Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Proceeds of Crime

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Australian Federal Police’s, the Australian Financial Security Authority’s and the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of property and funds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (the POCA) provides a scheme (the ‘POCA scheme’) to trace, restrain and confiscate the proceeds of crimes against Commonwealth law. It seeks to disrupt, deter and reduce crime by undermining the profitability of criminal enterprises, depriving persons of the benefits derived from crime, and preventing reinvestment of the proceeds in further criminal activity.

2. The POCA also provides a scheme that allows for confiscated funds to be given back to the community in an endeavour to prevent and reduce the harmful effects of crime in Australia. This mechanism has provided funding to non-government and community organisations, local councils, as well as Commonwealth and state police forces and Commonwealth criminal intelligence entities.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The audit objective was to assess whether the Australian Federal Police (AFP), Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) and the Attorney–General’s Department (AGD) effectively carried out key operational and advisory functions related to property and proceeds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- effective restraint is achieved by the AFP and/or AFSA through the timely implementation of appropriate court orders;

- AFSA administers restrained property in an efficient and economical manner and consistent with relevant court orders;

- AFSA disposes of forfeited property in an appropriate manner and transfers the net proceeds to the Confiscated Assets Account;

- AGD provides advice to the Minister for Justice on which proposals for funding from the Confiscated Assets Account represent the best value for money; and

- the AFP and AFSA report against benchmarked performance measures.

Conclusion

5. The AFP, AFSA and AGD effectively carry out key operational and advisory functions related to property and proceeds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

6. Risk based planning procedures are in place for deciding which property should be restrained and what conditions should be placed on the property when seeking a restraining order. The manner in which restraining orders are implemented depends on the type of property under restraint. For the major classes of property, AFP and AFSA processes have worked well and custody and control of property has been achieved in a way that minimises the risk of the property being dissipated.

7. AFSA has appropriate custodial arrangements in place for all types of property. Legislative and administrative constraints currently limit the ability the of Official Trustee1 to achieve improved rates of return from the substantial amount of funds held in the restrained and forfeited monies bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account. AFSA also manages property in a way that is consistent with the relevant court orders and disposes of forfeited property in an appropriate manner in order to maximise the sale proceeds.

8. The AGD has established effective processes to identify the possible use of funds from the Confiscated Assets Account. It has also advised the Minister for Justice on proposals to assist in achieving value for money from expenditure. During the financial years 2010–11 to 2015–16, the main beneficiaries of funding have been Commonwealth law enforcement and criminal intelligence agencies. Significant funding has also been approved for non-government, community organisation and local council projects, with the New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland police forces also receiving funding.

9. The AFP publicly reports the estimated recovery value of property restrained each year. When combined with the Australian Crime Commission’s (ACC’s) public reporting of the estimated value of property confiscated each year, this illustrates the trends in the amount of criminal proceeds intercepted by the POCA scheme. AFSA also undertakes limited public reporting on its administration of property. This reporting does not include information on the costs of administering property under its custody and control, which is an important aspect of its overall performance in relation to the proceeds of crime. However, AFSA has made some improvements in its internal reporting capacity about the costs of managing property and is in the early stages of developing benchmarks for some aspects of these costs.

Supporting findings

Restraining property

10. Planning and decision-making procedures by the Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce investigators and litigators relating to restraint are risk-based. Where the AFP has judged that the risk of dissipation2 is high, restraining order applications include a provision for custody and control of the property to be granted to AFSA.

11. Restraining orders are implemented in a timely manner and in a way that minimises the risk of property being dissipated. However, the AFP could do more to register orders involving motor vehicles on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR) in a timely manner.

Custody and disposal of property

12. Custodial arrangements for property that has been placed into the custody and control of AFSA vary depending on the type of property restrained. Testing demonstrates that appropriate custodial arrangements are in place for all types of property. Management of the funds held in the restrained and forfeited monies bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account reflect legislative and administrative constraints that limit the ability of the Official Trustee to achieve improved rates of return from the substantial amount of funds held in these accounts.

13. AFSA manages property in a way that is consistent with the relevant court orders. Where consent, variation and/or exclusion orders are granted by the court, AFSA has acted consistently with the court order.

14. In 2015–16, the disposal processes utilised by AFSA have achieved sale proceeds from forfeited property which have exceeded the estimated value of the property, as determined by an independent and/or certified valuer, in 76 per cent of matters, including all of the higher-value property.

How funds from the Confiscated Assets Account are used

15. The processes through which the possible use of funds—stand-alone projects or grant programs—are identified and submitted for the Minister for Justice’s approval have evolved over time. In recent years, more structured and targeted processes have been implemented in order to assist in achieving better overall outcomes from Confiscated Assets Account funding. The AGD provided the Minister with relevant advice to assist him in meeting his decision making obligations.

16. The main beneficiaries of funding from the Confiscated Assets Account have been Commonwealth criminal intelligence or law enforcement entities. Significant funds have been approved for non-government, community organisation and local council projects, mainly through the Safer Streets Programme. The New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland police forces have also received funding.

Performance Monitoring and Reporting

17. The AFP publicly reports on the estimated recovery value of property restrained each year and whether the AFP has met the benchmark set for that year. It also internally monitors another key performance measure—the estimated value of property confiscated each year—which is publicly reported by the ACC. These two measures illustrate the trends in the criminal proceeds intercepted by the POCA scheme. In the context of a current AFP wide review of performance measures, additional metrics could be developed to provide better information both on the AFP’s performance in litigating POCA cases and, in the longer term, the effect of the POCA scheme on the underlying criminal economy.

18. AFSA’s public reporting on its administration of property under its custody and control is limited to high-level information. It is in the early stages of developing an improved internal reporting capacity to monitor the costs of managing property under AFSA custody and control. This work could be also be used to enable public reporting of the costs to administer such property, which is an important aspect of AFSA’s overall performance and responsibilities under the POCA scheme.

Recommendation

Recommendation No.1

Paragraph 3.13

The Australian Government should implement arrangements to facilitate improved rates of returns from funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account.

Attorney-General’s Department Response: Noted.

Australian Federal Police Response: Noted.

Australian Financial Security Authority Response: Noted.

Summary of entity responses

19. The summary responses to the report from the Attorney-General’s Department, the Australian Federal Police and the Australian Financial Security Authority are provided below. These responses were provided under a single covering letter from the Secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department. The letter and full responses are at Appendix 1.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) administers the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (the Act) which provides a scheme to trace, restrain and confiscate the proceeds of crimes against Commonwealth law. It seeks to disrupt, deter and reduce crime by undermining the profitability of criminal enterprises, depriving persons of the benefits derived from crime, and preventing reinvestment of the proceeds in further criminal activity.

The Act also provides a scheme that allows for confiscated funds to be given back to the community in an effort to prevent and reduce the harmful effects of crime in Australia. This mechanism has provided funding to non-government and community organisations, local councils, as well as Commonwealth and State police forces and Commonwealth criminal intelligence agencies.

Section 297 of the Act makes provision for various payments from the Confiscated Assets Account (CAA), including payments under a program approved by the Minister under section 298 of the Act. The CAA is administered by the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA).

Section 298 of the Act allows the Minister for Justice to approve programmes of expenditure for one or more of four purposes:

- Crime prevention measures

- Law enforcement measures

- Measures relating to treatment of drug addiction, and

- Diversionary measures relating to illegal use of drugs.

There is often a significant time delay between assets being restrained and the completion of legal processes leading to the confiscation and realisation of assets. It is common for the realised value of confiscated assets to be less than their estimated value at the time they were restrained. This arises where the value of assets changes over time, and where legal fees are deducted before confiscated funds are finally received into the CAA.

Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) welcomed the opportunity to contribute to the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) performance audit on the effectiveness of the Proceeds of Crime scheme.

The AFP acknowledges the commentary provided in the report and notes the ANAO’s conclusion that the AFP, AFSA and AGD effectively carry out key operational and advisory functions related to property and proceeds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Cth).

Australian Financial Security Authority

AFSA notes the report’s findings that for the major classes of property AFSA processes have worked well and custody, control and disposal of property have been achieved in a way that minimises the risk of the property being dissipated.

