Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Australia's Air Combat Capability — F-35A Joint Strike Fighter Acquisition

The audit objective was to assess the progress of the AIR 6000—New Air Combat Capability project in delivering the required combat aircraft within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters.

Summary

Background and context

1. In successive Defence White Papers since 1976, Australia has outlined its defence strategy, which includes the control of the air and sea approaches to Australia. In this context, the Defence White Paper 2009 stated:

Our military strategy is crucially dependent on our ability to conduct joint operations in the approaches to Australia—especially those necessary to achieve and maintain air superiority and sea control in places of our choosing. Our military strategic aim in establishing and maintaining sea and air control is to enable the manoeuvre and employment of joint ADF [Australian Defence Force] elements in our primary operational environment, and particularly in the maritime and littoral approaches to the continent.1

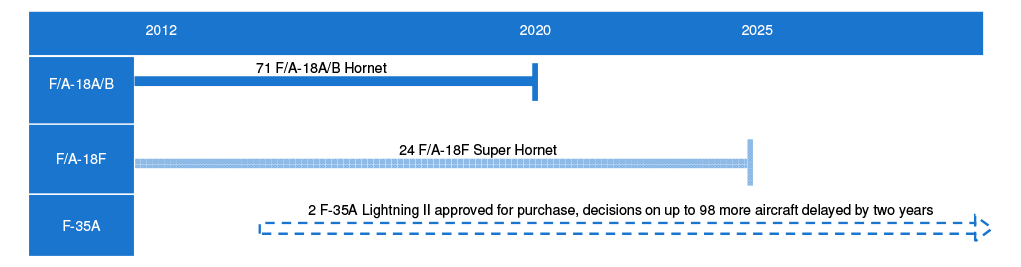

2. This audit provides an Australian perspective on the Australian Government’s participation in the United States of America’s Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program. This program is producing the F-35A Lightning II multi-role combat aircraft selected by the Government to replace the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF’s) 71 F/A-18A/B Hornet aircraft, which at the time of the preparation of this report were planned for withdrawal from service after 2020.2 F-35A aircraft are also planned to replace the RAAF’s 24 F/A-18F Super Hornet aircraft in 2025. The Australian Defence Organisation’s (Defence’s) management of the current Hornet and Super Hornet fleets is the subject of a companion audit, ANAO Audit Report No.5 2012–13, Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability—F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Fleet Upgrades and Sustainment, 27 September 2012.3

3. The New Air Combat Capability project (also known as the AIR 6000 project) was established within Defence in 1999. The Defence White Paper 2000 announced that provision had been made for the eventual acquisition of up to 100 new combat aircraft to replace both the F/A-18A/B and F 111 fleets then being operated by the RAAF. A traditional competitive process was not used to select a new combat aircraft. Rather, in October 2002, the then Government approved Australia becoming a partner in the System Development and Demonstration (SDD) phase of the JSF Program at a cost of US$150 million.

4. The F-35 is a single-seat, single-engine aircraft incorporating low-observable (stealth) technologies, advanced avionics, advanced sensor fusion,4 internal and external weapons, and advanced prognostic maintenance capability. Advanced design and construction features result in the F-35 being a ‘fifth generation’ combat aircraft with a 30-year planned service life and an upgrade path capable of maintaining specified air superiority. There are three F-35 variants, the F-35A conventional take-off and landing (CTOL) variant, the F-35B short take-off and landing (STOVL) variant and the F-35C carrier-suitable (CV) variant.

5. Australia’s decision to join the SDD phase of the JSF Program raised the expectation that Australia, along with the eight other partner nations that contributed to the SDD phase, would later acquire the JSF Program’s F-35 Lightning II aircraft. Australian participation in the JSF Program was planned to provide opportunities for the expansion of Australia’s innovative and technologically leading aerospace industry,5 and, to date, has delivered some A$300 million in contracts to Australian suppliers.

6. In November 2006, the Australian Government formally selected the F-35 to provide the basis for Australia’s new air combat capability.6 In December 2006, Australia became a partner in the JSF Program’s Production, Sustainment and Follow-on Development (PSFD) Memorandum of Understanding, which established the production, acquisition, support, information access and upgrade arrangements for the F-35 aircraft and its support systems.

7. In 2009, the Australian Government approved the acquisition of the first 14 F-35A aircraft at a then-estimated cost of A$3.2 billion. At that time, the Government indicated it would make a decision on the acquisition of an additional 58 aircraft during 2012. The acquisition of these 72 aircraft, in two tranches, was to enable the formation of three RAAF F-35A operational squadrons and a training squadron.

8. The Defence Capability Plan 2012 indicated that a decision about the potential acquisition of a further 28 F-35As, to bring the total to 100, and so enable formation of a fourth F-35A squadron, was not expected before 2015.7

9. In May 2012, the Australian Government announced a two-year delay in acquiring 12 of the first 14 F-35A aircraft.8 The acquisition of the first two aircraft is proceeding as planned, and by June 2012 Defence had signed contracts for the production of long-lead items for these two aircraft that it intends to order when price and availability data are known. The first two aircraft are scheduled for delivery in 2014 and are to remain in the US for testing and training purposes.

10. As at September 2012, and contingent on further government approvals, Australia’s total projected commitment for the acquisition of 100 F-35A aircraft, and for other shared costs under the F-35 SDD and production phases, amounted to US$13.211 billion (then-year dollars).9

11. The US JSF Program Office manages the development, production and sustainment of the F-35 Lightning II aircraft for the US Government, and on behalf of the other eight JSF Program partner nations, including Australia.10 The JSF Program Office, a unit of the US Department of Defense, has personnel from all partner nations located within the program office and employed in various management and technical roles. The JSF Program Office relies on the US Defense Contract Management Agency to manage the acquisition contracts with the JSF Program’s prime contractors, Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney, and on the US Defense Contract Audit Agency to audit JSF contract performance.

Audit objective and scope

12. Given the strategic significance of Defence’s air combat capability, the ANAO considered it timely to examine both the effectiveness of Defence’s arrangements for the sustainment of the F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet fleets that comprise the RAAF’s current capability, and Defence’s progress in securing new combat aircraft to replace the F/A-18 fleets at the end of their lives. Accordingly, as noted in paragraph 2, the ANAO has undertaken two companion performance audits on these subjects. This audit focuses on Defence’s management of the procurement of F-35A aircraft by Defence’s AIR 6000 project through the US JSF Program.

