Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Compliance with Visa Conditions

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s (DIBP) management of compliance with visa conditions. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO assessed whether DIBP:

- effectively manages risk and intelligence related to visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions;

- promotes voluntary compliance through targeted campaigns and services that are appropriate and accessible to the community;

- conducts onshore compliance activities that are effective and appropriately targeted; and

- has effective administrative arrangements to support visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australia’s migration programs allow people from any country to apply for a visa1 to migrate to Australia or to enter the country on a temporary basis, regardless of their ethnicity, culture, religion or language, provided that they meet the criteria set out in law. The Migration Act 1958 and associated regulations provide the legislative framework for the administration of Australia’s migration and temporary visa programs; and impose a range of conditions on people issued with a visa, including the duration of their stay and activities they can undertake while in Australia.

2. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) is the policy, program and service delivery entity with responsibility for the administration of Australia’s migrant, temporary visa and citizenship programs. It is also responsible for the security of Australia’s borders through the management of people and goods that cross them. One of the department’s key responsibilities is to manage visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions.

3. The administration of migration and visa arrangements is a complex area of public service delivery, with over 7.5 million visas being granted in 2014–15 to people travelling from all over the world.2 Arrangements supporting visa administration have undergone significant change in the last ten years, most recently through the integration of the department with the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service and establishment of the Australian Border Force within the department, taking effect from 1 July 2015.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s management of compliance with visa conditions. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO assessed whether DIBP:

- effectively manages risk and intelligence related to visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions;

- promotes voluntary compliance through targeted campaigns and services that are appropriate and accessible to the community;

- conducts onshore compliance activities that are effective and appropriately targeted; and

- has effective administrative arrangements to support visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions.

Conclusion

5. There are weaknesses in almost all aspects of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s arrangements for managing visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions, including in key corporate functions that support the administration of Australia’s migration and visa programs. These weaknesses undermine the department’s capacity to effectively manage the risk of visa holders not complying with their visa conditions—from simple overstaying through illegal working to committing serious crimes.

6. Over the last decade, the department has introduced a series of restructures and reforms designed to address the weaknesses, but there is little evidence of overall improvement, not least as a result of the continual change, with initiatives seldom fully implemented or evaluated. As at July 2015, key aspects of the management of visa compliance examined in this audit were under review by DIBP as part of its integration and reform agenda, and a range of initiatives are intended to address the administrative weaknesses identified in this audit. However, the challenges facing the department should not be underestimated given the extent of the reforms and the longstanding nature of the problems.

Supporting findings

Managing risk and intelligence

7. DIBP does not have comprehensive information about the nature and extent of visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions. For overstayers, data matching provides information on the number of people who have exceeded the allowable duration of their visa. In contrast, the extent of non-compliance with other visa conditions, for example visa holders working illegally, is not well understood. Improvements in the capture and use of the results of compliance related activities would assist the department in developing an overarching perspective of non-compliance.

8. The department does not currently have an effective risk and intelligence function supporting visa compliance. In December 2014, the department’s Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division, established in 2010 to better coordinate and integrate risk and intelligence functions across the department, was abolished, and the functions dispersed to areas across the department and to the Australian Border Force. As at September 2015, DIBP was undertaking a series of reviews of these dispersed functions, to determine its medium to long term approach to managing risks to the integrity of Australia’s migration and visa programs. The functions are to be subject to another restructure within some four years, and significant effort will be required to fully implement the revised arrangements.

Promoting and supporting voluntary compliance

9. DIBP’s information about visa entitlements and conditions is readily accessible to visa holders and the general public, including through social media and on-line and mobile delivery, with the department also providing access to interpreting services and information products in several languages.

10. An external evaluation of the services supporting voluntary compliance, finalised in December 2012, concluded that the services met the objective of reducing the time to resolve clients’ visa status, and reduced the overall caseload. The evaluation report also identified weaknesses in aspects of the administration of the services, and included 13 recommendations relating to, among other things, the governance of the services and the lack of key performance indicators. As at June 2015, the report and its recommendations had not been fully considered by the department, and consequently there is no assurance that weaknesses identified in the report have been addressed.

11. There are shortcomings in DIBP’s management of stakeholder engagement, primarily relating to the lack of a corporate approach and limited analysis of client feedback. To address these shortcomings, the department has recently consolidated its communications and media functions (that were previously fragmented across different areas of the department) in order to provide a coordinated and consistent approach to stakeholder engagement; and commenced the development of a corporate stakeholder engagement plan. A project is underway to improve the department’s management of client feedback.

Visa cancellations and compliance

12. DIBP has well established arrangements to manage the cancellation of visas, including through the introduction of a more efficient business model for visa cancellation teams in early 2015. However, the department has identified the lack of a defined and consistent approach for measuring, monitoring and reporting on the levels of fraud and risk in the visa and citizenship caseload. As at September 2015, a new Caseload Assurance Framework was being developed, which aims to provide a higher level of confidence that known and emerging risks in the visa caseload are managed effectively.

13. The operations of compliance field teams are not well managed. There are weaknesses in almost all aspects of the operations, including the management of information as to which field activities would be undertaken; ad hoc and insufficient use of management reports; an absence of appropriate performance indicators to assess the efficiency or effectiveness of the activities; and variations in the structure and operation of the teams across states and territories. From 1 July 2015, the teams were integrated with similar functions from the (previous) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service under a regional command structure, and a new operating model for the Australian Border Force was being developed.

Administrative arrangements

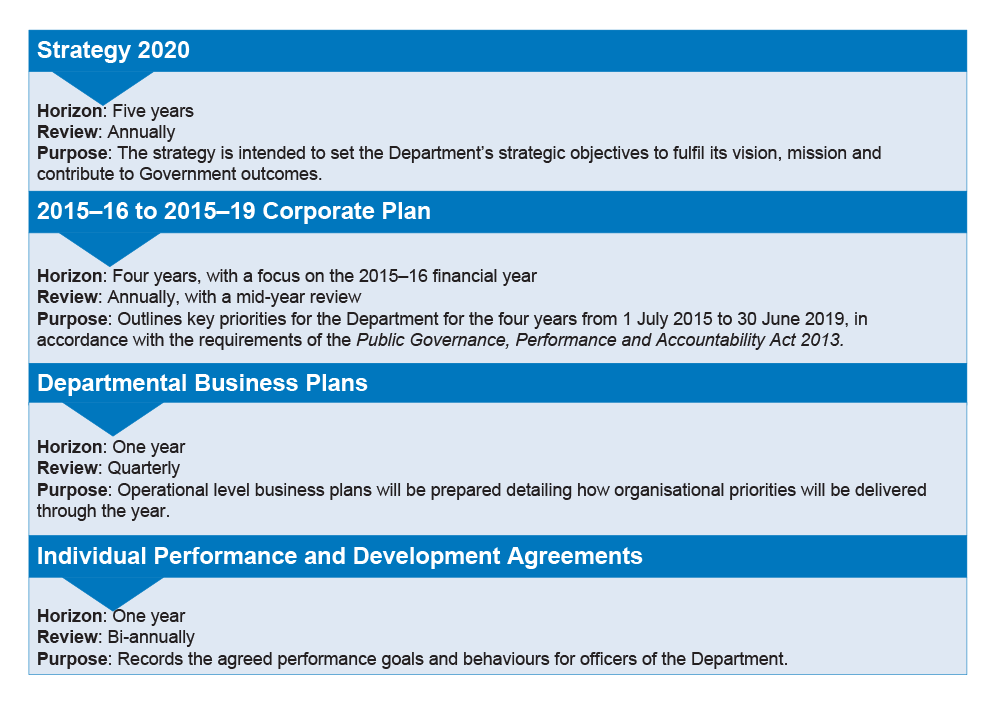

14. DIBP is currently developing and implementing a range of measures to support the integration and reform agenda, including the rollout of a new governance, planning and reporting framework. Actions taken by the department in the period 2012–15 to address issues relating to the department’s governance and planning functions, identified in the Australian Public Service Capability Review 2012, have been overtaken by the new arrangements, with a substantial program of work required to fully implement the new processes.