In respect of the bank accounts, AFSA currently earns a rate of return on funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account in accordance with the provisions of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

AFSA will work with key stakeholders and agencies to facilitate arrangements that improve rates of return from funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account whilst ensuring compliance with the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Initial legislative confiscation schemes were established by the Commonwealth and Australian states from the mid-1980s following recommendations made by a number of inquiries, notably the 1983 Royal Commission of Inquiry into Drug Trafficking. These schemes were seen as a way of targeting not only those persons directly involved in carrying out crime, but also those who ‘direct, finance and reap the most reward from crime’.3

1.2 Since the 1980s, the various Australian confiscation schemes have been extensively amended, including allowing in certain cases for property to be permanently confiscated without the need for any person to be convicted of a crime.4 Such ‘non-conviction’ based confiscation can only occur where a court makes an order to this effect. The schemes seek to disrupt, deter and reduce crime by: undermining the profitability of criminal enterprises; depriving persons of the benefits derived from crime; and preventing reinvestment of proceeds in further criminal activity. Various international agreements also provide for cooperation between countries in the investigation of suspected unlawful activity and enforcing relevant court orders where property is located overseas.5

Key common steps under the Proceeds of Crime scheme

1.3 The Commonwealth confiscation scheme is created by the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA).6 A simplified representation of the key aspects of the scheme relating to property restraint and confiscation is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Key steps in restraining and confiscating the proceeds of crime

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.4 The investigation and identification of property potentially subject to the POCA is mainly undertaken by the Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce. The Taskforce was created in 2011 and is led by the Australian Federal Police (AFP). The other members of the Taskforce are the Australian Taxation Office and the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, with staff seconded from other Commonwealth entities as needed.7

1.5 Under the POCA restraint provisions, the AFP8,9 can seek a court order to restrain property that is suspected to be the proceeds, or an instrument of, criminal activity under Commonwealth laws10, or the property of a person suspected of such criminal activity.11 Such orders prohibit, or impose restrictions on, any person from disposing or dealing with the property, including by destroying, transferring ownership to another party, or giving it away.12 Amongst other things, restraining orders allow law enforcement agencies to investigate suspected unlawful activity whilst minimising the possibility of the relevant property being dissipated due to the suspects being alerted to the investigation.13 Where the property includes bank account funds or similar, the order effectively requires the relevant financial institution to prevent any movement of funds out of specified account(s). A restraining order may be registered with the applicable state or territory land titles office or on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR).14

1.6 A restraining order may leave the property in the custody of its owner, or the AFP if the property was seized as part of a police search. Alternatively, a restraining order may give ‘custody and control’ of specified property to the Commonwealth Official Trustee in Bankruptcy (Official Trustee). The Official Trustee is a body-corporate, whose powers are exercised under delegation by officers of the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA).15 Restrained property under AFSA’s custody and control is not Commonwealth property, rather it is held on trust. During 2015–16, property with an estimated recovery value16 of $96.5 million was restrained17, of which approximately $81.6 million was restrained under AFSA’s custody and control.18 The cumulative total estimated recovery value of property under restraint as at September 2016 was $467.9 million.19 Of this, $199.0 million of property was under AFSA’s custody and control.

1.7 Permanent confiscation of property—where ownership of the property passes to the Commonwealth—can occur in a number of ways. Automatic forfeiture occurs when a person is convicted of specified serious offences and the relevant property has already been restrained. More commonly, forfeiture is through a court order, including situations where a person has not been convicted of an offence, but the court is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the person has committed a serious offence or that the property is the proceeds or instrument of such an offence. In 2015–16, property with an estimated recovery value of $57.4 million was forfeited. Property may also be confiscated through pecuniary penalty orders (PPOs), literary proceeds orders (LPOs) or unexplained wealth orders (UWOs).20 In 2015–16, six PPOs were made, totalling $1.5 million. No LPOs or UWOs were made.

1.8 Once property is forfeited and any appeal process has been exhausted, any non-monetary property such as real estate, motor vehicles or jewellery will be sold by AFSA. The proceeds from such sales, plus relevant forfeited funds held in dedicated Official Trustee bank accounts, are transferred to the Confiscated Assets Account after AFSA have deducted their fees and any third-party service provider expenses. In 2015–16, $59.7 million was transferred into the Confiscated Assets Account.21 As at 1 July 2016, the balance of the account was $112.6 million.

1.9 The Attorney–General’s Department (AGD) provides advice to the Minister for Justice on the use of funds from the Confiscated Assets Account, particularly for purposes prescribed by section 298 of the POCA. These purposes are:

- crime prevention measures;

- law enforcement measures;

- measures relating to treatment of drug addiction; and

- diversionary measures relating to the illegal use of drugs.

1.10 In 2015–16, the Minister approved a total of $47.5 million of section 298 funding to a range of Commonwealth and state based criminal intelligence or law enforcement entities, local councils and non-government and community organisations.

Costs and funding of Proceeds of Crime activities

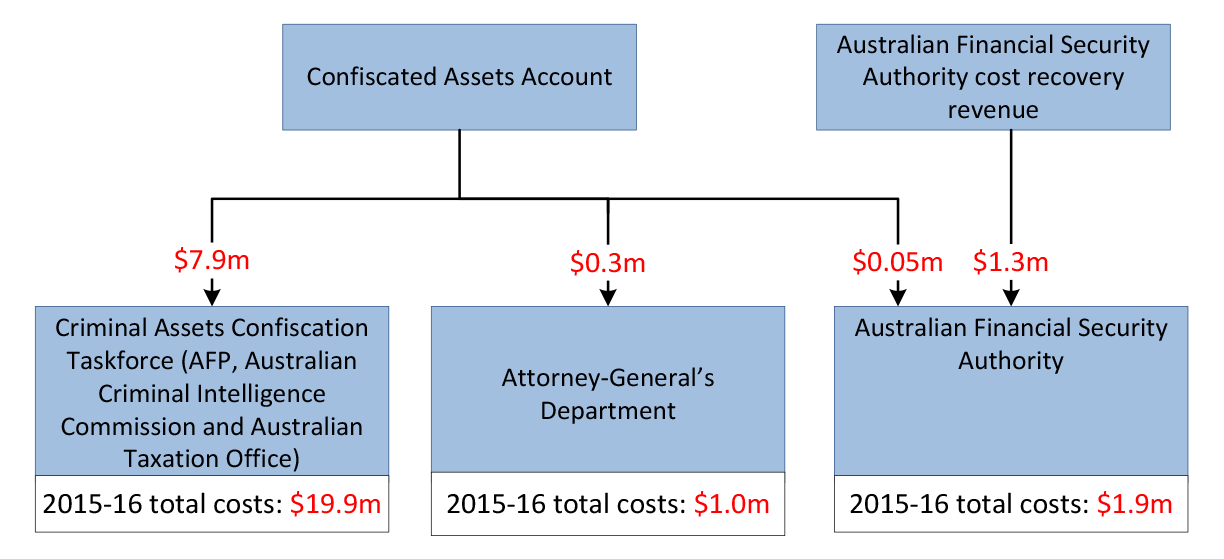

1.11 The Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce (which includes the AFP, the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission and the Australian Taxation Office), AFSA, and the AGD all have functions in the operation of the broader proceeds of crime scheme. The estimated cost, including third-party service provider costs, for each of these functions in 2015–16 as they relate to proceeds of crime activities is shown in Figure 1.2. Where they received funding from the Confiscated Assets Account or through cost recovery sources, this is also shown. Of the $19.9 million cost for the Taskforce, $18.0 million is attributable to the AFP.

Figure 1.2: 2015–16 cost of entity proceeds of crime functions and funding received from the Confiscated Assets Account or cost recovery sources for these functions in 2015–16

Source: ANAO analysis based on Information supplied by AFP, AFSA, AGD, ACIC and ATO.

Audit approach

1.12 The audit objective was to assess whether the AFP, AFSA and AGD effectively carried out key operational and advisory functions related to property and proceeds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

1.13 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- effective restraint is achieved by the AFP and/or AFSA through the timely implementation of appropriate court orders;

- AFSA administers restrained property in an efficient and economical manner and consistent with relevant court orders;

- AFSA disposes of forfeited property in an appropriate manner and transfers the net proceeds to the Confiscated Assets Account;

- AGD provides advice to the Minister for Justice on which proposals for funding from the Confiscated Assets Account represent the best value for money; and

- the AFP and AFSA report against benchmarked performance measures.

1.14 In addition to discussions with relevant staff in the AFP, AFSA and AGD, and a review of key policy, procedural and risk management documentation, the audit methodology included:

- AFP—examination of documentation regarding the commencement of initial POCA litigation for all cases which commenced in 2015–16; and financial and performance information from the AFP PROMIS case management system.

