Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Tender Process for a Replacement BasicsCard

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DHS' management of the tender process for a replacement BasicsCard to support the delivery of the income management scheme.

In conducting the audit, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) assessed the following five key areas of the replacement BasicsCard procurement process, which are described in the Department of Finance and Deregulation's (Finance) Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures :

• planning for the procurement;

• preparing to approach the market;

• approaching the market;

• evaluating tender submissions; and

• concluding the procurement, including contract negotiation.

Summary

Introduction

Income management was part of a package of measures introduced by the former Government in response to the public release of the 2007 report Little Children are Sacred, authored by the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse. Income management was announced as part of the Government's 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response. The key measures in the response were designed to protect children and make communities safer for people living in Indigenous communities and town camps in the Northern Territory.

Income management operates by directing a fixed percentage (between 50 and 70 per cent) of most income support and family assistance payments, and 100 per cent of an individual's advance and lump sum payments, to the purchase of essential goods and services. Details of the income management scheme are contained in the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 (Cwlth).

The BasicsCard was developed to support the delivery of the income management scheme. The reusable, PIN (personal identification number) protected card allows social security recipients, subject to income management, to purchase essential goods and services, such as food, clothing and medicine. The BasicsCard cannot be used to purchase alcohol, tobacco, pornographic material, gambling services and products, and homebrew kits. In December 2010, there were approximately 17 000 active BasicsCards being used by individual social security recipients in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Before the BasicsCard was introduced, social security recipients' funds were income managed in a number of ways: by issuing store cards from selected merchants (for example, Woolworths and Coles); by direct deduction of funds from an account set up at a specified merchant; or by Centrelink making a credit card or cheque payment. In early 2009, the arrangements were considered to lack flexibility, be time consuming and restrict choice for social security recipients. Merchants found the processes expensive and administratively time consuming. The arrangements were also cumbersome for Centrelink to administer.

The BasicsCard is accepted at approved stores and businesses and operates via the electronic funds transfer at point of sale system (commonly known as the EFTPOS system, which is used for processing transactions through terminals at points of sale). The BasicsCard cannot be used to obtain cash at an automatic teller machine, or from an EFTPOS terminal in a store, and cannot be used to transfer funds between bank accounts.

Income management, and use of the BasicsCard, does not reduce a social security recipient's payment entitlements. The remaining part of recipients' payments is delivered as usual, and there are no restrictions on how that money is spent.

The Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform and Reinstatement of Racial Discrimination Act) Act 2010 (Cwlth) received Royal Assent on 29 June 2010. From 1 July 2010, a new more broadly based model of income management (that replaces income management under the Northern Territory Emergency Response) was rolled-out across the Northern Territory, to an estimated 20 000 people, at a cost of $350 million over four years. It was intended that the majority of customers would be transitioned to the new model of income management by 31 December 2010, with all customers transitioned by 30 June 2011.

The new model is targeted at specific categories of people receiving social security payments, for example, disengaged youth and long-term welfare recipients, who the Government considers to be among the most disengaged and disadvantaged individuals in the welfare system. By adopting this approach, the Government is seeking to ensure that income management is applied independent of race and is non-discriminatory.[1] As part of the roll-out, entrelink contacted customers to discuss whether they would be required to be subject to income management under the new mode0l. If customers were not required to be subject to income management, they could elect to continue to have their welfare payments income managed, under the voluntary income management arrangements.

The Government has undertaken to review the reforms to income management and to use the first evaluation progress report, expected in 2011–12, to inform the potential future roll-out of the new model in other parts of Australia.

The BasicsCard has become a recognisable and central element in the delivery of the Australian Government's income management scheme. Since its introduction in September 2008, until December 2010, the BasicsCard has been used to spend some $193 million on essential goods and services, such as food, clothing and medicine.

