Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Tender Process for the Detention Services Contract

The objective of this audit was to assess DIMIA's management of the tender, evaluation and contract negotiation processes for the Detention Services Contract. Specifically, the audit considered DIMIA's processes for determining value for money based on the department's: evaluation of the request for tender, including the announcement of the preferred tenderer; negotiations with the successful and unsuccessful tenderers; and management of liability, indemnity and insurance.

Summary

Foreword

1. On 27 February 1998, DIMIA (Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs) 1 entered into a ten year general agreement with Australasian Correctional Services (ACS, now the GEO group) for the provision of detention services at all mainland immigration detention facilities2. This agreement, which remains extant, established a broad framework for the provision of detention services by means of contract. Under the umbrella of the general agreement, DIMIA and ACS entered into individual detention services contracts, which contained the details of specific detention services to be provided. The services contracts were managed by ACS through its operational company Australasian Correctional Management (ACM).

2. The general agreement contains provisions governing the exercise of options under the individual services contracts. In January 2001, under these terms, ACS submitted an offer for the provision of detention services for the term of the first extension of the services contract. After considering the offer and conducting negotiations with ACS, DIMIA decided not to accept the offer and to conduct a competitive tender process on amended terms and conditions. This decision was based on a determination that it was not possible for DIMIA to be satisfied that the ACS offer represented ‘best value for money'.

3. The ANAO notes that other provisions in the general agreement meant that it was necessary to seek ACS' consent to the conduct of a tender process on amended terms and conditions. The (then) Secretary wrote to ACS on 5 April 2001 to advise of this decision, and ACS agreed to the approach proposed by DIMIA on 6 June 2001.

4. In summary, there was an obligation on DIMIA to engage ACS to provide the Commonwealth's detention services, where ACS would provide ‘the best value for money'. The general agreement also provided that DIMIA was able to engage an alternative service provider where that service provider would present better value for money to DIMIA. Testing the market through a competitive tender process was seen by DIMIA as the best way to determine value for money.

5. Value for money is also central to Australian Government procurement. The Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) govern the management of Commonwealth money or property. Under the FMA Regulations an official performing duties in relation to the procurement of property or services must have regard to the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs). The CPGs (in force at the time of this procurement) provided specific guidance concerning value for money:

Value for money is the core principle underpinning Australian Government procurement. This core principle is underpinned by four supporting principles of: efficiency and effectiveness; accountability and transparency; ethics and industry development. Officials buying goods and services need to be satisfied that the best possible outcome has been achieved taking into account all relevant costs and benefits over the whole of the procurement cycle.

6. DIMIA and ACM negotiated extensions to the existing arrangements while DIMIA prepared the tender documents. In August 2001, the formal tender and evaluation processes began. Following an evaluation of a call for Expressions of Interest (EOI), four organisations were invited to submit tenders:

-

Australasian Correctional Management (ACM);

-

Group 4 Falck Global Solutions Ltd (now known as GSL);

-

Management and Training Corporation (MTC); and

-

Australian Protective Services (APS). 3

7. Global Solutions Limited (GSL) was announced as the preferred tenderer in December 2002. Contract negotiations took place with the preferred tenderer from December 2002 until the contract was signed on 27 August 2003. ACM continued to manage the detention centres throughout this period until the transition, which began in December 2003, and was completed on 29 February 2004. DIMIA's tender for the detention services contract represented an overall procurement of $400 million over the planned four years of the contract.

Audit objective

8. The objective of this audit was to assess DIMIA's management of the tender, evaluation and contract negotiation processes for the Detention Services Contract. Specifically, the audit considered DIMIA's processes for determining value for money based on the department's:

- evaluation of the request for tender, including the announcement of the preferred tenderer;

- negotiations with the successful and unsuccessful tenderers; and

- management of liability, indemnity and insurance.

Key Findings - The Procurement Process (Chapter 2)

Tender objectives

9. Determining value for money was particularly important for this procurement. The pre-existing general agreement with ACS and the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs) required DIMIA to ensure that the decision to award the detention services contract was based on value for money.

10. At the time the tender was conducted, DIMIA had received advice from Senior Counsel that the tender process needed to be conducted strictly in accordance with clause 3.3(a) of the general agreement – where the Commonwealth will elect to use ACS for any detention service contract, where ACS will provide the best value for money for the Commonwealth.

11. The ANAO found that DIMIA's processes and documentation of the tender evaluation did not clearly identify whether the provisions of the general agreement were considered in the management of the tender process, and how the agreement was to be taken into account during the tender, evaluation and contract negotiation stages from December 2001 to August 2003.

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 3)

Evaluation framework

12. In preparing for the tender process, DIMIA established a sound evaluation framework that was capable of taking into account the costs and benefits of individual tender proposals over the whole of the procurement cycle.

Probity guidelines and principles.

13. Procurement guidance issued by the Department of Finance and Administration emphasise the importance of:

- utilising necessary expertise during the conduct of the procurement process;

- clearly specifying roles and responsibilities of key personnel and ensuring the separation of duties and responsibilities;

- having a clear understanding and agreement on the level of assurance being provided by expert advisors;

- identifying and managing actual or perceived conflicts of interests; and

- creating and maintaining appropriate documentation, particularly surrounding key decisions.

Against these guidelines, the ANAO found the following.

Utilising necessary expertise during the conduct of the tender process

14. The management of a tender process requires an appropriate blend of operational, corporate and procurement experience. At the beginning of the formal process in August 2001, DIMIA's (then) Secretary approved a decision-making framework that comprised:

- an evaluation panel, that was to evaluate tenders and report to a steering committee;

- a steering committee that would be chaired by a deputy secretary and include three first assistant secretaries; (the steering committee was to select the members of the evaluation panel, and consider and guide the report of the evaluation panel); and

- the Secretary, who was to be the final decision maker (referred to as the delegate, and representing the approving authority for the procurement).

15. Given the size and importance of the tender, DIMIA engaged external specialists in law, finance, and probity to provide advice and complement the skills of DIMIA staff. Approximately half way through the evaluation process, a probity auditor was also engaged.

