Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Cape Class Patrol Boat Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service's management of the Cape Class patrol boat program.

Summary

Introduction

1. In November 2009, the Government endorsed the Civil Maritime Security Capability Plan (CMSCP), which provided guidance for maritime security planning in Australia to 2020. The plan included a number of key performance requirements for an effective maritime patrol function that were beyond the capabilities of the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s (Customs) existing fleet of eight Bay Class patrol boats. At that time, the Bay Class patrol boats were also entering the latter stages of their planned 10-year operational life.

2. In response to the planned capability requirements, in the May 2010 Federal Budget the Government approved funding of $573.6 million over 10 years (2010–11 to 2019–20) for the acquisition and operating costs (including crew, maintenance and fuel costs) of eight larger and more capable patrol boats to replace the Bay Class patrol boat fleet—the Cape Class patrol boats (CCPBs).1 As part of its approval, the Government required that Customs maintain a level of effort of 2400 patrol days per annum across the patrol boat fleet.

3. Following an open request for tender (RFT) in July 2010, a contract for the acquisition of eight Cape Class patrol boats and in-service support (ISS) was signed on 12 August 2011 between the Commonwealth (represented by Customs) and the prime contractor (Austal Ships Pty Ltd, based at Henderson in Western Australia). The total budget for the acquisition was set at $316.5 million over the period 2011–12 to 2015–16. This included $277.7 million in acquisition contract milestone payments to the contractor.2

4. The schedule for Customs’ acceptance of the eight vessels extends from 1 March 2013 to 31 August 2015, and is outlined in Table S.1.

Table S.1: CCPB acceptance schedule

|

CCPB Number |

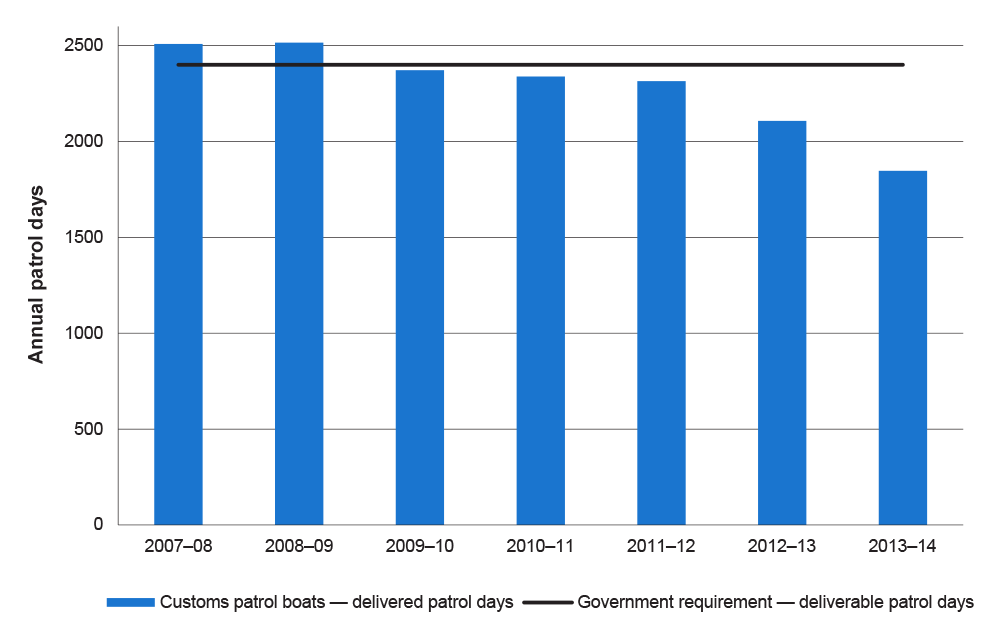

Name |

Planned Acceptance Date |

Actual Acceptance Date |

|

|

CCPB#1 |

Cape St George |

1 March 2013 |

17 April 2013 |

|

|

CCPB#2 |

Cape Byron |

16 June 2014 |

19 May 2014 |

|

|

CCPB#3 |

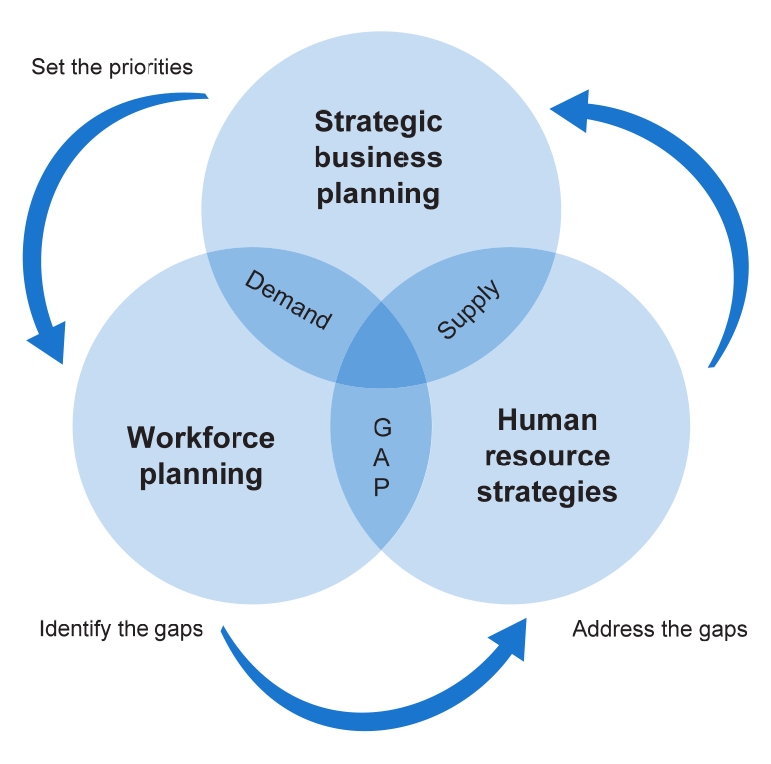

Cape Nelson |

15 September 2014 |

15 September 2014 |

|

|

CCPB#4 |

Cape Sorrell |

15 December 2014(1) |

- |

|

|

CCPB#5 |

Cape Jervis |

2 March 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#6 |

Cape Leveque |

1 May 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#7 |

Cape Wessel |

1 July 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#8 |

Cape York |

31 August 2015 |

- |

|

Source: Customs program documentation.

Note 1: Customs advised that, as at November 2014, acceptance of CCPB#4 is on schedule.

5. The acquisition of the CCPBs is one component of a broader program of activities necessary to deliver a fully capable patrol boat fleet. Customs has used elements of the Department of Defence’s (Defence’s) fundamental inputs to capability (FIC) model (personnel, organisation, collective training, major systems, supplies, facilities, support, and command and management) as a conceptual framework for the management of the activities and schedule required to achieve the CCPBs full capability. A key area of planning involves an expansion in crew numbers and an increased qualification and training effort to meet regulatory requirements associated with the increased size and capability of the new vessels.3

6. The CCPB acquisition program is managed within Customs’ Border Force Division in Canberra. The program office also maintains a small resident project team at the contractor’s shipyard.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Customs’ management of the Cape Class patrol boat program.

8. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- sound capability development and government approval processes were in place to deliver the best value for money;

- the contract arrangements are currently facilitating the delivery of the program at the agreed cost, schedule and performance parameters;

- appropriate governance and program oversight arrangements were in place; and

- suitable arrangements have been established for the future operation of the capability through the ISS arrangements, crew recruitment and training, and the necessary support infrastructure.

Overall conclusion

9. At a total budgeted cost of $316.5 million, the program to deliver eight Cape Class patrol boats over the period from 2013 to 2015 represents the largest procurement activity undertaken by Customs.

10. Overall, Customs established sound arrangements to underpin the acquisition of the CCPB fleet, with the initial three vessels delivered in-line with the agreed schedule and, where testing has been completed, to the established capability requirements. In this context, the complex vessel acquisition stage of the program has been well managed by Customs as a key element of its program to deliver an enhanced patrol boat capability. There are, however, remaining risks relating to the ongoing support of vessel operations that will require active management, particularly in regard to the: development of a clear resourcing strategy for ongoing vessel operations; and expansion of the number and qualifications of crew members required to operate the new, larger patrol boats.