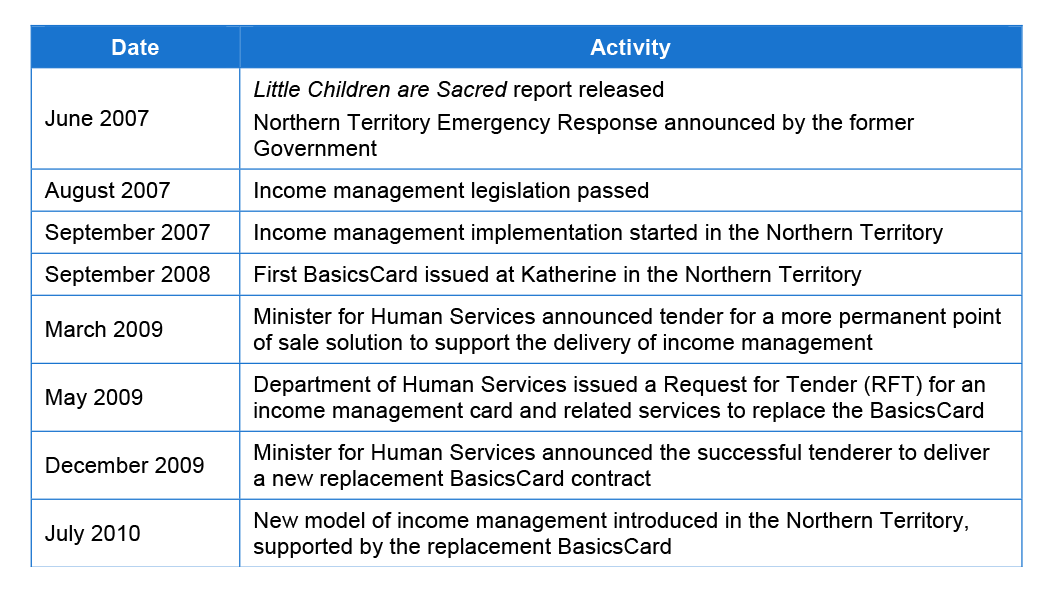

Table S 1 summarises the history of income management and the BasicsCard.

Table S 1 Introduction of income management and the BasicsCard

Source: Department of Human Services, Income Management Card and Related Services (RFT09DHS146), Industry Briefings 10 & 11 June 2009 and ANAO analysis.

Agency roles and responsibilities

There are three Australian Government agencies involved in the delivery of income management and the administration of the BasicsCard:

- The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) is responsible for providing advice to the Government on income management policy that determines the use of the BasicsCard.

- The Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for providing a central policy and coordination role for the delivery of services across the Human Services portfolio, which included the procurement of the first BasicsCard in 2008 and replacement BasicsCard (the focus of this audit) in 2009.[2]

- Centrelink is responsible for service delivery of the BasicsCard for both customers and merchants.

Income Management Card Replacement Project

In 2008–09, DHS managed the direct sourcing of a provider to deliver an income management card solution to support income management in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. The contract, which was signed in July 2008 and initially set to expire on 30 June 2009, was a temporary measure until an open tender could be conducted for a more permanent point of sale solution.

The first BasicsCard contract was extended to June 2010 to enable DHS to carry out an open procurement for a replacement BasicsCard. The replacement BasicsCard was to provide for the uninterrupted delivery of existing services and ensure a flexible card solution was procured that could meet any future government requirements for income management. This decision reflected DHS' view that it was unlikely to be able to procure additional services (beyond June 2010) from the first BasicsCard contractor, using another direct source procurement, without contravening the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines.[3] Furthermore, the department would require up to 15 months to conduct an open tender process for a replacement BasicsCard and transition to any new arrangements.

