Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Migration to Australia — Family Migration Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Almost 28 per cent of Australia’s population is born overseas. The Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) administers Australia’s permanent Migration Program (migration program).

- The Family Migration Program (Family program) makes up around 30 per cent of visa places made available by the government under the migration program each year.

- Effective management of the migration program supports achievement of the economic and social objectives of the government’s migration policy.

Key facts

- During the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–20 to 2020–21), lodgements of Family program visa applications decreased by 13 per cent in 2019–20 and 10 per cent in 2020–21.

- In 2021–22, the Partner visa category accounted for 90.3 per cent of Family program visas granted. The number of applications in the Partner visa backlog reduced from 96,361 to 64,111 between 2019–20 and 2020–21.

What did we find?

- Home Affairs’ arrangements for the design and delivery of the Family program are largely effective.

- The department’s policy advice to the government to support the design of the Family program is largely effective.

- While the department has established appropriate arrangements for the delivery of the Family program, its implementation of these requires strengthening to ensure consistent and timely provision of family visa services.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made six recommendations aimed at improving Home Affairs’ policies and governance for the management of the visa caseload and strengthening approaches to measuring operational efficiency.

$1.4b

Home Affairs expenditure on the delivery of all visas from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

51,082–80,300

Range of available places under the Family program between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

250,484

Number of Family program applications on hand at 27 January 2023.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Almost 28 per cent of Australia’s population is born overseas.1 Since the 1970s Australia’s migration programs have been based on a universal, non-discriminatory visa system.2 Provided an individual meets the criteria to lodge a valid application, they can apply for a visa, regardless of their gender, race, nationality, ethnicity or religious belief.

2. The permanent Family Migration Program (Family program) provides for the migration of family members of Australian citizens, Australian permanent residents, or eligible New Zealand citizens.3 The Partner visa category is the largest component of the Family program, accounting for 90.3 per cent of Family program visas granted in 2021–22.4

3. The Migration Act 1958, Migration Regulations 1994 and Ministerial Instruments provide the legislative framework for Australia’s permanent Migration Program (migration program). The migration program is administered by the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department). Family program visas are processed in four Visa and Citizenship Offices located in Australia and 25 Australian overseas missions.5

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Effective management of the migration program supports achievement of the economic and social objectives of the government’s migration policy. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on the effectiveness of Home Affairs’ management of the Family program.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s management of family-related visas. To form a conclusion against the proposed objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Is the Family Migration Program effectively planned?

- Are Family Migration Program application lodgement and assessment processes effectively implemented?

Conclusion

6. Home Affairs’ arrangements for the design and delivery of the Family Migration Program are largely effective. Planning for the delivery of the program provides a suitable basis for meeting government objectives. There are shortcomings in implementation which impact on the department’s effectiveness and efficiency in delivering visa services. Aspects of policy and governance require further development and documenting to ensure performance in visa processing operations is appropriately monitored and evaluated.

7. Home Affairs provides largely effective policy advice to the government to support the design of the annual Family Migration Program, but consultation processes do not directly engage those affected by proposals. The department’s business and risk planning largely support delivery of the program to meet government objectives.

8. While Home Affairs’ arrangements to enable the delivery of the Family Migration Program are appropriate, its implementation of these requires strengthening to ensure the consistent and timely provision of family visa services. The department lacks clear frameworks for measuring efficiency for the purposes of improving business outcomes and systematically managing aged applications.

Supporting findings

Planning

9. Home Affairs’ policy advice responds to government priorities and is largely informed by appropriate evidence. Submissions generally do not report to government on the outcomes of consultations conducted with stakeholders of family migration. Advice to support the review of the department’s performance against annual Family Migration Program planning levels is not complete in its analysis of effectiveness and efficiency. (See paragraphs 2.3–2.28)

10. Home Affairs conducts appropriate implementation planning and has effective business planning processes to guide the implementation of the Family Migration Program. There is a need for the department to more clearly set out its planning for the delivery of demand-driven programs, including for managing increases in demand for visa places. (See paragraphs 2.29–2.64)

Implementation

11. Website information to assist applicants to lodge applications under the Family Migration Program is relevant and conveyed in plain language. Routine call centre and complaints reporting does not provide sufficient detail and analysis to support improvements to the delivery of the Family Migration Program. The department determines whether an application is invalid quickly, but communication with clients whose applications move to further stages of assessment is limited. (See paragraphs 3.2–3.47)

12. Home Affairs’ case allocation capabilities provide a basis for the effective and efficient management of its caseload. Its processes support it to meet processing objectives and changes in priority. Policies governing case allocation practices require strengthening to ensure the department can demonstrate conformance with all policy requirements. There is a need for the department to address inconsistencies in its approach to identifying and assessing risk within Family Migration Program visa categories. (See paragraphs 3.48–3.98)

13. Home Affairs’ business process and quality management frameworks establish a partly effective basis for gaining assurance over the processing of visa applications. There is scope for Home Affairs to strengthen its analysis of efficiency in family visa processing. While the department collects and reports efficiency-related information, it has not established a consistent set of metrics as a basis for improving efficiency within the Family Migration Program. (See paragraphs 3.99–3.148)

14. Home Affairs has appropriate business and quality review controls to support decision-making and the notification of outcomes to Family Migration Program visa applicants. Processes for improving the quality of decision-making require strengthening to include a clear focus on the implementation and monitoring of improvements. There is a need for guidance to support the timely handling of notifications and cases remitted to the department for review. (See paragraphs 3.149–3.167)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.34

The Department of Home Affairs establish processes for capturing meaningful client feedback from all sources to enable it to identify opportunities to improve the provision of service to clients of the Family Migration Program.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.68

The Department of Home Affairs ensure its prioritisation and risk-tiering processes are fit for purpose and consistently applied within Family Migration Program visa types, irrespective of the location of processing.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.91

The Department of Home Affairs develop an overarching policy and governance framework for its case allocation model to guide allocation decision-making and ensure that this supports effectiveness and efficiency in the handling of Family Migration Program visa applications.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.135

The Department of Home Affairs establish a standard set of monitoring and evaluation metrics to support analysis and continuous improvement in the efficiency of Family Migration Program visa processing.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.146

The Department of Home Affairs establish processes to identify, analyse and remediate potential processing inactivity to support the improvement of efficiency in its business process for finalising Family Migration Program visa applications.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.165

The Department of Home Affairs establish systematic processes for detecting and remediating aged cases across all parts of the Family Migration Program caseload to ensure applications are appropriately finalised, wherever feasible.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

15. The proposed audit report was provided to Home Affairs. The full response is included at Appendix 1. The summary response is reproduced below.

The Department agrees with the broad direction of the recommendations, as part of its ongoing efforts to strengthen governance, and acknowledges the benefits of more clearly identified standards and oversight mechanisms to deliver visa programs to a high standard. The Department seeks to continuously improve the quality of its client service delivery to achieve better outcomes for Australians and for its diverse stakeholders.

The Department notes that a number of the ANAO’s recommendations are dependent on Information Communications Technology (ICT)/systems functionality not currently available. Implementation requires investment in improvements to ICT capability to have a marked impact on the efficient and effective delivery of all visa programs. Some recommendations focus on parts of the overall visa assessment process where substantial process or efficiency improvements may be difficult to achieve, especially given the limitations of existing visa processing systems. The Department continues to explore options to improve visa processing and associated reporting within the constraints of existing ICT systems, while capitalising on opportunities to improve these systems when they arise.

The report notes the complexity of migration legislation and the end-to-end visa process. Decision making on subjective matters such as familial relationships are by nature complex and have varying degrees of compelling and compassionate elements. The Department is well progressed implementing a range of improvements which aim to strengthen the efficiency and effectiveness of Australia’s family visa programs, and the management of risk.

