Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Primary Healthcare Grants under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health's design, implementation and administration of primary healthcare under the Indigenous Australians' Health Program (IAHP).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Indigenous Australians’ Health Program (IAHP) was established in 2014 through the consolidation of four existing Indigenous health funding streams administered by the Department of Health (the department). The IAHP aims to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with access to effective high quality, comprehensive, culturally appropriate, primary healthcare services in urban, regional, rural and remote locations across Australia.1 Primary healthcare services are usually the ‘entry point’ for persons into the broader health system and can be contrasted to services provided through hospitals or when people are referred to specialists.

2. The bulk of IAHP expenditure is via grants. Since 2015, IAHP primary healthcare grants totalling approximately $1.44 billion have been awarded with 85 per cent of this funding going to Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations.

3. As at March 2018, a total of 164 organisations are receiving IAHP primary healthcare grant funding. In 2016–17, IAHP-funded services provided primary healthcare services to an estimated 352,000 Indigenous Australians. This represents 54.2 per cent of the estimated total Indigenous population.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The IAHP was selected for audit because it is intended to contribute towards achieving the Indigenous health-related ‘Closing the Gap’ targets regarding life expectancy and infant mortality. The program represents the Australian Government’s largest direct expenditure on Indigenous primary healthcare.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s design, implementation and administration of primary healthcare grants under the IAHP.

6. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did the department design the IAHP primary healthcare components consistent with the Government’s objectives in establishing the IAHP?

- Has implementation of the IAHP primary healthcare components been supported through effective coordination with key Government and non-Government stakeholders?

- Has the department’s approach to assessing primary healthcare funding applications and negotiating funding agreements been consistent with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines?

- Has the department implemented a performance framework that supports effective management of individual primary healthcare grants and enables ongoing assessment of program performance and progress towards outcomes?

Conclusion

7. The department’s design and implementation of the primary healthcare component of the IAHP was partially effective as it has not yet achieved all of the Australian Government’s objectives in establishing the program. The department has not implemented the planned funding allocation model and there are shortcomings in performance monitoring and reporting arrangements. However, the department has consolidated the program, supported it through coordination and information-sharing activities and continued grant funding.

8. The Government’s original objectives in establishing the IAHP are due to be fully achieved in 2019–20, four years later than originally planned. The majority of IAHP primary healthcare grant funding to date has been allocated in essentially the same manner as previous arrangements rather than the originally intended needs based model. Program implementation has been supported through appropriately aligning funding streams to intended outcomes and coordination and information-sharing with relevant stakeholders.

9. Most aspects of the department’s assessment of IAHP primary healthcare funding applications and negotiation of funding agreements were consistent with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs). The exception to this was the poor assessment of value for money regarding the majority of grant funds. The grant funding agreements were fit for purpose, but the department has not established service-related performance benchmarks for funded organisations that were provided for in most of the agreements.

10. The department has not developed a performance framework for the Indigenous Australians’ Health Program. Extensive public reporting on Indigenous health provides a high level of transparency on the extent to which the Australian Government’s objectives in Indigenous health are being achieved. However, this reporting includes organisations not funded under the IAHP and, as such, it is not specific enough to measure the extent to which IAHP funded services are contributing to achieving program outcomes.

11. In managing IAHP primary healthcare grants, the department has not used the available provisions in the funding agreements to set quantitative benchmarks for grant recipients. This limits its ability to effectively use available performance data for monitoring and continuous quality improvement. Systems are in place to collect performance data, but systems for collecting quantitative performance data have not been effective. Issues with performance data collection limit its usefulness for longitudinal analysis.

Supporting findings

Program design and implementation

12. The design of the IAHP was consistent with the Government’s objectives of achieving budget savings and reducing administrative complexity through consolidation of existing grant programs. The objective of allocating primary healthcare grant funding on a more transparent needs basis will not be achieved until 2019–20, four years behind the timetable agreed by Government in establishing the IAHP.

13. Three outcomes were established for the program and set out in published IAHP grant guidelines. One of the outcomes does not clearly identify the desired end result. IAHP funding, including the primary healthcare component, are appropriately aligned to the outcomes.

14. The department uses a wide variety of forums and networks to share information and seek feedback about its current and planned Indigenous health activities, including the IAHP. Some coordination and joint planning activities relating to primary healthcare have also been undertaken through the Aboriginal Health Partnership Forums.

Awarding Grants

15. Ninety eight per cent of IAHP primary healthcare grant funding has been provided through non-competitive processes. The department obtained Ministerial agreement for these processes.

16. Most aspects of the assessment of funding proposals were undertaken consistently with the CGRGs and IAHP guidelines. The exception was assessment of value for money. Assessment records for some funding rounds, including the $1.23 billion ‘bulk’ round undertaken in 2015, lacked evidence of substantive analysis of value of money considerations. The department was also unable to provide evidence it had undertaken a value for money assessment regarding the $114 million grant to the Northern Territory Government. In virtually all cases, risk assessments formed part of the assessment process.

17. Departmental delegates were provided with sufficient advice to enable them to discharge their obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2014 in approving IAHP grant proposals. The timeliness of the advice varied, but was provided relatively quickly for the larger 2015 funding rounds.

18. Funding agreements are fit for purpose, using a grant head agreement and an IAHP-specific schedule. The specific services to be provided by each funded organisation are set out in separate Action Plans, which are appropriately referenced in the agreement schedule. The agreements with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations allow for the setting of individual performance targets, but no targets have been set. All agreements also clearly set out reporting requirements.

Monitoring and Reporting

19. The department has not established a performance framework for the primary healthcare component of the IAHP.

20. Systems are in place to collect performance data, but systems to collect quantitative performance data have not been effective. Several changes to data collection processes have resulted in an increased reporting burden on IAHP grant recipients and two six-monthly data collections being discarded or uncollected. These breaks in the data series limit its usefulness for longitudinal analysis of performance trends. The department has commenced projects to improve the quality of data, but has limited assurance over the quality of data collected before 2017 as it has not been validated.

21. The department relies on public reporting of a range of Indigenous health indicators to monitor achievement of program outcomes. The reporting includes data about services not funded under the IAHP. As such, it is not specific enough to measure the extent to which IAHP funded services are contributing to achieving program outcomes. The department was also unable to demonstrate how it used the data to inform relevant policy advice and program administration.

22. The department is not effectively using available performance data to monitor IAHP grant recipient performance and has not set quantitative national key performance indicator (nKPI) based benchmarks for grant recipients. The department’s ability to set performance expectations and assess actual performance is limited by the currency of data and variability in the content of Action Plans.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.21

The Department of Health improve the quality of IAHP primary healthcare value for money assessments, including ensuring their consistency with the new funding allocation model.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 4.10

The Department of Health assess the risks involved in IAHP-funded healthcare services using various clinical information software systems to support the direct online service reporting and national key performance indicator reporting process, and appropriately mitigate any significant identified risks.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 4.30

The Department of Health ensure that new IAHP funding agreements for primary healthcare services include measurable performance targets that are aligned with program outcomes and that it monitors grant recipient performance against these targets.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

23. The Department of Health (‘the Department’) notes the findings of the report and agrees with the recommendations.

It is pleasing that the report finds: the program has been consolidated and supported through coordination and information sharing activities; programme implementation has appropriately aligned funding streams to intended outcomes; and the objective of reducing administrative complexity has been achieved.

