Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

National Indigenous Australians Agency’s Management of Provider Fraud and Non-compliance

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- In 2021–22 the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) funded more than 1000 external providers to deliver about 1500 Indigenous Advancement Strategy activities at a cost of $1.03 billion.

- Effective management of provider fraud and non-compliance reduces risk to the proper use of public resources and to the performance and availability of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Key facts

- Australian Government requirements oblige officials to consider fraud risks throughout the grants management lifecycle.

- The NIAA introduced a new approach to integrated program compliance and fraud management in April 2021.

- Non-compliance and fraud matters are dealt with as minor matters, ‘intensive support compliance matters’, compliance reviews or fraud investigations.

What did we find?

- The NIAA’s management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks is partly effective.

- The NIAA’s frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance are not fully fit-for-purpose.

- The NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention, detection and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance are partly effective.

- The arrangements for the NIAA’s triage, management and resolution of referred matters related to potential provider fraud and non-compliance are partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were seven recommendations aimed at ensuring the NIAA meets its obligations under Commonwealth legislation for risk and fraud management and effectively manages provider fraud and non-compliance risks.

- The NIAA agreed with all recommendations.

77 and 36

Number of intensive support compliance matters in 2019–20 and 2021–22, respectively

1232 days

Average number of calendar days to finalise a compliance review in 2021–22

0

Number of provider fraud investigations commenced in 2021–22

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) is an executive agency under section 65 of the Public Service Act 1999 and is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity as defined by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). The NIAA is the lead entity for the Commonwealth policy development, program design, implementation and service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

2. The Australian Government funds and delivers programs for Indigenous Australians through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS). In 2021–22, the NIAA funded, through grant programs, more than 1000 external providers to deliver about 1500 IAS activities at a cost of $1.03 billion.

3. In a December 2022 program compliance and fraud management framework, the NIAA stated that it has a low tolerance for minor or careless ongoing non-compliance with grant agreements by providers, particularly where it impacts or disrupts services to the community. In a December 2020 Risk Management Policy, the NIAA stated that it has a zero tolerance for criminal activity and breaches of the law, including dishonest, fraudulent or corrupt behaviour. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 and the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines 2017 (CGRGs) require Australian Government officials to consider fraud risks throughout the grants management lifecycle.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The IAS is one of the means through which the Australian Government seeks to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Grants funded under the IAS represent a significant commitment of public money across many activities and are delivered by a large number of service providers. Effective management of provider fraud and non-compliance reduces risk to the proper use of public resources and to the performance and availability of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The audit will assure the Parliament that the NIAA has effective arrangements to manage provider fraud and non-compliance risks, thereby supporting the integrity of programs aimed at improving the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the NIAA’s management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks.

6. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Are the NIAA’s frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance fit-for-purpose?

- Are the NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention, detection and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance effective?

- Are the NIAA’s arrangements for responding to matters referred as potential provider fraud and non-compliance effective?

7. The audit examined the period July 2020 to December 2022.

Conclusion

8. The NIAA’s management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks is partly effective.

9. The NIAA’s frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance are not fully fit-for-purpose. There is a risk management framework and a risk-based conceptual approach for managing provider fraud and non-compliance risks. The frameworks for managing fraud and provider non-compliance do not fully comply with legislation or the NIAA’s internal policies. Elements of the provider fraud and non-compliance framework, such as the underlying policies and procedures, are not always aligned. There are weaknesses in the design and implementation of governance and assurance mechanisms.

10. The NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention, detection and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance are partly effective. Prevention is not consistently or sufficiently considered in grant design and planning, and training is out of date. Detection relies primarily on complaints being raised and arrangements to deal with complaints are appropriate. Proactive detection controls are not sufficiently implemented. Referral and escalation arrangements exist, however these require greater clarity.

11. The arrangements for the NIAA’s triage, management and resolution of referred matters related to potential provider fraud and non-compliance are partly effective. There are policies, standard operating procedures, and functional areas with responsibility for triaging matters, however criteria informing the initial response to referred matters are not transparent or consistent. Data collection does not support performance measurement. For managed matters, closure reports are not consistently prepared, timeliness is not sufficiently monitored and record keeping is not fit-for-purpose. The NIAA collects some lessons learned through a variety of processes. This could more effectively inform changes to systems and processes.

Supporting findings

Frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance

12. The NIAA has established frameworks for risk and fraud management, including a specific focus on provider fraud and non-compliance risks. There is a fit for purpose risk management framework, however enterprise, group, fraud and program risk assessments are not aligned to requirements under the framework. The NIAA does not comply with subsections 10(a) and 10(b) of the PGPA Rule which require the entity to conduct fraud risk assessments regularly and to develop and implement a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a fraud risk assessment. A provider fraud and non-compliance framework (called the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework, or ICFF) was endorsed in 2021. The ICFF provides a risk-based conceptual approach for managing provider fraud and non-compliance risks. At February 2023 many of the underpinning components of the ICFF (that is, the supporting policies and procedures) had not been developed or updated to align with the overarching principles and approach. Implementation of the ICFF was ongoing, however requirements for its effective implementation (including IT systems, record keeping, governance mechanisms and reporting) were not yet mature. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.33)

13. The NIAA has established governance and assurance mechanisms for provider fraud and non-compliance risks. There are weaknesses in how these arrangements are implemented. Executive committees exist to provide oversight of the management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks by line areas. The Audit and Risk Committee’s annual reports to the accountable authority did not highlight known deficiencies in fraud and risk management. The operation of executive committees has not always been in accordance with terms of reference and committees have not been held to account for non-delivery of their terms of reference. This has weakened accountability. The NIAA has established assurance arrangements over grants management. There are weaknesses in the monitoring of improvement activities. (See paragraphs 2.36 to 2.62)

Prevention, detection and referral

14. Provider fraud and non-compliance risks are not consistently or sufficiently considered as part of grant design and establishment processes. A new grant design strategy requirement was introduced in March 2022 which incorporates risk assessment, including the consideration of fraud risks. At February 2023 there were eight new, revised or extended grant opportunities. Of these one had a finalised risk assessment that considered fraud risks. Key documentation given to providers offers information about the Australian Government’s and NIAA’s position on fraud. Provider risks are assessed in the grant establishment process through provider and activity risk profiles and these cover fraud risk to some extent. There are weaknesses in how this is used to understand aggregated risks at the sub-program level. The Program Compliance and Fraud Branch has not provided adequate monitoring, review or reporting on fraud risk assessments. Relevant mandatory and non-mandatory training is offered, however the training is out of date. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.30)

15. In relation to reactive detection activities, the NIAA’s arrangements to receive complaints (including about potential fraud) and public interest disclosures are effective. The NIAA undertakes few proactive detection activities. The level of maturity of the NIAA’s use of data analysis for proactive detection of fraud and non-compliance is low and the NIAA does not consider acquittals or ongoing performance monitoring to be proactive fraud detection methods. There was no fraud and corruption control testing between July 2020 and December 2022. (See paragraphs 3.31 to 3.43)

16. The NIAA has developed arrangements for the escalation and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance matters. The Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework includes guidance for referral and escalation. The guidance lacks clear information about timelines, resourcing, record keeping and feedback. (See paragraphs 3.45 to 3.53)

