Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Materiel Sustainment Agreements

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to examine Defence’s administration of Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) and the contribution made by MSAs to the effective sustainment of specialist military equipment.

Summary

Introduction

1. Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) have been used since 2005 as customer–supplier agreements formalising the relationship between the Department of Defence (Defence) and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO)1 for the sustainment of specialist military equipment.2 Through the agreements, the Defence Capability Manager3 undertakes to supply funding, and the DMO undertakes the sustainment of specific platforms (such as a ship or aircraft fleet), commodities (such as clothing or combat rations) and services (such as provision of maritime target ranges). Sustainment involves the provision of in-service support, including repair and maintenance, engineering, supplies, configuration management and disposal action. Effective sustainment of ships, aircraft and vehicles is necessary to maintain the preparedness of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and enable the conduct of Defence operations.

2. In 2014–15, out of total funding of $35.781 billion, Defence budgeted $7.109 billion, or 20 per cent, for its Capability Sustainment Programme, with most of this funding transferred to the DMO.4 By way of context, the DMO’s sustainment expenditure has regularly exceeded its acquisition expenditure in the past decade.5

3. Sustainment activities are generally administered by the DMO’s Systems Program Offices (SPOs). The SPO serves as the single point of contact with industry, government entities, and other entities participating in the acquisition or sustainment of specialist military equipment. Generally, each major platform is managed by a single SPO, which may also manage the delivery of a commodity or a service.

Managing Defence’s sustainment function

4. The Australian Defence Organisation comprises the Department of Defence, the ADF and the DMO. The successful provision of Defence capability depends on the Defence Organisation as a whole collaborating effectively and the component parts meeting their respective functional responsibilities, including, for the DMO, acquisition and sustainment responsibilities. In September 2003, when the then Government approved the DMO’s transition to a prescribed agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act)6, the intent was for the DMO to be more performance-oriented and business-like, so as to improve procurement and support practices, and establish a more transparent relationship between Defence and the DMO.7

5. The DMO’s February 2004 Business Model noted the primacy of Defence as the customer, with responsibility for setting requirements and determining priorities within agreed funding levels; and that the DMO would be funded and managed on the basis of agency agreements for the services it delivered. The agency agreements were to facilitate funding flows and delineate responsibilities and accountability between Defence and the DMO, and provide better visibility of the costs of procuring and sustaining Defence assets. The agreements were to be refined and improved over several annual cycles. The lowest tier of these agreements, for sustainment, would be the MSAs:

At the tactical level, the scope, price and time frame for specific services between Defence and DMO would be captured in simple agreements that describe the products and services flowing from DMO’s Outputs—projects, sustainment and policy advice and services. […] The products/services described in these agreements must be meaningful, manageable and measurable by both parties and facilitated by a principle of open books between the two with agreed underlying assumptions clearly stated and risk management measures built in.8

6. The implementation of these agreements led to MSAs consisting of two levels. The first level is the Heads of Agreement, which is an overarching document that covers a series of Product Schedules. The Heads of Agreement contain the high-level framework establishing the partnership between each Capability Manager and the DMO. The second level of each MSA is the Product Schedules. Each Product Schedule deals with the sustainment of a specific platform, commodity or service for the relevant Defence Service or Group. The Product Schedule defines: the supplies and services that will be provided by the DMO; the budget that is provided by the Capability Manager; and standards for matters such as responsiveness, availability levels, and maintenance timeframes.

7. Most of Defence’s $7.1 billion sustainment budget for 2014–15 is included in the DMO’s sustainment budget of $6.185 billion9, and of this, some $5.683 billion is to be expended through seven MSAs incorporating 116 Product Schedules. The main MSAs are those between the DMO and each of the three Services. For 2014–15, the Chief of Navy MSA includes 36 Product Schedules valued at $1.976 billion; the Chief of Air Force MSA comprises 28 Product Schedules valued at $1.976 billion; and the Chief of Army MSA includes 45 Product Schedules valued at $1.504 billion.10 Since 2012, the previous practice of complete annual revision of the MSAs has been replaced by partial revision as needed, particularly of the financial sections of Product Schedules.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

8. The audit objective was to examine Defence’s administration of Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) and the contribution made by MSAs to the effective sustainment of specialist military equipment.

9. Four high-level criteria were developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s administration of MSAs:

- MSAs constitute an effective arrangement formalising the relationship between Defence Services/Groups and the DMO for sustainment activities.

- MSA Product Schedules clearly identify costs, deliverables and appropriate Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

- Risks, issues and constraints to achieving effective sustainment are identified in MSA Product Schedules, and appropriate management strategies are in place.

- Monitoring and reporting processes provide relevant and reliable information on sustainment activities.

10. The ANAO examined Defence’s MSA policy, procedures and systems, including reforms in these areas. The ANAO also examined Defence’s management of three Product Schedules. One Product Schedule was selected for each of the Navy, Army and Air Force:

- Navy’s FFH ANZAC frigates (Product Schedule CN0211), as one of the first MSA Product Schedules to be revised after the Rizzo Report12;

- Army’s Protected Mobility Vehicle (Bushmaster) fleet (Product Schedule CA04), which has been heavily used in Iraq and Afghanistan; and

- Air Force’s AP-3C Orion fleet (Product Schedule CAF04), which was heavily involved in the search for Malaysian Airlines flight MH-370 in the Indian Ocean.

Overall conclusion

11. In 2014–15, Defence budgeted over $7.1 billion, or some 20 per cent of total Defence resourcing, for the sustainment of specialist military equipment operated by the ADF. The majority of Defence sustainment services are provided either directly or indirectly through the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO), which applies some 50 per cent of its budget ($6.185 billion13) to sustainment. Defence has been using Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) since 2005 to formalise its requirements for sustainment services from the DMO, with the aim of facilitating effective and business-like relationships within the Defence Organisation. MSAs are contract-like arrangements that set out the level of performance and support required by Defence from the DMO, within an agreed price, as well as the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) by which service delivery will be measured.

12. Over the past decade, Defence and the DMO have established and continued to refine a generally sound MSA framework to facilitate the management of sustainment activity for specialist military equipment. The framework has enabled the Defence Organisation to clearly identify roles and responsibilities at a functional level, and individual MSAs document funding, deliverables, risks and performance measures for each sustainment product. Further, the development and maintenance of the MSA framework has encouraged and facilitated collaboration between Defence and the DMO at both the management and operational levels. The MSA framework has evolved over time, in light of practical experience and the risk appetite of the parties to individual agreements, and there is an ongoing role for Defence senior leadership to shape the direction of the framework so as to realise its full potential. More generally, there remains scope for Defence to enhance its sustainment management through the implementation, use and refinement of newly developed performance measures.

13. As discussed, the MSA framework has continued to evolve since 2005, with relatively bureaucratic processes being replaced over time by simpler arrangements. In particular, when the DMO commenced an MSA reform process in 2012, Defence stakeholders observed that the practice of annually reviewing the entire suite of MSAs was long and tedious, with too little emphasis on sustainment planning and performance management to deliver the best outcome with available funding. The reform process resulted in revised procedures for the management of MSAs, including a move towards developing more enduring MSAs and a simplified process for amending them. Under the new process, the Services and the DMO collaboratively review sustainment progress at both the management and operational levels, focusing on capability issues and required funding changes.

14. A key strength of the MSA framework is the capacity for Capability Managers to adjust individual Product Schedules in light of assessed risks. Following Navy’s inability to supply vessels requested by the then Government to assist in the clean-up after Cyclone Yasi in 2011, Navy demonstrated a relatively conservative risk appetite which resulted in more detailed Product Schedules and a requirement to approve changes at higher management levels. While the preferred approach is a matter for Navy’s senior leadership, there is scope to review future settings, in light of delays experienced in processing changes to Product Schedules and the emergence of undocumented workarounds to manage those delays.

15. A key objective when introducing the MSA framework was to capture the scope, price and timeframe for the provision of specific services, and individual Product Schedules do so. Defence has also taken steps to enhance its sustainment performance management through the development of standardised suites of performance measures. Between 2012 and 2014, the DMO, Navy and Army developed new performance measurement frameworks, including measures of availability, cost, schedule, and materiel deficiencies, which are to be reported through a new DMO system. These performance measures will not be fully implemented until the DMO system is operational, and at the time of the audit, the first phase of the system rollout was scheduled for May 2015. While the new performance measures should provide a firmer basis for the evaluation and active management of sustainment performance and costs, their establishment remains at an early stage.

16. The delivery of ADF capability relies in large measure on effective collaboration between key elements of the Defence Organisation—including the three Services and the materiel sustainment arm. The MSA initiative introduced a structured framework for engagement on sustainment matters; an approach of continued benefit irrespective of specific organisational arrangements within Defence.14 The practical effectiveness of the MSA framework largely depends on active and timely management of identified risks by Capability Managers and the DMO, and in that respect, a robust MSA framework is an aid to management, not an end in itself. To build on the progress made to date through MSAs, the ANAO has made two recommendations focusing on: the review of change management processes for Navy Product Schedules and their level of detail, to support more flexible management of MSAs and avoid undocumented workarounds in their administration; and clarifying the internal treatment of acquisition and sustainment funding.

Key findings by chapter

Materiel Sustainment Agreements (Chapter 2)

17. In 2012, Defence stakeholders agreed that the MSA process was bureaucratic and inflexible. There was an overriding focus on the annual development and approval of MSAs, rather than on using the MSA framework to actively plan and manage sustainment funding and activities. The DMO led an MSA reform project and reached agreement with Defence Services and Groups on streamlined arrangements. There was a particular focus on treating MSAs as enduring documents rather than updating them annually, and delegating authority for updating sections of Product Schedules to line management. The November 2012 DMO Standard Procedure on MSAs formalised the new arrangements, and MSAs were generally revised in accordance with the Standard Procedure in a timely manner. Service Chiefs informed the ANAO that the MSA reforms helped strengthen collaboration between Defence and the DMO in sustaining specialist military equipment.

18. The ANAO reviewed the structure and content of a sample of MSAs as at 2014, based on criteria developed by the ANAO in 2010 for effective cross-entity agreements.15 For the most part, the MSAs examined by the ANAO met the key characteristics of well-structured cross-entity agreements. The MSAs outline governance arrangements, respective roles and responsibilities, sustainment deliverables, performance reporting and monitoring arrangements, sustainment issues and risks, and dispute resolution procedures. These features of the MSAs serve to clarify accountabilities, coordination arrangements and relevant processes. However, there remains scope to improve KPIs—well-structured cross-entity agreements will generally include reciprocal KPIs which recognise that one entity’s ability to perform work often depends on timely action by the partner entity16, whereas MSA Product Schedules tend to include performance measures related to only one party—the DMO. More generally, the DMO, Navy and Army have developed new sustainment performance measurement frameworks which are yet to be fully implemented.

