Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Multi-Role Helicopter Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the Department of Defence’s progress in delivering Multi-Role Helicopters (MRH90 aircraft) to the ADF through AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 and 6, within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters.

Summary

Introduction

1. At a budgeted cost of $4.013 billion, the Multi‑Role Helicopter (MRH90) Program is to acquire 47 helicopters and their support system for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The program involves the acquisition of a single helicopter type to meet multiple capability requirements, and it is being implemented as part of Defence’s AIR 9000 Program. The capability requirements include: troop lift helicopter operations from Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ships; utility helicopter operations to enable the Australian Army to respond swiftly and effectively to any credible armed lodgement on Australian territory; and more likely types of operations in Australia’s immediate neighbourhood. In pursuing the acquisition, the then Australian Government recognised that ADF helicopters would be instrumental in the planned expansion of the ADF’s amphibious deployment and sustainment capability.1

2. The multi‑role helicopter acquisition was also a key component of Defence’s 2002 ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan.2 The overall aim of the Master Plan was to achieve acquisition and sustainment cost efficiencies by reducing the number of helicopter types in ADF service, and by increasing Australian industry capability to assemble and sustain the ADF’s helicopter fleet within Defence Capability Plan price and schedule limits.3 A core feature of the Master Plan was to form a partnership with a Prime Contractor to implement the AIR 9000 Program through a Strategic Partner Program Agreement. This Strategic Agreement was to complement long‑term sole‑source helicopter acquisition and sustainment contracts, through the sharing of goals, risks and communication strategies, and by providing for cost visibility and audit access.

3. The AIR 9000 Program consists of eight phases. This audit considers the following four phases:

- Phase 1 produced the ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan;

- Phase 2 is to acquire a squadron of 12 MRH90 aircraft to provide the ADF with extra mobility for forces on operations, particularly amphibious operations. This phase received government Second Pass approval4 in August 2004; and

- Phase 4 and Phase 6 are to acquire 28 MRH90 aircraft to replace Army’s S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk aircraft, and six MRH90 aircraft to replace the retired RAN Sea King aircraft.5 These phases received simultaneous Second Pass approval in April 2006.

4. In May 2013, Defence agreed to an offer of an additional MRH90 aircraft, the 47th, as part of a negotiated settlement and release of commercial, technical and schedule issues with the MRH90 Prime Contractor. Figure S.1 shows an MRH90 aircraft in a standard configuration.

Figure S.1: Multi‑Role Helicopter (MRH90)

Source: Department of Defence.

5. During the audit, the MRH90 Program was dealing with a range of challenges related to immaturity in the MRH90 system design and the support system. The challenges include:

- resolving MRH90 cabin and role equipment design issues so that operational test and evaluation validates the MRH90 aircraft’s ability to satisfy Operational Capability Milestones set by Army and Navy;

- the continuing need to conduct a wide range of verification and validation activities on problematic or deficient aircraft systems;

- increasing the reliability, maintainability and flying rate of effort of the MRH90 aircraft;

- embedding revised sustainment arrangements directed toward improving the value for money of these arrangements;

- establishing a revised Australian industry activities plan, including performance metrics;

- funding and managing the extended concurrent operation of the Army S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk and MRH90 aircraft fleets; and

- managing a Navy capability gap following the retirement of the RAN Sea King aircraft in December 2011.

Source selection and contractual arrangements

6. In May 2003, the Department of Defence (Defence) released a Request for Proposal(RFP) for AIR 9000 Phase 2 to three prospective suppliers. In response to the RFP, AgustaWestland offered the EH101 Merlin, Australian Aerospace Limited offered the NH90 (to be developed for Australia as the MRH90) and Sikorsky Aircraft Australia Limited offered the S‑70M Black Hawk.6 Following evaluation of the bids, the AgustaWestland EH101 offer was set aside and Defence pursued an Offer Development and Refinement Process (ODRP) for a combined Phases 2 and 4 with the two remaining bidders. This led to a Defence recommendation to the Minister for Defence in June 2004 that the S‑70M Black Hawk be selected as the preferred aircraft for Phases 2 and 4.

7. In accordance with direction provided by the Minister for Defence and government, Defence developed alternate draft submissions, initially to ask ministers to choose between the two aircraft options—the MRH90 and S‑70M Black Hawk—and later recommending acquisition of the MRH90 for Phase 2 only. In August 2004, government formally approved the acquisition of 12 MRH90 aircraft for Phase 2 on the basis that strategic and other government considerations outweighed the cost advantage of the Sikorsky proposal.

8. In June 2005, following protracted contract negotiations, Defence signed an acquisition contract with Australian Aerospace for the supply of 12 MRH90 aircraft and for an interim support system. The interim support system did not include important MRH90 aircraft support elements such as an electronic warfare self protection support cell, a ground mission management system, a software support centre, an instrumented aircraft with telemetry, and Full Flight and Mission Simulators. These support elements are critical for providing training and the ability to operate off ships. They were removed from the MRH90 acquisition contract to ensure AIR 9000 Phase 2 remained within its approved budget, and were added to the contract through later amendments, and at additional cost.7 In July 2005, Defence signed an MRH90 sustainment contract and a Strategic Partner Program Agreement with Australian Aerospace.

9. In November 2005, the Defence Capability Investment Committee (DCIC) agreed to seek a combined First and Second Pass approval for both Phase 4 and 6.8 Defence developed two acquisition business cases: one for an MRH90 option and another for an S‑70M Black Hawk option. An April 2006 Defence submission recommended the acquisition of the MRH90 to replace the Army S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk and Navy Sea King aircraft, on the basis that it was a better capability, and that the rationalisation of the utility helicopter fleet would generate lower through‑life costs. Following formal government approval of the MRH90 option, the original acquisition contract with Australian Aerospace9 was amended in June 2006 to include the additional 34 MRH90 aircraft and their support system. This brought to 46 the number of MRH90 aircraft to be acquired, with a 47th aircraft added in May 2013.

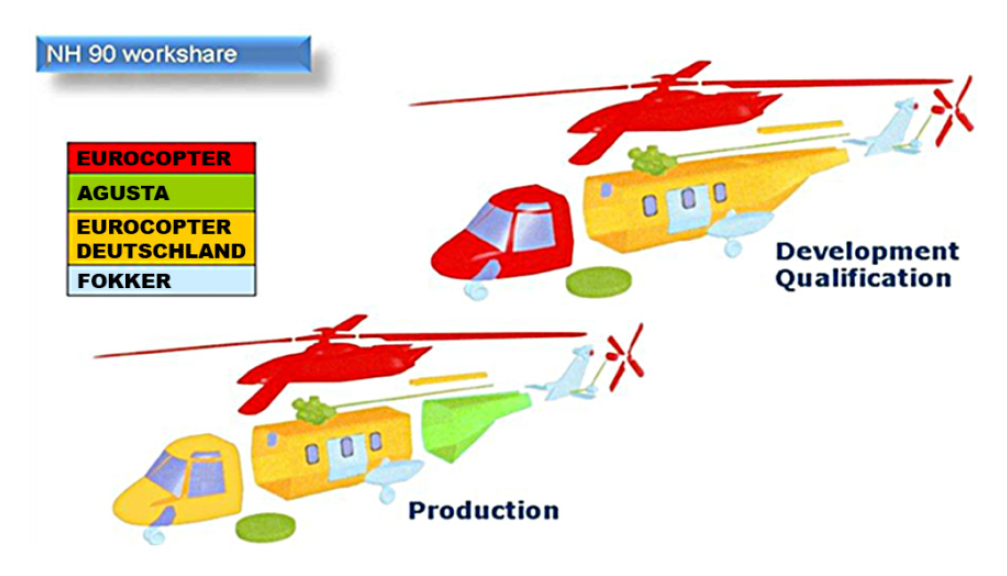

10. The 47 Australian MRH90 aircraft are a variant of the NATO Helicopter Industries (NHI) NH90 Troop Transport Helicopter (TTH). NHI was established in 1992 to develop and produce the NH90, and is a partnership between Eurocopter (France), Eurocopter Deutschland (Germany), AgustaWestland (Italy) and Stork Fokker Aerospace (Netherlands). NHI is the MRH90 aircraft’s Original Equipment Manufacturer, and Australian Aerospace, a Eurocopter10 subsidiary, is the Prime Contractor for the MRH90 Program, for both the acquisition and sustainment of the ADF’s MRH90 fleet. The MRH90 aircraft are assembled in Brisbane by Australian Aerospace, utilising assemblies supplied by Eurocopter. Figure S.2 shows the workshare arrangement used to develop and produce the NH90.

