Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Job Placement and Matching Services

The objective of the audit was to assess whether DEWR's management and oversight of Job Placement and matching services is effective, in particular, whether: DEWR effectively manages, monitors and reports the performance of JPOs in providing Job Placement services; DEWR effectively manages the provision of matching services (including completion of vocational profiles and provision of vacancy information through auto-matching) to job seekers; Job seeker and vacancy data in DEWR's JobSearch system is high quality and is managed effectively; and DEWR effectively measures, monitors and reports Job Placement service outcomes.

Summary

Background

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) contributes to the Australian Government's employment outcome to provide efficient and effective labour market assistance by administering working age income support payments, and labour market programmes. Through these activities, DEWR assists people to participate actively in the workforce in order to reduce the social and economic impacts of reliance on income support.

The various employment programmes administered by DEWR are delivered under the Active Participation Model (APM), which has been the policy platform for the department's employment services since July 2003.

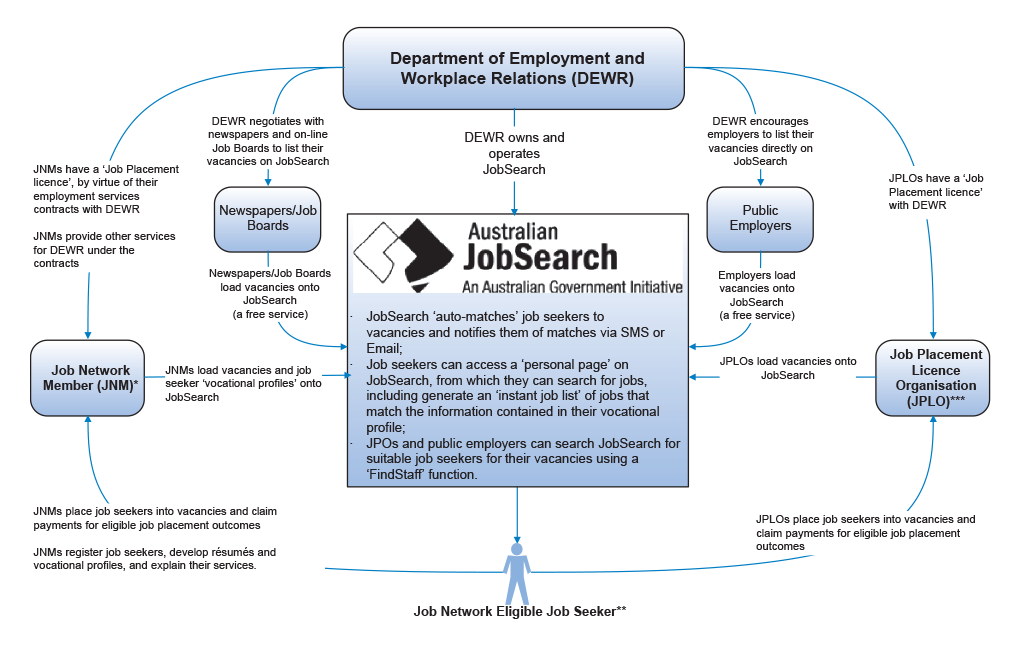

As part of the APM, DEWR administers Job Placement and matching services, which have a dual purpose of helping job seekers to find work, and employers fill vacancies. Job Placement and matching services is the successor to the employment exchange arrangements under previous Job Network contracts and the former Commonwealth Employment Service. The primary objective of these services is to increase the speed and efficiency with which vacancies are filled in the labour market. Employment exchange through Job Placement and matching services is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Employment exchange (currently Job Placement and matching services)

Source: DEWR.

Job Placement and matching services are outsourced. Services are provided under contract (known as a ‘licence') by around 375 Job Placement Licence Only (JPLO) organisations1 and 110 Job Network Members (JNMs), which automatically have a Job Placement licence by virtue of their employment services contracts with DEWR2. Collectively, these organisations are known as Job Placement Organisations (JPOs).