Materiel Sustainment Agreements in Operation (Chapter 3)

19. Regular interaction between Defence and DMO personnel at both the management and operational levels is essential to developing a shared understanding of expectations and reaching agreement on how to effectively manage sustainment activity. During 2012–13, the Services introduced revised arrangements for Defence–DMO management review of sustainment, incorporating periodic strategic-level reviews, six-monthly multi-product reviews, and ongoing scrutiny at the working level. For the ANZAC ship, Orion aircraft and Bushmaster vehicle fleets, product and working-level reviews were effective in focusing the attention of management on capability planning and changes, and related changes in funding.

20. MSA Product Schedules are updated as necessary to formalise changes in sustainment arrangements and funding agreed between Defence and the DMO. Army and Air Force followed the DMO Standard Procedure in delegating authority for updating Product Schedule sections to line management, and their implementation of the revised process, discussed earlier, has been relatively smooth. Following Navy’s inability to supply vessels requested by the then Government to assist in the clean-up after Cyclone Yasi in 201117, Navy required Product Schedule updates to be approved at higher management levels, and included additional financial and maintenance detail in the documents. Navy’s management of MSAs demonstrated a relatively conservative risk appetite, reflecting its assessment of risk, and resulted in a higher number of Product Schedule changes and delays in approving them. An unintended consequence of Navy’s approach was the emergence of undocumented workarounds to overcome delays in processing Product Schedule changes. While a matter for Navy’s senior leadership, there is scope to review the change management process for Navy Product Schedules and their level of detail.

21. The MSA framework recognises the importance of risk management in sustaining specialist military equipment, and provides a structured process for the identification, assessment and management of sustainment risks by the Services and the DMO. The ANAO’s examination of Defence’s management of the ANZAC, Orion and Bushmaster fleets indicated that senior leadership was kept up-to-date about the risks to the relevant capabilities, and that risk mitigation strategies were generally in place. However, the practical effectiveness of the MSA framework largely depends on active and timely management of identified risks by Capability Managers and the DMO, and in that respect, a robust MSA framework is an aid to management, not an end in itself.18

Sustainment Funding and Cost Estimates (Chapter 4)

22. The DMO’s acquisition and sustainment activities are presented as separate programs in the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS), and the 2006 Defence–DMO Memorandum of Arrangements documents certain constraints on the transfer of funds within the DMO between acquisition and sustainment activities. However, while the PBS suggests that a relatively clear-cut distinction exists between acquisition and sustainment activities and funding, that distinction is not as clear-cut in the Memorandum of Arrangements, and experience indicates that the distinction is not hard and fast in practice. While acknowledging that there can be a period of transition between the acquisition and sustainment phases of a capability, the ANAO noted a number of instances of overlap in the use of acquisition and sustainment funding.19 To clarify the internal treatment of acquisition and sustainment funding, Defence should review relevant business rules and guidance.

23. From the establishment of the DMO as a prescribed agency20 in 2005, control of sustainment funding rested with the CEO DMO, who was able to move funding between sustainment products as needs and priorities changed. Some years ago, Capability Managers were given renewed responsibility for controlling their sustainment budgets. Under this arrangement, transfers of funding between sustainment products can occur with the agreement of the relevant Capability Manager. The number of funding transfers increased from seven in 2011–12 to 55 in 2013–14, and the total value of these transfers across financial years increased from $170 million to $1.1 billion. Capability Managers informed the ANAO that they valued the ability to flexibly use sustainment resources according to operational and maintenance needs.

