Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Interpreting Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection in delivering high quality interpreting services to its clients.

Summary

Introduction

1. One quarter of Australia’s resident population was born overseas. In the 2011 census, 19 per cent of the total population spoke a language other than English at home. Of this 19 per cent (4.085 million), 17 per cent (694 450) stated they could not speak English well or at all.1 Interpreting services provide nonEnglish speakers in Australia with the ability to access essential services, such as government services, medical assistance and legal advice. Some people, such as those in immigration detention2, including community detention, also have substantial requirements for interpreting services.

2. Australia’s interpreting industry is maturing, with a growing number of private sector and government providers. It is a varied industry, with a common brokerage model, whereby service providers match clients with interpreters in the required language. In Australia, there are between three and five thousand active interpreters covering more than 170 languages and dialects. The industry has a predominantly casual workforce, characterised by lower salaries and less generous conditions of service than many other occupations.

3. Interpreting services are provided in a wide range of environments. These include: the detention network and refugee processing; medical consultations with general practitioners and in hospitals and mental health facilities; courts and police stations; and emergency situations. For these reasons, interpreting services are provided on a twenty-four hour/seven days a week basis.

Translating and Interpreting Service

4. As new migrants settled in Australia following the second world war, the need for language services was recognised. The Commonwealth Government assumed responsibility for translating functions in 1958 and in 1973 established a free telephone interpreting service. In 1991, these services were combined into the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS). This service was established within the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP), to provide telephone and on-site interpreting services and to manage a small translation program. TIS National3, as it is now known, provides a brokerage service, matching clients with interpreters (service providers) on a twenty-four hour, seven days a week basis.

5. TIS National is one of the largest public sector interpreting service providers. It has almost 3000 registered interpreters, covering approximately 170 languages and dialects providing telephone and on-site interpreting services to three client categories: internally to DIBP, to eligible clients for whom interpreting services are free of charge, and to fee paying clients. Its major client is DIBP, for which it provides interpreting services to communicate with detainees, both onshore and offshore and to facilitate access to DIBP’s other services. TIS National also provides free interpreting services to eligible clients accessing eligible services4 through the Settlement Services Program, managed by the Department of Social Services (DSS). In addition, TIS National provides services to non-DIBP clients (on a fee-paying basis), including other government entities.

Administrative arrangements

6. TIS National is a cost centre within the Visa and Offshore Services Division of the department. It provides services within the department but also acts as a commercial service provider within the interpreting industry. Its financial arrangements, including its costing and billing framework, are guided by the Financial Strategy and Services Division (FSSD) of the department.5

7. In 2013–14, TIS National generated just over $153 million in revenue, two-thirds ($100 million) of which was notional, for providing internal services within DIBP.6 Around one quarter of TIS National’s revenue ($37 million) was paid by external fee paying clients, with the balance ($15 million) coming from the provision of fee free services through the Settlement Services Program. Growth in demand for TIS National interpreting services has, on average, been around 20 per cent per annum, increasing from over 1.1 million telephone interpreting services being provided in 2011–12 to 1.5 million in 2013–14. The number of onsite interpreting services increased from just over 66 000 to more than 81 000 in the same period.

Multicultural access and equity

8. The objectives of the Government’s multicultural access and equity policy include equal access to government and other services. The adequate provision of interpreting services is an essential element of the success of that policy. Successive reviews of multicultural access and equity;©f-. programs have found that the lack of English competence was the principal obstacle for migrants when trying to access services and information. An efficient interpreting industry is an essential component of providing equality of access to services for non-English speakers.

9. The Australian Government recognises that quality language services are an important part of the Government’s commitment to access and equity. A joint DSS and DIBP review, which commenced in September 2014, will provide advice on government investment in the translating and interpreting industry and how DSS’s and DIBP’s requirements for interpreting services should be delivered. An assessment of TIS National’s contribution to the provision of interpreting services will be considered by the review, which is expected to report in April 2015.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

10. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection in delivering high quality interpreting services to its clients.

11. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- the department has effective business and program management arrangements;

- the interpreting workforce is managed effectively;

- high quality interpreting services are delivered; and

- the delivery of interpreting services facilitates compliance with the multicultural access and equity framework.

Overall conclusion

12. There are almost 700 000 people in Australia whose first language is not English and who do not speak English well or at all.7 To access essential services these people rely on the availability of interpreting services, either delivered via the telephone or, less often, in person. In this context, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) has a specific ongoing need for interpreting services for new and existing migrants and those people in immigration detention. TIS National, an internal business unit within DIBP, primarily provides interpreting services to the department, but also to other clients. One of these clients is the Department of Social Services (DSS), which funds fee free services for eligible users under the Settlement Services Program. As such, the interpreting services delivered through TIS National are a major contributor to the fulfilment of the Government’s access and equity policy objectives.

13. TIS National has effective arrangements in place for providing a range of interpreting services to DIBP and to external clients. It is also a significant participant in Australia’s interpreting industry, with almost 3000 registered interpreters. An internal review of TIS National services in 2010 prompted an update of managerial requirements, as well as the implementation of projects to upgrade technology to increase TIS National’s competitiveness and to improve interactions with its client base. Further, TIS National is active in implementing policies to increase the learning and development opportunities available to its interpreters and the professionalism of the interpreting industry.8 However, while the provision of interpreting services is managed effectively, the TIS National business unit would benefit from stronger administrative arrangements in several key areas. These areas include clarifying the strategic direction for TIS National and the policy basis for the charging of fees for interpreting services, and better preparing and supporting interpreters when deployed to DIBP’s immigration detention facilities.

14. In line with multicultural access and equity awareness, the demand for TIS National services has grown substantially over the decades. The daytoday management response to this increase in demand has been effective, but ongoing operations have lacked a strategic focus, particularly in respect of TIS National’s role as a government owned service provider in a maturing interpreting industry. Clarifying TIS National’s strategic policy objectives would enable both the department and TIS National to develop appropriate business solutions to underpin its interpreting service delivery model, currently a combination of services delivered internally to DIBP and externally to other government and commercial entities and private individuals. This clarification of objectives is likely to be informed by the joint DSS/DIBP review of TIS National, which is currently underway.

15. TIS National provides interpreting services to its clients, including DIBP, and charges fees for these services. DIBP has characterised TIS National’s services as a cost recovery activity for many years. Under the government’s cost recovery policy, entities are able to recover the efficient costs of their cost recoverable activities and retain these amounts. However, DIBP’s analysis shows that TIS National has been recovering amounts in excess of its costs. In practice, DIBP is charged at cost for TIS National services, and external clients are charged on a commercial basis. Once TIS National’s role is settled, DIBP will need to consider the most appropriate financial arrangements to be applied to TIS National services.

16. DIBP is the biggest user of TIS National interpreting services and the operational area which consumes the most interpreting resources is the department’s detention network. The deployment of interpreters to the network is a complex exercise, with responsibility being shared by DIBP’s Detention Operations Branch and TIS National. Currently, interpreters deployed to the network are not given access to the same pre-deployment resilience assessment, training and post deployment debriefs, as other DIBP workers. There is also a lack of clarity in relation to the respective management responsibilities of DIBP and TIS National for interpreters on deployment. Providing appropriate support to interpreters, and clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the staff in the immigration detention network charged with managing interpreters while on deployment, would better support the interpreters and assist in managing their wellbeing during these engagements.