16. In the process of selecting the evaluation panel, the steering committee made changes to the overall, decision-making framework. There are multiple versions of steering committee meeting minutes, from which it is now not possible to determine what was discussed and agreed in relation to the roles and responsibilities of the evaluation teams. However, subsequent evidence indicates that the steering committee assumed the role originally intended for the evaluation panel and later became known as the Tender Evaluation Team (TET) as well as the steering committee. An additional team, the Tender Support Team (TST) was also created. The TST was drawn from senior DIMIA staff from the detention and compliance divisions, and included the Chief Financial Officer (CFO).

17. The ANAO found that DIMIA's records of relevant meetings did not disclose any consideration of how these changes would impact the separation of responsibilities between the steering and evaluation bodies and whether or not the Secretary, who had originally approved the framework, concurred with these changes.

18. The ANAO found that the subsequent loss of key personnel from the steering committee/TET and the tender support team at the mid-point of the tender evaluation did not trigger a review of skills and capacity necessary to complete the task. The departure of the initial chair of the steering committee effectively abolished one of the senior positions. The three remaining personnel did not assess and report to the delegate on the balance of expertise remaining. There was also no evidence of discussion, and no advice to the delegate, of the decision taken by the steering committee to replace DIMIA's CFO on the tender support team with another officer at a lower level. The replacement was drawn from the detention division and not from the CFO's division which further altered the balance of skills and experience involved in the procurement. Clearly specified roles and responsibilities of key personnel and ensuring separation of duties.

19. The Department of Finance and Administration suggests that ‘in large or complex transactions an external probity specialist may be involved to provide independent oversight of the process.'4 Generally, the appointment of a probity advisor to a major tender undertaking represents a means of independently monitoring a tender process to ensure it is conducted in accordance with identified probity principles. A probity advisor typically provides advice as requested before and during the course of the process, including on specific issues that arise. While a probity advisor has a level of direct interest in the project, it is essential that they remain independent of the project team and other advisors5. An advantage in engaging a probity advisor is that at least one individual will be completely focussed on the probity of the process and separated from other responsibilities.

20. In this tender, DIMIA engaged the probity advisor to take on additional responsibilities, including preparation of the tender evaluation plan, and providing the evaluation method and assisting in the evaluation process. Consequently, the probity advisor became involved in other aspects of the tender process, including providing advice on the modification of tender evaluation scores, in response to requests from the steering committee which are not documented.

21. It is important to ensure that the awarding of a contract is not subject to perceptions that appropriate processes may not have been followed. The ANAO found that by engaging the probity advisor to undertake additional responsibilities, DIMIA compromised the independence of this role.

Having a clear understanding and agreement of the level of assurance being provided by expert advisors

22. A probity auditor was formally appointed on 28 October 2002, approximately the mid point of the tender evaluation period. The initial requirement for the probity auditor is not documented. DIMIA's contract with the probity auditor sets out the scope of services to be provided as being a ‘desktop review' and provides only a selection of documents to be examined.

23. In his reports, the probity auditor appropriately qualified the level of assurance being provided. In describing the audit procedures, the probity audit report(s) noted;

We have conducted this stage of the Audit in accordance with our retainer, subject to the restriction on our retainer to conduct our audit at a strategic level, based on:

(a) our discussions with the project director;

(b) a selective desktop review of files…

24. The ANAO found that the terms of the engagement did not allow the probity auditor to independently determine the nature, timing and extent of audit procedures. As a result, these reports provided a low level of assurance over the probity of the process.

25. The ANAO found that although DIMIA engaged a number of contractors for independent advice, they did not require these contractors, as part of the terms of their engagement, to provide assurance over their advice. Ultimately, the probity auditor recommended that assurance from the contractors be provided. The ANAO was advised that verbal assurance was provided by DIMIA's advisors at a steering committee meeting on 22 August 2003. However, formal documented assurance was not arranged until the week prior to contract signature and this could not be finalised until the day the contract was signed.

Identifying and managing actual or perceived conflicts of interest

26. In significant procurements, members of an evaluation committee should disclose and manage appropriately any actual, perceived or potential conflicts of interest. At its meeting on 20 August 2002, the steering committee decided that there would be benefit in obtaining a formal referee report from within DIMIA, concerning the performance of ACM.

27. Probity advice was sought and the probity advisor advised against the chair of the steering committee providing the referee's report. This advice was based on the risk of a perceived conflict between the obligation of the chair of the steering committee, to consider the evaluation of each tenderer impartially, and the chair's role as the contract administrator over the previous two years, in which extensive dealings with the incumbent service provider took place.

28. Notwithstanding this advice, the steering committee agreed that the chair of the steering committee was the most appropriate person to provide the reference for ACM, from DIMIA.

29. In his report, in March 2003, the probity auditor had access to the advice of the probity advisor (discussed at paragraph 27 above), that the chair of the steering committee should not provide a referee report for ACM. Noting that this reference had, however, been subsequently provided, the probity auditor recommended that: ‘in future tenders, DIMIA should consider (prior to the issue of an RFT) a suitable separation of people who might be performing functions that have inherent tensions, real or perceived.' This recommendation, which was directed towards avoiding the potential for conflicts of interest, was not accepted by the steering committee.

30. There is no record of the delegate being informed of the probity auditor's recommendation, nor of the resolution of the steering committee to disagree with it.

Creating and maintaining appropriate documentation

31. A fundamental requirement of public administration and accountability is adequate record keeping. Records maintained need not be lengthy. The key test is that they are fit for their purpose, and appropriately managed and stored.

32. The ANAO found examples of different versions of minutes of meetings without any markings to show which was intended to be the final version. In some cases this was simply poor administration. In other cases there were potential probity implications. There are, for instance, two versions of the steering committee minutes of 17 September 2002 where the names of the tenderers are identified in one version but not in the other. Amending the minutes of the meeting to mask the identity of the tenderers indicates that the steering committee (also the tender evaluation team) considered it inappropriate for the record to show that the identity of the tenderers had been revealed at this early stage. The probity audit reports indicate that the probity auditor did not see the version of the minutes in which the tenderers were named.

