Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Assets and Contracts at Parliament House

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Parliamentary Services’ management of assets and contracts to support the operations of Parliament House.

Summary

Introduction

1. The opening of the ‘new’ Australian Parliament House in 1988 was a landmark in Australia’s history. Recognised as a uniquely designed, functional building, Parliament House cost $1.1 billion to complete and has an intended life span of 200 years. The Parliament House complex occupies a 35 hectare site, has a total floor area of 250 000 square metres, with around 4500 rooms, public areas and retail outlets across four levels. In addition to the building fabric, Parliament House contains over 100 000 maintainable assets, some of cultural and heritage significance, and 32 hectares of landscaped open space.

2. The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) has an important role in managing Parliament House as an operating building and a place of national significance. In doing so, DPS provides a range of services, including: broadcasting and Hansard1; information and research; security; building and landscape maintenance; and information and communication technology (ICT). In 2013–14, the department had around 700 staff and an annual budget of $137 million.2 Under the Parliamentary Service Act 1999, the Presiding Officers (the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives) jointly administer DPS. The Secretary is responsible to the Presiding Officers for the efficient operation of DPS.

3. Effective asset and contract management practices are key elements in DPS managing Parliament House. To manage and maintain Parliament House and associated assets, which are collectively valued in excess of $2 billion, DPS has an asset management framework that includes: asset acquisition and replacement planning3; operations and maintenance; and monitoring and reporting of asset condition. The department also has a computerised asset management system, including an asset register with some 16 500 groups of items.

4. To meet its obligations to operate and maintain Parliament House, DPS also contracts the supply of many services to external providers and manages licence arrangements with several retail service providers that occupy space within Parliament House. In 2013–14, the department managed some 190 contracts, involving expenditure of $62.8 million in that year. These contracts covered a range of activities, including: building maintenance, renovations and upgrades; security; telecommunications and utilities; catering; and cleaning.

Parliamentary interest

5. In recent years, many aspects of DPS’ management of Parliament House have been the subject of parliamentary interest. In particular, in May 2011, Senators raised specific concerns regarding the disposal of Parliament House assets with potential cultural heritage value.4 The department’s response to these matters led to an inquiry into the performance of DPS by the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee (SFPALC).

6. SFPALC’s final report was released in November 2012 and identified a wide range of issues relating to DPS’ employment practices, management of assets and contracts, and arrangements for security and ICT. SFPALC has continued to focus on DPS’ management of Parliament House during Senate Estimates hearings, particularly its asset (including heritage) and contract management practices.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Parliamentary Services’ management of assets and contracts to support the operations of Parliament House.5

8. To form a conclusion against this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) adopted the following high level criteria:

- governance and administrative arrangements for asset and contract management were effective;

- processes and procedures for the maintenance and disposal of assets (including cultural and heritage assets) were sound; and

- processes were in place to ensure legislative compliance, delivery of expected products and outcomes, and value for money from contracts.

Overall conclusion

9. In managing Parliament House, the Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) is responsible for maintaining the building6, supporting the work of the Parliament, and providing access to the public. Over recent years, the department has been subject to considerable parliamentary scrutiny and criticism, particularly from the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee (SFPALC) in relation to its management of Parliament House. The committee’s report, following its 2012 inquiry, made 23 broad ranging recommendations encompassing aspects of DPS’ asset and contract management arrangements, work practices, culture and systems.

10. In response to these recommendations, from mid-2012 the new Secretary commenced a process to ‘transform’ DPS. This process has involved an organisational restructure, the recruitment of senior executives to key leadership roles, and the conduct of reviews of capability, processes, practices and systems across many major functions of the department, including asset and contract management. At the time of the audit, however, a number of these reviews had yet to be completed and recommended changes implemented. Until such changes are embedded, the department’s processes do not exhibit the discipline required to provide assurance that assets and contracts are being effectively managed.

11. The audit highlighted particular concerns in relation to: inadequate staff training and out-of-date guidance material; poor record keeping practices; weaknesses in DPS’ systems underpinning both its asset management and contract management functions; and inconsistent work practices within these functions. These shortcomings are best addressed in the short term by stronger management attention and in the longer term as part of the broader program of changes being proposed by the department.

12. To address the strategic asset management considerations for Parliament House, and the other issues raised by SFPALC, the department is developing a strategic asset management plan. This plan is expected to guide asset acquisition, replacement, refurbishment and maintenance in coming years. To support the effective implementation of this plan, significant improvements are required to the department’s asset management sub-plans, systems and processes. In addition, capital works need to be better integrated with replacement and maintenance activities.

13. DPS has also invested considerable resources in responding to SFPALC’s concerns about the need for better heritage management through changes to management arrangements and assessment processes.7 However, these changes have lacked continuity, and the department was unable to demonstrate broad or systematic consideration of cultural or heritage value in making changes to the building through its capital works program or in storing or disposing of assets in 2013 and 2014. Notably, of 24 assets disposed of by DPS in 2013–14 and reviewed by the ANAO8, there was only clear evidence of two having been subject to a heritage evaluation before disposal.9

14. In relation to DPS’ contract management arrangements, there has been little improvement in the department’s contract management framework, processes or capability since the 2012 SFPALC report. DPS has not (as SFPALC recommended) implemented a sustainable training program for contract managers, with many contracting staff unsure of their contract management responsibilities. Guidance material, policies and procedures were also out of date. Reflecting these circumstances, there were inconsistent contract management practices, particularly in terms of preparing business cases, contract management plans, and end of contract evaluation reports, and in record keeping generally. There was also insufficient quality assurance mechanisms and management oversight to ensure the proper application of sound contract management practices.

15. Recognising that DPS is still in the early stages of organisational change, a number of key aspects of the department’s administration require attention to better support the achievement of its change agenda. Improving fundamental administrative practices, particularly record keeping, quality control and oversight, would enable the department to better conduct business as usual activities, manage change and sustain performance over time. More work also needs to be done to build cohesion and engagement between DPS management and staff over the longer term, to encourage constructive working relations within an environment of ongoing parliamentary and public scrutiny. These improvements would also better support the services provided by DPS, notwithstanding general satisfaction with the operation of Parliament House by the limited number of parliamentarians who were able to respond to the joint ANAO/DPS survey undertaken as part of this audit.10

16. In this light, the ANAO has made six recommendations relating to strengthening the department’s asset (including heritage) management and contract management arrangements.

Key findings by chapter

Asset Management (Chapter 2)

17. In response to the SFPALC inquiry in 2012, DPS’ asset management framework has been subject to considerable review and change. In this context, in November 2014 the department received a building condition assessment report that provides a baseline for assessing the condition of Parliament House assets.11 The report is being considered in the development of a strategic asset management plan, designed to bring together the main elements of DPS’ asset management framework in an integrated manner.

18. The implementation of the strategic asset management plan requires a disciplined approach to align investment in asset renewal and maintenance with program requirements. While the strategic asset management plan can provide high-level direction for managing Parliament House assets, it is not currently supported by sound and integrated management practices. The strategic intent outlined in the plan should be evident in policies and procedures, risk management, capital works planning, maintenance activities and monitoring and reporting. Strong management attention is required to bring about improvements such as: further development of systems that provide information to support capital management plans; an enhanced capital works plan that clearly identifies relative priorities; and a more comprehensive reporting regime for key aspects of asset management.

Management of Heritage Assets (Chapter 3)

19. In recent years, DPS has introduced a range of initiatives to strengthen its management of heritage assets at Parliament House. However, there has not been a consistent, coordinated approach, and together with poor record keeping, this has not enabled the department to demonstrate the effective management of these assets.

20. In November 2011, DPS established a Heritage Management Framework and Heritage Advisory Board to guide heritage management in the department. However, following criticisms during the SFPALC inquiry12, DPS ceased using the Heritage Management Framework in October 2012. In lieu, the department began developing a Conservation Management Plan with supporting design principles to improve the management of heritage values at Parliament House. As this plan is not scheduled for completion until mid-2015, there has not been an overarching framework guiding the management of heritage values in Parliament House since October 2012.