17. Notwithstanding the outcome of the previously mentioned joint DSS/DIBP review, DIBP will need to determine the financial arrangements that should apply in relation to the delivery of TIS National’s interpreting services. In this context, the ANAO has made two recommendations directed towards determining the most appropriate financial arrangements for TIS National’s services and for preparing and supporting interpreters prior to, during and post their deployment to the detention network.

Key findings by chapter

TIS National’s Administrative Arrangements (Chapter 2)

18. TIS National is managed by a Director and has three staffing cohorts: almost 3000 registered interpreters, employed on a casual basis; approximately 66 full-time equivalent (FTE) permanent administrative staff (31 per cent); and 126 FTE non-ongoing contract staff (69 per cent) in its call centre. Senior management oversight is provided by the Visa and Offshore Services Division, complemented by policy and operational guidance from the TIS National Business Strategy Steering Committee (TBSSC).9

19. Following an internal departmental review in 2010, TIS National’s management has been proactive in driving innovations in communications technology to provide more efficient and client focussed interactions and making the organisation more responsive to commercial pressures.

Strategic direction

20. As previously discussed, TIS National provides services internally to the department, and externally to other fee paying clients and on a fee free basis as part of DSS’s Settlement Services Program. Demand for TIS National’s services has grown by, on average, 20 per cent per annum over recent years. TIS National has responded reactively to this growth in demand for services generally, as well as increases in demand for interpreters in DIBP’s detention facilities. However, the department has not developed strategic policy priorities for the interpreting service. The current review of government investment in the translating and interpreting industry, being conducted jointly by DIBP and DSS, provides an opportunity to determine TIS National’s strategic direction.

Administrative arrangements

21. TIS National’s business planning and administrative arrangements provide an effective framework for delivering its interpreting services. The call centre operations are well managed and business and program reporting is comprehensive, with monthly and annual reports being provided to the Director and senior executives. Business initiatives, such as moves towards the implementation of self-service technology, to better manage client and interpreter communications are being progressed. Upgraded telephony is being implemented and video interpreting options are also being explored. Appropriate risk management strategies and operational procedures have also been developed in response to a fire at the Melbourne premises in 2012.

Financial management

22. Currently, DIBP characterises TIS National’s interpreting services as a cost recoverable activity. The government’s cost recovery policy enables the efficient cost of such an activity to be recovered and retained by the entity. Such cost recovery arrangements are normally applied to regulatory activities in a non-competitive environment and are covered by the government’s cost recovery guidelines. However, TIS National’s interpreting activities provided to non-DIBP clients, are delivered in a commercial environment and, consequently, its fees are set on a commercial basis.

23. TIS National has imposed fees for its interpreting services for many years. In 2011, the department undertook a review to determine the underlying costs of TIS National’s activities. That review demonstrated that there was significant over recovery of costs for all but one of TIS National’s services, contrary to the government’s cost recovery guidelines.10 In response to this audit, DIBP again assessed the extent to which its fees aligned with expenses. The department’s analysis of data from 2014 shows that there continues to be a significant over recovery of costs.

Interpreting services and multicultural access and equity

24. Successive reviews of multicultural access and equity programs have identified a lack of competence in English as the principal obstacle for migrants wishing to access information. As part of the Settlement Services Program for new migrants, the Government offers free access to interpreting services in certain situations. Further, the availability of fee free interpreting services is another mechanism to address this problem.

25. At present, DSS administers the fee free interpreting services program, delivered through TIS National. TIS National also provides services to clients other than DSS, such as government departments, non-government organisations and utilities companies, providing interpreting services on a fee for service basis, which enables these entities to meet their access and equity obligations.

Interpreter Workforce Management (Chapter 3)

26. TIS National faces a number of challenges in managing its interpreter workforce, including the escalating demand for interpreter services; changing demands for priority languages; a highly casualised industry in which interpreters are self-employed; and relatively few education opportunities for professional advancement and recognition.

27. TIS National’s registered interpreters have expertise in 170 languages and dialects. It recruits interpreters through ongoing website invitations to register as an interpreter and contracts with them via a deed of standing offer. It also has a contractual arrangement with a second interpreting agency to cover any shortfall in available interpreters.

28. TIS National supports moves to increase the professionalism of the industry through: its interpreter allocation policy, which gives priority in the allocation of interpreting jobs to the best qualified interpreters in the language; the introduction of accreditation based pay, to encourage interpreters to raise their level of qualifications; the encouragement of professional development through reimbursement of professional registration fees and scholarships and sponsorships. These initiatives are designed to improve the quality of the services provided.

29. TIS National’s mystery shopper program, was introduced in 2012 for quality assurance and performance management purposes. The mystery shopper program entails a contracted agency making up to 140 calls per month across seven major language groups. The monthly reports analysing the results provide TIS National with ongoing assessments of the quality of its telephone interpreting services. The program also enables TIS National to assess the performance of its interpreters individually and to detect any trends in performance issues across the workforce that may require attention.

Deploying Interpreters to Detention Facilities (Chapter 4)

30. Interpreters are essential to the effective management of DIBP’s detention network. TIS National provides interpreters to the department as a priority activity, both for onshore processing and for other work in the detention network and the community. This work takes up 82 per cent of TIS National’s resources and provides over two-thirds of its revenue.

31. The deployment of interpreters to the detention network is a shared responsibility between DIBP and TIS National. DIBP determines the number of interpreters to be deployed to the network and the languages required and TIS National supplies the interpreters. Interpreter numbers are generally determined by requests originating from interpreter coordinators, the key DIBP person responsible for managing interpreters in the detention network.

Management of interpreters in the detention network

32. While a degree of local flexibility is important, the management of the interpreting function and interpreters across the detention network would benefit from clarification of the lines of responsibility for two key elements of this management responsibility. The first element is the efficient use of interpreters in the facility for the duration of their deployment; and the second is the management of interpreters in terms of their wellbeing while on deployment, for example for such matters as accommodation, transport and communications requirements. While TIS National has a role in the management of interpreters generally, the interpreter coordinators, who are part of DIBP’s detention operations function, formally manage the interpreting function and individual interpreters while they are on deployment. The interpreter coordinator role includes conducting interpreter meetings and providing feedback to interpreters on certain performance issues, both individually and collectively. In practice, some interpreter coordinators do not always organise these meetings, record the proceedings or address the concerns raised by interpreters. Further, DIBP acknowledges that some interpreter coordinators do not have sufficient management experience and training prior to undertaking this task.

Work health and safety in the detention network

33. The management of interpreters on deployment is a challenge for DIBP and TIS National. These challenges are compounded by the remoteness and offshore location of some of the facilities and by the nature of the work in which interpreters are engaged. The department and TIS National recognise these difficulties and have been working together to improve the working conditions for interpreters.

34. Interpreters, like many other workers within the detention network, have a difficult job to do. The mental health interviews and those where detainees are being interviewed to progress their application for refugee status can be stressful. The combination of the physical environment and the nature of the work being undertaken while in the detention network means that particular attention must be given to providing a safe work environment and preparing interpreters for deployment. Currently interpreters are not given a pre-deployment resilience assessment, nor are they offered the opportunity to have a post deployment debrief.

