Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Tendering Process for the Construction of the Joint Operation Headquarters

The objective of the audit was to review Defence's management of the HQJOC Project's tender process, including probity management, for the construction of the joint operation headquarters in order to provide assurance that the policy principles for the use of private financing had been followed.

Summary

Introduction

1. The selection of a site in rural New South Wales, south of Sydney and near Canberra, for the construction of a new purpose-built operational military headquarters for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) was announced by the then Prime Minister, the Hon. John Howard MP, on 3 October 2001.1

2. The Department of Defence (Defence) is responsible for the Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) Project. The Project was established to create a new facility to enable the ADF to more effectively plan and conduct its operations, and other activities such as support for national and international disaster relief.

3. The new HQJOC facility was officially opened by the Prime Minister, the Hon. Kevin Rudd MP on 7 March 2009. The facility replaces a number of existing transitional facilities and staffing arrangements and accommodates approximately 750 members of the ADF and the Australian Public Service in a single location.2 In total, the financial modelling for the Project, completed in July 2006, determined that the whole of life Net Present Value (NPV) of the selected private sector consortium providing the buildings, infrastructure and services over the Project's 30 year term was $572.2 million (2006–07 Budget prices, outturned).3 The new facility was formally handed over by its private sector construction company to Defence in July 2008.4 Following the separate installation of the command, control, communications, computing and intelligence systems (C4I), the facility was available for full occupation and use by Defence from November 2008.5

Project delivery model: Public Private Partnership

4. In March 2004, the then Government approved Defence proceeding with the Project using a Public Private Partnership (PPP) as the Project's delivery model.6 The Government's approval for Defence's use of a PPP was conditional on the arrangements achieving superior value for money (VFM) compared to the alternative of proceeding with the Project using traditional direct procurement. The Project is the first where the Australian Government7 has used a PPP to both construct and maintain a major facility on a greenfield site.8

5. Defence commenced an open tender process for the Project in April 2004 that culminated in May 2006 with the Government announcing that a private sector company, Praeco Pty Limited (the Prime Contractor), was the preferred tenderer to design, construct, finance, operate and maintain the facility via a PPP.9 Defence signed a contract for delivery of the Project, on behalf of the Commonwealth, with the Prime Contractor on 30 June 2006—effective for 30 years, to 30 June 2036. Ownership of the facility transfers to Defence at the end of the contract's 30 year term.

Assessing value for money

6. VFM is assessed through a comparative analysis of all relevant costs and benefits over the entire life cycle of a project. When evaluating a private financing proposal, VFM is tested by comparing the outputs and costs of private financing proposals against a neutral benchmark, called the public sector comparator (referred to by Defence as the Project Cost Benchmark (PCB)). In consultation with the then Department of Finance and Administration (Finance),10 Defence and its project advisers developed and used a PCB for the HQJOC Project.11

7. The development of a PCB and the evaluation of the relative VFM of the tender responses for a PPP as compared to the PCB involve the identification of relevant costs and risks, and then the development of estimates of the Net Present Cost (NPC)12 of these costs and risks. The decision as to whether or not undertaking a proposal through a PPP, as opposed to a direct procurement process, will offer superior VFM is made taking into account the comparison between the estimated NPC of the PCB and the estimated NPC of the various PPP tender responses received. Defence engaged a range of external expert advisers, at a total cost of some $15.7 million,13 to assist it in undertaking the tasks associated with evaluating the best approach to delivering the HQJOC Project, including the development of the PCB and the calculation of the estimates of the NPC of the various tender responses received.

8. Defence advised the then Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee in June 2006 that the fact the proposed PPP financing arrangement showed a lower cost to the Government, than the PCB, was the most significant factor in the decision to proceed with a PPP for the Project rather than a direct procurement process.14

9. Defence estimated that the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB15 in April 2006, when the Government agreed to the selection of the eventual Prime Contractor as preferred tenderer, was $508.1 million. At that time, Defence estimated the NPC of the particular tender response from the Prime Contractor that Defence subsequently entered into a contract for, at $503.9 million—$4.2 million less than the risk adjusted PCB. Defence's estimate of the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB rose between April and June 2006,16 as did the NPC of the relevant tender response from the Prime Contractor.17 This resulted in the margin in favour of the Prime Contractor's relevant tender response as compared to the risk adjusted PCB decreasing to $0.94 million by 30 June 2006 when Defence signed a legally binding contract with the Prime Contractor for the 30 year PPP.

Audit approach

10. The objective of the audit was to review Defence's management of the HQJOC Project's tender process, including probity management, for the construction of the joint operation headquarters in order to provide assurance that the policy principles for the use of private financing had been followed.18

11. The audit examined the pre–construction stage of the Project, which began with a multi-round tender and ended with contract negotiations with the preferred tenderer and finalisation of the Project's contractual and financial documents.19 The core period of Project activity covered by the audit extends from April 2004–July 2006, as represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Audit scope

Note: This audit of Defence's management of the tendering process for the construction of the ADF's HQJOC facility focussed on events during the procurement process, as shown in the blue shaded box.

Source: ANAO analysis.

12. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) primarily conducted field work for the audit at the HQJOC Project Office's workplace in the Australian Capital Territory. The field work involved collecting primary documentary evidence and interviewing senior staff associated with the Project. The audit team interviewed a number of the Project's key external advisers and the tenderers for the Project. The audit team also undertook a literature review of the available international research on PPPs, which informed the audit's findings and conclusions.

Conclusion

13. In June 2006 Defence entered into a 30 year Public Private Partnership (PPP) arrangement for the design, construction, financing, operation and maintenance of a Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) facility for the Australian Defence Force (ADF).20 The contract is scheduled to end in June 2036. In total, Defence determined that the facility will cost $572.2 million (Net Present Value (NPV) in 2006–07 Budget prices outturned) to build and operate under a 30 year agreement with the private sector.21

14. The Project is the first where the Australian Government has used a PPP to both construct and maintain a major facility on a greenfield site. Defence sought the advice of other agencies—Finance, the Treasury, Australian Taxation Office and Australian Government Solicitor—as well as a number of external expert advisers that offered specialist advice to the Project on probity, legal, financial and commercial matters.

