Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Cyber Security Supply Chain Risks

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- $14.8 billion committed to Information Communications Technology related goods and services in 2021–22 by Australian Government entities.

- Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) has reported that contractors holding government information had a significant increase in malicious cyber activities.

- Previous audits identified high rates of non‐compliance with mandatory Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) cyber security requirements and poor administration of government procurements, including monitoring and treatment of non‐compliance with contractual requirements.

Key facts

- The Commonwealth Procurement Rules, which govern how entities procure goods and services, was updated in December 2020 to include considerations for cyber security risks.

- PSPF Policy 6 and Policy 10 outline the mandatory requirements for non-corporate Commonwealth entities to manage cyber security threats arising from contracted goods and service providers.

What did we find?

- The implementation of arrangements by selected entities for managing cyber security risks within procurements and specific contracted providers under the PSPF have not been fully effective.

- ATO has largely effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks in accordance with the PSPF. AFP and DFAT have partially effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the PSPF.

- AFP and DFAT do not manage compliance of contracted providers with the PSPF requirements for cyber security. ATO had largely established arrangements to manage compliance of their contracted providers with limited assurance over reporting and methods of enforcement of the PSPF requirements for cyber security.

What did we recommend?

- There were five recommendations aimed at improving management of cyber security risks within procurements and monitoring of contracted provider compliance with security terms and conditions.

51%

of non-corporate Commonwealth entities reported not fully implementing PSPF Policy 6 in 2020–21.

72%

of non-corporate Commonwealth entities reported not fully implementing PSPF Policy 10 in 2020–21.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australian Government entities deliver a wide range of digital services to the community and hold large volumes of data across their computer networks, some of which is highly sensitive. Australian Government entities rely on a system of organisations, people, activities, information, and resources to deliver digital services and to maintain the security of government computer networks and data. This system can be referred to as an entity’s supply chain.1

2. Cyber security continues to be a risk for all Australian individuals, organisations and government entities, with over 67,500 cybercrimes being reported to the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) in 2020–21 — an increase of 13 per cent since the previous financial year.2 In addition, ACSC has reported that contractors holding government information had a significant increase in malicious cyber activities.3 This increases the cyber security risks arising from an entity’s supply chain as the risks can originate from suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers that support products and services used by the entity. ACSC recommends that all Australian organisations prioritise the implementation of the Essential Eight Maturity Model (Essential Eight), including knowing their networks and evaluating risks associated with cyber supply chains.

3. The Attorney-General has established the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) as Australian Government policy and non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs) subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 must apply the PSPF.4 PSPF Policy 5: Reporting on security (Policy 5) sets out the maturity self-assessment model for annual PSPF reporting. The maturity self-assessment model requires entities to assess their security capability and implementation of the PSPF requirements.5 The PSPF specifies that the ‘Managing’ maturity level provides the minimum required level of protection of an entity’s people, information and assets.6

4. Requirements for NCEs to manage cyber security supply chain risks are outlined in PSPF Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and service providers (Policy 6) and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The CPRs were updated in December 2020 to include managing cyber security risks within government procurements and contracts. These are supported by requirements in PSPF Policy 10: Safeguarding data from cyber threats (Policy 10), which outlines the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Since April 2013, the PSPF has mandated NCEs implement four of the ACSC’s Essential Eight Maturity Model, known as the Top Four.7

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The ANAO has conducted a series of audits on cyber security and identified ongoing low levels of cyber resilience in NCEs and high rates of non‐compliance with the Top Four mitigation strategies. The high-rates of non-compliance continues to be an issue as AGD’s PSPF Assessment Report 2020–21 indicated 72 per cent of NCEs reported not fully implementing Policy 10 requirements.8 The Top Four mitigation strategies were mandated by the PSPF in 2013. Auditor‐General Report No. 32 2020–21 Cyber Security Strategies of Non‐Corporate Commonwealth Entities noted that:

The 2018‐19 PSPF assessment report identified that one of the key challenges faced by the entities who had not achieved the ‘Managing’ maturity level of Policy 10 was reliance on outsourced service providers for information communications technology (ICT) and cyber security services, whereby entities had limited influence or control over the implementation of the mitigation strategies. 9

6. The limited influence and control over outsourced service providers of information communications technology (ICT) and cyber security services increases the cyber security risks arising from an entity’s supply chain. The management of cyber security risks within procurements continues to be challenging for NCEs with 51 per cent being reported in AGD’s PSPF Assessment Report 2020–21 as not fully implementing Policy 6.

7. Auditor‐General Report No. 4 2021‐22 Defence’s Contract Administration — Defence Industry Security Program and Auditor‐General Report No. 6 2021–22 Management of the Civil Maritime Surveillance Services Contract have further indicated poor administration of government procurements, including monitoring and treatment of non‐compliance with contractual requirements. 10

8. The Australian Government has committed $14.8 billion in ICT related goods and services contracts in 2021–22.11 These commitments indicate the Australian Government’s reliance on contracted providers for its ICT capabilities. This dependency on contractors for ICT capabilities and the increase in malicious cyber activities against contractors who hold government information increases the risks associated with government supply chains.12

9. This audit was identified as a Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) priority for 2021-22.

10. This audit will examine the effectiveness of the implementation of Policy 6 by selected NCEs and the effectiveness of selected contracted providers’ compliance with the relevant PSPF requirements relating to procurement cyber security risks. It will provide Parliament transparency and insights on the management of procurement cyber security risks.13

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of selected NCEs’ arrangements for managing cyber security risks within their procurements and specific contracted providers under the PSPF.

12. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following two high-level criteria:

- Have entities established effective arrangements to assess and manage procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the PSPF requirements?

- Have the contracted providers complied with the relevant PSPF requirements?

13. Three NCEs were included in this audit:

- Australian Federal Police (AFP);

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO); and

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

Conclusion

14. The implementation of arrangements by selected entities for managing cyber security risks within procurements and specific contracted providers under the PSPF have not been fully effective.

15. ATO has largely effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks in accordance with the PSPF. AFP and DFAT have partially effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the PSPF.

16. AFP and DFAT do not manage compliance of contracted providers with the PSPF requirements for cyber security. ATO had largely established arrangements to manage compliance of their contracted providers with limited assurance over reporting and methods of enforcement of the PSPF requirements for cyber security.

Supporting findings

Managing cyber security risks in procurements

17. All three entities have defined roles and responsibilities for managing procurement cyber security risks. The procurement teams are responsible for identifying, assessing, and managing cyber security risks within procurements. The entities have cyber security specialists who can provide advice on cyber security risks associated with a procurement.

18. None of the three entities’ processes required procurement teams to consult with cyber security specialists when assessing procurement cyber security risks or when considering mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Of the three entities, ATO has processes for assisting procurement teams with assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks and consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. AFP and DFAT have not implemented processes for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks, including documenting any assessments performed relating to mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

19. All three entities have contract clauses requiring contracted providers to comply with the PSPF, ACSC’s Information Security Manual (ISM) and the respective entities’ policies. ATO performs ongoing assessments of its security terms and conditions to ensure protective security requirements address identified cyber security risks.

