Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Standard Defence Supply System Upgrade

The audit on the Defence Project Management of the SDSS Upgrade Project examined Defence project management procedures and practices in the information management systems domain.

Summary

Background

1. The Standard Defence Supply System (SDSS) version 4 spans the three Services in its coverage of logistics management and is intended to be a key information system for financial management of Defence assets, and equally importantly, to facilitate Defence's materiel management capability1. The system operates with more than 14000 users over 135 separate geographically diverse business units utilising 1162 warehouses. In keeping with Defence policy, the ANAO has assessed that the system qualifies as a Strategic system.

2. The activities undertaken to provide an improved materiel management capability comprised the SDSS Upgrade Project (the Project) and other elements, to be delivered by a number of related projects2. The ANAO has taken the baseline for the Project from the scope, and associated budget, defined in the approved Equipment Acquisition Strategy.

3. In July 2000, the Project was initiated with an approved budget of $15.87 million with the main aim of delivering a Standard Supply Chain System across Defence by June 2002. The Project was to combine the implementation of a new version of the operating software with improvements to the management of the Defence supply chain and supporting infrastructure. This enhancement, once rolled out, was intended to deliver an integrated system with which Defence could manage its spares inventory, accounting for over 1.6 million categories of stores, valued at some $1.9 billion.

4. As of November 2003, the Project had incurred costs of $49.9 million, excluding $5.1 million in contract residuals contributed by e-Procurement and SDSS version 3 legacy training projects. Defence advise that the formal Project closure will be dependent on the delivery of the financial reporting functionality expected of the SDSS version 4 system.

5. Defence manage acquisition projects under two main categories: Major Capital Equipment projects, which, at the time the Project was undertaken, were centrally located and managed by the Defence Acquisition Organisation in Canberra; and Minor Capital Equipment projects, which were controlled by any of the then 14 Defence Groups, which included the Support Command Group.

6. The Defence logistics environment is managed by the Joint Logistics Command, which is based in Melbourne. The Project was initiated by the Support Command Australia, which was the antecedent of the Joint Logistics Command. The Project was later transferred to be managed by the Management Information Systems Division (MISD) within the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO).

7. Strategic procurement activities are focused on delivering outcomes that are critical to Defence's ability to meet its core objectives. The Project satisfied the conditions for classification as a strategic procurement activity, and thus treatment as a Major Capital Equipment Procurement activity. The risks of program failure were high, and the costs associated with delay were also high. The procurement activity was very complicated, extending across more than 50 individual contracts of varying nature and complexity.

8. The objective of the audit was to undertake a performance audit of the project management environment governing delivery of Defence business information system projects, with specific reference to the Project. Notwithstanding the SDSS financial integrity issues, which are dealt with separately in the annual ANAO Financial Statement audit, this audit addresses the scope of the system being delivered, with specific regard to its ability to meet end user capability requirements.

Key Findings

Approval Management (Chapter 2)

9. The ANAO found that the Project was not managed as a strategic procurement activity, nor was it managed as a Major Capital Equipment acquisition activity3. As was the custom in Defence at the time, it was managed as a Minor Capital Equipment procurement activity. As a result, the procedural guidelines in the Defence Procurement Policy Manual, and the Defence Capital Equipment Procurement Manual (CEPMAN 1) for the inception, approval, management and delivery of a Major Capital Equipment acquisition activity were not followed. Defence guidelines at the time of the Project's initiation stipulated that projects of a strategic nature, of estimated materiality in excess of $20 million, and running for a period in excess of 12 months, should be undertaken as Major Capital Equipment procurement activities, mandating Cabinet approval, as well as prescribed management deliverables and methodologies.