16. Appendix 2 notes an improvement to policy and program management observed by the ANAO during the audit.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Policy/program design

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Australia’s migration program

1.1 Almost 28 per cent of Australia’s population is born overseas.6 Since the 1970s, Australia’s migration programs have been based on a universal, non-discriminatory visa system.7 Provided an individual meets the criteria to lodge a valid application, they can apply for a visa, regardless of their gender, race, nationality, ethnicity or religious belief.

1.2 The permanent Family Migration Program (Family program) provides for the migration of family members of Australian citizens, Australian permanent residents, or eligible New Zealand citizens.8,9

The permanent Migration Program

1.3 Australia’s permanent Migration Program (migration program) refers to the number of permanent and provisional family and skilled visa outcomes for each program year.10 The government determines the planning level, size and composition of the migration program each year as part of the Budget process.11 The Family program has historically made up 30 per cent of the total migration program planning level.12

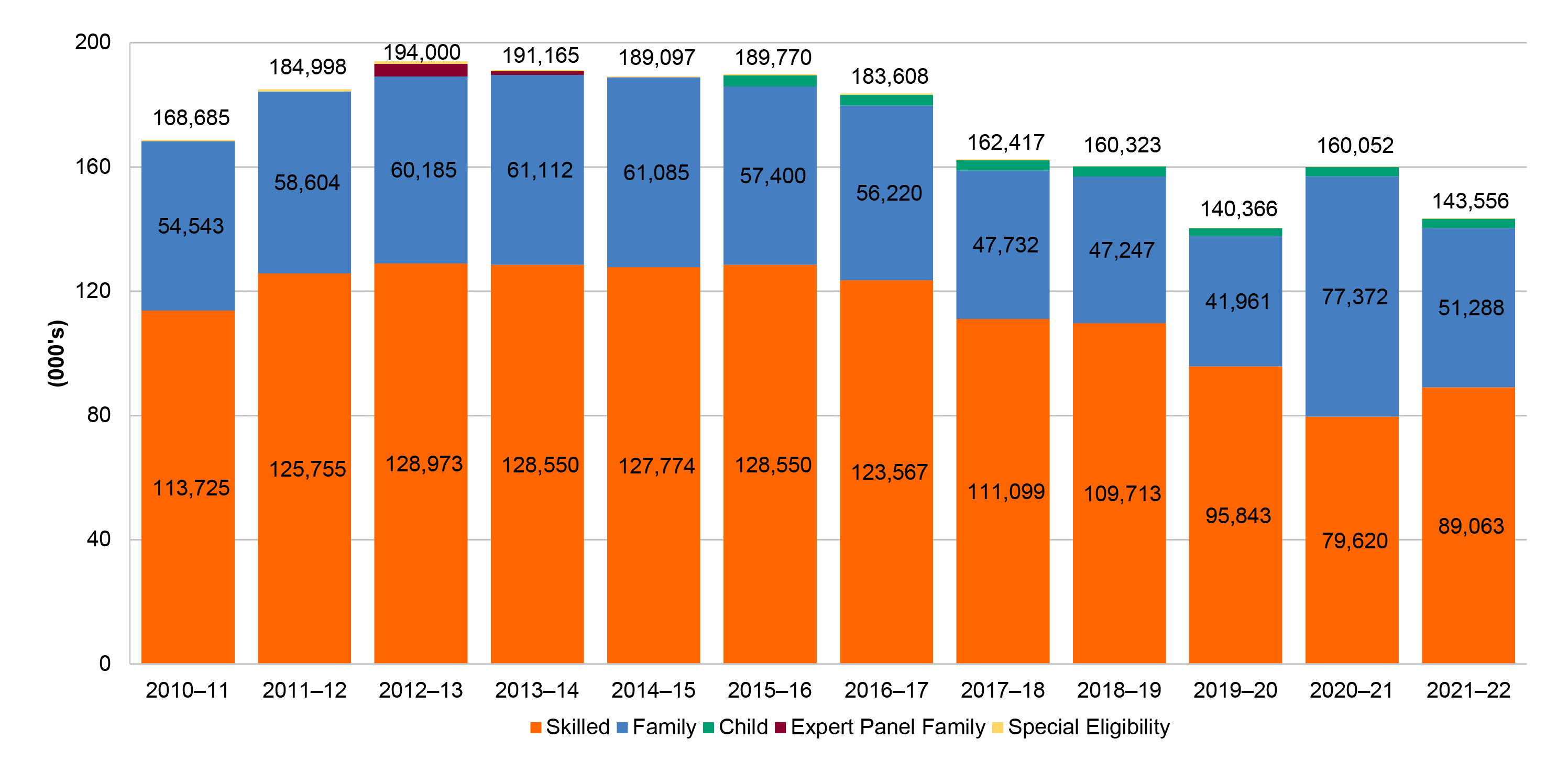

1.4 The Family program and Skilled Migration Program (Skilled program) together account for approximately 98 per cent of visas granted under the annual migration program.13,14 Appendix 3 shows the number of permanent visas granted each year from 2010–11 to 2021–22.

1.5 Family visas are organised into four categories that allow a family member to sponsor another family member to live with them in Australia.

- Partner visas sponsor a spouse, de facto or prospective partner.

- Child visas allow parents to sponsor their dependent or adopted child or orphans.

- Parent visas enable parents to be sponsored through either Non-Contributory or Contributory Parent visas.15

- Other Family visas enable the sponsoring of carers, remaining relatives or aged dependent relatives.16

1.6 The Partner visa category is the largest component of the Family program. Partners of Australian residents accounted for 90.3 per cent of Family program visas granted in 2021–22.17 Applicants apply for a temporary and permanent visa at the same time, also referred to as a first stage Partner visa and second stage Partner visa, respectively.18 Appendix 4 contains a full list of family-related visas.

The COVID-19 pandemic

1.7 As part of its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government restricted travel across Australia’s border from March 2020 to February 2022.19 This led to a net outflow of 85,000 migrants in 2020–21.20

1.8 Demand for Partner visa places in the migration program declined in 2019–20 and 2020–21.21 In addition, around 20,000 fewer temporary and permanent visas were granted in 2019–20 than in 2018–19 (a decline of 12 per cent).22

1.9 The government introduced measures to manage the impacts of COVID-19 on the migration program to take account of fewer skilled migrants and reduced visa processing operations (both onshore and offshore).23 This included increasing the number of Partner visas available under the Family program to 72,300 places in 2020–21 and 2021–22.24 The number of family visas issued in 2020–21 increased to almost half of all visas granted under the permanent migration program, an increase of 84 per cent from 2019–20 and the largest number of places since 1987–88.25,26

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.10 Effective management of the migration program supports achievement of the economic and social objectives of the government’s migration policy.27 This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on the effectiveness of Home Affairs’ management of the Family program.

Administration of the migration program

Administrative arrangements

1.11 Australia’s migration program is administered by the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department) through the Immigration Group (IG). Home Affairs’ expenditure for the delivery of visas was $1.4 billion between 2018–19 and 2021–22. Funding allocated to the department for the Visas program is $339.4 million in 2022–23.28 In addition to this, the government allocated departmental funding of $38.2 million over two years from 2022–23 to increase Home Affairs’ visa processing capacity, including through the recruitment of an additional 500 staff.29

1.12 Funding allocations through appropriations include a fixed amount and a variable funding amount. The variable funding amount is based on a unit price per visa finalisation and an estimate of the expected number of visa finalisations. The total amount is adjusted at the end of the financial year, if the number of visa finalisations varies from that planned for in the Budget.30

1.13 The main divisions in IG responsible for the delivery of the migration program are:

- Immigration Policy, Integrity and Assurance division (IPIAD), responsible for the development of migration policy and advice to government on the design of the migration program, and assurance over program activity; and

- Immigration Programs Division (IPD), responsible for the delivery of the migration program (temporary, skilled and family components).