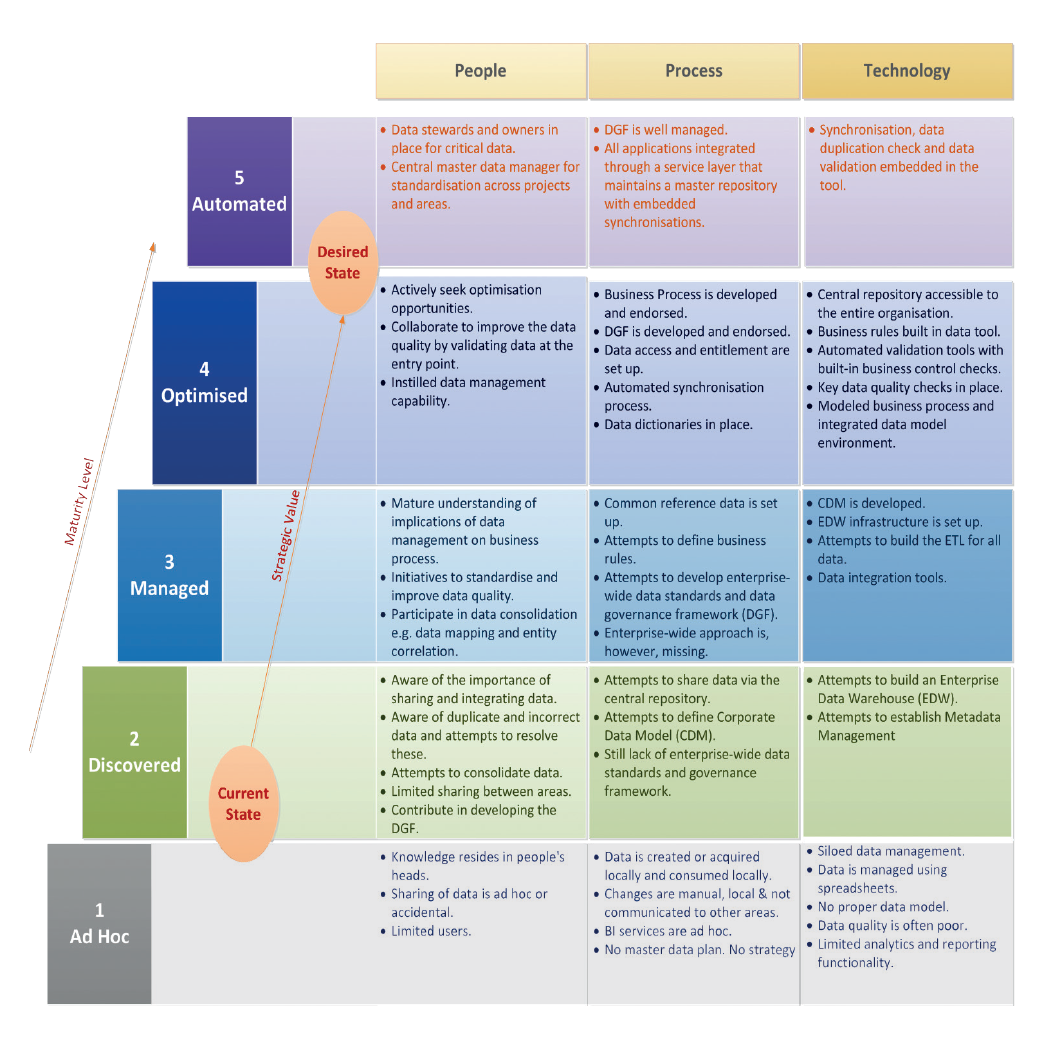

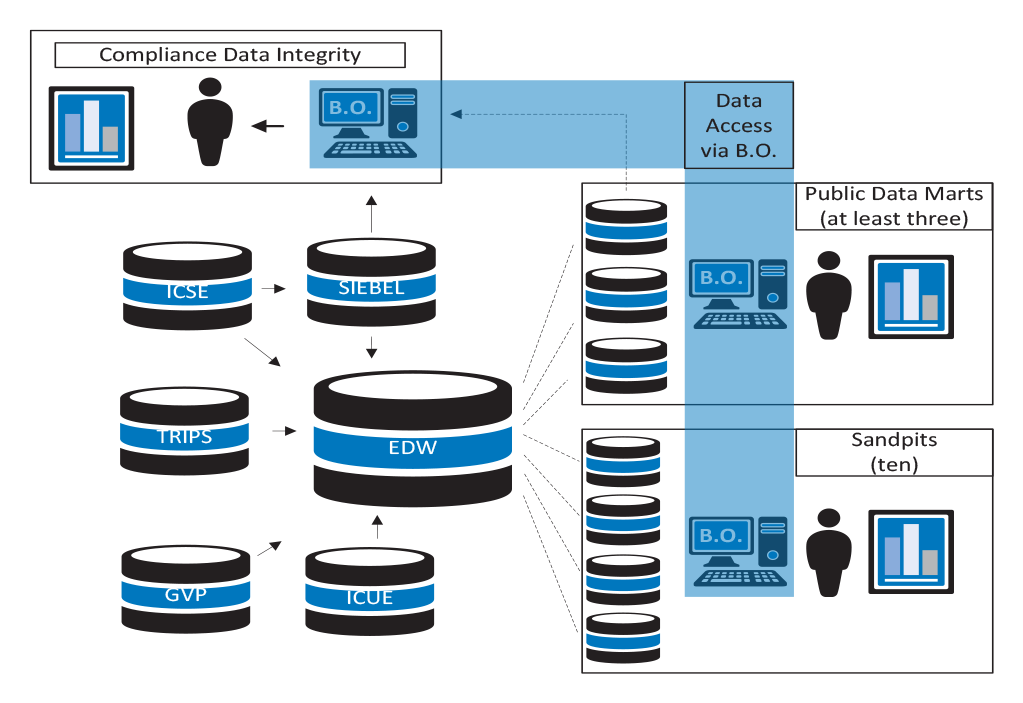

15. Appropriate governance arrangements and management oversight of the department’s data, including visa related data, has been lacking over many years. The most recent initiative to improve data quality, a Data Governance Working Group, was discontinued in October 2014, just a few months after it had been established. The department’s capability to capture data and provide reports on most aspects of the administration of migration and visa programs is flawed, with key reports on compliance typically including caveats as to the accuracy of the data. Funding provided under the integration and reform agenda supports a program of work to improve data management and reporting.

16. There are weaknesses in four key corporate functions supporting visa compliance. The department does not have appropriate arrangements for the development and management of the Memoranda of Understanding and other agreements that support the exchange of information and services with other state, territory and Australian Government entities. DIBP does not provide staff with policy and procedural guidance in a format that is readily accessible and up-to-date, and a review of the department’s learning and development capability indicated room to improve all aspects of the function. DIBP’s internal audit reports have identified extensive shortcomings in its capacity to provide a level of assurance, through the implementation of quality management tools and processes, that the department’s decisions and activities are consistent and meet the requirements set out in its policies and procedures. Problems with DIBP’s electronic records management system have been identified for many years, but not addressed. The system now presents a risk to the department as records are difficult to locate or cannot be found.

Future arrangements

17. The department is now in the second year of a transition to integrate DIBP with the (former) Australian Customs and Border Protection Services, involving significant administrative, structural and cultural changes. The establishment of a new operating model for the Australian Border Force, outlined in Appendix 3, aims to leverage intelligence and operational capacity from the integrated entities. Similarly, there should be synergies in the joint intelligence and risk capabilities, with reviews currently underway to determine the medium to longer term arrangements for these functions, outlined in Appendix 2.

18. The department’s integration and reform agenda also supports numerous projects, initiatives, working groups and task forces to integrate and improve the functions supporting the administration of visa compliance, with full implementation of the new arrangements due by 1 July 2016.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 2.4 |

To inform compliance strategies and activities for the migration and visa programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection improves its data collection and analysis activities, to gain an overarching perspective on the extent and nature of non-compliance with visa conditions. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Para 2.29 |

To improve the management of allegations concerning possible non-compliance with visa conditions, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Para 4.36 |

To support the delivery of compliance activities in line with legislative and procedural requirements, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection mandates and monitors the appropriate documentation of visa compliance activities, including but not limited to the:

DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Para 5.47 |

To support the effective delivery of compliance activities under the migration and visa programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection implements initiatives for key supporting governance functions (quality assurance, guidance materials, training, performance reporting and record keeping), with:

DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (the Department) acknowledges the findings outlined in the report and accepts all four recommendations.

Considerable work is underway in streamlining the new operating environment following the integration of the former Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, and the establishment of the Australian Border Force on 1 July 2015. The Department is reviewing a number of administrative functions related to managing visa compliance including a review of allegation assessments and compliance processes, intelligence capacity and information management systems. The Department also has a number of broader strategic initiatives underway to address the recommendations in the report including the development of the Information Environment Strategy and the implementation of the ABF operational model and risk management framework.

1. Background

Overview

1.1 Australia’s migration programs allow people from any country to apply for a visa3 to migrate to Australia, regardless of their ethnicity, culture, religion or language, provided that they meet the criteria set out in law. A range of temporary visas also supports people travelling to Australia for specific purposes, including taking up employment, or for training and education purposes. Through the Humanitarian Program, people assessed as refugees may be issued with a visa and be allowed to live permanently in Australia. The number of migration and humanitarian visas issued each year is capped, while temporary visas are demand driven.