21. The Heritage Advisory Board had important responsibilities for heritage management at Parliament House13, but did not fulfil all these responsibilities prior to being disbanded in June 2014. DPS advised that consideration of the heritage implications of capital works had been fulfilled by the Heritage Management Team (following its establishment in April 2013) or by other areas of DPS. However, there is no documentation demonstrating that DPS has formally evaluated the heritage impact of capital works undertaken at Parliament House in recent years.

22. In considering the heritage impact of minor works, there was evidence of DPS undertaking 11 assessments in 2013–14, where advice had been sought from the Heritage Management Team. However, the results were not recorded in a central repository, and there would be value in DPS collating into a central repository all heritage assessments and moral rights14 consultations that have been completed to date. This would better position DPS to make informed and transparent decisions regarding the impact of changes to heritage values of Parliament House.

23. DPS’ process for the disposal of assets with potential cultural or heritage value has improved in response to previous reviews. However, this process is not always followed. As at October 2014, DPS was again revising its disposal policy to include guidance on the storage of assets. Given this revision, it would be timely for DPS to again consider the training provided to staff regarding the disposal of assets. Greater management oversight is also required if the department is to gain assurance that processes are being properly implemented and that assets with potential heritage value are being afforded appropriate care.

Contract Management Arrangements (Chapter 4)

24. DPS fulfils its responsibilities for the operation and maintenance of Parliament House through a combination of in-house staff and contracts with private sector providers.

25. To encourage structured and consistent management of contracted activities, the department has established a contract management framework that includes a range of policies, procedures and systems. Nevertheless, several systemic gaps and weaknesses have led to inconsistent, and at times noncompliant, contracting practices across the entity. Out-of-date guidance material, inadequate training, poor record keeping practices, and weaknesses in DPS’ systems underpinning its contract management functions have, collectively, adversely impacted on the department’s contracting activities, and ultimately its ability to demonstrate effectiveness of its contracting activities and financial accountability.

26. To improve compliance and consistency of contract management practices, DPS should give priority to establishing a structured program for contract management training, and monitor its effectiveness and impact on work practices over time. Clearly defining roles and responsibilities and developing and maintaining guidance material that is current and readily accessible to staff will also assist DPS to improve contract management arrangements.

27. Despite its substantial contract portfolio and annual budget, the DPS executive has limited visibility of contracting activity, with little structured monitoring or reporting in place. Improved management oversight and formal quality assurance activities would provide greater assurance that contracting processes meet government legal and policy requirements and are being properly implemented. To achieve greater accountability and transparency, there would also be merit in DPS taking further steps to improve the accuracy, completeness and functionality of its contract register.

Establishing and Managing Contracts (Chapter 5)

28. Given the shortcomings in DPS’ broader contract management framework, there has also been considerable inconsistency in contract management practices. There is scope for the department to strengthen all stages of its contract management—developing, managing and ending contracts—to improve transparency and accountability.

29. In developing contracts, many of which are long standing arrangements, only around one-third of those examined15 had business cases which included a clear basis for assessing value for money. A similarly low proportion of contracts had evidence of considering risk during initiation, and less than half had developed contract management plans. To help ensure suitable contracts are used, DPS has a suite of model contracts. However, these required updating to include mandatory clauses.

30. The model contracts supported the inclusion of schedules for establishing contract payments and deliverables. DPS staff generally followed the appropriate payment process, including checking of invoices to assure that the correct services or products were supplied. Even so, ANAO analysis found payments that were not linked to the contract on payment systems, and issues with overpayments and underpayments. It was not possible to readily determine the extent of these payment issues due to difficulties in linking financial payments to individual contracts, because of weaknesses in DPS’ ICT systems and inconsistent and incomplete record keeping.

31. DPS has made progress in introducing performance measures for some of the more substantial contracts, such as cleaning and catering. However, there would be benefit in DPS giving more emphasis to setting meaningful performance measures and clearer expectations for monitoring and reporting on contract performance. To better position the department to ensure desired contract outcomes and value for money are achieved, a more structured and consistent approach is required in relation to identifying key risks and entity reporting requirements, incorporating a suitable performance regime into contracts, and encouraging wider use of end-of-contract evaluation.

32. There is also scope for DPS to improve its management of retail licensing.16 There is no current retail strategy, clear policy or plan to give focus to, or to guide, DPS’ management of retail licensing in Parliament House. Overall, program/policy objectives and intended outcomes need to be clearer to enable forward planning and a better informed process for licence renewal. In general, licences would be significantly strengthened if respective (DPS and provider) expectations were made clearer, and the goods and services to be provided were clearly set out in the licence agreements prior to signing.

33. Client satisfaction and provision of appropriate services are important aspects of the retail services. To enable DPS to assess the appropriateness and benefits of the retail activities, the department could further consider how to best match business hours to user demand and develop a defined policy concerning external activities and clients. Management of the licences would be assisted by developing risk plans with appropriate mitigation strategies, and a monitoring and reporting regime to provide assurance of service quality and compliance with licence terms and conditions. Capturing and analysing key performance information would provide greater transparency of retail operations and assist DPS in optimising the use of Parliament House retail space.

Management Arrangements in the Department of Parliamentary Services (Chapter 6)

34. DPS has a range of governance arrangements to support asset and contract management, including strategic planning, risk management and monitoring and reporting performance. There is scope, however, for the department to improve these arrangements, including through aligning higher level planning and external reporting documents, finalising the strategic risk framework, and improving performance measures.

35. From mid-2012, the Secretary of DPS commenced a process to ’transform’ the department. Appointments to the new senior leadership team were made throughout 2012–13, and reviews covering its major functions were initiated. However, the change agenda is still in the relatively early phases, and DPS has only partially implemented the SFPALC recommendations relating to asset and contract management. Further improvements can be expected from ‘bedding down’ those initiatives and new processes. As for all change agendas, it is also important for the department to build cohesion between management and staff, as the reform processes introduced in recent years have affected staff morale and turnover.17

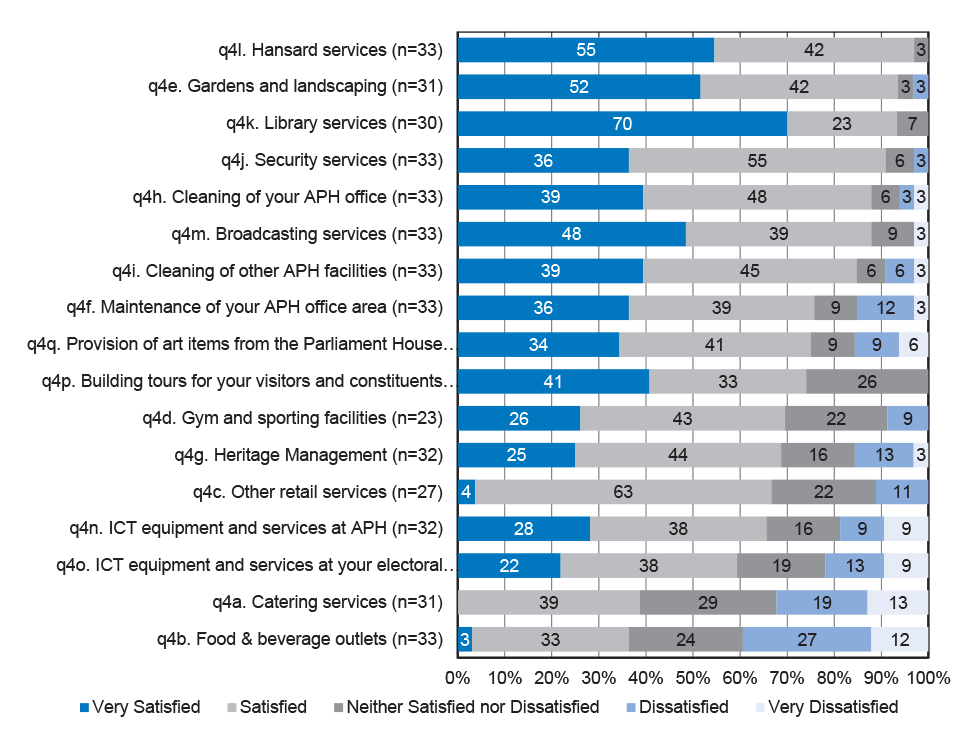

36. Notwithstanding the many opportunities for improving the management of Parliament House, the results from a joint ANAO and DPS survey undertaken during the audit indicated that the parliamentarians who responded are largely satisfied with DPS’ activities to support the operation of the building and its grounds.

