Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Student Visas

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIAC’s management of the student visa program. Three key areas were examined in the audit: the processing of student visa applications; ensuring compliance with student visa conditions; and cooperation between DIAC and DEEWR.

Summary

Introduction

1. The international education and training sector is Australia’s third largest export industry, behind coal and iron ore, and was worth an estimated $18.6 billion in 2009. The Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) is responsible for the entry of students to Australia through its administration of the Migration Act 1958 (the Migration Act) and assessment of student visa applications. DIAC is also responsible for the compliance of student visa holders with their visa conditions once they are onshore.

2. DIAC works with the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) in administering the student visa program. DEEWR is responsible for the Education Services for Overseas Students Act 2000 (the ESOS Act), which sets out the legal framework governing the education provided to international students that hold a student visa.

3. DIAC’s objective for the Visa and Migration Program is that its targeted migration program will continue to respond to Australia’s changing economic and social needs through, among other things, ongoing ‘assistance to the tourism and education industries to expand, including into new markets, whilst ensuring a high degree of immigration integrity’.

4. There are seven subclasses of visa available for students to enter Australia for the express purpose of studying. The subclasses correspond to the different education sectors, as follows:

- independent English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS) sector (subclass 570);

- schools sector (subclass 571);

- vocational education and training (VET) sector (subclass 572);

- higher education sector (subclass 573);

- postgraduate research sector (subclass 574);

- non award sector (subclass 575); and

- AusAID or Defence sector (subclass 576).

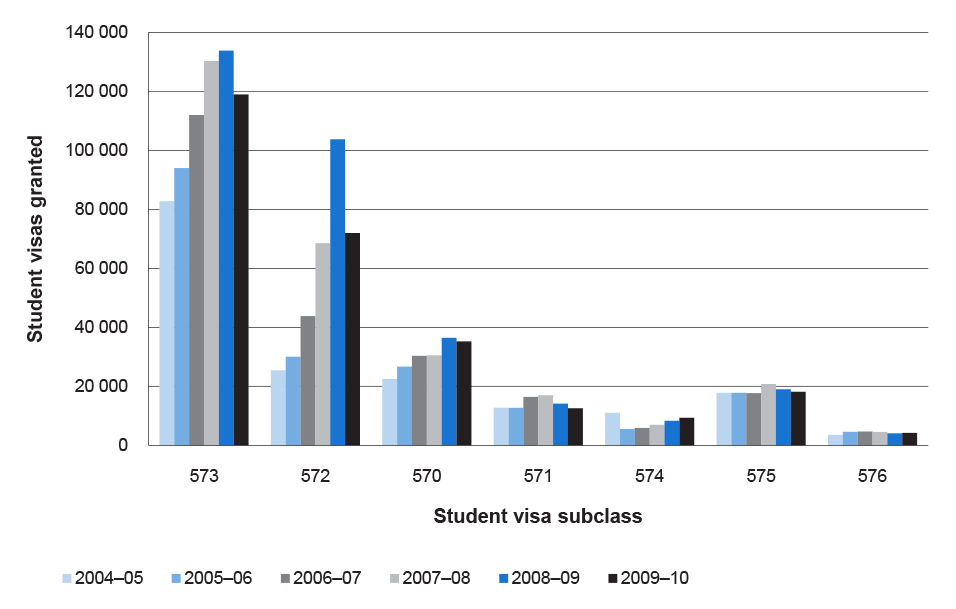

The relative size of each subclass and trends in visas granted per subclass are shown in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1: Student visa grants by subclass from 2004–05 to 2009–10

Source: ANAO analysis of DIAC data.

5. The student visa population comprises students from 197 countries. Approximately one third of the caseload is from the top two source countries (China and India); one third is from the next eight largest source countries;[1] and the final third from the remaining 187 countries.

6. DIAC assesses and manages immigration risk in this large caseload, primarily through a process of setting and periodically reviewing the assessment levels (ALs) for each country and education sector. The designated AL determines the evidentiary requirements that an applicant for a student visa is required to satisfy for a visa to be granted. There are five ALs, with AL1 representing the lowest immigration risk and therefore having the least onerous evidentiary requirements.

