Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Underperformance in the Australian Public Service

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of underperformance in the Australian Public Service (APS) and identify opportunities for improvement.

Summary and key learnings

Background

1. Performance management of employees is critical to supporting a high-performing Australian Public Service (APS). While the management of underperformance is only one aspect of an effective performance management framework, it is important because underperforming employees negatively impact efficiency, productivity and morale.

2. In conducting the audit, the ANAO examined the management of underperformance in eight agencies: Attorney-General’s Department; Australian Taxation Office; Department of Agriculture and Water Resources; Department of Industry, Innovation and Science; Department of Social Services; Department of Veterans’ Affairs; IP Australia; and the National Film and Sound Archive.

3. In relation to managing underperformance, APS agencies face a similar environment to many other organisations in Australia, public and private. Like many organisations, APS agencies are covered by the unfair dismissal provisions in the Fair Work Act 2009 and a range of other relevant legislation including state and federal work, health and safety laws and the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986. A key difference, however, is that APS agencies are covered by the Public Service Act 1999 that provides for specific requirements and confers additional rights of review for APS employees.

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management of underperformance in the Australian Public Service and identify opportunities for improvement. To form a conclusion on the audit objective the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- How effectively are audited agencies managing underperformance?

- Do the agencies’ documented underperformance procedures contribute to the effective management of underperformance?

- Do the agencies’ management practices contribute to the effective management of underperformance?

Conclusion

5. There is significant room for improvement in the management of underperformance in each of the eight audited agencies, although some agencies have managed underperforming employees better than others.

6. Underperformance is generally not effectively dealt with in performance management processes, including during the probation period in most agencies, and structured underperformance processes have been infrequently used. Managers have often avoided addressing underperformance due to a lack of incentives, support and capability. Some agencies have used redundancies or incentives to retire as alternatives to underperformance procedures and while these may be cost-effective approaches in situations of excess staffing or in particularly complex cases, they should not be used to replace or undermine ongoing, robust underperformance management procedures.

7. Most agencies could streamline their underperformance procedures to remove repetition and prescription while still ensuring procedural fairness, although provisions in three agencies’ enterprise agreements restrict flexibility in this regard. In addition, some agency procedures contain requirements that are in excess of those required by legislation or regulation for Senior Executive Service or non-ongoing employees. Not all agencies have transparent procedures for their Senior Executive Service employees, and probation procedures could be improved in all eight agencies.

8. Agency practices have contributed to the less than effective management of underperformance. In respect of performance management practices, there is scope for all agencies to improve managers’ commitment to dealing with underperformance, clear communication of performance expectations and provision of feedback to employees. To strengthen practices to manage underperformance, there is scope for most agencies to improve the support to and capability of managers, including through the provision of training in managing performance (including underperformance) and the early involvement of appropriately skilled human resource professionals in underperformance cases. There is considerable room for improvement in all agencies’ practices to hold managers accountable for their responsibilities to manage underperformance.

Supporting findings

The effectiveness of agencies’ management of underperformance

9. Employee perception data from the eight agencies indicates that only a minority of employees agreed that their agency deals with underperformance effectively, with agreement rates ranging from 14 to 30 per cent in 2016. For the Australian Public Service as a whole, less than a quarter of employees agreed that their agency effectively deals with underperformance. Compared to other census items assessing attitudes and opinions, this issue had the lowest employee perceptions. Perceptions were more positive in relation to employees agreeing that their supervisor appears to manage underperformance well with over half of employees in IP Australia, the Department of Social Services, the National Film and Sound Archive and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science agreeing in 2016. Comparisons with available Australian and international benchmarks on employee perceptions suggest that the Australian Public Service agencies achieve relatively low results.

10. Human resources data from the eight agencies indicates that there is significant room for improvement in the management of underperformance in each of the eight audited agencies, although some agencies have dealt with it better than others. In most agencies underperformance is not being accurately identified and the proportion of employees undergoing structured underperformance processes is very low1 in all agencies. Probation processes are not generally used robustly to test the suitability of newly appointed employees2 (except in the Australian Taxation Office and the National Film and Sound Archive). The use of redundancies and incentives to retire may be cost-effective in situations of excess staffing or in particularly complex cases, however, they should not be used to replace or undermine ongoing, robust underperformance management procedures as they can be uneconomical, create perverse incentives and generate resentment in other employees. The outcomes of structured underperformance processes have been varied—a high percentage of cases have resulted in performance improvement, other employees have left their agency through retirement or termination processes, with a range of other outcomes including employees transferring within the Australian Public Service. Notwithstanding the range of outcomes, agencies have generally managed underperformance processes in line with procedural fairness requirements.3

11. The main barriers to more effectively managing underperformance relate to agencies’ general management culture (that has tended to focus on compliance with end of cycle discussions rather than the quality and frequency of feedback), and the lack of incentives facing, support for and capabilities of, many senior and middle level managers. These barriers have limited the effectiveness of agencies’ management of underperformance in performance management processes, as well as in structured underperformance processes.

Underperformance management procedures

12. Agencies’ documented performance management procedures adequately support managers to manage underperformance of non-Senior Executive Level staff. All eight agencies’ procedures encourage ongoing, regular feedback outside of formal review points and early identification of, and prompt action to address, potential underperformance. Most agencies could more effectively support managers by providing: clearer and/or more concise guidance on the outcomes and behaviours that distinguish fully effective and unsatisfactory performance (Australian Taxation Office, Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, IP Australia and National Film and Sound Archive); and links to relevant information (all agencies other than the Australian Taxation Office).

13. Agencies’ underperformance procedures could better support managers to manage underperforming ongoing non-Senior Executive Level employees. None of the eight agencies’ procedures provide clear guidance on the support and assistance available to managers from human resources professionals. Most agencies could streamline their procedures to remove time consuming repetition and prescription while still ensuring procedural fairness. Three agencies are restricted, however, because of provisions in their enterprise agreements. The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science could streamline provisions for non-ongoing employees.

14. All agencies have documented performance and underperformance management procedures that cover Senior Executive Service (SES) employees except the National Film and Sound Archive (which only has two SES positions). The SES procedures of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science and IP Australia are not transparent. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs has scope to streamline its procedures for managing underperformance of SES employees as these employees do not have access to unfair dismissal provisions.

15. There is scope for all eight agencies to improve their probation procedures. Two agencies (Attorney-General’s Department and Department of Agriculture and Water Resources) only provide limited guidance to managers via the pro forma report that managers complete for probationary employees, and the Department of Social Services only has procedures for its entry level programs. Only the Department of Veterans’ Affairs clearly informs managers that probationary employees do not have access to unfair dismissal provisions.

Underperformance management practices

16. The effectiveness of the management of underperformance through performance management processes varies with the importance placed on it by senior managers and the capability of individual employees. However, the relatively low level of employees who agree that underperformance is managed effectively in their agency, the low level of employees rated as ‘less than effective’ in most agencies and the barriers to managing underperformance indicate that performance management practices do not effectively underpin the management of underperformance. In particular, there is scope for all agencies to improve: the extent to which managers openly demonstrate commitment to performance management; how managers provide employees with clear and consistent performance expectations; and the quality and quantity of feedback being received by employees. Recent evaluations of, and changes to, agency performance management systems are likely to have contributed to improvements in employee perceptions of seven of the eight agencies over the four year period 2012–13 to 2015–16.