Summary of entity response

37. DPS provided the following comments to the audit report:

The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) thanks the ANAO for the thoroughness of the audit and agrees with the recommendations that will assist DPS in continuing its reform agenda and improving its procurement and contract management capabilities and practices.

DPS notes that this audit follows on from the inquiry into the department conducted by the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee (SFPALC) in 2011-12. The audit was conducted at a time when DPS was still implementing some of the findings of the SFPALC’s 2012 report. As a result, a number of matters raised by the Report are in areas where DPS has been implementing change as recommended by the SFPALC 2012 Report.

Because of its ongoing transformation agenda, DPS had already taken, or was taking, a number of steps that will address the matters raised in this Report. While the department accepts all the recommendations in the report, it should be noted that DPS has been progressing a number of initiatives independent of the ANAO audit that will address many of the ANAO findings. These are detailed below.

Procurement and Contract Management

The audit highlighted particular concerns in relation to contract management and procurement such as inadequate staff training, out-of-date guidance material and a weakness of DPS’ systems underpinning the contract management function.

In response to the recommendations in the SFPALC 2012 Report, DPS identified a number of initiatives to enhance its procurement and contract management capability. The implementation of these initiatives was originally hampered due to a lack of available funding and appropriately skilled staff. As part of the 2014-15 budget process it was acknowledged that DPS was operating with a structural deficit that was expected to continue through the Forward Estimates. In the 2014-15 Budget, an additional $15 million was allocated from 2014-15 onwards. With these additional funds, DPS was able to commence action to identify and recruit appropriately skilled personnel (e.g. the Chief Finance Officer and Director of Procurement) to implement these initiatives. Recruitment for these roles was finalised October 2014.

Following the engagement of a suitably qualified Chief Finance Officer and Procurement Director, DPS commenced the organisational restructure of the central procurement team which is expected to be completed following recruitment action currently being finalised. The new procurement team, the composition of which is based on the recommendations made by Workplace Research Associates in their February 2014 review, will enable DPS to become a better practice organisation in regards to procurement and contracting.

In 2014, to comply with legislation (e.g. the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013) and Government policy (e.g. the Commonwealth Procurement Rules) a revised set of Financial Delegations and Accountable Authority Instructions were developed. These documents, which commenced on 1 January 2015, reflect the model instructions and guidance issued by the Department of Finance and strengthen the accountability of decision makers within DPS through the introduction of additional controls. For example, a new delegation relating to the disposal of assets was introduced, and a new instruction was issued that requires staff to obtain an “endorsement to proceed” through the central procurement Director for all procurements above $80,000.

DPS has also reviewed its internal procurement and contract management policies, guidance and templates which are currently going through an internal consultation process with the new suite of documents to be issued by the end of March 2015. Legal advice has been requested from the Australian Government Solicitor to ensure that DPS’ contract templates are accurate and comply with current Commonwealth requirements.

As detailed in the ANAO report, a key aspect of achieving better practice in procurement and contract management is a sustainable training program for its staff. As part of an ongoing training program that commenced in late 2014, DPS arranged for the APSC to deliver foundation training to key staff with procurement and contracting responsibilities. To ensure that all DPS staff with procurement and contracting responsibilities will receive this training, additional courses have been scheduled for April 2015. While this training will provide DPS staff with the baseline knowledge and skills required to perform their roles, specialised training will also be provided to staff performing more complex procurement and contracting activities as part the ongoing training programme.

With regards to the ANAO’s concerns around the weaknesses in DPS’ systems, DPS is implementing a Procure to Pay SAP solution, which will be used for all procurement and contracting activities. This is scheduled to be completed in June 2015. This solution will automate a number of manual procedures in the procurement process as well as enhance procurement and contract related records management as all contracts will be stored in the system. This will create a complete electronic auditable and controlled record of the source to pay process for all DPS procurement activity and as such address the ANAOs concerns in this area.

Asset Management

In order to develop a robust, comprehensive and risk based asset management plan for the next 10 years and beyond, the Government provided funding in the 2014-15 Budget to allow the commissioning of a Building Condition Assessment Report (BCAR) and a Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMP). Fundamental planning of this nature has not been done before in the building’s history. This work commenced in July 2014 and drafts of both documents have been delivered to DPS; these were made available to the ANAO during this audit. The plans will be finalised once Budget outcomes are known, allowing appropriate phasing of expenditure and prioritisation of the capital works drawing on the funding available and service continuity risk. These documents also provide the baseline information to allow the development and presentation of a Building Status Report to the Parliament in early 2015.

The BCAR and SAMP provide the foundations for developing a professional 10 and 25 year capital works programme for Parliament House including asset replacement, upgrading to meet relevant building standards and legislative requirements, maintenance and operating costs. As part of the SAMP, a comprehensive, risk assessed and prioritised work plan has been developed that underpins a detailed, independently cost assessed approach to Government for funding.

The SAMP and forward capital works programme are supported by ongoing work to revise project and asset management documentation and policies. Project management processes have been fully reviewed in 2014, with projects in flight re-assessed for scope, budget and timeframe validity, and a revised customer request process is already in place that requires two stage business case development for new projects not captured by the SAMP and approved capital works programme. This process ensures the consideration of, among other things, heritage advice in design development and delivery phases.

Management of Heritage Assets

Since the SFPALC inquiry, DPS has employed a team of heritage professionals that has significantly enhanced our in house heritage management capability. This team provides comprehensive advice on a range of matters, including on disposals and during project development.

To further bolster heritage management and awareness in the Parliament, a Conservation Management Plan and a Design Principles document have been commissioned. Work commenced in 2014 and continues on both of these seminal pieces of work. These will further inform and embed high quality heritage management practice across the department now and into the future, while capturing the principles articulated by the original architect and providing guidance on the appropriate evolution of the building over the coming decades. Once the Conservation Management Plan has been completed, DPS has publically stated that it will commission the completion of the Central Reference Document.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.49 |

To support the development of its Strategic Asset Management Plan, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services takes a more integrated and disciplined approach and develops:

DPS response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.60 |

To support proper consideration of heritage value when storing or disposing of assets, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services develops and delivers an ongoing training program that provides guidance about these matters to relevant staff. DPS response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.36 |

To improve its overall contract management and reporting capability, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services:

DPS response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 5.49 |

To strengthen contract management arrangements, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services:

DPS response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.5 Paragraph 5.52 |

To strengthen the management of retail licences, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services develops a retail strategy and operational plan that clarifies priorities for revenue generating opportunities and establishes a clear basis for monitoring retailer performance. DPS response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.6 Paragraph 6.20 |

To strengthen the monitoring and reporting framework, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Parliamentary Services:

DPS response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the role of the Department of Parliamentary Services in managing Parliament House and associated assets. The chapter also outlines the audit approach, including the objective, criteria and scope.