7. The student visa program grew at an average of 15 per cent per annum over the decade prior to 2009–10. In 2009–10, DIAC received 296 558 student visa applications, a decrease of 19 per cent from 2008–09. This was the first year of negative growth in total applications in many years.

8. A number of factors that contributed to the decline in student visa applications in 2009–10 have been identified, including the:

- high value of the Australian dollar;

- impact of the global economic downturn;

- impact of migration policy changes;

- increased competition in the international student market from other countries;

- negative publicity about student safety in Australia following attacks on Indian students in 2009;

- strengthened quality requirements for education providers; and

- uncertainty created by college closures.

Responding to the growth of the student visa program

9. During 2008–09, it became apparent to DIAC that many overseas students were deciding to study in Australia for the purpose of gaining permanent residence under the skilled migration program, which requires applicants to pass a points test. The pathway to permanent residence was opened in 2005 by the inclusion in the Migration Occupations in Demand List (MODL) of a number of trade occupations and the availability of additional points for qualifications in these trades.

10. The availability of this pathway led to an annual average growth in overseas student enrolments in the VET sector of 36 per cent from 2005 to 2009, with major growth in courses such as hospitality and hospitality management, cookery and hairdressing. These courses were shorter and cheaper than higher education courses but potentially yielded the same permanent migration outcome.

11. This trend had several negative impacts. Skilled migration is a capped program closely linked to the management by government of capacity constraints and skills shortages in the economy. The growing number of student visa applicants for permanent residence in the skills stream was creating a pool of ex students in Australia with relatively low value and low priority skills in a lengthening application queue. This trend, if unchecked, would impact on the level of Net Overseas Migration considered desirable by the Government.[2]

12. Furthermore, students using the student visa program to gain a permanent residence outcome were not coming to Australia with a genuine intention to study, as is required for a student visa grant, and return home afterwards. Education agents also played a role in promoting student visas as a guaranteed permanent residence outcome and facilitated the applications of clients with that motivation.

13. In 2009–10, a number of policy changes were introduced by the Government with the aim of strengthening the integrity of the student visa program. These included the announcement between August 2009 and April 2010 of a series of student visa integrity measures. In February 2010, the Government also announced changes to the general skilled migration program, including the abolition of the MODL in favour of a tighter Skilled Occupations List, thereby significantly restricting the pathway to permanent residence for student visa holders.

14. Commenting on these policy changes, the then Minister for Immigration and Citizenship described the growth in the VET sector as unsustainable and stated that ‘students is a classic example of where governments lost control of the program’.[3] He also noted that the practice of overseas students seeking permanent residence through low quality education courses damaged the integrity of both the migration program and the education industry.[4]

15. On 16 December 2010, the Government announced a strategic review of the student visa program to be conducted by the Hon Michael Knight AO. The review was tasked with enhancing the continued competitiveness of the international education sector, as well as strengthening the integrity of the student visa program. The review will report by mid 2011.

Audit objective

16. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIAC’s management of the student visa program. Three key areas were examined in the audit: the processing of student visa applications; ensuring compliance with student visa conditions; and cooperation between DIAC and DEEWR.

Overall conclusion

17. The international education and training sector is Australia’s third largest export industry and was worth an estimated $18.6 billion in 2009. The student visa program is a critical enabler of this significant export industry. In managing the program, DIAC is required to keep two interests in balance—supporting the expansion of the industry while maintaining a high level of integrity in the visa program.

18. Over the past decade, DIAC’s management of the student visa program has successfully supported the growth of one of Australia’s largest export industries and enabled over a million and a half students to access high quality education in Australia. However, the permanent residence pathway available to overseas students though skilled migration caused an unsustainable level of growth in the program and compromised its integrity. As a consequence, the Government introduced policy changes during 2009–10 to restrict this pathway.

19. The student visa program presents more processing challenges for DIAC than any other temporary visa class. DIAC has introduced a number of initiatives over the years to assist it to meet these challenges and manage a growing workload, including:

- the assessment level process, introduced in 2001, to assess and manage risk in the program;

- an innovative electronic visa lodgement (eVisa) facility to speed up visa processing for students, introduced for low risk cohorts in 2001–02 and for four higher risk countries in 2004 and 2005, including China and India, the two largest source countries; and

- an eHealth initiative, implemented progressively from 2002, reducing the time required for finalisation of an offshore visa applicant’s health assessment from 4–6 weeks to 48 hours.