Figure S.2: NH90 development and production workshare

Source: Department of Defence.

Capability management arrangements

11. The Chief of Army is the lead Capability Manager for all of the ADF’s MRH90 fleet. The Chief of Navy has capability management responsibilities for the six MRH90 aircraft assigned to Navy. These officers are responsible for overseeing and coordinating all elements necessary to achieve the MRH90 aircraft’s full level of operational capability by the date agreed to by government.

12. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) MRH90 Program Office is located in Canberra and is responsible for the acquisition of the MRH90 aircraft and their transition into service. The DMO’s MRH90 Logistics Management Unit is located in Brisbane, and at the time of the audit was merging with the Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter (ARH) Logistics Management Unit to form the Reconnaissance and Mobility Systems Program Office (RAMSPO).11

13. Australian Aerospace is the Authorised Engineering Organisation (AEO) for sustainment of the MRH90 aircraft, and has overall Systems Program Office (SPO) responsibility for a range of services normally undertaken by a DMO SPO. Australian Aerospace is the Approved Maintenance Organisation (AMO) for MRH90 Operational Maintenance at the Army Aviation Training Centre in Oakey, Queensland, and for MRH90 Retrofit and Deeper Maintenance at its MRH90 assembly facility in Brisbane. Two other maintenance organisations have been formally accredited by the Director General Technical Airworthiness (DGTA) as AMOs for the MRH90 aircraft: Army’s 5th Aviation Regiment in Townsville; and Navy’s 808 Squadron in Nowra.

14. Army and Navy operational units provide overall MRH90 fleet management in terms of flying operations and safety management, fleet‑usage coordination and management of aircraft serviceability. At the time of the audit, 27 MRH90 aircraft had been accepted by DMO. The Army’s 5th Aviation Regiment was assigned seven MRH90 aircraft, Navy’s 808 Squadron was assigned six MRH90 aircraft, and the Army Aviation Training Centre was assigned eight MRH90 aircraft. Five MRH90 aircraft were undergoing Retrofit and one was in Deeper Maintenance servicing at Australian Aerospace’s facility in Brisbane.

Audit objective and scope

15. The audit objective was to assess the Department of Defence’s progress in delivering Multi‑Role Helicopters (MRH90 aircraft) to the ADF through AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 and 6, within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters.

16. The timeline covered by this audit extended from the MRH90 Program’s requirements definition phase in 2002, to progress achieved by April 2014.

17. The audit approach closely followed the systems engineering processes that Defence uses to manage the capability lifecycle of projects. The ANAO did not intend, nor was it in a position, to conduct a detailed analysis of the full range of engineering issues being managed within the MRH90 Program. Rather, the audit focused on the MRH90 Program’s progress thus far in establishing the management structures and processes used to deliver the aircraft within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters.

18. The high‑level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s performance were as follows:

- the requirements definition phase of the MRH90 Program, acquisition strategies and plans, and capability development policy and processes should be in accordance with internal Defence systems engineering procedures;

- the criteria used in the tender evaluation and selection process should reflect the approved capability identified through the requirements definition phase;

- the acquisition phase of the MRH90 Program, and test and evaluation leading to system acceptance, should meet the required technical, operational and safety regulatory requirements;

- the process involved in certifying the safety and fitness for service of the aircraft should meet the required technical, operational and safety regulatory requirements; and

- MRH90 sustainment arrangements should enable the aircraft to achieve agreed operational readiness requirements within approved budgets.

19. The audit report, which responds to the audit objective, refers to submissions received, and formal decisions made by government in August 2004 and April 2006. These submissions and decisions were central to the course of the MRH90 aircraft acquisition, and to an understanding of issues involved in the tender processes undertaken and their consequences. I have concluded that the inclusion of this information is not contrary to the public interest.12 The audit report does not extend to commenting on the deliberations of government beyond matters reflected in formal decisions.

Overall conclusion

20. At a budgeted cost of some $4.013 billion, the AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 and 6 Multi‑Role Helicopter (MRH90) Program is to acquire 47 helicopters and their support system for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Under the program, a single helicopter type has been selected to meet multiple ADF capability requirements, including Australian Army Airmobile Operations, battlefield support and support to Special Operations; and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) requirement for Maritime Support Helicopters (MSH) that operate from RAN ships. The helicopters are a central element of the planned expansion of the ADF’s amphibious deployment and sustainment capability.

21. In December 2002, the then Prime Minister announced the acceleration of the purchase of additional troop lift helicopters (AIR 9000 Phase 2) to enable a squadron of helicopters to be based in Sydney. The two main contenders for AIR 9000 Phase 2 offered significantly different designs—Australian Aerospace offered the Mark I version of the NH90 Troop Transport Helicopter design, primarily based on the United States (US) civilian helicopter design standard with European amendments13; and Sikorsky offered the Mark III version of the US Army battlefield utility helicopter, the S‑70M Black Hawk designed to US Military Standards. These designs have indelible impacts on military role suitability, and for that reason both the MRH90 and S‑70M design features are mentioned throughout this report.

22. In 2004 and 2006, the then Australian Government selected an Australian variant of the NH90 (known as the MRH90) to meet the ADF’s multi‑role helicopter requirements. Government formally approved the acquisition of 12 MRH90 aircraft through AIR 9000 Phase 2 in August 2004 on the basis that strategic and other government considerations outweighed the cost advantage of the Sikorsky proposal; and government approved the acquisition of another 34 MRH90 aircraft through Phases 4 and 6 in April 2006. Australian Aerospace, a Eurocopter subsidiary, is the Prime Contractor for the MRH90 Program, for both the acquisition and sustainment of the ADF’s MRH90 fleet. The MRH90 aircraft are assembled by Australian Aerospace in Brisbane from complete assemblies supplied by Eurocopter.

23. Following MRH90 aircraft flight trials from HMAS Choules in April and May 2012, the Navy reported impressive handling over the deck and that the aircraft showed considerable potential for embarked operations. However, the MRH90 aircraft also remain subject to a range of design rework in order to operate in high‑threat environments. In April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that the MRH90 aircraft has shown that it has the potential to offer greater capability in some areas than the Black Hawk and the Sea King, and Defence continues to adjust operational tactics, techniques and procedures to account for the differences between the platforms.

24. By March 2014, over $2.4 billion had been spent acquiring and sustaining the MRH90 aircraft, with 27 delivered. However, the MRH90 Program was running some four years behind schedule, with the first Operational Capability milestones for both the Army and the Navy yet to be achieved. Considerable work remains to implement and verify some design changes, and to adjust operational tactics, techniques and procedures, in order to develop an adequate multi‑role helicopter capability for Army and Navy operations.

25. The difficulties experienced by the MRH90 Program are primarily a consequence of program development deficiencies and acquisition decisions during the period 2002 to 2006. That period included requirements definition, the source selection process and the establishment of acquisition and sustainment contracts. The history of the MRH90 Program shows that when these crucial stages of program development are not appropriately performed, then there are likely to be serious and potentially long‑term consequences for capability delivery and Commonwealth expenditure.

26. Defence’s helicopter capability requirements definition was inadequate, did not properly inform the source selection process, and led to gaps in contract requirements. Defence also did not effectively assess the maturity of the MRH90 and S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft designs, and the potential implications of immaturity, during the source selection process and to inform the development of contracts. Further, the acquisition and sustainment contracts established by Defence did not contain adequate protections for the Commonwealth.

27. The decision by the then Australian Government in 2004 to approve the acquisition of the MRH90 aircraft, instead of the initial Defence recommendation that the S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft be acquired for Phases 2 and 4, has had significant implications as a consequence of: unforseen immaturity in the MRH90 system design and the support system; the continuing need to modify some design elements to meet multi‑role capability requirements; and the high cost of sustaining the aircraft.

