Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

jobactive: Design and Monitoring

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess whether the Department of Employment effectively designed and monitors the progress of the jobactive program.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The current federal employment services program, jobactive, became operational on 1 July 2015, and replaced the previous employment services model, Job Services Australia. The objectives of jobactive are: helping job-seekers find and keep a job; helping job-seekers move from welfare to work; helping job-seekers meet their mutual obligations; and jobactive organisations delivering quality services.

2. The Department of Employment (Employment, or the department) administers jobactive and there are approximately 750 000 job-seekers at any given time in the program. Employment is forecast to spend approximately $7.3 billion over the contracted five year period of jobactive. The delivery of employment services is contracted to 65 providers who deliver one or more of the five services of the program: jobactive employment services; New Enterprise Incentive Scheme; Work for the Dole Coordinators; Harvest Labour Services; and the National Harvest Labour Information Service.1

3. Employment oversees the delivery of the contracted services, and has established compliance and performance monitoring arrangements to provide assurance that the services are delivered as expected.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess whether Employment effectively designed and monitors the progress of the jobactive program. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the jobactive program was designed to support the achievement of the Government’s policy objectives; and

- the department effectively monitors the progress of the jobactive program against the Government’s policy objectives.

Conclusion

5. Employment effectively managed the design of jobactive and its monitoring approach has resulted in a reasonable level of assurance being obtained that the program is being delivered as required.

6. There was a sound reason for redesigning the employment services model, the governance arrangements established by the department were comprehensive, stakeholders were adequately consulted and the Minister was briefed on a range of design and implementation topics. Since the implementation of jobactive on 1 July 2015, the department has reviewed and amended elements of the program’s design.

7. Employment has established a suitable committee structure to oversee the jobactive program and the department has identified and managed risks at the program and provider level. The prioritisation of activities to deliver the program could be improved to ensure that required activities are completed. The principles-based guidelines do not always clearly articulate Employment’s expectations of providers.

8. Employment has obtained a reasonable level of assurance that the jobactive program is being administered as designed and expected. The Assurance Strategy for the jobactive 2015–2020 contract includes new program assurance elements that have strengthened the department’s monitoring of employment service provider’s compliance with contractual obligations. While the department is currently reviewing the operation of the Assurance Strategy, the review does not address some of the key elements of the program, including whether the strategy reflects the department’s preferred level of compliance.

9. The performance frameworks for the five jobactive services measure the performance of providers. The Key Performance Indicators developed by the department, which align with program objectives, have been developed for three of the five services, but performance targets have only been established for one of the services. Employment has an evaluation strategy for jobactive, but it does not address some aspects of the program, including contract management and the Star Ratings.

Supporting findings

Program design

10. Employment identified significant weaknesses in the former Job Services Australia model, which was the key reason for developing the new employment services program, jobactive. These weaknesses were appropriately considered when designing the jobactive program. The governance arrangements established by the department for the design and implementation of the jobactive program were comprehensive, with strong senior executive engagement and support from the 16 working groups that had responsibility for developing the policy of specific subject areas.

11. During the design of jobactive, stakeholders were consulted and Employment considered their views when designing the program. Employment provided sound advice to the Minister for Employment and the Assistant Minister for Employment on a range of design considerations and associated risks.

12. In consultation with providers and peak bodies, Employment has made several changes to the design of the jobactive program. The department established working groups or external reviews to guide improvements to the program.

Governance arrangements for ongoing management

13. Employment has established an appropriate governance structure to provide oversight and make decisions about the ongoing management of jobactive. Improved prioritisation of the activities necessary for effective delivery of the jobactive program is needed to ensure that objectives are being achieved.

14. Employment has established an appropriate framework to manage risks to the jobactive program. While the management of high-level program risks has been generally sound, there is scope for the department to improve the timeliness of monitoring and mitigation actions for identified provider risks. Further, the department should make greater use of compliance and performance data to identify and manage provider risks.

15. Employment has established a principles-based approach for the jobactive guidelines to allow providers to deliver flexible solutions tailored to an individual job-seeker’s circumstances. On occasion, this has led to some inconsistency in the interpretation and application of the guidelines.

Program assurance of providers

16. Employment has established a comprehensive framework to manage provider compliance that incorporates approaches to prevent, deter, detect and correct non-compliance. Employment has a framework to monitor employment service providers’ compliance with contractual obligations. The framework enables the department to obtain a reasonable level of assurance about employment service providers’ compliance. There is scope to improve the analysis of complaints data, the provision of Rolling Random Sample results to providers in a timely manner, and the effective prioritisation of targeted assurance activities.

17. Employment manages non-compliance through the Remedial Action Framework. As at November 2016, six incidents of non-compliance had been investigated under the framework. The department has not analysed the reasons for the low number of recorded non-compliance cases.

18. Employment has not assessed the effectiveness of the Assurance Strategy, but has commenced a review to identify best practice and focus resources on areas of highest priority.

Performance measurement, reporting and evaluation

19. Employment has performance frameworks in place for the five services which measure the performance of providers. Key Performance Indicators for employment service providers, New Enterprise Incentive Scheme providers and Work for the Dole Coordinators align to the objectives of the jobactive program, but performance targets have only been set for Coordinators.

20. The Star Ratings were designed to be used by job-seekers and employers to inform their choice of employment service provider, and by Employment for business reallocation. The department does not have a strategy in place to assess whether the Star Ratings are used by job-seekers or employers to influence their choice of employment service provider. The department has used the Star Ratings for the first round of business reallocations.

21. Employment monitors progress against the targets in the Portfolio Budget Statement and Corporate Plan through performance reporting to the relevant governance committee. The department publicly reported on progress against the targets in its 2015–16 Annual Report.

22. Employment has developed an evaluation strategy for two of the five services of the jobactive program, including jobactive employment services, which adopts a staged approach to evaluation. The strategy does not cover three of the services or other key elements of the jobactive program, such as contract management and the Star Ratings.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.10

The Department of Employment should implement a risk-based approach to prioritising the activities required to effectively manage and monitor the delivery of the jobactive program.

Department of Employment’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 4.44

The Department of Employment should assess whether the current compliance regime is structured to effectively and efficiently detect and manage non-compliance, and adjust as appropriate.

Department of Employment’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

23. The summary response from Employment is provided below, with the full response included in Appendix 1.

The department welcomes the audit’s conclusions and the overall positive findings. The department is particularly encouraged by the ANAO’s recognition that the jobactive program design was effectively managed, with appropriate stakeholder consultation. I appreciate the audit’s acknowledgment of the department’s sound reasoning for the redesign of employment services, and the establishment of comprehensive governance arrangements. In addition, I welcome the ANAO’s conclusion the department has obtained a reasonable level of assurance that the jobactive program is being administered as designed and expected.

In terms of areas of potential improvement, particularly with regard to our approach to the prioritisation of program management activities and the current compliance regime, the department is taking steps to consider and address these issues. This includes our current Assurance Review and through ongoing monitoring of the Delivery and Engagement Group calendar and protocol.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Government has outsourced national employment services to employment service providers since 1998.2 The current federal employment services program, jobactive, became operational on 1 July 2015. The objectives of the jobactive program are: helping job-seekers find and keep a job; helping job-seekers move from welfare to work; helping job-seekers meet their mutual obligations3; and jobactive organisations delivering quality services.

1.2 Participation in jobactive is compulsory for those job-seekers who receive income support payments, such as the Newstart Allowance or Disability Support Pension, and have been identified by the Department of Human Services as being able to actively look for work.4 Individuals not receiving an income support payment, or those in receipt of income support without compulsory requirements may volunteer for one period of jobactive services for up to six months.5 The jobactive program is administered by the Department of Employment (Employment or the department).

Changing the employment services model

1.3 The jobactive model replaced Job Services Australia, which operated from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2015. The development of jobactive commenced in December 2012, with the contracts awarded in March 2015. A timeline of the development and implementation of the program is provided in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Timeline for the development of jobactive

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

1.4 The key differences between the employment services model of Job Services Australia and jobactive are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Key differences between the Job Services Australia and jobactive models

|

|

Job Services Australia |

jobactive |

|

Objectives |

|

|

|

Contract length (years) |

3 |

5 |

|

Number of job-seeker classification streams |

4 |

3 |

|

Payment model (administration fees to outcome payments) |

67:33 |

48:52 |

|

Administration fees paid every: |

13 weeks |

6 months |

|

Outcomes payments at (weeks): |

0, 13 and 26 |

4,12 and 26 |

|

Number of employment regions |

110 |

51 |

|

Number of employment service providers |

81 |

44 |

|

Total number of providersa |

116 |

65 |

Note a: Contracted providers in the jobactive program include employment service providers (who deliver employment assistance to job-seekers), Work for the Dole Coordinators, New Enterprise Incentive Scheme providers, Harvest Labour Service providers and the provider of the National Harvest Labour Information Service.

Source: ANAO from departmental documentation.

1.5 Employment reported that the changes made to the employment services program have been designed to:

- ensure that job-seekers better meet the needs of employers;

- increase job-seeker engagement by introducing stronger mutual obligation requirements;

- increase job outcomes for unemployed Australians; and

- reduce prescription and red tape for service providers.6

The jobactive program

1.6 The jobactive program is delivered in 51 employment regions across Australia, as shown in Figure 1.2. Job-seekers who are eligible for employment assistance, but live outside of these employment regions, are to be serviced by the Community Development Programme (which is administered by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet).

Figure 1.2: The employment regions for the jobactive program

Note: Norfolk Island is not pictured, but as of 1 July 2016 was included in the North Coast employment region.

Source: Employment.

1.7 The jobactive program consists of five services, outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: The five services of the jobactive program

|

jobactive employment services – forecast average annual expenditure of $1.31 billiona |

|

Delivered by 44 employment service providers to provide practical support to job-seekers to assist them in preparing for, securing and sustaining employment. Providers are required to maintain high levels of job-seeker and employer engagement, and facilitate and monitor Work for the Dole activities. |

|

New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS) – forecast average annual expenditure of $115 million |

|

A range of services to assist eligible job-seekers to establish and run their own small businesses, up to 7642 businesses were supported in 2016–17. The 21 NEIS providers deliver a range of services including, accredited small business training, business mentoring and advice for up to 52 weeks. |

|

Work for the Dole Coordinators – forecast average annual expenditure of $34 million |

|

Nineteen Coordinators, one per employment region, source suitable Work for the Dole places for job-seekers. Coordinators are responsible for sourcing places, liaising with hosts to secure places and connecting hosts with employment service providers.b Coordinators are not responsible for managing the Work for the Dole activity or job-seekers while they are in the activity; that is the role of employment service providers. |

|

Harvest Labour Services (HLS) – forecast average annual expenditure of $3.39 million |

|

Five HLS providers help supply supplementary out of area workers to agricultural growers in 11 harvest areas (these do not align to the employment regions). The HLS is the only jobactive service for which providers are paid to place people who are not job-seekers on income support into employment (in April 2016, 92.9 per cent of placements were for people not receiving income support). |

|

National Harvest Labour Information Service (NHLIS) – forecast average annual expenditure of $1.24 million |

|

One provider coordinates and disseminates information regarding harvest related work, including areas not serviced by the HLS, via an electronic National Harvest Guide and a national telephone information service. |

Note a: Department’s forecast funding for all five services for 2016–17, as at 31 December 2016.

Note b: Work for the Dole Coordinators started on 1 May 2015 to source places prior to the commencement of jobactive on 1 July 2015. In April 2017, the Government agreed to terminate Work for the Dole Coordinator contracts by 1 January 2018. Instead, employment service providers will source Work for the Dole placements and liaise with host organisations.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

1.8 Throughout this report, the term ‘provider’ refers to the 65 contracted providers in the five services of the jobactive program and the term ‘employment service provider’ refers to the 44 providers delivering jobactive employment services.

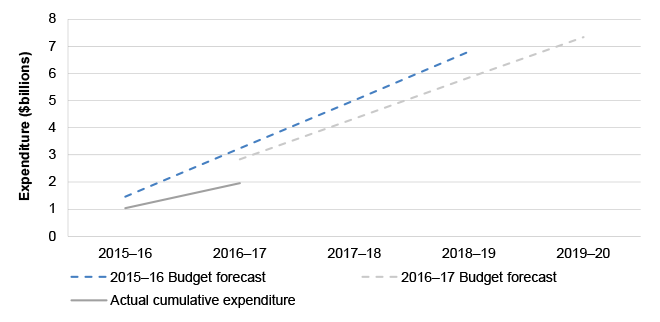

1.9 Employment is forecast to spend approximately $7.3 billion over the contracted five year period of the jobactive program. In 2015–16, expenditure was $1.02 billion, which was $157.8 million (13 per cent) below the total budget of $1.18 billion (as shown in Figure 1.3). The underspend was due, in part, to lower than expected outcome payments ($63.6 million lower than forecast) and Work for the Dole expenditure ($47.5 million lower than forecast). This resulted in a decreased budget forecast in 2016–17.

Figure 1.3: The jobactive program budgeted vs. actual expenditure, as at 31 March 2017

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation and Budget papers.

Delivery of employment services

1.10 One of the objectives of jobactive is to ‘promote stronger workforce participation by people of working age and help more job-seekers move from welfare to work’.

1.11 Under the program, assistance is provided to job-seekers by an employment service provider through one of three streams (Stream A, B, or C).7 Stream A job-seekers (including volunteers) account for 43.8 per cent of the overall caseload and are considered to be the most competitive and ready for work. Those job-seekers in Stream B (38.8 per cent) have some assessed barriers that will need their employment service provider to play a greater role to become job ready, such as language barriers. The most disadvantaged job-seekers, those with multiple barriers to work such as drug and alcohol addiction, are assisted through Stream C (17.1 per cent).

1.12 Employment has sought to incentivise employment service providers to deliver high quality services and achieve sustained employment outcomes for job-seekers who need the most support to find and keep a job. The employment service providers receive higher outcome payments, at four, 12 and 26 weeks for the successful transition of regional long-term unemployed Stream C job-seekers off income support.8

Audit approach

1.13 The audit objective was to assess whether the Department of Employment effectively designed and monitors the progress of the jobactive program.

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the jobactive program was designed to support the achievement of the Government’s policy objectives; and

- the department effectively monitors the progress of the jobactive program against the Government’s policy objectives.

1.15 The audit examined all five services of the jobactive program, but primarily focused on the jobactive employment services. The audit did not assess the department’s tender process conducted in 2014–15; review in-depth the transition process for implementing the jobactive program; or analyse the Department of Human Services’ payment of welfare benefits to job-seekers.

1.16 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO analysed departmental records and data, and interviewed key managers and personnel in Employment’s National and State Offices. The ANAO invited the three peak bodies and 65 providers to contribute to the audit. Two peak bodies and 23 of the 65 providers (35.4 per cent) provided a contribution, this included:

- 16 of the 44 jobactive employment service providers (36.4 per cent);

- eight of the 19 Work for the Dole Coordinators (42.1 per cent);

- seven of the 21 New Enterprise Incentive Scheme providers (33.3 per cent); and

- three of the five Harvest Labour Service providers (60 per cent).

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $423 000.

1.18 The team members for this audit were Meegan Reinhard, Anne Kent, Veronica Clement-Jones and Deborah Jackson.

2. Program design

Areas examined

This chapter examines the reason for establishing the jobactive program, and the arrangements that the Department of Employment (Employment or the department) introduced to manage the design process, including: governance and oversight arrangements; stakeholder consultations; advice to government; and refinements to the program’s design over time.

Conclusion

The department effectively managed the design process for jobactive. There was a sound reason for redesigning the employment services model, the governance arrangements established by the department were comprehensive, stakeholders were adequately consulted and the Minister was briefed on a range of design and implementation topics. Since the implementation of jobactive on 1 July 2015, the department has reviewed and amended elements of the program’s design.

Was there a clear reason for establishing jobactive?

Employment identified significant weaknesses in the former Job Services Australia model, which was the key reason for developing the new employment services program, jobactive. These weaknesses were appropriately considered when designing the jobactive program.

2.1 In June 2014, the government agreed that a reform of employment services was needed to address the identified weaknesses of the Job Services Australia model, and to introduce the new Government’s election commitments. The weaknesses were identified through a series of discussion papers and consultation, which are summarised below.

2.2 In June 2011, the Minister for Employment Participation established an Advisory Panel on Employment Services Administration and Accountability (the Advisory Panel) to provide advice to Employment on future employment service programs, opportunities for streamlining administration and industry-supported solutions to reduce unnecessary administration. The Advisory Panel’s final report, which was released in September 2012, made 13 recommendations.9 The government’s response to the final report noted that:

The Advisory Panel found that, against the backdrop of high public expectations of fraud prevention and value for money, the employment services model is complex in design and administration, and that there was a level of ‘hyper specificity’ in administrative requirements, a risk-adverse culture and a practice of risk mitigation in order to meet those expectations.10

2.3 In December 2012, the Minister released a discussion paper, Employment Services—Building on success, to seek public feedback on areas of the employment services model that could be improved. The resulting feedback highlighted weaknesses in the system, including that: training should be linked to a job or placement, not just for its own sake; too many job-seekers with a disability were being placed into Job Services Australia and not Disability Employment Services; post placement support was often poor; and there were thousands of youth under 21 years of age who were not engaged in work or education that needed to be connected to government services.

2.4 In June 2013, the Government agreed that broad consultation with the community and stakeholders would be conducted in order to develop a new employment services model to operate from mid-2015. The following opportunities for improvement had been identified through various consultative forums (discussed further in paragraphs 2.12 and 2.13):

- improving collaboration between employment service providers and other services (for example, housing and migrant services) would better leverage government investment in other social services to address non-vocational barriers to employment;

- better collaboration between providers would improve the sharing of best practice;

- increasing the awareness and use of employment services by employers of all sizes;

- initial assessment processes that better identify job-seeker needs and vocational and non-vocational barriers;

- addressing issues of training investment, which was poorly linked to local labour markets;

- the need for better tailoring of services to job opportunities and job-seeker needs; and

- addressing the concern that providers were investing significant, unnecessary resources in system compliance and reporting. It was noted that while transparency and accountability must not be compromised, the reduction in red tape needed to continue building on work underway to respond to the 2012 Advisory Panel’s report.

2.5 In September 2013, prior to the Federal Election, the Coalition released its Policy to Increase Employment Participation and Policy to Create Jobs by Boosting Productivity which included the following election commitments:

- a renewed commitment to reinvigorating the Work for the Dole program, so that unemployed people on income support are active, engaging in mutual obligation work activities and building skills to ensure they are work ready;

- introducing payments to long-term unemployed job-seekers who find and retain employment (the ‘job commitment bonus’) or who are willing to relocate for employment; and

- reducing the regulatory burden for individuals, businesses and community organisations by establishing and meeting a red and green tape reduction target of at least $1 billion a year.

2.6 Employment conducted two evaluations of Job Services Australia—in October 2014 (for the first contract from 2009–12) and July 2016 (for the second contract from 2012–15). The evaluations aligned to the findings of the earlier consultations and research (as discussed above). The evaluations found that:

- the two contracts achieved higher education outcomes than the preceding Job Network contract, but progressively lower employment outcomes; and

- the estimate of red tape expenditure declined by nearly 20 per cent between the two contracts (from $321.9 million to $259.3 million per annum), but this was still significant and equated to 20.9 per cent of program funding and was largely borne by providers (84.5 per cent).

Was an appropriate governance framework established for the design and implementation of jobactive?

The governance arrangements established by the department for the design and implementation of the jobactive program were comprehensive, with strong senior executive engagement and support from the 16 working groups that had responsibility for developing the policy of specific subject areas.

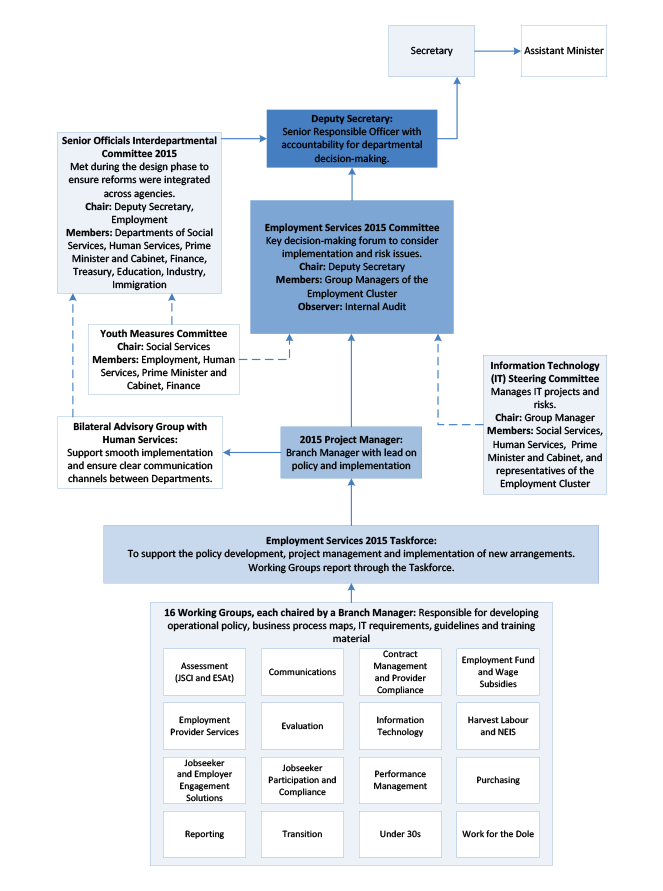

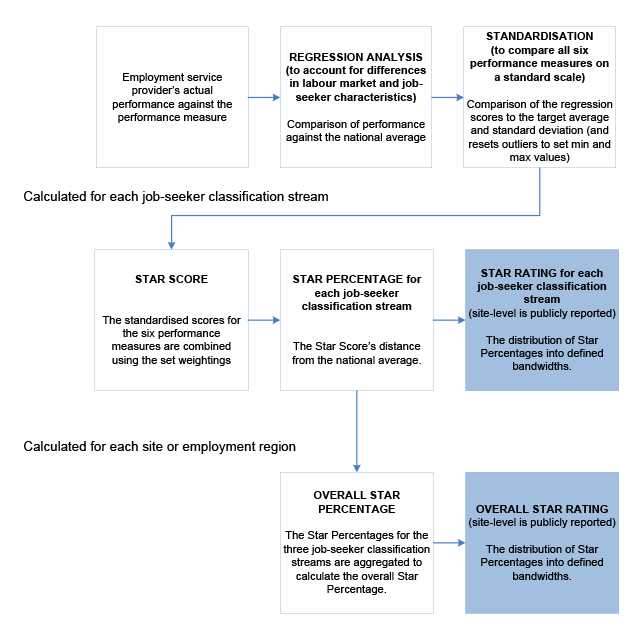

2.7 The governance arrangements that Employment implemented for jobactive (at the time of design, the program was referred to as the Employment Services 2015 program) are shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Governance arrangements for the design of jobactive

Note: The arrows represent reporting arrangements.

Source: ANAO representation of departmental documentation.

2.8 The Employment Services 2015 (ES2015) Committee was the governing body responsible for providing strategic direction on the development and implementation of the 2015 Employment Services program. The ES2015 Committee was established as the central departmental decision-making body on policy development, and all aspects of implementation including project planning, risk management, issues management and overseeing stakeholder management.

2.9 The ES2015 Committee met regularly and received updates and made timely decisions on the topics raised (covering both policy development and implementation concerns), as recorded in its Decision Register and Action Items Register. The ES2015 Committee implemented the jobactive program on 1 July 2015. The ES2015 Committee effectively managed the oversight and design of the jobactive program. The ES2015 Committee was dissolved in October 2015 three months after the implementation of jobactive.

2.10 Sixteen working groups, each led by a Branch Manager, were established by the ES2015 Committee to support the implementation of the jobactive program through the development of specific policy and service delivery arrangements. Each of the working groups was responsible for developing and regularly reporting on project management plans, which included key tasks, risk plans, stakeholder identification, change management strategies, business process mapping and IT requirements.

2.11 The ANAO’s analysis of the closing reports for the 16 working groups found that the reports listed achievements against key deliverables and milestones, outstanding deliverables and/or ongoing functions that will be transferred to identified branches, outstanding risks and lessons learnt. The working groups achieved the majority of key deliverables. There were some minor policy decisions that remained unresolved at the time of closure (for example, the number of business days allowed to commence a job-seeker in an activity during the Work for the Dole phase) and some deliverables required technical solutions so they could be implemented (for example, errors with the job-seeker appointment booking system). There were several recurring lessons learnt across the various working groups, including: membership of the working groups and ownership of the issues; allowing appropriate lead times for internal clearances and testing; and the challenges of developing processes when the policy was not settled. Employment has assigned responsibility for building on the lessons learnt to the Employment Steering Committee (discussed in Chapter 3).

Were relevant stakeholders adequately consulted on the design of the jobactive program?

During the design of jobactive, stakeholders were consulted and Employment considered their views when designing the program.

2.12 During the initial design of the revised employment services program, there were multiple opportunities for stakeholders to provide feedback on the model, including:

- Advisory Panel on Employment Services Administration and Accountability (the ‘Advisory Panel’)—in late 2011 the Advisory Panel consulted with representatives from large and small Job Services Australia providers, peak bodies, and government organisations in Australia and the United Kingdom, as well as job-seekers, on opportunities for streamlining administration and industry-supported solutions to reduce unnecessary administration. Twenty-nine submissions were received in response to the Advisory Panel’s discussion paper, with further consultations held with stakeholders in early 2012 before the panel’s final report was released in September 2012.

- Employment Services—Building on Success, Issues Paper—following the release of the paper in December 2012, 37 consultation sessions were held across the country in early 2013, with 440 attendees representing around 300 organisations and businesses. The sessions were targeted at particular stakeholder groups including: employers; academics; job-seekers; and service providers and community organisations. In March 2013, a Key Stakeholder Forum was attended by approximately 60 peak body representatives, and 180 written submissions were also received in response to the paper.

2.13 While the public consultations in 2013 were not explicitly referenced in the June 2014 proposal to government, feedback that had been obtained by the department was incorporated in the earlier versions of the model and was aligned to the final design.

2.14 In August 2014, Employment also sought public feedback on the exposure draft to the Request for Tender, with amendments to the design made as a result of the 60 submissions received from potential providers, employers, peak bodies, and community sector representatives.

Was sound advice provided to the Government on design options and recommendations?

Employment provided sound advice to the Minister for Employment and the Assistant Minister for Employment on a range of design considerations and associated risks.

2.15 The ANAO reviewed the 141 briefings and correspondence from the department to the relevant Ministers for Employment, covering the period from February 2012 to December 2016. The department provided advice to ministers on key matters, including:

- the Work for the Dole program;

- proposed changes to the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme and Harvest Labour Services;

- the performance framework for employment service providers, including Star Ratings and Indigenous Outcome Targets;

- the reduction in the number of employment regions from Job Services Australia;

- the redevelopment of the Quality Assurance Framework;

- finalised evaluations of the Employment Pathway Fund; and

- the publication of the evaluation strategy for jobactive.

2.16 The briefs outlined the benefits and risks for each option, and included a recommendation indicating the department’s preferred option. From October 2014 to December 2014, Employment provided monthly implementation status reports to the Minister, and fortnightly reporting from January to September 2015. Reports included a timeline for key activities and milestones, and the mitigation and monitoring strategies for identified high-level risks and sensitivities.

Has the program design been reviewed and adjustments made where appropriate?

In consultation with providers and peak bodies, Employment has made several changes to the design of the jobactive program. The department established working groups or external reviews to guide improvements to the program.

2.17 Employment has made several amendments to the jobactive program since the program commenced on 1 July 2015. For example, in October 2015 following feedback from providers and peak bodies, Employment suggested twelve refinements to the Minister, which were agreed. These amendments included that the department:

- allow employment service providers to submit supplementary payslip information from employers if the payslips do not meet minimum requirements;

- consider pre-existing employment arrangements for employment outcomes;

- consider renegotiating sites with a low number of job-seekers on a case-by-case basis and where there are exceptional circumstances; and

- consider options for using the Employment Fund for non-accredited training and capping the expenditure per job-seeker or per course.11

2.18 Employment has also made changes to the design of two specific components of jobactive—Work for the Dole12 and Harvest Labour Services.

Changes to Work for the Dole

2.19 In August 2015, Employment established a Work for the Dole Working Group with representatives from employment service providers, Work for the Dole Coordinators and peak bodies. The Working Group identified 12 issues with the new Work for the Dole model, including: the administrative impost on Lead Providers13, and the financial risks of upfront payments required for job-seekers on the caseload of a different employment service provider; insufficient time to commence a job-seeker in a Work for the Dole place; and poor collaboration between employment service providers and Work for the Dole Coordinators.

2.20 In response to the Working Group findings, Employment made 11 recommendations to the Minister for amendments to the model, which were agreed. The subsequent changes to the Work for the Dole model included:

- allowing Lead Providers to reserve places in the system, before advertising them as available to other employment service providers;

- introducing a ‘Lead Provider Payment’ of up to $100 per place to recognise the role the Lead Provider undertakes when managing job-seekers from non-lead providers in Work for the Dole activities14;

- extending the timeframe for when job-seekers need to commence in an activity (from five days to 10 days); and

- expanding the Employment Fund guidelines to allow providers to pay for police checks for its job-seekers.

Changes to Harvest Labour Services

2.21 In April 2016, the Employment Steering Committee agreed that a review of Harvest Labour Services would be undertaken.15 The scope of the Review included:

- the exclusion of harvest placement fees to Labour Hire Companies;

- the definition of ‘harvest work’, as planting and non-horticultural crops (for example, forestry) were excluded under the Deed; and

- the ongoing viability of the Harvest Labour Service given the changes in the industry since the program was introduced in 1998.

2.22 The Review was finalised in June 2016 and made 11 recommendations. The Review concluded that the while the program is small (within the context of the jobactive program, and when compared to the overall number of seasonal workers required to support the agricultural sector) it is highly regarded by stakeholders and valued by the sector. The Review suggested that (subject to any Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines issues being satisfied) the Harvest Labour Service be amended so that providers would be able to claim placement fees: for placing workers with Labour Hire Companies; and, for a broader range of work including plant and animal cultivation, fishing and pearling, and tree farming and felling.16

2.23 The jobactive Deed was varied in April 2017 to expand the scope of eligible employers to include Labour Hire Companies and Contractors. Employment has not addressed the other suggestions made in the review.

3. Governance arrangements for ongoing management

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Employment’s (Employment’s or the department’s) arrangements for the ongoing management of the jobactive program, including governance and oversight arrangements, the management of risk, and the guidance available to the providers of the five services.

Conclusion

Employment has established a suitable committee structure to oversee the jobactive program and the department has identified and managed risks at the program and provider level. The prioritisation of activities to deliver the program could be improved to ensure that required activities are completed. The principles-based guidelines do not always clearly articulate Employment’s expectations of providers.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving the risk-based prioritisation of activities to deliver the jobactive program.

Have appropriate oversight arrangements for ongoing management of jobactive been established?

Employment has established an appropriate governance structure to provide oversight and make decisions about the ongoing management of jobactive. Improved prioritisation of the activities necessary for effective delivery of the jobactive program is needed to ensure that objectives are being achieved.

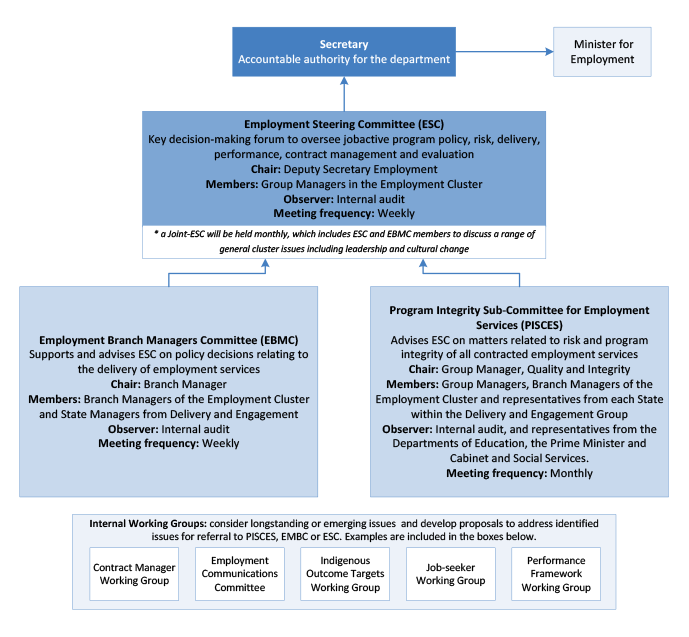

3.1 The committee arrangements that Employment implemented for the ongoing management of jobactive are shown in Figure 3.1. The three committees which oversee jobactive are the: Employment Steering Committee (ESC); Employment Branch Managers Committee (EBMC); and Program Integrity Sub-Committee for Employment Services (PISCES). Meeting minutes and papers are shared between the committees17, and Employment has documented the decision-making responsibilities for the various committees in each terms of reference. An ESC and EBMC Decisions Register is located on the department’s intranet and tracks issues as they progress through to the decision-making stage.

Figure 3.1: Committee arrangements for the ongoing management of jobactive

Source: ANAO representation of departmental documentation.

3.2 Various working groups consider issues and develop proposals to address identified issues for referral to PISCES, EBMC or ESC, but they do not have decision-making responsibility. The issue can be a long standing topic or an emerging issue. Members include Employment staff, or a combination of Employment and external stakeholders depending on the issue being considered. For example, the Performance Framework Working Group was established to resolve ongoing contract management, compliance and performance issues. It includes representatives from Employment, the peak bodies, employment service providers, and Work for the Dole Coordinators.

3.3 Fortnightly reports are provided to the Secretary and the Minister, including information on jobactive caseload, performance outcomes, jobactive and Employment Fund budget and expenditure, and Work for the Dole progress. The Department’s Audit Committee receives a quarterly update on departmental risks and treatments, and fraud and serious non-compliance investigations.

Employment’s prioritisation of program delivery activities

3.4 The jobactive program is administered by the Employment Cluster within the department, as shown in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Organisational arrangements for the Employment Cluster

Source: ANAO representation of Employment’s organisational chart, current as of 10 April 2017.

3.5 The program areas (located in Employment’s National Office)18 and the Delivery and Engagement Group (based around Australia)19 work together on policy, compliance and service delivery. ESC and the National Leadership Team oversee and manage the delivery of these services.20 As at 31 March 2017, resourcing of the Delivery and Engagement Group included 270 full-time equivalent staff, with 195 of those staff responsible for tasks related to jobactive.21

3.6 The Delivery and Engagement Group undertakes a range of functions, including business-as-usual, program specific and ad-hoc activities. The business-as-usual activities include regular engagement with providers, and assessing the delivery of provider service commitments. Program activities may be identified by the program areas as requiring action, and include provider performance reviews and discussions and program assurance activities. Ad-hoc activities may include procurement exercises, program evaluations, conferences, webinars, and learning and development activities.

3.7 National Office informs the Delivery and Engagement Group of required tasks by:

- a Delivery and Engagement Group Calendar, updated quarterly, which details planned program specific and ad-hoc activities;

- a teleconference held monthly, where program areas can provide information directly to the Delivery and Engagement Group about ‘hot issues’;

- an email distributed weekly by National Office to communicate outstanding and upcoming tasks and communicate priorities;

- joint representation on relevant working groups, committees, meetings, and teleconferences to share information; and

- a shared central mailbox to facilitate the sharing of information.

3.8 Delivery and Engagement Group staff record the outcomes of many of their contract management activities in an information technology system—Provider 360.22 The information recorded in the system is available to National Office staff. According to Provider 360, in 2015–16 the required number of sites visits were not conducted (discussed in paragraph 4.10), and only 2183 of the 7593 service commitments were assessed (28.7 per cent).

3.9 In May 2016, Employment identified deficiencies in the processes for planning and prioritising work for the Delivery and Engagement Group, and agreed that business processes needed to be improved to ensure that activities were identified, resourced and managed in a consistent, timely and transparent manner. The Delivery and Engagement Group Calendar was identified as the primary tool for allocating tasks to the Delivery and Engagement Group and a revised format was released in March 2017, along with a new protocol aiming to support the consistent and timely identification, management and prioritisation of competing activities. However, the updated Calendar does not include business-as-usual activities, an assessment of the resources expected to be allocated to each task, or a risk-based prioritisation of the tasks to identify which activities may be deferred if necessary. In addition, the status of activities, including completed tasks, is not reported to the department’s executive in a timely manner.

Recommendation no.1

3.10 The Department of Employment should implement a risk-based approach to prioritising the activities required to effectively manage and monitor the delivery of the jobactive program.

Entity response: Agreed.

3.11 Risk and significance are key determinants for the department in prioritising activities required to effectively manage and monitor the delivery of the jobactive program. Noting the recent establishment of the Delivery and Engagement Group calendar and supporting protocol, the department is monitoring its effectiveness and will consider what additional information would be of value to add.

Is program risk appropriately managed?

Employment has established an appropriate framework to manage risks to the jobactive program. While the management of high-level program risks has been generally sound, there is scope for the department to improve the timeliness of monitoring and mitigation actions for identified provider risks. Further, the department should make greater use of compliance and performance data to identify and manage provider risks.

3.12 Employment has an established framework to guide its approach to risk management, with internal guidance and tools made available to assist staff.23 Employment manages the risk to the jobactive program through the jobactive, program area and provider risk plans.

Program risk management

3.13 The jobactive Risk Plan identifies twelve high-level risks, and 38 associated treatments for the jobactive program. The twelve risks consist of seven which are rated as ‘Medium’, and five which have been rated as ‘Low’. The medium-rated risks relate to:

- fraud by providers;

- injury resulting from providers not adhering to Work Health and Safety principles;

- privacy breaches leading to reputational damage;

- poor performance or service quality leading to reputational damage;

- failing to respond to changed economic or policy environment in a timely manner;

- inappropriate impact on job-seeker income support payments; and

- financial viability of providers impacting on service delivery.

- Other jobactive-program risk plans include the Performance Framework Risk Plan and the Payment Integrity Risk Plan.24

3.14 All ten program areas related to jobactive within the Employment cluster has a risk plan. The plans identify the risks relevant to that program area and the treatments established to mitigate or manage identified risks. The risks include program risks and implementation or delivery risks to the department. The ANAO reviewed the risk plans for the ten program areas, and found 127 unique identified risks and 364 associated treatments. The twelve risks identified in the jobactive risk plan are reflected in program area risk plans.25 All jobactive program and program area risk plans assign owners for each treatment and include a review date. Of the 608 treatments identified in the 13 risk plans, 590 had been reviewed by the due date. Eighteen (less than 3 per cent) were overdue for review, and none by more than a month.

Provider risk management

3.15 Employment manages the risks associated with outsourcing the delivery of the jobactive program with organisation level risk plans created and maintained for each provider. Where Employment considers that a risk would be better managed at the region or site level, risk plans can be created at that level.26 Providers are assessed against four standard risk categories (fraud, financial viability, governance and compliance) and two variable risk categories (service delivery and performance, and relationships).

3.16 The risk appetite for the department has been set at medium, with a preference to not accept extreme or high risk levels. Employment manages provider risks through risk actions in the risk plan.27 Since May 2016, risk plan ratings have been reported to PISCES, with reports including the date of the last update to the risk plan, overall organisational risk rating, and ratings against each of the categories. A number of overdue risk plans have been repeatedly reported to PISCES without the required review undertaken.28 For example, a provider risk plan with an extreme overall risk rating was only reviewed twice between September 2015 and November 2017, despite the department setting a monthly review period for extreme risks, and the overdue risk plan being reported monthly to PISCES.

3.17 Employment has developed 64 organisation-level risk plans for the 65 providers of the jobactive program.29 The ANAO’s analysis of the 64 risk plans found:

- 28 (43.7 per cent) of the 64 plans had an overall rating of extreme or high;

- 15 (53.6 per cent) of the 28 plans with an overall rating of extreme or high were due to perceived financial viability risk. Other high risk categories were service delivery and performance (35.7 per cent), compliance (28.6 per cent), governance (21.4 per cent), and fraud (3.6 per cent);

- two (7.1 per cent) of the 28 plans with an extreme or high overall rating had no open risk actions recorded, contrary to the department’s risk appetite30; and

- for approximately one-third of all the risk actions it is unclear how the actions will manage or mitigate the identified risk.31

Compliance and performance data in provider risk plans

3.18 Employment generates various compliance and performance data, including the Rolling Random Sample and Compliance Indicator (discussed further in Chapter 4) and the Star Ratings performance measure (discussed further in Chapter 5). In the risk plans for the 44 employment service providers there is some recording of compliance and performance data, with:

- 21 (47.7 per cent) of the 44 plans mentioning the Rolling Random Sample—with 11 (52.4 per cent) of these including data;

- 14 (31.8 per cent) of the 44 plans mentioning the Compliance Indicator—with 11 (78.6 per cent) of these including data; and

- 31 (70.5 per cent) of the 44 plans mentioning the Star Ratings—with 28 (90.3 per cent) of these including data.

3.19 The department should make greater use of compliance and performance data to identify and manage provider risks.

Do the guidelines clearly articulate Employment’s expectations of providers?

Employment has established a principles-based approach for the jobactive guidelines to allow providers to deliver flexible solutions tailored to an individual job-seeker’s circumstances. On occasion, this has led to some inconsistency in the interpretation and application of the guidelines.

3.20 Guidance to providers in jobactive is principles-based. Employment advised that it changed from the prescriptive approach used in Job Services Australia to improve the servicing of job-seekers, with the intention that providers would be able to deliver flexible solutions based on a job-seeker’s circumstances.

3.21 When re-designing the guidelines, Employment advised the Minister that the Job Services Australia guidelines had been long and required providers to cross-reference to various sources. The department further advised the Minister that the new jobactive guidelines had been designed so that all relevant program information was consolidated.32 The ANAO’s review of the department’s guidance found that, in addition to the two jobactive Deeds, there are 31 guidelines that providers of the jobactive program need to adhere to, as well as additional information and factsheets. The guidelines cover broad topics, such as the Documentary Evidence Guideline, or more specific matters, such as Relocation Assistance to Take Up a Job Guideline. Each guideline contains a disclaimer which states:

This Guideline is not a stand-alone document and does not contain the entirety of Employment Service Providers’ obligations. It must be read in conjunction with the Deed and any relevant Guidelines or reference material issued by the Department of Employment under or in connection with the Deed.

3.22 The ANAO’s analysis of the guidelines found that multiple guidelines may need to be reviewed to answer a single question and, in some areas, the guidelines are unclear and/or inconsistent. For example, the requirement for New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS) participants to complete mutual obligation requirements (primarily monthly job searches). Relevant guidance about mutual obligations is provided as follows:

- NEIS Training Guideline—states that participants do not have mutual obligation requirements while in NEIS training;

- Mutual Obligation Requirements and Job Plan Guideline—states that participants will not generally have mutual obligation requirements for the period they are participating in NEIS, and separately states that providers must not enforce mutual obligations while the job-seeker is undertaking NEIS training or the NEIS program; and

- Activity Management Guideline—advises that NEIS training is to be considered an activity like Work for the Dole (which does have mutual obligation requirements), but does not specifically mention mutual obligation requirements.33

3.23 Three of the four NEIS-only providers the ANAO interviewed reported that some employment service providers applied the guidelines inconsistently and required NEIS participants to complete their mutual obligation requirements while in the program.

3.24 Providers seeking further guidance from the department about the guidelines are directed to use Question Manager34, so that answers are visible to all and the department can gain insight into which areas the providers are requesting clarification. Employment considers that the centralisation of responses to guideline queries should also improve the consistency of department messaging.

3.25 As at 15 February 2017, there were 833 queries in Question Manager that related to the jobactive program.35 The ANAO reviewed 328 of the queries (39.4 per cent)36 and analysed 231 (27.7 per cent of the total)37, to assess which topics the providers were requesting clarity on, and the responses the department provided. The ANAO’s analysis found:

- recurring query topics related to definitions of self-employment and permissible breaks, the feasibility of combining income from multiple jobs to achieve an outcome, clarifying if the provider could employ the job-seeker, and how to account for new, pre-existing or recurring employment with the same employer;

- the majority of queries were escalated and answered by National Office (59.3 per cent), with 32.5 per cent answered by the Delivery and Engagement Group and 8.2 per cent answered by the State Office; and

- in 26.0 per cent of the responses (60 of the 231) the department quoted the guideline and did not provide additional clarification.

3.26 Employment has not analysed the data contained within Question Manager since December 2015, despite noting in a paper to ESC that using the business intelligence within Question Manager would enable the Employment Cluster to consider: topics that require further policy clarification; the effectiveness of guidance material; workload management and planning; and identify training and education opportunities for departmental and provider staff.38

Rolling Random Sample

3.27 The Rolling Random Sample is a compliance activity that Employment uses to gain assurance that the claims submitted by providers are compliant with the requirements of the Deed(s) and guidelines (the Rolling Random Sample is discussed further in Chapter 4). As the jobactive guidelines are principles-based, it is important that the assessment undertaken for the sampled claims does not impose prescriptive elements that are not included in the guidelines. The ANAO’s review of the assessment guidance used by Employment staff, found that it was consistent with the Deed(s) and program guidelines.

3.28 As noted in paragraph 3.25, the ANAO found several examples where providers sought clarification on a guideline and Employment’s response was to quote the guideline, often caveating its response with ‘for any claims lodged, a jobactive provider must ensure that they have met all requirements outlined in the jobactive Deed and jobactive guidelines’, or similar. The employment service providers consulted by the ANAO were concerned that if the department interpreted the principles-based guidelines in a different manner than the providers when they submitted their claims for payment, this may result in poor compliance results in the Rolling Random Sample. For example:

- in line with advice provided through Question Manager, in July 2015 a provider claimed $231 related to pre-employment medical costs;

- as a result of the first quarter of the Rolling Random Sample, the claim was incorrectly recovered by the department on the basis that the claim related to ineligible medical costs; and

- in April 2017, Employment advised the ANAO that this recovery should not have occurred as the claim was legitimate, and the incorrect recovery has been rectified.

Review of the guidelines

3.29 Since July 2015, Employment has released updated versions of the jobactive program guidelines on a quarterly basis (when deemed necessary to reflect changed or clarified policies).

May 2016 guideline review

3.30 In May 2016, Employment held a Stakeholder Working Group to review and streamline the jobactive guidelines, with an aim to reduce administration and drive practice improvement while ensuring that the basic requirements and principles were effectively communicated to the providers’ front-line staff.

3.31 The working group had three sub-working groups. Providers were represented on the sub-working groups, allowing them the opportunity to give feedback about the guidelines and input into the review. The sub-working groups made 79 suggestions for improvement, including formatting proposals, subjects that required further clarification, removing outdated Job Services Australia related documents from the Provider Portal39, and moving some information from the guidelines into the Deed(s). The Stakeholder Working Group agreed to consider 69 of the suggested changes (87 per cent).

3.32 As a result of the guideline review, Employment engaged an external consultant to redesign the guideline template and, in March 2017, began transitioning the guidelines to the new format over a number of quarterly publishing schedules. Employment has advised that the transition to the new format should be completed by late October 2017.

4. Program assurance of providers

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Employment’s (Employment’s or the department’s) arrangements to manage provider compliance with contract requirements, with a focus on the activities for employment service providers.

Conclusion

Employment has obtained a reasonable level of assurance that the jobactive program is being administered as designed and expected. The Assurance Strategy for the jobactive 2015–2020 contract includes new program assurance elements that have strengthened the department’s monitoring of employment service provider’s compliance with contractual obligations. While the department is currently reviewing the operation of the Assurance Strategy, the review does not address some of the key elements of the program, including whether the strategy reflects the department’s preferred level of compliance.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation addressing whether the compliance regime is structured to effectively and efficiently detect and manage non-compliance.

Has a provider compliance framework been established?

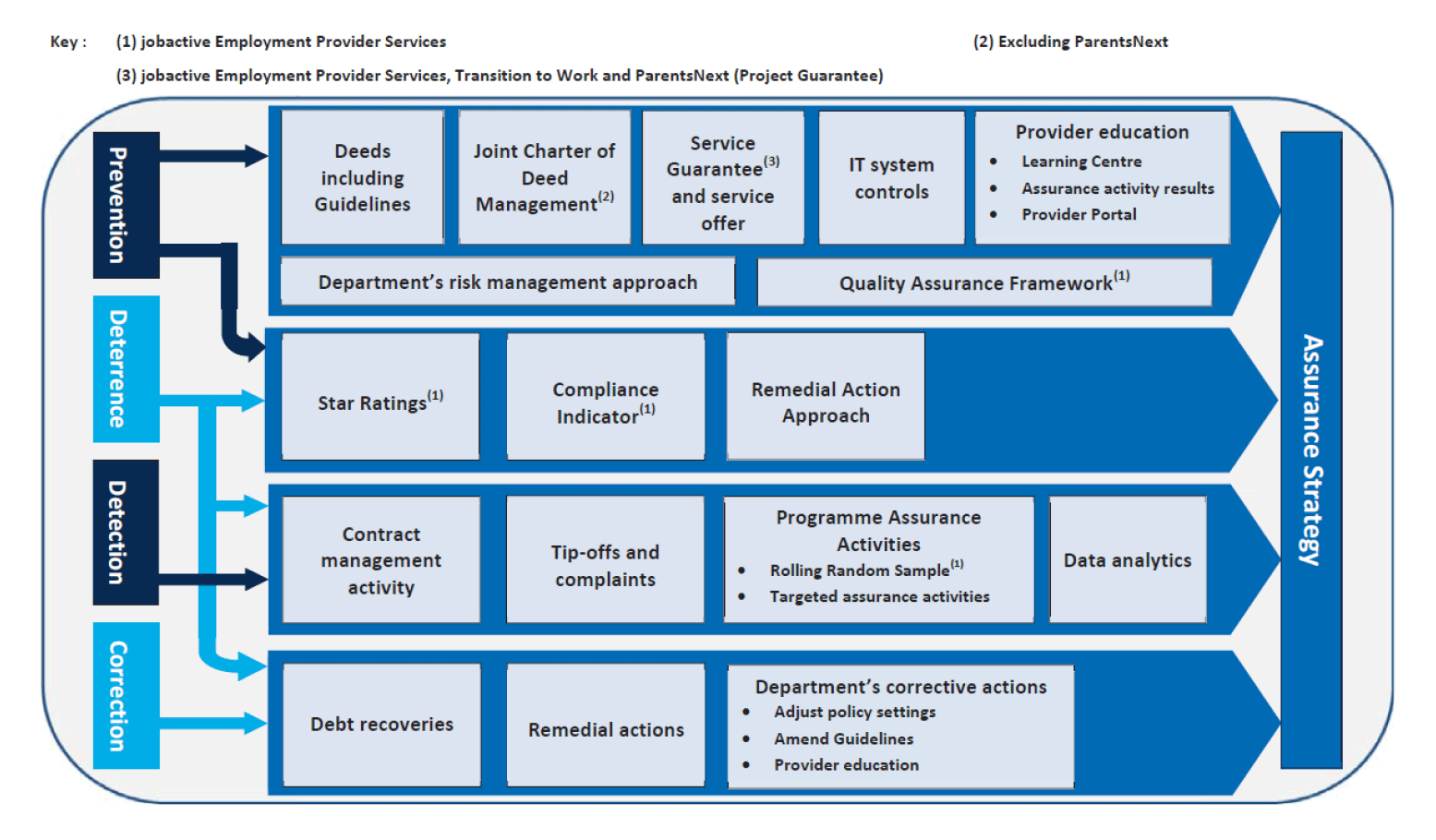

Employment has established a comprehensive framework to manage provider compliance that incorporates approaches to prevent, deter, detect and correct non-compliance.

4.1 Employment has established arrangements to provide assurance that the contracted services are effective and of suitable quality. Contractual arrangements are set out in the: Deed(s) (the jobactive Deed 2015–20 and the jobactive Work for the Dole Coordinator Deed 2015–20) and associated guidelines; Service Delivery Plans for each employment service provider40; Service Guarantees41; and the Joint Charter of Deed Management between Employment and the providers.42 The obligations for employment service providers broadly focus on:

- the provision of employment services to job-seekers and employers;

- meeting standards of service and behaviour;

- claiming payments according to the Deed(s) and guidelines; and

- the Service Delivery Plans submitted by each provider during the tender process.

4.2 Compliance with the terms of the Deed(s) is managed through the Assurance Strategy, as outlined in Figure 4.1. The Assurance Strategy is Employment’s framework for managing contractual compliance and aims to: encourage providers to voluntarily comply with requirements; describe the remedial actions that apply where non-compliance is identified; and state the target areas of risk. Employment employs four strategies to provide assurance that employment service providers are compliant with the terms of the Deed(s):

- Prevention—making it easier for providers to comply;

- Deterrence—making clear the risks and penalties of non-compliance;

- Detection—processes are in place to identify non-compliance; and

- Correction—acting on detected non-compliance.

Figure 4.1: Employment’s Assurance Strategy

Note: The Transition to Work and ParentsNext programs are outside the scope of this audit.

Source: Employment documentation.

Is employment service providers’ compliance with obligations effectively monitored?

Employment has a framework to monitor employment service providers’ compliance with contractual obligations. The framework enables the department to obtain a reasonable level of assurance about employment service providers’ compliance. There is scope to improve the analysis of complaints data, the provision of Rolling Random Sample results to providers in a timely manner, and the effective prioritisation of targeted assurance activities.

4.3 The key activities of the Assurance Strategy that Employment uses to monitor employment service provider compliance with the terms of the Deed include activities to monitor service provision and quality such as: Quality Assurance Framework certification; contract management activities including site visits; and tip-offs and complaints. Assurance activities to monitor the appropriateness of claims include: Rolling Random Sample reviews of key program elements; targeted program assurance projects of employment services; and data analytics to identify emerging risks. Each of these components is discussed below, and Employment’s management of identified non-compliance is discussed later in this chapter.

Quality Assurance Framework

4.4 The Quality Assurance Framework (QAF) was introduced following completion of a pilot program in 2014. The QAF was established in response to feedback from employment service providers and peak bodies that the quality framework used under Job Services Australia to assess employment service provider performance did not provide sufficient practical information to measure continuous improvement in service quality. The QAF aims to provide assurance that the services delivered by employment service providers are to an agreed standard, while encouraging continuous improvement.

4.5 Participation in the QAF process is mandatory for the 44 employment service providers, and involves a certification audit, a surveillance audit every two years and extraordinary audits at the department’s discretion. To obtain and maintain certification under the QAF, employment service providers are required to:

- be assessed by an independent auditor against a quality standard deemed acceptable by Employment43; and

- maintain adherence to seven overarching quality principles that are consistent with the QAF and program objectives, for the duration of the contract.44

4.6 The deadline for QAF certification was 1 July 2016. By the deadline, 41 of the 44 employment service providers were certified. Of the three that did not achieve certification by the deadline, one was certified in July 2016, one in September 2016, and one is not certified as at April 2017.45

4.7 Employment’s implementation of the QAF included one evaluation and two reviews of specific aspects of the QAF.46 The evaluation and reviews had similar findings, including:

- the QAF has the potential to drive continuous improvement in the longer term for delivering services to job-seekers and, to a lesser extent, employers but is currently unable to measure the impact of the QAF; and

- the time and costs associated with preparing for and conducting the certification audits was greater than expected.47

4.8 In December 2016, ESC endorsed streamlining and scope changes to the QAF process. The new approach is intended to be in place for the 20 re-certification audits and 24 surveillance audits scheduled from June 2017. The changes aim to address the concerns raised in the reviews and include: developing support materials for staff and providers; aligning similar practice requirements with the quality standards; streamlining and removing duplicated requirements; and clarifying terminology, including developing a glossary of terms.

Contract management activity

4.9 The primary purpose of contract management activities is to monitor and assess performance against the Service Delivery Plans and the Service Guarantees.48 Contract management activities include: provider site visits; review of providers’ self-assessments of performance required under the Deed (discussed in Chapter 5); and monitoring the delivery of employment services by the provider. Results of these activities assist to inform ongoing and targeted program assurance activity.

4.10 In October 2015, the Program Integrity Sub-Committee for Employment Services (PISCES) agreed that routine announced visits would be conducted in at least one site in each region where an employment service provider delivers services each financial year.49 With 44 employment service providers operating in between one and 29 employment regions each, this equates to a minimum of 202 visits each year. Employment reported to PISCES in June 2016 that ‘Provider site visit numbers are below expected benchmark due to competing priorities in the State Network. Site visit targets will be reviewed for next financial year’. The ANAO’s analysis of the number and location of site visits found that visits were conducted in 200 employment service provider regions during 2015–16. By 20 April 2017, Employment had completed 112 of the 202 targeted visits for 2016–17 (55.4 per cent).

4.11 Information from contract management activities are recorded in several systems including Provider 360 and/or TRIM. The ANAO’s analysis of the information gathered during routine site visits found gaps in the information recorded in Provider 360, with 12 of the 44 employment service provider files in Provider 360 not having a record of the required information. Intelligence and issues are also recorded in the Program Assurance Tool, the Rolling Random Sample assessment tool, and shared drives; however these systems are not accessible to all staff. With information not available or easily accessible in one source, the value of the information gathered from contract management activities is reduced and hinders Employment’s ability to identify non-compliance and trends in provider behaviour.

Tip-offs and complaints

4.12 Intelligence and feedback about providers and their activities can be provided to the:

- Employment Services Tip-Off Line (ESTOL) by current and former employees of providers; and

- Employment Services National Customer Service Line (NCSL) that provides an avenue for job-seekers, employers or other relevant parties.50

4.13 Reporting of tip-off data from ESTOL (including allegations and actions taken by Employment) is provided to PISCES on a monthly basis. Employment reported that 36 per cent of the 58 jobactive tip-offs received via ESTOL in 2015–16 related to business operations, and 27 per cent related to the Work for the Dole program.51 Of the 47 finalised complaints, 38 per cent were substantiated and resulted in ongoing monitoring of the provider’s operations or the provider being reminded of its obligations.

4.14 In 2015–16, the NCSL received 16 969 complaints about providers, which accounted for 30 per cent of the 57 293 contacts received about the jobactive program.52 Employment investigates individual complaints made against employment service providers, but does not analyse trends in the data received through the NCSL. Analysing this complaints data would assist Employment to detect employment service provider non-compliance.

Rolling Random Sample

4.15 The Rolling Random Sample is a major component of the Assurance Strategy introduced for the jobactive program.53 The principle objective of the Rolling Random Sample is to provide assurance that the jobactive program is being delivered as expected by providing: a comparative measure of employment service provider compliance; and intelligence to assist Employment to manage provider and program risks. The Rolling Random Sample involves reviews of a sample of claims or activities from each of the 44 employment service providers. Reviews are undertaken quarterly to verify: if the services were delivered; and the appropriateness of the documentary evidence that supports the claim or activity. The claims for the quarter are drawn randomly from within the focus areas being reviewed, with the sample stratified by transaction type.54

4.16 The Rolling Random Sample process is described below:

- Employment selects the sample and requests evidence from providers to support the claims;

- Employment staff around the country initially assess whether the sampled claims adhered to the Deed(s) and guideline requirements;

- a portion of the sample is quality assured55, which involves verifying the initial assessment, a consistency check to ensure uniformity around the country, and a final review to check provider consistency;

- if necessary, changes will be made to the assessment;

- employment service providers are advised of the preliminary outcome of the assessment and have the opportunity to dispute an assessment by showing cause and providing additional evidence prior to the assessment being finalised; and then

- Employment finalises the assessment and recovers payments where appropriate.

4.17 The finalised claim is categorised as: satisfies requirements; requirements mostly satisfied (no demerit); requirements partially met (demerit); or requirements not met (payment recovery). The demerit result is applied to the Compliance Indicator score (discussed from paragraph 4.27).

4.18 The ANAO analysed the results for the first three quarters of the sample, see Table 4.1, and found:

- the number of quality assurance reviews undertaken in the third quarter decreased substantially from the earlier quarters (13 per cent of the total sample, compared to greater than 60 per cent in the first two quarters);

- the number of decisions changed due to the quality assurance process remains high, with 67 per cent changed in quarter 356; and

- a high number of decisions were amended following the show cause/dispute process, ranging from 88 per cent in quarter 1 to 59 per cent in quarter 3.57

Table 4.1: Rolling Random Sample results for quarter 1 to quarter 3, July 2015 to March 2016

|

Key statistics |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Total |

|

Total population of eligible claims for the quarter |

34 748 |

76 375 |

142 336 |

253 459 |

|

Initial assessment |

||||

|

Number of claims sampled (as a percentage of total population) |

3900 |

3387 |

5026 |

12 313 |

|

Claim result following initial assessment |

||||

|

Satisfactory requirement |

1985 |

1862 |

2890 |

6737 |

|

Requirements mostly satisfied |

963 |

814 |

1361 |

3138 |

|

Requirements partially met |

288 |

310 |

480 |

1078 |

|

Requirements not meta |

664 |

401 |

295 |

1360 |

|

Quality assurance process |

||||

|

Number of claims quality assured (as a percentage of claims initially assessed) |

2362 |

2175 |

638 |

5175 |

|

Initial assessment changed due to quality assurance (as a percentage of quality assured claims) |

831 |

491 |

430 |

1752 |

|

Show cause / dispute process |

||||

|

Number of claims disputed by employment service providers (as a percentage of claims initially assessed) |

328 |

338 |

447 |

1113 |

|

Preliminary assessment changed due to show cause and dispute process (as a percentage of quality assured claims) |

289 |

253 |

263 |

805 |

|

Final claim result (and outcome) |

||||

|

Satisfactory requirement |

2286 |

2010 |

2993 |

7289 |

|

Requirements mostly satisfied (no demerit) |

1064 |

838 |

1407 |

3309 |

|

Requirements partially met (demerit) |

267 |

285 |

429 |

981 |

|

Requirements not met (demerit and recovery) |

283 |

254 |

197 |

734 |

|

Recoveries |

||||

|

Total amount recovered |

$66 321 |

$109 677 |

$106 341 |

$282 339 |

Note a: An initial assessment of ‘requirements not met’ includes claims assessed by the department as requiring additional documentation from the provider or the payment to be recovered.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental data.

4.19 Following quarter 1, Employment identified that quality assurance was resulting in unforeseen delays and made refinements to the internal processes, including more guidance for quality assessors. As the quality assurance process is a critical step in instilling confidence in the Rolling Random Sample process internally and with providers, further consideration should be given to why such a high number of assessments continued to be changed as a result of the quality assurance process.

4.20 Employment advised that the focus of the Rolling Random Sample for the first year was on educating employment service providers. However, Employment has not published advice regarding lessons learnt until after the subsequent sample had been requested or provided the Rolling Random Sample outcomes to employment service providers in a timely manner.58 This makes it difficult for providers to apply learnings from the results.59

4.21 As shown in Table 4.1 the volume of claims assessed as ‘requirements not met’ improved over the first three quarters. However, Employment has not articulated a compliance target that signals the level of non-compliance it is willing to accept. Nor does it extrapolate the findings of the Rolling Random Sample across the population of similar claims. There would be value in setting a compliance target, estimating the volume of non-compliance, and assessing if it aligns to the department’s risk tolerance levels. For example, Table 4.2 shows the results for Employment Fund claims, if the Rolling Random Sample results were extrapolated to the total population.

Table 4.2: Employment Fund claims

|

Quarter |

Total number of claims |

Sampled claims not meeting requirements |

Extrapolated claims not meeting requirementsa |

|

1 |

26 234 |

206 (6.26%) |

1478 to 1806 |

|

2 |

67 985 |

68 (5.18%) |

3169 to 3873 |

|

3 |

119 883 |

80 (3.75%) |

4054 to 4955 |

Note a: Given the margin of error, there is a 90 per cent likelihood that the number of claims in the population is within this range.

Source: ANAO analysis.

4.22 In December 2016, Employment undertook a review of the Rolling Random Sample assessment process. The review identified five main issues, including that it is unclear how the Rolling Random Sample fits into the overall assurance strategy.60 The department intends to seek further advice on implementing best practice, and expects to respond to the review by mid-2017.

Targeted assurance activities

4.23 Targeted assurance activities can be prompted by information gathered from a single source or a combination of monitoring activities including the Rolling Random Sample, site visits, tip-off line, complaints, or media. Targeted assurance activities may focus on: a specific element of the program (such as Work for the Dole or the Employment Fund); an individual provider or a group of providers; or a specific location or region. Targeted assurance activities can be undertaken by various areas across the department.