10. The Project was managed as a Minor Capital Equipment acquisition project, following allocation of initial funding to the value of $15.87 million in July 2000 from Support Command Group operating budget funds. The ANAO did not observe that Defence sought, or obtained, Ministerial approval before allocating initial funds to, and then implementing, the Project, despite the July 2000 Equipment Acquisition Strategy estimate of Project costs of $27 million. 4

11. Defence applied to the Department of Finance and Administration (Finance) in mid 2000 to improve SDSS, utilising funds from $40 million allocated within the 2000–01 Defence Portfolio Budget.5 Finance advised that a detailed report was required to provide independent advice, relating to the adequacy of the strategy associated with the upgrade of the SDSS. Finance indicated that the report would be required to justify approval for allocation of the funds sought by Defence. Defence later reported that Finance contended that it would be more cost effective to replace SDSS than to upgrade it. The ANAO found no evidence to confirm that Defence sponsored, or actually provided, the requested report to Finance. Defence subsequently advised that studies associated with the follow-on Project JP 2077 have concluded that migration to a different system would have been even more expensive than the options chosen. The ANAO has not verified these claims given the elapsed time and subsequent decisions taken.

12. Authorisation to initiate the Project was derived from the Defence Executive allocation of operational funds to the Support Commander Australia, who in turn authorised the Defence Joint Logisitics Support Agency (JLSA) to utilise the operating budget to initiate the Project. 6

13. Prior to Project approval in July 2000, the Defence Acquisition & Logistics Review Team applied to the then Minister for Defence in April 2000 for $23 million of funding to implement Project JP 2077, a closely related project with follow-on aims now associated with building upon the achievements of the SDSS Upgrade Project. The request for Project JP 2077 funding was accompanied by a statement of savings amounting to $40 million to be realised by implementing the initiatives for which the funding was sought. Of the initiatives designed to realise the savings, $6 million of the tasks were transferred to the Project,7 which would, according to Defence, have secured $15 million in savings to Defence8. The ANAO has not observed, nor has Defence provided, any evidence of Defence efforts, or impending plans or methodologies to measure the net gain savings offered by the completed, and projected SDSS upgrades. 9

Governance (Chapter 3)

14. At the time the Project was initiated, Defence did not maintain an integrated business information management system perspective with respect to strategic business information system development programs. No overarching architectural guidance from the Enterprise Business Process Owner (EBPO) Domain Chief Information Officer (Domain CIO) nor from the Defence Information Environment Committee (DIEC), was applied with the aim of achieving interoperability with other business information management systems. The latter has long been regarded as good practice.

15. The Project utilised a proprietary management system, and did not report progress utilising standard Defence reporting systems.10 The ANAO concurs with an internal Defence assessment that the Project Board appeared not to adequately supervise the management of internal Defence relationships required to successfully deliver the Project on time, within scope and within budget. The Project Board met twice during 2002.

16. The ANAO found that the Divisional reporting system lacked an effective focus on the progress and delivery of scope within the original baseline schedule and cost allocations. The representation of a GREEN status would indicate that the project is on time, within budget, and delivering the approved scope. An internal Defence Audit Report found that, in the case of this Project, it was never capable of delivering the required scope within the allocated budget and schedule. Nevertheless, the reporting system recorded a GREEN status for consecutive reporting periods on more than one occasion. This included a period of six of the last 12 months of the Project's duration. Further, the estimated cost at completion for the Project increased throughout the life of the Project.

17. The ANAO observes that the processes and reporting requirements across projects being managed in differing Defence organisational environments are not standardised. The management controls over each project thus differ. Project management methodology and reporting requirements are also at variance.

