Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Disposal of Specialist Military Equipment

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Defence's management of the disposal of specialist military equipment.

Summary

Introduction

1. Defence manages Commonwealth assets worth some $75 billion1, over half of which comprise specialist military equipment (SME)—including ships, vehicles and aircraft. Each type of SME must be managed through its life cycle, the final stage of which is disposal. Disposal can include re-use within Defence for a different purpose, including for heritage or display, as well as transfer, sale, gifting or destruction.

2. SME disposed of in recent years includes the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN’s) frigates HMA Ships Canberra and Adelaide, which were scuttled as dive wrecks, but at unexpectedly high cost; the Australian Army’s fleet of Leopard tanks, most of which were retained or gifted for display; and the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF’s) F-111 long-range strike aircraft, a few of which were retained for display but most of which were destroyed because of asbestos content. Proceeds from SME disposals vary significantly across the years with changes in equipment sold—proceeds were $12.5 million in 2012–13 and $49.4 million in 2013–14. Defence disposal activity is expected to increase in the medium term due to Defence’s major program of upgrading and replacing SME over the next 15 years.2

3. Managing SME disposals requires an understanding of possible markets for the surplus equipment. It also requires Defence to consider international obligations, particularly relating to demilitarisation and technology of United States (US) origin; and Australian obligations relating to the management of hazardous substances, such as asbestos; environmental protection; and the resource management framework applying to government entities. Disposing of SME is therefore a complex task, whether achieved through re-use, retention for heritage or display, gifting, sale or destruction. Disposal risks include the potential for excessive and unanticipated costs, stakeholder dissatisfaction, and loss of reputation should the equipment pass into the wrong hands.

4. For the period considered by this audit, the primary legislation governing disposal of Commonwealth assets was the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act).3 Under the FMA framework, Defence’s internal instructions imposed an obligation on staff managing disposals to optimise the outcome for the Commonwealth in each case4, having regard to: (i) legal, contractual, government and international requirements; (ii) ensuring that actions would withstand scrutiny; (iii) being fair, open and honest; and (iv) considering the cultural, historical and environmental significance of providing the item to appropriate organisations.

5. Disposal of SME is part of the Defence capability life cycle. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) has overall responsibility for disposal of SME on behalf of Defence in conjunction with the Capability Manager, and the function is now co-ordinated by the Australian Military Sales Office (AMSO) in DMO’s Defence Industry Division.5 However, many parts of Defence may have an interest and involvement in any particular disposal.

Audit objective and scope

6. Following difficulties experienced with two major disposals in recent years, the Secretary of Defence and Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) wrote to the Auditor-General in April 2013 and asked that he consider undertaking a performance audit of Defence’s management of specialist military equipment disposals. In May 2013, the Auditor-General agreed to commence a performance audit as part of the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) 2013–14 work program.

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the disposal of specialist military equipment. The audit considered (i) whether Defence has conducted disposals in accordance with applicable Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements and Defence policies, guidelines and instructions; and (ii) where relevant rules have been departed from, the main reasons and consequences. The audit examined Defence records of selected disposals that occurred over the last 15 years, especially the period from 2005 to 2013, including actions in response to disposals not proceeding as intended.

8. The high-level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s performance were:

- Defence policies and procedures governing disposals comply with relevant Commonwealth legislation and policy;

- Defence disposal of SME is carried out effectively, in accordance with relevant legislation, policies and instructions; and

- recent reforms in the management of Defence disposals are suitably designed and progressing effectively.

Overall conclusion

9. Defence expends a great deal of time, effort and public resources on the procurement of new SME such as ships, aircraft and vehicles, and the introduction of such capability into service. The service life of individual items may vary but, ultimately, all of that SME must be disposed of. While the work of disposing of equipment is unlikely to be as interesting or attractive as acquisition and sustainment, disposal of SME is complex and often time-consuming, and can give rise to financial and reputational risks for Defence and the Australian Government. To be effective, and achieve the best overall outcome, SME disposals require a balanced assessment of risks and potential benefits with appropriate senior leadership attention within Defence.

10. Overall, Defence’s management of SME disposals has not been to the standard expected as insufficient attention was devoted to: achieving the best outcome for the Australian Government; reputational and other risks that arise in disposing of SME; managing hazardous substances; and adhering to Commonwealth legislation and policy for gifting public assets.

11. The major disposals examined as part of this audit have had a largely disappointing history. In the cases examined, disposals have generally taken a long time, incurred substantial and unanticipated costs, and incurred risks to Defence’s reputation:

- the disposal of RAN ships has proven expensive and, where they have been gifted for use as dive wrecks, costly to the RAN’s sustainment budget;

- the Army B Vehicles disposal was arranged through a request-for-tender, and the adequacy of the tender evaluation process has been questioned by internal and external advisers to Defence;

- the Boeing 707 aircraft disposal has been prolonged, involved, and yielded much less than the original contracted sale price; and

- the Caribou aircraft disposal remains ongoing after five years following a flawed tender process and uncertainty as to the identity and business of the major purchaser.

12. Problems relating to the Boeing 707 and Caribou aircraft disposals were already known to Defence and led the Secretary of Defence and Chief of the Defence Force to request that this audit be undertaken. The audit highlights a number of consistent underlying themes in the cases examined which go some way to explaining Defence’s recent difficulties in managing SME disposals. The key issues relate to: a disproportionate focus on revenue without full regard to costs; insufficient attention to risk management; the quality of internal guidance; fragmented responsibilities; and limited senior management engagement.

13. Defence’s disposal rules are not clear or fully developed for SME disposals, notwithstanding the proliferation of internal sources of guidance within Defence. In particular, Defence lacks a set of operational procedures to guide SME disposals and clearly identify roles and responsibilities across the large number of Defence stakeholders. As a consequence, Defence staff have limited guidance on key issues such as the potential costs of disposal activity, and there is no requirement to check on the identity or financial or other capacity of the entities with whom Defence is dealing. A number of the case studies examined in this audit indicate that shortcomings in Defence guidance relating to establishing the bona fides of third parties have contributed to increased risks to the Commonwealth’s reputation. Further, some of Defence’s internal rules—relating to gifting of assets—did not correctly reflect the long-standing requirements of the Australian Government’s resource management framework, introducing risks of inappropriate or incorrect gifting of surplus Defence SME.

14. While the reform of SME disposals has been attempted in recent years, it has not consistently held the attention of senior leadership within Defence. The round of reform that commenced in 2011, announced by the then Minister for Defence Materiel, was initiated with good intentions. However, it was not supported by sufficient analysis and was based on a flawed assessment of the prospect for making SME disposals into a net revenue-generating program. It was almost certainly over-optimistic in this objective, and underplayed the importance of adopting a balanced approach to managing risks. The initiative lacked ongoing senior leadership involvement and no arrangements were made to monitor and report on its progress. It appears now to have fallen away without tangible results.

15. A feature of recent major disposals has been a propensity for Defence staff to focus on the apparent revenue available from the sale of surplus equipment without full regard to the risks being taken in pursuit of that revenue. These risks, many of which have arisen in the case studies examined in this audit, include reputational risks and risks of further costs being incurred during the disposal process. As discussed, the then Minister’s announcement of disposals reform in 2011 highlighted the gaining of revenue as an objective for SME disposals. Once the reform program had been announced, there was a tendency at the operational level to focus on maximising the revenue from each disposal transaction with much less attention to the costs incurred, some of which arose in other parts of the Defence Organisation beyond the immediate purview of those responsible for the disposal transaction. As the audit shows, when delays are incurred and risks crystallise, the costs to Defence can exceed the potential revenue available. In the case of the Caribou aircraft disposal, a sale price of $540 000 was obtained from the principal purchaser while the DMO System Program Office responsible for the Caribou incurred an estimated $743 000 in disposal costs, including some $242 000 to pay contractors to identify and pack Caribou spare parts.

