Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the National Solar Schools Program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and management of the National Solar Schools Program (NSSP), including demonstrated progress towards achieving the program's objectives.

Summary

Introduction

1. The National Solar Schools Program (NSSP) offers primary and secondary schools the opportunity to apply for grants of up to $50 000 to install solar and other renewable power systems, solar hot water systems, rainwater tanks and a range of energy efficiency measures. The objectives of the NSSP are to:

- allow schools to:

- generate their own electricity from renewable sources;

- improve their energy efficiency and reduce their energy consumption;

- adapt to climate change by making use of rainwater collected from school roofs;

- provide educational benefits for school students and their communities; and

- support the growth of the renewable energy industry.

2. The establishment of the NSSP followed a commitment made by the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in the lead up to the November 2007 Federal election.1 Specifically, the ALP had made a commitment to establish a National Solar Schools Plan to make every Australian school, which equated to some 9500 schools, a solar school within eight years. The commitment was characterised as generating jobs and investment in Australia’s sustainable industries and trades, with significant educational benefits for students and communities.

3. Following the election, funding for the program of $480.6 million over eight years (2007–08 to 2014–15) was provided in the 2008–09 Budget.

NSSP demand and program funding

4. In June 2008, guidelines for the NSSP were approved by the then Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts. Generally, schools were eligible for grants of up to $50 000 against a list of eligible items for installation. The program opened to applicants on 1 July 2008. The NSSP operated between this date and October 2009 as a demand-driven grants program.2

5. When the NSSP was established, a mechanism such as application rounds was not put in place to manage demand for program funds in-line with the program’s annual funding. This situation hindered the management of demand for NSSP funding. Further, possible funding duplication with other Australian Government programs later emerged as an issue.

6. As a result of higher than expected demand3, school claims on the program were suspended in October 2009, after fifteen months of operation. Following the suspension of the NSSP and its administrative transfer from the then Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) to the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE) in March 2010, a number of changes were put in place via a new set of program guidelines (July 2010). The changes included:

- funding to be capped each financial year and annual application rounds to be held;

- applications to be assessed on a merit basis using predetermined criteria, with schools required to demonstrate value for money, environmental and educational benefits in their applications; and

- to address potential duplication of funding sources4, schools that had been approved to receive funding for solar power systems under any other Australian Government program from 1 July 2008 would only be eligible for funding of up to $15 000.5

7. Under the NSSP, each year’s total funding budget is allocated between government and non-government school sectors based on the proportion of eligible schools in each sector. Funding for government schools and non-government schools in each state and territory is then allocated on a similar proportional basis, taking into account grants already awarded to schools in each state and territory. The intention is that each state and territory (government and non-government sectors) will receive a proportional share of funding over the life of the program.

8. Under the new program guidelines, applications for the first competitive round were open between 15 July and 20 August 2010. More than 2000 schools submitted applications totalling $94 million for the $51.8 million in funding that was available. Applications were assessed against the three published assessment criteria of value for money (weighted at 45 per cent), environmental benefit (with a weighting of 40 per cent) and educational benefit (weighted at 15 per cent). A total of 1226 projects were approved by the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, with the successful projects announced in December 2010.

Program status

9. The May 2011 Budget announced a number of changes to the program, including that the NSSP would finish two years earlier than originally planned (30 June 2013) with savings of $156.4 million being redirected to support other Government priorities. This left a remainder of $49.8 million available for the 2011–12 and 2012–13 funding rounds. As a result of these changes, DCCEE anticipates that over the life of the program only about 60 per cent of all primary and secondary schools will receive an NSSP grant.

10. Applications for the second competitive funding round were open between 1 August and 30 September 2011. Nearly 2000 schools submitted applications totalling $64 million for the $25 million in funding that was available. Under revised administrative arrangements that states and territories had formally agreed to by November 2011 and reflected in the National Partnership Agreement on the National Solar Schools Program (NPA), state and territory education authorities would apply the program assessment criteria and assessment methodology to decide which government schools in their jurisdiction would receive grants under the NSSP.6 Applications from non-government schools continued to be assessed by DCCEE.

11. Applications were assessed by the states (government schools) and DCCEE (non-government schools) against the same three criteria as applied in the first round (see paragraph 8), as well as whether they were located in a remote or low socio-economic area (to allow the remaining program funding to be directed to schools most in need). A total of 784 projects were approved for the 2011–12 funding round, with the successful projects announced in January 2012.

12. The 2012–13 funding round is the final round for schools to apply for a grant. Funding of $24.8 million is available7, with applications opening on 13 February 2012 and closing on 18 May 2012. The successful applications are expected to be announced in July or August 2012.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

13. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and management of the NSSP, including demonstrated progress towards achieving the program’s objectives.