20. DFAT and AFP use contract management plans to specify roles and responsibilities for each contract. ATO has a generic contract management plan that covers ICT contracts and is developing detailed plans for each contracted provider. ATO’s generic contract management plan does not detail roles and responsibilities for each ICT contract.

21. All three entities have incident management processes within contracting arrangements. ATO is the only entity that has arrangements for monitoring performance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. However, the ATO has not detailed how non-compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements is to be managed.

22. All selected contracts required contracted providers to adhere to the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements. None of the entities had processes, performance measures and service level agreements related to managing non-compliance with PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements. Further, none of the entities had processes for verifying the reliability of cyber security related performance information provided by contracted providers.

23. AFP and DFAT do not monitor compliance against PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements for the selected contracts. ATO has established a Cyber Threat Assurance Program and risk management processes for assessing compliance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. The assurance program included a quarterly audit of contracted provider implementation of the Top Four mitigation strategies. The risk management processes included the use of risk registers to monitor the implementation of some mandatory PSPF cyber security controls and ATO policy requirements.

Compliance with PSPF requirements

24. ATO had processes for ensuring DXC had implemented the required cyber security controls in accordance with the PSPF requirements. DXC had implemented mitigation strategies relating to patching operating systems and application control.

25. AFP and DFAT had processes for ensuring selected contracted providers had implemented the required cyber security controls in accordance with some of the relevant PSPF requirements. Hitachi had implemented patch management processes for operating systems and applications. AFP had not implemented patch management processes for applications on Hitachi managed servers. Telstra had implemented security measures for restricting administrative privileges to specific network devices. However, Telstra had not implemented patches to operating systems on network devices in accordance with PSPF requirements.

26. ATO has arrangements for monitoring cyber security issues related to the selected contracted provider and specifies contract terms and conditions for monitoring performance for relevant PSPF cyber security and entity policy requirements. None of the entities have specified terms and conditions for managing non-compliance against PSPF and entity internal policy requirements.

27. AFP and DFAT do not have contracting arrangements focussed on monitoring cyber security issues and performance against relevant PSPF cyber security and entity policy requirements.

28. Of the audited entities, ATO was the only entity that had processes for assessing contracted provider compliance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. ATO had also reassessed cyber security terms and conditions for the selected contract.

29. ATO had some processes for ensuring the accuracy of some performance reporting against relevant PSPF requirements. These processes included verification against other information sources, however, the verification activities were not documented. AFP and DFAT did not have processes for validating the accuracy of performance reporting against relevant PSPF requirements. None of the contracted providers had established assurance mechanisms for verifying the information they provide to entities.

30. All three entities have mechanisms within contracts to address deviations in expected performance, including financial penalties, performance, and service credits, but these mechanisms did not cover cyber security risks or controls.14 AFP has patch management timeframes that deviate from PSPF requirements.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.15

To improve the quality of risk assessments:

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve processes and guidance for assessing and managing cyber security risks within procurements, including documenting the consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements; and

- Australian Federal Police, Australian Taxation Office and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade implement processes to assist with identifying when procurement teams are required to consult with cyber security specialists on cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed, agreed in part.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.53

Australian Federal Police, Australian Taxation Office and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade should implement processes for verifying the reliability of performance information and managing non-compliance by contracted providers against the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements, including establishing performance measures focussed on compliance against PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.26

To improve monitoring of security controls:

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade specify requirements relating to the implementation and monitoring of the mandatory Protective Security Policy Framework cyber security requirements in contractual arrangements; and

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish periodic assessments of security terms and conditions of their contracts to address associated cyber security risks.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed, agreed in part.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.37

Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade specify requirements relating to reporting performance against relevant cyber security and entity policy requirements in contractual arrangements.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed in part.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.46

To improve quality of performance reporting:

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish a performance framework supporting Recommendation 4, including validating the accuracy of performance reporting provided by contracted providers in relation to cyber security; and

- Australian Taxation Office improve processes for verifying performance information provided by contracted providers, including documenting verification activities.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed in part.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Summaries of entity responses

Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police did not provide a summary response.

Australian Taxation Office

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) welcomes the review and findings that the ATO is largely effective in managing procurement cyber security risks in accordance with the PSPF. The ATO delivers contemporary digital services, supporting effective and secure transactions for the Australian community and maintains security of our organisations’ network and data. The ATO is committed to improving the way in which we manage cyber security supply chain risks and ensuring client interactions with the ATO remain safe and secure.

We are pleased that the review recognises the work already performed by the ATO in assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks in accordance with the PSPF. The report found the ATO has established arrangements in managing compliance of contracted providers and monitoring performance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Further, the ATO has contract management arrangements and performs ongoing assessment of its security terms and conditions to ensure protective security measures address cyber security risks.

The review has identified opportunities for improvement to our risk assessment processes and performance reporting. The ATO operates under the principle of continuous improvement and welcome the findings from the ANAO to further strengthen the procurement program.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) welcomes this report and the recommendations directed to the department.

Whilst we acknowledge the audit findings regarding the International Network Services Agreement (Telstra), we consider the nature of this arrangement is unique and therefore not reflective of the department’s broader activities. The comparison of activities specific to this contract against DFAT’s Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) reporting has the potential to misrepresent the department’s cyber security capability across our global network and call into question the appropriateness of our PSPF self-assessments and overall compliance.

As noted in the report and its appendices, DFAT has successfully achieved Essential 8 ‘maturity level 2’ compliance under the ACSC’s E8 maturity model. This achievement is reflective of the department’s significant investment in cyber security in recent years and furthermore, the sophisticated cyber security capability that the department maintains. The department has also embedded the consideration of cyber security risks in its contracting arrangements to align with the procurement framework and relevant policies such as the PSPF.

Noting the opportunities to improve, the department will take steps to implement additional processes and policies in line with the report’s recommendations, whilst allowing for whole of government ICT procurement constraints and market conditions. DFAT’s advanced cyber security capability will continue to underpin improvements to departmental policies and processes to ensure cyber security risks are effectively managed.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Procurement and contract management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian Government entities deliver a wide range of digital services to the community. Australian Government entities also hold increasingly large volumes of data across their computer networks, some of which is highly sensitive. Australian Government entities rely on a system of organisations, people, activities, information, and resources to deliver digital services and to maintain the security of government computer networks and data. This system can be referred to as an entity’s supply chain.15

1.2 Cyber security continues to be a risk for all Australian individuals, organisations and government entities, with over 67,500 cybercrimes being reported to the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) in 2020–21 — an increase of 13 per cent since the previous financial year.16 In addition, ACSC has reported that contractors holding government information had a significant increase in malicious cyber activities.17 This increases the cyber security risks arising from an entity’s supply chain as the risks can originate from suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers that support products and services used by the entity. ACSC recommends that all Australian organisations prioritise the implementation of the Essential Eight Maturity Model (Essential Eight), including knowing their networks and evaluating risks associated with cyber supply chains.

