Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Collins-class Operations Sustainment

The audit focussed on performance information reporting by the submarine System Program Offices on reliability, safety systems and logistic support services. In the context of the sustainability arrangements, the audit considered combat system upgrades and personnel escape and rescue systems. Any arrangements that the Commonwealth may be considering regarding the potential sale of ASC were not within the scope of this audit.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN)1 has six Collins-class submarines. The submarine force fulfils the roles of maritime strike and interdiction, maritime surveillance, reconnaissance and intelligence collection, undersea warfare, and special forces operations. Construction of the first of the six submarines, HMAS Collins, began in 1990 with delivery in 1996. The final submarine, HMAS Rankin, was delivered in 2003. The submarines are expected to have a remaining asset life ranging from 2026 till 2030.

2. The Collins-class submarine force and the majority of submarine related Defence force infrastructure are operated out of HMAS Stirling in Western Australia. Sustainment of the submarine force occurs across facilities in Western Australia and South Australia.2 Sustainment includes all activities associated with keeping the submarines operational and maintained and includes the provision of logistics, other support services and suitably trained personnel.

3. Sustainment of the Collins-class has presented difficulties to Defence from the introduction into service of the submarines due to two main reasons, namely that:

- during the build stage a number of design deficiencies and consequential operational limitations were identified which meant that the submarines could not initially perform at the level required for naval operations.3 Subsequently, a number of projects covering the heavyweight torpedoes, the submarine platform, the combat system, and propeller and hull needed to be undertaken to address these deficiencies; and

- the Collins-class was introduced into service without a validated strategy for the operational sustainment of the submarines throughout the life of the class and without a good understanding of the real cost for support of the complex submarine platform. The original sustainment budget was loosely based on the experience of the predecessor submarine, the Oberon Class, and Defence advised the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) that this approach was inadequate.

4. Defence advised the ANAO that additional factors affecting maintenance requirements have included: an inadequate initial maintenance regime; an inadequate Integrated Logistics Support regime; poor systems reliability; the need to rely on Design Authorities4 and Original Equipment Manufacturers located offshore;5 that the contemporary technical regulatory frameworks applying to the Collins-class and its systems, which provide confidence that platforms are safe, are significantly more stringent than those that applied to the Oberon Class submarines; and the extensive technical knowledge and comprehension that is required because the RAN is the ‘Parent Navy' for the Collins-class submarines.6

5. To facilitate the proper support of the submarines, Defence has put in place a number of contractual arrangements with commercial suppliers that support their sustainment. The key contract is the Through Life Support Agreement (TLSA) Defence entered into with ASC Pty Ltd (ASC),7 the builder of the submarines, in December 2003. The TLSA is worth up to $3.5 billion over 25 years (15 year agreement, with a further two–five year options). The TLSA covers the full range of platform maintenance support and design services for the submarines to maintain the required level of operational capability and accounts for approximately 60 per cent of the total sustainment expenditure. In addition, there are contracts with a number of external suppliers related to the support of combat systems for the submarines and provision of submarine escape and rescue services and training. While much of the technical support for the submarines is provided by external contractors, Defence has a major role in inventory management related to the equipment and spares for the submarines.

6. The total cost under the sustainment contracts examined in this audit8 for the six submarines in the Collins-class fleet was $226.13 million in 2006–07 and $239.84 million in 2007–08.

Audit approach

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of sustainability arrangements for the Collins-class submarine force. This included examination of the following contracts that are in place relating to sustainment of the submarines:

- the Through Life Support Agreement with ASC;

- the contract covering tactical, communications, navigation sensors, non-acoustic sensors and electronic support measures with Raytheon Australia Pty Ltd (Raytheon);

- the contract for the SCYLLA sonar sub-system with Thales Underwater Systems Pty Ltd (Thales);

- the contract for periscope support with BAE Systems Australia Limited (BAE);

- the Submarine Escape and Rescue Centre contract with Cal Dive International Australia Pty Ltd; and

- the training contract with ASC.

8. The audit focussed on performance information reporting by the submarine System Program Offices on reliability, safety systems and logistic support services. In the context of the sustainability arrangements, the audit considered combat system upgrades and personnel escape and rescue systems. Any arrangements that the Commonwealth may be considering regarding the potential sale of ASC were not within the scope of this audit.

Conclusion

9. The arrangements to sustain the Collins-class submarines necessarily have regard to the build, operational demands, ongoing maintenance and crewing arrangements for the submarines. The 1999 McIntosh Prescott Report9 referred to a number of design deficiencies and consequential operational limitations for the submarines, and Defence has also drawn attention to deficiencies regarding the original strategy for operational sustainment. Recognising these deficiencies within the original Collins-class acquisition process, and the implications of these for the ongoing sustainment of the submarine fleet, the ANAO considers that Defence currently has in place generally sound arrangements for managing submarine sustainment.

10. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) and Navy each have roles in relation to the sustainment of the Collins-class. The principal contract for through life support of the submarines — TLSA — is between DMO and ASC Pty Ltd (the builder of the Collins-class). The TSLA is a cost-plus contract10, with incentives, offering long-term commercial stability to ASC11, with the Commonwealth assuming a significant proportion of the commercial risk that might otherwise apply to ASC. Within this context, DMO is generally managing the day to day elements of the contract effectively. It is also managing effectively the three main separate contracts with combat system suppliers.

11. The ANAO considers that DMO and Navy could improve sustainment performance for the Collins-class through improvement to inventory management. When the Collins-class submarines were delivered there was no prescribed inventory management plan and no computer-based inventory management system in place. The submarines have suffered spares shortfalls since entering service. Defence introduced an Inventory Management Plan (IMP) for the submarines in November 2006 which set out the deficiencies with the Collins-class logistics system including low levels of codification of stores12, problems with inventory management systems13 and obsolescence. It is important that, as resources allow, DMO and Navy make progress in implementing the 2006 Inventory Management Plan and address issues related to onboard management of inventory.

12. Submarine escape and rescue services and training, whilst not part of the direct maintenance of the Collins-class submarines, are integral to their sustainment and capability. DMO is responsible for the management of the contractual arrangements for the delivery of Submarine Escape and Rescue Centre (SERC) services. A number of significant issues have occurred in the management of this capability over time14, including unapproved works and configuration changes that affected the design integrity of the rescue vehicle, the Remora, and the launch and recovery winching system15 for this vehicle.

13. The contract for the provision of SERC services operating the RAN submarine escape and rescue capability, including the Submarine Escape Training Facility (SETF) at HMAS Stirling in Western Australia, expired in June 2008. Prior to the expiry of that contract, the Collins Systems Program Office (COLSPO) within DMO conducted a tender process and selected a preferred tenderer. However, no new contract had been signed by the time this audit was completed.

14. In December 2006, the rescue vehicle Remora was lost on the seabed in approximately 120 metres of water. Following the recovery of the Remora in April 2007, the rescue vehicle and the launch and recovery winching system were each returned to their Original Equipment Manufacturers overseas for remediation. Defence has been required to put alternative rescue services in place for the period since December 2006 as the Remora and the launch and recovery winching system have yet to be introduced back into service. DMO estimates that the total cost of remediation of the Remora and launch and recovery winching system, including addressing obsolescence issues not connected to damage suffered following the loss of the Remora, will be $15.57 million.

15. Any new contract Defence may negotiate to operate the RAN submarine rescue capability presents the opportunity for Defence to put in place arrangements to address the issues that arose in connection with the previous contract. DMO advises that it is currently evaluating options for the future of the RAN organic submarine rescue capability. Defence considers that a contract in place with a UK contractor will maintain the capability currently available to the RAN and provide the DMO with the time to plan and implement the recommissioning of the Australian capability.

16. Navy is effectively managing the contract with its supplier, ASC Pty Ltd, for on-shore submariner training services.16 However, the supply of suitable training services is only one aspect of achieving an adequate supply of appropriately trained personnel. While arrangements to train submariners were within the scope of this audit, the audit scope did not include examination of other significant drivers which affect the success of Navy recruitment and retention strategies. Current demand for submariners is a total of 667 officers and sailors with a supply of 423 at June 2008, or a shortfall of 244 or 37 per cent across all categories of submariners. The shortfall has more than doubled over the previous four years, with the greatest shortage being in the skill areas that have been in demand in the mining industry in Western Australia where the Collins-class submarine force and the majority of submarine related Defence force infrastructure is located.

17. In this context, the ANAO notes that Defence has generally not achieved its annual target for Unit Ready Days17 (particularly quality Unit Ready Days) despite the target often being adjusted downwards when reviewed mid year.18 A significant contributor to the difficulty in achieving Unit Ready Days (URDs) has been that the number of trained submariners available in Navy has consistently fallen short of requirements and this is having a considerable impact on overall submarine force capability. The ANAO also notes that there has been a substantial increase in the cost of URDs over the life of the current TLSA. With reduced numbers of URDs and increasing sustainment costs, the unit cost of achieved quantity URDs escalated from $254 015 in 2003–04 to $272 545 in 2007–08, and the unit cost of achieved quality URDs escalated from $259 537 to $429 052 in the same period.

18. Defence advised the ANAO that the shortage of submariners has been the primary driver for having three submarines in Full Cycle Docking from May 2008. As Defence makes progress in addressing the shortfall in the submariner workforce, the capacity of DMO to effectively negotiate the delivery of timely and cost-effective services from all of its contractors, in particular ASC, together with the capacity of Defence's inventory management arrangements to facilitate the deployment and sustainment at sea of more submarines, will become increasingly important.

Key findings by chapter

Management framework for sustainment arrangements (Chapter 2)

19. Defence faced challenges in establishing appropriate sustainment arrangements for the Collins-class because of deficiencies in design and sustainment arrangements within the original acquisition. Notwithstanding, the ANAO considers that Defence has put in place an appropriate management framework for the provision of sustainment support for the Collins-class submarine fleet.