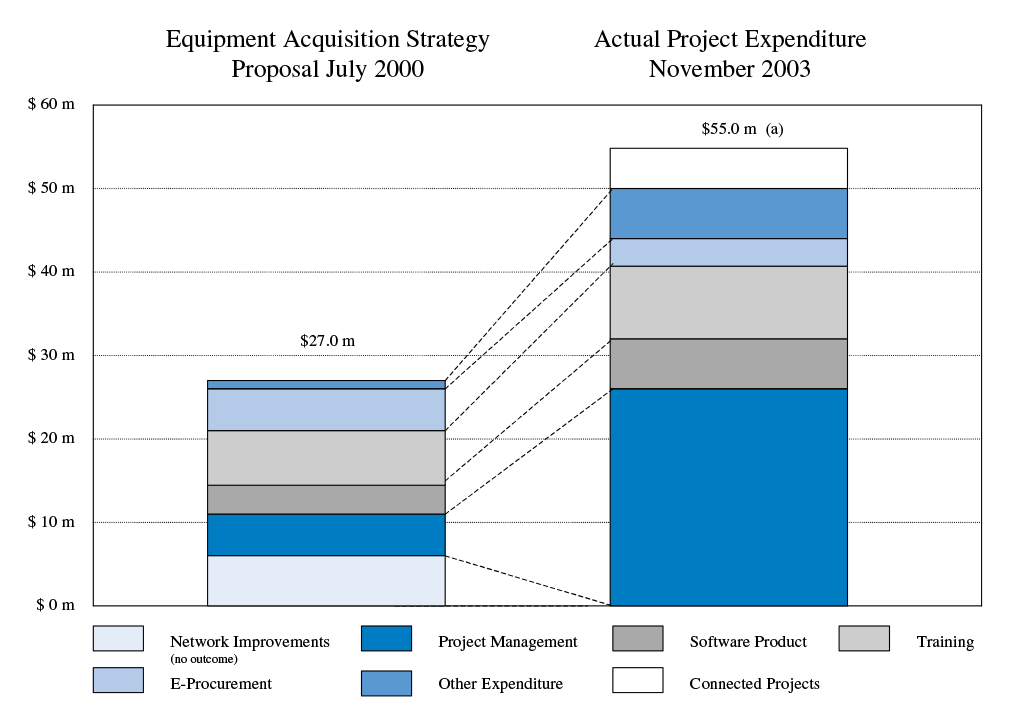

18. The Project Board, and the Project Office were reported by Defence to have not effectively managed mitigation strategies to obviate the occurrence of the risk outcomes.

Project Management (Chapter 4)

19. The Project commenced as a proposal to upgrade the existing operating system upon which the Defence logistics management system was based while, concurrently, upgrading the business rules to roll out a Single Supply Chain Management System, and introducing changes to the financial records of the system to enable it to comply with accrual accounting standards.

20. In the approved Equipment Acquisition Strategy, Defence identified that it did not have the staff to effect project management of the delivery of the required outputs associated with the Project. To that end, the approach approved by Support Command Australia was to outsource a contracted Project Management Organisation (PMO).

