Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

National Ice Action Strategy Rollout

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In April 2015 the Australian Government established a National Ice Taskforce (the Taskforce) to report on actions needed to address crystal methamphetamine use in Australia. The Taskforce recommended actions aimed at reducing demand, supply, and the harms associated with crystal methamphetamine use.1

2. The National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) was endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in December 2015 with the goal of:

Reducing the prevalence of ice use and resulting harms across the Australian community.2

3. The NIAS identified five action areas, as follows:

- support for families and communities;

- targeted prevention;

- investment in treatment and workforce;

- focused law enforcement; and

- better research and data.3

4. All governments are responsible for the implementation and monitoring of the NIAS. The NIAS included that a Ministerial Drug and Alcohol Forum (MDAF) would be formed to oversee the development, implementation and monitoring of Australia’s national drug policy framework, including the NIAS, from 2016. The forum was to consist of health and justice Ministers with responsibility for alcohol and drug policy and law enforcement, and report directly to COAG.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. This audit was undertaken to provide assurance that a key strategy to reduce the prevalence of crystal methamphetamine use and resulting harms across the Australian community is being implemented effectively and that progress on the delivery of the actions presented in the NIAS is transparent. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, in 2016, 50,000 people self-reported using crystal methamphetamine at least once a week.4 The Australian Government budgeted NIAS funding for actions that the Department of Health has responsibility for implementing is $451.5 million over six years (from 2016–17 to 2021–22). Through consultation with the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, this audit topic was identified as an Audit Priority of the Parliament in 2018.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s implementation of the NIAS.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- planning and governance arrangements established to support implementation of the NIAS were appropriate;

- delivery of NIAS actions was effective; and

- progress is transparent.

Conclusion

8. The Department of Health’s (the department) implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy is partially effective. While Australian Government funding to the alcohol and other drug sector has been increased and actions have been progressed, there is no monitoring to assess whether progress is being made towards the Strategy’s goal of reducing the prevalence of ice use and resulting harms across the Australian community.

9. The department has established appropriate governance arrangements to support implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy, but did not plan for implementation effectively. Performance and accountability measures were not developed, and implementation and risk plans were not used.

10. The department’s delivery of actions contained in the National Ice Action Strategy is largely effective. The department has delivered, or is in the process of delivering, the 19 actions it has responsibility for and Australian Government funding for the alcohol and other drug sector has increased. Although the department monitors the activities of Primary Health Networks, it has not finalised a quality and assurance framework that would allow it to assess that Primary Heath Networks are effectively commissioning, monitoring and evaluating alcohol and other drug services.

11. The department does not have an evaluation approach in place for the National Ice Action Strategy, and is not monitoring progress towards the goal and objective. Public reporting by the department does not currently provide sufficient transparency about how implementation is progressing or what progress is being made towards the goal and objective.

Supporting findings

Planning and Governance

12. Roles and responsibilities for implementing, monitoring and reporting on the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) have been clearly assigned and formalised with all relevant parties. The department supported the establishment of the Ministerial Drug and Alcohol Forum (MDAF) and the National Drug Steering Committee to oversee Australia’s national drug policy framework. The department has briefed the MDAF on progress towards implementing the 19 actions it has responsibility for. The MDAF has not met since June 2018 and has not yet provided its 2018 annual report to COAG.

13. The department’s planning for the implementation of the NIAS was not effective. The department drafted, but did not use or update, an implementation plan and risk register aside from monitoring progress of the actions it has responsibility for implementing. An approach to measuring performance was not established. Actions recommended by the department’s program assurance team to ensure performance and accountability measures are in place have not been progressed by the program area. These actions include developing a risk management plan, a logic model, a stakeholder engagement framework and a change management plan.

Delivery of National Ice Action Strategy actions

14. The department’s implementation planning to expand alcohol and other drug treatment services through the Primary Health Networks (PHNs) was partially effective. The department developed processes and guidance to assist the PHNs to undertake the commissioning process but the department’s timeframes for PHNs to undertake strategic planning proved to be unrealistic. The department’s framework for assessing the quality of the PHN planning documentation is also incomplete. All 31 PHNs were commissioning services by December 2017, 12 months later than the department initially anticipated.

15. The department does not yet have appropriate mechanisms in place to verify the information it collects from PHN reporting or assess PHN performance management.

16. Out of the 19 NIAS actions for which the department is responsible, three are being delivered through the PHNs. The first action, to increase investment in the alcohol and other drug sector, has been delivered through the Australian Government’s investment of around $59 million per year. While the department does not have a clear way of demonstrating the delivery of the remaining two actions, relating to increasing linkages between providers and enhancing early intervention and post-treatment care, evidence suggests they are being progressed.

17. The department has delivered nine of the remaining 16 NIAS actions, and is progressing the remaining seven actions, either through contracts with external providers or through the NIAS governance arrangements. The department has monitored delivery through reporting arrangements as specified in relevant contracts. The delay in establishing the National Centre for Clinical Excellence has resulted in revised timeframes for the Centre to deliver its agenda. Planned enhancements to national treatment data are either on hold, or may be implemented in time for the 2020–21 collection year on a best endeavours (rather than mandated) basis. Of the $13 million allocated for new Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items for Addiction Medicine Specialists, as at 31 March 2019, only $3.1 million (24 per cent) has been paid in MBS benefits.

Monitoring progress and transparency

18. The department did not develop an evaluation framework as required by the Australian Government. Out of the 19 actions for which the department has responsibility, two actions have evaluation frameworks in place, another two actions have been evaluated, and one action is scheduled to be evaluated from July 2019. However, there is no overarching evaluation framework or evaluation plan in place, and baseline performance information from which to assess what is being achieved by delivering the actions through the NIAS has not been defined.

19. The department does not monitor progress toward the goal and objective of the NIAS. While the NIAS does not contain outcomes, performance indicators, or a performance framework that would facilitate monitoring progress towards the goal and objective, the department did not address this gap. Data capable of measuring progress towards the NIAS goal and objective is collected and publicly reported by a range of entities. The department has not developed an approach to draw this data together in a manner that would allow for progress toward the goal and objective to be monitored.

20. Public reporting on the implementation of the NIAS has not been adequate for transparency and accountability purposes, as the two annual progress reports provided by the MDAF to COAG for 2016 and 2017 have not been made public. The intended inclusion and publication of NIAS progress reports within the National Drug Strategy annual progress reports will increase transparency regarding the progress of individual NIAS actions, if information in the report is adequate. Public reporting by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare on alcohol and other drug treatment services cannot separately identify services funded under the NIAS.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.30

That the Department of Health ensures performance, risk and accountability measures are in place to support implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.24

That the Department of Health finalise the Primary Health Network Quality and Assurance Framework, with appropriate actions to assess whether PHNs are operating appropriately across the commissioning cycle.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.11

That the Department of Health develop an evaluation framework for the National Ice Action Strategy, including the identification of suitable baseline performance information from which progress can be measured.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.26

That the Department of Health monitor progress towards the goal and objective of the National Ice Action Strategy and provide this information to government.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.42

That the Department of Health improve public reporting on how the implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy is progressing and what is being achieved.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

Australian Government initiatives and funding supporting the National Ice Action Strategy has led to increased availability of alcohol and drug treatment services across Australia which help to overcome dependence and reduce harm.