- AFSA—inspection of storage facilities in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne and external viewing of real estate in Sydney and Melbourne; detailed review of a sample of 84 cases (from a total population of 255 cases) either finalised22 by AFSA during 2015–16 or still under their management as at 1 July 2016; financial and performance information from the AFSA Proceeds of Crime Case Management System (POCMAN) or relating to the Confiscated Assets Account; and relevant analysis from the ANAO’s auditing of AFSA’s 2015–16 financial statements.

- AGD—departmental advice to the Minister for Justice relating to 44 proposals for funding from the Confiscated Assets Account which the Minister approved between 2010–11 and 2015–16.

1.15 The performance audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $437 654.

1.16 The team members for this audit were Angus Martyn, Anne White, Ben Cantrill, Joyce Knight, Andrew Rodrigues and Fiona Knight.

2. Restraining property

Areas examined

This chapter examines how the Australian Federal Police (AFP) decides which property should be included in applications for restraining orders, including whether custody and control of property should be awarded to the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA). It also examines how restraining orders are implemented and what actions are taken by the AFP and AFSA to minimise the risk of restrained property being dissipated.

Conclusion

Risk based planning procedures are in place for deciding which property should be restrained and what conditions should be placed on the property when seeking a restraining order. The manner in which restraining orders are implemented depends on the type of property under restraint. For the major classes of property, AFP and AFSA processes have worked well and custody and control of property has been achieved in a way that minimises the risk of the property being dissipated.

Are risk-based planning procedures in place for deciding which property should be restrained and what conditions should be placed on the property?

Planning and decision-making procedures by Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce investigators and litigators relating to restraint are risk-based. Where the AFP has judged that the risk of dissipation is high, restraining order applications include provision for custody and control of the property to be granted to AFSA.

2.1 Potential Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA) cases are initially reviewed by the multi-entity Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce (CACT) through its regular case forum meetings. The CACT uses a prioritisation matrix to inform the decision whether individual cases will be accepted for further investigation. Case forum meetings are also used to identify appropriate treatment options, such as referral to the AFP Criminal Assets Litigation (CAL) area for commencement of litigation or referral to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) for action, such as the raising of a tax liability.

2.2 Referral to the CAL area is done via a standard template which contains key information about the case, including the details of the property that is suspected of being the proceeds of, or instrument of crime. The AFP litigators consider the merits of the case, and then provide written advice to the CAL state office coordinator recommending that the coordinator seek approval from the CAL manager to commence legal action under the POCA.23 The ANAO examined the advices for all new matters in which the AFP commenced POCA litigation in 2015–16 (41 cases in total). The advice for each case outlines the property proposed to be restrained, its estimated recovery value, information outlining what, if any, alternative courses of action regarding the property have been considered, and summary information on relevant risks.

2.3 The level of information regarding the relevant risks varied in the advices examined by the ANAO. Key risks that were addressed included the possible dissipation of property; location of the property; possible effects of restraint on third parties; whether the estimated cost of POCA litigation was likely to exceed $500 000; and the potential for costs or damages being awarded against the AFP in the event that all, or a part of, the property was returned to the owner or another party with an interest in the property. If the risk assessment identified that the case was likely to be the subject of public scrutiny, generate high levels of publicity, and/or where the estimated value of assets to be restrained was likely to exceed $25 million the case was to be classed as high risk. High risk cases are referred to the AFP Commissioner for approval. There was only one such matter for 2015–16. The Commissioner approved commencement of POCA proceedings and obtained initial restraining orders in November 2015.

2.4 The advice provided to the CAL manager also sets out whether it is proposed to pursue the matter through civil (non-conviction) or conviction based forfeiture of property; or alternatively through a pecuniary penalty order, a literary proceeds order, or an unexplained wealth order. For the matters that commenced in 2015–16, 90 per cent were intended to be pursued via civil (non-conviction) forfeiture.24,25 Civil based restraining and forfeiture POCA litigation may proceed in parallel with separate criminal prosecution, although the courts retain the ability to place a stay on the POCA litigation if it considers it in the interests of justice to do so.

2.5 As part of its risk based approach, the AFP can apply to the court for custody and control of restrained property to be awarded to AFSA. Internal AFP guidelines provide that this is the default position in applications for restraining orders submitted to the court for all types of property ‘unless there is a good reason to the contrary’. The AFP also advised the ANAO that custody and control is normally sought for bank accounts, seized cash, and for real estate, or other forms of physical property where there are indications of an imminent sale, or if the property is a high value motor vehicle, marine vessel or aeroplane.

2.6 In the 41 new cases litigated by the AFP in 2015–16, 32 (78 per cent) involved restraining orders which gave custody and control of specified property to AFSA.26 In the nine cases where custody and control of the property was not given to AFSA, eight of the nine involved property seized by the AFP upon execution of a search warrant or involved real estate. One case involved a bank account where the AFP contacted the financial institution directly advising that the funds in the bank account were to be restrained.

2.7 Where the AFP intends to apply for custody and control of property to be granted to AFSA the AFP may consult with AFSA prior to lodging the application for the restraining order. Consultation between AFSA and the AFP where the application seeks to have custody and control awarded to AFSA has been emphasised in a Memorandum of Understanding between the AFP and AFSA which came into effect in September 2016.27 Such consultation provides AFSA with an opportunity to discuss with the AFP the potential costs and/or resources that may be required to preserve property that the AFP proposes to include in a restraining order. In the two months following the entry of the MOU, the AFP consulted with the AFSA about those proposed orders involving motor vehicles and real property. There was no consultation in relation to orders where the main property to be restrained was cash or bank accounts. AFSA advised the ANAO that it considered this was appropriate as pre-order consultation was really only relevant in instances where there was ‘an added degree of complexity as to how the order(s) might be implemented or … [involved] … a unique asset … or perhaps significant AFSA resourcing’.

2.8 In cases where the AFP intends to apply to the court for AFSA to have custody and control of property, the advice to the CAL manager does not currently address if AFSA has been consulted. To reflect the increased emphasis on consultation in the MOU, the template used to provide advice to the CAL manager could include a provision noting whether AFSA has been consulted and if so whether they have raised any concerns about the property to be included in the proposed order. This would reduce the likelihood of the AFP having to return to court to seek an amendment to an order authorising the release of specified property from AFSA’s custody and control.

Once obtained, are restraining orders implemented in a timely manner and in a way that minimises the risk of property being dissipated?

Restraining orders are implemented in a timely manner and in a way that minimises the risk of property being dissipated. However, the AFP could do more to register orders involving motor vehicles on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR) in a timely manner.

2.9 The risk of property being dissipated prior to implementation of orders is managed through a range of methods, including having order applications heard in the absence of the property owner(s) and having orders provide for delayed notification to the property owner(s).

2.10 Once a restraining order has been granted by the courts the initial actions to implement the restraining order are undertaken by the AFP. Where the court directs AFSA to take custody and control of restrained property, the AFP will provide a copy of the order to AFSA. The ANAO’s testing28 demonstrated that in 83 per cent of cases the copy was provided to AFSA no later than the next calendar day. Of the remaining 17 per cent, representing 11 cases, most of the property involved had already been seized by law enforcement agencies, was real estate or some other type of property where the risk of the property being dissipated in the short–term was low.

2.11 The specific actions undertaken by the AFP, and if applicable, AFSA to implement the order and minimise the risk of dissipation depends on the type of property involved.29

Bank Accounts

2.12 Funds held in bank accounts are the most readily dissipated form of property.

2.13 When bank accounts are restrained, the AFP provides the relevant financial institution with a copy of the court order via a dedicated email address. The order effectively requires that the relevant financial institution prevent any movement of funds out of bank account(s) identified in the restraining order. Across the 41 new matters litigated by the AFP in 2015–16, 22 involved bank accounts. The ANAO found that in 18 of the 22 cases (82 per cent), the AFP provided a copy of the court order to the financial institution on the same day the order was made. In three of the four other cases, notice was given the day after the order, with notice in the remaining case being given two days after the order was made.

2.14 Where AFSA has been directed to take custody and control of the restrained bank account(s), AFSA contacts the financial institution and directs that the balance of funds held in the account(s) is to be transferred to the restrained monies bank account held by AFSA. As at November 2016, $145.6 million in restrained bank account funds was in the custody and control of AFSA.

