving advice independent of the process against the additional cost involved and include consideration of whether or not skills exist within the entity to fulfil the role.’

2.97 TA’s Procurement Policy requires an external probity adviser to be engaged for procurements valued at or above $400,000.

2.98 For at least77 17 (52 per cent) of the 33 contracts examined by the ANAO, an external probity adviser was appointed during the relevant procurement process. Of these 17 contracts, NTT Australia Digital Pty Ltd (NTT) was appointed as the probity adviser in 15 and Grosvenor Performance Group Pty Ltd (Grosvenor) for the remaining two.78

Engagement of NTT

2.99 In March 2019, TA contracted NTT to provide probity services on an as needs basis at a cost of $30,000.79 As at 30 June 2024, there were no records maintained in TA’s systems demonstrating how NTT’s services had been procured. In July 2024, TA advised the ANAO that ‘The total value was below $100k so formal tendering documentation was not required.’ This approach was inconsistent with TA’s Procurement Policy which requires multiple quotes to be sourced.

2.100 The initial contract term was one year (from 20 February 2019 to 19 February 2020) with two extension options of one year each.