Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter Project-Air 87

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of management of the procurement of a major, new capability for the ADF by the DMO and Defence. The audit reviewed the initial capability requirements and approval process; analysed the contract negotiation process; and examined management of the Acquisition and Through-Life-Support Contracts. Coverage of the audit extended from development of the concept for the requirement, to acceptance of deliverables in the period prior to the award of the Australian Military Type Certificate (see shaded area of Figure 1). The audit fieldwork was undertaken during the delivery phase of the Project, following delivery of ARH numbers 1, 2 and 5.

Summary

Background

1. The Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter (ARH) Project Air 87 (the Project) was approved to provide for a new, and significant all weather reconnaissance and fire support capability for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The Project has contracted for delivery of 22 aircraft, with supporting stores, facilities, ammunition and training equipment. The first four aircraft are being manufactured in, and delivered from France; the remaining 18 aircraft are being manufactured in France, and assembled in Brisbane. Australianisation of the weapons and communications systems is a differentiating characteristic of the Australian Tiger ARH, compared to the French Tiger Variant.

2. Major Capital Equipment Projects, such as Project Air 87 require considerable planning to successfully transition a capability from acquisition to in-service operation. This includes integration of training, logistics and operational requirements using available staff and resources. Forward consideration of these issues in administering the acquisition phase, in cooperation with the ADF, leads to the commissioning of a reliable and supportable capability, as complex as the ARH. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO)1 is required to manage a high level of risk, using calculated assessments, mitigated where appropriate, and in all cases, managed and monitored on an ongoing basis. Inevitably, in some circumstances, the DMO may not fully meet the outputs required of it. The DMO advised the ANAO that if there were no shortfalls, the DMO might rightly be criticised for having an insufficient risk appetite.

3. This acquisition of helicopters was to be based on an ‘off-the-shelf'2 procurement, representing a low risk to Defence. It was intended that the Australian Tiger ARH Project would follow the French and German programs, which the DMO 3advise were, at the time of making the choice to procure Tiger aircraft, 18 months in advance of the Australian program.

4. The DMO advised that, flying Tiger helicopter prototypes had been demonstrated prior to the award of the Australian Acquisition Contract in December 2001, although full certification, and design acceptance by the French Government, had not then been accomplished. In 2003, the DMO became aware of production and acceptance delays with supplying Tiger helicopters to France and Germany. The French Government accepted its first production aircraft in March 2005, four months after the DMO.

5. The lead Australian Tiger ARH aircraft (ARH 1 and 2) are the first of this type of aircraft to undergo production acceptance by any nation's Defence Force, and are being delivered into service as an aircraft type more developmental than that which was originally intended by the initial requirement4. Consequently, the DMO has been obligated to make its own assessment of over 71 unresolved design issues. 5

6. The 1998 Defence Equipment Acquisition Strategy requirement for the capability stipulated that first prototype aircraft should be accepted by January 2003, with the first production aircraft delivered in May 2003. The original aim was to provide for one operational squadron by July 2006, with a second operational squadron by December 2007. In finalising the Defence 2000 White Paper6, the Government decided that the In Service Date for the helicopters for Army should be December 2004. To advance the approval process, Government considered the Project in August 2001 for contract signature later that year.

Acquisition and Through-Life-Support Contracts

7. In 2005–06, this Project is budgeted to have the largest capital expenditure (totalling $440 million) of all DMO's 240 projects. The current total Project budget is $1.96 billion. In March 1999, the Government approved the Project with a budget of $1.58 billion. Since then, the Project budget has increased by $275.92 million as a result of price index variations; $186.46 million as a result of currency exchange rate variations; and decreased by $90.96 million, as a result of the transfer of funds to other requirements.

8. In December 2001, Defence negotiated, and signed both an Acquisition Contract of $1.1 billion, and a Through-Life-Support Contract, with a fixed price element of $410.9 million, with Eurocopter International Pacific (now called Australian Aerospace Limited, and referred to in this report as the Contractor). Through-Life-Support covers a three year pre-implementation phase (prior to In-Service Date 7 in December 2004), and a 15 year In-Service period, which took effect in December 2004, coinciding with delivery of the first two helicopters. Project funding from Air 87 caters for the first five and a half years of the Through-Life-Support period (which includes the pre-implementation phase), up until 2006–07. Defence advised the ANAO that funding to the value of $310.32 million is to be provided through capability sustainment funds for the Through-Life-Support Contract after 2006–07.

