Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Preparation of the Tax Expenditures Statement

The objective of the audit was to assess the completeness and reliability of the estimates reported in Tax Expenditures Statement 2006 (TES 2006). That is, the audit examined the development and publication of the detailed statement of actual tax expenditures required by Division 2 of Part 5 of the CBH Act. The development and publication of aggregated information on projected tax expenditures included in the Budget Papers pursuant to Division 1 of Part 5 of the CBH Act was not examined.

Summary

Introduction

Tax expenditures and social welfare programs are the two oldest forms of financial assistance provided by the Commonwealth Government. Tax expenditures have no precisely agreed or fixed definition. In practice, what constitutes a tax expenditure can change over time and between jurisdictions. In Australia, the Tax Expenditures Statement 2006 (TES 2006) defines a tax expenditure as:

a tax concession that provides a benefit to a specified activity or class of taxpayer… A tax expenditure can be provided in many forms, including a tax exemption, tax deduction, tax offset, concessional tax rate or deferral of tax liability.[1]

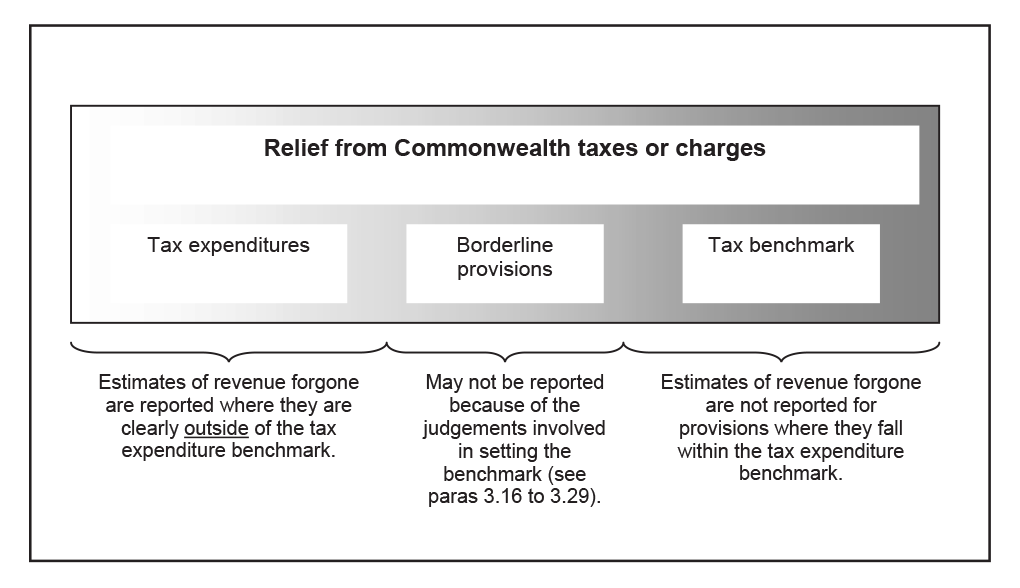

In preparing each TES, the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) measures tax expenditures by reference to a normative (or benchmark) taxation system. Under this approach, the selection of the benchmark is critical to the identification and quantification of tax expenditures. The concept is illustrated in the following diagram, which shows that concessions considered structural elements of the tax system are included within the relevant benchmark. Other concessions are to be reported as tax expenditures.

Figure 1 Application of the tax benchmark concept

Source: ANAO analysis.

In 2006–07, tax expenditures provided over $41 billion of relief to taxpayers from Commonwealth taxes and charges.2 Delivered mostly as tax exemptions, reduced rates of tax and tax rebates, total assistance through tax expenditures is similar in size to assistance delivered through the Commonwealth's largest spending (or outlay) programs. Tax expenditures incur an opportunity cost—they can represent revenue that, if collected, would have been available to fund spending programs (or outlays) to meet similar objectives or to increase the Budget surplus/reduce the Budget deficit.

The Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 (the CBH Act) introduced two separate but related requirements for annual reporting on tax expenditures. Specifically:

-

Division 1 of Part 5 (titled Annual Government reporting) of the CBH Act requires that an annual budget economic and fiscal outlook report be prepared and that it contain an overview of estimated tax expenditures for the budget year and the following three financial years. Accordingly, an appendix to Statement 5: Revenue in Budget Paper No. 1 for 2007–08 Budget Strategy and Outlook included aggregate historical tax expenditure data for 2003–04 to 2005–06 together with projected tax expenditures for 2006–07 to 2009–10 and a preliminary projection for 2010–11; and

-

Division 2 of Part 5 of the CBH Act requires the public release and tabling of a Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) report and that it contain a detailed statement of tax expenditures. The purpose of the MYEFO report is to provide updated information to allow the assessment of the Government's fiscal performance against the strategy set out in the current fiscal strategy statement.

Since the CBH Act took effect, a separate TES has been published each year except 1999–2000.3 In its March 2007 report titled Transparency and accountability of Commonwealth public funding and expenditure, the Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration noted that subsidies are generally provided by means of special appropriations and expressed the view that reporting of tax expenditures should be no less transparent than the reporting of special appropriations.4 The Committee supported the publication of the TES as an essential accountability mechanism.5

Improvement opportunities

The six audit recommendations are intended to improve the quality of information relating to tax expenditures over time so that the Government and the Parliament are better placed to be informed about the impact of relief provided from Commonwealth taxes and charges, and to be positioned to make decisions relating to trade-offs between such relief and other Budget priorities involving outlays. Specifically:

- Chapter 2 includes two recommendations aimed at establishing regular, risk-based reviews and evaluations of tax expenditure programs and encouraging the development of suitable standards for identifying and reporting tax expenditures, drawing on international developments. A further recommendation has been made in Chapter 2 aimed at encouraging greater scrutiny of tax expenditures in the annual Budget processes, by integrating their consideration with that given to outlays;

- Chapter 3 includes a recommendation that greater attention be given to identifying and collecting data on tax expenditures outside of the Treasury portfolio; and

- Chapter 4 includes two recommendations aimed at improving the reliability of new and ongoing tax expenditure estimates. For large or otherwise significant tax expenditures, one recommendation proposes that tax expenditure estimates be prepared using an approach that captures the behavioural and other effects of the concession. The other recommendation is aimed at promoting more reliable modelling irrespective of whether they are prepared under a revenue gain or revenue forgone approach.

Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to assess the completeness and reliability of the estimates reported in Tax Expenditures Statement 2006 (TES 2006). That is, the audit examined the development and publication of the detailed statement of actual tax expenditures required by Division 2 of Part 5 of the CBH Act. The development and publication of aggregated information on projected tax expenditures included in the Budget Papers pursuant to Division 1 of Part 5 of the CBH Act was not examined.

The Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration's March 2007 report referred to above noted the ANAO's forthcoming audit of the preparation of the TES. Consistent with a suggestion of the Committee, the ANAO audit has examined proposals for greater transparency in the reporting of tax expenditures made to the Committee during its inquiry. The audit also examined:

- the systems employed by Treasury—and the records supporting them—for the production and publication of TES 2006;

- the methods, models and data sources used by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to produce the reported estimates of tax expenditures; and

- the reporting of tax concessions by some other agencies responsible for administering Commonwealth taxing and charging laws so as to assess completeness of the TES. In particular, the Australian Customs Service (Customs) was included within the scope of the audit.

Audit conclusions

- The purpose of the CBH Act was to establish an integrated fiscal framework to provide for greater discipline, transparency and accountability in fiscal policy. A key element of this integrated framework was that the MYEFO report was to include detailed estimates of both tax expenditures and outlays, thereby promoting the scrutiny of both forms of expenditure. However, due to methodological challenges, Treasury has not yet found a way to integrate the reporting of outlays and tax expenditures, with the result that the detailed estimates of tax expenditures are reported in a separate TES document. Treasury has advised ANAO that it is not possible to include the full detailed tax expenditure estimates in the MYEFO release without significant changes to the focus of the MYEFO document and without delaying the release of MYEFO itself.