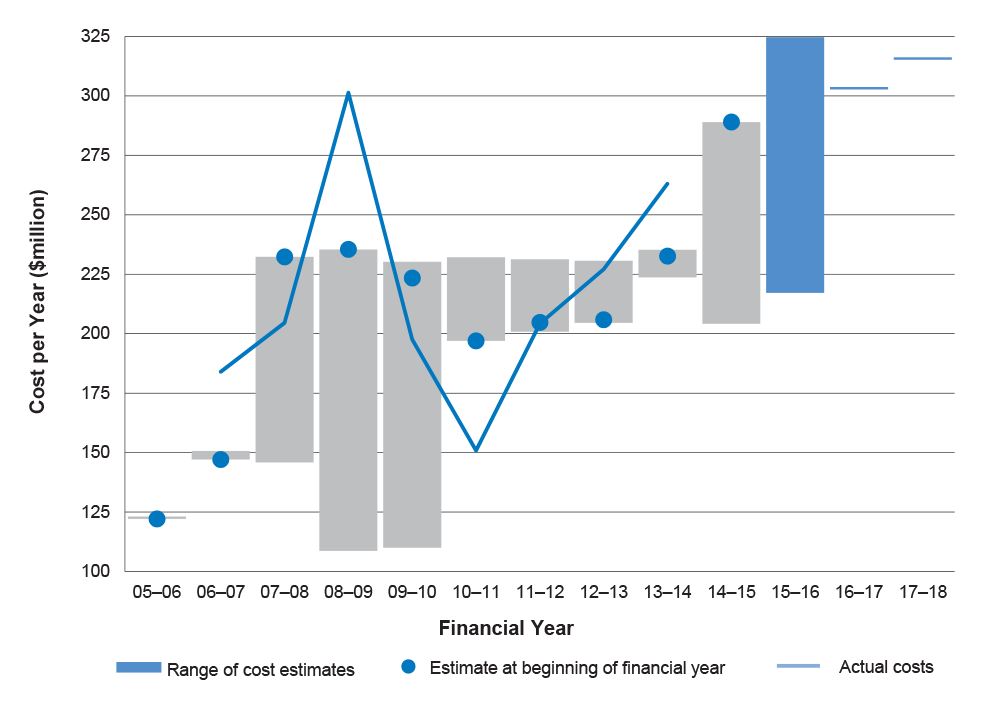

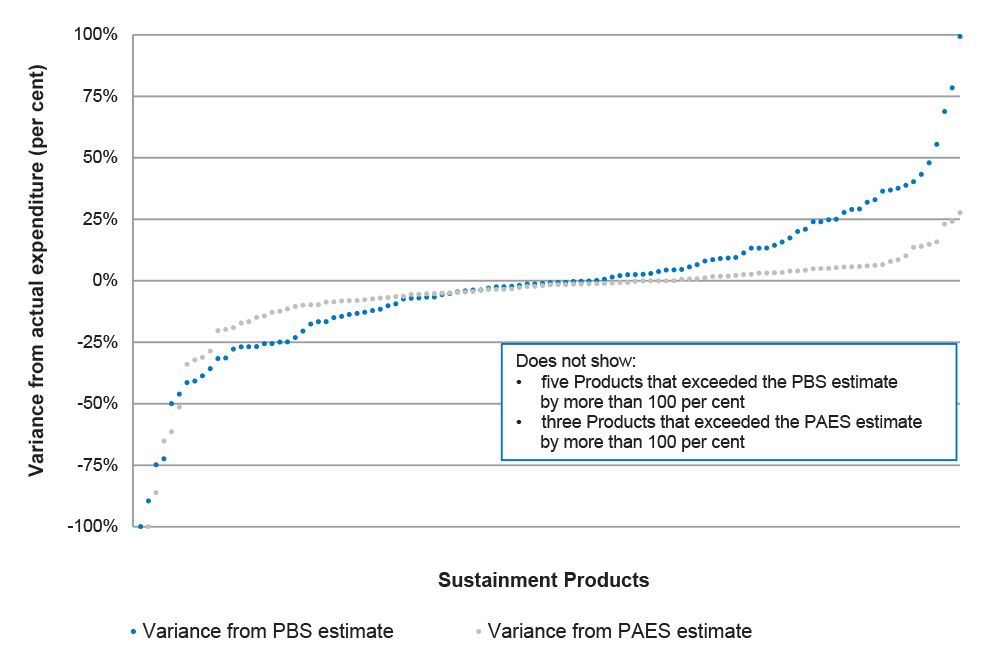

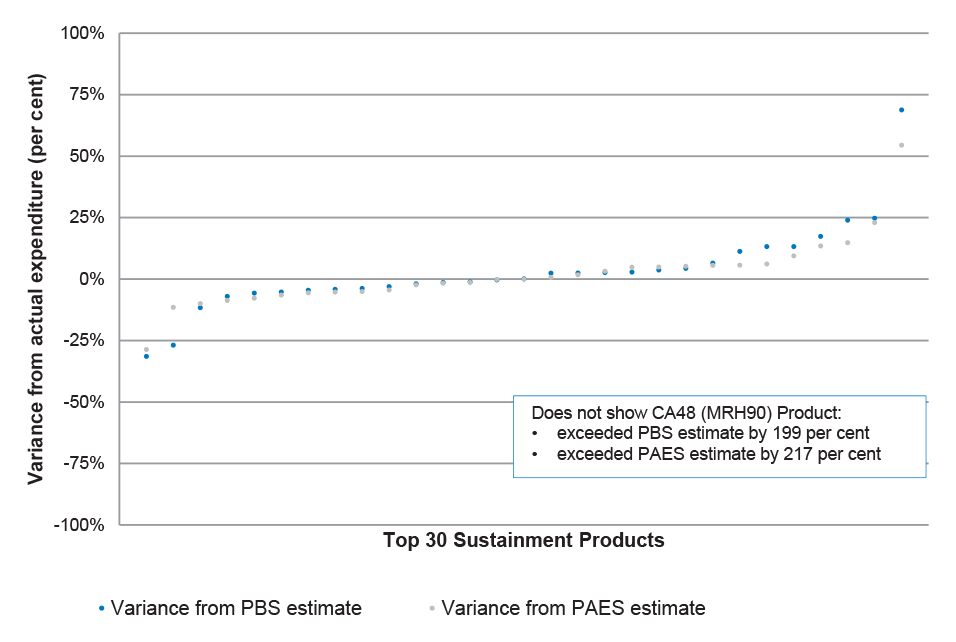

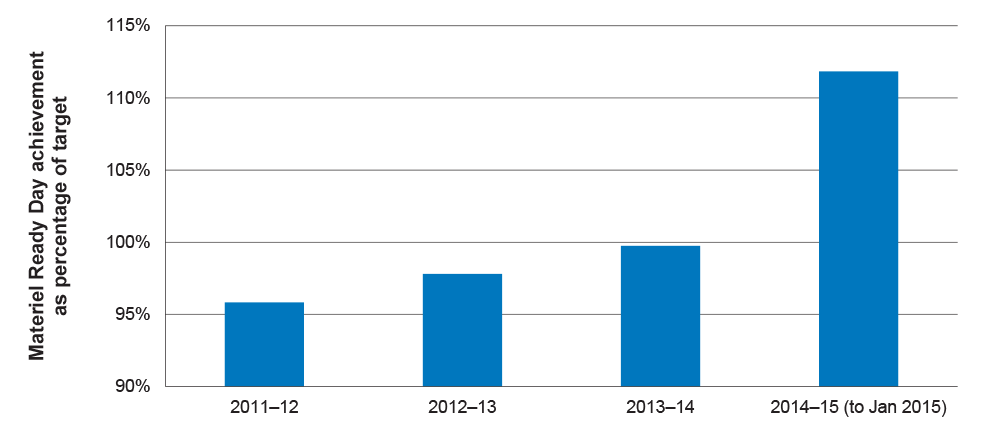

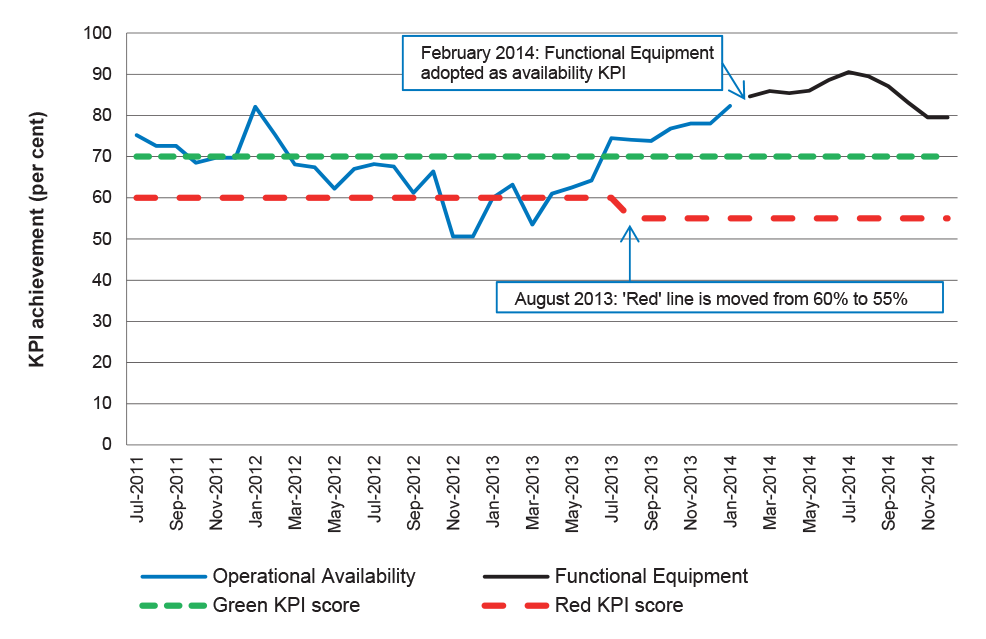

24. The three case studies examined by the ANAO indicated that there have been persistent inaccuracies in Defence’s sustainment cost estimates. Moreover, actual expenditure in 2013–14 for one third of all sustainment products (39 out of 118) varied from the budget estimate by over 25 per cent. Some departure from budget estimates can be expected due to flexible use of funding between sustainment products, and unforeseen factors such as the need to delay or bring forward maintenance work due to operational demands. However, variances of over 25 per cent are significant and suggest that there remains scope for the DMO to strengthen cost estimation techniques and understanding of cost variances. Improved cost estimation would strengthen the capacity of Defence’s Capability Managers to flexibly manage sustainment funding as informed purchasers of sustainment services.

Performance and Reporting (Chapter 5)

25. The 2008 Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review (the Mortimer Review) considered that sustainment performance would not improve unless it was measured, and reported that Defence did not have appropriate, quantifiable KPIs.21 In 2012, the DMO developed a sustainment performance measurement framework and commenced work on a new reporting system. In 2013 and 2014 Navy and Army developed revised sustainment performance measures which will be reported through the DMO reporting system. These include a suite of Navy KPIs and Key Health Indicators that assess sustainment performance and the state of each capability.22 However, the first stage of the rollout of the DMO’s new reporting system has been delayed from November 2014 until May 2015. It is only when the new measures have been reported for some time that their usefulness will be tested, and any need for refinement can be assessed.

26. Defence’s annual reporting on sustainment includes budget and expenditure data for the Top 30 sustainment products (representing some 77 per cent of current spending on sustainment), as well as an overview of the management of these products. While providing stakeholders with a basic summary of sustainment costs and activity, this information does not facilitate assessment of Defence and the DMO’s sustainment performance in terms of materiel availability, cost-effectiveness and key inputs such as inventory management, maintenance and configuration changes. Defence still has some way to go before it meets the intent of the recommendation of the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade for enhanced public reporting. Following a request by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), in February 2015 the ANAO provided the JCPAA with options, developed in consultation with Defence, to enhance sustainment reporting to the Government and Parliament. The issue remains under consideration by the JCPAA at the time of preparation of this report.

Summary of entity response

27. Defence’s covering letter in response to the proposed audit report is reproduced at Appendix 1. Defence’s summary response to the proposed audit report is set out below:

Defence thanks the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) for conducting the performance audit: Materiel Sustainment Agreements. The audit was conducted and completed in a positive and collegiate manner, with the ANAO and Defence staff working together to analyse performance of the selected Materiel Sustainment Agreements.

Defence is committed to the review of procedures around Materiel Sustainment Agreements and the internal treatment of acquisition and sustainment funding as noted in the recommendations. After the outcomes are known from the First Principles Review, Defence will be better positioned to meet the intent of, and implement, the recommendations from the report.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 3.64 |

The ANAO recommends that Navy and the DMO review change management processes for Navy Product Schedules, and the level of detail in the Schedules, to support more flexible management of the Navy Materiel Sustainment Agreement. Defence response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Para 4.14 |

To clarify the internal treatment of acquisition and sustainment funding, the ANAO recommends that Defence review relevant business rules and guidance. Defence response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter introduces the concept of sustainment and Materiel Sustainment Agreements. It also sets out the audit’s objective and scope.

Background

1.1 Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) have been used since 2005 as customer–supplier agreements formalising the relationship between the Department of Defence (Defence) and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO)23 for the sustainment of specialist military equipment.24 Through the agreements, the Defence Capability Manager25 undertakes to supply funding, and the DMO undertakes the sustainment of specific platforms (such as a ship or aircraft fleet), commodities (such as clothing or combat rations) and services (such as provision of maritime target ranges). Sustainment involves the provision of in-service support, including repair and maintenance, engineering, supplies, configuration management and disposal action. Effective sustainment of ships, aircraft and vehicles is necessary to maintain the preparedness of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and enable the conduct of Defence operations.

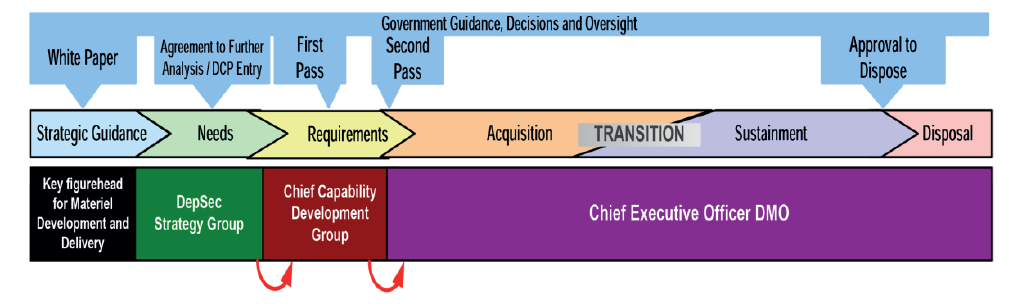

1.2 In 2014–15, out of total funding of $35.781 billion, Defence budgeted $7.109 billion, or 20 per cent, for its Capability Sustainment Programme, with most of this funding transferred to the DMO, which either directly or indirectly provides the majority of Defence sustainment services.26 The specialist military equipment being sustained was valued at $41.270 billion in 2013–14.27