20. Overall, the ANAO concluded that a number of DIAC’s key administrative structures and processes were not sufficiently robust to effectively meet the challenges involved in achieving the Government’s objective for the student visa program of balancing industry growth and program integrity. Fundamental to this is maintaining alignment between the student visa program and the contemporary international education environment. Irrespective of the particular problems and policy changes associated with the permanent residence pathway issue, visa processing arrangements and compliance functions, as well as the primary collaborative relationship with DEEWR, have not kept pace with the demands of this dynamic program environment.

21. Visa processing arrangements provide for a risk based approach to setting visa requirements, and an eVisa facility to manage large application caseloads. There is considerable scope for the department to strengthen its process for determining the risk based assessment levels for countries and education sectors, to better align student visa requirements with contemporary program integrity risks. There would also be benefit in the department evaluating the client service and processing efficiency benefits of eVisa for students, given that evaluations of the eVisa facilities conducted by DIAC in 2007 were never finalised or implemented. One of those evaluations identified early indications of deficiencies in the department’s monitoring of the performance of eVisa agents participating in a trial of the eVisa facility for students from four higher risk countries. A subsequent review of eVisa agent access to the trial in 2009–10 led to the deregistration of some 300 eVisa agents and the introduction of a more stringent Deed of Agreement for eVisa agents. It will be important for DIAC to maintain a regular program of audits and evaluation of eVisa agent compliance with the terms of the new Deed of Agreement.

22. The rapid growth of the program, with over 400 000 overseas students living in Australia in 2009–10, placed significant pressure on DIAC’s compliance functions. DIAC’s integrity and compliance units were hampered in managing this pressure by the department’s failure to update its national compliance priorities after 2008, and by the backlog of Non Compliance Notices[5] for student visa holders, estimated to be in excess of 350 000 by the middle of 2010. While much of this backlog related to relatively minor administrative matters, it potentially obscured serious cases of student non compliance. There are also significant problems with the effectiveness of DIAC’s visa cancellation procedures for the mandatory visa conditions relating to students maintaining satisfactory course progress and attendance, and their working rights allowance of 20 hours per week. The enforceability of both these mandatory conditions requires careful review.

23. There are strong interdependencies between DIAC and DEEWR, that require close collaboration. Each department is reliant on the effective performance of the other’s functions to achieve the Government’s objectives for international education. While the relationship between the departments is effective at the working level, it lacks mechanisms to provide a shared strategic direction and agreed priorities to guide the interaction of the student visa program with the international education sector. Although the relationship has recently been strengthened by secondments and there are plans to establish a regular policy forum between the two departments, the membership and remit of that forum should be formulated to enable it to perform a strategic role.

24. In response to the acknowledged problems with the student visa program, DIAC instituted a number of organisational improvements during 2010, many as part of the DIAC transformation program initiated by the Secretary late in 2009. These include the appointment of Global Managers to manage particular business lines on a corporate wide basis. The Global Managers responsible for Temporary Entry Visas and for Operational Integrity have both introduced initiatives that should support the promulgation of better practice and management of caseloads in student visa processing and student visa integrity and compliance. The appointment of an eBusiness Global Manager and development of an eBusiness Strategy provides for better corporate ownership and direction of the eVisa facility. Action is also underway to reduce the backlog of NCNs.

25. These organisational changes, when bedded down, can be expected to improve DIAC’s management of the student visa program. In terms of the objective of the program, DIAC is now emphasising, in the visa and migration program deliverables listed in its Annual Report, that growth in international education must be sustainable. In the context of the outcomes of the current strategic review of the program, and the establishment of a new Interdepartmental Forum on International Education, it will be important for DIAC to define the meaning of sustainable growth for the future direction of the program. Continued reform in DIAC’s student visa processes and governance structures, and more effective collaboration with DEEWR, is required to achieve and maintain an appropriate alignment between the program and the demands of the international education environment, as well as achieve the required balance between sustainable growth and program integrity.

26. The ANAO has made six recommendations directed towards strengthening DIAC’s management of student visa processing, student visa compliance and the quality of its relationship with DEEWR.