11. To manage the development and delivery of the CCPBs, Customs implemented a capital acquisition process similar to that employed by Defence. A number of lessons from the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) experience with the acquisition of the Armidale Class patrol boats were successfully incorporated into Customs’ approach to the management of the acquisition program.4 Further, an early focus on engaging industry in relation to the technical detail and cost estimates for the two capability options being considered (a like-for-like replacement of the existing Bay Class patrol boats or an enhanced patrol boat capability) provided Customs with early insights into industry’s capacity to deliver a fleet of patrol boats. In addition, sound governance and generally appropriate probity oversight arrangements were utilised, with the acquisition process managed in accordance with approved plans.

12. The acquisition of the CCPBs has been supported by sound contractual arrangements, with contractor payments linked to the achievement of major milestones such as Customs’ formal acceptance of each CCPB. The outcomes from the operational test and evaluation program in September 2013 confirmed that the first CCPB was capable of meeting critical operational requirements. The contractual arrangements also cover the maintenance arrangements for the CCPBs, and include a range of performance benchmarks that are to be met. However, operational aspects of the in-service support (ISS) arrangements are yet to develop sufficient maturity. In this regard, the initial application of the ISS has resulted in the identification of a number of areas of contention between Customs and the contractor that will require resolution.

13. Over recent years, Customs has encountered challenges in fully crewing the existing Bay Class patrol boat fleet due to a number of resourcing and operational issues. This challenge is reflected in the progressive decline in the achievement of patrol boat effort. In approving the CCPB acquisition in May 2010, the Government required Customs to maintain the level of patrol boat fleet effort at 2400 patrol days per annum. In 2013–14, the level of patrol boat effort totalled 1847 patrol days. In this regard, program estimates highlight that after 2014–15, the CCPB program’s operating budget (which is set internally by Customs) to cover crew, fuel and maintenance costs, will be insufficient to meet expected operating costs for the CCPB fleet. To manage the program’s budget and meet the commitment to maintain the fleet effort at agreed levels, Customs will need to develop a clear resourcing strategy to inform its forward planning, including contingency arrangements. Further, the development of a medium to longer-term strategic workforce plan would provide greater assurance that future marine workforce challenges have been identified and clear approaches are in place to address this area of high risk in relation to sufficient patrol boat crew.

14. To support the ongoing management of the CCPB program, the ANAO has made two recommendations for Customs to: develop a clear strategy to address expected CCPB operational funding shortfalls; and develop an appropriate marine unit strategic workforce plan to address medium to longer-term workforce requirements.

Key findings by chapter

Capability development and approval processes (Chapter 2)

15. On-water patrol and response activities are the primary means of enforcing civil maritime security, with Customs a key contributor to the patrol and response system. The growing challenge in controlling and managing Australia’s maritime zones was highlighted in a 10-year strategic plan endorsed by the Government in 2009, which established the basis for acquiring new patrol vessels with a greater capability to operate much further from shore.

16. In establishing the CCPB program to manage the acquisition of the new vessels, Customs has demonstrated the sound use of a number of processes similar to those employed by Defence. This has included a fundamental inputs to capability (FIC) model to manage the inputs that are required for a fully functioning CCPB fleet (involving the vessels, workforce, support systems, safety management, operational command and organisational arrangements)5 and the development of detailed documentation concerning the vessel’s planned performance (for example, patrol range and duration, sea handling ability, and accommodation for transportees). Importantly, lessons from the RAN’s experience with the acquisition of the Armidale Class patrol boats were integrated by Customs into the design of the CCPBs and the construction schedule.

17. Customs undertook a number of industry engagement exercises early in the program to help in determining likely costs and to assess industry capability in regard to undertaking a patrol boat construction program. While the number of industry participants contributing to these exercises was limited in some areas, industry engagement assisted Customs to refine its cost estimates to procure an enhanced patrol boat capability, prior to formally approaching the market.

18. The formal approach to the market was conducted through an RFT in July 2010, with a sound tender evaluation regime and a transparent process to identify a preferred tenderer. The RFT was characterised by strong management involvement and an effective review and approval process that ensured that management was regularly informed of the status of the evaluation and negotiation activities.

19. In terms of the value for money outcome, the acquisition of the enhanced vessel option was assessed as best meeting the capability requirements, as defined in civil maritime capability planning documentation. The capability was achieved through utilising an open approach to market that delivered an acceptable solution within a target price based on similar acquisitions. Further, the acquisition schedule was intended to align with the planned disposal of Customs’ Bay Class patrol boats. The achievement of a value for money outcome in relation to the procurement of the CCPBs does, however, rely upon successful delivery and integration with other inputs to capability including: the recruitment of additional crew and upgrading existing workforce skills; the effective operation of new ISS arrangements; and availability of appropriate infrastructure support arrangements for the CCPBs. Once the CCPB fleet and support systems are completed and the vessels have been operating for some time, the extent to which an overall value for money outcome has been achieved from the CCPB program will become clearer.

Design and build contract (Chapter 3)

20. Customs has drawn upon contracting and engineering processes similar to those employed by Defence to effectively manage the vessel design and build aspects of the CCPB program to date.

21. Customs established appropriate acquisition contract terms, with most of the $277.7 million contract price set on a firm price basis. The acquisition budget made provision for allowances to cover the proportion of the contracted price that was subject to foreign exchange exposure. Further, contract payments are linked to the achievement of 17 major milestones, including at the point of Customs’ acceptance of each CCPB from the contractor.

22. The early phase of the contract has involved the design, testing and evaluation of the CCPBs. Known design risks associated with aluminium vessels (such as areas of aggressive corrosion and fatigue in the form of hull cracking) were identified early to enable considered mitigation strategies as part of the design process. A sound construction schedule to manage design risks was also established. While a number of design risks and issues remain, the outcomes from the operational test and evaluation (OT&E) phase in September 2013 have confirmed to Customs that the first CCPB was capable of meeting critical operational requirements.

23. The contract management arrangements have proven generally effective in managing issues between the contractor and Customs. Nevertheless, a significant outstanding issue concerns the absence of an approved contract master schedule (CMS). The purpose of the CMS—which is to be developed by the contractor—is to provide Customs with visibility concerning the tasks required to achieve key milestones. While Customs has established an alternative arrangement to monitor contract progress, this is a less satisfactory outcome.

Program management (Chapter 4)