Response to referred provider fraud and non-compliance

17. The NIAA has established arrangements for its initial response to potential provider fraud and non-compliance matters. There are policies and procedures for the allocation of referred matters, and there is an intake team to rate matters and undertake triage. A separate ‘case advisory group’ is responsible for decision-making on all fraud and more serious non-compliance matters. The NIAA has not established clear criteria for allocating matters to different treatment categories, or for prioritising those matters. Criteria are not aligned with the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework and — for fraud matters — are inconsistent with the NIAA’s stated risk appetite. The absolute number of non-compliance and fraud matters requiring more than a ‘minor’ response has decreased over three years. There is insufficient data collected to understand why this is the case, or to enable an assessment of whether recent reforms to the NIAA’s approach to managing non-compliance are having the intended impact. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.36)

18. The NIAA has policies and procedures for investigation and resolution of fraud and non-compliance matters. Compliance review scoping and fraud investigation plans were prepared for all matters examined by the ANAO and contained most of the required elements. Closure reports were prepared for compliance reviews, however they lacked information on lessons learned. Closure reports were not consistently prepared for fraud investigations and those that were prepared were often not compliant with requirements. NIAA data on the number of investigations completed was not robust. Timeliness service standards were established only for compliance reviews, and only from July 2022. Timeliness of ISCMs, compliance reviews and fraud investigations is not monitored by the NIAA, and the decision to undertake a review or investigation is not reassessed after long durations or periods of suspension. Relative backlog increased between 2020–21 and 2021–22 for administrative reviews. Record-keeping for compliance reviews and fraud investigations is deficient, with the NIAA acknowledging there is ‘no single source of truth’. (See paragraphs 4.37 to 4.68)

19. The ability for the NIAA to use lessons learned from provider fraud and non-compliance management to inform changes to systems and processes is reduced by insufficient identification of lessons learned, inadequate assignment of action owners and insufficient monitoring. (See paragraphs 4.70 to 4.76)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.12

The National Indigenous Australians Agency fully implement its Risk Management Policy and Framework, including by conducting assessments of enterprise risks; and undertaking risk assessments when developing business plans, designing new policies and programs, and undertaking specific activities.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.34

The National Indigenous Australians Agency:

- conduct fraud risk assessments regularly; and

- develop and implement a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.44

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensure that:

- advisory committee activities are in line with approved terms of reference; and

- the National Indigenous Australians Agency Audit and Risk Committee’s annual report to the accountable authority clearly highlights known deficiencies in the risk management and control framework.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.24

The National Indigenous Australians Agency fully implement program and sub-program fraud risk assessments, organisational risk profiles, activity risk assessments and monitoring and review of fraud risk assessments.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.43

The National Indigenous Australians Agency implement proactive mechanisms for the detection of provider fraud and non-compliance.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.33

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensure that:

- it maintains a record of all referrals, including triage outcomes; to support analysis of trends in referrals and Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework performance measurement;

- the basis for initial assessment of compliance reviews is in line with the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework;

- decision-making on initial assessment is guided by clear and transparent criteria; and

- the decision whether or not to proceed with a fraud investigation reflects the National Indigenous Australians Agency’s risk appetite.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.68

The National Indigenous Australians Agency monitor and report on the resources, time and outcomes of compliance reviews and fraud investigations.

National Indigenous Australians Agency: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

20. The NIAA provided a summary response shown below. The full response from the NIAA is at Appendix 1. The improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are at Appendix 2.

The National Indigenous Australians Agency welcomes the audit report and agrees with all recommendations. The opportunities for improvement identified in the audit report, in conjunction with the work already underway to enhance practices and processes, support the Agency’s continuous improvement of its management of risk, provider fraud and non-compliance.

The Agency partners with approximately 1,200 organisations to deliver 1,500 activities across Australia under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy. In addition to centralised teams dedicated to issues related to grants management, provider fraud and non-compliance, the Agency has staff working with local communities and organisations in urban, regional and remote locations across Australia. Strong local relationships mean the Agency has visibility of the activities being delivered and outcomes achieved and is in touch with any issues that emerge.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and which may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

National Indigenous Australians Agency

1.1 The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) is an executive agency under section 65 of the Public Service Act 1999 and is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity as defined by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). The NIAA was established within the Prime Minster and Cabinet portfolio on 1 July 2019 and is the lead entity for the Commonwealth policy development, program design, implementation and service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.1

1.2 The NIAA purpose is described in the following way in its 2022–23 Corporate Plan.

The NIAA works in genuine partnership to enable the self-determination and aspirations of First Nations communities. We lead and influence change across government to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a say in the decisions that affect them.2

1.3 The accountable authority of the NIAA under the PGPA Act is the Chief Executive Officer. At 30 June 2022 the NIAA had 1332 employees in Canberra, other capital cities and regional and remote areas, with the majority (59 per cent) in Canberra.

Indigenous Advancement Strategy

1.4 The Australian Government funds and delivers programs for Indigenous Australians through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS). Agreed outcomes are to be achieved through seven Portfolio Budget Statements programs.3 In this report, where reference is made to programs and sub-programs, the reference relates to grant programs and sub-programs which are at a level below those described in the Portfolio Budget Statements.

1.5 In 2021–22 the NIAA funded, through grants, more than 1000 external providers to deliver about 1500 IAS activities at a cost of $1.03 billion.4 Auditor-General Report No. 11 2020–21, Indigenous Advancement Strategy – Children and Schooling Program and Safety and Wellbeing Program, examined two IAS grant programs. The report found that the NIAA’s administration of the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs was largely effective. It found that the management of grants was largely consistent with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs), although performance information was not fully appropriate.

Provider fraud and non-compliance

1.6 In 2021–22 the NIAA provided grants funding to over 1000 service providers to deliver activities related to the IAS. Grant funding is provided through grant opportunity guidelines, grant agreements and project schedules.

1.7 In a December 2022 program compliance and fraud management framework, the NIAA stated that it has a low tolerance for minor or careless ongoing non-compliance with grant agreements by providers, particularly where it impacts or disrupts services to the community. In a December 2020 Risk Management Policy, the NIAA stated that it has a zero tolerance for criminal activity and breaches of the law, including dishonest, fraudulent or corrupt behaviour.

1.8 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 and the CGRGs require Australian Government officials to consider fraud risks throughout the grants management lifecycle. In May 2022 the Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre released a Grants Administration Counter Fraud Toolkit (toolkit), which provides information on identifying and mitigating fraud risks, including provider fraud risks, within the grants management lifecycle. The toolkit highlights that:

While grants are necessary to achieve key government objectives, they also carry fraud risks. These risks are often elevated when a grant program is designed and delivered rapidly and/or with limited resources. The risks can also vary based on the type of grant. Fraud against Australian Government entities is becoming increasingly dynamic. People are using advanced and coordinated methods to target multiple government programs that could cost billions per year. Australian Government entities must have a good understanding of fraud risks to put in place effective countermeasures to reduce these risks – including detective and investigative countermeasures to deal with fraud that is not prevented.5

1.9 Potential provider fraud risks include: misrepresentation of identity; applicants using fictitious organisations; applicants falsifying information to receive a grant payment; grantees using funds for improper purposes; grantees inflating costs; grantees substituting materials or services; and grantees receiving duplicate grants.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.10 The IAS is one of the means through which the Australian Government seeks to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Grants funded under the IAS represent a significant commitment of public money across many activities and are delivered by a large number of service providers. Effective management of provider fraud and non-compliance reduces risk to the proper use of public resources and to the performance and availability of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The audit will assure the Parliament that the NIAA has effective arrangements to manage provider fraud and non-compliance risks, thereby supporting the integrity of programs aimed at improving the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the NIAA’s management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks.