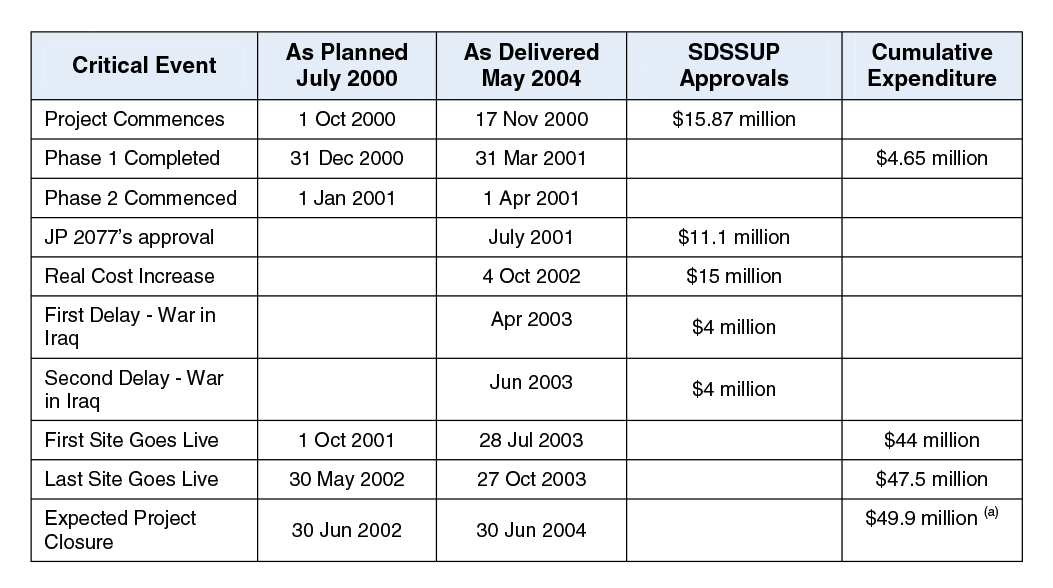

21. The proposed upgrades were defined in a report commissioned by Defence from PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting (PwCC). An Equipment Acquisition Strategy was developed against the PwCC report, which incorporated the report as an attachment. Defence subsequently tendered for project management services to assist with implementing the changes articulated within the report. PwCC won the tender, and was appointed as the PMO. A series of suppliers were contracted by Defence to implement the deliverables required to fulfil the Project's outcomes. 11

22. Management of Phase 1 of the contract was based largely on payments to contractors on the timely delivery of statements of work and was completed at a cost of $4.65 million. IBM Business Consulting Services (IBM BCS) advised the ANAO in June 2004 that Phase 2 of the Project comprised fixed cost deliverables and foundation payments12. The payments, which constituted agreed hourly rates for the provision of specified contractor staff, were periodically negotiated between the PMO and Defence for renewed, monthly, fixed cost deliverables, as specified by the PMO contract.

23. IBM BCS advised the ANAO in June 2004 that:

… the reason that costs for the project exceeded the original budget is not surprising when the following factors are taken into account:

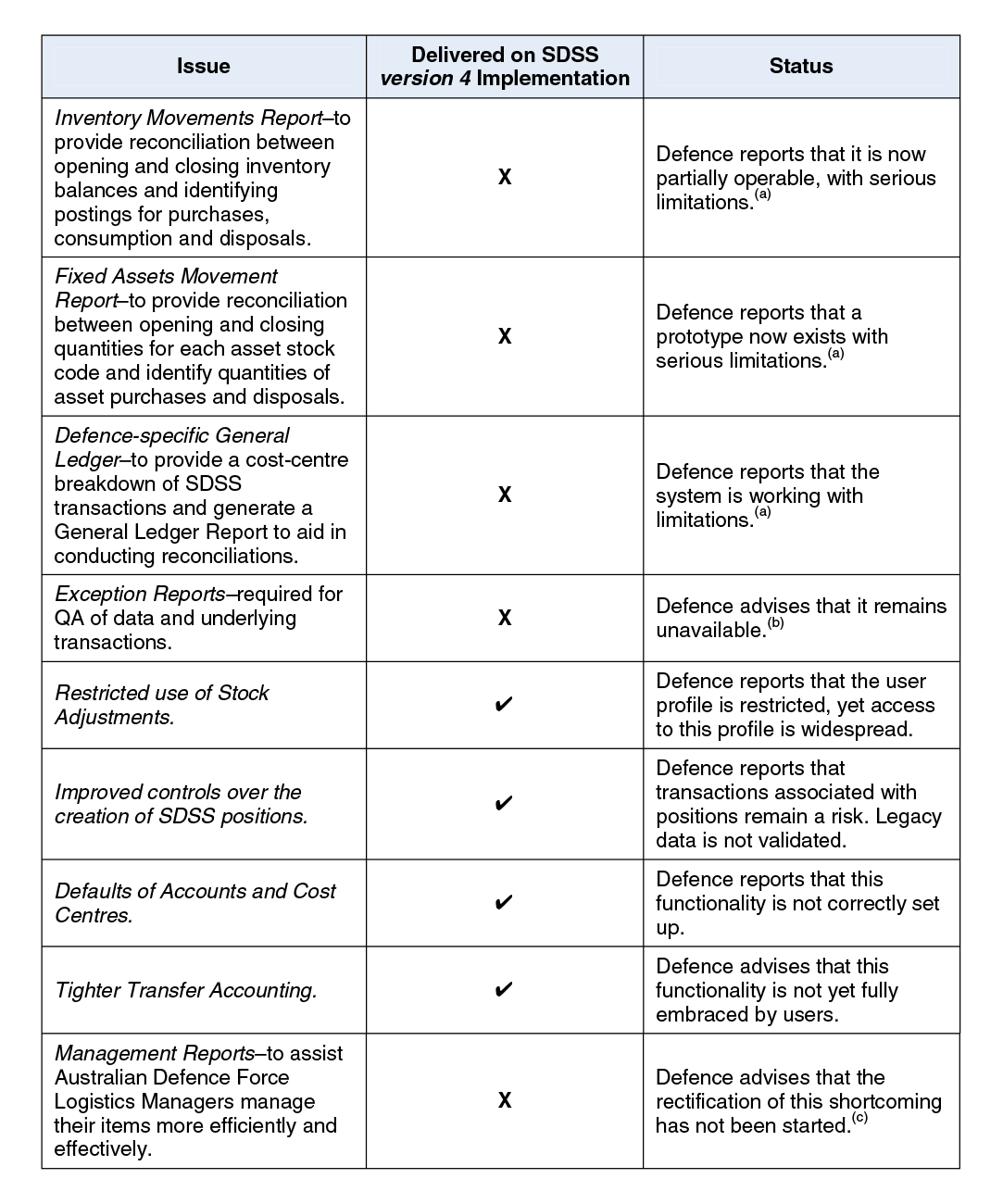

a. The requirement from Defence for the PMO to keep operating for a longer period due to the delays …

b. The PMO being requested to do additional tasks (Contract Deliverable Requirements, CDRs) that were either new work or work to assist Defence meet its own responsibilities in the light of Defence resource shortages.

c. Additional scope being added to the project (eg Whole of Defence e-Procurement, MMM [MIMS Maintenance Module] equipment maintenance) and changes to the scope of existing CDRs.

24. Defence advised the ANAO in July 2004, in response to paragraph 23.c, that:

IBM is quoted as saying the Whole of Defence eProcurement was added to the scope of the project. This is incorrect. A separate project ‘Provision of SDSS eProcurement Tools' was established and managed as a separate project to SDSSUP, and was delivered to plan.

25. Phase 2 of the Project did not achieve the required outcomes expected of it, and exceeded the cost allocated schedule by more than 100 per cent. Figure 1 illustrates that the largest component of the total cost increase was represented by the payments made in respect of Project management, which rose from an estimated $5.2 million to $26.3 million. There were 21 contract amendments to the PMO contract. The initial allocation for network improvements, identified as a $6 million requirement in the Equipment Acquisition Strategy (see Figure 1), was diverted to other requirements within the Project. The performance of the delivered system continues to be adversely impacted by issues demonstrative of poor network performance.

Figure 1: Comparison of forecast and actual SDSSUP expenditure

Note: (a) Total expenditure ($55 million) to November 2003 includes the balances of the e Procurement ($2.4 million) and Training ($2.7 million) contracts supported by funding from other projects.

Source: Defence financial and contract records.

26. Contractual controls associated with enforcing the delivery of products were ineffective. The Project Office did not demonstrate effective control over internal Defence suppliers. Late supply of deliverables from internal Defence suppliers contributed to critical path extensions in schedule, and concomitant cost increases associated with payments to commercial contractors who were, in turn, delayed in their deliverables.

27. Management decisions to redirect allocated resources to cover increases in management expenses eventually contributed to poor network performance, loss of functionality, and loss of system acceptance by end users.