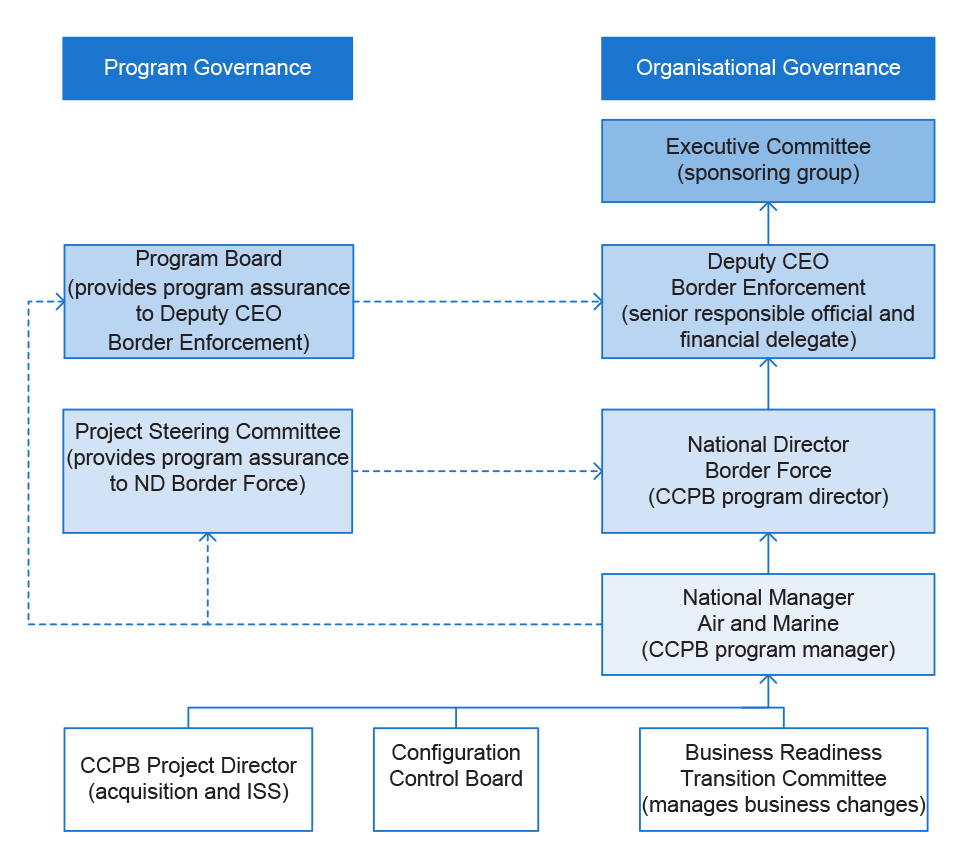

24. A sound management framework, incorporating effective governance and assurance arrangements, provides a strong basis for the overall success of a program. Customs established a high level board that provides strategic program assurance to Customs’ senior management, and a more technically oriented project steering committee that provides assurance to the program’s national director. These assurance arrangements have been augmented by a number of external reviews, including the Department of Finance’s Gateway Review Process (since February 2009) and reviews on the acquisition process (March 2013) and workforce planning (June 2013) by Customs internal audit. In this regard, while the CCPB acquisition element of the program has well-developed planning documentation, the elements of the program beyond the immediate transition of the CCPB fleet, including important areas such as strategic workforce planning, have not been well articulated.

25. The progressive introduction of the CCPB fleet has significant additional resource demands on the CCPB program’s operational budget. When approving the CCPB acquisition in 2010, the Government required Customs to find savings from within the agency’s budget to offset the additional costs to operate the CCPB fleet, above those costs of operating the Bay Class patrol boat fleet—and a funding shortfall has been identified. In this context, a clear resourcing strategy to address the expected shortfall in the CCPB program’s operational budget after 2014–15 should be developed by Customs, including contingency arrangements in the event that shortfalls are not budgeted.

26. Customs has adopted an active approach to risk management for the CCPB program, although the operation of two risk registers separately covering CCPB acquisition and transition activities reduces the clarity in whole-of-program risk management and reporting. To address this issue, there would be benefit in Customs adopting a single risks and issues register to provide greater assurance in relation to risk identification, reporting and management.

27. Despite considerable planning to mitigate a number of known high risks with the CCPB design, the first vessel suffered a mechanical failure of the propulsion system three months after operational release in September 2013 due to aggressive corrosion in a stern tube that partly encases a propeller shaft. While a detailed monitoring program has been established, this remains a key program risk in the immediate term for vessel performance. In this regard, many design risks and issues with the CCPBs are not unique to Customs’ fleet of aluminium patrol boats. There would be benefit in Customs exploring options for more structured and ongoing engagement with key stakeholders across the aluminium shipbuilding industry (including shipbuilders, maintenance providers and vessel operators), to help support the planned operational life of the CCPBs and other aluminium patrol boat fleets operated by the Commonwealth.

28. The CCPB program was established as a major competitive procurement with a detailed assessment process by the entity. Customs implemented a number of sound probity controls, including procurement oversight by an independent probity advisor. However, arrangements for managing conflicts of interest were not clearly documented and a conflict of interest register was not maintained. Further, the final probity report for the acquisition stage of the program was not completed. In the context of the overall probity of the procurement process, allegations were raised by a Customs officer regarding bias towards a particular ship builder early in the process. Customs conducted two separate investigations (a criminal investigation and an Australian Public Service Code of Conduct investigation) that found that the allegations were not supported by the evidence.

In-service support and transition (Chapter 5)

29. The CCPB program contracting arrangements established responsibility for construction of the vessels and initial ISS (until August 2019) under one contractor. Customs has designed a sound ISS framework to manage the maintenance of the vessels, including performance benchmarks to be met by the contractor. Nevertheless, with less than half the CCPB fleet having entered the ISS phase by September 2014, operational aspects of the ISS are yet to reach sufficient maturity. In this regard, the initial application of the ISS arrangements has resulted in the identification of a number of areas of contention between Customs and the contractor that require resolution. For example, Customs and the contractor have not reached agreement on the number of days the first CCPB was unavailable due to a stern tube failure in late 2013 and, therefore, the level of financial claim that may be available to Customs under the ISS performance management regime.

30. The transition from the Bay Class patrol boat capability to the enhanced CCPB capability also represents a significant program management and logistical challenge for Customs. In particular, Customs has identified the availability of qualified personnel to crew vessels as the single largest risk to its capability upgrade program. In this regard, a significant expansion in patrol boat crew numbers (from around 200 officers to over 300 officers) and a more qualified workforce is required to deliver the operational capabilities of the CCPBs. As Customs has encountered challenges in fully crewing the Bay Class patrol boat fleet due to a number of workforce operational and resourcing issues, the level of patrol boat effort has been progressively decreasing since 2009–10. In approving the CCPB acquisition in May 2010, the Government required Customs to maintain the level of patrol boat fleet effort at 2400 patrol days per annum. In 2013–14, the level of patrol boat effort totalled 1847 patrol days.

31. Further, while an extensive array of workforce preparation initiatives has been undertaken, this has not been informed by an appropriate strategic workforce plan for addressing the patrol boat crewing requirements over the medium to longer-term.6 The integration of such plans with fit-for-purpose operational plans would provide greater assurance that future marine workforce challenges have been identified and clear approaches are in place to address this area of high risk.

32. An additional input to the CCPB’s operational capability concerns infrastructure support. As with the Bay Class patrol boats, the CCPBs operate from existing commercial and/or Defence marine facilities, rather than a dedicated base or facility. The vessels’ main operating location is the port of Darwin. Infrastructure limitations at Darwin, particularly access to secure berthing arrangements in an emergency, have added to the logistical complexity for Customs in managing its patrol boat fleet. While various berthing options in Darwin have been investigated (for example, a floating pontoon arrangement), a suitable long term solution has yet to be established.

Summary of agency and program participant responses

33. Customs’ summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) has welcomed the scrutiny of ANAO in this important program. The findings and recommendations are not unexpected and are entirely consistent with other reviews to which this Program has been subjected. In particular, the Program has undergone five Gateway Reviews as part of the Gateway Review process conducted on large-scale programs by the Department of Finance, two internal audits and six quality system audits. Of the five Gateway Reviews, four Reviews have assessed that successful delivery of the Program to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation appears highly likely. The program has also received two Achievement Awards from the Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM).

The success of the program has been built on robust systems engineering principles; procurement processes; and, program management methods and techniques. The systems engineering approach ensured comprehensive requirements development, accurate translation into specifications, thorough design reviews and comprehensive testing to ensure that operational requirements were met.

A clear and deliberate procurement strategy that was in compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines and which was facilitated by the best practice ASDEFCON templates developed by the Department of Defence, has delivered an excellent capability and a clear value-for-money outcome.

To facilitate program delivery and, hence, capability realisation, the Program developed its own version of the Fundamental Inputs to Capability Model (FIC). The audit appropriately identified a shortcoming in the “workforce” FIC element, insofar as workforce planning has not yet completely addressed longer term workforce arrangements. Strategic workforce planning commenced with the ACBPS Reform Programme and is now part of the “Blueprint for Integration” of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the ACBPS, with the workforce model being incorporated into arrangements for the new Australian Border Force.

The only other notable shortcoming identified by the audit pertained to a known shortfall in operational funding that will need to be addressed by ACBPS in the next budget cycle.

Overall, ACBPS remains confident that this Program will successfully deliver a critically important component of Australia’s Civil Maritime Security System.