1.12 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Are the NIAA’s frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance fit-for-purpose?

- Are the NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention, detection and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance effective?

- Are the NIAA’s arrangements for responding to matters referred as potential provider fraud and non-compliance effective?

1.13 The audit examined the period July 2020 to December 2022.

Audit methodology

1.14 The audit methodology included:

- examination of NIAA strategy, policies, procedures, frameworks and guidelines relevant to risk management and fraud prevention, detection and reporting;

- review of Executive Board6 and committee papers and minutes;

- review of internal and management reporting, including those related to conduct of fraud investigations and compliance activities;

- analysis of data relating to providers, grants, fraud investigations and compliance activities;

- examination of management-initiated reviews, internal audits and assurance reports related to grants management, risk management and fraud prevention and detection; and

- meetings with NIAA staff.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $537,000.

1.16 The team members for this audit were Peter Bell, Susan Ryan, Elizabeth Robinson and Christine Chalmers.

2. Frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) has established fit-for-purpose frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance.

Conclusion

The NIAA’s frameworks for managing provider fraud and non-compliance are not fully fit-for-purpose. There is a risk management framework and a risk-based conceptual approach for managing provider fraud and non-compliance risks. The frameworks for managing fraud and provider non-compliance do not fully comply with legislation or the NIAA’s internal policies. Elements of the provider fraud and non-compliance framework, such as the underlying policies and procedures, are not always aligned. There are weaknesses in the design and implementation of governance and assurance mechanisms.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at ensuring the NIAA improves its risk and fraud frameworks; and that advisory committee decision-making is aligned to terms of reference.

2.1 Section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) establishes the duty for the accountable authority of a non-corporate Commonwealth entity to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control. Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires the accountable authority to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity.

2.2 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy outlines mandatory policy and framework requirements which must be implemented by Commonwealth entities as well as better practice guidelines.7

2.3 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 outlines the Australian Government’s requirements for fraud control by Commonwealth entities. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework8 consists of three tiered documents: the fraud rule (section 10 of the PGPA Rule), the Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy and fraud guidance.9 The fraud rule is aimed at ensuring there is a minimum standard for accountable authorities of Commonwealth entities for managing the risk and incidents of fraud. As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, the fraud rule and policy are binding on the NIAA. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework requires a fraud control program that covers prevention, detection, investigation and reporting strategies.

How effectively do the provider fraud and non-compliance frameworks meet Commonwealth requirements for risk and fraud management?

The NIAA has established frameworks for risk and fraud management, including a specific focus on provider fraud and non-compliance risks. There is a fit for purpose risk management framework, however enterprise, group, fraud and program risk assessments are not aligned to requirements under the framework. The NIAA does not comply with subsections 10(a) and 10(b) of the PGPA Rule which require the entity to conduct fraud risk assessments regularly and to develop and implement a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a fraud risk assessment. A provider fraud and non-compliance framework (called the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework, or ICFF) was endorsed in 2021. The ICFF provides a risk-based conceptual approach for managing provider fraud and non-compliance risks. At February 2023 many of the underpinning components of the ICFF (that is, the supporting policies and procedures) had not been developed or updated to align with the overarching principles and approach. Implementation of the ICFF was ongoing, however requirements for its effective implementation (including IT systems, record keeping, governance mechanisms and reporting) were not yet mature.

Risk management

2.4 On 17 December 2020 the NIAA Executive Board endorsed the NIAA Risk Management Policy and NIAA Risk Management Framework (NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework).

2.5 The NIAA Risk Management Policy outlines the accountabilities and requirements for managing risk within the NIAA. The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is responsible for endorsing and championing the NIAA’s Risk Management Framework; determining and articulating the NIAA’s risk appetite and tolerance; establishing and maintaining an appropriate system of internal controls; and reporting on the NIAA’s key risks to the responsible Minister. The Executive Board is responsible for the management and oversight of the efficient, effective and ethical use of resources; the management and oversight of NIAA enterprise risks; and planning and allocating resources to meet current and future work priorities in order to effectively manage risk. The Audit and Risk Committee is responsible for monitoring and reviewing the effectiveness of the risk management framework and policy; and providing assurance to the accountable authority on the existence and operation of controls.10 Other risk management responsibilities are assigned to other governance committees, deputy CEOs, the Chief Risk Officer, the Chief Operating Officer, senior management and ‘all officials’ of the NIAA.

2.6 The NIAA Risk Management Policy provides a statement of risk appetite and tolerance and the NIAA risk matrix to be used when preparing risk assessments.

2.7 The NIAA Risk Management Framework sets out a principles-based approach to risk management and the context and terminology to be used by the NIAA. This document refers to Risk Assessment Guidance and a template to be used when assessing risks. The NIAA Risk Management Framework articulates the three ‘levels’ of risks within the NIAA.

- External risks — factors in the NIAA environment and external forces that may impact on the NIAA’s chances of success. These risks are not assessed or managed by the NIAA although they will likely be sources of enterprise and operational risks.

- Enterprise risks — outlined in the corporate plan and affect the organisation as a whole. The Risk Management Framework identifies several risk assessment processes that examine enterprise risks including group, safety, fraud, security and program risks.

- Operational risks — the day-to-day risks relating to individual branch activities, projects or operational processes.

2.8 The NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework are consistent with the requirements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 2014. The purpose of the NIAA Risk Assessment Guidance is to support officials and staff in conducting formal risk assessments, including the use of the risk assessment template. The Risk Assessment Guidance states that, at a minimum, formal risk assessments should be conducted when developing business plans; planning or designing new policies and programs; undertaking a specific activity, event or project; and considering key investment and procurement decisions; or as required by any other policies or frameworks, such as a work health and safety policy.

2.9 Risk assessments were not prepared or reported on in line with the NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework and Risk Assessment Guidance.

- Enterprise risk assessment — Enterprise risks and mitigations are identified at a high level in the NIAA corporate plan; and in an ‘enterprise risk register’. Neither the corporate plan nor the enterprise risk register assess the risks based on their likelihood and consequence, indicate whether the risks are within the NIAA’s tolerance for risk, or assign risk owners. Although NIAA documentation states that the enterprise risk register is not intended ‘to be a formal assessment and rating of risks’ these elements of risk assessment are not performed elsewhere. The enterprise risk register instructs users to ‘Ensure timeframes and accountability for each [mitigation] is included’; however, this is not done.

- Group, fraud and program risk assessments — An examination by the ANAO of 64 group, program and fraud risk assessments prepared between January 2021 and December 2022 indicated that none of the risk assessments examined for this period met all of the requirements of the Risk Assessment Guidance.11 The ANAO identified deficiencies related to: the identification of controls; assessment of likelihood and consequence; and treatment plans (such as due date for application of the treatment and treatment owners). Moreover, approvals of the risk assessments were not consistently evidenced as required by the Risk Assessment Guidance and the template.

2.10 In December 2020 the Executive Board was provided with a risk management implementation plan. The risk management implementation plan included tasks (risk assessment tools; reporting; and culture) to be undertaken to facilitate the embedding of risk management in line with the new NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework and Risk Assessment Guidance. An implementation deadline for tasks was not always identified. The Executive Board received updates between February 2021 and September 2021. An update on the status of the risk management implementation plan was provided to the Audit and Risk Committee in November 2021. The update identified that key tasks (consultation to achieve a common risk framework; review of risk reporting; risk training; committee terms of reference including risk reporting) had not yet been completed. No further update was provided to the Executive Board or the Audit Committee on risk management or implementation plan progress until March 2023, when an update on implementation progress was provided to the Audit and Risk Committee.