1.2 As at 30 June 2015, there were 134 visa classes with 233 associated subclasses across the four categories of visas that support people visiting, studying, working and living in Australia.4 Over 7.5 million visas were granted in 2014–15. The number of visas granted under the largest five visa programs in the period 2010–11 to 2014–15 is set out in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Number of visas granted by type, 2010–11 to 2014–15

|

Visa Type |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Visitor |

3 543 883 |

3 561 794 |

3 753 819 |

3 993 406 |

4 311 498 |

|

Student |

251 554 |

254 166 |

260 303 |

293 223 |

300 963 |

|

Migration Program |

168 685 |

184 998 |

190 000 |

190 000 |

189 097 |

|

Temporary Worker (457) |

90 119 |

125 070 |

126 350 |

98 571 |

96 084 |

|

Humanitarian |

13 799 |

13 759 |

20 019 |

13 768 |

13 756 |

Source: Department of Immigration and Citizenship and Department of Immigration and Border Protection Annual Reports for 2010–11 to 2013–14, and information provided by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection for 2014–15.

1.3 The Migration Act 1958 and associated regulations provide the legislative framework for the administration of Australia’s migration and temporary visa programs; and impose a range of conditions on people issued with a visa, including the duration of their stay and activities they can undertake while in Australia. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP)5 is the policy, program and service delivery entity with responsibility for the administration of Australia’s migrant, temporary visa and citizenship programs. It is also responsible for the security of Australia’s borders through the management of people and goods that cross them. One of the department’s key responsibilities is to manage visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions.

Managing visa compliance

1.4 Visa holders are acting unlawfully where they do not comply with the conditions of their visas, for example by taking up employment where their visa class does not entitle them to do so, and/or by not leaving the country when their visa has expired or has been cancelled (and consequently they have no legal status to remain in Australia—referred to as unlawful non-citizens).

1.5 In relation to the management of visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions, DIBP has typically differentiated between:

- maintaining the integrity of visa programs, whereby visas are only granted to genuine applicants, and visas may be cancelled where visa holders are found to be non-compliant;

- visa status resolution services, where people whose visas have expired are encouraged to voluntarily engage with the department to seek a resolution to their status6; and

- compliance field operations, where teams of compliance officers identify unlawful non-citizens living in the community, and those who are working illegally.

1.6 The integrated nature of these measures has been recognised by DIBP, with the department advising that:

what happens offshore can play a crucial role in determining the impact of migration onshore. What happens in our visa decision making and integrity checking processes affect compliance activities in the field, and vice versa. Thus, working across integrated business functions is vital to achieving timely outcomes for our clients and the success of all our programs.7

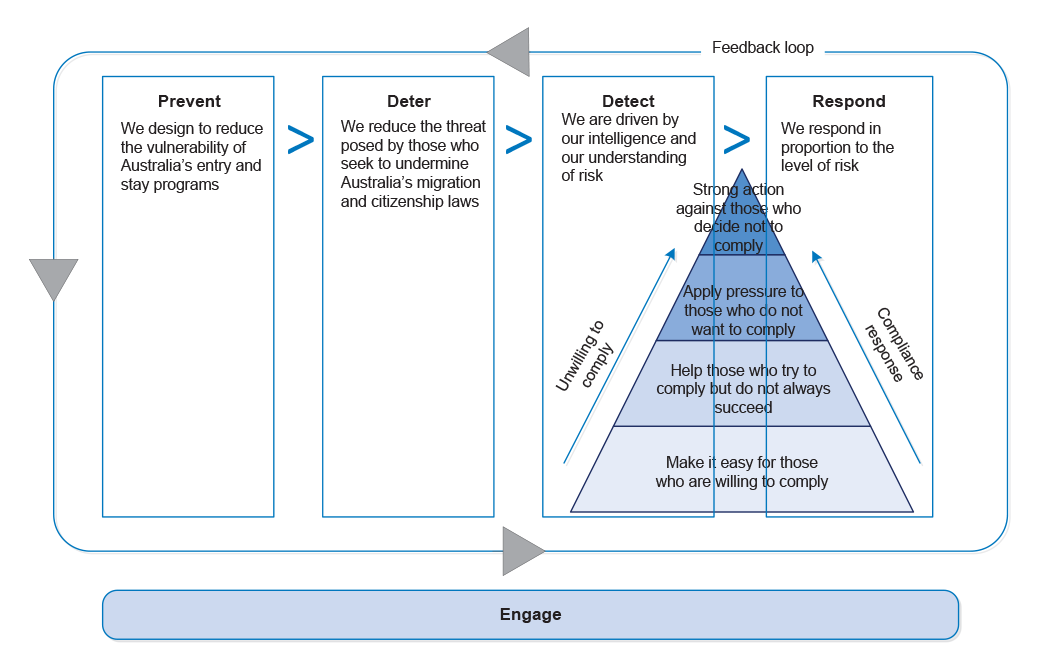

1.7 Consistent with this approach, the department’s Compliance Strategy 2012–15 was based on engagement across the various measures of compliance, with a ‘feedback loop’ established between them.

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s administrative arrangements for visa compliance

1.8 From 1 July 2015, the structure of DIBP reflects a single agency, following integration with the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, and the establishment of the Australian Border Force (ABF)—a single frontline operational border agency with statutory responsibilities to enforce customs and immigration laws—within the department.8 The timeline for the integration of the agencies was set out in Portfolio Budget Statements 2014–15 for the Immigration and Border Protection portfolio:

During financial years 2014–15 and 2015–16, DIBP and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Services (ACBPS) will progressively transition into a single Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

1.9 Over the course of the audit, the structure of the department was evolving as functions in the respective agencies were integrated throughout the first year of the transition. The structure of the department, including the ABF, as at September 2015, is shown Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: DIBP organisation chart, as at September 2015

Note: ABF: Australia Border Force. OSB JATF: Operation Sovereign Borders Joint Agency Task Force.

Source: ANAO from departmental information.

1.10 The department is headed by a portfolio secretary and the ABF by a commissioner, a statutory appointment. The secretary reports directly to the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (the Minister); and the commissioner reports to the Minister on ABF operational matters, and liaises with the secretary with regard to the corporate and support functions provided by DIBP. The ABF Commissioner also holds the role of Comptroller General of Customs, with responsibility for enforcement of customs laws and collection of border related revenue.

Administrative arrangements supporting visa compliance

1.11 Within the new structure, functions that are largely concerned with program integrity and visa status resolution are carried out within the department, and compliance field teams are located in the Australian Border Force. In developing the new structure, DIBP guidance on visa compliance related roles and responsibilities of the department was that:

activity which primarily supports visa decision making should sit within the Visa and Citizenship Service Group (VCSG) and activity that is primarily compliance or enforcement in nature should sit in the ABF. While there may be nuances, the split of responsibility largely seeks to place any activity requiring law enforcement type responses, such as warrants or detention of individuals, within the ABF…Senior executives with responsibility for the various functions will need to work very closely…to ensure joined up operational activity.9

1.12 This new structure has not yet resulted in significant change to the systems and processes supporting visa compliance, other than for the management of risk and intelligence, where key elements have been transferred to different areas of the new department. Significant changes to the business model are to be developed and implemented throughout 2015–16, including a new operational model for front line compliance activities in the Australian Border Force; and a major review of the department’s risk and intelligence functions.

Extent of departmental review and reform

1.13 The new arrangements represent significant reform in the operations of the department, with the entities’ Plan for Integration–February 2015 stating that it was not just a structural change, but a ‘change in philosophy, approach and accountability’. The reforms have also been accompanied by a significant turnover of DIBP’s Senior Executive Staff.10

1.14 This is the third major reform the department has experienced in less than a decade, including having three different departmental secretaries, precipitated by several high profile reviews in 2005–06, two of which are typically referred to as the Palmer and Comrie reviews11:

- in 2005–06, the Secretary of the (then) Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs introduced a comprehensive agenda of reform and improvement; and

- in 2009–10, the Secretary of the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship announced an ‘ambitious transformation strategy to strengthen Australia’s borders through the delivery of world class migration, visa and citizenship services’, to be rolled out over five years from 2009–10 to 2013–14.12

1.15 Some three years later, a review of the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s leadership, strategy and delivery capabilities conducted by the Australian Public Service Commission, the Australian Public Service Commission Capability Review 2012, noted that the department’s internal focus in recent years had been on making the necessary changes in response to the findings in the 2005 Palmer and Comrie reports, and that this had involved:

repeated structural changes, changes to process, changes to senior personnel, changes to ICT and other systems, and a sustained effort to change culture. However, in the review team’s view, the department has been only partially successful in developing control mechanisms to reduce the risk of future failures of process.13

1.16 A follow up ‘health check’ conducted by the Australian Public Service Commission in 2014 reported evidence of capability improvement, particularly in terms of the positive impact of the department’s leadership. Initiatives underway in response to the review (and as part of the five-year transformation strategy) have been overtaken by the current integration and reform process. A timeline of major departmental reviews and reforms is set out in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of major departmental reviews and reforms

Note: DIMA (Departmental of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs), DIAC (Department of Immigration and Citizenship), and ACBPS (Australian Customs and Border Protection Service).

