Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Limited Tender Procurement

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether selected entities had appropriately justified the use of limited tender procurement and whether processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Summary

Introduction

1. Procurement is an integral part of the way the Australian Government conducts business and provides services. Throughout 2013–14, Australian Government entities published 66 447 contract notices for goods and services valued in excess of $49.5 billion.1 In view of the large number of procurements undertaken and the centrality of this activity to the operation of government and program delivery, entities’ procurement practices are expected to be efficient, effective, economical, ethical, consistent with the Commonwealth legal and policy requirements, and commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

2. In undertaking procurement, entities are required to adhere to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The CPRs are the keystone of the Government’s procurement policy framework and underpin Australia’s international obligations in accordance with free trade agreements. The CPRs establish procurement principles that apply to all procurement processes, and promote value for money as the core principle of the Government’s procurement policy framework. Value for money is enhanced and complemented by other key principles—encouraging competition; efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of resources; and accountability and transparency in decision making. The arrangements are intended to benefit both the Commonwealth and suppliers, including small and medium businesses. Applying these procurement principles is a requirement of the CPRs, and necessitates that entities take a considered approach when establishing arrangements for individual procurements.

Limited tender procurement

3. The CPRs outline three procurement methods that entities can use when conducting procurements: open, prequalified or limited tender. This audit focuses on limited tender. Limited tender procurement involves an entity approaching one or more potential suppliers of its choice, to make submissions, such as quotes or tenders, to provide goods or services. By its nature, limited tender is less competitive than open and prequalified tender as it does not provide the opportunity for all potential suppliers to compete for the provision of goods and services. In 2013-14 limited tender was the most widely used of the available procurement methods representing 56 per cent by number of procurements and accounted for the greatest percentage of expenditure at 48 per cent by value, $23.8 billion.

4. In order to encourage competition, the CPRs limit the use of non-open approaches to the market for high value procurements (generally above $80,0002) to a small number of specified circumstances, such as when an open approach to the market has failed. For lower valued procurements entities should conduct an appropriately competitive procurement process commensurate with the scale, scope and relative risk of the procurement. In all cases, entities need to be mindful that it is generally more difficult to demonstrate adherence to the procurement principles such as value for money, encouraging competition and ethical use of resources when conducting a limited tender, but under the CPRs the onus is on them to do so.3

Previous ANAO audits

5. The ANAO has conducted five audits since 2007 that have focussed on aspects of procurement across Australian Government entities.4 Each of these audits identified some shortcomings with respect to entities’ application of the CPRs5 for a significant proportion of procurements examined. In general, these audits found that entities needed to employ more competitive procurement processes, better document value for money assessments and obtain appropriate approvals.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess whether selected entities had appropriately justified the use of limited tender procurement and whether processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules including the consideration and achievement of value for money.

7. The audit was undertaken in three entities which had reported on AusTender6 a high proportion of procurements conducted through limited tendering. The entities were the:

- Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS);

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT); and

- Department of Human Services (DHS).

8. The scope of the audit included an examination of the policies and practices supporting the use of limited tendering as well as the assessment of these entities’ records in respect to a sample of procurements.

9. To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO’s high level criteria considered whether the entities had adhered to the requirements of the financial management framework7; applied sound practices when undertaking procurements via limited tender; and established effective procurement support and review arrangements.

Overall conclusion

10. The procurement of goods and services is a key activity for Australian Government entities and, in undertaking procurement, entities are required to adhere to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The CPRs promote value for money as the core principle in all procurements. The other key principles—encouraging competition, efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of resources, and accountability and transparency in decision making—underpin the achievement of value for money. Entities are required to have regard to all such considerations in their procurement activities.

11. Limited tender procurements are often perceived by entity officials as the quickest and cheapest procurement method, particularly when the cost and time involved in running a full open approach to market is considered, or when engaging a new supplier may result in extra time having to be spent getting the supplier up to speed. However, by their nature limited tender procurements reduce competition as the approach commonly involves an entity selecting the supplier(s) of its choice, to provide goods or services. To mitigate the risks which flow-on from this to the achievement of value for money, the CPRs only allow the use of limited tender for high value procurements, in a small number of specified circumstances and with appropriate justification.

12. Overall this audit, which focused on the use of limited tender in the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS), the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), and the Department of Human Services (DHS) highlights the risks to value for money and a fair go for suppliers when applying limited tender to procurement; and the need for entities to take steps to make sure that officials satisfy the requirements of the CPRs. Audited entities were reasonably familiar with the Government’s procurement framework and had developed guidance material that reflected the requirements of the CPRs, including guidance on the use of limited tender. In practice however, this guidance was not always followed and appropriate justification for the use of limited tender was not recorded for all of the procurements examined. The ANAO observed gaps in the planning of procurements in each of the audited entities. In addition there were instances in ACBPS and DFAT, where either no justification was provided, or the recorded justification for limited tender procurements did not meet the conditions for limited tender specified in the CPRs. Previous ANAO audits have identified that entities need to employ more competitive procurement practices consistent with government expectations. Although limited tender procurement may provide a streamlined process, unless its use can be justified in accordance with the CPRs, it should not be regarded as an appropriate approach as it does not encourage competition among potential suppliers, thereby making it more difficult for entities to demonstrate the achievement of value for money.

13. Entities’ approaches, to varying degrees, were not fully effective in satisfying the procurement principles, including value for money and fair and open competition. The procurements examined by the ANAO indicated that in general, a greater emphasis on earlier planning for procurement activities would likely improve procurement outcomes. There was scope for entities to better estimate the expected value of procurements and better demonstrate consideration of decisions in relation to the procurement method to be applied. Similarly, entities could improve their performance in relation to demonstrating how value for money was considered and achieved, as well as obtaining appropriate approvals prior to entering into agreements with suppliers.

14. Furthermore, and consistent with previous ANAO audit findings, entities continue to inaccurately report contract information on AusTender. The ANAO’s examination of a sample of 155 contract notices (reported on AusTender as having been conducted via limited tender), identified that 45 (29 per cent) of the contract notices had been misreported. Inaccurate reporting of contract details diminishes the transparency of Commonwealth procurement information.

15. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving entity procurement practices in relation to the use of limited tender, including strengthening pre-approval compliance assurance mechanisms, and enhancing the accuracy of AusTender reporting. More broadly, the audit draws attention to the complexities of the CPRs. The rules governing the use of limited tender have not substantially changed since they were introduced in 2005, and it is reasonable to expect that entities would have developed sound practices to support a consistently high level of conformance with the CPR’s requirements and reporting. However, demonstrating outcomes which conform to the CPRs is an ongoing challenge for entities. This is due, in part, to the extent to which entity officers are involved in procurement (which varies significantly depending on the frequency they undertake procurement) and follow available advice. Entities also face the prospect that officials may try to save time and effort by avoiding open tender processes which can be perceived as onerous—without appropriate regard for the impact on suppliers and potential savings which may arise had more competitive processes been applied.

16. Key to achieving better performance is the need for entities to better balance the broader benefits of competitive tendering and streamlined practices when undertaking procurement. Such a balance would see entities giving greater consideration to the scope of the potential procurement need at the outset and more often seeking opportunities to approach the market to enhance the potential to achieve value for money. It is important for entities to ensure that when adopting procurement processes, these are undertaken in a manner that consistently considers and addresses the objectives, rules and requirements of the government’s procurement framework.