28. Defence has applied a range of strategies directed toward addressing aircraft deficiencies and achieving better contractual outcomes for the acquisition and sustainment of the aircraft. These strategies commenced in 2007 after Australian Aerospace delivered the initial aircraft, and were ongoing in 2014. They have included the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) suspending acceptance of aircraft, the listing of the MRH90 Program as a Project of Concern, and negotiation of revisions to the acquisition and sustainment contracts. Ongoing management attention across the areas of Defence with acquisition, sustainment and capability management responsibilities remains necessary for the MRH90 Program to provide an acceptable and affordable MRH90 aircraft capability for Army and Navy operations in a reasonable timeframe.

29. The following discussion of the audit findings is structured around the key elements of the acquisition: the source selection process, including requirements definition; acquisition progress and remediation; and cost, schedule and capability. The audit also highlights a number of key lessons from the MRH90 Program, which have also been observed in previous reviews of Defence and in previous ANAO audits.

Source selection process, including requirements definition

30. Under the 2002 ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan, Defence’s strategy was to rationalise the number of helicopter types in service with the ADF through the acquisition of a multi‑role helicopter capability. Defence planned to acquire the capability via a Military‑Off‑The‑Shelf (MOTS) procurement to reduce the risk of cost escalation and schedule slippage. A MOTS helicopter procurement may confidently be undertaken when tests and evaluations are complete; full‑rate production is well underway; and mature sustainment supply chains are in place to support the aircraft. However, when Australia planned to acquire troop lift helicopters in the early 2000s, the solutions offered by the main contenders had not yet achieved these milestones.

31. The MRH90 Program source selection process commenced with a Phase 2 Request for Proposal (RFP) process in 2003. There followed an Offer Development and Refinement Process (ODRP) for a combined Phases 2 and 4. Government ultimately decided to separate these phases to make an initial Phase 2 purchase in 2004, and Defence subsequently conducted a combined Phases 4 and 6 procurement process in 2006.

32. During the Phase 2 RFP process in 2003, Defence noted uncertainty about development and certification risks for the two main contenders (the MRH90 and the S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft), and had low–medium confidence in cost estimates, as both aircraft remained under development at the time and were not yet MOTS aircraft. However, this assessment did not lead Defence to undertake a thorough analysis of the maturity of the two aircraft options, and associated cost and schedule risks. Defence could have undertaken more thorough analysis of the available options during the remainder of the source selection process14, in order to better inform government decision making on the selection of a preferred aircraft.

33. By way of background, Air 9000 Phase 2 was a pilot project in Defence for a new approach to achieve more rigorous capability requirements definition. However, there were a range of shortcomings in the defined helicopter capability requirements for Phases 2, 4 and 6. These shortcomings have had significant implications, in that the assessment of Australian Aerospace and Sikorsky’s Phase 2, and combined Phases 2 and 4 proposals, was made against an incomplete set of requirements. While Defence provided candid advice to its Minister on its preferred option and the possible separation of Phases 2 and 4, in the absence of comprehensive helicopter capability requirements definition, Defence was on the back foot. Defence was not positioned to readily identify areas in need of developmental work for the respective aircraft, and to confidently inform ministers on the respective strengths and weaknesses of the proposals.

34. In June and July 2004, Defence recommended the S‑70M Black Hawk option following the Phases 2 and 4 ODRP on the basis of its cost advantage, robust construction, ballistic protection and crashworthiness.15 Defence also found that the MRH90 aircraft would meet the capability requirement. Defence considered that the MRH90 was a more marinised aircraft, and that the Australian Aerospace offer had Australian industry capability advantages.

35. It is a matter for the government of the day to make decisions on major Defence capability proposals after considering the detailed submissions brought forward by Defence and its Minister, and being persuaded that the acquisition represents value for money for the expenditure of public funds. Following Defence’s initial recommendation that the Black Hawk option be selected for Phases 2 and 4, the Minister for Defence requested that Defence develop a revised submission that asked ministers to choose between the two aircraft options; and government subsequently directed that Defence bring forward a submission recommending acquisition of the MRH90 for Phase 2 only. Developing cost estimates for Phase 2 only was complicated by the fact that Defence had only low–medium confidence in cost estimates provided as part of the initial RFP process, and because the ODRP process focused on combined Phases 2 and 4 estimates. Defence’s submission also included estimated support costs, but only with low confidence.

36. On 30 August 2004, government formally approved the acquisition of 12 MRH90 aircraft, together with associated training and support equipment and facilities, under a $1 billion project that was subject to satisfactory conclusion of negotiations. Government agreed that the MRH90 be selected as the preferred helicopter for AIR 9000 Phase 2 based on its generally better troop-lift capacity and superiority in the amphibious role. The following day, caretaker arrangements took effect in advance of the Federal Election held on 9 October 2004, and the Government announced the acquisition.

37. The selection of 12 MRH90 aircraft for Phase 2 was followed by formal government approval of 34 MRH90 aircraft for Phases 4 and 6 in April 2006. Defence had envisaged that the helicopter chosen for Phase 2 would also be the preferred helicopter for Phases 4 and 6, in order to generate efficiencies in fleet management and through‑life support under its fleet rationalisation strategy. In the event, the choice of aircraft has had significant implications for Defence capability and costs, due to unforseen immaturity in the MRH90 system design and the support system, the continuing need to modify some design elements to meet multi‑role capability requirements, and the high cost of sustaining the aircraft.

38. As mentioned in paragraph 2, the ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan involved a partnership with a Prime Contractor to implement the AIR 9000 Program through a Strategic Agreement. This agreement was to complement long‑term sole‑source helicopter acquisition and sustainment contracts, through the sharing of goals, risks and communication strategies, and by providing for cost visibility and audit access. However, the initial MRH90 acquisition and sustainment contracts did not establish a strong foundation for a successful strategic partnership, nor did they adequately protect the Commonwealth’s interests. The abovementioned shortcomings in requirements definition meant that many key capability requirements were not included in the acquisition contract and, as a consequence, Defence has not had contractual remedies for related shortfalls in the capability to be provided by the MRH90 aircraft. Further, the initial MRH90 sustainment contract resulted in support costs that significantly exceeded expectations. The contract’s provisions were largely ineffective, as they were based on the incorrect premise that the number of fully developed (mature) MRH90 aircraft delivered through the acquisition contract would increase in a timely manner and trigger the sustainment contract’s performance management regime. When this did not occur, DMO was obliged to take remedial action by negotiating contractual changes with Australian Aerospace.

Acquisition progress and remediation

39. Since the establishment of the acquisition and sustainment contracts covering Phases 2, 4 and 6, Defence has had to respond to a broad range of MRH90 Program challenges. Australian Aerospace has delivered MRH90 aircraft later than scheduled, and the aircraft have been delivered with much reduced levels of operational capability, which did not satisfy the set of requirements that had been contracted. Defence has approved many temporary and permanent design waivers for the aircraft with respect to the original requirements.16 Further, due to the immaturity of the design, DMO has agreed to accept the MRH90 aircraft with three Product Baseline upgrades which are expected to bring the aircraft to their contracted standard; and three software builds which make evolutionary software improvements.17 The first 13 aircraft delivered have had to undergo an extensive Retrofit Program to Product Baseline 3. As a consequence of these factors, DMO has undertaken a design compliance assessment workload that has far exceeded that needed for MOTS acquisitions.18

40. Elements of the MRH90 cabin and role equipment have been the subject of significant ongoing design issues. At the time of the audit, the MRH90 self defence gun system, cabin seating and cargo hook were being redesigned to overcome significant operational deficiencies. Further, operational test and evaluation had not validated the ability of the MRH90 aircraft to satisfy any of the 11 Operational Capability milestones set by the Army and Navy.

41. The reliability and maintainability of the aircraft accepted by DMO have also been low, which has resulted in the Army revising its MRH90 Acceptance into Operational Service plan six times. Overall, Defence has had to cope with ongoing commercial and technological management issues which are yet to be fully resolved, with sustained improvements in MRH90 capability and value for money yet to be demonstrated.