JPOs canvass employers for jobs and load the vacancies onto DEWR's national vacancy database, JobSearch. JNMs also load job seekers' particulars, skills and occupational preferences (‘vocational profiles') onto JobSearch. This enables electronic job matching of job seekers with vacancies, in addition to traditional job matching activities conducted by JPO staff and job seekers. All eligible job seekers receive Job Placement and matching services for as long as they are registered with Centrelink or a JNM. There are two levels of eligibility: job seekers on a specified income support payment who are registered with Centrelink or a JNM3 are classified as ‘Fully Job Network Eligible' (FJNE); other job seekers can register as ‘Job Search Support Only'.

JPOs can claim Job Placement outcome payments when they have sourced a vacancy from an employer, and placed an eligible job seeker in that vacancy for a specified length of time. The outcome payments range from $165 to $385 per placement, depending on the job seeker's characteristics and the length of the placement. The outcome payments are weighted towards FJNE and highly disadvantaged job seekers. A bonus payment of $165 may also be paid for the placement of FJNE job seekers who work for a longer period. The total cost of Job Placement and matching services in 2004–05 was in the order of $176 million, comprising outcome payments for JPOs, service fees for JNMs, and DEWR's administrative costs. Figure 2 illustrates the Job Placement and matching arrangements.

Figure 2 Job Placement and matching arrangements

Source: ANAO.

Audit objective

The objective of the audit was to assess whether DEWR's management and oversight of Job Placement and matching services is effective, in particular, whether:

- DEWR effectively manages, monitors and reports the performance of JPOs in providing Job Placement services;

- DEWR effectively manages the provision of matching services (including completion of vocational profiles and provision of vacancy information through auto-matching) to job seekers;

- Job seeker and vacancy data in DEWR's JobSearch system is high quality and is managed effectively; and

- DEWR effectively measures, monitors and reports Job Placement service outcomes.

Overall audit conclusion

DEWR effectively managed the implementation of Job Placement and matching services. Until mid-2003, the government's employment services were outsourced to Job Network Members (JNMs) that provided these services, then known as Job Matching services. On 1 July 2003, as part of the introduction of the government's Active Participation Model (APM), DEWR contracted around 110 JNMs to provide Job Placement and matching services, and opened up the Job Placement market to an additional 375 commercial recruitment organisations (Job Placement Licence Only organisations—JPLOs), many of which had little or no history of engaging with government agencies in the delivery of employment services. DEWR has been successful in encouraging JPLOs to use their licences—JPLOs now make around 37 per cent of all eligible placements. JPLOs and JNMs are collectively known as Job Placement Organisations (JPOs).

As part of the APM, DEWR introduced mandatory interviews for newly registered job seekers to collect information relevant to the provision of employment services, to access a range of self-help services and to include them in electronic matching, a system which facilitates the on-line matching of job seekers to vacancies. DEWR has worked with JNMs to identify and overcome challenges that arose with the implementation of these services, including a lack of support for matching mechanisms from the industry, concerns about the quality of job seekers ‘vocational profiles' and the capacity to produce quality résumés for job seekers using supporting information systems. DEWR has substantially streamlined and improved these services, although there are still some difficulties to be resolved.

DEWR has been successful in increasing the number of vacancies listed on its on-line national vacancy database, JobSearch. Over 2.2 million vacancies were created on JobSearch in 2004–05, a substantial increase over previous years. This increase was largely the consequence of the inclusion of vacancies from commercial on-line job boards, MyCareer and CareerOne.

DEWR's ongoing management and oversight of Job Placement and matching services would be strengthened by improvements in the following areas:

- monitoring of the quality of the services provided by JPOs against the Job Placement services Code of Practice;

- clarifying resources requirements and expectations for new referral interview services with JNMs;

- improving the quality of vacancy data on JobSearch, the government owned on line vacancy listing enterprise;

- following-up the government's intention to review the costs and benefits of maintaining a national vacancy database, such as JobSearch; and

- more transparently reporting overall service performance, especially by reporting Job Placement outcomes in a manner that is comparable over time.

To effectively manage contractual arrangements, the contracting party needs reliable feedback on the performance of the contractor in meeting its contractual commitments. While the quantitative data available to DEWR contract managers on the placement and vacancy lodgement activity of JPOs is sound in itself, it is limited when it comes to the service requirements of the Job Placement licence. Most significantly, there is no systematic monitoring, through a program of site visits, of the compliance of JPOs with service commitments made in the Job Placement licence and the Code of Practice (which forms part of the licence).