Work is already underway within the Department which aligns with the report’s recommendations, and the report provides a platform to continue these efforts. In particular, the Department has introduced more robust assessment processes for primary health care grants under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme and has also commenced development of enhanced performance measurements of program outcomes, supported by an outcomes-focussed policy framework. The Department’s responses to the individual recommendations provide further detail.

The report identifies that the introduction of a new funding allocation model for the distribution of primary health care funding as announced in the 2014–15 Budget is yet to be completed and finds that this deferral has contributed to a partially effective implementation of the Australian Government’s objectives in establishing the programme. The Government announced in the 2018–19 Budget that the model will be implemented from 1 July 2019 and the Department will continue to work closely with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to deliver this important initiative. The Department notes that this deferral occurred in the context of extensive stakeholder engagement together with significant data improvement activities designed to support a robust and well-developed funding model.

Whilst the Department is committed to continuous improvement of the administration of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme, the Department wishes to acknowledge and recognise the significant contribution our network of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services are making to improve the health of their communities under the Australian Government’s Closing the Gap agenda.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Commonwealth entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Program design

1. Background

Indigenous health and government funding

1.1 In 2008, the Council of Australian Governments set targets aimed at reducing or eliminating differences in specific outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. These Closing the Gap targets covered three broad areas, of which health was one. In 2013, the Australian Government released the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–23, which set out a 10 year plan for the direction of Australian Government Indigenous health policy. This was followed in 2015 by an Implementation Plan for the Health Plan. The Implementation Plan outlines the actions to be taken by the Australian Government, the Aboriginal community controlled health sector, and other key stakeholders to give effect to the Health Plan. Progress under the Implementation Plan is measured against 20 goals and 106 deliverables that were developed to complement the existing Closing the Gap targets.

1.2 While the 2018 Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap report and the 2017 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework report show gains have been made in some areas, Indigenous Australians continue to experience significantly poorer health outcomes than the general population.2 Life expectancy is about 10 years lower. Rates of chronic disease are higher, with some tending to occur at a younger age in Indigenous Australians compared to the general population. The overall burden of disease3 for Indigenous Australians is also 2.3 times higher. Some factors potentially impacting on health, such as smoking and obesity, are higher: the overall smoking rate is 2.7 times higher and Indigenous Australians are 1.6 times as likely to be obese as the general population. Some health interventions can have a long lead time before measurable impacts are seen across the target population—for example, up to three decades in the case of many smoking-related diseases.

1.3 The Australian and state and territory governments all fund Indigenous health. Estimated total direct funding on Indigenous health4 has increased since the setting of the Closing the Gap targets: from $4.76 billion in 2008–09 to $6.30 billion in 2015–16.5 Of this, expenditure specifically targeted at Indigenous Australians was $1.44 billion in 2015–16. The remainder is expenditure on ‘mainstream’ services used by Indigenous Australians, notably hospitals, and the cost of various Australian Government subsidies, including the Medicare Benefits Scheme and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Indigenous-related expenditure on public and community health services6 in 2015–16 is estimated at $1.73 billion. The Australian Government contributes 59 per cent of the total 2015–16 government expenditure on the Indigenous public and community health services category.

1.4 Measured on a per-person basis, total direct health funding on Indigenous Australians in 2015–16 by all Governments in Australia is 1.83 times greater than the direct health funding on non-Indigenous Australians. Funding on the public and community health services category of Indigenous health is 3.59 times higher.

The Indigenous Australians’ Health Program

1.5 The Department of Health (the department) has had primary responsibility for Commonwealth Indigenous health policy and funding since 1995. Since that time, the department’s role has been to improve both Indigenous Australians’ access to mainstream primary healthcare and increase the capacity of the Indigenous-specific sector to provide comprehensive primary healthcare.7

1.6 In the May 2014 Budget, the Australian Government announced the establishment of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP). It was formed by consolidating four existing funding streams administered by the department, which between them included around 30 discrete funding components.8 The consolidation was intended to reduce administrative complexity and enable an improved focus on basic health needs (including clinical primary healthcare) at a local level to improve health outcomes. The stated high-level objective for the IAHP is:

to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with access to effective high quality, comprehensive, culturally appropriate, primary health care services in urban, regional, rural and remote locations across Australia.

1.7 A new primary healthcare grant funding allocation model was also to be developed for implementation from 2015–16. As discussed in Chapter 2, development and implementation of the new allocation model has been delayed.

1.8 With the exception of ‘social and emotional wellbeing’ activities being transferred to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet9, the range of activities funded by the department under IAHP are broadly similar to those under the pre-IAHP arrangements and funding levels have increased. In 2013–14, funding under predecessor grant programs was $682.3 million (excluding social and emotional wellbeing activities). The budget allocation for IAHP funding in 2017–18 is $856.1 million.

1.9 The bulk of IAHP expenditure is via grants. As at March 2018, $743.5 million of 2017–18 grant funds had been expended or committed.10 The largest component is grants to provide primary healthcare services to Indigenous Australians, which account for $461.5 million (62 per cent) of total IAHP 2017–18 expended and committed grant funding.11 Other significant grant funding areas under the IAHP relate to activities intended to increase Indigenous Australians’ access to mainstream services12 ($108 million, or 15 per cent) and funding for various maternal/early childhood health and anti-smoking activities (about five per cent each).

1.10 As at March 2018, 164 organisations are receiving IAHP primary healthcare grant funding. Around 140 of these organisations are Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), which collectively account for 85 per cent of total IAHP core primary healthcare grant funding in 2017–18. The remaining primary healthcare grant recipients include the Northern Territory Government, various public sector regional health bodies across several states, and a small number of private sector providers and non-government organisations.