Tender process

15. The then Government determined that Defence's use of a PPP for the Project was conditional on the arrangements achieving superior value for money (VFM), assessed on the basis of cost and risk transfer, compared to the alternative of proceeding using traditional direct procurement for each separate element of the Project. Defence undertook a public tender to evaluate the benefit of using a PPP and determine the Project's Prime Contractor.

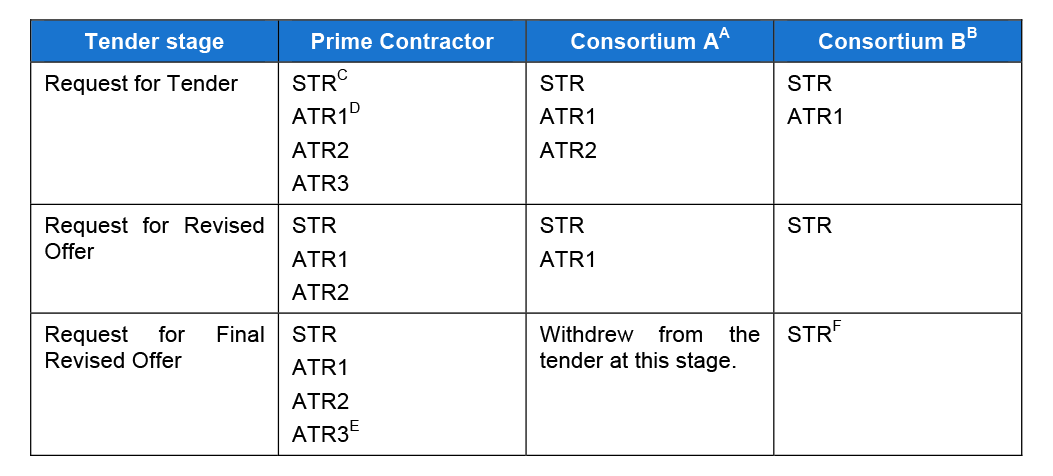

Table 1: Summary of tender rounds and consortia responses after the Request for Tender was issued

Notes:

(A) Australian Defence Capability Partnership, later renamed Australian Command Capability Partnership (Bilfinger Berger, Baulderstone Hornibrook, United KG) (referred to as Consortium A in this report).

(B) Synersec (Multiplex Group, Multiplex Infrastructure, Multiplex Constructions, Multiplex Facilities Management, Westpac Banking Corporation) (referred to as Consortium B in this report).

(C) STR: Standard Tender Response. A Standard Tender Response (STR) is defined in the Request for Tender documentation. Key features from the definition are as follows: Each tenderer must submit a STR. A failure by any tenderer to lodge a STR will automatically result in the Commonwealth rejecting all tender responses submitted by that tenderer. STRs should contain a mark-up, where the tenderer considers a mark-up appropriate, of the Part 3 documents. (Part 3 contains the Project Deed, other contractual documents and Schedule 4 of the Project's Output Specification. The preferred tenderer will be expected to enter into a contract with the Commonwealth substantially in the form of the Project Deed.) Any alternative allocation of the risks associated with key contractual provisions of the Project Deed must be presented in an Alternative Tender Response (ATR) and priced accordingly.

(D) ATR: Alternative Tender Response.

(E) All of the tender responses submitted by both remaining tenderers at the Request for Final Revised Offer (RFRO) stage were assessed as compliant with the tender documentation. The Prime Contractor's ATR3 was later set aside from further consideration by the Tender Evaluation Board on the grounds that it was not competitive against the Design and Construction evaluation criteria.

(F) Consortium B referred to two other options in its STR, but did not present the options in any detail or in the form of ATRs. The RFRO Returnable Schedules required that an ATR must be presented to a standard similar to that of a STR and address all of the information requested.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

16. To give tenderers guidance as to the Project's scope and affordability, Defence provided them with the department's current estimate of the raw PCB during each of the tender rounds following the issue of the Request for Tender (see Table 2.2). The raw PCB base cost includes all capital, operating and maintenance costs of Defence delivering the requirement. The risk adjusted PCB (which included cost estimates for the value of those risks that Defence proposed to transfer to the private sector under a private financing arrangement) was not released to the tenderers as it was used by Defence to assist with assessing the overall VFM of the tenderers' responses.

17. The tender process was lengthy and, as shown in Table 1, involved multiple rounds over a two year period because Defence assessed that none of the tenderers' responses to the Request for Tender were compliant and, after issuing a Request for Revised Offer, Defence amended the project's scope so that a fourth and final stage of the tender was required.22

18. The major effects from the extended tender process were: increased cost for tenderers to participate; a decrease in the overall number of tender responses in each later round; the withdrawal of one of the tenderers at the final round; and delays to the Project's schedule (approximately 12 months). However, in contrast with general international experience with PPPs, Defence conducted negotiations and reached commercial close (contract signature) with the Prime Contractor one month after the announcement of the Prime Contractor as preferred tenderer, which is a relatively short time for a complex project.

19. Adequate probity management processes for the Project's size and complexity informed Defence's tender process. Even though two significant probity issues arose during the live tender process in 2005—a breach of confidentiality and a breach of the Project's security arrangements—Defence adequately managed its response to both.