34. Austal Ships’ covering letter in response to an audit extract is reproduced at Appendix 2.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 4.14 |

The ANAO recommends that, given the CCPB program’s estimate that CCPB operational costs are likely to exceed its available operational budget, the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service develops a clear strategy to address the estimated operational funding shortfalls, including contingency arrangements. Customs’ response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 5.47 |

The ANAO recommends that, to improve marine unit workforce planning, the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service develops an appropriate strategic workforce plan to address future workforce requirements. Customs’ response: Agreed |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides an overview of the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs) Cape Class patrol boat program, which involves the delivery of eight vessels and a support system to replace the existing Bay Class patrol boat fleet. It also sets out the audit approach.

Introduction

1.1 The maritime security policy governing patrol boat operations by Customs was established in the Australian Civil Maritime Security Capability Plan, which was endorsed by the Government in November 2009. The plan provided guidance for maritime security planning to 2020 and included a number of key performance requirements for patrol boat operations that were beyond the capabilities of Customs’ existing Bay Class patrol boat fleet. At that time, the Bay Class patrol boats were also entering the latter stages of their planned 10-year operational life. The key capability requirements under the plan included:

- range (ability to transit to and conduct patrols within the outer limits of Australia’s maritime zones in all weather conditions throughout the year);

- endurance (ability to conduct 24 hour per day operations for the duration of a patrol);

- communications and surveillance (ability to receive and share information with other supporting vessels and aircraft via interoperable systems);

- accommodation (transport of government officers, passengers or transportees in compliance with safety and legal requirements);

- vessel operations (ability to undertake a range of activities, including vessel interception, search and rescue, and marine pollution responses); and

- workforce skilling (projects to improve staff resourcing and skills development).

1.2 In response to the planned capability requirements, in the context of the May 2010 Federal Budget the Government approved funding of $573.6 million over 10 years (2010–11 to 2019–20) for the acquisition and operating costs (including crew, maintenance and fuel costs) of new patrol boats to replace the Bay Class patrol boat fleet—the Cape Class patrol boats (CCPBs). Over the 10 year period, the Government required Customs to offset approximately 90 per cent of the additional operating costs associated with the CCPBs, compared to the Bay Class patrol boats, from within Customs’ internal allocations. The Government also required that the replacement vessels maintain a patrol function of 2400 sea days per annum across the fleet.

1.3 In general, the process used by Customs to refine the operational requirements for replacement patrol boats was similar to that employed by the Department of Defence (Defence), including operational concept documentation and subsequent detailed vessel specifications. The development of the detailed specifications was informed by advice from industry, prior to formally approaching the market to acquire the vessels through an open request for tender (RFT) in July 2010. The RFT set out a significantly enhanced patrol boat capability compared to Customs’ existing Bay Class patrol boats. Three companies responded to the RFT. Two of these companies entered the contract negotiation phase, with final negotiations concluded with a single tenderer.

Cape Class patrol boat acquisition and operation

1.4 A contract for the acquisition of eight aluminium patrol boats and in-service support (ISS) was signed on 12 August 2011 between the Commonwealth (represented by Customs) and the prime contractor (Austal Ships Pty Ltd, based at Henderson in Western Australia). The total budget for the acquisition was set at $316.5 million over the period 2011–12 to 2015–16. This included $277.7 million in acquisition contract milestone payments to the contractor. The remaining budget covers the costs of: government furnished material7; foreign exchange risk; and an allowance for design/equipment changes and rectification work.

1.5 The contract also included the prime contractor’s provision of ISS to the CCPBs until mid-20198, which involves fixed costs of $63.4 million. Customs has estimated other likely costs relating to the provision of ISS services, but these costs are commercially sensitive and have not been publicly released.

1.6 The agreed schedule for acceptance of the eight vessels extends from 1 March 2013 to 31 August 2015. The first vessel, Australian Customs Vessel (ACV) Cape St George (shown in Figure 1.1) was accepted on 17 April 2013, which was slightly later than planned. The second vessel was accepted one month ahead of the planned acceptance date, and the third vessel was accepted on the planned acceptance date.

Figure 1.1: Cape Class patrol boat – ACV Cape St George

Source: Austal Ships Pty Ltd.

1.7 The acceptance schedule included a break of more than 12 months between the first CCPB and the second vessel. This schedule incorporated a six month vessel build pause under the contract, which was intended to capture and address design issues arising from the operational test and evaluation of the first CCPB, before construction commenced on the second vessel. Data provided by Customs shows that, as at September 2014, the contractor’s vessel production schedule for vessels four to eight was generally in-line—within a few weeks—to meet the planned acceptance schedule as detailed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: CCPB acceptance schedule

|

CCPB Number |

Name |

Planned Acceptance Date |

Actual Acceptance Date |

|

|

CCPB#1 |

Cape St George |

1 March 2013 |

17 April 2013 |

|

|

CCPB#2 |

Cape Byron |

16 June 2014 |

19 May 2014 |

|

|

CCPB#3 |

Cape Nelson |

15 September 2014 |

15 September 2014 |

|

|

CCPB#4 |

Cape Sorrell |

15 December 2014(1) |

- |

|

|

CCPB#5 |

Cape Jervis |

2 March 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#6 |

Cape Leveque |

1 May 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#7 |

Cape Wessel |

1 July 2015 |

- |

|

|

CCPB#8 |

Cape York |

31 August 2015 |

- |

|

Source: Customs program documentation.

Note 1: Customs advised that, as at November 2014, acceptance of CCPB#4 is on schedule.

1.8 The ACV Cape St George was subject to a four and a half month operational test and evaluation program to validate the CCPB’s capability against expectations detailed in operational documentation developed by Customs. At the completion of the operational test and evaluation program in September 2013, critical operational matters were assessed as satisfied and the vessel achieved operational release in the same month.

1.9 The acquisition of the CCPBs is one component of a broader program of activities necessary to deliver a fully capable patrol boat fleet. Customs has used elements of Defence’s fundamental inputs to capability (FIC) model (personnel, organisation, collective training, major systems, supplies, facilities, support, and command and management) as a conceptual framework for planning and managing the activities and schedule required to achieve the CCPB’s full capability.9 A key area of planning involves an expansion in crew numbers and training effort to meet regulatory requirements associated with the increased size and capability of the new vessels. The existing Bay Class patrol boat fleet normally operates with 10 crew members per vessel, and an overall workforce size of approximately 200 officers. With the introduction of the CCPB fleet, the larger vessels will normally require a crew of 18 and a total workforce of around 330 officers by 2015–16.

Administrative arrangements

1.10 The acquisition of the CCPBs is managed within Customs’ Border Force Division’s Air and Marine Branch in Canberra. The branch’s CCPB program office operates with around 13 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, and is responsible for oversighting the construction, acceptance and introduction of support systems for the CCPBs. The program office’s resident project team (RPT), located at the contractor’s shipyard in Western Australia comprises a further four FTE staff. The RPT plays an important on-the-ground role for Customs, with key activities including: monitoring the build schedule and any production issues; reviewing design and technical documentation; witnessing testing; and reporting to the program office in Canberra.

1.11 Among other responsibilities, the Air and Marine Branch is managing the withdrawal of the Bay Class patrol boats and the gifting of two vessels each to Sri Lanka and Malaysia, as well as supporting Custom’s Border Protection Command10 by providing air and marine capability, including patrol boats, workforce, and other FIC elements on a day-to-day basis.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.12 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Customs’ management of the Cape Class patrol boat program.

1.13 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- sound capability development and government approval processes were in place to deliver the best value for money;

- the contract arrangements are currently facilitating the delivery of the program at the agreed cost, schedule and performance parameters;

- appropriate governance and program oversight arrangements were in place; and

- suitable arrangements have been established for the future operation of the capability through the ISS arrangements, crew recruitment and training, and the necessary support infrastructure.

Methodology

1.14 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO reviewed Customs’ files and documentation covering the planning and management of the program. Discussions were also held with representatives from a number of organisations, including: relevant Customs staff; past and present independent probity advisors to the program; the prime contractor and ISS sub-contractor; the Australian Maritime Safety Authority; the Department of Finance; and the Defence Materiel Organisation’s patrol boat systems program office.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Audit Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $567 000.