2.11 From January 2023 a revised Commonwealth Risk Management Policy came into force.12 In February 2023 the NIAA advised the ANAO that it is considering how risk management policies, frameworks and guidance address the relevant changes to the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy.

Recommendation no.1

2.12 The National Indigenous Australians Agency fully implement its Risk Management Policy and Framework, including by conducting assessments of enterprise risks; and undertaking risk assessments when developing business plans, designing new policies and programs, and undertaking specific activities.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

2.13 In line with the Department of Finance’s Risk Management Capability Maturity Model, risk capability and risk management practices have been identified by the Agency as opportunities to further strengthen existing processes. This is a focus for the Agency going forward and work is already underway to continue to embed the Risk Management Framework and Policy.

2.14 The ANAO’s findings will inform the current implementation plan, which includes:

- Improved processes to report and monitor risks across the agency.

- Requiring detailed risk assessments at the Branch and Region level as part of the business planning process for the 2023–24 financial year.

- Enhanced staff training to support the proactive identification, management and escalation of risk.

Provider non-compliance and fraud risk management

2.15 The enterprise risk information included in NIAA corporate plans does not identify provider fraud or non-compliance risk. However, the implementation of an ‘Integrated Compliance and Fraud Management Framework’ was identified as a key mitigation for enterprise ‘delivery’ risks.

2.16 In October 2020 the Executive Board endorsed the development of a framework that was intended to integrate program compliance and fraud management in NIAA planning and business processes across the grants management lifecycle. Yardstick Advisory was engaged in December 2020 to further develop existing frameworks into an Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework (ICFF). The ICFF was endorsed by the Executive Board in April 2021.

2.17 The ICFF was intended to address issues identified by the NIAA in relation to provider non-compliance and fraud control. This included that the approach to non-compliance had been primarily reactive rather than proactive, with a reliance on dedicated compliance and fraud teams to address issues of non-compliance or serious risk. To mitigate this issue, the ICFF defined roles and responsibilities for responding to compliance issues and set out a graduated approach to issue escalation. This included when grant agreement managers should respond to a compliance issue themselves and when matters should be escalated to the dedicated compliance and fraud team. By identifying different levels of seriousness of program non-compliance and associated escalation approach, the ICFF was to provide a basis for directing specialist resources to more serious program non-compliance.

Figure 2.1: Levels of seriousness of program non-compliance

Source: ANAO analysis of the escalation approach included in Appendix D of the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework (June 2021).

2.18 The endorsed ICFF document was released to NIAA staff in June 2021 and formally launched in August 2021 with a video presented by the Deputy CEO. At the time of its launch, many of the underpinning components of the framework had not been developed or updated. An assessment of the ICFF against Australian Government requirements for fraud and risk management (Table 2.1) shows that, at February 2023, the ICFF was relying on risk and fraud management policies and processes that were deficient or not fully consistent with the principles expressed in the ICFF.

Table 2.1: Comparison of ICFF implementation to Australian Government requirements for fraud and risk management, February 2023

|

Source |

Requirement |

Analysis |

|

Section 16 of the PGPA Act and the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy |

Section 16 of the PGPA Act establishes the duty for the accountable authority of a non-corporate Commonwealth entity to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy outlines mandatory policy and framework requirements which must be implemented by Commonwealth entities. |

The ICFF refers to and relies on the application of the NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework. As noted in paragraphs 2.4 to 2.11, the NIAA’s Risk Management Policy and Framework has not been fully implemented, particularly in relation to the assessment of risks (including fraud risks). |

|

Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines 2017 (CGRGs) |

Paragraph 13.3 of the CGRGs states that probity and transparency in grants administration is achieved by ensuring that grants administration by officials and grantees incorporates appropriate safeguards against fraud, unlawful activities and other inappropriate conduct. |

The ICFF relies on supporting policies and procedures to be updated in a timely manner to reflect the principles and requirements of the ICFF. The NIAA updated the Grant Risk Management Guidelines (which outline how to assess and manage risks associated with grantees and grant activities) in September 2022, almost two years after changes were made to the NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework. In February 2023 the NIAA advised the ANAO that it is in the process of further updating the Grants Administration Manual to reflect new processes and approaches. |

|

PGPA Rule 10: Preventing detecting and dealing with fraud |

Section 10 of the PGPA Rule requires the accountable authority to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 outlines the Australian Government’s requirements for fraud control. It requires that government entities put in place a fraud control approach that covers prevention, detection, investigation and reporting strategies. |

The ICFF refers to and relies on the application of the NIAA Fraud and Corruption Control System (FCCS). As noted in paragraphs 2.22 to 2.33, the NIAA’s approach to fraud control has deficiencies. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework (June 2021).

2.19 Table 2.2 shows that the implementation of the ICFF is not fully embedded in NIAA practices at February 2023.

Table 2.2: ICFF supporting standards, policies, procedures and systems, February 2023

|

Area examined |

Analysis |

|

Adherence to AS ISO 19600:2015 (the international standard for compliance management systems) |

Although AS ISO 19600:2015 has not been adopted by the NIAA, the ICFF states that its design took the standard into account. The NIAA was unable to provide evidence of any assessment or consideration of AS ISO 19600:2015 in the development of the ICFF and stated that it was not its intention to align the ICFF to the standard in full.a |

|

Policies, procedures and guidance reflecting the principles and approach outlined in the ICFF |

NIAA policies and procedures developed after August 2021 do not always consider the ICFF. For example, an April 2022 Compliance, Fraud and Complaints Standard Operating Procedures Manual (that outlines prioritisation protocols and work flows) and July 2022 Compliance Control and Management Standard Operating Procedures (that outline the procedures for dealing with compliance activities) do not reflect the terminology of the ICFF or ICFF prioritisation protocols. Both documents refer to the ICFF and indicate that staff should familiarise themselves with the ICFF (see paragraph 4.5). |

|

Development of systems and mechanisms to support ICFF implementation |

The ICFF identifies requirements for its implementation including IT systems, record keeping, continuous improvement, governance mechanisms and reporting. At February 2023 the ICFF is not yet fully supported by identified systems, policies, procedures or guidance. Refer to paragraph 2.21 for information on the ICFF implementation plan. |

Note a: Some of the components of AS ISO 19600:2015 are an independent compliance function; a compliance risk assessment; a compliance policy including a compliance objective; and a documented scope of the compliance management system. These are not reflected in the ICFF.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Integrated Program Compliance and Fraud Management Framework (June 2021).

2.20 In March 2021 the Audit and Risk Committee was provided with a copy of the draft ICFF and implementation plan. The draft implementation plan sets out tasks related to finalisation of the ICFF and implementation plan, and activities to develop: staff capability; business processes and controls; risk management; stakeholder engagement; IT systems and record keeping; compliance and fraud case management; governance and reporting; and continuous improvement. Due dates were not included for all tasks identified in the draft ICFF implementation plan. In June 2021, when the Audit and Risk Committee queried the timeframe for ICFF implementation, it was told that the work would take place over 18 months. In April 2023 the NIAA advised the ANAO that the next steps in implementing the ICFF were paused pending the outcomes of the ANAO performance audit.