16. A major challenge for Defence in recent years has been the presence of asbestos in many of its items of military equipment. To meet clearly expressed ministerial expectations in 2008, Defence set about a vigorous remediation program to remove asbestos from its workplaces. Defence also resolved in late 2009, through a Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) directive, that items containing asbestos should be disposed of by sale or gift only where any asbestos contained within the item could not be accessed by future users, and as such would not pose a health risk to those future users. However, the audit has identified instances where the costs of identifying and removing asbestos from items being disposed of, and the prospect of greater disposal revenue, led Defence to dispose of items that may contain accessible asbestos without full regard to the management of the risks or transparent declaration of those risks to potential purchasers. An example is the ongoing disposal of Army B Vehicles, where Defence stated to its Minister that its strategy would involve removal of all accessible asbestos-containing items, including gaskets. This has not occurred and the risk of the continued presence of such asbestos-containing items has not been drawn to the attention of the purchasers of the vehicles.

17. The history of SME disposals indicates that Defence ministers often wish to be involved in making decisions on the gifting of military equipment, which can attract considerable community interest. However, the Defence Minister does not hold the formal decision-making authority for gifting Commonwealth assets. It is a long-standing feature of the Australian Government’s resource management framework that the Finance Minister has that authority and has delegated it to the Secretary of Defence. A challenge remains for Defence to develop an approach that provides early advice to ministers about the requirements and operation of the gifting delegation where any options for gifting are to be contemplated.

18. The key message from this audit of Defence SME disposals is that decision-making should be based on a broader understanding of the benefits, risks and costs of each disposal. To achieve an effective overall outcome, officials performing the disposals function need to have regard to the full picture, weighing up potential revenue against the cost of disposal action and the range of potential risks to Defence and the Australian Government—including the potential for reputational damage. The effective assessment and treatment of risks often requires experience and must be afforded higher priority within the Defence Organisation, including through senior leadership attention at key points in the disposal process for more sensitive items. Those who are assigned management responsibility for an SME disposal should be expected to develop the necessary breadth of understanding and be well placed to complete the disposal efficiently, effectively and properly.

19. The ANAO has made five recommendations aimed at strengthening Defence’s SME disposals framework and practice through: the review and consolidation of Defence’s internal guidance on disposals; the identification for each future major disposal of a project manager with the authority, access to funding through appropriate protocols and responsibility for completing that disposal; the collection of better cost information on each disposal; and reinforcement of Defence’s conflict of interest and post-separation employment policies.

Key findings by chapter

Disposals Framework (Chapter 2)

20. Disposal of Defence SME is governed by a framework of legislation, policy and procedure which, for the period under review, was established by the FMA Act. The FMA framework placed an obligation on each chief executive officer to manage agency affairs in a way that promoted proper use of Commonwealth resources.6 The Australian Government’s general disposals policy was stated indirectly in the gifting delegation provided by the Finance Minister to chief executives: that the property being disposed of should be sold at market price or transferred to another Commonwealth agency. While the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) provide a whole-of-government framework for procurement, they do not extend to disposal and there is not, and has not been, a counterpart to the CPRs for the disposal part of the asset life cycle. In the absence of an explicit Commonwealth policy, Defence developed internal procedures and processes for its disposal activities.

21. Within Defence there is a range of policy and guidance on disposals, some of which is inconsistent and requires review. Notwithstanding the proliferation of material, Defence’s policy and guidance is cast at too high a level of generality and lacks a practical procedural focus. For instance, Defence offers no direction in how to estimate and capture the full costs of a disposal project; and guidance does not include a requirement to verify the identity, financial viability or business purposes of a party to whom Defence may be considering selling its surplus SME. These practical issues arose more than once in the case studies examined in this audit, affecting the successful conduct of SME disposals.7 Another shortcoming in Defence’s current disposals framework is the absence of well-defined and robust disposal tender processes, resulting in one tender examined in this audit attracting criticism from both internal and external advisers.8 Sound guidance for the conduct of an SME disposal has been lacking for some years and, although DMO has been working on developing new policy and guidelines, these are not yet in place. Overall, Defence’s disposals framework remains immature, particularly given the nature of Defence materiel subject to disposal, and the associated risks.

Reform of Disposals (Chapter 3)

22. Defence initiated a first round of reform of SME disposals in 2011 with four priority areas: to reduce if not eliminate Defence major disposals cost9; to return funding to the sustainment of current capability; to generate and then maximise revenue from the sale of Defence’s military assets; and to appropriately recognise and preserve Defence heritage, particularly war heritage.

23. Defence based this reform on comparison with overseas experience. However, the reform proposal was not underpinned by sufficient analysis or research to support the expectation of generating revenue from SME disposals. Defence set about implementing the reform primarily through establishing long-term strategies for the disposal of SME in specific ‘domains’: two such strategies were those for RAN ships and for Army B Vehicles.10 The ships strategy has already run its course with only two ships disposed of—the ex-HMA Ships Manoora and Kanimbla—at a substantial cost to Defence. The B Vehicles strategy has returned funds, but there is no information on the costs incurred by Defence of managing the disposal.

24. Defence has not reported its performance in terms of the four 2011 reform priorities nor have measures or targets been set that would enable Defence to do so. The lack of financial data on major equipment disposals also hinders performance assessment against the priorities. The most significant insight from the initial round of reform is the need to take proper account of the relatively small scale of Defence equipment disposals, the additional costs which can arise due to Australia’s distance from overseas markets, and a limited local market for these assets based on historical sales experience.

25. In response to recent reviews and investigations of disposal processes, Defence has pursued a further round of reforms. Key initiatives underway include the revision of Defence’s disposals policy, the development of documented processes and templates to guide staff through disposal processes, and high-level planning for forthcoming disposals. However, there is currently no mechanism that allows Defence Disposals to track costs associated with a disposal project, and Defence should implement a monitoring and reporting mechanism that captures all significant costs. Substantial disposal costs can be incurred by disparate parts of the Defence Organisation, and while it may be challenging to keep track of them, monitoring can contribute to the effectiveness of Defence’s management of SME disposals by highlighting escalating areas of expenditure, such as berthing costs relating to ship disposals.11

26. The potential benefits of recent reforms are likely to be eroded if Defence does not more clearly identify project management responsibility and establish structured consultation arrangements for major equipment disposals. At present, a large number of separate Defence groups may be involved in, or have expertise relevant to, disposal processes, highlighting the need for clearly defined and well-coordinated disposal processes, and consistent internal guidance. Further, in more complex or sensitive cases, there is a need for sufficient senior leadership involvement in major equipment disposals and key decisions, to contribute to the effective and timely identification, assessment and management of risks.

Major Case Studies—Boeing 707 and Caribou Aircraft, and Army B Vehicles (Chapter 4)

27. The audit considered three case studies in detail, comprising the two disposals whose difficulties gave rise to the request for this audit, the Caribou and Boeing 707 (B707) aircraft fleets, and a more current disposal, B Vehicles.

The Caribou aircraft case

28. Defence sought to dispose of its last nine Caribou transport aircraft by sale, issuing a request-for-tender in October 2010. Two aircraft, earmarked for heritage purposes, were successfully sold to an historical aircraft society. However, the sale of the remaining seven aircraft proved troublesome. The preferred tenderer was replaced by another entity, and doubts arose over the latter’s credibility and financial viability. While Defence proceeded with the disposal and the purchase of the aircraft by the replacement entity, which paid for the seven aircraft, Defence retained the aircraft until doubts about the entity could be resolved. In January 2015, Defence informed the ANAO that the sale to this entity had been cancelled and Defence was considering alternative disposal options for the aircraft.

29. The Caribou disposal process demonstrated three key administrative shortcomings. Defence:

- did not observe that the original tenderer was being substituted by a separate entity and that the change was not merely a change of name;

- did not seek advice on the financial viability, background and integrity of the entity it was dealing with; and

- proceeded with the sale transaction (by issuing an invoice to the purchasing company) after becoming aware of concerns about the buyer. Not acting on available information exposed Defence and the Commonwealth to financial and reputational risk.