9. The Acquisition Contract comprises 126 milestone payments, and monthly progress payments based on the Contractor's Earned Value Management System (EVMS). The milestone payments, which are paid upon completion of a significant Project achievement, account for 60 per cent of the total sum. The remaining 40 per cent of payments are to be made following the DMO assessment of completed work scope in the manner of earned value payments.

Technical and Operational Airworthiness

10. The two limbs of the Airworthiness Regulatory System are:

- Technical Airworthiness: which relates to regulation, design, production and maintenance operations to assess suitability for their intended operational roles; and

- Operational Airworthiness: which relates to regulation of flying operations and the overall assessment of risk in those roles through adequate management of issues such as operational procedures, operational risk, crew qualifications and currency, flight authorisation and aircrew training. 8

11. The delivered Tiger ARH system is required to attain compliance, and remain compliant with the Defence Technical and Operational Airworthiness Regulations. The nature of the ARH Acquisition Contract provides for the incremental delivery, and acceptance by Defence of the aircraft to progress development of the capability into full service under a Special Flight Permit9. The Special Flight Permit granted to the first six ARH aircraft was approved in December 2004. The Special Flight Permit enabled these aircraft to operate with constrained operations to progress development of the delivered capability, until the award of an Australian Military Type Certificate.10

12. The Tiger ARH system was awarded an Australian Military Type Certificate and Service Release on 26 October 2005, with limitations, certifying the system's compliance with the airworthiness and support requirements documented in the Defence Technical and Operational Airworthiness Regulations. 11 This compliance takes into consideration the ability of the training and support systems to support the Tiger ARH system for its intended activities.

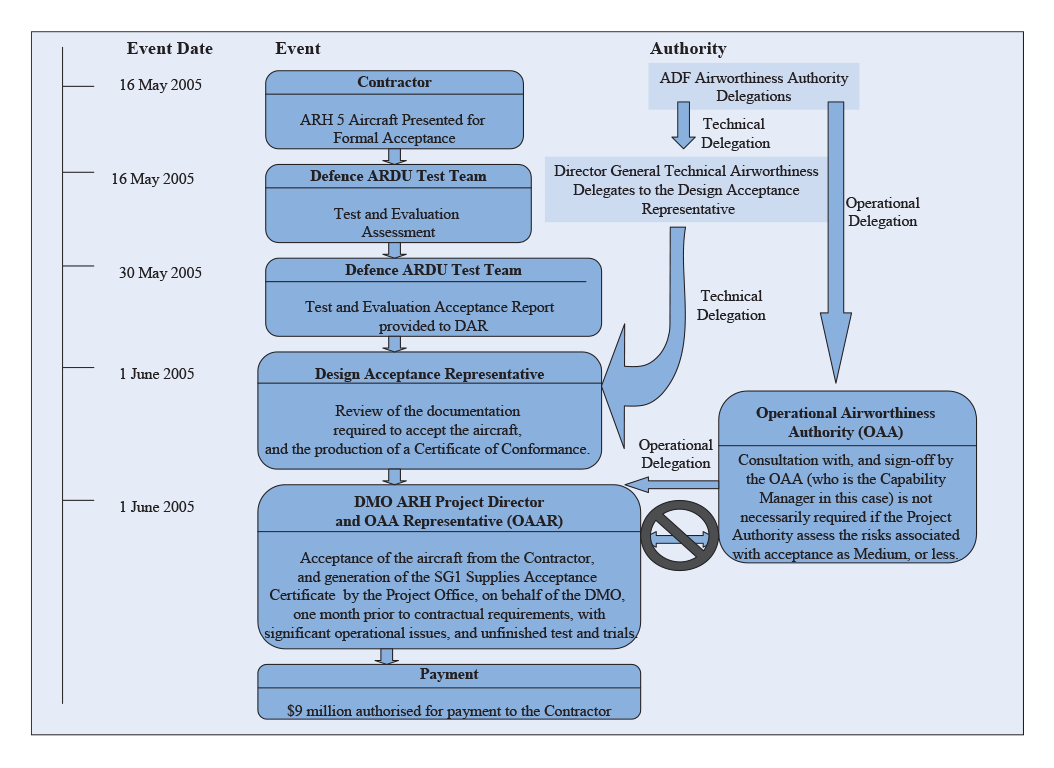

13. The ADF Instruction, relating to airworthiness management, defines the process associated with certifying a military aircraft for flight under the rules governing State registered aircraft.12 The airworthiness certification process that was followed is shown in Figure 1. 13