2.21 In July 2021 the NIAA established a senior executive service working group of the Program Performance Committee13 to finalise the development of the ICFF implementation plan, including prioritising actions, assigning lead responsibility, identifying necessary resourcing and estimating timeframes. A number of draft ICFF implementation plans (both high level and detailed) were prepared. There are over 100 activities and tasks to facilitate implementation in the detailed implementation plans. The implementation plans were discussed at the working group five times between July 2021 and May 2022. The minutes of these meetings were subsequently provided to the Program Performance Committee. At February 2023 the Program Performance Committee has not approved the implementation plan and no overall implementation completion date has been communicated to the Policy and Delivery Committee or Executive Board.

Fraud control framework

Fraud risk assessments

2.22 Subsection 10(a) of the PGPA Rule states that the entity must conduct fraud risk assessments regularly and when there is a substantial change in the structure, functions or activities of the entity. In July 2022 the NIAA CEO approved and released the NIAA Fraud and Corruption Control System 2022–24 (FCCS), which replaced the Fraud Control Plan 2020–22. The FCCS is intended to outline how the NIAA will prevent, detect and respond to fraud and corruption. The FCCS states that:

The key fraud risks have been documented in NIAA’s Fraud and Corruption Risk Register. The register establishes the NIAA’s risk profile, reflects specific fraud risk assessments, and the counter-measures in place or to be implemented to address identified risks. This includes implementing treatments to reduce fraud risk to an acceptable level within the context of the specific circumstances.14

2.23 In 2021 the NIAA prepared a document titled ‘Fraud Risk Register Working Document’ (Fraud Risk Register). This document identifies 56 fraud risk assessments in various stages of progress. In July 2022 the NIAA prepared a ‘Fraud Risk Assessment Summary’ (Fraud Risk Summary), which showed the status of fraud risk assessments known to the Program Compliance and Fraud Branch at the time of its preparation. This document identified 129 fraud risk assessments.15

2.24 In addition to being out of date and unendorsed, the Fraud Risk Register did not meet the requirements of the FCCS 2022–24 or the Fraud Control Plan 2020–22 for an effective fraud and corruption risk register. The Fraud Risk Register was a ‘stocktake’ of fraud risk assessments indicating which had been completed, were out of date or were missing. Collated fraud risk assessments did not meet all of the requirements of the NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework or the Risk Assessment Guidance. For example, where the fraud risk assessments were above risk appetite, no treatment plans had been identified. Where treatments had been identified, they were out of date without confirmation that treatments had been implemented.16

2.25 The Fraud Risk Summary was a listing of fraud assessment titles and their overall risk rating. It did not contain information on specific assessments, or counter-measures in place or to be implemented. The Fraud Risk Summary did not include reference to the Territories Stolen Generations Redress Scheme fraud risk assessment which was prepared in April 2022 and assessed the Scheme as having ‘extreme’ risk. The NIAA was unable to affirm that the Fraud Risk Summary was a complete and accurate list of fraud risk assessments, including the identification of all relevant programs and sub-programs.17

2.26 The FCCS 2022–24 and the Fraud Control Plan 2020–22 outline a rolling program of fraud risk assessments and state that fraud risk assessments for departmental and administered activities will occur at least once every two years, or when a major new activity, policy or program is developed, or when a significant organisational change occurs. Risks rated ‘low’ or ‘medium’ are to be reassessed biennially. Risks rated ‘high’ are to be reassessed at least once annually. Risks rated ‘extreme’ are to be reassessed every three months.18

2.27 Risk assessments were not conducted regularly or in accordance with the rolling program required by the NIAA.

- An overall inherent (before existing controls) and residual (after existing controls) risk rating was provided for each fraud risk assessment in the Fraud Risk Register.19 Based on the residual risk ratings included in the register, 24 of 56 fraud risk assessments (42 per cent) were not updated within time limits specified in the FCCS.

- In the Fraud Risk Summary, 26 of 129 (20 per cent) of fraud risk assessments were prepared within the timeframes set out in the FCCS. Eighty per cent were marked as ‘out of date’ or ‘unable to be located’. This spreadsheet identifies five ‘high’ or ’extreme’-rated fraud risk assessments that had not been assessed within the last 12 months.

2.28 A ‘Grant Design Strategy’ template, which is the first step in the design of a new NIAA grant program, requires that NIAA sub-programs have a risk assessment, which must include consideration of fraud risk. In completing the risk assessment, NIAA staff are required to consider the specific risks identified in the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines 2017 (CGRGs) and PGPA Rule 10.

2.29 In September 2021 a paper was provided to the Audit and Risk Committee, at its request, on the status of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) program risk profiles. The paper summarised a review conducted by Yardstick Advisory, which observed that:

overarching risk assessments do not exist at the program level and generally do not exist at sub-program levels … The absence of overarching risk assessments at these levels restricts the ability of the NIAA to manage risks across the IAS in a coordinated and structured way. Similarly, it restricts the ability to effectively examine and profile risks across the IAS.

2.30 In May 2022 the NIAA commenced development of a new ‘Fraud Risk Exposure Assessment’ process aimed at collecting information to compile a list of NIAA sub-programs and to facilitate the prioritisation of the preparation of fraud risk assessments in the NIAA. The process commenced in September 2022 with responses received and analysed in December 2022. At December 2022 a total of 64 sub-programs had provided a response and four responses were outstanding. A paper presented to the Audit and Risk Committee on 10 March 2023 stated that the 2022 Fraud Risk Exposure Assessment process had identified that over 40 sub-programs had not undergone a fraud risk assessment; that results had informed the development of a new forward-workplan to 30 June 2023, specifically the prioritisation of fraud risk assessments; and that ‘a significant body of work is required to be undertaken to enable the NIAA to meet its Fraud Rule obligations by June 2023’.

Fraud control plan

2.31 Subsection 10(b) of the PGPA Rule requires entities to develop and implement a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a fraud risk assessment. The FCCS is the NIAA’s fraud control plan. In September 2022 the Program Compliance and Fraud Branch reported to the Audit and Risk Committee that:

At the time of developing the Agency’s Fraud and Corruption Control System 2022–24 … it was identified that some fraud risk assessments for programs and functions were either overdue for completion, or had not yet been developed. Rather than delay the development and release of the Fraud and Corruption Control System 2022–24, the information available in the current fraud risk register was drawn upon to inform its development. It was also informed by the body of work undertaken in 2021 and 2022 to develop and implement the new Integrated Compliance and Fraud Framework … as well as emerging risk assessments being conducted as new programs commence (e.g. the Territories Stolen Generations Redress Scheme).

2.32 As the FCCS 2022–24 was not developed based on the identified risks in a contemporary fraud risk assessment and there was no evidence of analysis of fraud risks, the NIAA’s fraud control plan does not meet the requirements of subsection 10(b) of the PGPA Rule.

2.33 In the 2021–22 Annual Report, the NIAA accountable authority certified compliance with subsection 17AG(2) of the PGPA Rule which relates to the preparation of fraud risk assessments and fraud control plans. The accountable authority certified that all reasonable measures had been taken to deal appropriately with fraud relating to the entity.

Recommendation no.2

2.34 The National Indigenous Australians Agency:

- conduct fraud risk assessments regularly; and

- develop and implement a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

2.35 This recommendation will inform the Agency’s planned review of its Fraud Control and Corruption System 2022–2024 (fraud control plan) and risk register. The Agency has put in place improvements to the fraud risk assessment process and will continue to mature its approach to fraud risk identification, treatment and monitoring. The Agency recognises that there were some administrative deficiencies in relation to fraud risk assessments and subsequent updates to its fraud risk register during the period examined by the ANAO. However, these deficiencies did not limit the Agency’s understanding of its fraud risk operating environment.