17. Agencies’ practices that support managers to manage underperformance are a key component of addressing barriers to the effective management of underperformance, particularly those relating to manager capability and commitment. While all agencies offer some support to managers through training and with assistance through the structured processes for managing underperformance, some agencies (particularly IP Australia) offer more active support and higher levels of training than others. Generally, those agencies that offer higher levels of support and training have more positive employee perceptions about the management of underperformance. The early involvement of appropriately skilled human resource professionals in underperformance processes delivers a range of benefits including acting as a quality assurance mechanism, ensuring managers and employees are adequately supported, and keeping processes within timeframes.

18. There is considerable room for improvement in all agencies’ practices to hold managers accountable for their performance management responsibilities. Only two agencies (Department of Social Services and National Film and Sound Archive) reported that they have recently used multi-source feedback or other means of gathering evidence on which to accurately assess individual manager’s performance management skills. While most agencies (excluding the Attorney-General’s Department and the National Film and Sound Archive) include some metrics on performance management in their human resources reporting to senior management, none of the eight agencies include general metrics relating to probation management and, with the exception of the Australian Taxation Office and the Department of Social Services, do not include training participation rates. Only the Australian Taxation Office collects survey data on the quality and quantity of feedback (in addition to relevant questions in the Australian Public Service Commission’s annual employee census) but this data is not included in its management reports.

Key learnings

19. The key learnings are organised around the four categories of barriers to underperformance management identified in Chapter 2.

Procedures

20. Based on the audit findings, the ANAO has identified a range of key learnings relating to agencies’ documented performance, underperformance and probation procedures that can apply to the eight and other APS agencies.

|

Box 1: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Management culture’ |

|

To demonstrate senior management commitment to agency performance management arrangements, including underperformance management:

|

|

Box 2: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Support to managers’ |

|

To effectively support managers, agency procedures should:

|

|

Box 3: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Manager capability’ |

|

To assist managers to implement underperformance procedures, it would be beneficial to have links to tools such as checklists, flowcharts and tips and tricks; and links to other guidance on fitness for duty, misconduct, and probation on agency intranet sites. |

|

Box 4: Key learnings to address ‘other’ barriers |

|

Performance gaps can be difficult to identify in a specific and objective way for some types of APS work. To assist managers to measure performance gaps, agency procedures would benefit from:

|

Practices

21. The ANAO has identified a range of key learnings relating to agencies’ practices for managing underperformance that can apply to the eight and other APS agencies.

|

Box 5: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Management culture’ |

|

|

Box 6: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Support to managers’ |

|

|

Box 7: Key learnings to address barriers relating to ‘Manager capability’ |

|

|

Box 8: Key learnings to address ‘other’ barriers |

|

Summary of entity responses

22. A summary of entity’s responses are below, with full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department welcomes the findings of the ANAO audit into underperformance across the APS (the audit). The department is currently reviewing its performance framework and related systems, policies, procedures and supporting guidance following the commencement of the Attorney-General’s Department Enterprise Agreement 2016.

Following this review process, and informed by the key learnings from this audit, the department will seek to implement initial changes to its performance framework for the 2017-18 performance cycle. The department is keenly committed to promoting a high performance culture built on ongoing performance and development feedback and conversations, and to ensure clarity and support in addressing poor performance as quickly as possible.

Australian Public Service Commission

The APSC welcomes the ANAO audit report on Managing Underperformance in the APS and the opportunity to comment on the content and findings of the report. The collaborative approach adopted by the ANAO and its receptiveness to APSC input were much appreciated.

The APSC agrees that there is room for improvement in the management of underperformance in the APS, and supports the audit findings. We emphasise that the management of underperformance takes place within a broader context of organisational culture and leadership. This will impact the effectiveness of any measures to improve the management of underperformance, as will the support offered to managers of people more generally.

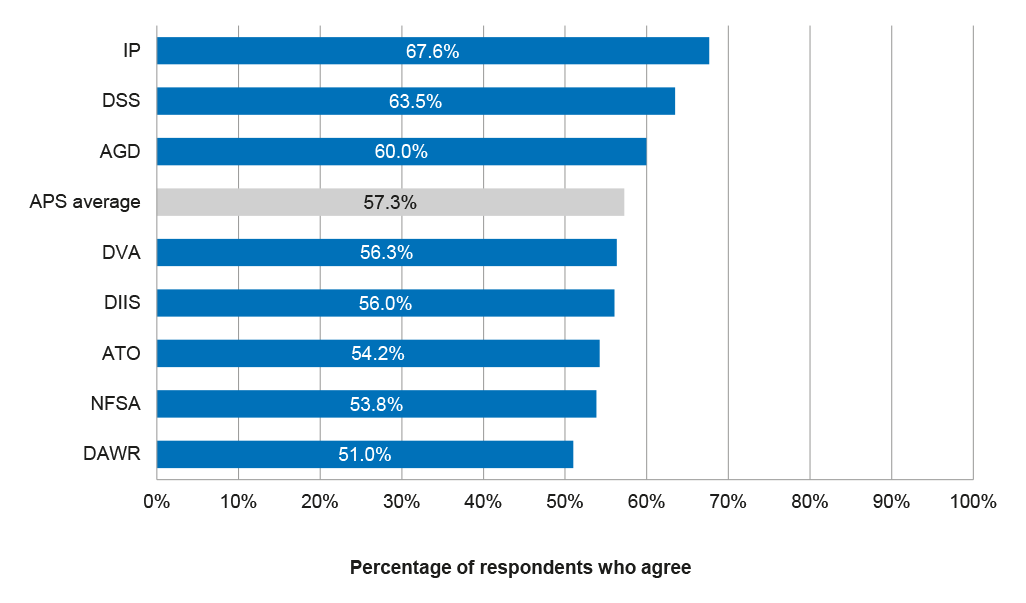

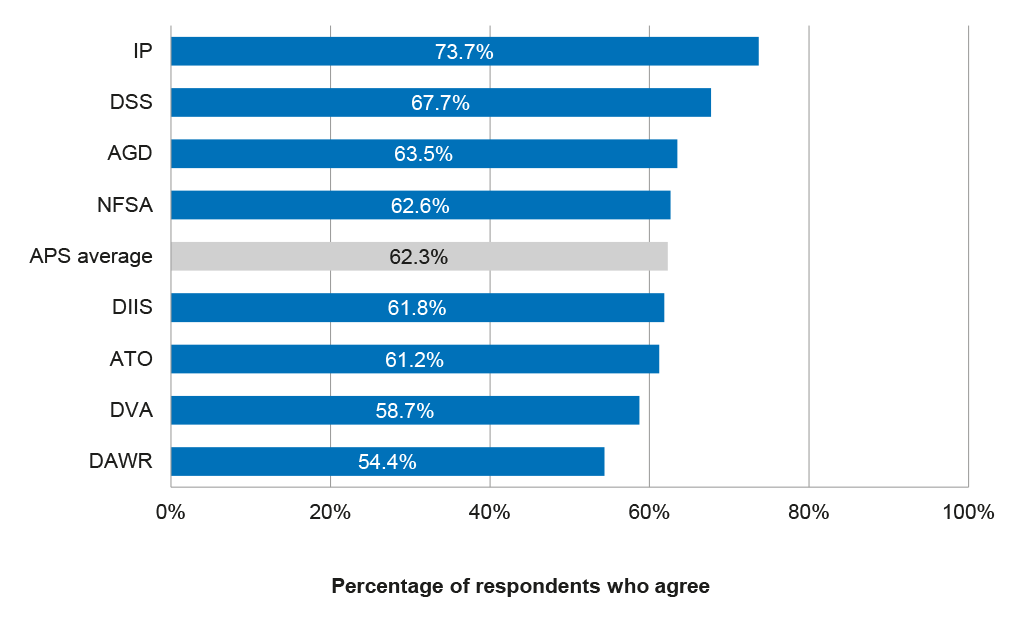

We are concerned that the selective use of data from the APS Employee Census in Figures 2.1 and 2.2 of the report may lead to people to misinterpret employee views on how underperformance is managed. The decision not to include the large proportion of respondents who neither agree nor disagree with these items could present a more negative perception by employees than is the case. This has been discussed with the ANAO.