Key findings

Administration of student visa processing

27. Student visa processing is a highly complex activity because of the number of source countries for overseas students, the number of education sectors and visa subclasses, the range of visa rules and requirements and the options available for lodging visa applications. Extensive corporate policy guidance and the business rules built into DIAC’s visa processing systems provide a generally effective and unified framework for the processing of student visas. However, there is no business model setting out standard processing practice for all student visa processing centres to follow and there are variations in practice between different centres, which carries the risk of inconsistent decision making. DIAC has commenced work to map student visa processes to assist with the determination of best practice. It will be important that DIAC codify the outcomes of this work in an appropriate corporate guidance document.

28. There are two peak periods a year for student visa applications. The major peak in February–April represents approximately 25 per cent of the annual caseload and can generate up to 1000 applications in a day. DIAC aims to process 75 per cent of student visa applications within processing times published in its service standards. However, it has not met this target since 2001, partly due to the pressure on processing resources during the peak periods. Despite its awareness of the peak periods as a characteristic of student visa processing, DIAC only instituted a Student Peak Plan and dedicated Student Peak Processing Team for the first time for the February–April 2010 peak. The introduction of a Student Peak Plan was a positive initiative, but to confirm its value as an ongoing strategy there would be benefit in DIAC evaluating the Peak Processing Team’s effectiveness in improving performance and achieving the financial return of $2.42 million estimated from its operation.

29. A fundamental requirement of a student visa grant is that the student must have a valid Confirmation of Enrolment (CoE) from a registered education provider. The ANAO analysed 615 726 student visa records covering the two years from 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2010 for inconsistencies between client data recorded in DIAC’s Integrated Client Services Environment (ICSE) and CoE data recorded on DEEWR’s Provider Registration and International Student Management System (PRISMS), particularly whether any student visas were attached to an incorrect CoE. A minimal number—less than a half of one per cent—of inconsistencies were found. This positive outcome was partly the result of ongoing monitoring and manual correction by DIAC and DEEWR officers of differences in data between their respective systems.

Determining student visa assessment levels

30. DIAC determines the level of immigration risk posed by students from each country and education sector/visa subclass through a risk assessment tool called an assessment level. There are five assessment levels, with AL1 representing the lowest immigration risk and AL5 the highest. AL1 countries have the least onerous evidentiary requirements. DIAC reviews assessment levels periodically.

31. The assessment level review process is struggling to cope with the current scale and complexity of the program. Its methodology is not up to date and may not reflect the current integrity risks. It uses risk factor weightings dating from 2004 and benchmarks set in 2007 based on performance data from 2002–2005. Nor is the methodology robust: the application of rules for small countries is problematic; ratings are often distorted by the high risk weighting given to Protection Visa applications; and ‘on notice’ warnings to countries to improve integrity performance are ineffective. Some features of the methodology reduce its agility to respond to emerging integrity trends. These include the basing of prospective assessment level rankings on retrospective data analysis; and improved rankings being implemented immediately, whereas the implementation of deteriorating rankings is delayed. The methodology is also inconsistently applied. In some cases, this was due to DIAC officers modifying risk rating outcomes distorted by problems in the methodology. While there is provision in the methodology for modifications to risk rating outcomes to be made during the process, in a number of cases the reasons for modified outcomes were neither documented nor transparent.

32. According to DIAC, the purpose of the assessment levels is to align visa requirements to the demonstrated risk of the visa applicant and to clear, objective, evidence of compliance rates. However, a number of interventions to modify risk ratings resulted in AL1 countries remaining at that level when quantitative analysis against risk factors would have increased the assessment level. In reality, the assessment level process necessarily negotiates between DIAC’s integrity interests; its program objective of assisting the growth of the international education industry; and its interests in increased efficiency in visa processing. The interplay of these interests was illustrated by the outcomes of the 2010 assessment level review, which included a reduction in the ranking for the China and India higher education sectors from AL4 to AL3, when the review’s quantitative analysis of risk factors indicated a risk rating for these sectors at AL4 and AL5 respectively.