The report found the administrative planning of the health-led actions was not effective. However, the appropriate level of planning was undertaken to ensure services were implemented in a timely manner. There was multi-jurisdictional consultation and engagement with Primary Health Networks to ensure local needs assessments were carried out. The report also indicated effective delivery of the actions the Department of Health (department) was responsible for.

While the department acknowledges initial planning processes could have been improved, there is some evidence the department’s roll out of activities—including providing funding for alcohol and other drug treatment services through Primary Health Networks—is contributing to reducing the harms associated with crystal methamphetamine. While direct attribution for reductions of national prevalence under the NIAS is not valid, the department is encouraged by recent data showing a decrease in the national rates of use of reported consumption of methamphetamines (from 2.1% to 1.4% between 2013 and 2016), including ice (1.0% to 0.8% over the same period). The department will continue to monitor trends in drug use, including the work undertaken by Australia’s alcohol and other drug research sector and state and territory governments.

The department is successfully progressing the 19 National Ice Action Strategy actions for which it has primary or shared responsibility, on schedule, and is continuing to work collaboratively with states and territories to ensure shared NIAS actions and objectives are realised.

More is being done to work with the Primary Health Networks—responsible for managing over 500 alcohol and drug treatment services across Australia—in adjusting our strategic approach to reducing the harms crystal methamphetamine and other illicit drugs are causing to individuals, families and communities.

The department is continuing to implement and monitor these treatment services, as well as other related activities through the broader Drug and Alcohol Program of the Australian Government. The department—with the Department of Home Affairs—is also working closely with the states and territories through the National Drug Strategy Committee to continue oversight and collaboration on areas of shared responsibility and focus. This work includes the development of a robust National Drug Strategy Reporting Framework, which will include reporting of progress against the objectives in the National Ice Action Strategy.

The department is fully committed to adopting better practices in governance arrangements, management and program evaluation, and has already taken steps to address issues identified in this audit. In 2018, the department took action to improve its internal capability to oversee the Primary Health Network Program, including establishing the risk management plan, refining the program performance and quality framework, and establishing projects to strengthen implementation.

The effective implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy is underpinned by a recognition of the need for national collaboration across jurisdictions and across agencies in reducing the harms associated with ice use across Australia. The report has focused on health-related actions exclusively and has attributed sole ownership for all health actions to the department. While this is true for a number of individual actions, the responsibility for planning, delivery and implementation of the majority of actions is shared between the Commonwealth and states and territories as reflected in the joint governance arrangements and reporting. An overarching evaluation of the National Ice Action Strategy, developed in collaboration with the states and territories for the consideration of the Council of Australian Government’s, will assess the effectiveness of the rollout of the National Ice Action Strategy.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) endorsed a National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) in December 2015 with the goal of:

Reducing the prevalence of ice use and resulting harms across the Australian community. 5

Crystal methamphetamine use in Australia

1.2 Amphetamine is a drug that stimulates the central nervous system. Terminology for amphetamine and methamphetamine (a type of amphetamine) varies across data sources (Figure 1.1). Crystal methamphetamine6 is the strongest and most addictive form of methamphetamine, and this report uses the term crystal methamphetamine rather than the colloquial term ‘ice’, unless directly quoting evidence where the term ‘ice’ has been used.

Figure 1.1: Relevant terminology

Note: IDDR: Illicit Drug Data Report published by the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. AODTS NMDS: Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set collected by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; NDSHS: National Drug Strategy Household Survey published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Source: Adapted from Box 4.5.4 ‘Terminology for methamphetamine’ in Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s Health 2016, AIHW, 2016, p. 158.

1.3 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) collects data every three years from around 24,000 people mostly aged 14 years and over. The 2016 survey shows recent7 self-reported meth/amphetamine use declined from 3.4 per cent in 2001 to 1.4 per cent in 2016. Between 2013 and 2016 recent self-reported meth/amphetamine use significantly declined from 2.1 per cent of the population to 1.4 per cent, and recent self-reported crystal methamphetamine use slightly declined from 1.0 per cent to 0.8 per cent. The main form of meth/amphetamine used has changed over time, with crystal increasing from 21.7 per cent in 2010 to 57.3 per cent in 2016.

1.4 The NDSHS asks respondents about their perception and attitudes towards illicit drugs. The proportion of the population who thought methamphetamine was the drug of most serious concern for the general community increased from 16.1 per cent in 2013 to 39.8 per cent in 2016.8

1.5 The National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP)9 provides information about estimated drug use by measuring the concentrations of drug metabolites10 in wastewater samples. Methamphetamine is consistently the highest estimated illicit substance consumed of those illicit substances measured.11 Between year one (2016–17) and year two (2017–18) of the NWDMP12, the estimated weight of methamphetamine consumed increased by 17.2 per cent.

1.6 The number of national amphetamine-type stimulants seizures consecutively increased from 2010–11 to 2015–16, then decreased between 2015–16 and 2016–17, though the total weight of seizures for 2016–17 was the third highest on record (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: National amphetamine-type stimulants seizures by number and weight, 2007–08 to 2016–17

Source: Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Illicit Drug Data Report 2016–17, ACIC, 2018.

1.7 Following five years of consecutive increases, the number of arrests for amphetamine-type substances remained relatively stable between 2015–16 and 2016–17 (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3: Number of arrests for amphetamine-type stimulants 2007–08 to 2016–17

Source: Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Illicit Drug Data Report 2016–17, ACIC, 2018.

Development of the National Ice Action Strategy

1.8 In April 2015 the Australian Government established a National Ice Taskforce (the Taskforce) to report on actions needed to address increasing crystal methamphetamine use in Australia. The Taskforce found that while law enforcement agencies have responded strongly to disrupt the supply of crystal methamphetamine, the market remains strong and resilient. The Taskforce recommended shaping a response that will reduce the demand for crystal methamphetamine, provide treatment and support services that cater to the needs of crystal methamphetamine users, take steps to prevent people from using drugs, and for efforts to disrupt supply to be coordinated and targeted. The Taskforce presented its final report to the Australian Government in October 2015 with 38 recommendations intended to make an impact on crystal methamphetamine use.13

1.9 The NIAS was endorsed by COAG in December 2015. The NIAS contained 30 actions grouped in five action areas, and was supported by Australian Government funding of $313.2 million over four years from 2016–17 as follows14:

- $24.9 million to empower local communities and give more support for families;

- targeted prevention and education to those most at risk15;

- further investment in treatment and workforce support, consisting of:

- $241.5 million for the delivery of further treatment services; and

- $13 million to introduce new Medicare Benefits Schedule items;

- $15 million for focused law enforcement; and

- $18.8 million for better research, evidence and guidelines.

1.10 The Department of Health (the department) is the lead Australian Government entity responsible for delivering 19 of the 30 actions, totalling $298.2 million over four years from 2016–17. The remaining 11 actions focused on law enforcement (totalling $15 million over four years) are the responsibility of the Home Affairs Portfolio and are outside the scope of this audit.

1.11 In the 2019–20 Budget the Australian Government included an additional $153.3 million to extend the health related actions in the NIAS. This brought total budgeted NIAS funding for actions that the department has responsibility for implementing to $451.5 million over six years (from 2016–17 to 2021–22).