13. Figure S1 shows the planned withdrawal from service of the RAAF’s F/A-18 fleets and the scheduled acquisition of the replacement F-35A fleet.

Figure S1 Air combat fleet schedule for withdrawal from service and acquisition, as at July 2012

Source: ANAO analysis.

14. The audit objective was to assess the progress of the AIR 6000—New Air Combat Capability project in delivering the required combat aircraft within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters. In particular, the audit assessed Defence’s arrangements to ensure that it has adequate insight into the development and production of the F-35A, and information about the status of the JSF Program, to:

- inform progressive acquisition decisions by Government; and

- underpin appropriate contingency planning to avoid any capability gap opening up between the withdrawal from service of the RAAF’s F/A-18 fleets, particularly the F/A-18A/B fleet, and the entry into service of the F-35A-based air combat capability.

15. The audit scope included examining:

- the definition of the F-35A JSF New Air Combat Capability requirements, carried out under AIR 6000;

- the progress achieved by the JSF Program’s System Development and Demonstration (SDD) phase;

- the progress achieved by the JSF Program’s production and sustainment phases; and

- reviews of the JSF Program, and its progress in terms of cost and schedule.

16. As the JSF Program is a US Government undertaking, the ANAO did not intend to, nor was it in a position to, conduct a detailed analysis of the full range of engineering issues being managed within the program’s SDD and production phases. Rather, the audit focused on examining the current status of the F-35 SDD and production phases to underpin an assessment of the progress of Australia’s AIR 6000—New Air Combat Capability project in delivering the required combat aircraft within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters. The audit did not examine total whole-of-life costs of the F-35A aircraft Australia intends to acquire.

17. The audit scope did not include the JSF partner nations’ industrial participation program.11 The Australian Defence Force’s (ADF’s) air combat fleet is supported by Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft, air-to-air refuelling aircraft, lead-in fighter training aircraft, air bases, and command, control and surveillance capabilities.12 These support systems are also not included in the audit’s scope.

18. The audit scope also did not include detailed examination of possible issues arising from the likely extension of the F/A-18A/B fleet’s Planned Withdrawal Date beyond 2020 as a result of the postponement until 2019 of the US F-35 Full-Rate Production decision and the Australian Government’s consequent May 2012 Budget decision to also delay acquisition of the F-35 for two years. The Government was yet to consider these issues at the completion of the audit, but the ANAO did review the planning underway in Defence to advise the Government on options to address them.

19. To gather appropriate evidence to underpin this audit, the ANAO conducted audit fieldwork in both Australia and the US. The Australian audit fieldwork was conducted from October 2011 to June 2012 at the Canberra offices of the New Air Combat Capability Integrated Project Team. The US fieldwork was conducted in March 2012. It included visiting and collecting evidence from the JSF prime contractor, Lockheed Martin; the Defense Contract Management Agency office in Fort Worth, Texas; the JSF Program Office in Arlington, Virginia; the US Department of Defense in Washington DC; and the Defense Contract Audit Agency in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. In addition, the ANAO visited the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), given its role in auditing and providing independent evidence on the JSF Program to the US Government and the Congress.

20. The ANAO’s examination of the current status of the F-35 SDD and production phases included collecting and analysing key project management documents obtained from the Australian New Air Combat Capability Integrated Project Team and from the US Department of Defense’s JSF Program Office. In addition, the ANAO considered evidence provided by a number of US Department of Defense agencies which operate outside the line-of-control of the program office and provide independent advice on the JSF Program to the US Government.13 The ANAO also analysed the GAO’s reports on this program, and other official reports and sworn testimony provided to the US Congress.14 As noted in paragraph 19, the ANAO visited Lockheed Martin and was provided with documents and access to key Lockheed Martin F-35 program executives and managers. Overall, the ANAO was able to interview key personnel responsible for managing the JSF Program or for providing oversight on it.

Overall conclusion

21. Under the JSF Program the US, with its industry partners (in particular Lockheed Martin),15 is developing the F-35 Lightning II aircraft to replace legacy fighters and strike aircraft in its own Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps air combat fleets.16 The cost to the US of F-35 development and production is currently estimated at US$395.7 billion, which makes the JSF Program the most costly and ambitious US Department of Defense acquisition program by a wide margin. Australia and seven other nations have entered into partnership arrangements with the US to satisfy their own combat aircraft needs via the JSF Program.17

AIR 6000–New Air Combat Capability project

22. In 2006, the Australian Government approved the F-35 as the aircraft to provide the basis for Australia’s new air combat capability. This decision was reaffirmed in the Defence White Paper 2009, and late in 2009 the Government approved the purchase of the F-35A Conventional Take-off and Landing (CTOL) variant of the F-35. The F-35A aircraft are to be acquired in a number of tranches, with the Government to progressively approve each tranche.

23. Defence’s AIR 6000–New Air Combat Capability project is undertaking the procurement of F-35A aircraft for the RAAF through the US JSF Program. As the JSF Program is to develop and produce this key component of Australia’s planned new air combat capability, the effectiveness of Defence’s arrangements to monitor and assess its progress in terms of cost, schedule and performance is fundamental to Defence acquiring adequate insight into the development and production of the F-35A. Defence requires appropriate evidence about the status of the JSF Program to inform both progressive F-35A acquisition decisions by the Government and to underpin appropriate contingency planning to avoid any capability gap opening up between the withdrawal from service of the RAAF’s F/A-18 fleets, particularly the F/A-18A/B fleet, and the entry into service of the F-35A-based air combat capability. Accordingly, establishing the Australian perspective on the JSF Program’s progress and the implications of this was a key focus of this audit.

Risks in advanced defence technology development and production programs

24. This audit report draws attention to the wide-ranging cost, schedule and performance risks inherent in advanced defence technology development and production programs, such as the JSF Program. These risks arise from the need to:

- specify products, in function and performance terms, that continue to satisfy requirements at delivery and are capable of being upgraded in line with changing military requirements;

- pay for work on products years ahead of opportunities to verify their compliance with specifications; and

- ensure continuous collaboration across wide-ranging contractual, organisational, geographic and national boundaries, that is capable of completing highly technical work extending over many years, and of coping with unforeseen technical advances or changes in user requirements.

25. The F-35 aircraft are designed for high-threat multi-role operations, requiring advanced stealth technology and fully integrated internal radar and electro-optical sensor systems. The intent is that the F-35 will sense, track and identify targets, and together with target data provided by sources external to the aircraft, fuse this data and present it to the pilot using an advanced Helmet Mounted Display system. As a consequence, the extent of air combat technology development and systems integration being undertaken by the JSF Program is unprecedented. One result is that the US Department of Defense and its contractors have encountered persistent difficulties in accurately estimating the time and cost of developing and operating F-35 aircraft and their support systems.

