Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Probity Management in Rural Research and Development Corporations

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

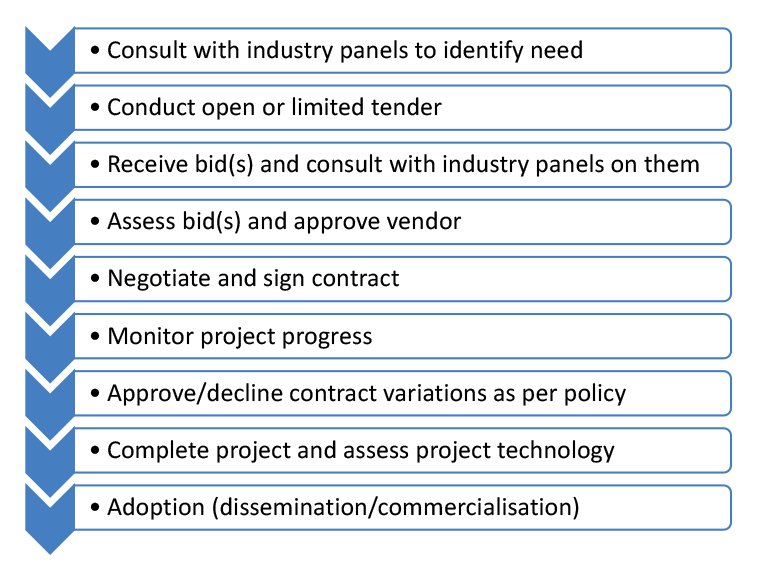

- Research and development corporations (RDCs) work closely with industry in purchasing research, development and extension (RD&E) services.

- As a result of the close relationship with industry, probity risks are high.

- Very high levels of probity are expected of the five RDCs, as they spend taxpayer and industry money.

Key facts

- The RDCs purchased $285 million of RD&E in 2017–18 to benefit industry and the wider community.

- The corporations' funds are sourced from levy payers. The Australian Government matches these amounts up to certain limits.

- The corporations' research is often made freely available to producers. Sometimes it is legally registered and commercialised. The RDCs receive $7.6 million of royalties annually.

What did we conclude?

- The Cotton RDC was largely able to manage probity across its RD&E procurements, conflicts of interest, gifts, benefits and hospitality, intellectual property, and credit cards.

- AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries and Grains RDCs, and Wine Australia partially did so.

- Wine Australia had the most significant shortcomings in how it managed probity.

What did we recommend?

- The boards at three RDCs take responsibility for policies on ethics, RD&E procurement and intellectual property.

- Two RDCs fully reflect the law in their conflicts policies.

- Two RDCs set up ways to receive probity allegations from the public.

- The corporations except for the Cotton RDC do more probity training.

- The RDCs accepted all recommendations.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Rural research and development corporations (RDCs) purchase research, development and extension (RD&E) services for the benefit of the industry and wider community. The RDCs are partly funded through industry levies, which the Commonwealth matches up to certain limits.1

2. Five corporations are corporate Commonwealth entities. These are AgriFutures Australia (open to all agricultural industries), the RDCs for Cotton, Fisheries and Grains, and Wine Australia.2 Industries own another 10 RDCs, which were outside the scope of the audit.

3. The RDCs often target their projects at increased productivity and competitiveness through new breeds, varieties and production technologies. Examples are: collecting and analysing data to improve crop management; developing new herbicides; and researching animal vaccines to reduce production losses. Funded projects can also have environmental and social outcomes, such as reduced pesticide use and reduced food-borne illness.

4. The Acts establishing the corporations require the Minister to declare at least one industry body for each corporation as a representative organisation. These declared bodies are involved in the appointment of directors, the corporations’ planning, and other activities.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. It is critical that the corporations uphold high probity standards given their often close interactions with a small number of researchers over time, and potential conflicts arising from the corporations’ directors being industry representatives themselves. Total expenditure for the corporations in 2017–18 was $359 million and the audit was designed to provide assurance that RDCs are appropriately managing public funds in terms of probity risks. RDCs were last involved in a performance audit in 1998. The findings can provide lessons for future funding agreements managed by the Department of Agriculture, and the corporations can adopt examples of better practice highlighted in the audit.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the rural research and development corporations’ management of probity. The audit criteria were:

- do the corporations have appropriate probity arrangements?

- have the corporations complied with applicable probity requirements?

7. Effectively managing probity requires RDCs to have high levels of compliance with appropriate probity arrangements.

Conclusion

8. In managing probity issues, the Cotton RDC was largely effective and AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries and Grains RDCs and Wine Australia were partially effective. Wine Australia had the most significant shortcomings in effectiveness.

9. The corporations’ probity arrangements in relation to governance, policies and internal controls were largely appropriate, except for Wine Australia whose arrangements were partially appropriate.

10. The Cotton RDC effectively complied with its applicable probity requirements, while the other four corporations partially complied with Wine Australia the least effective.

Supporting findings

Do the corporations have appropriate probity arrangements?

11. The board’s governance arrangements at the Cotton RDC were effective in promoting probity. The arrangements at AgriFutures Australia and the Fisheries and Grains RDCs were largely effective in promoting probity, while the arrangements at Wine Australia were partly effective in promoting probity.

12. The corporations’ boards have approved charters or policy frameworks that allocate responsibility for approving probity policies, except for Wine Australia. These four boards have retained responsibility for policies around standards of behaviour. Reporting to the five corporations’ boards about gifts, benefits and hospitality and probity incidents was appropriate. The Grains RDC can improve reporting to the board on compliance with RD&E procurement policies, noting that all procurement during the audit period was delegated to management. The five corporations, except for the Cotton RDC, can improve reporting to the board on conflicts of interest. The corporations’ boards established policies and frameworks to enable them to oversight probity risks. The boards at AgriFutures Australia and the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs met legal requirements for risk reporting; the two other corporations did not and also had scope to improve their risk registers.

13. Four corporations’ policies were largely appropriate in promoting probity in funding decisions, and managing intellectual property and credit cards, while Wine Australia’s policies were partially appropriate. Areas for improving or reviewing policies were:

- contract variations, for all five corporations;

- reflecting the legal requirements for conflict of interest for the Cotton RDC and Wine Australia;

- providing RD&E funding to industry bodies, for all five corporations;

- for giving and receiving gifts, for all five corporations;

- reviewing credit card transactions, for all five corporations; and

- promoting reasonable competition, for Wine Australia.

14. The five RDCs have developed systems of internal control that are largely appropriate for their probity requirements. Key measures include: fraud control plans; internal audit programs to confirm compliance with probity policies; and training on probity issues. Areas for improvement included:

- establishing a mechanism for the public to confidentially report fraud and probity allegations, for the Cotton and Grains RDCs and Wine Australia;

- Wine Australia to consider including fraud as a topic in its internal audit program, and fully comply with the 10 legislated requirements for fraud control; and

- increased training on probity policies, for AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries and Grains RDCs, and Wine Australia.

15. Six allegations of non-compliance related to probity were reported to the RDCs in the two-year period to 31 December 2018, with five of the six addressed and managed effectively. The Grains RDC did not document investigating or finalising one allegation beyond initial scoping.

Have the corporations complied with applicable probity requirements?