1.12 The Australian Government’s funding aims to expand the alcohol and other drug treatment sector so people who need drug and alcohol services can access them, rather than providing targeted treatment services to those only using crystal methamphetamine. In 2016, approximately 90 per cent of people who reported recent16 meth/amphetamine use also reported recent use of one or more additional illicit drug (Figure 1.4).17

Figure 1.4: Proportion of people reporting recent meth/amphetamine use who reported recent use of another drug, aged 14 years or older, 2016 (per cent)

Note: Recent use is use in the previous twelve months. Excludes those using meth/amphetamine for medical purposes. Lifetime risky drinking means drinking on average more than two standard drinks a day. Single occasion risky drinking means more than four standard drinks on one occasion at least once a month.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings, AIHW, 2017; Table 2.2.

Australia’s National Drug Strategy

1.13 Australia’s National Drug Strategy (NDS) provides the national framework to identify national priorities and guide government action in partnership with service providers and the community. Since the first iteration in 1985, the NDS has been underpinned by a harm minimisation objective. The seventh iteration of the NDS is the first to have a ten year lifespan (2017–2026), previous iterations covered a period of five years. The NIAS is now a sub-strategy of the NDS 2017–2026 (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5: National Drug Strategy and sub-strategies

Source: Department of Health, National Drug Strategy 2017–2026, DOH, 2017.

1.14 In addition to the NDS and NIAS, each State and Territory government has alcohol and other drug strategies, plans and inquiries, including those specifically targeting methamphetamine, and/or crystal methamphetamine use.

Alcohol and other drug treatment service funding

1.15 There is no overarching agreement clarifying roles and responsibilities for alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment service funding and provision between the Australian and State and Territory governments.

1.16 Treatment services for AOD use are broadly divided into generalist and specialist services, usually on the basis of the setting. Generalist services are provided through primary care and hospitals, while AOD treatment agencies provide specialist services such as withdrawal management, psychosocial therapies (counselling), rehabilitation and pharmacotherapy in residential and non-residential settings. An estimate of the Australian and State and Territory government contributions to AOD treatment services has not been updated since 2014.18 The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC) at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) estimated on the basis of 2012–13 data that the State and Territory governments contributed approximately 80 per cent of all government funding for specialist AOD treatment services, with the Australian Government contributing the remaining 20 per cent.19 Specialist AOD treatment services can also be provided by not-for-profit organisations and private providers who do not receive government funding.20

1.17 In 2017–18, there were 952 government funded AOD treatment agencies who provided treatment services to an estimated 130,000 clients.21 The most common principal drug of concern (the primary drug leading someone to seek treatment) was alcohol (34 per cent), followed by amphetamines (25 per cent).22

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 This audit was undertaken to provide assurance that a key strategy to reduce the prevalence of crystal methamphetamine use and resulting harms across the Australian community is being implemented effectively and that progress on the delivery of the actions presented in the NIAS is transparent. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, in 2016, 50,000 people self-reported using crystal methamphetamine at least once a week.23 The Australian Government budgeted NIAS funding for actions that the Department of Health has responsibility for implementing is $451.5 million over six years (from 2016–17 to 2021–22).Through consultation with the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, this audit topic was identified as an Audit Priority of the Parliament in 2018.

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s implementation of the NIAS.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- planning and governance arrangements established to support implementation of the NIAS were appropriate;

- delivery of NIAS actions was effective; and

- progress is transparent.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit methodology included:

- examining and analysing documentation relating to planning, governance, delivery, monitoring and reporting of the 19 NIAS actions that the department is responsible for;

- analysis of publicly available data, including data reported by the AIHW; the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission; the Australian Institute of Criminology; the NDARC at UNSW; and the Australian Bureau of Statistics;

- interviews with key departmental officials involved in the implementation of NIAS actions; and

- meetings with key stakeholders including AOD peak organisations; research bodies; and PHNs.

1.22 This audit included the 19 NIAS actions that the department were responsible for implementing. The NDS and sub-strategies beyond the NIAS are out of scope for this audit, as are the various state and territory government drug and/or ice action plans, strategies and reforms.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of about $469,000. The team members for this audit were Ailsa McPherson, Tracy Cussen, Christine Preston, Michael Fitzgerald, Hannah Climas and David Brunoro.

2. Planning and governance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the planning and governance arrangements established by the Department of Health (the department) to support implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) were appropriate.

Conclusion

The department has established appropriate governance arrangements to support implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy, but did not plan for implementation effectively. Performance and accountability measures were not developed, and implementation and risk plans were not used.

Recommendation

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at ensuring the department has performance and accountability measures in place to support implementation of the NIAS.

2.1 Examining the appropriateness of arrangements to support implementation of the NIAS included reviewing:

- roles and responsibilities, including the establishment of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed Ministerial Forum and intergovernmental steering committee; and

- the departmental arrangements regarding implementation planning, risk assessment and program assurance.

Were roles and responsibilities for implementation, monitoring and reporting of the NIAS clearly assigned and formalised with all relevant parties?

Roles and responsibilities for implementing, monitoring and reporting on the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) have been clearly assigned and formalised with all relevant parties. The department supported the establishment of the Ministerial Drug and Alcohol Forum (MDAF) and the National Drug Steering Committee to oversee Australia’s national drug policy framework. The department has briefed the MDAF on progress towards implementing the 19 actions it has responsibility for. The MDAF has not met since June 2018 and has not yet provided its 2018 annual report to COAG.

Establishment of governance arrangements

2.2 In 2015 the National Ice Taskforce (the Taskforce) examined alcohol and other drug governance arrangements between the Australian and State and Territory governments in accordance with its terms of reference. The Taskforce reported24:

The existing system of governance does not facilitate timely collaboration between Commonwealth, state and territory governments to implement effective responses to drug-related issues. The current structure under COAG requires the Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs to obtain endorsement of its work through numerous other intergovernmental committees. This can often undermine timely and coordinated policy-making on illicit drugs.

2.3 The Taskforce also noted that, in addition to the Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs reporting to multiple intergovernmental committees25, there were two separate COAG Ministerial Councils with responsibility for alcohol and other drug policy. Responsibility was shared, with law enforcement aspects situated with the COAG Law, Crime and Community Safety Council; and health aspects situated with the COAG Health Council.26

2.4 Recommendation 32 of the Taskforce’s final report stated27:

The Commonwealth, state and territory governments should introduce a simplified governance model to support greater cohesion and coordination of law enforcement, health, education and other responses to drug misuse in Australia, with a direct line of authority to relevant Ministers responsible for contributing to a national approach.

2.5 The NIAS included governance arrangements for alcohol and other drug policy. A Ministerial Drug and Alcohol Forum (MDAF) was to be formed to oversee the development, implementation and monitoring of Australia’s national drug policy framework, including the NIAS. Membership of the MDAF would consist of health and justice ministers and report directly to COAG. The Australian Government Ministers for Health and Justice co-chair the MDAF, with each state and territory having two ministerial members, one health and one justice or law enforcement. The first meeting of the MDAF was held in December 2016.

2.6 The MDAF’s terms of reference state its role is to:

- oversee the development and implementation of the National Drug Strategy (NDS), including monitoring progress against priority areas;

- oversee development and implementation of NDS sub-strategies (including the National Tobacco Strategy, National Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Peoples Drug Strategy, National Alcohol and other Drug Workforce Development Strategy, and the National Ice Action Strategy);

- provide direction, advice and reports to other councils and committees, as required; and

- provide an annual report to COAG.