Source: ANAO.

1.17 In addition to the reviews and reforms, the numbers of illegal maritime arrivals have resulted in considerable media and community scrutiny of the operations of the department over recent years. Managing these arrivals has provided substantial challenges, additional pressures and increased workload for DIBP, while maintaining ‘business as usual’ operations.14

Previous audits

1.18 The ANAO has undertaken a number of related performance audits with regard to compliance with visa obligations, including:

- Audit Report No. 47 2014–15, Verifying Identity in the Citizenship Program, Department of Immigration and Border Protection; and

- Audit Report No. 46 2010–11, Management of Student Visas, Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

1.19 These audits found significant shortcomings in key governance structures and processes, including the need to provide clear guidance to decision-makers, develop a risk-based quality assurance program, and develop and report against performance indicators that assess the quality of decisions.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s management of compliance with visa conditions.

1.21 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high‐level criteria. The audit assessed whether DIBP:

- effectively manages risk and intelligence related to visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions;

- promotes voluntary compliance through targeted campaigns and services that are appropriate and accessible to the community;

- conducts onshore compliance activities that are effective and appropriately targeted; and

- has effective administrative arrangements to support visa holders’ compliance with their visa conditions.

1.22 The audit focused on visa compliance activities, including the: management of risk and intelligence; promotion and support of voluntary compliance; and visa cancellation and field activities. It did not address DIBP’s processes in issuing visas. While the audit did not examine the substantial administrative reforms resulting from the integration of the department and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, the impact of these reforms on the existing administrative arrangements for visa compliance were acknowledged.

1.23 In conducting the audit, the ANAO: examined DIBP’s policy documents, procedures, operational reports and information technology systems; interviewed relevant departmental staff; conducted field work in the department’s state and territory offices; and analysed a sample of compliance field cases.

1.24 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $767 000.

2. Managing risk and intelligence

Areas examined

This chapter examines DIBP’s arrangements for managing the risk of visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions.

Conclusion

DIBP has a good understanding of the number of people who overstay the duration of their visa and do not leave the country when they are required to do so. The levels of non-compliance with other visa conditions, including whether a visa holder is working illegally, are less well understood, and the department undertakes little work to capture and analyse the results of compliance activities.

In December 2014, as part of the new integration and reform agenda, DIBP abolished the arrangements supporting risk and intelligence that had been in place since 2010. Risk functions are now dispersed across the department and in the Australian Border Force. As at September 2015, the department had commissioned several reviews of its risk and intelligence functions, but in the meantime there was no coordinated risk framework or process for visa compliance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at enabling DIBP to gain an overarching perspective of the extent of non-compliance with visa conditions, and improving the management of allegations concerning possible non-compliance with visa conditions.

Is the nature and extent of non-compliance with visa conditions well understood?

DIBP does not have comprehensive information about the nature and extent of visa holders’ non-compliance with their visa conditions. For overstayers, data matching provides information on the number of people who have exceeded the allowable duration of their visa. In contrast, the extent of non-compliance with other visa conditions, for example visa holders working illegally, is not well understood. Improvements in the capture and use of the results of compliance related activities would assist the department in developing an overarching perspective of non-compliance.

2.1 Understanding the nature and extent of visa holders’ non-compliance underpins the development of effective measures to prevent and respond to it. While DIBP can readily identify the people who have overstayed their visa (including those who have overstayed for a considerable time, as set out in Table 2.1)15, other measures of non-compliance are more difficult to determine.

Table 2.1: Length of time people have overstayed their visa, 30 June 2011 to 30 June 2015

|

Length of overstay |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

1 month or less |

1 770 |

1 580 |

1 460 |

1 400 |

1 420 |

|

1 month to 1 year |

11 110 |

10 490 |

9 840 |

9 100 |

8 740 |

|

1 year to 5 years |

16 640 |

19 200 |

20 850 |

20 030 |

18 900 |

|

5 years to 15 years |

15 390 |

15 210 |

15 240 |

15 350 |

15 550 |

|

15 years or more |

13 540 |

14 420 |

15 280 |

16 210 |

17 370 |

|

Total |

58 450 |

60 900 |

62 670 |

62 090 |

61 980 |

Source: DIBP Programme Analysis Report, December 2014, and from DIBP for 2014–15.

2.2 The information that DIBP captures in relation to non-compliance (other than overstaying) is obtained largely from those who have been detected through visa cancellation and compliance field activities. However, the department does not capture all the available information (for example, the rationale for visa cancellation, such as the fraud type or breach of visa condition), and for compliance field activities, the information collected by DIBP relates primarily to the compliance activity, such as the source of allegations for new cases.

2.3 The department has also not used the data that it has collected to estimate the overall quantum of non-compliance with visa conditions, which covers both overstayers and those visa holders not complying with other visa conditions. The absence of this overarching perspective on visa non-compliance makes it more difficult for the department to develop a risk-based compliance regime and to effectively identify and manage the risks to the integrity of the migrant and temporary visa programs.

Recommendation No.1

2.4 To inform compliance strategies and activities for the migration and visa programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection improves its data collection and analysis activities, to gain an overarching perspective on the extent and nature of non-compliance with visa conditions.

DIBP’s response: Agreed.

2.5 The department accepts the recommendation and advised of a number of activities already in place and planned, as set out in Appendix 1.

Does the department have an effective risk and intelligence function for visa compliance?

The department does not currently have an effective risk and intelligence function supporting visa compliance. In December 2014, the department’s Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division, established in 2010 to better coordinate and integrate risk and intelligence functions across the department, was abolished, and the functions dispersed to areas across the department and to the Australian Border Force. As at September 2015, DIBP was undertaking a series of reviews of these functions, to determine its medium to long term approach to managing risks to the integrity of Australia’s migration and visa programs. The functions are now subject to another restructure within some four years, and significant effort will be required to fully implement the revised arrangements.

2.6 Understanding and mitigating the risk of non-compliance with Australia’s migration and visa laws is a complex area of public administration. DIBP processes must allow for the efficient entry and stay of people, while targeting those individuals who breach their visa conditions or present a threat to the community. The complexity of identifying, assessing and mitigating risks arises from the scale and diversity of Australia’s visa program, with visa holders travelling from all over the world under one of 134 classes and 233 sub classes of visas. A major challenge for DIBP in managing these risks is to effectively integrate risk and intelligence processes across the department, to enable effective sharing of information and analysis and prioritisation of risk treatments.

2.7 The aim of integrating risk and intelligence functions was outlined in the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s Client Services Transformation Strategy 2009–1416, which had sought to formally link upfront visa processing with onshore integrity and compliance functions, thereby covering all ‘client life stages’ in their interaction with the department. Prior to this, the relationship between program integrity, status resolution services, and compliance activities had not been fully considered by the department.17 Despite overlap of client life stages, they were managed separately (including in the regions), with separate planning and reporting arrangements, and different lines of accountability.

2.8 To achieve an integrated approach, in 2010 the department established the Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division to ‘detect, measure and recommend treatments to mitigate multiple dimensions of risk across the department’s full operations’, bringing together various risk and integrity functions that had been dispersed across the department. This required a substantial amount of work, as individual teams or branches undertaking visa processing work, including assessing applications and conducting proof of identity checks, had previously prepared their own risk assessments. Many of these assessments were largely unstructured and informal and applied only to the immediate activity, and there was no mechanism to incorporate the results of compliance field activities into the earlier stages of the visa process.

2.9 The ANAO has previously commented on the integration of visa administration processes. In its earlier Audit Report No. 46 2010–11, Management of Student Visas, the ANAO stated that the (then) newly created position of Global Manager Operational Integrity was pursuing a holistic ‘client life’ principle by seeking to develop end‐to‐end visa integrity processes.18 The report further noted that, while program integrity was difficult to measure accurately and systematically, testing the cost-effectiveness of integrity measures as compared with compliance operations would be a useful exercise. This type of comparison would facilitate assessment of the performance of the respective functions, and clarify the dynamics of the relationship between offshore integrity as an ‘upstream’ function and onshore compliance as a ‘downstream’ function.

2.10 The development of the department’s Compliance Strategy 2012–15; the introduction of Integrity Partnership Agreements to coordinate integrity functions for specific visas; and the establishment of a national team to manage allegations of non-compliance, were clearly designed to support a more integrated approach to risk management. The Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division’s A Year in Review 2013–14 outlined the division’s achievements to date (and priorities for the coming year).