1.14 Family Migration Program visa applications are processed in four Visa and Citizenship Offices located in Australia and 25 Australian overseas missions.31 The average staffing level for the migration program decreased from 2015–16 to 2020–21.32 In 2021–22, there were 1959 staff allocated to support temporary and migration visa processing functions, with 1140 staff located in Australia and 819 operating offshore.33

1.15 The department relies on two main systems to process visas. Its Integrated Client Service Environment (ICSE) system is used to process Partner and citizenship visa applications which are lodged online. Other visa applications for Family program visas, which can only be lodged using paper application forms, are processed in ICSE and its Immigration Records Information System (IRIS). In November 2022, Home Affairs advised the ANAO that:

IT systems remain a considerable impediment to the efficient and effective delivery of migration programs, particularly for family visa programs. Current systems are not what would be considered acceptable standards for modern service delivery, noting core systems are over 30 years old and several programs still require paper-based visa lodgement.

Some impediments identified by the department are the complexity and poor integration of its ICT systems which result in dispersed client information and inadequate support for decision-makers.34

Legislative framework

1.16 The Migration Act 1958, Migration Regulations 1994 and Ministerial Instruments provide the legislative framework for Australia’s migration program. The Act sets out requirements for the administration of visa applications and the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs’ (Minister) obligations and their powers, which may be delegated.35 Key provisions of the Act that relate to the limits to be applied to the granting of visas include36:

- section 85 of the Act — allows the Minister to determine the maximum number of visas which may be granted in each financial year in specified visa classes, including Parent and Other Family visas;

- section 87 of the Act — prevents a cap applying to the Partner or Child visa categories37;

- section 51 — allows the Minister to determine the order of consideration for the processing of visa applications; and

- section 499 — enables the Minister to give written directions to a person or body regarding the performance of functions, or the exercise of powers, under the Act. An example of a Direction given in accordance with section 499 is Ministerial Direction 102 which relates to the order for considering and disposing of family visa applications.

1.17 Except where otherwise directed by the Minister, visa applications should be processed in the order of the date on which they were lodged.38 There is also an implied obligation under the Act for all visas to be considered and disposed of within a reasonable time.

Reviews of the migration program

1.18 Reviews and audits of Home Affairs’ provision of visa and citizenship conferral services have recommended improvements to the effectiveness and efficiency of its operations.39 The first recommendation made by the Senate in its March 2022 Inquiry report on visa processing was for the department to:

develop a long-term strategy to update its system for the processing of visas; to improve its efficiency, to reduce its complexities, reduce waiting times substantially, and to provide greater transparency for applicants.40

1.19 Submissions to the Senate Inquiry and citizen contributions to this audit indicate that key areas of stakeholder concern are: extended processing times for some types of visas; lack of communication during the visa processing period; inconsistencies between processing locations; and management of the demand-driven Child and Partner visa programs.

1.20 In September 2022, the government announced that it would conduct a strategic review of the purpose, structure and objectives of Australia’s migration system, with the outcomes to be provided to the government by the end of February 2023.41,42 Terms of Reference for the review state that a new migration strategy would be informed by a ‘review of the current visa framework … and the processes and systems that support the administration of that framework’.43 The department has established an Immigration Reform Taskforce and appointed an Associate Secretary to head this and its Immigration Group.

Processing times

1.21 The length of time taken to finalise a visa application can vary depending on the specific circumstances of the applicant and a range of factors. These include the number and completeness of applications received; level of demand and the number of places the government allocates to a program each year; and government priorities for processing (the Minister’s priorities are set out in a direction issued to the department, see paragraphs 3.80–3.85).

1.22 Home Affairs publishes the period of time taken to finalise a percentage of cases (25, 50, 75 and 90 per cent of cases) on its website to provide indicative timeframes for visa processing, based on cases recently finalised.44 Appendix 5 shows the number of days to finalise 75 per cent of applications for Family program visa categories for 2018–19 to 2021–22 (see also paragraph 3.23–3.29).

Caseload

1.23 Wait times are influenced by the size of the existing caseload of visa applications. Factors contributing to the size and profile of the caseload are: the number of places allocated annually to a permanent visa program; the volume, completeness and complexity of applications lodged; the directed priority of processing; and the allocation of processing resources.

1.24 Home Affairs refers to visa applications which are being assessed as the ‘application pipeline’.45 Appendix 6 shows the caseload for Family Migration Program categories for 2018–19 to 2021–22. At 27 January 2023, the Family program reported 250,484 on hand applications.46

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.25 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s management of family-related visas. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Is the Family Migration Program effectively planned?

- Are Family Migration Program application lodgement and assessment processes effectively implemented?

Audit scope

1.26 The audit focused on Home Affairs’ administration of the Family program, including the Partner, Child, Parent and Other Family visa categories. The audit did not examine the role of migration agents or arrangements for the investigation of visa fraud and integrity.

Audit methodology

1.27 In conducting the audit, the ANAO:

- examined the department’s policy documents, procedures and operational reports;

- conducted meetings with departmental staff, including staff in the Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth offices, as well as Dubai, Amman, Ankara, New Delhi and London offices;

- conducted walk-throughs of relevant visa processing systems; and

- considered citizen contributions to the audit.

1.28 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $630,000. Team members for this audit were Judy Lachele, Glen Ewers, Edwin Apoderado, Rebecca Helgeby, Jessica Kanikula, Dr Cristiana Linthwaite-Gibbins, Michael Dean, Stuart Atchison, Song Khor, Tex Turner, Zhiying Wen, and Alex Wilkinson.

2. Planning

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Home Affairs’ planning for the design and delivery of Australia’s Family Migration Program is effective.

Conclusion

Home Affairs provides largely effective policy advice to the government to support the design of the annual Family Migration Program, but consultation processes do not directly engage those affected by proposals. The department’s business and risk planning largely support delivery of the program to meet government objectives.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO identified three opportunities for improvement. It suggested that Home Affairs strengthen its annual reporting to government to include advice on the outcomes of community consultation and its performance in managing the visa caseload. The ANAO also suggested that divisional business plans clearly link operating risks and controls to the sources of risk affecting the delivery of the migration program.

2.1 Advice to government on Australia’s Family Migration Program (Family program) should be based on evidence and include information about the views of those affected by policy proposals and the program’s implementation.47

2.2 Effective planning of the Family program better prepares Home Affairs to deliver against priorities set by government and meet the intent of its policies. Planning should be complemented by appropriate governance arrangements to ensure effective implementation of the program.

Does the department provide relevant and appropriate advice to the government?

Home Affairs’ policy advice responds to government priorities and is largely informed by appropriate evidence. Submissions generally do not report to government on the outcomes of consultations conducted with stakeholders of family migration. Advice to support the review of the department’s performance against annual Family Migration Program planning levels is not complete in its analysis of effectiveness and efficiency.

Home Affairs’ support to the government’s decision-making

2.3 The government determines the permanent migration program each year as part of the Budget process. It considers advice and options for granting Skilled and Family program visas for the next financial year set out in an annual submission.

2.4 The government sets an overall limit (‘planning level’ or ‘ceiling’) and specifies the number of places for each of the visa categories within the limit. From 2012–13 to 2018–19, the total number of visas available under the permanent migration program was 190,000.48 This level was reduced to 160,000 between 2019–20 and 2021–22. On 2 September 2022, the government announced a planning level of 195,000 for 2022–23.49

Consultation processes

2.5 Key considerations in government decision-making on migration include: population trends; its social and economic policy objectives; state and territory priorities; stakeholder advice; and public opinion. Home Affairs engages with its minister throughout the development of the annual submission. It also provides extensive information about the status and key issues affecting the visa caseload through: weekly dashboard reports; ‘deep dive’ briefings; and ministerial briefings.