The B707 aircraft case

30. After first receiving an offer in mid-2007, Defence sold its B707 air-to-air refueller fleet to a private company based overseas, Omega Air, with an initial 2008 contract price of $9.2 million. Selling the B707 aircraft fleet proved troublesome to Defence. The disposal process demonstrated three key administrative and contractual shortcomings. Defence:

- did not conduct adequate checks on the financial viability of the purchasing company—an issue which also arose in the Caribou aircraft case;

- agreed that the payment of $3 million of the purchase price would be contingent upon US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification of the aircraft, when it was known to Defence that this was unlikely. In effect, this approach provided the company with a price reduction; and

- allowed the purchasing company to remove the aircraft from Commonwealth premises before full payment had been received. This arrangement was contrary to advice received from the Department of Finance and Deregulation and left the Commonwealth with reduced capacity to secure payment.

31. During much of the period over which the B707 transaction took place, Defence hired air-to-air refuelling services from the purchasing company, at a cost of over $24 million. The refuelling arrangement was cancelled in 2013 on the advice of the Secretary.

32. The company ultimately paid Defence $6.2 million for the B707 aircraft and related equipment. Defence did not receive the remaining $3 million of the original contract price because FAA certification was not achieved by 31 December 2014.

The B Vehicles case

33. B Vehicles comprise about 12 000 Army trucks, trailers and four and six-wheel drives, which are beyond their expected operating life. Defence has sought to dispose of the vehicles through an arrangement with an external company to detect and remediate asbestos in brake linings, and on-sell the vehicles to the public. This arrangement is expected to operate over some years as the vehicles are progressively withdrawn from service.

34. The B Vehicles disposal was arranged through a request-for-tender process which, following Defence’s tender evaluation, drew a complaint from a non-preferred tenderer. Defence obtained several sets of internal advice about the tender evaluation process, some of it highly critical (and some of it contradictory), and twice sought urgent external advice.

35. The external advice noted that there had been a number of fairly significant concerns raised about the evaluation process by internal review teams within Defence, raising doubt about the defensibility of the evaluation outcome and process. The reputational risks for Defence included exposure to criticism, loss of industry confidence and doubt about the integrity of the tender process. However, the final external advice also noted that Defence would have a basis to defend its decision provided it demonstrated that the assessments undertaken (including financial assessments) were sound, factually correct and supported by reliable analysis.

36. Defence persisted with its original tender decision without acting on the final external advice to demonstrate that its assessments were sound. The delegate’s decision to proceed with the preferred tenderer did not set out his reasons for not acting on the external advice. Given the sensitivities and potential risks involved in proceeding with the original tender decision, it would have been prudent to escalate the matter to more senior management, for additional counsel, oversight or decision.12 Defence records indicate that this course was not adopted.

Major case studies—common themes

37. Each of the major case studies considered in this audit took place in an environment of disposals reform focused on reducing costs and maximising revenue. This environment was due, at least in part, to Defence’s Strategic Reform Program (SRP)13 and later reinforced by the disposals reform program announced mid-2011. A consistent theme in the case studies has been pursuit of the disposal option that promised to yield the greatest revenue.

38. The disposal of SME is a complex undertaking, requiring a broad understanding of the benefits, risks and costs of each disposal, and their effective management. The focus on revenue has not always been matched with appropriate consideration of disposal costs nor of risks of a non-financial kind, such as risks to reputation. Further, Defence did not monitor the net financial position—that is, revenue minus all significant costs incurred by the Commonwealth for each disposal—to help assess the overall benefit of its disposal strategies. Probity and financial checks and identifying non-financial risks also received either limited attention or were given reduced weight in decision-making.

39. Disposing of SME through an RFT process requires Defence to strike a balance between optimising sale proceeds and minimising the Commonwealth’s overall costs and risks. To achieve an effective outcome, Defence must manage disposal activities, including any tender process, openly, fairly and equitably, and in a manner that will withstand scrutiny. Government and industry need to have confidence in the way Defence undertakes disposals, and the Defence Organisation needs to maintain fairness in its dealings with industry. Achieving these objectives necessarily requires a balanced assessment of risk and a broader, rather than narrower, view of Australian Government interests when planning and managing the disposal of SME.

Managing hazardous substances in disposals (Chapter 5)

40. Hazardous substances, in particular, asbestos, have been used widely in the manufacture of Defence SME. Over the last decade, Defence has put substantial effort and resources into remediating asbestos in its inventory and its SME.

41. A major decision in the management of asbestos in disposals was the VCDF’s clear directive to the Defence Organisation in October 2009: items that contain asbestos should be disposed of by sale or gift only where any asbestos contained within the item cannot be accessed by future users, and as such do not pose a health risk to those future users. A tension subsequently arose between the VCDF’s directive and the approach within Defence to maximise revenue from major equipment disposal.

42. In several cases examined by the ANAO—in particular, the Caribou aircraft and B Vehicles fleet—Defence has struggled in its efforts to manage the risks posed by asbestos in equipment intended for disposal. In the case of the Caribou aircraft, equipment disposal was a trigger to cease asbestos remediation. The sale of the majority of the Caribou was not completed and asbestos components remain in place, and it is now a matter for Defence to decide a future course of action. The two aircraft sold to an historical aircraft society retained any asbestos items previously contained in them.

43. Defence has not always provided appropriate information to potential purchasers or recipients about the asbestos content of SME subject to disposal, notwithstanding legal advice to do so, senior leadership expectations and undertakings to government. This is the case, for example, with the B Vehicles.

44. The B Vehicles may contain accessible asbestos in various locations such as brake linings and gaskets. The vehicles are on-sold to the public by a private company engaged by Defence and established for this purpose. After receiving the B Vehicles, the company only reports back to Defence on the results of its checking for asbestos in the vehicle brakes, and remediating these components where necessary.14 This disposal is ongoing.15

45. The F-111 aircraft disposal was largely managed by the DMO’s Disposal and Aerial Targets Office. Defence’s preference, given the use of asbestos throughout the aircraft, was to destroy most of them and retain only a few for Defence museums. Ministerial preferences led to a small number of aircraft also being retained for display outside Defence’s direct control in private museums, but with ongoing Defence involvement in monitoring and reporting on risks. Defence has based its management of this arrangement on a professional assessment of the risks, but the costs of ongoing monitoring and reporting by Defence are yet to be assessed.

46. Defence’s approach to some more recent disposals suggests that it has moved by increments from the VCDF’s original position of allowing no accessible asbestos to be gifted or sold. Defence informed the ANAO during the audit that the directive remains in place.

47. The potential long-term risks of SME containing asbestos have been highlighted by a request for Australian Government assistance from an external organisation. The organisation was gifted a major item of Defence SME by the Australian Government several decades ago. The item has asbestos-containing material that is widespread through its structure and the organisation has advised Defence that the asbestos is now posing a hazard. While the SME is no longer owned by the Commonwealth and the issue of Defence or Commonwealth assistance is yet to be determined, it raises the question of whether other legacy cases exist and what action may be needed to address any risks posed.

48. In December 2014, DMO advised the then Minister for Defence that it was ‘proposing to undertake a review of a number of past disposal activities to identify those items that contain hazardous substances, in particular asbestos containing material, that may give rise to potential future liabilities’. DMO did not indicate when that review was expected to be complete nor what action it proposes should the review identify further risks related to past disposal activities.