Summary of entity responses

35. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and to the Department of Social Services. The entities’ summary responses to the proposed report are provided below, while the full responses are provided at Appendices 1 and 2.

Summary of DIBP response

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) welcomes the findings outlined in the report of the audit on the Management of Interpreting Services by the Department’s language services provider, TIS National. In particular, DIBP welcomes the conclusion that TIS National has effective arrangements in place for providing a range of interpreting services to DIBP and to external clients.

DIBP agrees with the two recommendations as presented in the proposed audit report. The DSS/DIBP review of TIS National, which is currently underway, will clarify the policy basis for setting the fees charged for interpreting services. TIS National will engage an independent supplier to undertake a detailed analysis of its cost base and will participate in a voluntary tender submission process available as part of a Competitive Neutrality Review. The Department will also implement improved support arrangements before, during and after deployment to facilities in the detention network.

Summary of DSS response

DSS agrees that a clarification of the strategic objectives of TIS National will inform future improvements to effective service delivery and that this will be considered as part of the TIS National review.

DSS also notes the report’s acknowledgement of the role that TIS National plays in relation to the Government’s Multicultural Access and Equity Policy, an area for which DSS is responsible. DSS agrees that the extent to which TIS National monitors its contribution to the achievement of access and equity objectives may also usefully be considered as part of the review process, taking into account a clarified strategic rationale for TIS National.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.50 |

To provide a sound basis for TIS National’s charging of fees for interpreting services, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

DIBP’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.64 |

To improve the support arrangements provided to interpreters before, during and after deployment to facilities in the detention network, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection provides contracted interpreters with appropriate resilience preparation and debriefing services. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter outlines the policy and administrative context for the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s arrangements to deliver interpreting services and the audit objective and approach.

Introduction

1.1 Interpreting services provide the means by which the Australian Government and other individuals and organisations can communicate with newly arrived migrants and residents, and others who are not fluent in English.

1.2 Australia’s resident population of 21.5 million people includes approximately 5.3 million people who were born overseas. Eight of the top 10 countries of birth11 for this overseas born population are countries where the first language is not English. The results of the 2011 census show that 19 per cent of the population (4 million people) spoke a language other than English at home and 17 per cent of this cohort (694 450 people) could not speak English well or at all.12 Interpreting services, therefore, have traditionally been offered as part of the Australian Government’s settlement services program to assist new arrivals and those without a basic capability in English to participate as soon and as fully as possible in Australian society by minimising the effect of language barriers.

The interpreting industry

1.3 The interpreting industry in Australia comprises interpreters, interpreting service providers that link interpreters to clients, and the professional associations that manage aspects of the industry or act for it in various fora.

Interpreters

1.4 Interpreting is the oral rendering of the spoken word from one language to another. The interpreter must render the translation within the following parameters:

- facilitate clear communication between two parties from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds;

- communicate everything said without distortion or omission; and

- be professionally detached and impartial throughout an interpreting assignment.

1.5 Interpreters work in a wide range of environments, including the immigration detention network, hospitals and mental health facilities, courts, police stations, legal offices and with government service providers. Some of the specific challenges faced by interpreters include:

- inexperience on the part of clients working with interpreters;

- the nature of the job itself which can be mentally and emotionally demanding; and

- in some cases, deployment to the detention network, where interpreters may experience a difficult physical environment and lengthy periods of separation from friends, family and traditional support systems.

1.6 Interpreting is also characterised by lower salaries and less generous conditions of service when compared with many other occupations.13 The industry has a predominantly casual workforce, where interpreters are generally paid by the hour (or part thereof) and employment is often uncertain. Recognition of higher qualifications is limited and interpreters, as contractors, bear many of the costs of their employment, including professional development, travel costs and tools of trade, such as mobile phones and computers.

Service providers

1.7 Interpreting service providers include Australian and state government agencies, and private providers. One of the largest Australian Government providers is the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National). Centrelink (part of the Department of Human Services) also has a large in-house interpreting service. State government providers include the Victorian Interpreting and Translation Service, the New South Wales Community Relations Commission, Queensland Health Interpreting Service and the South Australian Interpreting and Translating Centre. The major private providers include On Call and Ethnic Language Services.

Professional bodies

1.8 The Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators Incorporated (AUSIT) is the national professional association for interpreters. AUSIT produces and updates periodically a Code of Ethics, which sets the standards for the ethical conduct of interpreters in Australia and New Zealand. The association holds events and training workshops and generally aims to provide a forum to foster professional development and promote quality standards for interpreters.

1.9 The National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) is the national standards and accreditation body for interpreters in Australia. It was established in 1977 to develop standards for the expanding interpreting industry. NAATI is owned and jointly funded by the Australian, state and territory governments. It tests and accredits interpreters and certifies tertiary level courses in interpreting. Together, AUSIT and NAATI set, maintain and monitor standards in the translation and interpreting profession in Australia. AUSIT recognises NAATI accreditation as the minimum basic qualification for practising as a professional interpreter in Australia. NAATI endorses and promotes the AUSIT Code of Ethics for interpreters and translators.

1.10 Professionals Australia has been approved as the union to represent interpreters.14 Professionals Australia advocates for policy changes at state, territory and Australian Government levels to drive procurement improvements in order to promote better conditions for interpreters.

TIS National

1.11 The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) manages TIS National.15 TIS National provides a brokerage service, matching clients with interpreters via a telephone contact centre and an online booking service. The services provided include a twenty-four hour, seven days a week telephone interpreting service and on-site interpreting services. Free interpreting services are provided to non-English speaking Australian citizens and permanent residents communicating with approved community organisations and individual service providers. Fee free services are provided to eligible individuals accessing eligible services, through the Australian Government’s settlement services program. TIS National charges fees to clients who request interpreting services and who are not eligible for fee free services.

1.12 The majority of TIS National’s services are delivered within DIBP’s detention network, both onshore and offshore. Non-DIBP services are provided on either a fee free (depending on meeting certain eligibility rules) or fee for service basis.

1.13 Demand for TIS National services has grown at an estimated 20 per cent per annum since December 2011, with the growth in demand expected to increase to 25 per cent in future years. Table 1.1 shows the growth in demand over the last four calendar years.

Table 1.1: Demand for TIS National services from 2011–14 (by calendar year)

|

Services delivered |

2011 |

20121 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

Telephone |

1 022 774 |

980 129 |

1 357 544 |

1 335 890 |

|

On-site |

66 097 |

68 110 |

80 756 |

82 224 |

|

Total |

1 088 871 |

1 048 239 |

1 438 300 |

1 418 114 |

Source: TIS National data.

Note 1: A major fire in TIS National’s call centre occurred in August 2012 disrupting services for several months.

1.14 DIBP is the single largest user of TIS National services, consuming around 25 per cent of total services (known as ‘jobs’). These jobs involve around 85 per cent of TIS National’s interpreting effort, when measured by time taken.16 The high proportion of services devoted to DIBP interpreting reflects the time consuming and expensive nature of on-site interpreting services at some of the more remote immigration detention facilities, where DIBP requires interpreters to be available on a seven day a week extended hours basis. Table 1.2 summarises TIS National’s DIBP, non-DIBP and fee free service activities, and its reported revenue for 2013–14.