2.6 The department proposes an annual plan to the Minister for consulting with stakeholders to inform the development of the submission. This consultation process involves:

- seeking the views of state and territory governments;

- facilitating roundtable discussions with industry stakeholders and academics;

- obtaining advice from Australian Government entities on the implications of migration policy and program activity for their portfolio; and

- releasing a discussion paper inviting submissions from the public.

2.7 The department does not engage directly with community representatives or organisations.50 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that it brings its public discussion paper to the attention of community networks through its Regional Directors and Community Liaison Officers.51 Basic details of meetings are recorded in spreadsheets, but there is no specific record of consultation on Family program migration proposals.52 Submissions from members of the public in response to the department’s discussion paper were recorded and analysed for the 2021–22 migration program.

2.8 While the main focus of consultation is the Skilled program, some advice on levels of support for family migration is included in annual submissions.53 Home Affairs advised that it takes community feedback into account when it develops planning options for the government.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.9 There is scope for the department to explicitly set out how its advice reflects consideration of community views. |

Alignment with policy priorities

2.10 Entities should ensure that proposals put to government relate to the delivery of its priorities. The government’s priorities for the delivery of the visa program were adjusted in 2017 and 2022.

2.11 In 2017, the government considered a 2016 report by the Productivity Commission on Australia’s migrant intake. The report recommended improving advice to the government on annual migration by including consideration of Australia’s capacity to ‘absorb’ levels of migration.54 In response, the department provided advice to the government to support:

- engagement with state and territory governments on population planning55;

- its consideration of a lower planning level to reduce pressure on infrastructure and essential services, particularly in major cities; and

- its understanding of the net economic outcomes delivered by migration.

2.12 In 2018, the department proposed to provide more comprehensive advice in its annual submission on the relative benefits and costs of migration from a 10-year perspective. This included drawing on a new costing model (developed by the Treasury) and enhanced consultation across government.56 Migration proposals establish visa grant levels for a single financial year and have not incorporated the proposed 10-year perspective.

2.13 The department provided advice to support the government’s decision-making on the 2022–23 migration program in August 2022, including presenting options aimed at addressing continuing workforce shortages and the longer-term implications of Australia’s ageing population.57 Advice to government since August 2022 has supported the development of a longer-term policy framework to guide annual decision-making.

Advice on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic

2.14 Home Affairs prepared appropriate advice to the government to reflect conditions for migration created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government agreed to the department’s proposals:

- a temporary shift from a 70–30 per cent split to a 50–50 per cent split between the Skilled and Family programs for 2020–21 to take account of reduced demand for skilled visas; and

- a return to a 70–30 per cent split between the Skilled and Family programs in 2021–22 to respond to critical labour shortages.

Setting planning levels

2.15 Decisions on the size and composition of the migration program enable the government to implement its migration policy. The department’s advice to government includes information about the economic and social outcomes expected from its delivery against agreed planning levels.

2.16 In 2016–17, the government agreed to a proposal to adopt the term ‘planning ceiling’ to establish an upper limit rather than a minimum number of visas to be finalised by the end of the financial year. In 2018–19, the department advised the government to reduce the planning ceiling for the following year from 190,000 to 150,000 to better reflect its capacity to process visas.58,59 The government agreed to a planning level of 160,000, with the original level to be reinstated in 2023–24.

2.17 The use of annual planning ceilings may increase uncertainty about the actual number of visas likely to be granted by the end of the year, reducing the government’s ability to determine if its policy and fiscal objectives will be achieved.60 Advice to government should indicate the department’s confidence in being able to achieve targets and deliver against its policy objectives. Home Affairs’ advice to support the government’s October 2022–23 Budget addressed these limitations. It included appropriate information about the likely level of risk associated with each of five planning ceiling options presented for the delivery of the migration program.61

Advice on program implementation

Achievement against planning levels

2.18 Analysis of past performance can help set appropriate expectations and inform decisions about delivery going forward. From 2016–17, the department’s delivery against the overall planning level of 190,000 (for both Family and Skilled programs) began to decline.62 Figure 2.1 shows the number of Family program visas granted from 2014–15 to 2021–22 compared with the number of places made available by the government for that year. It also shows the number of lodgements and size of the caseload during this period.

Figure 2.1: Home Affairs’ delivery against planning levels for the Family Migration Program from 2014–15 to 2021–22

Notes: The figure includes Child visa places, as the number of Child visas granted count toward the total migration program outcome. The Family program planning level in 2014–15 was 61,085. Between 2015–16 and 2017–18 it decreased to 60,885. In 2018–19 the planning level was set at 60,750. This was reduced to 51,082 in 2019–20, before increasing to 80,300 in 2020–21 and 70,300 in 2021–22. Public migration program statistics and reports are available on the Home Affairs website at https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/visa-statistics/live/migration-program [accessed 19 January 2023].

Source: ANAO analysis of public information and data provided by Home Affairs.

2.19 Achievement against Family visa planning levels declined from 2016–17 to 2019–20, and in 2021–22.63 As the government generally requires the department to maintain a 30–70 per cent division between the number of Family and Skilled program places granted, the decline impacted both programs proportionately.

2.20 The temporary shift to an even split between the Skilled and Family programs for the 2020–21 migration year increased the number of available Family visa places by 57 per cent compared with the previous year.64 The department achieved the planning levels for the Family program and the Skilled program.

2.21 In 2021–22, Home Affairs delivered 143,556 places against an overall ceiling of 160,000.65 In this year, 10,000 Partner visa places were transferred from the Family to the Skilled program. This resulted in a reduction in the planning level for the Family program from 80,300 to 70,300 places, with the number of places available under the Partner visa program reduced from 72,300 to 62,300 places. The department delivered 77 per cent of the revised planning level for the Family program and 74 per cent of the Partner program level.66

Analysis of performance

2.22 The department’s advice to government from 2016–17 to 2019–20 did not detail the downward trend in achievement against planning levels or analyse its implications for the government’s objectives. Since 2020–21, Home Affairs’ advice to the government has provided information about its achievement of planning levels. This is referred to as a ‘reconciliation’ and consists of a table which shows the number of visa places made available by the government and the number granted for each of the Skilled and Family program visa categories.67 Since 2019–20, the department has cited: higher numbers of high-risk cases; its increased attention to older and more complex applications; and increased rates of refusals as reasons for not achieving expected levels of finalisation.68,69

2.23 As part of its proposal for the 2021–22 migration program the department outlined the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the rate of visa application lodgements and its processing capacity in 2019–20 and 2020–21. The department revised down its projections for delivering against the total planned migration outcome by the end of the program year. As reasons for this, the department pointed to a reduced rate of lodgement due to fewer migrants entering Australia and a large number of complex applications which could not be readily drawn on to meet the planning level.70

2.24 The department’s advice supporting the March 2022 migration program focused on addressing the government’s objectives for economic recovery following the reopening of Australia’s border. It did not provide information about achievement against planning levels to that point. No explanation was provided in advice to the government in August 2022 of underachievement in the previous year.71

Capacity to implement government objectives

2.25 Home Affairs’ advice to government has commented on: factors affecting processing times, such as application risk; rates of lodgement; and the effect of limits on visas. When advising the Minister on the 2022–23 migration program in March 2022, the department advised that increasing the size of the program would affect visa processing times. It also identified processing inefficiencies relating to its ICT infrastructure (see paragraph 1.15).

2.26 In developing its advice, the department seeks information from visa delivery offices to gauge their capacity to deliver proposed planning levels. It is not evident that advice to the government is based on a systematic approach to analysing processing capacity and that this materially informs planning levels. Information about the efficiency of Home Affairs’ operations would enable the government to better understand the department’s ability to meet its expectations.72 While the department describes a range of activities aimed at increasing efficiency in its advice to government, it does not provide information about its actual level of efficiency.