20. In announcing the TLSA in December 2003, the then Ministers for Defence, and Finance and Administration stated that it fulfilled a Government commitment that all submarine full cycle dockings would be undertaken by ASC in South Australia. The TSLA is a cost-plus contract, with incentives, offering long-term commercial stability to ASC19, with the Commonwealth assuming a significant proportion of the commercial risk that might otherwise apply to ASC.20

21. This arrangement was put in place with the intent of the Commonwealth benefiting from ongoing support of the Collins-class submarines and retaining the capacity in Australia to assist the development of current and future submarine capability. The ANAO notes, however, that there are inherent tensions in the arrangements related to the TLSA. For instance, the Government has expressed the wish to preserve submarine maintenance capability (which lies with ASC) in Australia while the strategic objectives of the TLSA include reducing the real costs of owning the submarines (objective (b)). The cost-plus nature of the TLSA contract also limits DMO's capacity to apply normal commercial pressures in looking to obtain the best value for money for the investment in sustainment of the Collins-class.

22. The Australian Government has wholly owned ASC since 2000. However, the previous Government had expressed its intention to sell the company and ASC's Statement of Corporate Intent 2008 to 2011 states that the company is working with the shareholder (that is, the Australian Government) in preparing the company for sale. The TLSA contractual arrangements are a critical element of the relationship between DMO and ASC, requiring close consideration in making any decision to sell ASC.

23. DMO has established appropriate Systems Program Offices (SPOs)21 which have responsibility for managing its principal sustainment activities, including the contracts DMO has in place to secure necessary external support. These are the:

- Collins Systems Program Office (COLSPO), which has overall responsibility for platform integrity and performance; and

- Submarine Combat Systems Program Office (SMCSPO), which has responsibility for communications, navigation and combat systems including weapons systems.

24. As noted in paragraph 2, the provision of suitably trained personnel is also a component of sustainment. Within Navy there is a clear allocation of responsibility for the provision of training for the Collins-class submarine force. Navy Systems Command (NAVYSYSCOM) is responsible for the shore based training of crew for the submarines and has a contract in place with ASC for this.

Maintaining Collins-class operations (Chapter 3)

25. The ANAO notes that having viable, long term suppliers of ongoing maintenance services is a critical element in Defence's capacity to effectively sustain the Collins-class submarine force. The TLSA with ASC and the contractual arrangements with each of the major combat system contractors (Raytheon, Thales and BAE) have been put in place to secure these services.

26. From its examination of payments, reporting and communications arrangements, the ANAO considers that DMO is generally managing the day-to-day elements of the TLSA with ASC in an effective manner. However, the cost effectiveness of the TLSA to Defence relies on an annual capability payment negotiation process achieving an outcome that appropriately balances cost to Defence and returns to ASC.

27. The negotiation process includes agreeing appropriate Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), against which ASC's performance is measured and its entitlement to Performance Incentive Payments is determined. Clause 19.18(d)(i) of the TLSA indicates: ‘the KPIs to be met by ASC in order to achieve Performance Incentives should ordinarily be set at a level that are as likely to be met as not.' It is difficult to reconcile the expectations reflected in this clause with the extent of ASC's success in achieving performance incentives over the years. Since the TLSA commenced, the company has received, on average, 87 per cent of the available incentives for the four years 2003–04 to 2007–08. The ANAO notes that DMO's own assessment of performance (see paragraph 3.27) was that ASC was performing as contracted or just above that level over the period when these substantial performance incentives were being paid.

28. ASC advised ANAO in January 2009 that:

... it is often the case that the customer [in setting an incentive] takes a ‘stretch schedule target', dictated say, by RAN operational imperatives, to be the required project schedule. Again meeting the date would most likely only generate an ‘as contracted' customer assessment, whereas ASC and its people have made huge efforts, often working long hours, to meet the date required. It should be noted that ASC needs to secure a substantial proportion of the incentives to achieve a reasonable commercial return. Even if ASC were to achieve 100% of its incentives, its returns would not be abnormally or even particularly high ...

29. The current design of the Performance Incentive Payments arrangements in the TLSA is such that ASC is provided with substantial payments for performance broadly in line with the contractual requirements. The ANAO drew Defence's attention to clause 19.19 of the TLSA that provides for a review of remuneration arrangements to occur within four years from the commencement date. The ANAO suggested that the KPIs should be reviewed to ensure that they take appropriate account of the expectations of the parties set out in the relevant clauses of the TLSA22 and are calibrated to appropriately reward ASC for quality performance while delivering against the strategic objectives23 for the contract.

30. Defence advised that, at the time the provision in clause 19.19 was available, DMO was having difficulty achieving an agreed costed response from ASC for 2008–09.24 Defence added that, with any review of profits and incentives also requiring the agreement of ASC, it was not considered to be an appropriate time to commence such a review. Defence further advised that, given that it is pursuing significant changes to the TLSA to put it on a firmer commercial basis (in anticipation of the sale of ASC), it considered that a better result for a review of the profit and incentive structure (as well as the fundamental cost plus nature of the contract) would be achieved in the context of the overall changes being sought.

