Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Aviation and Maritime Security Identification Card Schemes

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Department of Infrastructure and Transport’s and the Attorney‐General’s Department’s management of the Aviation and Maritime Security Identification Card (ASIC and MSIC) schemes.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Aviation and Maritime Security Identification Card schemes (ASIC and MSIC schemes) were introduced by the Australian Government to enhance the existing ‘layers of security’ designed to safeguard the aviation and maritime industries.[1] ASICs and MSICs are displayed by individuals to demonstrate that the holder has had their background checked and is permitted to be in the ‘secure areas’ of aviation and maritime zones (typically specific parts of airports, seaports and offshore facilities, such as oil and gas rigs). ASICs and MSICs are generally required by a range of people who work in secure zones, including: airline staff; airport service workers; baggage handlers; port service workers; stevedores; and transport operators such as train and truck drivers.

2. The ASIC and MSIC schemes are established by the Aviation Transport Security Act 2004 (ATS Act) and the Maritime Transport and Offshore Facilities Security Act 2003 (MTOFS Act). The aim of the schemes is to: safeguard against unlawful interference with Australia’s aviation, maritime transport and offshore facilities, and to reduce the risk of terrorist infiltration.

3. The ASIC and MSIC legislation prescribes a range of conditions for the use of the cards and the eligibility criteria for obtaining an ASIC or MSIC. Table S.1 outlines the broad key criteria for obtaining an ASIC or MSIC.

Table S.1: Criteria for obtaining an ASIC and MSIC

Source: Aviation Transport Security Regulations 2005 (ATS Regulations) and Maritime Transport and Offshore Facilities Security Regulations 2003 (MTOFS Regulations).

Overview of management arrangements for the ASIC and MSIC schemes

4. There is a diverse range of government and industry bodies involved in the management and delivery of the ASIC and MSIC schemes. This includes over 1200 industry participants, including airports, airlines and seaports, which are required to develop security plans that outline arrangements by which access to designated secure areas is restricted to ASIC and MSIC holders.

5. Further, more than 200 government and non-government bodies have been authorised to issue ASICs and MSICs. These issuing bodies have a range of responsibilities under the ATS and MTOFS Acts relating to the production and issue of ASICs and MSICs. For many applicants, the relevant issuing body is their employer, local airport or seaport. However, the schemes also allow commercially based ‘third party’ issuing bodies that do not necessarily have a direct relationship to the applicant to issue ASICs and MSICs. The cards produced by issuing bodies include a tamper-evident feature designed to reduce the risk of forgery.

6. The Department of Infrastructure and Transport (DIT) administers the ATS Act and MTOFS Act on behalf of the Australian Government. Within DIT, the Office of Transport Security (OTS) has principal responsibility for administering transport security. OTS’s primary role as the transport security regulator is the approval of transport security plans and monitoring compliance with approved plans. In relation to the ASIC and MSIC schemes, OTS approves ASIC programs and MSIC plans, on behalf of the Secretary, and monitors the compliance of industry participants, issuing bodies and cardholders.

7. Central to the ASIC and MSIC schemes is the requirement that applicants have their background checked. The AusCheck Act 2007 (AusCheck Act), administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), establishes the processes for the background check. AusCheck, a branch within AGD, coordinates the background check. The check involves a criminal records check coordinated by CrimTrac; a security assessment by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation; and if relevant, a citizenship or immigration check, conducted by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. AusCheck is also responsible for maintaining the AusCheck database, the consolidated database of all ASIC and MSIC cardholders. As at 30 June 2010 there were 265 328 valid issued cards (126 806 ASICs and 138 522 MSICs) recorded on the AusCheck database.

8. Table S.2 summarises the key responsibilities of the parties involved in the ASIC and MSIC schemes.

Table S.2: Key ASIC and MSIC responsibilities

Source: ANAO analysis.

9. Historically, there has been significant interest in the role of ASICs and MSICs in relation to their contribution to the security of the aviation and maritime industries. Parliamentary and internal reviews have highlighted a number of inherent vulnerabilities associated with having a large number of issuing bodies, as well as the return of expired or cancelled cards and visitor management. Most recently, the National Aviation Policy White Paper: Flight Path to the Future,[3] released in 2009, included a commitment to strengthening the ASIC scheme to address some of these identified vulnerabilities. Measures to strengthen the cancellation provisions for issuing bodies and tighten visitor management arrangements are in the process of being implemented.