2.11 The Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division was abolished in December 2014, as DIBP integrated the risk and intelligence functions of the department with similar responsibilities in the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service. The division’s functions were dispersed across the department, including to a newly established Intelligence Division, other areas of the department, and to the Australian Border Force. As at June 2015, there was limited evidence to demonstrate progress in linking the various program integrity functions and compliance activities, or more clearly defining the relationship between them.

Compliance Strategy 2012–15: linking integrity functions and compliance activities

2.12 In 2011, the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship launched its Compliance Strategy 2012–15. The strategy clearly outlined a compliance model where the stages of visa administration and compliance were presented as a single program or continuum. The compliance model is shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, compliance model

Source: DIBP Compliance Strategy 2012–15.

2.13 As at 1 July 2015, the strategy had lapsed, having been in place for around 18 months. There was no evidence to indicate that it had been implemented beyond articulating the concept of an integrated and ‘joined-up’ approach to compliance—the strategy was referred to by compliance field teams, but there was no area of the department with overall responsibility for it. Specifically, the department had not outlined how ‘feedback’ would be collected across the four stages of compliance identified in the model, or how results in each stage, and across the continuum, would be measured.

Border Continuum Model

2.14 Subsequent to the abolition of the Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division, and the lapsing of the Compliance Strategy 2012–15 from 1 July 2015, DIBP’s approach to administering Australia’s migration, temporary visa and customs legislation has been based on a Border Continuum Model. The model aims to identify and mitigate risks of non-compliance: offshore, when people apply for a visa or to import goods to Australia; at the border, when people or goods enter the country; and onshore, where visa holders are required to comply with the conditions of their visa, including leaving the country when their visa expires.

2.15 The concept of a border continuum—recognising the relationship between upstream decisions on visa applications and enforcement activity after a visa has been granted—is not new, but the department is developing new structures and capabilities to implement the approach. The DIBP Corporate Plan 2015–19 refers to the department adopting an ‘intelligence led, risk-based approach to focus on mitigating the risks, including security risks, posed by the complex composition of temporary and permanent visitors’19; and the implementation of a departmental risk management policy and framework, in accordance with section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 201320 and the Commonwealth risk management policy. Appendix 2 presents DIBP’s advice about its intended approach to managing border related risks.

Coordinating risk functions through Integrity Partnership Agreements

2.16 Integrity Partnership Agreements were established by the Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division as the primary contact and coordination point for the identification and management of risks across the range of visa administration activities.21 The agreements were introduced in 2013–14, to provide ‘end-to-end’ coverage of the risks associated with the visa and citizenship programs, and to be the main mechanism to identify and mitigate those risks. The agreements, developed in conjunction with risk owners and other departmental risk management stakeholders, establish a risk profile for a visa program; identify a Risk Management Group; and facilitate six-monthly risk review reports to support decision making on risk settings.

2.17 As at 1 July 2015, six agreements had been established22 since early 2014, covering more than 80 per cent of visas in terms of volume. The value and effectiveness of these agreements in managing non-compliance risk has not been evaluated, nor have the outcomes of compliance field activities been factored into the risk assessments for established agreements.

2.18 The ANAO has previously commented on the Integrity Partnership Agreement that had been established for the Citizenship Program. The ANAO noted that, prior to the implementation of the agreement, DIBP did not have a systemic approach to identifying, analysing or responding to risk specific to the Citizenship Program, and that:

The introduction of the Integrity Partnership Agreement [IPA] is a useful first step in providing DIBP with a more structured approach to managing the risks to the Citizenship Program. However, it will be important that the IPA is tailored to the Citizenship Program. DIBP informed the ANAO that ‘further development is required to ensure that the IPA is sufficiently broad and correctly linked to new stakeholders to support the citizenship program’ and that it will be reviewed in light of the departmental restructure.23

2.19 As at September 2015 the department advised that work was underway to review all agreements, now referred to as Risk Partnership Agreements, and their application will be extended to cover all temporary and permanent visa programs. A new Caseload Assurance Framework is also being developed24: the draft document clearly identifies the issues impacting on the department’s capacity to achieve a level of confidence that risks in the visa programs are being effectively managed, and how these issues will be addressed.25

Establishing a national team to manage allegations of non-compliance

2.20 The National Allegations Assessment Team is responsible for the centralised management of all allegations (received from members of the public, other government entities, or from other areas of the department) concerning possible fraud and non-compliance with visa conditions. The team was established in 2010–11, drawing staff from the Compliance Information Management Units located in each state and territory office, to provide a more coordinated function. Staff are located in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane, but operate under national procedures.

2.21 Allegations can be lodged through several channels, including a dedicated free-call phone line, referred to as the ‘dob-in’ line. There are two discrete functions within the National Allegations and Assessment Team: the processing of written allegations, and a separate team, referred to as the Information Collection Unit, responsible for allegations received by phone. The number of allegations recorded by channel is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Allegations received by channel, 2010–11 to 2014–15

|

Channel |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Web form1 |

N/A |

5 577 |

11 267 |

12 384 |

14 901 |

|

Phone |

8 660 |

7 040 |

6 558 |

6 537 |

5 031 |

|

|

4 098 |

3 627 |

4 314 |

5 918 |

5 156 |

|

|

1 683 |

1 966 |

2 598 |

3 228 |

2 968 |

|

Fax |

890 |

547 |

335 |

245 |

178 |

|

In person |

259 |

198 |

105 |

122 |

54 |

|

Total2 |

15 590 |

18 955 |

25 177 |

28 434 |

28 288 |

Note 1 Introduced in 2011, the web form is an online reporting format available to the public via the department’s website.

Note 2 The data in the table reflects the number of: written allegations (irrespective of whether or not they are referred for further action); and the number of phone allegations that are referred for further action (no record is kept of those that are not referred).

Source: DIBP, Programme Analysis Report, September 2014, p. 15.

Receiving allegations

2.22 Allegations received by web form and email are subject to an automated word filter that sorts them into two queues, standard or sensitive, where sensitive includes allegations with a high priority such as threats to national security or public health.26 These allegations are given a Priority 1 classification and should be entered and referred within two hours of having been received. The standard for other allegations is that they are attended to within seven days. However, the National Allegations Assessment Team operates within standard weekday business hours, making the two hour standard effectively unachievable outside of these hours.27 The team also does not collect data on the extent to which Priority 1 allegations are referred against the standard.

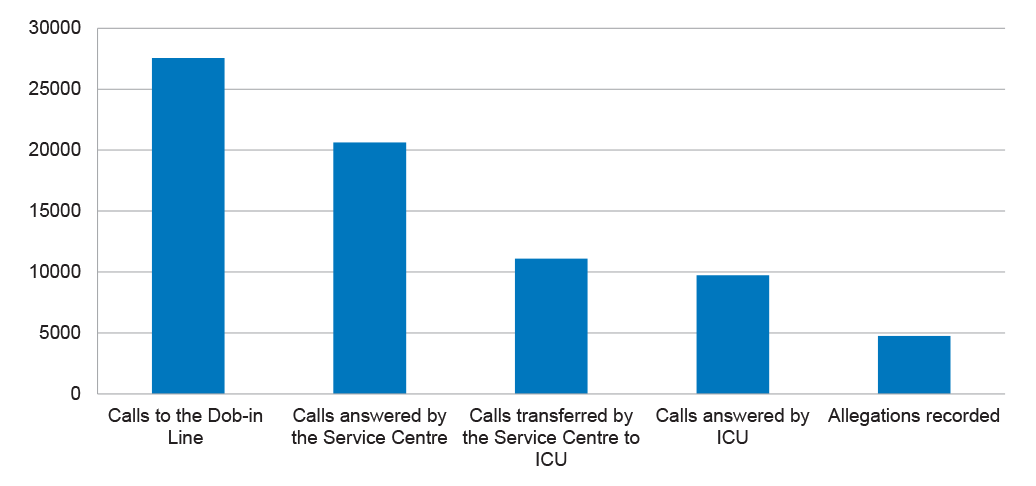

2.23 Allegations received by phone are directed initially to the DIBP Service Centre and, subject to their content, may be transferred to the Information Collection Unit, other business areas, or to another entity. A large number of calls to the dob-in line are subsequently abandoned by the caller during this process. In the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015, of the 27 561 calls to the dob-in line: 8298 (30 per cent) were abandoned before being answered by the Service Centre or during the transfer to the Information Collection Unit. The data is shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Dob-in line outcomes, 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015

Note 1: Of the 9727 calls answered by the Information Collection Unit, 4760 (49 per cent) were recorded and referred for further action. No record is kept of allegations that are not referred for further action.

Source: ANAO, from data provided by DIBP.

2.24 There is no Service Level Agreement between the DIBP Service Centre28 and the Information Collection Unit setting out respective service levels and expectations. The rationale for directing calls to the dob-in line through the Service Centre in the first instance has not been documented, and there is no monitoring of the type or content of calls that are not transferred. As a consequence, the department does not have visibility of the potential intelligence from a large number of calls made to the line.