Are provider fraud and non-compliance governance and assurance mechanisms appropriate?

The NIAA has established governance and assurance mechanisms for provider fraud and non-compliance risks. There are weaknesses in how these arrangements are implemented. Executive committees exist to provide oversight of the management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks by line areas. The Audit and Risk Committee’s annual reports to the accountable authority did not highlight known deficiencies in fraud and risk management. The operation of executive committees has not always been in accordance with terms of reference and committees have not been held to account for non-delivery of their terms of reference. This has weakened accountability. The NIAA has established assurance arrangements over grants management. There are weaknesses in the monitoring of improvement activities.

Governance and oversight

Audit and Risk Committee

2.36 Pursuant to section 45 of the PGPA Act, the NIAA accountable authority has established the Audit and Risk Committee (ARC). The NIAA ARC Charter (November 2022) sets out the role, authority, functions and membership of the ARC. The ARC comprises three members appointed by the NIAA CEO.20

2.37 A function of an audit committee under subsection 17(2) of the PGPA Rule is to review the appropriateness of the agency’s system of risk oversight and management. A 2022–23 ARC Forward Work Plan outlines a range of functions to be undertaken by the ARC related to the system of risk oversight and management, including reviewing the risk management framework and risk management of individual projects, programs and activities; reviewing the NIAA’s fraud control arrangements; reviewing significant or systemic fraud allegations, the status of ongoing investigations and the implications for the NIAA’s fraud risk assessment; and (at least annually) commissioning an entity-wide assurance map.

2.38 The NIAA ARC is required to report at least annually to the CEO on its operation and activities in the year. The operation and activities to be performed by the ARC are specified in its forward work plan. The forward work plan activities for the review of the appropriateness of the system of risk oversight and management included: major risks (individual projects, program implementation, and activities); fraud control arrangements; and fraud risks.

- In September 2021 the ARC annual report to the CEO summarised how it had discharged its responsibilities between October 2020 and September 2021. The report concluded that the NIAA’s system of risk oversight and management was appropriate and still maturing. The report was silent on whether the ARC had reviewed fraud control arrangements as set out in the Fraud Control Plan 2020–22; fraud risks; or major project, program and activity risks. The September 2021 annual report to the CEO was approved by the ARC at the same meeting where the Yardstick Advisory review was discussed (see paragraph 2.29). The Yardstick Advisory review had found that there was a lack of program risk assessments, which was impeding the NIAA’s ability to manage risk effectively.

- In September 2022 the ARC annual report to the CEO (covering October 2021 to September 2022) concluded that the NIAA’s system of risk oversight and management was appropriate with work continuing to mature it further. The 2022 annual report to the CEO did not discuss how the ARC had discharged its responsibilities in relation to oversight of the management of fraud and other risks. During the period covered by the 2022 report, the ARC had reviewed the draft FCCS (June 2022) and was provided with an update that described deficiencies in the preparation and content of the FCCS (see paragraph 2.31).

2.39 The ARC Chair also reported to the Executive Board on the activities of the ARC three times in 2022. The three reports included information on agenda items discussed at the ARC but did not include information on content or outcomes of its deliberations in relation to risk management or fraud. The reports do note that the ARC had received an update from the Program Compliance and Fraud Branch on its activities.

2.40 In November 2022 the Program Compliance and Fraud Branch updated the ARC on key drivers of program non-compliance and fraud, new dashboard reporting and information on the Branch’s activities and caseload. In addition, the NIAA reported that, ‘(i)n the long term, a business case is being prepared to procure a more contemporary case management system’. The ARC asked for additional information to be included in existing fraud reporting about fraud at the strategic, regional and tactical local level.

Executive committees

2.41 The NIAA CEO has established a range of executive committees to support the discharge of the accountable authority’s roles and responsibilities. The committees relevant to the oversight and management of provider fraud and non-compliance are illustrated in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: NIAA executive committees relevant to provider fraud and non-compliance

Source: ANAO analysis of the NIAA committee structure relevant to provider fraud and non-compliance.

2.42 A description of each executive committee is provided below.

- Executive Board — The Executive Board’s role is to support the CEO. This encompasses leadership, culture, capability and performance. The Executive Board sets the NIAA’s strategic direction, policy priorities and reform agenda; manages resources; and oversees operations, the use of resources and risk management.

- Policy and Delivery Committee (PDC) — The PDC is an advisory body to the Executive Board. The PDC’s stated aim is to help drive and operationalise the strategic agenda of the NIAA through improved oversight of the NIAA’s policies, and implementation and delivery activities. Between July 2020 and December 2022 the PDC considered information related to grants, risk, fraud and ICFF implementation. The PDC terms of reference state that the PDC must seek Executive Board endorsement or noting of key decisions. The Executive Board receives the minutes of PDC deliberations.

- Program Performance Committee (PPC) — The PPC is a sub-committee of the PDC. It is designed to act as an ‘operational clearing house’ by bringing together experts and practitioners to solve problems that could impede effective and efficient management of the IAS. The terms of reference state that the PPC is not a decision-making group or responsible for the executive management of its functions and that the PPC reports to the Executive Board through the PDC following each meeting.

- ICFF Working Group — The ICFF Working Group was established in July 2021. Terms of reference for the ICFF Working Group had not been approved by the PPC at February 2023. The draft terms of reference state that the functions of the ICFF Working Group include to guide the development and implementation of the ICFF and Grant Assurance Framework. It does not have decision-making authority or responsibility for the executive management of these functions. ICFF Working Group minutes are provided to the PPC.

2.43 The ICFF states that the Chief Operating Officer is responsible for approving any amendments to the ICFF, with substantive changes to be considered by the Executive Board. In August 2022 the ICFF Working Group endorsed the publication of escalation protocols on the NIAA’s intranet (see paragraphs 3.49 to 3.52). The new protocols portrayed the escalation approach differently to that outlined in the ICFF, including roles and workflow.

Recommendation no.3

2.44 The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensure that:

- advisory committee activities are in line with approved terms of reference; and

- the National Indigenous Australians Agency Audit and Risk Committee’s annual report to the accountable authority clearly highlights known deficiencies in the risk management and control framework.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

2.45 In February 2023, as part of the Agency’s commitment to ongoing improvement, the Executive Board approved a new committee governance structure. To give effect to this decision, the Agency is revising the terms of reference for all committees to provide greater clarity on the purpose and role of each committee. Additionally, a requirement for a review of the operations of Executive Board and its sub-committees (at least annually) is being implemented.

2.46 The Audit and Risk Committee provides independent advice to the Agency’s accountable authority on the appropriateness of its system of risk oversight and management. The Committee is not responsible for the executive management of these functions.

2.47 The annual reports provided by the Audit and Risk Committee during the audit period have highlighted deficiencies and supplemented information provided to the CEO at post-Audit and Risk Committee meetings and in regular reports to the Executive Board. The recommendation to clearly highlight these is noted and the CEO will continue to meet regularly with the Chair, and with all members as required, to ensure the CEO receives an independent perspective on audit and risk matters.

