Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Commonwealth National Parks

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Director of National Parks’ management of Australia’s six Commonwealth national parks.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Director of National Parks (the Director) is appointed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) to conserve and manage biodiversity and cultural heritage within Commonwealth parks and reserves. Parks Australia, a division of the Department of the Environment and Energy, assists the Director to fulfil these functions.

2. There are six terrestrial Commonwealth national parks under the EPBC Act:

- Booderee, Kakadu and Uluru-Kata Tjuta national parks, which are jointly managed by the Director and traditional owners; and

- island national parks in the territories of Norfolk, Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

3. Core management activities undertaken across these parks include invasive species control, threatened species monitoring, asset maintenance, visitor and park use management, and community and stakeholder engagement. As required by the EPBC Act, activities are to be undertaken in accordance with 10-year statutory park management plans. The Director also maintains operational plans for each park.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Terrestrial Commonwealth national parks cover over 2.1 million hectares and have been established to conserve natural and cultural heritage that is of national and international significance. The government holds over $200 million in assets and invests approximately $50 million per year to manage these parks in line with international commitments for biodiversity protection as well as commitments to traditional owners. This funding is designed to contribute not only to environmental conservation, but also the tourism industry and the economic development of Aboriginal communities associated with the parks.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Director’s management of the six terrestrial Commonwealth national parks. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Are appropriate governance arrangements in place to support strategic risk management and business and operational planning?

- Are national park business management and operational plans effectively implemented?

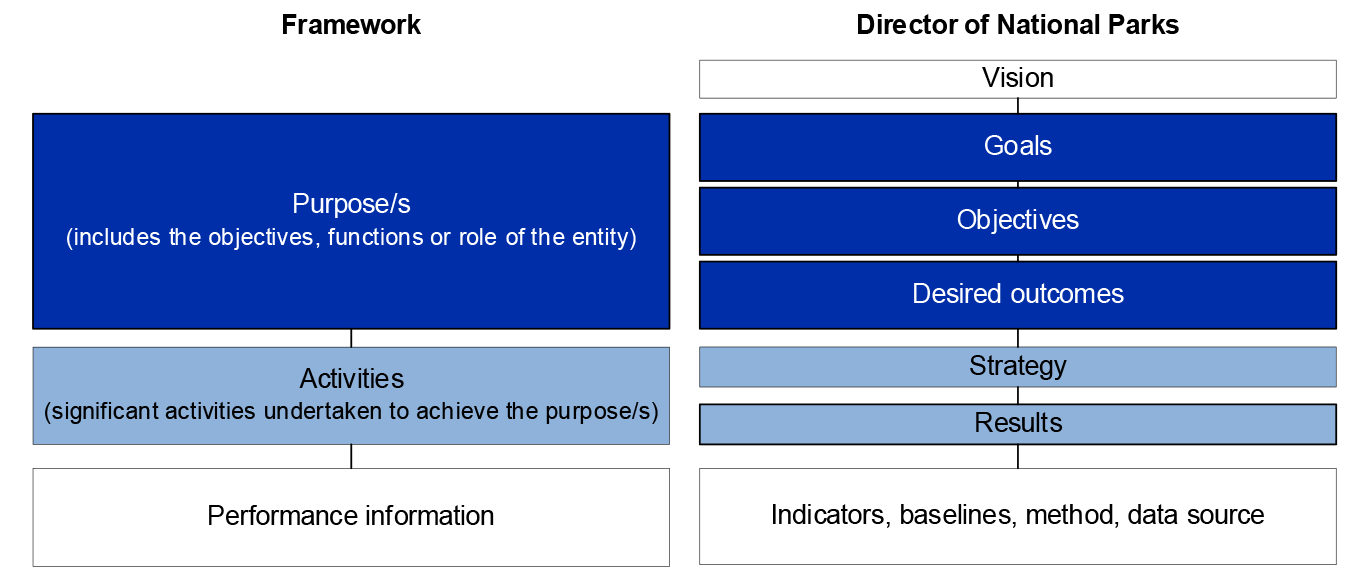

- Does the Director effectively measure, monitor and report on park operational activities?

Conclusion

6. The Director of National Parks has not established effective arrangements to plan, deliver and measure the impact of its operational activities within the six terrestrial national parks. As a result, it is unable to adequately inform itself, joint managers and other stakeholders of the extent to which it is meeting its management objectives.

7. Governance arrangements to support the Director’s management of national parks do not adequately support the delivery of corporate services, risk management, planning and engagement with traditional owners to the benefit of park management objectives.

8. The Director has not established robust arrangements to ensure that corporate, park management and operational plans are being implemented.

9. Park activities are not effectively measured, monitored and reported on. The Director’s performance measures are not complete, and lack rigour, clear targets, baselines and descriptions of measurement methods.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

10. The Director and the Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Energy have not established appropriate administrative arrangements to support park management. The arrangements between the two accountable authorities were set out in a 2001 memorandum of understanding and a 2013 service delivery agreement. Neither document fully reflects current practice, giving rise to duplication in corporate support and reduced effectiveness and efficiency in park management. The current review of administrative arrangements should be expedited to address these issues.

11. The Director does not effectively manage risks to the objectives of the parks. The Director’s risk management framework lacks engagement with boards of management on risk oversight. The implementation of the framework has been undermined by a lack of suitable system support to record risks and monitor the implementation of treatment measures. There is also scope for the Director to strengthen its management of climate, probity and compliance risks.

12. The planning framework established by the Director does not support the development of well aligned plans. Annual operational plans do not clearly indicate how they contribute over time to the objectives of the park management plans. Operational plans are not informed by input from boards of management in jointly managed parks.

13. While meeting statutory engagement requirements, feedback to the ANAO on the effectiveness of the Director’s engagement with stakeholders has been mixed. In particular, there is criticism that the Director has not effectively engaged the boards of management to establish constructive relationships with traditional owners at the jointly managed national parks.

Implementation of plans

14. The arrangements to monitor the implementation of actions as set in corporate, park management and operational plans are not robust. There is scope for the Director to improve the induction and professional development it provides to boards of management to support their oversight role.

15. The Director’s operational activities are not underpinned by relevant and complete procedural guidance. The lack of appropriate guidance in key areas of corporate support and operational delivery, including asset management and compliance activities, limits the extent to which these activities are delivered appropriately and consistently across the national parks.

16. Arrangements to manage staff capability require strengthening. Annual and strategic workforce plans are not monitored. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment pathways are yet to be established. Arrangements to ensure that staff have completed required training and performance agreements need to be developed.

Performance measurement, monitoring and reporting

17. The Director has not established an effective performance measurement framework. Performance measures do not fully identify beneficiaries or the impacts of activities. Targets, baselines and descriptions of measurement methods and data sources are not clearly stated. As a consequence, the Director and stakeholders have limited visibility on whether individual parks and park management overall are meeting established objectives.

18. Key decisions of the Director’s Executive Board and boards of management are generally supported by evidence. There is scope for the Director to improve its communication with boards of management.

19. The Director monitors and evaluates its performance but has not incorporated lessons learnt into its ongoing operations.

20. Reporting arrangements are not appropriate and transparent. Public reporting is limited to high level performance measures across all national parks and does not provide transparency on the impact of management activities in each park.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.28

The Director of National Parks:

- review its risk management framework to ensure that it is appropriately engaging with boards of management in its management of risk; and

- implement suitable system support to identify and document its strategic and operational risks, and to monitor the implementation of treatment measures across strategic and operational risks.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.47

The Director of National Parks review its planning framework to ensure that it is: meeting the requirements of the EPBC Act; efficiently meeting the objectives and goals of the Director; and effectively discharging the responsibilities of all parties involved in the management of the national parks. This should, where relevant, be:

- supported by implementation schedules and aligned with other relevant plans;

- informed by input from relevant stakeholders; and

- endorsed by an appropriate oversight body.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.15

The Director of National Parks strengthen its arrangements to monitor the implementation of the corporate, park management and operational plans.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.30

The Director of National Parks establish a systematic approach to:

- maintaining its procedural guidance, including arrangements to ensure that guidance is relevant and complete; and

- assure itself that its procedural guidance is implemented consistently across all locations.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 3.38

The Director of National Parks improves its governance of projects, including the maintenance of robust project monitoring arrangements. Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 4.26

The Director of National Parks improve the relevance, reliability and completeness of performance measures presented in its corporate plan by:

- ensuring performance measures identify beneficiaries and signal the impacts of activities;

- specifying targets and baselines, data sources and rigorous methodologies against each performance criterion; and

- monitoring and reporting on its performance for all significant aspects of its purposes, including conservation of cultural heritage values.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.7

Paragraph 4.55

For improved transparency of the Director’s impact in managing the national parks, the Director of National Parks should publish the technical audits of management plans.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the audited entities. Summary responses from the Director of National Parks and the Department of the Environment and Energy are provided below. The full responses are reproduced at Appendix 1.

The Director of National Parks

The Director of National Parks (the Director) agrees with all recommendations in the report.

The Director is the Commonwealth corporate entity responsible for six terrestrial national parks and 59 marine protected areas. The six terrestrial national parks that were the subject of this audit include some of Australia’s most recognisable and iconic national parks. Each displays its own unique set of historical, cultural, and ecological characteristics, along with wide-ranging social, economic and jurisdictional influences. Vast distances separate the parks from each other, with three parks operating in Australia’s external territories, and three occurring within territory jurisdictions. Against this backdrop, the Director would like to particularly acknowledge the efforts of the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in visiting several of these parks and meeting with a number of Traditional Owners and other local stakeholders as part of their review.

The Director is committed to continuous improvement in the delivery against legislative and related objectives for Commonwealth national park management. This includes the areas for improvement identified in this audit. This commitment is demonstrated by progress on a range of corporate governance and business improvement projects with many to be completed in the next six to twelve months.

Working in partnership with Traditional Owners, improving the governance and performance of the joint boards of management for Kakadu, Booderee and Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa national parks will be a particular and ongoing focus.

The Department of the Environment and Energy

Pursuant to section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997, this letter is the Department’s response. We note the suggestion that the review of administrative arrangements between the Department and the Director of National Parks be completed as soon as possible. The Operations and Corporate Change project, which was initiated in 2018, is both analysing and implementing changes. The project has already resulted in Parks Australia’s corporate functions reporting through to the relevant Department SES officers, with the Department delivering those services to the Director under a new model. These arrangements will support the Director to focus on the operation of the national parks and to continue to meet his obligations as an Accountable Authority under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The project will be completed by 30 August 2019.

In relation to the oversight from the Portfolio Audit Committee, I understand an assessment of its performance is scheduled for the 2019-20 Financial Year. The matters raised in this audit report would be taken into account in that assessment. We will consult with your officers as part of that review.

I note the Director of National Parks, as the relevant appointment under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, will be responding separately to the findings and recommendations in the report as directed to that position.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 National parks are protected areas that serve as a primary strategy for biodiversity conservation and cultural heritage preservation. In Australia, national parks form part of the National Reserve System, which comprises areas of land under government, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, private or joint management that are formally protected under Commonwealth, state or territory legislation.1 The National Reserve System contributes to Australia’s international commitments, including those under the International Convention on Biological Diversity. Areas in the National Reserve System are defined and categorised by international guidelines.2

1.2 The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) is the principal legislation for establishing and managing Commonwealth protected areas. The EPBC Act provides for the protection and management of the natural and cultural features of declared parks and reserves. The Director of National Parks (the Director) is a corporation sole established under division 5, part 19 of the EPBC Act.3 The Director’s functions include ‘to administer, manage and control Commonwealth reserves and conservation zones’ and ‘to protect, conserve and manage biodiversity and heritage in Commonwealth reserves and conservation zones’.

1.3 The Director is assisted by Parks Australia, a division of the Department of the Environment and Energy (the department), under a memorandum of understanding established between the Director and the Secretary of the department in 2001. Under this arrangement, the Director relies on resources provided by the Secretary and reports directly to the Minister on matters relating to its responsibilities. In the departmental administrative structure, the Director appears alongside First Assistant Secretaries (senior executive service band two).

Commonwealth national parks and reserves

1.4 As at June 2019, there were six terrestrial reserves named as national parks, 59 marine reserves and the national botanic gardens declared as Commonwealth reserves under the EPBC Act. The six national parks cover over 2.1 million hectares and include: three mainland parks that are jointly managed with traditional owners; and three island parks located within Australian external territories. Key features of these six Commonwealth national parks are outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Key natural and cultural values of the six Commonwealth national parks

|

Jointly managed nationals parks |

|

|

Uluru-Kata Tjuta (132,566 hectares)

|

|

|

Kakadu (1,980,955 hectares)

|

|

|

Booderee (6,379 hectares)

|

|

|

Island national parks |

|

|

Christmas Island (8,719 hectares)

|

|

|

Norfolk Island (656 hectares)

|

|

|

Pulu Keeling (2,602 hectares)

|

|

Note a: The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands.

Source: ANAO summary of Director of National Parks information.

Park planning and management

1.5 According to the Environment and Energy Portfolio Budget Statements 2019–20 and Director of National Parks Corporate Plan 2018–2022, the Director’s key outcome is:

Management of Commonwealth reserves as outstanding natural places that enhance Australia’s well-being through the protection and conservation of their natural and cultural values, supporting the aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in managing their traditional land and sea country, and offering world class natural and cultural visitor experiences.

1.6 In pursuit of this outcome, the Director has three goals and objectives:

- resilient places and ecosystems — to protect and conserve the natural and cultural values of Commonwealth reserves;

- multiple benefits to traditional owners and local communities — to support the aspirations of traditional owners in managing land and sea country; and

- amazing destinations — to offer world class natural and cultural experiences, enhancing Australia’s visitor economy.

1.7 Under the EPBC Act, the Director is required to establish 10-year park management plans for each national park to give effect to these goals. An approved plan is a legislative instrument under the EPBC Act. These documents describe the direction of management for the park and specify conditions and decision-making arrangements to authorise activities that would otherwise be prohibited under the Act. Park management plans are also designed to help reconcile competing interests and identify priorities for the allocation of funding and resources.

1.8 Uluru-Kata Tjuta, Kakadu and Booderee national parks are wholly or partly owned by the traditional owners and leased to the Director under legislation.4 The Memoranda of Leases are legally binding agreements — with terms ranging from 86 to 99 years — that together with the EPBC Act, establish the basis for joint management of the parks by the traditional owners and the Director. Joint management is given effect through boards of management.5

1.9 The EPBC Act subsection 376(1) provides that the role of a board of management is to make decisions relating to the management of the relevant national park consistent with that park’s management plan, and in conjunction with the Director to:

- prepare management plans for the park;

- monitor the management of the park; and

- advise the Minister on future development of the park.6

1.10 For jointly managed parks, park management plans must also be consistent with the lease agreements. An outline of the legislative and management framework for the management of Commonwealth national parks is presented in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Commonwealth national parks legislative and administrative framework

Source: ANAO based on Director of National Parks information.

1.11 The Director’s governance arrangements include an Executive Board and Project Board comprising of senior executive staff who are located at central office. The Director is assisted on-park by park managers, which report to the central office and boards of management at jointly managed parks. At the island parks, park managers are assisted by non-statutory advisory committees. These governance arrangements are outlined in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Director of National Parks governance arrangements

Source: ANAO based on Director of National Parks documentation.

1.12 The Director has identified a number of external factors that influence operations of the national parks, which include:

- pressures on terrestrial biodiversity such as habitat loss and changing land use that shape priorities, decisions and activities;

- obligations to traditional owners to protect the natural and cultural values of the parks;

- a changing climate that increases extreme weather and fire risk; and

- the motivation and demands of visitors to the parks.

1.13 Core park management activities undertaken across all sites include invasive species control, threatened species monitoring, asset maintenance, visitor and park use management, and community and stakeholder engagement. The Director also provides housing for staff within the parks and manages the provision of essential services (power, water and sewage) at the Muṯitjulu community within Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park.7

1.14 For 2017–18, the Director reported operating expenditure for the six parks of $47 million and $17.3 million in external revenue from permits and entry fees. The Director also has capital management responsibilities with almost 1,700 assets valued at $202 million across the six parks. Proportions of total expenditure for each park are shown in Table 1.1. The total ongoing Parks Australia staff by function and location at February 2019 is outlined in Figure 1.4.

Table 1.1: Director of National Parks’ 2017–18 expenditure by park

|

National park |

Operating costs |

Proportion |

|

Kakadu |

$19,849,000 |

42% |

|

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa |

$13,967,000 |

30% |

|

Booderee |

$7,624,000 |

16% |

|

Christmas Island |

$3,963,000 |

8% |

|

Norfolk Island |

$1,121,000 |

2% |

|

Pulu Keeling |

$425,000 |

1% |

|

Total |

$46,949,000 |

100% |

Source: Director of National Parks Annual Report 2017–18, Table 5, p. 11.

Figure 1.4: Director of National Parks staffing by function and location at February 2019

Note: Includes part-time and full-time ongoing staff and excludes casual and non-ongoing staff.

Source: ANAO analysis of Parks Australia staffing data as of February 2019.

Recent developments

1.15 In January 2019 the Government announced additional funding of up to $216 million to upgrade Kakadu National Park and support the township of Jabiru to transition to a tourism-based economy following the closure of the Ranger mine (located within the national park) by 2021.

Previous audit coverage

1.16 This is the second audit undertaken by the ANAO into the management of Commonwealth national parks. The previous audit, Auditor-General Report No. 49 2001–02, The Management of Commonwealth National Parks and Reserves, made 12 recommendations including strengthening strategic planning arrangements; incorporating targets and timeframes in future management plans; improving contract management arrangements; and enhancing public reporting. Eleven recommendations were agreed and one was agreed with qualification.8 This report refers to these recommendations to the extent that they are relevant to this audit.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.17 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Director’s management of the six terrestrial Commonwealth national parks. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Are appropriate governance arrangements in place to support strategic risk management and business and operational planning?

- Are national park business management and operational plans effectively implemented?

- Does the Director effectively measure, monitor and report on park operational activities?

1.18 The audit scope included the Commonwealth managed national parks of Kakadu, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa, Booderee, Christmas Island, Norfolk Island and Pulu Keeling. The audit scope did not include the management of marine park reserves or the Australian National Botanic Gardens.

Audit methodology

1.19 In conducting the audit, the ANAO:

- examined records, systems, and procedures relating to risk management, business planning, corporate support and operational activities;

- conducted fieldwork at the mainland parks to observe park activities, values and assets;

- interviewed departmental staff associated with each of the six parks and staff based in the Canberra central office, traditional owners and board members from each of the three jointly managed parks, and a range of external stakeholders.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $461,000.9

1.21 The team members for this audit were Mark Rodrigues, Dr Shay Simpson, Taela Edwards, Pauline Ereman, Kate Wilson, Isaac Gravolin and Michael White.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Director of National Parks (the Director) has established appropriate governance arrangements to support strategic risk management, and business and operational planning.

Conclusion

Governance arrangements to support the Director’s management of national parks do not adequately support the delivery of corporate services, risk management, planning, and engagement with traditional owners to the benefit of park management objectives.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at strengthening the Director’s risk management and business planning. The ANAO also suggested that the Director develop an engagement strategy to support its engagement with the traditional owners at jointly managed parks.

Have the Director and the Secretary established appropriate administrative arrangements to support park management?

The Director and the Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Energy have not established appropriate administrative arrangements to support park management. The arrangements between the two accountable authorities were set out in a 2001 memorandum of understanding and a 2013 service delivery agreement. Neither document fully reflects current practice, giving rise to duplication in corporate support and reduced effectiveness and efficiency in park management. The current review of administrative arrangements should be expedited to address these issues.

Governance and accountability

2.1 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out key responsibilities of accountable authorities. These responsibilities, as outlined in the Department of Finance resource management guide for accountable authorities, are to establish appropriate systems and processes to: promote the proper use and management of public resources; maintain risk oversight and management; encourage working with others to achieve common objectives; and minimise undue administration.10

2.2 The Director is assisted by staff from Parks Australia — a division of the Department of the Environment and Energy — provided by the Secretary of the department under a 2001 memorandum of understanding (MOU). The MOU provides for the Secretary of the department to delegate powers to the Director to engage and manage departmental staff for the national parks function. The MOU also requires the Secretary and the Director to negotiate service provider arrangements covering major aspects of their business relationship in the service delivery agreement (SDA).

2.3 The first SDA was established under the MOU in 2001 and has been periodically renewed, most recently in 2013. Shared corporate services covered by the SDA include risk management, budget strategy, media monitoring, participation in departmental committees, workforce planning and data reporting, enterprise agreement negotiation, and various human resources functions, for example, payroll, recruitment and learning and development.

Relevance and currency of governance relationships

2.4 The MOU contains outdated provisions including references to Outcome 1 of the former Department of the Environment and Heritage, and financial and reporting obligations under the repealed Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997. While the MOU is to be in effect unless specifically terminated, amended or replaced, the Director advised the ANAO that work to renew its relationship with the department has focused on the SDA, rather than the MOU.

2.5 In February 2015 the Director noted that the services of the department were underutilised and duplicated. Examples of differences in business functions between the SDA specifications and the actual services provided are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Service specifications at 2013 compared with service provision at 2019

|

Function |

Service agreement at 2013 |

Practice at 2019 |

|

Business management and oversight committees |

The department and Director will maintain separate audit committees. |

A portfolio audit committee was established in 2015 reporting to the Secretary of the department, the Director and the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust Board. |

|

Risk management |

The department will provide a risk management system including training to use the system, and to promote the use of template risk documents. |

The Director maintains its own risk framework, systems and procedural documents. |

|

Learning and development |

The department will ensure the development of capability frameworks and departmental learning and development strategies take account of the needs and circumstances of Parks Australia staff. |

Parks Australia and park managers determine on-park capability needs and are responsible for ensuring that staff meet those needs. |

|

Work health and safety: development and maintenance of policy, procedure and guidance |

The department will develop health and safety operational arrangements for all staff, including those working for the Director. |

The Director has its own work health and safety management plan and maintains its own documentation and document database. Departmental documentation often excludes information relevant to Parks Australia staff. The Director also retains park-specific policies. |

Source: Director of National Parks review of its SDA and ANAO analysis.

2.6 The misalignment between current practice and the service arrangements as set out in the SDA gives rise to duplication in the delivery of corporate services by both entities. This reduces the effectiveness and efficiency of services to support the management of national parks. Since 2013 there have been three reviews of the service delivery arrangements between the two entities, commenced by the Secretary or Director, as outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Reviews of service delivery arrangements

|

Duration |

Focus |

Project status |

|

February to November 2015 |

Review of SDA provisions. Initiated by the Director. |

The project was suspended due to:

|

|

2018 |

Development of a heads of agreement to replace the current SDA. Joint departmental and Director review. |

Review not completed. |

|

2019 |

Operations and corporate change project to support the Secretary and the Director to deliver joined-up, efficient and streamlined enabling services, articulating mutual accountabilities and responsibilities in the management of safety, security, human and financial resources and improving transparency of the cost of services. |

Scheduled to be completed in August 2019. As part of the project, in March 2019 the Director commissioned a review of corporate service functions in Parks Australia, to be completed by 30 April 2019. The review is intended to contribute to the project deliverables including the new model for delivery of corporate services. |

Note a: The Functional and Efficiency Review recommended that Parks Australia Division and the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust be merged into one independent entity. If not agreed, then the Director of National Parks’ corporate Commonwealth entity designation should be removed and the position embedded in the department as a senior executive service officer, but continuing as a statutory office holder under the EPBC Act. Neither of these recommendations were implemented.

Source: ANAO analysis of Director of National Parks’ records.

2.7 These reviews have not resulted in any change to the SDA. Given the differences in the delivery of shared services from those set out in the SDA, and the length of time since it was last renewed, the current review of administrative arrangements between the department and the Director should be completed as soon as possible.

Does the Director of National Parks effectively manage the risks to the objectives of the parks?

The Director does not effectively manage risks to the objectives of the parks. The Director’s risk management framework lacks engagement with boards of management on risk oversight. The implementation of the framework has been undermined by a lack of suitable system support to record risks and monitor the implementation of treatment measures. There is also scope for the Director to strengthen its management of climate, probity and compliance risks.

Risk management framework

2.8 The Director has established a risk management framework comprising of chief executive instructions, policies, procedures and templates. The framework was developed to comply with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 2014 and AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management — Principles and guidelines.

2.9 The Director’s risk management policy and associated guide have been regularly reviewed. The risk management policy defines: how the framework supports strategic objectives; key accountabilities and responsibilities for risk management; and risk appetite for set categories of risk.11 Related policies and their risks, including the business continuity policy and the fraud policy statement, are given effect through set risk categories to inform the assessment of a risk.

2.10 The risk management policy distinguishes four types of risks:

- strategic — risk assessment on a quarterly basis by the Executive;

- operational — risk assessment for all parks in development of annual operational plans by park managers;

- project — risk assessment as part of all project plans by project managers; and

- speciality — work health and safety, and procurement risk assessments as required by relevant staff, and fraud risk assessments by the risk manager every two years.

Strategic and operational risk management

2.11 Risk analysis, evaluation, and treatments are recorded by park, branch and section, managers using spreadsheet templates. Risks rated high and extreme are required to have: a risk treatment plan; proposed treatments recorded in the corrective action register; and are to be included in the risk watch list. Table 2.3 lists examples of strategic and operational risks included on the Director’s risk register at February 2019.

Table 2.3: Example strategic and operational risks

|

Strategic risks |

Operating risks |

|

|

Source: ANAO summary of Director of National Parks information.

2.12 Since November 2016 a number of issues with the corrective action register (a spreadsheet) have reduced the effectiveness of the risk identification and reporting process. These issues include: staff not adding corrective actions when required12; missing dates for intended completion and allocation of responsibility13; and undocumented completion of corrective actions.14 The Director informed the ANAO that technical issues prevented staff from accessing the register in 2018, resulting in new items not being registered and completed items not being closed.15

2.13 The Director’s corrective action register policy provides a suggested timeframe of seven days for the commencement of corrective action tasks for risks rated as high and within 24 hours for risks rated as extreme. In reference to the completion of tasks, the policy provides guidance on factors to consider when allocating a completion time and requires items that are not completed within three months to be reported to the Executive Board.

2.14 As at March 2019 there were 45 actions rated as high in the corrective action register that were not completed for the six Commonwealth national parks, with only four containing a nominated date for completion. These actions comprised:

- 27 from Kakadu — 26 raised in September or December 2016 and one in September 2017;

- 17 from Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa — seven from December 2015 and 10 from November 2016; and

- one item from Booderee raised in December 2016.

2.15 High and extreme rated risks are also to be included on the risk watch list. The risk watch list is a spreadsheet that applies a number of categories to calculate and assign risk ratings. Individual risks are grouped in categories linked to controls and proposed treatments. However, as the template requires groups of risks to be linked to groups of controls, there is no clear line of sight between individual risks and their specific control measures.

2.16 In previous audits of other entities, the ANAO has noted weaknesses in the use of spreadsheets as a primary tool for managing business information, including risk management.16 Spreadsheets lack formalised change and version control and reporting, increasing the risk of error. This can make spreadsheets an unreliable tool in handling corporate data, as accidental or deliberate changes can be made to formulae and data without there being a record of when, by whom, and what change was made.

Consideration of specific risks

Climate risks

2.17 Consideration of climate risks were evident in the risk watch lists for three of the six parks (Kakadu, Christmas Island and Pulu Keeling).17 Climate risks are contained in the risk category of ‘natural heritage management’ with four sub-categories that relate to impact on native flora, fauna, ecological communities and off-site conservation. Where climate risks are identified, the response strategy is to ‘share’ the risk with internal or external stakeholders.18 This provides no insight into the Director’s mitigation actions against climate risk.

Probity risks

2.18 All staff are required to disclose material personal interests relating to the affairs of the Director of National Parks19, although this is not outlined in the Director’s chief executive instructions. The draft of the revised chief executive instructions requires all staff to declare a material personal interest that relates to the affairs of the Director as soon as it is identified.

2.19 The Director has established a conflict of interest declaration form for staff participating on procurement panels. This form, however, does not make reference to any guidance or the department’s existing conflicts of interest policy. The Director does not support disclosure requirements with appropriate guidance. As a result, there is a risk that disclosures do not reflect the actual spread and level of conflicts of interest.

Park regulation compliance risks

2.20 The Director has responsibilities for regulating park users’ compliance with provisions of the EPBC Act and to apply a risk-based approach to its compliance activities. The Australian Government regulator performance framework notes that ‘comprehensive risk assessment processes are essential to ensuring that resources are targeted to the areas requiring the most attention’.

2.21 All park management plans recognise the need to assess compliance risks to target compliance activities and include provisions for boards of management to oversee park policies, plans and procedures. The Director’s compliance and enforcement manual also requires that each park produce an annual strategy or update for compliance and enforcement activities.

2.22 The ANAO reviewed the extent to which the Director had undertaken compliance risk assessments to inform its delivery of compliance activities. For the three financial years to 2018–19 there was only one instance (Booderee) of a compliance risk assessment being completed, in association with park annual operational plans, and provided to the Executive Board. Two instances were identified where a board of management (Booderee) was provided with a compliance risk assessment for noting in 2017 and 2018. There were no records of the boards of management endorsing compliance risk assessments or compliance plans.

2.23 There is scope for the Director to share information on compliance and enforcement across individual parks as recommended in the 2002 ANAO report and agreed at the time by the Director.20 This would assist in sharing better practice lessons and strengthening the consistency of compliance and enforcement responses across the parks.

Oversight of risk management

2.24 Regular and structured review of risk contributes to embedding systematic risk management into business processes. This includes enterprise-level risks and the monitoring of the status of risk controls and treatments by governance committees, the Executive Board and the audit committee.

2.25 The Executive Board is the key forum responsible for oversight of strategic policies and direction, reviewing risks, monitoring treatment plans and providing strategic advice and guidance to the Director. Risk reports have been a standing agenda item at the Executive Board since November 2016. This reporting is based on risk watch lists and consists of a briefing note outlining current issues and any recommended response, together with a ‘risk and opportunities’ summary. Risks are also reported monthly to the Executive Board through standing agenda items of: work health and safety; financial reporting; and legal reporting.

2.26 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) provides that the functions of an entity’s audit committee must include review of the appropriateness of the accountable authority’s system of risk oversight and control. In July 2017 the Director provided the audit committee a copy of its risk management policy to note. The committee noted the Director’s risk management policy, but did not provide the Director with assurance on the appropriateness of the policy. The Director has provided regular risk reports to the audit committee that have been noted or discussed at a high level.

2.27 The boards of management for the jointly managed parks are not specifically required to identify risks, contribute to risk assessment or oversee risk treatments. Over the past three financial years, the boards have not directly been included in risk oversight. For example, they have not reviewed park risk registers. Given the statutory role of boards of management to make decisions relating to the management of the park, there is merit in the Director engaging with boards of management in its risk management and oversight activities.

Recommendation no.1

2.28 The Director of National Parks:

- review its risk management framework to ensure that it is appropriately engaging with boards of management in its management of risk; and

- implement suitable system support to identify and document its strategic and operational risks, and to monitor the implementation of treatment measures across strategic and operational risks.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

2.29 A review of the Director’s risk management framework has commenced and will be completed in the next six months. The Director is committed to strengthening the management of risk, including through the role that boards of management deliver for jointly managed national parks. The Director also receives advice from the Portfolio Audit Committee on the appropriateness of its system of risk oversight and control. The Director is currently working with the Department of the Environment and Energy to develop a new risk and incident management system in the next 12 months that will better record risks and monitor the implementation of treatment measures. To ensure best practice, this includes the Portfolio Audit Committee having oversight of the review of existing procedures in place to monitor strategic risk.

Does the Director of National Parks’ planning framework support the development of well aligned plans?

The planning framework established by the Director does not support the development of well aligned plans. Annual operational plans do not clearly indicate how they contribute over time to the objectives of the park management plans. Operational plans are not informed by input from boards of management in jointly managed parks.

2.30 The Director has statutory requirements to develop and implement a range of plans. These include an annual corporate plan and 10-year park management plans. The park management plans and the Director’s own internal planning requirements establish further obligations for the Director to develop implementation schedules, operational plans, and subsidiary plans specific to particular lines of business, such as threatened species plans. The relationship is outlined in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Key plans of the Director of National Parks

Source: ANAO based on Director of National Parks information.

Corporate planning

2.31 The PGPA Act requires the Director, as the accountable authority, to prepare and publish an annual corporate plan. The corporate plan is intended to be the primary planning document, setting out an entity’s purpose, and strategies to achieve its purpose. The Director of National Parks Corporate Plan 2018–2022 outlines three corporate objectives:

- protect and conserve the natural and cultural values of the parks;

- support traditional owners in managing their country; and

- offer world class natural and cultural experiences to enhance the visitor economy.

2.32 The Director has in place a high-level planning framework that provides a structured process for development of the corporate plan. Senior management were engaged in the development of the corporate plan through a staff leadership forum and a corporate planning workshop. The corporate plan itself includes schedules of other key planning activities relating to the development of management and operational plans. The specific requirements of the PGPA Rule are included in the Director’s 2018–2022 Corporate Plan.

Park management plans

2.33 The Director is required under the EPBC Act to develop a management plan for each of the national parks, and to do so in conjunction with the boards of management for the three jointly managed parks. Park management plans are to be in place at all times after the first plan takes effect.21 While all parks currently have a management plan in place, most have had a period of two years or more without a management plan, as summarised in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Terms of current and previous park management plans

|

National Park |

Term of current management plan |

Term of previous management plan |

Time elapsed between management plans |

|

Norfolk Island |

2018–2028 |

2008–2018 |

1 month |

|

Kakadu |

2016–2026 |

2007–2014 |

2 years |

|

Booderee |

2015–2025 |

2002–2009 |

6 years and 8 months |

|

Pulu Keeling |

2015–2025 |

2004–2011 |

4 years and 4 months |

|

Christmas Island |

2014–2020 |

2002–2009 |

4 years and 11 months |

|

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa |

2010–2020 |

2000–2007 |

2 years and 9 months |

Source: ANAO based on Director of National Parks information.

2.34 All current park management plans were informed by the views of stakeholders, and identify success factors and related activities. All current plans include a review point during their ten-year implementation period — a technical audit prior to development of the subsequent plan.22 Most of the park management plans (except for those of Uluru-Kata Tjuta and Norfolk Island) outline how lessons from the previous plan have been incorporated into the current plan.

2.35 All park management plans include actions. These actions cover natural resource and cultural heritage management, commercial tourism, outstation management, safety and incident management, authorising processes, business development, compliance and enforcement, and capital works. The number of actions range from 172 in the Kakadu plan to 40 actions in the Pulu Keeling plan. These actions, however, are not linked to specific timelines for implementation, or performance measures, targets or benchmarks. This deficiency was recognised in the 2002 ANAO report that recommended park management plans or subsidiary documents address ‘core performance indicators, targets and priority actions’ with a view to strengthening strategic planning.23 This recommendation, while agreed at the time by the Director, has not been implemented.

Implementation schedules

2.36 All park management plans include an action to develop an implementation schedule as a means to determine and report on annual priorities. The Director does not have a structured approach to the development or use of implementation schedules. Two of the six parks (Booderee and Kakadu) have an implementation schedule in place. These implementation schedules quantify and track progress against park management plan actions.

2.37 The inclusion of a schedule of priority activities and timeframes in future park management plans was recommended in a discussion paper to the Executive Board in November 2016. The paper referenced the 2002 ANAO recommendation that encouraged clearer priority setting at a park level to assist in dealing with the hundreds of actions included in some of the statutory park management plans.24 The paper reviewed best practice for management planning and stated ‘the implementation of a management plan needs to be calculated outside the management plan document itself to allow for consideration of available resources and prioritising’. The Director is not well positioned to assess the progress of park management plans in the absence of implementation schedules.

Operational plans

2.38 The Director requires that all parks have an annual operational plan in place. Annual operational plans are intended to: be developed concurrently with park budgets; and include a schedule of activities proposed for implementation throughout the financial year. The plans are to be prepared in a spreadsheet template, aligning each listed activity to a corporate strategy goal/s and an action of the respective park management plan. The operational plans outline:

- business-as-usual activities funded through an individual parks’ operational budget;

- projects funded through other sections within Parks Australia Division;

- capital and infrastructure works funded through a centralised capital budget; and

- activities funded externally, such as through partnerships or grants.

2.39 The ANAO reviewed the operational plans for each park from 2016–17 to 2018–19. All plans set out business-as-usual activities, projects, capital and infrastructure works and other partnership activities. The operational plans contained links to corporate and park management plan objectives and were consistent with park-based operational risks and treatments.

2.40 Annual operational plans are required to be provided to the Executive Board for review and endorsement. For the three financial years to 2018–19, operational plans for all six parks were provided to the Executive Board with the exception of two instances (two out of 18). Of those provided, the Executive Board recorded fourteen plans as ‘noted’ and two as ‘endorsed’.

2.41 The majority of operational plans were provided to the Executive Board two to three months after the commencement of the relevant financial year. As these plans come into effect after the date of their formal commencement, the extent to which the plans can determine priority actions for the financial year is limited.

2.42 Park management plans for the three jointly managed parks contain provisions for the review of park policies, procedures, strategies and plans by the respective board of management. In practice, the provision of annual operational plans to boards of management for information or consultation has varied. For the three financial years to 2018–19, the Kakadu Board of Management was not provided the operational plan, the Booderee Board of Management was provided one operational plan for noting, and the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management was provided with two operational plans for endorsing high-level priorities.

Performance monitoring plans

2.43 The Director requires performance monitoring plans to be established for each park. These plans are intended to provide evidence about the Director’s performance in managing each park and enable adaptive management and decision-making about park activities and investments. At February 2019, three performance monitoring plans had been approved.25

Plan alignment with subsidiary strategies

2.44 Park management plans are overarching documents that enable the development of subsidiary or lower-level strategies for specific activities, such as fire management and tourism. Accordingly, operational plans should prioritise and incorporate actions from all plans including those prescribed in park management plans, implementation schedules or other subsidiary strategies.

2.45 Five parks were identified as having subsidiary strategies: 14 at Kakadu; five each at Uluru-Kata Tjuta and Booderee; and two each at Norfolk Island and Christmas Island. Of these, four showed alignment of actions between operational plans and all subsidiary strategies for the three financial years to 2018–19. Kakadu’s operational plans aligned with all except two of their lower level strategies. While the jointly managed parks have a greater number of subsidiary strategies, their operational plans showed fewer references to subsidiary strategies.

2.46 Four of the six park management plans include an action to implement, review, update or develop a climate change strategy. The exceptions are: Norfolk Island, which contains an action to implement the Director’s draft climate change statement26; and Pulu Keeling, which contains a general reference to possible management actions. Each park established a five-year climate change strategy with the earliest commencing 2010 and the latest expiring in 2017. There has been no specific climate change plan or strategy in place since 2017. The Director intends to consult with the boards of management to finalise its new climate change statement in 2019.

Recommendation no.2

2.47 The Director of National Parks review its planning framework to ensure that it is: meeting the requirements of the EPBC Act; efficiently meeting the objectives and goals of the Director; and effectively discharging the responsibilities of all parties involved in the management of the national parks. This should, where relevant, be:

- supported by implementation schedules and aligned with other relevant plans;

- informed by input from relevant stakeholders; and

- endorsed by an appropriate oversight body.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

2.48 The Director considers that it is operating according to the requirements of the EPBC Act, however will review its planning framework to improve the implementation of management and operational plans and stakeholder engagement approaches. This review will be informed by stakeholder, Joint Boards of Management, and Portfolio Audit Committee input. In addition, the Director will be providing governance training for all Joint Boards of Management over the next twelve months.

Does the Director of National Parks effectively engage with its stakeholders?

While meeting statutory engagement requirements, feedback to the ANAO on the effectiveness of the Director’s engagement with stakeholders has been mixed. In particular, there is criticism that the Director has not effectively engaged the boards of management to establish constructive relationships with traditional owners at the jointly managed national parks.

2.49 The Director has a number of formal and informal relationships in place to support its management of national parks. The ANAO reviewed the Director’s engagement with stakeholders in the development of park management plans. The ANAO also interviewed a range of stakeholders over the course of the audit, including:

- traditional owner and non-Indigenous members of the boards of management;

- representatives of the advisory committees of the island parks; and

- representatives of land councils and trusts, conservation partners, tourism operators, adjacent land managers, and relevant state and local government entities.27

Stakeholder engagement in the development of park management plans

2.50 The EPBC Act requires the Director to facilitate two formal periods of public comment when developing park management plans.28 The first period invites submissions on the proposal to prepare a plan, and the second seeks comment on the draft plan. Ministerial approval is required for all park management plans. In seeking ministerial approval, the Director must also provide:

- any comments received in response to the draft plan; and

- the views of the Director and, where relevant, those of the appropriate board of management on the comments.29

2.51 The Director has fulfilled its obligations under the EPBC Act for stakeholder engagement for the five management plans approved from 2014. The Minister was provided assurance that public comments were considered through a report by the Director that accompanied each management plan for ministerial approval. These reports listed the response or changes made to the draft for each public comment.30 The Director could enhance transparency of stakeholder engagement by publishing the Director’s responses to submissions.

Stakeholder engagement on park management activities

2.52 The Director has not established an enterprise wide communication strategy or plan to guide its interactions with stakeholders. The Director informed the ANAO that stakeholder engagement is considered on a place or project basis. In practice, stakeholder engagement largely occurs at a park-based operational level through boards of management, ranger activities, and non-statutory advisory committees. The Director funds liaison positions, hosted by external groups, at the jointly managed parks to facilitate consultation with traditional owners.31

2.53 For the island parks, non-statutory committees provide a forum for stakeholder engagement. Although these committees vary in relation to their function and breadth of stakeholder interest, all serve as a conduit for engagement. The committees associated with Christmas Island32 and Pulu Keeling33, provide technical input on projects and issues. Specific committees for the Norfolk Island and Pulu Keeling parks34 are recognised in respective park management plans as the primary liaison mechanism with the local community in development of plans and for significant issues relating to the parks. Park managers viewed these committees as a sounding board to assist with park management.

Stakeholder comments provided to the ANAO

2.54 Some stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO indicated that they were satisfied with their interactions with the Director. These stakeholders commented on positive relationships, sufficient community consultation, strong collaborative partnerships and a good flow of information. These stakeholders referred to their interactions with the Director as professional, co-operative and collaborative. These stakeholders tended to be from the other government entities and natural resource management organisations.

2.55 Other stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO reported disconnects in communication, unresponsiveness, and poor engagement with Aboriginal communities. They indicated a desire for more formal engagement and transparency. These stakeholders tended to be traditional owners or other individuals and organisations involved with Aboriginal communities.

Issues raised by traditional owners

2.56 In each of the jointly managed parks, traditional owners informed the ANAO that they did not feel that they were fully participating as joint managers, thereby hindering the achievement of park management objectives.35

2.57 Key issues raised by traditional owners covered the following matters:

- deficiencies in communication, consultation, and the provision of information;

- lack of employment pathways and training for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to assist them to progress beyond entry level positions; and

- failure to implement park management plans, decisions of boards of management, and lease obligations.

2.58 These concerns have previously been raised by traditional owner board members at board meetings and conveyed to the Director. Correspondence and board papers note that traditional owners have been ‘very unhappy with the current state of joint management’, that ‘joint management is not working’ and ‘the principle of joint management has disappeared’.

2.59 The Director and park managers have commenced action in response to these concerns. This response has included establishing the new role, Joint Management Officer at Kakadu National Park, which is intended to lead implementation of the joint management section of the Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016–2026.

2.60 Since 2017, all three boards of management have requested a lease review, with the Booderee Board of Management issuing a formal notice of dispute.36 Lease reviews have not commenced.37 In December 2018, the Director commenced an internal audit to ‘evaluate the effectiveness of the Director’s frameworks for managing lease responsibilities, compliance by the Director in meeting lease conditions, and the effectiveness of the Director’s approach to lease reviews and consultation strategies’. The final report was scheduled for the end of September 2019.

2.61 The Director has established a marine parks Indigenous engagement program, a Parks Australia approach for Indigenous engagement on Commonwealth marine reserves, and best practice principles for Indigenous engagement on Commonwealth marine reserves. The Director has not established similar guidance for terrestrial parks. There is scope for the Director to develop an engagement strategy to support its engagement with the traditional owners at jointly managed parks.

3. Implementation of plans

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether corporate, park management and operational plans are effectively implemented.

Conclusion

The Director has not established robust arrangements to ensure that corporate, park management and operational plans are being implemented.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving the oversight of corporate, park management and operational plans, maintaining procedural guidance and managing projects. The ANAO also made a number of suggestions to improve the Director’s support for boards of management and to strengthen its approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff development, and broader staff training and performance management.

Are robust arrangements in place to monitor the implementation of corporate, park management and operational plans?

The arrangements to monitor the implementation of actions as set out in corporate, park management and operational plans are not robust. There is scope for the Director to improve the induction and professional development it provides to boards of management to support their oversight role.

3.1 Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), the Director is required to give effect to a park management plan.38 As a consequence, actions prescribed in park management plans are required to be implemented. Regular review and monitoring of the implementation of plans are important for maintaining accountability and for adjusting activities to ensure they are on track to meet established targets.

3.2 As noted in paragraph 2.25, the Executive Board is responsible for oversight of strategic policies and direction, including the review of reporting against plans. For jointly managed parks, the monitoring of park management plans is conducted through statutory boards of management. Non-statutory committees have been established in the island parks to assist park management.

Executive Board oversight

3.3 The Director’s requirements include that park managers are to report to the Executive Board on measures outlined in the corporate plan, park management plans and on operational plans. The ANAO reviewed the meeting papers of the Executive Board and found that, in practice, the Executive Board has not consistently reviewed reports on plans.

3.4 In 2017–18, each park manager submitted a report on its performance against the corporate plan. In 2016–17 corporate plan performance reports were not provided from Kakadu and Booderee. Operational plans were only presented to the Executive Board once a year for endorsement without follow up reporting on the implementation of those plans.

3.5 The Executive Board secretariat maintains an actions and decisions register from each meeting. Where reports on corporate plan measures were provided to the Executive Board, the register indicates that these reports were considered and discussed. Corporate plan reporting on an annual basis does not provide an opportunity to identify any implementation issues, respond to those issues, and measure the impact of the response during the course of one year.39

3.6 Reports on park performance monitoring plans are required to be provided to the Executive Board on an annual basis. The performance monitoring plan reports provide an assessment against the previous year for the performance indicators contained in park management plans. Each park provided these reports to the Executive Board in 2017–18, except Booderee. In 2016–17 there was no reporting from the Booderee, Norfolk Island and Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa national parks.40

3.7 Reporting on performance monitoring occurs in a standard format and is often accompanied by a covering brief that highlights key points. This format, demonstrated in Figure 3.1, includes a scorecard to describe the assessment of performance indicators, the trend since the last report, and the confidence rating of the data used to form the assessment.

Figure 3.1: Example of performance reporting to the Executive Board

Source: Christmas Island National Park performance monitoring plan reporting 2017–18.

3.8 The actions and decisions register indicates that the Executive Board has used the performance monitoring reports to consider park related projects and park performance information. While the reports provide an opportunity to identify activities to prioritise in operational plans, the frequency of these reports do not provide the opportunity to identify, respond to and monitor any issues within a year.

Joint management oversight

3.9 As noted in paragraph 1.8, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa, Kakadu and Booderee national parks are jointly managed by boards of management and the Director. Receiving appropriate reporting on park management activities, such as the implementation of park management and operational plans, enables the boards of management to fulfil their oversight functions under the EPBC Act — to monitor the management of the park. The ANAO reviewed available meeting papers for the three boards from 2016 to 2018.41

3.10 The Director’s reporting to the boards of management on the implementation of park management plans is not consistent across the parks and within each park over time. Reporting to the boards of management largely takes the form of ‘park manager reports’. These reports range from 350 to 3,500 words, detailing the operational activities of the previous quarter, which are grouped under the broad objectives of the park management plan at Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa and Kakadu. These reports do not provide a clear line of sight against the actions in either the operational or park management plans, making it difficult for a reader to determine how the Director is progressing against those plans.

3.11 There is significant variation in reporting provided to boards of management by the Director on implementation of management plans. Throughout 2016 to 2018, this included:

- March 2018 — the Kakadu Board of Management was provided with a draft ‘performance monitoring plan’.

- February 2018 — the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management approved a performance indicator monitoring plan. Reporting against this plan was provided at two meetings, but it was not considered during the meetings.

- 2016 to 2018 — the Booderee Board of Management was provided with various forms of an implementation schedule and report.

3.12 The ANAO observed some examples of reporting that could contribute to effective oversight of the implementation of the park management plans. However, these reports were recent initiatives, one-off mid-term reports, or otherwise inconsistently presented.42

3.13 The ANAO observed mixed practices of financial reporting to boards of management. Financial reporting to the boards of management has included:

- Kakadu — an info-graphic depiction of expenses and revenue at each meeting of the board since March 2017 and a finance sub-committee, which has input on matters such as prioritising projects for capital funding and budget planning.

- Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa — an info-graphic depiction of expenses and revenue at each board meeting from 2016 to early 2017. There was no financial reporting to the board of management from mid-2017 to 2018.

- Booderee — agenda items with titles such as ‘revenue report’, ‘operational expenses report’, and ‘financial report’, with limited consistency in the type or extent of information.

3.14 The reporting provided to the boards of management does not position the boards to assess the extent to which the Director is on track to implement its commitments under park management and operational plans.

Recommendation no.3

3.15 The Director of National Parks strengthen its arrangements to monitor the implementation of the corporate, park management and operational plans.

Director of National Parks response: Agreed.

3.16 The Director is committed to strengthening its arrangements to monitor corporate, park management, and operational plans. A review of strategic plan monitoring processes has commenced and will be completed in the next twelve months. The Director is assisted in this role with the recent establishment of a performance monitoring sub-committee of the Portfolio Audit Committee. The Director is developing a monitoring, evaluation reporting and improvement framework that will provide a foundation for objective and more transparent reporting. The Director is also increasing the level of professional development provided to boards of management by providing governance, numeracy and literacy training.

Support provided to boards of management

Board rules and evaluation

3.17 Each board of management has board rules in place that are consistent with the key requirements of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (EPBC Regulations), including the meetings of boards and disclosure of the interests of board members.43

3.18 The boards are to meet four times each year or quarterly. From 2016 to 2018, the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa and Kakadu boards met and reached quorum on average four times per year.44 The Booderee Board of Management met and reached quorum on average three times per year.45

3.19 The EPBC Regulations specify that a board member who has a direct or indirect financial interest in a matter on the agenda must declare the interest at the meeting, and that interest must be recorded in the minutes for the meeting.46 In addition, the rules of each board specify that a member who feels they have another type of conflict should disclose this at the meeting. From 2016 to 2018 there was one instance at each of the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa and Kakadu boards of a board member declaring a conflict, and multiple declarations by multiple Booderee board members.47

3.20 The Director does not have arrangements in place to evaluate the performance of the boards of management. Implementing processes for regular and rigorous evaluation of the performance of the boards, and addressing any issues that may emerge from those processes, is important for effective ongoing operation of the boards.48

Induction of board members

3.21 A key role of entities in supporting effective boards is the provision of adequate induction and on-going professional development to ensure board members are equipped to undertake their duties. The provision of appropriate training is particularly important where new board members may have limited experience in probity and corporate governance.49

3.22 Board members are notified of their appointment by the Minister. Correspondence includes details of the board member’s term of appointment and their responsibility to follow a code of conduct. Parks Australia Division informed the ANAO that board members are also provided with the relevant version of the code of conduct and board rules. In addition, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa board members are provided with a handbook. This handbook is a plain English explanation of the role of the board and the responsibilities of board members. Board members in the other jointly managed parks may benefit from similar guidance documents.

3.23 The Director does not have an established approach for inducting new board members. Induction processes have ranged from three-day training for the Kakadu traditional owner board members, a presentation at the first board meeting of the current Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management, to no induction for the Booderee Board of Management members. Board members may be better supported with an approach that ensures all board members receive an induction that covers an appropriate level of information relevant to board duties.

On-going professional development of board members

3.24 The Director does not have an established approach to ongoing professional development of board members, and practices vary considerably between the jointly managed national parks.50 The importance of training for board members, with focus on their legislative roles and responsibilities, was the basis of a recommendation from the 2002 ANAO report with which the Director agreed.51

3.25 Since their induction in April 2016, and a presentation at the first meeting of the current board in May 2016, the Kakadu board members have not received further training or development. The board requested training from the Director in November 2016. This training was not provided despite four follow up requests.52 The Director was unable to provide the ANAO with records of training conducted with Booderee Board of Management members since 2014.

Are the Director of National Parks’ operational activities underpinned by relevant and complete procedural guidance?

The Director’s operational activities are not underpinned by relevant and complete procedural guidance. The lack of appropriate guidance in key areas of corporate support and operational delivery, including asset management and compliance activities, limits the extent to which these activities are delivered appropriately and consistently across the national parks.

Procedural guidance

3.26 The central office in Canberra develops and oversees procedural guidance regarding enterprise-wide corporate support functions such as risk management, procurement, workforce capability management, asset management and compliance and enforcement. Guidance on key operational activities including natural resource and cultural heritage management and visitor services is to be maintained by park managers.

3.27 For the jointly managed parks, policies and procedures are to be provided to the board of management for review prior to coming into effect. The Director does not maintain a consolidated list of all policies, standard operating procedures and guidance. The Director informed the ANAO that park and central office managers are responsible for ensuring that procedural guidance is relevant and complete.

3.28 The ANAO reviewed whether relevant and complete procedural guidance and appropriate business management systems had been maintained in relation to key areas of corporate support and operational activities — procurement, asset management, compliance and enforcement, natural resource and cultural heritage management, and visitor services (Table 3.1).53

Table 3.1: Summary of ANAO review of procedural guidance and supporting systems

|

Activity |

ANAO comments |

|

Procurement |

Previous reviews (see Table 4.2) noted substantial weaknesses in procedural guidance and controls to support procurement in relation to:

The Director’s Chief Financial Officer reported 20 procurement breaches in the first four months of 2018–19. During the course of this audit, the Director issued revised procurement and contracting procedural guidance. |

|

Asset management |