2.15 The ANAO tested a sample of 84 matters initiated between 2003 and 2016. This testing identified 32 matters (involving a total of 302 bank accounts) where a restraining order directed AFSA to take custody and control of the relevant bank accounts. In 89 per cent of these cases, AFSA contacted the relevant financial institution to direct that the funds be transferred no later than seven calendar days after the court order was granted.30 In 84 per cent of cases, AFSA received the funds no later than 14 calendar days after the date the request had been sent to the relevant financial institution.31

2.16 The funds held in the account/s to be restrained can fluctuate between the time the AFP CAL team are considering applying for, and the date that the court grants, the restraining order. The ANAO reviewed 20 cases, each involving multiple bank accounts that were transferred to AFSA following a custody and control order. In five of these cases, the balances of one or more of the transferred accounts were at least $10 000 less than AFP pre-restraining estimates and two of these involved amounts of over $1 million.

2.17 As a result of the ANAO’s audit, the AFP undertook an analysis on the five cases and provided the results to the ANAO. This analysis indicated that the reduction in the account balances between the pre-restraining estimates and the date of actual restraint was mainly due to the account holders using the relevant funds to purchase or develop property, or transferring funds to other accounts. The analysis concluded that in these cases the relevant property and accounts had also been restrained.

Real Estate

2.18 As at 1 July 2016, AFSA held real estate valued at $77.4 million in its custody and control, including property that had been forfeited but not yet disposed of.

2.19 To restrain real estate, AFP procedures require that the restraining order is registered against the property title through the relevant state or territory land titles office, legally securing the property and preventing the owner from dealing with it. Where custody and control is awarded to AFSA, AFSA conducts a search to check whether the restraining order has been registered by the AFP on the title.32

2.20 Of the 84 AFSA administered matters that were selected for testing by the ANAO, 20 involved AFSA being given custody and control of real estate. Collectively, these 20 matters involved 71 individual pieces of real estate. AFSA was able produce evidence of the results of the title searches for 54 of the 71 pieces. Of these 54, ANAO testing showed that the restraining order had been registered by the AFP for 40 of the pieces and for 14 that the restraining order had not been registered at the time the search was done. In the remaining 17 instances, the results of the title search were not recorded by AFSA: 15 of these relate to a single case dating back to 2003. Since 2011 only one piece of real estate has been identified by the ANAO where AFSA records did not record if a title search had been undertaken.33

2.21 For the 14 pieces of real estate where the title search conducted showed that the restraining order had not been registered, AFSA advised the ANAO that in all of these cases AFSA contacted the AFP and were advised by the AFP that for five pieces of real estate that the restraining order had been lodged but the dealing had not yet been registered on the title.34 In order to obtain more complete information on the registration of the restraining order by the AFP, the ANAO tested a smaller sample of nine pieces of real estate, using AFP records. This showed that the restraining order was registered in all cases within two calendar days.

Motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes

2.22 As at 1 July 2016, 61 motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes, worth an estimated $7.1 million were in the custody and control of AFSA.35

2.23 Once the restraining order is granted, AFP procedures mandate the registration of an interest on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR). Where AFSA has been directed to take custody and control of the motor vehicle, marine vessel and/or aeroplane, AFSA conducts a search on the PPSR to confirm that the AFP has registered its interest and arranges for the collection, transportation and storage of the vehicle.

2.24 To test how promptly the AFP registers the interest on the PPSR the ANAO examined a sample of 11 restrained motor vehicles across nine matters. This testing showed that interests had been registered for eight vehicles on average 20 calendar days after the restraining order had been granted by the court. For two vehicles the initial registration failed and due to an administrative oversight by the AFP was not followed up. For the remaining vehicle no interest was lodged.36 In this matter the AFP advised that the vehicle was collected by AFSA at the time that the search warrants were executed.

2.25 The registration of an interest is most important if the vehicle has not been placed into the custody and control of AFSA or a variation and/or exclusion order has been lodged seeking the vehicles release.37 In these circumstances the registration of the interest acts as a safeguard to ensure that the AFP can recover its interest in the vehicle if the vehicle is sold or otherwise disposed of in breach of the restraining order.

2.26 Testing undertaken by the ANAO on a sample of 84 matters initiated between 2003 and 2016 identified that across 23 matters, AFSA was directed to take custody and control of 121 motor vehicles, marine vessels and/or aeroplanes. Of the 121 motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes, 114 were placed into the custody and control of AFSA at the time of restraint. Of these 114 items, AFSA disclaimed interest in 50.38 Out of the 64 vehicles a review of AFSA records located the results of the PPSR search for only 37 of the remaining vehicles, with the results of the other 27 being unknown.39

2.27 Since 2015 a total of nine vehicles have been restrained and placed into the custody and control of AFSA. For these nine vehicles, AFSA’s record-keeping has been somewhat more consistent, with the results of the PPSR search being recorded for eight. Of these eight, the search confirmed that an interest has been registered by the AFP in seven. As a result of the ANAO’s audit, AFSA advised the ANAO it would review its written work instructions to further improve staff performance regarding recording PPSR (and land title) search results and any follow-up action where a search shows restraining orders have not been registered.

2.28 The ANAO also tested the timeframe to achieve control. A review of AFSA records by the ANAO found records specifying the actual date on which physical control was obtained for 34 (60 per cent) out of 57 motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes placed into the custody and control of AFSA. Of these 34, AFSA gained control over 32 (94 per cent) no later than 14 calendar days after the court order was granted.40

3. Custody and disposal of property

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Australian Financial Security Authority’s (AFSA) management and disposal of restrained and forfeited property.

Conclusion

AFSA has appropriate custodial arrangements in place for all types of property. Legislative and administrative constraints currently limit the ability the Official Trustee to achieve improved rates of return from the substantial amount of funds held in the restrained and forfeited monies bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account. AFSA also manages property in a way that is consistent with the relevant court orders and disposes of forfeited property in an appropriate manner in order to maximise the sale proceeds.

Recommendation

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at facilitating improved financial management of funds held in restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account.

Does AFSA have appropriate custodial arrangements in place?

Custodial arrangements for property that has been placed into the custody and control of AFSA vary depending on the type of property restrained. Testing demonstrates that appropriate custodial arrangements are in place for all types of property. Management of the funds held in the restrained and forfeited monies bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account reflect legislative and administrative constraints that limit the ability of the Official Trustee to achieve improved rates of return from the substantial amount of funds held in these accounts.

3.1 Where the court has directed the Official Trustee to take custody and control of property (‘controlled property’), it can be a considerable period of time before the property is potentially forfeited to the Commonwealth.41 Of all the cases finalised by AFSA in 2015–16 where property was placed into the custody and control of AFSA, 39 per cent took more than two years to complete. Across the 40 active matters in the AFSA sample, as at 1 July 2016, it had been on average, 3.6 years since the date of the initial restraining order.42

3.2 Under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA), the Official Trustee may do anything that is ‘reasonably necessary for the purpose of preserving the controlled property’.43 Custodial arrangements to preserve property vary depending on the type of property under restraint. The most common types of restrained property include bank accounts; real estate; motor vehicles, marine vessels and/or aeroplanes; seized cash; and jewellery.

3.3 AFSA maintains insurance with Comcover for the real estate; motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes; and other property in its custody and control valued at over $10 000. As at 1 July 2016, the policy provided approximately $42 million of insurance cover, for an annual premium of $213 500.44

Bank Accounts

3.4 As discussed at paragraph 2.14, where custody and control of restrained bank accounts has been granted to AFSA, AFSA contacts the relevant institution and directs them to transfer the funds in the account(s) to the Official Trustee restrained monies account. All of the restrained money from all cases is held in this single account.45 These funds are held in trust pending the outcome of POCA litigation and are not Commonwealth money.

3.5 For internal management and accounting purposes, AFSA creates a separate ‘virtual’ bank account for each account restrained.46 These virtual accounts are used to identify and track the funds restrained from each bank account but do not hold any actual funds. If the restrained funds are forfeited, AFSA transfers the total amount that was restrained plus any interest which has accrued into the AFSA forfeited monies account, where it is held pending final transfer to the Confiscated Assets Account.

3.6 The ANAO’s auditing of AFSA’s 2015–16 financial statements demonstrated that the relevant bank reconciliation controls are operating effectively. Transactions in and out of the restrained and forfeited accounts were supported by appropriate approvals and relevant documentation. Transactions in and out of the Confiscated Assets Account were also in accordance with the purpose of the account as set down by the POCA.