Key findings by chapter

Limited Tender Procurement Processes (Chapter 2)

17. When procuring goods and services, the Australian Government has an overarching objective of achieving value for money. Value for money is enhanced through proper procurement planning to support the selection of an appropriate procurement method that encourages fair and open competition commensurate with the size, scale and risk of the procurement. Limited tender procurements generally reduce competition and therefore, under the CPRs, may only be undertaken in specific circumstances for high value procurements.

18. Estimating the expected value of a procurement is a key step in determining an appropriate procurement method. Involving the delegate8 early in the planned procurement approach for more complex or high value procurements is prudent and can assist in ensuring the intended approach complies with the rules and principles established in the CPRs. It may also assist in achieving a better value for money outcome. The ANAO’s analysis of a sample of 110 procurements identified that planning documentation contained an estimated value of the procurement in 85 per cent of cases and there was evidence of delegate approval or clearance to approach the market in 71 per cent of the procurements reviewed.

19. For procurements below the relevant threshold the CPRs do not require entities to file a written justification for the use of limited tender procurement however, the procurement must still provide a value for money outcome. Non-exempt procurements9 at or above the relevant thresholds, must only be conducted by limited tender if one or more of the nine conditions specified in the CPRs are met.10 A written record of how the procurement represented value for money in the circumstance and the condition(s) which justified the use of limited tender must be maintained by entities in each instance. For the sample of 51 high value procurements examined by the ANAO, appropriate justification for adopting a limited tender was only provided in approximately two-thirds of cases. While the entities had documented how the procurements represented value for money in the circumstance for 41 (80 per cent) of the 51 high value procurements and for 89 (81%) of the total 110 procurements examined, documentation supporting these assessments, such as copies of requests for quotes, responses from all suppliers and evidence of evaluation, was not maintained for all the procurements.

20. Proper approval of expenditure is necessary to ensure that the spending of public money is efficient, effective, economical and ethical, and in accordance with government policy. However, evidence of approval being obtained prior to entering into the arrangements with the supplier was only found in 74 per cent of procurements reviewed.

Procurement Support, Review and AusTender Reporting (Chapter 3)

21. Many procurement processes involve complex requirements and judgements. It is important that entity officials have, or are able to draw on, guidance and training as well as relevant expertise such as central procurement units (CPUs), to enable them to carry out their procurement activities efficiently and effectively, and in compliance with government and entity requirements. Each of the audited entities had reasonable guidance, and officials with procurement responsibilities had access to training to assist them undertake procurements and meet AusTender reporting requirements. Each entity had a CPU (or equivalent arrangement) which officials could call on for advice. In addition, each of the audited entities had established a pre-approval compliance assurance mechanism whereby higher value limited tender procurements were required to be reviewed by the CPU prior to the spending proposal being provided to the relevant delegate. The CPU was to provide advice to the delegate as to whether the proposed approach was supported and compliant with the CPRs. Notwithstanding the availability of guidance; training and support from the CPU, 28 per cent of the procurements examined by the ANAO were in fact duplicate entries, grants or variations to existing contracts, that had been misreported on AusTender as new contracts resulting from a limited tender process.

22. As mentioned in paragraph 14, inconsistent and incorrect reporting of procurement information on AusTender diminishes the transparency of Commonwealth procurement. The results of this, and previous ANAO audits, highlight the need for entities to improve the accuracy and timeliness of contract notice reporting on AusTender. Entities are required to report contract details on AusTender within 42 days of entering into an arrangement. The details required include: the contractor name, subject matter, value, start and end date and the procurement method used. The ANAO examined the reported details of 155 procurements that had been reported on AusTender as being conducted by limited tender. Of these procurements, only 41 (26 per cent of the procurements), had all the basic contract details (supplier, subject matter, value and period) correctly specified and were reported on AusTender within the mandated 42 days.

Summary of entities’ responses

23. The audited entities summary responses to the audit report are provided below. Appendix 1 contains the entities’ full responses to the audit report.

Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

24. The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) agrees with both recommendations of the proposed report.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

25. DFAT welcomes the findings in this report as a means of continuing to improve procurement practices in the Department. DFAT notes that agreements audited were undertaken prior to the rollout of significant procurement reforms which came into effect on 1 July 2014 as part of the integration of the former AusAID and elements of the Tourism and Climate Change departments with DFAT and introduction of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act 2013. Following the establishment of a single centralised Contracting Services Branch, which provides the functions of a Centralised Purchasing Unit (CPU), a new procurement policy framework, underpinned by a range of guidelines, templates and tools was promulgated. The framework has standardised procurement practice and further instilled value for money principles and embeds compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) through procurement processes. Procurement reporting has also been centralised in DFAT’s CPU and improvements have been made to data capture, AusTender reporting systems and reporting compliance. DFAT considers that the reforms introduced to date have addressed many of the issues identified in this audit but as a matter of good practice will continue to review and refine its procurement policies and practices to ensure compliance with the CPRs.

Department of Human Services

26. The Department of Human Services welcomes this report and considers that implementation of its recommendations will support the work already being undertaken within the department to improve contract notice reporting and the correct application of the procurement method. The Department of Human Services agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations. The department has already completed, or is in the process of completing, a range of actions to enhancements to the ESSentials e-procurement system which will address a number of the issues raised within the report. In addition, the introduction of an inflight verification action will support the implementation of the recommendations, as will an increased emphasis on limited tendering in procurement training and guidance material.

Recommendations

These recommendations are based on findings at the audited entities and are likely to be relevant to other Australian Government entities. Therefore, all Australian Government entities are encouraged to assess the benefits of implementing these recommendations in light of their own circumstances, including the extent to which the recommendations, or parts thereof, are addressed by practices already in place.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.23 |

To assist delegates to make more informed decisions that support the achievement of value for money and increase compliance with the CPRs when conducting limited tender procurements, the ANAO recommends that entities review, and where necessary strengthen:

Responses from audited entities: Agreed Finance response: Supported |

|

Recommendation No 2 Paragraph 3.18 |

To improve the accuracy and transparency of Commonwealth procurement information on AusTender, the ANAO recommends that entities review their reporting arrangements, including quality checks, in order to improve the accuracy and timeliness of contract information reported on AusTender. Responses from audited entities: Agreed Finance response: Supported |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the legislative and policy framework applicable to government procurement and sets out the audit approach.

Background

1.1 Procurement is an integral part of the way the Australian Government conducts business and provides services. Throughout 2013–14, Australian Government entities published 66 447 contract notices for goods and services valued in excess of $49.5 billion.11 Given the large number of procurements undertaken and the centrality of this activity to the operation of government and program delivery, entities’ procurement practices are expected to be efficient, effective, economical and ethical, consistent with the Commonwealth legal and policy requirements, and commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

Legal and policy framework for government procurement

1.2 The Australian Government has in place a range of legislation and related policies that set out the framework for procurement and contracting. The framework underpins Australia’s international obligations in accordance with free trade agreements and is designed to promote sound and transparent procurement practices. In undertaking procurement, entities are required to adhere to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The CPRs are the keystone of the Government’s procurement policy framework and establish procurement principles that apply to all procurement processes. The CPRs are issued under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) by the Finance Minister and articulate the requirements for officials performing duties in relation to procurement.12

1.3 The PGPA Act came into effect from 1 July 2014. Prior to this expenditure of public monies was subject to the legislative requirements set out in the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997, the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 and the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997.