2.27 Since April 2021, the department has provided information about the number of unfinalised applications (the caseload) for each visa category of the Skilled and Family programs as part of reporting on its achievement of set planning levels (see paragraph 2.22).73 This reconciliation is not accompanied by an analysis of key factors affecting the size and age of visa caseloads.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.28 Home Affairs could provide complete information to the government relating to the department’s performance against planning levels and its management of the visa caseload, as part of its reconciliation of performance in delivering the annual migration program. |

Does the department’s implementation planning provide a sound basis for achieving the government’s policy and program objectives?

Home Affairs conducts appropriate implementation planning and has effective business planning processes to guide the implementation of the Family Migration Program. There is a need for the department to more clearly set out its planning for the delivery of demand-driven programs, including for managing increases in demand for visa places.

Planning for the delivery of the migration program

Strategic planning

Corporate Plan

2.29 An entity’s corporate plan is its primary planning document.74 Corporate plans are developed at the beginning of an annual reporting cycle to set out how an entity will achieve its purposes and success will be measured.75

2.30 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the purposes of a Commonwealth entity are defined by its objectives, functions or role. The description of purposes and activities in the corporate plan is the basis of meaningful performance reporting.76 The plan should outline how the entity’s activities will lead to the achievement of its purposes.

2.31 Purpose 2 of Home Affairs’ Corporate Plan is to ‘support a prosperous and united Australia through effective coordination and delivery of immigration and social cohesion policies and programs‘.77 Two key activities contribute to Purpose 2, the first of which is the ‘effective design, delivery and assurance of immigration programs’.78 This activity, when carried out effectively, is intended to directly support the creation of ‘a prosperous and united Australia’.

2.32 For 2022–23, Home Affairs has established four performance measures, expressed as targets, which relate to activities relevant to the design, implementation and evaluation of the permanent migration program (see Table 2.1).79

Table 2.1: 2022–23 Home Affairs Corporate Plan

|

Activity 2.1: Immigration and Humanitarian Programs |

||

|

Measure: 2.1.1: Effective design, delivery and assurance of immigration programs |

||

|

# |

Phase |

Targets |

|

14 |

Design |

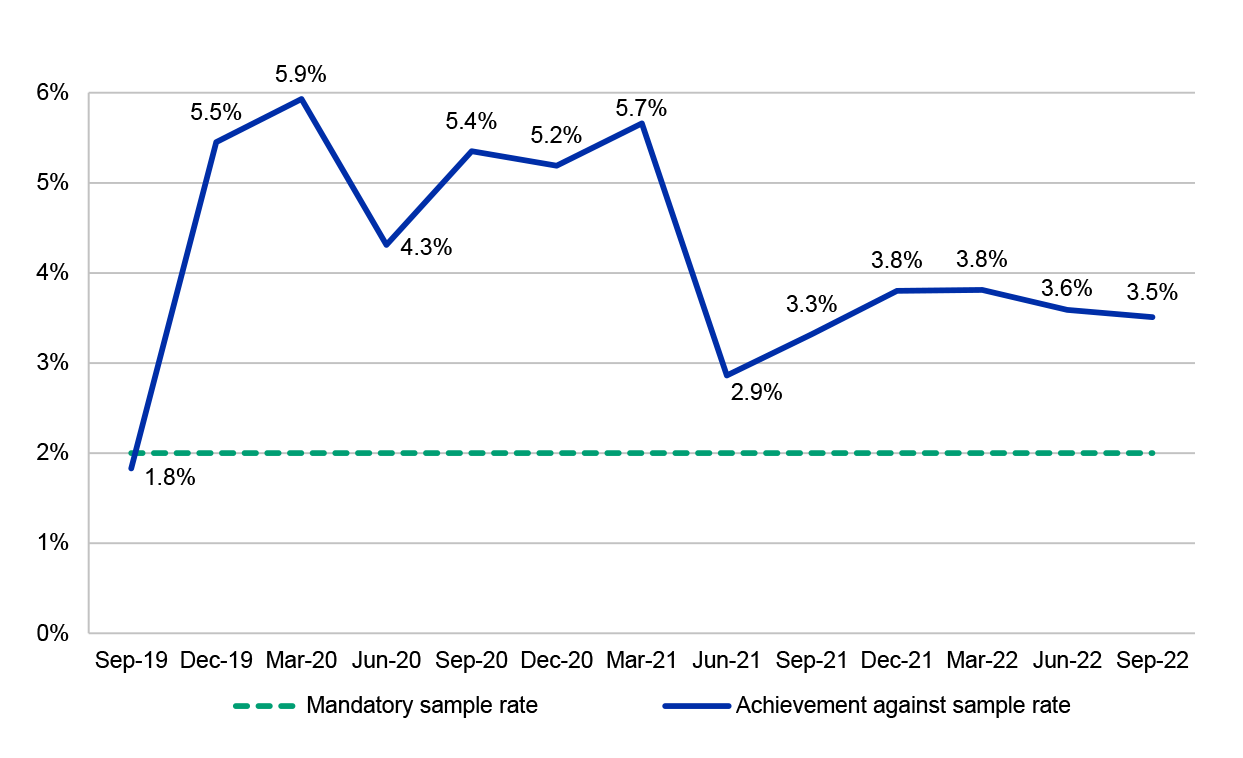

70 per cent of surveyed public and state government stakeholders are satisfied with the consultation process used to develop policy advice for government on the Annual Migration Program (size and composition). |

|

15 |

Implementation |

The Migration Program is delivered within the planning ceiling and is consistent with priorities set by the government. |

|

16 |

Implementation |

Visa processing times (from application to point of finalisation) for new applications are reduced. |

|

17 |

Assurance |

The proportion of visa and status resolution decisions subject to quality assurance activities, and the proportion of errors identified through these activities, is consistent with the pre-determined sample size and error rate set by programs across all locations. |

Source: Department of Home Affairs Corporate Plan 2022–23.80

Business planning

2.33 Internal planning ensures there is a shared understanding of how the government’s strategic priorities are to be achieved through the department’s management and service delivery approach. Divisions within the Immigration Group (IG) develop business plans as part of the department’s annual planning cycle. The plans describe the division’s operating environment and set out its budget, work priorities and responsibilities.

2.34 Immigration Programs Division (IPD) is the lead division responsible for delivering the permanent and temporary immigration programs. Its business plan for 2022–23 describes government objectives and operational priorities. Business plan objectives include ‘efficient and accurate visa decisions, at a pace and volume that will see reductions in on-hand caseloads and improvements in visa processing times’, as well as specific and measurable targets.81

2.35 The ANAO’s review of business planning indicates divisional priorities were aligned with corporate plan objectives. Effective business planning for the migration program relies on clear understandings of how elements of the program contribute to the achievement of the Group’s objectives. Home Affairs advised the ANAO in October 2022 that it had commenced work on establishing a program management framework to clarify roles, responsibilities and functions within the Group. This is also intended to support standardising operational policies and processes and its management of stakeholder engagement, program quality, risk and performance across the migration program.

Operational planning

Branch level planning

2.36 Key branches responsible for delivering the migration program are shown in Figure 2.2.82 Until 2020–21, the Skilled and Family programs were administered by a single branch.

Figure 2.2: Key areas responsible for managing the migration and temporary visas program

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by Home Affairs.

2.37 The Family program is managed as a sub-program by the Family Visas Branch. Branches are not required to have a business or sub-program plan. To demonstrate program planning, Home Affairs provided the ANAO with a document produced by the Family Visas Branch in May 2022 to support a ‘Deep Dive’ discussion of the 2021–22 Family program. The document provided information on the status of program delivery, including:

- the number of lodgements, finalisations, grants and refusals;

- visa processing times;

- citizenship country of visa applicants; and

- the age of cases (up to and greater than 24 months).