42. DMO suspended acceptance of the MRH90 aircraft in November 2010 and February 2012 as a result of persistent technical issues. The project also underwent diagnostic reviews (known as Gate Reviews) in February and September 2011.19 These reviews positioned Defence to work with Australian Aerospace to implement a remediation plan to improve the availability of the helicopters by addressing engineering and reliability issues. In November 2011, Defence contemplated options to terminate or truncate the MRH90 acquisition contract and pursue alternative options. In the same month, the then Minister for Defence announced that the MRH90 Program had been listed as a Project of Concern, which is a process that aims to focus the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects.

43. These reviews and actions assisted DMO in the negotiation of major revisions to the acquisition and sustainment contracts through Deeds of Agreement 1 and 2, signed in October 2011 and May 2013 respectively. Deed 1 addressed a range of technical, legal and commercial issues that had arisen between Defence and Australian Aerospace in respect to the acquisition and sustainment contracts. Deed 2 addressed aircraft reliability and support, and sought to improve the value for money of sustainment arrangements. As part of the Deed 2 negotiations, Defence settled a Liquidated Damages and common law damages claim, by re‑baselining the acquisition contract in return for a range of improvements, including new aircraft cabin seats, the 47th MRH90 aircraft, a Repair By the Hour Sustainment Scheme, final spares and support equipment, a warranty that sufficient major spares had been procured to support the mature rate of effort, configuration changes and obsolescence resolution.

Cost, schedule and capability

44. As at May 2014, the DMO considered that there was sufficient budget remaining for the project to complete against the agreed scope.20 The current out‑turned overall acquisition contract price for the first 46 MRH90 aircraft and their support system is $2.9909 billion (2014–15 PRE ERC21 price basis). On that basis, the average Unit Procurement Cost (also known as the weapon system cost) for each of the 46 MRH90 aircraft is $65.020 million (2014–15 PRE ERC price basis)22, or $63.636 million if the 47th aircraft is included (2014–15 PRE ERC price basis).

45. Assuming that MRH90 aircraft support (sustainment) costs may increase by three per cent per year due to price inflation, then the potential contracted services cost of sustaining the 47 MRH90 helicopters, in their current configuration, until their Planned Withdrawal Date of 2040, may be in the order of $8.730 billion (in out‑turned price terms). On that basis, the total contracted cost of acquiring and sustaining the 47 MRH90 aircraft until 2040 will be some $11.7 billion.

46. With the acquisition of MRH90 aircraft, the Army S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk fleet withdrawal from service was to commence in January 2011 and be completed by December 2013. In April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that the S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk fleet’s withdrawal from service commenced in January 2014 and is scheduled to be completed by June 2018. Defence also informed the ANAO that the budgeted cost of this S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk fleet service life extension is $311 million. The Chief of Army has noted the significant financial implications for the Army that arise from operating both the Black Hawk and MRH90 fleets:

Extended concurrent operation of both Black Hawk and MRH90 fleets, due to immaturity and delays with MRH90 are creating significant problems for funding of Army aviation. The inability to fund both platforms through transition is likely to require compromises to levels of capability.23

47. The MRH90 aircraft received Australian Military Type Certification (AMTC)24 in April 2013, 53 months later than originally scheduled. In April 2014, the Chief of Army redefined the first Operational Capability milestone for the Army MRH90 aircraft to a limited capability subset involving a low‑threat environment and no combat capability. This redefined milestone is scheduled to be achieved in July 2014, 39 months later than the original Operational Capability plan, with a second Operational Capability milestone covering Army’s first Airmobile capability (a high‑threat combat capability) now scheduled for September 2014, 41 months later than the original Operational Capability plan. The first Operational Capability milestone for the Navy MRH90 aircraft is currently delayed by 45 months, with an Operational Capability recommendation to be made by the RAN Test, Evaluation and Acceptance Authority to the Chief of Navy following receipt of acceptable role equipment qualification reports. Under the original MRH90 Final Operational Capability (FOC)25 milestone, the first 46 MRH90 aircraft were scheduled to be in service by July 2014. FOC is now scheduled for April 2019, which is a delay of 57 months from the original estimate.

48. As previously indicated, the MRH90 aircraft design has proven to be more developmental than expected during the source selection in 2004 and 2006. A large number of aircraft design issues have impacted the achievement of capability milestones, including the self defence gun mount, the cargo hook release mechanism and the fast rope rappelling device. At the time of the audit, the MRH90 self defence gun system, cabin seating and cargo hook were being redesigned to overcome significant operational deficiencies. Further, low MRH90 aircraft reliability, maintainability and flying rate of effort have impacted aircrew training and the achievement of capability milestones. A capability gap has developed for Navy, as the RAN Sea King helicopters were retired in December 2011.

49. Defence advised its Minister when negotiating the acquisition contract in May 2006 that an overarching Australian Industry Commitment target of 37 per cent translated to a $1.1 billion investment in Australian industry activities for the combined Phases 2, 4 and 6. ANAO examination of Defence’s acquisition contract expenditure on these phases indicated that expenditure on Australian industry activities was trending significantly below the target of 37 per cent.

Lessons learned

50. This audit again highlights the importance of Defence capability development, which the Review of the Defence Accountability Framework observed is a process which ‘has a profound effect on Defence as a whole, and is where much policy and organisational risk concentrates.’26 The ANAO’s analysis in the Major Projects Reports over the last five years, along with the findings of a range of ANAO performance audits of individual Defence major projects and related topics, indicate that the underlying causes of schedule delay in the acquisition phase can very often relate to weaknesses or deficiencies in the requirements phase of the capability development lifecycle.27

51. The ANAO has not made recommendations in this report, as Defence already has relevant management processes suitable for defining capability requirements, formulating cost‑effective major capital equipment acquisition strategies, and delivering program outputs. The key issue for Defence is to consistently apply these processes to the standards required. The ANAO notes that the MRH90 Program proceeded into its acquisition and sustainment phases with inadequately defined capability requirements, and inadequate program cost investigations and analysis. While it was a government decision to acquire the MRH90 aircraft and not the option initially proposed by Defence, the department did conclude that the MRH90 aircraft was a valid option.

52. One of the major causes of schedule delay in the acquisition phase of Defence major projects is inadequate specification of capability requirements. The procedures to verify and validate compliance with requirements also need to be adequately defined and agreed.28 In the case of the MRH90 Program, even though battlefield helicopter requirements were well known to Defence, these were not translated into adequate functional and performance specifications, and followed‑through as part of tender evaluations and program approval submissions to government.

53. Successive Defence reviews have highlighted that risk can be decreased through MOTS solutions.29 The ANAO has also observed that schedule delay in the acquisition phase of Defence projects has resulted where the capability solution approved by government was not adequately investigated in terms of its technical maturity, including the threshold issue of whether an option is truly off‑the‑shelf or developmental in some respect.30 The MRH90 Program risk mitigation strategy was based on the acquisition of a MOTS solution, which is a sound and well‑proven strategy. However, this strategy was not applied at the time the then Government pursued an accelerated AIR 9000 Phase 2 acquisition decision. The two options under consideration remained in the development phase of the production lifecycle, and were not yet MOTS aircraft. This led to the MOTS strategy being written out of the AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 and 6 specifications, but with no compensating or more appropriate risk mitigation strategies. Following the commitment to procure the MRH90 aircraft, Defence has had to manage a range of systems development issues, many of which have not been resolved, or have been resolved at additional cost.

54. Defence’s inability to maintain the MOTS strategy highlights the need to consider the ideal timing of capability acquisition in formulating acquisition strategy. Developing new military helicopters or upgrading existing models involves a lengthy process of design, prototype construction, test and evaluation, airworthiness certification and full‑rate production approval. There are clear advantages in acquiring helicopters after the aircraft are certified and full‑rate production has commenced, because operational test and evaluation outcomes should have been factored into the design; technical and operational airworthiness issues should have been resolved; and support system arrangements established to ensure the specified level of operational availability is achieved efficiently and effectively.

55. On this occasion the recommendations of the Defence procurement process for the acquisition of this helicopter capability were not adopted by the then Government. While it is open to government to decide on the acquisition of Defence capability and to have regard to wider strategic considerations, Defence needs to be confident in its advice to government so that decision‑making is properly informed, including in respect to cost estimates and the developmental risks associated with proposed acquisitions. Put another way, any significant uncertainties in relation to key factors on which decisions are likely to be based should be drawn to the attention of government.