1.3 In addition to the ACSC’s guidance, the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) updated the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) in March 2022 to mandate all Essential Eight mitigation strategies from 1 July 2022 for non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs).18 The Attorney-General has established the PSPF as Australian Government policy and NCEs subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 must apply the PSPF.19 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) were updated in December 2020 to include managing cyber security risks within government procurements and contracts.

Protective Security Policy Framework maturity self-assessment model

1.4 PSPF Policy 5: Reporting on security (Policy 5) sets out the maturity self-assessment model for annual PSPF reporting. NCEs are required to report on their security capability using a maturity self-assessment model. Corporate Commonwealth entities and companies are not required to comply with the PSPF. Under the maturity self-assessment model, entities assess and report on their level of implementation and management of the requirements under the PSPF and the maturity of their security capability. The annual PSPF assessment report shows the extent to which an entity has self-assessed it has:

- achieved the security outcomes through effectively implementing and managing requirements under the PSPF;

- implemented and managed security capability at a specific maturity;

- identified the key security risks to its people, information, and assets; and

- taken measures to mitigate or manage identified risks.20

1.5 The maturity self-assessment model requires entities to assess their security capability and implementation of the requirements in the 16 PSPF policies within the context of their specific risk environment and risk tolerances.21 To assess the maturity of the implementation of each PSPF policy, entities are to consider their effectiveness in implementing the core and supporting requirements for each policy. Entities assess the effectiveness of their implementation of the PSPF requirements against four different levels: Partial, Substantial, Full and Excelled. Descriptions for each implementation level are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Implementation levels of PSPF requirements

|

Implementation levela |

Description |

|

Partial |

Requirement is not implemented, is partially progressed or is not well-understood across the entity. |

|

Substantial |

Requirement is largely implemented but may not be fully effective or integrated into business practices. |

|

Full |

Requirement is fully implemented and effective and is integrated, as applicable, into business practices. |

|

Excelled |

Requirement and relevant better-practice guidance are proactively implemented in accordance with the entity’s risk environment, are effective in mitigating security risk and are systematically integrated into business practices. |

Note a: The ‘Yes or No’ implementation level has been excluded from the table as the selected requirements for the audit are evaluated in the PSPF using the levels specified in the table.

Source: PSPF Policy 5: Reporting on security.

1.6 Based on entities’ assessment of their implementation of the requirements for each PSPF policy, the entities can select four maturity levels under the PSPF maturity self-assessment model: Ad hoc, Developing, Managing and Embedded. The selected maturity level is for the overall PSPF Policy. The description for each PSPF maturity level is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Maturity levels of the PSPF maturity self-assessment model

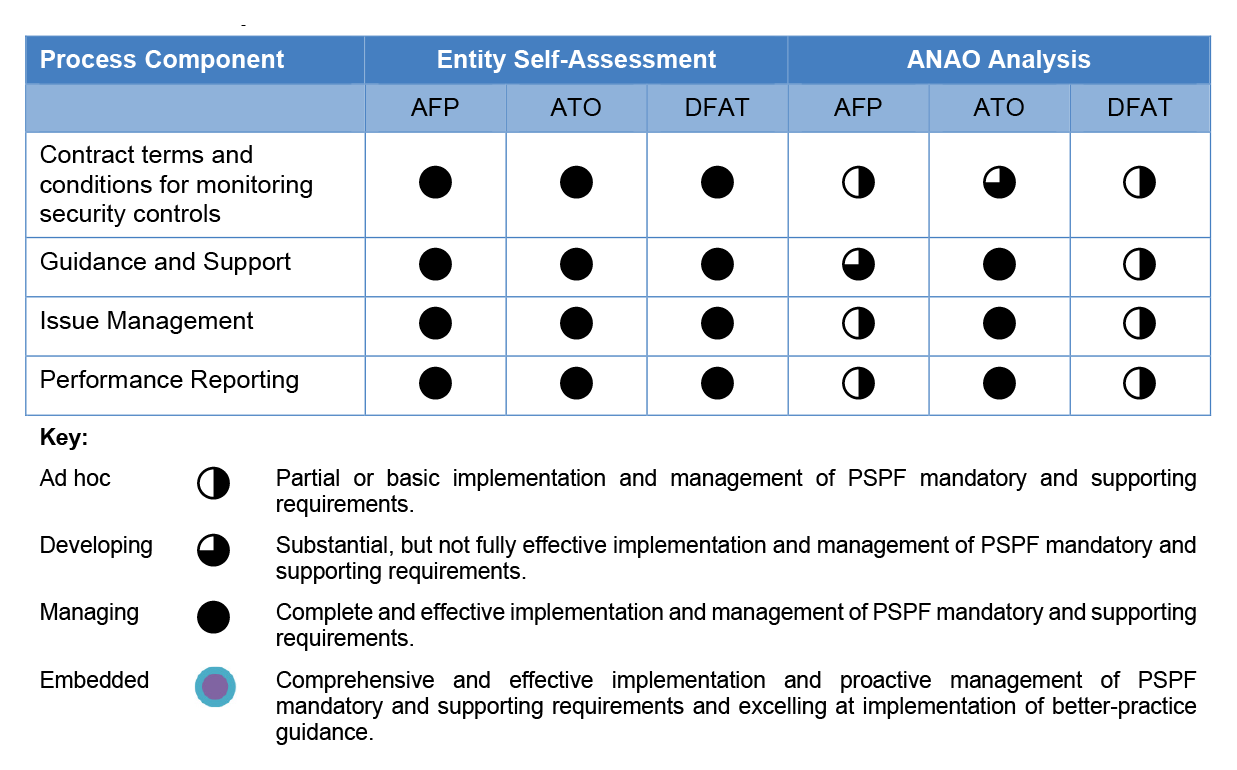

Source: Adapted from PSPF Policy 5: Reporting on security.

1.7 The PSPF specifies that the ‘Managing’ maturity level provides the minimum required level of protection of an entity’s people, information and assets.22 If an entity’s self-assessed maturity level for a PSPF policy is ‘Ad hoc’ or ‘Developing’, the entity is required to provide information in its assessment regarding the proposed strategies or implementation activities to improve the entity’s maturity level to ‘Managing’. The entity is also required to provide the associated timeframe for each strategy to achieve ‘Managing’ maturity.

1.8 AGD updated the PSPF maturity self-assessment model on the 8 October 2022 in response to recommendation 9 within the Auditor-General Report No. 32 2020–21 Cyber Security Strategies of Non-Corporate Commonwealth Entities. Recommendation 9 suggested AGD perform a review of the PSPF maturity self-assessment model to determine if the maturity levels are fit-for-purpose and effectively align with the Essential Eight Maturity Model. AGD has updated the maturity levels and descriptors to simplify the terminology used and align PSPF and Essential Eight Maturity models. Figure 1.1 depicts the high-level changes in the PSPF maturity self-assessment model.