To enable electronic matching, JNMs are required to conduct new referral interviews with job seekers, part of which involves entering job seekers' ‘vocational profiles' onto JobSearch. This has been a time consuming and costly undertaking that has, to date, resulted in few job placements. A small proportion of job seekers benefit from electronic matching. Placements attributable to electronic matching accounted for around 1.3 per cent of eligible placements in 2004–05. The ANAO concluded that DEWR should assess the resources required by JNMs to deliver the new referral interview services and clarify its expectations in relation to those services. This would assist DEWR to assure itself that the appropriate balance between price, resource requirements, and outcomes has been struck.

DEWR's quality assurance processes provide a reasonable level of assurance that vacancies on JobSearch meet its minimum content requirements. However, vacancies are frequently duplicated, and dated. At any point in time, around 14 per cent of vacancies are duplicated. Over time, the duplication rate is substantially higher, at over 46 per cent, which indicates that re posting of vacancies on JobSearch is very common. Duplicate vacancies can be misleading to job seekers, and also substantially distort DEWR's reporting of vacancy numbers. Old vacancies are unlikely to result in a placement. While DEWR has advised that it has now taken steps to reduce the rate of duplication of vacancies sourced from the on-line job boards and to reduce the number of dated vacancies on JobSearch, it needs to take steps to minimise the incidence of duplication more generally and to take duplication into account in its reporting of vacancy numbers.

At the time JobSearch was established (1996), the on-line vacancy listing market was immature. As a result, the government accepted that there was a case for JobSearch to be publicly owned and operated. However, the government also anticipated that the on-line vacancy market would mature and considered that public ownership may not be necessary in the long-term. Consequently, the government considered, at that time, that a review should be conducted at a later date of the continued need for DEWR to maintain JobSearch. No such review has occurred. The ANAO concluded that, in light of the government's original intention and the subsequent maturing of the on-line vacancy listing market, a review should be conducted of the costs and benefits of maintaining a government owned and operated on line vacancy listing enterprise, aside from the necessary business functions, currently within JobSearch, that support contracted employment service providers.

Reporting of Job Placement and matching performance is not consistent or transparent. DEWR has reported ‘record' Job Placement outcomes for 2003–04 and 2004–05 of 518 350 and 665 868 respectively. In the absence of a substantive evaluation it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which the outcomes reported by DEWR for Job Placement and matching services have been affected by exogenous factors such as macro-economic conditions, the state of the labour market, changes in the way job seeker eligibility is determined, or changes in DEWR's capability to capture data on employment outcomes. DEWR has reported ‘outcomes' on the basis of a performance indicator that includes placements for which DEWR is not prepared to pay JPOs, such as placements that have resulted from job seekers finding their own employment. In such cases, it is not clear that the JPO has always made a significant contribution to the job seeker finding work.

The ANAO reviewed the available evidence and concluded that Job Placement and matching services under the APM is performing at or around the historical levels for previous Job Matching services in terms of eligible placements 4 and post-assistance outcomes, although it is more costly overall—requiring outlays in 2003–04 and 2004–05 between $67 million and $100 million per year more than during the first and second Job Network contracts. The additional outlays reflect the cost of upgrading self-help facilities for job search, such as new touch-screen kiosks, as well as the requirement under the APM that all ‘Fully Job Network Eligible' job seekers attend new referral interviews to register for Job Network services from the date of their receipt of income support payments.5 As a result, the cost per eligible placement is around 40 per cent higher than historical levels. The net impact of the APM on employment outcomes for job seekers should become clearer when DEWR has completed its planned evaluations.

Recommendations

The ANAO made six recommendations aimed at ensuring that DEWR's management and oversight of Job Placement and matching services is effective. DEWR agreed with most of the recommendations. However, it disagreed with three parts of the recommendations relating to: developing objective indicators for key service commitments; specifying the quality of résumé it expects JNMs to provide to job seekers; and, assessing the resources required to deliver new referral interview services.