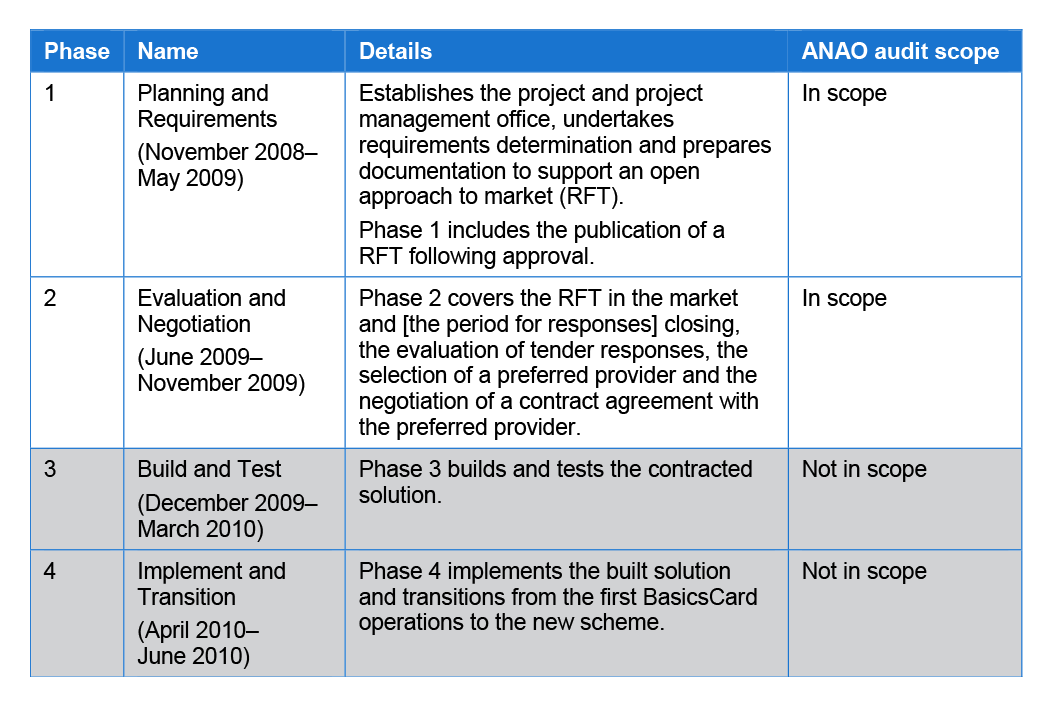

In late 2008, DHS received funding of $7.8 million over two years (2008–09 and 2009–10) to undertake a more permanent BasicsCard procurement using an open tender.[4] The funding was for phases one and two of a larger-phase Income Management Card Replacement Project carried out by DHS and shown in Table S 2.

Table S 2 Income Management Card Replacement Project

Source: DHS, Income Management Card Replacement Project, Phase 2 – Evaluation and Negotiation, End Stage Report, February 2010.

Note: Phases 3 and 4 of the Income Management Card Replacement Project are outside of the scope of this audit. For details of the audit objective, criteria and scope see paragraph 19.

In March 2009, the then Minister for Human Services announced that a tender would occur for a replacement BasicsCard, and a Request for Tender (RFT) was published in May 2009. DHS received five tender submissions by the closing date in July 2009. Two submissions were compliant with the conditions for participation in the RFT and were subsequently considered by the Tender Evaluation Committee.

After assessing the two submissions, the Tender Evaluation Committee determined each tenderer was capable of providing an income management card solution in accordance with the RFT, however, the major point of differentiation was the total price. The prime contractor's (Indue Ltd, referred to as the ‘prime contractor' in this report) tender submission was significantly lower than that of the second submission.[5] The Tender Evaluation Committee unanimously recommended the preferred tender proceed to the contract negotiation stage.

Following contract signature in late November 2009, the successful new prime contractor was publicly announced in December 2009. The first six months of the initial contract term required a transition phase from the original card to the replacement card, which involved the two contractors, existing BasicsCard customers and Centrelink.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DHS' management of the tender process for a replacement BasicsCard to support the delivery of the income management scheme.

In conducting the audit, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) assessed the following five key areas of the replacement BasicsCard procurement process, which are described in the Department of Finance and Deregulation's (Finance) Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures:

- planning for the procurement;

- preparing to approach the market;

- approaching the market;

- evaluating tender submissions; and

- concluding the procurement, including contract negotiation.

The audit scope included an examination of the first two phases of the Income Management Card Replacement Project.

Overall Conclusion

The BasicsCard was developed to support the delivery of the income management scheme. Income management was one of a package of measures, introduced by the former Government as part of the 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response to the release of the 2007 report Little Children are Sacred, authored by the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse. Income management was designed to protect the welfare of children and vulnerable people in certain communities by directing a fixed percentage (between 50 and 70 per cent) of most income support and family assistance payments, and 100 per cent of an individual's advance and lump sum payments, to the purchase of essential goods and services.

From 1 July 2010, a new model of income management was introduced in the Northern Territory, to an estimated 20 000 people, at a cost of $350 million over four years. The new model is targeted at specific categories of people receiving social security payments, for example, disengaged youth and long-term welfare recipients, who the Government considers to be among the most disengaged and disadvantaged individuals in the welfare system.