Introduction

1.1 The opening of the ‘new’ Australian Parliament House in 1988 was a landmark in Australia’s history. At that time, it was the largest building constructed in Australia. Recognised as a uniquely designed, functional building, Parliament House cost $1.1 billion to complete and had an intended life span of 200 years. Twenty-six years later, Parliament House, including its contents and surrounds, had an estimated value of $2.3 billion.18

1.2 Parliament House is a place of national significance with considerable heritage value. Mr Romaldo Giurgola, the architect of Parliament House, has commented that his task during design and construction was to focus on clarifying the principles that define the character and meaning of the building. These principles included:

first, the significance of the building as a democratic forum for the nation of Australia; second, making the process of government visible and accessible to the public; third, the building design as a symbolic sequence of spaces with reference to Australia’s historical and cultural evolution over time; and, finally, the design of Parliament House as a workplace which was intended to enhance the health and wellbeing of all occupants, which I think is important because it becomes a model for everyone to look to.19

1.3 While its primary function is as the meeting place of the Australian Parliament, Parliament House and precincts, also serve as a national venue for ceremonial functions, hosting state and visiting dignitaries and a variety of other political, community and social events. Parliament House also contains many historic documents and artworks, and a large part of the building is open to the public.

Department of Parliamentary Services

1.4 The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) has an important custodial role in managing Parliament House. Its primary responsibilities are to support the work of the Parliament, maintain Parliament House, and make the building and parliamentary activity accessible to the public. DPS provides a range of services including: broadcasting and Hansard; information and research; security; building and landscaping; and information and communications technology (ICT). DPS contracts the supply of many of these services to external providers and manages licence arrangements with several retail service providers that occupy space within Parliament House. These services include catering, banking and postal, childcare and physiotherapy. The department is also responsible for developing new systems and infrastructure, refurbishing Parliament House and managing its assets.

Structure and funding

1.5 DPS was established in 2004 following the amalgamation of the Joint House Department, Department of the Parliamentary Library and the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff.20 Under the Parliamentary Service Act 1999, the Presiding Officers (the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives) jointly administer DPS. The Secretary is responsible to the Presiding Officers for the efficient operation of the department.

1.6 In 2014–15, the department had approximately 700 staff21, and an annual budget of $165 million (comprising around $150 million in departmental funding and $15 million in administered funding).22 DPS funding decreased by 23 per cent between 2010–11 ($179 million) and 2013–14 ($138 million) but then increased by 20 per cent in 2014–15 (to $165 million).

1.7 DPS is one of four Parliamentary Departments, the other three being:

- Department of the Senate—provides the Senate, its committees, the President of the Senate and Senators with a broad range of advisory and support services related to the exercise of the legislative power of the Commonwealth. The parliamentary head of the Department of the Senate is the President of the Senate and the departmental head is the Clerk of the Senate.

- Department of the House of Representatives—provides services to support the conduct of the House of Representatives, its committees and certain joint committees, as well as a range of services and facilities for Members in Parliament House. The parliamentary head of the Department of the House of Representatives is the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the departmental head is the Clerk of the House of Representatives.

- Parliamentary Budget Office—established in July 2012 and provides independent and non-partisan analysis of the budget cycle, fiscal policy and the financial implications of proposals.

Parliamentary and stakeholder interest

1.8 Over a number of years, various aspects of DPS’ management of Parliament House have been the subject of parliamentary interest. In particular, in May 2011, Senators raised specific concerns regarding the disposal of Parliament House assets with potential heritage value, specifically two billiard tables from the staff recreation room. In response to the concerns raised by SFPALC, DPS conducted an internal audit in June 2011 and commissioned an external consultant to review asset disposal policies and practices within the department. The external review report of October 2011 noted improvements in departmental procedures for asset disposals, particularly in relation to assets or items of established or possible heritage value (referred to as the Tonkin Review).23

1.9 The department’s response to these matters led to a subsequent inquiry into the performance of DPS by the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee (SFPALC). The committee presented an interim report to the Senate in June 2012, and a final report in November 2012. The final report identified a wide range of issues relating to DPS’ employment practices, management of heritage assets and contracts, and arrangements for security and ICT.

1.10 SFPALC has continued to focus on the activities of DPS during Senate Estimates hearings, particularly its asset management (including heritage management) and contract management practices.

Asset management

1.11 As at 30 June 2014, DPS had responsibility for assets valued at around $2.3 billion when accounted for on a depreciated basis, with the most significant asset being the Parliament House building (valued at over $2 billion). The following aspects of asset management have been the subject of specific scrutiny by SFPALC: maintenance of Parliament House; heritage management; and disposal of assets.

Maintenance of Parliament House

1.12 In 2003, the former Joint House Department devised a maintenance plan for Parliament House. The objective of the plan was to maintain the standard of the building at a level of 90 per cent of new.24 According to the former Secretary of the Joint House Department, the ‘first 20 years or so of the building’s life would require little in the way of major engineering change. But between 20–30 years after occupation, major plant would require replacement and substantial funding’.25

Heritage management and disposal of assets

1.13 DPS is responsible for the protection and management of cultural and heritage assets, which were valued at $84.1 million as at 30 June 2014.26 While many of these assets, such as the rotational collection27, gifts collection, historic memorials collection and the architectural commissions28 are registered on the Parliament House Art Collection database29, some assets of cultural or heritage significance—referred to as moveable and semi-moveable assets—are not.30 SFPALC identified issues in relation to the management of assets that are not registered, as outlined in the following example.

|

Incomplete registering of Parliament House assets—terracotta pots The SFPALC inquiry outlined an example of the consequences of not having a comprehensive register of cultural and heritage assets. At the time of construction of Parliament House, around 1300 terracotta pots, which were an integral element of the global furniture collection, were acquired. Despite the significance of these pots, they were not listed on any asset register. In October 2011, following questioning during the SFPALC Estimates hearings, DPS identified that some 400 pots were missing from Parliament House. Subsequent anecdotal evidence from former employees suggested that they may have been disposed of by the former Joint House Departmenta. |

Note a: SFPALC, The Performance of the Department of Parliamentary Services, November 2012, pp.121–123.

1.14 In response to SFPALC’s concerns, the department undertook a survey in July 2011 of moveable and semi-moveable items of possible heritage value located within DPS work areas and not already managed as part of the Parliament House Art Collection and Library catalogue. The survey and assessment of the DPS items of potential heritage significance was completed in April 2013 and identified 170 new items with cultural or heritage value.31

1.15 In its final report in 2012, SFPALC indicated general satisfaction with the steps taken by DPS to implement the Tonkin Review’s recommendations, but noted ‘there is still some further work to be undertaken in relation to disposal practices and the recording of heritage and cultural assets in Parliament House’.32

Contract management

1.16 In 2013–14, DPS managed some 190 contracts, involving expenditure of $62.8 million in that year. These contracts covered a range of activities, including: building maintenance, renovations and upgrades; security; telecommunications and utilities; catering; and cleaning. While these contractual arrangements are primarily for the provision of services by private commercial entities, DPS also has contractual arrangements with other Australian Government agencies, such as for security services provided by the Australian Federal Police (with an estimated annual value of $10 million).

1.17 The SFPALC inquiry also raised a number of concerns regarding DPS’ contract management practices, with the inquiry report including 22 recommendations that were designed to improve the department’s performance. SFPALC’s report made specific reference to the following two DPS contracts:

- the contract covering the internal cleaning of Parliament House (valued at $3.8 million per year); and

- the contract for the catering of events, the staff dining room and Queen’s Terrace Café (for which DPS pays the catering contractor an annual management fee of $550 000).33

1.18 SFPALC queried the circumstances under which these contracts were entered into and DPS’ performance in monitoring and enforcing the contracts. The department accepted SFPALC’s recommendations, which were directed at improving the training and skills of DPS staff and reviewing the processes for developing and managing contracts. DPS also advised the committee that it would review its procurement and contract framework in 2013.

Previous audit coverage

1.19 DPS was one of the entities included in the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) 2005–06 performance audit of The Management of Infrastructure, Plant and Equipment. This audit assessed whether selected Australian Government entities were effectively supporting their business requirements through planning and managing the acquisition, disposal and use of their infrastructure, plant and equipment assets.34 The audit made five recommendations aimed at improving: policies and procedures; asset planning; asset acquisitions; the management of performance; and disposal planning.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Parliamentary Services’ management of assets and contracts to support the operations of Parliament House.