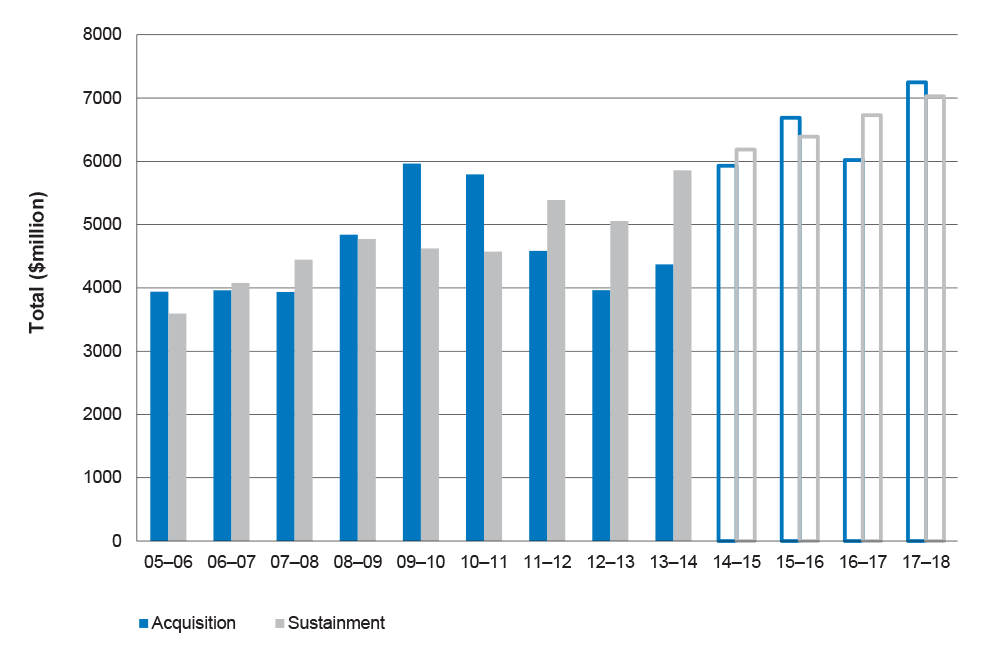

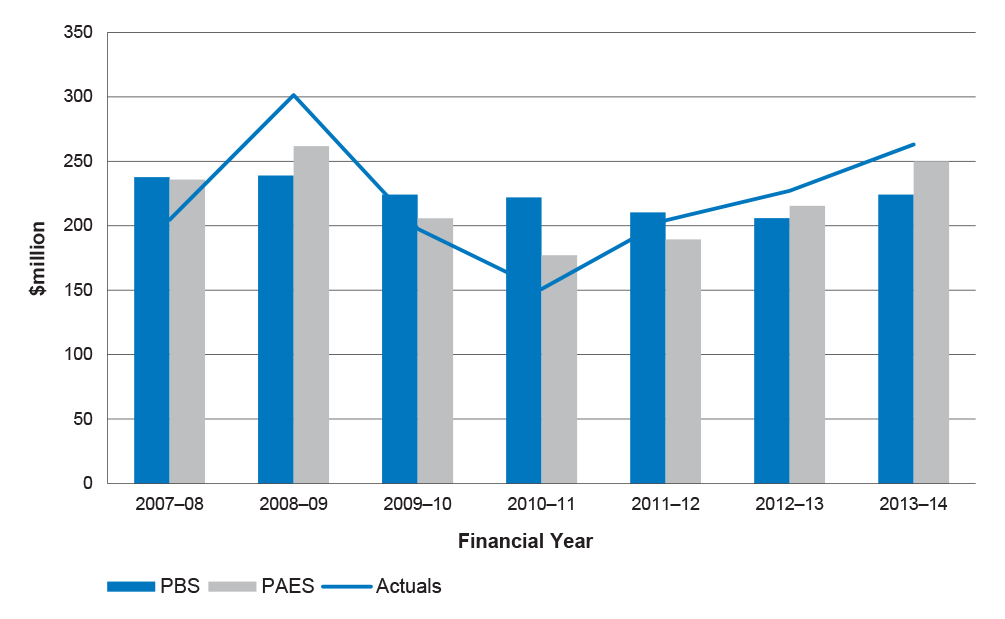

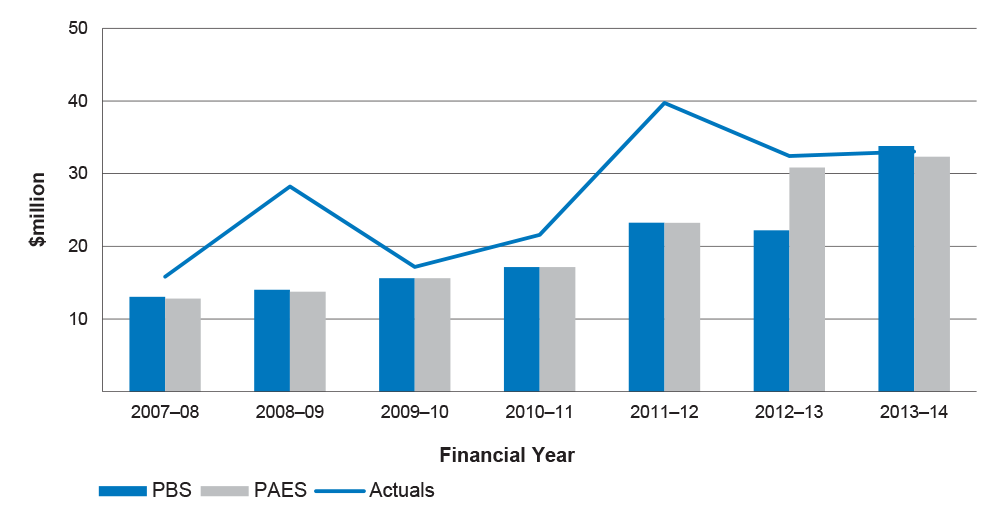

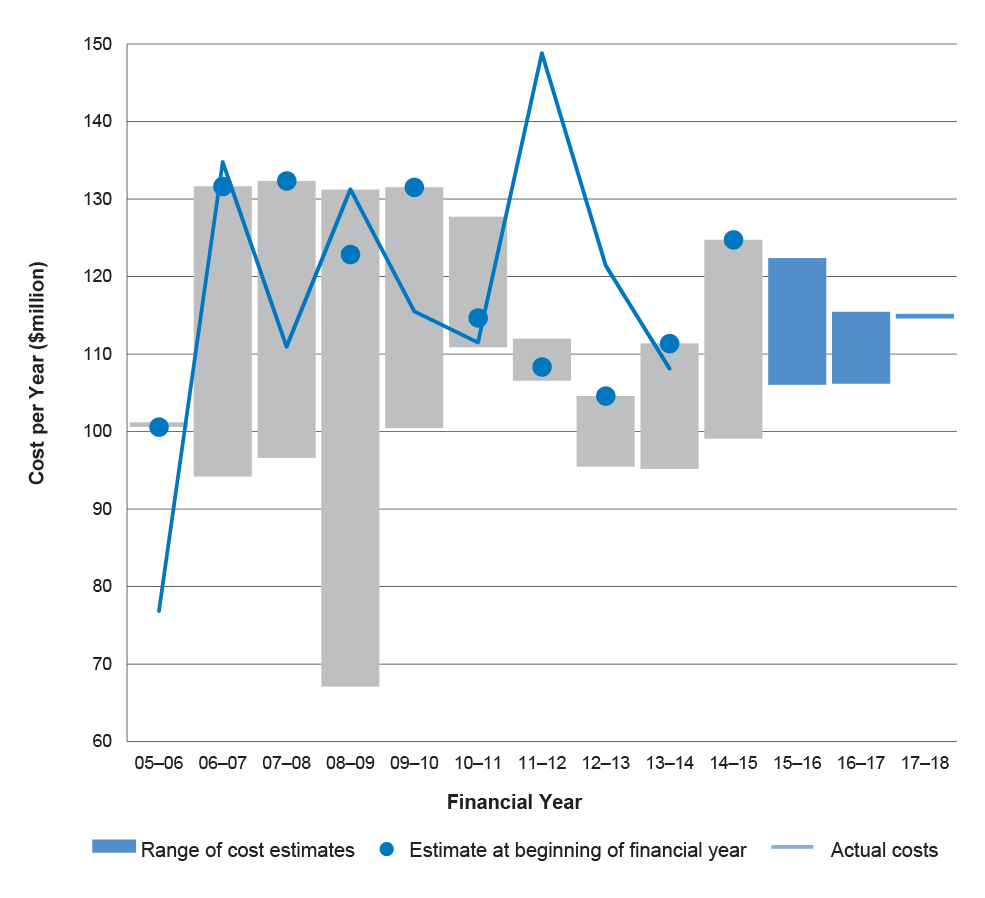

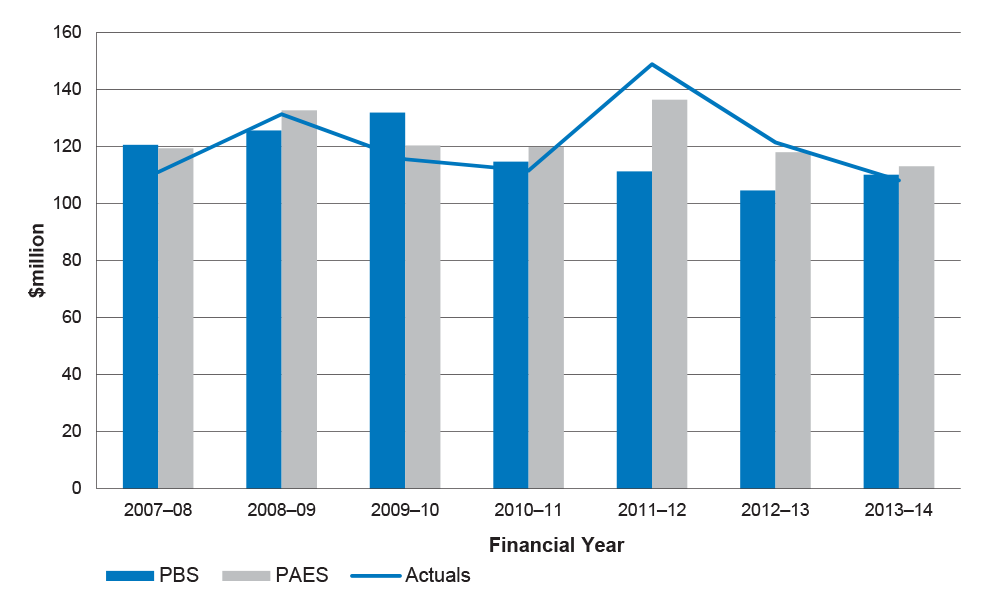

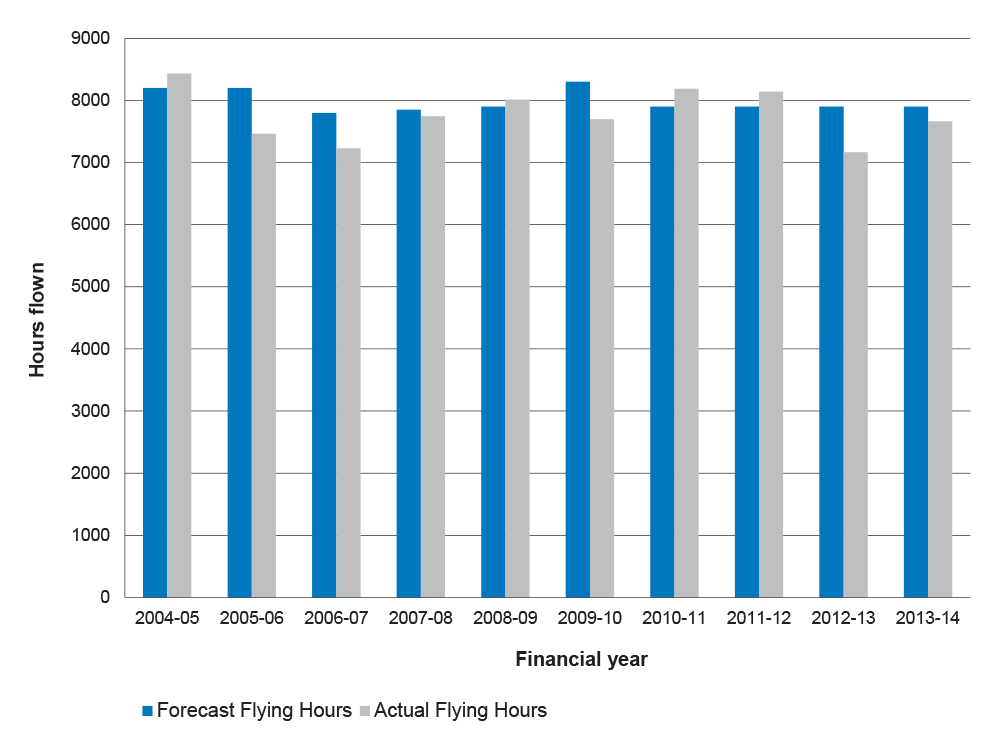

1.3 The DMO budget for 2014–15 comprises two major elements: $5.931 billion for acquisition projects, and $6.185 billion for its sustainment program. Figure 1.1 shows the DMO’s acquisition and sustainment expenditure between 2005–06 and 2013–14, as well as budgeted amounts for 2014–15 and the forward estimates. In five of the last nine financial years, sustainment expenditure exceeded acquisition expenditure, and budgeted sustainment expenditure for 2014–15 is at a record high level.

Figure 1.1: DMO acquisition and sustainment expenditure, 2005–14, and budgeted amounts for 2014–18

Source: ANAO analysis of expenditure and forward estimates for DMO Programme 1.1, Management of Capability Acquisition, and DMO Programme 1.2, Management of Capability Sustainment, in Defence Annual Reports and Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2014–15.

Note: The hollow columns represent the February 2015 Additional Estimates figures for 2014–15 and future years.

1.4 Sustainment activities are generally administered by the DMO’s Systems Program Offices (SPOs) and in particular through the Product Manager. The SPO serves as the single point of contact with industry, government entities, and other entities participating in the acquisition or sustainment of specialist military equipment. Generally, each major platform—such as an aircraft type or a class of ship (for example, F/A-18 Hornet aircraft, or the ANZAC Class frigates)—is managed by a single SPO, which may also manage the delivery of a commodity or service. On the customer side, a Capability Manager Representative liaises with the DMO on behalf of the relevant Defence Group or Service.