33. The audit also found that there are no records of steering committee meetings held between 15 May and 21 August 2003. A range of significant matters were managed through this period, including a change in GSL's health services sub-contractor. Given this was directly related to the evaluation of the tender bids, it is reasonable to expect that the steering committee would have met to discuss the options and any impact on its assessment of value for money. However, any meetings held, and the bases for decisions taken during this period, were not recorded.

34. Overall, the ANAO considers that the standard of records created and maintained for the tender process for the detention services contract was inadequate. The records kept are not fit-for-purpose. At various stages in the conduct of this audit, DIMIA experienced difficulty in locating sufficient evidence to assist the ANAO to form an opinion about aspects of the procurement. In responding to key findings of this audit, DIMIA officials made a number of assertions to the ANAO which are inconsistent with the documentary evidence that is available. In the absence of clear reconciliations between the two positions, the actual position is unclear and calls into question the reliability of DIMIA's documentation supporting the evaluation process.

Evaluation of the Tender Bids (Chapter 4)

35. DIMIA's evaluation methodology involved separate assessments of service delivery (referred to by DIMIA as ‘technical') and financial (or price) aspects of the tender submissions. The technical and financial evaluations were then combined by dividing the results of one into the other, in order to arrive at a determination of value for money, in the form of an index. DIMIA prepared value for money indices over a range of scenarios to assess the impact of pricing on different detainee population levels accommodated in combinations of some or all of the (then) operational centres; Villawood, Maribyrnong, Perth, Baxter, Woomera and Christmas Island. One of the scenarios (E) was selected by DIMIA for use as the benchmark scenario to calculate the overall value for money index.

36. The first draft of DIMIA's value for money analysis was completed on 29 October 2002. The technical evaluation showed ACM ahead of the two other tenderers, GSL and MTC, by a clear margin. However, GSL offered a significantly lower price (for scenario E). When DIMIA combined its technical and price evaluations, GSL offered the best value for money, ahead of ACM which was 4.42 per cent behind. The third ranked tenderer, MTC, although comparable to GSL in technical score, was significantly more expensive and in value for money terms, was 22.99 per cent behind GSL.

37. A residual risk analysis conducted by DIMIA's probity advisor identified that GSL was significantly cheaper than the other two tenderers in remote locations. DIMIA's financial advisor had earlier identified this, and recommended that all tenderers be invited to clarify their pricing for remote locations. The ANAO found that this recommendation was not pursued by the steering committee and its reasoning is not documented.

38. Nevertheless, questions from members of the evaluation team apparently triggered a request from GSL, who wrote to DIMIA on 13 November 2002, stating that it had discovered a significant error in its tender spreadsheets and submitted a request to amend its pricing for remote locations. The ANAO found that DIMIA's documentation around the handling of this request was poor, and included three versions of the minutes of a meeting between the steering committee and DIMIA's probity advisor. One version of the meeting record reveals that the risk of GSL's low staff to detainee ratio at the Baxter Immigration Detention Facility, identified by the financial and probity advisors, would be ameliorated if a pricing change was accepted. The matter had not, at that stage, been considered by the steering committee and subsequent versions of this meeting record do not identify this risk.

39. The steering committee met to consider GSL's request for a pricing change on 26 November 2002, and formally agreed to accept the pricing change on the basis of it being the correction of a genuine error. The ANAO found that this pricing change added $11.57 million (NPV) to the price of GSL's tender. The steering committee also determined at this meeting that there was a narrow margin in favour of GSL representing better value for money overall, and that consideration of the residual risk factors did not change this value for money margin. The ANAO was not able to determine from the record of this meeting the steering committee's consideration of the precise effect on value for money arising from the decision to accept the pricing change from GSL.

40. The final report of the evaluation was forwarded to the delegate on 29 November 2002, recommending he approve GSL as the preferred tenderer on the basis of value for money.

41. During a subsequent meeting with the steering committee, the delegate asked a number of questions, and the report was re-submitted with answers to his questions on 18 December 2002. The ANAO found that the value for money calculation provided in the final report to the delegate was incorrect. Figures from the pre and post GSL pricing correction were transposed (by DIMIA staff, not the financial advisor) and the delegate was advised that the difference between GSL and ACM was 4.42 per cent on the value for money assessment.

42. The ANAO found that the actual difference, following DIMIA's decision to accept the 13 November 2002 pricing change from GSL, was 0.56 per cent. Although the corrections do not alter the overall position of the tenderers, the margin between them, and the top two in particular, was closer than the delegate was advised. This error remained undetected by DIMIA through the contract negotiation phase of this procurement. The delegate was ultimately informed of this error in February 2005, after the ANAO brought it to the attention of DIMIA officials in November 2004.

43. The ANAO found that the final report to the delegate was deficient in a number of other key areas:

- the delegate was not advised of the discretion open to him under the terms and conditions of the RFT to enter negotiations with more than one tenderer, including its provision to request a ‘best and final offer' from all or some of the tenderers;

- the delegate was not advised that the requirement under the CPGs to assess the Industry Development Criteria had not been assessed as part of the evaluation methodology, although the tenderers were required to comply with this requirement;

- while the delegate was advised that the assessment of the technical worth scores was based on a number of factors, including discussions with nominated referees, he was not advised that:

- ACM did not nominate DIMIA as a referee;

- the probity advisor had recommended that the chair of the steering committee should not provide a reference for ACM (because of the potential for a conflict of interest);

- the steering committee decided to nominate DIMIA as a referee and the Chair of the steering committee provided the reference.

44. The delegate was advised in the final evaluation report on 18 December 2002 that the probity auditor had not raised any issues of significance. While this was true at that point in time, the engagement of the probity auditor at the mid-point of the evaluation meant that the probity auditor had not covered all stages of the procurement. For example, three months after the final report was provided to the delegate, the probity auditor examined the potential for a conflict of interest from the chair of the steering committee and commented adversely upon it.