Table 1.2: TIS interpreting activity and revenue 2013–14

|

Activity and revenue |

DIBP |

Non-DIBP |

Settlement services (fee free services) |

|

Number of jobs |

386 402 |

879 259 |

234 852 |

|

Minutes consumed |

119 315 444 (85 per cent) |

14 631 893 (10 per cent) |

7 305 095 (5 per cent) |

|

Revenue1 |

$100 734 631 |

$37 048 253 |

$15 793 222 |

Source: ANAO analysis of TIS National advice to ANAO, 29 September 2014.

Note 1: The revenue figures quoted are the figures generated prior to an internal discount of 34 per cent being applied to both DIBP and DSS fee free services. In 2014–15, the discount applied to the fee free services will reduce to 15 per cent. Interpreting services provided to internal DIBP clients are notionally charged for at the same rate as those for external clients. Internal accounting arrangements mean that no actual money is transferred within the department.

1.15 TIS National’s non-DIBP and fee free client profile is shown in Table 1.3. The top 10 fee paying non-DIBP clients are shown in the next chapter at Table 2.3.

Table 1.3: TIS National non-DIBP client profile

|

Agency |

Number of client codes4 |

Agency |

Number of client codes |

|

Fee paying services |

Fee free service |

||

|

Australian Government agency1 |

5464 |

Local government |

321 |

|

Contracted client2 |

33 |

Medical practitioner3 |

23 506 |

|

Non-government organisation |

2245 |

Non-government organisation |

761 |

|

Private sector |

4218 |

Parliamentarian |

167 |

|

State/territory government agency |

4022 |

Other private sector |

332 |

|

Overseas client |

16 |

Trade union |

40 |

|

Total |

15 998 |

Total |

25 127 |

Source: ANAO analysis of TIS National data.

Note 1: TIS National deals with its Australian Government clients at a cost centre level, which accounts for the large number.

Note 2: Contracted clients are clients who have an existing contractual relationship with DIBP as a service provider (such as Serco) and under the terms of their contract are required to use and pay for TIS National services.

Note 3: Medical practitioners comprise the largest single category using fee free services through the Doctors’ Priority Line.

Note 4: Anyone wishing to use TIS National services is assigned a client code in the TIS National job entry system.

Reviews of interpreting services

1.16 The delivery of interpreting services has been the subject of periodic policy and administrative reviews. The Parliament and government agencies have had an ongoing interest in the provision of interpreting and translation services to non-English speaking Australians, particularly in the context of Australia’s access and equity policies. Key reviews include the:

- 1992 evaluation of the 1985 implementation of the Australian Government’s Access and Equity Strategy;

- 1996 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs report on migrant access and equity, ‘A fair go for all: report on migrant access and equity’;

- triennial reports produced by the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship from 2006 until 2012, on access and equity in government services;

- 2009 report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman on the use of interpreters in Australian Government agencies; and

- 2011 ministerial review of the access and equity policy.

1.17 There have also been several internal reviews of TIS National, the most significant of which were:

- a 1997 internal review, which primarily focussed on options for enhanced service delivery and the need to streamline the administration of this national service;

- a 1997 review of the usage and accessibility of interpreters and translators;

- a 1998 review by the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs of the use of qualified interpreters and translators by Commonwealth agencies for the purpose of developing a policy proposal on the use of interpreters by Commonwealth agencies;

- DIBP internal audits of:

- TIS processes and controls (March 2001); and

- TIS operations (November 2006);

- a review of settlement services in 2003; and

- a review of TIS National conducted in 2010 by Ernst and Young on behalf of DIBP and subsequent internal review by the department’s Financial Strategy and Services Division.

1.18 The external and internal reviews of TIS National have consistently identified ongoing challenges for the organisation, which include the:

- difficulties in recruiting interpreters for ‘new and emerging’ languages due to fluctuations in the migrant and humanitarian intakes and the consequential range of language groups to be covered;

- high costs of providing quality services; and

- keeping pace with improved technology through ongoing investment.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection in delivering high quality interpreting services to its clients.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- the department has effective business and program management arrangements;

- the interpreting workforce is managed effectively;

- high quality interpreting services are delivered; and

- the delivery of interpreting services facilitates compliance with the multicultural access and equity framework.

1.21 The focus of the audit was on the delivery of interpreting services by DIBP. The audit methodology included:

- fieldwork in TIS National, DIBP and the DSS, including interviews with relevant staff from each of these agencies;

- examination of documentation relating to the delivery of interpreting services and the operations of TIS National;

- consultation with available interpreters as well as a survey of all TIS National registered interpreters. The survey was designed to gain insights into the performance of TIS National as an employer and service provider, and to identify any potential barriers to improved interpreter performance; and

- consultation with key stakeholders, including AUSIT, NAATI and clients.

1.22 Audit fieldwork was undertaken in DIBP and DSS offices in Canberra and TIS National’s premises in Melbourne. The audit team also visited three locations where interpreters provide on-site services within the detention network.17

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $504 000.

Structure of the Report

1.24 The structure of the Report is:

|

Chapter |

Chapter overview |

|

Chapter 2: TIS National’s Administrative Arrangements |

This chapter examines TIS National’s administrative arrangements, including its financial framework as well as its contribution to the multicultural access and equity policy framework. |

|

Chapter 3: Management of the Interpreter Workforce to Deliver High quality Services |

This chapter examines TIS National’s management of its interpreter workforce and strategies to deliver high quality services. |

|

Chapter 4: Deploying Interpreters to Detention Facilities |

This chapter examines the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s management of the deployment of interpreters to the immigration detention facility network. network. The department’s work health and safety obligations to interpreters working in this environment are also discussed. |

2. TIS National’s Administrative Arrangements

This chapter examines TIS National’s administrative arrangements, including its financial management framework, strategic direction and its contribution to the multicultural access and equity policy framework.

Introduction

2.1 TIS National was established in 1973 in Sydney and Melbourne as an emergency telephone interpreting service. It has grown over the last 40 years into a major service provider in the interpreting industry, largely in response to emerging DIBP operational needs, and increased general demand for interpreting services that facilitate access to services and information by nonEnglish speakers. Growth in demand for services has led to a corresponding increase in TIS National’s revenue base.

2.2 TIS National is a stand alone interpreting business operating within DIBP. It provides telephone and on-site interpreting services to DIBP and other government agencies, and to the general public. DIBP is its major client, with fee free interpreting services provided to eligible clients and fee for service interpreting services to anyone who wishes to pay for them.

2.3 The ANAO examined the arrangements DIBP has in place to effectively manage TIS National. In particular, its financial management framework, the role and strategic direction of the business unit and its contribution to the government’s multicultural access and equity policy framework were reviewed.

TIS National’s management arrangements

2.4 TIS National is part of the Visa and Offshore Services Division of DIBP and is overseen by the Global Manager Client Services.18 It is situated in Melbourne in DIBP’s Victorian Regional Office with administrative support functions provided by DIBP. TIS National is managed by a Director, with responsibility for the business unit and three staffing cohorts: almost 3000 registered interpreters, employed on a casual basis19; approximately 66 fulltime equivalent (FTE) (31 per cent) permanent administrative staff; and 126 FTE (69 per cent)

non–ongoing staff.