Performance management is an area of particular focus for the APS. Agencies are trialling and implementing a number of initiatives to provide managers with the skills and tools they need to become more effective people managers.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to managing underperformance within the ATO. Particularly pleasing to see is the strong performance of the ATO in managing employees through probation and the alignment of more recent ATO developments to the best practice processes highlighted in the report. As the ATO continues to look for improvement opportunities, the ATO also recognises the important responsibility which employees have to meet, or seek support to meet, their performances requirements.

The review considers the procedures and practices agencies use to identify and deal with underperformance for employees. The review also notes the frameworks and challenges which agencies face when managing underperformance. The ATO agrees with the key learnings contained in the report, including the advice to streamline processes where possible, improve transparency of processes, provide information and ongoing support to managers who supervise underperforming staff and to effectively use probation for new employees who do not meet the requisite standards. The ATO has been and will continue to strengthen its management of underperformance in light of the findings of this report. [Further comment in Appendix 1].

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

The information provided in the proposed audit report on Managing Underperformance in the Australian Public Service highlights the importance of making changes to the way performance is managed across the department to ensure the department is positioned towards creating and maintaining a high performing culture.

The department notes in conclusions drawn from the audit that there is significant room for improvement in the management of underperformance, across a number of key areas, such as the management of underperformance during probation periods and structured underperformance processes.

The department acknowledges the need for change in the management of SES performance management processes, to streamline and provide greater transparency, as well as providing a greater level of support to managers and building manager capability in all areas of employee performance. These areas, along with other recommendations in the proposed audit report, will be incorporated into the current review into the department’s Performance Management Framework and associated processes.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science acknowledges the findings and key learnings of the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report on Managing Underperformance in the APS.

Department of Social Services

The Department of Social Services is pleased to have been one of the eight agencies audited in the managing underperformance in the Australian Public Service Audit in 2016.

I encourage all employees and managers to take ownership of the audit findings and to work towards building a culture that celebrates high performance, supports managers to hold difficult conversations, and encourages employees to remain open to feedback and accept responsibility for their performance and improvements when needed.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs notes the finding of the report and considers that, with inclusion of editorial comments, it provides a fair representation of departmental processes.

The key learnings from this audit will be used to bring about improvements in underperformance management in the department.

IP Australia

IP Australia welcomes the key learnings of this review and acknowledges the importance of effective underperformance management in the APS. We acknowledge that there is need for improvement in managing underperformance across the APS and we appreciate the report’s recognition of the substantive and significant improvements IP Australia has recently made to our overall performance management framework.

We see value in the report’s compilation of information on the varied approaches to underperformance management across the eight APS agencies and will reference this when considering further refinements and improvements to IP Australia’s processes.

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia

The NFSA agrees with the conclusions of the report and supports the key learnings identified which it will take into consideration when next it reviews the NFSA Performance Management and Development Policy and Procedures, which include the management of underperformance.

The NFSA regards the key learnings of the audit report to be essential feedback required for the agency to become a higher performing organisation.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Performance management of employees is critical to supporting a high-performing Australian Public Service (APS). While the management of underperformance is only one aspect of an effective performance management framework, it is important because underperforming employees negatively impact efficiency, productivity and morale.

Legal and regulatory framework for managing underperformance

1.2 In relation to managing underperformance, APS agencies face a similar environment to many other organisations in Australia, public and private. A key difference, however, is that APS agencies face requirements arising from the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act). The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 also requires agency heads as the accountable authority to promote the proper use and management of public resources.

Public Service Act 1999 and Regulations, and Australian Public Service Commissioner’s Directions

1.3 APS agencies are covered by the PS Act and Regulations and the Australian Public Service Commissioner’s Directions. The 2013 amendments to the PS Act and Directions4 increased the obligations for agencies to have formal performance management processes to ensure that each employee has a written performance agreement and regular performance discussions. These processes and discussions must be consistent with the APS Values, Code of Conduct and the Employment Principles that are all set out in the PS Act. APS managers, particularly agency heads and Senior Executive Service employees, who fail to adequately deal with underperformance are not upholding aspects of the APS Values and the Employment Principle that requires effective performance from each employee.5

1.4 The performance management obligations imposed on agency heads and managers by the PS Act are one of the differences facing APS agencies compared to other Australian organisations (arguably imposed, however, in the absence of the market forces that drive performance management in the private sector). Another difference is that APS employees have a right to a review of actions relating to management decisions. For example, an employee can seek a review of a management decision relating to a performance rating of ‘unsatisfactory’ or a decision to place an employee on a performance improvement plan. An initial review of action is conducted by the agency and, if the employee is not satisfied, they can apply for a secondary review to the Merit Protection Commissioner. An employee cannot, however, seek a review of a termination decision from the Merit Protection Commissioner—that must be done via an unfair dismissal application to the Fair Work Commission.

Fair Work Act 2009

1.5 APS agencies are covered by the unfair dismissal provisions in the Fair Work Act 2009 in relation to terminating the employment of an underperforming employee. These provisions require procedural fairness to be followed. Otherwise any termination can be found to be ‘harsh, unjust or unreasonable’, with remedies including reinstatement and payment of compensation. Key features of procedural fairness include:

- the employee must receive a warning (generally written) about unsatisfactory performance that identifies the performance issues;

- the warning must make it clear that the employee’s employment is at risk unless performance improves;

- the employee must be given a genuine chance to improve their performance (however, no fixed period between the warning and termination is specified); and

- if a decision is subsequently made to terminate the employee for underperformance, the employee must be advised of this and given a chance to respond, for example, to outline any extenuating circumstances such as illness.

1.6 These processes apply to employees who are covered by an award or an enterprise agreement or who earn less than the high income threshold ($138 900 at 1 July 2016)6 after six months of employment (12 months for businesses with fewer than 15 employees).

1.7 The processes do not apply to independent contractors, irregular casuals, probationary employees and high income employees not covered by an award or enterprise agreement.

Enterprise agreements

1.8 APS agencies are usually covered by enterprise agreements that can specify additional processes relating to performance management. These additional processes are enforceable by the Fair Work Commission.

Internal procedures

1.9 APS agencies also usually have procedures that are set out in administrative or policy documents. If an enterprise agreement states that an underperformance process will be carried out in accordance with a specified policy document then any breach of the process in the document will be a breach of the enterprise agreement. The Australian Government Solicitor advises, furthermore, that even where procedures are not legally enforceable under an enterprise agreement, there is potential for the procedures set out in policy documents to give rise to procedural rights which are enforceable under administrative law.7

Employee action

1.10 All Australian employees have a range of actions they can take in relation to their performance management including under federal or state unfair dismissal legislation, the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 and the Disability Discrimination Act 1992. Administrative law and laws relating to breach of contract can provide other avenues of redress.8 APS employees can also request a review of actions under the PS Act as discussed in paragraph 1.4.