Gifting of Defence Specialist Military Equipment (Chapter 6)

49. Gifting of public property was prohibited under the FMA Act except in certain defined circumstances, including where the Finance Minister had given written approval to the gift being made. The Finance Minister had sole ministerial authority over gifting, and had delegated that power to chief executives under the FMA (Finance Minister to Chief Executives) Delegation, Part 17.16 This instrument required delegates to observe specific conditions when considering making such a decision. These long-standing arrangements have largely continued under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

50. The gifting rules have not been reflected accurately nor consistently in many instructions and guidelines for Defence staff. This may be due, in part, to the proliferation of such sets of instructions and guidelines. Defence should give prompt attention to the drafting of Defence instructions and guidelines to bring its documentation into alignment with the Australian Government’s resource management framework.

51. The audit identified instances when Defence did not approve gifting of SME in accordance with applicable Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements. For example, when DMO recommended to the then Minister for Defence in 2005 that he write to state premiers and territory chief ministers offering the ex-HMAS Canberra as a gift for use as a dive wreck, DMO did not advise the Minister that he did not have the authority to make such a gift under long-standing legal arrangements17, nor of the requirements set out in the gifting delegation. Similarly, the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF’s) Leopard tanks were offered by the Minister for Defence as a gift to Returned and Services League (RSL) branches in 2007, before a request was made to the Finance Minister seeking formal approval of the gifting.

52. Invariably, when items of SME are to be withdrawn from service, Defence will offer early advice to the Minister for Defence on proposed disposal arrangements. In that context, where any options for gifting are to be contemplated, Defence should advise the Minister that the Minister does not have authority to approve a gift, and of the specific requirements of the Finance Minister’s gifting delegation, including the requirement placed on the Finance Minister’s delegate to adhere to the Commonwealth’s general policy for the disposal of Commonwealth property, and to avoid establishing an undesirable precedent.

53. Further, experience has shown that gifting items of SME can involve substantial costs for Defence. For example, the disposal of the two RAN ships, ex-HMA Ships Canberra and Adelaide by gifting them to Victoria and New South Wales cost Defence at least $13 million.

Managing Other Risks (Chapter 7)

54. In addition to the matters considered above, a range of specific risks add to the complexity of managing SME disposals. The audit considered the following additional sources of risk:

- management of trailing obligations, specifically adherence to United States (US) International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which limit how Defence can dispose of US-sourced SME;

- perceived and actual conflicts of interest, which can arise for Defence personnel involved in disposals; and

- disposal of non-ADF SME, which has arisen in a small number of cases.

55. The US controls access to its defence technology through ITAR, making this a major consideration in many disposals because a large proportion of ADF SME is of US origin. Obtaining ITAR approval can take time and might not be granted. This can have cost or other consequences for a disposal. Defence has generally obtained ITAR approval where relevant for SME disposals over recent years. However, Defence has no centralised register of ITAR obligations in relation to existing SME, and could consider the cost-benefit of compiling a register to help manage its obligations.

56. A conflict of interest involves a conflict, which can be actual, potential or perceived, between a public official’s duties and responsibilities in serving the public interest, and the public official’s personal interests.18 The audit observed a number of instances involving individuals working for Defence subsequently taking up related positions with external organisations doing business with Defence. In some cases, the individual had remained a Reservist with continued access to Defence resources.

57. Defence’s post-separation employment policy requires ADF members and Defence Australian Public Service (APS) employees wishing to take up employment with private sector organisations to fully inform Defence of the situation. However, this does not always take place and has limited Defence’s capacity to manage potential conflicts of interest.19 Defence should reinforce its conflict of interest and post-separation policies to its ADF members and APS staff, particularly the need for transparency concerning any future private sector and Defence Reservist employment, and introduce practical measures to achieve consistent application of policy across the Defence Organisation. Defence could also provide illustrative examples of certain situations or behaviours requiring close management, including: related post-separation employment, Reservists undertaking private business with Defence, personal business interests and requests for favours.

58. From time-to-time Defence needs to dispose of non-ADF SME. While unusual and unpredictable, these instances impose a workload on Defence, and require planning and funding, in common with more conventional disposals. In the case of the Russian-made military helicopters flown to Australia in 199720, Defence has been incurring some unquantified cost in storing them at Tindal for the better part of two decades. Greater awareness of such costs and the assignment of responsibility within Defence for disposal of SME that currently lacks a clear internal ‘owner’ would assist in effective disposal of such equipment.

Entity response

59. Defence provided the following response to the proposed audit report:

Following a request from the Secretary of Defence and the Chief of the Defence Force to the Auditor-General in April 2013, Defence thanks the Auditor-General for recognising concerns around the management of major equipment disposal.

Defence welcomes the thoroughness of the review and agrees with the recommendations that will help to improve Defence’s governance around disposal management.

Defence acknowledges that the disposal of military assets is an area of concern and that this important aspect of asset management appears to have not had the same level of attention relative to higher profile acquisition, sustainment and operational activities. Defence appreciates the analysis provided by ANAO and will undertake to address the shortcomings in policy and performance.

The audit has highlighted the broad range of issues that must be considered in planning for disposal of major equipments. The audit report indicates that Defence does, for the most part, address the majority of these considerations, but that policy and guidance has been deficient which leads to the difficulty in achieving consistently high standards across the wide range of disposal types.

The report includes a chapter on the treatment of hazardous materials and draws attention to Defence’s handling of asbestos containing material through the disposal process. Defence seeks to ensure that all hazardous materials are properly considered and managed, and that it complies with all of its legal obligations, when undertaking the disposal of Defence equipment.

Defence considers that the chapter overstates the risk associated with non-friable forms of asbestos that might still be in equipment subject to disposal.21 Defence considers the residual risk posed by exposure to asbestos in the B-vehicles is no greater than that inherent in a wide range of vehicles of similar vintage which are also still saleable. However, Defence has taken steps to address the concerns raised in this report. Specifically, Defence has delayed the B-vehicles disposals to allow time to ensure Defence’s asbestos management policies are both responsible and pragmatic.

The report validates Defence’s concerns regarding cost implications for the Commonwealth and the potential for future liability arising from gifting of Defence assets, albeit with positive intent.

This report also rightly serves to remind Defence that there are broader considerations other than revenue that are important to the Commonwealth when planning the disposal of specialist military equipment.

60. The ANAO also sent extracts from the proposed report to the Department of Finance (Finance) and to three commercial parties whom the ANAO considered had a special interest in the content of those extracts. The two responses received, from Finance and Omega Air, are at Appendix 2.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 (paragraph 2.59) |

To rationalise and simplify its existing framework of rules and guidelines for disposal of specialist military equipment, the ANAO recommends that Defence:

Defence response: Agreed Finance response: Supported |

|

Recommendation No. 2 (paragraph 3.93) |

The ANAO recommends that, to improve the future management of the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment, Defence identifies, for each major disposal, a project manager with the authority, access to funding through appropriate protocols and responsibility for completing that disposal in accordance with Defence guidance and requirements. Defence response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 (paragraph 3.95) |

The ANAO recommends that, to improve the future management of the disposal of Defence specialist military equipment, Defence puts in place the arrangements necessary to identify all significant costs it incurs in each such disposal (including personnel costs, the costs of internal and external legal advice, management of unique spares and so on), and reports on these costs after each such disposal. Defence response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 4 (paragraph 6.82) |

To bring its instructions and guidelines that address gifting of Defence assets into alignment with the requirements of the resource management framework, the ANAO recommends that Defence promptly review all such material. This could be undertaken as part of the review recommended in Recommendation No. 1. Defence response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 5 (paragraph 7.39) |

The ANAO recommends that Defence:

Defence response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of disposals of specialist military equipment in Defence. It also introduces the audit, including the audit objective, scope and approach.

An outline of Defence’s asset disposals

Defence assets

1.1 Defence manages approximately $75 billion of Commonwealth assets including about $41 billion of specialist military equipment (SME).22 Over the next 15 years Defence expects to replace or upgrade up to 85 per cent of its military equipment, including SME. During this time, Defence plans to dispose of up to 22 ships; 14 boats; 70 combat aircraft and 100 other aircraft; 110 helicopters; 470 armoured vehicles; 10 000 other vehicles; and a range of communications systems, weapons and explosive ordnance. This would be the biggest disposal of military equipment since World War II.