Figure 1 Airworthiness Management Process adopted for the Tiger ARH: October 2005

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence and DMO documentation.

Audit approach

14. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of management of the procurement of a major, new capability for the ADF by the DMO and Defence. The audit reviewed the initial capability requirements and approval process; analysed the contract negotiation process; and examined management of the Acquisition and Through-Life-Support Contracts. Coverage of the audit extended from development of the concept for the requirement, to acceptance of deliverables in the period prior to the award of the Australian Military Type Certificate (see shaded area of Figure 1). The audit fieldwork was undertaken during the delivery phase of the Project, following delivery of ARH numbers 1, 2 and 5.

Overall audit conclusions

15. Defence had intended that the ARH aircraft was to have been an ‘off-the-shelf' delivery of proven, operational technology, lowering the risk of schedule, cost and performance shortfalls. The ARH acquisition transitioned to become a more developmental program for the ADF, which has resulted in heightened exposure to schedule, cost and capability risks, both for acquisition of the capability, and delivery of through-life support services. The lack of operational experience in maintaining this capability in other Defence Forces has meant that original cost estimates associated with the through-life support were immature, and exposed Defence to significant future budgetary risks.

16. As at October 2005, the DMO had expended $855.45 million on the Project, representing: payment for four aircraft out of the 22 aircraft to be delivered; design work; and a proportion of: external stores; facilities; training deliverables; and the required support equipment. Of this expenditure, $731 million has been expended on the Acquisition Contract in accordance with the Acquisition Contract's Milestone Payment and Earned Value Management System, representing expenditure in the order of 60 per cent of the total value of the Acquisition Contract.

17. The ADF has not had an effective Tiger ARH capability and has had a limited ability to train aircrews, 12 months after accepting the first two production aircraft (ARH 1 and 2) in December 2004. At the time of acceptance of ARH 5 in June 2005, the aircraft was not fit for purpose against all the Contracted requirements (as was also the case with ARH 1 and 2)14. The DMO accepted the first three aircraft in a state that did not meet contractual specifications. However, the DMO did not withhold part payment from the corresponding milestone payments for production acceptance, even though the Acquisition Contract allows for this arrangement. 15

18. The DMO advised the ANAO that, at the time of Contract signature on 21 December 2001, it was accepted that the ARH delivered at In Service Date (15 December 2004), and a number of subsequent ARH, would not meet the fully contracted specification. In February 2006, the DMO also advised the ANAO that negotiations commenced with the Contractor in 2002, which resulted in the DMO agreeing to a lesser capability at the In Service and acceptance dates of the first three aircraft than that specified in the December 2001 Contract16. The ANAO observed that the negotiation for a fundamental change to the Acquisition Contract to cater for the resulting remediation plan that impacted on available operational capability, was not formalised through agreed Contract Change Proposals.

19. The first three aircraft accepted by the DMO carried configuration deficiencies that did not meet contractual specifications. These included capabilities associated with: maximum all up weight; weapons operability; navigation system operability for instrument rated flight conditions; software integration; an emergency locator beacon; a compliant voice flight data recorder operable in high ‘G' environments; proven crash resistance; an ability to undertake protracted flight over water (for the first two aircraft); an operable ground management system to task and communicate with the aircraft; and the required spares and support and test equipment.

20. The DMO agreed that specific contractual capabilities were not required at the respective In Service and acceptance dates of December 2004, and June 2005. The DMO advised that deeper level maintenance and the retrofit activity to ameliorate deficiencies with ARH 1, started in February 2006, and is to be completed in November 2006.