1.11 Some APS employees being managed for underperformance make allegations of bullying and harassment against their manager. These allegations require examination under the PS Act (Code of Conduct) and, in some circumstances, the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013.

Underperformance in the Australian Public Service

1.12 The term ‘underperformance’ is not used in the PS Act, rather the term is ‘unsatisfactory performance of duties’, which is not defined in the Act. In accordance with its ordinary meaning ‘unsatisfactory performance’ would extend to any situation where an employee does not have the capacity or ability to satisfactorily perform duties.9 An employee can be performing to the best of their ability and still be performing unsatisfactorily.10

1.13 The Australian Government Solicitor advises APS agencies against using underperformance processes for breaches of the Code of Conduct, or where there is a health issue that should be dealt with by way of management of a medical problem.11

1.14 The key purpose of actively managing underperformance is to assist the employee to be able to consistently meet the performance expectations of their job and work level standard and thereby ensure the performance and productivity of the agency. It is only when it becomes clear after a reasonable period of active assistance that the employee is unable to meet expectations that the focus of underperformance management shifts to considering other remedies including reclassification to a lower classification or termination.

Causes of underperformance

1.15 The causes of underperformance in the APS are varied. Under the PS Act employees have a personal responsibility to achieve the performance expectations of their job. Some performance problems relate to personal and/or physical and mental health issues facing employees. Cases of underperformance that also include some medical, personal or minor misconduct aspects (such as minor absenteeism or minor behavioural issues) can be particularly complex to manage.

1.16 One root cause of underperformance occurs when recruitment processes fail to select candidates that closely match the capabilities and personal attributes required for the work at the agency, combined with the under-use of probationary periods to actively test the suitability of newly appointed employees. Other causes relate to inadequate management skills where job expectations and tasks are not clearly specified and explained and where employees do not receive regular, constructive feedback on their performance so that any performance gaps can be addressed early. A lack of access to training and development to ensure employees keep skills and capabilities up to date as work design and technology changes can also lead to underperformance, although some employees have difficulties successfully adapting to changes that require new capabilities despite access to training.

Characteristics of audited agencies

1.17 In conducting the audit, the ANAO examined the management of underperformance in eight agencies: Attorney-General’s Department (AGD); Australian Taxation Office (ATO); Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR); Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (DIIS); Department of Social Services (DSS); Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA); IP Australia (IP); and the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA). These agencies were selected to provide a mix of agencies according to size, function, satisfaction with the management of underperformance and performance as indicated by employee views and agency self-reporting, as well as the extent of other ANAO audit coverage of the agency. Table 1.1 sets out characteristics of the eight agencies.

Table 1.1: Characteristics of audited agencies, 2016

|

Agency |

Characteristics |

|||||||||

|

|

Functions |

No. of staffa |

Major occupations |

APS |

EL |

SES |

Median service length |

|||

|

No. |

% of total |

No. |

% of total |

No. |

% of total |

|||||

|

AGD |

Policy advice and programs on legal framework, national security and emergency management |

2 003 |

Administration; Legal & parliamentary; Strategic policy |

1 074 |

54 |

760 |

38 |

169 |

8 |

6 |

|

ATO |

Regulator—principal revenue collection agency, administers major aspects of Australia’s superannuation system |

20 384 |

Compliance & regulation; Information & communications; Service delivery |

15 820 |

78 |

4 343 |

21 |

221 |

1 |

13 |

|

DAWR |

Policy, regulator, programs on agriculture, fisheries and forestry, including biosecurity |

5 034 |

Compliance & regulation; Project & program; Strategic policy |

3 884 |

77 |

1 057 |

21 |

93 |

2 |

10 |

|

DIIS |

Policy advice, program delivery on driving economic growth, productivity and competitiveness |

2 734 |

Administration; Project & program; Strategic policy |

1 488 |

54 |

1 178 |

43 |

68 |

2 |

7 |

|

DSS |

Social policy, programs, services on social security, families, communities, disability carers and housing |

2 362 |

Administration; Project & program; Strategic policy |

1 409 |

60 |

889 |

38 |

64 |

3 |

11 |

|

DVA |

Policy strategy, program management and service delivery to assist the veteran and defence force communities |

2 006 |

Strategic policy; Administration; Project & program; Service delivery |

1 610 |

80 |

366 |

18 |

30 |

1 |

14 |

|

IP |

Grants patent, trade mark, industrial design and plant breeder’s rights |

1 178 |

Administration; Engineering & technical; ICT |

798 |

68 |

369 |

31 |

11 |

1 |

9 |

|

NFSA |

Develops, preserves and presents Australia’s national audiovisual and related collections |

199 |

Information & knowledge |

164 |

82 |

33 |

17 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

Note: Percentage totals may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Note a: All APS employees—both ongoing and non-ongoing.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Australian Public Service Statistical Bulletin, State of the Service Series 2015–16, and ANAO analysis of Australian Public Service Commission’s employee census data. Data for DIIS and IP Australia provided by these agencies.

Stages of underperformance management

1.18 Figure 1.1 sets out three stages of underperformance management identified by the ANAO. The figure highlights the key role that managers have in supporting employees whose performance falls below expectations and in deciding whether or not underperforming employees enter into more structured or formal underperformance procedures. There is an unknown percentage of employees whose underperformance is not actively managed and is ‘worked around’. Less than one per cent of employees in the eight agencies enter stages 2 and 3 of underperformance management. Chapter 2 provides more discussion and data on underperformance processes.

Figure 1.1: Three stages of underperformance management

Note a: Progressing from Stage 1 to 2 in some agencies requires approval from the human resources unit (HR).

Note b: Exact percentage of employees undergoing stage 2 processes is unknown but 0.5% is an upper estimate.

Note c: Progressing from Stage 2 to 3 requires formal approval in all agencies.

Note d: Average percentage of employees for eight agencies.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management of underperformance in the Australian Public Service and identify opportunities for improvement.

1.20 To form a conclusion on the audit objective the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- How effectively are audited agencies managing underperformance?

- Do the agencies’ documented underperformance procedures contribute to the effective management of underperformance?

- Do the agencies’ management practices contribute to the effective management of underperformance?

1.21 The audit focussed on eight agencies’ management of underperformance over the four financial years 2012–13 to 2015–16. The audit scope did not include agencies’ performance management systems more generally but did include their interaction with the management of underperformance. The focus on underperformance rather than performance management more broadly was in part because of ongoing work being undertaken by the Australian Public Service Commission in the latter area.12 Some agencies, notably the Australian Taxation Office and IP Australia, have recently implemented significant changes to their performance management frameworks (see Table 4.3 that summarises change to agencies’ performance management systems over the four year period). Accordingly, some of the data examined in the audit relates in part to superseded schemes and/or transitional periods. The analysis of procedures and policies in Chapter 3, however, is of agencies’ most current performance and underperformance frameworks.

Audit methodology

1.22 The major audit tasks included:

- analysing data from the Australian Public Service Commission’s annual employee census and annual agency survey, agencies’ own human resource databases and available benchmarking data from Australia and overseas;

- reviewing relevant agency documentation including policies, procedures, internal and external evaluations/reviews of agencies’ performance management frameworks and conducting a literature review; and

- interviewing corporate support staff from each agency, employee representatives with coverage in the APS and relevant academics.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $530 000.

1.24 The team members for this audit were Linda Kendell, Robyn Clark, Luke Josey, Benjamin Readshaw and Andrew Morris.

2. The effectiveness of agencies’ management of underperformance

Areas examined

This chapter examines the available data relevant to agencies’ management of underperformance and identifies the key barriers to more effective management.

