Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Commonwealth Fisheries

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- To provide assurance to Parliament on the ongoing effectiveness of AFMA’s management of Commonwealth fisheries.

Key facts

- The Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) was established as a statutory authority in 1992.

- AFMA is involved in the management of 16 fisheries located between three and 200 nautical miles from the Australian coast.

- AFMA is solely responsible for the management of nine fisheries.

- Seven fisheries are managed jointly by AFMA and regional or international partners.

What did we find?

- AFMA’s governance arrangements are partly appropriate.

- AFMA’s management of individual fisheries is partly effective.

- AFMA’s compliance and enforcement processes are largely effective.

- AFMA’s overall management of Commonwealth fisheries is partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made nine recommendations to the Australian Fisheries Management Authority to:

- improve performance information;

- develop a schedule for ecological risk assessments;

- determine its approach to managing economic risk;

- update harvest strategies and bycatch and discard plans;

- actively engage with all relevant stakeholders;

- improve staff conflict of interest records;

- publish pricing data; and

- improve guidance for compliance staff.

- AFMA agreed to all recommendations.

$437 million

Commonwealth fisheries gross value of production in 2018–19

8 million km²

Area of the Australian fishing zone

3700

Known species of fish in the Australian fishing zone

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Government is involved in the management of 16 fisheries located between three and 200 nautical miles from the Australian coast. Nine fisheries are managed solely by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) on behalf of the Australian Government. Seven fisheries are managed jointly by AFMA and regional or international partners.

Table S.1. Commonwealth fisheries management arrangements

|

|

Fishery name |

Management arrangements |

|

1 |

Bass Straight Central Zone Scallop |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

2 |

Coral Sea |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

3 |

Northern Prawn |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

4 |

North West Slope Trawl |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

5 |

Western Deepwater Trawl |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

6 |

Small Pelagic |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

7 |

Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

8 |

Southern Squid Jig |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

9 |

Macquarie Island Toothfish |

Managed solely by AFMA |

|

10 |

Eastern Tuna and Billfish |

Jointly managed — Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission |

|

11 |

Southern Bluefin Tuna |

Jointly managed — Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna |

|

12 |

Western Tuna and Billfish |

Jointly managed — Indian Ocean Tuna Commission |

|

13 |

Heard Island and McDonald Islands |

Jointly managed — Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources |

|

14 |

Skipjack Tuna (non-operational)a |

Jointly managed — international partners |

|

15 |

Norfolk Island (non-operational) |

Jointly Managed — Norfolk Island Regional Council |

|

16 |

South Tasman Rise (non-operational) |

Jointly Managed — New Zealand |

Note a: Non-operational fisheries are those considered by AFMA to be subject to little or no commercial fishing activity due to fishery closure or economic reasons.

Source: ANAO analysis of AFMA documentation.

2. AFMA was established as a statutory authority in 1992 by the Fisheries Administration Act 1991 (Fisheries Administration Act) to manage Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries and apply the provisions of the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Fisheries Management Act). AFMA is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), forming part of the Agriculture, Water and the Environment portfolio.

3. The AFMA Commission (the Commission) is responsible for performing and exercising the domestic fisheries management functions and powers of AFMA. The Commission comprises seven commissioners, including the Chair, Deputy Chair and the AFMA Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The CEO assists the Commission and gives effect to its decisions.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. AFMA’s legislated functions and objectives require the pursuit of efficient and cost effective fisheries management, balancing the principles of ecologically sustainable development with maximising net economic returns. Changing environmental conditions and fishing methods can affect fish stocks and the broader environment. This audit will provide assurance to Parliament on the ongoing effectiveness of AFMA’s management of Commonwealth fisheries including through the COVID-19 pandemic and in planning for the future.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of AFMA’s management of Commonwealth fisheries.

6. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Have appropriate governance arrangements been established to inform planning and management?

- Are individual fisheries management arrangements effective?

- Have effective compliance and enforcement processes been implemented?

7. This audit focussed on fisheries management arrangements and domestic compliance. The ANAO did not examine:

- compliance monitoring arrangements for international fisheries and international partnership arrangements;

- enterprise-wide risk management; or

- AFMA’s management of Torres Strait fisheries under the Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984.

Conclusion

8. AFMA’s overall management of Commonwealth fisheries is partly effective.

9. AFMA’s governance arrangements, including performance information, are partly appropriate. Performance measures contained in AFMA’s corporate plan do not provide a clear assessment against its purpose and incorrect reporting has been identified. An ecological risk assessment framework has been established but re-assessments have not been completed in accordance with the framework. AFMA has not pursued a proposal to establish an economic risk assessment framework. An appropriate risk-based compliance and enforcement framework to promote compliance with fisheries management regulations has been established.

10. Individual fisheries management arrangements are partly effective. Plans and strategies implemented under Commonwealth policy have not been reviewed in a timely manner. Maximising net economic returns based on scientific modelling has not progressed. Conflict of interest arrangements for commissioners and committees are managed appropriately although administration of staff conflict of interest declarations is not effective. Public reporting on key commercial fish stock is extensive. Aggregate pricing data collected from industry is not being reported.

11. AFMA has implemented largely effective compliance and enforcement processes. Compliance activities are informed by a structured risk assessment process. Detection, prevention and enforcement activities are largely effective. Guidance material and reporting could be improved.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

12. AFMA’s administrative arrangements are largely appropriate. AFMA’s establishment aligns with the requirements of the Fisheries Administration Act 1991. Collectively, performance measures contained in AFMA’s corporate plan do not enable a clear assessment of AFMA’s effectiveness in achieving its purpose. AFMA has incorrectly reported results in its performance statements over the past four financial years.

13. It is unclear whether AFMA’s ecological risk framework is appropriate. AFMA has documented its ecological risk management framework in the 2017 Guide to AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management. AFMA has not met its requirement to re-assess ecological risk every five years. A plan to implement fishery management strategies, which incorporate ecological risk management and are subject to a five-year review period, has not been implemented.

14. AFMA has not established a framework for economic risk assessments. A proposal to develop an economic risk assessment framework as part of a coordinated approach to managing economic issues across fisheries has not been implemented.

15. AFMA has established an appropriate risk-based compliance framework. The framework includes appropriate policy, risk management procedures, implementation activities and reporting.

Individual fisheries management arrangements

16. Plans and strategies have not been reviewed in accordance with the relevant Commonwealth legislation and policy. Stakeholder engagement with recreational and Indigenous fishing stakeholders has been limited.

17. AFMA seeks to meet the requirement to maximise net economic returns by pursuing maximum economic yield for individual fisheries. Mechanisms to maximise economic yield are not mature and progress towards establishing maximum economic yield targets for individual fisheries has been slow.

18. AFMA has established policies and processes to manage conflicts of interest for commissioners, committees and staff. Appropriate arrangements for managing conflicts of interest for commissioners and committees have been implemented. Administration of conflicts of interest declared by staff members is not effective.

19. Extensive public reporting on the status of fish stock is provided in the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) annual fisheries report and AFMA’s annual report. Detailed information on selected stock is available on AFMA’s website. Pricing information on quota, lease and statutory fishing rights is not available.

Compliance and enforcement processes

20. AFMA has established appropriate risk based compliance priorities and plans. Risks are identified and monitored through biennial risk assessments and ongoing analysis. Compliance plans and programs are aligned with identified risks.

21. AFMA has implemented effective arrangements for detecting and preventing non-compliance. The majority of operators are found to be compliant with their obligations. AFMA has improved its capability to detect non-compliance by implementing electronic monitoring.

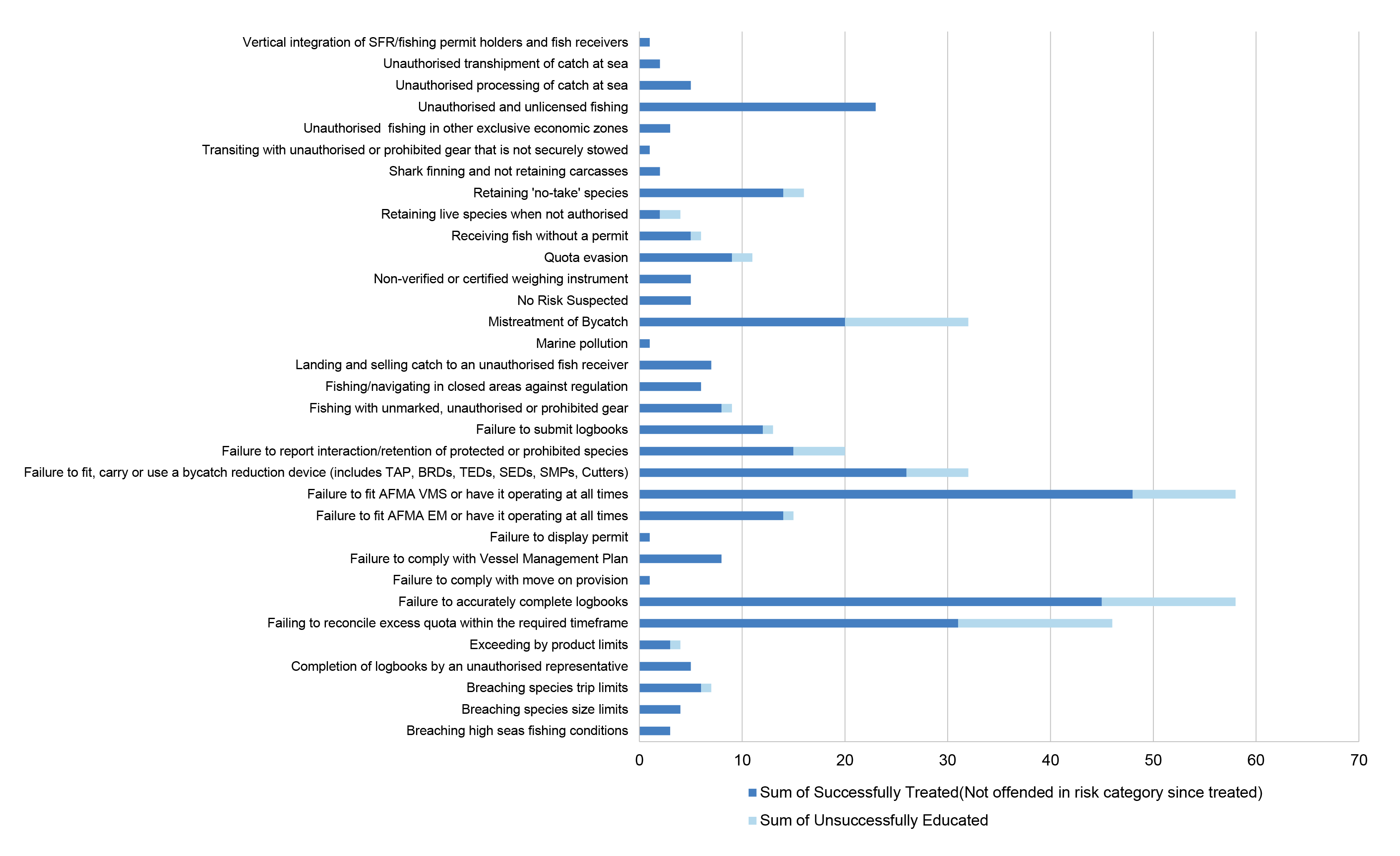

22. Enforcement actions to address non-compliance are largely effective. A small proportion of operators are responsible for a large proportion of non-compliance. Guidance for escalating the enforcement response for quota reconciliation repeat offenders could be improved. AFMA has committed to improving its management of the prosecution process.

23. Reporting on compliance and enforcement processes is largely appropriate. AFMA could improve reporting on quota evasions, bycatch mishandling and repeat offences.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.24

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority revise its performance information to:

- ensure the purpose statement wholly incorporates legislated objectives;

- align key activities with the purpose; and

- include measures and targets that meet the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014, section 16EA.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.49

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority document a re-assessment plan and schedule for ecological risk assessments and report progress towards implementation of the schedule to the Commission.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.60

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority work with its economic working group and research committee to determine AFMA’s approach to managing economic risk.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.10

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority ensure harvest strategies and bycatch and discard plans meet the relevant Commonwealth policy and are available on its website.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.32

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority maintain a current register of interested parties and actively engage with all relevant stakeholders in relation to fisheries management arrangements.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.60

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority ensure conflict of interest and outside employment records for all staff are current, consistently recorded, accessible and approved where appropriate.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.72

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority resolve data quality issues with regard to quota transactions and publish pricing data.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.28

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority update the workflow contained in the quota reconciliation enforcement matrix to include detailed guidance on handling repeat offences.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 4.39

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority ensure staff are aware of their legislated obligations when conducting investigations and address identified capability gaps in a timely manner.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

Summary of Australian Fisheries Management Authority response

AFMA has extensive responsibilities in managing Commonwealth fisheries resources.

As identified by the ANAO audit, AFMA’s overall management is delivering positive outcomes. There are opportunities for improvements and AFMA agrees with all nine recommendations by the ANAO.

Action on these recommendations should improve AFMA’s assessment of its performance, currency of management strategies, delivery of compliance, and engagement and accountability with stakeholders. AFMA notes that, in seeking to progress these elements, the agency will need to balance competing needs and the availability of limited resources in and across fisheries.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Records management

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australia’s fishing zone covers over eight million square kilometres, making it the world’s third largest. It contains around 3700 known species of fish, over 2800 species of mollusc and over 2300 species of crustaceans. Only a small proportion of these species are commercially fished.

1.2 The Australian Government generally manages fisheries in waters between three and 200 nautical miles from the Australian coast. This area is referred to as the Australian Fishing Zone. State and territory entities typically manage fisheries out to three nautical miles from the coastline.

Figure 1.1: Australian fishing zone — Commonwealth fishery locations

Note: More detailed, individual fishery maps are included at Appendix 2.

Source: AFMA.

1.3 Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries generated $437 million in gross value of production in 2018–19.1 This represents 24 per cent of the $1.79 billion value of Australia’s total wild-capture fisheries.2 The majority of Australia’s commercial fishing activity occurs within state and territory managed fisheries.

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority

1.4 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) was established as a statutory authority in 1992 by the Fisheries Administration Act 1991 (Fisheries Administration Act) to manage Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries and apply the provisions of the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Fisheries Management Act).

1.5 Collectively, the Fisheries Administration Act and the Fisheries Management Act include 11 objectives that AFMA is required to pursue or take into account (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: AFMA’s legislated obligations

|

Act and section |

Summary of objectivea |

|

Fisheries Administration Act, section 6 Fisheries Management Act, section 3 |

Implement efficient and cost-effective fisheries management. |

|

Ensure the exploitation of fisheries and related activities is consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development.b |

|

|

Where Australia has obligations under international agreements, ensure the exploitation of fish stocks and related activities in the Australian fishing zone and the high seas are carried on consistently with those obligations. |

|

|

To the extent that Australia has obligations under international law or agreements, ensure that fishing activities by Australian flagged vessels on the high seas are conducted consistently with those obligations.c |

|

|

Maximise net economic returns to the Australian community from the management of Australian fisheries. |

|

|

Ensure accountability to the fishing industry and the Australian community in the management of fisheries resources. |

|

|

Achieve government targets in relation to the recovery of AFMA’s costs. |

|

|

Ensure that the interests of commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishers are taken into account. |

|

|

Fisheries Management Act, section 3 |

Ensure, through proper conservation and management measures, that the living resources of the Australian fishing zone are not endangered by over-exploitation. |

|

Achieve optimum utilisation of the living resources of the Australian fishing zone. |

|

|

Ensure, as far as practicable, that measures adopted in pursuit of legislated objectives must not be inconsistent with the preservation, conservation and protection of whales. |

|

Note a: Objectives that AFMA must pursue are shaded blue. Objectives that AFMA must have regard to are unshaded.

Note b: The principles of ecologically sustainable development as defined in the Fisheries Management Act are:

- decision-making processes should effectively integrate both long-term and short-term economic, environmental, social and equity considerations;

- if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

- the principle of inter-generational equity—that the present generation should ensure that the health, diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations;

- the conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity should be a fundamental consideration in decision-making; and

- improved valuation, pricing and incentive mechanisms should be promoted.

Note c: This objective is listed as one that AFMA must pursue in the Fisheries Administration Act and as one that AFMA is to have regard to in the Fisheries Management Act.

Source: The Fisheries Administration Act and the Fisheries Management Act.

1.6 AFMA is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), forming part of the Agriculture, Water and the Environment portfolio. AFMA comprises the AFMA Commission (the Commission), the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), and staff members.

1.7 The Commission comprises seven commissioners, including the Chair, Deputy Chair and the AFMA CEO. It is responsible for performing and exercising the domestic fisheries management functions and powers of AFMA. The Commission is also supported by AFMA management and a range of internal and external committees that provide information and advice on various aspects of fisheries management.

1.8 The CEO is AFMA’s accountable authority. The CEO assists the Commission and gives effect to its decisions. The CEO is also responsible for performing foreign compliance functions and managing services to joint authorities of the Commonwealth and state and territory governments, including the Torres Strait. The CEO is not subject to direction by the Commission in relation to the functions and powers exercised under the PGPA Act, or in relation to foreign compliance.

1.9 AFMA is solely responsible for managing nine fisheries on behalf of the Australian Government. In addition, AFMA has developed a statutory Management Plan under section 17 of the Fisheries Management Act for four fisheries that are subject to joint management arrangements. Each of these fisheries are managed by an intergovernmental commission, of which Australia is a member. A further three jointly managed fisheries are non-operational (see Table S.1).

Fisheries management

1.10 The Fisheries Management Act provides the legislative basis for management of Commonwealth fisheries including the regulation of commercial fishing. AFMA manages fisheries by imposing regulations on the amount of fish that can be caught in a particular area and what type of equipment can be used. It does this by allocating tradable fishing concessions that specify fishing conditions for each concession holder and by monitoring compliance with those conditions. The main type of concessions in Commonwealth fisheries are statutory fishing rights, which are granted under section 31 of the Fisheries Management Act.

1.11 The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy, 2018 (Harvest Strategy Policy) provides a framework for applying an evidence-based approach to setting harvest levels. It defines biological and economic objectives for Commonwealth fisheries and identifies reference points to be used in individual harvest strategies. The Harvest Strategy Policy and the Commonwealth Fisheries Bycatch Policy, 2018, provide a basis for managing Commonwealth fisheries.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.12 AFMA’s legislated functions and objectives require the pursuit of efficient and cost-effective fisheries management, balancing the principles of ecologically sustainable development with maximising net economic returns. Changing environmental conditions and fishing methods can affect fish stocks and the broader environment. This audit will provide assurance to Parliament on the ongoing effectiveness of AFMA’s management of Commonwealth fisheries including through the COVID-19 pandemic and in planning for the future.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.13 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of AFMA’s management of Commonwealth fisheries.

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Have appropriate governance arrangements been established to inform planning and management?

- Are individual fisheries management arrangements effective?

- Have effective compliance and enforcement processes been implemented?

1.15 This audit focussed on fisheries management arrangements and domestic compliance. The ANAO did not examine:

- compliance monitoring arrangements for international fisheries and international partnership arrangements;

- enterprise-wide risk management; or

- AFMA’s management of Torres Strait fisheries under the Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984.

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit methodology included:

- examination of plans, strategies, policies and processes relating to AFMA’s responsibilities for managing Commonwealth fisheries;

- analysis of licencing, quota and compliance data; and

- interviews with relevant AFMA staff and its internal and external stakeholders.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $430,282.

1.18 The team members for this audit were Jennifer Myles, Chirag Pathak, Aden Pulford and Michael White.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the arrangements governing the Australian Fisheries Management Authority’s (AFMA) administration, ecological and economic risk assessment and compliance frameworks.

Conclusion

AFMA’s governance arrangements, including performance information, are partly appropriate. Performance measures contained in AFMA’s corporate plan do not provide a clear assessment against its purpose and incorrect reporting has been identified. An ecological risk assessment framework has been established but re-assessments have not been completed in accordance with the framework. AFMA has not pursued a proposal to establish an economic risk assessment framework. An appropriate risk-based compliance and enforcement framework to promote compliance with fisheries management regulations has been established.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving performance information, establishing a re-assessment schedule for ecological risk assessments and determining an approach to managing economic risk.

2.1 Sound governance arrangements support consistent and objective decision-making and accountability of entities for achieving their objectives. To determine whether it has established appropriate governance arrangements, the ANAO examined whether AFMA has established appropriate:

- administrative arrangements, including performance measurement and reporting;

- ecological risk assessment frameworks;

- economic risk assessment frameworks; and

- compliance frameworks.

Have appropriate administrative arrangements been established?

AFMA’s administrative arrangements are largely appropriate. AFMA’s establishment aligns with the requirements of the Fisheries Administration Act 1991. Collectively, performance measures contained in AFMA’s corporate plan do not enable a clear assessment of AFMA’s effectiveness in achieving its purpose. AFMA has incorrectly reported results in its performance statements over the past four financial years.

2.2 The Fisheries Administration Act 1991 (Fisheries Administration Act) and the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Fisheries Management Act) provide for the establishment of AFMA, include AFMA’s objectives, and define its functions, powers and operations.

2.3 Performance statements requirements are set out in the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule). Under the PGPA Act, the purposes of a Commonwealth entity include the objectives, functions or role of the entity. Entities should also consider existing authoritative documents when defining their purposes, such as enabling legislation as passed by the Parliament.

AFMA’s establishment

2.4 AFMA comprises the AFMA Commission (the Commission), the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), and 152 staff (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: AFMA’s organisational structure as at 30 June 2020

|

Chief Executive Officer |

||

|

Fisheries Management Branch |

Corporate Services Branch |

Fisheries Operations Branch |

|

Executive Manager |

Chief Operating Officer |

General Manager |

|

Senior Manager Demersal & Midwater |

Senior Manager People, Capability & Engagement |

Senior Manager Compliance Operations |

|

Senior Manager Policy, Environment, Economics, Research |

Chief Finance Officer |

Senior Manager National Compliance Strategy |

|

Senior Manager Tuna & International Fisheries |

Senior Manager Legal & Parliamentary Services |

Senior Manager Foreign Compliance |

|

Senior Manager Northern Fisheries |

Senior Manager Business Operational Support |

|

|

Senior Manager Fisheries Services |

||

|

Manager Torres Strait Fisheries |

||

Source: AFMA Annual Report 2019–20.

The Commission

2.5 The Commission is established under section 10B of the Fisheries Administration Act. It is responsible for performing and exercising the domestic fisheries management functions and powers of AFMA.3

2.6 The Fisheries Administration Act requires that commissioners have a high level of expertise in one or more selected areas, and must not hold certain positions which may cause a real or perceived conflict of interest.4

2.7 The Commission meets approximately five times per year to consider a range of information and advice provided by AFMA management and various committees. A summary of the meeting is published on AFMA’s public website.

2.8 Commissioners’ stated skills and expertise cover public sector governance, business, fisheries management, financial management, science, economics and law. This meets the requirement to ensure that the commissioners collectively possess expertise in all relevant areas.

2.9 All commissioners have in place a conflict of interest declaration, reporting that they do not have any interests named in paragraph 12(3)(b) of the Fisheries Administration Act. Further details on the commissioners’ declarations is included at paragraphs 3.49 to 3.52.

The Chief Executive Officer

2.10 The CEO is AFMA’s accountable authority.5 The CEO is responsible for performing and exercising the foreign compliance functions and powers of AFMA, assisting the Commission and giving effect to its decisions.6

2.11 The CEO is appointed by the Minister as a full-time commissioner. In addition to the conflict of interest requirements imposed on commissioners, the Act requires that the CEO not engage in paid employment outside AFMA without the Minister’s approval. Further details regarding the CEO’s conflict of interest declarations and approvals is included at paragraphs 3.49 to 3.52.

Committees

2.12 Under section 54 of the Fisheries Administration Act, AFMA may establish committees to assist it in the performance of its functions and the exercise of its powers. AFMA’s primary advisory bodies are the Management Advisory Committees (MACs), the Resource Assessment Groups (RAGs) and the AFMA Research Committee (ARC).

Management Advisory Committees

2.13 MACs are statutory committees established under section 56 of the Fisheries Administration Act, with functions determined by AFMA. There are seven MACs covering 10 of the 13 operational fisheries listed at Table S.1.7 MACs provide advice to AFMA on fisheries management and operations, and report on the status of fish stocks and the impact of fishing on the marine environment. Members are appointed by the Commission and come from industry, policy, conservation, state and territory governments, recreational and research fields.

Resource Assessment Groups

2.14 RAGs are non-statutory bodies established to provide scientific advice to the Commission, AFMA management and the relevant MACs, on the biological, economic and wider ecological factors relevant to a fishery or a particular species. There are 10 RAGs covering 10 of the 13 operational fisheries listed at Table S.1.8 Members are appointed by the CEO following a public expression of interest process and include fishery scientists, industry members, fishery economists, AFMA management and other interest groups.

AFMA Research Committee

2.15 The AFMA Research Committee, in conjunction with the MACs and RAGs, develops research priorities and the five-year strategic research plan. It also reviews fishery research plans and assesses research project outcomes. The research committee comprises five members drawn from AFMA’s Commission and executive management.

Performance information

2.16 The Commonwealth Performance Framework is established by the PGPA Act. It requires Commonwealth entities to measure and report the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes.

2.17 Following a 2019 internal audit of the performance statements and a 2020 internal evaluation of the performance measures, AFMA revised the format of its 2020–21 Corporate Plan, its stated purpose and the associated performance measures and targets.

AFMA’s purpose statement

2.18 Subsection 16E(2) of the PGPA Rule requires entities to include the purposes of the entity in their corporate plan. The purposes of an entity include the objectives, functions or role of the entity. A clear and concise statement of the purposes of an entity underpins a robust performance reporting framework.9 AFMA’s purpose is stated in its corporate plan:

AFMA’s purpose is to pursue the ecologically sustainable development (ESD) of Commonwealth fisheries for the benefit of the Australian community. This purpose will be pursued through understanding and monitoring Australia’s marine living resources and regulating and monitoring commercial fishing, including domestic licensing and deterrence of illegal foreign fishing. As part of our application of ESD, AFMA is also increasing consideration of the interests of recreational and Indigenous stakeholders.

AFMA’s legislated functions and objectives require the pursuit of efficient and cost effective fisheries management consistent with the principles of ESD, including the precautionary principle, and maximising the net economic returns to the Australian community from the management of Commonwealth fisheries. Over the next four years, AFMA will implement fisheries management in pursuit of sustainable and profitable fisheries by:

- simplifying regulations to reduce operational and cost burdens for industry;

- assessing and mitigating ecological and compliance risks;

- deterring illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; and

- extending communication and improving engagement with stakeholders on the benefits of responsible management of fisheries and better align expectations.

AFMA commissions and places a high importance on scientific and economic research and risk assessments. This reflects the importance of making evidence-based decisions. Getting value for money from all of this work remains a key AFMA commitment.10

2.19 AFMA’s purpose statement includes a mix of objectives, activities and miscellaneous commentary, which reduces its clarity. The purpose statement addresses eight of AFMA’s 11 legislated objectives.11 It does not address objectives relating to accountability, cost recovery and protection of whales.

2.20 One objective relating to accountability is addressed as part of AFMA’s corporate goals. Two legislated objectives relating to cost recovery and protection of whales are not explicitly addressed in either the purpose statement or the corporate goals.

AFMA’s activities

2.21 Subsection 16E(2) of the PGPA Rule requires entities to identify the key activities the entity will undertake during the period to achieve its purposes.12 AFMA has described activities that support achievement of their purpose in several sections of the corporate plan. These activities address 10 of AFMA’s 11 legislated objectives. The corporate plan does not include activities relating to the preservation of whales.

AFMA’s performance measures

2.22 AFMA’s corporate plan includes four corporate goals, which address eight of AFMA’s legislated objectives. AFMA has developed eight measures against its corporate goals. The ANAO assessed seven of these measures, which relate to the scope of the audit, and found that four measures facilitate an outcome assessment against the relevant corporate goal (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: AFMA’s corporate goals and performance measures 2020–21

|

Corporate goal |

Measure |

Does the measure facilitate performance assessment against the corporate goal? |

|

Management of Commonwealth fisheries consistent with principles of ecological sustainable development. |

Decision-making by the Commission and Management is consistent with legislative objectives and overarching policy settings. |

No. Reflects activities and relates to compliance with legislation and policy. |

|

Maximise net economic returns to the Australian community from the management of Commonwealth fisheries. |

Fishery maximum economic yield (MEY) targets are consistent with the objectives of the Fisheries Management Act and Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy and Guidelines. |

Yes, when taken in conjunction with targets. |

|

Compliance with Commonwealth fisheries laws and policies and relevant international fishing obligations and standards. |

Governance arrangements for domestic compliance program in place and remain relevant. |

No. Refers to an internal process. |

|

Effective risk-based domestic compliance programs in place. |

Yes. Compliance programs provide a basis for a proxy for the sustainability of fisheries in relation to set targets. |

|

|

To deter illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing by foreign fishing vessels in Australian waters. |

Not assessed.a |

|

|

Deliver efficient, cost-effective and accountable management of Commonwealth fisheries resources. |

To ensure AFMA’s cost recovery framework is efficient and effective, transparent and accountable, taking into consideration stakeholder feedback. |

Yes. Relates to outcomes and stakeholder feedback and provides a proxy for efficient and effective management. |

|

Yes. Stakeholder feedback provides a proxy for efficient and effective management. |

|

|

No. Refers to management activity. |

|

Note a: The audit did not assess compliance monitoring arrangements for international fisheries.

Source: ANAO analysis of AFMA’s 2020–21 corporate plan.

2.23 Overall, performance information presented in AFMA’s corporate plan does not address the totality of its legislated objectives. There is no clear line of sight from the legislated objectives through purposes to stated activities and measures. Improvements are required to provide the Parliament and the public with useful information in relation to AFMA’s performance against its legislated objectives.

Recommendation no.1

2.24 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority revise its performance information to:

- ensure the purpose statement wholly incorporates legislated objectives;

- align key activities with the purpose; and

- include measures and targets that meet the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014, section 16EA.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

2.25 AFMA appreciates the input/suggestions from ANAO to modify and develop our planning and reporting documentation. AFMA has already revised our performance information in the Portfolio Budget Statement, and in our draft Corporate Plan 2021-2024 (due to be submitted to the Minister in late May 2021) to provide a clear line of sight to our goals and to ensure that this information is useful to the Parliament and public in relation to our performance.

2.26 However, our approach to planning and reporting will continue to reflect the distinction between two sets of Objectives in our legislation – some that “must be pursued” by AFMA, and others that AFMA is to “have regard to”. This is an important difference in terms of the weight placed on those respective objectives by the legislation, meaning they will not necessarily be dealt with equally in our performance planning and reporting.

2.27 AFMA does not agree that we have an overt Objective related to the protection of whales. Rather, there is an underpinning requirement that as we undertake activities relevant to the second set of Objectives, we must ensure that they are not inconsistent with the preservation, conservation and protection of whales. As such, AFMA will not have specific Goals, Objectives, Key Activities or Performance Measures directed to this issue.

ANAO comment on the Australian Fisheries Management Authority’s response

2.28 As noted in Table 1.1 of this report, subsection 3 (2) of the Fisheries Management Act lists objectives that the Minister, AFMA and Joint Authorities are to have regard to. It further states that those entities:

…must ensure, as far as practicable, that measures adopted in pursuit of those objectives must not be inconsistent with the preservation, conservation and protection of all species of whales.

Performance statements reporting

2.29 In August 2019, an internal audit found that AFMA’s performance statements largely complied with relevant legislation, were clearly categorised, regularly monitored and reviewed by the Audit and Risk Committee.

2.30 The 2019 internal audit also found that AFMA had incorrectly reported against three of 10 key performance indicators in its 2016–17 and 2017–18 annual reports. The errors related to the number of economically significant stocks being on target, the number of stocks heading towards their target reference point and the number of red tape reduction initiatives completed.

2.31 On 23 October 2020, AFMA informed the ANAO that, following the 2019 internal audit, internal measures were implemented to ensure accurate reporting for future performance statements. Paragraph 17AH(1)(e) of the PGPA Rule requires correction of material errors in the subsequent annual report. AFMA has not taken action to correct the errors identified in the August 2019 internal audit.

2.32 In addition to the errors identified in the August 2019 internal audit, the ANAO found that AFMA incorrectly reported against performance criteria 1.1 in its 2018–19 and 2019–20 annual reports as described below.

2.33 In 2018–19, AFMA reported it had partly met its target to complete five ecological risk assessments and five fishery management strategies.13 In 2019–20, AFMA reported it had completed six ecological risk assessments and six fisheries management strategies. In the years 2018–19 and 2019–20, AFMA completed one ecological risk assessment and did not complete any fishery management strategies.14

2.34 AFMA has undertaken to correct the errors identified in its 2016–17 to 2019–20 performance statements in its 2020–21 annual report.

Regulator performance framework

2.35 The Regulatory Performance Framework includes six key performance indicators against which regulators are required to report their performance:

- regulators do not unnecessarily impede the efficient operation of regulated entities;

- communication with regulated entities is clear, targeted and effective;

- actions undertaken by regulators are proportionate to the risk being managed;

- compliance and monitoring approaches are streamlined and coordinated;

- regulators are open and transparent in their dealings with regulated entities; and

- regulators actively contribute to the continuous improvement of regulatory frameworks.

2.36 AFMA conducts an annual self-assessment of the following core regulatory functions as required by the Regulator Performance Framework:

- developing fishery management policies, regulations and other arrangements for Commonwealth fisheries;

- licensing fishing operators in Commonwealth fisheries;

- monitoring, control and surveillance of Commonwealth domestic fishery operators;

- the detection and prosecution of illegal foreign fishers;

- engaging with stakeholders on the responsible management of fisheries; and

- promoting compliance with Australian fishing laws and relevant international fishing obligations and standards through education and enforcement operations.

2.37 In 2019–20, AFMA reported that its core regulatory functions had met the framework’s six key performance indicators.

Stakeholder engagement

2.38 The management of Commonwealth fisheries is of interest to a wide range of stakeholders including commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishers, researchers, environmental organisations, state and territory governments and the general public. The Fisheries Management Act states that AFMA must have regard to the objective of ensuring that the interests of commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishers are taken into account.15

2.39 AFMA’s stakeholder engagement is focussed on industry participants, which are well represented in AFMA’s primary advisory groups — the MACs and RAGs (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: MAC and RAG representation

|

Advisory group |

Number of representatives per interest group across all MACs and RAGs |

||||||||

|

|

Industry |

Science |

Research |

Economic |

Recreational |

Government |

Environment conservation |

Indigenous |

|

|

MACs |

27 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

0 |

|

|

RAGs |

21 |

18 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of AFMA’s advisory group representatives.

2.40 AFMA’s stated purpose includes increasing consideration of the interests of recreational and Indigenous stakeholders. AFMA’s corporate plan makes several references to improving engagement with, and accountability to recreational and Indigenous fishers. However, it does not include any activities or performance measures that support achievement and reporting of this.

2.41 In 2020, AFMA developed a draft Stakeholder Engagement Framework 2020–2024 and a draft Communication Plan 2020–2022. These documents identify stakeholder groups and outline general principles of engagement. They do not include specific activities to be undertaken to increase consideration of the interests of recreational and Indigenous stakeholders.

2.42 In February 2021, AFMA informed the ANAO that an implementation strategy for stakeholder engagement is expected to be completed by 30 June 2021.

Has an appropriate framework for ecological risk assessments been established?

It is unclear whether AFMA’s ecological risk framework is appropriate. AFMA has documented its ecological risk management framework in the 2017 Guide to AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management. AFMA has not met its requirement to re-assess ecological risk every five years. A plan to implement fishery management strategies, which incorporate ecological risk management and are subject to a five-year review period, has not been implemented.

2.43 Ecological risk management (ERM) is essential to ensure Commonwealth fisheries management arrangements are consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development. Framework design should consider available resources and the feasibility of implementation.

Fishery management strategies

2.44 The 2017 Guide to AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management provides an overview of AFMA’s ERM. A key element of AFMA’s ERM is the development of fishery management strategies, which are intended to:

- outline management approaches required in each fishery to achieve its objectives and meet ecological sustainability requirements;

- integrate harvest strategies, ERM strategies, bycatch work plans, data plans and research strategies;

- include performance indicators and annual reporting;

- be developed and implemented in association with ecological risk re-assessments; and

- document management responses to ecological risk assessments.

2.45 AFMA planned to develop fishery management strategies for the 13 operational fisheries listed at Table S.1 by 2020. As at 18 January 2021, one fishery management strategy has been developed, which was for the Eastern Tuna and Billfish fishery.

Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing

2.46 The primary methodology underpinning AFMA’s ERM is a risk assessment process referred to as the Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing (ERAEF).16 The ERAEF methodology considers the impacts of fishing on commercial species, by-product species17, bycatch species18, protected species, and habitats and communities.19 The ERAEF process identifies and quantifies risks to ecological sustainability.

2.47 An ERAEF has been conducted for the 13 operational fisheries listed at Table S.1.20 Table 2.4 shows the ERAEF dates.

Table 2.4: Ecological risk assessments for Commonwealth fisheries

|

|

Fishery name (excluding non-operational) |

Latest ERAEF date (sub-fishery) |

|

1 |

Bass Strait Central Zone Scallop |

2007 |

|

2 |

Coral Sea |

2007 (8 sub-fisheries) |

|

3 |

Northern Prawn |

2007 |

|

4 |

North West Slope Trawl |

2007 |

|

5 |

Western Deepwater Trawl |

2007 |

|

6 |

Small Pelagic |

2017 (Midwater trawl sub-fishery) 2007 (Purse Seine sub-fishery) 2007 (Midwater trawl sub-fishery) |

|

7 |

Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark |

2019 (Commonwealth trawl sector, Danish seine sub-fishery) 2019 (Great Australian Bight sector, otter trawl sub-fishery) 2019 (gillnet hook and trap sector, shark gillnet sub-fishery) 2019 (Commonwealth trawl sector, otter trawl sub-fishery) |

|

8 |

Southern Squid Jig |

2007 |

|

9 |

Macquarie Island Toothfish |

2007 |

|

10 |

Eastern Tuna and Billfish |

2019 (Longline sub-fishery) |

|

11 |

Southern Bluefin Tuna |

2020 (purse seine sub-fishery) |

|

12 |

Western Tuna and Billfish |

2010 |

|

13 |

Heard Island and McDonald Islands |

2018 (Midwater trawl sub-fishery) 2018 (Demersal Longline sub-fishery) 2018 (Demersal Trawl sub-fishery) |

Source: ANAO analysis of AFMA records.

2.48 The 2017 Guide to AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management states that fishery re-assessments under the ERAEF will be undertaken every five years. It includes a schedule for re-assessments indicating all fisheries were to commence re-assessment by 2020. Since 2017 re-assessments for five fisheries have been conducted. As at 11 February 2021, AFMA was considering changes to its ecological risk assessment framework, including revised re-assessment dates.

Recommendation no.2

2.49 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority document a re-assessment plan and schedule for ecological risk assessments and report progress towards implementation of the schedule to the Commission.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

2.50 AFMA is actively considering significant changes to its ecological risk assessment (ERA) framework. AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management Working Group is developing a proposal to move towards a more automated and cost effective/ongoing ERA process that includes routine updating as methodology improves. A new reassessment plan and approach that is sensitive to resource constraints and competing priorities will be considered by the AFMA Commission.

Assessments under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

2.51 An assessment of all export and all Australian Government-managed fisheries is required under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). These assessments are conducted by the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment against the Commonwealth Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries21 to evaluate the ecological sustainability of fishery management arrangements.22

2.52 All nine Commonwealth fisheries managed solely by AFMA were assessed under the EPBC Act between 2016 and 2020. Six assessments refer to the need for Ecological Risk Assessment re-assessments, either in the comments, conditions or recommendations section. One assessment refers to the expectation that a fisheries management strategy will be developed, and four refer to expected updated bycatch and discard work plans.23 None of these documents have been updated since the EPBC Act assessments.

Has an appropriate framework for economic risk assessments been established?

AFMA has not established a framework for economic risk assessments. A proposal to develop an economic risk assessment framework as part of a coordinated approach to managing economic issues across fisheries has not been implemented.

2.53 Under the Fisheries Management Act and Fisheries Administration Act, AFMA is charged with maximising the net economic return to the Australian community from the management of Australian fisheries. Assessment of economic risks supports this outcome.

2.54 AFMA’s Economic Working Group (EWG) was formally established in 2017. It meets annually to provide strategic advice to the Commission, MACs and RAGs on fisheries economic matters. It comprises an AFMA staff member, RAG economic members24, and both a recreational and a commercial fishing representative. The group is intended to support AFMA in meeting its legislative objectives, in particular, maximising net economic returns to the Australian community.

2.55 At the EWG’s September 2017 meeting, AFMA agreed an action to commence scoping and developing a project proposal for an economic risk assessment during 2017–18 and 2018–19.

2.56 The AFMA Strategic Research Plan 2017–2022 includes Research Strategy 2c—Develop a coordinated approach on major fishery and cross-fishery economic issues, which includes four deliverables:

Activities under this strategy include projects that consider 1) developing fishery wide maximum economic yield (MEY) targets in multi-species fisheries, 2) operationalising risk-catch-cost framework, 3) developing efficient quota markets through a double blind concession trading system, and 4) developing [an] economic risk assessment framework.

2.57 At the annual EWG meeting in April 2018, AFMA presented a ‘project concept to undertake a risk assessment of factors that could impact the economics of AFMA fisheries.’25 AFMA agreed to continue to work on the proposal taking into account the EWG’s input.

2.58 In April 2019, AFMA decided to review the project scope and continue to work on the economic risk assessment framework based on the working group’s suggestions.

2.59 In September 2020, the economic risk assessment was dropped from the action item list and it was noted under other business that it had been difficult to decide on the scope of the proposal and whether AFMA would be able to respond to any identified risks. No formal research project has been initiated to address this proposal.

Recommendation no.3

2.60 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority work with its economic working group and research committee to determine AFMA’s approach to managing economic risk.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

2.61 The AFMA Research Committee considered this issue at its meeting on 9 February 2021 and decided to update the Strategic Research Plan in the near future, with a key focus on developing new priorities around economic performance to ensure that the Agency’s monitoring and reporting needs against this objective are met. This includes consideration of a new Fisheries Management Policy on Net Economic Returns (NER) that addresses the NER objective and describes how AFMA will measure it and meet the Commonwealth Harvest Strategy Policy.

Has an appropriate compliance framework been established?

AFMA has established an appropriate risk-based compliance framework. The framework includes appropriate policy, risk management procedures, implementation activities and reporting.

2.62 Fisheries rules and regulations are designed to protect fish stocks, access rights and the broader environment. As the regulator of Commonwealth fisheries, AFMA has an obligation to monitor and promote compliance with fisheries legislation and policy.

2.63 AFMA’s compliance framework is based on education, deterrence and targeted enforcement. AFMA aims to promote voluntary compliance through engagement and education. Targeted compliance activities address deliberate non-compliance. The Fisheries Operations Branch of AFMA is responsible for managing the compliance framework, which includes the:

- National Compliance and Enforcement Policy;

- National Compliance Risk Assessment Methodology; and

- National Compliance and Enforcement Program.

2.64 The Operational Management Committee oversees the compliance program, provides strategic direction and manages the allocation of resources for compliance activities.

2.65 The National Compliance Risk Assessment Methodology sets out how the biennial National Compliance Risk Assessment is undertaken. The National Compliance Risk Assessment identifies the priority risks to be treated in the National Compliance and Enforcement Program.

2.66 The compliance program operates on the basis of the enforcement pyramid, whereby the level of enforcement action reflects the severity of the non-compliance.26 Enforcement actions range from education and promotion of voluntary compliance through to criminal penalties and licence revocation for more serious offences.

2.67 AFMA uses a range of tools to monitor compliance including:

- quota reconciliation records;

- fishery closure monitoring;

- vessel monitoring systems on all vessels in Commonwealth fisheries;

- electronic monitoring in selected Commonwealth fisheries27;

- targeted inspections;

- electronic log books; and

- observer program coverage.

2.68 Annual compliance reporting is publicly available against each of the compliance programs and provides results over a five-year timeframe.

2.69 The effectiveness of AFMA’s compliance and enforcement program is covered in more detail in Chapter 4.

3. Individual fisheries management arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines the management arrangements in place for individual fisheries, planning mechanisms to maximise net economic returns, arrangements for managing conflicts of interest and reporting on the outcomes of fisheries management.

Conclusion

Individual fisheries management arrangements are partly effective. Plans and strategies implemented under Commonwealth policy have not been reviewed in a timely manner. Maximising net economic returns based on scientific modelling has not progressed. Conflict of interest arrangements for commissioners and committees are managed appropriately although administration of staff conflict of interest declarations is not effective. Public reporting on key commercial fish stock is extensive. Aggregate pricing data collected from industry is not being reported.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at updating management plans and strategies, engaging with stakeholders, managing conflict of interest declarations and publishing pricing data.

The ANAO also suggested AFMA determine end dates for COVID-19 exemptions.

3.1 Effective management arrangements for individual fisheries support the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) in achieving its objectives. To assess whether effective arrangements have been established for individual fisheries, the ANAO examined AFMA’s:

- management plans and strategies;

- planning mechanisms for maximising net economic return;

- management of conflicts of interest; and

- internal and external reporting.

Are appropriate management plans and strategies in place for individual fisheries?

Plans and strategies have not been reviewed in accordance with the relevant Commonwealth legislation and policy. Stakeholder engagement with recreational and Indigenous fishing stakeholders has been limited.

3.2 Appropriate management plans and strategies support the effective management of Commonwealth fisheries. The ANAO examined the key plans and strategies required under legislation and Commonwealth policy.

Figure 3.1: Key fisheries management legislation, policy, plans and strategies

Source: ANAO analysis of key legislation, policy, plans and strategies for fisheries management.

Legislation, policy and plans

Statutory management plans

3.3 The Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Fisheries Management Act) forms a key part of the legislative basis for the management of Commonwealth fisheries. Subsection 17(1) and paragraph 17(1)(a) require AFMA to determine plans of management for all fisheries unless an alternate determination is made that one is not required.

3.4 Statutory management plans have been completed for 10 fisheries (see Table 3.1). A determination that a management plan is not required has been issued for 10 fisheries, including for four fisheries that have a management plan in place.28

Harvest strategies

3.5 The Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy (Harvest Strategy Policy) applies to commercial species in Commonwealth fisheries managed by AFMA. AFMA must develop a harvest strategy for Commonwealth fisheries, including those managed jointly under international arrangements where Australia is a major harvester and no harvest strategy has been determined internationally.

3.6 Individual harvest strategies outline processes for monitoring and assessing the biological and economic conditions of commercial species and rules that control fishing activity. Harvest strategies are to be reviewed at least every five years or when fishery conditions change or new knowledge emerges.29

Bycatch and discard work plans

3.7 The 2018 Commonwealth Fisheries Bycatch Policy applies in Commonwealth fisheries managed by AFMA.30 It provides a framework for managing the risk of fishing-related impacts on bycatch species in Commonwealth fisheries. Bycatch and discard work plans for individual fisheries include information on relevant species, risk, data collection, monitoring and performance evaluation to assess the effectiveness of bycatch reduction strategies. The majority of work plans cover a specified two-year period.

Plans and strategies for individual fisheries

3.8 Table 3.1 shows the status of AFMA’s plans and strategies. For the nine fisheries managed solely by AFMA, two harvest strategies are undated, and three are more than five years old. Seven bycatch and discard work plans are out of date.

Fishery management strategies

3.9 In 2017, AFMA planned to develop fishery management strategies, which were intended to integrate harvest strategies, bycatch and discard work plans with ecological risk assessment strategies, data plans and research strategies. However, this plan has not been implemented (see paragraph 2.44).

Table 3.1: Currency of plans and strategies for operational fisheries

|

No. |

Fishery |

Management Plan (latest update) |

Determination issued under paragraph 17(1)(a) |

Harvest strategy (latest update) |

Bycatch and discard work plan |

|

1 |

Bass Strait Central Zone Scallop |

2020 |

nil |

2015 |

2015–2017 |

|

2 |

Coral Sea (4 sectors) |

nil |

1991 |

2019a |

2010–2012 |

|

Undatedb |

|||||

|

3 |

Northern Prawn |

2011 |

nil |

2019 |

2014–2016 |

|

4 |

North West Slope Trawl |

nil |

1991 |

2011 |

2010–2012 |

|

5 |

Western Deepwater Trawl |

nil |

nil |

2011 |

2010–2012 |

|

6 |

Small Pelagic |

2013 |

nil |

2017 |

2014–2016 |

|

7 |

Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark |

2016 |

nil |

2019 |

2018–2019 |

|

8 |

Southern Squid Jig |

2011 |

1991 |

Undated |

2021 |

|

9 |

Macquarie Island Toothfish |

2016 |

1991 |

2020 |

2013 |

|

10 |

Eastern Tuna and Billfishc |

2016 |

nil |

Undated |

2014–2016 |

|

11 |

Southern Bluefin Tuna |

2020 |

nil |

2020 |

2020 |

|

12 |

Western Tuna and Billfish |

2016 |

1991 |

Undated |

2014–2016 |

|

13 |

Heard Island and McDonald Islands |

2016 |

1991 |

2020 |

2013 |

Note a: Aquarium sector.

Note b: Lobster and Trochus, Sea Cucumber and Line Trawl and Trap sectors.

Note c: In 2020, a fishery management strategy was developed for the Eastern Tuna and Billfish fishery, which includes a bycatch strategy and a harvest strategy for one of five key commercial stocks in this fishery.

Note: Out of date and undated documents are shaded orange.

Source: ANAO analysis of AFMA documentation.

Recommendation no.4

3.10 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority ensure harvest strategies and bycatch and discard plans meet the relevant Commonwealth policy and are available on its website.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

3.11 AFMA is reviewing its plans and scheduling of assessments, subject to an assessment of priorities and available resources in and across fisheries. The AFMA website will provide a source of information on fisheries’ plans and assessments.

Assessment of fish stock

3.12 AFMA is responsible for the management of 65 fish stock in nine fisheries managed solely by AFMA and 31 fish stock in seven jointly-managed fisheries.

3.13 Commercial fish stocks in Commonwealth fisheries are regularly assessed by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) using data and assessments compiled by regional fisheries organisations and input from AFMA and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.31

3.14 Commonwealth fish stock status is expressed in three categories.

- Overfished — fish stock with a biomass below the biomass limit reference point or below its specified indicator limit reference point.32

- Subject to overfishing — when a stock is experiencing too much fishing and the rate of removals from a stock is likely to result in the stock becoming overfished.

- Uncertain — there is inadequate or inappropriate information to make a reliable assessment.

Stock solely managed by AFMA

3.15 The 2019 status of the 65 fish stock in the nine fisheries solely managed by AFMA was reported by ABARES in October 2020.33

- Seven stock (11 per cent), all in the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark fishery, are overfished.

- The status of nine stock (14 per cent) is uncertain with respect to their biomass and it cannot be determined whether they are currently overfished.

- No stock are subject to overfishing.

- Twelve stock (18 per cent) are uncertain with respect to whether they are subject to overfishing. Ten of the uncertain stock are in the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark fishery.

Stock managed jointly by AFMA and other parties

3.16 The 2019 status of the 31 stock in the seven jointly managed fisheries was reported by ABARES in October 2020.34

- Five stock (16 per cent) are overfished.

- Five stock (16 per cent) are uncertain with regard to their biomass. The fishing mortality of two (seven per cent) of these stock is uncertain.

- Four stock (13 per cent) are subject to overfishing.