2.7 The MDAF provides relevant information to the COAG Health Council and the COAG Council of Attorneys-General.28 A National Drug Strategy Committee (NDSC) supports the MDAF.29 The NDSC’s membership comprises deputy secretary level officials from the state and territory health and justice portfolios. The NDSC is co-chaired by the department’s deputy secretary with responsibility for alcohol and other drug policy and the relevant deputy secretary from the Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. The NDSC links with the Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council (which reports to the COAG Health Council) and the National Justice and Policing Senior Officials Group (which reports to the COAG Council of Attorneys-General) (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Governance arrangements for Australia’s national drug policy framework

Source: Department of Health, National Drug Strategy 2017–2026, DOH, 2017 and Attorney-General’s Department, Law, Crime and Community Safety Council [Internet], AGD, 2019, available from https://www.ag.gov.au/About/CommitteesandCouncils/Law-Crime-and-Community-Safety-Council [accessed 23 April 2019].

2.8 The first meeting of the NDSC was held in November 2016 (Table 2.1).30

Table 2.1: The NDSC and MDAF meeting details

|

Meeting number |

NDSC meeting date |

NIAS relevant items |

MDAF meeting date |

NIAS relevant items |

|

1 |

30/11/2016 |

Draft 2016 NIAS progress report prepared and submitted to MDAF [out-of-session]. Initial discussion of national quality framework progression with working group to progress. Work to begin early in 2017 on a reporting framework for the NDS. |

16/12/2016 |

Draft 2016 NIAS progress report presented, with submission to COAG [out-of-session]. |

|

2 |

20/04/2017 |

Draft NDS (2017–2026) agreed [out-of-session] with submission to MDAF. NIAS becomes a sub-strategy of the NDS. Draft NIAS Reporting Framework for progress reports agreed [out-of-session]. |

29/05/2017 |

NDS (2017–2026) agreed. |

|

3 |

01/11/2017 |

Draft 2017 NIAS progress report approved and sent to MDAF. |

27/11/2017 |

2017 NIAS progress report agreed for submission to COAG. National quality framework agreed in-principal with the NDSC working group to consult and finalise. |

|

4 |

01/05/2018 |

Updates given for NIAS actions for research and data, AOD hotline, national treatment framework and for the proposed formation of the NDS reporting framework working group. |

14/06/2018 |

Noted progress of the national treatment framework and approved ongoing progress to develop the national quality framework. |

|

5 |

08/02/2019 |

Discussion of progress for the NDS reporting framework, national treatment framework and national quality frameworks. Completion of all three frameworks expected by end June 2019. |

8/02/2019 (postponed) |

Update provided on work undertaken by jurisdictions. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.9 The department has supported the Australian Government Minister for Health and the department’s deputy secretary in their roles of co-chairs of the MDAF and NDSC.

2.10 Decisions taken by the MDAF are made on the basis of consensus where possible, otherwise they are based on a member majority with one vote per jurisdiction.

2.11 The most recent meeting of the MDAF was held in June 2018, with the meeting scheduled for February 2019 postponed.

National Drug Strategy Committee Working Groups

2.12 The NIAS includes two actions that require inter-jurisdictional cooperation; the development of a national treatment framework and a national quality framework. The NDSC has established specialist, time-limited working groups to progress these two items, along with a research and data working group, and a group to develop a framework for NDS reporting (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: National Drug Strategy Committee working groups

|

Name of working group |

National Quality Framework |

National Treatment Framework |

AOD Research and Data |

Reporting Framework |

|

Date of first meeting |

18/12/2017 |

23/01/2018 |

18/12/2018 |

16/01/2019 |

|

Responsibility |

Develop a framework providing a nationally consistent approach and align accreditation systems across jurisdictions. |

Manage the development of the National Treatment Framework for submission to the department in June 2019. |

Explore research and data issues including complex data requests and projects that cut across organisations and jurisdictions. |

Develop a framework for the NDS annual report, including reporting for sub-strategies. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

Reporting to COAG

2.13 The NIAS specifies that the MDAF will report directly to COAG on implementation, lessons learned and next steps. The MDAF terms of reference require an annual report be submitted to COAG on Australia’s national drug policy frameworks including the implementation of each area of the NIAS. The 2016 and 2017 annual reports submitted to COAG by the MDAF met these requirements. These reports are not required to be, and have not been, made public.

2.14 The MDAF has noted the intention to change reporting to COAG on the NIAS implementation.31 Reporting on NIAS implementation is now intended to be included in the NDS annual progress report through the following approach32:

- the NDSC will coordinate an annual progress report for the MDAF providing an update on jurisdictional and national activity, and identifying trends and emerging issues based on the best available data;

- a more detailed progress report prepared by the NDSC for MDAF approval and submission to COAG in line with the release of the findings from the NDSHS in 2018, 2021, 2024 and a final report in 2027; and

- the NDSC will undertake a mid-review of the NDS in 2021–2022 to provide an opportunity to identify any new priorities, emerging issues or challenges.

2.15 The 2016 and 2017 annual reports to COAG from MDAF on NIAS implementation were submitted in December 2016 and December 2017. The 2018 NDS annual report33, now intended to include the NIAS progress report, is due to be endorsed by the NDSC in August 2019 for submission to MDAF. Following endorsement by MDAF, this report will be provided to COAG. While the 2016 and 2017 reports from MDAF to COAG on NIAS implementation have not been made public, the NDS annual reports will be published on the department’s website.

2.16 In addition to reporting to COAG, the MDAF communiques are published on the department’s website, providing a high-level overview of major items discussed by Ministers during the meeting.34

2.17 Under the 2018 MDAF Terms of Reference, the MDAF must provide COAG with a ‘robust evaluation’ of the implementation of NIAS by June 2020. To date, no action has been taken by MDAF or the NDSC to prepare for, or undertake, an evaluation. The department’s approach to evaluation of the NIAS is discussed further in Chapter 4.

Did the department plan effectively for the implementation of the NIAS, including risk assessment and management?

The department’s planning for the implementation of the NIAS was not effective. The department drafted, but did not use or update, an implementation plan and risk register aside from monitoring progress of the actions it has responsibility for implementing. An approach to measuring performance was not established. Actions recommended by the department’s program assurance team to ensure performance and accountability measures are in place have not been progressed by the program area. These actions include developing a risk management plan, a logic model, a stakeholder engagement framework and a change management plan.

Implementation planning

2.18 The department is responsible for implementing 19 of the 30 NIAS actions. An implementation plan was drafted by the department in April 2016 encompassing the 19 actions the department is responsible for implementing.35 The plan allocated actions to a departmental officer to progress; identified a start date; detailed the budget allocation where applicable; and referenced the relevant policy document source for each action (the Taskforce report; the Australian Government response to the Taskforce report; and/or the NIAS).

2.19 The implementation plan did not identify or define key milestones, and did not present an approach to measure performance. Since April 2016, the program area has not engaged with or maintained this implementation plan aside from monitoring progress of the actions it has responsibility for implementing (annual progress reports on the implementation of NIAS actions were provided to COAG by MDAF for 2016 and 2017, see paragraph 2.13). The department advised the ANAO that it did not update the implementation plan as it was focused on delivering the actions.