26. However, the intense, high-level attention given to the JSF Program in recent years, including by the US Congress, has identified a range of issues that were previously impacting on cost, schedule and performance, and key initiatives to improve performance are starting to show results.18 Significant resources have now been focused on these issues, and a delay of the F-35 Full-Rate Production decision until 2019 has been accepted by the US, to allow time for the initiatives to take full effect. Nonetheless, the overall outcome, in terms of cost, schedule and capability delivery, remains dependent on the effectiveness of a range of initiatives being pursued to address the technical challenges identified in recent technical reviews.

27. From Australia’s perspective, although the recent US actions to reduce risk in the JSF Program are positive, there are implications arising from the three-year delay to the schedule for the F-35 Full-Rate Production decision (now not scheduled until 2019) that require close management. As indicated in ANAO Audit Report No.5 2012–13, Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability—F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Fleet Upgrades and Sustainment, 27 September 2012, Australia has for over a decade been actively upgrading its air combat fleet capability and addressing its sustainment. At the end of that audit, the Planned Withdrawal Date for the RAAF’s F/A-18A/Bs was 2020. The audit noted that the task for Defence of successfully sustaining the ageing F/A-18A/B fleet to that date, so that no capability gap arises before the introduction into service of the F-35As, was already challenging. Given the age and likely condition of these aircraft at that point, each additional year in service will involve significant costs.

28. At the completion of these two linked audits, the Government was yet to consider the need for a further extension, beyond 2020, of the Planned Withdrawal Date of the RAAF’s F/A-18A/Bs. However, in response to ANAO inquiries about contingency plans, Defence indicated that planning was underway to advise the Government on options in relation to this matter, including a limited extension beyond 2020. Nonetheless, should further delays occur in the JSF Program, Defence’s capacity to absorb any more delays in the entry into service of the replacement air combat capability to be provided by the F-35A has limits, is likely to be costly,19 and has implications for capability.

Australia’s partnership in the JSF Program

29. For comparatively modest investments of US$205 million and an estimated US$643 million respectively, Australia has secured Level 3 partner status in the SDD phase and in the production and later phases of the JSF Program.20 This status has enabled Defence to access a comprehensive range of data to inform the acquisition recommendations it has progressively presented to Government; to influence the decision-making within the JSF Program to suit Australia’s operational requirements, through membership of the JSF Executive Steering Board; and to facilitate Australian industry participation in the broader JSF Program. While the partner nation contributions to the SDD and production phases are separate from the costs of Australia’s acquisition of its own F-35 aircraft, in due course Australia will also benefit by acquiring F-35 aircraft at JSF partner nation prices.21

30. Subject to further government decisions, Australia intends to acquire up to 100 F-35 aircraft. In September 2012, the total development and production cost of 100 F-35As, and other costs shared with JSF partner nations, was estimated to be US$13.211 billion (then-year dollars). At the time of the audit, US Department of Defense agencies were conducting a coordinated, in-depth cost analysis of the production program with the aim of achieving increased efficiencies so as to reduce production contract prices.

F-35 concurrent development and production

31. The JSF development and production program’s size and engineering complexity, and its defence and industry importance, are reflected in the multinational partner arrangements between the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, Turkey and Australia.22 The JSF Program partner nations have established a global supply network focused on F-35 airframe assembly production, with the majority of F-35 Mission Systems development and production occurring in the US. Aircraft assembly, final system checkout, and contractual acceptance by the US Government from Lockheed Martin occur at Fort Worth, Texas. By July 2012, 13 F-35 flight test aircraft, six ground test articles and two pole-model radar signature test articles, produced as part of the SDD phase had been delivered, with an additional 28 F-35 Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP) phase aircraft having completed their maiden flights. At full maturity, the global supply network is expected to support annual production of more than 200 F-35 aircraft.

32. For technologically advanced systems such as the F-35, there needs to be an overlap between the system development phase and the production phase. This risk management strategy involves the production of fully integrated systems needed for test and evaluation purposes, and the development of production facilities and processes that are themselves tested and evaluated with respect to their ability to produce, within cost and schedule budgets, products verified to comply with function and performance specifications.

33. This ‘concurrent’ development and production strategy as applied in the JSF Program has been reviewed annually by the US Congress, and significant concerns arose about the costs that this strategy was generating. This was because, until recently, the US Government has been bearing nearly all of the costs of concurrency (such as re-work needed after additional testing).

34. From the Australian perspective, concurrency risks in the JSF Program are not as significant because the US, as the principal developer of the F-35, is bearing the bulk of the costs and risks involved. By the time Australia acquires its first F-35 aircraft, the concurrency issues currently being experienced are expected to have been largely dealt with.23 Rather, Australia has benefited from the concurrency strategy of enabling F 35 production processes and facilities to be tested and refined ahead of the F-35 Full-Rate Production decision, and in the face of the pending retirement of our existing air combat fleets.

F-35 test and evaluation program

35. Although current estimates of the F-35’s performance are close to those required, performance will not be fully demonstrated until the completion of Initial Operational Test and Evaluation, presently expected in February 2019.24 F-35 aircraft development and production risks are being managed through a large-scale and sophisticated F-35 ground and flight test program. Prior to conducting flight tests, each incremental advance in F-35 development is subjected to extensive laboratory testing. Once each incremental increase in F-35 capability has been cleared for entry into the flight test and evaluation program, testing commences in an extensively modified Boeing 737 which is used by Lockheed Martin to conduct F-35 system development and software integration testing. In addition, each F-35 sensor supplier continues to use surrogate aircraft to test their particular sensors; for example, Northrop Grumman conducts radar and Distributed Aperture System testing in its BAC 1-11 aircraft. The next stage of flight tests involves a fleet of 13 F-35 engineering development aircraft, and five F-35 LRIP aircraft assigned to the F-35 flight test program.25 There are also six F-35 airframes undergoing structural strength and durability (fatigue) testing, and two pole-model airframes used for radar signature testing. By June 2012, the F-35 mission systems had completed nearly 345 000 hours of laboratory testing and 18 500 hours of flight testing—of which 3700 hours were completed in F-35 aircraft.