Report structure

1.16 The report structure is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Report structure

|

Chapter Title |

Chapter Overview |

|

Capability Development and Approval Processes |

Examines the processes used to inform Customs’ decision to replace its Bay Class patrol boat fleet. It also examines government approval processes, the approach to market and the value for money outcomes. |

|

Design and Build Contract |

Examines the approach to, and structure of, the contractual arrangements for the management of the CCPB program by Customs. It also examines the processes adopted by Customs to provide assurance in regard to operational and regulatory requirements for the acquired CCPBs. |

|

Program Management |

Examines key elements of the CCPB program that are designed to ensure sound acquisition management and the delivery of a fully capable CCPB fleet. |

|

In-Service Support and Transition |

Examines the support arrangements that are designed to ensure the CCPBs remain operational once they have been placed into service. It also examines workforce arrangements as part of the transition from Bay Class patrol boats to CCPBs, as well as infrastructure requirements. |

2. Capability Development and Approval Processes

This chapter examines the processes used to inform Customs’ decision to replace its Bay Class patrol boat fleet. It also examines government approval processes, the approach to market and the value for money outcomes.

Introduction

2.1 Customs’ fleet of eight Bay Class patrol boats were introduced into service in 1999–2000, with an estimated useful operating life of 10 years.11 The vessels were designed to perform a range of maritime constabulary operations within the coastal and territorial waters of Australia.12 Since the introduction of the Bay Class patrol boats, the civil maritime security environment has become increasingly challenging and the tasks assigned to the vessels involve patrols much further from shore where rougher sea conditions prevail. The demands placed on Customs’ patrol boats had also increased significantly, with the fleet operating at 2400 sea days per year in 2002–03—twice the initial planned rate of effort.

2.2 By 2005, Customs analysis highlighted that structural fatigue in the Bay Class patrol boats was occurring—cracking in the hulls had been identified—and an increased maintenance regime was required. Further, a range of maritime regulatory changes, such as enhanced environmental standards for civilian vessels, also meant the Bay Class patrol boats were not able to meet contemporary regulatory requirements.13

2.3 Against this background, in the May 2006 Federal Budget, the Government provided funding over two years for a project team within Customs to progress preliminary work on the development of options for the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats. Further Budget funding was provided in May 2009 to enable Customs to explore and refine replacement options for government consideration in the May 2010 Budget context.

2.4 The ANAO examined the capability and approval processes used to replace the Bay Class fleet and establish the CCPB program, including:

- the capability requirements development processes;

- early industry engagement to scope industry capability and likely acquisition costs against requirements;

- formal approaches to the market, including request for proposals (RFP) and RFT;

- the arrangements governing negotiations with tenderers;

- the Government’s approval processes; and

- whether a value for money outcome has been achieved through the procurement process.

Capability development

2.5 The Defence Capability Manual 2006 defines capability as:

the power to achieve a desired operational effect in a nominated environment, within a specified time, and to sustain that effect for a designated period. Capability is generated by Fundamental Inputs to Capability comprising organisation, personnel, collective training, major systems, supplies, facilities, support, command and management.

2.6 In the case of the CCPB program, Customs has drawn on this definition and Defence’s FIC model to manage the CCPB program as a system of interdependent elements. The FIC model used by Customs to define the CCPB capability identifies the following six key inputs:

- mission system (eight CCPBs);

- workforce (including crewing, training and recruitment);

- support (including maintenance and facilities);

- safety management (including regulatory requirements for the safe operation of the vessels);

- operational command and management (including standard operating procedures, information management, communications and interoperability with other mission systems, such as Royal Australian Navy (RAN) vessels); and

- organisation system (including overall governance of the program).

2.7 Overall, the FIC model adopted by Customs provides a useful conceptual framework for identifying and managing the inputs required to achieve the CCPB’s full capability.

Capability requirements framework

2.8 In the lead up to the Government’s approval to replace the Bay Class patrol boats in May 2010, a substantial body of work had been undertaken to progressively refine future patrol boat capability requirements for eventual government consideration. However, beginning in mid-2005, a key feature of the early capability requirements development work focused on replacement of the patrol boats, rather than the strategic context/requirements for civil maritime security within which any particular solution needed to be considered. The key milestones in the requirements development framework for replacing the Bay Class patrol boats are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Capability requirements framework timeline

|

Date |

Milestone |

Key Outcome |

|

Jun 2005 |

Customs discussion paper Towards a Future Surface Maritime Capability for the Australian Customs Service |

Identified the need to replace the Bay Class patrol boats. Proposed a modest increase in capability and establishment of a project team. |

|

Mar 2007 |

Bay Class replacement—Options Definition Study |

Industry consultations to assist Customs to develop requirements for the Bay Class replacement prior to an anticipated approach to market. |

|

Sep 2007 |

Strategic Maritime Management Committee (SMMC)(1) consideration of Border Protection Command’s (BPCs) Future Operating Concept |

Examined the future challenges and expected broadening of civil enforcement responsibilities within the maritime domain, and the capabilities required to conduct effective civil maritime patrols. SMMC endorsed BPC’s Future Operating Concept as providing the capability framework for the Bay Class replacement project. |

|

Jun 2008 |

Rapid Prototype Development and Evaluation (RPDE) Workshop |

Industry advice on potential solutions for the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boat, using draft operational concept and performance specification documentation from Customs. |

|

Oct 2008 |

Government consideration of BPC’s Future Operating Concept |

Government noted that refurbishment and replacement options for the Bay Class patrol boats were to be informed by an SMMC review of civil maritime security. Customs was directed to develop a 10 year rolling plan to provide strategic guidance and inform future consideration of long term investment decisions. |

|

Dec 2008 |

Government consideration of SMMC’s review of the Civil Maritime Security System (CMSS) |

Government noted the CMSS and provided approval for Customs to bring forward replacement and refurbishment options for the Bay Class patrol boats for first stage consideration as part of the 2009–10 Budget cycle. |

|

May 2009 |

First stage Business Case approval 2009–10 Budget cycle |

Government approval to progress to second stage consideration of replacement options for the Bay Class patrol boats. |

|

Nov 2009 |

Civil Maritime Security Capability Plan (CMSCP) approval |

Government approved the CMSCP that identified a range of capability deficiencies in the CMSS. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

Note 1: The SMMC, which was chaired by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, was a whole-of-government committee tasked with monitoring the effectiveness of maritime compliance and enforcement operations. The committee reported to the Government on developments and changing priorities in the broader maritime environment. The SMMC was replaced in 2009 with the Homeland and Border Security Policy Coordination Group and Border Management Group. The Secretaries Committee on National Security and the Border Management Group are now the senior officials committees that are responsible for advising government on border protection policy.

2.9 The first step in providing a more strategic framework for considering the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats was the establishment of a whole-of-government Civil Maritime Security System (CMSS), with Customs as the lead agency.14 As outlined in Table 2.1, the CMSS was endorsed by government in late 2008 and comprises a range of assets, resources, activities, policies and legislative arrangements that integrate into a series of core civil maritime security functions.15 A key planning outcome from the CMSS has been the development of an Australian Civil Maritime Security Capability Plan (CMSCP). However, as outlined in Table 2.1, it was only in November 2009 that the Government endorsed the CMSCP, which provided the strategic guidance for planning and investment decisions out to 2020.16 By this time, a significant body of work to develop the Bay Class patrol boat replacement capability requirements, including industry engagement, had been completed. This work was necessary to meet planned timeframes for the decommissioning of the existing Bay Class patrol boats and the consideration of replacement options in the context of two Federal Budget cycles.

2.10 The key operational requirements of the patrol boats established in the CMSCP were identified earlier in Chapter 1 at paragraph 1.1, and were designed to address the capability deficiencies of the Bay Class patrol boats, including: range17; endurance18; surveillance and communications equipment; and the ability to undertake the full range of required activities within the civil maritime patrol function.