Risk management

2.20 The department’s risk management policy36:

- defines the department’s approach to the management of risk;

- sets out the key accountabilities and responsibilities for managing and implementing the department’s risk management framework; and

- defines the department’s risk appetite and risk tolerance.

2.21 The policy takes a tiered approach to risk management. The department’s deputy secretaries hold responsibility for enterprise level (including strategic) risks; the department’s first assistant secretaries are responsible for business risks; and assistant secretaries/program managers are responsible for operational risks. The policy requires those who are responsible for managing risks ensure risk registers are current, controls and treatments are in place, and risks are actively managed.

2.22 In April 2016 the program area responsible for implementing the 19 NIAS actions prepared a risk register that included four risks:

- potential delays to key approvals;

- other project lead agencies do not deliver their projects in the required timeframes;

- stakeholders receive mixed messages through the various project leads; and

- suitable departmental resources to deliver projects are not available.

2.23 Mitigation strategies detailed in the risk register included: prioritising projects for implementation; developing a project management governance model; and developing a stakeholder management plan. The program area did not implement these mitigation strategies, and the risk register was not updated or engaged with further.

2.24 The management of performance and risk for the Primary Health Network (PHN) program is discussed in Chapter 3.

Program assurance

2.25 In January 2018 the department implemented new internal governance arrangements and established a Program Assurance Committee (PAC) to:

- drive excellence in program delivery, through risk and evaluation frameworks; and

- monitor and review implementation, delivery and performance of programs.

2.26 The department is responsible for 28 programs aligned to the six outcomes presented in the department’s Portfolio Budget Statements.37 A program assurance team was established as part of the new internal governance arrangements to support the department’s program areas, with the PAC providing a strategic overview and assurance to the Secretary and Executive Board.

2.27 The inaugural PAC meeting held in March 2018 established a program assurance framework and the terms of reference. The intention was for all 28 programs to complete a program report, including a self-assessment against the six program assurance standards contained in the framework38, and present to the PAC by the end of 2018. The PAC agreed that programs may be split into different elements for PAC reporting purposes.

2.28 The program area with responsibility for implementing the NDS and sub-strategies, including the NIAS, under program 2.4 ‘Preventive Health and Chronic Disease’39 completed a maturity assessment against the program assurance standards. After reviewing the program area’s self-assessment against the standards, the program assurance team noted actions40 that the program area would need to complete to meet the standards.

Risk Management — A program level risk management plan and register is required to reduce the risk of significant issues eventuating and preventing the delivery of the program’s outcomes. In addition regular review of risks should be done by the program team including, documenting emerging risks and ensuring the treatments are still adequate.

Logic Model — Creation of a logic model would help to link the various individual programs, highlight relationships between the many stakeholders and outline the internal capabilities required to deliver the program. This activity would assist in the development of risk management and stakeholder engagement plans.

Governance Structure/Roles and Responsibilities — Governance and oversight arrangements are fit for purpose and documented in the strategy documents, however roles and responsibilities are not clearly documented. For example, the senior responsible officer and role and responsibilities would ideally be written into the terms of reference of committees or program descriptions.

Stakeholder Engagement — Establish a stakeholder engagement framework and document regular and scheduled meetings of internal and external parties, networks and organisations. This would offer further structure to existing mechanisms and provide greater opportunity for collaboration across partnering agencies and stakeholder groups.

Change Management Plan — The program has advised that a change management strategy will be considered during the branch planning process. This should be reflective of the logic model, risk and stakeholder management plans as described above.

2.29 These actions, as outlined in the program report to the PAC, were scheduled to be discussed at the November 2018 PAC meeting. The department advised that, while the PAC did not convene,41 the report and actions were accepted by the program area responsible for the NDS and NIAS. At the time of the audit the program area with responsibility for the NDS and NIAS had not yet progressed the actions identified by the program assurance team.

Recommendation no.1

2.30 That the Department of Health ensures performance, risk and accountability measures are in place to support implementation of the National Ice Action Strategy.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.31 The department is developing performance, risk and accountability measures to support continued implementation and monitoring of its components of the National Ice Action Strategy. This includes the development of an evaluation framework and mid-point review to assess the contribution health-led initiatives have made towards the goals and objectives of the National Ice Action Strategy. The department will develop an overarching evaluation of the National Ice Action Strategy, in conjunction with the Department of Home Affairs and states and territories by 30 June 2020, for Council of Australian Government’s consideration.

3. Delivery of National Ice Action Strategy actions

Areas examined

This chapter considers the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s (the department) delivery of 19 actions in the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) it has responsibility for, to provide assurance that delivery of these actions is on track.

Conclusion

The department’s delivery of actions contained in the NIAS is largely effective. The department has delivered, or is in the process of delivering, the 19 actions it has responsibility for and Australian Government funding for the alcohol and other drug sector has increased. Although the department monitors the activities of Primary Health Networks (PHNs), it has not finalised a quality and assurance framework that would allow it to assess that PHNs are effectively commissioning, monitoring and evaluating alcohol and other drug services.

Recommendation

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at prioritising the development of an appropriate PHN quality and assurance framework.

3.1 The Department of Health (the department) is responsible for delivering 19 of the 30 actions presented in the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) under four priorities: ‘families and communities’; ‘prevention’; ‘treatment and workforce’; and ‘research and data’.42 Three of the actions under the ‘treatment and the workforce’ priority are being delivered through the expansion of the alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment sector through Primary Health Networks (PHNs). This chapter focuses on these three actions as they represent the largest financial commitment by the Australian Government under the NIAS. The remaining 16 actions the department is responsible for delivering are briefly discussed at the end of the chapter.

Expansion of alcohol and other drug treatment services through Primary Health Networks

3.2 Approximately 80 per cent of NIAS funding allocated to the department ($241.5 million over four years from 2016–17) was to deliver further AOD treatment services commissioned by the PHNs (see Table 3.1). This represented a new funding and service delivery approach for AOD treatment services.

Table 3.1: Alcohol and other drug funding to PHNs — NIAS

|

|

2016–17 $m |

2017–18 $m |

2018–19 $m |

2019–20 $m |

Total $m |

|

Allocation |

59.0 |

59.9 |

60.8 |

61.8 |

241.5a |

Note a: Of the total $241.5 million allocation over four years, $78.6 million was to support delivery of services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.3 The 31 PHNs were established by the Australian Government on 1 July 2015 to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of primary health care services across Australia. PHNs are independent, not-for-profit, regionally based planning and commissioning organisations. The PHN Program commenced twelve months prior to the commencement of the NIAS funding.43 PHNs are funded to deliver two objectives:

- increase the efficiency and effectiveness of medical services for patients, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes; and

- improve the coordination of care to ensure patients receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time.

3.4 Departmental documentation describes the PHN Program as ‘a model of devolved, networked government’:

At the national level, the Department of Health has responsibility for identifying and addressing national health priorities and systemic health systems issues, making available data and resources, and implementing the strategic vision for reform of the Australian health system. However, key responsibilities and decision making in regard to planning, prioritising, funding and monitoring health services at the regional level have been devolved to PHNs.

3.5 The PHN Program has received $4.4 billion in Australian Government funding over four years from 2016–17, with the NIAS funding of $241.5 million representing 5.5 per cent of total PHN Program funding.