Figure 1.1: PSPF Maturity Self-assessment Model Changes

Source: AGD October 2022 Chief Security Office Forum Newsletter, p. 1.

1.9 The ANAO assessed selected entities using the PSPF maturity self-assessment model in place at the planning of this audit in September 2021, as entities would not be reporting against changes introduced in October 2022. NCEs are required to use the new maturity levels in the PSPF 2022–23 reporting period.

Managing cyber security supply chain risk

1.10 Requirements for NCEs to manage cyber security supply chain risks are outlined in PSPF Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and service providers (Policy 6) and the CPRs. These are supported by requirements in PSPF Policy 10: Safeguarding data from cyber threats (Policy 10), which outlines the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and service providers

1.11 The core requirement of Policy 6 mandates that each NCE is accountable for the security risks arising from procuring goods and services and must ensure contracted providers comply with relevant PSPF requirements. 23 This requirement predates the October 2018 revision of the PSPF. The previous GOV-12 set out requirements for NCEs to ensure that contracted service providers comply with PSPF requirements. 24

1.12 In addition to the core requirement, Policy 6 sets out four mandatory supporting requirements, outlined in Box 1.25

|

Box 1: Protective Security Policy Framework, Policy 6 supporting requirements |

|

Requirement 1. Assessing and managing security risks of procurement When procuring goods or services, entities must put in place proportionate protective security measures by identifying and documenting: a. specific security risks to its people, information and assets; and b. mitigations for identified risks. Requirement 2. Establishing protective security terms and conditions in contracts Entities must ensure that contracts for goods and services include relevant security terms and conditions for the provider to: a. apply appropriate information, physical and personnel security requirements of the PSPF; b. manage identified security risks relevant to the procurement; and c. implement governance arrangements to manage ongoing protective security requirements, including to notify the entity of any actual or suspected security incidents and follow reasonable direction from the entity arising from incident investigations. Requirement 3. Ongoing management of protective security in contracts When managing contracts, entities must put in place the following measures over the life of a contract: a. ensure that security controls included in the contract are implemented, operated and maintained by the contracted provider and associated subcontractor; and b. manage any changes to the provision of goods or services, and reassess security risks. Requirement 4. Completion or termination of a contract Entities must implement appropriate security arrangements at completion or termination of a contract. |

Source: PSPF Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and service providers.

1.13 Policy 6 provides details to support the CPRs that govern how entities procure goods and services.26 The CPRs provide guidance on general procurement risk, but limited guidance regarding considerations of cyber security risks. In December 2020, Department of Finance updated CPR rule 8.3, to align with existing PSPF policies, specifying that relevant entities should be considering and managing procurement security risks including in relation to cyber security risks. It requires that NCEs and prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities listed in section 30 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 specifically consider the cyber security risk associated with each procurement, which is outlined in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Commonwealth Procurement Rules rule 8.3 |

|

Relevant entities should consider and manage their procurement security risk, including in relation to cyber security risk, in accordance with the Australian Government’s Protective Security Policy Framework.a |

Note a: The mandatory supporting Requirement 1 of Policy 6 requires the assessment and management of security risks of procurements.

Source: Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

1.14 The Australian Government is a large procurer of information communications technology (ICT) related goods and services, with 19,270 contracts worth approximately $14.8 billion committed in 2021–22.27 This commitment introduces dependencies on significant supply chains. In November 2019, the ACSC published Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management that suggested all organisations should consider supply chain risks, specifically in relation to cyber security risks, as cyber security risks are generally transferred through the entities within the supply chain.28

Policy 10: Safeguarding data from cyber threats

1.15 Since April 2013, the Australian Government has mandated NCEs implement four of the ACSC’s Essential Eight Maturity Model, known as the Top Four.29 This mandate was initially under InfoSec 4: Safeguarding information from cyber threats and, following updates in October 2018, is now mandated by PSPF Policy 10: Safeguarding data from cyber threats (Policy 10). The mandatory requirements under Policy 10 are outlined in Box 3. Appendix 3 describes the key changes in Policy 10 and the Essential Eight Maturity Model and the applicable Policy 10 requirements for this audit.

|

Box 3: Mandatory requirements of Protective Security Framework Policy 10 (April 2013 to 30 June 2022) |

|

Each entity must mitigate common and emerging cyber threats by: a. implementing the following mitigation strategies from the Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents:

b. considering which of the remaining mitigation strategies from the Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents you need to implement to protect your entity. |

Source: Adapted from PSPF Policy 10: Safeguarding information from cyber threats.

1.16 Since the introduction of the Essential Eight Maturity Model in June 2017, Policy 10 has provided NCEs guidance on implementing the ‘Maturity Level Three’ requirements — as set out in the Essential Eight Maturity Model — to achieve a PSPF maturity rating of ‘Managing’.30 ACSC reviews the cyber threat landscape on a regular basis and updates the Essential Eight according to the threats at the time. The ANAO assessed selected entities using the Maturity Model in place at the planning of this audit in September 2021, as entities would not be reporting against changes introduced in October 2021.31 As at September 2021, there were three maturity levels in the Essential Eight Maturity Model, as defined in Table 1.3.32

Table 1.3: Maturity levels of the Essential Eight Maturity Model (June 2017 to September 2021)

|

Maturity level |

Description |

|

Maturity Level One |

Partially aligned with the intent of the mitigation strategy. |

|

Maturity Level Two |

Mostly aligned with the intent of the mitigation strategy. |

|

Maturity Level Three |

Fully aligned with the intent of the mitigation strategy. |

Source: Adapted from the ACSC’s Essential Eight Maturity Model.

1.17 AGD consulted with ACSC to improve the interaction between the PSPF and the Essential Eight Maturity Model. This consultation has resulted in updates to Policy 10 to ensure appropriate alignment between the ACSC’s Essential Eight Maturity Model and the PSPF maturity model. In March 2022, AGD updated Policy 10 to mandate the Essential Eight strategies to mitigate cyber security incidents from 1 July 2022, and advised entities that to achieve a PSPF maturity rating of ‘Managing’, NCEs must implement Essential Eight Maturity Level Two for each mitigation strategy.33

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 The ANAO has conducted a series of audits on cyber security and identified ongoing low levels of cyber resilience in NCEs and high rates of non‐compliance with the Top Four mitigation strategies. The high-rates of non-compliance continues to be an issue as AGD’s PSPF Assessment Report 2020–21 indicated 72 per cent of NCEs reported not fully implementing Policy 10 requirements. 34 The Top Four mitigation strategies were mandated by the PSPF in 2013. Auditor‐General Report No. 32 2020–21 Cyber Security Strategies of Non‐Corporate Commonwealth Entities noted that:

The 2018‐19 PSPF assessment report identified that one of the key challenges faced by the entities who had not achieved the ‘Managing’ maturity level of Policy 10 was reliance on outsourced service providers for information communications technology (ICT) and cyber security services, whereby entities had limited influence or control over the implementation of the mitigation strategies.35

1.19 The limited influence and control over outsourced service providers of ICT and cyber security services increases the cyber security risks arising from an entity’s supply chain. The management of cyber security risks within procurements continues to be challenging for NCEs with 51 per cent being reported in AGD’s PSPF Assessment Report 2020–21 as not fully implementing Policy 6.