16. The Cotton RDC complied with its probity policies in making funding decisions and managing intellectual property. The other four corporations partially complied. These corporations fully complied with their conflict of interest policies at the board level but there was incomplete evidence of implementation of this policy for panels and staff. AgriFutures Australia complied with its key policies for documenting the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality; Wine Australia partially did so; and the Fisheries and Grains RDCs did not. The Grains RDC largely complied with its policies for managing intellectual property in contracts and the other three RDCs partially complied.

17. The Cotton RDC largely demonstrated a focus on value for money in approving projects and varying contracts. AgriFutures Australia and the Fisheries and Grains RDCs partially did so; their exceptions were generally due to lack of documentation. For one project, management at the Fisheries RDC breached policy by approving a project that they anticipated would go to the board for a large variation. With limited policies, Wine Australia largely documented the development of its five major RD&E agreements and partially documented variations. For the grants projects tested, the Grains RDC and Wine Australia demonstrated a focus on value for money by having good processes and documentation. Wine Australia was also required to comply with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines for these grants and largely did so.

18. Implementation of credit card controls was effective at the Cotton RDC, largely effective at the Grains RDC, and partially effective at the other corporations. AgriFutures Australia and Wine Australia were not able to provide supporting documentation for a number of large transactions (three and two respectively). Weaknesses in credit card control processes represent substantial probity risks for AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries RDC and Wine Australia.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.11

In respect of board charters:

- AgriFutures Australia amends its charter to specify that the board is responsible for approving probity policies relating to ethics, procurement and intellectual property;

- the Grains RDC amends its charter to specify that the board is responsible for policies relating to procurement and intellectual property, and also ensures that policy approval is consistent with its charter; and

- Wine Australia, when approving a new charter, specifies that the board is responsible for policies on ethics, procurement and intellectual property.

AgriFutures Australia response: Agreed.

Grains RDC response: Agreed.

Wine Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.38

The Cotton RDC and Wine Australia revise their conflict of interest policies to fully reflect legal requirements.

Cotton RDC response: Agreed.

Wine Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.83

The Cotton and Grains RDCs both establish a mechanism for the general public to report fraud allegations.

Cotton RDC response: Agreed.

Grains RDC response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.95

AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries and Grains RDCs, and Wine Australia increase the scope, frequency and mandatory nature of their probity training to increase compliance with applicable requirements.

AgriFutures Australia response: Agreed.

Fisheries RDC response: Agreed.

Grains RDC response: Agreed.

Wine Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

19. A summary response from the Cotton RDC is below. All five RDCs provided full responses, which are in Appendix 1.

Cotton RDC

The Cotton Research and Development Corporation (CRDC) welcomes the ANAO’s report on probity management in rural research and development corporations. CRDC is committed to continuous improvement in our governance culture. CRDC is a micro‐agency that aims to adopt governance systems that are agile, fit for purpose and enhance performance. CRDC accepts the recommendations of the ANAO contained in the report and notes the general findings that encourage CRDC to continue to review and enhance CRDC’s policies, accountable authority instructions, risk management framework and practices.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant to the management of probity in other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Procurement

Policy/program implementation

Records management

1. Background

Rural research and development corporations

1.1 Rural research and development corporations (RDCs) engage with research organisations to deliver research, development and extension (RD&E) services for the benefit of the industry and wider community. The RDCs are partly funded through industry levies, which the Commonwealth matches up to certain limits.3

1.2 In 2019 there were 15 RDCs, of which five were statutory and 10 industry-owned (see Table 1.1). The statutory RDCs have legislated levies, which are compulsory for industry participants.4

Table 1.1: Statutory and industry-owned rural research and development corporations

|

Statutory |

Industry-owned |

|

|

Source: Department of Agriculture, Rural Research and Development Corporations. Available from: http://www.agriculture.gov.au [accessed 28 May 2019].

1.3 The establishing legislation for AgriFutures Australia and the Cotton, Fisheries and Grains RDCs is the Primary Industries Research and Development Act 1989 (the PIRD Act). The fifth statutory RDC, Wine Australia, was created under the Wine Australia Act 2013, to merge the Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation and the Wine Australia Corporation.

1.4 The two establishing Acts provide that the RDCs can only spend monies received from the Commonwealth if they comply with a written funding agreement. The corporations signed four-year agreements with the Commonwealth in June 2015 and extended them in June 2019 until December 2019, or until the execution of a new agreement. The agreements reinforce compliance with obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and the respective establishing Act. The agreements also require the RDCs to undertake a performance review.

1.5 The establishing Acts require the Minister to declare at least one industry body for each corporation as a representative organisation. These declared bodies are involved in the appointment of directors, must be consulted during the corporations’ planning, can be reimbursed for reasonable consultation expenses, must receive certain types of reports and plans, and must be able to meet with the corporation annually.

Research, development and extension activities

Functions and powers

1.6 The four RDCs’ functions under section 11 of the PIRD Act include preparing research and development plans and annual operational plans, coordinating and funding research and development activities consistent with the annual operating plan, disseminating and commercialising the research and development, and arranging marketing.5 The RDCs have powers under section 12 to do anything necessary or convenient for the purpose of these functions, including buying, holding and selling all types of property.

1.7 Wine Australia’s functions under section 7 of the Wine Australia Act 2013 include coordinating or funding wine and grape research and development, disseminating, commercialising and promoting the adoption of this work, marketing grape products and controlling the export of grape products. Its functions do not include conducting research and development. Section 8 gives Wine Australia the power to do all things necessary or convenient to perform its functions.

1.8 Examples of research projects that the corporations are funding are:

- AgriFutures Australia is providing $226,000 to co-fund with the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries a project to develop a visual guide to litter management for chicken meat producers to improve their management of litter;

- the Cotton RDC is providing $705,000 and $124,000 in-kind to co-fund with the CSIRO a project to model and assess cotton quality using spatial data to improve crop management;

- the Fisheries RDC provided $1.7 million to co-fund the Australian Aquatic Animal Health and Vaccine Centre with the Tasmanian Government, the Tasmanian Salmonid Growers’ Association and the Seafood Co-operative Research Centre to conduct salmon vaccine research to reduce production losses through disease;

- the Grains RDC is providing $45 million over five years to Bayer to support the development of new herbicides6; and

- Wine Australia is providing $12.1 million to the Australian Wine Research Institute over five years to conduct seven research projects into wine texture, taste, quality and the effects of soil and climate.

Outcomes

1.9 In its 2011 report, the Productivity Commission noted that the rural RD&E sector had reported the following benefits from RD&E:

- increased productivity and competitiveness through new breeds, varieties and production technologies;

- environmental outcomes such as reduced pesticide use, improved fire management in forests and use of trees in urban areas to mitigate climate change; and

- social outcomes including reduced food borne illness, business opportunities for Indigenous Australians, and improved livestock welfare.7

1.10 The Productivity Commission stated that these categories are not separate and that the interests of consumers and producers are often linked. Improved livestock welfare could improve or maintain demand for the product, for example.8

1.11 The Council for Rural Research and Development Corporations is the sector’s peak body. The Council has overseen the production of impact assessment materials that the corporations use to conduct or commission cost benefit analysis of RD&E projects.9 The Council commissioned a 2016 study that collated individual impact assessments across the corporations. It found, for 167 projects in randomly submitted project groups across nine corporations, a weighted present value cost/benefit ratio of 1 to 4.5 for RDC funded projects.10

Governance

1.12 The PGPA Act and the two establishing Acts set out the corporations’ governance structure. Section 16 of the PIRD Act provides that each corporation is constituted by a Chairperson (who is a director), an Executive Director (the chief executive officer) and five to seven other directors. Sections 17 and 77 provide that the Minister appoints the directors, except the Executive Director, whom the directors appoint. Section 13 of the Wine Australia Act 2013 states that Wine Australia comprises the directors only. The Minister appoints the directors under section 14. Wine Australia has a general power to appoint employees, including the principal employee, under section 30.