28. The software metric controls associated with product development, while being recorded, were not used as predictive indicators to assess and manage potential delays. The ANAO did not observe an effective form of Cost Schedule Control management being utilised. Scope changes, associated with financial reporting requirements during the course of the Project, added further functionality to the required outputs but with concomitant cost and schedule increases.

Delivery Management and Follow-on Support (Chapter 5)

29. The Project did not deliver the approved scope for which it was funded. Also, the Project did not deliver the approved outcomes within the time allocated. Defence has advised that Project closure is expected to be in June 200413, compared with an original baseline estimate of 30 June 2002 (see Table 1). It also exceeded the approved start up funding by more than $33 million.14

Table 1: Project Event Calendar

Note: (a) Reported expenditure ($49.9 million) does not include the balances of the e Procurement ($2.4 million) and Training ($2.7 million) contracts supported by funding from other projects.

Source: Defence Records.

30. During the Project build phase, the contractual terms used to engage the primary supplier of upgraded code did little to support the timely delivery of the product. Similarly, the contracting methodology applied to the PMO did not provide incentives for efficient project management.

31. From the outset, it is not evident that the Defence Project Office fully engaged key stakeholders who had control over Project inputs, and who would have eventually acted as the acceptance authority, had a fully integrated project/product team approach been implemented.

32. Implementation of training was delayed on two occasions, coinciding with the impacts of the war in Iraq, which cost the Project $8 million. The full cost of training development and delivery exceeded the original estimated cost by 47 per cent. The delivery of training to end users did not account for the full range of training requirements necessary to fully transition the SDSS upgraded system into service. Co-ordination and analysis of end-user training requirements were deficient, and did not meet all end user training needs. The ongoing in-service co-ordination of SDSS training requirements and delivery management would benefit from more centralised control. Defence has not articulated a clear training philosophy to manage the post delivery training requirements for the entire upgraded SDSS user community.

33. As at the completion of this audit, the delivered Project had not achieved many of the key Defence financial and functional reporting requirements associated with operating its logistics systems. A summary of the shortfalls associated with the financial management capability of the upgraded SDSS system, as provided by Defence, is at Table 2.

Table 2: SDSS Financial Requirements Delivery Status: May 2004

Notes: MINCOM advised the ANAO in June 2004 that:

(a) these issues are being addressed in the ‘Get Well' program;

(b) Exception Reports were ruled out of the scope of SDSSUP, they were not specified by the PMO, and MINCOM was not asked to develop them. MINCOM further advised that they are included in the ‘Get Well' program; and

(c) rectification is scheduled to start from July 2004 as an element of the ‘Get Well' program.

Source: Defence correspondence dated May 2004.

34. The ANAO agrees with a Defence report which states that a significant training liability still exists, resulting from inadequacies in the Project, and associated projects. The Defence report also states that the end user community has not accepted that the training provided has met the requirement to impart an adequate understanding of the SDSS version 4 processes and functionality. Defence further reports that the problem associated with training is compounded by the significant number of SDSS operators yet to receive initial SDSS training.

35. The elements that were defined as critical success measures, yet not delivered by the Project being Purchasing, Warehousing and Financial Management, have largely been transferred to Project JP 2077 and an SDSS Get Well Program for delivery at a future date, at additional cost to Defence.

36. Defence advises that the SDSS version 4 Get Well Program has been proposed with a completion date of December 2005. The Get Well Program is expected to attend to infrastructure performance improvements, business process improvements, software defects and financial reporting shortfalls from the current operating budget. Defence further advises that work on data quality will be funded to $0.5 million. A similar amount will be made available for infrastructure performance improvements. For data quality purposes, a business case is being developed for an additional allocation of $6 million. Defence estimates that additional costs associated with infrastructure performance improvements will be of the order of $3.35 million, which is to be drawn from operating budget funds. Defence is proposing to manage the Get Well Program as a series of Minor Projects, as well as utilising ‘in-service' support contracts.