31. The ANAO considers that the management arrangements for existing combat system support contracts are appropriate, including the processes applied to payment arrangements and reporting by contractors. Issues have arisen with the contract related to periscopes that have highlighted the difficulty and delays in certifying and repairing periscopes, and the emerging level of obsolescence affecting this key combat system.25

Inventory management

32. When the Collins-class submarines were delivered there was no prescribed inventory management plan and no computer-based inventory management system in place. The submarines have suffered logistics spares shortfalls since entering service. DMO introduced an Inventory Management Plan (IMP) for the submarines in November 2006 which set out the deficiencies with the Collins-class logistics system including low levels of codification of stores26 , problems with inventory management systems27 and obsolescence. A consequence of obsolescence is that maintenance scheduling becomes more complex and greater delays in completing maintenance occur resulting in reductions in capability.

33. The IMP stated that by December 2008 there would be an accountable, mature and self sustaining logistics system and identified a number of goals that had to be met as a prerequisite to achieving this objective. One of these goals was 100 per cent codification of stores by 30 June 2007 to provide the ability to manage items in the Standard Defence Supply System (SDSS), allow tracking of consumption rates and prediction of future requirements. However, Defence advised ANAO that the codification project was not completed until June 2008. As the completion of this project is a prerequisite for a number of other important activities28 in the IMP, the target dates for completion of these activities have also been delayed.

34. The ANAO considers that there has been some improvement in Demand Satisfaction Rates (an inventory performance measure included in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement between the DMO and Navy) over the past two years, although overall performance remains unsatisfactory. Further improvement is required in the management of inventory related to the sustainment of Collins-class submarines. Defence advised ANAO in September 2008 that it now considers Demand Satisfaction Rates not to be a reliable measure and is relying on a number of alternative measures.29 In addition to the activities already underway as part of the IMP, there is a need for an obsolescence remediation plan which incorporates all major suppliers and investigation of arrangements with major suppliers with the aim of reducing associated administrative costs and the lead times for parts.

35. A further challenge to the sustainment of the Collins-class fleet is that each submarine currently has a different combat system configuration and, given the stage they are in their life cycles, there will never be a uniform baseline across the fleet. At best there will be two baselines across the six submarines. The ANAO notes that currently the Ships Information Management System (SIMS)30 is not used for onboard inventory management on the Collins-class. Defence advised ANAO that necessary detail to maintain combat system software is retained within SMCSPO and its contractors using specialised software configuration management systems, rather than SIMS.

Onboard inventory management

36. To provide the best possible chance of crew being able to rectify defects from onboard spares, DMO's IMP identified the need for the creation of a ‘live' Ships Allowance List.31 To produce such a list requires the implementation of an onboard inventory system to supply the required data. The Shipboard Logistics Information Management System (SLIMS) has been installed and trialled on two of the Collins-class submarines unsuccessfully. The lack of success was attributed by COLSPO to the insufficient availability of ‘store specialists' amongst the available submariners. Whilst Navy advised that it intended to pursue filling such positions, there are currently no target dates for this, nor for the continuation of trials or the installation of SLIMS on the remaining submarines.

Unit Ready Days

37. Defence has consistently not achieved the planned level of Unit Ready Days (URDs) for the Collins-class submarines, with the percentage of quality URDs32 achieved falling from 82.8 per cent of the target in 2003–0433 to 46.1 per cent in 2006–07, before rising to 57.6 per cent in 2007–08. With reduced numbers of URDs and increasing sustainment costs, the unit cost of achieved quantity URDs escalated from $254 015 in 2003–04 to $272 545 in 2007–08, and the unit cost of achieved quality URDs escalated from $259 537 to $429 052 in the same period.

38. Largely as a direct result of the intention for the equivalent of three submarines to be in either full cycle or mid cycle docking during the year34, the planned URDs for 2008–09 is set at the lowest level since the introduction of this measure for the Collins-class in 2003–04. The planned URDs for 2008–09 is only 684, which is significantly lower than the target for 2007–08 of 970.35 Accordingly, even if all of these planned URDs are achieved, the unit cost for URDs in 2008–09 will rise further not only because the number of URDs achieved for the Collins-class will be lower than in previous years but also in light of the significant costs involved in undertaking such a high level of major maintenance activity in the financial year.

39. It is unclear whether the current strategy of having high levels of maintenance undertaken in specific years, such as 2008–09, will lead to more cost effective outcomes in the future, given the ongoing commitment to fund a base level of maintenance capability in ASC through the TLSA. Navy advised the ANAO in June 2008 that the shortage of trained personnel to operate the submarines had been the primary driver for having three submarines in docking from May 2008. The DMO took the increased submarine access afforded by the shortage of submarine crews as an opportunity to undertake additional submarine upgrades. This additional upgrade work has extended planned maintenance periods and is an added factor that has also contributed to a dip in planned URDs.