Conclusion

There is significant room for improvement in the management of underperformance in each of the eight audited agencies, although some agencies have managed underperforming employees better than others.

Underperformance is generally not effectively dealt with in performance management processes, including during the probation period in most agencies, and structured underperformance processes have been infrequently used. Managers have often avoided addressing underperformance due to a lack of incentives, support and capability. Some agencies have used redundancies or incentives to retire as alternatives to underperformance procedures and while these may be cost-effective approaches in situations of excess staffing or in particularly complex cases, they should not be used to replace or undermine ongoing, robust underperformance management procedures.

Areas for improvement

Given the barriers to managing underperformance the main areas for improvement are those that will:

- encourage an effective performance management framework that results in frequent, informal conversations between managers and their staff that are aimed at improving employees’ performance (rather than complying with process requirements); and

- actively support, recognise and reward managers who are willing to manage performance and underperformance and create a culture that makes managers who do not manage performance and underperformance more accountable.

Do employees consider that underperformance is effectively managed in their agency?

Employee perception data from the eight agencies indicates that only a minority of employees agreed that their agency deals with underperformance effectively, with agreement rates ranging from 14 to 30 per cent in 2016. For the Australian Public Service as a whole, less than a quarter of employees agreed that their agency effectively deals with underperformance. Compared to all other census items assessing attitudes and opinions, this issue had the lowest employee perceptions. Perceptions were more positive in relation to employees agreeing that their supervisor appears to manage underperformance well with over half of employees in IP Australia, the Department of Social Services, the National Film and Sound Archive and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science agreeing in 2016. Comparisons with available Australian and international benchmarks on employee perceptions suggest that the Australian Public Service agencies achieve relatively low results.

Data from the Australian Public Service Commission’s employee census

2.1 The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) conducts an annual employee census that asks employees a number of questions on a range of public administration issues including performance management generally and underperformance management specifically. Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2 present data on employees’ perceptions on how well their agency and supervisor managed underperformance for the eight agencies.13 Employees’ perceptions on their agency’s management were significantly worse than their supervisor’s management of underperformance across all agencies. At the APS-wide level, the percentage of employees who agreed with the statement ‘my agency deals with underperformance effectively’ was the lowest compared with all other attitude and opinion items on similar agree/disagree scales. It is important to note that employee perceptions in this area are likely to be affected by wider organisational or cultural issues and by the impact of privacy and confidentiality concerns. For example, other employees are unlikely to know what management activity is being undertaken as it is not appropriate for a manager to discuss underperformance matters with other staff members.

Figure 2.1: ‘My agency deals with underperformance effectively’, 2016

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by the APSC.

Figure 2.2: ‘My supervisor appears to manage underperformance well in my group’, 2016

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by the APSC.

2.2 Figure 2.3 presents data on employee perceptions on their agencies’ management of underperformance over the last four years. The average result for the APS as a whole has been on an upward trend. Most of the eight agencies have also improved their result over the four years. The only exception was the NFSA whose 2015–16 result was slightly below its 2012–13 result.

Figure 2.3: ‘My agency deals with underperformance effectively’, 2012–13 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by the APSC.

2.3 The causes behind the improving trend are difficult to determine given the many interrelated factors that impact on employees’ perceptions in this area. It is likely, however, that the changes made as a result of responding to internal and external reviews of agencies’ performance management frameworks, as set out in Table 4.3 in Chapter 4, have had some positive impact, noting that NFSA was the only agency not making any changes to its performance or underperformance framework over the period.

Australian and international benchmarking data

2.4 A number of Australian and international organisations also conduct surveys that ask employees about their views on the management of underperformance. Table 2.1 outlines the relevant questions and the results of the surveys for various groupings of those organisations.

Table 2.1: Employee perceptions benchmarking data, 2015 (percentage of employees agreeing with question)

|

Question |

Irish civil service |

APS |

USA federal service |

UK civil service |

Qld public service |

Public sector world |

Australia |

Private sector world |

|

Poor performance is effectively addressed throughout the department |

12% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

My agency deals with underperformance effectively |

- |

21% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

In my work unit, steps are taken to deal with a poor performer who cannot or will not improve |

- |

- |

28% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Poor performance is dealt with effectively in my team |

- |

- |

- |

39% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

I am confident that poor performance will be appropriately addressed in my workplace |

- |

- |

- |

- |

40% |

- |

- |

- |

|

Poor performance is dealt with effectively where I work |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

40% |

46% |

48% |

Note: The table includes only results from employee surveys that used a similar five point scale to the one used by the APSC employee census (strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, strongly disagree).

Source: APSC 2015 Employee Census; Working for Queensland Employee Opinion Survey 2015; Irish Civil Service Employee Engagement Survey 2015; United Kingdom Civil Service People Survey 2015; United States of America Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey 2015; and Australia, Private Sector worldwide and Public Sector worldwide data is drawn from the ORC International’s Perspectives database. ORC International is an independent market research company that specialises in employee research for public and private sector organisations. The APSC, the Queensland Public Service Commission and the UK Civil Service engaged ORC International to coordinate their respective employee surveys.

2.5 As there is no exact match to the APS question ‘my agency deals with underperformance effectively’, as shown in Table 2.1, it is not possible to be definitive about the relative position of employee perceptions on underperformance in the APS compared to other sectors. However, ORC International (that provided the benchmarking data for the ‘Australia’, ‘Private sector worldwide’ and ‘Public sector worldwide’ groupings14) rated the match between the question for the APS and the question for these three groups as a category 2 match, that is, there was a match for two of construct, context and/or intent (the best match—a category 1 match would be where there was a match for all three of construct, context and intent). These three groups recorded results significantly higher than the APS (all had 40 per cent or more of staff agreeing with the question compared with 21 per cent for the APS). The only group that had a lower result than the APS was the Irish Civil Service at 12 per cent of employees.

Does agency data indicate that underperformance is effectively managed?

Human resources data from the eight agencies indicates that there is significant room for improvement in the management of underperformance in each of the eight audited agencies, although some agencies have dealt with it better than others. In most agencies underperformance is not being accurately identified and the proportion of employees undergoing structured underperformance processes is very lowa in all agencies. Probation processes are not generally used robustly to test the suitability of newly appointed employeesb (except in the Australian Taxation Office and the National Film and Sound Archive). The use of redundancies and incentives to retire may be cost-effective in situations of excess staffing or in particularly complex cases, however, they should not be used to replace or undermine ongoing, robust underperformance management procedures as they can be uneconomical, create perverse incentives and generate resentment in other employees. The outcomes of structured underperformance processes have been varied—a high percentage of cases have resulted in performance improvement, other employees have left their agency through retirement or termination processes, with a range of other outcomes including employees transferring within the Australian Public Service. Notwithstanding the range of outcomes, agencies have generally managed underperformance processes in line with procedural fairness requirements.c

Note a: The proportion of employees whose performance is rated as less than effective is less than would be reasonably expected, although proportions vary among agencies (from 0.1 to 3.1 per cent of all employees rated from 2012–13 to 2015–16). The proportion of employees who are formally managed for underperformance is even smaller for each of the eight agencies.

Note b: While not all of the eight agencies could provide data, the proportion of employees with performance issues that left during their probationary period was low except in the ATO. In combination with information on agencies’ procedures, it appears that most agencies did not use probation to robustly assess performance to test job fit and the appropriateness of recruitment decisions.

Note c: As indicated by the low rate of successful Comcare claims, unfair dismissal claims and reviews of actions (five per cent or less of employees with known performance issues in all agencies from 2012–13 to 2015–16).