45. Overall, the ANAO found that the error in the value for money calculation, and other omissions from the final report of the tender evaluation meant that not all relevant information about the tender was placed before the delegate at the time he was asked to make the final decision concerning the selection of a preferred tenderer. GSL was announced as the preferred tenderer on 22 December 2002.

Negotiation with the Successful and Unsuccessful Tenderers (Chapter 5)

46. The assessment of value for money was important in this procurement because of the terms of the pre-existing general agreement as well as the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines. In order to be in the best position to determine value for money, DIMIA's evaluation process needed to be conducted rigorously, so that at the time a tenderer was eliminated, it could be clearly demonstrated why that tenderer was eliminated and, equally, it could also be demonstrated why any remaining tenderer was still under consideration.

47. Prior to the announcement of GSL as preferred tenderer in December 2002, the delegate had decided that in view of the closeness of the two tenderers GSL and ACM, ACM should be invited to keep its tender bid open until completion of contract negotiations.

48. Under these circumstances, the steering committee retained a responsibility to closely monitor and manage the margin between the two final tenderers as contract negotiations went forward, to ensure that value for money was obtained. DIMIA's process for determining value for money was set out in the tender evaluation plan. It included mechanisms for managing capability, price, residual risks and provisions for parallel negotiations and a ‘best and final offer'.

49. By February 2003, GSL had requested a number of changes to the draft contract. The requested changes involved, among other things, increases to workers compensation insurance costs, GSL's overhead costs, and the re-amortisation of start-up costs, which impacted the pricing of GSL's bid. The steering committee sought advice from its legal, financial and probity advisors, which were collated and summarised by the probity advisor on 17 February 2003. After entering GSL's proposed price increases into DIMIA's evaluation methodology, this advice highlighted changes in value for money in favour of ACM in the order of 6 or 8 per cent across all scenarios and included a recommendation from the probity advisor that the most effective course of action would be to enter into parallel negotiations. DIMIA and the probity advisor subsequently advised the ANAO that the intent of this advice was to set out a step-by-step process to manage pricing adjustments accepted during contract negotiations to assist in identifying the option of whether or not to proceed to parallel negotiations. DIMIA's management of the pricing adjustments and its monitoring of value for money throughout contract negotiations are examined below.

Monitoring value for money

50. The CPG's require that ‘officials need to be satisfied that the best possible outcome has been achieved, taking into account all relevant costs and benefits over the whole of the procurement cycle'. In this context, there are risks in accepting a preferred tenderer too early. Chief among these risks is that non-preferred tenderers cease to have any involvement in the process, but negotiations with the preferred tenderer that are required to finalise the contract may raise issues of significance.

51. Significant issues arising during contract negotiations with a preferred tenderer can involve changes in the level or scope of services the Commonwealth requires, and in the prices offered by the preferred tenderer. It is important to appreciate the probity implications of accepting changes that vary the requirements tenderers were originally asked to tender against. Probity and legal implications can arise if the original RFT requirements or the method of evaluation are amended to such an extent that a re-bidding process becomes necessary.

52. The value for money margin between ACM and GSL as reported to the delegate in the December 2002 evaluation report was small given the size of the tender. To demonstrate value for money, a level of transparency was required in DIMIA's negotiations with GSL where price and scope changes were being considered. In particular, any scope or pricing changes needed to be accurately recorded.

Workers compensation insurance changes – value for money

53. On 28 February 2003, the probity advisor prepared an updated value for money calculation, showing the impact of GSL's requested workers compensation insurance increases on its bid. The probity advisor, and one member of the steering committee have advised the ANAO that this spreadsheet indicates that value for money was being monitored. However, there is no formal record of the steering committee's consideration of this document. Notwithstanding, the spreadsheet clearly shows ACM representing better value for money than GSL following the acceptance of this pricing change.

54. DIMIA's calculations in February 2003, revealed that relatively small changes in workers compensation insurance payments, valued at $2.093 million (NPV), had placed ACM ahead of GSL in value for money terms. However, in August 2003, in the attachment to the Minute seeking approval to enter into the contract, the delegate was advised these changes were ‘due to a scope change and a similar adjustment would be required for all tenders' and as a result, these changes ‘did not have any implications for the value for money assessment'. There is no record of the steering committee's decision to classify workers compensation insurance payments as a ‘change in scope'. The ANAO considers that the changes to the workers compensation tendered amounts from GSL did not involve the Commonwealth adding or subtracting services to the tender and, therefore, considers that its classification as a change in scope of the tender was doubtful. The assertion that a similar adjustment would be required for all tenders was also not subject to further analysis or testing by DIMIA.

The closure of Woomera and Christmas Island

55. Following the announcement of the preferred tenderer, it was decided that the Woomera detention centre would be ‘mothballed'.6 As a result, GSL requested a change to the pricing of its tender to reflect that overhead costs that had been applied to Woomera would now be required to be recovered through other detention centre fees.

56. Analysis by DIMIA's financial advisor had shown that GSL's initial pricing allocated a disproportionately high amount of overhead (fixed) costs to Woomera. Subtracting these costs from the Woomera (and later Christmas Island) centres, meant that significant adjustments were then required to GSL's tendered prices for the remaining centres. Increases to GSL's fixed costs at the operational centres were greater than the amounts subtracted from the mothballed centres.

57. The closure of Woomera and Christmas Island also meant that DIMIA's benchmark scenario (E) developed for the evaluation needed to be modified to take into account the reallocation of overhead costs and the redistribution of anticipated detainee numbers to the other centres. These changes to scenario E were a departure from the stated evaluation criteria used to select the preferred tenderer. There is no evidence DIMIA considered GSL's request against the probity and legal implications of a change to the evaluation criteria and original RFT requirements. DIMIA was unable to provide a document that showed the basis on which the detainee numbers were re-distributed from Woomera and Christmas Island to the other centres, following GSL's request.

58. In considering GSL's request, DIMIA decided that the closure of Woomera (and later Christmas Island) was an ‘unforeseeable' modification to the scope of services being offered for tender. DIMIA also decided that this change would affect all tenderers equally and would not change the value for money assessment, although no comparison with other tender bids was undertaken to support this decision. As a result, the price change was accepted and advice from DIMIA's financial advisor showed that GSL's bid increased by $15.5 million (NPV) over the planned four years of the contract.