Assurance

2.48 Auditor-General Report No. 11 2020–21, Indigenous Advancement Strategy – Children and Schooling Program and Safety and Wellbeing Program, noted that the NIAA was in the process of reconsidering the role of the grant assurance function. A suggestion for improvement was that, as part of the reconsideration of the Grant Assurance Office’s role, adequate mechanisms were developed to support the effectiveness of the quality assurance framework, including ensuring that opportunities for improvement were acted upon. In February 2022 the NIAA released a Grant Assurance Framework. The Grant Assurance Framework summarised principles for control, assurance and continuous improvement mechanisms for grants administration.

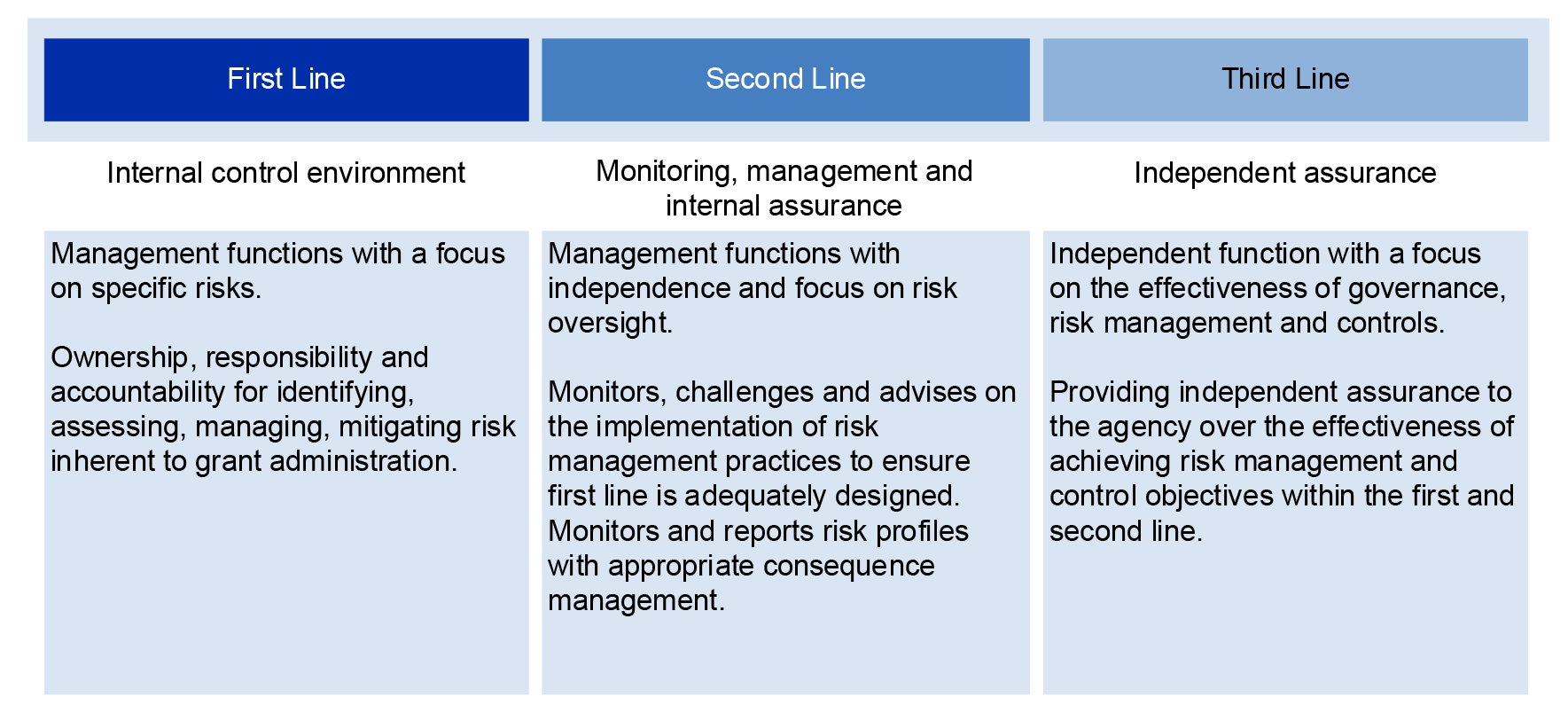

2.49 The Grant Assurance Framework uses the three lines of defence model21 to describe different types of assurance that are applicable to the NIAA. The three lines of defence model adopted by the NIAA is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Assurance levels outlined in the Grant Assurance Framework

Source: ANAO analysis of the Grant Assurance Framework (February 2022).

First line assurance activities

2.50 The first line of defence is the internal control environment and includes regular management functions that implement and monitor controls, including policies, procedures, and delegations of authority. These activities are intended to ensure that risks are identified and addressed, performance is monitored, and objectives are achieved by line management.

2.51 Within the NIAA, three portfolios (the Policy and Programs Portfolio, the Operations and Delivery Portfolio and the Corporate Portfolio) have responsibility for delivery of programs. Each of these portfolios has specific responsibilities for the management of provider fraud and non-compliance risks and activities.

- Policy and Programs Portfolio — Four groups design and program manage a range of IAS-funded programs and sub-programs. They are responsible for preparing program and fraud risk assessments.

- Operations and Delivery Portfolio — The Program Performance Delivery group within this portfolio consists of about 200 staff who undertake grant administration activities and are responsible for the development, maintenance and implementation of grants management processes and policies. The group comprises three branches including the Grant Design Branch and the Grants Management Unit. The Grant Design Branch includes the Grant Assurance Office whose role is to develop and implement an internal quality control and assurance framework that addresses the key steps in the grants administration lifecycle.

- Corporate Portfolio — The Program Compliance and Fraud Branch within this portfolio consists of about 25 staff whose role is to undertake compliance and fraud action and assist, advise and train staff in compliance management to strengthen the capacity of providers. The Branch has operational responsibility for fraud risk management, prevention and control.22

Second line assurance activities

Community Development Program Assurance

2.52 The Grant Design Branch established a Community Development Program (CDP) Performance and Assurance Framework in June 2020. The purpose of the framework is to set out the NIAA’s approach to CDP performance monitoring and supporting provider compliance. The framework outlines how the Grant Design Branch will undertake assurance reviews and monitoring of compliance. The framework included a 2022 test schedule and the number of claims to be tested. The framework states that any suspected fraudulent activity identified through the assurance processes must be referred to the Program Compliance and Fraud Branch.

2.53 The outcomes of the CDP assurance and compliance monitoring activities are reported to the Policy and Delivery Committee through several reports. Performance and assurance reporting to the Policy and Delivery Committee includes the overall results for each provider (including validity testing), trend analysis in relation to previous performance assessment, recommended remedial action for underperforming providers and activity compliance trends or issues as observed through site visits. Although the assurance reporting identifies compliance trends over time for individual providers and proposes solutions to some operational problems, it does not provide insights into the overall operational effectiveness of the CDP or identify systemic or emerging issues, which the Performance and Assurance Framework stated the CDP assurance activity was designed to do.

Grant Assurance Office

2.54 The second line of defence assurance activities include those performed by the Grant Assurance Office. The Grant Assurance Framework defines the role of the Grant Assurance Office as reporting on the effectiveness of internal controls across the grant lifecycle and conducting assurance reviews.23 In 2021–22 resourcing for the Grant Assurance Office was increased from one part-time position to 1.6 full-time equivalent positions.

2.55 There was no 2020–21 or 2021–22 forward work plan for the Grant Assurance Office. The Grant Assurance Office performed reviews and activities which were directed by the CEO or requested by the broader NIAA executive. In November 2022 a paper was provided to the Program Performance Committee with a draft Grants Assurance Office Forward Work Plan 2023. Nine potential topics for consideration were identified. In March 2023 the Forward Work Plan was approved by the Group Manager, Program Performance Delivery.