Performance ratings data

2.6 An indicator of how agencies are managing underperformance is the proportion of employees who are rated as underperforming, that is, rated as ‘less than effective’. Table 2.2 indicates that for most agencies very low levels of employees have been rated as ‘less than effective’ at the end of year performance cycles over the past four years.15 The unweighted average16 for the eight agencies was 1.27 per cent of employees per year. Two agencies, DSS and AGD, had significantly higher proportions of employees rated less than effective at around three percent annually over the four years.

Table 2.2: Percentage of employees rated less than effective once, and more than once, during the period 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Agency |

Number of employees rated less than effective—Total over four years |

Percentage of employeesa rated less than effective—Average annual over four years |

Of the employees rated less than effective—percentage that were rated so more than once |

|

DSS |

338 |

3.06 |

19.2 |

|

AGD |

176 |

2.73 |

11.2 |

|

DVA |

149 |

1.88 |

10.0 |

|

DAWR |

173 |

0.92 |

18.5 |

|

ATOb |

408 |

0.67 |

7.4 |

|

IP |

20 |

0.46 |

13.3 |

|

DIISc |

42 |

0.33 |

NA |

|

NFSA |

1 |

0.11 |

NA |

Note: NA means data is not available. DIIS and NFSA were unable to extract this data from their data systems.

Note a: Employees covered by the agencies’ performance management scheme.

Note b: ATO performance ratings data was not available for 2015–16.

Note c: DIIS performance ratings for SES employees were only available for 2014–15 and 2015–16.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

2.7 Table 2.2 also includes data on the proportion of employees that were rated as ‘less than effective’ more than once over the past four year periods. An employee being rated as ‘less than effective’ more than once is likely to be an indication that underperformance is not being managed in a timely and effective way although changes in jobs and/or managers may contribute to such a rating being given twice. Both DAWR and DSS had relatively high proportions of employees in this category—18.5 per cent and 19.2 per cent respectively—however, both DAWR’s and DSS’ performance scales include a ‘less than effective’ rating17 that indicates an employee may be adjusting to a new role but is meeting most expectations. The agency with the lowest proportion of employees rated ‘less than effective’ twice was the ATO at 7.4 per cent. Ideally, nearly all employees who receive a rating of ‘less than effective’ would either receive assistance to sustainably improve their performance or, if unable to meet expectations, be managed through a more structured underperformance process within a 12 month period.

2.8 The ANAO conducted a literature review in relation to the proportion of employees that could be expected to be rated as unsatisfactory or ‘less than effective’ in a large organisation. Many global corporations and other large organisations have used a forced distribution performance evaluation system that assumes a normal distribution or bell (symmetrical) curve for employee performance. Under this system, managers, using a three or five point rating scale, were forced to rate a fixed proportion of staff as unsatisfactory and the same proportion of staff as outstanding performers, for example, 10 per cent of staff in each category.18 Despite not having a forced distribution system the Irish Civil Service anticipated in 2013, using a five point scale, that the performance of up to 10 per cent of staff would be rated as ‘unsatisfactory’ and up to 20 per cent would be rated as ‘needs to improve’.19 In 2014, 0.05 per cent of Irish Civil Service employees were rated as ‘unsatisfactory’ and 0.56 per cent as ‘needs to improve’. The Irish Department of Public Expenditure and Reform concluded that the actual ratings ‘would seem to indicate that line managers are not realistically assessing the performance of staff’.20

2.9 A 2014 survey conducted by Deloitte Consulting indicated that there has been a move away from forced distribution performance evaluation systems. The survey indicated that ’70 per cent of respondents stated that they are either currently evaluating or have recently reviewed and updated their performance management systems’.21

2.10 The results of the literature review were inconclusive on the proportion of employees that might be anticipated to be performing below expectations in large organisations. The weight of evidence collected for the audit suggests, however, that less than one per cent of employees being rated as less than effective (as is the case in five out of the eight APS agencies) is below the proportion of underperforming employees:

- A majority of the human resource or corporate staff interviewed for the audit agreed that the proportions of staff identified as underperforming under-represented the extent of underperformance in their agency.

- Professor Deborah Blackman, University of NSW, advised that, based on her research for the Australian Public Service Commission’s (APSC’s) Strengthening the Performance Framework project, the proportion of staff being formally rated as less than effective significantly underestimated the actual proportions of staff performing below expectations.22

- The Department of Communications and the Arts, which over recent years has implemented a proactive underperformance management strategy, advised it has been successful in identifying and engaging in the resolution of underperformance cases. The strategy supports timely, open and honest conversations about performance, with specialist human resource staff advising, coaching and guiding managers and staff to achieve the most appropriate outcomes. The Department advised that in 2014–15 it rated 37 employees (around nine per cent of ongoing employees) as ‘not meeting expectations’ during the performance management cycle. In 2015–16, 52 employees were also rated as ‘not meeting expectations’, which again comprised around nine per cent of ongoing employees. The Department advised that that it has effectively resolved more than 90 per cent of these cases through coaching conversations, structured ‘back on track’ plans and formal performance improvement plans.

- Research undertaken in the United States of America (USA) is also of some relevance. A USA Office of Personnel Management survey of supervisors estimated that poor performers constituted 3.7 per cent of the federal public sector workforce and a USA Merit Protection Board survey found that employees perceived 14.3 per cent of their co-workers to be performing below reasonably expected levels.23

Employees undergoing underperformance management

2.11 Table 2.3 shows the average annual percentage of employees undergoing structured underperformance processes (stage 2 and stage 3 processes as outlined in Figure 1.1) over the past four years. It is clear that the proportion of employees undergoing structured underperformance processes is very low in all eight agencies and lower than the proportion of staff being rated as less than effective. In relation to stage 3 processes, the highest percentage was 0.28 per cent of employees for the NFSA with the lowest being 0.03 per cent for the ATO. The unweighted average annual proportion for the eight agencies was 0.13 per cent.

Table 2.3: Percentage of employees undergoing formal underperformance management processes, 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Agency |

Number of employees |

Average annual percentage of ongoing staff |

Number of employees |

Average annual percentage of ongoing staff |

|

|

Stage 2 |

Stage 3 |

||

|

AGDa |

14 |

0.29 |

11 |

0.23 |

|

ATO |

342 |

0.43 |

23 |

0.03 |

|

DAWR |

NA |

NA |

12 |

0.07 |

|

DIISb |

NA |

NA |

23 |

0.20 |

|

DSS |

13 |

0.14 |

9 |

0.09 |

|

DVAa |

11 |

0.15 |

3 |

0.04 |

|

IPc |

6 |

0.13 |

6 |

0.13 |

|

NFSA |

NA |

NA |

2 |

0.28 |

Note: NA means data is not available.

Note a: AGD and DVA did not have complete records of stage 2 processes so the data for stage 2 underestimates the actual number.

Note b: DIIS provides general guidance for managers around stage 2 but no specific procedures are prescribed.

Note c: IP Australia streamlined stage 2 and 3 in July 2016 as part of a new performance management scheme. Data refers to previous scheme.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

2.12 Table 2.4 presents data on underperformance processes by classification group. For all eight agencies except IP Australia and DIIS, the APS 1 to 6 levels had the highest proportion of employees being managed for underperformance. For all eight agencies, there were no SES employees managed under formal underperformance processes.