56. The shortcomings in the MRH90 Program requirements, and the lack of recognition of aircraft immaturity, resulted in the acquisition and sustainment contracts containing inadequate protections for the Commonwealth. These contracts also did not provide effective performance incentives, measurement and feedback systems. These key components have had to be negotiated into the acquisition and sustainment contracts at a time when the Commonwealth had reduced bargaining power; that is, following the signing of the decade‑long acquisition and sustainment contracts. The sustainment contract involves a model whereby functions normally performed by a DMO Systems Program Office are instead the responsibility of the MRH90 acquisition and sustainment Prime Contractor; a model which is considered to offer potential efficiencies but also involves some risks. Should a similar model be adopted for future major capital equipment programs, sufficient attention should be given from the outset to the development of appropriate performance incentives and related performance management approaches.

Key findings by chapter

Additional Troop Lift Helicopter project definition and tender evaluation (Chapter 2)

57. AIR 9000 Phase 1 produced the 2002 ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan, which sought to rationalise the number of helicopter types in service with the ADF through the acquisition of a multi‑role platform. The Master Plan envisaged that fleet rationalisation would generate efficiencies in through‑life support and personnel requirements. Following the October 2002 Bali Bombings, in December 2002, the then Australian Government accelerated the purchase of additional troop lift helicopters (AIR 9000 Phase 2) to enable a squadron of helicopters to be based in Sydney. Consistent with the strategic intent to reduce aircraft types, Defence considered at the time that the helicopter chosen for AIR 9000 Phase 2 would be the preferred solution for Phase 4 and possibly Phase 6.31

58. In May 2003, Defence released an RFP for AIR 9000 Phase 2 to three prospective suppliers. AgustaWestland offered the EH101 Merlin, Australian Aerospace offered the NH90 (to be developed for Australia as the MRH90) and Sikorsky offered the S‑70M Black Hawk.32 In December 2003, the then Minister for Defence agreed to a Defence recommendation to set aside the AgustaWestland EH101 offer33, and to proceed with bids from Australian Aerospace and Sikorsky for a combined AIR 9000 Phases 2 and 4. Defence noted in ministerial advice that despite seeking a Military‑Off‑The‑Shelf (MOTS) solution, there was continuing uncertainty about development and certification risks for the two remaining offers. Notwithstanding this assessment, in early 2004, at the time of the commencement of the AIR 9000 Phases 4 and 6 Offer Development and Refinement Process (ODRP), Defence identified few high technical risks for the project as a consequence of the MOTS strategy. Further, Defence’s ministerial advice did not address the technical risks associated with aircraft immaturity in any detail throughout the remainder of the AIR 9000 source selection process.

59. In June and early July 2004, Defence recommended to the Minister for Defence: a combined Second Pass approval for AIR 9000 Phases 2 and 4; the acquisition of 12 S‑70M Black Hawk helicopters; and either upgrading the ADF’s existing 34 S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk aircraft to the S‑70M standard, or replacing these with 36 new S‑70M aircraft. Defence noted that the recommendation was supported by a range of Defence senior officers, including the Secretary for Defence, the Chief of the Defence Force, Service Chiefs and the Chief Executive Officer Defence Materiel Organisation. While reaching the conclusion that both the MRH90 and S‑70M Black Hawk would meet the required capability, Defence preferred the S‑70M Black Hawk on the basis of its cost advantage34, crashworthiness, robustness and battlefield survivability. On the other hand, Defence considered that the MRH90 was a more marinised aircraft, and that the Australian Aerospace offer had Australian industry capability advantages.

60. On 30 July 2004, Defence received probity advice on the potential legal implications of the Government departing from the source selection process35, which had recommended the S‑70M Black Hawk. The probity adviser noted that the ODRP process was subject to the selection of a preferred respondent on the basis of ‘value for money, consistent with Commonwealth purchasing policies, affordability, strategic considerations and other whole of government considerations’.36 The probity adviser also observed that ‘it would potentially be open to the Government to decide that, despite the conclusions of the ODRP evaluation and the Source Selection Report, the [Australian Aerospace] proposal represented better value for money than the Sikorsky proposal, when those conclusions are considered in light of overarching strategic or whole of government considerations’. The adviser further noted that this scenario assumed such strategic or whole of government considerations existed, and that the Government could reasonably argue that they outweighed the Sikorsky price advantage.37

61. In accordance with direction provided by the Minister for Defence and government, Defence developed alternate draft submissions, initially to ask ministers to choose between the two aircraft options, and later recommending acquisition of the MRH90 for Phase 2 only (see below). On the same day as receiving the abovementioned probity advice (30 July 2004), Defence provided a draft submission to its Minister that left open the recommendation as to which helicopter should be selected. The submission rated the overall risk of Australian Aerospace’s proposal as medium and Sikorsky’s proposal as medium–high. Technical risk was rated as medium for both proposals and the differentiating factor was cost risk, which was rated as medium for the Australian Aerospace proposal and high for the Sikorsky proposal.38

62. In early August 2004, Defence provided candid advice to its Minister regarding the possible separation of Phase 2 and Phase 4, including that cost data would be less reliable and that purchasing fewer aircraft would result in a premium of about $4 million per aircraft. On the same day, government formally indicated it was disposed to select the Australian Aerospace MRH90 helicopter for Phase 2 only, and asked the Minister for Defence to bring forward a submission outlining the case for, and financial implications of, proceeding with Phase 2 only, and selecting the MRH90 over the S‑70M.39

63. A subsequent August 2004 submission to government recommended the MRH90 for Phase 2. The submission cited strategic and other government considerations of relevance in selecting the preferred helicopter, including the primary importance of amphibious operations for Phase 2, and the prospect of cooperation with another country in a joint MRH90 purchase. The MRH90 aircraft was also assessed as having better troop lift capacity and superiority in the amphibious role. Developing cost estimates for Phase 2 only was complicated by the fact that Defence had only low–medium confidence in cost estimates provided as part of the initial RFP process, and because the ODRP process focused on combined Phases 2 and 4 estimates. While recognising a cost advantage for the S‑70M Black Hawk proposal, the submission gave limited attention to the relative acquisition cost of the two options for Phase 2 only.40 The submission also included estimated support costs, but with low confidence. An additional squadron of MRH90 aircraft was estimated to cost $60 million per annum and a squadron of S‑70M aircraft $70 million per annum.

64. On 30 August 2004, government formally approved the acquisition of 12 MRH90 aircraft, under a $1 billion project that was subject to satisfactory conclusion of negotiations. Government agreed that the MRH90 be selected as the preferred helicopter for AIR 9000 Phase 2 based on its generally better troop-lift capacity and superiority in the amphibious role. On 31 August 2004, caretaker arrangements took effect in advance of the Federal Election held on 9 October 2004, and the Government announced the acquisition of the 12 MRH90 aircraft. The Government also announced that the helicopters would be based in Townsville, which would release a squadron of Black Hawks to move to Sydney to reinforce the ADF Special Forces located there.41 The first MRH90 was to be delivered in 2007, with all 12 aircraft to be delivered by 2008.

65. The decision to announce the acquisition prior to contract negotiations potentially placed Defence in a more difficult bargaining position. Contract negotiations for the 12 MRH90 aircraft and their support system became protracted. It was not until 2 June 2005 that the acquisition contract for 12 MRH90 aircraft was signed, at a value of $912.49 million (January 2004 prices).42 Under the contract, there were notable reductions in deliverables when compared to the government Second Pass approval decision.43 The first of the Phase 2 aircraft was to be delivered in December 2007, with all 12 aircraft to be delivered by 2010. In June 2005, prior to acquisition contract signature, Defence advised government that the MRH90 aircraft were now estimated to cost $75 million more per year to sustain than the S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft when personnel and fuel requirements were included. On 29 July 2005, the sustainment and program agreement contracts were signed at a value of $748.48 million (January 2004 prices). The initial 10‑year sustainment period was due to start from the In‑Service Date of 18 December 2007.