Managing Defence’s sustainment function

1.5 The Australian Defence Organisation comprises the Department of Defence, the ADF and the DMO. The successful provision of Defence capability depends on the Defence Organisation as a whole collaborating effectively and the component parts meeting their respective functional responsibilities, including, for the DMO, acquisition and sustainment responsibilities.

1.6 The then Minister for Defence approved the establishment of the DMO on 22 June 2000, through the amalgamation of the Department of Defence’s Defence Acquisition Organisation, Support Command Australia and part of its National Support Division. The objective of the amalgamation was to improve the delivery of equipment, systems and related goods and services to the ADF by integrating acquisition and through-life support into a whole-of-life capability management system. The DMO came into being on 1 July 2000, and related structural and organisational changes were made by December 2000.28

1.7 In September 2003, when the then Government approved the DMO’s transition to a prescribed agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), the intent was for the DMO to be more performance-oriented and business-like, so as to improve procurement and support practices, and establish a more transparent relationship between Defence and the DMO.29 The DMO became a prescribed agency under the FMA Act on 1 July 2005, with a separate Chief Executive Officer, financial accounts and annual reporting requirements, but staff provided by the wider Defence Organisation.30

1.8 The DMO’s February 2004 Business Model noted the primacy of Defence as the customer, with responsibility for setting requirements and determining priorities within agreed funding levels; and that the DMO would be funded and managed on the basis of agency agreements for the services it delivered. The agency agreements were to facilitate funding flows and delineate responsibilities and accountability between Defence and the DMO, and provide better visibility of the costs of procuring and sustaining Defence assets. The agreements were to be refined and improved over several annual cycles.

1.9 Agreements between Defence and the DMO are not legally binding, because both organisations are part of the same legal entity, the Commonwealth of Australia.31 Defence and the DMO have an overarching Memorandum of Arrangements for customer–supplier agreements that establishes the framework for their other bilateral agreements. The Memorandum of Arrangements outlines commitments that both parties agree to meet, in order to procure and sustain materiel for Defence.

1.10 Underneath the Memorandum of Arrangements, Defence and the DMO have entered into contract-like agreements for the provision of sustainment services:

Materiel Sustainment Agreements are between the Capability Managers and the Chief Executive Officer of the Defence Materiel Organisation. These agreements cover the sustainment of current capability, including goods and services such as repairs, maintenance, fuel and explosive ordnance.32

1.11 Each Materiel Sustainment Agreement (MSA) sets out the level of performance and support required by Defence from the DMO, within an agreed price, as well as the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) by which service delivery will be measured. MSAs comprise a Heads of Agreement and Product Schedules for different platforms, commodities and services. Since 2012, the previous practice of complete annual revision of the MSAs has been replaced by partial revision as needed, particularly of the financial sections of Product Schedules. The content of the Heads of Agreement and Product Schedules is examined in Chapter 2.

1.12 As previously mentioned, the 2014–15 budget for DMO Programme 1.2, Management of Capability Sustainment, amounts to $6.185 billion33, of which some $5.683 billion is to be expended through seven MSAs incorporating 116 Product Schedules (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Materiel Sustainment Agreements and Product Schedules, as at February 2015

|

Capability Manager |

Number of Product Schedules |

Value of Services ($million) |

|

Chief of Navy |

36 |

1975.720 |

|

Chief of Air Force |

28 |

1975.889 |

|

Chief of Army |

45 |

1503.562 |

|

Chief Information Officer |

4 |

76.728 |

|

Joint Health Command |

1 |

45.941 |

|

Strategy Executive |

1 |

20.908 |

|

Joint Operations Command |

1 |

5.789 |

|

Not assigned to products |

|

78.416 |

|

Total |

116 |

5683.953 |

Source: DMO, MSA Product Budgets as at February 2015.

Note: Includes baseline funding, operations funding ($315 million) and expected Net Personnel and Operating Costs ($85 million).

Audit objective and scope

1.13 The audit objective was to examine Defence’s administration of Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) and the contribution made by MSAs to the effective sustainment of specialist military equipment.

1.14 Four high-level criteria were developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s administration of MSAs:

- MSAs constitute an effective arrangement formalising the relationship between Defence Services/Groups and the DMO for sustainment activities.

- MSA Product Schedules clearly identify costs, deliverables, and appropriate KPIs.

- Risks, issues and constraints to achieving effective sustainment are identified in MSA Product Schedules, and appropriate management strategies are in place.

- Monitoring and reporting processes provide relevant and reliable information on sustainment activities.

1.15 The ANAO examined Defence’s MSA policy, procedures and systems, including reforms in these areas. The ANAO also examined Defence’s management of three Product Schedules. One Product Schedule was selected for each of the Navy, Army and Air Force:

- Navy’s FFH ANZAC frigates (Product Schedule CN0234), as one of the first MSA Product Schedules to be revised after the Rizzo Report35;

- Army’s Protected Mobility Vehicle (Bushmaster) fleet (Product Schedule CA04), which has been heavily used in Iraq and Afghanistan; and

- Air Force’s AP-3C Orion fleet (Product Schedule CAF04), which was heavily involved in the search for Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 in the Indian Ocean.

1.16 Assessing the overall effectiveness of the Product Schedules and their oversight involved engagement with: DMO staff responsible for the drafting and oversight of the Product Schedules; the project teams that carry out the sustainment of the selected military equipment; and staff assisting the relevant Capability Managers.

1.17 The 2010 ANAO performance audit on Effective Cross-Agency Agreements provided better-practice principles to assist in evaluating the MSAs, including discussion of consistency and clarity, guidelines, key provisions (such as achievable performance measures), and effective monitoring and review processes.36

1.18 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards, at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $493 000.

Structure of this Audit Report

1.19 The remainder of the Audit Report is arranged as follows:

Table 1.2: Structure of this Audit Report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Materiel Sustainment Agreements |

Provides an overview of the Defence–DMO agency agreements framework. It then examines the structure and content of MSAs, and the reforms of the MSA framework that have been implemented in recent years. |

|

3. Materiel Sustainment Agreements in Operation |

Examines management reviews of MSAs, the change management process for Product Schedules, and the management of sustainment issues and risks. |

|

4. Sustainment Funding and Cost Estimates |

Examines Defence’s sustainment funding arrangements, and cost estimates for individual Product Schedules. |

|

5. Performance and Reporting |

Examines internal and external sustainment performance reporting, including KPIs. |

2. Materiel Sustainment Agreements

Provides an overview of the Defence–DMO agency agreements framework. It then examines the structure and content of MSAs, and the reforms of the MSA framework that have been implemented in recent years.

Introduction

2.1 Common drivers for formalising cross-entity arrangements include the need or desire to: promote a collaborative relationship between parties and demonstrate a commitment to joint work; establish a degree of control or assurance in relation to the activities or responsibility of another party; enhance accountability, transparency and efficiency; improve knowledge; and provide better services.37

2.2 In September 2008, the report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review (the Mortimer Review) found that ‘the MSAs are a workable mechanism for Capability Managers and DMO to use’. The review also found that ‘the intent for DMO to become more business-like is not yet adequately reflected in a mature customer-supplier relationship between Defence and DMO’. The review concluded that the DMO needed to focus on being a business-like supplier of products and services rather than trying to accommodate all that was asked, and Capability Managers needed to become more informed customers.38

2.3 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- the Defence–DMO agency agreements framework;

- recent reforms of the MSA framework; and

- the structure and content of MSAs.

Defence–DMO agency agreements framework

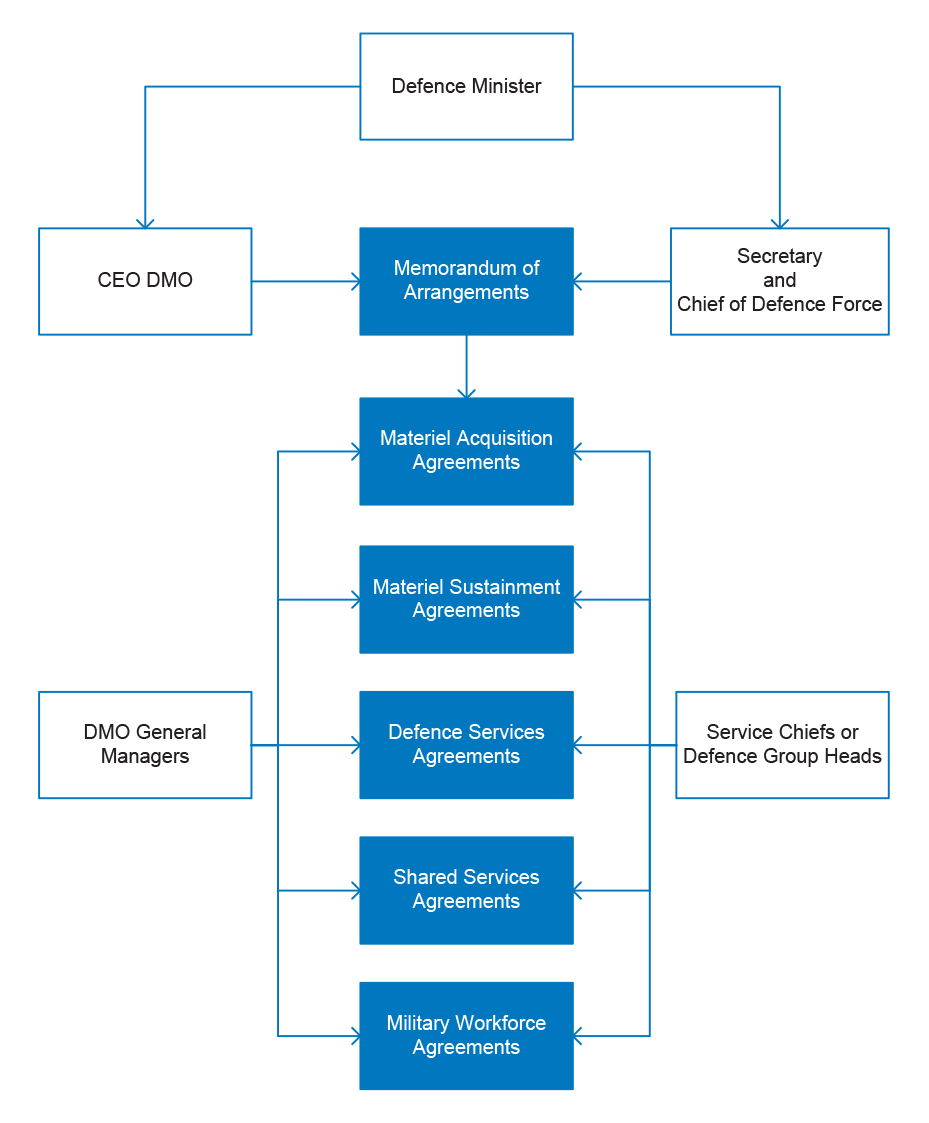

2.4 A map of the formal relationships between Defence and the DMO, as mediated through an agency agreements framework, is shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Defence–DMO agency agreements framework

Source: DMO, Agreements Manual (draft as at January 2013), Chapter 2, p. 5.