Audit objectives, criteria and scope

10. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIT’s and AGD’s management of the ASIC and MSIC schemes.

11. In assessing the performance of DIT and AGD, the ANAO examined the effectiveness of the: governance arrangements supporting the schemes; process for issuing cards; information technology (IT) environment supporting the schemes; and compliance activities surrounding the schemes.

12. The scope was confined to the role undertaken by DIT and AGD; it did not examine the work of others with an interest in the ASIC and MSIC schemes, such as law enforcement and national security agencies.

Overall conclusion

13. The ASIC and MSIC schemes form part of the Australian Government’s layered approach to safeguarding the aviation and maritime industries against terrorism and other unlawful acts. This approach requires judgements to be made about the appropriate balance between the risk of such acts occurring and the impact mitigation strategies, such as security cards, may have on the efficient operations of these facilities.

14. Consistent with their legislative frameworks, the ASIC and MSIC schemes provide for the involvement of a range of entities, including both industry organisations and Australian Government agencies. OTS, a division within DIT, administers the regulatory framework for the schemes on behalf of the Australian Government, and AusCheck, a branch within AGD, coordinates the background checks of ASIC and MSIC applicants. There are also over 1200 industry participants that regulate access to secure areas where the display of ASICs and MSICs is required, in excess of 200 bodies that are authorised to issue the cards, and some 250 000 cardholders, who are required to meet their obligations to properly display a valid security card while in a secure area.

15. The successful implementation of the ASIC and MSIC schemes has meant that, with some specific exceptions,[4] all persons who legitimately enter and remain in a secure area of an airport, seaport or offshore facility must now have been assessed as meeting the criteria for an ASIC or MSIC, including having their background checked, and must display their card appropriately. The arrangements put in place by OTS and AusCheck to administer the schemes reflect legislative requirements and facilitate the timely issue of security cards. However, some of the risks associated with the current delivery model could be better managed by OTS. These risks primarily relate to issuing bodies and visitor management and are inherent in the devolved nature of the schemes.

16. As previously noted, the regulatory framework of the ASIC and MSIC schemes includes over 200 authorised issuing bodies that process applications, produce and issue the identification cards. The majority of cards (80 per cent), however, are issued by a small number (20 per cent) of issuing bodies. Further, 35 per cent of all cards are issued by commercially based ‘third party’ issuing bodies, that have a limited ongoing relationship to the applicant. While the schemes prescribe mandatory standards for issuing bodies, these standards are not being consistently met by some issuing bodies. This includes how an applicant’s operational need for the card is established and maintaining adequate records to demonstrate that an applicant’s identity has been confirmed.

17. OTS has developed a compliance framework that aims to cooperatively encourage compliance through education and audit activities, with the focus being on high-risk participants. While the framework is appropriately targeted at high-risk participants, it could be strengthened if information obtained through OTS’s audit, inspection and stakeholder programs was used to better inform and focus the schemes’ compliance activities.

18. A further area of concern is visitors entering secure areas at airports. Visitors can obtain a visitor identification card (VIC)[5] and, although a VIC holder must be supervised, they do not need to undergo the background check required for an ASIC. Concerns about the VIC regime have been raised by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit over a number of years. Revised regulations to tighten the VIC scheme are being developed, although these changes have been slow to eventuate. The total number of VICs being issued is not known, but around 40 000 were issued at one delivery gate alone at a major airport in 2009–10. Moreover, many VICs are issued repeatedly to the same individuals, effectively bypassing the ASIC background checking process. Better information on the actual usage of VICs would also assist OTS to manage this potential risk to the ASIC scheme.

19. It is difficult to obtain a reliable count of the total number of current ASIC and MSIC cards, or the currency of all cards on the AusCheck database. This is despite the database being established to provide a comprehensive record of all ASIC and MSIC applicants and cardholders. Each issuing body also maintains a database of its cardholders. Although AusCheck has developed a range of controls over the integrity of the information entered into its database, changes in one database do not always flow through to the other. As a consequence the two data sets differ markedly. More focused compliance activity would give AusCheck and OTS greater assurance around the procedures and practices adopted by issuing bodies as well as the accuracy of their databases.

20. OTS has been working with industry stakeholders on a range of strategies to manage some of the vulnerabilities identified by this audit and previous reviews. These include implementing changes to the frequency of background checks, cancellation provisions for ASIC issuing bodies, and the tightening of eligibility rules for VICs. As these changes are still to be bedded down, their capacity to mitigate these risks to the schemes’ effectiveness is yet to be demonstrated. While recognising that a balance needs to be struck between the impact of regulation on industry and the achievement of the Government’s security objectives for the ASIC and MSIC schemes, continued management focus on these identified vulnerabilities is warranted. To this end, the ANAO has made three recommendations aimed at further improving the effectiveness of these areas and the overall management of the ASIC and MSIC schemes.