1.20 Auditor‐General Report No. 4 2021–22 Defence’s Contract Administration — Defence Industry Security Program and Auditor‐General Report No. 6 2021–22 Management of the Civil Maritime Surveillance Services Contract have further indicated poor administration of government procurements, including monitoring and treatment of non‐compliance with contractual requirements.36

1.21 The Australian Government has committed $14.8 billion in information communications technology (ICT) related goods and services contracts in 2021–22.37 These commitments indicate the Australian Government’s reliance on contracted providers for its ICT capabilities. This dependency on contractors for ICT capabilities and the increase in malicious cyber activities against contractors who hold government information increases the risks associated with government supply chains.38

1.22 This audit was identified as a Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) priority for 2021-22.

1.23 This audit will examine the effectiveness of the implementation of Policy 6 by selected NCEs and the effectiveness of selected contracted providers’ compliance with the relevant PSPF requirements relating to procurement cyber security risks. It will provide Parliament transparency and insights on the management of procurement cyber security risks.39

Audit approach

1.24 The following three NCEs were selected for this audit:

- Australian Federal Police (AFP);

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO); and

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

1.25 The 2020–21 Policy 6 and Policy 10 maturity ratings, as self-assessed by the selected entities, are outlined in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Selected entities and their 2020-21 Policy 6 and 10 self-assessed maturity ratings

Source: Reported 2020–21 Policy 6 and 10 maturity ratings for selected entities.

1.26 Contracts were selected for each entity to support the assessment against Policy 6 requirements. The contracts selected were based on contract value, and the type of goods and services being provided, with a focus on goods and services relating to handling of sensitive information, security functions and management of privileged user access. These functions were suggested as higher priority by the ACSC.40

1.27 The contracts selected were with DXC Technology (DXC), Hitachi Vantara (Hitachi), and Telstra Australia (Telstra). A summary of contract details has been provided in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5: Summary of contract details

|

Entity |

Contracted Provider |

Value ($) milliona |

Contract Initiation |

Scope of Services |

|

Australian Federal Police |

Hitachi Vantara Australia Pty Limited trading as Hitachi Data Systems Pty Ltd (Hitachi) |

24 |

September 2017 |

Provision of ICT facilities and ongoing system management services. These are to be provided in AFP’s ICT environment. |

|

Australia Taxation Office |

DXC Enterprise Australia Pty Ltd (DXC) |

2,161 |

December 2010 |

Provision of ICT infrastructure services, facilities, solutions, system/environment management. These are to be provided in ATO’s ICT environment. |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

Telstra Corporation Limited (Telstra) |

281 |

June 2016 |

Provision of communication services and facilities. These are to be provided outside of DFAT’s ICT environment. |

Note a: As at October 2022.

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data.

1.28 Hitachi provides infrastructure management services for two data centres that support AFP’s ICT environment. Hitachi manages services which consolidates and virtualises physical compute, network and storage resources capabilities for AFP. Support and maintenance services provided include change and incident management services. AFP manages Hitachi staff as part of its AFP work force and requires Hitachi staff to comply to with all AFP policies and procedures.

1.29 DXC provides centralised computing solutions to ATO. The centralised computing supports ATO’s ICT infrastructure and various systems and applications. DXC’s service encompasses virtual and non-virtual server management, midrange, data warehouse and storage services. DXC teams perform their function within ATO’s ICT infrastructure and are integrated into ATO’s teams. DXC teams are required to adhere to ATO policies and procedures.

1.30 DFAT’s ICT network relies on international telecommunication network services provided by Telstra that connect sites in Australia and overseas posts. Telstra provides satellite, VPN and internet services to facilitate site-to-site network connectivity. Under DFAT’s instruction, Telstra supplies and maintains equipment and facilities required for network connectivity.

1.31 The ANAO assessed the selected contracted providers’ implementation of cyber security requirements within the respective contracts. As discussed in paragraph 1.11, Policy 6 requires contract providers to comply with relevant PSPF requirements. This includes requiring contracted providers to protect Australian Government information resources in the same manner as the procuring entity. Where the contracts do not detail the relevant PSPF requirements then the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements and Essential Eight Maturity Model as of September 2021, Top Four, will form the basis for the assessment.41 The scope of cyber security related services provided under each contract is specified in Table 1.6.

Table 1.6: Summary of applicable cyber security related services

|

Contracted Provider |

Application Control |

Patching Applications |

Patching Operating Systems |

Restricting administrative privileges |

|

Hitachi |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

DXC |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

|

Telstra |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

Source: ANAO analysis of contracts and entity business processes

1.32 The ANAO examined the implementation and performance of the respective cyber security related services specific to each contract and on the applications and systems relevant to the contracts. The ANAO tested the operating effectiveness of controls between 1 January 2021 and 1 June 2022.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.33 The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of selected NCEs’ arrangements for managing cyber security risks, within their procurements and specific contracted providers, under the PSPF.

1.34 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following two high-level criteria:

- Have entities established effective arrangements to assess and manage procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the PSPF requirements?

- Have the contracted providers complied with the relevant PSPF requirements?

1.35 The audit examined the effectiveness of the implementation of:

- Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and services providers by selected NCEs; and

- Policy 10: Safeguarding data from cyber threats by the selected contracted providers.

Audit methodology

1.36 The audit methodology included:

- examination of NCEs’ documentation for managing procurements related to the selected contracted providers against Policies 6 and 10;

- system testing and technical assessment of the cyber security controls implemented by the contracted providers against the requirements in Policy 10;

- examination of the contracted providers’ cyber security reporting and documentation; and

- meetings with the NCEs’ and contracted providers’ staff.

1.37 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $609,561.

1.38 The team members for this audit were Edwin Apoderado, Benjamin Siddans, Zhiying Wen, Ji-Young Kim, Jason Ralston, David Willis, Stevan Serafimov, Olivia Robbins, Jo Rattray-Wood, Sherry Wang, Xiaoyan Lu, and Lesa Craswell.

2. Managing cyber security risks in procurements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the selected entities have established effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) requirements.

Conclusion

Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has largely effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks in accordance with the PSPF. Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) have partially effective arrangements for assessing and managing procurement risks related to cyber security in accordance with the PSPF.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made the following recommendations aimed at:

- all three entities improving processes and guidance for assessing and managing cyber security risks within procurements, including documenting the consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements and identifying when procurement teams should consult cyber security specialists; and

- all three entities implementing processes for verifying the reliability of performance information and managing non-compliance with relevant mandatory PSPF security requirements, including establishing relevant performance measures.