2.56 The outcomes of the work performed by the Grant Assurance Office in 2020–21 and 2021–22 were reported to the Program Performance Committee, covering 12 assurance activities during this period. Ten of the reports were presented to the Program Performance Committee within twelve months of the period under review. For two Grant Assurance Office reviews, this reporting occurred long after the work had been undertaken. For example, a March 2022 report covered activities from July 2020 to December 2020. The reports identified opportunities to improve the quality and consistency of grant processes, although action owners and implementation dates were sometimes lacking. Updates are also provided to the ARC upon request, with high-level findings, review suggestions and actions taken to date.

Management-initiated reviews

2.57 A range of management-initiated reviews have been commissioned by the NIAA. Of these, three 2021 reviews relate to provider fraud and non-compliance (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Management-initiated reviews relevant to provider fraud and non-compliance

|

Review |

Relevance to provider fraud and non-compliance |

Purpose and outcomes |

|

Grants Management Process Review (June 2021) undertaken in conjunction with Projects Assured |

The Grants Management Process Review addressed roles and responsibilities of grant administration staff, including the escalation of potential issues. |

The purpose of the review was to collate the insights from NIAA staff to inform the Program Performance Delivery ‘Grant Management Action Plan’. The review identifies 150 actions across three areas:

|

|

Post Implementation Review of the Grants Management Unit (June 2021) undertaken in conjunction with Projects Assured |

The Grants Management Unit was set up to perform grants management tasks in the ‘establish’ and ‘manage’ phases of the grants management lifecycle. This includes engagement with providers and assessment of associated risks. |

The purpose of the review was to provide a health check on the implementation of the Grants Management Unit established in December 2019. The review developed an action plan for the next twelve months to mature the Grants Management Unit. This included activities such as:

|

|

Grant Risk Management Review (June 2021) undertaken in conjunction with Yardstick Advisory |

The Grant Risk Management Review assessed the application and use of the Grant Risk Management Guidelines. These guidelines are used to assess provider and grant activity risks. The review considered the development of organisational risk profiles and activity risk assessments. |

The purpose of the review was to assess the Grant Risk Management Guidelines and related processes for alignment with the revised NIAA Risk Management Policy and Framework (December 2020). The review identified a road map for implementation that had 32 recommendations, including to:

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Policy Delivery Committee papers and minutes.

2.58 The three reviews were discussed by Policy and Delivery Committee in July 2021, where it was agreed to engage across the NIAA on the recommendations and implementation. In October 2021 the Group Manager, Program Performance Delivery presented a paper to the Executive Board which stated that the NIAA had considered the recommendations of the three reviews, identified priorities and determined to incorporate the recommendations into the work of an existing ‘Grants Business Transformation Project’ in 2021–22. The priorities included strengthening the grants risk management framework in two phases (with the second phase to consider the NIAA’s approach to program, sub-program and activity risk) and introducing a mandatory grants design process to inform grant opportunity planning.

2.59 Although the Policy and Delivery Committee has received regular updates on the progress of the Grants Business Transformation Project, there is no evidence that the Policy and Delivery Committee has held Program Performance Delivery accountable for timely delivery of the reforms. For example, the Grant Risk Management Guidelines were not updated to reflect the December 2020 changes to the NIAA’s Risk Management Framework until September 2022.

2.60 In an update on grants management provided to the ARC in November 2022, the NIAA indicated that grant risk assessments had been updated to reflect the changes to the December 2020 risk matrix contained in the Risk Management Policy.

Third line assurance activities

2.61 A three-year rolling internal audit work plan is prepared. The ARC tracks and reviews the outcomes of internal audit activities, including management responses to internal and external audit findings and recommendations. The Internal Audit Work Program 2022–23 includes eight audits to be undertaken during the year. Although a review of grants management and assurance is planned, none of the planned internal audits directly focuses on provider fraud and non-compliance risks.24

2.62 Several relevant reviews were undertaken in 2021 (see Table 2.3) and in June 2021 KPMG Australia delivered an ‘IAS Program Health Check’. The purpose of this report was to assist the NIAA to prepare for this ANAO audit. The review considered the effectiveness of the NIAA’s arrangements to control the risk of IAS grant recipient fraud and non-compliance and found that ‘improvement was required’. Four ‘moderate’ risk-rated recommendations were identified related to the following areas: governance, roles and responsibilities; risk-based management of grants; policies and procedures; and accessibility and retention of data. By June 2022, all recommendations had been endorsed to be closed by the Audit and Risk Committee. Closure was recommended by the Head of Internal Audit based on advice from management. The ANAO has identified ongoing deficiencies in each of these areas.

3. Prevention, detection and referral

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the National Indigenous Australians Agency’s (NIAA) arrangements for preventing, detecting and referring potential provider fraud and non-compliance are effective.

Conclusion

The NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention, detection and referral of potential provider fraud and non-compliance are partly effective. Prevention is not consistently or sufficiently considered in grant design and planning, and training is out of date. Detection relies primarily on complaints being raised and arrangements to deal with complaints are appropriate. Proactive detection controls are not sufficiently implemented. Referral and escalation arrangements exist, however these require greater clarity.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations to the NIAA aimed at ensuring that program fraud risk assessments, organisational risk profiles, and activity risk assessments are fully implemented; and at the NIAA implementing proactive fraud detection mechanisms. The ANAO also suggested that the NIAA improve its training on compliance and fraud; and make policies and procedures consistent with the compliance and fraud management framework.

3.1 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) subsection 10(c) includes the requirement to have an appropriate mechanism for preventing fraud. Prevention activities include designing grant opportunities to minimise the potential for fraud and promoting a fraud-aware culture.

3.2 PGPA Rule subsection 10(d) includes the requirement to have an appropriate mechanism for detecting incidents of fraud or suspected fraud, including a process for officials of the entity and other persons to report suspected fraud confidentially. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy also includes mandatory requirements related to establishing procedures to collect, manage and report information about fraud against the entity. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy encourages compliance with AS 8001:2021 Fraud and corruption control, which mandates that detection activities should encompass; post transactional review, review of management reports, identification of early warning signs/red flags, data analytics, whistle blower management systems, complaints management, grant acquittals and grant finalisation processes.25

Are the NIAA’s arrangements for the prevention of provider fraud and non-compliance effective?

Provider fraud and non-compliance risks are not consistently or sufficiently considered as part of grant design and establishment processes. A new grant design strategy requirement was introduced in March 2022 which incorporates risk assessment, including the consideration of fraud risks. At February 2023 there were eight new, revised or extended grant opportunities. Of these one had a finalised risk assessment that considered fraud risks. Key documentation given to providers offers information about the Australian Government’s and NIAA’s position on fraud. Provider risks are assessed in the grant establishment process through provider and activity risk profiles and these cover fraud risk to some extent. There are weaknesses in how this is used to understand aggregated risks at the sub-program level. The Program Compliance and Fraud Branch has not provided adequate monitoring, review or reporting on fraud risk assessments. Relevant mandatory and non-mandatory training is offered, however the training is out of date.

3.3 To determine if the NIAA’s approach to the prevention of provider fraud and non-compliance risks was effective, the ANAO considered business planning and grant planning arrangements; and whether training programs had been appropriately developed and monitored.

Business planning