Key findings

Governance arrangements

21. There has been an ongoing evolution in the broad structures of governance put in place by OTS and AusCheck to support the implementation of the ASIC and MSIC schemes. OTS has implemented an organisational structure that allows it to implement, monitor and coordinate tasks and deliverables. It has also developed an appropriate framework for monitoring and reporting activities. Key operational risks were documented and updated in OTS’s risk register, and had clear mitigation strategies. In addition, the activities of AusCheck are subject to the Government’s cost recovery policy and it has established effective processes to identify the price structure and cost of its regulatory activities over the course of the program’s life.

22. The National Aviation Policy White Paper: Flight Path to the Future (White Paper),[6] released in 2009 included a commitment to strengthening the ASIC scheme to address some previously identified vulnerabilities. OTS, in responding to the White Paper, has developed and is currently implementing proposed changes to the ASIC scheme. These changes, which include strengthening the cancellation provisions for ASIC issuing bodies and tightening the provisions for visitor management will not, however, directly address all the identified vulnerabilities. For example, while there is a proposal to reduce the number of issuing bodies, the proposal will remove inactive issuing bodies and provide a transitional pathway for other issuing bodies to cease operations. It will not address the inconsistencies in the approaches taken by many bodies currently issuing the cards and that are not meeting the required standards.

The process for issuing ASICs and MSICs

23. The application process for ASICs and MSICs involves a wide range of stakeholders and different processes. The schemes rely on each participant understanding, and correctly applying, the legislative process. As previously mentioned, more than 200 government and non-government bodies have been authorised to issue ASICs and MSICs. These issuing bodies includes airlines, airports and seaports as well as commercially based ‘third party’ issuing bodies that do not necessarily have a direct relationship to the applicant. The role of OTS in these circumstances is to provide guidance and assistance, and to gain assurance from each issuing body that they are fulfilling their obligations to the required standard.

24. There are a range of practices in the issuing of ASICs and MSICs that reduce the assurance that the schemes’ requirements are being met to appropriate standards. These include:

- third-party issuing bodies complying with mandatory standards in how an applicant’s operational need for the card is established; and

- the evidence to demonstrate confirmation of an applicant’s identity. Records maintained by issuing bodies to confirm the identity of the applicant were incomplete. For two issuing bodies assessed by the ANAO the required identity credentials were not available for 33 per cent of the applications reviewed.

25. ASICs and MSICs are made using specialised stamping machines and licensed technology. There are 25 entities that have the machines to make the cards—24 of which are also issuing bodies under the ASIC and MSIC schemes. Consequently, many issuing bodies do not produce the cards themselves, instead they use other entities to produce the cards on their behalf. Some 37 per cent of all ASICs and MSICs are made by an entity other than the issuing body. Presently, OTS has a relationship with the company that makes the stamping machines, and with most entities that use the machines to make the cards, by virtue of them also being issuing bodies under the ASIC and MSIC schemes. However, one card maker that has produced some 35 000 cards, is not an issuing body, and is therefore not subject to any formal ongoing oversight by OTS.

26. AusCheck also plays a central role in the process for issuing ASICs and MSICs by providing background checks for issuing bodies. This role includes assessing each applicant’s details against the legislative criteria and making a final recommendation whether these criteria have been met by the applicant. The ANAO’s analysis of a sample of 88 applicants indicated that AusCheck assessors correctly assessed the criminal history against the legislative requirements for all the applications reviewed. The ANAO also analysed 20 recent applicants with conditional or adverse assessments. AusCheck had complied with the legislative requirements, including procedural fairness and notification of appeal rights, for these applications. It has also developed standard operating procedures, checklists and templates to support its decision–making processes.

27. ASIC and MSIC applications are processed in a timely manner. Based on an extract of the AusCheck database in June 2010, AusCheck processed 97 per cent of its background checking activity within one day and 99 per cent was completed in five business days or less. In terms of the ‘end-to-end’ processing time, around 50 per cent of checks were completed within two weeks. The total time of a background check may also be affected by the time an application is assessed by background checking partners.