2.1 The Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires entities to demonstrate how public resources have been applied to achieve their purposes. The Attorney-General’s Directive on the Security of Government Business establishes the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) as an Australian Government policy.42 The PSPF Policy 6: Security governance for contracted goods and service providers (Policy 6) requires entities to manage cyber security risks arising from procuring goods and services and ensure that contracted providers comply with relevant PSPF cyber security requirements.

2.2 This chapter examines whether audited entities have established sound risk management and contracting frameworks for managing procurement cyber security risks. Policy 6 requires (see Box 1) these frameworks to include processes for identifying and documenting risks, establishing contract terms and conditions, and oversight of contracted provider performance.

Have entities established an appropriate risk management framework for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks?

All three entities have defined roles and responsibilities for managing procurement cyber security risks. The procurement teams are responsible for identifying, assessing, and managing cyber security risks within procurements. The entities have cyber security specialists who can provide advice on cyber security risks associated with a procurement.

None of the three entities’ processes required procurement teams to consult with cyber security specialists when assessing procurement cyber security risks or when considering mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Of the three entities, ATO has processes for assisting procurement teams with assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks and consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. AFP and DFAT has not implemented processes for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks, including documenting any assessments performed relating to mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

2.3 When the provision of digital services is outsourced to external providers, accountability for the good or service and associated delivery outcomes (including managing security risks) remains with the entity. Policy 6 provides guidance on assessing and managing the cyber security risks in procurements. It outlines the mandatory requirements (see Box 1) for identifying, documenting and mitigating cyber security risks.

2.4 Establishing an appropriate risk management framework helps entities understand cyber security risks associated with a procurement and assists with identifying suitable security treatments.

2.5 The ANAO reviewed entities’ processes and procedures to assess whether the Policy 6 requirements had been clearly defined and addressed. Policy 6 requires risk management processes to:

- define the roles and responsibilities for assessing and managing procurement cyber security risks; and

- identify and document mitigations for procurement cyber security risks, including consultation with IT security experts and specifying mandatory security requirements.

2.6 The results of the review for each audited entity are summarised in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Entities’ risk management framework implementation levelsa

Note a: The ‘Entity Self-Assessment’ rating is the entity reported PSPF maturity level for the entities’ overall environment. The ‘ANAO analysis’ assessment maturity level rating only relates to processes for managing cyber security risk.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Roles and responsibilities defined

2.7 All three entities had defined roles and responsibilities for managing procurement cyber security risks. The team responsible for the procurement is responsible for identifying, assessing and mitigating cyber security risks associated with the procurement. The procurement team is also responsible for engaging the entities’ cyber security specialists.

2.8 Each entity has cyber security specialists that are responsible for the assessment, implementation, and delivery of cyber security outcomes across the enterprise. The cyber security specialists are required to provide support when engaged by procurement teams on procurement cyber security risks.

2.9 All entities have a centralised procurement function that is responsible for managing procurement policies, procedures and guidance. The centralised procurement function is also responsible for reporting on the progress of procurements and ensuring procurement teams adhere to procurement processes.

Identification, assessment and mitigation of procurement cyber security risks

2.10 AFP and DFAT’s guidelines and processes do not provide details for identifying, assessing, and managing procurement cyber security risks, including documenting any risk assessments performed in relation to mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. ATO has guidelines and processes for assessing cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements within its procurements.

2.11 AFP’s Third Party Risk Management Guideline requires that procurement teams complete a risk assessment at the planning stage of any new procurement. The guideline was developed to provide guidance on identifying and managing procurement risks, with specific focus on understanding risks in information communications technology (ICT) procurements. The guideline does not provide details on how cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements are considered as part of risk assessments. AFP has advised the ANAO that cyber security risks are assessed as part of considerations of AFP’s general security environment. The guideline was approved in October 2021 and AFP adopted a staged approach to its implementation. As of June 2022, the guideline had not been implemented and AFP did not have a documented implementation plan.

2.12 ATO has procurement and contract management frameworks that set out the principles for managing vendors, roles and responsibilities, the relationship management approach, and assurance and reporting requirements. ATO uses questionnaires to assist procurement teams to assess the procurement security risks. These questionnaires address all PSPF requirements, including those relating to cyber security. The questionnaires are completed by the procurement team and provided to ATO’s cyber security specialists if further advice is required. ATO’s cyber security specialists provide advice on cyber security risks and considerations relating to the procurement. Procurement teams are not required to consult with ATO’s cyber security specialists on all procurements, including ICT-related procurements. No questionnaire was completed in relation to the DXC contract.

2.13 DFAT’s 2021 Security Risk Management Policy consists of tools and templates for assessing the operational impact of security risks. Those tools and templates do not include details on how cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements are considered within procurements. The policy does not specify processes for identifying, assessing, and managing procurement cyber security risks.

2.14 DFAT developed the Cyber Security Supply Chain Policy (Supply Chain Policy) in June 2021 to support the 2021 Security Risk Management Policy. The Supply Chain Policy provides details for identifying, assessing, and managing procurement cyber security risks. The Supply Chain Policy requires DFAT’s cyber security specialists to perform a preliminary cyber security assessment to understand the supply chain risks from a contracted provider. These assessments and the decisions for not performing assessments are not required to be documented under the Supply Chain Policy. DFAT has recently developed a Procurement Policy in June 2022 that specifies the roles and responsibilities for documenting these assessments. This policy only applies to new procurements and not contract variations nor extensions and has not been applied to the Telstra contract.

Recommendation no.1

2.15 To improve the quality of risk assessments:

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve processes and guidance for assessing and managing cyber security risks within procurements, including documenting the consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements; and

- Australian Federal Police, Australian Taxation Office and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade implement processes to assist with identifying when procurement teams are required to consult with cyber security specialists on cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed, agreed in part.

2.16 The AFP agrees to improve the quality of risk assessments in support of complex procurements including determining when procurement teams should escalate risks for further consideration.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.17 The ATO will ensure guidance material includes directions for engaging cyber security specialists, to improve the quality of risk assessments. This will help inform cyber security risks and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements in procurements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

2.18 The department agrees to the recommendation and has already taken steps in line with this recommendation to improve processes. This includes the implementation of the new enterprise Procurement Policy in early 2022 which embeds the consideration of cyber security risks during procurements, in accordance with PSPF policies 6 and 10, as well as the introduction of the revised Cyber Security Supply Chain Policy in 2021. Additional policy and process improvements will be implemented to further address this recommendation.

Have entities established fit-for-purpose contracting arrangements that support the management of procurement cyber security risks?

All three entities have contract clauses requiring contracted providers to comply with the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), ACSC’s Information Security Manual (ISM) and the respective entities’ policies. ATO performs ongoing assessments of its security terms and conditions to ensure protective security requirements address identified cyber security risks.