14. The audit assessed the program’s establishment, implementation and administration against relevant policy and legislative requirements for the expenditure of public money8 and the seven key principles for grants administration established by the Australian Government and set out in the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs).9 Emphasis was also given to examining whether the NSSP was achieving its stated objectives and providing value for public money. The focus of the audit analysis was on the conduct of the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds.

Overall conclusion

15. The NSSP is intended to assist schools to take practical action on climate change through grants to install solar and other renewable power systems, solar hot water systems, rainwater tanks and a range of energy efficiency measures. The program objectives also include providing educational benefits for school students and their communities, and supporting the growth of the renewable energy industry. The program is well advanced in its implementation, with over 4600 projects approved for funding, of which more than half have been reported as completed. The last competitive funding round for the program is currently underway.

16. Whilst there are some shortcomings in the design of the program and the available data, early indications are that overall the program has:

- assisted schools to generate their own electricity from renewable sources and improve their energy efficiency, although the energy abatement achieved has come at a considerable cost10;

- contributed to schools making use of rainwater collected from school roofs;

- assisted to increase student awareness of the need to be more energy efficient and to conserve water; and

- made a small contribution to the growth of the renewable energy industry.11

17. When it was established in 2008, the NSSP operated as a demand-driven grant program but its operations were suspended in October 2009, as a result of over-subscription. Since 2010–11, the NSSP has operated as competitive, merit-based grants program. This approach is consistent with the preference expressed in the CGGs for competitive, merit-based selection processes based upon clearly defined selection criteria to be used in Commonwealth grants programs. The risk of over-subscription was also effectively addressed in the redesign of the program, through an annual cap on program funding.

18. Overall, the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds were well designed and effectively implemented. Of particular note is that:

- generally clear and effective guidance was provided to schools and other stakeholders on the redesigned NSSP and its operation;

- the program eligibility requirements and assessment criteria have been published and applied. The nominated assessment criteria were directed at the identification of those applications that both represented value for money and could be expected to best contribute to the achievement of the program objectives (within the limits of the amount of funding allocated to the government and non-government school sectors in each state);

- weightings of the assessment criteria were also published, thereby providing potential applicants with a clear understanding of the relative importance to the program of the factors that would be taken into account in selecting the successful applications;

- a robust and appropriately documented assessment process was implemented. A key aspect of the selection process was that eligible applications were clearly scored against each assessment criteria, with the aggregate assessment score12 used to rank applications. This ranking was then used to determine (within the funding allocated to the government and non-government school sectors in each state) which applications would be successful; and

- clear funding recommendations were provided by DCCEE to the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, with the decision-maker accepting the department’s recommendations.

19. Nevertheless, certain aspects of the design and implementation of the NSSP could have been improved. Firstly, while guidelines applying to the competitive application rounds have been developed, updated and published in a timely manner, there were some shortcomings in their content, as follows:

- important information concerning the assessment methodology was included in an administrative arrangements document rather than the program guidelines. This approach does not sit comfortably with the single reference approach for program guidelines advised to agencies in the CGGs.13 However, for the NSSP, the associated risks were mitigated by DCCEE also publishing the associated administrative arrangements document. Nevertheless, as outlined in a cross-portfolio ANAO audit on the development and approval of grant program guidelines14, where practical, agencies should develop a single program guidelines document that represents the reference source for guidance on the grant selection process, including the relevant threshold and assessment criteria, and how they will be applied in the selection process;

- the revised program guidelines that applied to the 2011–12 funding round (and the 2012–13 funding round currently underway) indicated that ‘additional weighting’ would be given to applications from schools located in remote or low socio-economic areas. This approach did not provide stakeholders with sufficient clarity about what was, in effect, a fourth assessment criteria and the importance of this criterion to the assessment scoring15; and

- the guidelines did not indicate to schools that the scoring of applications against the value for money criterion would favour applications for the four eligible items most commonly submitted for funding over other categories of eligible items.16

20. The more significant issue identified by the audit relates to the interrelationship between the scoring of individual applications and the framework in which decisions were then made about which applications would receive funding. The scoring approach was designed and implemented to identify the individual merits of applications against the assessment criteria and, therefore, the extent to which each application would contribute towards the program objectives.17 Applications were then ranked on the basis of their assessment score with funding awarded in each state and sector based on the rankings until the annual allocation for each state and sector was exhausted.