59. The ANAO notes that ACM had earlier 7submitted a request to change the way in which its corporate costs would be recovered from the fees it would receive in operating the detention centres8. The steering committee rejected ACM's request, although there was no change in the overall cost of ACM's bid. This request 9made it clear that ACM had allocated no corporate costs to the Port Hedland, Woomera or Christmas Island centres and, therefore, it was unlikely that the closure of Woomera and Christmas Island would have affected all tenderers equally. The ANAO considers that GSL's request to re-distribute its overhead costs from Woomera (and later for the same reasons Christmas Island) to the other centres should have been brought to account in DIMIA's value for money calculation.

60. The minute to DIMIA's Secretary in August 2003 recommending that GSL be awarded the contract indicated that the pricing changes that had been allowed to GSL's bid were based on scenario E. However, the manner in which DIMIA had modified the criteria used to calculate scenario E meant that key factors relating to the operation of the Woomera and Christmas Island facilities, (that had been used in the evaluation process up to this point), were inconsistently applied to GSL's pricing change. It also meant that comparisons with ACM's bid could no longer be undertaken on a ‘like with like' basis, as the modified criteria were not applied to ACM's tendered prices. In those circumstances, the steering committee should have formally addressed in its advice and recommendations to the delegate, whether its departure from the preferred scenario meant that the value for money basis on which the preferred tenderer had been selected was still valid. That was not the case in this tender process. The final report of the evaluation indicated to the delegate that the comparisons for all price changes accepted were undertaken against the 4 year NPV price for scenario E ‘-as per the tender evaluation'.

Amortisation of start-up costs

61. In its original tender bid GSL assumed that it would hold the contract for the initial four years on offer through the tender, plus the extension period in the contract of three years. Therefore, it had amortised its start-up costs over a period of seven years. This assumption had the effect, throughout the tender and evaluation process, of making the tendered cost of four-year service provision more attractive than its competitors (ACM's bid was based on a four year amortisation of start up costs). In March 2003, GSL sought to modify its pricing to cover the possibility that the Commonwealth exercised its discretion to not extend the term beyond the initial period of four years.

62. This request had been considered earlier by DIMIA's specialist advisors and was covered in the advice to the steering committee of 17 February 2003 that recommended that DIMIA proceed to parallel negotiations. This advice was considered and rejected by the steering committee, in favour of continued negotiations with GSL. These negotiations culminated in a letter from GSL to DIMIA on 17 March 2003, which requested it be allowed to re-amortise its start up costs over four years on the basis that

….the possible consequential expiry of the contract after four years, imposes a substantial risk on our anticipated margins over the full length of the contract.

63. The steering committee subsequently provided GSL with the opportunity to increase its prices through re-amortisation of its start-up costs, although the resultant price increase was not brought to account in DIMIA's value for money calculation. \

64. DIMIA determined, in the first instance, that GSL's request was not a re-pricing and that a probity issue did not arise. However, the ANAO notes that a preliminary probity question surrounding GSL's request was whether or not the pricing change was eligible to be considered in accordance with the terms and conditions of the RFT which provided that:

If a Tenderer becomes aware of any clerical or administrative error or omission in its tender …the Tenderer may lodge …a written correction to its tender. The Commonwealth, at its discretion, may elect to accept any such correction.

65. The ANAO notes that GSL did not argue that it had made an administrative error or omission in its tender; it argued that its profit margin was at risk if it did not hold the contract for seven years. Whether or not this request complied with the terms and conditions of the RFT was not addressed as part of DIMIA's initial decision.

66. The steering committee also did not bring together differing views between its probity advisor and advice from its other experts as to whether GSL's request should be accepted. In particular, legal advice provided to the steering committee indicated the pricing change should not be allowed. DIMIA's financial advisor also maintained in advice provided to the steering committee, up to and including the day the contract was signed, that the pricing change should be brought to account as part of the value for money calculation.

67. At the time this pricing change was accepted by the steering committee, ANAO analysis shows that it added $4.1 million (NPV) to GSL's tendered amount. This increase was subsequently revised downwards following negotiations over the Woomera and Christmas Island overheads re-allocation discussed earlier, and settled at $2.943 million (NPV). The ANAO notes that in the final minute to the delegate, recommending that the Commonwealth enter into the contract with GSL, the effect of this change on GSL's bid was listed in the attachments as ‘TBA'. 10