Treasury's view is that the best focus for controlling tax expenditures is at the policy development stage by ensuring that the Budget processes require that the cost of any new tax concession proposal (and any savings offsets) are examined in the same way as occurs for outlays. However, past practices in this area have been inconsistent. This has been compounded by shortcomings in the post-implementation measurement, monitoring and reporting (through the TES) of tax expenditures. In particular:

- the benchmarks used in preparing the TES are selected by Treasury based on judgements with the result that benchmarks may vary over time and can be arbitrary;

- whilst the CBH Act requires the TES to be based on external reporting standards,6 neither the Australian accounting standards or the economic reporting standard issued by the Australian Bureau of Statistics have been developed to account explicitly for tax expenditures. In particular, as few tax expenditures arise from direct transactions and other events of the kind commonly recorded in accounting systems, neither AAS31 nor GFS is designed to capture all the notional transactions involved in the majority of tax expenditures. The external reporting standards also do not address the selection of tax benchmarks;

- there are unreported categories of tax expenditures. Each TES from TES 1995–96 onwards has identified, on average, ten tax expenditures arising from tax concessions or relief already in place but previously unreported. In this respect, during the course of the audit, Treasury took or foreshadowed action to improve the coverage of the TES by reporting tax expenditures in relation to Customs Duty and Goods and Services Tax, as well as expanding the reporting of superannuation tax expenditures; and

- TES 2006 included quantified estimates for less than 60 per cent of those tax expenditures that were reported and, of these, two thirds were not based on reliable estimates. Modelling of the effect of tax expenditures and estimation of their cost has been made more difficult by the trend of reducing the compliance burden on taxpayers, which results in less information being collected from which estimates can be made. This situation also impedes analysis of whether individual tax expenditures are achieving their objectives.

Against this background ongoing review of tax expenditures would be beneficial given the lack of regular, risk-based reviews and evaluations of tax expenditures as to whether they are achieving their objectives and, if so, at what cost. Such a review, and ongoing scrutiny of tax expenditures, would benefit from:

- the development of standards to govern the integrated reporting of outlays and tax expenditures under the Charter of Budget Honesty, drawing on international developments in this area. This should contribute to the development of a more comprehensive picture of total Commonwealth expenditure, irrespective of the manner in which it is delivered and provide more rigour over the selection of tax expenditure benchmarks;

- the identification of opportunities to better integrate the consideration of outlays and tax expenditures in the annual Budget process so that the cost of any new tax concession, and any potential offsetting savings, is fully considered; and

- improvements to the reliability of those tax expenditure estimates that are published, recognising that there is a balance to be struck between more reliable estimates and increasing the demands on taxpayers to provide additional information (the compliance burden).

Over the last 35 years there have been a number of Government and Parliamentary reviews of tax expenditures. However, few of the recommendations of these reviews have been adopted. As a result, each successive review reported similar shortcomings and made similar recommendations. ANAO notes that the Government has recently announced7 that, before the 2008–09 MYEFO is released, it will undertake a program-by-program review of government spending and tax concessions with the objective of increasing efficiency, transparency and accountability.

Key findings by chapter

Monitoring and reporting framework (Chapter 2)