2.5 Under the framework, an overarching Memorandum of Arrangements provides for five types of agency agreement between Defence and the DMO:

- Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs);

- Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs);

- Defence Services Agreements;

- Shared Services Agreements, covering services such as payroll, accommodation and banking services provided by Defence, and contracting policy and advice provided by the DMO; and

- Military Workforce Agreements, for posting of military personnel to the DMO.39

2.6 Defence and the DMO entered into the Memorandum of Arrangements for Customer–Supplier Agreements on 15 June 2005, and it was last revised on 30 June 2006.40 Under the Memorandum of Arrangements, in relation to sustainment:

- Defence is responsible for setting clear performance requirements and priorities for products and services, and preparing government submissions for additional funding; and

- the DMO is responsible for delivering the outputs agreed with Defence in the MSAs, controlling all resources, staffing and other inputs, providing appropriate evaluation and reporting, and setting policy instructions and governance arrangements for financial management of its funding and appropriations.

2.7 The Memorandum of Arrangements specifies that MSAs shall:

- include individual schedules identifying the price and deliverables for each sustainment product;

- separately identify baseline, supplemented and operations sustainment provided by the DMO to Defence41;

- provide a budget forecast for the following 10 years; and

- be renegotiated annually in conjunction with Defence’s financial planning process, known as the Defence Management and Financial Plan (DMFP).

2.8 In May 2009, in response to the Mortimer Review, the then Government formally committed to updating the Memorandum of Arrangements to clarify the respective authorities and responsibilities of Defence and the DMO.42 However, this has not yet occurred, and in respect of MSAs, the Memorandum of Arrangements has become increasingly obsolete. The outdated elements include:

- the requirement for annual renegotiation of MSAs—this requirement has been overridden by a subordinate document, the 2012 DMO Standard Procedure on MSAs;

- the discretion of the CEO DMO to move funds within the acquisition and sustainment areas—this discretion was restored to Defence Capability Managers some years ago;

- a reference to the DMO Service Fee—which has not existed since

2009–10, when the DMO began to receive its own appropriation for workforce and operating expenses; and - Product Schedules—the list of Product Schedules in the Memorandum of Arrangements is nine years out-of-date.43

2.9 The DMO has attempted to update the Memorandum of Arrangements on many occasions, and prepared an updated document for approval: between 2007 and 2009; in 2011 and 2012; and again in 2013. However, on each occasion, momentum was lost and the revised Memorandum was not formally approved, reflecting difficulty in reaching agreement across a large number of Defence stakeholders.

2.10 The long delay in updating the Memorandum of Arrangements—which is the capstone of Defence’s agency agreements framework—has resulted in a subordinate document, the DMO Standard Procedure on MSAs, now filling a policy gap. That document has increasingly been relied on as the Defence policy and procedure for sustainment activities.

2.11 While the Defence Organisation has shown a capacity to adapt, the DMO Standard Procedure is not mandatory policy for any of the Services, and the DMO relies on the Services’ ongoing commitment to the Standard Procedure to help bring coherence to sustainment arrangements. In contrast, an updated Memorandum of Arrangements would achieve an authoritative and ongoing basis for MSA policy and procedure across Defence Groups and Services.

2.12 Defence informed the ANAO in December 2014 that it was likely to experience organisational change flowing from internal and external reviews, including the First Principles Review44, and as a consequence it would be imprudent to update the Memorandum of Arrangements at this time. Defence further informed the ANAO that once the changes flowing from reviews are confirmed, Defence will shape an appropriate solution at the earliest possible opportunity.

Structure and content of Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs)

2.13 As indicated in Figure 2.1, MSAs sit underneath the Memorandum of Arrangements in the Defence–DMO agency agreements framework. The first level of the MSA is the Heads of Agreement, which is an overarching document that covers a series of Product Schedules. The Heads of Agreement contain the high-level framework establishing the partnership between each Capability Manager and the DMO. Heads of Agreement are developed following a common template and can be tailored to the requirements of each Capability Manager. The main features of the Heads of Agreement template are set out in the text-box on page 4.

|

The Heads of Agreement template includes the following features:

|

Source: DMO, Materiel Sustainment Agreement Heads of Agreement Template, November 2012.

2.14 The second level of each MSA is the Product Schedules, a list of which is attached to the Heads of Agreement. Each Product Schedule deals with the sustainment of a specific platform, commodity or service for the relevant Defence Service or Group. In February 2015, the seven Heads of Agreement incorporated 116 Product Schedules. The number of Product Schedules for each Capability Manager is shown in Table 1.1.45

2.15 Product Schedules are where the specific sustainment requirements for each capability are found. The Product Schedule defines: the supplies and services that will be provided by the DMO; the budget that is provided by the Capability Manager; and standards for matters such as responsiveness, availability levels, and maintenance timeframes.

2.16 In 2013, the Product Schedules represented a significant body of paperwork, amounting to some 2600 pages for Navy, 1150 pages for Army, and 850 pages for Air Force. Since they are among the top planning documents for the expenditure of over $6 billion46, it is important to maintain a balance between statements of principle and the level of detail in these documents.

2.17 The standard structure of the Product Schedules for all the Capability Managers (except Navy) is shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Structure of non-Navy Product Schedules

|

Module/Annex Title(a) |

Description |

|

A: Product Description |

Provides details of the product being supported, e.g. fleet/inventory size, variants. |

|

B: Capability Requirements and Performance Indicators |

Details performance outcomes sought, and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). |

|

C: Finance |

Presents a price for services in the current and forward years, forecast monthly expenditure for the current financial year, operations funding, a statement on unfunded sustainment activities, and Strategic Reform Program (SRP)(b) savings targets. |

|

D: Functions, Roles and Responsibilities |

Sets out the functions, roles and responsibilities of the SPO, Lead Capability Manager, Supported Capability Manager, the End User, and those that are shared. |

|

E: Issues, Risks and Constraints |

Details issues affecting the Product, risks that may arise, and constraints that may limit effective sustainment. |

|

F: Product Schedule Endorsement Delegations |

Sets out the levels of delegation for amending the Product Schedule. |

|

G: Reform and Continuous Improvement (optional) |

When used, details reforms that will be undertaken and who will have responsibility for them. |

|

H: Inter-dependent Product Schedules (optional) |

When used, lists the associated Product Schedules that support the Product. |

Source: DMO, Management of Materiel Sustainment Agreements including Product Schedules Standard Procedure, 6 November 2012, p. 4.

- Army uses the term Module, and Air Force uses the term Annex, for the different parts of the Product Schedule.

- On 2 May 2009 the then Government launched both the 2009 Defence White Paper and the SRP. Defence expected the SRP to improve accountability, planning and productivity and deliver savings of $20 billion over the decade 2009–10 to 2018–19, including $5.1 billion in sustainment savings through Smart Sustainment reform.

2.18 Navy Product Schedules are structured differently and are considerably longer than those of Army and Air Force. Their structure is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Structure of Navy Product Schedules

|

Section Title |

Description |

|

1: Requirement |

Outlines the nature of the capability, and Government and Navy requirements. Provides a list of the items (such as ships or facilities) that are being sustained. |

|

2: Exceptions |

Provides a framework for dealing with limitations on the DMO’s ability to deliver the required capability, and other circumstances that affect delivery of the capability. |

|

3: Statement of Work |

Contains a list of matters covered by the statement of work (Annex F). |

|

4: Performance and Reporting |

Details the theory behind KPIs and Key Health Indicators (KHIs), and the reporting framework to be used. |

|

5: Constraints on Supply Variation |

Outlines factors that influence the DMO’s ability to vary performance in response to adjustments sought by Navy. |

|

6: Delegations and Authorities |

Outlines the responsibilities of the lead Navy and DMO personnel (the Capability Manager Representative and the SPO Director), and the levels of delegation for amending the Product Schedule, including financial values at which delegations may be exercised. |

|

7: Financial |

Presents a whole-of-life cost plan, approved sustainment funding and forecast monthly expenditure for the current financial year (all with detailed breakdowns into line-items). Also includes a statement on unfunded sustainment, and tied funding support to operations. |

|

Annexes |

Description |

|

A: Product Operating Profile |

Details the purpose and various aspects of the use of the product. |

|

B: Product Activity Plan |

Presents planned Materiel Ready Days and scheduled maintenance periods for the years ahead. |

|

C: Fleet Support Unit Capability and Capacity |

Details the requirement for the DMO to offer maintenance work to the Navy’s Fleet Support Units in order to build up Navy capability. |

|

D: Approved Capability Improvement, Sustainment and Retirement Initiatives |

Lists the capital equipment acquisition projects associated with improving the capability, engineering changes addressing safety and/or supportability issues, and projects associated with capability retirement. |

|

E: Accepted Materiel Capability Limitations and Risks |

Lists the issues and limitations that Navy and the DMO recognise, and the risks that the SPO has identified, as having the potential to limit successful achievement of outcomes. |

|

F: Statement of Work |

States in detail the obligations upon the DMO and Navy in delivering the Product. |

|

G: Key Performance and Health Indicators |

Presents the KPIs and KHIs. |

|

H: Product Schedules Supporting the Product |

Lists the associated Product Schedules that support the product. |

|

I: Transition |

Provides detail of actions that are in progress at the time of drafting the Product Schedule, or are yet to be undertaken. |

|

J: Acronyms and Glossary |

Not always used. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the ANZAC fleet Product Schedule as at July 2014, which was one of the models for subsequent Navy Product Schedules.

2.19 The nature of the products being sustained under the MSA framework is such that there is not necessarily a one-to-one relationship between a product and a Defence Service or Group, and a product may have relationships with other products. For example, the Bushmaster fleet, primarily ‘belonging’ to Army, has a small component of vehicles that are used by Air Force. Similarly, while the Bushmaster fleet is primarily sustained through Army’s CA04 Product Schedule, it could not operate without the fuel and lubricants supplied under another Product Schedule.47

2.20 In 2011, the three Services signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to provide clear guidance on Capability Manager roles and responsibilities where there are multiple users of a product. In effect, the Capability Manager who is the major user of a capability takes on the Lead Capability Manager role for the Product Schedule, and coordinates other Service or Group requirements.48

ANAO assessment of MSA quality

2.21 Key success factors for cross-entity arrangements include: clear roles, responsibilities and governance arrangements; a shared objective or outcome; clear funding arrangements; management of shared risks; and coordinated reporting and evaluation, with a clear focus on the shared objective as well as entity contributions.49

2.22 Table 2.3 considers the extent to which the three Services’ MSAs (comprising both the Heads of Agreement and Product Schedules) have regard to better practice in agreement-making.