Submarine escape and rescue services (Chapter 4)

40. Submarine Escape and Rescue Centre (SERC) services36 have been provided under contract to DMO. In December 2006, the rescue vehicle, the Remora, was being operated by the then contractor when a failure of the launch and recovery winching system resulted in the Remora being lost on the sea bed in approximately 120 metres of water. The Remora was subsequently recovered, although considerable remedial work has been required, including to the launch and recovery winching system. To undertake the remediation required both the Remora and the launch and recovery winching system to be returned to their Original Equipment Manufacturers overseas.37 The Remora and the launch and recovery winching system are now both back in Australia but are yet to be reintroduced into service.

41. Defence advised the ANAO that alternative rescue services are in place. The Commander of the Australian Fleet initiated an arrangement for the UK Submarine Rescue Service, with its submersible, to be available to support submarine materiel certification and crew competency assessment. Defence advised in January 2009 that, until a longer term position is resolved, it has contracted the UK contractor for a six month standby submarine rescue service, incorporating emergency deployment in support of a disabled submarine. The Collins-class submarines are also certified to mate with the US Navy Submarine Rescue System in shallow waters. The Director of COLSPO advised the ANAO in June 2008 that the unavailability of the Remora has not affected any training exercise or any sea trials post Full Cycle Dockings.

42. In January 2009, Defence advised that following refurbishment in Canada by Oceanworks International, and the conduct of certain testing, the Remora arrived at Fremantle in August 2008. Remora is currently in storage at Henderson, WA. The launch and recovery winching system has completed certain testing in Glasgow but this was not accepted by Defence due to deficiencies. A review by the Class Society DNV of the launch and recovery winching system is outstanding and DMO is currently evaluating options for the future of the RAN organic submarine rescue capability. Defence considers that the contract with the UK contractor will maintain the submarine rescue capability and provide the DMO with the time to plan and implement the recommissioning of the Australian capability.

43. A five year contract for the provision of SERC services expired in June 2008. COLSPO conducted a tender process to secure a new contractor to provide these services in 2007–08. A preferred tenderer was selected as a result of this tender process. However, no new contract had been signed at the time this audit report was finalised. The 2003 SERC contract which ended in June 2008, covered both the operation of the Submarine Escape Rescue Suite (SERS) and the operation of the Submarine Escape Training Facility (SETF). On 31 January 2009, Defence issued a media release38 discussing a temporary measure that had been put in place to secure pressurised submarine escape training for RAN submariners as part of their ongoing safety training program. In the absence of a current contractor to operate the SETF, Defence plans to send up to 100 submariners to Canada later this year to undertake such training. The media release pointed out that the cost of sending the submariners to Canada does not require any new funding as the training will be paid for with money already allocated for training that would have been conducted at the SETF. The media release further noted that RAN personnel could still take part in unpressurised escape training at the SETF which would minimise the time required to continue their training in Canada.

44. A number of significant issues occurred in the management of Defence's SERC capability over time, including unapproved works and configuration changes that have affected the design integrity of the Remora and the launch and recovery winching system. The negotiation of any new contract to operate this capability would provide Defence with the opportunity to put in place arrangements to address the issues that arose in connection with the previous contract. The total cost of the previous contract signed in 2003 for the five years to June 2008 was $20.19 million. In addition, following the loss of the Remora in December 2006, DMO has estimated its total expenditure on recovery, repairs and remediation of the rescue vehicle, as well as repair of the launch and recovery winching system, will be $15.57 million.

45. The ANAO notes that the Defence Procurement Policy Manual refers to the consideration of circumstances when it may be appropriate that the Commonwealth be named as an insured on a supplier's insurance policies, including where the Commonwealth has an interest in the property insured. Notwithstanding the reference made in Defence's policy, the 2003 contract did not require that the Commonwealth be named as an insured in the contractor's insurance policy for plant and equipment despite the fact that Defence owned both the rescue vehicle, the Remora, and the launch and recovery winching system. Defence advises that any new contract for these services will require that the Commonwealth be specified as an interested party on the relevant policy.

Training (Chapter 5)

46. ASC undertakes the training role for submarine crew through a contract arrangement with the Director General Nary Personnel Training, an element of Navy Systems Command (NAVSYSCOM). The contract is managed by Training Authority Submarines, a business unit of NAVSYSCOM located in the Submarine Training and Systems Centre at HMAS Stirling. The current Training Contract with ASC is for five years from July 2005 to 2010 at a cost of $4.48 million per annum (2005–06 prices). Whilst the contract has been adequately managed, the number of trained submariners has been steadily falling below requirements.