The eVisa facility for students

33. eVisa is an electronic lodgement and payment service for selected visa classes, including student visas. One of the major benefits identified by DIAC when it introduced eVisa lodgement for all low risk (AL1) offshore and onshore student visa applicants in 2001–02 was faster processing and savings resulting from reduced manual involvement by DIAC staff. DIAC regularly publishes performance information showing the take up rate of eVisa to be around 75 per cent. This statistic gives an incomplete picture of the efficiency impact of eVisa. Applications lodged through eVisa can potentially be electronically processed through to the automatic grant of a visa (an autogrant) requiring no involvement by processing staff, but DIAC does not measure the proportion of eVisa applications that are autogranted. ANAO analysis found that the autogrant rate stood at only 16 and 17 per cent of AL1 grants for the past two financial years, down from over 65 per cent in 2003–04. There is considerable scope for DIAC to more actively monitor the autogrant rate and examine options for achieving an increased number of autogrants.

34. DIAC conducted an evaluation of the eVisa facility for low risk applicants in 2007, but this evaluation was never finalised or formally considered, meaning that the facility officially remains unevaluated more than eight years after its introduction. It is important that the performance of the eVisa facility for the student visa program be properly evaluated, to assess whether the objectives set out at its commencement in 2002 are being achieved and remain appropriate, and whether the facility is meeting the needs of the student visa program in 2011. This would also help to inform DIAC’s plans to move to eLodgement for all visa and citizenship products under its eBusiness Strategy.

35. DIAC also evaluated a trial of eVisa for four higher risk (AL2 4) countries—China, India, Thailand and Indonesia—which was introduced in 2004 and 2005. An initial evaluation of the trial’s implementation was undertaken in 2005 and a full evaluation in 2007, which was updated in 2008. Neither the 2007 evaluation nor its update in 2008 were finalised or formally considered. As a result, the ‘trial’ has never been formally concluded—after nearly seven years in operation—and is overdue for resolution and for an evaluation of its performance in meeting its stated aims.

36. Unlike the AL1 eVisa facility, the AL2 4 eVisa trial requires lodgement of applications through a registered eVisa agent. The terms of the trial set out minimum performance standards for agents to meet, but with the rapid expansion both in the program and the number of registered agents (to over 2500 by 2009), the 2007 evaluation found that there were inconsistencies in the frequency and intensity of audits of agent performance by posts. Its recommendation of a regular auditing regime was not implemented because the evaluation was not finalised.

37. The role of agents in inappropriately promoting student visas as a means to a permanent residence outcome was highlighted in audits undertaken by DIAC some 18 months later during 2009. DIAC reviewed eVisa agent performance as part of the integrity measures announced in August 2009, resulting in the registration of some 300 eVisa agents being cancelled and a new, more stringent Deed of Agreement for eVisa agents being introduced in 2010. Given this history, it will be important for DIAC to effectively implement, manage and resource a regular program of audits and evaluation of eVisa agent compliance with the terms of the new Deed of Agreement.

Program integrity

38. Integrity in the student visa program is provided through a series of layers, from the risk based setting of visa requirements through to onshore compliance activities. The student visa program suffered significant integrity abuse in some caseloads during the period of rapid expansion of the program between 2006 and 2009. As a consequence, a number of integrity measures were introduced between August 2009 and April 2010.

39. One measure was an increase in the financial requirement placed on students to meet living expenses, from $12 000 to $18 000 per annum, to better match the true cost of living in Australia and protect student welfare. Risk assessments prepared by DIAC during the development of this measure identified a risk that students might resort to immigration fraud to meet the increased requirement.[6] While DIAC appropriately identified this as a minor risk for the program as a whole, particular caseloads, such as India, are more sensitive to the changes to the financial requirement than others. Consideration of future student visa integrity measures would benefit from more detailed analysis of the potential impact on significant individual caseloads.

Compliance with mandatory student visa conditions

40. Student visas carry certain mandatory conditions, the main ones being that holders must achieve satisfactory course progress and satisfactory course attendance, and cannot engage in work for more than 20 hours per week while their course is in session. Active monitoring by DIAC of the individual compliance of over 400 000 student visa holders in Australia with these visa conditions is not feasible. Prioritisation of the compliance workload is therefore essential. DIAC’s compliance priorities were last published in its overall Compliance and Integrity Plan for 2007–08. Notwithstanding commitments to update the Plan, this has not occurred. Student visa compliance was one of the priorities listed in the Plan. The lack of an up to date annual compliance plan and supporting planning process means that there has been no process in place to review priorities in the light of subsequent developments. These include the growth of the student visa program, its proportional impact on the compliance workload, and the increase in integrity concerns around the program. In the absence of up to date corporate compliance priorities, DIAC’s state and territory office student integrity and compliance units informally established their own priorities focusing on mandatory visa requirements. DIAC has advised that a new Compliance Priorities Plan is being developed and is planned to be finalised by 2011–12.