36. In relation to the F-35A variant to be purchased by Australia, the test and evaluation program requires the achievement of 24 951 test points covering all F 35A war-fighting requirements needed to achieve the Initial Operational Capability milestone. By March 2012, F-35A capability testing was ongoing, and a total of 5282 test points had been achieved. This represents some 21 per cent of the overall testing required to validate Initial Operational Capability achievement.

37. By June 2012, the F-35A static test article had successfully completed its structural strength test program, and the F-35A durability test (fatigue test) article was about halfway through its two lifetimes test program of 16 000 hours. The durability test program aims to certify that the F-35A airframe can achieve its design safe life of 8000 hours under specified flight profiles.26 In addition, contract negotiations to extend the durability test to three lifetimes (24 000 hours) were underway as part of the US JSF Program’s F-35 high-risk mitigation management.

Software development

38. Software is critical to the success of the JSF Program, as it provides the means by which all safety-of-flight and mission-critical systems operate, and are monitored, controlled and integrated. F-35 software is being released in three capability blocks. Block 1 software provides an initial training capability, and in the second quarter of 2012 its test phase was completed and it was released into the F-35 pilot training program. Block 2 software is to provide initial war-fighting capability, including weapons employment, electronic attack, and interoperability between forces. At the time of the audit, the initial release of Block 2—known as Block 2A—was undergoing flight testing and was scheduled for release to the F 35 flight test program in September 2012, and for release to the F-35 pilot training program in the second quarter of 2013. The final release of Block 2 capability—known as Block 2B—is scheduled for 2015. Block 3 software provides full F-35 war-fighting capability, including full sensor fusion and additional weapons. At the time of the audit, 61 per cent of initial Block 3 capability had been developed against a target of 81 per cent, and its integration into F-35 flight test aircraft is planned to commence from November 2012. Block 3 release into the F-35 fleet is scheduled for mid-2017. At the time of the audit, F-35 software development was undergoing high-risk mitigation management.

Cost control

39. In order to reduce the cost of F-35 aircraft and their logistics support for JSF Program partner nations, and for US Foreign Military Sales customers, US Government personnel from procurement, contract administration, contract audit, and engineering organisations were, at the time of the audit, conducting a coordinated and in-depth cost analysis of the F-35 production phase. The pursuit of efficiencies through this process is intended to achieve reductions in production contract prices. The cost analysis is part of the US Government’s Will-Cost/Should-Cost management policy, which is focused on identifying unneeded cost and rewarding its elimination over time.

40. The F-35 cost reduction effort is enabled by the US Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA), passed in 1961, which requires prime contractors and subcontractors to submit cost or pricing data and to certify that such data are current, complete and accurate, prior to the award of any negotiated contract. Cost reduction is also enabled by the US Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, which requires proactive program management practices that include targeting affordability and controlling cost growth, improving tradecraft in services acquisition, and reducing non-productive processes. The most extensive implementation of those practices was the JSF Program’s 2010 Technical Baseline Review, which gave rise to several program changes that have resulted in the JSF Program progressing closer to cost, schedule and the technical progress plans than previously achieved.

41. As at June 2012, the JSF Program Office estimated the Unit Recurring Flyaway (URF) cost of a CTOL F-35A aircraft for Fiscal Year 2012 to be US$131.4 million. That cost includes the baseline aircraft configuration, including airframe, engine and avionics. The URF cost is estimated to reduce to US$127.3 million in 2013, and to US$83.4 million in 2019. These expected price reductions take into account economies of scale resulting from increasing production volumes, as well as the effects of inflation. The estimates indicate that, after 2019, inflation will increase the URF cost of each F-35A by about US$2 million per year. However, these estimates remain dependent upon expected orders from the United States and other nations, as well as the delivery of expected benefits of continuing Will-Cost/Should-Cost management by the US Department of Defense.

Overall summary

42. As indicated in paragraph 14, the audit objective was to assess the progress of the AIR 6000—New Air Combat Capability project in delivering the required combat aircraft within approved cost, schedule and performance parameters. In this context, the ANAO assessed Defence’s arrangements to ensure that it has adequate insight into the JSF Program’s development and production of the F-35A to inform progressive acquisition decisions by the Government and underpin appropriate contingency planning to avoid any capability gap opening up between the withdrawal from service of the RAAF’s F/A-18 fleets, particularly the F/A-18A/B fleet, and the entry into service of the F-35A-based air combat capability.

43. Australia’s partnership with the US in the JSF Program, including in terms of Australian Defence staff working within the JSF Program Office, has provided Defence with considerable insight into the status of the program, its risks, and the actions over time that the US Department of Defense is taking to mitigate these risks. Defence (including the AIR 6000—New Air Combat Capability project office here in Australia, the RAAF and the Capability Development Group) monitors and analyses information and evidence acquired through our partnership with the US, so that it may inform the Government on both F-35 procurement decisions and options for managing the risk of an air combat capability gap arising before the entry into service of the F-35A aircraft.

44. Overall, the achievement of the JSF Program’s objectives of developing and producing F-35 aircraft for high-threat multi-role operations has progressed more slowly and at greater cost than first estimated. Nonetheless, recent indications are that initiatives to improve performance are starting to show results, in terms of software development milestones being more closely adhered to, and planned flight test targets being reported as met or exceeded in 2011–12. However, a full assessment as to how effectively that progress can be maintained will be some years off. At the time of the audit, almost 80 per cent of the F-35 test and evaluation program was yet to be completed, so significant F-35 key performance parameters had not been fully validated as being achieved by F-35 aircraft.27 Although program cost reduction measures are being pursued by the US Department of Defense and its contractors, the cost targets remain challenging, as do wider issues outside the JSF Program Office’s control, such as the ‘debt sequestration’ initiative by the US Government.28

45. Accordingly, while the ANAO considers that Defence has gained reasonable assurance that adequate work has been undertaken to identify significant risks in the US JSF Program, and that measures have been progressively developed and implemented to mitigate them, significant risks still remain, including in relation to mission-system data processing, software development schedule adherence, Helmet Mounted Display performance, structural health monitoring and structural durability testing. These will require close management as the final stages of development of the F-35A aircraft unfold.