21. A range of variables affect the score, including the amount of funding that is sought. Applications seeking the maximum available funding are better able to achieve a higher score as they can achieve economies of scale (and therefore achieve a higher score against the value for money criterion) and larger environmental outcomes (and therefore achieve a higher score against the environmental benefits criterion).18 In addition, higher scores are achieved where a school plans to use the project to demonstrate energy efficiency benefits.19

22. It is well recognised that the assumption underlying the production of an aggregate score from a numeric scale is that a higher score indicates more satisfaction of the criteria than a lower score.20 It is for this reason that aggregate scores are commonly used to rank competing applications. It also necessarily follows that applications that receive a low aggregate score need to be carefully considered in terms the extent to which they can be expected to contribute towards the program objectives, and satisfy the statutory requirement that public money only be approved where the proposed expenditure represents an efficient, effective and economical use of resources.21

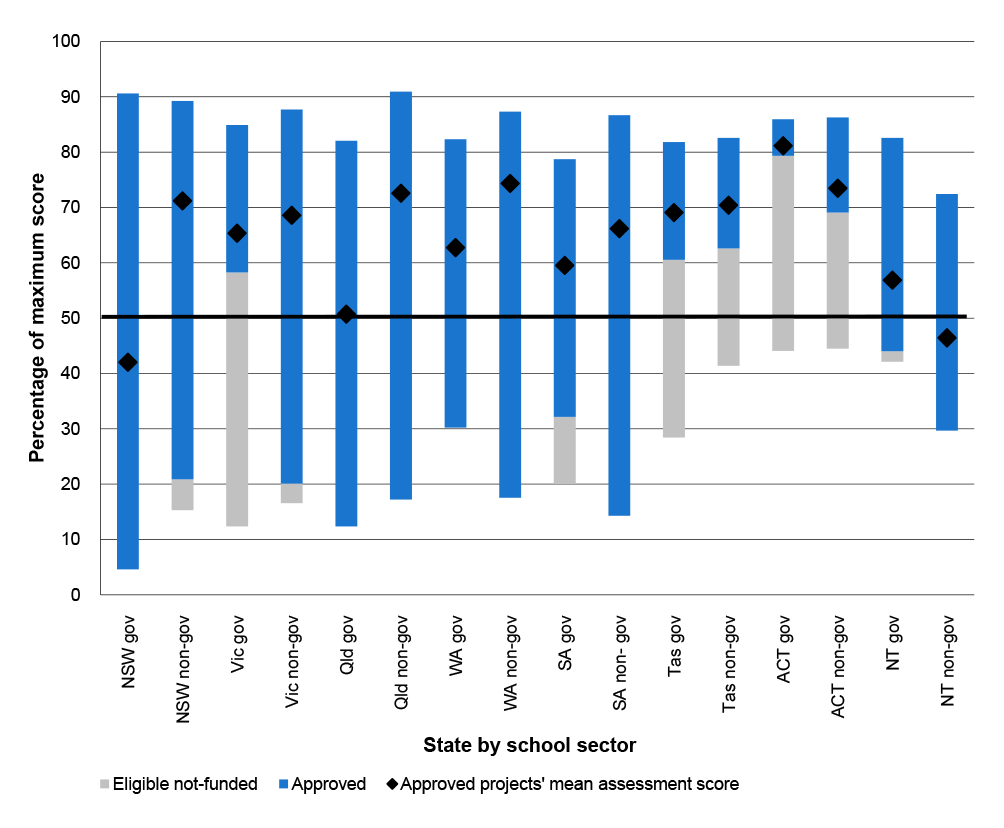

23. However, neither the design of the program22 nor DCCEE’s advice to the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency on individual funding round outcomes addressed how eligible applications that scored poorly against the assessment criteria provided a sufficient contribution towards the program objectives and could be seen to represent an efficient, effective and economical use of public money.23 As a result, and particularly in respect to the 2010–11 funding round (see Figure S 1), a number of applications that did not receive a high score against the assessment criteria have been approved for funding. Axiomatically, awarding funding to applications that have achieved a relatively low score against the assessment criteria has an adverse impact on the extent to which a program is able to achieve its objectives.

Figure S 1 Approved and eligible-not funded application score ranges by state and sector in the 2010–11 funding round

Source: ANAO analysis of DCCEE data.

Note: In a number of state/sectors there are approved projects that have a lower assessment score than the highest assessment score for eligible-not funded projects (NSW government — 85 projects; NSW non-government — seven projects; Vic non-government — six projects; Qld non-government — two projects; WA non-government — three projects; SA government — 16 projects; and SA non-government — three projects). This is in part due to a separate 2010–11 funding allocation set aside for schools that had been approved for funding for a solar power system under any other Australian Government program from 1 July 2008. In this case, eligible NSSP project funding was generally up to $15 000. For the purposes of clarity in the above figure, the lowest approved assessment score is presented, although there may be eligible-not funded project assessment scores above this approved project score.