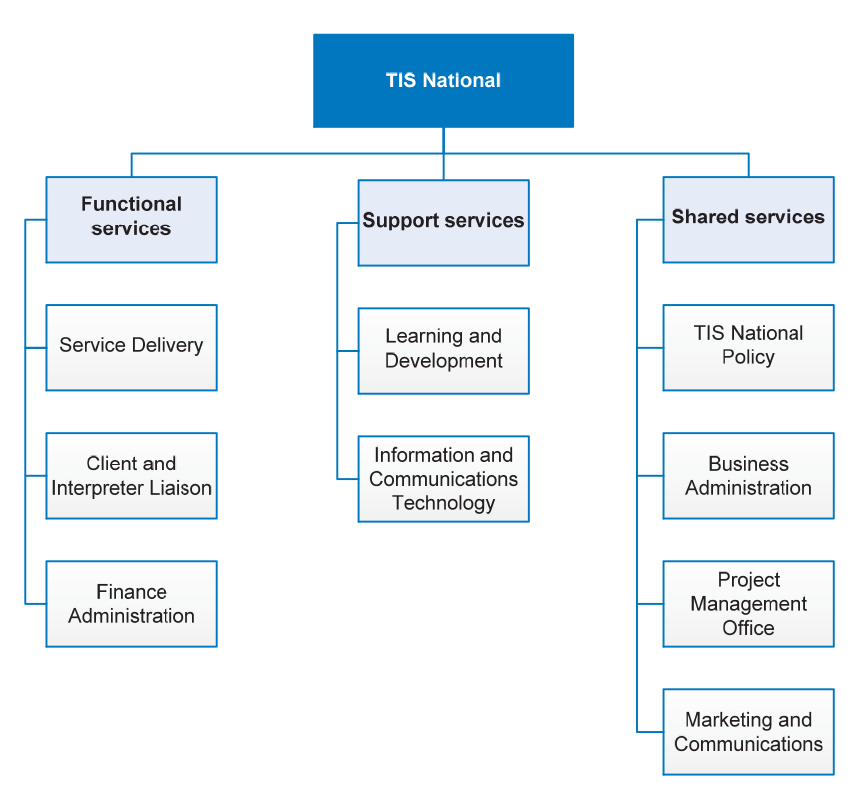

2.5 The major business units in TIS National are set out in Figure 2.1 and comprise:

- functional services including:

- a 24/7/365 contact centre, of seven teams, including a shift team, that works outside standard business hours, and the on-site and pre-booked interpreter booking teams;

- client and interpreter liaison, including an irregular maritime arrival (IMA) team, that liaises with DIBP’s strategic planning and logistical support team for the provision of interpreters throughout the detention network; and

- financial administration, including invoicing, monitoring of debt and financial reporting;

- support services—learning and development and ICT technology; and

- shared services, which include TIS policy, business administration, contracts, business analysis and reporting, quality assurance, project management, and marketing and communications.

Figure 2.1: TIS National Functional Structure

Source: TIS National Functional Structure, 2014.

2.6 A key program management issue for TIS National is maintaining appropriate staffing capability, particularly in its contact centre. If staffing in the contact centre is not maintained, the number of calls answered declines, with fewer interpreting services requests being raised and filled, resulting in a reduction in turnover.

2.7 Most staff in the TIS National contact centre are employed on a nonongoing basis for a maximum of 12 months, after which time they must have a break of three months before re-applying for a position. The Australian Public Service recruitment constraints in early 2014 impacted on TIS National’s ability to meet its service levels in the contact centre because of delays in the department gaining permission to fill the non-ongoing positions.

2.8 High turnover is a feature of the contact centre’s operations, requiring flexible staffing approaches and close management attention. In order to reduce the impact of high staff turnover on service delivery, early in 2014, TIS National management gained approval for the team leader20 positions in the contact centre to be employed on an ongoing basis. This administrative reform should mean that corporate knowledge is retained at the team leader level, enhancing the likelihood of service standards being met.

Managing key TIS National business development initiatives

2.9 The 2010 internal review of TIS National concluded that its business model required improvement if it was to operate in a commercialised business setting. In particular, the review identified that TIS National needed to improve its service quality and invest in ICT infrastructure. Such improvements would include building on its asset base and purchasing enabling technologies.

2.10 DIBP and TIS National were responsive to the report, moving quickly to establish a steering group and develop a plan to implement the recommendations of the review. Over the last two years, $10 million has been invested in technology projects. TIS National advised that it is likely that current projects will require up to an additional $16 million over two years, given demand projections. Recent and current TIS National projects and initiatives include:

- enhanced access to TIS National services;

- e-billing; and

- video interpreting.

Enhanced access to TIS National services

2.11 The primary methods by which external clients access TIS National services is online through its dedicated website or via the telephone contact centre. A dedicated TIS National website (separate from DIBP’s website) was launched on 1 July 2013, with progressive improvements to date. Originally the new site re-formatted existing content, targeting access across three major user groups—non-English speakers; interpreters and agency or business clients. Phase two, delivered in August 2013 introduced online forms, eligibility and price calculators. Phase three, TIS Online, is a self-service portal which is expected to deliver automated online booking requests by clients and some degree of management by interpreters in relation to their own bookings. A limited pilot commenced in December 2014, with the portal expected to be available to all TIS National clients and interpreters in early 2015.

2.12 In June 2014, TIS National implemented a new telephony software platform for its contact centre that integrates self-service applications and agent-assisted transactions. As well as ultimately delivering increased automation as part of the move to self-service applications, the system is intended to provide enhanced reporting and real time statistics for call handling in the contact centre. The introduction of this platform also provides TIS National with the capability to handle current volumes of calls within service level standards21 as well as the capacity for further expansion. Additional future functionality is expected to deliver increased self-service capability, and natural language and voice biometric capability.22 The upgraded telephony platform has assisted the contact centre to meet its grade of service (target standards) obligations in July 2014 for the first time in two years, following setbacks caused by a fire in 2012 (discussed below).

E-billing

2.13 TIS National introduced electronic invoicing (e-billing) in November 2013. Currently, 73 per cent of statements, representing 96 per cent of the dollar value of invoices, is issued by email. TIS National advised that the introduction of e-billing has generated cost savings of approximately $3000 per month (45 per cent). It also considers that e-billing has delivered supplementary efficiencies such as improved cash flow, better customer selfservice, (clients can access their e-bills online without the involvement of TIS National finance staff) and freed up staff for other duties.

Video interpreting

2.14 A video interpreting pilot was conducted by TIS National from 2012 in a number of detention locations around Australia. While the trial demonstrated the usefulness of this interpreting option, particularly in nonsensitive detention settings, there are still some obstacles to be overcome. The major advantage of video interpreting was the ability for staff in remote locations to access immediately a wide range of interpreters, with consequential cost and staff savings. The ANAO’s discussions with interpreters and users of the service in detention facilities indicated that the pilot had support in the detention network, although hardware and connectivity issues were at times problematic. The hardware was difficult to use and internet connectivity in the centres at the time was not reliable enough to support the service on a fully operational basis.

2.15 The initial trial demonstrated that future success of a video-based channel for interpreting was dependent on:

- the right equipment being supplied and installed at the remote location;

- users being comfortable with the technology and able to use it with minimal input;

- high quality, high speed and reliable connectivity; and

- the service to be supplied being appropriate for the needs of the client base.