Government agreement to the use of a PPP and selection of a preferred tenderer

20. The Government considered the HQJOC Project in April 2006 and affirmed the use of a PPP for its delivery on the basis of Defence's advice that, based on the evaluation of the tender responses received, a PPP offered better VFM than direct procurement. Defence assessed both of the remaining tenderers (the eventual Prime Contractor and Consortium B) were capable of delivering the HQJOC facility. Three tender responses23 provided by the Prime Contractor and the sole tender response provided by Consortium B were all assessed by Defence as offering a lower estimated Net Present Cost (NPC) than the estimated whole of life costs of the direct procurement option—as encapsulated in the risk adjusted PCB.24

21. At this point, Defence had assessed the NPCs of the Prime Contractor's three competitive tender responses as between $4.1 million25 and $6.8 million26 lower than the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB. Defence estimated the NPC of Consortium B's tender response to be $26.1 million lower than the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB. However, Defence advised the Government that, overall, it assessed that the Prime Contractor was closer to accepting the Project's preferred risk allocation, whereby, Defence would transfer suitable project risks to the private sector contractor, as the party best able to manage them. Defence further advised that the price differential between the NPCs of the Prime Contractor's tender responses and Consortium B's tender response would be significantly reduced because of additional risks Defence assessed were associated with Consortium B's tender.27 Defence ranked Consortium B's tender response last having assessed that it represented the greatest risk due to proposed risk pushback, program risk and uncertainty arising from Consortium B's failure to provide marked-up Project documents28 with its Request for Final Revised Offer tender response. Defence concluded that the lack of detailed marked-up Project documents would delay contract execution and impact on the delivery schedule if Consortium B was selected as the preferred tenderer.

22. Defence recommended to the Government that the Prime Contractor be selected as the preferred tenderer on the basis of Defence's assessment that the Prime Contractor's tender responses offered the best VFM. Defence ranked the tender responses but did not nominate which of the tender responses provided by the Prime Contractor should be implemented. However, Defence advised the Government that it considered that the Prime Contractor's ATR1 offered the best VFM overall and least risk to the Commonwealth.

23. The material difference between each of the Prime Contractor's three tender responses was the tax model to be applied.29 In order to be eligible to have ATRs considered, each tenderer was required to submit a compliant STR. Defence had advised tenderers at each stage of the tender process that: ‘the Commonwealth will give favourable consideration to bids that are certain and not conditional upon the timing of or enactment of legislation or obtaining favourable tax rulings.'30 Notwithstanding this advice, the STRs submitted by both Consortium B and the Prime Contractor in the final tender round were based on the assumption that then proposed legislation to introduce a new division of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, Division 250, would apply to the project.31

24. Defence assessed both tenderers' STRs as representing the highest risk to the Commonwealth because of the uncertainty resulting from the tenderers' STRs reliance upon proposed legislation passing the Parliament in time to apply to the Project. This risk eventuated given that the legislation introducing Division 250 was not given royal assent until September 2007, some 14 months after Defence reached financial close with the Prime Contractor in July 2006.32 The Prime Contractor's STR was ranked above Consortium B's STR on the basis of Defence's assessment of the greater risk related to this tender response (see paragraph 21 and footnote 27).

25. The Government accepted Defence's recommendation that the Prime Contractor be selected as the preferred tenderer with whom Defence would conduct further negotiations. However, notwithstanding Defence's assessment of risk associated with the Prime Contractor's STR, the Government considered that negotiations should proceed with the Prime Contractor on its STR.

26. Although the Government reached this conclusion, it also directed Defence to settle the taxation model to apply to the Project with the Minister for Finance and Administration, the Treasurer and the Minister for Defence. As noted in paragraph 23, the only material difference between the Prime Contractor's three relevant tender responses was the taxation model to be applied.

Selection of a tender response

27. Following the Government's selection of the Prime Contractor as the preferred tenderer, Defence sought advice from the Prime Contractor about implementing its STR, which was the Government's preferred tender response for Defence to conduct negotiations on. The Prime Contractor advised Defence that, given the uncertain status and timing of the introduction of the proposed new tax legislation, significant time, cost and effort would have been required to structure its STR when it was unlikely that the new legislation would be available to apply to the Project. The Prime Contractor strongly preferred proceeding on the basis of its ATR2 to ensure there was certainty about the tax treatment and outcomes prior to signing a contract for the Project.

28. After seeking advice from the Project's Legal Adviser33 and officials in Finance and Treasury, and obtaining the agreement of the Project's Governance Board and its then Minister, Defence negotiated with the Prime Contractor on its ATR2. On the basis of the advice received from agencies and the Prime Contractor, Defence subsequently concluded that implementing the Prime Contractor's ATR2 would be VFM and consistent with the Government's decision of April 2006.34

29. Defence formally briefed its Minister on several occasions after the Government's April 2006 decision. The Minister for Finance and Administration was also aware of the broad details of Defence's approach to implementing the Government's decision and that officials in Defence, Treasury and Finance had formed a view as to a suitable structure for the Project's tax treatment. However, the Government's decision also required Defence to obtain the formal agreement of the Treasurer to the Project's tax treatment, which was not done. It would also have been prudent for Defence to have provided further advice to the Government about the Project's tender process after April 2006, given the decreasing margin between the Prime Contractor's tender response and the PCB leading up to contract signature (see paragraph 32).

30. The Project's Process Plan35 refers to maintaining competitive tension for the benefit of the Commonwealth during contract negotiation and finalisation. Defence decided that the overall standing of Consortium B's final tender response (its STR) was such that the continuation of negotiations with that tenderer during contract negotiation and finalisation with the preferred tenderer was not warranted. Nevertheless, Defence retained the ability to negotiate with Consortium B if discussions with the Prime Contractor were unsatisfactory.

Narrow margin between PPP and traditional procurement approach

31. The decision to proceed with the Project using a PPP was not straightforward given the narrow margin associated with Defence's quantitative assessment of VFM using the risk adjusted PCB to compare the tenderers' responses against each other and Defence's direct procurement option.