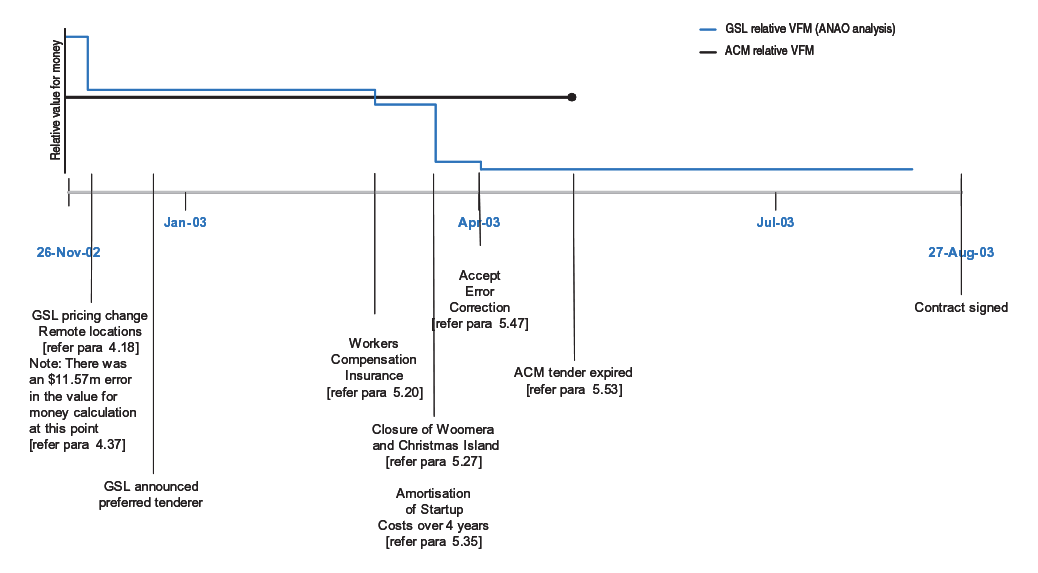

Overall reconciliation of changes in relative value for money

68. Contract negotiations were protracted and many of the adjustments made to GSL's tendered prices were not finalised until very late in the negotiation phase. However, at the time the changes were accepted, the available figures and DIMIA's own analysis showed that the relative position of the tenderers in DIMIA's value for money index had changed. In some instances there is not a clear record of the steering committee formally agreeing to the financial commitment it was accepting on behalf of the Commonwealth that would flow through to the price of the contract, following each pricing change. However, the actual changes were substantial and the ANAO's analysis of movements in relative value for money is shown in Figure 1.

69. As discussed at paragraph 49 above, the steering committee and the probity advisor have advised the ANAO that in response to early pricing change requests from GSL a step-by-step process was developed to manage pricing adjustments accepted during contract negotiations. That process foreshadowed a reconciliation of GSL's price increases and the conduct of a review of the relative value for money against ACM's tender, ‘to ensure the best possible value for money outcome'. The ANAO found no evidence that this review was undertaken.

70. Overall, the ANAO found that there was a lack of transparency in the decision making process in the acceptance of increased prices in the preferred tenderer's bid, particularly in the later stages of the tender. The steering committee did not bring to a conclusion the ‘step-by-step' process it set for itself at the meeting of 18 February 2003 and did not reconcile legal and financial advice that differed from probity advice into an overall DIMIA position. This meant there was no systematic basis for reviewing the value for money index system as envisaged by the steering committee. ANAO analysis shows that the cumulative effect of the pricing changes accepted during contract negotiations between February and May 2003 (the point where ACM's tender bid expired) had added $21 million (NPV) to the price of GSL's bid. This does not include the $11.57 million (NPV) adjustment needed to correct the earlier error, discussed at paragraph 41 above.

The elimination of ACM from the tender process

71. In a competitive process, where the two final tenderers could not be separated through any significant measure or indicator, and where the option of parallel negotiations had been rejected, there was an obligation on the steering committee to satisfy itself that contract negotiations with the preferred tenderer would result in the best outcome for the Commonwealth being accepted. ACM had provided a bid that met higher technical (service delivery) standards, and the delegate had decided that ACM should be invited to keep its tender offer open until contract negotiations were finalised. This would have assisted DIMIA in keeping open the available options in the event that GSL sought to increase its prices further, transfer risks to the Commonwealth through the insurance, liability and indemnity regime, or was otherwise unable or unwilling to continue with contract negotiations.

72. Because delays were experienced in contract negotiations with GSL, DIMIA wrote to ACM on three separate occasions, in February, March and April of 2003, to request extensions to its tender offer. On 30 April, on the occasion of the third and final request for ACM to keep its tender offer open, ACM responded that it would be prepared to extend the validity of its tender offer, subject to several conditions related to updated costings. The ANAO found that DIMIA did not respond to ACM's conditions and, as a result, ACM's offer expired on 2 May 2003 (before the completion of contract negotiations with GSL on 27 August 2003).

73. The rationale for the elimination of ACM from the tender process was not documented. As previously noted, there were no steering committee meetings held between 15 May 2003 and 21 August 2003 and, as a result, there is no record of DIMIA's consideration of this matter. There is also no evidence that the delegate was informed that ACM's tender offer had expired. This was a significant development and was at odds with the initial decision of the delegate to keep ACM's tender offer open until completion of contract negotiations. It also meant that there were no alternative tenderers remaining and the negotiating position of the Commonwealth had altered considerably as a result. ACM was ultimately informed that its tender bid was unsuccessful after the contract with GSL was signed on 27 August 2003.

Completion payments for ACM

74. At the same time as DIMIA was writing to ACM requesting extension of the tender offer period, the delegate and the Minister were informed that discussions were continuing with ACM on transition arrangements, including ACM's costs associated with transition. The advice, dated 25 March 2003, stated that DIMIA was proposing to ‘encourage' ACM's successful transition out by offering a ‘completion payment'. In a pen script note to this advice, the delegate advised the Minister that authorisation for the completion payment would be arranged through an exchange of letters.

75. The ANAO notes that the general agreement makes no provision for completion payments, except where the contract is terminated for convenience, which DIMIA elected not to do. DIMIA was not able to provide evidence of the criteria it used to make its determination to pay ACM $5.7 million in contract completion payments. The exchange of letters brought the payments into the (then) existing contract with ACM under the ‘out of scope' provisions. The ANAO notes that the ‘out of scope' provisions of the previous contractual arrangements were intended to cover contingencies associated with the provision of detention services, not payments designed to encourage a successful transition to a new service provider. Accordingly, the basis on which DIMIA made these payments was doubtful.

76. The risks to the tender process arising from the introduction of contract completion payments was not evaluated in any of the tender documentation provided by DIMIA in respect of this procurement. DIMIA was unable to provide evidence of any action by the steering committee to consider and/or evaluate the potential impact of this transaction on achieving a value for money outcome for the Commonwealth.

Figure 1 Overall reconciliation of changes in value for money index

Source: ANAO from DIMIA data - paragraph references refer to Chapters in the report.

Management of Liability, Indemnity and Insurance (Chapter 6)

77. A significant risk for the Commonwealth in outsourcing the management of detention centres is the potential for claims arising from major disturbances11. In their tender submissions, both ACM and GSL placed conditions on being held liable for detainee damage. ACM's conditions related to minor repairs. GSL's conditions related to major incidents leading to significant damage to Commonwealth property or assets. GSL's tender bid was also conditional upon liability caps being provided by the Commonwealth that matched the level of insurance that GSL was able to purchase. The conditions for a cap on liability for detainee damage being requested by GSL represented an arrangement that was of higher inherent risk for the Commonwealth than that offered by ACM.