Analysing and referring allegations

2.25 A Fraud Allegation Referrals Matrix (the matrix) is used by the National Allegations Assessment Team and Information Collection Unit to direct the analysis, classification and referral of allegations, where sufficient information has been provided to identify a person or organisation of interest. The matrix is a stand-alone, spreadsheet-based tool developed in 2011, and maintained by the National Allegations Assessment Team. It consists of a series of worksheets by the category or subject matter of the allegation, for example, people working illegally or threats to national security. Each worksheet details the circumstances that determine when to use that category; its priority and service standard for recording and referral; and information about the business area to which it should be referred.

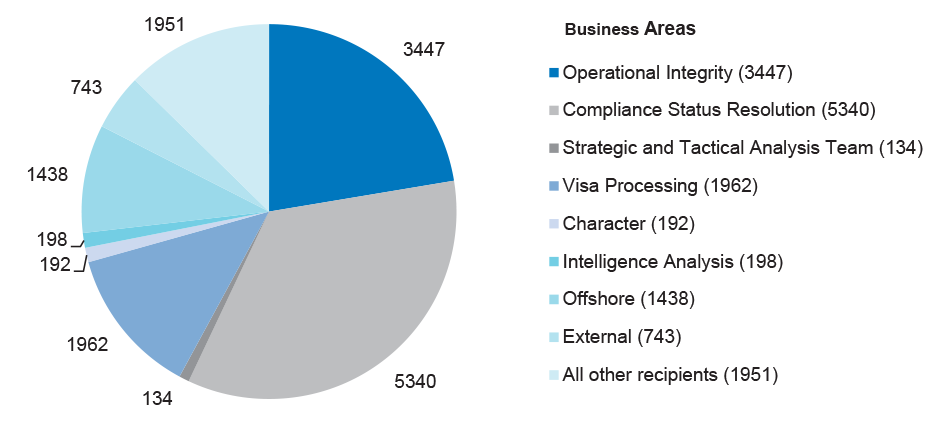

2.26 A breakdown of referrals for 2014–15, is provided in Figure 2.3. Of the 15 400 referrals in the reporting period, the most common areas receiving the referrals were Compliance Status Resolution (35 per cent), Operational Integrity (22 per cent) and Visa Processing (13 per cent).

Figure 2.3: Referral of allegations, 2014–15

Note: ‘Operational Integrity’ consists of referrals to Visa Cancellations and Program Integrity Units; ‘Compliance Status Resolution’ includes referrals to compliance field teams. ‘Character’ refers to the character cancellation team.

Source: DIBP, National Allegations Assessment Team (NAAT) Dashboard Report, June 2015.

2.27 While the matrix provides guidance for staff processing allegations, it has been developed and is maintained in isolation from the business areas to which allegations are referred. This is despite operating procedures stipulating the establishment of formal agreements with referral areas, and the need for improved communication being raised in a 2013 internal audit.29 As at June 2015, no formal agreements had been established, and communication between the National Allegations Assessment Team and referral areas was essentially an ad-hoc exchange of emails and occasional meetings. Consequently there was no mechanism to assess the extent to which referrals were appropriate, or were useful in achieving compliance outcomes.

2.28 As at 1 July 2015, options to integrate the management of allegations with a similar service in the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service were being considered. While this may change existing work flows and processes, allegations are an important source of information and intelligence for the department in addressing non-compliance with visa conditions, and there is scope to improve the operations of the function.

Recommendation No.2

2.29 To improve the management of allegations concerning possible non-compliance with visa conditions, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

- increases the proportion of calls to the dob-in phone line that are answered; and

- implements standards/processes between the National Allegations Assessment Team/Information Collection Unit and the business areas to which allegations are referred, which set out how allegations are to be assessed, referred and reported.

DIBP’s response: Agreed.

2.30 The department accepts the recommendation and advised of a number of activities already in place and planned, as set out in Appendix 1.

3. Promoting and supporting voluntary compliance

Areas examined

This chapter examines DIBP’s approach to promoting and supporting visa holders’ voluntary compliance with their visa conditions.

Conclusion

DIBP has established appropriate arrangements to ensure that information relating to visa conditions is readily accessible to visa holders, and initiatives underway aim to improve the department’s stakeholder engagement more broadly.

An evaluation of services supporting people who voluntarily engage with the department about their visa status was conducted in 2012. While the evaluation found that the services were broadly meeting their objective, the department is yet to finalise its response to the report and its 13 recommendations related to important aspects of the program’s administration.

Can visa holders readily access information about their visa conditions?

DIBP’s information about visa entitlements and conditions is readily accessible to visa holders and the general public, including through social media and on-line and mobile delivery, with the department also providing access to interpreting services and information products in several languages.

3.1 In 2008–09, the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship made a significant investment in the information and services available to visa holders, in response to the (then) Government’s major reforms to Australia’s immigration detention policy, New Directions in Detention. The reforms promoted visa-holders’ voluntary compliance with their visa conditions, placing more emphasis on preventing and deterring people from becoming ‘unlawful’ with regard to their visa status (rather than detaining and removing them as the default position).30 As part of these reforms, the Community Status Resolution Service was established in December 2008, and the sources of information available to promote and support voluntary compliance were expanded.

Information about visa conditions on-line and through social media

3.2 Information about Australia’s migration and visa programs is available on the DIBP website, and the department maintains an online ‘self-service’ environment that provides public access to a range of services. Notifications sent to visa applicants and employer sponsors about the grant of their visas include information about visa conditions. Within Australia, access to the department’s website and free-call telephone services is available through self-help facilities in the department’s state and territory offices. There is also access to free phone-based translation services for people from non-English speaking backgrounds.

3.3 DIBP maintains six social media accounts that broadcast specific messages about migration and temporary visa conditions, aimed at different audiences.31 The department has also made the material available to people from non-English speaking backgrounds, for example selected YouTube videos are available in around 16 languages.32 The information provided via social media complements periodic campaigns that are promoted in newspapers and online advertising, bulk mail-outs to individuals and organisations, and community information sessions aimed at raising awareness of particular issues.

Self-help: Visa Entitlement Verification Online

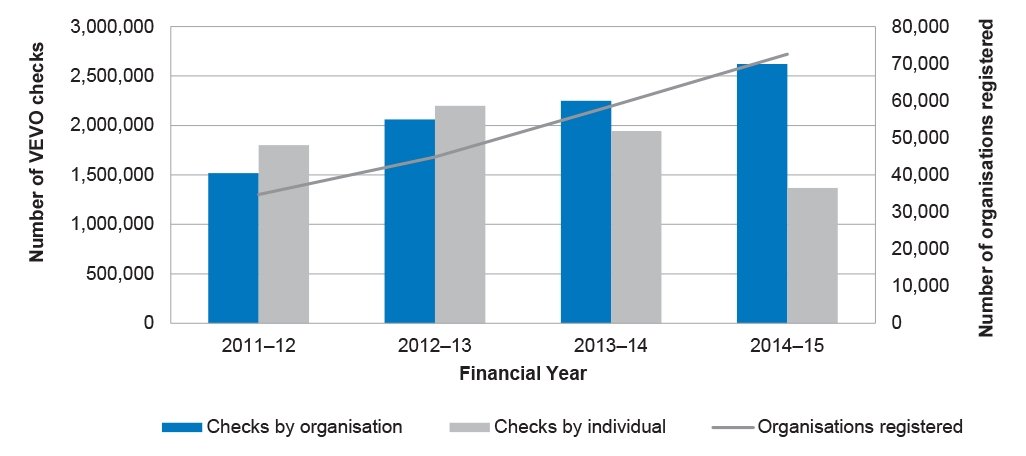

3.4 The Visa Entitlement Verification Online (VEVO) service allows the majority of visa holders to check their visa details and associated entitlements, including whether they are permitted to work. Organisations with an Australian Business Number and registered migration agents can also register for an account to access VEVO and, with the visa holders’ permission, check their entitlement to live, study or work in Australia.33

3.5 In 2014–15 the top two VEVO checks completed by organisations concerned visa holders’ entitlement to work (60 per cent) and to study (seven per cent). The VEVO service is well used.34 The number of organisations registered, and the number of checks by organisations and individuals for the period 2010–11 to 2014–15, is set out in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: VEVO service: numbers of checks and registered organisations, 2011–12 to 2014–15

Note 1: The number of ‘checks’ reflects each time an organisation or individual has accessed VEVO.

Source: ANAO, from DIBP information.

Do DIBP’s services effectively support voluntary compliance?

An external evaluation of the services supporting voluntary compliance, finalised in December 2012, concluded that the services met the objective of reducing the time to resolve clients’ visa status, and reduced the overall caseload. The evaluation report also identified weaknesses in aspects of the administration of the services, and included 13 recommendations relating to, among other things, the governance of the services and the lack of key performance indicators. As at June 2015, the report and its recommendations had not been fully considered by the department, and consequently there is little assurance that weaknesses identified in the report have been addressed.