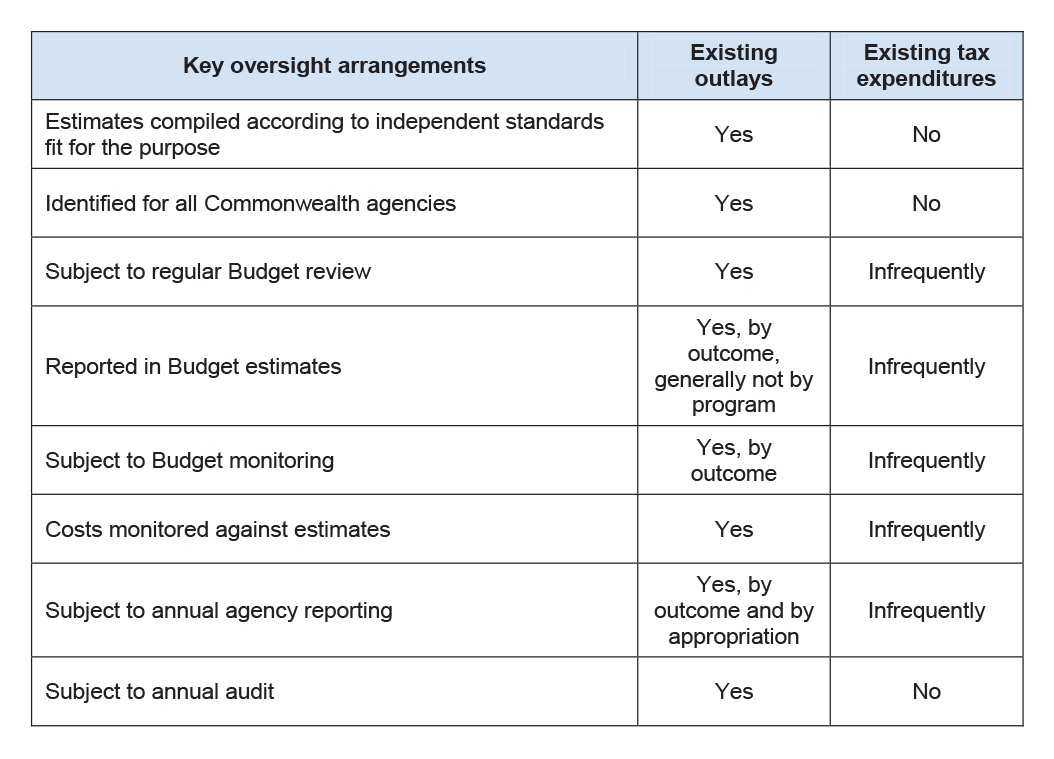

Compared to outlays, existing tax expenditures are subject to a less comprehensive management and reporting framework, as shown in the following table. This hampers the effective monitoring and scrutiny of individual tax expenditures. In many cases, it is not possible to show whether objectives are being achieved and whether the actual benefits are proportionate to the costs.

Table 1 Comparison of key management arrangements for outlays and tax expenditures

Source: ANAO analysis.

These are long-standing issues, identified by successive reviews of tax expenditures, the first of which was conducted in 1974. Each found one or more major deficiencies, including:

- poorly defined aims;

- inadequate methods, information and data with which to estimate the cost and evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of tax expenditures;

- insufficient budgetary scrutiny and consideration, both within government and by Parliament; and

- lack of regular and systematic review.

While significant improvements were suggested, including the integration of tax expenditures into the Budget process, very few of the recommendations of these reviews have been adopted. Notable exceptions are the 1986 agreement to regularly publish tax expenditures and the 1998 inclusion of tax expenditures in the reporting requirements of the Charter of Budget Honesty.

However, the tax expenditure reporting standards applied by the Charter of Budget Honesty have not been developed to account explicitly for identifying and estimating the costs of tax expenditures. Nor has there been any significant progress toward regularly evaluating tax expenditures against their objectives or integration of their consideration into the Budget process.8

Reporting all tax expenditures (Chapter 3)

Whether a tax concession is a tax expenditure and thus reported in the TES depends upon the tax benchmark adopted by Treasury. As Treasury stated in TES 2007:

[Benchmarks] vary over time and across countries and can be arbitrary.9

Although there is widespread recognition of the existence of tax expenditures, there is no universally accepted definition of the expression ‘tax expenditure'. Differentiating a tax expenditure from a benchmark tax concession is, in some cases, a matter of fine judgment. For example, different benchmarks for alcoholic beverages have been adopted notwithstanding that the consumption of alcohol, regardless of type, is a similar activity. By way of comparison, a single benchmark is used for all petroleum fuels and a single benchmark is also used for all tobacco products (on which commodity taxes are also imposed). As a result of the different benchmarks, reporting in the TES does not reflect the preferential taxation treatment (such as lower tax rates for low alcohol products) of some categories of alcoholic beverages compared to others.