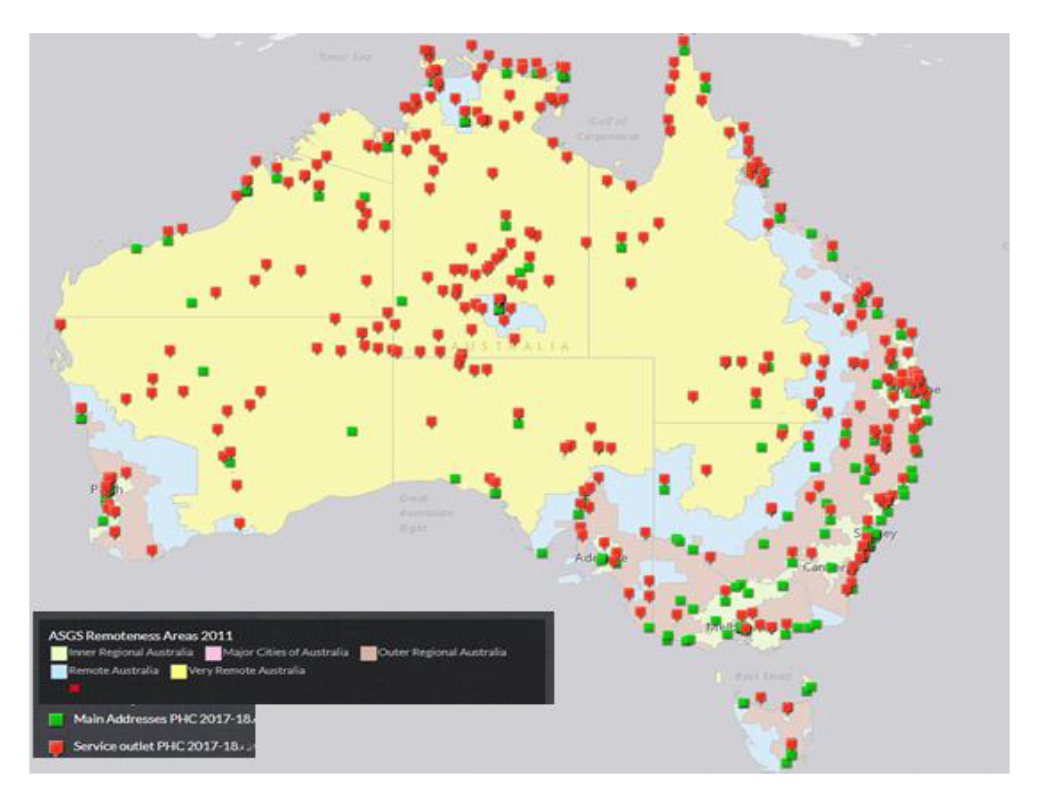

1.11 The geographical distribution of the healthcare facilities receiving IAHP primary healthcare funding is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Distribution of IAHP primary healthcare funded facilities

Source: Department of Health.

1.12 The 2017–18 primary healthcare grant funding amounts according to jurisdiction and remoteness index is shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: IAHP 2017–18 primary healthcare grants as at February 2018 ($ million)

|

|

Major city |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

Total |

|

Northern Territory |

Nil |

Nil |

50.95 |

57.99 |

34.08 |

143.01 |

|

Queensland |

20.58 |

13.50 |

42.64 |

11.45 |

6.24 |

94.41 |

|

New South Wales |

17.97 |

26.67 |

25.98 |

7.87 |

1.85 |

80.33 |

|

Western Australia |

19.15 |

2.09 |

8.26 |

25.13 |

15.48 |

70.12 |

|

Victoria |

9.28 |

11.11 |

10.52 |

Nil |

Nil |

30.91 |

|

South Australia |

10.47 |

1.66 |

4.44 |

2.95 |

6.94 |

26.46 |

|

Tasmania |

Nil |

4.79 |

1.90 |

Nil |

0.83 |

7.52 |

|

ACT |

2.54 |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

2.54 |

|

Total |

79.99 |

59.82 |

144.68 |

105.39 |

65.41 |

455.3 |

Note: Figures may not add up due to rounding. Remoteness classification is based on the main address of the funded organisation.

Source: Department of Health.

1.13 In 2016–17, IAHP-funded services provided primary healthcare services to an estimated 352,000 Indigenous Australians. This represents 54.2 per cent of the estimated total Indigenous population. As noted in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017, there is evidence that facilitating access to ‘culturally appropriate’ healthcare services can increase the effectiveness of the overall healthcare system in contributing to improved health outcomes for Indigenous Australians.13

1.14 IAHP primary healthcare grants have been awarded through several distinct funding processes. These process are:

- a non-competitive ‘bulk’ round undertaken in 2015 targeted at 145 organisations, predominantly ACCHOs, which were already receiving departmental grant funding to provide Indigenous primary healthcare services. This process resulted in the award of a total of $1.23 billion in grants over three years to 30 June 201814;

- a non-competitive process undertaken in 2015 targeting the Northern Territory Government. The resultant grant was $114 million over three years to cover a range of government–run Indigenous primary healthcare centres;

- a non-competitive targeted process undertaken in 2015 that covered a diverse range of 32 organisations undertaking various Indigenous health activities that were already receiving departmental grant funding. This process resulted in the award of total funding of $51.5 million, with some organisations receiving ongoing IAHP funding and others receiving funding for a further 12 months, after which funding was to cease;

- a non-competitive round undertaken in 2015 targeting specified Primary Healthcare Networks15—this resulted in 12 month funding totalling $17 million to maintain services on a transitional basis pending testing the market through a competitive grant funding round;

- an open competitive round undertaken in 2016 for the provision of Indigenous primary healthcare services in 11 regions that were being run on an interim basis by the relevant regional Primary Healthcare Network—in most cases the successful applicant was an ACCHO, with total funding of $32 million provided over 18 months to 30 June 2018;

- a small number of ‘unsolicited’ or ‘one-off’ grants awarded in varying circumstances.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.15 The IAHP was selected for audit because it is intended to contribute towards achieving the Indigenous health-related ‘Closing the Gap’ targets regarding life expectancy and infant mortality. The program represents the Australian Government’s largest direct expenditure on Indigenous primary healthcare.

Audit objective and criteria

1.16 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s design, implementation and administration of primary healthcare grants under the IAHP.

1.17 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did the department design the IAHP primary healthcare components consistent with the Government’s objectives in establishing the IAHP?

- Has implementation of the IAHP primary healthcare components been supported through effective coordination with key Government and non-Government stakeholders?

- Has the department’s approach to assessing primary healthcare funding applications and negotiating funding agreements been consistent with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines?

- Has the department implemented a performance framework that supports effective management of individual primary healthcare grants and enables ongoing assessment of program performance and progress towards outcomes?

Audit methodology

1.18 Audit methodology included:

- visits to eight IAHP funded primary healthcare centres in Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory and meetings with relevant management and/or senior clinical staff;

- conducting an online survey of IAHP primary healthcare grant recipients (54 responses were received, an overall response rate of 31 per cent);

- testing of departmental processes for the awarding and administration of a statistically representative sample of IAHP primary healthcare grants awarded through the processes outlined in paragraph 1.1416;

- analysis of key healthcare performance indicator and online service reporting from IAHP primary healthcare grant recipients;

- review of relevant Cabinet material and departmental documents; and

- interviews with, or submissions from, peak Indigenous Health bodies and additional individual Indigenous primary healthcare providers.

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $519,000.

1.20 The team members for this audit were Angus Martyn, Chirag Pathak, Kelly Williamson, Danielle Page, Steven Favell and Deborah Jackson.

2. Program design and implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines two issues: whether the department’s design of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Program (IAHP) primary healthcare component was consistent with the Government’s objectives in establishing the IAHP; and whether the implementation of the primary healthcare components has been supported through effective coordination with key Government and non-Government stakeholders.

Conclusion

The Government’s original objectives in establishing the IAHP are due to be fully achieved in 2019–20, four years later than originally planned. The majority of IAHP primary healthcare grant funding to date has been allocated in essentially the same manner as previous arrangements, rather than the originally intended needs based model. Program implementation has been supported through appropriately aligning funding streams to intended outcomes and coordination and information-sharing with relevant stakeholders.

Was the design of the IAHP primary healthcare component consistent with the Government’s objectives in establishing the program?

The design of the IAHP was consistent with the Government’s objectives of achieving budget savings and reducing administrative complexity through consolidation of existing grant programs. The objective of allocating primary healthcare grant funding on a more transparent needs basis will not be achieved until 2019–20, four years behind the timetable agreed by Government in establishing the IAHP.

Establishing the Indigenous Australians’ Health Program

2.1 The department had provided grants to Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and other entities to provide primary healthcare services to Indigenous Australians’ under various grant programs since 1995. These programs had not been recently reviewed or evaluated, although a study had been undertaken in 2007–08 to review the evidence base regarding the impact of primary healthcare on Indigenous Health outcomes. Prior to that, the last review of the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s funding of primary healthcare services for Indigenous Australians was in 2003–04.