DFAT and AFP use contract management plans to specify roles and responsibilities for each contract. ATO has a generic contract management plan that covers ICT contracts and is developing detailed plans for each contracted provider. ATO’s generic contract management plan does not detail roles and responsibilities for each ICT contract.

All three entities have incident management processes within contracting arrangements.

ATO is the only entity that has arrangements for monitoring performance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. However, the ATO has not detailed how non-compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements is to be managed.

2.19 A contract is a legally enforceable document between two or more parties. The contract specifies each party’s rights and obligations in performance of that contract. It is important that contracts are effectively managed to achieve security outcomes. Ineffective contracting arrangements can lead to increased risks to people, information, and assets. The specification of relevant security terms and conditions supports the effective management of security outcomes and ensures that security requirements are legally enforceable.

2.20 The ANAO reviewed entities’ processes and procedures to assess whether the Policy 6 requirements had been clearly defined and addressed. Policy 6 requires contracted providers to protect Australian Government information resources in the same manner as the procuring entity. This can be achieved by implementing contracting arrangements that:

- include cyber security terms and conditions as part of procurement and contract management documents;

- have defined the roles and responsibilities for managing cyber security requirements within contracts;

- have appropriate procedures to assess and manage cyber security incidents arising from the selected contracted providers; and

- have appropriate procedures for managing performance against the contract requirements relating to PSPF requirements.

2.21 The results of the review for each audited entity are summarised in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Entities’ contract management implementation levelsa

Note a: The ‘Entity Self-Assessment’ rating is the entity reported PSPF maturity level for the entities’ overall environment. The ‘ANAO analysis’ assessment maturity level rating only relates to processes for managing cyber security risk.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Cyber security terms and conditions

2.22 All three entities have procurement and contract management guidance to assist with developing contract terms and conditions. The guidance has contract templates with suggested broad contract terms and conditions specifying goods and services to be provided in accordance with the PSPF, Australian Signals Directorate’s Information Security Manual (ISM) and entity internal policy requirements. Of the three entities, ATO had detailed the assessment of cyber security risks and consideration of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements in its guidance to assist with establishing cyber security terms and conditions.

2.23 The ANAO reviewed selected contracts from each entity and noted that all entities had included broad contract terms and conditions requiring compliance with the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements. The entities’ security policies and procedures formed part of the contract suite of documents and included requirements relating to mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements (see Box 3).

2.24 Of the three entities, ATO had specified contract terms and conditions for some of the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements within detailed schedules and service level agreements. These contract terms and conditions aligned to services outlined in Table 1.6. The ATO contract suite included the following terms and conditions related to protections against cyber security threats:

- timeframes for implementing patches and updates;

- reporting on status of patches;

- management and monitoring against malicious software (malware) and viruses43;

- system security accreditation requirements; and

- compliance reporting against ATO’s security requirements.

2.25 In addition to including cyber security terms and conditions within procurement and contract management guidance, Policy 6 requires entities to perform ongoing assessments of contract conditions to ensure protective security requirements address identified cyber security risks. These assessments include monitoring and reviewing risks when changes are required to the provision of goods and services.

2.26 All three entities require risks to be documented within a risk management plan prior to agreement of the contract, including when a risk review is required before issuing any contract variation. The ANAO reviewed the selected contracts and associated variations relating to cyber security. None of the entities had risk management plans, nor evidence of their risk assessments and considerations of mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements prior to issuing of contract variations.

2.27 AFP and DFAT have not reviewed nor updated their selected contracts in relation to changes in the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Contract variations that occurred between 2018 and 2022 did not consider the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.44 ATO made several variations against its selected contract which related to changes in the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

2.28 DXC maintains a risk register, which it is required to report to the ATO, to support regular monitoring of risks and associated controls. The risk register specifies the risks and controls that need to be managed by the contracted provider as part of the contract. Although the selected contract required the contracted provider to comply with all PSPF and ISM controls, the risk registers only specified some mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. ATO did not document its consideration of all mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements during the risk assessment process.

Roles and responsibilities

2.29 Appropriate management structures assist entities to manage security risks, especially to ensure security decisions are made in accordance with required security practices. All three entities have established governance structures to manage the service operations for their IT systems and environment, including managing ICT procurements, contracts and service providers. The audited entities had separate teams that were responsible for managing ICT contracts and cyber security issues. ICT contract management teams were responsible for developing contract management plans and procedures for the management of all IT contracts. The plans and procedures specify the process and tools for contract administration. ICT contract management teams were responsible for seeking advice from the entities’ cyber security specialists. The cyber security specialists provide advice when required by ICT contract management teams.

2.30 None of the entities’ procurement and contract management processes required procurement and contract management teams to consult with cyber security specialists during procurement and contract development processes. Further, where the cyber security specialists were not engaged, the decision and reasons for not engaging the cyber security specialists were not recorded.

2.31 The ANAO reviewed the contract management processes supporting the selected contracts. AFP and DFAT have contract management plans specific to the selected contracts, which outlined roles and responsibilities for both the entity and contracted provider. ATO applies a generic contract management plan to all ICT contracts and contracted providers.

2.32 ATO’s generic contract management plan describes contract management processes and requirements that are applicable across multiple service providers. Given the generic nature of the plan, it only specified the critical contract management roles for managing a contract and did not specify who in the ATO or contracted provider is responsible for managing risks relating to a specific contract.

2.33 A February 2021 ATO internal audit report on vendor management identified similar concerns with contract management plans not specifying details on how contracts will be managed over the contract period. ATO advised the ANAO that a specific DXC contract management plan is still being drafted as of June 2022.

Incident management

2.34 Oversight of incidents through timely and thorough reporting allows entities to adjust security practices and contract conditions to mitigate cyber security risks. It is important that entities include such contract terms and conditions to ensure that service providers notify entities of actual or suspected cyber security incidents, especially if the incident affects the delivery of goods or services stated in the contracts.

2.35 All three entities have a process for managing a range of security incidents, which is supported by procedures for handling most common cyber security risks and issues. Contracted providers are required to report incidents using entity specific security incident management processes, including contacting the relevant security teams for assistance with assessing suspected or actual incidents.

2.36 All three entities hold monthly contracted provider discussions. Contracted providers are required to report on security incidents as part of monthly reporting requirements. This reporting includes details of the incidents, such as the priority and impact, affected systems and users, and whether service level agreements were met.

2.37 A review of the selected contracts identified terms and conditions for reporting security incidents, including roles and responsibilities, timeframes, reporting requirements, and the provision of data, such as security event logs. The ANAO noted that the monthly reporting was focussed on operational and service delivery risks, rather than security risks.

Performance management

2.38 Contract arrangements that include ongoing assessments of compliance with contract security conditions will help ensure that vendors are adhering to essential security requirements within contracts. This ongoing oversight and management is important given the constantly changing security risks and environment.