32. In April 2006, when the Government considered Defence's tender evaluation assessments, the NPC of the Prime Contractor's ATR2 (the tender response later implemented by Defence) was calculated to be $4.2 million less than the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB. When Defence announced the preferred tenderer in May 2006, following cost increases during clarifying discussions with the Prime Contractor, this margin had reduced to $1.6 million. By the time Defence concluded its negotiations with the Prime Contractor in June 2006, prior to commercial close (contract signature), the risk adjusted PCB had been revised to $515.64 million36 and the estimated NPC of the Prime Contractor's ATR2 was $514.7 million. Therefore, at the time the final decision was taken by Defence to enter into a PPP arrangement for the Project, Defence estimated that the financial benefit offered to the Commonwealth for doing so compared to using direct procurement was a potential saving in NPC terms of $0.94 million, or 0.18 per cent, over 30 years.37

Records management

33. Construction of the new HQJOC facility began in November 2006; with Defence announcing completion of construction in July 2008. After additional work to install the command, control, communications, computing and intelligence systems was also completed, the facility was available for full occupation and use by Defence from November 2008. The new facility was officially opened by the Prime Minister, the Hon. Kevin Rudd MP on 7 March 2009.38 A key determinant of the Project's long-term success will be contract management, which depends, in part, on the Project Office's continuing access to relevant records of the tender and contract negotiation processes.

34. This audit identified that Defence's records dealing with financial matters for the Project may not be sufficiently complete to adequately support future contract management of the annual service payments over the Project's 30 year term. The ANAO encountered difficulty in accessing relevant financial records for the Project. This process, including discussions of financial matters with the Project Office, was protracted. The ANAO identified instances of lack of written records for key decisions and incomplete records.

Overall conclusion

35. Overall, the ANAO considers that Defence's management of the major elements of the Project's tender process followed the policy principles for the use of private financing established in 2002 in relation to private financing initiatives. Defence pursued an open approach which informed tenderers of the estimated capital, operating and maintenance costs of delivering the Projects' requirements, but did not include cost estimates for the value of those risks that Defence proposed to transfer to the private sector under a private financing arrangement. Additionally, Defence established and followed probity management processes commensurate with the Project's size and complexity.

36. While the use of PPPs is not new in Australia, or overseas, there is continuing debate about the relative merits of the public sector using private financing initiatives to deliver services or infrastructure as an alternative to using traditional direct procurement. The ANAO found that the HQJOC Project was similar to other PPPs in terms of its long-term arrangement with the private sector and complexity, but the tender process was unique because it was the first time Defence, and the Australian Government, had used a PPP to both construct and maintain a major facility on a greenfield site. Defence was supported throughout the Project by Finance and by external advisers that assisted with Defence's assessment of the VFM, viability and risks associated with the tender responses. In the final analysis, the Project involved a costly two year tender process for Defence, and the tenderers, that resulted in a slim final margin of $0.94 million between the estimated NPC of the risk adjusted PCB and the Prime Contractor's tender response that forms the basis of the facility's 30 year contract.

Key findings

Procurement Framework (Chapter 2)

37. The PCB was an essential tool for the Project and central to Defence's assessment of tender responses, the decision to proceed with a PPP and the consequent selection of the Prime Contractor. Defence finalised the risk adjusted PCB in January 2006, for use in evaluating the tenderers' final responses, the day after the tenderers' final responses were received and opened by Defence. This carried risks for the integrity of the tender process. Critical benchmarks such as the PCB should be finalised well in advance of opening the tender responses. This final stage of development of the PCB, relative to the tender process, was not identified as an issue of concern in the probity documents reviewed by the ANAO.

38. A core principle for Australian Government procurement is transparency. Defence has made publicly available a great deal of information about the Project, including the Prime Contractor's details, the timeframe and cost of the Project. However, Defence has not fully complied with the Senate Order for Departmental and Agency Contracts, Annual Report or AusTender requirements for publicly reporting the Project's contracts.39 The ANAO found no direct correlation between the three reporting mechanisms and no consistent approach by Defence to identifying relevant contracts with the Project.

Tender Process (Chapter 3)

39. Defence took over two years, from April 2004 to June 2006, to complete the Project's tender to the contract signature stage and issued tender documents in four rounds: April 2004, Invitation to Register Interest (ITR) for the Project;40 September 2004, Request for Tender (RFT); May 2005, Request for Revised Offer; and October 2005, Request for Final Revised Offer.

40. Due to the time required, the inherent complexity of PPPs and Defence's reliance on external expert advice, the tender was conducted at considerable cost to both the private sector consortia tendering and Defence.41 The total number of tender responses received by Defence reduced after each new tender round and only two of the three original tenderers that were shortlisted after the ITR in April 2004 submitted responses to the final tender round in October 2005. The ANAO encouraged Defence to evaluate its approach to fostering innovative tender responses to RFTs for any future PPPs, which could be of benefit to Defence by reducing the need for additional tender rounds.42

41. Defence and the Prime Contractor signed the Project's 30 year contract in June 2006. Based on the planned dates set out in the Project's tender evaluation plans, the actual contract signature date was approximately a year later than originally forecast. Delays in the tender corresponded to an 11 month delay in the completion of the facility to the point where Defence could begin to fully occupy the premises in mid-November 2008.43

42. The specific governance and tender evaluation structures established for the Project, including support from external expert advisers and relevant Australian Government agencies, were sufficiently comprehensive to ensure that the Project was able to comply with the Australian Government's broader procurement framework and Defence's own procurement procedures and guidelines, as outlined in Chapter 2. Defence identified a preferred tenderer in accordance with the Project's stated evaluation criteria, including a quantitative and qualitative assessment of VFM measured against the PCB.44

Decision on Preferred Tenderer (Chapter 4)

43. The possibility of tax benefits is one of the benefits that makes PPPs attractive for private sector investors. It is important for this reason that an individual agency's proposed PPP arrangement considers the potential whole of government implications for tax revenue.45 The Government specified in its decision in April 2006 the selection of the Prime Contractor as the preferred tenderer for the Project and a requirement that relevant ministers reach agreement on the Project's tax model and settle the financial implications.46 The Government also selected the Prime Contractor's STR as the preferred tender response for Defence to implement.

44. The tenderers' proposed tax arrangements for the Project became a critical differentiator in the tender's evaluation process as both the Prime Contractor and Consortium B's STRs at the Request for Final Revised Offer stage in January 2006 relied upon a new proposed Division 250 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997.47 However, the proposed Division 250 was not enacted at the time Defence evaluated the final tender responses in February 2006 or when the Government selected the Prime Contractor's STR as the preferred tender response in April 2006.