Capability options

2.11 In late 2008, the Government directed Customs to develop a CMSCP and provided approval for Customs to continue developing options to either replace or refurbish the Bay Class patrol boats, to enable it to perform its civil maritime enforcement role.

2.12 The three capability options that Customs identified (in consultation with the central agencies)19 and submitted to government for approval were a life-of-type extension (LOTE) as a refurbishment option, and replacement options for the Bay Class patrol boat fleet with a like-for-like (LFL) or an enhanced option.

2.13 The LOTE, LFL and enhanced options were evaluated in the first stage business case submitted to government in early 2009. The first stage business case concluded that the LOTE and LFL options would not provide value for money to government and failed to meet the capability requirements identified as necessary by Customs.

2.14 At this time, a Department of Finance gateway review20 supported Customs’ analysis of the options proposed and stated that the enhanced option would meet the strategic direction and operational requirements. However, the review noted risks relating to the increased crewing numbers required and higher acquisition costs associated with the enhanced option.21 The increased crewing and training requirements associated with the enhanced option are examined in Chapter 5.

2.15 The Government agreed with Customs’ assessment that the LOTE option did not meet key operational requirements, and provided funding in the 2009–10 Budget cycle for Customs to continue to develop the LFL and enhanced options. These options were to be brought forward for second stage consideration in the 2010–11 Budget cycle. The key operational requirements, as identified by Customs, and the extent to which each replacement option would meet these requirements is outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Bay Class replacement options comparison

|

Capability |

Requirement |

LOTE |

LFL |

Enhanced |

|

Range |

>3000 nautical miles |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Speed |

Sustainable 25 knots |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Endurance |

>28 days |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Boarding |

Two ships boats of six boarding party members(1) |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Crewing |

Crew complement sufficient to deploy two boarding parties |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Sea-keeping |

Ability to operate effectively in moderate and survive high sea states |

Poor |

Average |

Good |

|

Communications |

Ability to receive and share information with other supporting vessels and aircraft via interoperable systems |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Accommodation |

Ability to accommodate crew and provide austere accommodation for transportees |

10 crew +12 transportees |

16 crew +24 transportees |

18 crew +50 transportees |

|

Towing capacity |

Ability to tow a similar size vessel or a number of smaller sized vessels |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Growth margins |

Sufficient to cater for changes to regulatory regimes and future capability needs |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Surveillance |

Ability to detect and track suspect vessels at sufficient range for overt and covert operations |

Partial |

Partial |

Yes |

|

Protection and offensive capabilities |

Ability to deploy lethal and non-lethal self-protection measures |

No |

Partial |

Yes |

Source: ANAO analysis of Bay Class patrol boat replacement, first and second stage business cases (February 2009 and February 2010), and Solicitation Evaluation Report for Request for Proposals, November 2009.

Note 1: Ships boats are utility boats carried by the larger vessels to perform various roles. The CCPBs carry two 7.3 metre ships boats. The boats’ primary role is to facilitate boarding, surveillance and interception duties.

Industry engagement

2.16 Industry engagement occurs throughout the requirements definition, delivery, and ISS phases of large and complex acquisition projects. The early engagement of industry to help assess commercial interest and capacity is generally encouraged and is a useful mechanism for mitigating many of the risks associated with industry’s ability to successfully deliver a large and complex acquisition project. As outlined earlier, Customs refined future patrol boat capability requirements, in consultation with industry, prior to the development of a strategic framework for civil maritime security.

2.17 Initial industry consultation took place prior to any formal approach to market through a Customs funded options definition study (ODS). The ODS was conducted with four companies that Customs had identified as having a track record in delivering similar projects. The ODS commenced in December 2006 and responses from companies invited to participate were submitted to Customs in March 2007.

2.18 The aim of the ODS was to obtain sufficient information from the companies invited to participate to enable Customs to further develop and refine the requirements for a replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats. It was also designed to obtain indicative costings prior to an anticipated approach to market—upon government approval of the second stage business case.22

2.19 In June 2008, Customs approached the Rapid Prototype Development and Evaluation (RPDE) organisation23 to conduct a workshop for companies interested in participating in the Bay Class patrol boat replacement project. Through the conduct of the workshop, Customs sought specialist industry assessments and advice for the replacement project. Participants reviewed initial project documentation developed by Customs, including the operational concept document (OCD) and functional performance specifications (FPS).24

2.20 The conduct of the RPDE workshop demonstrated that there was sufficient capacity, capability and expertise to meet the proposed replacement vessel capability requirements as outlined by Customs. In addition, the RPDE workshop also assisted Customs to: refine its requirements; assess the level of industry interest; and identify major cost drivers and constraints associated with the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats.

2.21 As part of the RFP and RFT approaches to market (discussed later), opportunities were provided for industry engagement through industry briefing sessions held in July 2009 and August 2010. These briefings were open to companies that had registered their interest in participating prior to each session in accordance with the RFP and RFT documentation released on Austender.

2.22 As part of the RFP and RFT industry briefings, Customs provided opportunities for companies to attend one-on-one briefing sessions, where commercial-in-confidence information could be disclosed in a secure environment. The probity advisor attended each one-on-one session, with the matters discussed recorded.

2.23 Overall, the approach adopted by Customs to engage industry was comprehensive and undertaken at appropriate stages prior and subsequent to the release of the RFP and RFT to industry. This consultation informed Customs’ development and refinement of capability requirements for the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats and assisted in the development of cost estimates that were sufficiently robust to include in the business cases submitted to government for consideration and approval. The level of industry consultation and engagement was appropriate for a large and complex project.

Approach to market

2.24 At the time of the commencement of the procurement phase of the CCPB program, the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 and Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs)25 established the Government’s procurement policy framework.26 Among other things, the CPGs required all procurements above pre-determined thresholds that were not subject to an exemption to be competitively tendered.

2.25 As a major capital acquisition, a two stage approach to the market for the CCPB acquisition was adopted, with an RFP followed by an RFT. These approaches to market were informed by advice obtained from the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS).27

Requests for Proposal

2.26 As part of the May 2009 Federal Budget, the Government provided approval for Customs to further develop the LFL and enhanced options for replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats. Subsequently, Customs issued through Austender an RFP seeking industry responses for each of the replacement options. The RFP opened on 23 June 2009 and closed on 17 September 2009.

2.27 The aims of the RFP process were to:

- engage industry as part of a two stage acquisition process that would be followed by a select or open RFT;

- determine likely costs of two possible capability solutions for the Bay Class replacement vessel prior to seeking government approval for a funded acquisition; and

- inform Customs about any future ISS arrangements for each option.

2.28 Interested companies were advised that they could provide a response to either the LFL or enhanced option, or both. During the RFP period, 24 addendums were issued, the majority of which were minor administrative/clarification of detail amendments. There were, however, two changes that were significant in nature.28

2.29 Customs’ evaluation of the responses to the RFP was conducted in accordance with the criteria disclosed in the conditions of proposal and Customs’ solicitation evaluation plan (SEP). The SEP outlined a detailed evaluation governance framework, which included utilising specialist project management, engineering, operational, financial and commercial working groups to evaluate the relevant sections of RFP responses. The working groups were comprised of internal project staff, with appropriate skills and expertise and external consultants with specialist skills not available internally to evaluate responses. In addition to the working groups, the independent probity advisor was used to provide oversight of the evaluation process. Specialist legal, technical and financial advisors were also nominated and advice sought on an ‘as required basis’. The working groups reported to an evaluation board, and recommendations were made in the form of a solicitation evaluation report (SER) on the merits of the responses received. The SER was then submitted to the project steering committee (PSC) for endorsement and to the program board and agency delegate for approval (program governance and assurance arrangements are outlined at Figure 4.1 in Chapter 4).

2.30 While Customs informed the ANAO that it had expected a number of responses to the RFP, only one company responded. Nevertheless, Customs has advised that, based on existing knowledge and further insights gained through the RFP process, it was able to state in the SER that there was industry interest, capacity and capability to successfully deliver a fleet of vessels that would substantially meet the capability requirements of the LFL and enhanced options.