1.13 The directors appointed by the Minister comprise the corporations’ governing bodies.11 For corporate entities, section 12 of the PGPA Act provides that the accountable authority of an entity is its governing body.

The board’s role in promoting probity

1.14 The PGPA Act places a number of duties on accountable authorities. Section 15 requires each accountable authority to promote the proper use of public resources. Section 26 requires officials of corporations (both directors and staff) to act for a proper purpose. Section 8 defines ‘proper’ as efficient, effective, economical and ethical. There are broad probity obligations on the directors (and staff) of the corporations. The boards must fulfil their governance role, including in relation to probity matters.

1.15 Major Australian corporate governance reviews have included the 2003 Royal Commission into HIH Insurance, the 2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and the 2019 Royal Commission into the financial services industry. These reviews have discussed the importance of the ‘soft’ aspects of governance, in particular organisational culture. Their findings included that the corporations’ boards were not receiving appropriate information and had accepted management’s representations instead of forming an independent opinion.12

1.16 These issues were discussed in the introduction to the performance audit report, Effectiveness of Board Governance at Old Parliament House. The report noted that current guidance for accountable authorities focuses on legal compliance and Commonwealth boards do not have guidance along the lines of the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations and the Australian Institute of Company Directors’ resources. The report recommended that the Department of Finance update its guidance to incorporate lessons learnt from wider governance reviews. The department accepted the recommendation, noting that it reflected work underway.13

1.17 In order to fulfil their governing role in relation to probity, the corporations’ accountable authorities would be expected to set out roles and reporting within the corporation, approve and review probity policies, ensure they are informed about the corporation’s activities, act on information promptly, and take an active role when working with management.

Profile of the corporations

1.18 The corporations have similar frameworks but differ in relation to their industries, size and other arrangements. Key points about individual corporations are:

- AgriFutures Australia is responsible for industries related to buffalo, goat fibre, honey, kangaroo and wallaby, meat chicken, pasture seed, rice, deer, ostrich, ginger, fodder, tea tree oil and thoroughbred horses, as well as new and emerging industries such as hazelnut, goat milk and hemp. The RDC supports industries that do not have their own research and development function, new and emerging industries, and issues that affect the whole of agriculture.

- The Cotton RDC is responsible for industries related to cotton fibre and seed cotton.

- The Fisheries RDC is responsible for Australian fishing and aquaculture related to all living aquatic natural resources in Australian rivers, estuaries and the sea.

- The Grains RDC is responsible for industries related to wheat, coarse grains, pulses and oilseeds.

- Wine Australia is responsible for industries related to grapes and wine. In addition to RD&E, the corporation regulates the export of wine and the geographical indicators on Australian wine, and conducts wine marketing. From 2018 to 2020 Wine Australia is also administering the Export and Regional Wine Support Package that includes export and regional tourism grants, training and export marketing.

1.19 The differences between the corporations give them different profiles for probity risk. For example, Wine Australia undertakes marketing, which may increase risk around the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality. A common risk for the entities is achieving value for money when procuring RD&E due to the specialised nature of the work in some cases and the resulting lack of competition. Another common risk is that conflicts of interest may arise due to the corporations’ links with industry.

1.20 The corporations’ operations are compared in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Comparison of the operations of the corporations, 2017–2018

|

Corporation |

Program spending |

Total expenses |

Royalty revenue |

Representative organisations |

Locations |

|

AgriFutures Australia |

$21.4m |

$28.2m |

$0.4m |

Australian Chicken Meat Federation National Farmers’ Federation |

Wagga Wagga |

|

Cotton RDC |

$21.6m |

$25.1m |

$1.2m |

Cotton Australia |

Narrabri |

|

Fisheries RDC |

$26.0m |

$31.4m |

Nil |

Commonwealth Fisheries Association National Aquaculture Council RecFish Australia Seafood Industry Australia |

Adelaide, Canberra, and Port Stephens |

|

Grains RDC |

$192.1m |

$219.8m |

$6.0m |

Grain Growers Limited Grains Producers Australia Limited |

Adelaide, Canberra, Perth and Toowoomba |

|

Wine Australia |

$36.2m |

$54.4m |

Nil |

Australian Grape and Wine Incorporated |

Adelaide, London, San Francisco, Shanghai, Sydney and Vancouver |

Note: Wine Australia’s program spending includes $12.0 million in marketing expenditure, which the other entities do not engage in. Its overseas operations are managed by subsidiary corporate bodies.

Source: The corporations’ 2018 annual reports. Department of Agriculture, Rural Research and Development Corporations [Internet], 2019, available from: http://www.agriculture.gov.au [accessed 28 May 2019].

1.21 AgriFutures Australia relocated from Canberra to Wagga Wagga at the end of 2016. The corporation advised that, of its current personnel of 35, only two remain from the Canberra staff. The RDC also advised that its corporate and research teams in Wagga Wagga were under-resourced during establishment in that city.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.22 It is critical that the corporations uphold high probity standards given their often close interactions with a small number of researchers over time, and potential conflicts arising from the corporations’ directors being industry representatives themselves. Total expenditure for the corporations in 2017–18 was $359 million and the audit was designed to provide assurance that RDCs are appropriately managing public funds in terms of probity risks. RDCs were last involved in a performance audit in 1998.14 The findings can provide lessons for future funding agreements managed by the Department of Agriculture, and the corporations can adopt examples of better practice highlighted in the audit.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.23 The audit assessed the effectiveness of the rural research and development corporations’ management of probity.

1.24 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, two high-level criteria were adopted:

- do the corporations have appropriate probity arrangements?

- have the corporations complied with applicable probity requirements?

Accordingly, effective management of probity requires RDCs to have high levels of compliance with appropriate probity arrangements

1.25 The audit examined probity processes and compliance with those processes in 2017 and 2018 for the five rural research and development corporations that are Commonwealth entities. The audit report focuses on practices and processes in place in those two years. Each of the five RDCs was responsive to issues raised during the audit, and sometimes had separate processes to review probity policies and practices, and accordingly made a number of improvements to their management of probity in 2019. Some of these improvements are recognised in the report, but not all to reflect the primacy of the audit testing results and for the sake of reporting clarity.

1.26 The audit mainly addressed five probity themes: conflict of interest; gifts, benefits and hospitality; value for money in spending program funds, especially in relation to RD&E; intellectual property; and credit cards.

1.27 The audit did not examine Wine Australia’s regulatory activities. The audit also did not examine the 10 industry-owned corporations that have funding arrangements with the Department of Agriculture.

Audit methodology

1.28 Audit procedures included:

- examining the entities’ board documents, policies, risk assessments, internal audit records and compliance records;

- testing procurements, gifts and credit card records against entity policies and better practice standards;

- interviews with Chairs, Audit Committee Chairs, and senior staff at the corporations; and

- interviews with selected industry organisations.

1.29 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $625,000.