28. Rejected applicants can apply for a discretionary ASIC or MSIC and provide additional information that demonstrates that the person is unlikely to be a threat to aviation or maritime security—this occurred 112 times in 2009–10. OTS has developed a range of templates, checklists and ‘how to guides’ to support the processing of the discretionary cards. The ANAO reviewed 21 applications and these were generally processed in accordance with legislative requirements. OTS applied a risk-based, evidence-informed approach in assessing whether the applicant represented a risk to transport security.

Information management

29. AusCheck, in processing and maintaining a central register of all ASICs and MSICs, relies on one main information technology system. An inherent risk with the AusCheck database is that there is no direct and ongoing link between this database and the issuing bodies’ data holdings. To mitigate this risk, AusCheck has implemented mandatory controls over the input of data, including data field validation, and access is controlled through formalised processes.

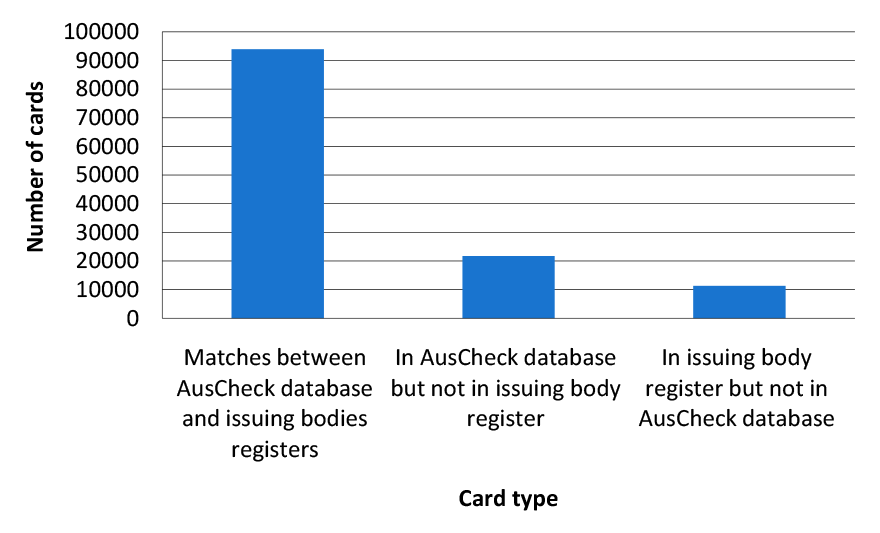

30. The AusCheck database was established to provide a ‘comprehensive database of all applicants and ASIC and MSIC cardholders.’ Each issuing body also maintains a database of its cardholders.[7] Comparison of AusCheck data with issuing body data for 50 per cent of all cardholders by the ANAO identified significant variances. For example, there was a significant number of cards registered on the AusCheck database that were not in an issuing body’s register. There were also cards registered in issuing bodies’ registers but not in the AusCheck database. Figure S.1 provides a summary of the total figures within each population.

Figure S.1: Number of cards from selected issuing bodies matched against the AusCheck database

Source: ANAO analysis of AusCheck and issuing body data.

31. These variances were largely due to administrative or process differences and errors. While the differences between the databases can be partly explained by the devolved nature of the ASIC and MSIC schemes, they do reduce confidence in the accuracy of the total number of current cards, and the currency of the data in the AusCheck database. Currently, OTS conducts basic checks of issuing bodies’ compliance with the regulations but does not assess their processes or systems in a systematic way. OTS has the ability, through more focused compliance activity, to gain further assurance around the procedures and practices adopted by issuing bodies as well as the accuracy of the various databases.

Compliance activities

32. The security arrangements for Australian aviation and maritime environments place responsibility on every industry participant to comply with relevant security plans. OTS has established a compliance framework for the ASIC and MSIC schemes that is primarily focused on compliance by high risk industry participants and issuing bodies. This framework includes a range of audit, inspection and stakeholder activities. The ANAO’s examination of 46 high risk industry participants indicated that the planned compliance activities had occurred. However, there was some inconsistency in practices between OTS offices, which OTS has taken action to address. OTS is also not making the best use of the substantial amount of information it holds about industry participants obtained from its audit, inspection and stakeholder programs to refine and inform its compliance activities.

33. OTS has a compliance regime in place that aims to cooperatively encourage compliance through education and audit activities. It regularly identifies examples of non-compliance, such as the improper display of ASICs and MSICs, as well the lack of supervision of VIC holders, suggesting that education activities have not been fully effective.[8] While isolated instances of non-display of cards is an ongoing issue, the ANAO observed general compliance during site visits to 29 different security controlled areas across seven states/territories in Australia.