The BasicsCard helps facilitate income management through providing social security recipients with a reusable, PIN protected card that allows people to purchase essential goods and services, such as food, clothing and medicine. As at 30 December 2010, approximately 17 000 active BasicsCards were being used by individual welfare recipients, with some $193 million having been spent since the introduction of the card in September 2008.

Following the decision to introduce income management and, subsequently, a card payment option to support the scheme's implementation, DHS managed the initial direct sourcing procurement of a card solution to support the introduction of income management. The initial contract was a temporary measure until an open tender could be conducted for a more permanent point of sale solution. The two stage contract approach was designed to also allow for a more flexible card solution to be procured that could meet any future government requirements for income management, while also ensuring the uninterrupted delivery of existing services.

Overall, during the period from November 2008–November 2009, DHS effectively managed the tender process for a replacement BasicsCard to support the delivery of the income management scheme.[6] DHS' management of the replacement BasicsCard procurement allowed the tender to be conducted within the required timeframe and budget.

The procurement culminated in November 2009, when a three-year service delivery contract for the operation of the BasicsCard was signed with Indue Ltd (the prime contractor). The contract is valued at approximately $11 million and runs for the period July 2010–June 2013. The contract also includes an option to extend the initial three-year operational term for up to a further two years.

DHS demonstrated sound procurement and management practice and acted in a manner consistent with Finance's operational guidance to agencies contained in the Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures.[7] In planning and managing the procurement, including approaching the market, evaluating tender submissions and conducting contract negotiations, DHS also complied with the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines.[8]

DHS' approach to planning the replacement BasicsCard procurement responded to an important opportunity to address the existing criticisms of the BasicsCard, such as limited options for card users to make account balance inquiries and individual customers having a high number of transactions declined. Additionally, the lessons learned from the operation of the first BasicsCard informed the approach to the market for the card's functionality including the level of operational performance that would potentially be required to support income management into the future.

Key findings

Planning (Chapters 2–3)

DHS' preparation for the replacement BasicsCard procurement included developing a procurement plan, request document and submission evaluation plan that were consistent with the Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures.

Overall, DHS undertook sufficient planning in 2008 and 2009 for the replacement BasicsCard procurement, with the exception of the timely preparation of a business case.[9] DHS had Government authority to undertake the procurement and chose to delay the preparation of a business case for the replacement BasicsCard procurement until during the evaluation stage of the procurement in September 2009. In the interim, a delay in finalising the procurement's scope affected the project's original schedule, drafted in December 2008, by moving the timetable for contract signature from August 2009 to November 2009.

At the same time DHS was settling the scope of the replacement BasicsCard procurement, the Government was deliberating on the future of income management. An earlier focus on developing a business case, including defining the outcome, however, could have assisted with defining the procurement's scope sooner and with less impact on the procurement's overall schedule.

Management (Chapters 4–6)

As a relatively small agency, with a high profile and time-limited procurement to conduct, DHS was reliant upon the assistance of a number of external advisers to undertake the replacement BasicsCard procurement. Engaging external advisers is a common practice used by agencies to supplement existing resources with expertise and/or independence in particular areas. The extent of the advice required can be determined by considering the procurement's scale, value and risk (of contract failure to service delivery and harm to agency reputation).

DHS engaged separate business, financial sector, legal and probity advisers, at a total cost of approximately $6 million, to support the management of the replacement BasicsCard procurement.[10] While the cost of advisers represented a significant proportion of the total cost of managing the procurement (approximately $7.1 million), DHS' reasons for using external advisers included legal complexity, time pressures and internal resource constraints and limitations.

DHS released a request document (RFT) to the market in May 2009 for an open tender process. DHS' approach to the market for the replacement BasicsCard procurement was consistent with the Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures. DHS followed sound practice for agency procurement—notifying suppliers and issuing four RFT addenda via AusTender.

DHS effectively administered the submission evaluation process for five responses received to the RFT for a replacement BasicsCard. DHS' initial three stage evaluation process was consistent with the Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures. The submission evaluation process was largely completed on schedule, with no major probity issues identified.