1.4 In addition to the requirements of the CPRs, section 20A of the PGPA Act authorises accountable authorities to give instructions (Accountable Authority Instructions) to officials in their entities on any matter necessary or convenient for carrying out or giving effect to the PGPA Act.13 These are legally binding instructions relating to the financial administration of entities. The Accountable Authority Instructions generally include details of the entities’ procurement policies, which may be supplemented by more detailed guidance covering the various phases of the procurement cycle in the context of the entities’ particular business environment.

1.5 The CPRs promote the use of sound and transparent procurement practices that seek to achieve value for money14 and encourage competition in government procurement. The CPRs describe three methods that officials can use when conducting procurements—these are:

- Open tender—involves publishing an open approach to market and inviting submissions;

- Prequalified tender—involves publishing an approach to market inviting submissions from all potential suppliers on:

- a shortlist of potential suppliers that responded to an initial open approach to market on AusTender;

- a list of potential suppliers selected from a multi-use list established through an open approach to market; or

- a list of all potential suppliers that have been granted a specific licence or comply with a legal requirement, where the licence or compliance with the legal requirement is essential to the conduct of the procurement; and

- Limited tender—which involves an entity approaching one or more potential suppliers to make submissions, where the process does not meet the rules for open tender or prequalified tender.15

1.6 The CPRs include mandatory requirements which entities must follow. The extent to which all rules of the CPRs apply depends on the value of the procurement and are set out in the two divisions of the CPRs:

- Division 1—rules applying to all procurements regardless of value. Officials must comply with the rules of Division 1 when conducting procurements; and

- Division 2—additional rules that apply to all procurements valued at or above the relevant procurement thresholds (unless exempted under Appendix A of the CPRs16).

1.7 The relevant procurement thresholds (including GST) for 2013–14, above which the additional procurement rules of Division 2 of the CPRs applied, were:

- $80 000 for relevant Commonwealth entities17, other than for procurements of construction services;

- $400 000 for relevant Commonwealth corporate entities, other than for procurements of construction services; and

- $9 million for procurements of construction services by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.18

1.8 In addition to the mandatory requirements, the CPRs also contain good practice elements which entities are encouraged to adopt. These provide guidance on what entities should consider when determining whether procurement will deliver the best value for money and the type of documentation entities should maintain to support each procurement.

Procurement documentation

1.9 The Australian Government emphasises the importance of being accountable and transparent in its procurement activities. Accountability means that officials are responsible for the actions and decisions that they take in relation to procurement and for the resulting outcomes. Under the CPRs, it is mandatory for entities to maintain appropriate documentation for each procurement undertaken. While the specific content of such documentation is not prescribed, the CPRs indicate that desirably, such documentation would include: concise information on the requirement for the procurement; the process that was followed; how value for money was considered and achieved; relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions.19 The appropriate mix and level of documentation depends on the nature and risk profile of the procurement being undertaken.

Use of limited tender

1.10 The focus of this audit is on entities’ use of the limited tender procurement method. Open tender and prequalified tender promote competition, whereas limited tender, as its name suggests, limits competition. Limited tender is the most commonly used procurement method and accounts for the greatest percentage of expenditure by entities. Under the CPRs, limited tender may only be used for procurements at or above the relevant thresholds under certain circumstances and conditions. Restricting the circumstances and conditions where limited tender can be used for high value procurements, means that competition is encouraged by opening up high value procurements to the market. Limited tender may also be used for procurements below the threshold providing value for money is being achieved. The number and value of procurements, by procurement method as reported by entities on AusTender20 between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2014 are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Number and value of contract notices by reported procurement method 2013–14

|

Description |

Number |

% by number |

Value $billions |

% by value |

|

Open Tender |

23 750 |

36% |

$18.9 |

38% |

|

Prequalified Tender |

5 336 |

8% |

$6.8 |

14% |

|

Limited Tender procurements under $80 000 |

29 022 |

44% |

$0.8 |

2% |

|

Limited Tender procurements at and above $80 000 |

8 339 |

13% |

$23.0 |

47% |

|

Total |

66 447 |

101% |

$49.5 |

101% |

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data.

Note (a): Percentages do not add to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Note (b): These figures are based on what entities have published on AusTender. As shown in this report misreporting on contract notices is common so actual results are different.

Parliamentary interest

1.11 Procurement is often an area of interest and review by Parliament. Most recently, the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee’s inquiry into Commonwealth procurement procedures explored the operation and effectiveness of the CPRs, as well as procurement related policies, as they relate to the participation of Australian companies and businesses. The inquiry also explored the impact of Australia’s international obligations arising from bilateral free trade agreements on procurement policies.

1.12 The committee formed the view that government procurement policies, as part of value for money assessments, should take into account the impact of procurement decisions on competition and on the broader economy, and made 15 recommendations to that effect. The Government has formally indicated support for the recommendations where they relate to the Department of Finance: working with Commonwealth entities to raise the general awareness of good procurement practice; learning from best practice from other jurisdictions; and improving the capability of officers providing procurement support. The Auditor-General also supported the Committee’s recommendations directed towards future ANAO audit activities, indicating that future procurement audits would focus on value for money including consideration of the financial and non-financial costs and benefits consistent with the revised.21

Previous audits

1.13 The ANAO has conducted five audits that have focussed on aspects of procurement across Australian Government entities since 2007.22 Each of these audits has identified shortcomings with respect to entities’ application of the CPRs23 for a significant proportion of procurements examined. In general, the audits have found that entities needed to employ more competitive procurement processes, better document value for money assessments and obtain appropriate approvals. In particular:

- Audit Report No.11 2010–11, Direct Source Procurement24 identified that for the majority of direct source procurements examined it was not evident that the requirements for limited tender had been met; and

- Audit Report: No.54 2013–14 Establishment and Use of Multi-Use Lists, identified that the majority of procurements examined, reported as prequalified procurements via a multi-use list, had actually been conducted as limited tender procurements and therefore did not meet the requirements of the CPRs and as a result did not promote effective competition.

Audit approach

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess whether selected entities had appropriately justified the use of limited tender procurement and whether processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules including the consideration and achievement of value for money.

1.15 The audit was undertaken in three entities which had reported on AusTender25 a high proportion of procurements conducted through limited tendering. The entities were the:

- Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS);

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT); and

- Department of Human Services (DHS).

1.16 The scope of the audit included an examination of the policies and practices supporting the use of limited tendering as well as the assessment of these entities’ records in respect to a sample of procurements.

1.17 To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO’s high level criteria considered whether the entities had adhered to the requirements of the financial management framework26; applied sound practices when undertaking procurements via limited tender; and established effective procurement support and review arrangements.27

1.18 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to ANAO of $462 660.