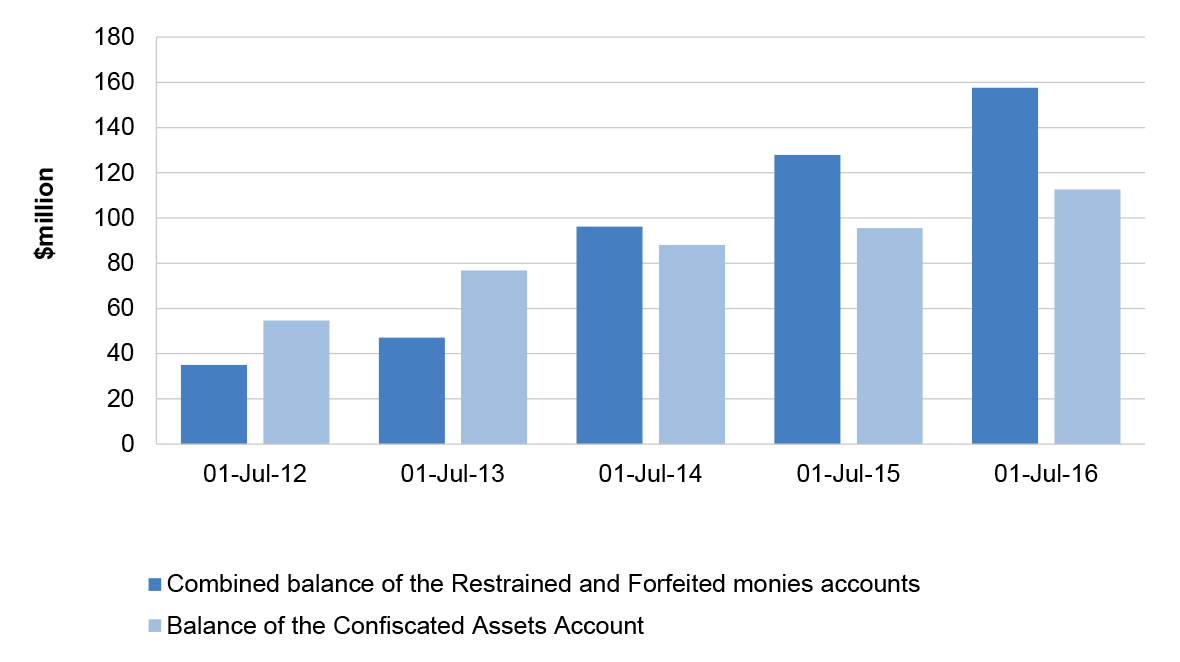

3.7 As shown in Figure 3.1, funds held in the restrained and forfeited monies accounts47 and the Confiscated Assets Account have grown substantially in recent years.

Figure 3.1: Growth of funds held in the proceeds of crime bank accounts between 2011–12

and 2015–16

Source: AFSA.

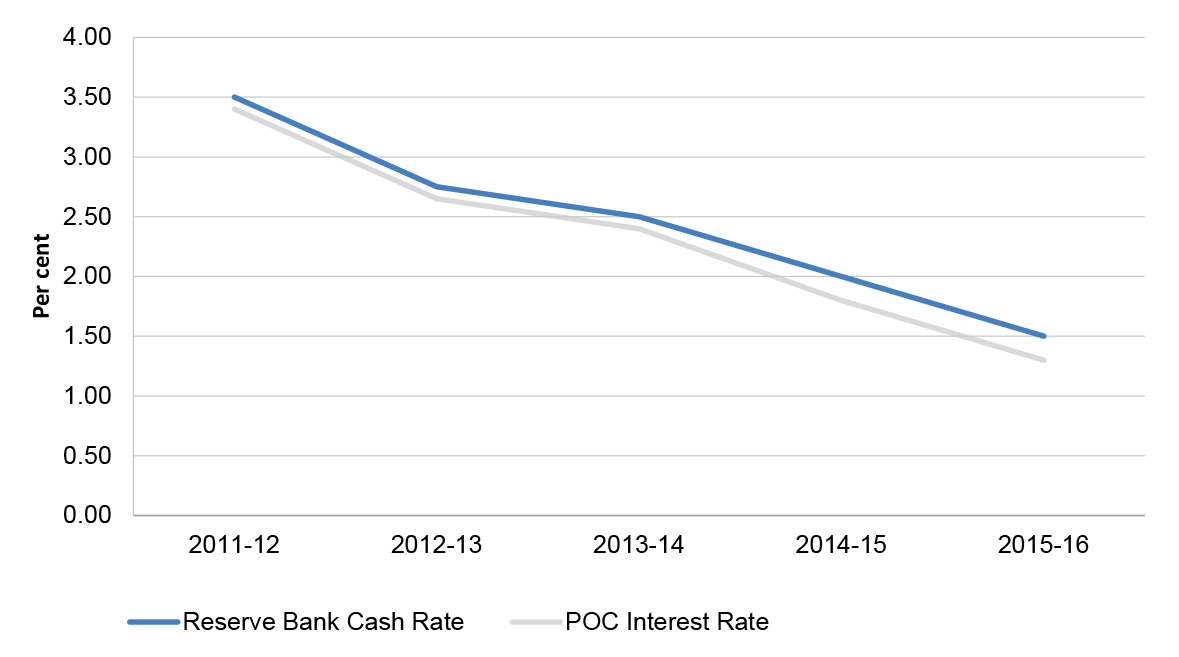

3.8 Banking services to AFSA and the Official Trustee, including the restrained and forfeited monies accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account, are provided by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). All these accounts are business transaction accounts where the funds are held ‘at call’. In 2016, AFSA and the Official Trustee renewed the existing contract for banking services with the CBA48, which provides that the variable interest rate offered on the accounts:

shall make appropriate allowance for the overall quantum of funds invested … which should result in provision of a better interest rate compared to the interest rates available to retail investors.49

This rate is periodically reviewed and agreed between AFSA and the CBA. While the rate is not explicitly linked to any benchmark, over the last several years it has declined from 3.4 per cent to 1.3 per cent as at December 2016, mirroring similar falls in the Reserve Bank of Australia (official) cash rate.

Figure 3.2: Comparison of Interest rate achieved on proceeds of crime bank accounts with the Reserve Bank (official) cash rate

Source: AFSA.

3.9 AFSA advised the ANAO that it considered that the 1.3 per cent interest rate currently being applied to accounts would not be bettered by another banking institution, as at-call accounts generally receive an interest rate considerably below the official cash rate.50

3.10 AFSA’s position is that there are also some practical and legal constraints on the Official Trustee that limit the manner in which the funds in the relevant accounts can be managed. The practical constraints include the need to release funds from the accounts, for example pursuant to a court order, or for the Confiscated Assets Account, a ministerial decision. For restrained funds, the legal restraint related to the scope of the mandate for the Official Trustee to invest funds to generate a return, as opposed to the mere preservation of the funds. For the Confiscated Assets Account, an officer of AFSA would require a delegation from the Finance Minister under the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 in order to invest the relevant funds.

3.11 An analysis of all accounts with balances over $100 000 that were transferred into the Confiscated Assets Account in 2015–16 showed that, prior to transfer, funds stayed in the restrained monies account for an average of 423 days and funds in the forfeited account stayed for an average of 95 days.51 A separate ANAO analysis of the 32 matters (or 302 bank accounts) identified four matters where a court order directed AFSA to withdraw funds from restrained bank accounts, and one matter where criminal charges were withdrawn and the balance of the restrained funds ($1.85 million) had to be released to the owner.52 For the four matters, where the court directed that funds be released, the amounts varied from $750 000 to less than $5000.53 The identification of only five matters out of 32 suggests that calls on the restrained monies account due to court orders occur infrequently and as such the risk of a rapid reduction in the overall account balance is relatively low.

3.12 In view of the significant growth in the funds being held in the relevant accounts in recent years and the length of time that funds are routinely held at least in the restrained monies account, it would be timely to implement revised administrative and legislative arrangements applying to the management of all of the accounts, having regard to the underlying policy objectives of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Recommendation No.1

3.13 The Australian Government should implement arrangements to facilitate improved rates of returns from funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account.

Attorney-General’s Department Response: Noted.

3.14 The Department agrees with the report’s finding at page 25 that there are ‘… some practical and legal constraints on the Official Trustee that limit the manner in which the funds in the relevant accounts can be managed’.