41. Students who do not meet mandatory visa requirements for course attendance and progress are reported to DEEWR by their education provider. These reports are automatically passed to DIAC via a systems link between PRISMS and ICSE. Students have 28 days to present themselves to DIAC. If they do not, their visa is automatically cancelled. If they do, their visa is subject to mandatory cancellation unless exceptional circumstances can be demonstrated.

42. There are systemic flaws and vulnerabilities in the regime for automatic and mandatory cancellation of student visas for breaches of the course progress and attendance condition. In particular, the system of automatic cancellation is highly vulnerable to legal challenge, with all automatic cancellations made between May 2001 and December 2009 being overturned by the courts for all but five months of that period, affecting some 19 000 cases. With respect to mandatory cancellation, DIAC officers are regularly exercising discretion not to cancel on the basis of exceptional circumstances or process errors in education providers’ reporting of students. The requirement for DIAC integrity and compliance units to respond to every education provider report of these breaches through a visa cancellation process is resource intensive and restricts their capacity to pursue targeted areas of compliance concern. There would be benefit in DIAC progressing the planned review of the student visa cancellation regime it announced in 2009, and examining the effectiveness and efficiency of the regime in achieving its integrity and compliance objectives. In response to the audit, DIAC advised that it plans to review cancellation processes by June 2012, in consultation with staff, other government stakeholders and the international education industry.

43. Student visa holders have limited work rights. As previously mentioned, students are allowed to work for up to 20 hours per week while their course is in session. There are problems with enforcing this restriction, particularly when allied with the lack of provision in the Migration Regulations for decision makers to exercise discretion. As a result, local practices have been adopted within DIAC to avoid making a cancellation decision for a breach of the 20 hour limit except in the clearest cases. For one area of employment, an informal modification has been made by DIAC officers to the definition of the 20 hour period. The operation of the condition limiting student work rights requires review in relation to evidentiary requirements, decision maker discretion and the impact on compliance resources.

Reporting student attendance and progress via electronic systems

44. Education providers report changes in student circumstances to DEEWR, and these are recorded in PRISMS as Student Course Variations (SCVs). There are 24 SCV codes and 21 of these codes are automatically sent from PRISMS to DIAC’s ICSE system. The two codes concerning the mandatory visa conditions on course attendance and progress immediately convert to a Non Compliance Notice (NCN) in DIAC’s system to trigger visa cancellation action. Others automatically convert to NCNs after 28 days if no action is taken by compliance officers to finalise them. The NCNs in this category were given low priority by DIAC due to resource demands, creating a growing backlog of unactioned NCNs.

45. The backlog of NCNs was not effectively addressed by DIAC following its identification and acknowledgement as a problem in 2006, and the backlog had grown to over 350 000 NCNs by mid 2010, when action was taken to deal with the issue. By the end of March 2011, over 145 000 NCNs had been finalised. While a large number of NCNs in the backlog are trivial and carry no compliance implications, there are potentially serious cases of student non compliance ‘hidden’ within the backlog, particularly in the category of ‘non commencement of course’. The backlog has prevented these cases from being identified and dealt with. DIAC’s current efforts to cleanse the backlog are appropriate, but a long term solution is required which addresses the necessity for each type of SCV to be reported to DIAC and whether they should automatically convert to NCNs.

Cooperation between DIAC and DEEWR

46. The interaction of the student visa program with the international education sector it services creates interdependencies between DIAC and DEEWR that require a collaborative relationship between the two departments.

Electronic data exchange between DIAC and DEEWR

47. DIAC and DEEWR use different information as an identifier for students in their respective systems. The option of moving to a single, unique student identifier was raised in late 2005, and a preferred identifier—a visa grant number and check digit—was developed by a DIAC–DEEWR working party during 2006 and 2007. This option has not been implemented as funding proposals advanced within DIAC on two occasions to implement the necessary systems changes were not successful. In light of the endorsement by COAG of a national student identifier, it would be appropriate for DIAC to re examine and conduct a thorough cost benefit analysis of proceeding with a unique student identifier.