DEWR's response to the audit

DEWR's full response to the proposed audit report is reproduced at Appendix 6, which also includes the ANAO's comments on the response. The ANAO took DEWR's response into account in preparing this report. DEWR's summary response was:

The Active Participation Model which was introduced in July 2003 is achieving record vacancies, placements, and long-term outcomes. Job Placement Services and the introduction of enhanced self-help facilities have made an important contribution to this result. Significantly, placements for disadvantaged or ‘Fully Job Network Eligible (FJNE)' job seekers are considerably higher under Job Placement Services than they were under Job Matching (ESC2).

The ANAO notes that DEWR has successfully engaged around 375 recruitment organisations to complement around 110 Job Network members in gathering vacancies and placing disadvantaged job seekers into work.

While DEWR has appreciated its opportunity to participate in this audit the department does not agree with some of the ANAO's conclusions, particularly the ANAO's comparison of cost and placement outcomes between ESC2 and ESC3. The department has agreed in part with most of the ANAO's recommendations.

Key findings

Job Placement services (Chapter 2)

There is no specific legislation for Job Placement services. Instead, implementation occurred under executive power. The government gave approval for Job Placement services to be introduced in the context of the implementation of the Active Participation Model (APM) in mid-2003, with the government purchasing the services and making fixed payments for specified placement outcomes. Consistent with this approval, DEWR monitored job placements to ensure they stayed within the agreed national cap of 400 000 places, which was not breached. Initially, it was proposed that placement numbers be allocated at the regional level, with Job Placement Organisations (JPOs) within a region drawing down on the regional allocation. This proposal was not implemented. However, the ANAO found that the reasons for this are not clear from departmental documentation.

Initially, the performance of the Job Placement Licence Only organisation (JPLO) initiative fell short of expectations. To address this issue, DEWR pursued a range of initiatives, including refining licence conditions and making it easier for all JPOs to lodge vacancies onto JobSearch (one of the requirements of the licence) and promoting the licence to JPLOs through its contract managers, peak bodies and other forums. As a result, the performance of JPOs, in particular JPLOs, has improved over time.

DEWR has had a longstanding approach to manage Job Placement licences in a manner that involves limited direct contact with JPOs, and minimal direct monitoring through site visits. There is no mandated requirement or target for site visits and no requirement to record the results of site visits. DEWR's assurance about JPO compliance with contractual obligations relies on remote oversight through ‘desktop monitoring' and information about JPO performance contained in the department's information systems.

Performance information about JPO activity can be readily and reliably extracted from DEWR's mainframe database, known as the Integrated Employment System (IES). Drawing on data contained in IES, DEWR has developed a number of management information reports to manage the delivery of Job Placement services. Generally, these reports provide a sound basis for contract management.

DEWR's data does not provide information about the compliance of JPOs with a number of the service requirements in the Job Placement licence. For example, the licence requires that JPOs ‘have a complaints process of which job seekers and clients are made aware' and that ‘job seekers and clients are advised of the free DEWR customer service line.' In response to previous ANAO audit findings6, DEWR has agreed to establish minimum requirements and targets for site monitoring visits including complaints handling processes of Job Network Members (JNMs). However, DEWR had no process for obtaining assurance about the adequacy of JPLO's complaints handling processes—whether, for example, job seekers were being informed by JPLOs that the service they were receiving was attracting payment from the government and that they had a right to complain, either to the JPLO or to DEWR, if they were not satisfied with the service they have received. There is also no data available on the complaints received by JPLOs from job seekers. In response to the proposed audit report, DEWR advised that from 2006–2009, JPLOs will be required to maintain a complaints register and that it is taking steps to raise job seekers' awareness of the Job Placement Code of Practice and associated complaints mechanisms.

Shortcomings in the data also reduce DEWR's capacity to monitor compliance of claims for outcome payments with the terms of the Job Placement licence. For example, DEWR relies on JPOs self-disclosing if a placement is being made to a ‘related entity' (there are restrictions on a JPO placing a job seeker into a job with an organisation that has a legal association or shared ownership with the JPO). The ANAO found that, from 1 July 2005 to 31 December 2005, around 1.7 per cent of all placements (1 888 out of 111 519) were with related entities. However, JPOs self-identified only around 28 per cent of these placements in the DEWR system, meaning 1 354 probable related entity placements were not appropriately identified.