Report structure

1.19 The remaining structure of this report is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Limited Tender Procurement Processes |

This chapter examines entities’ decisions to procure goods and services through the use of limited tendering, and whether the procurement processes were sound and met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. |

|

Procurement Support, Review and AusTender Reporting |

This chapter examines entities’ arrangements to support procurement processes. These include procurement guidance and training and the role of central procurement units. It also examines the audited entities’ classification and reporting of procurements on AusTender and the associated implications for accountability and transparency of Australian Government procurement. |

2. Limited Tender Procurement Processes

This chapter examines entities’ decisions to procure goods and services through the use of limited tendering and whether the procurement processes were sound and met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Introduction

2.1 Applying the principles of value for money, encouraging competition, efficient, effective and ethical use of resources, and accountability and transparency in decision‐making is a requirement of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). Effective procurement is supported by entities clearly defining the objectives of any procurement and taking a considered approach to determining the procurement processes best suited to achieving their objectives.

2.2 The ANAO examined four key areas supporting the use of limited tender as a procurement method: procurement planning (including the need to estimate the value of the procurement); justification for the use of limited tendering; value for money; and approving the expenditure of public money. The ANAO reviewed a sample of the entities’ limited tender procurements which were published on AusTender from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. Detailed discussion on how entities performed against each of the four areas is set out below.

Procurement planning

2.3 When a business requirement arises for goods or services, entities need to consider whether procurement will deliver the best value for money solution having regard to such issues as non‐procurement alternatives, pre-existing arrangements28, prevailing market conditions, resourcing and business needs. If an entity determines that procurement represents the best option, the procurement principles and the estimated value of the procurement should inform the selection of an appropriate procurement method. Where entities use limited tender procurement, they must apply the procurement principles established in Division 1 of the CPRs regardless of the value of the resulting contract. Where the expected value of a procurement is at or above the relevant procurement threshold and an exemption under Appendix A29 does not apply, the rules in Division 2 (including meeting the conditions for limited tender set out below) must be followed.

|

Conditions for limited tender for procurement at or above the relevant procurement threshold Unless a procurement (at or above the relevant procurement threshold) meets the conditions outlined in paragraph 10.3 of the 2012 CPRs, an open or prequalified tender procurement process must be undertaken. 10.3 a. where, in response to an approach to the market i) no submissions, or no submissions that represented value for money were received, ii) no submissions that met the minimum content and format requirements for submission as stated in the request documentation were received, or iii) no tenderers satisfied the conditions for participation, and the agency does not substantially modify the essential requirements of the procurement; or |

|

10.3 b. where, for reasons of extreme urgency brought about by events unforeseen by the agency, the goods and services could not be obtained in time under open tender or prequalified tender; or 10.3 c. for procurements made under exceptionally advantageous conditions that only arise in the very short term, such as from unusual disposals, unsolicited innovative proposals, liquidation, bankruptcy, or receivership and which are not routine procurement from regular suppliers; or 10.3 d. where the goods and services can be supplied only by a particular business and there is no reasonable alternative or substitute for one of the following reasons i) the requirement is for works of art, ii) to protect patents, copyrights, or other exclusive rights, or proprietary information, or iii) due to an absence of competition for technical reasons; or 10.3 e. for additional deliveries of goods and services by the original supplier or authorised representative that are intended either as replacement parts, extensions, or continuing services for existing equipment, software, services, or installations, where a change of supplier would compel the agency to procure goods and services that do not meet requirements of compatibility with existing equipment or services; or |

|

10.3 f. for purchases in a commodity market; or 10.3 g. where an agency procures a prototype or a first good or service that is intended for limited trial or that is developed at the agency’s request in the course of, and for, a particular contract for research, experiment, study, or original development; or 10.3 h. in the case of a contract awarded to the winner of a design contest, provided that i) the contest has been organised in a manner that is consistent with these CPRs, and ii) the contest is judged by an independent jury with a view to a design contract being awarded to the winner; or 10.3 i. for new construction services consisting of the repetition of similar construction services that conform to a basic project for which an initial contract was awarded through an open tender or prequalified tender, and where the initial approach to the market indicated that limited tender might be used for those subsequent construction services. |

Source: Finance, CPRs 2012 paragraph 10.3.

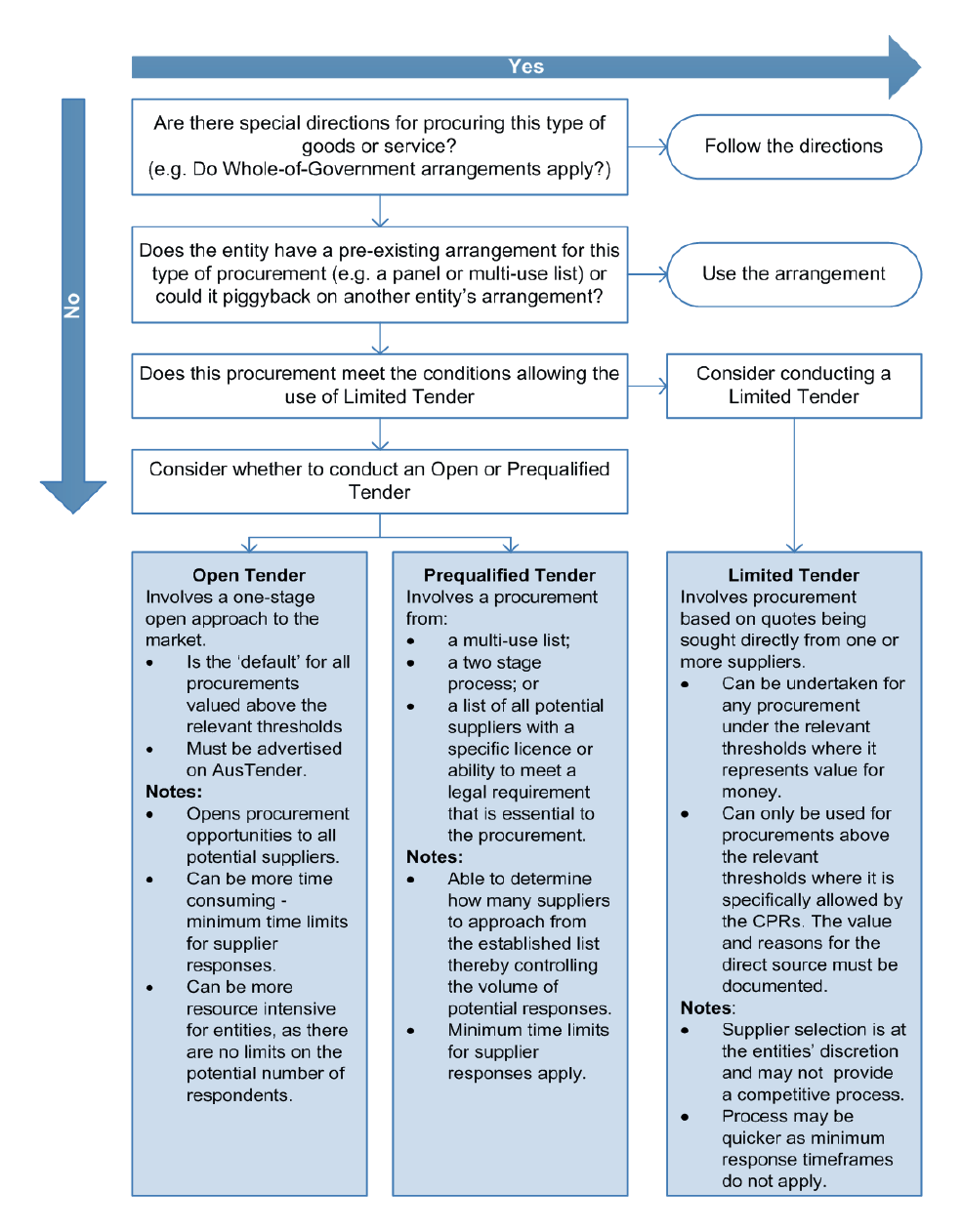

2.4 Typical considerations for procurements at or above the relevant threshold are outlined in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Choosing a procurement method

Source: ANAO based on Department of Finance guidance.