1.30 The team members for this audit were David Monk, Irena Korenevski, Anne Kent, David Willis, Danielle Page, William Richards and Andrew Morris.

2. Do the corporations have appropriate probity arrangements?

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the research and development corporations have established appropriate frameworks to ensure that the board and staff conduct their affairs with probity. The audit reviewed the corporations’ governance, in particular board practices, reporting to the board and risk management. The chapter also examines the corporations’ probity policies and internal controls.

Conclusion

The corporations’ probity arrangements in relation to governance, policies and internal controls were largely appropriate, except for Wine Australia whose arrangements were partially appropriate.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations directed at particular corporations designed to: improve their governance frameworks for probity (paragraph 2.11); improve their policies for conflicts of interest (paragraph 2.38); increase their mechanisms for receiving tip-offs about possible fraud (paragraph 2.83); and improve probity training (paragraph 2.95).

The ANAO made a number of suggestions for particular corporations to incorporate better practices into their policies, including to: specify the management of declared interests (paragraph 2.42); set appropriate reporting threshold for gifts, benefits and hospitality received and offered (paragraph 2.49); cover the receipt of hospitality when undertaking official business (paragraph 2.50); require management to brief the board on the tender method before it approves a procurement (paragraph 2.57); and cover the assessment of variations (paragraph 2.59).

2.1 The accountable authority of each research and development corporation (RDC) is the board. Section 15 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires the accountable authority to govern the entity in a way that promotes economy, effectiveness, efficiency and ethics. The sub-criteria in this chapter trace how the boards exert their authority over the RDCs, starting with their own governance, then the policies they approve or delegate, and finally how they ensure compliance with policy through internal controls.

Do the boards’ governance arrangements promote probity?

The board’s governance arrangements at the Cotton RDC were effective in promoting probity. The arrangements at AgriFutures Australia and the Fisheries and Grains RDCs were largely effective in promoting probity, while the arrangements at Wine Australia were partly effective in promoting probity.

The corporations’ boards have approved charters or policy frameworks that allocate responsibility for approving probity policies, except for Wine Australia. These four boards have retained responsibility for policies around standards of behaviour. Reporting to the five corporations’ boards about gifts, benefits and hospitality and probity incidents was appropriate. The Grains RDC can improve reporting to the board on compliance with RD&E procurement policies, noting that all procurement during the audit period was delegated to management. The five corporations, except for the Cotton RDC, can improve reporting to the board on conflicts of interest. The corporations’ boards established policies and frameworks to enable them to oversight probity risks. The boards at AgriFutures Australia and the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs met legal requirements for risk reporting; the two other corporations did not and also had scope to improve their risk registers.

2.2 The corporations’ boards are responsible for the corporations’ governance under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the Primary Industries Research and Development Act 1989 (PIRD Act) and Wine Australia Act 2013. Section 15 of the PGPA Act requires the board, as the accountable authority, to promote the proper use and management of the public resources for which it is responsible. This would include mandating particular conduct and receiving sufficient reporting to be informed that it occurs. ‘Proper’ includes probity because the PGPA Act defines it as efficient, effective, economical and ethical.

2.3 The corporations’ status as corporate Commonwealth entities means they have more discretion in how they conduct their affairs than non-corporate Commonwealth entities.

Did the boards establish appropriate governance frameworks for probity?

2.4 One way in which boards establish a governance framework is through a board charter that sets out the functions, roles, powers and membership of the board.15 All the corporations had a charter except for Wine Australia, which has subsequently prepared one that is awaiting board approval. While recognising the clarity provided by a charter, Wine Australia advised that the roles of the board, its committees and staff were well understood at the time of the audit, but did not provide supporting documentary evidence.

2.5 A board would typically be responsible for the entity’s statement of values, which would include proper standards of behaviour.16 The boards at the Cotton, Fisheries and Grains RDCs used their charters to either affirm their commitment to ethical standards or acknowledge the board’s role in ensuring the entity conforms to them. The charter at AgriFutures Australia required the directors to uphold certain ethical standards but did not comment on the ethical standards required at the corporation generally. Management set the ethical standards required of staff.

2.6 A board can use its charter to delegate responsibility for policies to management, including probity policies. The boards for the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs used their charters to retain responsibility for all policies. The board of the Grains RDC has approved a policy framework that reserves to it governance policies that cover areas such as standards for behaviour, financial limits, and external reporting. Additional to its charter requirements, this board approved its intellectual property policy. The charter for AgriFutures Australia reserves strategic policies for the board and delegates operational policies to the Executive Director, which does not make clear whether the board has retained responsibility for probity policies.17

2.7 Seven probity policies were tested to determine whether board practices of approval and review were consistent with their charters for the Cotton, Fisheries and Grains RDCs:

- five directly related to statutory standards of conduct under the PGPA legislation: ethics; use of position; use of information; disclosure of interests; and fraud18; and

- two related to the corporations’ key activities: the procurement of research and development; and the management of intellectual property and project technology.19

2.8 Under their charters, the three relevant boards were expected to approve the five policies relating to standards of conduct. The boards of the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs did so. The board of the Grains RDC approved policies for use of position, disclosure of interests and fraud, but not for ethics or use of information. The boards of the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs were expected to approve the policies for procurement and intellectual property, which the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs did.

2.9 There are opportunities for improvement in how the corporations’ boards manage probity policies. The board of AgriFutures Australia can take responsibility for policies around ethics, which would be consistent with generally recognised governance principles. The boards of AgriFutures Australia and the Grains RDC should approve their policies for procuring RD&E and managing intellectual property, given the importance of these areas to the entities. The board at Wine Australia should also take responsibility for these matters when it receives the draft charter developed by management.20 The board of the Grains RDC can approve all its policies for ethics, as required by its charter.

2.10 The boards of the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs effectively managed their charters and complied with them when approving probity policies.

Recommendation no.1

2.11 In respect of board charters:

- AgriFutures Australia amends its charter to specify that the board is responsible for approving probity policies relating to ethics, procurement and intellectual property;

- the Grains RDC amends its charter to specify that the board is responsible for policies relating to procurement and intellectual property, and also ensures that policy approval is consistent with its charter; and

- Wine Australia, when approving a new charter, specifies that the board is responsible for policies on ethics, procurement and intellectual property.

AgriFutures Australia response: Agreed.

2.12 The Board resolved at the September 2019 Board meeting to reserve the power to approve all policies commencing with the Governance Policies in December 2019. The Board Governance Manual and Audit Committee Charter were revised and updated in November 2019 and approved by the Board on 4 and 5 December 2019.

Grains RDC response: Agreed.

Wine Australia response: Agreed.

2.13 The Wine Australia Board has approved a new Board Charter that specifies that the Board is responsible for policies on ethics, procurement and intellectual property.

Did the boards receive appropriate reporting on probity?

2.14 Section 15 of the PGPA Act requires the boards, as the accountable authority, to promote the economical, effective and efficient use of public resources. To implement this requirement, the boards can receive reporting on probity topics proportionate to risk as well as on confirmed probity incidents. Reporting to the board was examined for: procurement; conflicts of interest; the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality; and credit cards.

Procurement

2.15 Progress reporting to the boards on their portfolio of projects, for example in relation to time and budget, would inform them about the economy of their procurements. The boards of AgriFutures Australia, the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs and Wine Australia received this reporting but the board of the Grains RDC did not. Reporting on project impact would provide information on effectiveness. All boards received some reporting on effectiveness, which was typically based on impact assessments and cost-benefit analysis.