The choice of benchmark can significantly affect the aggregate estimate of revenue forgone due to tax expenditures. For example, Customs duty, which has existed since 1901, was included for the first time in TES 2007. However, because of the chosen benchmark, the publication included the related tax expenditures as a negative tax expenditure (in effect, tax revenue). This had the effect of reducing the aggregate amount of reported tax expenditures in 2007–08.10 Similarly, reported tax expenditures were $2 billion lower as a result of the income tax benchmark being adjusted to treat, for the first time, assistance for low income earners as part of the benchmark rather than as a tax expenditure.

In light of the views expressed by the Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration (see above), and recognising that judgements are currently made without the benefit of reporting standards that account explicitly for tax expenditures, there would be benefit in Treasury examining opportunities to provide supplementary information in the TES. In dealing with disclosure, if the financial effect can be reliably estimated, there would be benefit in such information being reported.

Reporting accuracy (Chapter 4)

Tax expenditures are measured in the TES as deviations from the tax benchmark (that is, the tax treatment that would normally apply). TES 2006 reported total measured tax expenditures of $41.32 billion for 2006–07,11 or 17.6 per cent of that year's estimated value of all Government receipts (excluding the Goods and Services Tax). Not all tax expenditures are, or can be, estimated. Due to data limitations, TES 2006 provided quantifiable estimates for 162 (or fewer than 60 per cent) of the 272 tax expenditures that were identified. The remaining tax expenditures were unquantified.

Reliability of quantified estimates

The TES does not at present inform readers as to the reliability of the quantified estimates. In this respect, the methods used to calculate quantified estimates of individual tax expenditures reported in the TES vary. ANAO's assessment of the quantified tax expenditures was that:

- highly reliable estimates were available for 52 tax expenditures, approximately 20 per cent of all reported tax expenditures, which accounted for nearly two–thirds of the total value of all reported tax expenditure; and

- 110 tax expenditures (68 per cent) involving 35 per cent of the aggregate estimate were assessed as having medium or lower levels of reliability.12 In many cases, these estimates were based not on detailed data, but on aggregate data compiled from a range of sources, reducing the inherent reliability of the estimates.

In many cases, the reliability of estimates could be significantly improved if ATO and Treasury were able to obtain more data from other Commonwealth agencies or from taxpayers. Treasury advised ANAO that the trend to reducing the compliance burden on taxpayers results in less information being reported from which estimates can be made and that this situation also affects alternative sources of information such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ANAO also observed that the capacity of the ATO and Treasury to develop tax expenditure estimates depended, in large part, on adopting the less accurate revenue forgone method rather than the revenue gain method. Revenue forgone is easier to estimate as it does so with the minimum of data. However, it cannot easily incorporate estimates of behavioural effects as taxpayers respond to a tax concession.

Alternatively, the revenue gain method includes incentive effects and allows for the behaviour of taxpayers, though at the cost of greater analysis and consequential data requirements. Revenue gain is the method currently used for reporting estimates of new revenue measures in the Budget papers.

The different methodologies adopted in the Budget papers and in the TES impedes analysis of the actual cost of new tax expenditures in terms of what was expected when they were introduced. Accordingly, in the longer term there would be benefits in Treasury and the ATO identifying opportunities to produce estimates of large or otherwise significant tax expenditures using the revenue gain method.

Tax expenditures that are not quantified

In the case of some tax expenditures, especially those involving tax exempt transactions, such as fringe benefits, data sources are presently very poor or non-existent. As a result, TES 2006 reported 98 unquantifiable tax expenditures. For 77 of these, a general order of magnitude was indicated (ranging from around $1 billion down to zero), on the pragmatic basis that it is better to report some estimate than no estimate at all. Nonetheless, for 21 tax expenditures, it was not possible for Treasury to estimate even a general order of magnitude, so deficient was the underlying data.

General estimates are available that would allow qualified reporting of approximately $15 billion tax expenditures which have yet to be quantified in the TES. They relate to the capital gains exemption of the sale of the principal residence (approximately $13 billion), the tax exemption of certain State and Territory business enterprises ($2 billion) and a negative tax expenditure relating to the deductibility of higher education charges ($110 million).