The low level of self-disclosure means that it is likely that some JPOs have exceeded the number of related entity placements they can make under the Job Placement licence (related entity placement cannot exceed 30 per cent of total placements). The ANAO identified 10 JPOs that had exceeded their caps. In total around 100 placement outcome payments or around $37 000 had been paid for these ‘excess' placements. Moreover, the threshold for a non-related entity outcome payment, in terms of hours worked by the job seeker, is half that for a related entity placement. The total hours worked for each placement is not recorded on DEWR's system. For this reason, it is not possible to identify if the undisclosed related entity placements met the higher threshold in terms of hours worked. If all of the undisclosed related entity placements proved not to meet the eligibility requirements, up to $487 000 may have been paid incorrectly.

DEWR conducts regular ‘programme assurance' projects that provide assurance about payments made to JPOs. These projects involve structured surveys of job seekers to identify instances where the job seeker's recollection of their employment does not match the data entered into DEWR's system by the JPO. These data are used to identify potentially suspect payments and to initiate checks of these and, where appropriate, recover funds. DEWR's data shows that around 5–6.5 per cent of the programme assurance survey responses result in a ‘debt', that is, monies to be recovered from a JPO. In 2004–05, DEWR's programme assurance projects, including random and targeted surveys and State Office activity, identified 1 610 Job Placement outcome payments (approximately $400 675) for recovery. The ANAO estimates, on the basis of DEWR's programme assurance survey results that, overall, around 15 400 Job Placement outcome payments, amounting to approximately $4.67 million were potentially recoverable for 2004–05. However, only 10 per cent of this sum was recovered by DEWR through its programme assurance projects.

DEWR advised the ANAO that conducting program assurance surveys for all claims would be very resource intensive for both the Department and for service providers, and that in its view, the cost of doing so would outweigh the benefits. The ANAO considers the amount of potentially recoverable payments not currently being recovered is relatively high (amounting to nearly five per cent of total annual expenditure on Job Placement outcomes). In seeking to manage, and minimise, the risk of incorrect payments to JPOs, it is important to consider the costs and benefits of ‘post hoc' compliance activity (such as programme assurance projects), and preventative activity that improves the compliance of JPOs with rules governing outcome claims. The latter can be achieved through, for example, improved education of JPOs and their staff, and improved systems controls.

Electronic job matching (Chapter 3)

Under their third Employment Services Contract (ESC3) with DEWR, JNMs provide a new referral interview to eligible job seekers, which includes creating and lodging a job seeker's ‘vocational profile' through DEWR's information systems, and providing a copy of the resulting résumé to the job seeker. A vocational profile is an electronic record of a job seeker's skills, job preferences and work history. The primary objective of developing vocational profiles was to include all job seekers in electronic matching and, thereby, improve the efficiency of the labour market.

JNMs consider that it is job seeker résumés, not vocational profiles, which are the primary record used and up-dated by their employment consultants. DEWR has recognised that the development of quality résumés is an important outcome of new referral interviews. However, DEWR has not specified what constitutes a ‘quality résumé', and development of a quality résumé is not currently a requirement of the ESC3.

The ESC3 anticipated that JNMs would create a vocational profile, and then generate a résumé from these data. DEWR's IT system was designed with this process in mind. DEWR has since made it possible for JNMs to create vocational profiles from a pre-existing résumé. Over 80 per cent of the JNMs surveyed by the ANAO agreed that these changes had improved the quality of services JNMs can provide to job seekers. However, the changes are not reflected in DEWR's contracts with JNMs. The ANAO considers that, in order to assist JNMs in their service delivery and DEWR in its contract management, DEWR should update its contract to clarify both the quality of the résumés it expects its providers to complete for job seekers (within the time constraints of the interview), and to reflect the ways in which résumés and vocational profiles can be created.