21. The ANAO noted that, at the time the Project Director accepted ARH 5 one month ahead of schedule, the subordinate Operational Airworthiness Authority delegation had expired five months earlier, in December 2004. There was no valid Operational Airworthiness Authority delegation that allowed the DMO's Project Director to accept ARH 5. Defence advised the ANAO in February 2006 that the intention had always been to ensure that this authority was valid throughout the period for which it had lapsed, to allow the Project Authority to undertake acceptance activities.

Key findings

Contract tendering (Chapter 2)

22. In an effort to reduce the ADF's costs of ownership, the tendering process was required to deliver a capability with a high level of commonality with other Defence resources. The ANAO considers that, with the exception of some of the onboard communications capabilities, at the time of contract signature, the Tiger ARH provided limited opportunities to leverage from commonality with any of the existing systems in service with the ADF. The DMO advised the ANAO in November 2005 that developmental equipment is procured where it represents value for money, and that in this case, the argument for more commonality than provided did not provide for cost savings.

23. A Tender Evaluation Plan for the Request for Tender (RFT) incorporating the requirement to prepare an evaluation report (Source Selection Report) was approved for use by Defence in May 2001. The DMO did not develop a Source Selection Report to summarise and record the outcomes of the tender evaluation process, and to assist the Tender Evaluation Board form its recommendation in favour of a preferred tenderer, opting instead for a briefing that combined the exclusion reports 17of unsuccessful tenders. The Source Selection Report is normally required to assist the Tender Evaluation Board form its recommendation in favour of a preferred tenderer18. In the ANAO's view, the record of deliberations of the Tender Evaluation Board would have been considerably enhanced by adherence to the Tender Evaluation Plan, and the extant DMO policy guidance. Defence advised the ANAO in September 2005 that, with the approval of the then Under Secretary Defence Materiel and the Air 87 Tender Evaluation Board, the exclusion report for the non-successful tenders was an accepted alternative to a formal Source Selection Report.

24. The DMO advised the ANAO in August 2005 that, at the time, the reasons underpinning the low through-life-support cost estimates provided by the winning Contractor were attributed to the more modern design of the Tiger ARH, compared to the tender competitors. The ANAO found that prior to the Through-Life-Support Contract signature, the DMO analysed of the offers received from the RFT using three separate models, and subsequently did not expect that the Contractor would apply for a significant real increase to the costs for support of the capability. In September 2004, the Contractor sought to substantially increase the costs associated with supporting the capability, which the DMO calculated would add in the order of $625 million to the whole-of-capability costs required to support the capability over the life of the Through-Life-Support Contract19. In July 2005, the DMO rejected the claim as being unjustified, and invited the Contractor to submit a new Contract Change Proposal clarifying a number of issues. At the time of preparing this audit report, the DMO had not received a revised Through-Life-Support Contract Change Proposal from the Contractor.

Acquisition Contract (Chapter 3)

25. The reliance on certification of the French Tiger variant was critical to the Australian design acceptance program. The DMO's ability to leverage from the French program was adversely impacted, because the French program had not achieved design approval outcomes, at the rate the DMO had anticipated at the time of contract signature. Staffing levels in the DMO had been predicated on the expectation that the French certification program was to have been more advanced than realised20. The ANAO observed that DMO, and Defence staff work levels were markedly increased because of the delays associated with the French certification program.

26. The Acquisition and Through-Life-Support Contracts require the Contractor and sub-contractors to maintain Intellectual Property in a state that can be used by Defence, as required. The ANAO considers that the DMO would benefit from an Intellectual Property review, with the aim of ensuring Contractor, and sub-contractor Intellectual Property is being maintained in a state that can be used as and when required to support the capability.

Delivery performance (Chapter 4)

27. Many of the elements associated with modifying the standard aircraft design for the ADF were not contractually required by the DMO to be functional at the time the aircraft was accepted by the DMO at the In-Service Date (December 2004). However, contract underperformance associated with the delivery of modified, and standard elements of the aircraft increased the risk that there would be a delay associated with awarding an unrestricted Australian Military Type Certificate for the Tiger ARH type. The DMO accepted ARH 1, 2 and 5 with contractual shortfalls and significant capability limitations, including deficient elements of the weapons, engine and software systems.