3.15 The Department notes that the policy objectives of the legislative framework underpinning the treatment and distribution of restrained and forfeited funds and funds held in the Confiscated Assets Account are aimed primarily at the reduction of crime and prevention of further investment of criminal proceeds in criminal activity. The framework set out for expenditure from the Confiscated Assets Account also facilitates reinvestment of confiscated funds into programs and activities that reduce crime, improve community safety and facilitate enhanced law enforcement capabilities.

3.16 The Department is of the view that the legislative framework does not currently envisage the increasing of returns in light of the overarching policy objectives. However, the Department will consult with Government on this matter.

Australian Federal Police Response: Noted.

3.17 As the recommendation relates to implementing arrangements to facilitate improved rates of returns from funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account which is a matter for AGD and AFSA, the AFP makes no comment in relation to the recommendation.

Australian Financial Security Authority Response: Noted.

3.18 AFSA notes the ANAO’s recommendation in the report, and will work with key stakeholders and agencies to facilitate arrangements that improve rates of return from funds in the restrained and forfeited bank accounts and the Confiscated Assets Account whilst ensuring compliance with the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Real Estate

3.19 When real estate is placed into the custody and control of AFSA, the actions that AFSA undertakes vary depending on the occupancy status of the property. Where the property is occupied, achieving custody and control of the property is an administrative action. AFSA sends a letter to the respondent, their legal representative, property manager—if relevant, or the tenant notifying them that the property is under the custody and control of AFSA. The letter includes a copy of the custody and control order. Where a piece of real estate is vacant AFSA engages a locksmith to change the locks on the property to prevent the owner accessing and potentially damaging the property.

3.20 Separate to the administrative actions undertaken to notify the relevant parties that the property has been placed into AFSA’s custody and control, AFSA also carries out an inspection, obtains a valuation and takes other actions as necessary to determine the condition of the property and value it for insurance purposes. Where a property is occupied by the owner54, or tenanted, AFSA contacts the occupant to arrange an inspection and valuation of the property. Where a property is tenanted under an existing lease AFSA does not seek to amend or cancel the lease. AFSA’s actions in these cases are limited to redirecting the rental proceeds into the restrained monies account or as otherwise directed in the restraining order.

3.21 Testing by the ANAO of the 71 pieces of real estate referred to at paragraph 2.20 showed that significant time may pass before AFSA is able to determine the occupancy status, and arrange for an inspection and valuation of the property. This has occurred in situations where the real estate is occupied but no standard lease agreement is in place; the owner has sought court approval to sell; the property is a commercial premises; the premises is occupied by a relative of the owner; or where the property is still under construction.

Motor vehicles, marine vessels and/or aeroplanes

3.22 Motor vehicles are physically seized and transported to secure storage facilities while aeroplanes and marine vessels generally remain at existing hangars and marinas. The ANAO inspected dedicated third-party storage premises in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. Security arrangements varied, but no obvious deficiencies were observed. All motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes listed in AFSA’s records as being stored at the inspected premises were sighted by the ANAO and were receiving some degree of preventative care and maintenance. Examples of vehicles sighted during these inspections are shown at Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Examples of vehicles under the custody and control of AFSA

Source: Photographs from fieldwork undertaken by the audit team in August 2016.

3.23 During 2016, AFSA reviewed several storage arrangements, including through physical inspections of the storage facilities. As a result of these reviews, AFSA changed motor vehicle storage providers in Sydney and Brisbane to reduce storage costs and improve levels of care and maintenance, thereby achieving better overall value for money.

3.24 The level of care and maintenance that is to be provided for motor vehicles is outlined in the letter/s sent by AFSA engaging the agent to provide the storage facilities. For the aeroplanes in the custody and control of AFSA, AFSA sought expert advice on the care and maintenance required to preserve the aeroplanes. For the marine vessels that are currently in the custody and control of AFSA, the degree of maintenance required for the vessels has also been documented.

3.25 For motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes in the custody and control of AFSA, an annual valuation and inspection process is undertaken. As part of this exercise, the valuing agent provides confirmation that maintenance to preserve the motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes has been undertaken. For aeroplanes that are restrained a register is maintained at the premises where all work undertaken is noted and signed. A review by the ANAO of the storage and maintenance invoices for the motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes showed that the invoices noted what maintenance had been undertaken on the relevant motor vehicles or aeroplanes requested. For one of the marine vessels, the recommended annual change of engine oils has not occurred. The valuations carried out on these vessels based on the condition observed stated that minimal maintenance had been carried out on both vessels. For one of the vessels the valuation recommended that in order to achieve the maximum recovery value, considerable funds55 would need to be expended to restore the vessel to operational status.

Seized Cash

3.26 Where cash has been seized by the AFP or a state police force, and the court has directed that the value of the cash is to be placed into the custody and control of AFSA, the AFP or equivalent state police force transfers the value of the cash seized into the relevant account held by AFSA. Consequently, AFSA’s custody arrangements for seized cash are the same as for restrained bank account funds.

Jewellery

3.27 Jewellery placed into the custody and control of AFSA has usually been seized by the AFP or a state police force. Where the property is transferred into the custody and control of AFSA the jewellery is collected by AFSA case officers, escorted by AFP officers, and deposited into a safe deposit box held by AFSA.

Pre-forfeiture sale of property

3.28 Ordinarily, AFSA is unable to sell restrained property until after it has been forfeited to the Commonwealth or the owner has agreed to pre-forfeiture sale.56 AFSA can apply to the court under section 280 of the POCA to continue with a proposed disposal of property prior to forfeiture over the objection of the owner if it is uneconomical to continue to store and maintain the property. These circumstances include where AFSA considers that the property is likely to depreciate or the holding costs are likely to constitute a significant proportion of the value of the property.

3.29 A review of the 84 matters sampled by the ANAO identified 18 matters comprising 75 motor vehicles which had the potential to lose value through depreciation or where holding and maintenance costs were likely to represent a significant proportion of the value of the property. Across the 18 matters, three of the older matters, comprising 21 motor vehicles, marine vessels and aeroplanes have depreciated in value by an estimated $2.0 million while under restraint.57

3.30 AFSA was able to provide evidence in seven of the 18 matters that they had contacted the owner advising of their intention to dispose of the property. The owner/s objected to pre-forfeiture sale in three of these matters and no sale occurred at that point. In four out of the seven matters, one consented to pre-forfeiture sale, and for the remaining three matters the vehicle was repossessed by the financing company, was subsequently forfeited and sold, or the owner requested additional information regarding the reserve price to be set. For eleven matters, no records of AFSA seeking pre-forfeiture sale of the motor vehicle/s restrained were located.

3.31 From April 2016, AFSA has sought consent for pre-forfeiture sale of restrained property in a more regular and systematic manner.58 To help decide when to pursue pre-forfeiture disposal, AFSA has recently developed modelling tools to estimate future annual holding costs and forecast the progressive decline in property value through depreciation in order to demonstrate that it is no longer economical for AFSA to retain custody and control of the vehicle. AFSA has also instituted a test case to seek a court order for a pre-forfeiture sale over the objection of the owner. This is due to be heard in February 2017.

Is property managed in a way that is consistent with the relevant court orders?

AFSA manages property in a way that is consistent with the relevant court orders. Where consent, variation and/or exclusion orders are granted by the court, AFSA has acted consistently with the court order.

3.32 Once a restraining order has been granted either the AFP or the owner may apply for amendments to be made to the order. Examples of amendments sought can include: the release and/or exclusion of specified property from restraint; the release or exclusion of restrained property from the custody and control of AFSA; consent to sell restrained property; establishing conditions allowing restrained property to remain with the owner; and/or authorising the payment of living expenses or debts from restrained funds.

3.33 In the 84 matters sampled, 35 (42 per cent) have had consent, variation, and/or exclusion orders applied for and granted by the court. In all of the 35 matters AFSA, upon notification of the order has acted in accordance with directions of the court and in the timeframes specified in the court order.

Do AFSA’s disposal processes support the achievement of maximised sale proceeds from property forfeited?

In 2015–16, AFSA’s disposal processes have achieved sale proceeds from forfeited property which have exceeded the estimated value of the property in 76 per cent of matters, as determined by an independent and/or certified valuer, including all of the higher–value property.

3.34 Once property has been forfeited to the Commonwealth and AFSA has been advised by the AFP that any appeal period which applies has lapsed, AFSA is able to dispose of the property.