Table 2.3: ANAO assessment of MSA quality

|

Characteristic |

Navy |

Army |

Air Force |

|

Clearly written – avoids legalistic language |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Concise – only contains essential information |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Appropriate overarching authority for agreement |

No |

No |

No |

|

Shared objective or outcome |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Deliverables explicitly defined |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Clear roles and responsibilities for both parties |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Balanced performance indicators on both parties |

No |

No |

No |

|

Performance reporting and monitoring framework |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Sufficient financial detail for informed oversight |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Issues and risks documented |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Bilateral governance and review arrangements |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Dispute resolution procedures |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Effective method of variation |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: ANAO analysis of a random sample of six Product Schedules from each Service, based on criteria in ANAO Audit Report No.41 2009–10, Effective Cross-Agency Agreements, p. 54.

2.23 For the most part, the MSAs examined met the key characteristics of cross-entity agreements. The MSAs outline governance arrangements, respective roles and responsibilities, sustainment deliverables, performance reporting and monitoring arrangements, sustainment issues and risks, and dispute resolution procedures. These features of the MSAs serve to clarify accountabilities, coordination arrangements and relevant processes.

2.24 Some features of existing MSAs indicate scope for improvement in the MSAs. For example:

- Each of the MSAs refers to the Memorandum of Arrangements as the overarching document that authorises the MSAs. However, as discussed in the early part of this chapter, the Memorandum of Arrangements is increasingly out-of-date, and in practice it has been bypassed by the DMO Standard Procedure on MSAs.

- The establishment of shared objectives or outcomes as part of a cross-entity agreement assists in furthering individual entity outcomes, while focusing each entity on the overall intent and expected outcomes of the cross-entity initiative. The Navy MSA outlines its purpose and objectives, and supporting principles, whereas the other Services’ MSAs do not.50

- While a bilateral agreement will generally include reciprocal KPIs which recognise that one entity’s ability to perform work often depends on timely action by the partner entity51, there is a tendency for MSA Product Schedules to include performance measures related to only one party—the DMO. More generally, the DMO, Navy and Army have developed new sustainment performance measurement frameworks which are yet to be fully implemented.

- The Army and Air Force MSAs have workable change mechanisms that allow them to be kept reasonably current. Navy has experienced a greater administrative burden in establishing change mechanisms and keeping the documents current. This is a result of both the higher level of detail present in the Navy MSA (resulting in more frequent changes), and Navy’s requirement for changes to be approved at higher levels than required by Air Force and Army (resulting in slower changes).

Reform of the MSA framework

2.25 The MSA framework was introduced in 2005 and has continued to evolve. A 2012–13 Lean Project 52 represented a significant turning-point in the design and administration of the MSA framework.

2012–13 Lean Project

2.26 In February 2012, the DMO informed the Services that it had initiated an MSA Lean Project ‘to improve the MSA and MSA change proposal (MSACP) processes to make them straight-forward, easy to use, faster and more flexible.’ By June 2012, the DMO had conducted the initial, data-gathering phase of the Lean Project, and reported that:

Overall, stakeholders reported that the MSA process was long and tedious with little apparent value-add. The process currently has too much emphasis on the approval process and too little on planning and performance management. The focus needs to be on delivering outcomes which are achievable within the funding available in order to obtain the best outcome for the money available. The initial workshop findings included:

- annual cycle to re-sign MSAs is not required and not supported;

- annual cycle is not adding value to the content of the MSAs;

- working level[53] stakeholders require more clarity of Capability Manager requirements earlier in the development process;

- roles and responsibilities in the process are not clear;

- ownership of the document is not clear;

- current content and KPIs are not used for product management at any level;

- loss of visibility of the MSAs after leaving the working level during the endorsement and signature process engenders lack of ownership of the final document; and

- reporting on products is already a large burden.

2.27 In July 2012, the DMO organised five days of workshops to develop a streamlined MSA process with the intent to release capacity to focus on sustainment planning, management and performance. The DMO described the overall outcome to Capability Managers as follows:

We all agree that the current MSA process is too cumbersome, bureaucratic and inflexible. The good news is that the team conducting the Lean activity believe that it is possible to replace the annual cycle of MSA development stretched over months with a change process of less than five days. To achieve this level of reform will require us, as senior leaders, to consistently back this initiative at all levels of our organisations.54

2.28 The workshops were the culmination of several years of attempts to develop an effective and uniform MSA policy and practice. Representatives of Defence Services and Groups reached a consensus on key reform initiatives, including:

- the Product Schedule being capability focused;

- all sections of the MSA and Product Schedule being enduring, with built-in performance review periods;

- a modularised Product Schedule template55;

- introducing Product Schedule delegations to enable greater delegation aligned to line management accountability; and

- simplified/accelerated workflows for changing/updating/introducing Product Schedule sections under the proposed delegation framework.

2.29 The broad implementation parameters from the workshop also included the need to redesign the MSA framework to focus on sustainment outcomes and information required by the O5/O6 level, and to make the Product Schedules more concise and focused on the changeable aspects under management.

The DMO issued a Standard Procedure on MSAs in 2012

2.30 In November 2012, following on from the Lean Project workshops, the DMO issued the Defence Materiel Standard Procedure entitled Management of Materiel Sustainment Agreements including Product Schedules Standard Procedure.56 The Standard Procedure addressed the key deliverables of the July 2012 workshops to develop a streamlined MSA framework. It sets out, essentially in four pages, the elements of the new approach to the MSA framework, and includes process flows for implementing scheduled financial decisions as well as other decisions.

2.31 The DMO asked Capability Managers to endorse the Standard Procedure as the ‘interim Defence and DMO policy’ for the management of MSAs, given the wide consultation involved in its development. This was seen as an expedient way of achieving Defence-wide commitment to the proposed MSA arrangements. Capability Managers endorsed the Standard Procedure before it was formally issued. The Standard Procedure included some exceptions from its requirements for Navy.

2.32 As a DMO policy, the Standard Procedure has no authority to direct the Services or other Defence Groups. It therefore explicitly states that it has been created ‘as an interim policy until a Defence Instruction (General) is considered by key stakeholders and released in early 2013.’57 However, in June 2013, Defence’s System of Defence Instructions (SODI) administrators advised the DMO that the creation of a Defence Instruction (General) for MSA policy was not appropriate because MSAs are non-legally binding, and they do not pertain to everyone in Defence.

2.33 By August 2014, it was agreed that the Standard Procedure would be updated, and Capability Manager Representatives would continue to acknowledge the Standard Procedure as the agreed MSA protocol between the DMO, Defence Groups and the Services. Further, the DMO would investigate the inclusion of an MSA chapter in a sustainment manual being written by its Standardisation Office.

Implementation of the new MSA framework

2.34 Work on implementing the new MSA framework continued until the formal closure of the Lean Project in April 2014. The biggest task involved the development of enduring Heads of Agreement and Product Schedules based on new templates. The revised documents and related governance and monitoring arrangements reflect an intention to eliminate rework and excessive review, and focus efforts on the higher-value areas of sustainment planning, management and performance. The transition of different MSAs and Product Schedules to the new model is shown in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Transition of MSAs to the new model, 2013–14

|

MSA |

New Heads of Agreement signed |

Last of new Product Schedules signed |

|

Air Force |

5 February 2013 |

19 August 2013 |

|

Army |

8 July 2013 |

20 September 2013 |

|

Chief Information Officer |

24 June 2013 |

13 August 2013 |

|

Joint Health Command |

25 October 2013 |

25 October 2013 |

|

Joint Operations Command |

Not yet signed |

Not yet signed |

|

Strategy Executive |

9 August 2013 |

9 August 2013 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence records.

Notes: Taking a different approach, Navy had signed a new enduring Heads of Agreement on 9 August 2012, and completed its Product Schedule transition by 30 June 2013. Navy signed a revised Heads of Agreement on 20 January 2015.

In a further round of revision, the Chief Information Officer Group and Army signed new Heads of Agreement with the DMO on 27 August 2014 and 3 September 2014 respectively.

As a result of the Rizzo Report, Navy took a different approach

2.35 While Navy representatives were involved in the DMO’s Lean Project, a different imperative drove the review and reform of the Navy–DMO MSA from 2011 onwards. In February 2011, Navy was unable to supply vessels requested by the then Government to assist in the clean-up after Cyclone Yasi. This was quickly followed by the early decommissioning of HMAS Manoora, the extended unavailability of HMAS Kanimbla and the temporary unavailability of HMAS Tobruk. These events resulted in the commissioning of the Rizzo Report.58

2.36 In July 2011, the Rizzo Report found that the events mentioned above were ‘reflective of on‐going systemic failure’, and made several observations pertaining to the then Navy MSA and its Product Schedules, namely that:

- the MSA was critical for accountability, but was ‘currently poorly defined and weak’;

- the KPIs in the Product Schedules were inadequate, with no consequences for non-compliance; and

- the MSA should be used by the DMO to clearly define the obligations of Navy.59

2.37 The Rizzo Report made two recommendations (out of 24) that directly related to MSAs:

Recommendation 11. Capture Mutual Obligations: The Navy MSA should be transformed into an active ‘contract’ that meaningfully captures the mutual obligations of Navy and DMO, supported by business-like performance measures.

Recommendation 12. More Effective Information Exchange: Navy and DMO must improve their internal reporting by capturing direct, timely and candid, document-based information that draws on a rigorous set of metrics.60

2.38 Navy took the Rizzo recommendation for a more contract-like MSA to mean one that contained: a customer–supplier arrangement; clearly defined responsibilities, obligations, performance measures and deliverables; delegations of authorities and responsibilities; and appropriate management and reporting arrangements.

2.39 The Chief of Navy signed a new MSA with the DMO on 9 August 2012.61 This was three months before the DMO issued its Standard Procedure and new templates, in November 2012. The new MSA included a restructure of the 36 Navy Product Schedules, which were rewritten in the post-Rizzo format and approved progressively by 30 June 2013 as part of the Rizzo Reform Program.

2.40 In response to Recommendations 11 and 12 of the Rizzo Report, the Navy–DMO Heads of Agreement includes a section on the core obligations of Navy and the DMO, and requires a traffic-light system for monthly reporting in relation to both availability and price. Further, Navy’s new Product Schedules include a Statement of Work and a detailed breakdown of funding into line-items. The funding line-items are intended to give Navy visibility of where funding, below product level, is being spent.

2.41 The Standard Procedure on MSAs only requires details of overall baseline funding in Product Schedules; whereas Navy included 10 funding line-items in its post-Rizzo Product Schedules.62 Navy’s line-items were also not aligned with Defence’s corporate budgeting system, BORIS. These costs could therefore only be adjusted and reported through manual manipulation of data in spreadsheets.

2.42 In December 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that Navy and the DMO had agreed on a level of financial detail—for inclusion in Product Schedules—that could be budgeted and reported through BORIS. However, implementation of the solution had not yet occurred.