2.16 Reporting to the boards about compliance with procurement policies provides further information about economy and ethics. This particularly applies where procurement was delegated to management. The Cotton and Fisheries RDCs and Wine Australia had a low delegation limit and their boards approved a high number of projects.

2.17 AgriFutures Australia and the Grains RDC had high delegation limits and their boards approved four and zero projects respectively. The Audit Committee of AgriFutures Australia received and considered an internal audit report on RD&E procurement in February 2018, which found non-compliance with policies in relation to conflicts of interest and assessing value for money. During 2018, neither the board of AgriFutures Australia nor its Audit Committee used the audit to revise the policies. The board of the Grains RDC did not receive reporting about compliance with procurement policies. This board should receive regular compliance reports to assure itself that management is exercising delegations consistent with policy.

Conflicts of interest

2.18 Under section 16 of the PGPA Rule, staff at the corporations must disclose material personal interests in line with any directions given by the accountable authority. The funding agreements make the same requirement of panel members. All the corporations except for the Cotton RDC managed panels. In light of these requirements, the boards were expected to receive reporting about conflicts of interest held by staff and panel members.

2.19 Of the four corporations that managed panels, none of their boards received reporting about conflicts of interest held by panel members. The board of the Grains RDC received reporting about an internal audit on panels that included managing conflicts of interest.

2.20 The Audit Committee of the Cotton RDC received reporting on staff conflict of interest, through a fraud risk management review. In February 2018, management presented the register of staff interests to the board, along with the statutory requirement that staff must disclose material personal interests. The board noted the register.

Gifts, benefits and hospitality

2.21 None of the boards received reporting on gifts, benefits and hospitality. During interviews, the corporations advised of infrequent or nil levels of receiving these items. The exception was Wine Australia, where the CEO reported attending dinners for industry consultations and receiving bottles of wine as trade samples ‘to improve his knowledge of the sector and its products’. Wine Australia advised the ANAO that these gifts and hospitality were under the $200 reporting limit in its gifts policy and did not formally need to be recorded or otherwise reported. Reporting to the boards on gifts, benefits and hospitality is proportionate to risk. Management of gifts, benefits and hospitality is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Credit cards

2.22 None of the boards received reporting on credit card use. One means by which a board could receive reporting on them would be through conducting an internal audit. None of the entities conducted an internal audit of credit cards in 2017 or 2018. Compliance with policy in managing credit cards can be an indicator of culture, in which case its importance to senior management and the accountable authority extends beyond the materiality of the transactions.

Probity incidents

2.23 Six probity issues arose across the five corporations in 2017 and 2018. On the basis of confirmed incidents and legal requirements, reporting to the boards was appropriate. Two occurred at AgriFutures Australia, which investigated and finalised the matters with a nil finding. Four occurred at the Grains RDC. Two occurred within the board and were resolved by the board. One was a public interest disclosure made under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 and not eligible to be reported to the board.21 The final matter involved staff. It was not investigated, not confirmed, and not reported to the board.22 The probity incidents are discussed further later in this chapter (see paragraphs 2.99 to 2.102).

Did the boards appropriately manage probity risks?

2.24 Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires the accountable authority of each Commonwealth entity to establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk oversight and management.23

2.25 One way that boards can demonstrate risk oversight is to approve appropriate risk policies and to receive risk reports in line with these policies. All the boards approved a risk framework through a board charter or risk policy. Table 2.1 provides further information on how the boards oversighted risk.

Table 2.1: Board oversight of risk at the RDCs, 2017 and 2018

|

|

Framework approved |

Reporting frequency |

2017 reporting |

2018 reporting |

|

AgriFutures Australia |

2014, 2018 |

Not specified |

3/4 |

2/4 |

|

Cotton RDC |

2015, 2018 |

Not specified |

5/6 |

5/7 |

|

Fisheries RDC |

2016, 2017, 2018 |

Every meeting; not specified from August 2018 |

4/5 |

0/3 then 2/2 |

|

Grains RDC |

2015, 2017, 2018 |

2/year |

3/6 |

1/6 |

|

Wine Australia |

2014 |

1/year and as required |

0/5 |

0/5 |

Notes: The Fisheries RDC board adopted a new risk framework in August 2018 which did not have specific reporting requirements.

In the last two columns, the first figure is the number of meetings that the board received risk reporting and the second figure is the number of regular board meetings that year.

The years in the ‘framework approved’ column show if the board approved a framework in 2017 or 2018, as well as the most recent approval before then.

Source: ANAO analysis of the corporations’ risk policies and board papers.

2.26 All five corporations had risk management plans and risk registers, which demonstrated risk management practices, as required under section 16. Combined with the oversight arrangements, AgriFutures Australia and the Cotton and Fisheries RDCs provided sufficient evidence to indicate compliance with section 16.

2.27 The corporations’ risk registers would typically be expected to show inherent risks, risk treatments, and residual risks within the context of their entities’ risk appetites.24 The risk registers for AgriFutures Australia and the Cotton RDC did this. The register for the Fisheries RDC did so from May 2018. The register for the Grains RDC and Wine Australia had some of these elements, but not all, meaning these corporations did not have an accurate, overall assessment of their risks:

- the Grains RDC register from January 2017 did not cover inherent risk and had little detail about treatment. The corporation revised its register in September 2018 to cover inherent risk and treatment, but omitted risk targets; and

- the Wine Australia register did not include risk appetite, some risks increased after treatment, some risks were incomplete, and some risk ratings did not comply with the process in the risk management plan. During the audit, Wine Australia provided a new risk register that addressed these matters.

2.28 Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires an accountable authority to establish an appropriate system of risk oversight and management. Key risks for the RDCs are value for money (the specialised nature of their procurements) and conflicts of interest (links to industry). Further, section 10 of the PGPA Rule requires the accountable authority to conduct fraud risk assessments regularly. The registers of all five corporations included fraud. Only the Grains RDC explicitly covered value for money (from September 2018). The registers of AgriFutures Australia, the Cotton RDC and Wine Australia included conflicts of interest and the register for the Grains RDC did so until September 2018. The register for the Fisheries RDC did not. In 2019, the Fisheries RDC updated its register to include risks for value for money and conflicts of interest.

2.29 In June 2019, the board of the Grains RDC approved a new strategic risk register that covered fraud, value for money and conflicts of interest. The register also covered inherent risks, risk treatments, residual risks, and risk targets. A new treatment in the register is regular compliance reporting to the Audit and Risk Committee and the board.

2.30 Probity incidents represent an opportunity for the corporations to update their risk registers. As discussed below, the only corporation subject to a confirmed incident was the Grains RDC. There was no evidence that this corporation updated its register to take the incidents into account. The Cotton RDC did not have a probity incident, but its audit committee considered the risk impact of a civil case involving a funded researcher and requested management to examine whether the matter was covered under the current risk register.

Do the corporations have appropriate policies in place to promote probity and value for money in funding decisions, and manage intellectual property and credit cards?

Four corporations’ policies were largely appropriate in promoting probity in funding decisions, and managing intellectual property and credit cards, while Wine Australia’s policies were partially appropriate. Areas for improving or reviewing policies were:

- contract variations, for all five corporations;

- reflecting the legal requirements for conflict of interest for the Cotton RDC and Wine Australia;

- providing RD&E funding to industry bodies, for all five corporations;

- for giving and receiving gifts, for all five corporations;

- reviewing credit card transactions, for all five corporations; and

- promoting reasonable competition, for Wine Australia.