78. At the time GSL was announced as preferred tenderer, the required insurances had not been finalised by GSL, and the liability caps were not settled. The potential impact of these conditions, and the resultant uncertainties, were not addressed by DIMIA prior to contract negotiations. DIMIA then approached GSL, as the preferred tenderer, to assist in developing ‘a realistic proposal for a cap on liability' for detainee damage before holding discussions with Comcover to determine the optimum balance of risks to be carried by the service provider and the Commonwealth. The resultant liability, indemnity, and insurance regime 12in the Commonwealth's contract with GSL is that GSL's liability is capped at $0.5 million per event or $2.5 million per year for all detainee damage claims. There is also a significant risk that the Commonwealth will be deprived of the benefit of the $20 million of insurance cover purchased by GSL, and designed to cover claims other than those resulting from detainee damage. 13

79. For a contract of this complexity, it was important that DIMIA identify, analyse and evaluate all risks to ensure that the Commonwealth's commercial position was adequately protected throughout the tender process. The ANAO found that in negotiating, and then setting the insurance, liability and indemnity regime, DIMIA placed the Commonwealth in a disadvantageous position due to a lack of proper consideration and, when necessary, reconsideration of the costs and benefits of the liability and indemnity arrangements. In part this was because the capacity of the Commonwealth to negotiate was diminished by the expiry of ACM's tender offer before contract negotiations were finalised and, in part, because a rigorous assessment of risks was not undertaken.

DIMIA's advice to the delegate and Government

80. The steering committee advised the delegate and the Government that the proposed insurance, liability and indemnity arrangements in the contract represented the best financial outcome for the Commonwealth. However, the ANAO found that although DIMIA had consulted with Comcover, it did not closely engage until after GSL was announced as the preferred tenderer. By this time, significant indemnities had already been provided by DIMIA, and GSL was seeking to increase these further to match its available insurance cover.

81. The requests from GSL to increase the indemnities on offer resulted in DIMIA initiating correspondence between the then Minister for Immigration, the Finance Minister and the Prime Minister. The ANAO found that DIMIA's input into the correspondence was based on an incorrect assessment of the tenderer responses. The significant features were:

- DIMIA did not recognise early that the indemnities being provided would require approval from the Finance Minister under Regulation 10 of the FMA Act;

- when the Regulation 10 matter was raised with Finance, Comcover became involved and highlighted difficulties with the operation of insurance cover given the indemnities DIMIA had provided;

- ACM and GSL bids were not assessed on equal terms after Comcover raised these difficulties with DIMIA. The preferred tenderer was invited to propose ‘workable solutions' without DIMIA seeking probity advice and without the ability to consider ACM's offer, the next ranked tenderer; and

- ACM's position on liability for detainee damage was incorrectly stated by DIMIA.

82. DIMIA was also unable to provide evidence of any analysis and costings that would support the assertion made by DIMIA to Ministers that the proposed indemnities represented the best financial outcome for the Commonwealth.

Audit conclusion

83. DIMIA initially established a sound evaluation process that was capable of taking into account the value for money requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines, incorporating all costs and benefits over the whole of the procurement cycle. DIMIA's evaluation process provided a method to discriminate between tenderers on the basis of the quality of detention services being proposed, as well as the price being offered. In the event that two or more tenderers could not be separated because of compensating differences, the process also provided for parallel negotiations, a best and final offer and a residual risk analysis to assist the delegate in making a final decision.

84. In order to be in the best position to determine value for money, DIMIA needed to ensure that the approved evaluation process was followed. Accountability and transparency in DIMIA's process was also required to provide assurance that this procurement, valued at $400 million, was conducted in a manner that provided fair and equal consideration of all tenders. This in turn would provide assurance that the best offer for the Commonwealth had been identified, and allow the process to withstand external scrutiny.

85. DIMIA's evaluation framework included the appointment of specialist advisors in law, finance and probity. The tender process conducted by DIMIA was a complex, resource intensive activity and in these circumstances it was appropriate to engage advisors and other consultants as necessary to supplement the skills of agency staff. However, the use of specialist expertise, including probity advisors and probity auditors, in the procurement process does not reduce accountability for the outcome. It also does not obviate the need for sound internal management and recordkeeping to support accountability and transparency in a tender process.

86. ACM submitted a tender bid that DIMIA evaluated as having met higher standards of proposed service delivery than either of the other two tenderers, GSL and MTC. The technical evaluation scores, once awarded, were held constant in determining value for money. The only variable DIMIA subsequently changed in deciding value for money was price. Therefore, close attention was required from DIMIA's steering committee to the initial prices submitted by the tenderers; to any requests to amend prices; and to ensure that the overall price to the Commonwealth, including the indemnities being offered, were taken into account.

87. There was an $11.5 million pricing error in favour of GSL in the initial report to the delegate of the evaluation outcome in November 2002. Although this error did not alter the overall ranking of the two final tenderers GSL and ACM, it brought them to within less than 1 per cent of each other in DIMIA's value for money rating. This error remained undetected through nine months of subsequent contract negotiations. On the basis of the evaluation, the delegate decided to select GSL as the preferred tenderer, and to invite ACM to keep its tender bid open until completion of contract negotiations.

88. After GSL was selected as the preferred tenderer, contract negotiation became protracted. This was due in large part to DIMIA not ensuring that GSL's tender was fully compliant with the insurance, liability and indemnity provisions of the request for tender (RFT) before GSL was recommended as the preferred tenderer. At the same time, contract negotiations included requests from GSL to amend its tendered prices. In considering these requests, DIMIA's specialist advisors identified that accepting the pricing changes would alter the value for money rankings. As a way of managing the impact of pricing changes on the value for money rankings during contract negotiations, advisors suggested DIMIA should re-visit GSL's offer and re-assess that offer through a step-by-step process that would allow an assessment of the need to enter into parallel negotiations with GSL and ACM.