1.21 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- governance and administrative arrangements for asset and contract management were effective;

- processes and procedures for the maintenance and disposal of assets (including cultural and heritage assets) were sound; and

- processes were in place to ensure legislative compliance, delivery of expected products and outcomes, and value for money from contracts.

1.22 The audit scope did not include a review of assets related to ICT, broadcasting, art, the Parliamentary Library (such as Hansard), or the landscaped grounds. In assessing contracting, the audit focused on the management of contracts after they had been signed, but reviewed information on procurement to understand how DPS could achieve value for money when managing these contracts.

Methodology

1.23 In conducting the audit, the ANAO: reviewed DPS policy documents, guidelines, procedures and operational reports; and interviewed relevant DPS staff. A sample of contracts and assets from relevant registers and databases35 was analysed, and a survey of parliamentarians’ satisfaction with DPS services conducted jointly with DPS.

1.24 The audit methodology drew on the ANAO’s better practice guides on The Strategic and Operational Management of Assets by Public Sector Entities (September 2010) and Developing and Managing Contracts (February 2012).

1.25 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost of approximately $615 000.

Report structure

1.26 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Asset Management |

Examines the processes and procedures established by DPS to manage the assets of Parliament House. |

|

3. Management of Heritage Assets |

Examines DPS’ management of heritage assets, including in considering heritage value when making changes to Parliament House and disposing of assets. |

|

4. Contract Management Arrangements |

Examines the arrangements established by DPS to support the management of contracts for the operation and maintenance of Parliament House. |

|

5. Establishing and Managing Contracts |

Examines DPS’ effectiveness in establishing and managing specific contracts. |

|

6. Management Arrangements in the Department of Parliamentary Services |

Examines management arrangements supporting DPS’ asset and contracting functions, including in respect of the department’s substantial change agenda of recent years. |

2. Asset Management

This chapter examines the processes and procedures established by DPS to manage the assets of Parliament House.

Introduction

2.1 The Parliament House complex occupies a 35 hectare site, has a total floor area of 250 000 square metres, with around 4500 rooms, public areas and retail outlets across four levels. In addition to the building fabric, Parliament House contains over 100 000 maintainable assets, including plant, fixtures and fittings and 32 hectares of landscaped open space. As the building operator (on behalf of the Australian Parliament) DPS is responsible for building management, which is undertaken using a combination of outsourced service contracts and in-house staff and resources.

2.2 To support the management of Parliament House assets, DPS has established a computerised asset management system that incorporates an assets register. This register contains details of some 16 500 groups of items. The largest single asset is the land on which Parliament House is sited (valued at $50 million). The building structure and major supporting systems are the largest class of assets managed by DPS (with a combined total value of $2.8 billion replacement basis and $2 billion on a depreciated replacement basis).

2.3 The significant asset classes managed by DPS are outlined in Table 2.1 (on the following page). The table also demonstrates that the building structure represents around 85 per cent of the total value of DPS assets. The asset classes listed in Table 2.1 are supported by a number of different asset systems36, with each asset system having a different life cycle.

Table 2.1: DPS asset profile, 2013–14

|

Asset Class |

Replacement Value |

Depreciated Value |

Per cent of Total (Replacement Value) |

|

Building structure and major supporting systems |

2 792.2 |

2 085.0 |

84.9 |

|

ICT equipment |

155.4 |

52.4 |

4.7 |

|

Furniture and fittings |

125.3 |

20.9 |

3.8 |

|

Art collection |

84.5 |

84.5 |

2.6 |

|

ICT systems and software |

65.4 |

20.8 |

2.0 |

|

Land |

50.0 |

50.0 |

1.5 |

|

Library collection |

11.8 |

4.3 |

0.4 |

|

Other (includes digitisation of Hansard records and low value portable items) |

5.6 |

4.3 |

0.2 |

|

Total |

3 290.2 |

2 322.2 |

100.0 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS information.

Note: Figures have been rounded.

2.4 Given the broad variation in the class, economic life and scale of assets managed, it is important for DPS to have in place an appropriate framework to track, manage, repair or replace each asset over time. Ideally, asset management will be incorporated into an organisation’s corporate and strategic planning to assist in: planning expenditure for new assets; the repair and replacement of existing assets; and their operation.37

2.5 The ANAO examined DPS’ asset management arrangements including whether the department had:

- an asset management strategy that integrated its strategic objectives and asset portfolio to meet program delivery requirements;

- a sound framework and processes for conducting capital works;

- comprehensive asset management policies and procedures;

- monitored the condition of key assets; and

- arrangements for maintaining assets in good working order.

Asset management strategy

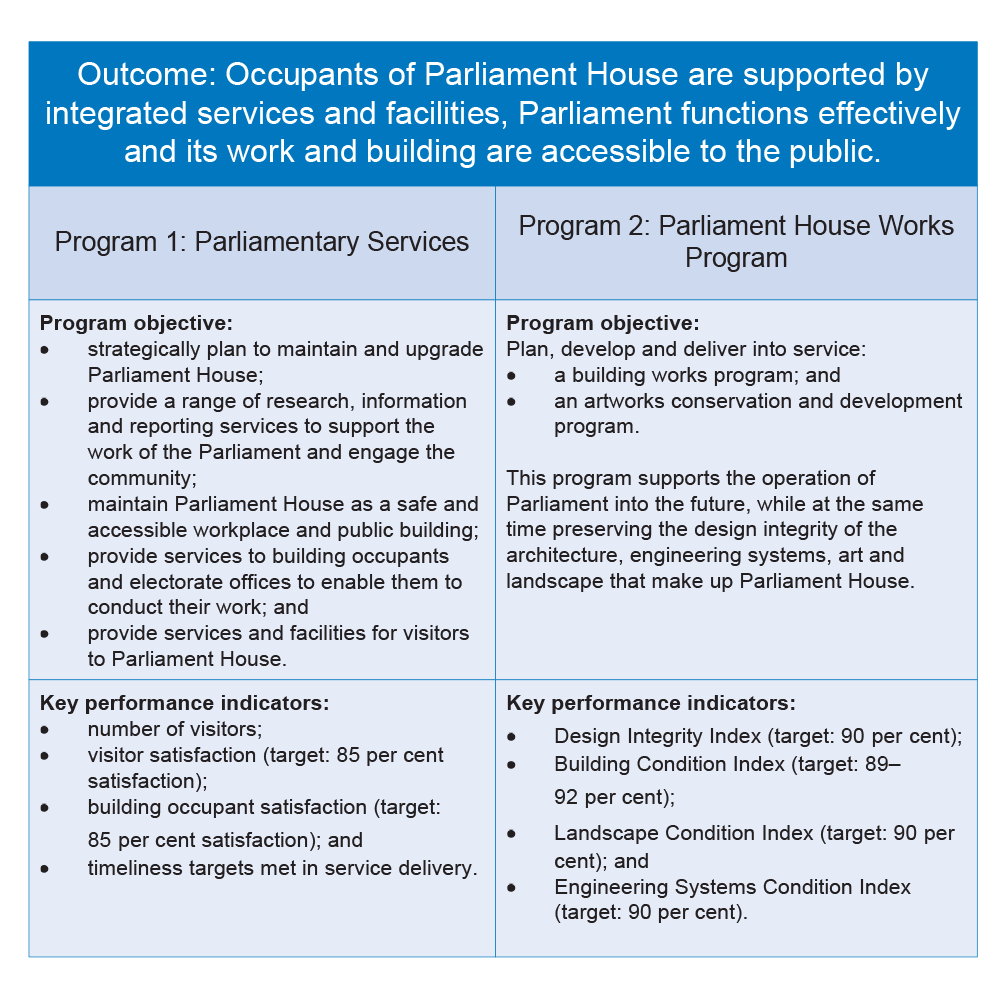

2.6 For those entities with specialist or high-value asset portfolios, such as DPS, an asset management strategy should describe how an entity’s strategic intent will be implemented to meet the service delivery needs as it relates to the asset portfolio.38 Managing the assets of Parliament House is one of DPS’ primary program delivery requirements and represents one of two programs under the DPS Outcomes and Programs Framework (discussed in Chapter 6). It is also one of the department’s five key results areas in its Corporate Plan 2012–14.