Consideration of coordinated procurement arrangements and procurement-connected policies

2.5 Having identified the procurement need entities need to determine whether the goods or services to be purchased are subject to any of the coordinated (whole-of-Australian Government) procurement arrangements and whether the Commonwealth’s procurement connected policies apply. These requirements apply to all procurement irrespective of the procurement method used.30

2.6 Whole-of-Australian-Government arrangements are broadly established to give effect to government policy decisions, to improve consistency and control and to deliver savings and efficiencies. Where the goods or services to be procured are subject to a coordinated procurement, the CPRs require entities to use the whole-of-government arrangement. Exemptions may only be granted jointly by the requesting entity’s Portfolio Minister and the Finance Minister where an entity can demonstrate a special need for an alternative arrangement.

2.7 Commonwealth procurement connected policies are policies for which procurement has been identified as a means of delivery and include policies relating to Australian industry participation, energy efficiency and indigenous opportunity. To assist entities in complying with these policies Finance maintains a list of them on its website.

2.8 Although entity officials are not required to document their consideration of whether any of these requirements apply, doing so can provide greater assurance to the delegate that the proposed procurement has considered all relevant requirements of the broader procurement framework.

2.9 The ANAO observed there was little documented evidence that entities considered whether the required goods or services were subject to such arrangements. Of the sample of procurements reviewed, there was only one procurement where a coordinated procurement arrangement (travel services) was relevant, but not used. In this instance, the entity had not sought an exemption as required. The supporting documentation for most of the procurements reviewed contained a generic statement to the effect that the proposed procurement process was consistent with the Commonwealth’s policies and in particular the CPRs. With the exception of two DHS procurements, none of the remaining procurements examined contained specific reference to the procurement connected policies.

Estimating the procurement value and determining the procurement method

2.10 The CPRs state that the expected value of each procurement must be estimated before a decision on the procurement method is made. The expected value is the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract.31 Having estimated the value of the procurement, officials need to determine the most appropriate procurement method; noting that for procurements at or above the relevant procurement threshold entities must conduct an open tender unless specific conditions are met. In addition, Finance’s guidance also advises officials to ensure the delegate is aware of the intended approach to market and, depending on the nature, complexity and risk of the procurement, is involved in the planning stages of the procurement.32

2.11 Each of the audited entities required that a procurement plan, business case or equivalent documentation, be prepared for approval by the delegate prior to an approach to market. The documentation was required to outline among other things: the procurement need; the estimated value of the procurement; the anticipated level of risk; and the proposed procurement method.

2.12 The ANAO assessed whether the entities’ planning documentation (for the sample of procurements undertaken as limited tender), demonstrated that the value of the procurement was estimated prior to approaching the market. The ANAO also assessed whether delegate’s approval for the intended approach had been obtained prior to going out to market. The ANAO’s analysis is summarised in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Demonstrated procurement planning considerations

|

|

ACBPS |

DFAT |

DHS |

Total |

||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Total number of limited tender procurements examined. |

41 |

37% |

38 |

35% |

31 |

28% |

110 |

100% |

|

Planning documentation contained an estimated value of the procurement.(a) |

32 |

78% |

31 |

79% |

30 |

97% |

93 |

85% |

|

The planning documentation provided evidence of the delegate’s approval prior to approaching the market. |

34 |

68% |

26 |

68% |

22 |

71% |

82 |

75% |

Source: ANAO sample testing.

Note (a): Estimates provided on the basis of quotes have not been included as this meant the procurement process was already underway, prior to the estimation of the procurement value.

2.13 Of the 110 limited tender procurements examined, the supporting documentation for 17 (15 per cent) did not demonstrate that the value of the procurement had been estimated prior to approaching the market. The estimate of the value of the procurement must be determined prior to approaching the market, as once an approach to market has been made it is too late to change the approach. In a number of cases, supporting documentation indicated the estimated value of the procurement was based on a quote that had been obtained prior to the spending proposal, with details of the intended procurement approach, being provided to the delegate for approval. As obtaining a quote is an approach to market, a limited tender procurement process had in effect already commenced prior to the delegate being provided with the opportunity to approve the planned approach to market. In some instances the spending proposal recommended that a limited tender procurement be conducted with the supplier that had provided the quote.

2.14 Involving the delegate33 early in more complex or high value procurements provides the delegate with the opportunity to influence the type of procurement process chosen. It further assists in gaining an assurance that the intended approach complies with the rules and principles established in the CPRs and is likely to achieve a value for money outcome. The delegate’s approval of the approach to market was only documented for 82 (75 per cent) of the procurements examined by the ANAO. None of the ACBPS procurements examined and only two of the DHS procurements examined were above the relevant procurement thresholds. In DFAT however 11 of the 12 procurements for which there was no evidence of delegate approval to approach the market were above the relevant threshold.34

Justification for the use of limited tendering

2.15 For procurements below the relevant threshold the CPRs do not require entities to file a written justification for the use of limited tender procurement. For such purchases, entities would normally follow established working arrangements such as obtaining a minimum number of quotes.

2.16 For limited tender procurements over the relevant thresholds (and not exempt under Appendix A of the CPRs) entities are required to prepare and file a written report that includes: the value and kind of property or services procured; a statement indicating the circumstances and conditions that justified the use of limited tendering; and a record demonstrating how the procurement represented value for money.35

2.17 Of the 110 procurements in the ANAO’s sample:

- fifty-five were below the relevant procurement threshold and therefore only subject to the Division 1 requirements of the CPRs;

- fifty-one (at a combined value of approximately $231 million) were above the relevant procurement threshold and subject to the requirements of both divisions of the CPRs and therefore required written justification; and

- four procurements were above the relevant thresholds however were exempt from the requirements of Division 2 in accordance with Appendix A of the CPRs.36

2.18 The ANAO assessed whether the audited entities had documented the circumstances and conditions that justified the use of limited tender and identified that for 37 of the procurements (73 per cent) appropriate justification was recorded. The results for each entity are provided in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Documented justification for limited tender procurements subject to Division 2 of the CPRs

|

Description |

ACBPS |

DFAT |

DHS |

Total |

||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Total number and per cent of sample procurements subject to Division 2 |

11 |

22% |

26 |

51% |

14 |

27% |

51 |

100% |

|

Number and per cent of entity sample procurements subject to Division 2 where justification for limited tender was provided.(a) |

8 |

73% |

15 |

55% |

14 |

100% |

37 |

73% |

|

Number and per cent of entity sample procurements subject to Division 2 where justification for limited tender was not provided |

3 |

27% |

11 |

42% |

— |

— |

14 |

27% |

Source: ANAO sample testing.