1.2 The disposal of Defence SME is an integral part of managing the asset through its life cycle. Disposal is the final phase in that life cycle, and requires the appropriate assessment and treatment of risks relating to specific items of SME. An institutional risk is that within Defence, disposal may receive insufficient attention, as new capability and the transition to it attracts higher priority. However, this does not diminish Defence’s responsibility for the proper management of public resources under its control.23

1.3 When disposing of Defence assets, such as SME, Defence managers are required to seek the best outcome for the Commonwealth. That outcome might not be represented simply by revenue from sales. Decision makers need to take account of the costs of disposal (which can be substantial), any heritage aspects to the equipment being disposed of, restrictions on the disposal due to international obligations or agreements with the original supplier, and a range of risks, including hazardous substances the equipment may contain and potential reputational risk to Defence and the Commonwealth.

1.4 Defence withdraws SME from service because it is either surplus to, or no longer suitable for, its requirements. Assets that are no longer required may be:

- re-used within Defence for different purposes, for example, as training aids, for spares or components, for research, or as targets;

- retained by Defence for heritage or display purposes, for example, by transfer to Defence-managed museums and history units or as ‘gate guards’ outside Defence establishments;

- transferred to another Commonwealth Government entity, for example, the Australian War Memorial;

- gifted to Australian state or territory governments, foreign governments, or non-government heritage/community organisations;

- sold by tender, auction or private treaty as a going concern, for historical or display purposes, for spare parts or for scrap; or

- destroyed.

1.5 Proper disposal of SME requires Defence to observe legislative and policy requirements, and to consider community interests and expectations, including:

- over the period under consideration, the financial framework require-ments established under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and regulations under the Act24;

- military heritage interests and community expectations as to the availability of old military equipment for display;

- a need to deal with hazardous substances (such as asbestos) and workplace health and safety;

- Australian Defence export controls and, in particular, the requirements of the Standing Inter-Departmental Committee on Defence Exports;

- US ‘International Traffic in Arms Regulations’ (ITAR); and

- environmental compliance; for example, delays were incurred with scuttling of ex-HMAS Adelaide, where higher standards were imposed by the courts following environmental and community concerns.

Defence’s organisational arrangements for disposals

1.6 Disposal of the full range of Defence assets is handled by several Defence Groups:

- Joint Logistics Command (JLC) disposes of Defence inventory items, weapons and artillery;

- Chief Information Officer Group disposes of information technology equipment;

- Defence Support Group disposes of real estate;

- Munitions Branch and Guided Weapons Branch in the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) disposes of surplus explosive ordnance;

- Joint Fuels and Lubricants Agency in DMO disposes of fuels and lubricants;

- Land Systems Division in DMO disposes of commercial vehicles; and

- the Directorate of Disposals and Sales (DAS) in the Australian Military Sales Office (AMSO; a branch of DMO’s Defence Industry Division) has a co-ordinating role for the disposal of SME.

1.7 SME disposals are complex. AMSO has identified that some 25 organisational areas across Defence (including DMO) can be stakeholders in the disposal of SME.25

Development of organisational arrangements for SME disposals

1.8 Defence first created a single point of reference for the development and promulgation of disposals policy in 1997. This occurred when it formed the internal ADF Disposals and Marketing Agency (ADF DMA), a tri-service organisation which amalgamated a number of functions.

1.9 Since DMO was formed in July 2000, the SME disposals function has been moved several times internally. At the outset, ADF DMA was absorbed into DMO and managed under various organisational structures before being transferred to the Defence Asset and Inventory Management Branch, in DMO’s Finance Division, in January 2008. ADF DMA was renamed ‘Defence Disposals Agency’ (DDA) in July 2008. In August 2010, DDA was moved to DMO’s Acquisition and Sustainment Reform Division and then, in September 2011, to DMO’s Financial Reporting and Policy Branch in Finance Division.

1.10 On 1 June 2012, DDA was moved to AMSO in DMO’s Commercial and Industry Programs Division. In November 2012 the agency was renamed ‘Disposals and Sales’ (DAS). On 1 July 2013, as part of the broader DMO Commercial Group restructure, AMSO became part of the new Defence Industry Division. To avoid confusion from the various changes, DAS and its predecessors are referred to as ‘Defence Disposals’ in this audit report.

1.11 The then Minister for Defence Materiel announced major reforms to disposals in June 2011.26 The reform objective was to generate revenue from Defence disposals, to be achieved by managing disposals as a commercially-focused major program.

1.12 Defence’s 2011–12 Annual Report identifies four priority areas for Defence Disposals:

- to reduce if not eliminate Defence major disposals cost;

- to return funding to the sustainment of current capability;

- to generate and then maximise revenue from the sale of Defence’s military assets; and

- to ensure that Defence heritage, particularly war heritage, is appropriately recognised and preserved.27

Recent difficulties with Defence SME disposals

1.13 Recently, Defence has experienced difficulties with two major disposals. One was Defence’s sale of its fleet of Boeing 707 air-to-air refuelling aircraft and the other was Defence’s sale of part of its fleet of Caribou aircraft. Both disposals led to reviews by DMO’s legal counsel. The latter disposal also led to an investigation by the Inspector-General of Defence (IGD) and an internal audit by Defence’s Chief Audit Executive.

1.14 In July 2013, DMO commissioned a consultant to review its disposals function to identify the underlying problems for some specific disposals cases, including the two disposals mentioned above, and to inform an agenda for disposals reform. The consultant completed the report of the review in mid- October 2013. The report found ‘a systematic shortcoming in the way in which major disposals have been conducted’ and made six recommendations to improve disposal activities.

1.15 DMO has made organisational and staffing changes, has been revising disposals policy, developing templates and documenting processes for disposals. This work was continuing during the audit.

About the audit

1.16 In April 2013, the Secretary of the Department of Defence and the then Chief of the Defence Force, in light of the difficulties mentioned above, wrote to the Auditor-General asking that the ANAO consider conducting a performance audit of Defence SME disposals during 2013–14. The Auditor-General agreed to commence a performance audit as part of the ANAO’s 2013–14 work program. The audit began in November 2013.

1.17 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the disposal of specialist military equipment. The audit considered (i) whether Defence has conducted disposals in accordance with applicable Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements and Defence policies, guidelines and instructions; and (ii) where relevant rules have been departed from, the reasons and consequences. The audit examined Defence records of selected SME disposals that occurred over the last 15 years,28 especially the period from 2005 to 2013, including actions in response to disposals not proceeding as intended.29

1.18 The audit focuses upon Defence disposals from the point where a decision has been made to withdraw an item of Defence SME. That is, the audit is not concerned with the question of maintaining capability, which is one that must be foremost in the capability manager’s mind when he or she sets a planned withdrawal date and decides to dispose of SME.

1.19 Finally, the audit considered recent DMO reforms to the disposals process, including the agenda following the then Minister for Defence Materiel’s announcement in 2011 about reform of disposals (paragraph 1.11). It also considered Defence’s progress with this agenda, including efforts to obtain better value-for-money for the Commonwealth from SME disposals.

1.20 The audit drew on the records held by Defence, including electronic records retained by Defence Disposals. Defence has no database, register or other systematic collection of records dedicated to tracking its SME disposals. Therefore, relevant material sometimes needed to be gathered from diverse locations. The audit also drew on some of the investigation work conducted by Defence before the audit commenced (paragraph 1.13). The auditors visited a small number of recipients of items of military equipment disposed of by Defence to gather their perspectives on the operation of disposals.

1.21 The high-level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s performance were:

- Defence policies and procedures governing disposals comply with all relevant Commonwealth legislation and policy;

- Defence disposal of SME is carried out effectively, in accordance with relevant legislation, policies and instructions; and

- recent reforms in the management of Defence disposals are suitably designed and progressing effectively.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $571 000.