3.6 The Australian Government has identified seven priority areas for PHN activity: mental health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, population health, digital health, health workforce, aged care, and alcohol and other drugs. The ‘alcohol and other drugs’ priority area was included in ‘population health’ until 2018 after which it was given separate priority status. The department advised that the status was changed in recognition of the Government’s financial investment in the AOD sector, and that commissioning AOD treatment services is a key component of PHNs’ work programs.

3.7 The role of the PHNs is to make decisions about which services or health care interventions should be provided and who should provide them, based on their strategic planning activities. PHNs enter into and manage contracts with service providers, and are responsible for monitoring and evaluating the quality of commissioned services.

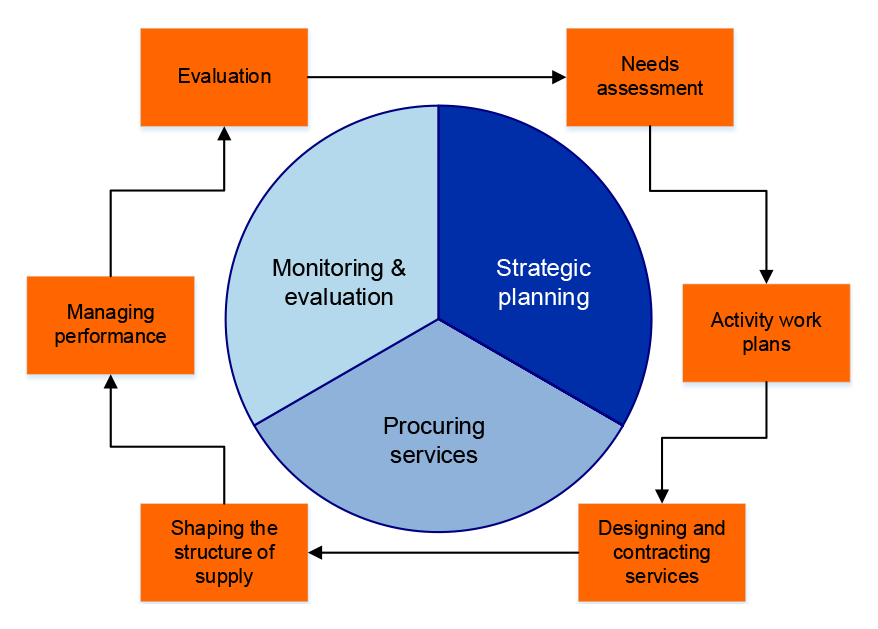

3.8 PHNs are responsible for the key stages of the commissioning cycle: strategic planning, procuring services, and monitoring and evaluation (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: PHN responsibilities

Source: Departmental documentation.

3.9 The department manages the funding agreements with PHNs and supports PHNs to deliver four deliverables (needs assessments44, activity work plans45, and two performance reports [at six and 12 months]), reviewing their content and assessing PHN performance to inform future funding negotiations. The department’s responsibilities for the PHN Program are as follows:

- policy and plans — national policies (primary health care, alcohol and other drugs); national plans (including the National Drug Strategy); PHN Program guidelines;

- performance — PHN performance framework, performance management and national indicators;

- resources — allocation of funding to PHNs, data and reports; and

- program management — national support function, relationship building, stakeholder engagement (including national peak bodies and jurisdictions).

Did the department undertake effective implementation planning to expand treatment services through the PHNs?

The department’s implementation planning to expand alcohol and other drug treatment services through the Primary Health Networks (PHNs) was partially effective. The department developed processes and guidance to assist the PHNs to undertake the commissioning process but the department’s timeframes for PHNs to undertake strategic planning proved to be unrealistic. The department’s framework for assessing the quality of the PHN planning documentation is also incomplete. All 31 PHNs were commissioning services by December 2017, 12 months later than the department initially anticipated.

The department does not yet have appropriate mechanisms in place to verify the information it collects from PHN reporting or assess PHN performance management.

3.10 In January 2016 the department started a series of tasks to deliver the three actions aimed at expanding AOD treatment services through the PHNs, including developing: a) a model to allocate NIAS funding across PHNs; b) an AOD Annexure to the PHN Program guidelines to inform PHNs about the activities within scope to receive NIAS funding; and c) a suite of supplementary guidance material to assist PHNs to undertake strategic planning.

3.11 The department expected PHN commissioning would begin from 1 July 2016. To become ‘commissioning-ready’ the department required PHNs to undertake the strategic planning stage of the commissioning cycle by completing a needs assessment and developing an activity work plan46 prior to procuring services. Funding was provided to PHNs from February 2016 to commence these planning activities and, under their funding agreements, PHNs could not start procuring services using the NIAS funding until their planning documents were approved by the department.

3.12 While the department provided templates and other supporting materials to assist PHNs to complete their planning documents it set short timeframes (see Appendix 2) that did not appear to sufficiently account for the fact that PHNs had not previously commissioned services47 or operated across the AOD sector.48

3.13 Overall a majority of the initial planning documents submitted by PHNs were required to be re-submitted following review by the department.49 This led to delays to the start of the procurement phase of the commissioning cycle. PHNs reported to the department that the time needed for contract negotiation with service providers, along with difficulties finding a service provider who had suitably trained and available staff, contributed to further delays. Service procurement on the basis of strategic planning undertaken during 2016 was not complete (with all agreed activities in operation) across all PHNs until December 2017.

3.14 The department monitored the timeliness of service procurement by PHNs with NIAS funding. Weekly reporting (from the PHN to the department and the department to the department’s executive staff and Minister’s office) was undertaken from December 2016 until September 2017 to track when contracts were in place and when service activities had commenced. In addition, a policy was written and put in place to manage unspent funds.

3.15 In addition to the planning templates and guidance material provided to PHNs, the department set out specific requirements relevant for commissioning of AOD treatment services in an annexure to the Primary Health Network Grant Programme Guidelines (Annexure A2 — Drug and Alcohol Treatment Services). This annexure states that PHNs were to:

develop evidence-based regional drug and alcohol treatment plans50, based on needs assessment (in consultation with relevant stakeholders), and service mapping designed to identify gaps and opportunities for optimal use of services to reduce duplication and promote efficiencies.51

3.16 The department assessed whether the planning templates had been completed in full. In addition, the department checked whether the planning documents indicated that PHNs had: analysed relevant data; consulted with stakeholders; considered opportunities for collaboration; and reviewed the alcohol and drug treatment service provision within local areas. However, the department did not require additional supporting documentation from the PHNs, for example service mapping or evidence of robust consultation with relevant stakeholders. Therefore, the department cannot verify the accuracy of information provided by PHNs.

3.17 In addition, the department did not establish a set of standards to use in assessing the quality of PHN planning documents against the expectations set out in the annexure to the Primary Health Network Grant Programme Guidelines. Therefore, the department cannot provide assurance that planned activities identified by PHNs met the expectations set out in the annexure.

3.18 In 2018 the department took action to improve its internal capability to oversee the PHN Program including by developing a PHN Risk Management Plan, refining the PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework and commencing six projects, overseen by a Program Board52, to strengthen program implementation.

3.19 Of the six priority projects overseen by the Program Board, two are relevant to the PHN’s procurement of AOD services with NIAS funding — the PHN Program Manual (the Manual) and PHN Quality Management and Assurance Framework (the Framework). Both projects are scheduled to be completed in September 2019, though the department’s internal tracking indicates their status as ‘insufficient progress with risk’. The department advised the ANAO in June 2018 that additional resources have been put to these projects to ensure they are delivered.