46. For Australia, the remaining challenges include coordinating all the elements of capability that will make the F-35 fleet into a fully effective military system. This includes actively managing the transition from the F/A-18 fleets to the F 35A-based air combat capability, including containing costs through limiting the period during which the RAAF bears the expense of sustaining both F/A–18A/B and F-35A aircraft. As previously discussed, at the time of preparation of this report, the Planned Withdrawal Date for the F/A-18A/B fleet was 2020. Following US Government and Australian Government decisions that have delayed the intended earlier F-35A delivery, the ANAO asked Defence for advice on its consequent contingency planning. Defence advised that later this year it will be presenting options to the Government on managing the air combat capability, including a limited extension of the Planned Withdrawal Date for the F/A-18A/Bs, as the RAAF transitions from the current fleet to a predominantly F-35A fleet.29 Defence indicated that this would include strategies to reduce the risks associated with the likely extension of the F/A-18A/B fleet’s operational life, and to minimise risks associated with progressing to the F-35A’s Initial Operational Capability.

47. The ANAO has not made any formal recommendations for administrative improvements in Defence’s management of the ADF’s air combat capability in this audit report (or in its companion report, Audit Report No.5 2012–13, Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability—F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Fleet Upgrades and Sustainment). This is because, in the context of the JSF Program where there are many dependencies not under Australia’s control, the approach adopted to-date by Australian Governments and the Defence Organisation has provided appropriate insight into the program, in support of informed decision-making, commensurate with the cost and complexity of the planned acquisition.

48. Nonetheless, the successful coordination of this highly complex and costly procurement with the effective sustainment of the ageing F/A-18A/B fleet and the planned transition to an F-35-based air combat capability in the required timeframe, so that a capability gap does not arise between the withdrawal from service of the F/A-18A/B fleet and the achievement of full operational capability for the F-35, remains challenging. Following US and Australian Government decisions that have delayed earlier F-35A delivery intentions, the F/A-18A/B fleet’s operational life is likely to be extended beyond the current Planned Withdrawal Date of 2020. As indicated in paragraph 27, Defence’s capacity to accommodate any further delays in the production and/or acquisition of F-35s through a further extension to the life of the F/A-18A/B fleet, beyond the limited extension currently being considered, has limits, is likely to be costly,30 and has implications for capability. That said, decisions in relation to capability for the ADF, including Australia’s acquisition of F-35As, properly rest with the Australian Government, informed by advice from Defence.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2—JSF Concept Refinement and Technology Development

49. The JSF Program is managed under the multi-phase US defense acquisition process, which steps through concept refinement, technology development, system development and demonstration, early and final production, and sustainment and disposal. The program seeks to satisfy the combat aircraft needs of the United States and its partner nations, and is the culmination of several projects in the US and the United Kingdom, some of which date back to the 1980s. The first phase developed a validated set of combat aircraft requirements, demonstrated key leveraging technologies, and developed operational concepts for subsequent strike weapon systems. Flight testing of the JSF concept demonstrator aircraft (the X 32 and X 35) was completed in August 2001, and the results were reported to have met or exceeded expectations, to an unprecedented degree in many cases. In October 2001, the US Secretary of Defense provided certification to Congressional Defense Committees that the JSF Program demonstrated sufficient technical maturity to enter the SDD phase.

50. In May 1999, project AIR 6000 was formed within Defence, with a remit to consider the ‘whole-of-capability’ options for providing Australia’s ongoing air combat and strike capability once the F/A-18A/B and F-111 aircraft were withdrawn from service. In mid-October 2002, Australia formally joined the JSF Program’s SDD phase via a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), and with a commitment to contribute US$150 million.31 Since then, AIR 6000 has had two objectives: to deliver a new air combat capability that is characterised by the attributes of balance, robustness, sustainability and cost-effectiveness; and to maximise the level and quality of Australian industry and science and technology participation in the global JSF Program. AIR 6000 aims to achieve these objectives through Australia’s partnership in the JSF Program.

51. The Australian Government gave First Pass approval for the purchase of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter in November 2006, shortly before Australia joined the JSF Production, Sustainment and Follow-on Development MoU.32 In November 2009, at Second Pass, the Government approved Phase 2A/B Stage 1 funds, at an estimated cost of $3.2 billion, to acquire an initial tranche of 14 F-35A aircraft, establish the initial training capability in the United States, and allow commencement of operational testing in Australia.33

52. In May 2012, in the context of the 2012–13 Federal Budget, the Government announced its decision to delay the acquisition of 12 of this initial tranche of 14 aircraft by two years, with the result that the acquisition of these aircraft would be better aligned with the US Initial Operational Release of the F-35A aircraft.34 At the time of the audit, Australia had no contractual obligation to purchase more than the long-lead items for two F-35A aircraft.35

53. Following the May 2012 Budget decision, Defence was replanning the F-35 acquisition schedule under AIR 6000, including the schedule for the remaining 12 aircraft to be acquired under Phase 2A/B Stage 1, and this replan was subject to government approval. The delivery of the remaining 12 aircraft in Stage 1 needs to occur in a manner that facilitates the training of sufficient RAAF pilots, and the conduct of operational test and evaluation that demonstrates the achievement of Initial Operational Capability by the date approved by the Government following its consideration of the advice Defence intends to provide this year on options.

Chapter 3—F 35 System Development and Demonstration

54. The SDD phase involves development of the F-35 aircraft, the establishment of F 35 manufacturing facilities and processes, and the completion of system development test and evaluation. This phase commenced in October 2001 and is now expected to end in 2019, at an estimated overall cost of US$55.234 billion (then-year dollars).

55. The SDD phase aims to develop and prove the F-35 aircraft and its manufacturing system, particularly through a substantial test and evaluation program. Eight partner nations joined the United States in this phase, contributing US$5.2 billion. In 2010, the United States added US$4.6 billion to the SDD phase, over and above its existing share.

56. Australian participation in the SDD phase has enabled Defence staff to be stationed in the JSF Program Office, and to play a role in promoting capability outcomes for Australia as program decisions are made. It also allows Australian firms to bid for work as part of the F-35 Global Supply Team. As at June 2012, Australian industry had signed JSF SDD and production contracts to a total value of $300 million.

57. As of December 2010, estimates for all F-35 Key Performance Parameters (KPP) were within threshold requirements, with the exception of the F-35A Combat Radius KPP. In February 2012, the US Joint Requirements Oversight Council revised this KPP to reflect the aircraft’s optimum airspeed and altitude values, as obtained through testing. Once these values were applied to the mission profile, the performance of the aircraft exceeded the original KPP threshold value. Although current estimates of the F-35’s performance are close to those required, performance will not be fully demonstrated until the completion of Initial Operational Test and Evaluation, currently scheduled for February 2019.