2.7 In 2003, the former Joint House Department developed an asset maintenance and replacement plan that would be required over the life of the building. The plan outlined, in five-year intervals, the expected life of each asset system of Parliament House, such as the electrical and heating, ventilation and cooling systems. Under the model developed by the Joint House Department, the building’s main asset systems would require replacement after 25–30 years of occupation. At the time the plan was developed, the Joint House Department reported that:

The development of a 100-year plan provides … a long-term view of funding required to ensure parliamentary processes are not interrupted and to preserve the value of Parliament House throughout its life cycle. In particular, the plan identifies funding spikes and allows sufficient time for proper planning for these occurrences.39

2.8 Notwithstanding the importance of this function, DPS is yet to develop an asset management strategy or to update the 2003 plan, nor does the departmental division responsible for the management and maintenance of the building have a current business or operational plan. While the 100-year asset maintenance and replacement plan provides a guide for when asset systems are likely to require replacing, it does not include detailed information on priorities, roles and responsibilities or the current condition of the asset systems. DPS has also developed a rolling five to 10 year maintenance and replacement plan but this plan also lacks the detailed information required for effective strategic asset management.40

2.9 Within the context of the SFPALC inquiry, DPS commissioned a review of its Asset and Capital Management Framework. The review’s report, provided in January 2013, concluded that considerable work was required to develop a capital management plan. The report made eight recommendations covering organisational structure, funding arrangements, governance, strategic capital planning, ICT assets, systems processes and procedures, and the capital 10-year rolling plan.

2.10 The review found ‘significant deficiencies in each of the systems that would normally provide input into a robust strategic capital management plan’.41 The review also identified that:

Planned capital works are funded by an administered appropriation. The absence of engineering expertise from 2007 meant that the driver for project bids was the available funding rather than the strategic plan. Accordingly, approved projects during this period appear to be ad-hoc in nature with little or no robust engineering justification.

The replacement/refurbishment plans form the foundation of a capital management plan. With the exception of broadcasting assets, DPS has not developed robust asset replacement/refurbishment plans covering the short, medium and long term horizons.42

2.11 Of the eight recommendations, six were related to Parliament House assets and the others related to ICT and broadcasting assets. DPS initially intended to implement these recommendations by December 2013, pending the successful recruitment of executives to key leadership positions following an organisational restructure in early 2013. These executive positions were not filled until early 2014, and DPS does not expect all recommendations to be implemented before the end of the 2014–15 financial year.

Developing a strategic asset management plan

2.12 When Parliament House was commissioned in 1988, it was planned that, from 2013, the custodians of Parliament House would need to undertake a program of substantial replacement and upgrading of key building infrastructure. While repair and maintenance work has been undertaken since inception, the replacement and refurbishment of assets and asset systems has not occurred in line with initial expectations. DPS’ asset register indicates that 90 per cent of the asset systems associated with the building structure have not been replaced since 1988.

2.13 DPS has recognised the need to undertake a program of repair and maintenance work and has sought to secure additional funding for this work. In 2013–14, the department put forward a funding proposal in two stages. The first stage involved a request for funding to develop a building condition assessment report (BCAR) and thereafter a strategic asset management plan (SAMP). In the 2014–15 Federal Budget, DPS was provided with $1.67 million to undertake the first stage (which included the development of the BCAR and SAMP).43 The extent of funding sought in the second stage was to be informed by the results of the BCAR and the SAMP.

2.14 In July 2014, DPS commissioned a contractor to conduct an assessment of the condition of the building and its elements and develop a SAMP for Parliament House.44 In November 2014, DPS was provided with a draft BCAR, which included an assessment of the current physical condition and operating performance of building elements of Parliament House.45 The draft report also included a projected 10-year and 25-year expenditure profile aimed at supporting the delivery of services. The profile includes projects to be undertaken through the capital works program from 2015–16, based on identified priority according to the condition of each of element.

2.15 The draft building condition assessment report indicated that many of the major structural or operational elements of Parliament House were within acceptable physical and operating performance levels. However, proactive actions, including renewals, upgrades and replacement works were required by DPS to prevent the assets from deteriorating and becoming ineffective in supporting Parliament’s operations. Consequently, significant improvements are required in the department’s asset management sub-plans (covering acquisition, operations, maintenance and disposals), systems and processes. Capital works also need to be better integrated with replacement and maintenance activities, to restore Parliament House to optimal condition.

Capital works program

2.16 The initial planning and acquisition phases for Parliament House assets occurred in the 1980s when the building was constructed. To maintain the building to an appropriate standard, DPS is appropriated funds each financial year through the budget process, for an investment program in new and replacement assets. The Parliament House works program is intended to support the operation of Parliament into the future, while at the same time preserving the design integrity of the architecture, engineering systems, art collections and landscape that make up Parliament House.

2.17 DPS manages the administered appropriation for the Parliament House works program to fund an annual program of planned capital works, as shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Administered appropriation and annual expenditure on the Parliament House works program, 2010–11 to 2014–15

|

Year |

Administered Appropriation ($’000) |

Amount Spent ($’000) |

|

2010–11 |

$28 383(1) |

$20 128 |

|

2011–12 |

$24 432 |

$34 825(4) |

|

2012–13 |

$12 896 |

$11 635 |

|

2013–14 |

$20 437(2) |

$9 468 |

|

2014–15 |

$15 482(3) |

– |

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS portfolio budget statements and annual reports.

Note 1: Includes an additional $18.3 million to upgrade physical security over two years.

Note 2: Includes an additional $6.3 million for safety work and $725 000 for disability access upgrade.

Note 3: Includes an additional $1.7 million for Parliament House maintenance and asset replacement assessment and strategic review.

Note 4: The additional expenditure in 2011–12 was of unspent funding from 2010–11 relating to upgraded physical security. While planning to spend $30.7 million in 2010–11, DPS spent $20.1 million.

2.18 DPS advised the ANAO that the significant underspend in 2013–14 was ‘primarily related to a considered slow-down of capital expenditure, to review and reset the capital prioritisation process.’ DPS further advised that responsibility for building management was assigned to a senior executive officer in January 2014 and one of the primary objectives upon their commencement in the newly established role was to evaluate the program of work being undertaken through the capital works plan to:

ensure DPS’ administered capital budget was efficiently and effectively utilised in maintaining the building, through scheduled maintenance and new capital works. The review lead [sic] to an immediate reprioritisation of capital works and maintenance, and also to an assessment of the workforce capability used to deliver such works. The review of this workforce meant the reprioritisation of works to focus on urgent and unavoidable projects…This mode of operation remained through the second half of 2013–14, meaning DPS’ administered capital budget remained underspent in that year, but remained available to the department in 2014–15 when an effective and efficient staff model could actively pursue the department’s strategic programme of works.

Identification and approval of projects

2.19 Prior to July 2013, all projects on the capital works plan (CWP) were subject to the DPS request approval process. This process required a business case and project proposal (using a standard template) to be submitted for consideration and approval by the Strategy and Finance Committee. Approved proposals were subsequently included on the CWP.

2.20 In July 2013, the Strategy and Finance Committee was disbanded and DPS commenced a process of reviewing all capital works projects. The request approval process was also reviewed. For the 2013–14 and 2014–15 CWPs, all requests for new projects were considered by the Building Management Division Head and the Secretary.