Overall conclusions

37. The ANAO found that the Project has not delivered value for money to Defence. The Project exhibited extensive scope reduction and, based on a scheduled final deliverables being accepted in June 2004, operated with an extended schedule in excess of 200 per cent of the planned schedule. SDSS version 4 was to provide Defence with improved finance functions, tighter controls over data integrity and transaction processing, and improved reconciliation and reporting. The Project has failed to materially deliver many of the outcomes for which it was funded.

38. As at the completion of ANAO fieldwork in April 2004, the initial scope of the Project remains incomplete. Cumulative cost escalations [excluding $5.1 million in contract deliverables from legacy training and e-Procurement projects] have required a further allocation of $34 million to what had originally been approved as a $15.87 million project. By November 2003, the Project had already exceeded its initial approved budget by more than 200 per cent. This excludes further funds being earmarked for the SDSS Get Well Program. Defence has advised the ANAO that the anticipated delivery date for the Get Well Program remediation activity is December 2005.

39. The Project was raised as a Minor Capital Equipment acquisition project from operating funds to provide major systemic changes to the entire Defence logistics management environment.16 This decision was taken irrespective of the Equipment Acquisition Strategy, which estimated the cost associated with implementing the stated upgrade outcomes as being $27 million which would, at the time, have required the Project to be approved by Cabinet, and managed as a Major Capital Equipment procurement activity. Defence governance procedures have recently been strengthened to ensure that all strategic capability procurement exceeding designated limits will be referred for Ministerial consideration.

40. Technical risks, as well as risks associated with scope amendments, were not broken down in terms of their respective scope, schedule and cost impacts in order to be easily understood by members of the Project Board. The organisational risks associated with delivering the Project were not adequately managed. End users remain discontented with the performance of the delivered product, which did not meet 40 per cent of the critical success factors defining successful Project delivery.

41. The contractual construct chosen for the Project was deficient. The decision to retain a contracted PMO, on hourly rates, for a high-risk software development and roll out program during Phase 2 of the Project, proved to be inappropriate, and did not shift adequate risk to the PMO. A large proportion of the costs associated with the delays experienced by the Project were consumed by the PMO17. The PMO had no direct contractual authority over any of the Project suppliers, yet was expected to accept responsibility for the management of deliverables.

42. The delivered system functionality does not satisfy many of the end user expectations. Significantly, the system is ineffective in its ability to manage Defence stock holdings to the extent originally envisaged, and restricts Defence's ability to fully account for them. The system does not adequately alert appropriate Defence logistic management staff that strategically important stock holdings have fallen below levels able to support Defence operational requirements. Reports of this nature are not automatically routed to materiel managers responsible for replacing used stores. Without appropriate workarounds, these shortcomings compromise Defence's ability to assure operational Force Element Groups that the stores, necessary to implement their stated operational requirements, can be delivered, as required, to support specified levels of operational readiness.

Agency Responses

43. Defence agreed with all eight recommendations. Defence advised ANAO that Recommendation No. 1 was agreed for future projects.

44. The Department of Finance and Administration (Finance) advised ANAO, in its response to this audit, that:

The Department of Finance and Administration (Finance) supports the thrust of the Report's recommendations and notes that the Defence Procurement Review of 2003 placed an emphasis on the importance of business information systems and the need to build and maintain these systems.

Finance notes that the “traffic light” reporting noted in Recommendation 2 is but one form of reporting that could be used to evaluate a project's progress. However, any project progress report should include the milestone achievement versus project expenditure achievement of the project to ensure that useful decision-making information is available.

An appropriate upgrade plan and standards for the management information systems are vital for a number of reasons. Finance, for example, relies on the information made available by Defence in producing costings for deployment of the Australian Defence Force overseas. If the systems are unable to accurately capture such information, then the costings risk being compromised.

Footnotes

1 SDSS version 4 was developed with the aim of supporting all supply chain activities at Unit, Formation and Depot level within the Services and the regional and national levels within the DMO. The activities include: warehousing, issue and receipting, asset/repairable item tracking, purchasing, cataloguing, foreign military sales, stocktaking and disposal, repair of inventory, and maintenance of equipment for Army.