28. The DMO accepted the first two of the four French built aircraft (ARH 1 and 2) using a draft procedure. These aircraft were accepted from the Contractor on schedule in December 2004, with known technical, operational, and managed airworthiness limitations. The ANAO was informed that, it is the DMO's practice to accept deliverables with contractual shortfalls, and operational limitations, on a risk managed basis, to progress Defence specific training, and testing activities, to deliver the required operational capability21. The DMO withheld 50 per cent of the Type Certification milestone payment associated with acceptance of the first two aircraft, until the conditions for the recommendation of an award of an Australian Military Type Certificate had been met. The DMO advised the ANAO that the withheld funds were intended to address design risks, but not production shortfalls22. The Tiger ARH system is not required to achieve initial operational capability comprising one squadron of six aircraft until June 2007.

29. The DMO accepted the first of the 18 Australian assembled aircraft on 1 June 2005, on the basis of the draft acceptance procedure. Acceptance followed a Production Acceptance Test and Evaluation Report compiled by the Defence Aircraft Research and Development Unit (ARDU) Test Team 23on 30 May 2005 that recommended the DMO should not accept the aircraft in its delivered state (see Figure 2). On completion of scheduled delivery testing in late May 2005, a series of tests relating to the airborne systems were not undertaken as part of the Production Acceptance Test and Evaluation phase. It had been agreed between the DMO and the Contractor that the tests that had not been undertaken were for systems and equipment not required to be delivered at that stage. These included systems and equipment associated with managed airworthiness issues24 and significant25 operational capability limitations. 26

30. The ANAO found that the DMO Project Authority, acting as a subordinate Operational Airworthiness Authority representative (the DMO ARH Project Director), did not liaise with the Capability Manager (who is the Army Operational Airworthiness Authority) prior to accepting ARH 5 (see Figure 2). The DMO Project Authority advised the ANAO that the risk associated with accepting ARH 5 was considered to be ‘MEDIUM' or LESS, and had the delegation not already expired in December 2004, the acceptance of ARH 5 would have fallen within the Project Authority's subordinate Operational Airworthiness delegation, issued by the Operational Airworthiness Authority. 27

31. The Defence ARDU Test Team assessment stated that, ARH 5 exhibited neither high quality nor mature system performance, and a number of issues would directly affect safe and efficient operation of the aircraft, especially in the training environment. The Design Acceptance Representative28, made the assessment that there were no safety limitations that would prevent the Project Authority from accepting ARH 5. The DMO advised that this assessment was for operations under a Special Flight Permit29. The DMO Project Office has detailed processes directed at accepting issues associated with design of the delivered products, although the processes applied to acceptance of delivered aircraft were less definitive, and were in draft form, up to and including the third aircraft, which was delivered in June 2005 (ARH 5). 30

Figure 2 ARH 5 Production Acceptance Process

Source: ANAO analysis of acceptance documentation.

32. The ANAO notes that following contractual acceptance, ARH 5 was not able to be operated for a period of three weeks because residual software certification activities had not been completed, and had not been approved for use. Defence advised the ANAO that under the Special Flight Permit extant at that time, no aircraft were used for flying training in Australia until September 2005. During the time between acceptance of ARH 5 and September 2005, 28.5 hours of flight test and evaluation was undertaken using ARH 5.

33. The DMO accepted ARH 4 in September 2005, some five months behind schedule. The DMO advised the ANAO that four of the five months constituted delays associated with holding ARH 4 in France to progress instructor training activities in the absence of French aircraft and a delayed Air Crew Training Simulator. As at October 2005, the third French built Tiger ARH had been delivered to the Contractor's facility in Brisbane, but not yet contractually accepted by the DMO, some 10 months following the original contract requirement for delivery of the aircraft, owing to structural deficiencies, and training commitments in France.

34. The main aircraft engines for the Tiger ARH are contractually deficient because they are unable to deliver the required power output at the maximum operational requirement. The Contractor is currently trialling engineering improvements that may address the power shortfall. This increase in power, however, may come at the cost of an increased rate of fuel usage, and thus a loss in capability in terms of achievable range under the maximum requirements. The DMO advised the ANAO that the Contractor is required to deliver a contractually compliant engine at no additional cost to Defence.