2.2 Following the election of a new government in September 2013, the department commenced work on policy advice to government regarding Indigenous health grant funding in January 2014. The need for the advice was driven by the Government’s requirement to achieve savings across the Health portfolio. Key elements of the advice were developed by the end of March 2014.

2.3 The Government agreed to the advice in April 2014. In addition to achieving budget savings, key components were the consolidation of existing separate Indigenous Health grant programs into one program (the IAHP) and development of a new primary healthcare grant funding allocation model for implementation from 2015–16.17 The consolidation was intended to reduce administrative complexity and improve the focus of the Indigenous Health grants on basic health needs, including clinically-based primary healthcare. The purpose of the new funding allocation model was to encourage innovation in service delivery, and better take into account health needs and population growth in allocating grant amounts.

Budget Savings

2.4 The design of the IAHP as contained in the policy advice to the Government included budget savings of $41 million over four years through funding reductions to some anti-smoking measures. Grants for core primary healthcare services were not affected by the savings. Given the focus of this audit is on primary healthcare grants, the ANAO has not reviewed the department’s implementation of these savings. Departmental records do however show a reduction in the value of anti-smoking grants from 2015–16, the first year in which new grants were awarded under the IAHP.

Consolidation of existing Indigenous Health grant programs

2.5 The advice to government did not contain details of the proposed consolidation of grant funding programs. Subsequent IAHP grant guidelines show that the program incorporated five broad funding ‘themes’ (see further detail in paragraph 2.21), compared to over 30 discrete funding components under pre-IAHP arrangements.

2.6 As part of the consolidation process, the department introduced streamlined grant recipient reporting. Of the 164 organisations receiving IAHP primary healthcare funding in 2017–18, forty-two also received direct18 IAHP funding for specific child and maternal health activities and thirty nine received IAHP for targeted activities, including anti-smoking. The organisations report against all of these activities using a common IAHP report template, rather than separately as was the case under pre-IAHP programs. Under the IAHP, the department has also reduced the frequency of reporting19 and scope of activities to be included in annual performance reporting to focus on key achievements and challenges. Thirty-eight per cent of respondents to the ANAO survey considered that annual reporting was either very easy or somewhat easy, and 27 per cent considered it somewhat difficult.20 Funding recipients and peak bodies interviewed by the ANAO had mixed views about IAHP reporting. Where they did express views about the burden of current reporting compared to previous arrangements, these were generally positive.

2.7 The department also undertook a review of existing primary healthcare grants that were considered to be of an ‘ad-hoc’ nature. The purpose was to assess whether the activities under these grants were consistent with the newly developed IAHP primary healthcare grant guidelines. This resulted in funding for three small grants (totalling $540,000 in 2014–15) being discontinued. Another 29 grants were given funding extensions of either one or two years. For some of the grants in the latter category, further reviews done in 2016 and/or 2017 have resulted in IAHP funding being ceased.

2.8 Following the consolidation, the department extended grant funding for ‘continuous quality improvement’ (CQI)21 to all organisations receiving core primary healthcare grants22, with periodic reporting on CQI activities required as part of broader grant reporting requirements.23 From 2014, the department also let contracts for the development of a National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care and associated CQI Tools and Resources. A draft framework was developed by late 2015 but is not due for release until September 2018. Stakeholder concerns about whether the draft framework was sufficiently ‘user friendly’ across the diverse target audience of primary healthcare service providers have contributed to the delays in finalising the framework beyond the original 2015 target date. In a submission to the ANAO for the audit, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and state/territory based ACCHO peak bodies expressed frustration about the lack of progress of IAHP-related CQI initiatives.

New funding allocation model

2.9 In June 2014, the department provided the Minister for Health (the Minister)24 with information about the intended IAHP detailed design phase, including a timetable. The timetable provided that the new funding allocation arrangements would commence from 1 July 2015. That advice noted that development of the funding model would be informed by the results of external reviews to be commissioned by the department. While work was underway on the detailed design, interim IAHP grant guidelines dealing with primary healthcare only were developed.25 These were approved by the Minister for Finance in January 2015, but on the condition that revised guidelines incorporating the new funding model were provided to the Minister for Finance for approval by March 2015.

2.10 The department provided successive advices regarding the design of the IAHP, particularly the primary healthcare component, to the Minister from late 2014. The advice noted that the funding allocations under the existing grant arrangements were not linked to health outcomes or population demographics and lacked transparency, although they had resulted in a ‘reasonable range of primary healthcare services being delivered across the country’. The existing grant funding allocation process was also not designed to ‘drive organisational efficiency’.

2.11 Departmental advice to the Minister in late 2014 foreshadowed the funding model would likely incorporate at least some cost benchmarking component to facilitate a better understanding of individual organisations’ funding needs. Following the completion of the external reviews, the department advised the Minister in February 2015 that the results showed a ‘great variability in service size, mix, workforce structures, service delivery costs and outcomes has led to significant variability in cost and performance’. Costs per client and per service varied even for services in the same geographic remoteness category. The advice concluded that it was ‘not possible to come up with an arithmetic model that will provide a defensible and acceptable solution’ to allocate future primary healthcare grant funding levels via a cost benchmarking approach. Instead, the department proposed that additional or new funding could be provided to organisations operating in regions with identified high Indigenous health needs and/or high Indigenous population growth. This regional funding element would form the key part of the new funding model for allocating primary healthcare grant amounts from 1 July 2015.

2.12 The department subsequently advised the Minister it could not develop new IAHP grant guidelines incorporating the regional funding element by the March 2015 deadline set by the Minister for Finance. It cited the desirability of consulting with the Indigenous sector, as well as ongoing work in response to both the whole of government Indigenous Affairs Program Framework and the 2014 Forrest Review Creating Parity. The advice also noted that the existing interim IAHP guidelines could be used for the upcoming funding round for the allocation of grants from 1 July 2015, as long as funding agreements were offered by 30 June 2015.26 This advice was accepted by the Minister. The Minister for Finance subsequently agreed to extend the operation of the January 2015 IAHP primary healthcare guidelines to 31 December 2015. As a consequence, the large 2015 bulk funding round (representing 85 per cent of IAHP core primary healthcare funding awarded to date) proceeded under the January 2015 guidelines with no significant changes to pre-IAHP funding allocation processes.

2.13 In late 2016, the department established a stakeholder advisory committee and subsequently a stakeholder working group in a renewed effort to develop an acceptable allocation model to inform future IAHP primary healthcare funding allocations. A key issue was the availability of reliable data to underpin the various aspects of a model.27 In 2016 and 2017, the Prime Minister approved successive deferrals of the development of the funding allocation model.

2.14 The department provided advice to government on a new funding allocation model in early 2018. In February 2018 the government agreed to the proposed model. In simple terms, the share of total IAHP primary healthcare funding each organisation receives under the new funding allocation model will depend on how many clients it has, the number of episodes of care28 it provides, the relative remoteness of the service, and the health needs of Indigenous Australians in the local area.29 The financial impact of the new model will be phased in over time.

2.15 No decision has been made about whether the next funding round will be restricted to organisations currently receiving IAHP primary healthcare funding.

2.16 For ACCHOs, the funding allocation model is due to determine grant allocations from 1 July 2019. A number of state and territory entities and a small number of non-ACCHO organisations receive IAHP primary healthcare funding. The Minister has agreed that the funding model will be applied to this group from 1 July 2020.