45. Once the tender responses were received, and an approach to the evaluation of the tenderers' tax structures had been settled by the Commercial Tender Evaluation Working Group, this effectively left only the Prime Contractor with viable tender responses that could be entered into by Defence and positively presented to the Government.

46. After the Government's April 2006 decision to select the Prime Contractor as the preferred tenderer and the Prime Contractor's STR as the preferred tender, Defence did not pursue further negotiations with Consortium B due to the overall standing of its final tender response. Defence negotiated and signed a legally binding contract with the Prime Contractor in June 2006, on the basis that the Prime Contactor's ATR2 represented best VFM to the Commonwealth. Defence also considered advice from Treasury officials that implementing ATR2, following discussion with the Prime Contractor, would be consistent with the Government's April 2006 decision to select the Prime Contractor's STR as the preferred tender response. The Project's Legal Process Adviser48 did not raise any probity concerns about Defence's decision not to negotiate further with Consortium B after the Government's decision.

47. Following the Government's April 2006 decision on the HQJOC Project's preferred tenderer and preferred tender response, there was a clear requirement for Defence to settle the tax model to be used for the Project and the financial implications of that model with its own minister and the Minister for Finance and Administration and the Treasurer. Defence informed the HQJOC Project Governance Board (PGB), and its Minister of the proposed tax treatment for the Prime Contractor's ATR2.49 The Minister for Finance and Administration was aware that officials in Defence, Treasury and Finance had formed a view as to a suitable structure for the Project's tax treatment. However, the Minister for Defence did not formally settle the Project's tax treatment with the Minister for Finance and Administration and the Treasurer. The Minister for Defence settled the financial implications with the Minister for Finance and Administration as part of meeting the requirements for approval of the Project prior to contract signature.

48. Although, Defence continued to advise its Minister on the Project's progress, the ANAO considered that it would have been beneficial for the PGB to have also continued its role until Defence finalised all of the Project's contractual matters, which would have been in accordance with the PGB's responsibilities as part of the Project's tender evaluation organisation.50 A rationale for Defence's downgrading of the PGB's role was not contained in Project Office records. The PGB was established as one of the bodies responsible for oversighting the Project's latter stages. Ordinarily, it would have been expected that such oversight included monitoring Defence's implementation of the Government's April 2006 decision selecting a preferred tenderer for the Project, and subsequent negotiation and finalisation of the contract with the selected preferred tenderer. Because the PGB ceased to have an active role in the latter stages of the Project,51 it could not effectively monitor the cost increases to the Project as the negotiations proceeded or the reduction in the margin between the Prime Contractor's NPC of delivering the Project compared to the NPC of the PCB.

Negotiation and Contract Development (Chapter 5)

49. The timing of the public announcement of a preferred tenderer for the Project was a significant pressure on Defence in the period immediately after the Government's April 2006 selection of the Prime Contractor as the preferred tenderer. A delay in finalising the public announcement at that stage of the tender would have impacted on Defence's ability to achieve a satisfactory full service commencement date for the new facility and increased the preferred tenderer's bid and therefore the Project's cost.

50. As discussed in paragraph 46, Defence did not negotiate further with Consortium B due to the overall standing of that consortium's tender response relative to that of the Prime Contractor. Defence held clarifying discussions with the Prime Contractor on a range of issues during the remaining period of competitive tension before the preferred tenderer was publicly announced in May 2006. The clarifying discussions were to remain confidential and were not to be seen as constituting any legally binding rights in favour of the Prime Contractor or as an intention by Defence to enter into arrangements or contracts with the Prime Contractor.

51. Due to cost increases and scheduling requirements, the difference between the NPC of the Prime Contractor's ATR2 ($506.5 million) and the NPC of the PCB ($508.1 million) when Defence announced the preferred tenderer in May 2006 was $1.6 million, a reduction from $4.2 million, as it was in April 2006 when the Government selected the preferred tenderer.

52. Defence reached commercial close in June 2006 with the Prime Contractor, one month after the preferred tenderer announcement, which was a relatively short time for a complex project. At commercial close, after various cost increases during the negotiation stage, including rises in interest rates, there was only a ‘slim margin' of $0.94 million remaining between the lower NPC of the Prime Contractor's ATR2 and the NPC of the PCB.52 In June 2006, Defence was in the position of having no other viable tenderers to negotiate with, and no ability to set aside the process and proceed with direct procurement due to all of the parties' commitment of time and resources up to that point.

53. Defence achieved financial close with the Prime Contractor in late July 2006, one month after commercial close, and completed a small number of matters that were outstanding at financial close after July. The commercial and financial close dates were each one month later than originally planned by Defence during the RFRO stage and approximately a year later than planned at the RFT stage. However, the final stages of the tender were concluded within approximately three months after the Government's decision.

Payment Schedule (Chapter 6)

54. Defence and the Prime Contractor have estimated the total of the annual service payments required from Defence over the Project's 30 year contract term.53 The estimate is subject to annual recalculation due to the effect of indexation being applied to the payments.54 Thus, the Project's final cost is unknown until Defence makes all of the annual service payments and the contract terminates, currently scheduled for June 2036. At the Project's commercial close in June 2006, Defence estimated that the Prime Contractor could deliver the Project at a NPC of $0.94 million less than the NPC of the PCB.

55. This audit identified that Defence's records dealing with financial matters for the Project may not be sufficiently complete to adequately support management of the annual service payments over the Project's 30 year term. The success of the facility's future contract management depends on the management of those records and the availability of experienced contract managers to administer the next 28 years of payments to the Prime Contractor.55 The effectiveness of these arrangements will also influence whether or not VFM for the Project is actually realised.

56. The ANAO suggests that there would be benefit for Defence in reviewing the records generated during PPP tender processes to: ensure that all records necessary to inform the future management of the contract have been appropriately collated and stored; and identify how records management arrangements could be strengthened for future PPP tenders.