3.6 The services available to visa holders who voluntarily engage with DIBP about their visa status are:

- Compliance Counter, which is designed for clients who require little or no intervention to resolve their immigration status;

- Community Status Resolution Service, which is designed for clients who require some assistance to resolve their immigration status; and

- Case Management Teams, which engage with vulnerable clients, or those with complex issues who require a level of individual support and intervention to achieve a timely immigration outcome.

Evaluation of the services supporting voluntary compliance

3.7 In 2011, DIBP commissioned an external evaluation of the services supporting voluntary compliance, Evaluation of the enhanced Compliance Status Resolution Program.35 The evaluation team was tasked with examining the: Compliance Counter, Community Status Resolution Service, Community Assistance Support Service (now referred to as Case Management) and Assisted Voluntary Return Service.36

3.8 The report of the external evaluation, provided to the department in December 2012, concluded that ‘the enhanced Compliance Status Resolution Program was largely on track to achieving program objectives’ referring to the:

underlying program approach (which is based on early intervention, active client engagement and assessment of need, clear identification and communication of client pathways and where eligible, client referral to appropriate support services) aims to create an environment that is conducive to client engagement and voluntary compliance.37

3.9 This positive overall conclusion was based largely on analysis of measures showing that more resolutions had been achieved in a shorter period of time and the entrenched client caseload had reduced.38 The report made 13 recommendations, including that the services supporting voluntary compliance could be better integrated within the broader compliance program (and included a draft program logic and performance indicators in the report). Similarly, the Australian Public Service Commission Capability Review 2012 commented that the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship lacked a common definition and understanding of program management, which led to confusion about accountability and responsibility for programs as opposed to structural lines of business.

3.10 A summary report on progress in addressing the recommendations of the external evaluation was produced in May 2014. Similar to many departmental documents reviewed throughout this audit, the summary report did not include any information as to the document’s status, including whether the content of the report had been considered and or approved by the department’s executive.39

3.11 While the teams and executive positions with responsibility for responding to the evaluation and its recommendations were abolished in early 2015, the department provided a final report on the evaluation to the ANAO on 22 July 2015, with advice that:

Due to the extended time required to finalise this report…a review of the department’s implementation of the report recommendations, as suggested in the May 2014 Summary Report, has not been conducted.

Consistent with earlier observations, there was no evidence that this report had been considered and/or approved by DIBP’s executive.

Is there a coordinated approach to stakeholder engagement to inform visa compliance?

There are shortcomings in DIBP’s management of stakeholder engagement, primarily relating to the lack of a corporate approach and limited analysis of client feedback. To address these shortcomings, the department has recently consolidated its communications and media functions (that were previously fragmented across different areas of the department) in order to provide a coordinated and consistent approach to stakeholder engagement; and commenced the development of a corporate stakeholder engagement plan. A project is underway to improve the department’s management of client feedback.

3.12 In its review of the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship, the Australian Public Service Commission Capability Review 2012, the Australian Public Service Commission noted that the Senior Executive staff of the department:

has a strong but internally focused culture, which reduces opportunities to draw on the insights and support that other agencies and stakeholders could provide, including the identification and management of risks; [and] close collaboration with external partner agencies and stakeholders is increasingly critical to the department’s success in contributing to its social, economic and national security objectives, and building joint capabilities with ever decreasing resources.40

Managing stakeholders

3.13 Communication strategies to promote voluntary engagement and status resolution services were developed and delivered in the absence of a broader departmental stakeholder strategy. The Australian Public Service Commission Capability Review 2012 of the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship identified stakeholder management as one of six functional capabilities requiring improvement. Specifically, the review noted that the ‘department lacks a planned approach to stakeholder relationship management’ and that:

there is no corporate guidance on how to manage stakeholders, nor was there a list of current stakeholders, nor is it easy to identify current DIAC stakeholders, their interests and lead points of contact within the department. Currently, stakeholder management is fragmented across business areas with varied approaches to relationship management.41

3.14 In response to the findings of the capability review, DIBP developed a Stakeholder Engagement Strategy 2014–2016 and supporting documentation, but the strategy had not been implemented prior to the announcement of the current integration and reform agenda. From 1 July 2015, teams responsible for departmental communications and media, including the team with responsibility for status resolution communication, have been integrated into a central unit. An exercise to map key stakeholders across the new department has been completed, and the development of a new plan for stakeholder engagement, incorporating work already undertaken by the two entities, is underway.

Assessing client feedback

3.15 DIBP maintains a Global Feedback Unit, established in 2007, as the central point for receiving, tracking and responding to client feedback from overseas and within Australia. In 2014-15, the department received 16 898 client comments, of which 12 488 (74 per cent) were received through a web form. Of these, 9468 were complaints, 1108 compliments and the remainder general enquiries or requests. The Australian Public Service Commission Capability Review 2012 noted that:

on a day-to-day basis, managers report that evidence-based business decision-making is impeded by a lack of timely and reliable data. In some cases data that is captured (for example, complaints and compliments data) is reported statistically but not evaluated to inform policy development. The outcomes of complaints are not centrally tracked to identify trends that might influence policy decisions and business strategies.42

3.16 The Global Feedback Unit aims to resolve client feedback when it is first received, but where this is not possible, the feedback is referred to the relevant area in the department for a response. As at February 2015, quarterly reports are provided to Senior Executive Staff on feedback received relevant to their business line, providing information on the number and category of comments received, and how many of them were handled by the unit. The policy for managing feedback, introduced by the (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship in 2012 states that managers are expected to analyse feedback and use it to identify issues relevant to their business, and any emerging trends or problems.

3.17 However, while the Global Feedback Unit tracks the timeliness of the department’s responses to feedback cases, it does not monitor the responses for quality or consistency of message. Some three years after the capability review, there was no evidence of a department level mechanism to ensure that the feedback is analysed to identify emerging issues, or actioned appropriately.

3.18 In July 2015, the Global Feedback Unit and the Complaints and Compliments Management Unit from the (previous) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, were integrated as phase 1 of a project to improve the management of feedback. Phase 2 of the project, to be completed by December 2015, focuses on improving the operations of the unit and planning for the third phase, scheduled for implementation in 2016, will further develop a single work flow for the integrated units.

4. Visa cancellation and compliance

Areas examined

This chapter examines DIBP’s measures to enforce compliance with visa entitlements through visa cancellation and compliance field activities.

Conclusion

The department has well established arrangements to manage the cancellation of visas, but shortcomings in the processes to measure, monitor and report on the levels of fraud and risk in visa administration reduce the level of confidence that visa cancellations are an effective compliance measure. As at September 2015, a new Caseload Assurance Framework was being developed across the Visa and Citizenship Group that is designed to provide a higher level of confidence that known and emerging risks in the visa caseload are being managed effectively.

The operations of compliance field teams are not well managed. There is considerable variation in the structure and operation of these teams, and few performance indicators, quality assurance processes or management reporting arrangements to support an assessment of the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of their work. From 1 July 2015, the teams were integrated with similar functions from the (previous) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the maintenance of records and documentation of compliance field activities.

Does DIBP have appropriate arrangements for cancelling visas?

DIBP has well established arrangements to manage the cancellation of visas, including through the introduction of a more efficient business model for visa cancellation teams in early 2015. However, the department has identified the lack of a defined and consistent approach for measuring, monitoring and reporting on the levels of fraud and risk in the visa and citizenship caseload. As at September 2015, a new Caseload Assurance Framework was being developed, which aims to provide a higher level of confidence that known and emerging risks in the visa caseload are managed effectively.

4.1 Under various sections of the Migration Act 1958, the Minister or delegate has the power to cancel visas where visa holders fail to meet the conditions of their visa, including on character grounds. The cancellation of visas is mostly undertaken by the two sections in the Character Assessment and Cancellations Branch—the National Character Consideration Centre and the General Cancellations Network. This branch, which was previously part of the Risk, Fraud and Integrity Division, is now located in the Community Protection Division of DIBP.

4.2 Visa applicants identified to be of potential character concern are referred to the National Character Consideration Centre for character assessment. The (then) Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s administration of character requirements was examined in two previous ANAO audits, and not further examined in this audit.43

General Cancellations Network

4.3 The General Cancellations Network comprises the Cancellation Allocation and Support Team, and visa cancellation teams in each state and territory office. The number of visas cancelled in 2013–14 and 2014–15 is set out in Table 4.1. The majority of voluntary cancellations relates to clients requesting cancellation of their visas in order to access their outstanding superannuation entitlements.44

Table 4.1: Visa cancellations, 2013–14 and 2014–15(1)

|

Category |

2013–14 |

2014–15 (Jul–Mar) |

|

457 visa cancellations |

26 978 |

21 967 |

|

Student visa cancellations |

8 021 |

6 477 |

|

Cancellations on fraud grounds |

1 059 |

932 |

|

Voluntary cancellations |

14 238 |

14 106 |

Note 1: A cancellation may be recorded in several categories (for example, a student cancellation may also be a fraud cancellation). For this reason, the table does not contain a total.