3.35 As part of the disposal process AFSA procures a valuation of the property prior to engaging an agent to assist with the sale. The ANAO’s review of relevant cases in the sample showed that in the case of real estate, a certified valuer is engaged to provide an at ‘arms-length’ valuation of the property. For other forms of property such as motor vehicles and jewellery, AFSA engages an agent to provide a valuation of the property and an agent to manage the sale of it. In the case of motor vehicles, valuations are either sourced from the agent storing the vehicles, or an independent valuer. In the case of jewellery, valuations have been commissioned from an agent or employee of the same entity ultimately engaged by AFSA to undertake the sale.

3.36 In terms of procuring an agent to handle the marketing and sale of the property, AFSA records demonstrate that it consistently obtains multiple quotes and evaluated each quote received to determine the best value for money option. When considering value for money AFSA addresses financial and non-financial criteria including the knowledge base, responsiveness, availability and reliability of prospective suppliers.

3.37 To test how effective AFSA’s disposal process is at maximising proceeds 21 finalised cases which included real estate, motor vehicles and/or jewellery were identified. Overall AFSA has achieved gross sale proceeds in excess of the valuation in 16 (76 per cent) of finalised cases.59 Of these 16 cases, five included real estate valued in excess of $1 million.

3.38 Out of the 21 matters, the sale proceeds failed to meet the expectations outlined in the accepted valuation on three occasions. In one of these matters the sale proceeds fell short of the valuation by more than $10 000.60 This matter involved the sale of high grade diamonds at auction, where the sale price was $16 500 below the valuation.

4. How funds from the Confiscated Assets Account are used

Areas examined

This chapter examines how, for the period 2010–11 to 2015–16, the Attorney–General’s Department (AGD) has identified options for the possible use of funds in Confiscated Assets Account, how it has advised the Minister for Justice on these options, and the main beneficiaries of funding.

Conclusion

The AGD has established effective processes to identify the possible use of funds from the Confiscated Assets Account. It has also advised the Minister for Justice on proposals to assist in achieving value for money from expenditure. During the financial years 2010–11 to 2015–16, the main beneficiaries of funding have been Commonwealth law enforcement and criminal intelligence agencies. Significant funding has also been approved for non-government, community organisation and local council projects, with the New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland police forces also receiving funding.

How does the Attorney–General’s Department identify the possible use of funds in the Confiscated Assets Account?

The processes through which the possible use of funds—stand-alone projects or grant programs—are identified and submitted for the Minister for Justice’s approval has evolved over time. In recent years, more structured and targeted processes have been implemented in order to assist in achieving better overall outcomes from Confiscated Assets Account funding.

4.1 The purposes for which funds in the Confiscated Assets Account may be used are prescribed by sections 297 and 298 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA). Section 297 mainly relates to various administrative matters that are closely connected with the operation of the POCA scheme, and are generally fairly modest amounts.61 Historically, the bulk of expenditure is under section 298, which provides that the relevant Minister (currently the Minister for Justice) may approve expenditure for the following purposes:

- crime prevention measures;

- law enforcement measures;

- measures relating to treatment of drug addiction; and

- diversionary measures relating to illegal use of drugs.

4.2 Funding under section 298 has been provided to a range of Commonwealth and state government entities, non-government organisations, community groups and local councils. The processes through which the possible use of funds—such as stand-alone projects, expansion or continuation of existing activities, or grant programs—are identified and subsequently submitted for the Minister’s formal approval has varied significantly in recent years. They have included:

- broader government decisions (including relating to election commitments);

- coordinated funding rounds for entities; and

- ad-hoc requests from Commonwealth and state entities and non-government organisations.

4.3 From 2011 through to 2014, the ANAO identified that the AGD provided written advice to the Minister on three occasions regarding improving the identification and funding processes in order to achieve better overall outcomes from section 298 expenditures. As part of this improvement process, the AGD commissioned a review by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), including an assessment of how non-government and community organisations had been funded. This review was commissioned in light of previous broadly-aimed funding rounds administered by the AGD that resulted in only 145 projects being funded from over 1800 non-government and community organisation applicants.

4.4 The AIC review recommended the adoption of more clearly defined funding priorities and a two–stream funding process: an open process for smaller community–based organisations; and a closed tender process to provide innovative solutions for specific crime prevention activities. Following that review, funding processes targeted towards non-government organisations, community groups and local councils have been more focussed. In 2013, the $38.0 million National Crime Prevention Fund was launched, which incorporated a mix of closed and competitive funding streams specifically targeting street and gang-related crime. In 2014, this funding was largely redirected into the Safer Streets programme, which had a similar focus and was also comprised of a mix of funding streams.

4.5 Until around 2011, government entity proposals seeking funding through section 298 had been dealt with on an individual basis. This meant that proposals were put forward by the AGD for ministerial consideration without the AGD necessarily having any knowledge of what other proposals might be being developed by other entities for possible section 298 funding. Some improved coordination measures were introduced in 2011, and in 2014 the Minister approved a more competitive bi–annual process. This revised process involved the AGD inviting Commonwealth and state entities to submit proposals which would then be assessed against generic funding guidelines. This approach has the advantage of enabling comparisons of the relative merits of different proposals.62 After the Minister short-lists preferred proposals, these are subject to a costing agreement process by the Department of Finance before being resubmitted to the Minister for final approval.

4.6 Some relatively large government entity projects have been funded outside of the bi-annual process. These include $14.7 million to expand the Australian Federal Police (AFP)–led Fraud and Anti-Corruption Centre. This funding was approved in May 2016.

Does the Attorney-General’s Department provide the Minister for Justice with relevant advice on the proposals?

The AGD provided the Minister with relevant advice to assist him in meeting his decision-making obligations.

4.7 The ANAO reviewed the AGD’s advice relating to 44 proposals for stand-alone projects or grant programs which the Minister approved during 2010–11 to 2015–16. Before formally approving funding via a signed section 298 ‘expenditure instrument’, the Minister received written advice on the relevant proposal in all cases. The advices provided assurance that the proposals were consistent with the purpose of section 298. Most commonly this was through either a clear statement that the proposal was consistent with section 298, or that it had been assessed as being eligible for funding under generic or specific guidelines attached to the advice.63 These guidelines contained an extract from section 298. All of the more recent advices contained information on the Minister’s decision-making responsibilities under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, including the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

4.8 The advices reviewed by the ANAO also provided information on the amount of uncommitted funds in the Confiscated Assets Account and any other financial information that might constrain the Minister’s ability to fund further proposals. Where the advice involved multiple government entity proposals generated through a coordinated funding round, the advice included commentary on the merits of each proposal, although did not always provide specific recommendations or rank the proposals.

4.9 In the majority of cases the Minister followed the AGD’s funding recommendations, however four cases were identified where the Minister did not fund all recommended projects, or agreed to fund the projects for a lower amount.

4.10 Until late 2015, the AGD did not recognise that funding state police proposals would constitute a grant. As a result, the AGD had not developed specific ‘one-off’ grant guidelines against which the relevant proposal could be assessed and inform the advice provided to the Minister. The development and use of such guidelines were mandatory requirements under the 2013 Commonwealth Grant Guidelines and 2014 Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines.

4.11 An example of this occurred in June 2015, when after receiving advice from the AGD; the Minister approved $3.3 million of funding to the NSW police for its continued involvement in the joint Commonwealth–NSW Polaris waterfront crime taskforce. The Minister wrote to the NSW Police Commissioner notifying him of his decision. The AGD subsequently recognised that such funding was in fact a grant. It then developed ‘one-off’ grant guidelines and in December 2015 asked the Minister to approve the guidelines and re-confirm his funding approval. The funding was then provided to the NSW police. Subsequent advice regarding similar proposals have complied with the mandatory requirements of the 2014 Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines.

4.12 Where relevant, the Minister was also provided advice on the legal risks involved in grant programs arising from the High Court’s decision in the Williams case.64 Options for mitigating risk were also canvassed.

Who have been the main beneficiaries of funding from the Confiscated Assets Account?

The main beneficiaries of funding from the Confiscated Assets Account have been Commonwealth criminal intelligence or law enforcement entities. Significant funds have been approved for non-government, community organisations or local council’s projects, mainly through the Safer Streets Programme. The New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland police forces have also received funding.