24. Although the NSSP is nearing completion, DCCEE administers a number of other grant programs.24 In this context, ANAO has made two recommendations. The first relates to ensuring the program guidelines cover all the important aspects of the application assessment process. The second relates to the establishment of clear links between the assessment of individual applications against the published criteria, an overall assessment as to whether each proposed grant represents an efficient, effective and economical use of public money, and the resulting recommendation to decision-makers about which applications should therefore be awarded funding.

Key findings by chapter

Program Oversight and Design (Chapter 2)

25. As part of DCCEE’s program governance framework, a range of key governance documentation has been developed for the NSSP. In addition, advice on program performance is provided as part of monthly reporting on solar programs to the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency and Minister for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. Effective program oversight has been further promoted through the conduct of a comprehensive interim evaluation of the extent to which the NSSP has achieved its objectives to date.25

26. Program objectives were developed when the NSSP was first established as a demand-driven grant program. Significant work was undertaken to redesign and implement the changes to move the program from a demand-driven arrangement to a competitive, merit-based selection process, although the program objectives were unchanged.

27. To address the matter of over-subscription that led to the demand-driven NSSP being suspended, the redesigned program involved an annual cap on program funding with funding to be awarded to those applications on the basis of merit. This has proven to be an effective response.

28. In regard other program redesign features, each year’s total funding budget is allocated between states and territories based on the proportion of eligible schools in each sector. Funding for government schools and non-government schools in each state and territory is then allocated on a similar proportional basis, taking into account grants already awarded to schools in each state and territory. The intention was that each state and territory (and government and non-government sectors) will receive a proportional share of funding over the life of the program.

29. Together with an associated administrative arrangements document that has also been published, the July 2010 published program guidelines provided generally clear and effective guidance to schools and other stakeholders on the redesigned NSSP and its operation. The program guidelines were updated and re-published in July 2011 to reflect further changes to the design and operation of the program. A further version of the separate (but also published) administrative arrangements document was released at the same time. However, including important program information in a document other than the program guidelines does not sit comfortably with the CGGs.26 In this respect, as outlined in a cross-portfolio ANAO audit on the development and approval of grant program guidelines27:

- where practical, agencies should seek to develop a single program guidelines document that represents the reference source for guidance on the grant selection process, including the relevant threshold and assessment criteria, and how they will be applied in the selection process; or

- where more than one document is produced, and each outlines important aspects of the grant selection process, it is important that agencies recognise that collectively, all these documents constitute the program guidelines for the purposes of the CGGs and, accordingly, should collectively be subject to the grant program approval requirements and made available to stakeholders.

Application Assessment (Chapter 3)

30. Overall, the assessment approach for the NSSP was consistent with the preference expressed in the CGGs for competitive, merit-based selection processes based upon clearly defined selection criteria to be used in Commonwealth grants programs.28

31. The program guidelines outlined the program eligibility requirements. Together with an associated administrative arrangements document that was also published, the guidelines also outlined that three assessment criteria would be applied. Each eligible application was to be scored with the aggregate score against all criteria to be used to rank eligible applications. Both the guidelines and the administrative arrangements document outlined that this merit-based, competitive assessment process would be used to determine which applications best met the assessment criteria and would be offered funding (within each state and sector).

32. Both the 2010 and 2011 program guidelines stated that there were three assessment criteria: value for money; environmental benefit; and educational benefit. The nominated assessment criteria were directed at the identification of those applications that both represented value for money and could be expected to best contribute to the achievement of the program objectives (within the limits of the amount of funding allocated to the government and non-government school sectors in each state). This was further aided by the department publishing, through the administrative arrangements document, weightings for each of the assessment criteria, thereby providing potential applicants with a clear understanding of the relative importance to the program of the factors that will be taken into account in selecting the successful applications.

33. The inclusion of a criterion for value for money29 demonstrated the benefits of administering agencies explicitly considering this matter in the assessment of applications to grant programs.30 In this respect, a noteworthy feature of scoring against the value for money criterion was the considerably better performance by non-government schools compared with government schools.31 This had a significant effect on the 2011–12 funding round outcomes in the New South Wales government sector (the state with the largest allocation of funding in that year) where nearly half of the successful applications would not have been awarded funding had value for money not been included as an assessment criterion. In other words, the assessment process favoured those applications that had demonstrated better value for money. However, the published program materials did not inform schools that applications for other than the four most common eligible items32 applied for by schools were unable to achieve a high score against this criterion.