58. As at July 2012, 13 of the planned 14 SDD flight test aircraft had been delivered. An additional five production aircraft will be used in the SDD test program, resulting in a total of 19 aircraft in the SDD test fleet. There were also two airborne laboratories and several ground laboratories. Combined, these resources have enabled the conduct of over 18 500 hours of flight testing and 345 000 hours of laboratory testing of F-35 flight and mission system performance.

59. All three F-35 variants are designed and manufactured by Lockheed Martin to a Joint Services specification, which includes a structural-fatigue safe life of 8000 airframe hours for aircraft operating within specified flight profiles.36 The SDD phase includes full-scale static and durability tests of representative test articles of all three F-35 variants, in order to verify that the F-35 aircraft may safely be operated within expected usage patterns, out to their design lifetimes (or safe life) of 8000 airframe hours, without excessive risk of a catastrophic structural failure.

60. By September 2011, airframe structural strength (static) testing of the three F-35 variants was complete. In August 2012, airframe full-scale durability testing (or fatigue testing) achieved 8000 hours of testing, which is one Equivalent Flight Hours (EFH) or one aircraft lifetime. This is 50 per cent of the two lifetimes of testing required for SDD. Two airframe lifetimes testing to 16 000 hours is scheduled for completion by 2015. Durability tests to three lifetimes (24 000 hours) were decided on as part of the Technical Baseline Review in 2010. This additional testing will provide increased assurance that a structural-fatigue safe life of 8000 hours has been achieved by the F-35 design and production process. At the time of the audit, this additional durability testing was expected to be entered into contract during the latter half of 2012.

61. By August 2012, the F-35 SDD test fleet consisted of 15 aircraft—13 SDD test aircraft and two production aircraft. Of these, ten were used for flight sciences tests and five for mission system tests. The overall F-35 SDD flight test plan calls for the verification of 59 585 test points through developmental test flights by the end of the SDD phase. This testing needs to be done in line with the development of each of the three F-35 capability Blocks, and is therefore being conducted while software development and aircraft production continues. In relation to the F-35A variant to be purchased by Australia, the test and evaluation program requires the achievement of 24 951 flight test points covering all F-35A Block 3 Initial Operational Capability requirements. In March 2012, F-35A capability testing was ongoing, and a total of 5282 test points had been achieved. This represents some 21 per cent of the overall testing required to verify achievement of Initial Operational Capability. Consequently, almost 80 per cent of the F-35 test and evaluation program is yet to be completed, and significant F-35 Key Performance Parameters are yet to be fully validated as being achieved by F-35 aircraft. Completion of Initial Operational Test and Evaluation of F-35 Block 3 capability is presently scheduled for February 2019.37

Chapter 4—F 35 Production and Sustainment

62. The F-35 production phase commenced in November 2006, and the US Government’s December 2011 production cost estimates for the 2457 F-35 aircraft it currently intends to acquire amounted to US$335.7 billion (then-year dollars). This phase is expected to end in 2037.

63. F-35 production is occurring under the Production, Sustainment and Follow-on Development Memorandum of Understanding (JSF PSFD MoU), which establishes the acquisition, support, information access and upgrade arrangements for the JSF Air System over its service life. Australia signed this MoU on 12 December 2006, and has committed an estimated US$643 million as its contribution to the production, sustainment and follow-on development of the F-35 aircraft (this amount is separate from the costs of Australia’s Z

acquisition of its own F-35 aircraft). Under this arrangement, the costs of follow-on development (that is, future upgrades) will be shared by the partner nations in proportion to the number of aircraft they purchase. In Australia’s case, our PSFD investment represents around 3 per cent of the overall shared non-recurring production cost identified in the JSF PSFD MoU.

64. When the SDD phase began in 2001, the US Department of Defense also approved the production of 465 Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP) F-35 aircraft in six LRIP contracts, in order to meet the US Armed Services’ Initial Operational Capability requirements, prevent a break in production, and ramp-up to Full-Rate Production. Program changes to December 2011 have resulted in the number of LRIP aircraft to be produced for the US Armed Services decreasing from 465 to 365. This is in accordance with the US Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Request, which sought to balance development and concurrency risk, while leaving room for procurement by the international partner nations and for procurements by other nations through the US Government’s Foreign Military Sales arrangements. As at August 2012, 205 F-35 LRIP aircraft were planned for procurement by these nations, bringing the total LRIP production planning to 570 aircraft. Since 2001, the number of production lots has increased from six to 11, with each LRIP lot the subject of separate contracts negotiated between the United States Government and Lockheed Martin. The first LRIP contract commenced in 2006, and the final one is expected in 2018.

65. The numbers of aircraft in each LRIP lot have been reduced as a result of program reviews in recent years, as part of a significant slowing of the planned production ramp-up. This is in response to technical difficulties and slower than envisaged production of the SDD phase’s engineering development aircraft. The rate of design changes during F-35 system development has also remained higher than expected, and this has resulted in the need to implement design changes in the LRIP aircraft in the production line and those already produced.

66. Producing aircraft before the completion of the SDD phase (known as concurrency) has resulted in increased engineering and budget risks. In response to the budget risks, the US Department of Defense has changed its contracting strategy, sharing some of the

costs of concurrency up to a cost ceiling, above which the costs are to be borne by the contractor. Recent testimony from the US Department of Defense to Congress was that concurrency is a transient issue, with risks being progressively reduced as the aircraft design is confirmed or issues requiring changes are identified and incorporated.

67. Australia’s exposure to concurrency costs is limited in three ways. Australia presently intends to order its first two F-35A aircraft in 2012, in time for inclusion in the 2014–15 LRIP Lot 6 production program. The purchase of the F-35A variant is likely to contain Australia’s exposure to concurrency-related costs to the aircraft variant with the least design and production risk. Since Australia is ordering its first aircraft from LRIP Lot 6, this further contains Australia’s exposure to only those design and production defects that were not discovered in the earlier five LRIP production lots. Further, as the bulk of Australia’s F-35A orders are scheduled to occur between 2015 and 2020, it is expected that the risk of F-35 design and production defects being discovered for the first time during that period, and their remediation costs, would decrease significantly from present levels.

68. The JSF sustainment concept seeks to maximise affordability through globalised asset pooling, platform-level performance-based logistics with Lockheed Martin, and best-value placement of global support capacity. At the time of the audit, overall sustainment costs were not of tender quality due to the early stage of the program, and high-confidence estimates are not expected until the JSF system achieves maturity in around 2018. However, some actual sustainment costs became available from late 2011, when the first F-35s commenced service at the US Air Force’s Eglin Air Force Base, and these figures are now being used to refine and update forward estimates.

69. The objectives of the New Air Combat Capability project include maximising the level and quality of Australian industry participation and science and technology participation in the global JSF sustainment program. Project records indicate that Australia’s minimum F-35 sustainment activities that must be performed locally, based on sovereign needs and performance requirements, have been defined. These include an intent to keep the RAAF workforce constant between the F/A-18A/B and F-35 fleets, and to ensure that, once the aircraft have arrived in Australia, all Australian aircraft maintenance and pilot training occurs in Australia.

Chapter 5—JSF Program Reviews and Progress

70. The JSF Program is acknowledged as the Pentagon’s most expensive current weapons program. Evaluating the cost of such a large acquisition program is extremely difficult, given the inherently long and expensive task of designing and manufacturing aircraft with leading-edge technology, and maintaining that capability for up to 30 years.

71. The JSF Program Office, other US Department of Defense authorities, and the US Government Accountability Office have conducted regular reviews and audits of the JSF Program. These provide a level of assurance that the JSF Program is progressing with an appropriate level of US Government oversight focused on improving program outcomes. They have resulted in significant revisions of production numbers, costs and schedules. The estimated cost of the F-35 development phase has increased from US$34.4 billion to US$55.234 billion (in then-year dollars), a rise of 61 per cent since system development commenced in October 2001. Further, the estimated total cost to the US of the program as a whole has risen from US$233.0 billion to US$395.712 billion (in then-year dollars), a rise of 70 per cent since 2001. As at December 2011, the development effort was reported by the US Department of Defense to be 80 per cent complete. Part of the increases in development costs can be attributed to US Government decisions to increase the scope of F-35 development and demonstration effort.

72. The most comprehensive systems engineering review of the JSF Program to date was the 2010 Technical Baseline Review (TBR), which in January 2011 led to a budget increase of US$4.6 billion. That increase was needed to fund the program’s March 2012 cost and schedule rebaseline, which included the SDD phase being extended by three years to 2019. At the same time, budget considerations and concurrency risks drove a decision to further reduce the numbers of aircraft being produced in LRIP lots. Data from Lockheed Martin’s Earned Value Management System indicates that, since the TBR, the program has been achieving its cost and schedule goals in a more sustained manner than previously, indicating the potential for the program to continue progress within its cost and schedule parameters.

73. The US Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, prompted by the cost overruns in the JSF Program and other programs, has driven a strong focus towards delivering better value to the taxpayer. For the JSF Program in particular, the US Department of Defense has adopted a proactive approach to pricing through a Should-Cost initiative, which requires program managers to justify each element of program cost and show how it is improving. In the first half of 2012, negotiations for the next F-35 production contract were being conducted within a Fixed Price Incentive Firm Target contract arrangement. This is expected to lead to Lockheed Martin and the US Government sharing equally the burden of any cost overruns over a contract Target Price and up to a Ceiling Price, which is set at 6.5 per cent above the Target Price; any costs above the Ceiling Price are to be Lockheed Martin’s responsibility.

Summary of agency response

74. Defence provided the following response to this report and the companion report:

Defence welcomes the ANAO audit reports on the Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability. These extensive reports demonstrate the complex and evolving nature of Australia’s air combat systems which are at the forefront of Australia’s Defence force structure.

These reports also highlight a number of challenges that Defence faces in transitioning from its current 4th and 4.5th generation fighters into the 5th generation F-35A.

Defence has made significant progress towards increasing efficiencies and maximising combat capability over a decade of continuous air combat upgrades and acquisitions. The experience gained stands Defence in good stead for the acquisition of future air combat capabilities through a strong collegiate approach across the various areas of Defence, the Defence Materiel Organisation and external service providers. This experience will ease the burden during what will be a carefully balanced transition to the F-35A.

Defence acknowledges that there is scope to realise further improvements through process alignment and business practice innovation, and will continue to build on the work that has already been undertaken. Defence is committed to managing the complexities of its various reform programs whilst continuing to assure Australia’s future air combat capability requirements.

Footnotes

1 Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030. Defence White Paper 2009, Canberra, 2009, paragraph 7.3, p. 53.

2 In May 2012, the need for a possible further extension to the F/A-18A/B fleet’s Planned Withdrawal Date arose because of the Government’s decision to better align the delivery of Australia’s F-35A aircraft with the US Department of Defense’s F-35 production and acquisition schedule. Consequently, the precise timing of the F/A-18A/B withdrawal from service is dependent upon the delivery of the F-35A aircraft under schedules that are yet to be finalised.

3 The Defence Portfolio consists of a number of component organisations that together are responsible for supporting the defence of Australia and its national interests. The three most significant bodies are: the Department of Defence, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the Defence Materiel Organisation. In practice, these three bodies have to work together closely and are broadly regarded as one organisation known as Defence (or the Australian Defence Organisation). All three of these component organisations are involved in the F-35A acquisition.

4 Sensor fusion is the ability to integrate information from both on-board sensors and off-board sources and present the information to the pilot in an easy-to-use format, thereby greatly enhancing the pilot’s situational awareness.

5 Senator the Hon. Robert Hill, Minister for Defence, and the Hon. Ian MacFarlane, Minister for Industry, Australia’s future air combat capability, transcript of joint press conference, 27 June 2002, p. 2.

6 The Hon Dr Brendan Nelson MP, Minister for Defence, The Joint Strike Fighter, media release, 10 November 2006.

7 Department of Defence, Defence Capability Plan 2012, Public Version, p. 54. However, this timetable may be affected by the May 2012 Budget decision outlined in paragraph 9.

8 Prime Minister, Minister for Defence, Minister for Defence Materiel—joint press conference—Canberra, media transcript, 3 May 2012; Portfolio Budget Statements 2012–13: Defence portfolio, p. 166; The Hon Stephen Smith MP, Minister for Defence, Address to the Air Power Conference, Canberra, 10 May 2012.

9 Then-year cost estimates are based on the estimated cost of labour and materials and currency exchange rates, at the time expenditure is to occur.

10 The JSF Program partner nations are the USA, United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, Turkey and Australia.

11 Under the international agreements for the JSF Program, the industries of partner nations gained the right to tender for JSF development and production work. The industrial participation program was excluded from audit coverage in order to allow an increased focus on the F-35 development and production phases. However, for convenience, diagrams of the Global Supply Team for the JSF and of Australian industry involvement are included in the main report.