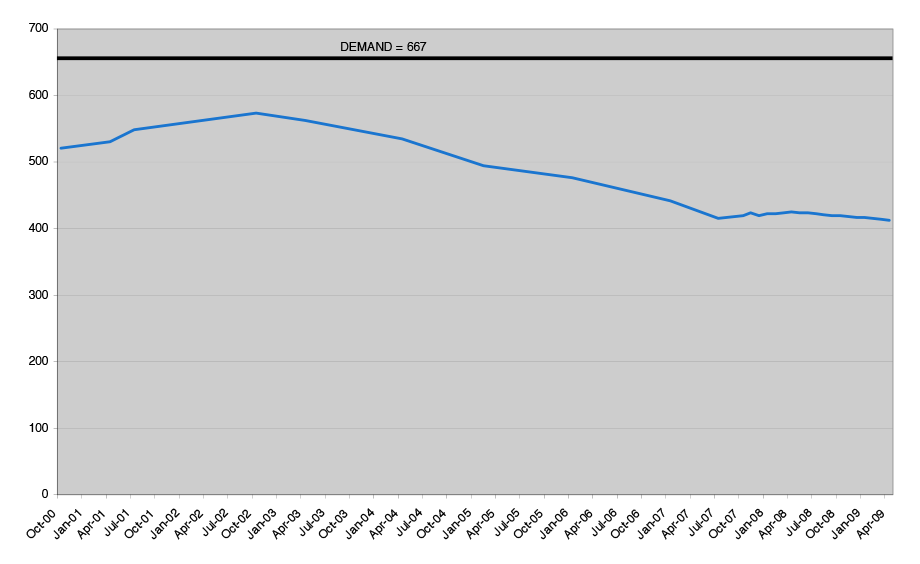

47. Current demand for submariners is a total of 667 officers and sailors with a supply of 423 at June 2008, or a shortfall of 244 or 37 per cent across all categories of submariners. The shortfall has more than doubled over the last four years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Numbers of available submariners – October 2000 to April 2009

Source: Submarine Training and Systems Centre.

48. The shortfall is greater if the numbers of submariners that are unable to be deployed through medical, compassionate or other reasons are taken into account. As at June 2008, 38 submariners could not be deployed bringing the total shortfall of submariners to 43 per cent.

49. Factors affecting this situation include: the loss of submariners to alternative employment in Western Australia; lower numbers of available new submariners because of Navy's recruiting success levels; and insufficient billets on operational submarines available to train crew.

50. Part of the ADF's response to recruitment shortfalls was to increase pay and allowances including retention bonuses across all forces in August 2007.39 In April 2008, a Navy Capability Allowance aimed at retaining trained and experienced serving sailors was announced. For submariners of Able Seaman to Chief Petty Officer ranks who agree to a further 18 months service, the allowance provided is $60 000. In addition, in May 2008, the Chief of Navy instigated a review of submarine workforce sustainability to report by the end of October 2008. In January 2009 Defence advised that the Chief of Navy is currently reviewing the report on submarine Workforce Sustainability.

Recommendation

51. The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving Defence's inventory management for the Collins-class.

Summary of agency response

52. The Department of Defence provided a response to this report on behalf of Defence and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO):

The Australian National Audit Office has made one recommendation in this report. Defence agrees with qualification to the recommendation.Regarding the recommendation, the ANAO considers DMO and Navy could improve sustainment performance for the Collins-class through improvement to inventory management. Defence introduced an Inventory Management Plan for the submarines in 2006 which set out the deficiencies with the Collins-class logistics system including low levels of codification of stores, problems with inventory management systems and obsolescence. DMO and Navy intend to make progress in implementing the 2006 Inventory Management Plan and address issues related to onboard management of inventory. Consequently, this recommendation is agreed with qualification; that is, that progress will be made as resources allow.

Overall, Defence notes that “the ANAO considers that Defence currently has in place generally sound arrangements for managing submarine sustainment”. However, Defence notes that the audit has identified areas that Defence (specifically, DMO and Navy) can focus on with a view to making further improvements in the management of the Collins-class operations sustainment.

Footnotes

[1] RAN is the correct acronym for the Royal Australian Navy. However, for simplicity, the Royal Australian Navy is generally referred to as ‘Navy' throughout this report.

[2] The Collins-class submarine force and the majority of submarine related Defence force infrastructure are operated out of HMAS Stirling in Western Australia. However, there are also support facilities located at ASC Pty Ltd at Adelaide in South Australia and ASC has an additional covered submarine facility at the Common User Facility at Henderson in Western Australia.

[3] This was the finding of a 1999 report (the McIntosh Prescott Report) commissioned by the then Minister for Defence, ‘Report to the Minister for Defence on the Collins-class Submarines and Related Matters from Malcolm McIntosh AC, Kt and John B. Prescott, AC, 20 June 1999 (Section 2. What's Wrong).

[4] The Design Authority (DA) is the organisation responsible for the initial design, design review and internal design approval of materiel systems; and for the design of modifications or changes to a materiel system. In the case of the Collins-class this is Kockums in Sweden.

[5]The Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) is the company which produced a particular item of equipment at the construction stage. The reliance on offshore DAs and OEMs has meant a convoluted, time consuming and hence costly logistics chain in terms of accessing design authorisation for changes. Equipment such as the towed array handling system, buoyant wire antenna, masts and periscopes have specialist maintenance requirements which also require returning the equipment to overseas based OEMs in some cases.