2.38 The deep dive process indicates the branch identified processing priorities and analysed delivery issues and constraints.

Network planning for delivery

2.39 The ANAO examined Home Affairs’ processes for delivering directions set by the government and management based in Canberra through the visa processing network. Since 1 March 2023, Regional Directors have been accountable to the new position of Group Manager Immigration Operations for achieving processing objectives.

2.40 Home Affairs’ national office in Canberra consults with Regional Directors when developing the department’s annual submission to government. Following the government’s decision on the migration plan, delivery offices are consulted on the allocation of processing targets. Regional Directors and their respective regions, comprising several offices each, are responsible for planning and managing local resources to achieve their targets. The Immigration Network Operations and Governance Branch monitors the allocation of resources over the program year, and may request changes to the distribution of resources to manage delivery of the division’s priorities.

2.41 In meetings with the ANAO, staff in processing offices indicated that operational planning is undertaken after the size and composition of the annual program has been determined.83 This includes: developing processing strategies which consider their existing caseload; operating conditions; and staffing numbers and capabilities. Allocations may be adjusted at different points in the year to reflect changes in processing capacity.

2.42 The ANAO identified activities which support day-to-day operational planning and alignment of activity with business objectives:

- communication between the division head of Immigration Programs and Regional Directors, and a reporting line back to this position;

- the use of a Community of Practice forum to discuss planning issues and share information about operations and performance;

- centralised allocation of cases to delivery offices and on-going monitoring of allocations to offices;

- appointment of officers responsible for ensuring delivery against each visa program for each office84; and

- regular monitoring of delivery against planning priorities, targets and efficiency measures.

2.43 The Immigration Network Operations and Governance Branch (INOG) regularly provides advice to the Minister and the Executive on the department’s progress in achieving planning targets. It also distributes information to policy and delivery managers on visa processing activity across delivery units.

Planning to manage demand — Child and Partner visa programs

2.44 Section 87 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act) exempts Partner and dependent Child visa applicants from limits imposed under section 85. However, in determining the size, composition and resourcing of the annual migration program, the government establishes an administrative upper limit (total migration ceiling). Planning for the delivery of the Child visa program considers the ceiling set for the migration program, and the number of visas granted count toward this.

2.45 Since 2015–16, the government has determined that the Child visa program is to be managed on a demand-driven basis. The department establishes planning estimates as part of its budget proposal and for the purposes of allocating processing resources. Annual planning estimates proposed to government should broadly align with the level of demand for Child visa places.85 Figure 2.3 shows the planning estimates and the number of visa applications lodged and on hand from 2014–15 to 2021–22.

Figure 2.3: Child visa program planning levels and outcomes compared with lodgements and on hand between 2014–15 and 2021–22

Note: Only visas granted contribute to the program year outcome. The outcome does not include refused or withdrawn applications.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by Home Affairs.

2.46 Figure 2.3 indicates that planning proposals have not reflected demand for Child visas, except during the COVID-19 pandemic when there were fewer applications lodged. From 2014–15 to 2021–22, the average number of applications lodged was 3844.

2.47 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that Child visa cases are generally complex and may take longer than a year to finalise. As complexity affects each year’s caseload, these factors should be factored into planning. The department should set out for the government the existing visa caseload and its forecast of future demand and capacity to meet this, considering likely resourcing and the complexity of on hand applications. Planning which does not fully take account of applications carried over from previous years is unlikely to result in the annual level of demand being met. In practice, the delivery of the program is planned in the same way as limited visa programs.

2.48 Before 2021–22, migration program outcomes for Partner program visas have either aligned with or under-delivered against annual planning levels, resulting in increases in the caseload and processing times (see Figure 2.4). Following the shift to an even split in available places between the Family and Skilled programs in 2020–21, the Partner visa caseload reduced from 96,361 in 2019–20 to 64,111 by the end of June 2021.

Figure 2.4: Partner (first stage) visa program planning levels and outcomes compared with lodgements and on hand between 2014–15 and 2021–22

Notes: Partner visas are two-stage visas which include a provisional (first stage) visa and a permanent (second stage) visa. To avoid double counting, only first stage Partner visa grants count toward the migration program. The data in this figure captures first stage Partner visa grants only. Only visas granted contribute to the program year outcome. The outcome does not include refused or withdrawn applications.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by Home Affairs.

2.49 In February 2022, the government agreed to a proposal by the department to manage the Partner visa program on an on-going, demand-driven basis. Home Affairs advised that this would assist in mitigating growth in the application pipeline and processing times.

2.50 Demand-driven programs are required to be managed within the funding provided through the annual Budget process. Funding allocated to the department for visa processing may be subsequently adjusted in accordance with the government’s Variable Visa Funding Model (see paragraph 1.12). The number of applications lodged for demand-driven visa categories is unlikely to remain the same from year to year, with potentially large variances affecting the delivery of the Partner visa program. This could result in unanticipated increases in the level of funding required, if key planning assumptions are not made clear to the government and stakeholders.

Planning for capped programs — Parent

2.51 Section 85 of the Act permits the Minister to determine the maximum number of visas of a specified class or classes in a specified financial year. The capping provision is applied to the Contributory Parent visa, Non-Contributory Parent visa and Other Family visa classes. Home Affairs advised the ANAO that the planning ceilings set by the government reflect government policy.86

2.52 Table 2.2 shows the number of lodgements and grants made from 2016–17 to 2021–22, and the number of unfinalised applications for Parent visa applications remaining on hand each year.

Table 2.2: Parent visas — processing activity and program outcomes

|

Activity type |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

|

Planning level |

8675 |

8675 |

8675 |

7371 |

4500 |

4500 |

|

Outcome |

7563 |

7371 |

6805 |

4399 |

4500 |

4500 |

|

Lodgements |

25,000 |

13,590 |

13,246 |

12,664 |

14,827 |

17,606 |

|

On hand |

97,065 |

99,965 |

102,854 |

108,659 |

114,359 |

125,233 |

|

Grant rate |

94 per cent |

94 per cent |

94 per cent |

81 per cent |

93 per cent |

94 per cent |

Notes: Parent visa figures are a sum of Contributory Parent and Non-Contributory Parent visa categories.

The cap for Parent visa applications increased to 8500 for 2022–23.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by Home Affairs.

2.53 The number of unfinalised Parent visa applications in the Parent caseload increased from 2016–17 to 2021–22. However, the number of visas granted between 2016–17 and 2019–20 was less than the cap set by the government. In 2020–21, the cap was reduced from an average of 8349 over the previous four years to 4500 for 2020–21, closer to the department’s actual rate of finalisation in the previous year.87 Table 2.3 shows the average level of achievement for Family program visa categories between 2016–17 and 2019–20.

Table 2.3: Average achievement against planning levels for Child, Partner, Parent and Other Family visa categories from 2016–17 to 2019–20

|

Visa category |

Average achievement between 2016–17 and 2019–20 |

|

Child |

91 per cent |

|

Partner |

90 per cent |

|

Parent |

78 per cent |

|

Other Family |

73 per cent |

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by Home Affairs.

Identifying and managing risks to delivery

2.54 Risk is the effect of uncertainty on objectives and can be defined as ‘the possibility of an event or activity preventing an organisation from achieving its outcomes or objectives’.88 Home Affairs’ Risk Management Framework requires it to identify three types of risk:

- strategic risks posed by external threats;

- enterprise risks which are internal risks that affect delivery against objectives; and

- operational risks resulting from the day-to-day activities of a business at the program and sub-program level.