2.17 In recognition that organisations providing IAHP-funded primary healthcare also generally have access to income through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), future IAHP funding arrangements may factor in MBS income streams. The department advised the ANAO that it will commence discussions with stakeholders in June 2018 about MBS income streams and their relationship to the funding model in the context of developing a ‘sector sustainability strategy’.

2.18 Unlike some other options considered during the development of the funding model, the proposed model does not incorporate any ‘performance’ based component—that is, funding amounts are not directly linked to achieving performance measures. As at March 2018, the department is in the early stages of developing what it describes as a more ‘outcomes’ based (as compared to ‘activities’ based) Indigenous primary healthcare policy framework. The draft policy framework has provision for the development of a revised set of primary healthcare program performance indicators. The department has advised Government that the potential use of such performance indicators as the ‘quality’ based component of any revisions of the funding model after 2019 is still the subject of stakeholder discussions. The department plans to undertake an initial review of the operation of the funding model in 2020.

Did the department establish clear outcomes for the IAHP and align the primary healthcare funding stream with these?

Three outcomes were established for the program and set out in published IAHP grant guidelines. One of the outcomes does not clearly identify the desired end result. IAHP funding, including the primary healthcare component, are appropriately aligned to the outcomes.

2.19 As stated in the published IAHP program guidelines, the intended outcomes from the IAHP are improvements in:

- the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people;

- access to comprehensive primary healthcare; and

- system level support to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary healthcare sector to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of services.

2.20 ‘Outcomes’ should relate to the effects on the intended beneficiaries of the grants.30 While the first two IAHP outcomes noted above are consistent with this, the ‘system level’ support outcome is more of an output—a product delivered by the grant program. The ‘system level’ support outcome could be better stated simply as improving the ‘effectiveness and efficiency of services’. The department’s approach to assessing the extent to which these outcomes are being achieved is covered in Chapter 4.

2.21 In order to support the achievement of outcomes, the IAHP incorporates a number of broad funding ‘themes’:

- direct comprehensive primary healthcare services (budget allocation of $529.7 million in 2017–1831);

- improving access to primary healthcare, including by increasing the capacity of ‘mainstream’ services to provide culturally appropriate care and also by improving outreach, coordination and referral services to connect Indigenous Australians to the full range of services appropriate to their health needs ($152.1 million in 2017–1832);

- targeted health activities such as anti-smoking, mental health, eye and ear health, blood borne viruses and sexually transmitted infections, chronic conditions such as diabetes, renal disease, cancer, heart disease, respiratory disease and rheumatic heart disease ($135.9 million in 2017–18);

- capital works, including the upgrading and repair of IAHP funded primary healthcare facilities and residential staff accommodation ($15.0 million in 2017–18);

- governance and system effectiveness, including funding of information systems, system support, data, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement ($45.8 million in 2017–18).

Is implementation of the IAHP primary healthcare component appropriately supported through coordination and information-sharing with relevant stakeholders?

The department uses a wide variety of forums and networks to share information and seek feedback about its current and planned Indigenous health activities, including the IAHP. Some coordination and joint planning activities relating to primary healthcare have also been undertaken through the Aboriginal Health Partnership Forums.

2.22 The department’s policy and program activities relating to Indigenous Health are supported through a range of established stakeholder engagement forums. These include Commonwealth only forums, Commonwealth-state/territory forums, and those built around the ACCHO sector or involving other Indigenous health sector stakeholders (see Table 2.1).33

Table 2.1: Indigenous Health Stakeholder Engagement Forums

|

Forum |

Purpose |

Representation |

|

National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Standing Committee (NATSIHSC) |

Provide strategic advice on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health to the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, undertake commissioned project work to support national goals. |

Heads of Commonwealth, state and territory government Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services. |

|

Indigenous Health Roundtable |

Discuss strategic issues of importance to Closing the Gap in health outcomes. |

Senior officials from the Departments of Health, Prime Minister and Cabinet, Education, Human Services, Social Services and Infrastructure. |

|

Aboriginal Health Partnership Forums (separate forum for each state and territory) |

Support joint planning and targeted evidence based actions to continue to improve health and well-being outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. |

ACCHO peak body for relevant jurisdiction; Department of Health; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; relevant state or territory government entity; Primary Healthcare Networks. |

|

National Sector Support Network Forums |

Support ACCHOs to deliver high quality, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care. |

Department of Health; NACCHO; ACCHO peak body from each state and territory. |

|

Implementation Plan Advisory Group |

Provide advice to the Commonwealth regarding the Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan. |

Department of Health; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; NACCHO; Torres Strait Islander representative: National (Indigenous) Health Leadership Forum; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; NATSIHSC; Indigenous health experts. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Health documentation.

2.23 In addition to the various forums in Table 2.1, senior departmental staff based in the capital city offices visited by the ANAO during the course of this audit reported that they maintained a range of networks with stakeholders to discuss policy or administrative matters relevant to Indigenous health, including the IAHP. The nature of these networks varied between jurisdictions. Examples included: regular meetings with counterparts in the state or territory entity responsible for Indigenous health; regular meetings with senior officers from other relevant Commonwealth entities represented in the state or territory, including the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Regional Network; and meetings with the state ACCHO peak body.

2.24 Information sharing and consultation on health-related policies and programs is a key function of the Aboriginal Health Partnership Forums that operate in each jurisdiction.34 To assist in the sharing of relevant information about Commonwealth Indigenous health activities and plans, the department circulates detailed quarterly updates to Forum members. Stakeholder feedback provided to the ANAO indicated that participants considered that the Forums, consistent with their purposes set out in the tripartite agreements, are a useful avenue for information-sharing. The department also considered that the Forums played an important role in maintaining relationships with the key stakeholders.

2.25 Around the time the IAHP was established, the department instituted a renewed attempt to improve the coordination of Indigenous primary healthcare activities. This is reflected in the Australian Government’s 2015 Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan. The Implementation Plan sets out the framework for the department’s Indigenous health activities, including the IAHP. A key strategy in the Implementation Plan for improving health system effectiveness is improved regional planning and coordination of healthcare services across sectors and providers. The Implementation Plan states that the Aboriginal Health Partnership Forums are to ‘provide the vehicle for … undertaking joint planning to inform resources allocation’.35

2.26 This is also reflected in the Forum tripartite agreements that commit partners to work collaboratively through ‘joint planning’ to improve Indigenous Health outcomes. All but one of the agreements also provide for the sharing of data on health outcomes, services and investment ‘to inform planning and decision-making’.36 Some of the Forum annual work plans provide evidence of efforts to better coordinate planning and funding. In Queensland, the Commonwealth and the Queensland Health departments have committed to undertaking a joint analysis of their Indigenous health investments in order to better target future funding. In South Australia, parties are developing a plan on shared priorities under the recently established South Australian Aboriginal chronic disease consortium. In other jurisdictions, Forums have agreed to ‘map’ existing services such as Indigenous mental health and child and maternal health to identify regions where there are services gaps so as to inform future priorities. The department has also used the Forums to assist in planning some primary healthcare-related activities such as obtaining feedback on appropriate regions to fund new child and maternal health services, evaluating regional immunisation rates and planning for the transitioning of primary health facilities from government to Indigenous community control.