12 Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030. Defence White Paper 2009, Canberra, 2009, paragraph 8.22, p. 61.

13The US Department of Defense’s Director, Operational Test and Evaluation, the US Defense Contract Audit Agency, and the US Department of Defense’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation.

14 Since 2001, the GAO has delivered eight reports specifically on the JSF Program, with the latest delivered in June 2012. As a ‘congressional watchdog’, its focus in undertaking this work has necessarily been on determining whether US Federal funds are being spent efficiently and effectively. In contrast, this audit provides an Australian perspective, which has regard to GAO and other reports, but our conclusions may not always align with the US perspective.

15 Northrop Grumman, Pratt & Whitney and BAE Systems are also major contractors on the JSF Program.

16 Planned production of the three variants of the F-35 for the US Services is as follows: 1763 F-35A (CTOL) for the US Air Force, 340 F-35B (STOVL) and 80 F-35C (CV) for the US Marine Corps, and 260 F-35C (CV) for the US Navy.

17 There are three levels of partnership in the SDD phase, dependent on the financial contribution involved, which give each partner nation varying rights, from influencing the design requirements to accessing program information and having personnel within the JSF Program Office. In the production and later phases, partnership contributions depend on the number of aircraft purchased by a country, the number of partners, and the total cost of the program.

18 These are discussed in paragraph 44, and include software development and flight test targets.

19 See Chapters 2 to 4 in ANAO Audit Report No.5 2012–13, Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability—F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Fleet Upgrades and Sustainment, 27 September 2012.

20 The other partner nations’ contributions to the SDD phase range from US$2 billion for Level 1 partners to US$125 million for Level 3 partners. For the production and later phases, the total contribution by partner nations is estimated at US$21.876 billion, with the US bearing US$16.843 billion of that amount. Partner contributions are made bi-annually, with amounts determined through agreed cost-share arrangements.

21 An alternative to Australia’s joining the SDD and production phases was the acquisition of F-35 aircraft and their associated systems and logistics support through the US Government’s Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. The US FMS program manages the sale of US defense articles and services authorised by the US Arms Export Control Act. It is operated on a no-profit/no-loss basis, and FMS purchases must be funded in advance by the FMS customer. An FMS Administrative Surcharge is applicable to all purchases made through the US FMS program, and from 1 August 2006 this surcharge rose from 2.5 per cent to 3.8 per cent. Other additional FMS fees include a Contract Administration Services Surcharge of 1.5 per cent, and a Nonrecurring Cost fee for pro rata recovery of development costs. The amount of cost recovery is decided during negotiation of an FMS case, although it may be waived. As a partner in the Production, Sustainment and Follow-on Development (PSFD) phases, Australia will not be acquiring the JSF via the US FMS program, and therefore will not incur any FMS fees for its aircraft.

22 The partnership is based on two Memoranda of Understanding (MoU): the JSF System Development and Demonstration (SDD) MoU signed in 2001–02, and the Production, Sustainment and Follow-on Development (PSFD) MoU, signed in 2006–07. Australia’s contribution to the SDD MoU arrangement was US$150 million, with a further US$50 million to be paid by 2014. As at December 2011, Australia’s commitment to the PSFD MoU amounted to an estimated US$643 million.

23 As long as the discovery of defects continues to diminish and the correction of defects by the contractor remains timely and effective.

24 Selected acquisition report (SAR): F 35, as of December 31, 2011, Washington DC, pp. 9, 11–15.

25 At the time of the audit, the 14th and final SDD aircraft was to be delivered later in 2012.

26 Airframe static strength and durability tests are conducted in laboratories to ensure that a structure, such as an aircraft wing, can withstand the extreme loads likely to be encountered in flight, and to provide assurance that the aircraft will remain airworthy for its designed service life. During static testing, the actual load-bearing strength of an airframe structure is compared to design specifications. During durability (fatigue) tests, airframe assemblies are subjected to smaller repeated loads that can cause cumulative damage over time. These tests are conducted to verify and certify the safe life of airframe structures, to help determine inspection requirements and inspection intervals for the fleet of aircraft, to identify critical areas of the airframe not previously identified by analysis, and to certify that the structure can meet or exceed service life requirements.

27 Validation is the proof, through evaluation of objective evidence, that the specified intended end use of a product or system is accomplished in an intended environment.

28 The Budget Control Act of 2011, signed into law by President Obama on 2 August 2011, committed the US Congress to legislating US$1.2 trillion in savings by 23 December 2011, in the absence of which, automatic cuts would apply to federal spending—including defense spending—over the following ten years, beginning in January 2013. The Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction failed to reach agreement by the specified date, and at the time of writing (September 2012) the automatic cuts, known as ‘debt sequestration’, remain on the United States statute book.

29 Currently, the RAAF’s 24 Super Hornets (the F/A 18Fs) have a Planned Withdrawal Date of 2025, and so will form part of Australia’s air combat capability even after the planned entry into service of the F 35As and the withdrawal of the F/A 18A/Bs. In August 2012, the Government also announced its decision to acquire the Growler electronic warfare system for 12 of the Super Hornets, with the total capital cost estimate for this acquisition around $1.5 billion. Accordingly, the Planned Withdrawal Date for the Super Hornets may be reviewed.

30 See Chapters 2 to 4 in ANAO Audit Report No.5 2012–13, Management of Australia’s Air Combat Capability—F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet Fleet Upgrades and Sustainment, 27 September 2012.

31 In 2008, Australia committed an additional US$50 million to the SDD phase, to be paid between 2009 and 2014.

32 The First Pass approval process provides the Government with an opportunity to narrow the alternatives being examined by Defence to meet an agreed capability gap. This includes approval to allocate funds from the Capital Investment Program to enable the options endorsed by Government to be investigated in further detail, with an emphasis on cost and risk analysis.

33 The Second Pass approval process leads to the final approval milestone, at which the Government endorses a specific capability solution and approves funding for its acquisition.

34 Prime Minister, Minister for Defence, Minister for Defence Materiel—joint press conference—Canberra, media transcript, 3 May 2012; Portfolio Budget Statements 2012–13: Defence Portfolio, p. 166.

35 Defence Materiel Organisation, New Air Combat Capability Integrated Project Team, Acquisition project management plan, version 1.0a, July 2011, p. 15.

36 By way of comparison, the F/A-18A/B and F/A-18F aircraft are rated at 6000 hours.

37 Selected acquisition report (SAR): F-35, as of December 31, 2011, Washington DC, pp. 9, 11–15.