2.31 By approving policies, the corporations’ boards and senior management can stipulate standards required of staff in relation to conduct, ensuring value for money in funding decisions, appropriately managing intellectual property, and appropriately managing credit cards. Clear, comprehensive policies mean that staff need to apply less discretion in probity matters, which decreases the chances of them engaging in conduct that is, or is perceived to be, inappropriate.

Do the corporations’ policies promote probity in funding decisions?

2.32 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) apply to non-corporate Commonwealth entities and prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities. The RDCs are corporate Commonwealth entities, and do not need to comply with the Rules. The exception is the Grains RDC, which has been prescribed under the PGPA Rule. The CPRs do not state that they represent better practice for other Commonwealth entities.

2.33 The corporations’ funding agreements stated that they should draw on better practice guidance in establishing a governance framework for managing and investing their funds. The Department of Finance has issued guidance outlining 11 principles to support probity in procurement.25 Five of the principles relate to legal requirements placed on the corporations through the PGPA Act, PGPA Rule and the funding agreements. These relate to ethical behaviour, use of position (which also covers accepting gifts or benefits from potential suppliers), confidential information and conflict of interest.

2.34 All the corporations had policies in place for ethical behaviour, use of position, and confidential information.

Conflict of interest

2.35 The corporations are subject to multiple legal requirements in relation to conflict of interest under section 29 of the PGPA Act, sections 14 to 16 of the PGPA Rule, and clause 4 of their funding agreements. The legal requirements include detail on how the board must manage directors’ declared interests. The requirements are listed in Appendix 2.

2.36 The corporations were effective or largely effective in incorporating these legal requirements into their policies (see Table 2.2). At Wine Australia, the CEO rather than the board approved the conflict of interest policies. This does not comply with section 16 of the PGPA Rule that requires staff to disclose their material personal interests in line with any instructions given by the accountable authority. Better practice would be for the directors to take responsibility for declaring and managing their interests and approve the policies that apply to them, rather than the CEO doing this.

Table 2.2: Inclusion of conflict of interest requirements in RDCs’ policies

|

Corporation |

Completeness |

Commentary |

Reference |

|

AgriFutures Australia |

|

Meets all requirements |

NA |

|

Cotton RDC |

|

Did not explain the process in the PGPA legislation under which a board member must leave the meeting and not vote Legislation requires the accountable authority to decide if a director stays in a meeting, but the policy states this is a decision for the Chair |

Sub-sections 15(2) and 15(3) of the PGPA Rule |

|

Fisheries RDC |

|

Meets all requirements |

NA |

|

Grains RDC |

|

Meets all requirements |

NA |

|

Wine Australia |

|

Legislation requires staff to comply with any policy that the board approves for staff to disclose material personal interests, but the CEO approved the policy |

Section 16 of the PGPA Rule |

Key:

![]() no requirements implemented

no requirements implemented

![]() up to one third of requirements implemented

up to one third of requirements implemented

![]() between a third and two thirds of requirements implemented

between a third and two thirds of requirements implemented

![]() between two thirds and all except one requirement implemented

between two thirds and all except one requirement implemented

![]() all requirements implemented

all requirements implemented

Note: Nine legal requirements for conflicts of interest were tested. The Cotton RDC did not manage industry panels, so it had eight applicable requirements. Wine Australia had ten because its Act modifies the definition of a material personal interest for that entity.

Source: ANAO analysis of the RDCs’ policies.

2.37 As noted in paragraphs 1.19 and 2.28, the corporations have links with industry, creating the potential for conflicts of interest. This risk is recognised in their establishing legislation and all the corporations had conflict of interest policies that sought to avoid and manage this risk. The legislation provides some detailed processes and two of the corporations can improve their policies by incorporating all these requirements.

Recommendation no.2

2.38 The Cotton RDC and Wine Australia revise their conflict of interest policies to fully reflect legal requirements.

Cotton RDC response: Agreed.

2.39 CRDC will update the conflicts of interest policies to fully reflect the legal requirements.

Wine Australia response: Agreed.

2.40 The Wine Australia Board has revised and approved its policies with respect to conflicts of interest. These policies fully reflect legal requirements.

2.41 Testing of procurements, discussed further in Chapter 3, identified opportunities for the RDCs to extend or clarify policies around conflicts of interest. In one case, the board of the Fisheries RDC approved a project out of session at the request of management. Its policies and procedures for managing conflicts do not refer to out of session decisions26 and those for out of session decisions do not refer to managing conflicts of interests. The corporation could not demonstrate that it had considered conflicts of interest before making its decision. The Fisheries RDC is revising its board governance policy to address this issue.

2.42 The corporations’ policies did not fully cover managing declared interests, particularly those of staff. Section 29 of the PGPA Act requires directors and staff to declare material personal interests. Section 16 of the PGPA Rule requires staff to disclose material personal interests in accordance with any instructions made by the accountable authority. The purpose of these declarations is that the RDCs and their panels can then manage the interests.27 In respect of policies to manage conflicts:

- A Director at Wine Australia had an interest in a research organisation that received funding at a meeting. The minutes did not record it or whether the board managed it. Wine Australia’s policies did not provide guidance on managing conflicts.28

- The policies for AgriFutures Australia and the Grains RDC described systems for managing disclosed interests of staff, including at meetings. The policies for the other corporations did not. The testing in Chapter 3 indicated that no corporation could demonstrate using the disclosures to manage interests, partly because three of the corporations did not have this in their policies. It is suggested that these corporations amend their policies so they can positively demonstrate they are managing declared conflicts of interest.

2.43 The Department of Finance guidance to support probity in procurement (discussed in paragraph 2.33) lists six further principles that are not legal requirements. They are:

- officials avoiding claims of bias;

- entities not benefitting from dishonest, unethical or unsafe supplier practices;

- treating all tenderers equitably;

- applying probity and conflict of interest requirements proportionately;

- not excluding suppliers from consideration for inconsequential probity reasons; and

- appointing external probity specialists only where justified.29

2.44 The policies of the Grains RDC incorporated all these principles. The four other entities incorporated four of the principles in their policies. The principles that were typically omitted were in relation to not excluding suppliers from consideration for inconsequential probity reasons and appointing external probity specialists only where justified.30

Gifts, benefits and hospitality

2.45 A policy for giving and receiving gifts, benefits and hospitality is an important element of a robust control environment and supports ethical conduct. Section 27 of the PGPA Act states that an official must not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit to themselves or another person. The giving or receiving of gifts, benefits and hospitality can create the perception that the RDCs are subject to inappropriate external influence. In his speech to the Australian Public Service in April 2019, the Prime Minister stated that entity decisions must be made in the best interests of the general public, not organised interests.31

Receiving gifts, benefits and hospitality

2.46 Officials at the five RDCs, which includes the board and staff, have legal obligations around the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality. Accepting a gift, benefit or hospitality connected to employment at one of the corporations could raise the question of compliance with section 27 and can create a real or perceived conflict of interest.