66. Defence subsequently pursued a combined First and Second Pass approval for both Phases 4 and 6. Defence developed two acquisition business cases: for an MRH90 option and for an S‑70M Black Hawk option, drawing on tender information previously provided by Australian Aerospace and Sikorsky, while also negotiating a contract change proposal with Australian Aerospace.44 Defence envisaged that the MRH90 aircraft would also be the preferred helicopter for Phases 4 and 6, consistent with the objective of rationalising the helicopter fleet and generating efficiencies in fleet management and through‑life support. In April 2006, a submission to government for Phases 4 and 6 recommended acquiring the MRH90 to replace the Army S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk and Navy Sea King helicopters on the basis that: it was a better capability; there would be low through‑life costs with efficiencies generated by rationalising the utility helicopter fleet and development; and the acquisition cost of the MRH90 was similar to the Black Hawk option once full fleet acquisition costs were included. Despite having already bought 12 MRH90 aircraft as part of Phase 2, the submission compared the option to acquire the additional 34 MRH90 aircraft45 with the original 48 S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft rather than a reduced number of 42 S‑70M Black Hawk aircraft46 that would be required for Phases 4 and 6. A more appropriate comparison of aircraft numbers would have shown that the Black Hawk option was less expensive.

67. On 26 April 2006, government formally approved Air 9000 Phases 4 and 6, and the MRH90 acquisition contract was amended on 30 June 2006 to include the additional 34 MRH90 aircraft and their associated support system. At the same time, government formally approved a Real Cost Increase of $206 million to purchase elements of the support system that had been missing from the Phase 2 contract. These items included ground support equipment, a simulator, aircraft maintenance trainers and aircraft modifications.

68. Six days after government formally approved AIR 9000 Phases 4 and 6, on 2 May 2006, the ANAO presented for tabling the performance audit report Management of the Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter Project Air 87.47 The Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter (ARH) project was approved in August 2001 to provide a new, all‑weather reconnaissance and fire support capability for the ADF. The project involves the acquisition of 22 aircraft with supporting stores, facilities, ammunition and training equipment. The first four aircraft were built in France by Eurocopter and the rest were assembled in Brisbane by Australian Aerospace.

69. The ANAO audit report concluded that while Defence had intended that the ARH aircraft be an ‘off‑the‑shelf’ aircraft, the acquisition transitioned to become a more developmental program for the ADF, which resulted in heightened exposure to schedule, cost and capability risks, both for acquisition of the capability, and delivery of through‑life support services.48

70. On 10 May 2006, the then Prime Minister wrote to the then Minister for Defence raising concerns that the ANAO audit report identified a number of shortcomings with the management of the Tiger ARH project, and that it was unfortunate that Cabinet was not made aware of these issues in the context of its recent deliberations on Project AIR 9000 Phases 4 and 6, noting that the same prime contractor was involved. On 17 May 2006, after receiving advice from Defence, the Minister for Defence replied to the Prime Minister to allay his concerns. As part of his reply, the Minister noted that:

The MRH 90 is less complex than the ARH and is already entering service with both France and Germany, some 18 months in advance of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) program. A total of 10 aircraft are already flying for qualification and certification purposes. Significantly, the ADF is not the lead customer and will not carry the attendant developmental risk. …

Defence has applied the lessons learned from AIR 87 and the ANAO findings to the development of AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 and 6. Similarly, Australian Aerospace and Eurocopter have a greater experience with Defence processes, which has resulted in a demonstrated improvement by Australian Aerospace during Phase 2. Defence is confident that Australian Aerospace will deliver a timely and effective MRH 90 capability for the ADF, and remains the best value for money option.

71. If there was just one lesson to learn from the history of Defence acquisition projects, it would be the need to be respectful of the inherent risks in these complex transactions and not over‑confident that they are under control. Effective project management requires a deep understanding of the project status and environmental factors that have the potential to influence outcomes. For the acquisition of the MRH90 aircraft, Defence was on the back foot from the start in its ability to confidently offer advice, in not having a sound understanding of the requirements or the estimated costs, and has been endeavouring to recover ever since, with mixed success.

MRH90 capability requirements definition (Chapter 3)

72. The primary Defence Capability Definition Documents (CDDs) are: Operational Concept Documents (OCDs)49, Function and Performance Specifications (FPSs)50, and Test Concept Documents (TCDs).51 These documents are developed during a project’s requirements definition phase, and form part of the supporting documentation for the Second Pass capability proposal to government. They need to accurately reflect the user’s expectations of the system.52,53

73. AIR 9000 Phase 2 was a pilot project for the development of a set of CDDs under a revised Defence approach to the Capability Definition Phase of major projects. Defence recognised a lack of internal expertise in the development of CDDs at the time, and engaged a professional services provider to write the CDDs for Phase 2. However, there was still a need for Defence to verify that the delivered CDDs were of adequate quality. The Phase 2 OCD only partially followed the OCD guidance documents applicable at the time. The OCD describes the future multi‑role helicopter capability, but not the functionality and performance required of the helicopters and their associated support system, for each proposed solution. As a consequence, the extent to which the MRH90 and the S‑70M Black Hawk meet the specified operational concepts is unclear from the OCD. Further, there was scope for the FPS to be more specific, in order to reduce the risk of contractual disagreements during system design reviews and requirements verification and validation. While the Phase 2 FPS is large and detailed, it did not follow DMO’s then FPS guidelines, nor did it include functional modelling54 or trace the functional and performance requirements that should flow from the OCD.55,56 The Phase 2 FPS was also utilised for AIR 9000 Phases 4 and 657, and demonstrated the same shortcomings at the time these phases received government approval in April 2006.

74. Many important MRH90 mission requirements were not included in the OCD and/or contract FPS; and the compliance or fitness for purpose of the MRH90 against many mission requirements has yet to be demonstrated, with some key requirements remaining subject to redesign work. A prominent example illustrating immaturity in aspects of the aircraft’s design relates to the operation of the Self Defence Gun System (SGDS) and Fast Roping and Rappelling Device (FRRD). The FPS states that the MRH90 aircraft shall be able to be fitted with a Self Defence Gun Mount in each of the cabin doorways. However, the installation of door mounted guns interferes with a range of helicopter cabin workflow requirements. Troops need to move around the guns as they enter and leave the aircraft58, the doors need to be open when the guns are in use, and the FRRD cannot be safely used in the same doorway as the gun.

75. These and other issues have been partially addressed through changes to the MRH90 acquisition contract, and some of the design modifications are being implemented for Product Baseline 3 (PBL3)59 MRH90 aircraft. A key design change has been the development of an Enhanced MRH90 Armament System (EMAS). The EMAS reduces but does not eliminate the obstruction caused by the gun in the door, and the Army is therefore pursuing other options to improve the operation of the gun system and roping device. In a similar vein, there were no specific requirements in the OCD or FPS related to the width of troop seats, and as part of the Deed 2 settlement of a claim for Liquidated Damages and common law damages, Australian Aerospace is having the seats redesigned so that they are wide enough to cater for troops outfitted in Patrol Order.60

76. The need to rectify these and other issues has delayed the introduction into operational service of the MRH90 aircraft. In March 2014, the Chief of Army approved a revised Acceptance Into Operational Service (AIOS) schedule due to deficiency rectification and delayed aircraft delivery. The Chief of Army also directed that further investigation of options be undertaken to achieve relevant OCD requirements, including the potential for changes to tactics, techniques and procedures, to inform a subsequent decision.

77. The AIR 9000 OCD and FPS outlined a range of marinisation requirements, including a rotor brake, manual folding blades, the ability to operate on Landing Platform Amphibious ships and corrosion protection. However, there were gaps in the specification of marinisation requirements related to: automatic folding blades61; and cargo hook compatibility with a Navy rigid cargo strop.62 Trials of the MRH90 manual folding blades initially identified difficulties and risks in installing the blade pins. In April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that manual blade fold speed and efficiency had improved with increasing flight deck team experience. Another aspect of embarked operations is the conduct of vertical replenishment. The MRH90 cargo hook was found to be incompatible for use with a rigid strop when embarked, which would impede the MRH90 from conducting vertical replenishment operations with US and other coalition ships that use the rigid strop as standard load rigging equipment. In April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that an MRH90 cargo hook redesign to accommodate a rigid strop was underway, and that an alternate vertical replenishment configuration has been authorised.