[6] Navy operates the Collins-class submarines as a ‘Parent Navy'. This refers to the extensive knowledge, engineering services, configuration control, supply support, training, intellectual property, and technical comprehension of design concepts, principles and systems which affect the through-life support of a naval platform that is vested in, and managed by, the Navy of origin. It also requires development of an industry capacity that includes an understanding of the design philosophy to the extent necessary to design and implement modifications and undertake major repairs safely and effectively. The costs of establishing a Defence capability as a Parent Navy, and the cost of establishing a national industry capacity, proved much more costly for the Collins-class than envisaged during the build.

[7] The Australian Government had a substantial minority shareholding in ASC during the main construction period of the Collins-class submarines. In November 2000, the then Government acquired the portion of the shareholding in ASC that it did not already own. In announcing the acquisition of full ownership of ASC, the then Ministers for Defence, Industry, Science and Resources, and Finance and Administration indicated the then Government's intention was that the company be restructured to implement more sustainable arrangements for the future support of the Collins-class submarines and facilitate ASC's onward sale. In announcing the TLSA in December 2003, the then Ministers for Defence and Finance and Administration stated that the agreement fulfilled a Government commitment that all submarine full cycle dockings would be undertaken by ASC in South Australia and provided the basis for the long-term commercial viability of ASC. ASC's Statement of Corporate Intent 2008 to 2011, tabled in the Parliament in September 2008, states that among the company's corporate objectives for the period is ensuring that the other corporate objectives are met in a manner that will facilitate the timely privatisation of the company and to support the shareholder [that is, the Australian Government] in preparing the company for sale.

[8] This audit also considered the costs associated with work done on the remediation of the Remora submarine rescue vehicle and associated equipment (related to Submarine Escape and Rescue).

[9] See footnote 3.

[10] Under a cost-plus contract, bona fide costs incurred by the contractor are reimbursed by the principal, together with a margin calculated in a predetermined manner. Costs plus contracts may be based on cost plus percentage, cost plus fixed fee or cost plus a sliding-scale fee.

[11] Defence's Procurement Approval of 22 December 2003 advised that ‘The TLS agreement establishes ASC as the principal provider of platform related submarine maintenance and provides the basis for the long-term commercial viability of ASC. It will also preserve the important strategic capability represented by the ASC's core skill base of submarine maintenance and design expertise.' ASC commented to ANAO that the TLSA has a profit floor and a cap.

[12] To facilitate asset management and financial reporting, all items of supply that are repetitively procured, owned, stored or repaired by Defence are required to be codified. As a sponsored nation in the NATO Codification System (NCS), Australia is required to adhere to the policies and principles as published in the NATO Manual of Codification and accordingly Defence adheres to the NCS.

[13] Among other things these problems included loss of trust in the logistics system by submariners and a lack of interest in maintaining onboard accounts.

[14] ASC was the original provider of the Submarine Escape and Rescue Suite services and some of the equipment from 1996 to June 2003. Following a tender process, Fraser Diving Australia was awarded a five year contract in June 2003 to provide Submarine Escape and Rescue Centre services, including operation of the Submarine Escape and Rescue Suite. Fraser Diving Australia was sold to Cal Dive International in 2006 and subsequently operated as Cal Dive International Australia Pty Ltd.

[15] The function of the launch and recovery winching system (the LARS) is to facilitate the launch and recovery of the Remora from a mother ship.

[16] This excludes submarine escape training services. These services were provided previously by the Submarine Escape and Rescue Centre contractor using the SETF at HMAS Stirling. However, following the expiry of this contract in June 2008 and the stalled negotiations with the preferred replacement tenderer, Navy has put in place temporary arrangements for the provision of this training.

[17] Unit Ready Days (URDs) are the number of days that a force element is available for tasking. Planned URDs are determined by aggregating total days for the unit in commission, less all days when the unit is programmed to be in major maintenance and conducting pre-workup (preparations for initial operational training). In measuring URDs, Defence distinguishes between the total number of URDs achieved (called Quantity URDs) and Quality URDs. The quality measure takes into consideration any constraints on operations that may be imposed such as systems shortcomings or availability of submariners.

[18] URDs targets were introduced for the Collins-class in 2003–04. The target of expected URDs for

2008–09 contained in the relevant Defence Portfolio Budget Statements is 684, which is the lowest since targets were introduced and compares to a target for 2005–06 of 1463 in the Defence Additional Estimates Statements for that year (2005–06 being the year in which the highest target was set). The low target for 2008–09 is attributed to the plan to have four submarines in docking at various points during the year — two submarines in Full Cycle Docking for the entire year, one other in Full Cycle Docking for half of the year and another in Mid Cycle Docking for part of the year.

[19] Defence's Procurement Approval of 22 December 2003 advised that ‘The TLS agreement establishes ASC as the principal provider of platform related submarine maintenance and provides the basis for the long-term commercial viability of ASC. It will also preserve the important strategic capability represented by the ASC's core skill base of submarine maintenance and design expertise.'