2 Contributory projects to the successful delivery of the upgraded SDSS include, but are not limited to: project JP 126 Phase 2A (the roll out of SDSS (version 3) to Army); the Common e-Business Infrastructure (CeBI) project; the SDSS Data Quality project; and the SDSS/ROMAN Interface project.

3 Minor Capital Equipment procurement activities are treated very differently in Defence from those classified as Major Equipment Procurement activities. Minor Projects, as they are known, are characteristically less than $20 million in cost, and are managed with far less rigour than are Major Capital Equipment Projects. Major Capital Equipment Projects are those estimated to cost in excess of $20 million, and require Ministerial approval for implementation. Senior Defence staff have advised that Defence did not manage Business Information System software projects as anything other than Minor Projects.

4 Government requirements in 2000 stipulated that project approval submissions between $8 million and $20 million require the concurrence of the Ministers for Defence and Finance. The guidelines also stipulate that submissions above $20 million require Cabinet approval.

5 $40 million was made available within the 2000–01 Defence portfolio budget for expenditure on corporate management systems. The program established to manage the those corporate improvements later became known as the Defence Management System Improvement Program.

6 Advice from the Joint Logistics Command is that the Defence Executive provided approval for the use of Support Command operational funds to implement the SDSS Project. The ANAO was unable to locate the approval from Defence Executive minutes made available from Defence.

7 Both the implementation of a Common Supply System, and the development of a Central Catalogue were transferred to the SDSS Upgrade Project. The costs associated with undertaking these activities are quoted as $5 million and $ 1 million respectively. The savings that were supposed to have been realised, maturing in 2002–03, were $10 million and $5 million respectively.

8 Of the $6 million anticipated cost, the funds transferred only amounted to $5 million.

9 A further $6 million was transferred from Project JP 2077 to fund improvements to the logistics computer network.

10 Defence advise that the PROMAN project management was utilised by the DMO and its predecessors to report and manage Minor Projects during the period the SDSS Upgrade Project was being undertaken.

11 The PMO role was novated to IBM Business Consulting Services (IBM BCS) in November 2002 to coincide with the IBM acquisition of PwCC.

12 In July 2004, Defence advised the ANAO that: the term ‘foundation payments' is not one used in Defence contracting and it should either be replaced with the original ‘time and material' wording, or have a clear definition included.

13 The ANAO noted that the Project Office had disbanded by early 2004. This, in effect, constituted effective Project closure. The Project funding line was being held open by Management Information Systems Division (MISD) to cater for outstanding invoice and follow-up actions associated with delivering financial reporting functionality elements of the system at additional costs over and above $49.9 million. The estimated costs associated with delivering the required financial reporting functionality is between $0.4 million and $0.7 million.

14 The original Equipment Acquisition Strategy designated a requirement to expend $27 million to deliver the required Project outcomes. The original budget available, however, was $15.87 million, made available from operational funding. There was no specific Defence Budget Appropriation set aside for SDSS.

15 Dimension Data, the contracted training deliverers, advised the ANAO in June 2004 that a number of items diluted the efficacy of the training regime and overall project outcome for Defence. Dimension Data cited these to include; subcontractor delays; financial and reporting problems; system ineffectiveness, lack of logistics processes; tri service divergence; and failure to use the DSCM (Defence Supply Chain Manual). Dimension Data wishes it to be noted that none of these items were under their control or management.

16 Defence has advised that it characteristically utilised operating funding to implement Defence business information system software applications within individual Defence groups at the time the SDSS Upgrade Project was initiated.

17 PwC advised the ANAO in June 2004 that the characterisation of the contract as one for time and materials is not accepted. Such a characterisation ignores the fact that the contract specified a number of fixed price contract deliverables (which were capped on a monthly basis where those deliverables were calculated on hourly rates).