3. Awarding grants

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department’s approach to assessing Indigenous Australians’ Healthcare Program (IAHP) primary healthcare funding applications and negotiating funding agreements was consistent with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs).

Conclusion

Most aspects of the department’s assessment of IAHP primary healthcare funding applications and negotiation of funding agreements were consistent with the CGRGs. The exception to this was the poor assessment of value for money regarding the majority of grant funds. The grant funding agreements were fit for purpose, but the department has not established service-related performance benchmarks for funded organisations that were provided for in most of the agreements.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving assessment of value for money.

Did the department obtain agreement for non-competitive grants processes?

Ninety eight per cent of Indigenous Australians’ Healthcare Program primary healthcare grant funding has been provided through non-competitive processes. The department obtained Ministerial agreement for these processes.

3.1 The CGRGs establish the overarching Commonwealth grants policy framework and set out expectations for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities in relation to grants administration.37 Under paragraph 11.5 of CGRGs, the use of a non-competitive grants process requires the prior agreement of the relevant Minister or entity delegate. The rationale for using such a process should also be documented. Both the 2015 and the current (2016) Indigenous Australians’ Healthcare Program (IAHP) grant guidelines provide for competitive and non-competitive funding processes. The 2016 guidelines state that ‘in areas of limited market access or specialist requirements (such as comprehensive primary health care) the IAHP is expected to preference non-competitive rounds’.

3.2 As noted in paragraph 1.14, the department has used a variety of processes to award IAHP primary healthcare grants. As at March 2018, ninety-eight per cent of healthcare grant funds have been awarded through non-competitive processes, mainly targeted at organisations already receiving Commonwealth funding under the IAHP’s predecessor program. Prior Ministerial approval for the grant processes was obtained in all cases sampled by the ANAO. Relevant departmental advice to the Minister did not explicitly set out the rationale for adopting such an approach, but generally referred to the importance of ensuring continuity of primary healthcare services to Indigenous communities.

Were assessments undertaken consistent with key aspects of the CGRGs and IAHP guidelines, including regarding value for money and risk management considerations?

Most aspects of the assessment of funding proposals were undertaken consistently with the CGRGs and IAHP guidelines. The exception was assessment of value for money. Assessment records for some funding rounds, including the $1.23 billion ‘bulk’ round undertaken in 2015, lacked evidence of substantive analysis of value of money considerations. The department was also unable to provide evidence it had undertaken a value for money assessment regarding the $114 million grant to the Northern Territory Government. In virtually all cases, risk assessments formed part of the assessment process.

2015 ‘bulk’ round

3.3 In February 2015, the department received Ministerial approval for a targeted ‘approach to market’ to fund Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and a small number of public sector regional health bodies that were then receiving departmental primary healthcare funding under a pre-IAHP grant program. Delays in developing the new funding allocation model38 meant that the department did not finalise an assessment plan until late April 2015. The assessment process outlined in the plan was consistent with the 2015 IAHP guidelines. The selection criteria in the plan were also consistent with the guidelines in that they required consideration of issues such as the alignment of the applicant’s proposed primary healthcare activities against the objectives of the program, their degree of community engagement, the organisation’s risk profile and whether the quantum and proposed use of the requested grant funds represented value for money.

3.4 The targeted organisations were given a little over three weeks to provide the department with a funding proposal, including a budget, for assessment.39 The potential applicants were provided a copy of the IAHP guidelines and a standard funding agreement about two weeks before the close of the application period. The available funding for each organisation was not fixed, although the department’s ‘request for proposal’ letter stated that past funding levels would be considered when deciding on individual funding allocations.

3.5 Departmental assessments of funding proposals were recorded in templates previously approved under the assessment plan. Relevant to value for money, the templates required consideration of whether the proposal’s budget ‘appear[s] reasonable against the proposed activities’.40 In all 47 cases in the ANAO test sample41, the assessment concluded that the proposal represented value for money. ANAO review of departmental records shows that the assessments recorded when budgets should be revised to eliminate prohibited items such as management fees or depreciation. However, the assessments did not contain any substantive analysis or evidence on why budgets were considered reasonable and consistent with value for money beyond comments which indicated that budgets were similar to previous years funding levels and activities. The assessments did not indicate that, in assessing value for money, the requested funding had been considered in the context of factors such as the specific nature of services to be provided by the applicant, remoteness or other matters that might impact on the cost of providing services, or number of services provided each year. Consistent with the assessment plan, the assessment templates also required ‘innovation’ to be a factor in reaching a conclusion whether the proposal represented value for money. However, none of the assessment criteria in the template referred to innovation and the individual assessment records did not provide commentary or analysis on the issue.

3.6 The department also undertook a ‘Service Provider Capacity risk assessment’ as part of the relevant grant assessment process.42 The risk assessment covered a consistent suite of issues including previous service performance, governance, viability, and financial management. Proposals were then assigned an overall risk rating of either high, medium or low.43

3.7 Risk ratings assigned by the assessment officer were required to be approved by a more senior officer. For the 2015 bulk round, department records for 31 of the 47 risk ratings contained clear evidence of approval; 16 of the 47 risk ratings lacked clear evidence of approval.44 The risk assessment tool provided that risk ratings should be reviewed by the department at set intervals. ANAO analysis showed that only four of the 47 most recent reviews were done within the required interval.

3.8 ANAO testing identified two instances where the department’s risk analysis was not effective in identifying underlying risks. In one of these, the past performance of an organisation was rated in May 2015 as ‘satisfactory’ to ‘good’ against the suite of risk issues and given an overall risk rating of medium. The rating lacked clear evidence of senior officer approval. A three year $2.25 million funding agreement was signed in early July 2015, with the organisation receiving its first quarterly IAHP grant payment immediately thereafter. Within a few weeks the organisation decided to close the service against a backdrop of declining level of service delivery (with clients going to other medical centres), potential fraud occurrences, and an ‘unworkable relationship’ between existing staff, the (newly appointed) Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the Board. Funding was subsequently redirected to another ACCHO in the region. In the other case, an organisation was given a medium risk rating (financial management risks were rated as low) and three year $4.22 million funding agreement was signed in early July 2015. By the end of July 2015, half of the organisation’s board had been removed by a special meeting and the CEO stood down by the new board. Various remedial actions funded by the department over 2016 and 2017, including the appointment of another ACCHO as a health management advisor, identified significant issues with the organisation, including non-compliance with the organisation’s financial procedures, budgeting weakness and overspending.

3.9 Under the assessment plan, proposals were to be rated highly suitable, suitable or not suitable according the specific assessment criteria. The initial assessment and suitability rating was followed by a scheduled ‘moderation’ process to provide a final rating. All 47 proposals in the ANAO’s test sample received a final rating of highly suitable or suitable. In 11 of these cases the original rating was upgraded as a result of the moderation process. It was not clear from the assessment moderation records why these ratings were changed.

3.10 Only one of these ‘upgrades’ involved a change from an original ‘not suitable’ rating. This instance involved an issue with the proposal’s budget that could subsequently be addressed in funding agreement negotiations. As other proposals that had similar budget issues were originally rated as suitable, this moderation upgrade was not unreasonable.