2.16 TIS National recognises that there is both an internal DIBP and external need for robust, secure and timely video interpreting services, for example in the support of such services as telehealth and remote medical diagnosis. In 2013, TIS National secured approval for a joint project team to commence an upgraded pilot for a further 12 month period. This pilot is expected to assist TIS National to deliver a service channel to support increased demand for onsite interpreting in regional and remote locations. The latest advice from TIS National indicates that it is in the early stages of taking the pilot into the trial phase early in 2015, prior to rolling the service out to the broader network.

Risk management and business continuity

2.17 TIS National participates in DIBP’s corporate planning and risk management processes and also produces its own risk management documentation and business plan. The divisional business plan identifies two high level risks that have particular relevance to TIS National operations: noncompliance with service standards and the failure of the department to provide a safe and healthy working environment. The subsidiary TIS National business plan also identifies more detailed risks specific to its business, principally:

- a failure to provide sufficient interpreter capacity to support irregular migration demand;

- a failure to resolve accommodation issues for its contact centre, which limits its ability to satisfy work health safety (WHS) requirements, expand channel offerings and meet the growing demand from irregular maritime arrivals (IMAs) and other clients; and

- a failure to undertake succession planning.

2.18 TIS National’s ability to manage service performance, interpreter supply, and work health and safety issues are discussed in Chapters 3 and 4. As discussed below, accommodation constraints are being addressed by the sourcing of additional contact centre accommodation and re-locating the backup site from outside the city centre to a nearby city site. Additional contact centre accommodation has also facilitated increased channel offerings.

2.19 While TIS National has identified a failure to undertake succession planning as a business risk, it has not identified whether this applies only to staff, or to systems as well, nor has it identified which systems and positions are most critical. For example, the Job Entry System Supporting IVR23 and CTI24 Applications (JESSICA)25, was initially installed in 2002, and provides the interface between TIS National and DIBP’s financial management information systems, as well as recording translating jobs by client and interpreter, the language and time taken for the job. DIBP’s Financial Strategy and Services Division (FSSD) has identified JESSICA as a critical system and, despite being many years past its anticipated ‘life’, it remains TIS National’s principal business application. There are no contingencies in place for this system or plans for ongoing maintenance of capability.26

Business continuity plan

2.20 TIS National has a business continuity plan in place. This plan, which takes into account the experience of a fire incident in 2012 (discussed below), documents the contingency arrangements27 in place to provide for continuous availability of interpreting functions, such as the continued provision of roundtheclock telephone interpreting services, with the highest priority to be given to TIS National’s emergency services’ ‘Priority 1300’ lines, and on-site interpreting services. TIS National advised that the business continuity plan, last updated in January 2014, is being re-considered in light of the impending decommissioning of a legacy system.

2012 fire incident

2.21 TIS National’s business continuity arrangements were tested by a major fire in August 2012. The fire destroyed telephony equipment, which resulted in major technical difficulties and disruptions to all TIS National phone, IMAs, local on-site and pre-booked services. Office accommodation and equipment were out of service for several months, with only five per cent capacity in the first week after the fire, increasing to 30 per cent by week four. The national priority lines and emergency phone interpreting services were able to continue as per the disaster recovery plan. While a complete recovery of services to full capacity was expected by late October 2012, service level standards did not return to pre-fire levels until approximately July 2014, when the upgraded telephony platform was installed.

Lessons learned from the 2012 fire

2.22 TIS National advised that the fire incident in 2012 has enabled a more informed approach to business continuity planning, with lessons learned including the:

- inadequacy of its backup site for an extended period of time, with service levels not returning to a reasonable level until after three months;

- need for redundant ICT technologies in addition to alternative locations to ensure continuity of service; and

- necessity for a comprehensive communications strategy to govern information dissemination in the event of a disaster.

2.23 As indicated above, TIS National has now expanded its call centre across two floors, with each floor being connected to a separate network core switch, thereby reducing the risk of both call centres being inoperative at the same time. The recently introduced cloud based telephony platform further reduces dependence on the DIBP infrastructure and network. TIS National is also currently exploring a new and larger backup site, given the limitations of the current site. In addition, it is able to publish alert messages quickly and independently on its stand-alone website homepage.28

2.24 One of the major lessons learned from the incident was the absence of a formal communications strategy within TIS National at the time of the fire. A communications specialist had been appointed shortly before the fire disaster and coordinated communications in response to the incident. TIS National analysed its response to the 2012 disaster, detailing the time of communication, the type of communication and the recipients of the communication at progressive intervals during the disaster and subsequent recovery operation. This information has provided the basis for managing communications for similar future incidents that have the potential to disrupt services.

2.25 One concern raised by an external service provider was the lack of notification by TIS National to other service providers about the fire. The severe disruption to services meant that other providers had to fill the service gap. Some warning or notice from TIS National about the extent of the damage and the likely recovery period would have better prepared key stakeholders for the surge in demand. TIS National advised that it is in the process of introducing an ecommunications platform to send targeted emails and SMS communications in the event of any further incident which significantly impacts on the delivery of services. TIS National could consider providing advice through these mechanisms to alternative service providers as well as to its own clients, service users and interpreters.

Management reporting and feedback

2.26 TIS National’s performance is reported publicly in DIBP’s annual report, where the annual growth in services, number of services performed, by channel and by accredited interpreters and languages in most demand are reported. TIS National’s budget is included in DIBP’s portfolio budget statements, separated by type of service, that is telephone and on-site interpreting.

2.27 DIBP and TIS National maintain management oversight of TIS National operations through:

- management reports extracted from information stored in the JESSICA database; and

- monitoring of formal and informal feedback.

Management reporting

2.28 As discussed in Chapter 3, there are presently no externally reported key performance indicators for TIS National’s services. TIS National produces internal monthly performance reports which provide advice to management29 on service standards, numbers of calls, numbers of requests and services provided for both on-site and telephone interpreting and a profile of IMA services. These reports provide a comprehensive overview of TIS National’s workload and performance against service level standards. The main categories reported include:

- information about clients—their usage of the service, the profile of usage (telephone or on-site), and dollar value to TIS National;

- information about interpreters—language skills, their work profile, and the number of jobs they do;

- information about jobs—the time each job takes, which interpreter was used, the client, type of job, and dollar value to the organisation;

- performance measures—language demand, service targets, and bookings information; and

- settlement services (fee free services) jobs.

Analysis of client feedback

2.29 Feedback provides information which can be used to improve programme and service delivery. TIS National updated and harmonised its feedback processes in April 2013 in line with DIBP’s Client Feedback Policy, which was introduced in September 2012.

2.30 TIS National has a number of channels available to clients and interpreters through which feedback can be provided, including an online feedback form, a dedicated phone line for external feedback, and a dedicated feedback mailbox. A very small number of feedback items are forwarded from DIBP’s Global Feedback Unit (GFU). An assigned staff member manages the receipt, acknowledgement and allocation of feedback items to line areas for resolution, providing timely attention to the matter and tracking of outstanding issues.