34. A significant change was made to the assessment criteria for the 2011–12 and 2012–13 funding rounds. Specifically, the guidelines were revised to state that, in selecting the successful applications, additional weighting would be given to applications from schools located in remote or low socio-economic areas so as to allow remaining funding to be directed to schools most in need. However, the extent of this weighting was not made clear in any of the published material. The approach taken meant that there were four assessment criteria used in the 2011–12 funding round examined by ANAO (the published program guidelines had continued to state that there were three criteria). A school’s remoteness or low socio-economic status was the third most heavily weighted criterion (higher than educational benefit) with this relatively heavy weighting having a reasonably significant impact on the selection of successful applications. Further, given the nature of this criterion and the scoring approach adopted, the impact it had on the selection of successful applications was greater than any of the other criteria.

35. For the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds examined by ANAO, a robust and appropriately documented assessment process was implemented. In this respect, school applications were assessed in accordance with the published program guidelines, the published administrative arrangements document and internal departmental scoring procedures.33

Decision-making and Funding Distribution (Chapter 4)

36. Decision-making arrangements for the NSSP have been clearly communicated to schools and other stakeholders through the published program documentation. Specifically, the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency approved individual grant applications for both government and non-government school applications in the 2010–11 funding round and non-government school applications in the 2011–12 funding round. Government school applications to the 2011–12 funding round were approved by state government officials, in line with the devolved assessment and decision-making arrangements reflected in the NPA finalised in November 2011.

37. The assessment briefings provided by DCCEE to the Parliamentary Secretary in respect to government and non-government applications to the 2010–11 funding round and non-government applications to the 2011–12 funding round included a clear recommendation that the Minister award funding to projects listed in attachments as recommended. Those attachments ranked each eligible and recommended project in terms of its overall assessment score.34 Greater detail on the assessment process undertaken was included in a separate detailed attachment to each brief (in the form of an assessment report for the round). In addition, specific mention was made of the requirements of the FMA Act.

38. In addition to addressing the requirements of the published program guidelines including an assessment against the published assessment criteria, grants decision-making arrangements are required to be conducted in accordance with the statutory framework governing the expenditure of public money. Of particular importance in this regard is the FMA Regulation 9 requirement that funding not be approved unless the approver is satisfied, after undertaking reasonable inquiries, that giving effect to the spending proposal would be an efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of Commonwealth resources that is consistent with the policies of the Commonwealth.

39. In the context of the NSSP, the aggregate assessment score of each application outlined the extent to which the application met the published assessment criteria and therefore also provided a key input to decide whether the application represented an efficient, effective and economical use of Commonwealth resources.35 In this context, the clear and transparent scoring of eligible NSSP applications through the application of predetermined and weighted assessment criteria together with a well documented assessment methodology provided a sound basis for compliance with the requirements of FMA Regulation 9. In particular, applications assessed as scoring highly against the assessment criteria demonstrably represented, in the terms of the published program guidelines, an efficient, effective and economical use of public money. However, neither the design of the program nor DCCEE’s advice to the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency on funding round outcomes addressed how eligible applications that scored poorly against the assessment criteria could be seen to represent an efficient and effective use of public money (in terms of FMA Regulation 9).

40. Instead, funding has been awarded to eligible grants in each state/sector on the basis of the assessment rankings (from highest to lowest) up to the limit of the funding available in that state/sector for the year, but with no minimum score specified that an application needed to meet. Consequently, a significant number of applications were approved for funding in the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds notwithstanding that the application received a low overall score against the assessment criteria. In this context, there was no recognition in advice to government on program design, or in departmental advice on individual funding round outcomes, of the likely reduced level of achievement against the program objectives that could be expected to result from the awarding of funding to applications that had achieved low scores against the assessment criteria.

Progress Towards Program Objectives (Chapter 5)

41. The NSSP is well advanced in its implementation, with over 4600 projects approved for funding of which more than half have been reported as completed. Nevertheless, there have been some delays with the commencement and completion of projects, reflecting a delay in the finalisation of the NPA to cover funding for government schools, and delays with the finalisation of acquittals for some projects.

42. While there are standards and state/territory regulation applying to the solar power installation industry, an area identified as high risk by DCCEE has been the likelihood of solar power systems installed under the NSSP failing to comply with the program guidelines and meet relevant safety requirements. To date, the outcomes from solar power safety inspections show that the proportion of non-compliant, potentially hazardous systems under the NSSP is almost twice the level of non-compliant, potentially hazardous systems for DCCEE’s solar inspection program as a whole. In briefing the Minister for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency in late 2011, DCCEE outlined a range of existing and additional measures to address the high levels of non-compliant, potentially hazardous systems installed. At the time of this report, data on the impact of these measures was not available.