Structure of the report

1.23 The remainder of the report is arranged as follows:

|

Chapter |

Content |

|

2. Disposals Framework |

Examines the Commonwealth and Defence frameworks for disposal of Defence SME. |

|

3. Reform of Disposals |

Considers the two initiatives in recent years to reform SME disposals in Defence. |

|

4. Major Case Studies–Caribou and Boeing 707 Aircraft, and Army B Vehicles |

Examines two major disposals that were troublesome for Defence and prompted this performance audit—the disposal of the Caribou and Boeing 707 aircraft. It also examines shortcomings in the more recent disposal of Army B Vehicles. |

|

5. Managing Hazardous Substances in Disposals |

Considers Defence’s management of hazardous substances in carrying out its disposal of SME, focusing on asbestos. |

|

6. Gifting Defence Specialist Military Equipment |

Examines the Australian Government’s gifting rules and how Defence has set about gifting SME assets that are no longer required. |

|

7. Managing Other Risks |

Considers Defence’s treatment of specific risks in managing certain disposals, including restrictions imposed on arms purchased from the US, conflict of interest risks, and disposal of non-ADF equipment. |

2. Disposals Framework

This chapter examines the Commonwealth and Defence frameworks for disposal of Defence SME.

The framework for disposal of Defence assets

2.1 Disposal of SME requires Defence to follow a range of legal and policy requirements relating to: the proper use of Commonwealth resources; dealing with hazardous substances; workplace health and safety; environmental issues such as those associated with the use of ships as dive wrecks; and restrictions on the re-transfer of military items, particularly those of US origin.

2.2 The audit examined:

- the Commonwealth framework for the disposal of Defence SME over the period under consideration. For this period, the framework included the former FMA Act and the Finance Minister to Chief Executives gifting delegation made under the FMA Act;

- Defence’s disposals policy framework. This comprised the Defence and DMO Chief Executives’ Instructions made under the FMA Act and a range of internal policy and procedural documents; and

- difficulties with the existing framework.30

2.3 The audit considers the rules for gifting Defence assets separately, as Defence guidance documents vary in their detail on this topic. This is set out in Chapter 6, with an analysis of specific examples of gifting Defence SME.

2.4 Given the wide range of matters relevant to disposal of major Defence equipment, this chapter has not sought to catalogue all Commonwealth legislation or international arrangements that Defence must take into account. However, where these rules are relevant to particular disposals they are discussed in the appropriate chapter of this report. For example, Chapter 5 (which addresses management of hazardous substances) refers to legislation on asbestos management in Australia, and Chapter 7 (which deals with a range of disposal risks) discusses Defence’s adherence to the US ITAR.

The Commonwealth’s disposals policy framework

2.5 For the period under consideration, the FMA Act established the Commonwealth financial framework for the management of financial and other resources within the Australian Government. The FMA Act, therefore, also provided the relevant framework for disposal of Commonwealth assets.31 Major disposals in Defence, more often than not, required consideration of the Act for two reasons: the asset is a Commonwealth resource; and the disposal process consumes Commonwealth resources, sometimes exceeding the value of the asset.

Framework established by the FMA Act

2.6 Under the FMA Act, responsibility for managing Commonwealth property rested with Commonwealth agency chief executives. This responsibility was governed by the principle-based requirements in the Act, in particular, the requirement to promote the proper use of Commonwealth resources (s. 44) and Part 6 of the Act, which dealt with the control and management of public property.32

2.7 Section 44 of the FMA Act established a positive and personal obligation on each agency head to manage Commonwealth resources in a way that promoted their efficient, effective, economical and ethical use and was not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth.33 Section 44 was an overarching requirement applying to all aspects of an agency’s resource management, including the management of ‘public money’ and ‘public property’, the administration of programs, the provision of grants, and procurement.

2.8 In addition, there were several specific references to the disposal of Commonwealth assets within the FMA Act and in the associated FMA (Finance Minister to Chief Executives) Delegations, under which the Finance Minister delegated specific powers of the Finance Minister to Chief Executives. One of these powers was the power to gift Commonwealth assets.34 The delegation to Chief Executives included specific directions from the Finance Minister, with which delegates had to comply.

2.9 The FMA Act, s. 41, required that ‘an official or Minister must not misapply public property or improperly dispose of, or improperly use, public property’.35 Section 43 of the FMA Act explicitly prohibited disposal by gift, except in specific circumstances:

An official or Minister must not make a gift of public property unless:

(a) the making of the gift is expressly authorised by law; or

(b) the Finance Minister has given written approval to the gift being made; or

(c) the Commonwealth acquired the property to use it as a gift.36

2.10 The Commonwealth’s general policy for the disposal of public property was stated in the Finance Minister to Chief Executives gifting delegation made under the FMA Act. The policy was that, wherever it was economical to do so, the property should be disposed of at market price or transferred to another Commonwealth agency. Specifically, the property being disposed of should:

(a) be sold at market price in order to maximise return to the Commonwealth; or

(b) otherwise, should be transferred (with or without payment) to another Commonwealth Agency with a need for an asset of that kind.37

2.11 Further directions on gifting are set out in the delegation. These are discussed in Chapter 6, which considers both the gifting framework and how Defence has set about the gifting of SME assets that are no longer required.

Relevance of Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines and Rules

2.12 Under the FMA Act, Regulation 7 (1) allowed the Finance Minister to issue guidelines in relation to procurement and Regulation 7(3) required an official undertaking procurement to act in accordance with such guidelines.

2.13 Until 2012, these guidelines took the form of the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs). The CPGs were replaced on 1 July 2012 by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). At their introduction the CPRs were presented as an instrument which ‘combines the requirements of Australia’s international trade obligations, government policy and good practice in procurement into a core set of rules which apply to Commonwealth procurement.’

2.14 The applicability over the years of the CPGs/CPRs to disposals—as contrasted with procurement—has required clarification. FMA Regulation 7(1) has always included a reference ((d), below) to disposal of public property:

(1) The Finance Minister may issue guidelines in relation to procurement, including:

(a) procurement policies and processes; and

(b) requirements regarding the publication of procurement details; and

(c) requirements regarding entering into procurement arrangements; and

(d) requirements regarding the disposal of public property.

2.15 While there have not been any separate guidelines issued by the Finance Minister in relation to disposal, the 2005 edition of the CPGs included the statement ‘Procurement also extends to the ultimate disposal of property at the end of its useful life.’ This reference appeared to extend the application of the CPGs to disposal action. However, a Finance Circular issued the following year provided a clarification which meant that:

the CPGs have no application to the disposal of public property. Rather, the management of disposals falls within the responsibilities of an agency’s Chief Executive under s 44 of the FMA Act (promoting efficient, effective and ethical use of Commonwealth resources).38

2.16 The CPGs became law on 1 July 2009 and were further amended when the CPRs replaced them in 2012. The CPRs were perceived as a clearer and more concise set of rules with no major differences from the CPGs except terminology. However, the CPRs introduced a minor revision to the definition of procurement:

Procurement continues through the processes of risk assessment, seeking and evaluating alternative solutions, the awarding of a contract, the delivery of and payment for the goods and services and, where relevant, the ongoing management of the contract and consideration of disposal of goods.

2.17 As there is no explanation of the intended meaning of the words ‘consideration of disposal of goods’ and some Defence equipment is sold by tender, the intended effect of these changes on disposal practice is not clear in the wording. However, the CPRs state that procurement does not include (among other items) sales by tender.39 Further, in October 2014, Finance confirmed to the ANAO that ‘the CPRs do require consideration of whole of life costs, including disposals, but only to the extent that it may or should affect decision making regarding the initial procurement.’40

2.18 While the Australian Government’s procurement and grants frameworks are now well-developed, with consolidated whole-of-government guidance to support their application (in the form of the CPRs and Commonwealth Grant Guidelines), the disposals framework remains less well-developed. The only definitive statement of Commonwealth policy is that contained in the Finance Minister’s Delegation Part 17.2 (1), quoted above (paragraph 2.10), with no further elaboration above agency-level rules. These rules are considered in the following paragraphs.