34. The ATS Act and MTOFS Act provide for an enforcement regime for non compliance that includes a range of options that can be used as an alternative to, or in addition to, criminal prosecution, however, these powers have not been used. The emphasis has been on education activities only. OTS is developing an enforcement capability which, if effectively implemented, will assist OTS to deliver a graduated range of responses to address non-compliance.

35. The non-return of expired and cancelled cards is a further example of non-compliance that has been an ongoing issue for many years. The evidence suggests that the current method of educating cardholders of their obligations has not been fully effective. The ANAO’s analysis of the OTS data indicates that, for 2009–10, the rate of cancelled or expired cards not being returned to the issuing body was:

- ASIC scheme—12 100 from a population of 40 652 (30 per cent); and

- MSIC scheme—601 from a population of 2225 (27 per cent).

The long history of the non-return of expired and cancelled cards suggests that stronger administration or policy solutions should be considered by OTS to improve the rate of return of these cards by issuing bodies.

36. Within the aviation sector, the VIC scheme allows supervised visitors to enter the secure areas of an airport without a background check. The ANAO’s analysis has highlighted examples of the substantial use of VICs by individuals as a means to regularly access secure areas of an airport. In 2009–10, based on available data at a selected major airport, around 40 000 VICs were issued at one delivery gate and around 90 per cent of the VICs issued were to individuals who had multiple visits. While VIC holders are required to be supervised, these individuals are using the VIC scheme to gain access to secure areas without the assurance provided by a background check. OTS has been aware of weaknesses in the VIC scheme and has developed proposed regulatory changes to tighten the provisions for visitor management. Due to potential legal impediments, OTS relied primarily on industry advice rather than analysing actual VIC usage to inform these proposed changes. Going forward, determining baseline data and regularly reviewing airport data on the actual usage of VICs would assist OTS in assessing the effectiveness of the changes to the VIC scheme.

Summary of agency responses

Attorney-General’s Department

37. The Attorney-General’s Department welcomes this report by the ANAO, and will work closely with the Office of Transport Security in implementing any changes. AusCheck is keen to work with the Issuing Bodies to enhance their understanding of the operation of the AusCheck System and using it to meet obligations under the relevant regulations. AusCheck is also committed to increasing use of the Card Verification System—which provides an online way to verify the authenticity of an individual’s ASIC or MSIC—and how it can be accessed and used by ports and airports.

Department of Infrastructure and Transport

38. The Department of Infrastructure and Transport (DIT) welcomes the ANAO Performance Audit into the management of the ASIC and MSIC schemes, and notes positive comments made about a range of matters including DIT’s approach to risk management, governance and industry consultation. As part of our on-going continuous improvement process, DIT will continue to working closely with our partner agencies and industry stakeholders to further refine the ASIC and MSIC schemes to better meet the Government’s policy objective of providing an efficient, sustainable, competitive, safe and secure transport system.

Footnotes

[1] Australia’s current approach to transport security relies on activities across the following complementary layers: intelligence to identify threats; targeted mitigation strategies at last ports of call (the point of departure) to detect and interdict risks before they depart for Australia; law enforcement measures; security measures at airports, seaports and offshore facilities, including preventive physical and identity security measures and access control; passenger, baggage and cargo screening; and aircraft, ship and offshore facilities security. Commonwealth of Australia, Counter-Terrorism White Paper, 2010.

[2] The definition of ‘security assessment’ under both the ATS Regulations and MTOFS Regulations has the same meaning as in Part IV of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979.

[3] Commonwealth of Australia, National Aviation Policy White Paper: Flight Path to the Future, 2009.

[4] This includes passengers who are boarding or disembarking from an aircraft; supervised visitors to secure areas, crew of a foreign aircraft, crew members of certain ships and emergency personnel who are responding to an emergency.

[5] The Aviation Transport Security Regulations 2005 prescribe rules for the display and issuing of VICs for supervised visitors within aviation secure areas. There is no equivalent card for maritime and offshore facilities.

[6] Commonwealth of Australia, National Aviation Policy White Paper: Flight Path to the Future, 2009.

[7] Second Reading Speech, AusCheck Bill 2006, House of Representatives Hansard, 7 December 2006, p. 12.

[8] During fieldwork, the ANAO also observed instances of non-display of ASICs and MSICs, as well as the lack of supervision of a VIC holder.