43. Although not a program objective, a key consideration in the selection of successful applications was the assessment of the value for money likely to be provided by candidate projects. This approach was consistent with the CGGs, which outline an expectation that value for money will be a core consideration in determining funding recipients under a grant program. Analysis undertaken by ANAO as part of this audit of the major cost items funded under the program, as well as analysis undertaken by the consultants engaged to perform the interim program evaluation, indicates that the costs of installed items are generally consistent with industry benchmarks and trends. In addition, in general the cost of similar projects in government schools and non-government schools has been comparable.36

44. Four of the five elements of the program objective related to environmental benefits, and ‘environmental benefits’ was accorded significant weighting in the assessment criteria advised to schools in the published program documentation. In this context, while there are some shortcomings in the available data, indications are that the program has contributed to schools: generating their own electricity from renewable sources; improving their energy efficiency; and making use of rainwater collected from school roofs. The program has also made a small contribution to the growth of the renewable energy industry.37

45. Of particular note in respect to environmental benefits is that DCCEE has estimated the cumulative abatement effect of NSSP photovoltaic installations at 0.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (t CO2-e) over the assumed 15-year lifetime of the installed systems. This is a significant figure, as it is more than one per cent of the abatement to be delivered by the Australian Government’s Renewable Energy Target by 2020. However, the resource cost of the estimated abatement is considerable, being in the order of $284 per t CO2-e. In addition to the inherent limitations of such estimates, due to some shortcomings with installation work38—that DCCEE is aware of and is responding to—the estimate is likely to overstate the level of abatement achieved and, therefore, understate the cost of the abatement that has been achieved.

46. The program objective also outlines that the NSSP should allow schools to provide educational benefits for school students and their communities. The focus of the program against this part of the objective has centred on creating greater awareness and/or understanding of renewable energy and energy efficiency among students and their community. Maximising the educational benefits from funded projects has been impeded by some system installation issues and variations in the extent to which schools use data from solar power systems in their resource materials/learning plans. Nevertheless, the available data indicates that, as a result of the NSSP and other environmental sustainability initiatives, schools consider that their students have a greater awareness of the need to be more energy efficient and to conserve water. However, to date, there is no data available on the extent to which any increased awareness and understanding has been translated into behavioural change.

Summary of agency response

47. The proposed audit report or relevant extracts were provided to DCCEE, the Department of Finance and Deregulation and the Department of the Treasury for comment, with formal comments provided by DCCEE, as set out below.

The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (the Department) welcomes this review of the National Solar Schools Program (NSSP) and that the report recognises that overall the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds of the NSSP were well designed and effectively implemented. This included that there was clear and effective guidance provided to schools and other stakeholders; the program eligibility requirements and assessment criteria were published and applied; and a robust and appropriately documented assessment process was implemented.

The Department agrees with the two recommendations made in the audit report.

Recommendation 1 seeks refinements to the content of future program guidelines. For future programs, the Department will look to enhance program guidelines, paying particular attention to the matters referred to by the ANAO. Recommendation 2 focuses on clearly identifying, in program documentation advice to decision-makers, the relationship between the application scores and the assessment of proposals with respect to efficient, effective and economical use of public money. In regard to the NSSP, the briefing material to the Parliamentary Secretary for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency will in future more clearly explain the scoring process and checks undertaken to provide assurance that all applications, including those with a low score, are a proper use of Commonwealth funds.

The Department is also satisfied that all funding paid represents an efficient, effective and economical use of public money. Analysis and checks performed on individual projects will in future be summarised into a single report to strengthen the documentation and support clearer advice to decision-makers.

Footnotes

[1] The National Solar Schools Plan was one of a number of ALP election commitments in the area of climate change. Other program commitments included: rebates for household solar panels; rebates for solar hot water; rebates for rainwater tanks and grey water recycling; rebates to help landlords install energy-efficient insulation in rental homes; and low interest Green Loans to help families invest in solar and practical water and energy savings devices.

[2] As outlined in ANAO Better Practice Guide, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration, Canberra, June 2010 (referred to in this audit report as ANAO’s Better Practice Guide), an early and important consideration in the design of a grant program is establishing how to structure the process by which potential funding recipients will be able to access the program. In this context, a demand-driven process involves applications that satisfy stated eligibility criteria receiving funding, up to the limit of available appropriations and subject to revision, suspension or abolition of the program. See further discussion in ANAO’s Better Practice Guide, pp. 44–46.

[3] ANAO’s Better Practice Guide outlines that an ‘important consideration in establishing demand-driven programs is the potential for the program to become oversubscribed. This may result in the program needing to be closed to further applications earlier than originally planned, unless additional funding is made available. It is important that the potential for this situation to arise is assessed in the program’s design phase’. See further at p. 64.