The fourth and final stage of the procurement centred on the contract negotiation. DHS completed this stage on schedule, including fulfilling the relevant Financial Management and Accountability Regulations requirements. A productive working relationship established between FaHCSIA, DHS and Centrelink during the procurement process contributed to the finalisation of a new replacement BasicsCard contract.

Future procurements

There were some procedural aspects of DHS' planning and management of the process that could be improved for future procurements undertaken by the department. These areas include:

- tailoring the governance arrangements to the nature of the procurement such that resource intensive governance and reporting structures can be better managed to avoid overlaps and scheduling conflicts; and

- ensuring tender evaluation reports contain information about any RFT addenda and responses to tenderers' clarification questions that were published on AusTender before the close of the tender. Including this information for the replacement BasicsCard procurement would have improved DHS' record of the RFT process and better informed the Project Sponsor whose endorsement was requested for the stage one evaluation report.

Summary of agency response

The Department of Human Services welcomes the ANAO performance audit of the management of the tender process for a replacement BasicsCard and notes that the ANAO has not made any recommendations for action by the Department. The Department is encouraged that the ANAO has acknowledged that the Department managed the tender process for the replacement BasicsCard effectively and in accordance with sound practice. The Department is also pleased that the ANAO recognised that the productive working relationship between the Department, Centrelink and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs contributed to the successful finalisation of the new BasicsCard contract.

The Department of Human Services notes that the project was required to achieve contract signature with the successful provider by no later than November 2009 in order to ensure that there was a smooth transition from the first BasicsCard product to the replacement BasicsCard on 30 June 2010. This imposed timing pressures on the project, as any delay in the availability of the replacement BasicsCard would have made the delivery of the Government's income management policy after 30 June 2010 very difficult.

The Department of Human Services agrees with the suggestions made by the ANAO in the report about how future procurement processes could be improved and will give weight to these suggestions when planning future complex procurements.

Footnotes

[1] Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Policy Statement: Landmark Reform to the Welfare System, Reinstatement of the Racial Discrimination Act, and Strengthening of the Northern Territory Emergency Response [Internet]. FaHCSIA, 2009, available from <http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/indigenous/pubs/nter_reports/policy_statement_nter/Documents/landmark_reform_welfare_system.pdf> [accessed 29 November 2010].

[2] The Department of Human Services includes the Child Support Agency and CRS Australia. Details are available from DHS' website <http://www.dhs.gov.au/> [accessed 11 October 2010].

[3] Department of Finance and Deregulation, Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines, Financial Management Guidance No.1, Finance, Canberra, 2008.

[4] The funding was included in the Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2008-09, Human Services Portfolio, ‘Payment Delivery–Enhanced Arrangements', p. 14.

[5] In late August 2009, in accordance with the RFT conditions, DHS issued a notification to the two tenderers of a variation to the RFT covering revised technical requirements for balance enquiry facilities and transactions. The notification also included an associated request for additional pricing information. There were no restrictions on the scope of the price revisions that tenderers could make, therefore, the tenderers' repricing submissions superseded the original pricing response for the RFT. After the repricing exercise, DHS also made normalisation adjustments during the pricing evaluation to enable a like-for-like comparison of the tenderers' proposed prices.

[6] The purpose of the Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures is to: ‘assist Australian Government departments and agencies in implementing the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines and specifically the Mandatory Procurement Procedures'. See Finance's website for publications and reports, available from <http://www.finance.gov.au>.

[7] Department of Finance and Deregulation, Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures, Financial Management Guidance No.13,Finance, Canberra, 2005.

[8] Finance, Procurement Guidelines, op. cit.

[9] The Guidance on the Mandatory Procurement Procedures outlines various issues an agency should consider when planning a covered procurement and how an agency's planning activities should culminate in the development of a business case. The purpose of a business case is to explain why a procurement should be undertaken and how it will deliver value for money. The minimum content for a business case includes setting out resourcing requirements, a list of stakeholders and a cost-benefit analysis.

[10] DHS also contracted Deloitte from November–December 2008 to deliver a post-implementation review of the first BasicsCard and advice on point of sale solutions. The total cost of the advisers is based upon the cost of the four main advisers during the procurement and Deloitte's early work. See Chapter 6.