2.19 By far the most common justifications used for limited tendering were:

- where the goods and services can be supplied only by a particular business and there is no reasonable alternative or substitute for one of the following reasons i) the requirement is for works of art, ii) to protect patents, copyrights, or other exclusive rights, or proprietary information, or iii) due to an absence of competition for technical reasons (CPRs 10.3 (d)); and

- for additional deliveries of goods and services by the original supplier or authorised representative that are intended either as replacement parts, extensions, or continuing services for existing equipment, software, services, or installations, where a change of supplier would compel the agency to procure goods and services that do not meet requirements for compatibility with existing equipment or services (CPRs 10.3 (e)).37

2.20 These two reasons accounted for 89 per cent of the procurements reviewed where justification for limited tender was provided and were approximately equal in the frequency of use.

2.21 In the 27 per cent of cases identified in Table 2.2 the absence of a justification for limiting the approach to market in accordance with the CPRs makes it more difficult for entities to demonstrate that these procurements met the requirements of the CPRs and provided the best value for money. The ANAO observed examples of inappropriate use and/or justification for use of limited tender procurement in ACBPS and DFAT.

|

Inappropriate use and/or justification for use of limited tender procurement For one ACBPS procurement, with an approximate cost of $380,000, the supplier was selected based on a recommendation from a colleague in another entity. The justification provided was that the property or services could only be supplied by a particular business and there was no reasonable alternative or substitute due to an absence of competition for technical reasons (CPRs paragraph 10.3(d) iii). This was unlikely given ACBPS had an existing panel of providers for the type of service required. Advice to the delegate focussed on the potential impact on suppliers and reputational risk, however did not extend to advising the delegate that unless the conditions for limited tender outlined in the CPRs were met then an alternative procurement method (either an open or prequalified tender) would be required. For one DFAT contract, approval was sought to conduct an open approach to market by approaching suppliers on a DFAT panel. Despite approval being obtained for an open approach to market, DFAT procurement officials also requested a quote from a supplier not on the panel and already working in DFAT. This process, by default, meant that DFAT had actually conducted a limited tender. The non-panel supplier was engaged and the reported value of the contract on AusTender was approximately $524 000. Subsequent to this arrangement DFAT entered into two additional contracts with this supplier (both under the $80 000 threshold at approximately $72 000 and $74 000 respectively). Both these contracts were for less than a month and overlapped as both were undertaken in June 2014 for the same project services at a combined cost of $151 466. |

2.22 The CPRs require officials to maintain appropriate documentation for each procurement process they undertake. The CPRs indicate that desirably, such documentation would include: concise information on the requirement for the procurement; the process that was followed; how value for money was considered and achieved; relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions. In relation to limited tender at or above the relevant procurement threshold, the CPRs mandate that specific records be kept. The onus is on officials and delegates in particular, to meet the accountability and transparency principles, including for the purposes of enabling appropriate scrutiny. To assist in this regard, entities should reinforce that where limited tender is selected as the procurement method, it must only be undertaken where the conditions established in the CPRs are met and the required documentation is maintained.

Recommendation No.1

2.23 To assist delegates to make more informed decisions that support the achievement of value for money and increase compliance with the CPRs when conducting limited tender procurements, the ANAO recommends that entities review, and where necessary strengthen:

- pre-approval compliance assurance mechanisms; and

- supporting documentation including the estimated procurement value, the justification for using limited tender and how the procurement represented value for money in the circumstances.

Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

2.24 Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

2.25 Agreed. The implementation on 1 July 2014 of a standardised and comprehensive procurement policy framework across the newly integrated department focusses on achieving value for money (VFM) and compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPR) through competitive processes. Updated documentation — including delegate approval templates, procurement planning tools and guidance — articulates requirements to record the procurement need, estimated value, procurement process and how the method of procurement will achieve VFM. Centralised quality assurance and control mechanisms are now in place for procurements and limited sourcing is subject to CPR exemption approval processes. DFAT’s CPU also leads significant procurements based on value, risk and complexity thresholds. Procurement training and professionalization strategies are under development and will further enhance DFAT’s performance in this area.

Department of Human Services

2.26 Agree. The department notes the finding that a justification for a limited tender was provided in 100% of DHS sample procurements subject to Division 2. The department intends to continue this level of performance by ensuring procurement officers remain aware of limited tendering requirements with the introduction of training and guidance material that reinforce and support the limited tendering process.

Department of Finance

2.27 Supported. Adequate assurance processes and documentation are an important internal control mechanism to support delegates in their decision making processes relating to procurement.

Value for money

2.28 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. Delegates must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome. Value for money in Australian Government procurement requires:

- encouraging competitive and non-discriminatory processes;

- using Commonwealth resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth;

- making decisions in an accountable and transparent manner;

- considering the risks; and

- conducting a process commensurate with the scale and scope of the procurement.38

2.29 Value for money requires a comparative analysis of all relevant costs and benefits throughout the whole procurement cycle (whole-of-life costing). A whole-of-life value for money assessment includes consideration of factors such as: fitness for purpose, the experience and performance history of each prospective supplier, the flexibility to adapt to possible change over the lifecycle of the good or services; environmental sustainability financial considerations and the evaluation of contract options.39

2.30 The ANAO reviewed supporting documentation to assess whether audited entities had documented why procurements represented value for money. Generally the entities retained documentation indicating why the procurement represented value for money however, across the three entities documentation was not provided in 19 per cent of cases (21 procurements). Of these the majority (15 procurements) were from one entity ACBPS, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Documented value for money considerations for limited tender procurements

|

Description |

ACBPS |

DFAT |

DHS |

Total |

||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

%. |

No. |

% |

|

Total limited tender procurements |

41 |

37% |

38 |

35% |

31 |

28% |

110 |

100% |

|

Number and per cent of limited tender procurements where documentation supporting an assessment of value for money was provided to ANAO. |

26 |

63% |

34 |

89% |

29 |

94% |

89 |

81% |

|

Number and per cent of limited tender procurements where no documentation supporting an assessment of value for money was provided to ANAO.(a) |

15 |

37% |

4 |

11% |

2 |

6% |

21 |

19% |

Source: ANAO sample testing.

Note (a) This included situations where the entity could not provide any evidence to support a value for money assessment, and a few instances where the entity asserted that the procurement represented value for money but the assertion was not supported.