[4] In particular, the Building the Education Revolution program permitted funds to be used for items such as solar power systems, which were also covered by the NSSP. The administration of the largest component of the Building the Education Revolution program was examined in ANAO Audit Report No. 33, 2009–10, Building the Education Revolution—Primary Schools for the 21st Century, Canberra, 5 May 2010.

[5] Senator the Hon Penny Wong, Minister for Climate Change, Energy Efficiency and Water, National Solar Schools Program Re-Opens, Media Release, 14 July 2010.

[6] The NPA also specifies the indicative annual funding allocation to each state and territory. As a result of the NPA, from November 2011 payments made to states and territories under the NSSP are no longer subject to Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (see further at paragraphs 4.10 to 4.21).

[7] This includes $200 000 that has been retained to cover the cost of any successful appeals against funding decisions. Once the appeals process is complete this remaining contingency funding will be allocated.

[8] Commonwealth grant programs involve the expenditure of public money and thus are subject to applicable financial management legislation. Specifically, the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) provides a framework for the proper management of public money and public property which includes requirements governing the process by which decisions are made about whether public money should be spent on individual grants, including those made under the NSSP.

[9] Department of Finance and Deregulation, Commonwealth Grant Guidelines―Policies and Principles for Grants Administration, Financial Management Guidance No. 23, Canberra, July 2009 (referred to in this report as Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs)). The seven key principles are: (1) Robust planning and design; (2) An outcomes orientation; (3) Proportionality; (4) Collaboration and partnership; (5) Governance and accountability; (6) Probity and transparency; and (7) Achieving value with public money (at p. 14).

[10] Estimated by DCCEE to be in the order of $284 per tonne.

[11] These program achievements have also been highlighted in an interim evaluation of the NSSP conducted by DCCEE.

[12] Eligible applications were scored against each criterion, and an overall score allocated (out of a maximum of 1000 in respect to the 2010–11 funding round, and out of a maximum of 130 in respect to the 2011–12 funding round). Eligible applications were then ranked in each state and sector on the basis of their overall assessment score.

[13] Commonwealth Grant Guidelines, p. 22.

[14] See further in ANAO Audit Report No.36 2011–12, Development and Approval of Grant Program Guidelines, Canberra, 30 May 2012, pp. 88–89.

[15] The scoring approach adopted meant that there were now four rather than three assessment criteria, with a school’s remoteness or low socio-economic status being the third most heavily rated criterion. Further, given the nature of this criterion and the scoring approach adopted, the impact it had on the selection of successful applications was more significant than any one of the other criteria.

[16] The four most commonly eligible items submitted for funding involve solar power systems, solar/heat pump hot water systems, rainwater tanks and energy efficient lighting. These items are present in approximately 97 per cent of applications for the 2010–11 and 2011–12 funding rounds.

[17] In this respect, both the program guidelines and the related administrative arrangements document stated that the assessment process would be used to determine which applications best meet the criteria. This is consistent with selection criteria forming the key link between a program’s stated objectives and the outcomes that are subsequently achieved from the funding provided. See further in ANAO Better Practice Guide, pp. 61–62.

[18] Collectively, these two criteria comprised 85 per cent of the aggregate score that could be achieved in the 2010–11 funding round and 65 per cent of the aggregate score that could be achieved in the 2011–12 funding round. Other factors that affect scoring against these two criteria include the quality, type and size of the product to be installed, its location and the competitiveness of the pricing offered by potential suppliers.

[19] In addition, commencing with the 2011–12 funding round, additional scoring points are awarded where a school is located in a remote or low socio-economic area.

[20] ANAO Better Practice Guide, pp. 75–76. Similar guidance was included in the 2002 version of ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide.

[21] Regulation 9 of the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) requires that funding not be approved unless the approver is satisfied, after undertaking reasonable inquiries, that giving effect to the spending proposal would be an efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of Commonwealth resources that is consistent with the policies of the Commonwealth. For grants programs, the key policies of the Commonwealth are the CGGs and the guidelines for the particular program.

[22] While the program’s 2010 redesigned funding and delivery model was an effective way to manage demands upon the program, the adoption of 16 funding pools (comprising a government and non-government funding pool in each jurisdiction) as the method to allocate funding available for competitive application meant that where a limited number of applications were received compared to the size of the funding pool, low aggregate scores in terms of the assessment criteria could be approved for funding. Most notably, this occurred in situations where there were insufficient applications to fully use the allocated funding (such that all applications in that state and sector were awarded funding, irrespective of their score) as well as where a significant proportion of the applications received a low aggregate score. The risk of this occurring was not explicitly considered in departmental advice on the redesign of the program either in 2010, when the NSSP moved to be a competitive, merit-based program, or in 2011 when the program funding and timeframe was curtailed.