2015 ‘Miscellaneous’ round

3.11 A diverse range of non-ACCHO organisations had been funded on an ‘ad-hoc’ basis for primary healthcare-related activities under pre-IAHP programs. In seeking Ministerial approval for the IAHP grants process for these organisations, the department advised the Minister that an internal review45 indicated that the funded activities fell into three broad categories:

- activities that did not align with the IAHP primary healthcare guidelines, for which funding should cease after 12 months;

- activities that aligned with the IAHP primary healthcare guidelines, but should only be provided interim funding pending further consideration about the most appropriate means of funding these into the future; and

- activities that aligned with the IAHP primary healthcare guidelines, and should continue to receive ongoing funding similar to under the 2015 bulk round.

3.12 In late April 2015, the Minister provided policy approval for 12 months of funding for the first two categories and two years for the last category.46 The department developed an assessment plan in May 2015 virtually identical to that for the 2015 bulk round. In terms of the processes for soliciting proposals from organisations and undertaking an assessment of them, the plan did not distinguish between the three categories. The department sought proposals from the ten organisations47 that were in the last category (that is, eligible for two year funding)—these organisations were given 11 calendar days to submit a proposal.48 Assessment criteria, risk assessment and moderation processes were the same as for the 2015 bulk round. The assessments did not contain any substantive analysis or evidence on why budgets were considered reasonable and consistent with value for money beyond comments which indicated that budgets were similar to previous years funding levels and activities.

2015 Northern Territory government grant

3.13 The Northern Territory government had been funded under pre-IAHP grant programs for the provision of primary healthcare to Indigenous Australians, mostly through clinics in remote areas. As part of seeking Ministerial approval about the funding process under the IAHP, the department advised the Minister that it would only make a formal offer of a grant following receipt of a specific grant proposal and undertaking a value for money assessment against the ‘deliverables’ in the proposal. The Minister approved this approach in mid May 2015.

3.14 No specific departmental assessment plan or selection criteria was developed for the Northern Territory grant. The department contacted the Northern Territory Department of Health on 26 June 2015 to request that it provide a proposal. Departmental records indicate that a formal offer of a $114 million funding agreement to the Northern Territory Government was made on 6 August 2015, before the proposal was received on 15 August 2015. A funding agreement was signed in October 2015. The department was unable to supply the ANAO with evidence that it had undertaken value for money or risk assessments of the proposal.

2015 Primary Healthcare Networks round

3.15 In April 2015, the Minister approved an interim funding approach for 2015–16 for 11 regions where Primary Healthcare Networks were replacing Medicare Locals that had been funded under pre-IAHP arrangements to provide Indigenous primary healthcare services. Reflecting the relatively short-term (12 months) nature of these grants, the department did not develop an assessment plan and there was no application or grant assessment process undertaken by the department. Consistent with the Minister’s approval, the department proceeded directly to negotiating funding agreements with the affected networks.

2016 competitive round

3.16 In December 2015, the Minister approved a competitive grants process in the 11 regions in which Primary Healthcare Networks were providing Indigenous primary healthcare services under interim arrangements. The department developed an assessment plan in March 2016. The application and assessment process was undertaken under the 2016 IAHP grant guidelines.

3.17 Applicants had six weeks to submit proposals. This round attracted 35 applications for 11 potential primary healthcare grants.49

3.18 In comparison to the 2015 bulk and miscellaneous rounds, additional selection criteria were used in the assessment process—for example, whether the proposal contained a transition plan to ensure continuity of services during the handover of services from the existing interim service provider. The departmental assessment documentation contained much more detailed commentary and analysis of the relevant proposal regarding why the departmental assessor considered each individual assessment criterion had been met than for the 2015 bulk and 2015 miscellaneous rounds. The assessments also contained a summary setting out the specific basis of why the proposal represented value for money, rather than a simple affirmation as was the case in the 2015 bulk and 2015 miscellaneous rounds.

3.19 Consistent with the relevant assessment plan, the competitive round used a numerical scoring system to assess overall suitability for funding. The proposals in the ANAO testing scored relatively highly, with only minor changes to individual scores through the moderation process. The proposals were assessed as suitable for funding.

Unsolicited proposals

3.20 The department’s approach to assessing ‘unsolicited’ IAHP proposals has evolved over time. Both the 2015 and 2016 IAHP primary healthcare grant guidelines specifically allow for unsolicited proposals.50 No specific assessment plans were applicable to these grants. The assessment criteria differ from those used for the 2015 bulk and 2015 miscellaneous rounds. Notably, the criteria have more explicit emphasis on comparative value for money factors—they ask ‘how is the proposed activity and budget comparable to other similar services, activities and resources?’ and ‘is the proposed budget appropriate to the scale and outcomes of the proposed activity?’ The relevant assessment records in the ANAO’s sample contain substantial analysis of the proposals against these and the other assessment criteria.51 Risk assessments were completed for both grant proposals, with appropriate approval of the risk rating recorded.

Recommendation no.1

3.21 The Department of Health improve the quality of IAHP primary healthcare value for money assessments, including ensuring their consistency with the new funding allocation model.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

3.22 The Department notes that the introduction of a new distribution model for primary health care funding from 1 July 2019 will enhance the Department’s capacity to ensure value for money. The Department will also work to improve value for money considerations in future approaches to market.

Did the department provide accurate and timely advice to the grant decision maker?

Departmental delegates were provided with sufficient advice to enable them to discharge their obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2014 (PGPA Act) in approving IAHP grant proposals. The timeliness of the advice varied, but was provided relatively quickly for the larger 2015 funding rounds.

3.23 For all of the IAHP primary healthcare grants processes, a departmental delegate was the formal PGPA Act decision-maker in relation to grants. In the case of unsolicited proposals, policy approval was sought from the Minister before grant expenditure was authorised by the delegate. For all grants in the ANAO sample, the delegate accepted the positive funding recommendation made by the assessing officers. The advice to the delegate made appropriate reference to the delegate’s obligations under the PGPA Act52 and outlined the legal authority for entering into a prospective funding agreement with recommended applicants.

3.24 Fifty-eight of the 72 grants in the ANAO sample involved a discrete proposal and assessment process before advice was provided to the decision-maker about awarding the grant.53 Fifty-two of the assessment summaries contained in the relevant approval briefs to the delegate accurately reflected the individual assessment reports, including risk ratings. The inaccuracies or omissions of the remaining six cases were relatively minor and did not fundamentally impact on the recommendation that they be funded.

3.25 In 52 of the 58 grant proposals that were assessed, the advice to the delegate noted specific issues associated with the proposals that required resolution or clarification before a formal offer of funding was to be made. Issues commonly included the need for revised budgets or Action Plans. In 12 cases, the department was unable to provide evidence of how the relevant issue(s) had been resolved. For the remaining 40 cases, in all but four instances resolution occurred after the funding agreement was signed.

3.26 The time between the receipt of applications and the provision of recommendations to the departmental delegate varied widely between funding processes. For the 2015 bulk and miscellaneous 2015 rounds, the average time was about one month. For the 2016 competitive round, three months elapsed between the close of the application period and advice being provided to the delegate. The elapsed time for the two unsolicited proposals reviewed by the ANAO was approximately six months.

Are funding agreements fit for purpose, including regarding expected performance outcomes, accountability for grant funds and reporting requirements?

Funding agreements are fit for purpose, using a grant head agreement and an IAHP-specific schedule. The specific services to be provided by each funded organisation are set out in separate Action Plans, which are appropriately referenced in the agreement schedule. The agreements with ACCHOs allow for the setting of individual performance targets, but no targets have been set. All agreements also clearly set out reporting requirements.