2.31 The ANAO found the most common documented considerations related to price, fitness for purpose and the potential suppliers experience and performance history (that is entities were confident the suppliers could undertake the work to an acceptable standard).40 The ANAO observed instances where contracts had been ongoing for periods ranging from 10 to 30 years during which time the entities had not reapproached or tested the market. This indicates a tendency to follow minimal processes when limited tendering. However, supporting documentation continued to indicate the entities were satisfied that value for money was achieved.

|

Examples of contracts where the absence of any recent approaches to market can make it difficult for entities to demonstrate value for money has been considered and achieved DFAT: Four DFAT contracts in the audit sample were related contracts with the same supplier. The initial procurement was for a commercial off-the-shelf software product. For the first of the procurements the reason for conducting a limited tender stated ‘the current approach follows an open approach to market in 2006 which failed to produce a desired result; which was followed by a direct approach in 2010 to the vendor of one of the previously offered products, which failed at the contract negotiation phase.’ The first contract in the audit sample was actually made under a work order pursuant to a master agreement with the supplier dated December 2000. The other three contracts were also work orders issued under the terms of the master agreement. The reported value of these four contracts was approximately $2.7 million. DHS: DHS reported a new contract on AusTender for approximately $189,534 for software licensing. Supporting documentation indicated DHS officials sought approval to enter into negotiations to initiate a new procurement via limited tender in 2013–14. The proposal sought to purchase additional rental of an existing product from the current supplier and to procure other products from the supplier that had been previously procured through a reseller. The condition supporting the use of limited tender cited was CPRs s.10.3(e).(a) Conditional support for the procurement approach was provided by DHS central procurement unit officials on the basis that while competing product suppliers existed, there was potential for a direct approach to obtain practical value for money. Rather than enter a new contract DHS actually varied an existing 1984 contract with the provider through an addendum executed in August 2013. ANAO comment: The ANAO considers that in both these cases, since an open approach to market had not been undertaken for many years (and in both cases it appeared alternative suppliers existed) it is difficult to demonstrate that conducting limited tender provided the best value for money. Further the 1984 contract was unlikely to offer the Commonwealth adequate protection, as it did not cater for the changes to standard Commonwealth contract which are currently in place. |

Note (a) For additional deliveries of goods and services by the original supplier or authorised representative that are intended either as replacement parts, extensions, or continuing services for existing equipment, software, services, or installations, where a change of supplier would compel the agency to procure goods and services that do not meet requirements for compatibility with existing equipment or services.41

Quotation practices

2.32 Approaching more than one supplier for quotes introduces an element of competition into a limited tender process and can assist entities in demonstrating which option achieved value for money in the circumstances. However, as other potential suppliers are excluded from the process it may not necessarily represent best value for money—other suppliers may have provided a better good or service at a more competitive price. In addition to obtaining multiple quotes, there are other activities that entities can undertake to enhance the likelihood of achieving value for money within the limited tender process. These include benchmarking costs for similar services received in the past, negotiating strongly for discounted pricing or additional services rather than accepting initial quotes provided, and periodically testing the market and reviewing whether alternative procurement arrangements could be used.

2.33 Procurement processes impose costs on both entities and potential suppliers. Entities should have regard to the scale, scope and relative risk of procurement in deciding what process ensures a competitive value for money outcome. Australian Government policy does not specify a minimum number of quotes to be obtained. Each entity’s guidance specified a minimum number of written quotes be obtained for purchases under $80,000.42 For procurements above the relevant threshold conducted by limited tender the guidance outlined the need to comply with the CPRs, but was not specific on how, if possible, to introduce competition within a limited tender process.

2.34 In the sample of limited tender procurements reviewed 41 per cent had no evidence of any quotes being obtained. The results of ANAO’s analysis are shown in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Number of quotes sought for limited tender procurements in the audit sample

|

Description |

ACBPS |

DFAT |

DHS |

Total |

||||

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

|

Total limited tender procurements examined |

41 |

37% |

38 |

35% |

31 |

28% |

110 |

100% |

|

No. and per cent of limited tender procurements where from available evidence no quotes were sought(a) |

25 |

61% |

18 |

47% |

2 |

6% |

45 |

41% |

|

No. and per cent of limited tender procurements where from available evidence one quote was sought |

2 |

5% |

9 |

24% |

12 |

39% |

23 |

21% |

|

No. and per cent of limited tender procurements where from available evidence more than one quote was sought |

14 |

34% |

11 |

29% |

17 |

55% |

42 |

38% |

Source: ANAO sample testing.

Note (a): These figures include situations where the entity did not seek quotes—including procurements under standing offer arrangements, and a few instances where the entity could not provide evidence that quotes were sought.

Note (b): Based on the contract amount as reported by the entities on AusTender (rounded).

2.35 In addition, while entities had documented their value for money considerations in a high number of cases, copies of all requests for quotes, all supplier responses and evidence of a comparison evaluation were often unable to be provided. Maintaining copies of all requests for quotes, supplier responses and evidence of a comparison evaluation where undertaken enhances the transparency of the procurement process and can be drawn upon by a delegate to help them gain assurance that a procurement is an effective, efficient, economical and ethical use of public money prior to granting their approval.

Approving the expenditure of public money

2.36 Officials who approve proposed commitments of public money must be satisfied that they have acted in accordance with the CPRs and not in a manner inconsistent with the policies of the Australian Government. The terms or basis of the approval be should be recorded. The approval can be recorded in many different forms including emails, electronic approvals in information systems, signed briefs or minutes or purchase orders. In addition, approval had to be obtained prior to the entity entering into the contractual arrangement.

2.37 For the sample of limited tender procurements, documentation forming procurement approvals was of varying standards, and often did not clearly set out the basis for delegates’ decisions. In addition, delegates were not always provided with key elements of the spending proposal, such as the items, cost, parties and timeframes. For example in ACBPS the internal processes for limited tender procurements relied on a one step approval approach. Under this process delegate approval was required to be obtained prior to approaching the market. Spending proposals would, among other things, set out the need for the procurement, details of the intended approach to market, an estimate of the cost and in some cases identify the potential supplier(s) to be approached. The approach adopted meant that approval for spending public money was obtained prior to the conclusion of the procurement process. As a result the delegate may not have been aware of the successful supplier and final cost of the procurement.

2.38 The ANAO also observed instances where, based on supporting documentation, delegates were incorrectly advised in relation to how the procurement process was to be conducted. For example in one instance in DFAT, approval was sought to conduct a limited tender and the delegate was advised that the intended approach was to directly email a specific supplier and request a formal written quote. However, DFAT officials had already approached and obtained quotes from other potential suppliers prior to seeking approval to approach the market and had also decided to limit the number of potential suppliers to Canberra based suppliers. The approach excluded any other potential providers who may have had the capability to provide the required services.43 In addition, in each of the audited entities there was often no evidence that request for quote documentation, supplier responses and to a lesser extent even a summary comparison of quotes, was provided to delegates when requesting their approval for the procurement.

2.39 The ANAO assessed how many of the procurements had evidence of approval, prior to entering into a contractual relationship with the supplier. The results are outlined in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Documented approval for limited tender procurements

|

Description |

ACBPS |

DFAT |

DHS |

Totals |

||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Total number of limited tender procurements examined |

41 |

37% |

38 |

35% |

31 |

28% |

110 |

100% |

|

Total number and per cent of limited tender procurements for which the entity maintained documentation of approval prior to entering the arrangement. |

32 |

78% |

34 |

89% |

15 |

48% |

81 |

74% |

|

Number and per cent of limited tender procurements where no documentation supporting approval prior to entering the arrangement. |

9 |

22% |

4 |

11% |

16 |

52% |

29 |

26% |

Source: ANAO sample analysis.