Defence’s disposals policy framework

2.19 As the CPRs do not apply to disposals, the next level of guidance below the FMA Act is that produced by Defence. Defence has an extensive system of instructions, manuals and directives referred to as the ‘System of Defence Instructions’ (SoDI). The first to be considered are the former Chief Executive’s Instructions (CEIs), issued under the FMA Act.41

Defence and DMO Chief Executives’ Instructions

2.20 One way chief executives discharged their responsibility to promote the proper use of public resources under s. 44 of the FMA Act was by ensuring that their agencies had appropriate internal controls and guidance in place, such as CEIs and operational guidelines.

2.21 The Department of Defence and DMO were separate agencies for the purposes of the FMA Act.42 Each agency’s Chief Executive issued CEIs applicable to their own agency.43 Disposal of Defence SME assets is an activity that DMO carries out on behalf of Defence. Therefore, the DMO CEIs referred DMO officials responsible for disposing of Defence assets to Defence’s policies and procedures for disposals. They required those DMO officials to:

- comply with Defence’s CEIs and any other relevant CEI or policy and procedures relating to the disposal of public property; and

- not approve the disposal of Defence-controlled public property unless they hold a delegation under the relevant Defence delegation schedule issued by the Secretary of Defence [that is, the Financial Delegations Manual (FINMAN 2)].44

2.22 Defence’s CEIs also required assets to be disposed of in accordance with policies endorsed by the Secretary and/or the Chief of the Defence Force. They referred to Defence Instruction (General) LOG 4-3-008 Disposal of Defence Assets (the Disposal Instruction), discussed below, as the primary reference for direction and guidance on policy for effective and efficient asset disposal.45

Defence Instruction (General) LOG 4-3-008 Disposal of Defence Assets

2.23 The Disposal Instruction, issued in 2006, set out policy to be followed once a decision had been made to dispose of an asset. Despite being in need of updating it remained the primary source of mandatory policy for Defence during this audit.46

2.24 Under the Disposal Instruction, the decision to dispose of assets rested with the relevant manager in Defence. For major platforms this is the capability manager (most often a Service Chief).47

2.25 The Disposal Instruction established the following six mandatory policy directives that govern the disposal of Defence assets:

- disposals planning and management must be conducted as part of the lifecycle management process;

- all disposal activities are to be managed and conducted openly, fairly and equitably, and in a manner that will withstand government, public and international scrutiny;

- officials managing disposals are to optimise outcomes for Defence when implementing any disposal strategy48;

- when disposing or gifting public property it is mandatory to comply with the FMA Act; Defence and DMO policy on asset management and financial management delegation schedules; and International Treaty obligations;

- weapons are not to be gifted, sold or transferred without the appropriate approval; and

- all weapons not gifted, sold or transferred to other organisations are to be disposed of, or destroyed, in a manner appropriate to the type of weapon.49

2.26 The Disposal Instruction also required that auditable records of disposals be maintained and retained to demonstrate adherence to Defence logistics governance processes, and that disposal records be signed original documents that allowed the content to be traced to the primary asset management system.

2.27 As Figure 2.1 illustrates, there are three levels of disposal in Defence, Major, Routine and Unit. This performance audit focuses on disposals defined by Defence as ‘Major disposals’, that is: those items which are expected to recover more than $1.0 million in revenue upon their disposal, or are capability platforms, weapon systems or items of significant public interest which require specialist disposal action and planning.

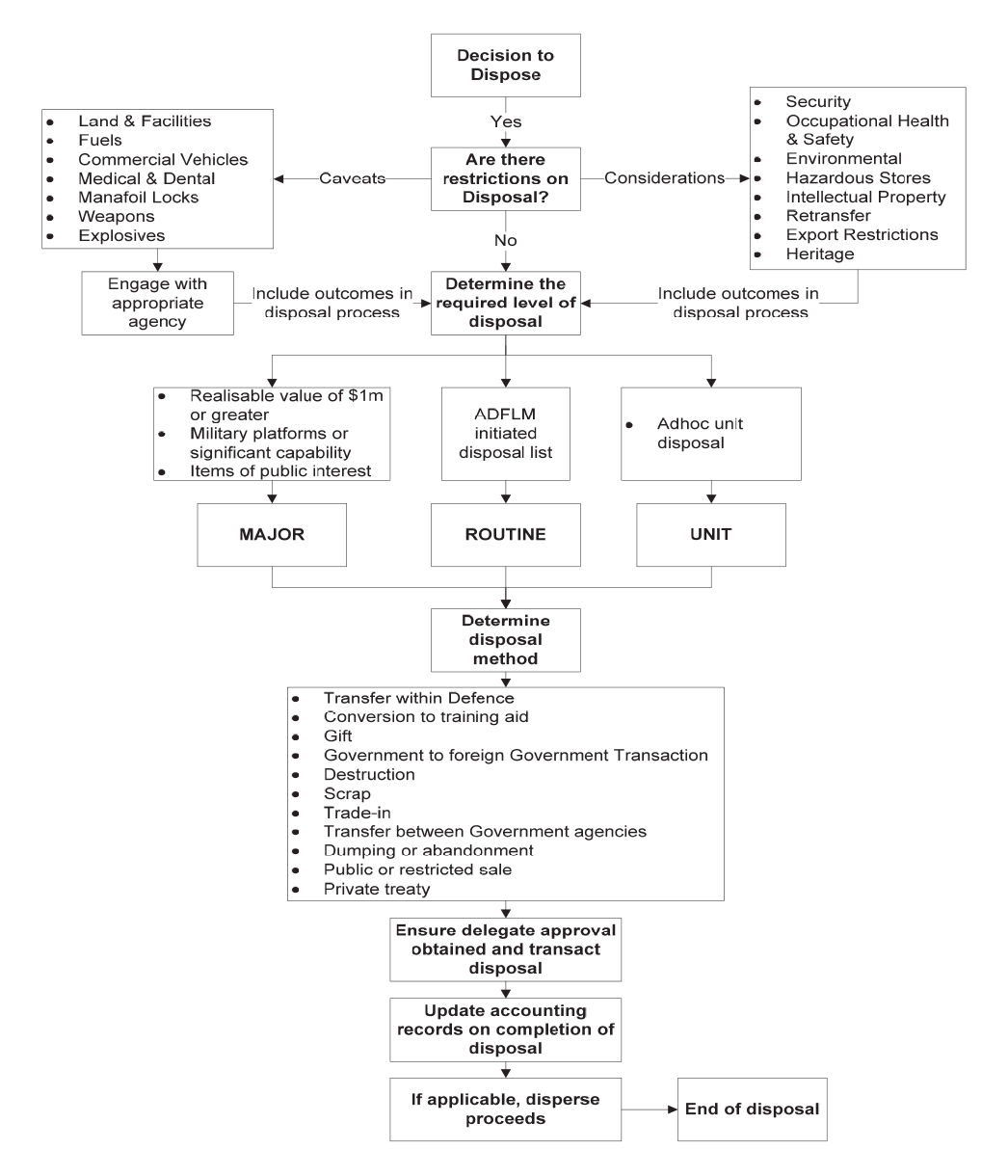

Figure 2.1: Defence Disposals Flowchart

Source: Adapted from Defence, DI(G) LOG 4-3-008 Disposal of Defence Assets. The flowchart is reproduced in the Electronic Supply Chain Manual (ESCM) Volume 4, s. 7, Chapter 1.

Note: ADFLM = Australian Defence Force Logistics Manager.