Agency responses

Copies of the proposed report were provided to Treasury, the ATO and Customs. Each agency provided comments on the proposed report. Treasury also provided a response to each of the six audit recommendations with ATO providing a response to part of one recommendation and all parts of another recommendation.13 In addition, Treasury and the ATO provided the following overall comments on the report.

Treasury overall comments

The Treasury regards the publication of the annual TES as an integral part of the Australian Government's Budget reporting. The TES allows for greater scrutiny of government assistance to taxpayers and other interventions in the economy that are achieved through the tax system and contributes to the design of the tax system by promoting and informing public debate on the tax system. Treasury considers that the reporting of tax expenditures will continue to improve through greater use of data held by other agencies and disclosure of the reliability of estimates.

Treasury notes that in respect of improving the reliability of the TES estimates, availability of data is the key constraint. In this regard the benefits from improving the reliability of estimates must be weighed against the cost of increasing the compliance cost burden on taxpayers.

ATO overall comments

The ATO believes that TES estimates will continue to improve through the better use of data held outside the organisation. In addition, we agree that proposed commentary around the reliability of estimates will improve the transparency of the estimates adopted.

The ATO does not believe there is much scope to directly impose additional compliance cost burdens on taxpayers where the sole purpose is to measure the value of tax expenditures.

Footnotes

1 Commonwealth of Australia, Tax Expenditures Statement 2006, February 2007, pp. 1–2.

2 Tax expenditure estimates are calculated on an individual basis and do not take account of potential overlaps with other tax expenditures. In this respect, TES 2007 notes (p. 17) that ‘While aggregate tax expenditure estimates can provide a guide to trends in tax expenditures over time, overlaps between the coverage of different tax expenditures and likely behavioural responses to their removal mean that such aggregates are not a reliable indicator of the overall budgetary impact of tax concessions.

3 There was a one-year break in the publication of the TES during the transition to accrual budgeting and to The New Tax System and The New Business Tax System.

4 Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration, Transparency and accountability of Commonwealth public funding and expenditure, March 2007, p. 33.

5 ibid.

6 Defined in the CBH Act as:

- the concepts and classifications set out in Australian System of Government Finance Statistics (GFS) economic reporting standard developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics; and

- public sector accounting standards developed by the Public Sector Accounting Standards Board.

7 The Hon Lindsay Tanner MP, Minister for Finance and Deregulation, Address to National Press Club Canberra Wednesday 6 February 2008, p. 4.

8 For example, the sequence of Budget consideration (outlay measures before revenue measures) means that related outlay and revenue programs are not usually considered in conjunction with each other. In addition, the offsetting and savings requirements for revenue measures are more restrictive than for outlays programs which has tended to discourage the replacement of tax concessions with equivalent outlays programs.

9 Treasury, Tax Expenditures Statement 2007, 25 January 2007, p. 21.

10 Treasury advised ANAO that the impact of incorporating the zero tariff benchmark into the 2007 TES was a reduction in aggregate tax expenditures of around $3.7 billion in 2007–08.

11 TES 2007 was published during the course of this audit. It reported total measured tax expenditures for 2006–07 of $50.12 billion.

12 Among the major tax expenditures so affected are family tax benefit ($2 430 million in 2006–07), tax offsets for senior Australians ($1 870 million), care benefits ($1 070 million), exempt income support benefits, pensions or allowances ($970 million), deductions to charities ($640 million), local government tax exemptions ($570 million), withholding tax exemptions ($550 million), exempt war–related payments and pensions ($440 million), and child care benefits ($410 million).

13 The ATO advised ANAO that it has administrative responsibility for the vast majority of the tax expenditures but that Treasury has responsibility for publishing the TES, and reviewing the existing program of tax expenditures. The ATO further advised that, in relation to the TES, its role is to assist the Treasury with their preparation and that, hence Treasury is better placed to respond to most of the audit recommendations.