[23] Awarding funding to all eligible applications in certain states and sectors, irrespective of their aggregate score, means that the program has in certain respects continued to operate as a demand-driven program.

[24] This includes the $200 million Community Energy Efficiency Program, established as part the Government's plan for a Clean Energy Future, as a competitive, merit-based grant program to provide matched funding to local councils and non-profit community organisations to undertake energy efficiency upgrades and retrofits to council and community-use buildings, facilities and lighting. ANAO’s Audit Work Plan for 2012–13 includes a potential audit of the Community Energy Efficiency Program.

[25] A final evaluation, at the conclusion of the program, is also to be conducted.

[26] In this respect, the CGGs state (on page 22) that: ‘Clear, consistent and well-documented grant guidelines are an important component of effective and accessible grants administration. A single reference source for policy guidance, administrative procedures, appraisal criteria, monitoring requirements, evaluation strategies and standard forms, helps to ensure consistent and efficient grants administration.’

[27] See further in ANAO Audit Report No. 36 2011–12, Development and Approval of Grant Program Guidelines, Canberra, 30 May 2012, pp. 88–89.

[28] Commonwealth Grant Guidelines, p. 29.

[29] Under the Commonwealth’s financial framework, the overall test as to whether public money should be spent requires consideration of whether a spending proposal represents efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of public money that is consistent with the policies of the Commonwealth (particularly the CGGs and the grant program guidelines). Often, this is referred to as a ‘value for money’ test. In this context, for the NSSP, the value for money criterion was focused on whether the costs of the item(s) in the project were considered reasonable (by comparing the costs to the cost of similar items and other applications, and having regard to whether quotes had been obtained). In terms of the financial framework, this analysis addressed the issue of whether each proposed grant was economical.

[30] This issue has been raised in a number of ANAO audit reports. See, for example, ANAO Audit Report No. 7 2011–12, Establishment, Implementation and Administration of the Infrastructure Employment Projects Stream of the Jobs Fund, Canberra, 22 September 2011 and ANAO Audit Report No. 27 2011–12, Establishment, Implementation and Administration of the Bike Paths Component of the Local Jobs Stream of the Jobs Fund, Canberra, 20 March 2012.

[31] See footnote 36 and paragraph 5.21 concerning the reasons for the average cost difference between government and non-government schools in relation to the installation of solar power systems.

[32] Namely: solar power systems; hot water systems; rain water tanks; or energy efficient lighting.

[33] An important element in the assessment of applications was use of DCCEE’s Web Application Assessment module. This application calculated the value for money, environmental benefit and components of educational benefit scores based on data provided by schools in their applications.

[34] Attachments were also included for government school applications to the 2011–12 funding round, with the list of projects approved in each state again sorted in order of highest to lowest aggregate assessment score.

[35] This was reflected in the program guidelines and administrative arrangements document which, respectively, stated as follows:

- ‘A merit-based, competitive assessment process will be used to determine which applications best meet these criteria and will be offered funding’; and

- ‘This merit-based, competitive assessment process is used to determine which applications best meet these criteria and will be offered funding. …Applications will be scored against each criterion with an additional score allocated to schools located in remote or low socio-economic areas. Applications will be ranked on the basis of those scores and funding will then be granted based on the rankings (highest to lowest) until the funding allocation for that state and sector is fully committed.’

[36] By a significant margin, the most popular item funded under the NSSP has been the installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. On average, non-government schools over the last three years have been able to obtain lower cost solar power systems, compared to government schools. For the 2011–12 grant year, the cost difference was approximately 20 per cent. The major contributing factor to this difference is that economies of scale operate, such that the cost of solar power systems per kilowatt decrease as system sizes increase. Non-government schools on average have installed larger solar power systems due to larger average NSSP grants compared to the level for government schools, which enable the achievement of slightly lower per unit costs. For example, in the 2011–12 funding round, there was only an average $145 (around three per cent) cost difference per kilowatt in favour of non-government schools, where government and non-government schools were planning to install 5 to 10 kilowatt solar power systems.

[37] In comparative terms, the NSSP’s contribution to the growth of the renewable energy industry has been relatively small. A degree of concentration has occurred around solar power systems being installed by a relatively limited number of suppliers, but this partly reflects procurement panel arrangements for government schools in a number of states.

[38] In particular, there have been issues identified through compliance inspections with the standard of system installations and not all of the installed systems are performing in line with the solar production estimates from the Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator (ORER) (which were relied upon in preparing the estimate).