48. In relation to assuring data quality between key business systems, DEEWR performs a daily reconciliation of the number of transactions sent from DIAC’s ICSE system to DEEWR’s PRISM system. However, DIAC does not perform a reconciliation of the information received from DEEWR and assurance that information in its systems is accurate requires manual checking and matching of visa and CoE information between the systems. This process is resource intensive and subject to the effects of changing priorities and resource availability. Pending progress on developing a unique student identifier, it would be desirable for DIAC to implement systematic reconciliations of records sent from PRISMS with the records received into ICSE.

Cooperative structures

49. While there are extensive contact points between DIAC and DEEWR, there are gaps in the structure of the relationship which are inhibiting fully effective collaboration. There is no overarching formal agreement or MOU setting out a framework for cooperation between the departments and the goals that such cooperation should aim to advance. While there is regular interaction in multi agency meetings and whole of government policy forums, forums for cooperation between the two departments are restricted to working level issues. As a consequence, a number of longstanding issues have not been able to be resolved, including addressing the growing backlog of NCNs and the lack of progress on the implementation of a unique student identifier.

50. The Government’s announcement in late 2010 of the establishment of an Interdepartmental Forum on International Education, chaired by DEEWR, is a positive move, but the membership and focus of that Forum is broad. There remains a need for a high level forum between DIAC and DEEWR to maintain a dialogue about their respective strategic policy directions and settings as they affect overseas students, to establish priorities for cooperative activity, and to develop an agreed strategic approach to the interaction of the student visa program and the international education sector.

Summary of agency responses

51. A copy of the proposed report was provided to DIAC. Relevant extracts of the proposed report were also provided to DEEWR. DIAC provided the following summary response:

The Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) has welcomed the opportunity to contribute to the ANAO performance audit Management of Student Visas and agrees with the recommendations made in the report. The ANAO’s report recognises that DIAC’s management of the student visa program has successfully supported the unprecedented growth of one of Australia’s largest export industries and has enabled over a million and a half students to access high quality education in Australia.

The complexity of the student visa program presents a number of challenges for the Department and the ANAO has identified several administrative structures and processes where there is scope for improvements to be made. The Department believes the implementation of the ANAO’s recommendations will strengthen DIAC’s management of student visa processing, student visa compliance and cooperation between DIAC and DEEWR.

52. DEEWR provided the following summary response:

DEEWR appreciates the opportunity to participate in the Performance Audit of Management of Student Visas by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. DEEWR notes that the ANAO has referred to this Department in two of the Report’s recommendations, and that these recommendations are directed to DIAC as the lead agency. DEEWR acknowledges that both Recommendation 5 and 6 are aimed at improving existing management practices and further strengthening current processes in relation to the Student Visa Program.

Footnotes

[1] The next eight in 2009–10, in descending order, were the Republic of Korea, Thailand, Brazil, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, USA, and Saudi Arabia.

[2] Net Overseas Migration is the difference between permanent and long‑term arrivals and permanent and long‑term departures. It includes all long‑term temporary (including student visa holders) and permanent migrants, the majority of whom have work rights.

[3] Senator the Hon Chris Evans, Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, evidence to Senate Estimates Committee (Additional Estimates), Hansard, Canberra, 9 February 2010, p. 29, p 66.

[4] Senator the Hon Chris Evans, (Minister for Immigration and Citizenship), 2010, Australia continues to welcome international students, media release, Parliament House, Canberra, 8 September.

[5] A Non‑Compliance Notice (NCN) is an internal notification within DIAC of a change to a student’s circumstances that is automatically generated by reports received from education providers via DEEWR. NCNs attach to the student’s data record within DIAC’s processing system. Not all NCNs relate to breaches of mandatory visa conditions, which triggers visa cancellation action, but all NCNs prevent further visa grants to the student until the NCN has been examined by DIAC compliance staff and finalised.

[6] In the context of visa applications, immigration fraud refers to the supply of false, misleading or bogus information or documents by a visa applicant. In the student visa caseload, the majority of immigration fraud relates to financial documentation supporting the applicant’s claim to meet the financial requirements of a student visa. This includes, for example, loan documentation, bank deposits, income tax returns and overdraft statements.