2.21 In September 2014, DPS released a revised process for considering requests for work to be undertaken for maintenance of, or upgrades to, Parliament House.46 Combined with the strategic direction and information gained from the BCAR and SAMP, the revised request process has the potential to provide DPS with greater control over the asset acquisition process and allocation of capital funds. However, it will also be important for the department to strengthen its risk management to ensure that it formally assesses and manages the associated risks of the projects, both individually, and as a whole, to support the achievement of DPS program objectives.47

Determining priorities for the 2013–14 and 2014–15 capital works plans

2.22 To inform the development of the 2013–14 CWP, DPS reviewed all projects that had been included on the 2012–13 CWP. As a result, 19 of the 76 projects included on the 2013–14 CWP were either re-prioritised, consolidated or placed on-hold pending the outcome of the BCAR and the SAMP. This trend was accentuated in 2014–15, when 41 projects were on hold, 17 were underway and five projects were completed by October 2014.48 Further, no additional or new projects were listed on the 2013–14 CWP or the draft 2014–15 CWP.

2.23 The projects listed on both the 2013–14 and draft 2014–15 CWPs included a priority rating of critical, important or discretionary, and are outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Capital works project priorities, 2013–14 and 2014–15

|

Project Priority

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

||||

|

On hold |

Total on CWP(1)

|

On hold |

Total on CWP

|

|||

|

(No.) |

(%) |

(No.) |

(%) |

|||

|

Critical |

1 |

(5%) |

5 |

5 |

(12%) |

16 |

|

Important |

4 |

(21%) |

21 |

18 |

(44%) |

23 |

|

Discretionary |

14 |

(74%) |

42 |

17 |

(41%) |

25 |

|

Completed |

0 |

(0%) |

6 |

0 |

(0%) |

6 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

(0%) |

2 |

1 |

(2%) |

6 |

|

Total |

19 |

(100%) |

76 |

41 |

(100%)1 |

76 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS information.

Note 1: Does not add to 100 due to rounding.

2.24 However, the basis for determining the priority was not documented and it was not apparent from departmental records why some projects listed as critical had been placed on hold or had their implementation extended. DPS advised the ANAO that the project priority was determined ‘by the relevant project officers as they arose. Upon commencement of the First Assistant Secretary, Building Management Division, all items were subject to review and reprioritisation, which is reflected in the 2014–15 CWP’.

Future capital works programs

2.25 The draft BCAR indicates that the average yearly expenditure on capital works over the next 10 years is expected to be around $28.9 million49, with the peak of the expenditure being in the first five years ($187.7 million). The draft BCAR and SAMP include information that will better inform the development of future capital works programs and, as a result, have the potential to bring greater rigour to DPS’ planning and delivery of works projects. Nevertheless, throughout the remainder of 2014–15, a key consideration for the department will be to progress those projects assessed as having a higher priority (critical and important).

Asset management policies and procedures

2.26 In April 2010, DPS prepared a discussion paper to inform the development of a systematic approach to the ongoing management of Parliament House assets and associated capital investment programs. In July 2011, the discussion paper became the basis for a governance paper, which outlined DPS’ policy and high-level procedures for maintaining Parliament House assets.

2.27 The document has not, however, been updated to reflect DPS’ changed organisational and administrative arrangements, including roles and responsibilities for the development and approval of the capital works plan.50 The paper also refers to the Strategic Plan 2010–13, rather than the Corporate Plan 2012–14 and makes limited reference to risk management responsibilities, service level expectations, specific asset maintenance plans or asset replacement (for example, there is no reference to the 100 year asset replacement plan). While the governance paper may provide an overarching policy for managing and maintaining Parliament House assets, it does not provide an appropriate basis to inform the management of the significant range of assets for which DPS is responsible.

Supporting guidelines, policies and procedures

2.28 In April 2014, DPS commenced a review of its governance documents, which includes guidelines, policies and procedures relating to governance generally and human resources and finance more specifically. The review identified that:

- 58 per cent of documents were not current or had expired;

- 16 per cent of documents were due for review; and

- 25 per cent of documents were current.

2.29 The ANAO identified that DPS’ governance documents relating to asset management included links to 21 supporting policies and procedures. However, only three of these were current. The remaining 18 (or 86 per cent) had either expired, would benefit from updating51 or were being withdrawn. DPS has subsequently allocated responsibility for updating and reviewing specific governance documents to relevant departmental branches, and outlined the requirement to update and review all policies and procedures.

Monitoring the condition of assets

2.30 DPS has four asset custodian indexes that were designed to monitor the condition of Parliament House assets. Each index is supported by a defined methodology and performance targets that were developed by consultants and the former Joint House Department. The results are included in detailed reports provided to the DPS executive, and an annual score for each index is calculated and reported in the DPS annual report. Each index measures the condition of aspects of Parliament House assets and is based on the condition of the assets over time compared to the original condition or from when Parliament House was new. The indices, target, and a description of the measure and methodology are outlined in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Parliament House asset condition indices

|

Index |

Target |

Description |

|

|

Design Integrity Index |

90% |

Developed in 2001, the index measures the current condition of Parliament House and the precincts expressed as a percentage of the original built form. In particular, it measures the extent to which change within Parliament House and the precincts impacts upon the original design intent. Procedures to calculate the annual index include:

|

|

|

Building Condition Index |

90% |

Developed in 1993, the index measures the current condition of the building fabric of Parliament House, expressed as a percentage of the original condition. All eight zones of the building are inspected over a 12-month period with the exception of high-profile areas (for example special suites and public areas) that are inspected every six months. |

|

|

Engineering Systems Condition Index |

90% |

Developed in 2000 the index measures the current operation and condition of the engineering systems in Parliament House against the expected decline of those systems through their life cycles. The system of scoring has been designed so the target is achieved if all systems are ageing as expected. The results are based on data and reports collected over the course of the year. The reports are prepared by external contractors or industry specialists, for example, monthly fire system testing reports. The data are referred to an external consulting engineer for review and the provision of a report and score for each element from which the overall score is derived. |

|

|

Landscape Condition Index |

90% |

Developed in 2000, the index measures the current condition of the landscape surrounding Parliament House, expressed as a percentage of the total possible condition. The score is a result of inspections and assessments of the landscape by in-house gardening staff each October. |

|

Source: DPS, Portfolio Budget Statements, 2014–15.

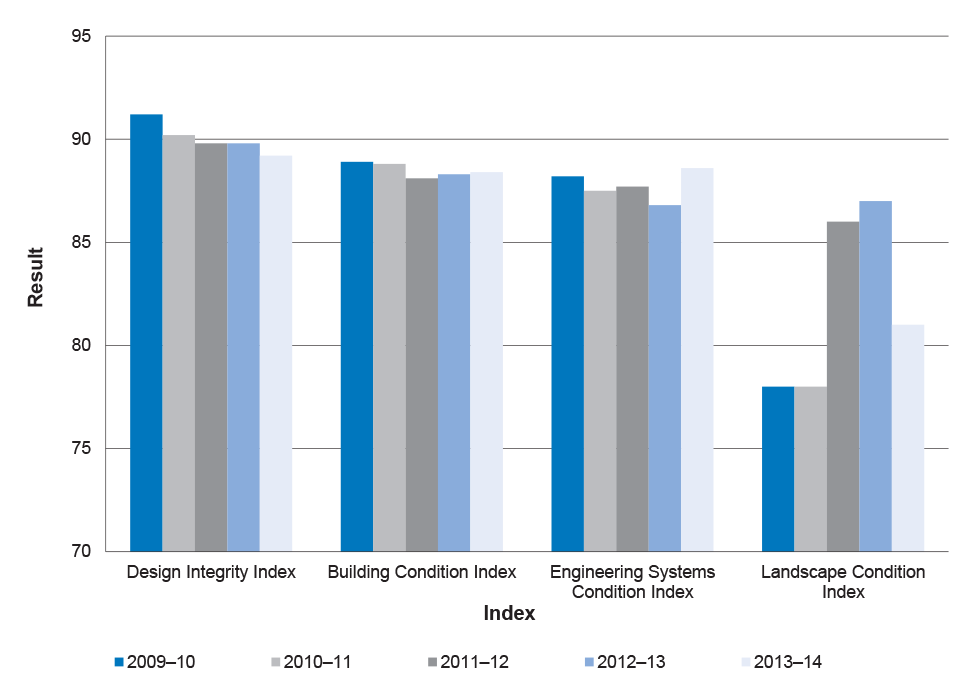

2.31 The ANAO reviewed the results for the indices reported in annual reports since 2009–10. All of the indices have been below their 90 per cent target since 2010–11, as demonstrated in Figure 2.1. The Building Condition Index and Design Integrity Index have both been gradually declining, in part due to the ageing of the assets as well as changes in work practices (such as increases in the number of photocopiers and multi-function devices located throughout the circulation spaces).