2.31 With only one company responding to the RFP, the costing data obtained through the exercise was insufficiently robust to inform the project’s second stage business case to government. Customs used the RFP data that was obtained from the company that responded and benchmarked this against: the contracted price to Defence for the Armidale Class patrol boats; a project undertaken by the United States Coast Guard to replace its fast response cutters; and the price offered by one of the firms that responded to Customs’ 2007 options definition study for the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats.

2.32 In general, companies considered that the RFP process was a costly activity, with one company that considered responding to the RFP advising Customs that:

Given (i) the significant design effort required to offer solutions to within ±10% of final price, (ii) the absence of any indicative budget, and (iii) the need to develop and offer two options ahead of any decision by Government as to the preferred option, [the company] does not believe it can provide a competitive proposal that would currently meet Customs requirements.

2.33 Additional industry feedback obtained by the ANAO in May 2014 also highlighted that industry considered that it needed to address both capability options within the three month timeframe of the RFP to maximise the chances of progressing to the next stage in the procurement process. The cost to industry of responding to two capability options was considerable, with one company advising the ANAO that:

The bid cost for the RFP was in the seven figures, and was approximately five times the cost of a usual tendering activity. It was the largest tendering activity undertaken by the company to date.

2.34 Overall, while the RFP exercise was useful, the low response rate (one response) diminished its value. The low response rate has been attributed to the cost of participating in the RFP. An industry perception was that two complete solutions (LFL and enhanced) needed to be provided in order to progress to the next stage of the planned procurement. To address the limited costing data obtained from the RFP activity additional data was, however, sourced by Customs from alternative approaches to market, and costings provided via early industry engagement and consultation.

Request for Tender

2.35 The RFP exercise was followed by a further approach to market through an open RFT process.29 The RFT was released through Austender on 30 July 2010 and closed on 22 October 2010.30 The RFT sought responses from industry for the acquisition and ISS for a fleet of eight vessels to patrol against, and respond to, civilian threats to Australia’s maritime domain. During the course of the RFT, 17 addendums were issued, only one of which was significant.31 Three responses to the RFT were submitted by the closing date.

2.36 The evaluation of the responses received was conducted in accordance with the criteria disclosed in the conditions of tender and Customs’ tender evaluation plan (TEP). The TEP established a detailed evaluation governance framework, which included specialist engineering, operational, financial and commercial working groups to evaluate the relevant sections of RFT responses. The working groups reported to an evaluation manager, and ultimately the PSC. Further, the probity adviser was actively engaged in the oversight of the evaluation process, and delegate approval and endorsement of the outcome of each stage of the evaluation process was obtained.

2.37 The TEP outlined a detailed approach to the evaluation of RFT responses, following: initial screening of responses in Stage 1; a metric based assessment methodology to calculate technical merit scores and total cost of ownership in Stage 2; value for money indices in Stage 3 for each tenderer; and risk assessment in Stage 4 of the tender evaluation. The risk assessment stage included an adjustment methodology whereby the assessed risk profile of each tender response that had not been excluded or set aside at the end of Stage 3 was independently assessed.

2.38 A sound tender evaluation regime and a transparent process to identify a preferred tenderer was utilised by Customs. The tender evaluation report was completed and formally endorsed by the agency’s delegate (Senior Executive Service Band 3) in February 2011. The report recommended setting aside one response due to technical and cost deficiencies, with the two remaining respondents demonstrating sufficient technical merit for each to enter into the negotiation phase with Customs. Broadly, one respondent was offering an aluminium vessel and the other respondent was offering a steel vessel.

Negotiation phase

2.39 The approved contract negotiation strategy proposed a two stage approach32, and sought to commence parallel negotiations with the two tenderers that were assessed as offering similar value for money outcomes.

2.40 The critical issues identified for negotiation were design related for one tenderer and affordability in relation to the other. A target price of $280 million (firm price) was set by Customs for the acquisition of the CCPBs, based on the funding approved by government in the May 2010 Federal Budget ($316.5 million), inclusive of allowances for likely cost increases as a result of design changes and forecast price escalation. In order to achieve the target price, Customs’ negotiation team was given authority to consider proposals that amended non-essential technical requirements and commercial and schedule arrangements within predefined limits.

2.41 Negotiations with the two shortlisted tenderers commenced in February 2011 and were planned for completion by early May, with a contract to be signed by late May 2011. Negotiations with one respondent progressed until April 2011, when the company advised Customs that it would withdraw from the process. This resulted in negotiations continuing with the remaining respondent. By July 2011, critical design issues had been resolved, resulting in an acceptable offer within the target price, although a number of high risk items requiring ongoing monitoring (for example, the high risk of stern tube corrosion—which is examined in Chapter 4) were identified. A negotiation report approved by the agency delegate made a number of recommendations, including that the Commonwealth enter into a contract for the acquisition and ISS for a fleet of enhanced vessels for a period of eight years.

2.42 Overall, the RFT process was well managed by Customs. The outcome was transparent, utilised sound governance arrangements, and was managed in accordance with approved plans. A range of expertise outside the immediate program was utilised to assist with the evaluation, including AGS advice at key points throughout the evaluation process. The RFT utilised a sound reporting regime, integrated with appropriate probity oversight. The outcome of each stage of the RFT was submitted to the agency delegate for endorsement, with approval sought to progress through each stage of the evaluation and into the negotiation phase.

Government approval process

2.43 In September 2007, the SMMC had established that the Bay Class patrol boat replacement project would be subject to a two stage approval process, similar to that used in Defence for major capital acquisitions. More specifically, in August 2008 the then Prime Minister directed that the project would be subject to the Government’s two stage capital works process.33 As a consequence, the CCPB program was considered in the context of two Federal Budget cycles (2009–10 and 2010–11) and was required to obtain National Security Committee of Cabinet approval, in addition to Expenditure Review Committee of Cabinet approval. The review processes that were stipulated for the CCPB program were novel, both for Customs and the central agencies advising government on a non-Defence, but Defence-like project.

2.44 As an early part of the Government’s consideration process, the CPGs required Customs to consider the use of a Public Private Partnership (PPP) to procure the proposed replacement vessels. As the procurement of the replacement Bay Class patrol boats was estimated to substantially exceed the $100 million PPP threshold (now $50 million threshold), a business case needed to be developed.34

2.45 In February 2008, a Customs examination of PPP options concluded that, although the replacement Bay Class patrol boat project was rated suitable for a PPP approach, it was unlikely to provide superior value for money over a traditional procurement approach.35 Customs, therefore, proposed that a traditional procurement approach be utilised rather than a PPP arrangement. The proposed procurement approach was incorporated into the first stage business case, which was agreed by the Government.

Government decisions

2.46 The first stage business case for the Bay Class replacement project was included in Customs’ 2009–10 submission for the Federal Budget. The submission included: an analysis of the need to replace the Bay Class patrol boats; the proposed procurement approach vis-à-vis a PPP or traditional procurement; and provided costing estimates for two replacement options and a refurbishment option. As outlined earlier, the Government agreed to Customs continuing to develop two replacement options—LFL and enhanced options—utilising a traditional procurement approach.

2.47 The second stage business case was included in Customs’ 2010–11 submission for the Federal Budget. The submission provided an overview of the CMSS and the extent to which each of the two options contributed to the achievement of the key requirements of the system. The submission also reported on the outcome of the RFP process and advised that an enhanced option provided government with the best value for money. The estimated cost impact of each option is outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Second stage business case ten year cost estimates

|

Cost Element |

LFL Option $m |

Enhanced Option $m |

|

Vessel acquisition |

249.8 |

316.5 |

|

Personnel |

69.9 |

85.4 |

|

Operating |

110.8 |

159.8 |

|

ACV Triton retention |

243.0 |

67.5 |

|

Total cost over 10 years (2010–11 dollars)(1) |

673.5 |

629.2 |

Source: Second stage business case.

Note 1: The total cost includes the cost to retain the offshore support vessel ACV Triton across the ten year period. Under the enhanced option, the operation and cost of retaining the ACV Triton was planned to cease in 2013–14.