35. Defence advised the ANAO that the DMO and the Contractor have not resolved the issues associated with engine performance, and the DMO position is that the performance test results on the Tiger ARH demonstrate a performance deficiency.31 The DMO advise that the actual performance of the engines is not yet clear, and testing of the engines is ongoing.

36. In addition to trials associated with modifications to the existing system, the Contractor has offered a future engine upgrade to Defence, at cost, which may result in a significant improvement in power, at a lesser capability cost in fuel usage, in an attempt to address the shortfall in the delivered engine power. The current list price for an existing main engine is in the order of $2.5 million. The option to replace the existing engines may exceed $110 million. The DMO's position is that they expect a contractually compliant engine to be delivered within the existing project cost.

Through Life Support (Chapter 5)

37. The Contractor submitted a contract change proposal in September 2004 to the DMO stating that, to deliver the required services against the 15-year Through Life-Support Contract, a significant real cost increase is required. Defence advised the ANAO that the Department estimated that the proposed change represented an increased cost to Defence to maintain the ARH capability in the order of an additional 84 per cent. In July 2005, the DMO advised the Contractor that their claim was rejected, and the Contractor was asked to provide a new proposal. 32

38. The development, and delivery of training equipment and courseware has been delayed against the originally contracted delivery dates by up to 15 months33. The Contractor advised the ANAO that the aircrew training simulators may not be available for use in Australia before mid 2006. The ANAO found that a prime cause of the delay to the delivery of aircrew training device simulators34, in addition to the change in requirements, has been the efficacy of the integration of aircraft software, which is continually being modified as part of the Tiger ARH test program. This delay has added to Defence's costs35, for which Defence is entitled to make a claim under the terms of the Acquisition Contract, against the Contractor, for liquidated damages. The Project Office has advised the Contractor that there will be a claim made for liquidated damages for late delivery of the training related milestones.

39. A decision to incorporate changes to the specifications associated with the air training device simulators, following Contract signature, contributed to a subsequent delay in delivery of major elements of supporting infrastructure to the Oakey Army Aviation Centre, and the Darwin based 1st Aviation Regiment. The cost of this delay has been assessed as $10.8 million. In addition, the DMO agreed with the Contractor that the change in requirement would result in an additional five month delay to the delivery schedule, whilst the simulator equipment was redesigned.

Agency response

40. Defence agreed with all five recommendations made in this report. Defence's full response, on behalf of the DMO, is at Appendix 1 of the report. The Defence response states that:

AIR 87 has been impacted by two main factors: slippage in progress of the Franco-German Type Design Acceptance program and a delay in delivery of the full flight simulator. The DMO has been required to deal with the complexity of responding to a changing commercial and technological environment. These factors have required the DMO to amend its Acceptance strategy, undertake additional design certification workload, and implement a revised aircrew training program in order to mitigate the overall impact on delivery of the Australian capability.

Footnotes

1 The DMO was appropriated $7.1 billion in 2005-06 to deliver Defence capability and sustainment outcomes. Project Air 87 has a current approved budget of $1.96 billion, and is scheduled to have a capital expenditure of $440 million in 2005-06.

2 The Defence Capability Development Manual 2005 defines ‘off-the-shelf' as a product that will be available for purchase, and will have been delivered to another Military or Government body or Commercial enterprise in a similar form to that being purchased at the time of the approval being sought (first or second pass).

3 The DMO manages major capital acquisition projects through 46 System Program Offices around Australia, and was established as a prescribed agency within the Defence portfolio on 1 July 2005.

4 The DMO advised the ANAO that, of the 900 design requirements associated with the Tiger aircraft, there were 14 changes required for the Australian Tiger ARH.

5 Defence has since advised the ANAO that it has resolved these issues under the ADF Airworthiness System. At the time the recommendation was made in August 2005 for award of the Australian Military Type Certificate, of the 356 items comprising the ARH Certification Basis Description, 227 were established as acceptable, 54 were established as unacceptable, 68 had not been established (of which 63 related to aircraft stores clearance), and seven had been superseded. The Project Office assured the Airworthiness Board that all the Certification Basis Description Items not established, or deemed unacceptable were being managed via Airworthiness Issue Papers and or limitations.