Figure 2.1: Parliament House asset condition indexes, 2009–10 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS annual reports.

2.32 In 2012–13, the Design Integrity Index report made 12 recommendations aimed at improving the condition of Parliament House compared to the design intent. To date, DPS has not tracked whether recommendations arising from design integrity inspections have been implemented.

2.33 The results from the Building Condition Index (which is reported quarterly) have been used to inform decisions on major capital projects for renewal and replacement of assets, as well as maintenance activities. Between July 2008 and April 2014 there were 81 recommendations aimed at improving the building condition. Of these 81 recommendations:

- fourteen led to major projects. For example, the repairs to the plaster ceiling and walls in the Great Hall skylight;

- twenty-one were reported as being addressed and consequently contributed to improvements in the Building Condition Index;

- thirty-one were uncertain, as there was no detail in the assessment reports about their implementation; and

- fifteen had only recently been identified and no outcome had been recorded at the time of the audit.

2.34 The results from the Engineering Systems Condition Index have also been used to identify systems for replacement.52

2.35 As at October 2014, DPS advised that it was reviewing all the indexes to assess the validity of the existing process and the relative value of each index methodology. This work was being undertaken together with other initiatives (such as the SAMP and development of a Conservation Management Plan) to improve DPS’ asset management framework.

Maintaining assets

2.36 Maintenance is a critical activity in the life cycle of an asset, with poor maintenance often leading to a shorter useful life than that envisaged in design specifications.53 The Building Management Division within DPS is responsible for appropriately maintaining Parliament House. This includes repairs and maintenance to the building structure, fabric and finishes and all engineering services such as air conditioning, lighting, plumbing, hydraulic services, movement systems (such as elevators) and waste disposal. The annual cost of maintenance for Parliament House (from 2008–09 to 2013–14) is outlined in Table 2.5 and has increased considerably over this period.

Table 2.5: Parliament House maintenance costs, 2008–09 to 2013–14

|

Year |

Maintenance Expenditure |

|

2008–09 |

$18 696 900 |

|

2009–10 |

$22 811 273 |

|

2010–11 |

$23 435 118 |

|

2011–12 |

$21 680 522 |

|

2012–13 |

$23 217 730 |

|

2013–14 |

$25 647 274 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS information.

2.37 The former Joint House Department and DPS have conducted various reviews over the years to determine the efficiency and effectiveness of maintenance activities for Parliament House.54 Broadly the findings and recommendations have been consistent across these reviews, including:

- concerns of senior managers and maintenance staff about ensuring the Parliament House building and its surrounds are effectively maintained and are fit-for-purpose for the next 200 years;

- the importance of enhancing and developing leadership and management skills as well as clear, transparent and consistent communication;

- strengthening maintenance planning and scheduling and possible integration with the building information function; and

- enhancing risk-based maintenance management and aligning this to maintenance priorities, focusing more on areas of genuine risk.

2.38 The approach adopted by DPS to respond to the findings and recommendations from the various reviews has, however, been variable. The department was unable to provide documentation to demonstrate the actions that it had taken to address review findings and recommendations. Further, there was limited documentation to demonstrate whether the costs and benefits of outsourcing compared to the delivery of services in-house had been considered on a systematic basis.

2.39 DPS’ April 2014 contract register attributed 22 contracts to ‘maintenance’. These contracts include services such as the provision of: painting maintenance; fire systems maintenance and monitoring systems; maintenance and repair of the lifts; cleaning; gas and electricity; furniture conservation; and carpet storage and transportation. The basis on which decisions were taken to outsource services was not clear, while others continued to be delivered by in-house staff. The absence of a clear process to inform maintenance decision making, in particular when determining the merits of contracting out services, means that DPS is not in a position to clearly demonstrate that it is making optimal use of available resources to meet program delivery requirements.

2.40 The draft BCAR provides an indication of the expected costs involved in updating all elements of the building to maintain the delivery of services and operation of Parliament House, however, it does not include a consideration of the costs involved in regular maintenance. The findings of the BCAR also indicate that a significant amount of maintenance is required to repair and address wear and tear on the building fabrics, such as the timber floor finishes, paintwork and carpet. Other elements are likely to require maintenance further into their lifecycle if they are subject to regular attention from DPS. A focus on maintaining elements that require non-urgent updating will provide DPS with the opportunity to efficiently phase the capital works and replacement activities.

2.41 In addition to the capital works program that will be undertaken as a result of the BCAR, there would also be merit in DPS reviewing the maintenance function as part of a reassessment of its responses to previous reviews. Such reassessment should include the mix of in-house and contracted- out services, to determine whether these arrangements represent value for money and identify opportunities for additional efficiencies.

Maintenance management system

2.42 DPS uses a maintenance management system (MMS) for its building maintenance. This database is used to manage the asset master data, maintenance task lists, plans, notifications and work orders.

2.43 Maintenance work orders are used to carry out maintenance tasks and to capture information about the condition of the asset and maintenance performance. Maintenance work orders are grouped into the following three categories: preventative; planned; and unplanned. Preventive maintenance work orders are created for specific dates via maintenance plans and their scheduling functions. Planned maintenance work orders are created as a result of inspections and from maintenance plans. Unplanned maintenance work orders result from unforeseen plant or system failure, which require a maintenance task to be performed immediately. The ANAO analysed the data from the MMS for 2013–14 to determine the number of completed work orders by category, and these are outlined in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6: Work orders scheduled and completed, 2013–14

|

Type |

Scheduled |

Completed |

% of scheduled completed |

|

Preventative |

21 884 |

18 689 |

85 |

|

Planned |

3 548 |

3 264 |

92 |

|

Unplanned |

3 911 |

3 875 |

99 |

|

Total |

29 343 |

25 828 |

88 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DPS information.

2.44 As outlined in Table 2.6, the significant majority of maintenance activities scheduled by DPS are preventative (75 per cent). A focus on preventative maintenance is important when the tolerances for unscheduled maintenance and its impact are low, which would be expected in a working parliamentary complex.

2.45 The ANAO’s analysis of DPS data identified some limitations in the recording of actual completion (closure) dates for maintenance activities. In particular, a review of MMS data records for 2013–14 revealed that, for 12 per cent of maintenance activities, an end date had not been determined. The failure to close off work orders in a timely manner increases the risk of duplicated effort where tradespeople are assigned to undertake maintenance work that has already been completed, but not reported. It also impacts on DPS’ ability to accurately monitor maintenance that is being undertaken as planned, and reduces the quality of the data in departmental systems and the value of this data for management reporting.

Monitoring and reporting of maintenance activities

2.46 DPS advised the ANAO that management reporting was prepared in relation to the acquisition and maintenance of Parliament House assets. While DPS is using the MMS to underpin its planning and delivery of maintenance activities for Parliament House assets, it is not using the system to generate useful management information that has the potential to better inform both strategic and operational maintenance activities. There would be value in DPS developing regular reporting to inform management on the efficiency and effectiveness of current maintenance arrangements and to determine whether current approaches to maintenance are sufficiently robust to maintain Parliament House to the required standard. The information generated would also better position DPS to determine future maintenance needs.

Conclusion

2.47 DPS’ asset management framework has been subject to considerable review and change in response to the SFPALC inquiry. To bring together the key elements required for effective asset management, the department is developing a SAMP, following the completion of the BCAR. These processes should provide a useful baseline for assessing the condition of Parliament House assets, particularly as many engineering assets are reaching a critical stage in the asset management lifecycle. These processes should also provide a way forward in managing Parliament House assets and prioritising acquisition, replacement, refurbishment, and maintenance expenditures.