2.47 All the corporations had policies for the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality. The policies were generally available on the corporations’ intranet. Except for the Cotton RDC, they also defined gifts, benefits and hospitality and required approval to retain gifts of a certain value (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Details of the RDCs’ policies for receiving gifts, benefits and hospitality

|

Corporation |

Policy date |

Published on intranet |

Gifts defined |

Specific reporting timeframe |

Threshold for written reporting |

Approval to keep gifts |

Central gifts register |

|

AgriFutures Australia |

Dec 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

– |

$0 |

$50 value and above |

Yes |

|

Cotton RDC |

Aug 2017 |

Yes |

No |

– |

No |

No |

No |

|

Fisheries RDC |

Jun 2017 |

Yes |

Yes |

– |

$0 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Grains RDC |

Dec 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

14 days |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Wine Australia |

Undated |

No |

Yes |

5 working days |

$200 |

Yes |

Yes |

Note: The policy for the Fisheries RDC required a recipient to report the gift, benefit or hospitality immediately.

Source: The corporations’ gifts, benefits and hospitality policies.

2.48 The most commonly omitted provisions across the entities were for the reporting timeframe and whether there was a value threshold above which the staff member had to provide written advice to the RDC about the gift, benefit or hospitality received. The policy for AgriFutures Australia was due to be reviewed in December 2018 and was reviewed in May 2019. The boards of the Cotton and Grains RDCs approved new gifts policies in June 2019 that set a $50 reporting threshold and addressed all the other items in the table, except reporting period for the Cotton RDC. The Fisheries RDC updated its employees policy in September 2019 to include detailed processes for the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality.32

2.49 Testing of compliance with the corporations’ policies, discussed at paragraph 3.23, showed that AgriFutures Australia had significant detail in its central gifts register.33 This demonstrated the scale of the risk of improper external influence through the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality, and that AgriFutures Australia was managing the risk. This approach applies to Wine Australia to a lesser extent because the $200 reporting limit provides less visibility than the $0 limit that AgriFutures Australia applied.34 Given the nature of its business, Wine Australia’s $200 limit as a sole reporting criterion is too high. It is suggested that the RDCs set reporting criteria that manage the risk of inappropriate external influence and provide visibility around the volume of gifts, benefits and hospitality received and offered.35

2.50 Official hospitality may include the provision of meals and beverages to directors and staff as part of conducting official business. AgriFutures Australia had a policy to manage this but the other four RDCs did not. Due to the risks to the corporations’ reputation and to avoid the perception of undue influence on conduct or decisions, it is also suggested that these four RDCs implement guidance around receiving hospitality when undertaking official business.

Giving gifts, benefits and hospitality

2.51 Three of the corporations had policies for giving gifts, benefits and hospitality36:

- AgriFutures Australia’s policy had an approval process, required a work purpose, and had clear guidance and examples;

- the Fisheries RDC policy had an approval process; and

- Wine Australia’s policy had an approval process and had clear guidance and examples.

2.52 In June 2019, the board of the Grains RDC approved a policy and guidelines for the giving of gifts and hospitality. The policy has an approval process, requires the giving to be for a work purpose, and has clear guidance and examples.

2.53 The corporations may wish to compare policies to take advantage of each other’s better practice. These include:

- AgriFutures has specific guidance about what is reasonable hospitality at functions (for example quantities of alcohol and around tips), and required the Chair to approve gifts received by the Executive Director to exclude self-approval;

- the Grains RDC policy gave specific examples of what is or is not a gift or benefit and required staff to declare the cumulative value of gifts received from the donor; and

- Wine Australia’s policy had examples of inappropriate conduct and suggestions about how an official might make a judgement, for example what is the intent of the gift, likely perceptions, and what if the situation was reversed.

2.54 More broadly, in October 2019 the Australian Public Service Commission released whole of government guidance on gifts and benefits that requires agency heads to publicly declare all gifts and benefits received of over $100 in value every quarter. The guidance states that it represents better practice for corporate Commonwealth entities such as the RDCs and that one of its principles is to promote consistency across Commonwealth entities.37

Do the corporations’ policies promote value for money?

2.55 As discussed in paragraph 2.2, section 15 of the PGPA Act requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to promote the proper use and management of its public resources, where ‘proper’ is economical, effective, efficient and ethical. Section 26 requires the accountable authority and staff to act for a proper purpose. As corporate Commonwealth entities, the RDCs are not bound by the CPRs or the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) and can establish their own processes provided they comply with sections 15 and 26 of the PGPA Act. One exception is the Grains RDC, which has been prescribed by section 30 of the PGPA Rule and must use the CPRs for procurements at $400,000 and over.38 Other exceptions are that the corporations must comply with the CGRGs when they make grants on behalf of the Commonwealth39 or agree to do so in a funding contract. One means by which the corporations might support value for money is to have policies that promote competition. Such an approach would need to be flexible and take into account that the market for research and development is specialised and in some cases there may be only one suitable supplier.40 The corporations’ procurement policies and procedures were examined for whether:

- they had thresholds for running an open tender on a procurement;

- the thresholds were reasonable41;

- any exemptions to an open tender were reasonable and based on evidence or consultations;

- exemptions to an open tender had the appropriate level of approval;

- the value of the procurement needed to be estimated; and

- application selection criteria covered contractor experience, cost and adoption.

2.56 AgriFutures Australia and the Fisheries RDC had all these items in their procurement policies and procedures. The Cotton RDC’s policy required the board to approve the procurement method for all RD&E procurements.42 Testing in Chapter 3 indicated that the Cotton RDC used open tender for the majority of its large procurements. The Grains RDC, which is also covered by the CPRs, had all items except for the minimum selection criteria. Wine Australia only required its staff to estimate the total maximum value of the procurement.

2.57 For procurements of $300,000 and above, the procurement policy of the Fisheries RDC required one of three methods: open tender; government panel (selecting three panel members); or an open call for research proposals. The policy included an exemption to this if the board approved a project. Testing of its 20 major projects (reported in Chapter 3) revealed no documentary evidence that the corporation used any of these methods for the projects; the Fisheries RDC advised that one of them went to open tender. The board approved all of the 15 general RD&E procurements tested without management formally appraising them of the tender method. All 15 were above the relevant threshold. The corporation better managed the five procurements under the National Carp Control Plan by documenting management’s recommendation to the board to delegate approval to the Executive Director and use limited tender due to time constraints, as well as the board’s approval of this. It is suggested that the Fisheries RDC amends its procurement policy so the board only uses the general exemption if management formally briefs it on the tender method.

Financial variations

2.58 The requirements for economical, effective, efficient and ethical procurements in the PGPA Act also applied when a corporation considered whether to increase the value of a contract after it had commenced. The means by which the RDCs might support value for money in financial variations were to:

- have an appropriate level of negotiation and approval;

- consider a budget for the additional work;

- assess the reasonableness of the budget;

- consider the cumulative effect of prior variations; and

- consider contractor performance to date.

2.59 None of the corporations’ policies covered all the criteria for assessing whether to approve a variation. The policies of all the corporations had guidance on who would approve a variation. Further, the Cotton RDC had a Researchers’ Handbook that explained how a researcher should apply for a variation, for example submitting a revised budget. It is suggested that the corporations develop comprehensive policies on variations to better demonstrate they are achieving value for money when agreeing to a variation.

Economic impact assessments

2.60 The Council of Rural Research and Development Corporations has published guidance on how to calculate the economic impact of research and development projects, such as return on investment and cost/benefit ratio. The corporations conduct these assessments for the projects that they select.