78. It is also notable that the MRH90 aircraft are not being fitted with a recovery assist, securing and traversing system, which would better enable helicopter operations in wide ranging sea states from the RAN’s frigates and destroyers, consistent with the operating intent of the aircraft. In correspondence on this issue, Defence informed the ANAO in June 2014 that the MRH90 aircraft is replacing the Sea King aircraft in the Maritime Support Role, and the Sea King performed this mission effectively without a recovery assist, securing and traverse system.

79. Crashworthiness of helicopters is particularly important, because they operate at greater risk of fatal accidents, when compared to fixed-wing aircraft.63 The risks are further heightened for military helicopters that operate in a challenging environment. At the time of development of the Phase 2 OCD and FPS and contract signature, the US Department of Defense military standard for crashworthiness of helicopters (MIL‑STD‑1290A) was inactive.64 The 2004 version of the Defence Airworthiness Requirements Design Manual did not specify any standard for crashworthiness, and instead included a brief overview of crashworthiness design principles, which could have been used as the basis for some high‑level crashworthiness requirements for the multi‑role helicopter capability. However, there were significant gaps in the specification of crashworthiness requirements in the Phase 2 OCD and FPS. In terms of aircraft design, the MRH90 is qualified65 to a ‘modified’ MIL‑STD‑1290A, which the NH90 partner nations had agreed to prior to Defence being involved in the project.66 Defence informed the ANAO that it is not aware of any aircraft which currently meets the full untailored requirements of MIL‑STD‑1290A67, and expressed comfort with the overall crashworthiness design features of the MRH90. During the course of the program, Defence has identified modification options to improve MRH90 crashworthiness, and the Chief of Army has sought approval from the Defence Aviation Authority for a range of temporary and permanent waivers relating to MRH90 crash protection design shortfalls.

MRH Acceptance and Sustainment (Chapter 4)

80. Systems engineering standards and DMO system acquisition contracts involve the design and development of Mission Systems, and require contractors to produce a Verification Cross Reference Matrix (VRCM) that cross references the contracted requirements with the procedures by which compliance with those requirements are to be, or have been, verified.68 DMO Project Office personnel make compliance findings against each of the contractor’s compliance statements. As at April 2014, six and a half years after the In‑Service Date of December 2007, DMO had accepted Australian Aerospace’s compliance statements for 494 out of 553 requirements (89 per cent). Further, as at May 2013, the MRH90 Program Office had identified 35 acquisition contract requirements that the MRH design and construction had failed to achieved, relating to a broad range of design issues, including embarking and egress of troops, ballistic vulnerability and external sling load operations. These non‑conformances were accepted by the Commonwealth and waivers granted as part of the Deed 2 negotiations69 in order to increase the value for money of sustainment arrangements through contract changes. Defence informed the ANAO that as at April 2014, there remained another 32 temporary and four permanent design deviations not accepted by the Commonwealth. In June 2014, Defence further informed the ANAO that the number of permanent design deviations for the MRH90 aircraft is not unusual.

81. The ADF’s Technical Airworthiness Regulations set out the Australian Military Type Certificate (AMTC)70 and Service Release71 process. The AMTC and Service Release are issued after aircraft design issues and sustainment limitations identified during Special Flight Permit72 periods, and assessed by Airworthiness Boards, are resolved to the satisfaction of the Defence Aviation Authority. As a consequence of the ongoing delivery of MRH90 aircraft that did not comply with contracted specifications, the Chief of Air Force, in his role of Defence Aviation Authority, issued a series of Special Flight Permits, which authorised the scope of flying activity prior to AMTC and Service Release being granted.73 By the time of the Airworthiness Board meeting in April 2013, 16 MRH90 Airworthiness Issue Papers had been closed and nine remained open. These nine were reported to generally relate to longer‑term corrective actions and, with mitigations in place, did not preclude a recommendation for AMTC and Service Release. The MRH90 aircraft achieved AMTC and Service Release in April 2013. The 53-month delay in obtaining AMTC and Service Release required the aircraft to be operated under Special Flight Permits for longer than originally anticipated, and with more incremental variations to the Special Flight Permits than originally anticipated. At the same time, Service Release was granted subject to three limitations, including prohibition of the use of the Heavy Stores Carrier and the External Aircraft Fuel Tank, and prohibition of night formation flying. Defence expects that these aircraft limitations will be temporary.

82. Australian Aerospace has been engaged under the sustainment contract to undertake the majority of management tasks that are normally the responsibility of a DMO Systems Program Office (SPO). This outsourced SPO model was intended to create efficiencies in the delivery of SPO services to Navy and Army, and to significantly reduce the number of military and public service employees engaged in the support of the MRH90 fleet. Within this arrangement, Australian Aerospace is required to act on behalf of the Commonwealth, including fulfilling the role of Authorised Engineering Organisation (AEO) and Approved Maintenance Organisation (AMO), managing the logistics supply chain and sub‑contractors, and identifying opportunities to improve MRH90 fleet performance and reduce its cost of ownership. Commonwealth personnel in the MRH90 Logistics Management Unit retain responsibility for design acceptance and governance of outcomes, and for verifying and approving the payment of sustainment contract invoices received from Australian Aerospace.

83. Australian Aerospace is a wholly owned subsidiary of Eurocopter74 and so is responsible to its parent company to meet financial objectives and represent the interests of the parent company in Australia. Australian Aerospace is therefore under contract to deliver efficient and effective support to Defence while also having responsibility to its parent company, to maintain profitability and represent the interests of the parent. The experience of the MRH90 Program to date, including the high cost of sustaining the aircraft, highlights the potential for tensions to arise in the pursuit of these differing objectives. It also highlights the primary importance of an appropriate performance measurement regime to drive value for money and provide sufficient oversight of outsourced arrangements.

84. The sustainment contract for the first 12 MRH90 aircraft was signed on 29 July 2005. It was amended on 20 June 2006 to include the additional 34 MRH90 aircraft, and amended again in March 2012 and July 2013 to include agreements reached with Australian Aerospace as part of the Deed negotiations. The pre‑2012 contract provisions were found to be largely ineffective, as they were based on the premise that the number of fully developed (mature) MRH90 aircraft delivered through the MRH90 acquisition contract would be sufficient to achieve value for money via performance incentives and other incentives within the contract. Until June 2013, DMO was unable to apply the sustainment contract’s performance management regime, as there were insufficient MRH90 aircraft placed into operational service to trigger that regime. Furthermore, other sustainment issues affected the availability of the delivered MRH90 aircraft and further brought into question the value for money and cost-effectiveness of MRH90 sustainment expenditure.75

85. DMO and Australian Aerospace negotiated amendments to the MRH90 sustainment contract, which took effect on 1 July 2013 and are scheduled to expire on 19 December 2019. These amendments seek to improve MRH90 sustainment outcomes by reducing the total cost of ownership throughout the Life‑of‑Type, and increasing the number of serviceable MRH90 aircraft. The amendments establish a new performance management regime, which involves: financial incentives to improve MRH90 serviceability rates76; and a Quarterly Performance Management Fee based on a number of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).77 The sustainment contract amendments are a part of DMO’s decision to settle a claim for Liquidated Damages and common law damages, in return for improvements to MRH90 aircraft affordability and serviceability.

86. The contracted number of flight hours for the mature MRH90 fleet of 47 aircraft is 10 300 hours per year, which is an average of 220 hours per aircraft per year, or 4.2 hours per week. For the period July 2007 to April 2014, the MRH90 fleet’s actual flight hours consistently fell short of Army and Navy authorised flight hours.78 The shortfall was a result of the MRH90 aircraft being offered to DMO for acceptance when only partially compliant with their acceptance criteria, as well as a complex mix of sustainment shortfalls. A consequence of the reduced MRH90 flight hours, and the withdrawal from service of the RAN’s six Sea Kings in December 2011, has been the need for Navy to use its anti‑submarine S‑70B‑2 Seahawk helicopters in utility helicopter roles.79 The reduced flight hours of the MRH90 aircraft have also constrained Navy helicopter pilot flight training, as well as Navy’s ability to develop the MRH90 capability to the extent necessary to achieve the maritime Operational Capability milestones. The reduced MRH90 flight hours have resulted in the Army retaining its 34 S‑70A‑9 Black Hawk helicopters in operational service longer than planned. They have also constrained Army helicopter pilot flight training, and the ability to achieve the Army’s first Operational Capability milestone for the MRH90 aircraft.