2.39 All three entities have regular contracted provider meetings that discuss performance against contract terms and conditions, including key performance indicators and measures. AFP and DFAT selected contracts specified requirements for contracted providers to comply with PSPF and entity internal policy requirements. AFP and DFAT do not monitor performance against the PSPF and entity internal policy requirements, including mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Consequently, Hitachi and Telstra do not report on their implementation and performance against PSPF, entity internal policy requirements and mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements.

2.40 ATO specified contract terms and conditions relating to the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements, and monitored performance through the following mechanisms:

- monthly contracted provider meetings, included a review of cyber security risks and some of the controls relating to mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements;

- an annual independent Infosec Registered Assessors Program (IRAP) assessment for the systems it supports within the contract45; and

- ATO Cyber Governance and Operations (CGO) quarterly assurance audits assess and require input from contracted providers on implementation and performance against the Essential Eight mitigation strategies.

2.41 Although the ATO has mechanisms in place, it has not detailed how non-compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements is to be managed.

Have entities established fit-for-purpose arrangements for the management of contracted providers’ compliance with relevant Protective Security Policy Framework requirements?

All selected contracts required contracted providers to adhere to the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements. None of the entities had processes, performance measures and service level agreements related to managing non-compliance with PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements. Further, none of the entities had processes for verifying the reliability of cyber security related performance information provided by contracted providers.

AFP and DFAT do not monitor compliance against PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements for the selected contracts. ATO has established a Cyber Threat Assurance Program and risk management processes for assessing compliance against mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. The assurance program included a quarterly audit of contracted provider implementation of the Top Four mitigation strategies. The risk management processes included the use of risk registers to monitor the implementation of some mandatory PSPF cyber security controls and ATO policy requirements.

2.42 Security environments and risks constantly change, and sound contract management arrangements can help ensure adherence to security requirements within contracts. Contract management arrangements that include continuous evaluation of compliance against contract requirements can provide a flexible approach to managing contracts. It allows protective measures to be adjusted based on changes in the environment and risks. Policy 6 requires accountable authorities to continuously evaluate compliance against contract conditions and terminate contracts if the contracted provider fails to comply with contract provisions.

2.43 The ANAO reviewed entity procedures and processes to assess whether the Policy 6 requirements had been clearly defined and addressed. Policy 6 requires contracting arrangements to:

- establish performance measures and service level agreements to assess contractor performance; and

- have appropriate procedures for managing compliance against the contract requirements.

2.44 The results of the review for each audited entity are summarised in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Entities’ management of contracted provider compliance with relevant PSPF requirementsa

Note a: The ‘Entity Self-Assessment’ rating is the entity reported PSPF maturity level for the entities’ overall environment. The ‘ANAO analysis’ assessment maturity level rating only relates to processes for managing cyber security risk.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Service level agreements

2.45 The specification of important security considerations should be documented in the contract and service level agreements. This ensures that the security considerations are verifiable and enforceable.46

2.46 As described in paragraph 2.23, all three entities specify security requirements as broad contract obligations, such as requiring contracted providers to adhere to the PSPF, ISM and entities’ internal policies. None of the selected contracts had service level agreements (SLAs) and key performance indicators (KPIs) relating to measuring adherence to the mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. The SLAs and KPIs were focussed on the management of services, such as maintenance activities and availability of systems. There was limited performance information on adherence to PSPF, ISM and entities’ internal policy requirements.

Compliance and assurance activities

2.47 While entities had general processes for monitoring contracted provider compliance with contract requirements, neither AFP nor DFAT monitor contracted provider compliance against the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policies, and could not verify contracted provider adherence with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. ATO’s contracted provider risk registers included details on cyber security risks, including PSPF, ISM and ATO’s security controls. Not all mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements were included in the risk registers.47

2.48 In addition to contracted provider risk registers, ATO monitors contracted provider compliance with PSPF requirements through its Cyber Threat Assurance Program (CTAP). The CTAP was initiated in 2016 and aims to provide assurance over controls relating to the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre’s (ACSC’s) Top Four mitigation strategies, including monitoring remediation actions to be performed by contracted providers.

2.49 In October 2021, ATO undertook an internal audit of the assurance arrangements for assessing, managing, and reporting on maturity and compliance levels of Essential Eight controls. The internal audit reviewed the CTAP and recommended improvements to the CTAP methodology, specifically considering alignment with ACSC’s Essential Eight Maturity Model and changes in ATO’s environment and confirming the completeness and accuracy of contracted provider data. ATO had agreed to implement improvements to the CTAP methodology by 30 June 2022 but had not completed its implementation.

2.50 None of the selected contracts detail how performance is measured against contract terms and conditions in relation to adhering to PSPF, ISM and entities’ internal security requirements. AFP and DFAT do not have processes for confirming contracted provider compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements. Although ATO has the CTAP and risk registers for assessing compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements, the arrangements do not provide detailed instructions on how contracted provider non-compliance is managed.

2.51 None of the audited entities have processes for verifying the completeness and accuracy of performance information provided by contracted providers. All three entities rely on discussions with contracted providers to confirm their understanding and robustness of performance information. Entities do not have set processes to ensure information is complete and accurate, such as verification against independent information sources or application of contracted providers’ quality assurance processes.

2.52 AFP and DFAT have not assessed contracted provider compliance with relevant PSPF requirements since the initiation of those contracts. Without appropriate contract terms and conditions, and processes for verifying performance information, compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements cannot be accurately assessed and enforced.

Recommendation no.2

2.53 Australian Federal Police, Australian Taxation Office and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade should implement processes for verifying the reliability of performance information and managing non-compliance by contracted providers against the PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements, including establishing performance measures focussed on compliance against PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

2.54 The AFP agrees to improve internal information security policy pertaining to the oversight of vendors.

2.55 The AFP agrees to improve monitoring of security controls via the inclusion of relevant performance measures surrounding vendor security obligations and that relevant reporting mechanisms are specified.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.56 The ATO will ensure reliability of performance information is verified and performance measures focus on compliance against PSPF, ISM and entity internal policy requirements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

2.57 DFAT agrees to the recommendation and will establish a framework that supports the review and management of contracted ICT provider performance and non-compliance.

3. Compliance with Protective Security Policy Framework requirements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the selected entities have established effective arrangements to manage compliance of their contracted providers with the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) requirements for cyber security.

Conclusion

Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) do not manage compliance of contracted providers with the PSPF requirements for cyber security.

Australian Taxation Office (ATO) had largely established arrangements to manage compliance of their contracted providers with limited assurance over reporting and methods of enforcement of the PSPF requirements for cyber security.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made the following recommendations aimed at:

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade specifying requirements for the implementation and monitoring of the mandatory Protective Security Policy Framework cyber security requirements in contractual arrangements;

- Australian Federal Police and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establishing periodic assessments of security terms and conditions of their contracts to address associated cyber security risks;