Table 2.4: Formal underperformance processes by classification, 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Agency |

APS |

EL |

SES |

APS |

EL |

SES |

|

|

Percentage of ongoing employees Stage 2 |

Percentage of ongoing employees Stage 3 |

||||

|

AGDa |

0.36 |

0.24 |

0.00 |

0.29 |

0.19 |

0.00 |

|

ATO |

0.55 |

0.17 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

DAWR |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

|

DIISb |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0.15 |

0.28 |

0.00 |

|

DSS |

0.15 |

0.14 |

0.00 |

0.12 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

|

DVAa |

0.14 |

0.17 |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

IPd |

0.19 |

0.00 |

NA |

0.13 |

0.15 |

0.00 |

|

NFSA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0.35 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Note: NA means data is not available.

Note a: AGD and DVA did not have full records of stage 2 processes so the data for stage 2 underestimates the actual number.

Note b: DIIS provides general guidance for managers around stage 2 but no specific procedures are prescribed.

Note c: The performance of IP Australia’s SES employees is managed by DIIS. IP Australia streamlined stage 2 and 3 in July 2016 as part of a new performance management scheme. Data refers to previous scheme.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

Alternatives to underperformance management processes

2.13 While the proportion of staff in formal underperformance processes is very low, agencies also manage underperformance through other means. Most agencies (except IP Australia and the NFSA) have made some use of redundancies to target poorly performing non-SES staff. In addition there are provisions under the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) that allow agencies to offer SES employees an incentive to retire where the employee no longer has the skills to perform at their SES classification.

Redundancies

2.14 The majority of the eight agencies over the four year period examined in the audit have been required to manage significant excess staffing situations and concomitant large scale redundancies due to a diverse range of circumstances. Table 2.5 indicates that three agencies (DSS, NFSA and the ATO) managed the redundancy of an average of over five per cent of their ongoing staff in each of the four years 2012–13 to 2015–16. Where there are excess staff, agencies must act in accordance with the APS employment framework, which includes the PS Act, the APS Bargaining Framework and agency enterprise agreements. The APSC has also issued guidelines24 that require agencies to offer voluntary redundancies strategically to ensure retention of employees who are highly valued and have the skills needed for future work of the agency. The guidelines explicitly state that agencies should not use excess staff arrangements as an alternative to dealing with underperformance.

2.15 Table 2.5 indicates that all agencies with the exception of NFSA and IP Australia have provided redundancies to staff who were rated as less than effective in the performance cycle prior to receiving their redundancy (data was unavailable for DIIS). This practice in AGD was particularly high with 17.5 per cent of those staff taking redundancies having been rated less than effective. AGD, DSS, ATO, and DAWR have a higher proportion of ongoing employees who have been rated as less than effective who have received a redundancy than the proportion of ongoing employees who have been managed in stage 3 of their formal underperformance procedures (that is comparing column 5 in Table 2.5 and column 5 in Table 2.3).

Table 2.5: Redundancies, 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Agency |

Total redundancies over four yearsa |

Average annual percentage of staff receiving redundancies |

Percentage of redundant staff rated less than effectiveb |

Percentage of total staff rated less than effective and made redundantb |

|

DIIS |

503 |

4.4 |

NA |

NA |

|

IP |

26 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

|

NFSA |

48 |

6.5 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

|

DVA |

118 |

1.6 |

2.9 |

0.03 |

|

ATO |

4086 |

5.5 |

3.1 |

0.12 |

|

DAWR |

572 |

3.2 |

4.5 |

0.14 |

|

DSS |

655 |

6.9 |

8.2 |

0.37 |

|

AGD |

240 |

4.8 |

17.5 |

0.74 |

Note a: Includes SES incentives to retire.

Note b: Calculations only use employees whose performance ratings were known. DIIS was unable to provide performance rating data for any redundant employees but advised that it does not offer redundancy to employees rated as less than effective; AGD was unable to provide performance rating data for 12.1 per cent of redundant employees; ATO 24.7 per cent; DAWR 6.8 per cent; DVA 42.4 per cent; and IP Australia 19.2 per cent.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

2.16 Given the finding that underperforming staff are not always accurately identified in performance management processes, the data in Table 2.5 understates the use of redundancies as a way of managing underperforming staff. All agencies, except DIIS, advised that in excess staffing situations, after inviting employees to register expressions of interest for redundancies, as required in the provisions of their enterprise agreements, agencies then decide on who will be made an offer, taking into account a range of factors including an assessment of relative performance. Staff who may be underperforming but have been inaccurately rated as effective by managers would be generally included in those offered redundancies. DIIS advised that when it determines which staff are excess to requirements it either identifies staff whose functions are no longer required or conducts a skills and capability review with emphasis on retaining valued staff with the skills required for future work.

2.17 The ATO actively uses a clause in its enterprise agreement that states staff will be declared excess that cannot be effectively used because of technological or other changes, or changes in the nature, extent or organisation of the functions of the agency. These are called ‘non bona fide’ redundancies indicating that it is not the position that is redundant rather it is related to the employee. Table 2.6 indicates that these redundancies are commonly used, accounting for 13.1 per cent of all ATO redundancies over the four year period from 2012–13 to 2015–16. Table 2.6 shows that an annual average of 0.7 per cent of ongoing employees received a non bona fide redundancy over the period 2012–13 to 2015–16 compared to 0.03 per cent of employees being managed under stage 3 underperformance process over the same period (see Table 2.3), indicating that the ATO has used non bona fide redundancies significantly more than formal underperformance procedures.

Table 2.6: ATO redundancies, 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Financial year |

Average staffing level |

Total redundancies |

Non bona fide redundancies |

Percentage of non bona fide redundancies in total redundancies |

Percentage of non bona fide redundancies in total ongoinga staff |

|

2012–13 |

21 440 |

151 |

58 |

38.4 |

0.3 |

|

2013–14 |

22 022 |

860 |

128 |

14.9 |

0.6 |

|

2014–15 |

19 068 |

2369 |

204 |

8.6 |

1.1 |

|

2015–16 |

18 482 |

706 |

147 |

20.8 |

0.8 |

|

Total/ average |

20 253 |

4086 |

537 |

13.1 |

0.7 |

Note a: Includes SES employees to enable comparison with Table 2.3.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by the ATO.

2.18 In some circumstances it is a cost-effective decision for agencies to make redundancy payments to underperforming employees particularly in situations of excess staffing. Even outside of situations of excess staffing, in some complex cases and/or when circumstances require prompt action, the costs, including the time and effort involved in managing an employee through underperformance procedures, may be in excess of the costs of offering a redundancy.25 In general, however, redundancies should not be used to replace or undermine ongoing, robust underperformance management procedures. It can be uneconomic, create perverse incentives as well as causing resentment in better performing employees.

Incentives to retire for SES employees

2.19 Agency Heads have the discretion to offer a SES employee an incentive to retire under section 37 of the PS Act. APSC policy advice states that such incentives may be offered in a number of limited circumstances which include where the SES employee no longer has the skills to perform at their SES classification (in contrast to the APSC advice that voluntary redundancies should not be used as an alternative to dealing with underperforming non-SES employees). The ANAO has estimated that of the 3.3 per cent of all APS SES employees that received an incentive to retire on average in each of the four years 2011–12 to 2014–15, around one third of them were received on the basis that the SES employee no longer had the skills to perform at their SES classification. This data broken down for the eight agencies in the audit is not available.

2.20 Incentives to retire should be used sparingly in circumstances where the SES employee no longer has the skills to perform at their SES classification. In such circumstances consideration should be given to the fact that underperformance management procedures for SES employees should be less time consuming and complex as SES employees do not have access to unfair dismissal provisions.