Other Defence manuals

2.28 Other Defence and DMO manuals contain further guidance relevant to disposals over the period considered by the audit. These include:

- the Defence Logistics Manual (DEFLOGMAN) Series (including Part 2, Volume 5, Defence Inventory and Assets Manual50 and Part 3, the Electronic Supply Chain Manual (ESCM));

- the DMO Acquisition and Sustainment Manual; and

- the DMO standard operating procedure for managing disposals (SOP (FD) 01-0-073).51

Other directives

2.29 From time to time, senior Defence managers issue directives to address new or emerging issues that affect disposals, adding to the rules Defence Disposals must follow. An example is the directive by the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) in October 2009 prohibiting the sale or gifting of Defence equipment containing asbestos that would be accessible to future users, and which would be a potential health risk. Implementation of this directive is considered in Chapter 5.

Difficulties with the existing framework

2.30 The audit observed a number of difficulties with the existing Defence disposals framework, relating to:

- the structure, consistency and completeness of the guidance;

- a lack of rigour in disposal tender evaluations;

- cases where disposals become procurements; and

- the clarity of guidance relating to approvals for disposal activity.

2.31 Chapter 3 examines the lack of clarity in management responsibility for SME disposals in Defence policy and guidance. In addition, difficulties relating to varying interpretations of the gifting rules are examined in Chapter 6.

The structure, consistency and completeness of the guidance

2.32 Instructions and guidance to Defence staff on disposal action lie in an extensive range of documents, of varying vintage and completeness. This may be due in part to the number of separate parts of a large organisation which have a legitimate interest. However, having multiple points of reference may not be necessary or helpful. It is more resource-intensive to update, provides a potential source of error and inconsistency, and creates challenges for personnel seeking to keep abreast of requirements.

2.33 Some of the existing guidance is inconsistent across different sources and possibly incorrect. This has been analysed for the rules on gifting, and this analysis is set out separately in Chapter 6 (paragraph 6.5 forward).

2.34 The most challenging aspect of this framework for disposals is that, notwithstanding the apparent proliferation of sources of guidance, there is little practical guidance on the interpretation of the policy principles. This was the view, for example, of the Chief Contracting Officer at Richmond on relevant policies regarding disposal of assets in November 2012:

There’s a Defence Instruction General that I read at the time, a DI(G). … And I think there was also a Disposals Manual or something like that I looked at at the time. But when I looked at those policies, they were all very high-level policies and quite vague about the actual governance of the mechanics of a disposal by sale activity.

2.35 Similarly, when asked about the ‘the mandated or stipulated processes, policies, instructions regarding disposals’ the former branch head responsible for Defence Disposals said, in December 2012:

Well, there are none or there are none that I would say would be contemporary or relevant, and that’s where we were moving to, to come up with a business process … that we thought was relevant and would work, then our aim was to actually drive … some of the business process and business policy change.52

2.36 Defence Disposals obtained external advice on policies applicable to asset disposal in mid-2011. That advice noted that: ‘there appears to be very little guidance for personnel involved in disposal of assets which explains the policies and processes that should be followed, and issues and factors that should be considered, in a way that the [Defence Procurement Policy Manual] does for procurement.’

Example of incomplete guidance

2.37 An example of incomplete guidance relates to the cost-effectiveness of disposals. Policy Directive 3 in the Disposal Instruction requires officials to optimise the outcome for Defence when implementing any disposal strategy. The Instruction explains that ‘this may not be limited to monetary return, as there is a number of options for consideration when determining a disposal strategy.’ However, the Instruction provides neither an explanation nor examples of what is meant by ‘not limited to monetary return’, nor any guidance as to how the monetary return itself is to be estimated and an overall assessment made. It references the Defence Supply Chain Manual53 and the Defence Procurement Policy Manual for further guidance on selecting a method of disposal.54

2.38 In contrast, the ESCM usefully points out that estimates of both costs and revenue from the disposal must be taken into account when selecting a disposal method:

When considering disposal options, the full anticipated sale value is to be used. This is the estimate of the market value less cost of sale. It provides a comparative basis to determine the most cost-effective means of disposal.

2.39 However, the ESCM provides no guidance on how to estimate costs or which items should be considered for inclusion in the costing.

2.40 The DMO standard operating procedure does not help on this point, largely re-stating the desirability of taking into account the cost-effectiveness of the disposal method:

Once assets are identified for disposal, the most appropriate means of disposal needs to be identified taking into account cost effectiveness and any known restrictions on disposal including export and on-selling limitations and the heritage value of the item.

2.41 In practice, there are many elements that need to be considered in estimating the cost-effectiveness of a method of disposal, including elements with a non-financial character, such as the equipment’s perceived merit for heritage and display. The key elements with financial implications include:

- the expected revenue from sale. This will depend on the condition of the equipment and its potential uses. The revenue may also be sensitive to market conditions (and, therefore, timing of sale), including the availability of similar items from other countries;

- the cost of preparing items for sale (demilitarisation, remediation, hazardous substance removal, repainting);

- storage/mooring/accommodation costs (or other scarce Defence resources) until disposal takes place;

- transport/towing/delivery costs, particularly if specialist services are required;

- destruction costs (dismantling, explosive demolition, burying, sinking);

- identification, collection and disposal of unique spares associated with the equipment (these may be distributed widely among Defence facilities);

- legal costs (internal and external)55;

- sales costs, for example, where an agent or other party is involved in arrangements to sell assets on to a third party and attracts a portion of the payment received from that third party;

- the expected time taken to obtain ITAR approval. Although not a cost in itself, the delay can cause increases in other costs, such as storage/mooring costs and, potentially, a delay can lead to the transaction taking place in different market conditions;

- residual maintenance costs. It will be important to make a sound and timely judgement as to when to cease maintenance on the equipment and the depth of any further maintenance before disposal56; and

- personnel costs (including salary and overheads) in all of the above activities, including for the relevant Systems Program Office (SPO) and disposals personnel. Personnel costs are less visible to the managers involved but, nevertheless, need to be taken into account.

2.42 Awareness of these costs could also reveal matters needing active internal management within Defence during the disposal. For example, a disposal manager may need to manage expectations as to how long a request-for-offer process or obtaining ITAR approval may take, as this may have cost implications for the SPO with custody of the equipment to be disposed of.57

DMO Disposals Review

2.43 The 2013 DMO Disposals Review also emphasised the lack of lower-level policy and procedural guidelines:

While [Defence] Disposals personnel appear to be aware of the requirements of [the] legislation and policy framework, a number of disposal activities appear to have suffered from a failure to comply with policy and due process—resulting in internal and external criticisms of those activities.

These failures appear to have resulted from two primary issues—first, a lack of detailed and consistent policy guidance and ‘checkpoints’ for disposal processes, and second, a historical culture of focusing on achieving outcomes (as approved by the Minister), rather than following due process.

2.44 The review acknowledged that considerable work had been done but there was still significant outstanding work to implement a comprehensive suite of disposals processes and procedures.58

2.45 The Disposals Review’s first recommendation was that Defence review in detail the legislation and policy applicable to disposals, and develop a single guidance document to set out clearly the applicable legislative and policy framework. In December 2013, DMO engaged the consultant who undertook the Disposals Review to draft such a document. The consultant had, by April 2014, provided two draft ‘deliverables’. In late April 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that:

AMSO has provided initial feedback to [the consultant] indicating that the draft deliverables do not meet our requirements and will provide more guidance.

Separately, [the consultant] and AGS (who was involved in providing legal advice in the lead up to the establishment of AMSO) will be invited to attend a planning workshop to support the legislation policy review and to assist in proposing remediation actions.59

Lack of rigour in disposal tender evaluations

2.46 Lack of rigour in the Defence disposals framework also arose in the project in 2012 to dispose of Defence’s older fleets of Army B Vehicles.60 This came to light following a complaint about Defence’s selection process for a company or entity to help it dispose of these vehicles.61

2.47 The complaint concerned Defence’s evaluation of the tenders it received. Defence then instigated a range of reviews and obtained legal advice. The advice pointed out that: