Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project

The objective of this audit was to review the effectiveness of Defence's and the DMO's management of the acquisition arrangements for JP 2070.

Summary

Introduction

1. Lightweight torpedoes are self-propelled, underwater projectiles that can be launched from ships and aircraft and are designed to detonate on contact or in close proximity to a target. The Australian Defence Force's (ADF's) primary

anti-submarine capability is provided by its maritime patrol aircraft, embarked helicopters1 and surface platforms2. The lightweight torpedo is the main |anti-submarine weapon deployed on these platforms.

2. A Defence study concluded in mid-1990, that the lightweight torpedo ‘was the most cost and operationally effective anti-submarine warfare weapon in all situations'. In July 1997, the Defence Capability Forum concluded that there was a need to acquire a new torpedo because the ADF's existing Mark 463 lightweight torpedo had significant limitations and was not adequate for the ADF's needs.

3. Subsequently, in March 1998, Phase 1 of Joint Project 2070 Lightweight Anti-submarine Warfare Torpedo4 (JP 2070) was approved by Government5 to select and procure through subsequent phases, a replacement lightweight torpedo, procure associated support systems, and integrate the torpedo onto the following ADF platforms:

- Adelaide Class Guided Missile Frigates (FFGs);

- ANZAC Class Frigates (ANZAC ships);

- AP-3C Orion Maritime Patrol aircraft (Orion)6;

- S-70B-2 Seahawk helicopters (Seahawk)7; and

- SH-2G(A) Super Seasprite helicopters (Super Seasprite).8

4. The Super Seasprite was removed from JP 2070's scope in March 2008 when the Government took the decision to cancel that project. Subsequently, in February 2009 the Orion and the Seahawk were also removed from the scope of the approved phases of JP 2070. Accordingly, the currently approved phases involves integration of the replacement lightweight torpedo with only the two surface platforms, the FFG and ANZAC ships.

5. The procurement approach adopted for JP 2070 was one of the Defence Materiel Organisation's (DMO's) first attempts at conducting a major capital equipment acquisition using an alliance contracting model.9 As a consequence of it being a prototype alliance10, JP 2070 carried additional project and contract management overheads in the establishment and initial management phases.

6. JP 2070, as currently approved by Government, is divided into three phases. A fourth phase was proposed in the Defence Capability Plan: Public Version 2009 but was later deleted in the February 2010 update to that plan. The three approved phases are as follows:

- Phase 1, which focussed on selection capability analysis and costing;

- Phase 2, which involves the initial acquisition of torpedoes and integration of the torpedo onto the ADF platforms; and

- Phase 3, which primarily involves the acquisition of a larger quantity of torpedoes referred to as war stock.11

7. The total budget for all three approved phases of JP 2070 is $665.48 million.12 Phase 1 was completed in April 2001 and only represented a very small proportion of the total budget for JP 2070 ($4.96 million or 0.7 per cent of the total budget). Phase 2 (with a budget of $346.71 million January 2010 prices) and Phase 3 (with a budget of $313.82 million January 2010 prices) were both ongoing at the conclusion of this audit. As at February 2010, the DMO had spent $397.51 million of the combined approved budget for JP 2070. Some 12 years after JP 2070 commenced, and nine years after Government approved Phase 2, which was to buy an initial batch of torpedoes and integrate the torpedo onto five ADF platforms, the Project is yet to deliver an operational capability.

8. The Project is managed by the Guided Weapons Acquisition Branch within the Explosive Ordnance Division of the DMO. The Explosive Ordnance Division was established in February 2008.

The Torpedo

9. Following Phase 1 of JP 2070, a Project Definition Study, the MU90 lightweight torpedo was selected as the new light weight torpedo for the ADF. The MU90 is being acquired through Phase 2 and Phase 3 of JP 2070, which were subject to separate Government approvals in May 2001 and November 2003 respectively. The MU90 is being developed by the EuroTorp (GEIE)13 consortium, which is comprised of the companies that had been developing separate lightweight torpedoes for France and Italy.14 Defence is acquiring four versions of the MU90 torpedo under JP 2070, to cover the torpedo's combat-oriented role and the associated roles of practice and training:

- War-shot MU90 Torpedo (TC)–the TC is the combat version of the MU90.

- Exercise MU90 Torpedo (TVE)–the TVE has the same mechanical and electrical interface and physical representation as the TC, but has an exercise section in lieu of a warhead. The TVE enables evaluation of the MU90 using practice firings, and is used to verify in-water performance.

- Practice Delivery Torpedo (PDT)–the PDT is carried and launched, but is not propelled. It comprises the same mechanical and electrical interfaces and physical representation as the Exercise MU90 torpedo. It will record preset data for analysis of ‘weapon firing'.

- Dummy Torpedo (DT)–the DT can be carried and launched, but is not propelled. It has no recovery system and is not watertight. It has the same mechanical interfaces and physical representation as the MU90 TC.

Audit approach

10. The objective of this audit was to review the effectiveness of Defence's and the DMO's management of the acquisition arrangements for JP 2070. The high-level criteria for the audit were as follows:

- risks should be clearly defined at all stages in the capability development lifecycle, and processes should be in place to monitor and respond to risks as they emerge;

- the tender selection process should involve rigorous analysis of options against clearly defined requirements, to ensure that value for money is achieved;

- contractual arrangements should clearly define requirements, appropriately allocate risks, and facilitate the effective conduct of the acquisition;

- testing and evaluation requirements, to facilitate the transition into service of the capability being acquired, should be identified and progressively addressed as the acquisition proceeds; and

- appropriate project governance, financial controls, and reporting mechanisms should be in place.

11. At the commencement of this audit it was intended to also include within the audit's scope consideration of technical regulatory and in-service support arrangements. However, once the status of JP 2070 in terms of torpedo delivery, platform integration and introduction into service was established, we concluded that these areas were not sufficiently mature to provide the basis for an audit opinion.

Overall conclusion

12. JP 2070 is a complex project. It involves the acquisition of a new weapon and the integration of the weapon onto multiple platforms, albeit that over the life of JP 2070 the number of platforms included in JP 2070's scope has been reduced from five to two. There have also been significant interdependencies between this project and other projects related to the platforms onto which the new lightweight torpedo was and is to be integrated. To effectively complete JP 2070, Defence needed to have in place from the outset appropriate risk management processes to identify, monitor and address risks to the project. However, there have been significant weaknesses in the Defence's risk management of JP 2070.

13. Several key areas of risk that have emerged or gained increasing significance over the life of the project include:

- Initial costing of Phase 2 of the JP 2070 was not sufficiently rigorous or subject to adequate scrutiny. This has had ongoing implications for project progress, and ultimately was a factor that contributed to a significant reduction in the capability to be delivered by Phase 2, particularly through the removal of all air platforms from the approved phases of JP 2070.

- Project planning and management was inadequate, and in some instances key project documents were either not developed, or were not developed on a timely basis. This has inhibited the orderly conduct of the procurement and, ultimately, the delivery of the capability.

- The decision to use alliance contracting arrangements for JP 2070 was not based on structured analysis of contractual options, and once implemented was not adequately supported. The alliance arrangement for this project has generated additional risk to this acquisition, did not mitigate risks it was intended to address, and shifted management focus away from project deliverables without demonstrating measurable benefits to project outcomes.

- An inadequate understanding of the weapon and its development status over the period 1999 to 2004 contributed to an underestimation of project risk. At the conclusion of Phase 1 of JP 2070, Defence and DMO15 believed the MU90 to be an off-the- shelf acquisition of a torpedo that was already in-service with the other navies.16 This was not the case. Subsequently, issues identified through production testing of the torpedo contributed to schedule slippage and invalidated planning assumptions with ongoing implications for testing and evaluation.

- The risk involved in integrating the weapon onto multiple platforms was acknowledged, but not fully appreciated at the outset, and was compounded by a range of factors as JP 2070 progressed. These included a significant underestimation of the full cost to integrate the weapon onto the various platforms, the absence of defined and developed integration solutions for the air platforms during the time they were in JP 2070's scope, and delays and difficulties being encountered by other projects that were upgrading the platforms with which the torpedo was to be integrated.

- The planning of testing and acceptance, and the resolution of testing and acceptance issues for JP 2070, by the DMO has been inadequate. This has impeded the transition of the torpedo, and associated surface platform modifications, into Navy Operational Test and Evaluation.

14. The fundamental purpose of a major capital acquisition is to provide the ADF with a new or enhanced capability, to schedule and within the approved budget. Therefore capability delivery, schedule achievement and cost control represent key indicators of how effectively the DMO has conducted a major capital acquisition. An assessment of JP 2070 against these key indicators shows that the acquisition of the replacement lightweight torpedo has not been managed effectively, as the project:

- will not deliver the capability originally sought by the ADF, with uncertainty surrounding what will be delivered; • has not achieved schedule, with the successful completion of a range of ongoing activities essential to providing certainty regarding when the capability will be released into Navy service; and

- remains within budget, but this has been achieved by removing three of the five platforms17 that were originally intended to be integrated with the torpedo from the scope of Phase 2 (in 2008 and 2009)18, with ongoing uncertainty surrounding the likely cost of those elements that remain within scope of JP 2070.19

15. In 2003, Defence requested the then Government to bring forward the decision on Phase 3 from an originally planned year of decision of 2005 06, with the Government subsequently approving Phase 3 in November 2003. However, the contract for Phase 3 of JP 2070 was not actually executed until August 2005. By the time the contract for Phase 3 was signed, Phase 2 had already been identified by the DMO as a ‘Project of Concern' and was known to be encountering capability, schedule and cost difficulties. Some of these issues, relating to the integration of the torpedo onto the air platforms, were not overcome before the Government agreed to reduce the scope of JP 2070 in February 200920 to exclude all air platforms21. Other issues, primarily related to test and evaluation necessary for operational release of the torpedo and the ship borne lightweight torpedo systems, continued to represent ongoing risks to capability delivery at the completion of this audit.

16. All of the significant issues surrounding Phase 2 were known at the time the contract for Phase 3 was signed in August 2005. Under this contract the Commonwealth was committed to an additional $263.86 million (December 2005 prices)22 in expenditure to purchase additional war stock quantities of the torpedo over the $179.56 million (December 2005 prices) committed under Phase 2. The primary basis for the DMO committing to Phase 3 in August 2005, notwithstanding the known issues surrounding Phase 2, was that the Phase 2 contract placed the DMO in a such a weak negotiating position23 that it was DMO's commercial assessment that it was necessary to use Defence's commitment to Phase 3 work as leverage to improve the Defence's poor overall contractual position.24

17. Two recent reviews of Defence procurement, the Defence Procurement Review 2003 and the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review 2008, advocate the increased use of off-the-shelf acquisitions to reduce project risk. The Defence White Paper 2009 confirmed the Government's decision that Military-off-the-Shelf (MOTS) and Commercial-off-the-Shelf (COTS) solutions to Defence's capability requirements will be the benchmark going forward.25 The experience of this project identifies that claims surrounding the development status of a product offered (as MOTS or COTS) require verification to confirm that what is being offered is actually off-the-shelf. Additionally, where claims about the development status are verified, the method of integration also requires close consideration as this may introduce developmental risk to a project.

18. The Defence Procurement Review 2003 and the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review 2008 both also recommend the use of alternative contracting methods such as alliance contracting. This project demonstrates that alliance-style contracts cannot assure project success by and of themselves. Careful consideration is required at the outset of a project to determine the most appropriate procurement approach for each project, including the suitability of the acquisition to an alliance arrangement. Where an alliance contracting approach is adopted, appropriate governance arrangements need to be in place.

19. At the conclusion of the audit, the full cost of the approved phases of JP 2070 could not be reliably identified as the JP 2070 budget and scope was subject to further revision, with Defence intending to seek approval from the Government to release additional funding to complete integration of the weapon onto surface ships and undertake other activities. A range of important deliverables under Phases 2 and 3 are yet to be completed.26 The timeframe for the Navy achieving an operational capability has been defined in an April 2010 Materiel Acquisition Agreement, although the transition into and out of Navy Operational Test and Evaluation continued to be an ongoing risk to JP 2070.27 This was 13 years after the Defence Capability Forum concluded that the existing lightweight torpedo needed to be replaced, 12 years after JP 2070 commenced, and nine years after Government approved Phase 2.

20. It is not uncommon for major capital acquisitions to encounter cost, schedule and capability difficulties. When this occurs, evaluating these difficulties from the perspective of earlier decisions and approaches is likely to provide insight into how similar circumstances might be avoided in the future. In any case, it remains the ongoing responsibility of the procuring agency to deliver the best possible project outcomes to the Commonwealth. In situations where a defence project languishes between acquisition and capability delivery, the ADF is denied the capability being sought, resources may be tied up for extended periods, and future planning decisions involving significant expenditure may be impacted due to the interrelationship with other projects. Where circumstances that impact on project performance arise, they should be readily detectable through the ongoing performance monitoring mechanisms in place. However, this project demonstrates that, in respect of Defence major capital equipment acquisition projects, it remains the case that further enhancement of these reporting and monitoring mechanisms is required to properly inform decision making by both Defence and Government.

Key findings by chapter

Project Management (Chapter 2)

Phase 1

21. JP 2070 commenced with a Project Definition Study under Phase 1. Phase 1 had a total approved budget of $4.961 million. The Project Definition Study was intended to reduce integration and schedule risk, refine costs, and provide Defence with a sufficient understanding of the options for the acquisition phase of JP 2070. Phase 1 commenced with the release of a Request For Proposal (RFP) to companies that had responded to an earlier Invitation to Register Interest.

22. The RFP closed in July 1999, with four proposals received. The responses to the RFP were reviewed by three Proposal Evaluation Working Groups which each prepared reports for the Proposal Evaluation Board. The Board was tasked with reviewing the reports and endorsing the Source Evaluation Report. The Source Evaluation Report ranked an offer by Thomson Marconi Sonar Pty Ltd for the MU90 torpedo as the preferred option.28

23. In October 1999, the Defence Source Selection Board recommended the sole-source of the supplier of the MU90, Thomson Marconi Sonar Pty Ltd, to undertake the Project Definition Study. This recommendation was subsequently approved by the relevant Defence delegate. Through this decision Defence effectively removed all competition to the MU90 from consideration in the subsequent acquisition phase.

24. Two key factors influenced Defence's decision to sole-source the Project Definition Study for JP 2070. These were the desire to achieve Australian industry involvement in the project and the perceived development status of the MU90, relative to the other torpedoes offered. Australian industry involvement was an ongoing driver for decisions surrounding JP 2070; the number of torpedoes contracted in August 2005 for acquisition under Phase 3 was exactly the same as the number required29 to make manufacturing the MU90 in Australia no more expensive than making it in Europe. The desire to maintain local industry involvement was a factor taken into consideration in bringing forward the request to Government for approval of Phase 3, and deciding to enter into a contract for Phase 3 in August 2005 at a time when Phase 2 was experiencing significant difficulty.

25. The Source Evaluation Report indicated that the MU90 was regarded as being the most developed weapon of the four torpedoes considered. Further the report indicated that it was an ‘off-the-shelf' acquisition. The then Minister was informed in late 1999 that the MU90 had been selected and that it was the only ‘in-service' weapon offered. An ‘off-the-shelf' weapon carries a different acquisition risk profile to a weapon that is in the earlier stages of development. Defence's belief that the weapon was in-service subsequently proved to be misplaced.30 However, it took several years for the DMO to identify this, and during this time Defence committed under Phase 2 to acquiring the MU90 and modifying the associated ADF platforms to integrate the torpedo onto them.

26. The Project Definition Study was accepted by Defence in April 2001. One month later the Government approved Phase 2 of JP 2070 as part of the 2001 02 Federal Budget, at an approved cost of $287.71 million (December 1999 prices). Phase 2 was planned to commence in 2001 and be completed by 2008. Six months after the Government approved the budget for Phase 2, the Defence Capability Investment Committee selected an option that involved a reduced statement of work. Phase 2 was to acquire an initial batch of war-shot, exercise and dummy torpedoes; integrate the torpedo onto ADF Anti-Submarine Warfare platforms31 and acquire logistic elements necessary to support the MU90 torpedo.

Phases 2 and 3

27. Phase 2 of JP 2070 has been subject to a number of reviews that identified significant issues with project management. By mid-2004, Phase 2 was listed as a ‘Project of Concern'32 due to ongoing concerns surrounding schedule, uncertainty surrounding capability requirements and cost risk associated with integration of the torpedo onto the air platforms. In 2003, it was acknowledged that Defence had sought approval from Government for Phase 2 long before it was ready.33 A 2004 DMO review commented that JP 2070 had not followed the 'Project Management 101 Rulebook' and that there was no excuse for not implementing sound project management and engineering principles. In 2005, the JP 2070 Project Management Stakeholders Group noted that even the capability development documentation that would have normally been required to be produced under the less stringent ‘pre-Kinnaird' capability development process had not been produced.

28. The originally planned year of decision by the Government for JP 2070 Phase 3, which is acquiring a war stock quantity of MU90 torpedoes, was 2005 06. From as early as October 2001, the DMO was considering bringing forward the decision for this phase. In 2002, the Vice Chief of the Defence Force agreed to bring forward the request for Government approval of Phase 3 to realise a two per cent saving associated with the costs of the manufacturing component of JP 2070. Phase 3 of JP 2070 was approved by the then Government with a budget of $246.431 million in November 2003. In early August 2005, shortly before the contract for Phase 3 was signed, the then Minister was informed that the anticipated savings to have been achieved by proceeding to Phase 3 earlier than originally planned, would not in fact be realised.

29. At the time the Government approved Phase 3, no torpedoes had been delivered under Phase 2, and the integration of the torpedo onto the FFGs and the three air platforms had made limited or no progress.34 A DMO review in December 2004 expressed concern surrounding the apparent rush to lock in Phase 3, rather than address outstanding deliverables within Phase 2. The review suggested that the Commonwealth should delay Phase 3 until all Phase 2 issues surrounding Intellectual Property, acceptance, scope and platform integration were resolved. The contract for Phase 3, the Further Revised Alliance Agreement (FRAA), was executed in late August 2005, two years after the Defence Procurement Review 2003 (Kinnaird Review). Through the development and implementation of the FRAA, the DMO addressed some of the contractual issues affecting the Project that had been identified in the December 2004 review. However, the report of that review also acknowledged that the review had limitations due to time and resource constraints, and suggested that the adoption of the recommendations contained in the review may identify further issues.

30. The introduction of Materiel Acquisition Agreements was an initiative implemented in the DMO following the Defence Procurement Review 2003. A Materiel Acquisition Agreement is an agreement between the Capability Development Group and the DMO, which states in concise terms what services and products the DMO will deliver. As part of the DMO's preparation for becoming a prescribed agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997, a due diligence analysis was undertaken resulting in the June 2004 Due Diligence Report. That report indicated the DMO was not in a position to the sign a Materiel Acquisition Agreement for JP 2070 due to un-costed work for platform integration. However, a Materiel Acquisition Agreement for Phase 2 of JP 2070 was subsequently signed in June 2005, at which time the costing of the platform integration work had not been resolved. In March 2010, the DMO informed the ANAO that the requirement to execute a Materiel Acquisition Agreement in June 2005 arose because the DMO was to become a Prescribed Agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 in July 2005.

31. The June 2005 Materiel Acquisition Agreements for JP 2070 set out the Measures of Effectiveness of the Acquisition.35 The eight Measures of Effectiveness included in the June 2005 agreement fell into three broad categories, two of which were fundamental indicators of the success of Phase 2. JP 2070 did not succeed against these two Measures of Effectiveness for the three air platforms originally in the scope of Phase 2.36 All air platforms were removed from the scope of JP 2070 Phase 2 by early 2009.

32. Until shortly before this audit was finalised, there was not an up to date Material Acquisition Agreement in place for either Phase 2 or Phase 3 of JP 2070 and, in respect of Phase 2, this had been the situation for some years. This was the case notwithstanding that Phase 2 is listed as a ‘Project of Concern'. Defence advised that, in the interim, JP 2070 milestone dates were those proposed by Defence, and subsequently agreed to by the National Security Committee of the Cabinet, in early 2009. Subsequently, the DMO advised the ANAO that Materiel Acquisition Agreements were being drafted and on 16 April 2010 revised Materiel Acquisition Agreements for both Phase 2 and Phase 3 were signed.

Contract Management (Chapter 3)

33. Project alliancing is an agreement between two or more parties involving: a sharing of risks and rewards; a no -fault/no-blame arrangement to resolve most issues; a joint leadership arrangement; and a payment arrangement where a contractor receives reimbursement of direct project costs and a fee for overheads and profit combined with a pain/gain share arrangement based on project performance.

34. In November 1999, the Defence Source Selection Board decided that an innovative contracting approach would be used for the JP 2070 Phase 1 Project Definition Study. Following receipt of legal advice, the Director Undersea Weapons Group in the then Defence Acquisition Organisation37 sought approval in December 1999 to adopt an alliance approach for the Project Definition Study. This was two months after the decision had been made to sole-source the Project Definition Study, meaning that suitability as an alliance partner was not considered as part of the evaluation of the proposals entities had submitted in response to the RFP. It is generally accepted that an assessment of the suitability of an entity to perform in an alliance arrangement is an important factor to be considered prior to entering into this style of contract. A number of internal Defence and DMO audits and reviews of JP 2070 conducted between 2000 and 2003 reaffirmed this view.

35. In December 1999, the Head of System Acquisition (Maritime and Ground) in the Defence Acquisition Organisation approved the alliance contracting approach for Phase 1. In April 2000, an alliance agreement was executed for the Phase 1 Project Definition Study, with JP 2070 becoming the first Defence project to pilot alliance contracting. This alliance is known as the Djimindi Alliance and is comprised of the Commonwealth of Australia, Thomson Marconi Sonar Pty Ltd (later Thales Underwater Systems) and EuroTorp GEIE. At the time the decision was taken to adopt an alliance approach for JP 2070, it was acknowledged in Defence that this would result in additional costs for the project, particularly in the absence of a Defence alliance contract template.

36. Under the Phase 1 Alliance Agreement, two representatives from each of the Alliance Participants formed the Djimindi Alliance Board. The alliance representatives on that Board were required to be authorised to bind any party with respect to any matter within the power of the Board. However, the Defence representative at the time was not delegated to make decisions that bound the Commonwealth, which was seen as disempowering the Board. The Alliance Board was prohibited from making decisions surrounding operational capability without first consulting Defence. As a result a Capability Board was established38 . The Alliance Board and the Capability Board were supported by an Operational Working Group.

37. The Alliance Management Team, which comprised personnel from all Alliance Participants was responsible for tasks assigned to it by the DMO or the Alliance Board. This team was also responsible for the administration of all alliance sub-contracts and sub-alliances.

38. Under the Phase 1 Alliance Agreement, gainshare was defined as ‘a risk/reward payment made to or paid by the Alliance Participants, in addition to the Milestone Payments'. The payment of gainshare under Phase 1 was dependent on performance assessed against Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). A 2003 Defence internal audit commented that the measures of success against certain KPIs were very subjective, and that the assessed standard of achievement against the Integration Planning KPI was not supported. The costing of integration of the torpedo onto ADF air platforms developed under Phase 1 was later identified as inadequate, with significant implications for JP 2070 and the achievement of the desired capability.

39. The Phase 2 Alliance Agreement, referred to as the Revised Alliance Agreement, was signed on 4 December 2002 and is an extension of the Phase 1 Alliance Agreement. The Revised Alliance Agreement took more than twelve months to negotiate. This extended negotiation period was inconsistent with advice provided to the delegate at the time of approving the Phase 1 Alliance Agreement that indicated the Phase 1 agreement could be seamlessly amended to include the Phase 2 acquisition, if and when required. In the period following the conclusion of Phase 1 and preceding the execution of the Phase 2 Alliance Agreement, a number of activities for JP 2070 were approved involving just under $2.8 million in expenditure.

40. The Revised Alliance Agreement only included a high-level Scope of Work, with a 2003 Defence internal audit commenting that this could lead to significant changes in agreed baselines, cost schedule and technical requirements. At the time of the 2003 audit, six months after the Revised Alliance Agreement was signed, Measures of Success for the Phase 2 KPIs had not been agreed. That audit report also found that many of the Phase 2 activities had not been achieved, and that redrafting the agreement for Phase 3 could be complex.

41. In mid-2003, Defence commissioned an external review of the alliance contracting approaches that the DMO had adopted for this project, and for the ANZAC Ship Project. The review found that DMO rushed into the alliance arrangements for both projects without due consideration of the issues involved. The review identified that many of the problems experienced could have been avoided, or mitigated, if the projects had resulted from a structured procurement process. The review found that Defence's procurement guidelines for alliance contracting had not been followed in relation to JP 2070. Defence commented to the ANAO that the alliance for JP 2070 was established before these guidelines were available. The ANAO notes that this is correct in regard to Phase 1, but that the guidance was available at the time the Revised Alliance Agreement for Phase 2 was executed.

42. There were also a range of significant cultural issues impacting on the alliance arrangements. These were summarised by an alliance facilitator to the Alliance Board in late 2001. The Board acknowledged that these observations were of great concern and that there was a need to take action to address the issues. Consistent with the observations of the facilitator which indicated a degree of uncertainty surrounding the alliance arrangements, some six months later in July 2002, the Weapons Project Governance Board noted it had trouble understanding the alliance. That Board raised concerns surrounding the interaction and integration across five platforms. Given that this Board was to provide external oversight of JP 2070, these statements suggest a high level of uncertainty surrounding the alliance at an important juncture for JP 2070. Five months later, in December 2002, the Phase 2 Revised Alliance Agreement was signed committing the Commonwealth to significant additional expenditure.

43. A Defence internal audit in mid-2003 noted that the alliance had a number of deviations from a traditional alliance model. The DMO commissioned external consultant report, also from mid-2003, notes that, while deviations from the pure alliancing model did not mean that the alliance would be ineffective, there was a need to manage expectations that the arrangement would deliver all the alliance benefits when it was not structured in a way that would result in genuine alliance behaviours. That consultant's report stated that the alliance for JP 2070 was providing better outcomes than a traditional contract; however, this view was based on anecdotal evidence and subjective assessments, and was not supported by a comparative analysis to more traditional contracting approaches. In this circumstance, the conclusion that the alliance approach was delivering better outcomes for this project was not based on substantive evidence and therefore could not be regarded as a sound basis for decision-making.

44. Following Government approval of Phase 3, the Alliance Management Team prepared a business case outlining the acquisition options for Phase 3 in June 2004. This business case provided three options, two of which represented a more traditional contracting approach. The preferred option outlined in the business case was an extension of the Phase 2 Revised Alliance Agreement, which was seen as providing advantages over the other options. These advantages included that it was estimated to be the lowest price option and was assessed as the lowest risk option. In July 2004, the DMO accepted the Alliance Management Team's recommendation. In April 2010, DMO informed the ANAO that this recommendation was only partly implemented as Phase 3 was only included in the Further Revised Alliance Agreement for Phase 2 and Phase 3 following the inclusion of improvements in this contract compared to the existing contract.

45. In December 2004, the report of a DMO Red Team review39 of JP 2070 stated that the Commonwealth may have lost direct control of the acquisition due to the nature of the alliance, and that this was a factor behind many of the issues affecting JP 2070. Delays in achieving Phase 2 work resulted in the DMO deciding that the Further Revised Alliance Agreement, to be developed to encompass Phase 3 as well as remaining Phase 2 activities, should include more commercial-style conditions and that aircraft integration should be removed from contract scope. Factors that contributed to this decision included a lack of clarity surrounding the scope of work; a lack of clarity surrounding the Alliance Participants' respective responsibilities; a lack of clarity surrounding the price basis for Phases 2 and 3; and an inability for the Commonwealth to claim damages under the extant alliance agreement.

46. Negotiations for the Further Revised Alliance Agreement (FRAA) commenced in April 2005 and were completed on 31 August 2005, nearly two years after the Government approved Phase 3. The report on the FRAA negotiations indicated that, under the agreement, the Industrial Participants in the Alliance would have a firmly established scope of work on a fixed price basis with risk spread more equitably between the Commonwealth and the Industrial Participants. The FRAA was seen as improving Defence's commercial position by moving away from an alliance arrangement. A consequence of the arrangements introduced under the FRAA was that a considerable body of project work transferred to the DMO Project Office from the Alliance Management Team.

47. Defence documentation indicates that Phase 3 was used as leverage to negotiate improved contractual arrangements for Phase 2. However, the DMO was unable to provide the ANAO with either a business case or specific legal advice to underpin the decision to use the Commonwealth agreeing to enter into Phase 3 (and so commit to more than $263 million in 2005 prices of additional expenditure) as leverage to obtain the required improvements to the Phase 2 contract.

48. DMO informed the ANAO that DMO processes do not require a separate business case to be developed in these circumstances, but rather the decision was based on consideration by the relevant DMO decision-maker of a series of documents, the status of the project at the time and available options (albeit that this consideration was not documented at the time). The ANAO notes that the majority of these documents were developed after the decision had been taken to use Phase 3 as leverage to address contractual issues associated with Phase 2 and that none of them included consideration of any alternative options. Unlike the suite of documents provided to the ANAO by DMO, a business case, in these circumstances, would generally include consideration of the various options taking into account relevant issues to inform decisions on the most appropriate course of action.

49. The capacity to use the torpedoes acquired under Phase 3 is contingent on the platform integration program under Phase 2 being completed. The FRAA negotiation resulted in the removal of the integration of the torpedo with the air platforms from the contractual scope of work, but these remained within the scope of Phase 2 of the project until early 2008 for the Super Seasprite and early 2009 for the Orion and Seahawk. The DMO calculated that, by removing the air platforms from the scope of the contract, the contracted amount under Phase 2 reduced from $268.7 million to $179.6 million (December 2001 prices). At the time the FRAA was signed, $101.0 million had been expended on Phase 2. Phase 3 was for a fixed price of $239.2 million (December 2003 prices), escalated to $263.9 million (December 2005 prices). The ANAO sought evidence that these figures had been the subject of a cost investigation and was informed by the DMO in April 2010 that the prices in the FRAA were a negotiated price based on estimated scope of work, risk transfer and commercial basis for the contract. The DMO further advised that the lead negotiator considered these prices to be a fair price based on his involvement in the Alliance for a 12 month period.

Torpedo Delivery and Platform Integration (Chapter 4)

50. Both the Defence Procurement Review 2003 and the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review 2008 advocates the increased use of off-the-shelf solutions, where available, as a mechanism to reduce risk.40 The Defence White Paper 2009 confirmed that it was the Government's decision that Military-off-the-Shelf (MOTS) and Commercial-off-the-Shelf (COTS) solutions to Defence's capability requirements will be the benchmark going forward.

51. The 2008 Audit of the Defence Budget (also known as the Pappas Review) recommended that projects do not advance until they reach a required level of technical maturity. The Pappas Review identified JP 2070 as a project that was launched with unproven technology. This statement is inconsistent with the history of JP 2070. The Defence Source Selection Board (DSSB) in October 1999, which agreed to the sole sourcing of the Project Definition Study, noted that the MU90 was the only in-service weapon offered. The decision of the DSSB was based on the content of a Source Evaluation Report which stated that the MU90 was an off-the-shelf weapon and was entering service with other navies. The submission to the delegate seeking approval to sole-source the Project Definition Study used the term ‘in-service' with respect to the MU90. The ANAO notes that the terms ‘off-the-shelf', ‘in-service' and ‘entering service' are not identical in meaning.

52. The Source Evaluation Report was based on the report of three proposal evaluation working groups. Two of these reports used differing terminology with respect to the development status of the MU90, with one saying it was in-service while the other stated the torpedo was being purchased by other navies. In-service is significantly further down the development path than being purchased, as an item that is being purchased has not necessarily undergone Operational Test and Evaluation. The documentation provided by Defence to the ANAO to demonstrate how the decision makers at the time formed the view that the weapon was in-service with other navies did not say that the torpedo was in-service with other navies.

53. The Proposal and Liability Approval for the Project Definition Study indicated that $1.43 million had been allocated to funding an in-water trial of the torpedo as a risk mitigation measure. With the decision to develop an Alliance Agreement, this trial did not go ahead. It is not apparent how the Alliance Agreement removed the requirement to verify torpedo performance.

54. Notwithstanding the inconsistencies in the evaluation documentation for the Project Definition Study, the view that the torpedo was in-service and off-the-shelf was maintained by Defence and the DMO for several years. A 2000 Defence internal audit stated that the MU90 was a proven torpedo and a brief to the September 2002 Project Governance Board stated that the torpedo was fully developed and in-service with other navies. In January 2003, the then Minister was informed that the risk of Project failure was very low as the weapon was already in-service with other nations.

55. In March 2004, Defence were informed that the MU90 was not in-service with any other nation and that there had been technical and production issues. This was more than four years after the decision to sole-source the Project Definition Study and 15 months after the Revised Alliance Agreement for Phase 2 was signed. It is not clear how, under an alliance arrangement, the Defence personnel within the Alliance Management Team did not ascertain sooner that the torpedo was not in-service elsewhere.41

56. The June 2004 Business Due Diligence report indicated that the main areas of concern for JP 2070 were inter-project dependencies and made no reference to misunderstandings surrounding the development status of the torpedo, and how this might change the risk profile of JP 2070. A December 2004 brief to the Defence Committee indicated the MU90 torpedo was not off-the-shelf and had not been introduced into service elsewhere. In March 2005, some 12 months after Defence became aware the torpedo was not in-service elsewhere, the then Minister was informed that the torpedo was not in-service with European navies as previously advised.42 That brief indicated that there were issues with trials conducted by the torpedo manufacturer in 2004, but that Defence had been advised that these issues had been resolved and a test program had recommenced.

57. The FRAA was signed in August 2005, prior to any torpedoes having been delivered under Phase 2. At the time, Defence advised the Government that it had misunderstood the French and Italian acceptance processes and, contrary to previous advice, the torpedo had not been accepted by these services and remained subject to trials. This means that in addition to having achieved limited progress towards integrating the MU90 with the air platforms, there were ongoing and unresolved issues surrounding the torpedoes being acquired under Phase 2 at the time the DMO committed the Commonwealth to acquiring a much larger quantity of torpedoes under Phase 3. In April 2010, the DMO noted that before Defence committed to Phase 3 in August 2005 the then Government had been fully informed of the status of the torpedo and progress of integration work.

58. These French and Italian trials referred to in paragraph 57 were conducted under the Technical and Industrial Action Plan (TIAP), which was established by the French and Italian Governments following testing in 2004 that had demonstrated poor performance, which was attributed to industrial and quality issues with the production torpedo. The TIAP was to comprise three technical trials, followed by eight to 10 sea trials. The TIAP was planned to be completed by mid 2005, but by April 2006 the TIAP was regarded as having achieved mixed success.

59. The successful completion of the TIAP was a contractual requirement under the FRAA. In April 2006, the DMO issued a Notice of Default under the FRAA. The TIAP trial was subsequently suspended by the French and Italian Steering Group in May 2006, pending a technical investigation by the torpedo manufacturer. In light of this, the DMO subsequently rejected several claims for milestone payments and, in July 2006, the DMO wrote to the Alliance Participants suspending certain categories of milestone payments and asserting its rights to terminate and recover $75 million in payments if the TIAP did not achieve success in six months, subject to no alternative arrangements being agreed. In September 2006 the Alliance Board, which included a Commonwealth representative, agreed a resolution, subject to certain conditions, that the Commonwealth give consideration to extending completion of the TIAP until March 2007.

60. In December 2006, the DMO informed the Chief of Navy that the last TIAP firing had occurred in October 2006 and, following a result of eight successful firings out of 10, the French/Italian Steering Group had declared the program a success. In March 2007, the then Minister was informed that the TIAP had been declared a success but that further trials had identified a fault introduced by a design change. Subsequently, Defence's acceptance of the torpedoes under Phase 2 was completed in July 2007. This was more than two years behind the original schedule.

61. At the completion of the TIAP, an obsolescence review was conducted by the manufacturer that identified the need to modify the components of the torpedo. A new version of the torpedo, the MU90 Mark II, was developed to address the issues identified in the obsolescence review. The torpedoes being acquired under Phase 2 are the original Mark I version of the torpedo. The Mark II version was to be acquired under Phase 3. Australia was the first country to enter a contract to acquire the Mark II.

62. The modification of the torpedo to the Mark II configuration created the need to qualify the torpedo with six successful launches prior to conducting Early Proof of Capability launches using Australian manufactured torpedo components. The Early Proof of Capability was contractually required to be complete by November 2009 but, in March 2009, the Djimindi Alliance Board was informed that this schedule might not be achieved.

63. In July 2009, the DMO wrote to the Chief of Navy outlining four options for proceeding with deliveries under Phase 3. These options ranged from doing nothing, to modifying the Early Proof of Capability arrangements, or accepting a portion of the Phase 3 torpedoes in Mark I configuration and the remainder in Mark II configuration. The Chief of Navy agreed to an option which will see two-thirds of the Phase 3 torpedoes delivered in Mark I configuration, and the remainder in Mark II configuration. Defence identified that an advantage of this approach was that France and Italy would enter the Mark II program and thereby reduce the development risk to Australia.

64. In November 2009, the ANAO sought clarification on whether the issues continuing to impact on the Phase 2 timeline, particularly relating to test and evaluation, were considered in determining whether or not to agree to accept this change to delivery arrangements. The DMO responded, advising that ‘the associated Contract Change Proposal improves or maintains the schedule for Phase 3 as the National Security Committee confirmed the program as viable for surface integration.'

65. The Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review 2008 categorised projects based on complexity. JP 2070 exhibits two of the three attributes of a complex project set out in that review. These are: that JP 2070 involves multiple platforms; and it involves varying levels of system and software integration onto these platforms.

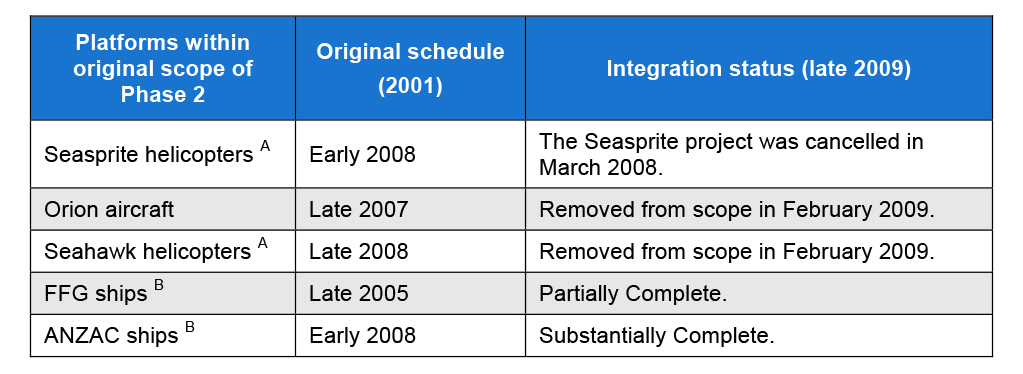

66. Table S 1 outlines the integration status of the five platforms originally in the scope of Phase 2.

Table S 1 Achievement of platform integration under Phase 2 of JP 2070 (as at November 2009)

Note A: The decision to cancel the Seasprite in March 2008 resulted in a decision to bring forward another project, Air 9000 Phase 8 Naval Combat Helicopters. The helicopter to be acquired under this project is to be capable of anti-submarine warfare and will also replace the Seahawk.

Note B: Operational test and evaluation activities need to be completed prior to operational release of the MU90 torpedo and associated platform modifications.

Source: Adapted from Defence documentation.

67. Cooperation between the various platform suppliers and the weapon supplier was seen as critical to the success of the Phase 1 Project Definition Study. Legal advice in 1999 indicated that an alliance approach was being considered to facilitate this cooperation. Based on this advice, a submission was prepared that sought support to adopt an alliance contracting approach. Subsequently, a series of sub-alliance agreements were signed between the Djimindi Alliance and the platform suppliers. The sub-alliance participants were to develop the integration solutions for the various platforms. A 2004 DMO Internal Review identified that responsibility for integration of the torpedo onto all platforms, apart from the FFG, had been transferred out of the Alliance to the respective DMO System Program Offices. In April 2010, the DMO informed the ANAO that the August 2005 FRAA formally removed work from the Alliance which was best managed by the DMO System Program Offices responsible for the platforms, and this included a price reduction to the FRAA.

68. The removal of responsibility for integration from the Alliance is an acknowledgement that the Alliance was not in a position to manage the risk associated with platform integration. It was not apparent to the ANAO that these risks were adequately understood at the commencement of Phase 2. A significant risk factor to JP 2070 from the outset was that many of the platforms to be integrated with the weapon were associated with other ongoing or yet-to-be-commenced projects which had the potential to impact on this project.

69. The ANAO identified four broad categories of risk for JP 2070 relating to platform integration. These included: risk related to integrating onto platforms that are also subject to a number of other upgrades; planning assumptions for JP 2070 being framed around unapproved projects; integrating to a platform while other projects relating to that platform are encountering difficulties; and seeking to develop an Australianised integration solution for the Orion and the Seahawk. Management of the first category of risk should occur as a fundamental component of the DMO's management of its program of procurement projects.

70. Risk for JP 2070 that related to planning assumptions being framed around unapproved projects primarily relates to the Seahawk and Orion Maritime Patrol Aircraft. For the Seahawk, the delays in the progression of planning for the Seahawk Midlife Upgrade and Life Extension (SMULE) impacted on JP 2070, although the delays to the Seahawk became increasingly linked to the integration solution being developed for the Orion.

71. Planning during 2004 and 2005 for the integration of the MU90 onto the Orion platform proceeded on the basis that the MU90 and the Follow-On Stand-Off Weapon (FOSOW) would be integrated through a single Stores Management Processor. The FOSOW was to be acquired under Project Air 5418 which was to be considered for Second Pass approval by the Government in December 2005. By that time $6.72 million had been spent on purchase orders relating to joint integration, with $1.92 million attributed to the torpedo project. A decision was subsequently taken not to integrate the FOSOW onto the Orion. Consequently, baseline information that had been developed on the basis of a joint integration of the MU90 with the FOSOW was then regarded as being of almost no value.

72. Risk related to integrating while other projects on the same platform encountered difficulties impacted on the integration of the torpedo onto the FFG, the Super Seasprite and the Seahawk. For the FFG, the integration of the MU90 has proceeded but has not been completed. This is primarily due to ongoing issues encountered under the FFG Upgrade Project associated with the Underwater Weapons System. The resolution of these issues has delayed the integration of Torpedo with the Sonar Operator Console. This interface needs to be in place to provide the desired level of integration being sought by the Navy. This interface was not in place at the conclusion of this audit.

73. The Super Seasprite Project encountered ongoing difficulty and was ultimately cancelled in 2008. However, the integration effort for this platform was limited as the Super Seasprite was regarded as being unsuited to an anti-submarine role, therefore it is not clear why the Super Seasprite was ever in the scope of JP 2070.

74. Delays in Project Sea 1405 Phase 1 and 2 Forward Looking Infrared and Electronic Support Measures impacted on the integration of the MU90 onto the Seahawk. In May 2007, the Chief of Navy wrote to the Chief of the Capability Development Group indicating that the integration of the MU90 onto the Seahawk was likely to be delayed until at least 2009, due to ongoing issues with Sea 1405, combined with structural issues associated with carrying the torpedo. The Chief of Navy commented that delays to JP 2070 were so great that the continuing integration onto the air platforms needed to be given consideration, as by the time the capability was to be realised, the platforms would be approaching their planned withdrawal date.

75. The risk related to developing an Australianised solution primarily relates to the efforts to integrate the MU90 onto the Orion and the Seahawk. Subsequent to the decision not to proceed with the integration of the torpedo onto the Orion in tandem with the FOSOW, an alternative integration approach needed to be developed. In March 2006, the Maritime Patrol System Program Office identified that no suitable Torpedo Control Unit (TCU) was available to achieve the desired level of integration between the weapon and the aircraft. Effectively, four years after the contract for Phase 2 had been executed, limited progress had been achieved towards integrating the torpedo onto the Orion and the Seahawk.

76. By 2007, a further $3.2 million had been spent on developing an integration solution for the Orion, against a work package which was not to exceed $2.8 million under the approved purchase order. The $3.2 million was sourced from the Project Budget for Joint Project 2070 which was managed by the DMO's Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Branch. Work was defined and payments were made by the Maritime Patrol System Program Office (SPO) which is responsible for the Orion. It became apparent that the arrangements did not provide adequate control over this expenditure, with purchase orders not being adequately detailed and work being undertaken that was regarded by Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Branch as beyond the scope of work of the purchase orders. In April 2007, the cost and schedule overruns related to the development of the TCU were attributed to: the failure of the Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project to deliver essential input documents and plans to schedule; and the need for the Orion Weapons Integration Integrated Project Team to expend significant unplanned effort and time workshopping essential interface documents for the torpedo systems that were represented as mature, but were in fact highly developmental. In April 2010, the DMO informed the ANAO that undertaking integration study work to de-risk technical activities is consistent with Defence standard practice particularly following the 2003 Defence Procurement Review.

Test and Evaluation (Chapter 5)

77. Test and evaluation is the means by which the DMO and Defence are assured that a materiel solution meets its required specification. Fundamental to test and evaluation is an appropriate hierarchy of capability definition documents including an Operational Concept Document, Functional Performance Specifications and a Test Concept Document. The absence, or late development of these documents, has impacted on the capacity to confirm capability achievement, and transition the torpedo and associated ship borne systems into Navy service.

78. A 2004 review of JP 2070 noted that key capability documents had either never been developed or not progressed beyond draft. Included amongst these documents was the Functional Performance Specifications.43 This review was conducted two years after the contract was signed for Phase 2. Subsequently, Defence's Functional Performance Specifications for the project were included in the contract as part of the 2005 FRAA negotiations. However, in the event of a conflict between the French specifications for the torpedo and Defence's Functional Performance Specifications included in the FRAA, the French specifications have precedent.

79. A 2009 draft Materiel Acquisition Agreement defined the project risks at that time. That draft agreement noted that the capability requirements for JP 2070 were defined through a Detailed Operational Requirements and not in a contemporary Operational Concept Document, and as a result JP 2070 did not have a clear concept of testing to meet requirements. The draft agreement stated that JP 2070 needed to define the torpedo capability based on poor quality capability requirement documentation and also indicated that significant unknowns existed that had the potential to cause schedule delays.

80. A key element of Acceptance Testing and Evaluation of a new capability is confirming contractual compliance. Acceptance Testing and Evaluation was ongoing for the Lightweight torpedo and the Ship borne Lightweight Torpedo System for the ANZAC and the FFG at the time of audit fieldwork. This testing was being conducted outside the provisions of the FRAA, as the initial batch of torpedoes procured and Ship borne Lightweight Torpedo System (both procured under Phase 2) had already been accepted by the DMO. In April 2010, Defence informed the ANAO that where work under a major project is conducted under several contractors the transition from Acceptance Test and Evaluation under those contracts to Operational Test and Evaluation rests with the DMO and Defence. Defence indicated that to do otherwise would attract expensive risk premiums.

81. In 2008, the Djimindi Alliance Board was informed that the Project Office was reviewing Critical Operational Issues (COIs)44 from the Detailed Operational Requirements to confirm that acceptance test and evaluation has been achieved. The Test Concept Document and the Operational Concept Document should list the required COIs for a capability. At the time the Board was informed of this activity, the Test Concept Document was not finalised and was not approved until some 12 months later.

82. The ANAO reviewed the compliance matrix attached to the report on the December 2009 sea trials of the MU90 conducted aboard an FFG. That matrix indicated compliance primarily against the Detailed Operational Requirements. The compliance assessment within that matrix indicated that compliance was yet to be verified against a large number of Detailed Operational Requirements with compliance having been fully verified against a small proportion of requirements. This means that eight years after the contract was signed for Phase 2, and two years after the initial batch of torpedoes procured under that Phase were accepted by the DMO, the DMO was yet to fully verify the capability acquired under Phase 2. In April 2010, Defence informed the ANAO that the conduct of trials were not only delayed by JP 2070 but also by the FFG Upgrade project.

83. Naval Operational Test and Evaluation45 commences following Initial Operation Release (IOR). IOR is the milestone where the Chief of Navy is satisfied that the operational and material state of the equipment is such that it is safe to proceed with Naval Operational Test and Evaluation. Operational release occurs at the conclusion of Naval Operational Test and Evaluation.

84. The Joint Test and Evaluation Master Plan for JP 2070 states that the Project Office will manage the conduct of a number of firings of Practice and Exercise Torpedoes to finalise acceptance testing prior to handing over the capability to the Royal Australian Navy Test Evaluation and Analysis Authority (RANTEAA) for Operational Test and Evaluation. At the time of this audit, one sea trial involving an ANZAC ship had been cancelled in 2005, one had occurred involving an ANZAC ship in 2008 and two had occurred in late 2009 involving an ANZAC ship and an FFG.

85. The trial in 2008 aboard the ANZAC ship involved six PDT firings and one TVE firing. The DMO report on the trial concluded that Acceptance Test and Evaluation COIs had been met, could be worked around, or were sufficiently well-advanced and, as such, a recommendation for proceeding to Operational Test Evaluation could be made. The COIs reported against in the DMO report on this trial were based on COIs set out in draft documentation. The COIs used for trials in 2009 were different to those used for trials in 2008.

86. Critical Technical Parameters (CTPs) are quantitative and qualitative test measurements of technical data that provide information on how well a system, when performing mission-essential tasks as specified in the Operational Concept Document, is designed and manufactured. Verification of CTPs is part of the IOR process. The Trial Plan for the FFG and ANZAC for the 2009 trials included an assessment of compliance against 12 CTPs. Of these compliance was indicated against five CTPs; partial compliance against one; not-yet compliant against two CTPs; and compliance was yet to be determined against two CTPs. With respect to the remaining two CTPs, one was assessed as non-compliant with work ongoing to achieve compliance, and a waiver has been granted against the other.

87. The report on the trial aboard the ANZAC ship in late 2009 indicated that three PDTs were successfully fired, after some issues with the Ship borne Lightweight Torpedo System were overcome. The planned TVE firing could not go ahead due to adverse weather conditions.

88. The report on the trial aboard the FFG in late 2009 indicated that three PDTs were successfully fired, after some issues with the Ship borne Lightweight Torpedo System were overcome. The first TVE was ejected from the torpedo tube, but failed to start. A second TVE was fired, and started successfully. Investigation of the issue surrounding the firing of the first TVE was ongoing in February 2010 and there were also concerns surrounding the torpedo endurance demonstrated by the second firing, which was also subject to investigation.

89. The DMO prepared a ministerial submission on these trials and sought input from Navy on this submission. Navy expressed concern about the content of this submission, particularly the suggestion in that submission that the trials were key to Navy accepting the MU90 system. It is apparent that the DMO needs to review its approach to test and evaluation, in consultation with the Navy, to ensure that future trials are conducted in a manner that progresses the capability towards IOR.

90. The Joint Test and Evaluation Master Plan developed in August 2002 planned for acceptance into service of the ANZAC Ships Lightweight Torpedo System in the last quarter of 2007, and the FFG Ships Lightweight Torpedo System was to be accepted into service in second the quarter of 2008. By May 2006 a timeline for IOR, and as such acceptance into service, had not been defined. This was partially attributed to delays in torpedo deliveries. In July 2008, the DMO wrote to the then Minister indicating that additional funding was required to support Test and Evaluation. In 2008, the DMO sought approval to access funding previously allocated to air integration to fund this activity. The Test Concept Document had not been finalised at that time, indicating that agreement between the project stakeholders in Defence on the testing required had not yet been achieved.

91. The Form TI338 is the formal document used in Navy to facilitate IOR and eventually Operational Release of new capability. At the conclusion of this audit, the Form TI338 for the MU90 remained in draft form. Prior to making a recommendation to the Chief of Navy for Initial Operational Release, a number of Navy regulators need to endorse the Form TI338. The draft form TI338 showed that two key documents required for certification were yet to be finalised. These were an Agreed Certification Basis and a Safety Case Report.

92. The draft Form TI338 identified three issues which directly impact on the ability to complete Operational Test and Evaluation. These included the lack of a suitable target for testing, the lead time to buy a simulation model, and difficulties with access to Objective Quality Evidence (OQE)46 to verify prior qualification. All these issues had been identified previously in a 2004 brief to the Director-General, Maritime Development in Capability Development Group of Defence. The brief recommended that ‘consideration be given to delaying committing to Phase 3 as a mechanism to obtain information [relating to the Italian and French navies' testing and evaluation of the MU90] for IOR'. Notwithstanding this recommendation, the agreement for Phase 3 was signed in August 2005 before the issues surrounding OQE required to support transition to IOR had been resolved.

93. A key benefit of receiving this OQE information from the French and Italian testing and evaluation processes would be that it could reduce the number of times that the ADF needs to fire the torpedo to generate operational performance information for the weapon. An April 2004 briefing to the Project Management Stakeholder Group advised that the weapon is inordinately expensive to fire. A 2007 brief indicated that the cost to turn around an exercise torpedo firing was approximately $330 000. Additionally, each torpedo can only be fired in TVE configuration on three occasions before being permanently consigned to war stock.

94. Modelling and simulation permits the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) to conduct analysis of weapon performance for Operational Test and Evaluation and tactical development. It was identified very early in JP 2070 that a modelling and simulation tool would be required, and since that time a number of options have been considered with limited progress towards the acquisition of a modelling and simulation tool. The draft 2009 Materiel Acquisition Agreement identified that obtaining a simulation model and analysing MU90 performance was critical to achieving capability assessment. In February 2010, Defence informed the ANAO that a Statement of Work had been prepared for a modelling and simulation tool which was scheduled for release for quotation in the second quarter of 2010.

95. Similarly, the requirement for a suitable simulated submarine target was identified very early on in the project, was considered on a number of occasions, and there was very little progress toward the required acquisition of that target for a significant period. There are a variety of simulated submarine targets available, ranging from static or towed targets to high-fidelity autonomous targets. The sea trials of the TVEs from ADF platforms in 2008 and 2009 used a static or towed target, which was regraded by Navy as not being a representative target capable of testing the attack criteria.

96. In 2009, Defence sought approval from the Government to access funds previously allocated in the JP 2070 budget to air platform integration for the acquisition of a mobile target. In February 2010, Defence informed the ANAO that funding of $9.4 million had been approved for this acquisition and it was scheduled for completion in early 2012. The ANAO notes that this was inconsistent with a briefing prepared by the DMO for a meeting in early 2010 that indicated that ‘the target procurement had not progressed.' In April 2010, DMO acknowledged that progress to acquire the mobile target is behind schedule. Defence advised that discussions have been held with stakeholders to recover schedule, which will involve the commercial lease of a target in early 2011, while the acquisition of a target will proceed in accordance with the February 2009 Government approval.

97. Adequate access to sufficient OQE represents a significant issue for testing and evaluation. The September 2009 draft Test and Evaluation Master Plan noted that there were a range of impediments to obtaining OQE and the results of Operational Test and Evaluation conducted by the French and Italian Navies. These impediments included the fact that the French and Italian Governments contracted the development of the MU90, and therefore the torpedo manufacturer did not have the right to release test data and OQE. Additionally, French and Italian Government agencies which undertook Operational Test and Evaluation used targets and countermeasures which were classified under their respective national security guidelines, making access to this information problematic.

98. The draft Test and Evaluation Master Plan attributes Defence's belief at the outset of JP 2070 that the MU90 torpedo was off-the-shelf as a contributing factor to OQE not being sought from the torpedo manufacturer from the outset of JP 2070. However, by the time the FRAA was signed, committing the Commonwealth to Phase 3, Defence had been aware for more than 12 months that the torpedo was not an off-the-shelf acquisition.47 The ANAO also notes that the need to access to OQE and technical information was identified in 2000 even though at that time, and for the following four years, Defence and the DMO believed the torpedo to be off-the-shelf.

99. Over the life of JP 2070, a series of correspondence has been exchanged, and agreements have been entered into, with the French and Italian Governments to facilitate the transfer of required data and OQE.48 In late 2009, the ADF Test and Evaluation Authority acknowledged that the most significant weakness in the draft Test and Evaluation Master Plan for JP 2070 relates to the inability to access foreign OQE. In February 2010, DMO informed the Project Management Stakeholder Group that some progress had been made in reaching an agreement to access data, but if this data was not forthcoming, a major testing and evaluation campaign would need to be undertaken. In March 2010, the DMO informed the ANAO that additional OQE from the TIAP program had recently been provided but that this needed to be translated and then analysed by Defence. In April 2010, Defence informed the ANAO that there had been progress on the OQE issue since audit fieldwork concluded with data provided in March 2010 and technical workshops planned to occur in France in May 2010 to work through data requirements.

Financial Management (Chapter 6)

100. As at February 2010, the budget for Phase 2 had increased from$287.71 million (December 2001 prices) to $346.71 million (January 2010 prices), as result of price and exchange rate movements, of which $219.43 million had been expended. The budget for Phase 3 had increased from $246.43 million (January 2004 prices) to $313.81 million (January 2010 prices), as result of price and exchange rate movements, of which $173.13 million had been expended. Expenditure during 2006 07 for Phases 2 and 3 was significantly less than forecast expenditure due to delays associated with the finalisation of the TIAP. There have been no real cost increases within the budget for any of the approved phases of JP 2070, however the scope of Phase 2 has been significantly reduced without commensurate reductions to the approved budget.

101. Defence's Annual Report includes a section on Defence's Top 30 Projects. In the 2008 09 Defence Annual Report Phase 3 was included in the list of Top 30 Projects, whereas Phase 2, which has a higher overall budget, did not appear in that list. This was on the basis that projects are included in the list based on forecasted expenditure. A comparison of actual expenditure under Phase 2 during 2008 09 revealed that Phase 2 had a higher level of actual expenditure than other projects included in the Top 30 Projects list.

102. Up until 2005, there was uncertainty surrounding the appropriate mechanisms to make payments under the alliance arrangement for JP 2070. Initially payment arrangements under Phase 2 involved three monthly prepayments to the Alliance for disbursement to Alliance Participants, Sub-Alliance Partners and sub-contractors. Concern was expressed in mid-2003 about the advance payment arrangements. At that time the banking arrangements were also subject to review, as the Project Governance Board had been informed that there were no means for the DMO to make payments to Djimindi Alliance for onward disbursement.

103. In November 2003, the DMO entered into an agreement with Thales Underwater Systems to take over from the Commonwealth in providing banking, associated cash management activities and purchasing for work performed by the Alliance Participants under the Alliance Agreement. This was implemented by issuing a purchasing card to the Djimindi Alliance and establishing two interest-bearing Trust Bank Accounts, one in Australian Dollars and the other in Euros. Under this agreement, the Commonwealth was required to make an initial payment into the Trust Accounts and then make subsequent payments upon request from the Djimindi Alliance Business and Finance Manager. In September 2004, DMO received advice that the Trust Account arrangements breached provisions of the Financial Management Accountability Act 1997.49

104. Two years after the agreement establishing the Trust Account was executed, the DMO negotiated new payment arrangements that were implemented under the August 2005 FRAA. These arrangements removed the requirement for the Alliance Trust Account. In October 2005, the Djimindi Alliance Board resolved to terminate the November 2003 Project Djimindi Alliance Trust Bank Account and Purchasing Card Agreement; transfer the residual Trust Account balances to an account to be nominated by the Industrial Participants, with residual balances to be offset from upcoming milestones. The purchasing card was also to be cancelled. The DMO informed the ANAO that at the point the Trust Account was closed, in May 2006, $1.65 million was refunded to the JP 2070 Project Office.

105. The November 2002 Proposal and Liability Approval for Phase 2 indicated that the contingency budget for that phase was $10 million. Of this figure, $7.5 million was transferred to the Alliance to manage, $500 000 was allocated to testing and $400 000 was allocated to the integration of the torpedo onto the ANZAC ship. At the July 2005 Project Management Stakeholders Group Meeting it was noted that in a software-intensive project ‘a contingency of $1.6 million is woefully inadequate'. That meeting was informed that further contingency was held in the budget figures for platform components. However, 11 months earlier the DMO's Head of Electronic Systems wrote to the Head of Capability Systems advising of a likely shortfall in funding arising from an underestimate of the aircraft integration costs.

106. The minutes of an August 2004 meeting of the Weapons Project Governance Board questioned how JP 2070 obtained Government approval without cost estimates. The JP 2070 Project Office advised that it had obtained ballpark figures, which had since been found to be completely inaccurate. The Project Office indicated that integration of this type of system onto an aircraft could cost between $50 to $100 million, but that the approved budget was $35 million for the Orion, and $30 million for each helicopter. In March 2005, the then Minister was informed that the budget for JP 2070 might not be adequate for the required level of integration across all platforms.

107. The August 2005 FRAA negotiation report indicated that JP 2070 was also under cost pressure because Net Personnel Operating Costs50 were not included in JP 2070 budget approvals. These were estimated to be $3.3 million a year out to 2021, bringing the whole-of-life capability cost for the MU90 to an estimated $1.13 billion. That report also stated that significant additional resources would be required, as under the FRAA the Project Office was to undertake work that was previously the responsibility of the Project Djimindi Alliance. In March 2010, DMO advised the ANAO additional resources were allocated to the Project Office including through the hire of professional service providers.

108. In October 2005, a minute to the Chief of the Capability Development Group indicated that there was very little contingency left in the Phase 2 budget and that a real cost increase might be required. This minute was drafted two months after the FRAA was signed, committing the Commonwealth to significant Phase 3 expenditure. As noted above, the shortfall in the Phase 2 budget had been identified at least 12 months prior to the FRAA being signed in August 2005.

109. The November 2005 Project Management Stakeholders Meeting was informed that the then Minister had directed that the platform project budgets not be varied. This resulted in the quarantining of $111 million of the Phase 2 budget, thereby preventing the budget for integration of the torpedo onto one platform being reallocated to a different platform without ministerial agreement. In May 2006, the CEO of DMO wrote to senior Defence Personnel indicating that Phase 2 of JP 2070 was listed as a Project of Concern. The primary reason for this related to issues with MU90 torpedo performance; delayed integration to aerospace platforms and an increasing understanding that the budget was insufficient to cover the approved scope.