2.40 Entities need to ensure there is sufficient accurate and timely information provided to delegates. This information should detail on the nature of the procurement, cost, parties (supplier) and intended timeframe. Providing such information enables the delegate to make an informed decision on whether the proposed expenditure is an efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of resources and in accordance with government policy. Records of the approval should be sufficient to provide others with an understanding of decisions made and the basis of those decisions.

Ethical behaviour and conflict of interest considerations

2.41 Officials undertaking procurement for the Australian Government must act ethically throughout the procurement. Ethical behaviour includes the management of conflict of interest.44 Entities can reduce the risk of actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest, and the associated consequences for an entity’s reputation, by setting expectations for the behaviour of officials, such as through statement of values and a code of conduct.

2.42 The ANAO examined whether supporting documentation for a sample of 110 limited tender procurements demonstrated evidence of consideration of conflict of interest.

2.43 The CPRs do not mandate that conflict of interest considerations be documented. However, the need to be aware of and manage conflict of interest was raised in each of the entities guidance. From the sample of limited tender procurements reviewed, there was often no or minimal evidence of specific consideration of conflict of interest. In addition, as mentioned in paragraph 2.35 copies of all requests for quotes and all supplier responses were not available for all procurements examined. Maintaining such documentation assists entities demonstrate equitable treatment of suppliers and allows delegate or other officials to see the basis for selecting individual suppliers.

2.44 The ANAO observed in this, and previous audits, that some entities internal procurement processes for open tender procurement (above the relevant threshold), require members of the evaluation team to certify that no conflict of interest exists. However, the same formal requirement for limited tender procurement did not apply, notwithstanding the inherent risk that certain suppliers may receive favourable treatment and exclusive access to high value contracts. There is a need for entities to increase their focus on conflict of interest and the documentation of considerations made in this respect, particularly for limited tender procurement.

Conclusion

2.45 Value for money is enhanced through proper procurement planning that supports the selection of an appropriate procurement method through encouraging fair and open competition commensurate with the size, scale and risk of the procurement. When undertaking any procurement entity officials need to determine whether the goods or services to be purchased are subject to coordinated procurement arrangements and/or whether any of the Commonwealth procurement connected policies apply.

2.46 Estimating the expected value of a procurement is a key step in determining an appropriate procurement method. For high value or more complex procurements, involving the delegate early in the planned procurement approach can assist in ensuring the intended approach complies with the rules and principles established in the CPRs. The ANAO’s analysis of a sample of 110 procurements identified that planning documentation contained an estimated value of the procurement in 84 per cent of cases and there was evidence of delegate approval or clearance to approach the market in 75 per cent of the procurements reviewed.

2.47 For high value limited tender procurement entities must document the circumstances and conditions that justified limited tender and how the procurement represented value for money. For a sample of 51 high value procurements examined by the ANAO justification for limited tender was only documented in 73 per cent of cases. In addition evidence of a value for money assessment was only available in 81 per cent of cases. Furthermore, evidence of approval being obtained prior to entering into any arrangements with the supplier was only found in 75 per cent of procurements reviewed.

2.48 Overall these findings indicate that, to varying degrees, entities approaches were not fully effective in satisfying the procurement principles, including value for money and fair and open competition. Therefore entities need to better balance the broader benefits of competitive tendering with streamlined practices when undertaking procurement. Such a balance would see entities giving greater consideration to the scope of the potential procurement need at the outset and more often seeking opportunities to approach the market to enhance the potential to achieve value for money. It is important for entities to ensure that when adopting procurement processes, these are undertaken in a manner that consistently considers and addresses the objectives, rules and requirements of the government’s procurement framework

3. Procurement Support, Review and AusTender Reporting

This chapter examines entities’ arrangements to support procurement processes. These include procurement guidance and training, and the role of central procurement units. It also examines the audited entities’ classification and reporting of procurements on AusTender and the associated implications for accountability and transparency of Australian Government procurement.

Introduction

3.1 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) represent the Government’s policy framework under which entities conduct procurement. The CPRs are supported by guidance material prepared by the Department of Finance (Finance).45 Entities determine their own procurement practices, consistent with the CPRs, through Accountable Authority Instructions46 and, if appropriate, supporting operational guidelines. Entity central procurement units (CPUs)47 are internal units containing procurement specialists to advise entity officials in undertaking appropriate procurement processes and assist in ensuring relevant requirements are met.

3.2 Transparency is also a key principle of the Australian Government procurement framework. Transparency of Commonwealth contracts enables scrutiny of procurement activity. Generally transparency is facilitated through the disclosure of certain details of entities’ procurement activities, such as publishing details of approaches to market (including specifying if these approaches were open, prequalified or limited tender), the contracts awarded and their values on AusTender.48

3.3 For each audited entity, the ANAO examined available procurement guidance and training, and the role of the CPU. The ANAO also examined entity performance with respect to the reporting of contracts on AusTender.

Procurement related guidance

3.4 Clear, practical and current procurement policy and guidance is important to foster a good understanding of an entity’s procurement responsibilities, and to support the consistent application of sound practices throughout the entity. Delegates and entity officials must conduct procurements in accordance with the CPRs and their entity instructions and relevant operational guidelines which must be consistent with the CPRs. The extent that entity officials are involved in procurement can vary from regular to infrequent depending on the position held. This can pose a challenge for entities in providing an appropriate mix of guidance, training and support to meet the needs of officials with procurement responsibilities.

3.5 All audited entities had procurement instructions and guidance that reflected the requirements of the CPRs.49 In relation to limited tender specifically, entity instructions and procurement guidance on its use accorded with the requirements of the CPRs. Each entity periodically reviewed and updated guidance and made this available to all officials through internal intranets.

3.6 Entities are also expected to make appropriate training available to officials to enable them to understand the requirements of the CPRs and the entity’s specific requirements when conducting procurements. Each of the audited entities had formal procurement training available to officials on an as needed basis, with additional support available from their CPUs.

Role of central procurement units

3.7 CPUs are generally well placed to provide advice and support to officials undertaking procurements and identity opportunities to improve procurement practices through establishing efficient arrangements and practices that encourage competition and enhance value for money. Previous ANAO audits have commented on the benefits of entities maintaining a CPU to provide specialist advice and support when procurement responsibilities are devolved within the entity.50 Within the audited entities, procurement activities were generally devolved to individual business areas with support available from the CPU.

3.8 Procurement monitoring and review is an important activity for entities to determine the performance of their procurement activities and to inform future procurement planning and management. Common mechanisms entities may use to monitor and review procurement activities include review by CPUs and internal audit. For limited tender procurements over the relevant threshold, each of the audited entities required the procurement proposal to be reviewed by the CPU prior to being submitted to the delegate for approval. The nature of these reviews was to provide advice on whether the proposed approach was consistent with the CPRs and, in particular, whether justification for the use of limited tender appeared appropriate. Notwithstanding review by the CPUs not all of the procurements examined by the ANAO met the conditions for limited tender as outlined in the CPRs. This suggests that in some instances, entity officials and delegates have not fully understood the practical application of the Australian Government’s procurement framework, including the need to encourage competition through competitive procurement processes. Given the findings identified in this audit the ANAO considers there is scope for entities to strengthen their review arrangements as indicated in Recommendation No. 1 at paragraph 2.23.