- Stock of Striped Marlin in the Western Tuna and Billfish fishery is both overfished and is subject to overfishing, is ‘heavily depleted’, and its status has remained unchanged for the last two assessment years.35

Application of the precautionary principle

3.17 The Fisheries Management Act requires that AFMA manages fisheries in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development, including the exercise of the precautionary principle. The precautionary principle is defined in the Harvest Strategy Policy:

Where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation. In the application of the precautionary principle, public and private decisions should be guided by:

- careful evaluation to avoid, wherever practicable, serious or irreversible damage to the environment; and

- an assessment of the risk-weighted consequences of various options.36

3.18 The 2017 Guide to AFMA’s Ecological Risk Management states that fishing activities ‘pose high risks in the absence of information, evidence or logical argument to the contrary’.37 However, AFMA has issued Black Tiger Prawn broodstock collection licences since 2006 and only conducted a stock assessment in 2020, which was inconclusive (see paragraph 3.22).38

Harvesting of Black Tiger Prawn broodstock in the Northern Prawn fishery

3.19 The Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) is the highest valued Commonwealth managed fishery and generated $118 million in gross value of production in 2018–19.

3.20 AFMA manages the fishery through a co-management arrangement with a collective of industry participants known as Northern Prawn Fishery Industry Pty Ltd (NPFI).39 NPFI is responsible for a range of services including:

- data management;

- tendering for trawl operators to collect live broodstock; and

- administering access to the NPF for trawl operators under conditional fishing permits, for the supply of broodstock to prawn aquaculture establishments.

3.21 AFMA has provided permits to collect Black Tiger Prawn broodstock for aquaculture farms since 2006. The rate of removal has increased from 800 prawns in 2006 to 9,000 in 2017. In 2018, AFMA was requested to increase the broodstock harvest limit to 20,000. AFMA declined to increase the limit pending the results of a stock assessment. AFMA also identified increasing pressure on broodstock due to the rapid growth in aquaculture as an emerging issue in its 2018–19 and 2019–20 annual reports.

3.22 In February 2019, the NPF Resource Assessment Group recommended a Sustainability Assessment for Fishing Effects be conducted as a matter of urgency. This request flowed in part from the high number of sawfish bycatch caught during broodstock harvesting activities.40 In early 2021, AFMA released a stock assessment for the Black Tiger Prawn. The assessment was inconclusive in relation to the status of the stock due to lack of data. It did not assess the effects of broodstock harvesting on other species or the wider environment.

3.23 Given the continuing absence of data on the status of this stock and the effect harvesting may have on the environment, broodstock harvesting presents risks for AFMA’s compliance with the precautionary principle. These risks have not been properly assessed.

Managing stakeholder engagement

3.24 The objectives of the Fisheries Administration Act 1991 (Fisheries Administration Act) require that AFMA ensure the interests of commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishers are taken into account. The Act also provides for AFMA to consult with industry, the public and state and territory entities that have similar functions to AFMA. AFMA’s purpose statement includes an undertaking to increase consideration of recreational and Indigenous stakeholders.

Interested parties

3.25 Section 17A of the Fisheries Management Act requires AFMA to maintain a register, which is updated annually, of interested parties to be notified with respect to making or changing management plans. For three of the past four years, AFMA has published a notice in the Commonwealth Gazette, inviting parties interested in receiving information about draft management plans to be included on a register. Registers from 2017 to 2020 contain the following information.

- 2017 — two entries.

- 2018 — no register.

- 2019 — one entry.

- 2020 — no entries.

Key stakeholders

3.26 AFMA maintains a separate list of key stakeholders. This list contains 34 entries in four stakeholder categories: environmental non-government organisations; industry; recreational; and government.41 While this list is more comprehensive than the section 17A registers, it is not used to inform interested parties of changes to fisheries management arrangements.

Amendment of the Southern Bluefin Tuna Management Plan

3.27 Southern Bluefin Tuna is an important recreational fishing species. Interested parties for the Southern Bluefin Tuna fishery include state governments, who are responsible for regulating recreational fishing, relevant recreational fishing bodies that represent recreational fishers, as well as Indigenous stakeholders.

3.28 On 7 September 2020, AFMA concluded a 30-day consultation period on amending the Southern Bluefin Tuna management plan to include five per cent of the total allowable catch for recreational fishing. AFMA have advised that the Australian Government ran an extensive consultation process with state governments and recreational fishers. The proposed amendments were published on the AFMA internet site.

3.29 State government fishery management entities and recreational fishing bodies were not included in the register maintained under section 17A of the Fisheries Management Act. Therefore, they were not explicitly notified by AFMA of proposed amendments.42 Consequently, not all relevant interested parties had the opportunity to provide input to the proposed changes.

3.30 In this instance, AFMA may have complied with the Fisheries Management Act requirements to maintain a register and notify changes to the management plan. However, AFMA did not ensure the interests of recreational and Indigenous stakeholders were taken into account in line with the corporate plan’s stated intent of increasing consideration of their interests.

3.31 AFMA should have reasonably expected input from affected state governments and other parties, and should review notification processes to provide for a more comprehensive consultation process.

Recommendation no.5

3.32 The Australian Fisheries Management Authority maintain a current register of interested parties and actively engage with all relevant stakeholders in relation to fisheries management arrangements.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority response: Agreed.

3.33 AFMA’s Stakeholder Engagement Framework and Communication Plan 2020-2022 was endorsed by the AFMA Commission on 5 May 2021 and will form the basis for AFMA’s future engagement posture with stakeholders. However, this is a living document, and AFMA recognises that additional work is required to supplement and refine our implementation strategy for stakeholder engagement.

COVID-19 pandemic response

3.34 AFMA implemented the government’s $10.4 million levy relief package by waiving levy payments that were due on or after 1 April 2020 and refunding 2019–20 levies paid.

3.35 AFMA received 20 requests from industry for exemptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Requests included setting total allowable catch without conducting a biomass survey, early season start dates, selling directly from the vessel43, amending quota carry over requirements and waiving the requirements for a human observer.

3.36 The Fisheries Management Branch assessed the risks and sought appropriate approvals for the exemptions. Eight exemptions were approved by the Commission, eight were approved internally and four were not approved due to the risk being unacceptable. A number of these exemptions do not have set end dates. AFMA should continue to review the actions taken in response to exemption requests and determine end dates for all exemptions.

Are appropriate planning mechanisms in place to maximise net economic return?

AFMA seeks to meet the requirement to maximise net economic returns by pursuing maximum economic yield for individual fisheries. Mechanisms to maximise economic yield are not mature and progress towards establishing maximum economic yield targets for individual fisheries has been slow.

3.37 The Fisheries Management Act requires AFMA to maximise the net economic returns to the Australian community from the management of Australian fisheries. The Commonwealth Harvest Strategy Policy defines the net economic return over a particular period as the difference between fishing revenue and fishing costs.

AFMA’s use of economic targets

3.38 AFMA seeks to meet the requirement to maximise the net economic returns to the Australian community by pursuing maximum economic yield (MEY) for individual fisheries. The Harvest Strategy Policy notes that fishery level MEY is an overarching objective for the implementation of harvest strategies, and should be achieved by specifying targets for key commercial stocks.44

3.39 MEY occurs when the difference between the revenue and cost from fishing is the largest. Determining MEY requires developing bio-economic models that take the dynamics of stocks, costs and prices into account.45 These models integrate the economics of the fishery with the biological characteristics of fish stock and assist in deriving the optimal biomass and fishing effort level to achieve MEY.

3.40 For stocks that do not have an operational bio-economic model, MEY targets can be based on proxies.46 Proxies for the MEY target can be based on measures such as biomass estimates, fishing method, vessel size and days fished. However, proxies used in Commonwealth fisheries are based on biomass estimates only.