2.61 As one element of the decision-making process, the corporations could analyse this data to determine whether certain project characteristics are correlated with economic, environmental and social outcomes. After comparing projects with a high return against those with a low return, the RDCs can use the results to better target future investments. The corporations’ procurement policies showed no evidence that this had occurred. In July 2019, the Fisheries RDC received a proposal from a consultant for a preliminary study into non-market impact valuations.

Commonwealth Procurement Rules

2.62 The Grains RDC is subject to specific legal requirements that support value for money. It is prescribed under section 30 of the PGPA Rule and must comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules for procurements at or above $400,000. The Grains RDC’s policies were tested against six requirements in the Rules. Its policies reflected the legal requirements that:

- it must use AusTender for open tenders;

- it must estimate the value of the procurement before making a decision; and

- it can obtain an exemption from Division 2 of the Rules (tender types and tender processes) when it is procuring research and development.

2.63 The Grains RDC’s policies did not reflect the legal requirements that:

- the official responsible for the procurement be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that they achieved a value for money outcome;

- the entity must consider the six assessment items in the Rules; and

- it must report on AusTender all procurements at or above $400,000 within 42 days of entering into the contract.

Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines

2.64 When conducting its tourism grants program, Wine Australia was subject to the CGRGs because it agreed to do so when it received the funding from the Commonwealth. Wine Australia’s policies were tested against six requirements in the CGRGs. Its policies reflected the legal requirements that it:

- develop grant opportunity guidelines;

- have regard to the seven key principles for grants administration43;

- publish the grants on specified websites within a certain time period after the individual agreements take effect; and

- retain individual grants information on its website for two years, or publish the information on GrantConnect.

2.65 Wine Australia’s policies did not reflect the legal requirements that:

- the grant approval includes an assessment against the grant opportunity guidelines and how the grant achieves value for money; and

- the grant opportunity guidelines will be publicly available.

Do the corporations have appropriate policies for intellectual property and project technology?

2.66 Under section 11 of the PIRD Act and section 7 of the Wine Australia Act 2013, the corporations’ functions include disseminating and commercialising, and facilitating the dissemination and commercialisation of, the research and development for their relevant industries. Legally registering project outputs as intellectual property supports their commercialisation, but registering is not required to disseminate those outputs.

2.67 All the corporations had established policies and procedures, including terms in standard contracts, for managing intellectual property in RD&E procurements. During fieldwork, the audit discussed with the RDCs key issues regarding project technology and intellectual property and how the corporations could manage them in RD&E contracts. They comprised:

- access to the researcher’s intellectual property;

- access to third party intellectual property;

- decision-making around whether to commercialise or disseminate;

- ownership of project outputs; and

- requiring researchers to protect project outputs.

2.68 The corporations had policies that covered these items except for AgriFutures Australia. Its standard contract did not mention third party intellectual property and did not allocate responsibility for access to it. The other corporations’ contracts placed responsibility for this on the researcher.

2.69 The corporations’ policies, procedures and standard contracts favoured the free dissemination of project outputs over commercialisation. They did this by either expressly stating it in policy, stating that commercialisation decisions would be made for the benefit of industry, or having dissemination as the default approach in their standard contracts.

Do the corporations have appropriate policies for credit cards?

2.70 All five corporations issued credit cards to staff. Credit cards provide a flexible and convenient way for the corporations to pay for goods and services, albeit at some risk of inappropriate use. Appropriate policies around the issue of cards, their return, their use, and review of transactions help establish effective controls for the management of credit cards.

2.71 Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires Commonwealth entities to establish and maintain an appropriate system of internal control. There are generally recognised better practice processes in relation to credit cards. The corporations’ credit card policies were reviewed to determine whether they covered these practices:

- for the issue of cards: there is a business need to issue the card; approved by a certain person; there are obligations for the cardholder; the cardholder agrees to the obligations; and the cards have appropriate limits;

- for the return of cards: returned when no longer needed (for example at termination of employment);

- cardholder’s responsibilities in the use of cards: they retain appropriate documentation (invoices or receipts); and they acquit the transactions; and

- reviewer’s responsibilities regarding transactions: they are independent; acquittal is timely; the reviewer confirms that the purchase was for a work purpose; that the amount is reasonable; and the credit card statement matches the invoice or receipt.

2.72 The corporations’ policies had incorporated almost all the better practice processes for the issue of cards, return of cards, and use of cards (see Table 2.4).

Table 2.4: Inclusion of better practice elements in RDCs’ credit card policies

|

Corporation |

Issue of cards |

Return of cards |

Use of cards |

Review of transactions |

|

AgriFutures Australia |

5/5 |

1/1 |

2/2 |

3/5 |

|

Cotton RDC |

5/5 |

1/1 |

2/2 |

2/5 |

|

Fisheries RDC |

4/5 |

1/1 |

2/2 |

1/5 |

|

Grains RDC |

5/5 |

1/1 |

2/2 |

1/5 |

|

Wine Australia |

3/5 |

1/1 |

2/2 |

1/5 |

Note: The first number in each cell is the number of better practice elements that the corporation included in its policy and the second number is the number of elements tested (as indicated in paragraph 2.71).

Source: Analysis of the corporations’ credit card policies.

2.73 The corporations’ policies for review of transactions is an area for improvement. None of the policies required the reviewer to assess that the amount was reasonable or match the supporting documents against the credit card statement. Only the policy for AgriFutures Australia required the reviewer to assess that the purchase was for a work purpose.

2.74 Wine Australia included the least number of better practices in its policies. During the audit, Wine Australia prepared a draft policy that meets all these better practices.

2.75 Acquittal of the final statement by employees reduces the chance of them making unauthorised purchases when they have changed roles or ceased employment. Testing of credit card transactions, discussed at paragraph 3.81, showed that the Grains RDC and Wine Australia had an employee leave the corporation without acquitting their final statement, which was not required under their policy at the time.

2.76 The Grains RDC and Wine Australia updated their credit card policies in December 2018 and July 2019 respectively to include a requirement that cardholders must acquit their final statement prior to their exit interview. The Fisheries RDC had this requirement in its policies; the remaining two corporations may wish to adopt it.

Do the corporations have internal controls that promote compliance with probity requirements and effectively address non-compliance?

The five RDCs have developed systems of internal control that are largely appropriate for their probity requirements. Key measures include: fraud control plans; internal audit programs to confirm compliance with probity policies; and training on probity issues. Areas for improvement included:

- establishing a mechanism for the public to confidentially report fraud and probity allegations, for the Cotton and Grains RDCs and Wine Australia;

- Wine Australia to consider including fraud as a topic in its internal audit program, and fully comply with the 10 legislated requirements for fraud control; and

- increased training on probity policies, for AgriFutures Australia, the Fisheries and Grains RDCs, and Wine Australia.

Six allegations of non-compliance related to probity were reported to the RDCs in the two-year period to 31 December 2018, with five of the six addressed and managed effectively. The Grains RDC did not document investigating or finalising one allegation beyond initial scoping.

Have the entities established an appropriate system of internal control?

2.77 Information on the effectiveness of internal controls gives the board assurance around compliance with probity policies and the extent to which staff will uphold standards of conduct. Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires the corporations’ boards to establish an appropriate system of internal control. Section 17 of the PGPA Rule requires the boards to establish an audit committee and systems of internal control. This would include coverage of oversight of the management of identified probity risks including fraud.