Probity Management (Chapter 7)

57. Probity is an important requirement in any government procurement process and is demonstrated by carrying out procurement in a fair, ethical and transparent manner. Defence established appropriate probity management processes for the Project's size and complexity that were consistent with the probity guidance available for Australian Government procurement.

58. Defence took reasonable steps to ensure that participants in the tender process were aware of the Project's security arrangements, confidentiality requirements and their individual responsibilities. Although, the procedures were not always strictly applied by Defence.

59. Two significant probity issues arose during the tender in late 2005 after the Request for Revised Offer closed in early June 2005 and before Defence issued the Request for Final Revised Offer in late October 2005—a breach of confidentiality and a breach of security.

60. Defence's actions in response to the breach of confidentiality were in accordance with the requirements of the HQJOC Project's Process Plan and records maintained by Defence indicate that no tenderer was disadvantaged by the breach of confidentiality that took place during the live tender for the Project. However, by failing to notify the Project's Legal Process Adviser of the security breach, Defence did not act in accordance with the Project's probity management process for that matter. Additionally, Defence's records for the security breach investigation are incomplete and do not clearly document the process followed and may not be a complete record of all of the remedial steps taken by the Project Office after the investigation ended. The available records would make it difficult for Defence to draw any lessons learned from the handling of this matter for application to similar procurement processes in the future.

61. Defence advised the ANAO, as part of the agency's response to the proposed audit report, that: ‘Lessons were learnt on the conduct of procurement evaluation activities from this incident and will be included in future PPP projects'.56

62. The ANAO noted that the Project received final probity sign-off and risk audit reports from the Project's Legal Process and Risk Management Advisers that, overall, were not critical of Defence's handling of probity issues.57 However, the Legal Process Adviser was not aware of the breach of the Project's security arrangements and the scope of the Risk Management Adviser's engagement specifically excluded a detailed audit of the Project's security arrangements because of an earlier investigation by Defence's then Inspector-General's audit team of the Project's breach of security.

63. All three of the consortia tendering for the Project, at the time the two significant probity issues arose during the live tender, later indicated to Defence that they were satisfied with Defence's response to the issues. Therefore, while Defence did not effectively address some elements of the management of the two significant probity issues that arose, no adverse consequences for the tender were recorded by Defence.

Responses to the proposed report

Department of Defence

64. The Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC) Project is the first Public Private Partnership (PPP) by the Australian Government for the construction and maintenance of a facility on a greenfield site. The project was complex, incorporating both PPP project delivery and a direct procurement for the Command, Control, Communication, Computing and Intelligence (C4I) systems. Notwithstanding the complexity of the project, it was delivered successfully on time and on budget.

65. Defence welcomes the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report on Management of the Tendering Process for the Construction of the Joint Operation Headquarters. Defence is addressing the issues raised in the report and has established a PPP Branch and the National Contract Administration and Management Directorate in order to improve the management and delivery of future PPP projects. Defence notes that the report does not make any significant adverse findings and does not contain any formal recommendations.

66. Defence's detailed comments are contained in Appendix 1.

Other responses

67. The proposed report was sent to a number of other Australian Government agencies and organisations (see paragraph 1.22). The Prime Contractor provided comments for inclusion in the final report and these are contained in Appendix 2.

Footnotes

1 Available from <http://www.defence.gov.au/id/hqjoc/news.htm> [accessed 3 November 2008].

2 The Prime Minister's opening speech is available from <http://www.pm.gov.au/media/Speech/2009/speech_0860.cfm> [accessed 10 March 2009].

3 ‘Net Present Value' (NPV) is the future cash flows, discounted for timing and risk, less the cost of investing in the project calculated in terms of today's worth. Outturned prices are estimates adjusted to incorporate the expected rate of inflation. Defence announced in 2006 that the nominal whole of life cost for the 30 year project is $1.2 billion (Goods and Services Tax (GST) exclusive, in 2006–07 Budget prices outturned).

4 Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Support, the Hon. Dr Mike Kelly MP, Media Release Headquarters Joint Operations Command Project – Completion of Construction [Internet]. Department of Defence, Canberra, 11 July 2008, available from <http://www.defence.gov.au> [accessed 11 July 2008].

5 Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Support, the Hon. Dr Mike Kelly MP, Media Release Headquarters Joint Operations Command Project – Facilities Handover [Internet]. Department of Defence, Canberra, 14 November 2008, available from <http://www.defence.gov.au> [accessed 14 November 2008]. Defence has also directly contracted with ADI Limited (trading as Thales Australia) to deliver the Project's command, control, communications, computing and intelligence systems (C4I). The value of the C4I contract will be up to $58.5 million (GST exclusive, in 2006–07 Budget prices).

6 The Australian Government defines PPPs as:

a form of government procurement involving the use of private sector capital to wholly or partly fund an asset—that would have otherwise been purchased directly by the government—which is used to deliver Australian Government outcomes.

Department of Finance and Deregulation, Australian Government Policy Principles for the Use of Public Private Partnerships - FMG 21 [Internet]. Department of Finance and Deregulation, Canberra, 2006, available from <http://www.finance.gov.au> [accessed 27 June 2008].

7 In Australia, state governments have used PPPs for roads, tunnels, hospitals, prisons and schools. Other examples of the use of PPPs from overseas include waste facilities, construction of government offices, train infrastructure, defence facilities and airports. International Federation of Accountants, Service Concessions / PPPs, IFAC, Montreal, 2007, pp. 20–21.

8 ‘Greenfield' is a term used to describe undeveloped land.

9 Praeco Pty Limited (Leighton Contractors, Leighton Services and Boeing Australia Limited, which was later replaced by ABN AMRO) is referred to as the Prime Contractor in this report.

10 Following changes to the Administrative Arrangements Order on 25 January 2008 the Department of Finance and Administration became the Department of Finance and Deregulation. The same contraction is used for both names for the department, Finance.