2.31 As part of the harmonisation process with DIBP procedures generally, TIS National began producing monthly feedback reports in October 2013. The monthly feedback reports provide information on:

- the origin of the feedback—agency, telephone operators, interpreters and non-English speakers;

- feedback by category—fees and charges, interpreter conduct, interpreter recruitment, language availability, TIS National policy, staff and services, website; and

- channels by which feedback is made.

2.32 Between November 2013 and July 2014, TIS National received a total of 905 feedback items, with 419 delivered through the online form (46 per cent), 315 via email (35 per cent), 160 items by telephone (18 per cent) and 11 items via the GFU (1 per cent). The majority of feedback (75 per cent on average) relates either to the performance of interpreters or complaints from interpreters, which is examined further in Chapter 3.

2.33 TIS National has implemented improvements to its services in response to the findings in the monthly feedback report. For example, as a result of feedback received during February 2014, the following measures were introduced:

- counselling of a number of interpreters in relation to behavioural issues, such as being logged in but not accepting calls, and rudeness;

- increasing the allocation of resources to the on-site team to improve service delivery in this area; and

- facilitating the submission of online feedback forms.

TIS National’s financial management

2.34 TIS National is an internal cost centre within DIBP. As such, while it is an independent service delivery unit of the department, it remains subject to financial policy guidelines set by FSSD.30 These policies include applying the Australian Government’s cost recovery and competitive neutrality principles to TIS National’s financial framework. DIBP initially implemented full cost recovery for TIS National interpreting services in 1991.

2.35 As previously noted, TIS National derives its revenue from the provision of:

- government appropriated fee free interpreting services;

- interpreting services to internal DIBP clients; and

- fee paying interpreting services to external clients.

2.36 Fee free telephone and on-site interpreting services are available to eligible persons who need to access key services. The free interpreting service was funded through DIBP’s settlement services program until November 2013, when the program was transferred to DSS. There is now a service level agreement between DIBP and DSS for the provision of fee free services through TIS National.

2.37 Internal DIBP clients and external fee paying clients are charged according to TIS National’s advertised schedule of fees. However, internal clients have a rebate applied to the invoiced amount so that the fees amount to the calculated service costs. An internal charge back arrangement by FSSD means that all monthly invoices are notional and result in a zero balance transfer (no actual money is transferred within the department). Table 2.1 sets out TIS National’s revenue for the three years 2011–12 to 2013–14.

Table 2.1: TIS National revenue for financial years 2011–12 to 2013–14

|

Revenue source |

2011–12 $(Million) |

2012–13 $(Million) |

2013–14 $(Million) |

|

Fee free settlement services1 |

11.7 |

12.3 |

15.8 |

|

DIBP IMA processing |

75.7 |

88.0 |

83.3 |

|

DIBP non-IMA |

8.4 |

12.5 |

17.4 |

|

Fee for service revenue |

31.3 |

28.5 |

37.0 |

|

Total revenue |

127.1 |

141.3 |

153.5 |

Source: TIS National and DIBP data.

Note 1: These figures include fee free language services. However, from the 2014–15 financial year the fee free settlement services revenue will be included in the fee for service revenue.

2.38 The ANAO examined:

- DIBP’s review of the TIS National financial framework; and

- TIS National revenue and the appropriateness of the application of cost recovery treatment to TIS National finances.

DIBP’s review of the TIS National’s financial framework

2.39 Following finalisation of the 2010 departmental review of TIS National, DIBP’s Executive Committee endorsed the TIS Review Implementation Plan, which included an internal review of TIS National finances, subsequently undertaken by FSSD. Major elements of the review included developing an understanding of the financial relationship between TIS National and DIBP, determining the true cost of the TIS National service and a consideration of competitive neutrality and cost recovery compliance. The TIS Review implementation plan further specified that FSSD needed to: provide detailed explanations of charge backs to TIS National; show how they were calculated (to enable TIS National to make sound business decisions); and develop a pricing methodology and policy. The review acknowledged that profit margins on TIS National services should be negligible.

2.40 The review resulted in a number of detailed reports relating to TIS National’s financial framework, which:

- explained TIS National’s operations;

- identified TIS National’s cost structure, developed a cost catalogue and costing and pricing methodology; and

- undertook revenue and budget analysis.

2.41 DIBP’s Executive Committee requested an update on progress to be brought to the Executive Committee within six months of its consideration of the 2010 review report. DIBP has not been able to advise whether this update occurred or if any further consideration of the TIS National financial framework has taken place at the most senior levels of the department after December 2010. Notwithstanding the requirements of the review, the FSSD reports have not been provided to TIS National.

The nature of TIS National’s charges

2.42 TIS National currently operates and is reported on as a ‘cost recovery’ activity. Cost recovery involves a government entity charging the nongovernment sector some or all of the efficient31 costs of a specific government activity, which may include the provision of goods, services or regulation for the benefit of the non-government sector. Under s.74 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and paragraph 27 of the Rule pursuant to that Act32, agencies are able to retain revenue collected for authorised activities under s.74.33 DIBP considers that it retains the revenue from TIS National’s fee paying services pursuant to this legislation.34 However, s.74 of the Act does not provide the authority to charge a fee. Such authority, which is most often legislative, but can be ministerial, is separately required.35 DIBP has been unable to locate authorisation for its current charging approach.36 Department of Finance advice indicates that in this situation a new authority should be sought from government.

2.43 The Department of Finance cost recovery guidelines set out the government’s cost recovery policy. The most recent set of guidelines, published in July 2014, tabulates key government charge types and their characteristics. The ANAO’s analysis at Table 2.2 shows that TIS National’s cost recovery activities do not align with the criteria provided in the guidelines.

Table 2.2: Characteristics of government charges—cost recovery fees and commercial fee for service

|

Type of charge |

General description and characteristics |

TIS National services |

|

Cost recovery fees |

Charging activities are directed by the government |

TIS National charges are not directed by the Government. There is no uptodate ministerial authority for the charges nor is there a relevant Cabinet decision. |

|

Charging is in relation to an ongoing activity undertaken on behalf of the Commonwealth |

Interpreting services provided to DIBP are undertaken on behalf of the Commonwealth, but interpreting services on a fee paying basis are not. |

|

|

Charges have a legislative basis |

There is no legislative basis for TIS National or for its charging regime. |

|

|

Involve charging an individual or non-government organisation |

Individuals and non-government organisations are subject to charges but so too are government organisations, including DIBP. |

|

|

Revenue is aligned with expenses incurred in providing the activity to the individual or non-government organisation |

Revenue is not aligned with expenses. |

|

|

Commercial charges (fee for service) |

Charging that occurs for a product or service in a commercial environment where potential or actual competitors exist |

TIS National provides fee paying interpreting services to individuals and organisations in a commercial and competitive environment. |

|

Generally not compulsory |

It is not compulsory to use TIS National interpreting services. |

|

|

Involves charges imposed by government business enterprises or other commercial charging arrangements and may be subject to competitive neutrality principles |

TIS National sets its charges in compliance with competitive neutrality principles. |

|

|

May relate to ad hoc, discretionary activities of an entity, including offsetting the costs of an activity |

TIS National’s fee paying interpreting services accessed by individuals and organisations are discretionary. |

|

|

Revenue from the activity need not equal expenses (it may be more than, less than or equal to expenses) |

Revenue from the activity is greater than the expense of providing the activity. |

Source: Department of Finance, Australian Government Cost Recovery Guidelines, Resource Management Guide No. 304 and ANAO analysis.