Outcomes of underperformance processes

2.21 Table 2.7 presents outcomes for the employees who have been managed under stage 2 and stage 3 underperformance processes. For the five agencies that could provide data on outcomes for stage 2 processes, the outcomes varied among agencies, although there were significant proportions of staff reported as having been able to improve performance to effective levels in all five agencies. For employees in stage 3 processes, in most agencies a majority of staff either left the agency via redundancy (17.4per cent), resignation or retirement (19.6 per cent), with only 13.0 per cent of staff having their employment terminated. Only 17.4 per cent of employees in stage 3 processes were reduced in classification. A small number of employees were able to transfer to other agencies (4.3 per cent) during stage 3 and some employees were reported as being able to improve their performance even in stage 3 (for example 28 per cent in the ATO).

Table 2.7: Outcomes of underperformance processes

|

Outcome |

ATO |

AGD |

IP |

NFSA |

DSS |

DIISa |

DAWR |

DVA |

All agencies |

|

Stage 2 |

Percentage of employees in stage 2 processes subject to respective outcome |

||||||||

|

Dealt with as medical issue |

10.1 |

|

|

|

7.7 |

|

|

9.1 |

9.5 |

|

Machinery of Government change |

|

7.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.3 |

|

Move to next formal stage |

6.7 |

35.7 |

|

|

61.5 |

|

|

36.4 |

10.3 |

|

New role within agency |

7.8 |

|

|

|

7.7 |

|

|

9.1 |

7.5 |

|

Performance improvement |

52.2 |

28.6 |

33.3 |

|

23.1 |

|

|

45.5 |

49.9 |

|

Redundancy (involuntary/voluntary) |

14.8 |

14.3 |

33.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

14.1 |

|

Resignation |

4.3 |

7.1 |

16.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

4.4 |

|

Otherb |

4.1 |

7.1 |

16.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

4.1 |

|

Total number in stage 2 process |

345 |

14 |

6 |

|

13 |

|

|

11d |

389 |

|

Stage 3 |

Percentage of employees in stage 3 processes subject to respective outcome |

||||||||

|

Dealt with as medical issue |

8.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.2 |

|

Machinery of Government change |

|

|

|

|

|

13.0 |

|

|

3.3 |

|

Performance improvement |

28.0 |

|

|

|

|

17.4 |

33.3 |

|

16.3 |

|

Reduction of classification |

4.0 |

16.7 |

33.3 |

|

44.4 |

8.7 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

17.4 |

|

Redundancy (involuntary/voluntary) |

20.0 |

25.0 |

|

100 |

11.1 |

21.7 |

|

|

17.4 |

|

Resignation or retirement |

20.0 |

41.7 |

33.3 |

|

22.2 |

8.7 |

|

66.7 |

19.6 |

|

Termination |

12.0 |

16.7 |

16.7 |

|

11.1 |

13.0 |

16.7e |

|

13.0 |

|

Transfer to other APS agency |

|

|

16.7 |

|

|

13.0 |

|

|

4.3 |

|

Otherc |

8.0 |

|

|

|

11.1 |

4.3 |

16.7 |

|

6.5 |

|

Total number in stage 3 process |

25 |

12 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

23 |

12 |

3 |

92 |

Note: Percentage totals may not add to 100 due to rounding. IP Australia streamlined stage 2 and 3 in July 2016 as part of a new performance management scheme. Data refers to previous scheme.

Note a: DIIS was unable to provide data on all outcomes for employees undergoing stage 3 processes. Data on outcomes for employees rated unsatisfactory was used instead. Some of these employees whose outcome was ‘redundancy’ may have returned to satisfactory performance before the redundancy was taken as it is DIIS’ policy that no employees undergoing formal underperformance processes should be offered redundancies, but this data is unavailable.

Note b: Includes: dealt with as misconduct; none; promotion to other area; termination; and transfer to other APS agency.

Note c: Includes: dealt with as misconduct; new role within agency; and none.

Note d: DVA did not have complete records of stage 2 processes so the data for stage 2 underestimates the actual number.

Note e: One employee who was terminated was as a result of underperformance processes was later reinstated to their position.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

Probation

2.22 The PS Act provides that agencies may impose conditions of engagement, one of which is probation.26 The probationary period is an important part of the recruitment and selection process of new employees. It provides an opportunity to confirm an employee’s suitability to the agency and job, for both the employer and the employee. Action to cease employment during probation is a legitimate action which recognises that not all selection decisions result in an outcome that is right for the employer or the employee. It is important that agencies use this period proactively to manage any performance issues that may arise.27 If performance issues cannot be fully resolved, the employee’s ongoing employment should not be continued. APS employees in the first six months of their employment are not eligible to lodge an unfair dismissal claim with the Fair Work Commission although key procedural fairness provisions still apply. While probationary employees may apply for a review of actions under the PS Act of a performance management outcome, the review rights lapse once their employment ceases. A review application does not stay any proposed action by an agency, for example, an agency would not be obliged to extend employment to allow a review to be finalised.

2.23 All agencies except AGD routinely apply probation to all new ongoing employees, excluding ongoing transfers and promotions between agencies.28 AGD only systematically imposes probation as a condition of engagement on entry level program employees, for example, graduates. It is important that agencies impose probation on all new engagements because probationary employment should be terminated where performance issues arise and cannot be resolved.

2.24 Two agencies (ATO and DIIS) have automated the probation process and another (IP Australia) is in the process of doing so to help ensure that performance assessments are completed within the probationary period. In five agencies (DAWR, DSS, DVA, IP Australia and NFSA), there is central oversight of probation processes with reminder emails sent to managers at the appropriate review points. AGD has central oversight but advised that there were issues regarding the usefulness of probation reports, in particular, the accuracy of performance assessments.

2.25 Table 2.8 presents data on the percentage of employees on probation over the four year period 2012–13 to 2015–16 who left their agency during their probation period. While probationary employees leave for a variety of reasons, one of these is for underperformance. It is not possible to draw firm conclusions from the data in Table 2.8 on how actively agencies are using probation as a mechanism to test the suitability of employees because low separations for employees may reflect superior recruitment processes rather than low use of probation to test the suitability of new employees. The data indicates however that managers in the NFSA and ATO, and to a lesser extent IP Australia, are actively using the probation period to manage underperformance. In combination with information on agencies’ procedures, the data suggests that the majority of agencies are not using probation to robustly assess performance to test job fit and the appropriateness of recruitment decisions. As mentioned in Chapter 4, the outcomes of probation in this context should be included in periodic management reporting on performance management.

Table 2.8: Percentage of employees on probation who left during their probation period for performance related reasons, 2012–13 to 2015–16

|

Agency |

Total number of probationary employees |

Total number of probationary employees who separated |

Number of probationary employees with performance issues who separated |

Probationary employee separations with performance issues as a percentage of all probationary employees |

|

AGD |

139 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

ATO |

2 022 |

279 |

67 |

3.3 |

|

DAWR |

462 |

79 |

NA |

NA |

|

DIIS |

83 9 |

1 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

DSS |

570 |

18 |

1 |

0.2 |

|

DVA |

395 |

9 |

1 |

0.3 |

|

IP |

244 |

8 |

3 |

1.2 |

|

NFSA |

52 |

5 |

2 |

3.8 |

Note: NA means data is not available. DAWR was unable to extract this data from their data systems.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by agencies.

Comcare claims, reviews of actions and unfair dismissal claims