11 Defence's Private Financing Manual (2002) defines the PCB as an estimate of the whole of life cost of delivering a capability where Defence buys the capital equipment and facilities and then supports ongoing delivery of the service needed to provide that capability. The estimate should be based on the most cost effective method and may include the use of outsourced maintenance and service delivery.

12 ‘Net Present Cost' is the equivalent cost at a given time of a stream of future net cash outlays (calculated by discounting the values at the appropriate discount rate).

13 See Table 2.1 for a listing of Defence's external advisers on the HQJOC Project and the costs Defence advised attached to each of these contracts. Defence advised the ANAO, as part of the agency's response to the proposed audit report, that the costs reported in Table 2.1 include funds allocated during the project's construction phase, in addition to the costs associated with the tender process. Defence letter to the ANAO dated 9 April 2009.

14 Official Committee Hansard, Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee, Budget Estimates, Canberra, 1 June 2006, pp. 128–129.

15 The raw PCB represents the whole of life cost of the ‘benchmark project'. The raw PCB base cost includes all capital, operating and maintenance costs of Defence delivering the requirement, but not risk costs or contingencies often found in traditional budget estimates. The risk adjusted PCB includes in addition the estimated value of those risks that Defence proposes to transfer to the private sector under a private financing arrangement. Under direct procurement, Defence would retain these risks, therefore, their value needs to be estimated and added to the base cost.

16 The increase in the PCB was due to: an increase in the estimated electricity costs; acceleration costs for the Project to meet the preferred schedule; and additional capital expenditure items.

17 The increase in the Prime Contractor's tender response was due to: acceleration costs for the Project to meet the preferred schedule; additional capital expenditure items; and the impact of interest rate rises on the financial model.

18 The former Department of Finance and Administration issued the Commonwealth Policy Principles for the Use of Private Financing in June 2002, which were relevant to the Project at that time. There were three core principles: value for money; transparency; and accountability.

19 The HQJOC Project can be separated into distinct stages as follows:

- Project inception activities;

- a tendering process, to determine the Prime Contractor for the Project;

- construction of the HQJOC facility, by the Prime Contractor;

- installation of the C4I systems, by a separate contractor; and

- post–construction management of the Prime Contractor's delivery of operational services for the facility until the end of the contract term in June 2036.

The audit's scope excluded any consideration of the Project's inception activities and later construction and contract management stages. See Figure 1.

20 The Project was to create a new facility to allow the ADF to more effectively plan and conduct its operations and other national and international activities. The new facility replaces existing transitional arrangements and will accommodate approximately 750 members of the ADF and the Australian Public Service in a single location in rural New South Wales.

21 ‘Net Present Value' is the future cash flows, discounted for timing and risk, less the cost of investing in the project calculated in terms of today's worth. Defence announced in 2006 that the nominal whole of life cost for the 30 year project is $1.2 billion (Goods and Services Tax (GST) exclusive, in 2006–07 Budget prices outturned).

22 The four rounds in the tender from April 2004 to April 2006 (selection of a preferred tenderer) were as follows:

- Invitation to Register Interest—issued 2 April 2004 and closed 27 May 2004 (seven responses received and three tenderers were shortlisted for the next round);

- Request for Tender—issued 1 September 2004 and closed 22 February 2005 (three tenderers submitted tender responses);

- Request for Revised Offer—issued 2 May 2005 and closed 3 June 2005 (three tenderers submitted tender responses); and

- Request for Final Revised Offer—issued 24 October 2005 and closed 19 January 2006 (one tenderer subsequently withdrew; only two tenderers submitted final tender responses).

23 As can be seen in Table 1, at the Request for Final Revised Offer stage of the tender process, the Prime Contractor submitted a standard tender response and three alternative tender responses (one of which was later set aside from further consideration because it was not competitive against one of the key evaluation criteria).

24 See footnote 15 for a description of the PCB.

25 For the Prime Contractor's ATR2.

26 For the Prime Contractor's STR. The Prime Contractor's ATR1 was estimated to have a margin over the NPC of the risk adjusted PCB of $4.9 million.

27 Defence quantified risks related to the need for project acceleration at between $6.5 million and $8 million. Defence also identified costs associated with ‘risk pushback' to the Commonwealth identified in Consortium B's notations on the Project documentation but concluded that it was not possible to fully quantify such risks in the absence of detailed mark-ups from Consortium B to the Project documentation. See paragraph 3.64.

28 The key project document was the proposed Project Deed which Defence attached to the RFT and advised tenderers that they would be: ‘expected to enter into a contract with the Commonwealth substantially in the form of the Project Deed.' The Prime Contractor provided Defence with marked-up versions of the Project documents which allowed Defence to clearly identify the tenderer's proposed changes and evaluate any possible cost or risk associated with them. By contrast, Consortium B made some notations on the Project documents that Defence assessed as indicating proposed changes that would involve risk pushback to the Commonwealth but, because marked-up copies of the Project documents were not provided by Consortium B, Defence could not quantify the costs attached to the changes Consortium B were seeking. It was not a requirement for tenderers to provide copies of the Project documentation with the specific changes the tenderer would be seeking marked-up on them.

29 The preferred tenderer's Standard Tender Response (STR) was based on the then proposed Division 250 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, its ATR1 was a securitised lease structure and its ATR2 was based on Division 16D of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936, Certain arrangements relating to the use of property.

30 Returnable Schedule E3, Subcriterion ‘Taxation arrangements', Request for Final Revised Offers (RFRO) AZ 3206 (6 December 2005), p. 78.

31 Proposed Division 250, of the Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA) 1997, was to institute arrangements for taxing the proceeds of leases or other arrangements for the use of assets by tax preferred entities, such as the Commonwealth. The Tax Laws Amendment (2007 Measures No. 5) Act 2007 received Royal Assent on 25 September 2007 and Division 250—Assets put to tax preferred use, was incorporated in the ITAA 1997 and applies to projects after 1 July 2007. Accordingly, the application of Division 250 to projects was not available in April 2006 when Defence sought the Government's agreement to the selection of a preferred tenderer or indeed by the time Defence reached financial close with the Prime Contractor in July 2006.