Source: Data provided by DIBP.

Cancellation Allocation and Support Team

4.4 The Cancellation Allocation and Support Team is the central point for the collection and assessment of all information (other than on character) related to visa holders who may no longer be entitled to hold their visa. Cases are referred by the National Allegations Assessment Team, from other areas of the department, and from Commonwealth, state and territory entities. The team receives around 130 referrals each month, with approximately 50 per cent from the National Allegations Assessment Team. These cases are assessed manually using the Complex Visa Cancellation Priority Matrix, which was developed by the team, as well as any additional risks identified through regular meetings with General Cancellations Network managers to determine priority processing. As at June 2015, DIBP advised that the matrix was under review.

4.5 The Cancellation Allocation and Support Team is also responsible for taking action on the monthly Targeted Cancellation Reports for student and temporary worker (457) visa streams (provided to them as part of the Integrity Partnership Agreements, discussed in Chapter 2). These reports typically include thousands of potential visa cancellations.45 Cases included in the reports are prioritised by risk prior to being sent, and the team usually does little other than assign the work to state or territory-based cancellation teams to be actioned, although the department advised that a considerable amount of work is undertaken by the support team to improve the accuracy of the data to increase the utility of the reports.

4.6 The team can, however, adjust risk ratings to reflect emerging risks and the section’s own priorities, but it is not clear how these adjustments relate to the risk ratings assigned through the Integrity Partnership Agreement processes (which provide a departmental view of risk) or in the new Caseload Assurance Framework, discussed in Chapter 2.

Actioning visa cancellations

4.7 The process to cancel a visa includes: issuing a Notice of Intention to Consider Cancellation; notifying the client of the decision; and outlining their options (such as appeal). Following a departmental review of the management of cancellations conducted in December 201346, a new business model, the Collective Case Management Model, for cancelling visas is being rolled out across the visa cancellations network from May 2015. Under this model, groups of case officers focus on specific stages of the cancellation process replacing the previous model, the Total Case Management model, where four specialist Visa Cancellation Units, operating independently of each other, managed workloads for each of student and 457 visa streams, voluntary cancellations and complex cancellations.

4.8 DIBP considers that these revised arrangements have the potential to deliver greater flexibility in managing priorities, with the ability to transfer work around the network at short notice. Earlier trials had also shown that managers have greater visibility of the quality of record keeping and decisions of individual visa cancellation officers, but this has still to be fully determined in regard to cancellations work.

Are compliance field activities well managed?

The operations of compliance field teams are not well managed. There are weaknesses in almost all aspects of the function, including the management of information as to which field activities would be undertaken; ad hoc and insufficient use of management reports; an absence of appropriate performance indicators to assess the efficiency or effectiveness of the activities; and variations in the structure and operation of the teams across states and territories. From 1 July 2015, the teams were integrated with similar functions from the (previous) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service under a regional command structure, and a new operating model for the Australia Border Force was being developed.

4.9 Where visa holders do not comply with their visa conditions, enforcement action may be taken by DIBP’s compliance field teams. The teams are based in the capital cities in each state and territory (with staff also based in Cairns). The teams focus largely on locating unlawful non-citizens and people working illegally, and also conduct outreach visits, including to regional and remote locations, advising communities on migration and visa matters. Compliance field activity is managed through the Compliance, Case Management, Detentions and Settlement (CCMDS) portal.

Structure and operation of compliance field teams

4.10 Compliance field teams analyse information about non-compliance and, based on the results of the analysis, conduct compliance activities. The teams operate with a departmental framework set out in policy and procedural guidance, but have a considerable degree of autonomy in how they are structured and how they manage their work. Variations across state and territory teams include:

- Victoria is divided into three geographical regions; NSW operates as a single team; and teams in Western Australia are structured around industry groups;

- the use of the CCMDS portal’s reporting and query capability to manage inputs and workflow varies, with one team highly engaged in using the capability and another not using it at all;

- one team uses the Overstayers Report (to assist in the planning of compliance activities) while another considers that the report provided little value; and

- arrangements with state and territory jurisdictions, including with police forces, differed.47

4.11 While acknowledging that each state and territory presents different challenges for compliance teams, necessitating some tailoring of approaches to address risk, DIBP was not able to demonstrate the rationale for, or effectiveness of, the various structures and approaches.48 Shortcomings in measuring the effectiveness of compliance field activities were highlighted in the DIBP internal audit, Identification and Management of Visa Overstayers (December 2013), which found that DIBP:

had limited key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure the effectiveness of the Compliance Strategy and Compliance Field activities; and was exposed to risk as, without appropriate performance measures in place, DIBP is not in a position to assess the effectiveness of its approach and activity to managing visa overstayers, and compliance activity more broadly.

4.12 As at June 2015, an evaluation of the effectiveness or efficiency of compliance field operations had not been conducted. The department advised that a performance evaluation section is to be established within the Australian Border Force, to develop appropriate performance arrangements at all levels of the Australian Border Force’s operations by June 2016.

Conducting compliance field activities

4.13 Information about non-compliance is received by compliance field teams from several sources, including the National Allegations Assessment Team. Based on analysis of this information, compliance field teams may:

- take no further action, where there is insufficient evidence;

- take administrative action that may involve, among other things, contacting a person or organisation of interest via phone or email; or

- conduct a field activity, in the form of an observation, non-warrant activity or warrant activity.49

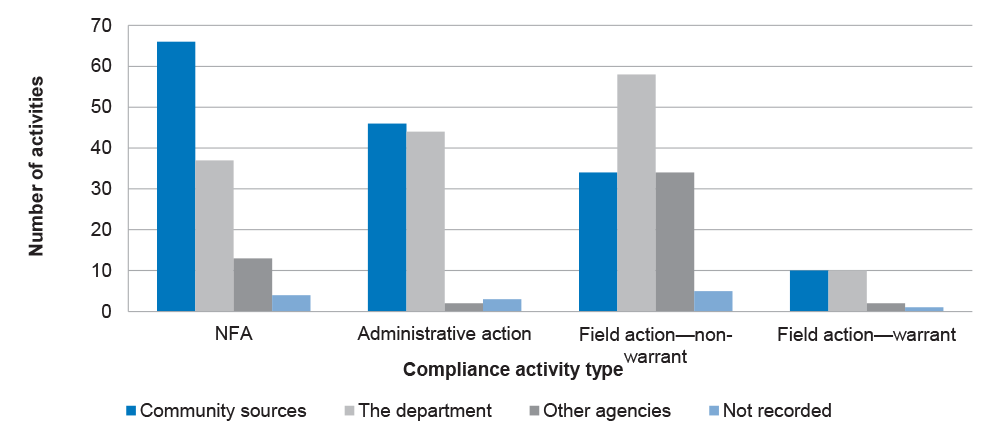

4.14 Between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2015, 10 141 compliance activities were finalised by compliance field teams, of which there were: 3228 cases where no further action was taken; 2551 administrative actions; and 4362 field activities (3485 non-warrant and 877 warrant). The ANAO selected a random sample of 371 of these activities and assessed them for adherence to the department’s policies and procedures50, as well as the extent to which the activities were recorded in the CCMDS portal. Table 4.2 summarises the nature and results of this testing.

Table 4.2: Summary of the ANAO’s testing of compliance field activities

|

Test |

Test results |

|

What sources of information are used to determine compliance field activities? |

Information from community sources (mainly dob-ins) is the main driver of compliance activities. |

|

How are compliance field activities prioritised? |

The Compliance Field Prioritisation Matrix 2013–15 sets out the priorities for compliance field activities. The rationale for the prioritisation of risks is not defined and not linked to risk assessments in the broader visa program. |

|

Are compliance field activities finalised in a timely manner? |

As at April 2015, 46 per cent of active compliance field jobs (that is jobs that are open and not finalised) had been active for more than one year. |

|

Is the rationale for undertaking specific compliance field activities properly recorded? |

In the majority of cases tested there was no rationale recorded as to why a compliance field activity was undertaken. |

|

Are the requirements under section 18 of the Migration Act 1958 and associated departmental guidance (for obtaining information about unlawful non-citizens from third party entities), fully met? |

In approximately 25 per cent of cases tested, records did not demonstrate compliance with the legislation. |

|

Are the required approvals obtained for compliance field activities (non-warrant and warrant visits)? |

Records indicated that the necessary planning and approval had been obtained in 99 per cent of cases. |

|

Are operational risks for compliance field activities properly assessed? |