2.48 The enhanced option involved a significantly larger and more capable vessel. In this context, key cost elements are greater than the LFL option. The increased personnel cost for the enhanced option is attributed to the increased numbers of crew per vessel, while operating cost increases are attributable to fuel and maintenance. On a simple cost basis, the enhanced option only represented a lower cost option over a ten year period on the basis that the ACV Triton was phased out from operations in 2013–14. In August 2014, Customs informed the ANAO that due to an increase in operational requirements, the planned retirement date for the currently leased ACV Triton is December 2014—12 months after the originally planned date used to cost the enhanced vessel option in the second stage business case.36

2.49 In the May 2010 Federal Budget, the Government agreed to fund the acquisition of the enhanced vessels ($316.5 million) and over the forward estimates period (2010–11 to 2013–14) provided $52.4 million for personnel and operating costs. The funding approval across the major cost elements is outlined below at Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Bay Class replacement vessels – government funding approval (May 2010) by cost elements

|

Cost Elements |

Forward Estimates (2010–11 to 2013–14) $m |

Ten Year Costing (2010–11 to 2019–20) $m |

|

Vessel acquisition |

228.7 |

316.5 |

|

Personnel and operating |

52.4 |

257.1 |

|

Total funding |

281.1 |

573.6 |

Sources: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

2.50 The net effect of the funding provided by the Government is that Customs was required to find the majority of the increased personnel and operating costs to operate the vessels from within the agency’s existing budget. The additional funding required to operate the CCPB fleet is significant (approximately 40 per cent higher than the operating cost of the Bay Class patrol boat fleet), and Customs is yet to develop a clear strategy to address the expected funding shortfall, including contingency arrangements. CCPB program estimates regarding the future CCPB operational costs and budgets are examined further in Chapter 4.

Value for money

2.51 The achievement of value for money is the core principle underpinning Australian Government procurement. In this regard, the CPGs that were current at the time of the CCPB program’s approach to market, provided that procurements should:

- encourage competition and be non-discriminatory;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth; and

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision making.

2.52 Officials involved in the procurement were also required to consider factors including: fitness for purpose; supplier performance history; risk profile of proposals; and direct and indirect whole-of-life cycle costs.

2.53 The ANAO examined the value for money outcomes achieved through the procurement process, with a focus on competition and the use of government resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner.

Encouraging competition

2.54 The Bay Class patrol boat replacement was conducted through an open, competitive tender process. Prior to formally approaching the market through an RFP/RFT process, Customs consulted with industry, including: a direct approach to four companies in 2007 to assist in developing the requirements for the CCPB program; and the use of the RPDE organisation in 2008 to gain industry assistance in the identification of the most significant cost drivers from a design perspective. These exercises provided industry with an awareness of a possible future approach to market. Program records also highlight that Customs was aware of the importance of generating strong industry interest in the project in order to encourage a number of competitive submissions. In this regard, Customs informed the ANAO that it had anticipated receiving around four responses to the RFT, with three companies ultimately responding. As outlined earlier, of the three responses received, only one company remained at the final stage of negotiations for consideration by the delegate.

2.55 The competitive basis for the procurement also needs to be considered against the ‘entry’ requirements established by Customs, set out in the RFT. This included that the vessels were to be based on a proven design37 from a ship builder with a proven record in the construction of the type of vessel. These requirements reflected Customs’ approach to reducing some of the areas of key procurement risk38, which was not unreasonable given the importance of managing the program to a fixed budget.

Efficiency and effectiveness

2.56 As a large and complex procurement, the acquisition process was conducted in a generally efficient manner. Customs was able to achieve government consideration and approval of the CCPB program across two sequential budget cycles. Similar Defence procurements have been given a minimum of two years to progress from the first stage business case consideration to the second stage business case approval by government.39 Once the CMSCP was endorsed in November 2009, a strategic framework to support replacing the Bay Class patrol boats with an enhanced vessel was established. This approach facilitated the timely progression of the procurement to the RFT stage in July 2010, a negotiation phase with tenderers between February and July 2011, and final progression to contract signature in August 2011.

2.57 While delivery of the CCPB fleet is still underway, the procurement process has been effectively managed by Customs, with the vessels largely delivered to the capability requirements. Customs has advised that the CCPBs delivered have met all regulatory requirements and, where required, have obtained relevant exemptions necessary to meet operational requirements. Following considerable design work, the operational test and evaluation of the first CCPB (examined in Chapter 3) demonstrated close alignment between vessel capability requirements and the performance of the first CCPB. Further, the procurement contract has ensured the acquisition is within the program budget agreed by government, with a delivery schedule that has supported the planned withdrawal of the Bay Class patrol boats.40

2.58 Nevertheless, the achievement of the broader benefits related to the procurement of the CCPBs relies upon successful delivery and integration with other inputs to capability, including: expanded and more skilled crews; the operation of new ISS arrangements; and improved support facilities. With less than half the CCPB fleet in place by September 2014, a number of capability inputs are still to be fully developed and tested on a whole-of-fleet basis. Deficiencies or delays with any of these inputs have the potential to affect the planned operational capability of the vessels, and their ability to deliver the outcomes required by government. The key systems to support the effective operation of the vessels and meet the capability requirements are examined in Chapter 5.

Economy

2.59 The economic rationale for the selection of the enhanced option over the LFL replacement patrol boat option was soundly based, and the case well documented. The inability of the LFL option to meet the operational and performance requirements outlined in the CMSCP and the ability of the enhanced option to meet the range and endurance requirements outlined in the CMSCP supported Customs’ analysis that the enhanced option would provide the best value for money. In considering the value for money of any enhanced capability option, Customs had regard to benchmark costs for vessels in Australia and overseas. The cost of an enhanced patrol boat obtained through the RFP ($39.5 million) was benchmarked against three similar patrol boat capabilities, as indicated in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Vessel benchmark costs

|

Vessel |

Acquisition Cost Per Vessel |

|

Industry early advice (options definition study phase) |

35.0 |

|

RAN Armidale Class patrol boats |

39.9 |

|

United States Coast Guard (fast response cutter) |

46.6 |

Source: Second stage business case.

Note: The comparative vessel cost data in the table should, however, be treated with caution. The data provides a range of costings for vessels broadly similar to Customs’ enhanced vessel proposal. Key variances across the vessels include hull material and operational capabilities.

2.60 The achievement of a value for money outcome for the enhanced option is, however, contingent on Customs’ ability to: ensure sufficient crew and skills are available to perform the range of operational activities planned for the eight CCPBs; retire the ACV Triton as planned (originally December 2013, although at the completion of audit fieldwork this asset was still under contract to Customs); and successfully deliver the remaining FIC elements, such as access to support facilities for the vessels.

Ethical

2.61 Adopting a transparent approach to procurement enables business to be conducted fairly and reasonably. The acquisition process, including: government consideration of the options; project approval and tendering processes were conducted in a manner consistent with the application of procurement policies. Industry was actively engaged from the early phases of the project, with appropriate probity oversight arrangements in place, requiring formal endorsement at key stages. In the context of the overall probity of the procurement process, allegations were raised by a Customs officer regarding bias towards a particular ship builder early in the process. Customs conducted two separate investigations that found that the allegations were not supported by the evidence.41 Overall, procurement governance and probity oversight was appropriate for a project of this size and complexity.

Conclusion

2.62 While there was an initial delay in the development of the strategic framework to support the replacement of the Bay Class patrol boats, Customs’ development of the CMSCP (which was endorsed by the Government in November 2009) provided an appropriate framework to determine the required capability for civil maritime security.

2.63 The level of industry engagement undertaken by Customs was appropriate for a large and complex project. Initially, industry was engaged through a direct approach to known industry representatives. This early engagement was important in assisting Customs to estimate the expected costs to procure an enhanced vessel. The RFP was a less successful approach to market than the RFT as it generated limited input, with the costing information obtained needing to be benchmarked against similar acquisitions both nationally and internationally. These benchmarking activities utilised previous projects of like capability and complexity.