2.43 Another aspect of the Navy Product Schedules that differs from the DMO template is the inclusion of additional availability and maintenance information. Navy has responded to the non-availability of ships and the Rizzo Report by adopting a detailed approach:

- a Product Activity Plan details the number of Materiel Ready Days required for the next year, as well as expected dates of maintenance for the next three years; and

- the schedule for external (contractor) maintenance of each ship (where relevant) is set out for the following five years rather than just for the current financial year, as was previously the case.63

2.44 The revised Navy MSA includes additional detail on mutual obligations, expenditure and maintenance scheduling, following significant failures in Navy which led to the unavailability of supply vessels. This approach reflects Navy’s relatively conservative risk appetite, and is intended to enable close oversight of the DMO’s management of sustainment activity. The design features of the Navy Product Schedules have led to very lengthy documents in comparison to other Services’ Product Schedules. For example, in 2013, the average Army Product Schedule was 28 pages, the average Air Force Product Schedule was 33 pages, and the average Navy Product Schedule was 70 pages.

Conclusion

2.45 For the most part, the MSAs examined by the ANAO met key characteristics of well-structured cross-entity agreements. The MSAs outline governance arrangements, respective roles and responsibilities, sustainment deliverables, performance reporting and monitoring arrangements, sustainment issues and risks, and dispute resolution procedures. These features of the MSAs serve to clarify accountabilities, coordination arrangements and relevant processes. The MSA framework has evolved over time, in light of practical experience and the risk appetite of the parties to individual agreements, and there is an ongoing role for Defence senior leadership to shape the direction of the framework so as to realise its full potential.

3. Materiel Sustainment Agreements in Operation

This chapter examines management reviews of MSAs, the change management process for Product Schedules, and the management of sustainment issues and risks.

Introduction

3.1 Working across organisational boundaries presents many challenges, including harmonising different strategies and business processes to achieve the intended outcomes for government. The DMO–Defence customer–supplier relationship requires effective collaboration at both senior executive and operational levels, supported by efficient processes for MSA oversight, change management, and issues and risk management.

3.2 In this chapter, the ANAO examines management reviews of MSAs, the change management process for Product Schedules, and the management of sustainment issues and risks. The ANAO’s analysis draws on the three selected MSA Product Schedule case studies: ANZAC ships, Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicles and Orion aircraft.

Management reviews of MSAs

3.3 Although a system of MSA management reviews existed prior to 2012, the reviews were sometimes intermittent. When the Heads of Agreement template was released with the Standard Procedure on MSAs in November 2012, it included an indicative MSA review system. This consisted of three tiers of review: Strategic MSA Reviews held at least every two years at CEO DMO level; twice-yearly Strategic Product Schedule Reviews at DMO Division Head level; and monthly Product Schedule Meetings at working level.

3.4 During 2012–13, in renewing their MSAs, each of the Services also renewed the number and type of regular MSA reviews. Table 3.1 shows the tiers of MSA review that have been established by each of the Services.

Table 3.1: Tiers of MSA review

|

Type |

Navy |

Army |

Air Force |

|

‘Strategic review’/ ‘Deep Dive’ |

Strategic Review – as required (3-Star) |

Deputy Chief of Army Product Schedule Review – at least once every three years for each Product Schedule (2Star) |

Strategic MSA Review – at least once every two years (3-Star) |

|

‘Fleet Screening’ – every six months |

Biannual MSA Review (2-Star) |

Capability Manager’s Product Schedule Screen (2-Star) |

Principals Meeting (2-Star) |

|

Force Element Biannual Progress Reviews (1-Star); these reviews were previously quarterly |

Capability Sustainment Review (1-Star) |

||

|

Sustainment Assessment Review (1-Star) |

|||

|

Working Level |

Operational Sustainment Management Meetings - monthly |

Working Groups – as required |

Product Schedule Performance Meetings - monthly |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Periodic reviews—‘Strategic Review’/‘Deep Dive’

Navy

3.5 The 2012 Navy–DMO Heads of Agreement established an Annual Strategic Review between the Chief of Navy and the CEO DMO to consider current and future high-level management issues and the overall performance of Navy sustainment. These Reviews had been proposed as part of the implementation of Rizzo Recommendations 11 and 12.64 However, to date, no meetings have taken place, and in January 2015 the frequency was changed to as-required.

Army

3.6 Army’s top level of review consists of ‘deep dives’ into Product Schedules (rather than strategic reviews), and these are formally known as Deputy Chief of Army (DCA) Product Schedule Reviews. The frequency of these deep dives varies with the level of risk identified for individual Product Schedules. Those deemed to present the highest risk are reviewed annually, with two and three-yearly reviews for those Product Schedules deemed to present medium and low levels of risk, respectively. These deep dives involve two to four hours of consideration of a single Product Schedule, and are intended to confirm the DMO’s management of Army materiel against the fleet management plan, Capability Manager priorities, budget constraints and the Product Schedule. The Product Schedule Reviews are empowered to approve funding priorities and transfers, and give in-principle agreement to inter-Service funds transfer for sustainment support. They can also authorise strategies to address particular sustainment issues.

Air Force

3.7 The first Air Force Strategic MSA Review occurred in June 2011, at Air Force’s initiative, with a view to establishing an annual forum of DMO and Air Force senior executives to discuss the broader strategic issues affecting the materiel sustainment of Air Force capability. At the time, Air Force was keen to use the MSA construct as a partnership rather than a customer–supplier relationship, acknowledging that it was only in recent times that Air Force had started to be involved at the appropriate depth of detailed understanding and engagement in the MSA and Product Schedule processes. During the June 2011 review, Air Force noted that its relationship with DMO was very good and continuing to mature, yet there were still opportunities for improvements, such as introducing a greater capability focus into Product Schedules, capability-driven KPIs and increased consistency in Air Force dealings across all DMO Divisions and SPOs. For its part, the DMO highlighted that in the past the MSAs had been ‘one way’, and that there was merit in pursuing a move to ‘two way’ arrangements and KPIs.

3.8 The 2013 Air Force–DMO Heads of Agreement provided for a Strategic MSA Review to be conducted at least once every two years, ‘to review the conduct of the MSA and the materiel sustainment relationship between the Air Force and the DMO’. No Strategic MSA Review has been held since 2011.

Six-monthly reviews—‘Fleet Screenings’

Navy

3.9 Navy conducts two levels of fleet screenings: Biannual MSA Reviews; and Force Element Biannual Progress Reviews, which consider the Product Schedules by Force Element Group.

3.10 The Biannual MSA Reviews form the most significant part of Navy’s MSA review system. These reviews consider the performance of all of the Navy Product Schedules for each DMO Division, and provide an opportunity for the Deputy Chief of Navy to manage sustainment funding between different Product Schedules, taking into account changing circumstances and operational needs. The reviews occur in February/March and September/October each year, to inform the development of the Commonwealth Budget. The reviews have generally been two-day events, and were well described in a recent Navy administrative instruction:

Cognisant of the findings of the Rizzo Report, the focus of the reviews has evolved beyond their original financial emphasis into a forum for DCN [Deputy Chief of Navy] and the relevant DMO Division/Group Head to consider how their respective organisations are meeting their obligations for whole of life management and sustainment of Navy capability. Financial planning and performance remains a key element of the reviews, and the composite view of Navy sustainment pressures provided by the biannual review activity enables DCN to make informed capability and resource allocation decisions.

3.11 The ANAO attended the October 2014 Maritime Systems Division fleet screening as an observer. The meeting demonstrated an open and collaborative relationship between Navy and the DMO, with attention given to the key issues affecting both parties.

Army

3.12 Army instituted its current system of biannual Product Schedule Screens in July 2012. The meetings provide an opportunity for Army to examine the current financial health of specific fleets; plan for the forward estimates; examine fleet and business management issues; move funding between products and assign priorities; and identify products to undergo a Product Schedule Review. The Product Schedule Screen is intended to occur over three days, and is chaired by the Deputy Chief of Army, who can adjust KPIs, approve funding priorities, and authorise management action plans to remediate issues.

Air Force

3.13 Air Force has the most intricate system of fleet screenings. Air Force’s Standing Instruction on MSAs notes that there are two review periods within each financial year: for the Defence Management and Financial Plan (DMFP) and the Mid-Year Review. The DMFP review period, between February and June each year, involves a strategic review of all materiel sustainment requirements to support Air Force capability. During the Mid-Year Review period, between September and December each year, Air Force and the DMO analyse the in-year sustainment and performance of all Air Force Product Schedules, and agree on the sustainment plan for the following financial year.

3.14 In each of the review periods, the same sequence of reviews occurs, namely Sustainment Assessment Reviews, Capability Sustainment Reviews, and Principals Meetings.65 Sustainment Assessment Reviews are led by the relevant DMO SPO and chaired by the DMO Branch Head. These reviews examine sustainment requirements, risks, issues, and the cost of achieving Air Force’s capability requirements. The reviews develop Management Options related to these areas, to feed into Capability Sustainment Reviews conducted by Force Element Groups. The Capability Sustainment Reviews analyse funded and unfunded sustainment requirements, risks and issues, and select specific Management Options for higher-level approval.

3.15 After these two reviews, an Air Force Capability Sustainment Plan is developed, and is endorsed by the Air Command Board in the lead-up to the Principals Meeting.66 In this way, Air Force is able to provide a

whole-of-sustainment proposal to the DMO from a capability-based perspective.

3.16 The Principals Meetings form the top tier of the six-monthly reviews. The DMFP Principals Meeting is chaired by the Deputy Chief of Air Force, and the Mid-Year Review Principals Meeting is chaired by the Air Commander Australia. The meetings consider and approve the Capability Sustainment Plan, omnibus Product Schedule Change Proposals67 for financial adjustments, and Change Proposals for any non-financial adjustments to a Product Schedule.

Ongoing review—Working Level Meetings

Navy

3.17 Navy’s working level meetings are termed Operational Sustainment Management Meetings. These meetings occur monthly, and include a comprehensive overview of the current status of the relevant Navy Product. The chief participants are the SPO Director and the Capability Manager Representative.

Army

3.18 The Army–DMO Heads of Agreement provides for working groups to be formed to address identified issues and engage with stakeholders, with the findings to be referred to a suitable forum for decision.68

3.19 In 2013, the DMO’s Head Land Systems Division initiated a new divisional level of review, referred to as Project and Product Review Boards. These Review Boards are intended to provide an opportunity for project and sustainment managers in various branches of the Division to inform the Head Land Systems about issues, and for him to provide direct input where necessary.

3.20 In August 2014, the DMO’s Land Systems Division informed the ANAO that:

There is a very strong (and regular) interaction between Land Systems Division and the Capability Manager that has created a much better shared understanding as to where each Product is at. This, linked with the DCA [Deputy Chief of Army] Reviews and new Head Land Systems Product Reviews, allows the twice-yearly screens to adopt a more strategic overview approach that focuses on the ‘big issues’. The layered approach, with multiple reviews and regular interaction, has allowed the six-monthly Product Screens to focus (as they should) on strategic 2-star issues: everything else gets picked up before these screens.

Air Force

3.21 The Air Force–DMO Heads of Agreement provides for Product Schedule Performance Meetings, to be conducted at least monthly, and to focus on the current and forecast performance of individual Product Schedules. The meetings are attended by SPO Directors and the relevant Air Force unit commanders and their teams.

Gate Reviews