3.27 The CGRGs highlight the need for grant funding agreements to be ‘fit for purpose’ in order to promote good governance and accountability. The CGRGs note what is fit for purpose will depend on the circumstances, but funding agreements should provide a clear understanding of matters such as:

- required outcomes;

- accountability for grant funds; and

- performance data and other information that the recipient may be required to report on.

3.28 There were two different forms of IAHP primary healthcare funding agreements. ACCHOs operated under a longer-form agreement. Both forms of agreement consisted of a head agreement and a schedule which contained requirements more specific to IAHP activities. The key contents of both forms are similar, except where noted below.

3.29 In terms of required outcomes, the IAHP schedule in the funding agreements sets out the general expectation that the grant recipient is to provide culturally appropriate primary healthcare services, tailored to the needs of the Indigenous Australians in the area serviced by the recipient. It highlights the need to embed robust continuous quality improvement activities in the delivery of these services and within the recipients’ business practices more generally. While the schedule lists the range of services that the recipient may provide, the specific services and activities that must be provided are set out in the grant proposal, updated annually through an Action Plan. Where the grant recipient also receives IAHP funding for related services (for example, child and maternal health), one Action Plan can cover all the IAHP funded activities.

3.30 In terms of accountability, the funding agreements provide clear guidance on the handling and responsibility of grant funds, including what they can be used for. The agreements protect the Commonwealth’s financial interests by providing the Commonwealth with the ability to suspend, terminate or reduce the scope of agreement, and require repayment of funds under certain circumstances. The longer-form agreements have some additional clauses which:

- allow the department to appoint a funds administrator or health management advisor, and/or require the organisation to develop and implement a remediation plan to address Commonwealth concerns about the service; and

- place restrictions on the use of sub-contractors to undertake project activities.

3.31 The funding agreements also clearly set out performance-related reporting requirements.54 In addition to the Action Plan, funding agreements require the following key reporting by recipients:

- Online Services Report (OSR) data on an annual basis and nKPI data every six months55;

- annual performance reports; and

- annual financial statements.

3.32 The ACCHO funding agreements also allow for the setting of nKPI-related performance targets. The department has not set any targets for grant recipients.

3.33 ANAO testing showed the standard performance reporting requirements noted above were sometimes varied based on specific circumstances. For example, the organisation assessed as high risk in the 2015 bulk funding round was required report every six months rather annually. This is consistent with the approach outlined in the IAHP guidelines regarding tailoring reporting to risk.

3.34 The CGRGs also state that where the delivery of services funded under a grant is likely to occur over a number of years, it may be more appropriate to provide recipients with longer term grant agreements rather than conducting multiple grant rounds and offering grants for one to two years duration. As noted in paragraph 1.10, 85 per cent of IAHP primary healthcare funding to 2017–18 has been awarded to ACCHOs, with over 90 per cent of ACCHO funding being awarded via the 2015 bulk round. Funding agreements for these grants were for a term of three years, except where the recipient was rated as a high risk, in which case the term was one year. Only one recipient in the ANAO’s sample from that round was rated as high risk.56

4. Monitoring and reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department has implemented a performance framework that supports effective management of individual primary healthcare grants and enables ongoing assessment of program performance and progress towards outcomes.

Conclusion

The department has not developed a performance framework for the Indigenous Australians’ Health Program. Extensive public reporting on Indigenous health provides a high level of transparency on the extent to which the Australian Government’s objectives in Indigenous health are being achieved. However, this reporting includes organisations not funded under the IAHP and, as such, it is not specific enough to measure the extent to which IAHP funded services are contributing to achieving program outcomes.

In managing IAHP primary healthcare grants, the department has not used the available provisions in the funding agreements to set quantitative benchmarks for grant recipients. This limits its ability to effectively use available performance data for monitoring and continuous quality improvement. Systems are in place to collect performance data, but systems for collecting quantitative performance data have not been effective. Issues with performance data collection limit its usefulness for longitudinal analysis.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at managing risk associated with using various software systems to support reporting of performance data and setting quantitative performance targets that are measurable and linked to outcomes.

Has a performance framework been established for the primary healthcare component of the IAHP?

The department has not established a performance framework for the primary healthcare component of the IAHP.

4.1 There is extensive public reporting by the Australian Government on Indigenous health. For example, the Prime Minister’s annual Closing the Gap report and the Department of Health’s annual report and portfolio budget statements (PBS) include reporting against performance measures. More extensive public reporting on a wide range of Indigenous health outcomes, health system performance and the broader determinants of Indigenous health is contained in the biennial Aboriginal and Torres Islander Health Performance Framework report. Progress against the 20 goals of the Implementation Plan for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023 is also publically reported.57 Collectively, these provide a high level of transparency on the extent to which the Australian Government’s objectives in Indigenous health are being achieved.

4.2 However, at a program level, the department has not developed a performance framework setting out how it measures the contribution of the primary healthcare component of the IAHP (or the program as a whole) towards achieving improved Indigenous health and the other IAHP outcomes.58 The department’s development of a more ‘outcomes’ based policy framework for Indigenous primary healthcare during 2018 (noted in paragraph 2.18) represents an opportunity to design and implement such a performance framework. This should also be appropriately coordinated with work that commenced in late 2017 to design an evaluation program of the Australian Government’s investment in Indigenous primary healthcare, focussing on the IAHP.59

Are systems in place to effectively collect performance data?

Systems are in place to collect performance data, but systems to collect quantitative performance data have not been effective. Several changes to data collection processes have resulted in an increased reporting burden on IAHP grant recipients and two six-monthly data collections being discarded or uncollected. These breaks in the data series limit its usefulness for longitudinal analysis of performance trends. The department has commenced projects to improve the quality of data, but has limited assurance over the quality of data collected before 2017 as it has not been validated.

Data reporting

4.3 IAHP funded organisations are required to regularly report performance data to the department, as summarised in Table 4.1 below. This section deals with key quantitative performance reporting. IAHP funded organisations are also required to provide a range of other reporting, including annual performance reports. These are discussed later in the chapter (paragraphs 4.27–4.29).

Table 4.1: Performance data reported by IAHP grant recipients

|

Data collection |

Frequency |

Data characteristics |

|

National Key Performance Indicators (nKPI) |

Six monthly, collected since 2012 |

24 quantitative indicatorsa:

|

|

Online Service Report (OSR) |

Annual, collected since 2008 |

Qualitative and quantitative data |

Note a: Data reporting on the nKPIs has increased from 11 indicators in 2012 to 24 in 2017.

Source: ANAO summary of data reporting based on Department of Health documentation.

4.4 The nKPIs were developed under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap Agreement). Process of care indicators relate to service delivery, for example whether specified health checks are carried out on patients. Health outcome indicators relate to health status, for example birthweight. OSR data provides information on the number and type of services provided, staffing, service gaps and challenges faced by organisations.

4.5 Primary healthcare services record patient and service-related data on one of a number of commercially available clinical information systems. Data reporting has varied due to the type of clinical information system used by the healthcare service. Historically, the collection of this data for nKPI and OSR reporting purposes has involved three broad steps:

- extraction of the raw data from the IAHP-funded organisation’s clinical information system. The extraction is generally undertaken by employees of individual healthcare services using specialised software (‘data extraction tool’), a licence for which is provided by a third party software provider;