2.44 As shown above, TIS National’s interpreting service charges do not exhibit the following cost recovery characteristics as set out in the Department of Finance guidelines:

- charges do not reflect the efficient unit costs of the service;

- DIBP has not been able to provide to the ANAO any up-to-date authority to charge;

- TIS National services are not part of a regulatory arrangement where charges are applied to all users of the service; and

- users of the service are not compelled to use TIS National services—they have a choice in a commercial market.

2.45 Because TIS National charges for its interpreting services in a commercial environment, it must comply with competitive neutrality principles. Competitive neutrality means that TIS National cannot take a competitive advantage over its private sector competitors by virtue of its public sector ownership and should set its charges to negate any potential competitive advantage. This can mean that individual fees can be set to generate an acceptable commercial rate of return and may exceed the cost of service delivery, thereby generating a profit or an over recovery outside the guideline tolerances of the cost recovery regime (over or under five per cent of the estimated efficient costs of the service).

2.46 DIBP does not routinely assess the extent of the alignment of fees charged to external clients with TIS National’s costs. However, the FSSD review of TIS National’s finances in 2011 included analysis of TIS National’s inputs and cost drivers. The analysis shows that, in 2011, with one exception, costs were over-recovered by large percentages, up to 165 per cent in the case of one service type. In response to this audit, DIBP again assessed the extent to which its fees aligned with expenses. The department’s data shows that in 2014 there continued to be a significant over recovery of costs up to 97 per cent in the case of one service type.37

2.47 The cost recovery guidelines state that government entities should report on cost recovery, both at an aggregate level in their financial statements in accordance with the financial reporting rules, and at the cost recovered activity level on the entity’s website, as part of the cost recovery implementation statement (CRIS). DIBP reports on cost recovery activity at an aggregate agency level through its financial statements. However, the department does not report on its website at cost recovered activity level and has not prepared a CRIS in relation to TIS National activity since 2007.38

2.48 In the absence of a legislative authority to retain over-recovered costs, such monies are returned to the OPA as general government revenue.39 In 2011, a draft DIBP Executive Committee paper noted that an amount of $6.1 million had been earmarked for return to the OPA. There is no evidence that the paper was considered by DIBP’s Executive Committee, but the department has confirmed that no funds have been returned to the OPA over the last three financial years. TIS National and FSSD advised that, at present, any revenue received over expenditure is set aside each month and reviewed ‘intermittently to determine if we can re-invest into TIS or hand back to Finance’. However, the department was unable to quantify the accumulated over-recoveries since 2011, nor could it quantify the over-recovered funds that had been reinvested or the purposes for which such reinvestment had been made. In response to the audit, DIBP advised that:

… our financial statement team and the TIS Business Steering Committee are reviewing this at the moment, in preparation for next year’s financial statement audit.

2.49 DIBP should review the basis on which it charges fees to its internal and external clients for TIS National’s interpreting services, as well as take the necessary administrative steps to comply with the relevant government guidelines so that its administrative practices are open and transparent and that stakeholders are aware of the basis on which fees are charged.

Recommendation No.1

2.50 To provide a sound basis for TIS National’s charging of fees for interpreting services, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

- reviews the policy basis for setting the fees to internal and external clients; and

- takes steps to comply with the applicable requirements and government guidelines.

DIBP’s response:

2.51 Agreed. The Department will progress on this recommendation by:

1. The first element of the recommendation being addressed as part of the DIBP/DSS review of TIS National which is currently underway; the policy basis on which charges and fee structures are applied will be clarified, agreed and formally documented, consistent with government policy.

2. The second element of the recommendation will be addressed through two tactical activities:

a. TIS national will invest in engaging an independent supplier to undertake a detailed cost/service analysis providing a current cost base on which the elements under the Cost Recovery Guidelines can be applied, following this;

b. TIS National will participate in the voluntary tender submission process available as part of a Competitive Neutrality Review this financial year, noting possible MOG timeframes.

TIS National’s strategic direction

2.52 The strategic challenge for TIS National operations relates to the scope of its service provision. On the one hand, TIS National provides a highly tailored service underpinning many of DIBP’s functions. On the other, it provides a range of services to the general community and other government agencies, either for access and equity reasons, or on a fee for service basis. In this context it is appropriate that DIBP periodically reviews TIS National’s role and objectives. Such reviews may, where appropriate, include consultations with government about preferred service delivery and ownership arrangements.

DIBP internal review of TIS National

2.53 In 2010, a departmental review concluded that there was a need for government to determine the future policy direction for TIS National, given the increasing sophistication and competitiveness of the interpreting industry. Following the review, in 2011 the department established the TIS National Business Strategy Steering Committee (TBSSC), chaired at Deputy Secretary level. The Committee’s terms of reference are:

… to provide strategic direction and prioritisation on TIS specific matters relating to business strategy and priorities, strategic investment, TIS financials, cost of service delivery, language services policy, access and equity obligations and innovation pilots. The TBSSC will be the ultimate body to decide the strategic policy related direction of TIS National based on Departmental needs at the time.

2.54 The Committee initially met in 2011 and did not meet again until August 2013, with two further meetings since, in November 2013 and July 2014. While the TBSSC was intended to be a high level strategic policy body, the attention of the committee has been at a more operational level, focusing on such issues as financial and business arrangements, interpreter logistical arrangements, interpreter conditions and information technology and telephony projects.

2.55 At the August 2013 meeting, the TBSSC considered a paper identifying a residual gap relating to the general policy guiding TIS National operations. The TBSSC was advised that:

… there remains a gap relating (to) the general policy guiding TIS National’s operations and delivery of services. There are therefore a number of questions as to the nature of TIS National operations, whether it should operate independently as an “Office of Language Services”, if its operations are consistent and supportive of the broader access and equity aims of government and how TIS National’s interests can be best represented in discussion with the Minister’s office.

2.56 The minutes of the August 2013 meeting reflect concern that ‘no central policy ownership is in place for all TIS related issues’ and a decision was taken for the director of TIS National to ‘conduct consultations with relevant stakeholders over the next few months to prepare a paper for the next Steering Committee to recommend how this gap would be addressed’. However, prior to that meeting taking place machinery of government changes impacted on the department and TIS National. There was no further progress in clarifying the Government’s expectations of public sector interpreting services or how they might be delivered until December 2013, when responsibility for the fee free language services policy and program delivery was transferred to DSS.

2.57 In September 2014, the government tasked a joint DSS and DIBP Steering Committee with reviewing TIS National’s administrative arrangements. The review is to assess the ‘efficiency and cost effectiveness of the current arrangements, and whether the services provided by TIS National need to be undertaken within government, or could be more appropriately placed within the private sector or civil society’. The review is expected to be completed in mid-2015.

2.58 The resolution of TIS National’s strategic direction is overdue. Necessarily, in determining the future scope of TIS National’s services, consideration will need to be given to the costs, and benefits, of any changes to the current services. TIS National advised the ANAO that, for example, in relation to the interpreting services provided at DIBP’s detention facilities and for the processing of refugee claims, any move to a service provider external to DIBP will mean a significant cost imposition for the department, potentially in the tens of millions of dollars.

Interpreting services and multicultural access and equity