6 Defence recognised that the existing light observation helicopters deployed in Timor at that time were inadequate for conducting reconnaissance missions and escorting the Black Hawk troop lift and utility helicopters.

7 The Acquisition Contract defines In Service Date as: That date on which sufficient equipment (possessing an airworthiness related service release, if applicable), individually trained personnel and ADF and contractor support measures are in place to enable use of the specified deliverable by the ADF for the intended purpose.

8 In September 2003, the DMO reported that, from an operational airworthiness perspective, the transition into service of the ARH will be a particular challenge for Army, in that it was not yet in service with any other nation, and therefore lacked established and validated operating documentation, doctrine, standard procedures, and training systems. The DMO also noted that completion of the technical certification activity to a satisfactory standard was a complex and high-risk issue.

9 A Special Flight Permit is issued for the purpose of developmental, production or type acceptance test and evaluation flights, proof of concept or demonstration flights, or ferry flights, prior to the issue of an Australian Military Type Certificate.

10 The Defence Airworthiness Authority awards an Australian Military Type Certificate to aircraft, on the recommendation of the Airworthiness Board. It is the certification required before Service release is authorised, and normal flight operations with appropriate limitations can commence.

11 The ADF Operational Airworthiness Regulation 3.2 states that: airworthiness management and oversight of the introduction of a new aircraft or major change assures safety of flight through rigorous examination of the aircraft's suitability to operate in the intended roles and environment.

12 The ADF is responsible for self-regulation of its aviation practices but it is implicit under International Civil Aviation Organisation regulations, and hence the Civil Aviation Act 1988, that the ADF airworthiness regulatory system should be no less effective than the civil system.

13 An application for award of the Australian Military Type Certificate was presented to the Airworthiness Authority, following Airworthiness Board recommendation on 29 August 2005, and subsequently, the Australian Military Type Certificate was awarded on 26 October 2005.

14 In June 2005, the DMO made milestone payments of $9.1 million for ARH 5, and $20.7 million in Earned Value payments. The ANAO was advised that the full milestone payments totalling $11.45 million were made for delivery of ARH 4 in September 2005.

15 The DMO did withhold 50 per cent of payments associated with the award of the Type Certification at the time delivery of ARH 1 was achieved for overall system deficiencies, but did not withhold milestone payment for the aspects associated with contractual deficiencies with the performance of the aircraft itself. The DMO advised that the design process is considered to be the area of highest risk. The Contractor is unable to claim for earned value packages associated with delivery of the aircraft that have not been completed. This included ferry tanks, and roof mounted sights. The DMO withheld 5 per cent ($2.3 million) of the Earned Value payments associated with delivery of ARH 1 and 2. The withheld amount associated with the Type Certification was paid in full on award of the Australian Military Type Certificate (with limitations) in October 2005, even though some of the design issues remain unresolved.

16 The Acquisition Contract (Attachment C, Part 1) provided for the Project Authority to determine the configuration of the ARH required to meet the In Service Date milestone. The DMO advise that all helicopters delivered in such a configuration are to be retrofitted at the Contractor's expense to meet the final configuration required by the Acquisition Contract.

17 An exclusion (or screening) report states the reasons for elimination of tenderers, and confirms that remaining tenderers meet the screening criteria. This report is prepared for consideration by the Tender Evaluation Board, and subsequent to their recommendation, to the Delegate.

18 Defence also advised the ANAO that: Project Air 87 was the lead project to considerable reform, where tender evaluation for a very complex project was done in six weeks (compared to the traditional six months, compressed three months and the finally permitted six weeks) and the negotiation in two weeks when simpler projects have taken about six months.

19 The Contractor advised the ANAO in January 2006 that the proposed cost increase to the Through-Life-Support Contract contains some scope changes, introduced by the DMO, and that since December 2001, a number of scheduled contract review meetings have been held, where the DMO acknowledged that some contract changes (with the associated cost increase) were required, and that the costs associated with providing the required Support and Test Equipment should be included in the Through-Life-Support Contract in this way. The Contractor advised the ANAO that the additional cost to the Through-Life-Support Contract value, over 15 years, amounted to an increase of $365 million, representing 70 per cent of the original value. The DMO analysis includes this $365 million, and adds the non Contractor provided support requirements arising as a result of the requested changes, to arrive at an increased cost in the order of $625 million. The DMO has advised the ANAO that there have been only minor scope changes and the rest has been rejected by the DMO as unjustified.