32 Under a PPP, the private sector partner's financiers wait until after the commercial close before settling the financial aspects of the transaction. The latter activity is called the financial close.

33 Blake Dawson Waldron (now Blake Dawson) were advisers to the HQJOC Project and are referred to in this report as the Legal Adviser.

34 Defence did not provide further advice to the Government after its April 2006 selection of a preferred tenderer and a preferred tender response (the Prime Contractor's STR).

35 Australian Government Solicitor, Headquarters Joint Operations Command Project Process Plan, 2004, p. 2.

36 An increase of $19.44 million over the estimation of NPC of the risk adjusted PCB of $496.2 million, which was provided to the Government in April 2006.

37 At financial close in July 2006, the private sector partner's financiers completed the financial aspects of the transaction, and the Project's NPV was determined to be $572.2 million (2006–07 Budget prices outturned). Defence advised the ANAO that the 11 per cent increase in dollar terms between the NPC of $514.7 million at commercial close, when a legally binding contract was signed, and the NPV at financial close was due to the inclusion in the latter of taxation, insurance and the effect of interest rate changes after the commercial close.

38The Prime Minister's opening speech is available from <http://www.pm.gov.au/media/Speech/2009/speech_0860.cfm> [accessed 10 March 2009].

39 The Senate Order for Departmental and Agency Contracts supports the principles of accountability and transparency in procurement by requiring agencies subject to the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA 1997) to list certain details within a specified period of time for contracts of $100 000 or more on the Internet. Defence, as an FMA agency, is required to publish details of all of its consultancies valued at over $10 000 in its Annual Report. Furthermore, Defence is required by the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines to publish on AusTender contracts and standing offers with a value of $10 000 or more.

40 International experience is that the complexity and long timeframes associated with PPP projects mean tendering is expensive and can limit the extent of competition. However, Defence received seven responses to the HQJOC ITR when it was issued in April 2004. Antony Barton, PFI deals put bidders off, Supply Management, Volume 12, No.15, 2007, p. 10.

41 Defence's ten advisers for the Project received a total of some $15.7 million in payments (see Table 2.1 for details). One of the tenderers advised Defence that it had incurred bid costs in excess of $4 million leading up to the RFRO stage and expected the final tender stage to add another $1 million to the cost of tendering for the Project.

42 Defence was seeking innovative solutions from tenderers to the RFT that would offer better VFM than a prescriptive approach to the Project's Output Specification.

43 After the building construction was completed and announced by Defence on 11 July 2008, an additional four months was required to install the C4I before Defence could relocate the intended HQJOC staff to the facility. Defence announced the completion of the C4I installation on 14 November 2008.

44 The ANAO did not evaluate the tender responses, but instead analysed key reports from the Tender Evaluation Working Groups and the Source Selection Reports produced by the Tender Evaluation Board.

45 If the private sector is able to maximise the taxation benefits from a PPP, this could result in the Commonwealth foregoing expected taxation revenue, thus reducing the PPP's VFM on a whole of government basis.

46 The Ministers for Defence, Finance and Administration and the Treasurer.

48 The proposed reform was to replace older legislation in the ITAA 1936 with a new Division 250 in the ITAA 1997 in order to improve the tax framework for PPP asset financing arrangements. See footnote 31 for additional detail.

49 Australian Government Solicitor (referred to as the Legal Process Adviser in this report).

50 Defence established a formal tender evaluation organisation for the Project, commensurate with the Project's complexity, and specified a hierarchy that included evaluation, governance, and decision-making bodies for the Project, which included a Project Governance Board (PGB). Defence advised the PGB in late May 2006 of the outcome of discussions about the Project's tax treatment and Defence's conclusion that the Prime Contractor's ATR2 was considered VFM.

51 The PGB, as part of the Project's tender evaluation organisation was responsible for the following:

- Oversight of the tender evaluation process.

- Monitoring of the health of the Project to ensure outcomes met Commonwealth and Defence requirements.

- Ensuring the Project's compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines and the Defence Procurement Policy Manual.

- Providing guidance as required to the Tender Evaluation Board on the conduct of the evaluation and the preparation of evaluation reports.

Department of Defence, HQJOC Project Tender Evaluation Plan v3–0, 19 January 2006, p. 10.

51 The PGB held its final face-to-face meeting in February 2006. Project Office records show that PGB members were contacted again by the Project Office via email in May 2006 and consulted about the Project's tax treatment issue. The Board's Chair and one member's acknowledgement emails, with no substantive comment included, are on Project Office files.

52 The NPC of the PCB for the Commonwealth to directly procure the construction and operation of the HQJOC Project was $515.64 million, compared with the cost of entering into a PPP with the Prime Contractor to deliver the Project at an NPC of $514.7 million.

53 In nominal terms (price of the day), the Project's $572.2 million NPV is approximately $1200 million (exclusive of GST). The NPV figure does not include the cost of the separate command, control, communications, computing and intelligence (C4I) systems contract. (The value of the C4I contract was estimated by Defence to be up to $58.5 million (in 2006–07 Budget prices)).

54 The annual service payment is indexed on 1 July each year during the term of the agreement according to a formula in the Project Deed. The annual service payment is comprised of two components: capital (non-indexed annual service payment); and operating (includes an indexed annual service payment and a non-indexed annual utilities payment). The capital amount covers the construction capital, finance and taxation costs, while the operating component represents whole of life payments for insurance and operation costs for items such as maintenance and security. The operating component of the payment is further annually adjusted for inflation based on Consumer Price Index figures provided to Defence by Finance.

55 After the HQJOC Project's contract was signed in 2006, Defence made no payments during the following two year construction period. The first annual service payment is a part year payment in 2008–09, which takes into account that only a small number of the Prime Contractor's staff would be required to support the C4I process from July to November 2008. The first full year payment starts in 2009–10.

56 Defence letter to the ANAO dated 9 April 2009.

57 Capital Insight Pty Ltd (referred to as the Risk Management Adviser in this report).