Strategic context

2.55 Sources of strategic risk are considered in an internal document setting out a 10-year view of broad social, economic and environmental trends most likely to affect Home Affairs’ portfolio operations.89 It describes migration as a key component of economic recovery from the pandemic, and identifies Australia’s ageing population; global competition for labour; and the displacement of people as key sources of risk.90

2.56 The 10-year outlook is intended to inform policy and planning priorities and the identification of risks by individual business areas. Home Affairs’ Corporate Plan for 2022–23 identifies ‘Manag[ing] Migration and Travel’ as one of 10 priorities.91 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that its 10-year view and Corporate Plan provide a framework for considering risk at the enterprise, divisional and branch levels.

Risk management approach

2.57 Between 2019–20 and 2020–21, the department identified nine strategic risks, including a strategic risk associated with the migration program. Strategic Risk 9 was: ‘Visa and Migration – Australia’s economic prosperity, security and social cohesion are compromised by a poorly designed, implemented or managed migration and visa program’.

2.58 In 2021, Home Affairs altered its approach to managing risk. Its new framework aims to more closely link operational and enterprise-level risks. Enterprise risks relate to factors within the department’s control which may affect the implementation of government decisions and priorities. Accountability for strategic risks is considered to reside at a whole-of-government level. While internal guidance recognises that effectively managing shared risks requires agreement and the allocation of risk management responsibilities, Home Affairs has not clearly identified how it will manage shared risk relating to the delivery of the migration program with other government entities.

2.59 The department has identified six enterprise risks which relate to enabling functions for its programs and are considered to be within its control to manage. These risks are: people management; security and integrity; organisational compliance; business integration; health, safety and well-being; and business planning.92

2.60 Divisions are required to identify risks that may impact on their ability to achieve their business objectives.93 Immigration Programs Division (IPD) has identified two risks which relate to the enabling function of ‘security and integrity’. These are: ‘failure to prevent and detect and respond to caseload fraud and risk’; and ‘failure to prevent, detect and respond to fraud and corruption within the Department’. Mitigation of these risks is supported by relevant controls, for example: regular program monitoring; analysis and reporting on trends; collaboration with external stakeholders; and targeted investigations.

2.61 The department’s risk management framework requires risks to be identified and managed at the business level, with risk reporting integrated with business planning. The intent of this approach is to utilise specialist skills within business units to identify and manage risk on a day to day basis. The Family Visas Branch risk register for 2021–22 identified risk aligned with the division’s objectives for the delivery of the migration program. Risks related to: fraud and integrity in the management of the visa caseload; workforce effectiveness; and ensuring decisions are made in accordance with legal, policy, operational and administrative requirements.

Alignment of strategic and enterprise risks

2.62 Enterprise risks identified in division-level business plans do not directly relate to Home Affairs’ assessment of sources of social, economic and environmental risk which may impact on the delivery of the migration program. When reviewing and reporting on enterprise risks, divisions may not provide adequate visibility of impediments to achieving program objectives and assurance over how these are being mitigated.

2.63 In June 2022, the Executive of the Immigration Group identified that since the adoption of enterprise risks, business areas no longer reported in a structured way to enterprise-level committees on migration program risks, and there was a lack of coordinated reporting on the efficacy of risk controls. Home Affairs has not clearly articulated how its identification and management of migration program risks align with the potential sources of strategic and shared risk described in its strategic guidance.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.64 Business plans at divisional level should clearly link identified risks and controls to sources of social, economic and environmental risk which may affect the delivery of the annual migration program. |

3. Implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Home Affairs has appropriate arrangements for ensuring it is effective and efficient in its delivery of the Family Migration Program.

Conclusion (and/or findings)

While Home Affairs’ arrangements to enable the delivery of the Family Migration Program are appropriate, its implementation of these requires strengthening to ensure the consistent and timely provision of family visa services. The department lacks clear frameworks for measuring efficiency for the purposes of improving business outcomes and systematically managing aged applications.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made six recommendations aimed at strengthening the department’s: analysis of client feedback; arrangements for the prioritisation, risk-tiering and allocation of visa applications; monitoring and assessment of efficiency; remediation of potential delays in visa processing and the finalisation of aged cases. The ANAO also identified seven opportunities for improvement for the department to: strengthen its management of the visa caseload through the documentation of allocation decisions and oversight of mechanisms used at the local level to allocate applications; ensure the department has appropriate policies and processes for monitoring and reporting on potentially delayed applications; clarify processes for remediating areas of errors outside its set tolerance; and address timeliness in the processing of visa applications as part of its quality management processes.

3.1 Effective and efficient visa processing services reduce the time and resources required by the government to process applications and wait times for applicants. Appropriate services to assist clients to lodge a valid application, together with effective case allocation, support efficient visa processing. Effective processes for deciding on visa applications provide assurance that applications are appropriately assessed and clients are advised of outcomes in a timely manner.

Are there appropriate processes to manage lodgement?

Website information to assist applicants to lodge applications under the Family Migration Program is relevant and conveyed in plain language. Routine call centre and complaints reporting does not provide sufficient detail and analysis to support improvements to the delivery of the Family Migration Program. The department determines whether an application is invalid quickly, but communication with clients whose applications move to further stages of assessment is limited.

Access to information before and after lodgement

3.2 To obtain a visa, applicants must first lodge an application. The requirements for a valid application are set out under the Migration Act 1958 (the Act) and Migration Regulations 1994.94

3.3 Accessible public information can support applicants to lodge valid applications. Several documents establish the department’s approach to ensuring the accessibility of its public information, including information about the migration program.

- Home Affairs’ Media and Communication Strategy 2021 states that ‘information must be accessible to all, taking into account … diverse audiences’. Its Channel Strategy 2017–20 (channel strategy) states that the department aims for people to be able to ‘access information and services anywhere, at any time, and on a range of devices’.95

- The department’s Multicultural Access and Equity Policy Guide states Home Affairs aims to ‘take primary responsibility for identifying, understanding, and responding to the needs of their clients’.96

The government’s Digital Service Standard states that services should be accessible to all users regardless of their ability and environment.97

Digital channels

Home Affairs’ website

3.4 Home Affairs’ channel strategy is directed at encouraging people to ‘self-serve through the digital channel for the majority of information and services’. The department advised the ANAO that its website is the preferred method for communication as this is: available 24 hours a day; a lower cost channel; and enables resources to be directed to processing visas.

3.5 The government’s Style Manual sets out detailed standards entities should follow when publishing information for the public.98 Websites should:

- use short, simple sentences in the active voice;

- provide information relevant to answering key questions; and

- use familiar search terms and be easy to navigate.

3.6 In November 2021, the department identified that online content was not resolving client queries about Partner visas.99 In response, Home Affairs reviewed relevant webpages and made improvements to the content and structure of information and the design of navigation, with changes published on 9 August 2022.

3.7 ANAO testing of the department’s website in October 2022 found that information about different visa types and eligibility conditions could be readily located. There was broadly consistent use of plain language, with around 10 per cent of content determined to be ‘hard to read’.100 An interactive feature allowed the user to answer questions that help with identifying options relevant to their circumstances. Information about costs could be accessed via a price estimator or by following links to pricing information for specific visas. Under ‘Help and support’, information was provided about ‘Who can help you with your application?’.

3.8 ANAO testing indicated that while the website could be readily accessed using a mobile device, this reduced the functionality of some navigation menus.101 Information about visas was not available in languages other than English. In advice to the government in 2020, the department noted that the number of migrants who self-identified as not speaking English well had increased. There were also more people migrating from countries whose native language was not closely related to English (e.g.: Mandarin or Arabic).

3.9 To ensure public information is also available to people from non-English speaking backgrounds, the Style Manual recommends user-research.102 Feedback sought by Home Affairs on its website has informed a project to deliver online translation services. It intends to develop an On-Demand Web Translation tool to allow clients to visit web pages and select to view content in their own language (user testing is scheduled to occur by June 2023).103 This would extend the department’s capacity to make essential information about Australian visas and visa application processes available to its diverse audiences.