20 Defence reported in September 2003 that: the delay in French and German certification activity for the earlier variant of the Tiger, and the current pace of design and test activity proposed by the Contractor, is complicating the work required of the Project Office to achieve certification in time for the December 2004 In-Service Date.

21 Defence advised the ANAO that it is normal for an aircraft to be delivered prior to receiving a full Australian Military Type Certificate, and be developed and tested under a Special Flight Permit to progress the acceptance and training arrangements in place to deliver a full capability within a predetermined timeframe. These aircraft are not flown, however, unless they meet strict airworthiness standards.

22 The DMO advised the ANAO that payment of the remaining 50 per cent of this milestone was authorised for payment in October 2005, even though some of the design issues had not been finalised.

23 The Defence ARDU Test Team constitutes a qualified test pilot, and a flight test engineer.

24 Defence manages airworthiness issues via a series of Issues Papers, which identify and treat possible airworthiness risks to provide for safe operational activity. In addition to the 30 significant issues with which the aircraft was accepted, 42 less significant issues also remained outstanding. Less significant issues relate to build finish, and defects that do not directly affect aircraft safety.

25 Defence advised the ANAO in October 2005 that: the split of the issues into significant and non significant was proposed by industry in an effort to try to minimise the appearance that there were a large number of important problems. Defence did not disagree that the list of ‘significant' issues may be of more importance, but they are definitely not a list of airworthiness or safety related issues.

26 Defence advised the ANAO, in October 2005, that it is managing the shortfall in contracted capabilities that were known at the time of acceptance.

27 The DMO advised the ANAO that there is no specific DMO or Defence requirement that mandates liaison between the DMO and the Capability Manager prior to the DMO accepting goods and services from Contractors on behalf of Defence.

28 The Design Acceptance Representative is an appointed delegate of the Defence Director General of Technical Airworthiness.

29 The ARH Project Authority accepted the risk that the delivered aircraft may not have been in a state that was fit for purpose for the limited scope of operations authorised by the Special Flight Permit, and intended use by the Capability Manager at the time of delivery. The Capability Manager advised the ANAO in February 2006 that the risks associated with accepting ARH 5 were no different to those for ARH 1 and 2.

30 The ANAO was advised by ARDU that their main concern regarding the whole ARH situation is that: DMO have attempted to conduct Production Acceptance prior to the aircraft design being sufficiently mature. Ideally, the Type Design would be fully functional and specification compliant at the conclusion of Type Acceptance Testing. Production Acceptance Test and Evaluation then becomes simply confirming that each delivered aircraft is consistent with the accepted type design. If this ideal situation cannot be achieved then a staged acceptance can be justified albeit with increased resource overheads due to the need for multiple acceptance testing campaigns. At each stage, the contractually required configuration must be well defined.

31 The Acquisition Contract includes a 10.5 per cent margin on power/engine performance for the required manoeuvres (to allow for pilot error). There is currently a three per cent shortfall against that 110.5 per cent (that is, about 107 per cent). The DMO advised the ANAO that the Contractor has agreed to remediate this, in order to meet its contractual obligations and at no cost to the Commonwealth of Australia.

32 The Contractor was asked to provide a proposal that considered: clarification of the objectives of the proposal; justification of the changes in the Through-Life-Support Contract; identification of any increased staff requirements; increases in sub-contractor costs; and an explanation of how existing, approved Through-Life-Support plans might be affected. The DMO had not received the new proposal at the time of the audit.

33 The DMO accepted a contract change proposal that subsequently amended the agreed acceptance date for the aircrew training device simulators to July 2005. Defence advised the ANAO that the simulators are now not expected to be accepted before July 2006.

34 Defence accepted the training courseware in June 2005, some seven months late.

35 In addition, the delay in delivering the simulator equipment has contributed to what the ADF Airworthiness Board noted as a fragile ARH manning situation.