89. DIMIA did not bring this process to a conclusion and there was a lack of transparency in the decision-making processes that led to the acceptance of GSL's revised prices. In response to the ANAO's view that DIMIA did not systematically monitor value for money throughout the process, late in the audit an additional document was provided to the ANAO. This document was not held on DIMIA's files, and while it contained errors, it clearly showed ACM was ahead of GSL in the value for money rankings in February 2003. Notwithstanding assertions by a member of the steering committee that this was an example of monitoring value for money, there is no evidence this document was considered by the steering committee.

90. As contract negotiations continued past May 2003, ACM's tender bid expired. There was a cessation of all formal meetings between the steering committee between May and August 2003. As a result, DIMIA was unable to provide documentation that identified the reasons why ACM's offer was allowed to lapse and the basis on which ACM was eliminated from the process. At the time ACM's bid expired, ANAO analyis shows that a total of $32.6 million had been added to GSL's tendered price.

91. On 22 August 2003, a document prepared by DIMIA's steering committee invited DIMIA's secretary to approve entering into the contract with GSL on the basis of value for money. This minute also invited the secretary to note that ACM would be (after contract signature on 27 August 2003) formally advised that its tender was unsuccessful. This advice to the delegate represented the outcome of a procurement process that took 27 months to complete. At important stages of the process, DIMIA's steering committee did not follow the approved evaluation method, for reasons that are not well documented. This led to a number of errors and omissions in both the evaluation and contract negotiation phases of this procurement. Errors that occurred during the evaluation stage compromised the Commonwealth's negotiation of the contract with GSL. The ANAO was, for example, unable to verify the basis of the claim DIMIA made to the Government that the negotiated outcome of the insurance, liability and indemnity regime represented the best financial outcome for the Commonwealth.

92. At the point of selection of GSL as the preferred tenderer, the cost-benefit ratio of GSL's proposal was overstated, relative to ACM. Subsequent negotiations increased the costs of GSL's proposal to the point where the application of the methodology employed by DIMIA ranked ACM ahead of GSL, at the time ACM's tender offer expired. That said, it is not possible to know, in different circumstances, how responses by the two final tenderers may have altered their proposals, or how the delegate may have weighed the various factors required in reaching his decision on which proposal represented the best value for money for the Australian Government. In response to inquiry by the ANAO, the delegate has advised that there were no factors or influences other than those identified in the tender evaluation plan which would have been taken into account in making the decision in this matter.

93. The CPGs issued by the Finance Minister are designed to ensure suppliers of services for Australian Government agencies are treated fairly and equitably, that agencies receive value for money for resources expended, and that the community has confidence in the procurement practices employed by agencies. In this case, the procurement practices employed by DIMIA to acquire detention services fell well short of the standard expected by the CPGs. The department put in place an appropriate plan to evaluate the costs and benefits of competing solutions from tenderers, but failed to follow through effectively in the implementation of its plan. Shortcomings identified by the audit include:

- ambiguity in DIMIA's management of the roles and responsibilities of key advisors and personnel;

- deficient recordkeeping, impacting DIMIA's ability to demonstrate accountability and transparency in this procurement;

- weaknesses in the conduct and documentation of contract negotiations; and

- deficiencies in the assessment of tender bids against the value for money criteria.

94. As indicated by the agency's response (below), the department is implementing a wide range of measures to improve administration and has responded positively to the matters raised by the audit and the recommendations to enhance procurement practices in the department.

Agency response

95. The ANAO's audit of the Detention Services Contract tender process has highlighted a number of areas in which procurement, tendering and recordkeeping processes could be improved.

96. In October 2005, a wide range of measures to improve administration within the Department were announced by the Minister as part of the Government's response to the Palmer 14 and Comrie15 reports.

97. The measures included significant organisational changes, including the introduction of a centre of excellence for contract and procurement processes. A number of initiatives designed to strengthen the department's procurement assurance framework are underway, focussing on the early detection and better management of procurement risks.

98. In addition, the department will develop new recordkeeping guidelines specific to tendering and procurement processes. Improved records management processes will also be mandated through IT systems changes.

99. The Department considers that these measures will address the key concerns of the ANAO's recommendations, which the department has accepted.

100. DIMA's full response is attached at Appendix 2.

Footnotes

1 On 27 January 2006, the office of Indigenous Policy Coordination was moved from the Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs portfolio to the new Department of Family, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. At the time of the ANAO's field work for this audit, detention services were administered by the Department of Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs and is abbreviated to DIMIA throughout the report.

2 Mainland Detention Facilities at this time were located at Port Hedland (WA), Perth (WA) Maribyrnong (Vic), and at Villawood (NSW). In 2000 a centre at Woomera (SA) was opened and in 2003, Baxter (SA) also commenced operations.

3 APS subsequently withdrew its tender before tenders closed.

4 Department of Finance and Administration, ‘Procurement Guidance', Ethics and Probity in Government Procurement, http://www.finance.gov.au/ctc/etchic__probity-probity_exper.html.

5 Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), Probity and probity advising – guidelines for managing public sector projects, November 2005, pp. 15.

6 Subsequently it was announced that the facility on Christmas Island would also close, although it re opened later in 2003.

7 On 28 August 2002.

8 The request from ACM involved a re-distribution of its corporate costs between Maribyrnong, Perth and Villawood IDC's and Baxter IRPC.

9 Discussed in more detail at table 4.8 in Chapter 4 of the report.

10 The ANAO assumes this to mean ‘to be advised'.

11 The operation of the insurance, liability and indemnity regime in the Contract is discussed in more detail in ANAO report No. 1 of 2005–06 – Management of the Detention Centre Contracts – Part B, p.51

12 ibid, p. 61.

13 ibid, p. 62.

14 Palmer, Inquiry into the Circumstances of the Immigration Detention of Cornelia Rau, Report, July 2005, <http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media_releases/media05/palmer-report.pd…; [last accessed 17 January 2006]

15 Commonwealth Ombudsman, Report No. 03/2005, Inquiry into the Circumstances of the Vivian Alvarez Matter, September 2005, <http://www.comb.gov.au/publications_information/Special_Reports/2005/al…; [last accessed 17 January 2006]