3.20 The Manual is intended to be a single source of information on program operations for use by PHNs and across the department. The Manual could further clarify the compliance, monitoring and assurance efforts within the department and by the PHNs across the commissioning cycle to provide a rationale for actions to be included in the proposed Framework.

3.21 The aim of the Framework is to provide greater assurance that the department is undertaking appropriate activities to ensure PHNs are operating appropriately and complying with their legal and financial obligations. The Framework is to include activities currently underway to ensure compliance management and continuous quality improvement across the PHN Program. The project plan indicates that the Framework will include consideration of the appropriate use of an audit program.

3.22 In the absence of this Framework, the department does not have an overall picture of the quality and completeness of the tools it is using to assure that PHNs are commissioning, monitoring and evaluating AOD services appropriately.

3.23 As the PHN Program is a devolved model of service delivery with clear distinctions in the roles and responsibilities of the department (funder and performance manager) and the PHNs (service planning, procuring, monitoring and evaluating services), the department should have taken early action to embed its role as performance manager by establishing appropriate oversight and assurance mechanisms.

Recommendation no.2

3.24 That the Department of Health finalise the Primary Health Network Quality and Assurance Framework, with appropriate actions to assess whether PHNs are operating appropriately across the commissioning cycle.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

3.25 The department is developing a PHN Program Assurance Framework endorsed by the PHN Program Board. The framework will provide greater assurance for the Commonwealth regarding all activities the department undertakes to ensure PHNs are operating appropriately and in accordance with their legal and financial obligations. A rolling program of PHN audits based on risk criteria, scheduled to begin in 2019-20, will provide greater assurance as to the quality of the reporting and data received and internal governance arrangements in place within the PHN.

Have the three NIAS actions delivered through PHNs been delivered?

Out of the 19 NIAS actions for which the department is responsible, three are being delivered through the PHNs. The first action, to increase investment in the alcohol and other drug sector, has been delivered through the Australian Government’s investment of around $59 million per year. While the department does not have a clear way of demonstrating the delivery of the remaining two actions, relating to increasing linkages between providers and enhancing early intervention and post-treatment care, evidence suggests they are being progressed.

3.26 By providing $241.5 million over four years from 2016–17 to PHNs to commission AOD services, the department is delivering three of the NIAS actions under the NIAS ‘treatment and workforce’ priority (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: NIAS actions being delivered through the Primary Health Networks

|

National Ice Action Strategy actions |

Status |

|

Increase investment in the alcohol and other drug sector, including for Indigenous-specific drug and alcohol services. |

Delivered. Government approved an increased investment of $59 million per year over four years from 2016–17, bringing the total annual departmental funding to the sector to around $133 million per year. |

|

Increase the links that exist between Primary Health Networks and health care providers and community services to improve continuity of care. |

Progressed. A self-reported indicator against this action is included in the performance reporting requirements for PHNs. The department has not finalised an assurance mechanism to test performance. |

|

Enhance the delivery of early intervention and post-treatment care through Primary Health Networks. |

Progressed. The department has not developed a metric for this action and there is no baseline data on the number of services providing these types of treatment prior to NIAS funding. The department collects data from PHNs on the number of services currently providing these treatment types. |

Source: National Ice Action Strategy 2015 and ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

Investment in the alcohol and other drug sector

3.27 In April 2016 the Minister for Health approved distribution of the $59 million in annual NIAS funding53 to expand the AOD sector through PHNs to be distributed as follows:

- $15.5 million ‘floor funding’ allocated equally to each of the 31 PHNs ($500,000 annually for each PHN) to enable them to undertake their new role in expanding AOD treatment services54;

- $21.9 million in mainstream funding55 allocated to PHNs according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2011 census data weighted for rurality, socioeconomic disadvantage and the Indigenous status of the PHN’s population;

- $18.3 million for Indigenous-specific AOD services allocated to PHNs on the basis of the Indigenous status of the PHN’s population calculated on the basis of the ABS 2013 estimated resident population; and

- $3.3 million for operational funding to provide additional support calculated at 0.2 average staffing level per 250,000 population to each PHN.

3.28 Prior to the introduction of NIAS funding in 2016–17, the department provided direct funding of almost $75 million per year to 148 organisations to deliver AOD treatment services through a competitive grants process. The department reviewed these funding arrangements during 2016–17, and from 1 July 2017 implemented the following changes:

- funding for direct treatment activities was transferred to PHNs (around $40 million per year);

- funding for national organisations and national activities was retained by the department (around $29 million per year);

- funding for capacity building was redirected to direct treatment and transferred to the PHNs (around $4.5 million per year); and

- funding was continued to the jurisdictional peak organisations to provide capacity building and sector support (around $2 million per year).

3.29 In December 2018 the Minister for Health approved up to $79.5 million in annual funding for three years from 2019–20 to continue these funding arrangements.

Increase the links that exist between Primary Health Networks and health care providers and community services to improve continuity of care

3.30 A new PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework came into effect from 1 July 201856, with the PHN’s first 12-month reports for assessment under the revised framework to be submitted by end September 2019. The framework provides a structure for monitoring and assessing PHN’s individual performance and progress towards outcomes under all Funding Schedules of the PHN Program.

3.31 The department has identified two outcomes out of the framework’s five outcome themes57 that are AOD specific, the first is improving access and the second is coordinated care. The framework also contains an aspirational longer-term outcome for the AOD priority area (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3: Performance and quality indicators (AOD specific)

|

Outcome theme |

Description of outcome theme |

Outcome |

Indicator |

|

Improving Access |

Activities by PHNs to improve access to primary health care by patients. |

People in PHN region are able to access appropriate drug and alcohol treatment services. |

AOD 1: Rate of drug and alcohol commissioned providers actively delivering services. |

|

Coordinated Care |

Activities and support by PHNs to improve coordination of care for patients and integration of health services in their region. |

Health care providers in PHN region have an integrated approach to drug and alcohol treatment services. |

AOD 2: Partnerships established with local key stakeholders for drug and alcohol treatment services. |

|

Longer Term |

N/A |

Decrease in harm to population in PHN region from drug and alcohol misuse. |

To be developed: indicators on impact of services on health outcomes for patients. |

Source: Department of Health, PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework, Australian Government Department of Health, Canberra, 2018.

3.32 The current six-monthly PHN reporting template includes a free text field for PHNs to identify ‘partnerships established with local key stakeholders for drug and alcohol treatment services’. The content provided by the PHNs is variable but generally provides a list of organisations with whom PHNs have had contact. The department has not established criteria to assess the quality of the information provided and there is no reference to this indicator in the PHN Six Month Report Guide to define what is expected.

Enhance the delivery of early intervention and post-treatment care through Primary Health Networks

3.33 The department has not developed an indicator or measure to assess whether early intervention and post-treatment care have been enhanced through PHNs.

3.34 Baseline data on the number of services delivering early intervention and post-treatment care prior to NIAS funding is not available as these treatment types are not captured under reporting through the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Dataset (see paragraph 4.41).

3.35 The department collects basic information directly from PHNs regarding the services they are procuring with NIAS funding from service providers, including whether the service is an Indigenous-specific service, the service type and the commencement date of service delivery.