87. DMO, Navy and Army records indicate that MRH90 fleet reliability and maintainability has fallen significantly short of expectations. In the 28 months up to and including April 2014, the MRH90 reliability rate exceeded the sustainment contract target of 24 faults or less per 100 flight hours on 18 occasions. Further, the MRH90 fleet’s Operational Level maintenance man‑hour per flight hour was averaging 27 hours per flight hour by April 2014, down from a peak of 97 hours in January 2012. Notwithstanding the decline, Operational Level maintenance man hour per flight hour remains high, particularly when compared to advice provided by Eurocopter to the Minister for Defence in February 2003 that the NH90 was designed to exploit new‑generation technologies to drastically reduce Life Cycle Costs and enhance reliability. In April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that it would take at least a year before the impact of the July 2013 sustainment contract revisions on aircraft reliability, maintainability and sustainment costs becomes apparent.

88. During the AIR 9000 Phases 2 and 4 ODRP in 2004, the Minister for Defence directed that there should be a high level of Australian industry involvement in the MRH90 program in areas of greatest importance, while containing cost and schedule within Defence Capability Plan limits. Defence advised its Minister when negotiating the acquisition contract in May 2006 that an overarching Australian Industry Commitment target of 37 per cent translated to a $1.1 billion investment in Australian industry for the combined Phases 2, 4 and 6. The approved MRH90 acquisition and sustainment contracts for Phases 2, 4 and 6 contained an Australian industry activity program, which was developed around themes and objectives. Defence informed the ANAO that it validates this program’s activities under the acquisition and sustainment contracts by examining invoices and accounting documentation. However, Defence had not measured or assessed the value of the Australian industry activities actually delivered. Further, following on from Deed 2, Defence and Australian Aerospace are negotiating a new Local Industry Plan, which will include activity milestones and performance measures.

Summary of agency and company responses

89. The proposed audit report was provided to Defence, and relevant extracts of the report were provided to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Aerospace Limited and Sikorsky Aircraft Australia Limited.

Defence

90. Defence’s covering letter in response to this audit report is reproduced at Appendix 1. Defence’s response to the audit report is set out below:

Defence welcomes the ANAO audit report on the Multi‑Role Helicopter (MRH90) Program. This extensive report demonstrates the complex nature of Australia’s helicopter replacement program which is integral to the Australian Defence Force and its conduct of combined operations. The report accurately highlights a number of challenges that Defence faces in transitioning from its current 3rd generation helicopters to 4th generation platforms.

Defence has made significant progress towards increasing efficiencies and maximising combat capability over a decade of continuous force mobility improvements and acquisitions. The experience gained from the MRH90 acquisition program stands Defence in good stead for acquisitions not only of helicopter systems, but across other capability acquisitions as well. In particular, DMO has learned substantial lessons in establishing and maturing a sustainment support system, by both Defence and industry; contract management; and accurate assessment of the maturity of proposed capability solutions.

Defence acknowledges that there is scope to realise further improvements in the MRH90 capability and anticipates continued maturity to the sustainment arrangements with associated benefits to cost of ownership. Defence is committed to managing the complexities of its mission and appreciates the regular reviews undertaken by the ANAO.

Australian Aerospace

91. Australian Aerospace’s full response to an extract of the audit report is reproduced at Appendix 1. Australian Aerospace’s summary response is set out below:

It is acknowledged that introduction of the MRH90 has been protracted for the reasons discussed in the Extract but Australian Aerospace is of the view that the aircraft is now gaining strong pilot support as a capable and safe aircraft by virtue of its modern avionics and advanced performance and flight characteristics. Australian Aerospace and its NHI Partner are committed to working with Defence on improvements to the cabin and related role equipments which will make the MRH90 a potent battlefield capability for the Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy in the future. As the Extract points out, significant changes to the MRH90 sustainment construct were agreed through Deed 2 and these arrangements are now showing very positive trends in Demand Satisfaction Rates and flight hours achieved. Australian Aerospace is confident that the issues with the MRH90 Program identified in the Extract are well known and are being addressed as quickly as possible in order to deliver the required capability for the ADF, in a cost effective way for the life of type of the helicopter.

Sikorsky

92. Sikorsky’s letter in response to the proposed report extract is reproduced at Appendix 1.

Footnotes

[1] The $3.073 billion Joint Project 2048 Phase 4A/4B Amphibious Ships Program is responsible for the construction of two 27 000 tonne Canberra‑class Landing Helicopter Docks (LHDs). These are to be named HMAS Canberra and HMAS Adelaide, and are scheduled to enter service in 2014 and 2015 respectively. Each LHD is designed to hangar up to 12 helicopters, and the integration of the MRH90 capability with the LHDs will be a significant aspect of the MRH90 Acceptance into Operational Service.

[2] The ADF Helicopter Strategic Master Plan is discussed in Appendix 2.

[3] The Defence Capability Plan lists major projects that Defence plans to present to government for approval over the next four years.

[4] The Second Pass approval process involves government endorsing a specific capability solution and approving funding for its acquisition.

[5] The other phases of AIR 9000 are as follows: Phase 3 was to upgrade the RAN’s S‑70B‑2 Seahawk aircraft, but this phase was replaced by Phase 8; Phase 5A is the engine upgrade for the CH‑47D Chinook aircraft; Phase 5C is replacing the CH‑47D Chinook with CH‑47F Chinook aircraft; Phase 5D is the accelerated acquisition of two replacement CH‑47D Chinook aircraft; Phase 7 is the new Helicopter Aircrew Training System (HATS); and Phase 8 is acquiring 24 MH‑60R Seahawk aircraft to replace the RAN’s S‑70B‑2 Seahawk aircraft.

[6] The Sikorsky S‑70M Black Hawk is the direct commercial sale version of the Sikorsky UH‑60M produced for the US Army, and shares the UH‑60M design characteristics.

[7] The final MRH90 aircraft support system includes an electronic warfare self protection support cell, a ground mission management system, a software support centre, an instrumented aircraft with telemetry, two Full Flight and Mission Simulators, and facilities infrastructure at Townsville, Oakey, Holsworthy and Nowra.

[8] The DCIC consists of the: Chief of the Defence Force (Chair); Secretary for Defence; Vice Chief of the Defence Force; Chief of Navy; Chief of Army; Chief of Air Force; Chief Executive Officer Defence Materiel Organistion; Chief Defence Scientist; Chief Financial Officer; First Assistant Secretary Capability Investment and Resources; and Deputy Secretary Strategy and Plans.

[9] Discussed at paragraph 8.

[10] On 2 January 2014, Eurocopter was renamed Airbus Helicopters. For the purpose of this audit, the company is called Eurocopter, as it was so named for the majority of the period covered by the audit.

[11] A fleet of 22 ARH (Tiger) aircraft has also been acquired from Australian Aerospace through AIR 87 Phase 2. The ARH acquisition project was the subject of an ANAO performance audit in 2005–06. See ANAO Audit Report No.36, 2005–06, Management of the Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter Project — Air 87, May 2006.

[12] Section 37 of the Auditor‑General Act 1997 outlines the circumstances in which particular information is not to be included in public reports, including if the Auditor‑General is of the opinion that disclosure of the information would be contrary to the public interest.

[13] See paragraph 3.82.

[14] In a similar vein, in DMO’s 2012–13 Major Projects Report (p.185), it was noted that:

The MRH Project was viewed as a Military Off‑The‑Shelf (MOTS) acquisition. Lessons associated with MOTS procurements include: that it is essential that the maturity of any offered product be clearly assessed and understood; and that elements of a chosen off‑the‑shelf solution may meet the user requirement.

[15] Defence noted that the Black Hawk recommendation had the support of the: Secretary for Defence, Chief of the Defence Force, Chief Capability Development Group, Chief Executive Officer Defence Materiel Organisation, Chief of Army and Chief of Air Force.