3.10 Since 2021, Home Affairs’ website includes advice to prospective clients to provide complete and accurate information at the time of application.104 This is aimed at reducing the need to issue requests for additional information and the time needed to determine validity. The department has not evaluated whether this approach is achieving its objectives.

ImmiAccount

3.11 Applications for Partner and Sponsored Parent (Temporary) visas are required to be lodged using an online account called ImmiAccount.105 The account guides the applicant in providing mandatory information and allows them to see if their application has been received and is undergoing assessment by the department.106

3.12 Applicants who lodge an electronic application through ImmiAccount receive an automated letter acknowledging that their application has been received (this does not state that the application is valid). Applications with potential validity issues are referred for manual processing by a central team. Home Affairs advised that it aims to determine the validity of applications within a week of lodgement. If an application is deemed invalid at this time and does not require follow-up, the processing officer issues an invalid notification letter (see paragraphs 3.44–3.47).

3.13 Some family visa clients may wait more than a year for a final decision on their application. During the first 12 months, most applicants do not receive further updates about the status of their application unless there is: a requirement to provide further documentation; the application has been assessed as invalid; or the visa is granted or refused.107 The department advised the ANAO that its ability to provide updates to clients digitally is limited by its systems, and that ‘the nature of visa processing makes it difficult to breakdown information that would be meaningful and helpful’.

3.14 Applicants do not receive advice that their application is still being progressed in meaningful timeframes. An ‘Application in Progress’ (‘reassurance email’) is automatically generated if a year has passed since the application was lodged or at least six months since the last reassurance email was issued. The letter advises the applicant to log on to their ImmiAccount to check on the status of their application or access website information about global processing times.

Call centre services

3.15 Web information may not be sufficient in helping clients to understand all requirements for lodging a valid visa application.108 Home Affairs’ offices are generally not open to the public.109 Clients are advised to contact its Global Service Centre (GSC) if they cannot find information on the website or their issue is complex. The GSC responds to enquiries from clients in Australia and overseas during standard business hours in the client’s local time zone.110

3.16 GSC call operators have access to call handling guidelines and information (termed ‘knowledge articles’) to help them be consistent in responding to common enquiries. The ANAO reviewed 50 knowledge articles relevant to responding to the top five categories of enquiry to the call centre relating to Family Migration Program (Family program). Where information can be located on the Home Affairs’ website, the operator is encouraged to direct the client to this. Operators may escalate issues within the call centre or with a visa team for response. A client who indicates they cannot access the internet is advised of alternative options, for example, to ‘visit a friend’s house or their local library/internet café’.

3.17 Home Affairs’ call centre produces reports which capture the percentage of enquiries for individual visa categories. Standard reporting does not capture:

- the stage of a client’s application at the time of enquiry or specific client issue;

- the location of the caller (beyond ‘Australia’ and ‘overseas’); and

- the extent of consistency or quality of call centre responses.111

Home Affairs advised the ANAO that requiring this information to be captured would be ‘impractical, costly, and would unduly lengthen call answering, handling and response times if applied broadly across all types of calls’.

3.18 The most frequent enquiry to the GSC is a client wanting to check the status of their visa application.112 A call centre operator is able to access information about whether: the application has been granted, refused or found invalid; correspondence has been sent; or the application is still being processed.

3.19 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that operators are unable to provide detailed information to clients about when their application is likely to move to the next step or when their visa may be granted because of the limitations of the department’s information systems. Operators are advised to inform clients that the department cannot provide status updates and direct them to ‘self-service’ via the website.

- The only circumstances where an operator may access the client’s file for further information about processing times is if the client has waited ‘more than double the standard processing time for 90% of applications’. The operator is to ‘[a]void over-servicing or repeating information, and to close the call’.

- If an application is still being processed, the client is advised that no timeframe can be provided. The client can submit an enquiry to a processing office.113

Web-based time estimation tool

3.20 Clients may also be directed to a visual tool on the department’s website for estimating how long their application could take to finalise (also referred to as the ‘Global Visa Processing Time Guide’ or ‘Guide’). When a client enters the date on which they lodged their application, the Guide indicates whether it falls within or outside the ‘standard processing timeframe’ for their type of visa. The department’s analysis of user feedback in August and September 2022 indicates that there was benefit in providing information in a visual way for non-English speakers. Figure 3.1 provides an example of a visa application that is outside the current processing timeframe, as at 28 October 2022.114

Figure 3.1: Home Affairs website visa processing time estimation tool

Note: The source information for the estimator is updated when new data is available.

Source: Department of Home Affairs, Visa processing times guide [Internet], Home Affairs, Canberra, available from https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/getting-a-visa/visa-processing-times/global-visa-processing-times [accessed 28 October 2022].

3.21 The Guide does not provide information on processing times for around half of the Family program visa types.115 The department does not publish information for visa types:

- affected by long processing times;

- for which reported times are not available due to low monthly finalisation rates; and

- for which reported times vary the most from month to month.

These are mostly the capped visa categories which have limits on the number of applications which can be finalised within a program year, such as the Parent visa category. For the visa types included in the Guide, the website provides a link to further detail about the time (shown in days or months) currently required to process a percentage of visas. For clients who fall outside the time in which 90 per cent of applications are processed, there is no ability to check on their visa or seek further information via the website.

3.22 Home Affairs conducted beta testing of the website tool from 26 August to 25 September 2022. During this time, it was used over 343,000 times across all visa types. Feedback from users indicated 28 per cent found the tool useful. Around 36 per cent of comments were from visa applicants who were primarily interested in obtaining specific information about the processing time for their application.116 The department reported a reduction in the overall volume of calls it received on processing times of approximately five per cent.

Global processing times

3.23 In addition to the time estimation tool, Home Affairs’ website provides information on a linked webpage which indicates how much time a percentage of visas takes to be finalised, based on recently finalised cases.117 For most of the visa types listed, the website details the number of months required to process a percentage of visas (25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles).118

3.24 The difference in time taken to process 25 per cent of visa applications compared with 90 per cent of visa applications varies according to the type of visa. For example, in February 2023:

- 25 per cent of offshore Partner program visas (first stage, subclass 309) were finalised within four months, with 90 per cent finalised within 30 months; and

- 25 per cent of onshore Partner program visas (first stage, subclass 820) were finalised within six months, and 90 per cent were finalised within 37 months.

3.25 Appendix 5 shows the number of days taken to finalise 75 per cent of applications for Partner, Parent, Child and Other Family visa categories for 2018–19 to 2021–22.

3.26 While aimed at managing client expectations, the processing times indicated on Home Affairs’ website may not provide a clear picture of the likely wait time, as there can be significant variances from month to month. The ANAO identified that for the first stage Partner visa program in 2021–22, there was a 118-day difference between April 2022 and May 2022, a change in processing time of 18 per cent.119 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that variances indicating increased processing time may reflect the finalisation of older applications.

3.27 In October 2022, Home Affairs provided information about its management of long processing timeframes for the Parent program visa on a separate webpage for that category, including actions taken to resolve discrepancies between onshore and offshore processing times.

3.28 The United Kingdom Visas and Immigration Service introduced service standards in 2014 for the expected time to complete different application types to improve its focus on service outcomes.120 The service provides information on its website about its performance against standards for particular visa categories. Clients are advised if their application will not be finalised within the standard.

3.29 Home Affairs previously published time goals for the processing of visas, but abolished these in March 2017 citing client support for reporting global processing times. It reported that this was because ‘it has increased transparency and provided clients with current processing times rather than aspirational service standards’.121

Reporting and analysis of client feedback

3.30 Home Affairs does not monitor caller enquiries at the Family migration sub-program level to identify call trends such as: the country of origin of calls; wait times for offshore Family program visa clients; or repeat calls by applicants.