3.36 Annexure A2 — Drug and Alcohol Treatment Services of the Primary Health Network Grant Programme Guidelines identifies treatment and support (non-treatment) eligible for NIAS funding should align with one or more of seven service types (Table 3.4). Both early intervention and post-treatment care are included.

Table 3.4: Treatment and support eligible for NIAS funding

|

Category |

Service type |

|

Direct treatment |

Early intervention targeting less problematic drug use, including brief intervention |

|

Counselling |

|

|

Withdrawal management with pathways to post-acute withdrawal support and relapse prevention |

|

|

Residential rehabilitation with pathways to post rehabilitation support and relapse prevention |

|

|

Day stay rehabilitation and other intensive non-residential programmes; post rehabilitation support and relapse prevention |

|

|

Case management; care planning and coordination |

|

|

Non-treatment |

Supporting the workforce undertaking these service types through activities that promote joined up assessment processes and referral pathways and support continuous quality improvement, evidence-based treatment and service integration/coordination |

Source: Department of Health, Annexure A2 Drug and Alcohol Treatment Services — Primary Health Network Grant Programme Guidelines, Department of Health, 2016.

3.37 On the basis of the information collected by the department 507 service providers58 have been contracted over the last three financial years, to March 2019, by PHNs to provide treatment and support. Of the 507 providers: 339 (67 per cent) provide mainstream services; 163 (32 per cent) provide Indigenous-specific services; and five were not specified.

3.38 The main category of treatment service provided is identified as ‘counselling’ (39 per cent); followed by ‘early intervention’ (18 per cent); ‘case management’ (16 per cent); and ‘workforce development’ (nine per cent). The remaining contracts have a main category of ‘withdrawal management’ (seven per cent); residential rehabilitation (four per cent); ‘post rehabilitation support’ (three per cent); and ‘day stay rehabilitation’ (three per cent) (Table 3.5).

3.39 PHNs may identify up to three categories delivered by each contracted provider. This data indicates that of the 507 services: 160 listed ‘early intervention’ or ‘brief intervention’ as a main, secondary or additional treatment type; and 88 identified ‘post rehabilitation support’.

Table 3.5: PHN contracted providers by main service type as at March 2019

|

Service type |

Funding |

Providers commissioned |

||

|

|

$ million |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

Early intervention, including brief intervention |

27.6 |

17.8 |

86 |

17.0 |

|

Counselling |

60.5 |

39.1 |

108 |

21.3 |

|

Withdrawal management |

11.0 |

7.1 |

30 |

5.9 |

|

Residential rehabilitation |

5.7 |

3.7 |

16 |

3.2 |

|

Day stay rehabilitation |

4.1 |

2.6 |

10 |

2.0 |

|

Post rehabilitation support and relapse prevention |

4.2 |

2.7 |

18 |

3.6 |

|

Case management, care planning and coordination |

25.4 |

16.4 |

63 |

12.4 |

|

Othera |

1.2 |

0.8 |

5 |

1.0 |

|

Subtotal (Treatment) |

139.7 |

90.1 |

336 |

66.3 |

|

Workforce development/capacity building |

14.5 |

9.4 |

166 |

32.7 |

|

Othera |

0.7 |

0.5 |

5 |

1.0 |

|

Subtotal (Support) |

15.2 |

9.8 |

171 |

33.7 |

|

Total |

155.0 |

100.0 |

507 |

100.0 |

Note a: ‘Other’ includes five after-hours support services (included in ‘treatment subtotal’), four online/telehealth; one evaluation; and three unspecified activities (included in ‘support’ subtotal).

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental data.

Has the department delivered the NIAS actions under the families and communities; prevention; treatment and workforce; and research and data priorities?

The department has delivered nine of the remaining 16 NIAS actions, and is progressing the remaining seven actions, either through contracts with external providers or through the NIAS governance arrangements. The department has monitored delivery through reporting arrangements as specified in relevant contracts. The delay in establishing the National Centre for Clinical Excellence has resulted in revised timeframes for the Centre to deliver its agenda. Planned enhancements to national treatment data are either on hold, or may be implemented in time for the 2020–21 collection year on a ‘best endeavours’ (rather than mandated) basis. Of the $13 million allocated for new Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items for Addiction Medicine Specialists, as at 31 March 2019, only $3.1 million (24 per cent) has been paid in MBS benefits.

3.40 In addition to implementing three actions under the ‘treatment and workforce’ priority area through the PHN Program as detailed above, the department is implementing 16 further actions under the four priority areas ‘families and communities’, ‘prevention’, ‘treatment and workforce’ and ‘research and data’.

The department’s implementation approach

3.41 The 16 actions reviewed in this section are primarily being implemented through contracting arrangements between the department and external providers selected through tendering processes. The department monitored implementation through the reporting arrangements as specified in the contract. In accordance with contractual requirements, external providers have submitted periodic progress reports, and the department has reviewed and actioned these reports to ensure implementation progresses as intended.

3.42 Prior to endorsement of the NIAS, the department managed a range of AOD initiatives under the auspice of the NDS 2010–2015. Of the 16 actions contained in the NIAS that the department was responsible for implementing, seven built on existing initiatives managed by the department. The remaining nine actions were new initiatives (Table 3.6).

Table 3.6: Status of the 16 NIAS actions (new or existing)

|

Status of NIAS action |

Number of actions |

|

Built on existing initiative with no additional NIAS funding |

4 |

|

Expanded an existing initiative with additional NIAS funding |

3 |

|

New initiative without NIAS funding |

4 |

|

New initiative with NIAS funding |

5 |

|

Total |

16 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.43 The remainder of this section examines the progress towards implementing 16 actions under the four priority areas ‘families and communities’; ‘prevention’; ‘treatment; and the workforce’; and ‘research and data’. To maintain focus on high materiality actions, the nine actions that received Australian Government funding are examined in more detail.

Families and Communities

3.44 The three actions under the families and communities priority aim to meet community need for access to information and resources about alcohol and other drugs (Table 3.7).

Table 3.7: NIAS actions under the families and communities priority

|

Action |

New, existing or expanded initiative |

NIAS Funding (if applicable) |

Status |

|

Establish up to 220 new Local Drug Action Teams across Australia. The teams will bring together community groups to reduce drug related harms at a local level. |

New |

$19.2 million |

Delivered. 244 Local Drug Action Teams are in place as at March 2019. |

|

Launch the ‘Positive Choices’ web portal to deliver up-to-date, accessible, and relevant information on ice to community organisations, parents, teachers and students. |

Expanded |

$1.1 million |

Delivered. The web portal was launched in December 2015 and NIAS funded expansion activities are complete. |

|

Establish a national phone line that will serve as a single point of contact for individuals and families seeking to receive information, counselling and other support services for dealing with ice use and other drugs. |

Existing |

N/A |

Delivered. The national phone line became operational in July 2017. |

Source: National Ice Action Strategy 2015 and ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.45 The Alcohol and Drug Foundation (ADF) is receiving $19.2 million in funding over four years from 1 July 2016 until 30 June 2020 to establish and implement the Local Drug Action Teams (LDATs) program. The goal of the LDATs is for communities to work together to deliver evidence-informed activities that prevent and minimise the harm caused by alcohol and other drugs. Each LDAT reports to the ADF on a six monthly basis. The ADF provides six monthly progress reports to the department, along with an annual activity work plan.