[20] See paragraph 2.24 for a discussion of a number of features included in the TLSA aimed at assisting the commercial viability of ASC including:

• limiting ASC's liability to $10 million in any financial year in respect of claims arising from ASC's supplies to the Commonwealth;

• the Commonwealth indemnifying such claims in excess of the liability limit or in respect of damage to property, injury or death; • ensuring ASC's TLSA financing costs are low by maintaining a positive cash flow; and

• paying ASC's monthly capability payments (covering labour, material and sub-contractor costs, plus a profit component) in advance, with retrospective adjustment for the actual work undertaken.

[21] The DMO's System Program Offices (SPOs) are the business units that manage the delivery of materiel sustainment under Materiel Sustainment Agreements made between the Capability Managers in Defence and the Chief Executive Officer of the DMO.

[22] In particular in clause 19.18(d)(i) and clause 19.18.(d).(iv) of the TLSA. See paragraphs 3.29 and 3.30.

[23] See paragraphs 2.21 to 2.23 and Table 2.1 for further information about the strategic objectives of theTLSA.

[24] In January 2009, Defence advised that all incentives for 2008–09 have yet to be agreed.

[25] In September 2008, Defence stated that the underlying problem with the periscopes is the lack of an in-country, competent, design support network for periscopes that could certify the equipment after repair. BAE Systems advised ANAO that funding for recertifications of resource materials was secured in January 2005 and that at that time 12 of 16 systems were out of certification. BAE Systems also noted that obsolescence management funding was secured in August 2008.

[26] To facilitate asset management and financial reporting, all items of supply that are repetitively procured, owned, stored or repaired by Defence are required to be codified. As a sponsored nation in the NATO Codification System (NCS), Australia is required to adhere to the policies and principles as published in the NATO Manual of Codification and accordingly Defence adheres to the NCS.

[27] Among other things these problems included loss of trust in the logistics system by submariners which led to a lack of interest in maintaining onboard accounts.

[28] For example, population of an Assembly Parts List was reliant on 100 per cent codification first having been completed. An Assembly Parts List is a list of equipment identifying assembly and associated sub assembly relationships, utilising data such that a technician can identify a spare as well as allowing a quarterly Submarine Allowance List to be calculated to provide a submarine with an accepted statistical chance of rectifying a defect from onboard spares. As a consequence of the lack of a populated Assembly Parts List, onboard spares allowances for the submarines have been based on Original Equipment Manufacturer recommendations, which have not been maintained and updated and so do not reflect current demand. Defence advised the ANAO in September 2008 that an Assembly Parts List for the Collins-class was expected to be populated by 31 December 2008.

[29] Defence referred to measures such as Configuration Effectiveness, Ship's Allowance List Effectiveness and UNDA (Urgency of Need Designator) Demand Satisfaction.

[30] The Ships Information Management System is a management program the RAN uses that contains relevant technical data related to a particular vessel. It is also a data base indicating equipment acquisitions to support the vessel. It is used for onboard inventory management.

[31] Most of the Navy's surface ships have inventory management software that by recording usage and based on historical consumption and onboard maintenance capability produces a ‘live' Ships Allowance List

[32] In measuring URDs, Defence distinguishes between the total number of URDs achieved (called Quantity URDs) and Quality URDS. The quality measure takes into consideration any constraints on operations that may be imposed such as systems shortcomings or availability of submariners.

[33] The expected number of URDs for 2003–04 was 945 against an achievement of 799 Quantity URDs and 782 Quality URDs. The expected number of URDs for 2007–08 in the Defence Portfolio Budget Statements was 1004. The revised target included in the 2007–08 Defence Additional Estimates Statements was 970. Achievement against the revised target was 880 Quantity URDs and 559 Quality URDs.

[34] Four submarines are planned to be in docking at various points during the year — two submarines in Full Cycle Docking for the entire year, one other in Full Cycle Docking for half of the year and another in Mid Cycle Docking for part of the year.

[35] This is the revised target for 2007–08 set out in the Defence Additional Estimates Statements.

[36] The submarine escape and rescue service capability for the Collins-class consists of the Submarine Escape Training Facility (SETF) and the Submarine Escape Rescue Suite (SERS). The SETF is a Commonwealth supplied facility located at HMAS Stirling at Garden Island in Western Australia. The SERS is a fully integrated suite of equipment designed to rescue and treat survivors of a disabled submarine under a full range of accident scenarios. It provides a deployable capability to rescue submariners directly from a stricken submarine using a submersible vessel (the Remora) operating from a surface ship.

[37] The Remora was shipped to OceanWorks International in Canada for detailed examination, restoration and obsolescence remediation of its capability. The opportunity was also taken to undergo a full 10 year recertification by the classification society. Classification societies are organisations that establish and apply technical standards in relation to the design, construction and survey of marine related facilities, including ships and offshore structures. The launch and recovery winching system was returned to Caley Ocean Systems in Scotland for repair and subsequent survey and testing. Oceanworks is integrating the work on both the Remora and the launch and recovery winching system and managing the certification of both of these through the classification society.

[38] Defence Media Release, Navy Puts Safety First with Submarine Force, 31 January 2009.

[39] For example, a marine technician earning $50 254 per annum in 2001 now receives $80 451 including a $10 000 retention bonus.