4.13 From the 2010–11 to 2015–16 financial years the Minister for Justice approved $161.0 million in funding under section 298. This figure excludes approximately $54.8 million where the approval was subsequently reversed by the Minister and the funds were not paid.65

4.14 For Commonwealth criminal intelligence or law enforcement entities, $86.7 million was approved, mainly to the AFP ($51.3 million) and the Australian Crime Commission66 ($28.9 million). Of the funding going to the AFP and the Commission, $30.0 million wholly or partly supports these entities’ proceeds of crime operations. A breakdown is provided in Table 4.1.

4.15 A total of $21.6 million in funding was approved for the New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland police forces to support their involvement in separate Commonwealth–State taskforces targeting waterfront crime. A breakdown is provided in Table 4.1. Of this, $12.0 million went to New South Wales, on the condition that the proceeds from property confiscated through the Polaris taskforce operations was to be transferred back to the Commonwealth under an equity sharing arrangement. As at 30 June 2016, New South Wales had transferred $1.1 million. In addition, property with an estimated value of $3.7 million has been forfeited directly to the Commonwealth through POCA litigation, with a further $6.6 million of property restrained by the Commonwealth but not yet forfeited.

Table 4.1: Funding to Commonwealth and state entities

|

Recipient |

Project(s) |

Total funding ($ million) |

|

Australian Federal Police |

Criminal assets confiscation taskforce; anti-gang squads; aerial surveillance capability; fraud and anti-corruption centre; big data visualisation capability |

51.32 |

|

Australian Crime Commission |

Criminal assets confiscation taskforce; criminal intelligence database and information-sharing systems; anti-money laundering; secondments to overseas agencies; waste water analysis capability; mobile surveillance capacity; national organised crime taskforce |

28.99 |

|

NSW Police |

Polaris waterfront crime taskforce |

12.00 |

|

Victorian Police |

Trident waterfront crime taskforce |

8.14 |

|

Australian Transactions and Reports Centre |

Enhanced registration system for financial remittance providers |

2.95 |

|

Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity |

Surveillance capacity enhancement pilot project |

2.65 |

|

Queensland Police |

Jericho waterfront crime taskforce |

1.50 |

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

Anti-corruption policy statement |

0.74 |

Source: AGD submissions to Minister for Justice.

4.16 $52.7 million was approved for projects to be undertaken by non-government or community organisations or local councils, across a wide variety of activities. The majority ($37.4 million) of this funding was under the two funding rounds of the Safer Streets programme.

Table 4.2: Funding to non-government and community organisations and local councils

|

Recipient |

Project(s) |

Total funding ($ million) |

|

Various local councils and non-government and community organisations (including Neighbourhood Watch Australasia and Youth off the Streets) |

Enhancing security and safety of community through improved environmental design; closed circuit TV monitoring; security infrastructure; lighting and early intervention and crime prevention activities (Safer Streets programme) |

37.4 |

|

Youth Off the streets |

Early intervention outreach activities (National Crime Prevention Fund) |

5.0 |

|

Various local councils and non-government and community organisations |

Graffiti Prevention |

3.0 |

|

Police-citizens youth clubs / Blue Light organisations |

Early intervention outreach activities |

1.9 |

|

Anti-Slavery Project; Australian Catholic Religious Against Trafficking Humans; Project Respect and Scarlet Alliance |

Various anti-people trafficking activities |

1.6 |

|

Neighbourhood Watch Australasia |

Establish national office and undertake various activities with police and communities |

1.5 |

|

Various non-government and community organisations |

Improve security and domestic violence crisis accommodation facilities |

1.0 |

|

Crime Stoppers |

Dob-in-a-dealer |

1.0 |

|

Firearm Safety Foundation Victoria |

Improve firearm safety |

0.3 |

Source: AGD submissions to Minister for Justice.

4.17 Information on projects funded under section 298 is available from the AGD’s annual reports and grant register. For 2015–16, all government–entity projects funded, and total funding amounts are set out in the 2015–16 annual report. Information on the Safer Streets Projects is available from the AGD’s grant register.

5. Performance Monitoring and Reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examines the various performance-related monitoring and reporting undertaken by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) pursuant to their respective roles under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 ( POCA).

Conclusion

The AFP publicly reports the estimated recovery value of property restrained each year. When combined with the Australian Crime Commission’s (ACC’s)67 public reporting of the estimated value of property confiscated each year, this illustrates the trends in the amount of criminal proceeds intercepted by the POCA scheme.

AFSA also undertakes limited public reporting on its administration of property. This reporting does not include information on the costs of administering property under its custody and control, which is an important aspect of its overall performance in relation to the proceeds of crime. However, AFSA has made some improvements in its internal reporting capacity about the costs of managing property and is in the early stages of developing benchmarks for some aspects of these costs.

Does the AFP appropriately monitor and report on its performance?

The AFP publicly reports on the estimated recovery value of property restrained each year and whether the AFP has met the benchmark set for that year. It also internally monitors another key performance measure—the estimated value of property confiscated each year—which is publicly reported by the ACC. These two measures illustrate the trends in the criminal proceeds intercepted by the POCA scheme. In the context of a current AFP-wide review of performance measures, additional metrics could be developed to provide better information on the AFP’s performance in litigating POCA cases and, in the longer term, the effect of the POCA scheme on the underlying criminal economy.

5.1 Through the Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce (CACT), the AFP has a key role in investigating and identifying property potentially subject to restraint and confiscation under the POCA. The AFP Criminal Assets Litigation (CAL) team then has responsibility for obtaining the relevant POCA court orders to give effect to the Taskforce’s decisions.

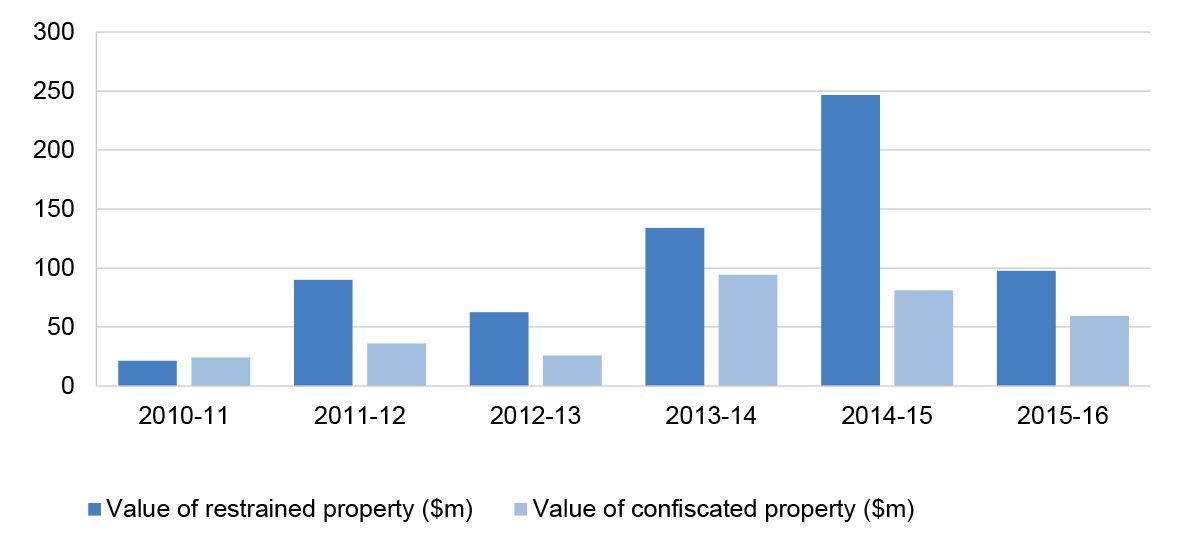

5.2 The AFP publicly reports on the estimated recovery value of property restrained each financial year. This provides an indication of the AFP’s success in, at least temporarily, depriving persons of the proceeds or instruments of suspected or proven criminal activity and preventing possible reinvestment of these in further criminal enterprises. The AFP’s current performance measure for POCA matters is that the value of restrained property for the relevant year is higher than the annual average for the previous five years. With this average increasing from $65.6 million to $111.1 million due to the record amount restrained in 2014–1568, the amount restrained in 2015–16 ($96.5 million) meant the AFP did not meet this performance measure. The AFP’s annual report states that the spike in restrained property in 2014–15 and the complex nature of the relevant cases has ‘had a direct impact on [the taskforce’s] capacity to pursue new restraint action in 2015–16’.

5.3 The AFP commenced internal reporting on the value of confiscated property from 2014.69 The ACC, a member of the CACT, publically reports on both the value of restrained and confiscated property.