Electronic matching of job seekers with vacancies is dependent upon a vocational profile being created at a new referral interview. In developing its proposals for the ESC3, DEWR set prices for the new referral interview on the basis of what the forward budget estimates would allow rather than on the basis of an assessment of the expected time/cost of providing the contracted services. There is a negative perception amongst JNMs of the adequacy of remuneration for new referral interview services. This raises a risk that poor quality vocational profiles may be created, reducing the quality of service delivery and effectiveness of electronic matching. DEWR has not measured the actual time required to provide new referral interview services, including vocational profiles, although late in the audit, it did estimate the time required to complete vocational profiles from résumés already up-loaded into DEWR's system. These data suggest that the systems changes introduced by DEWR have improved the efficiency with which the contracted services can be delivered. The ANAO considers that DEWR should assess the end-to-end resource requirements for JNMs to deliver new referral interview services. This would assist DEWR to assure itself that the appropriate balance between price and service delivery considerations has been struck.

A relatively small proportion of job seekers currently benefit from auto-matching, and the available evidence suggests only a very small number of job seekers are placed as a result—around 1.3 per cent of eligible placements in 2004–05 resulted from auto-matches (4 343 eligible placements). The ANAO estimated, on the basis of the available evidence, that the cost per placement resulting from auto-matching in 2004–05 was between $2 153 and $7 834. This compares to a cost of between $144 and $231 for placements resulting from other means, such as through traditional job search. The lower figure in the range assumes that all vocational profiles were created from a pre-existing résumé. The higher figure assumes that all vocational profiles were created ‘from scratch'. The ANAO considers that these estimates indicate that DEWR should monitor and assess the costs and benefits of its auto-matching operations in order to assure itself that the placements achieved meet the government's intention to match unemployed people to jobs more quickly and efficiently.

Electronic matching enables job seekers to be notified of suitable vacancies through, inter alia, SMS and email. These job seeker notifications broadly meet the government's anti-spam initiative. However, the ANAO considers that DEWR would more fully conform to better practice if SMS and email notifications to job seekers included a functional unsubscribe facility, about which job seekers were informed. DEWR advised that ‘with a 160 character limit on SMS messages, the provision of unsubscribe details in each message would mean that other information provided was virtually useless'. The ANAO notes that this is a constraint faced by all agencies seeking to comply with the anti-spam initiative, and there would be benefit in DEWR consulting the Australian Communications and Media Authority, which administers the Spam Act 2003, about how best to keep job seekers informed about how to unsubscribe from SMS messaging. For example, DEWR might consider periodically reminding job seekers of the unsubscription process. The space constraint does not apply to emails, which do not have a functional electronic unsubscribe facility.

JobSearch (Chapter 4)

The Australian Government, through DEWR, runs an on-line job vacancy listing service called ‘JobSearch'. JobSearch was the first on-line job board in Australia, and has now been in operation for ten years. Since its establishment, the on-line vacancy listing market has become extremely competitive, with commercial job boards such as ‘SEEK', ‘MyCareer' and ‘CareerOne' vying for market dominance. In this context, and with a limited marketing budget compared to the commercial players, maintaining JobSearch's market position has been a challenge for DEWR. Previously rated the most popular on-line employment site, JobSearch now has around 10–20 per cent of the on-line employment market, depending on the measure used. 7

When the government introduced JobSearch, it recognised the potential for development of a private on-line vacancy listing market and, therefore, considered public ownership may not be necessary in the long-term. The government agreed to review the continued need for the then Department of Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs to maintain a National Vacancy Database (JobSearch) as part of the Job Network evaluations. The ANAO found that this review has not occurred.

The number of vacancies created in JobSearch has more than doubled since 1999 to over 2.2 million in 2004–05. The growth has largely resulted from vacancy-sharing arrangements with two of the other on-line job boards. JPLOs initially performed below expectations—they did not reach the expected monthly number of vacancy lodgements until the final months of 2004–05. The inclusion of JPLOs in July 2003 has resulted in a slight overall increase in the number of vacancies lodged. Vacancy lodgement by JNMs and direct lodgements by employers has remained static since 1999.

DEWR has not assessed the impact that increasing vacancy lodgement on JobSearch has had on improving the employment prospects of registered job seekers. The ANAO found that increasing the number of vacancies on JobSearch does not appear to have translated into a commensurate increase in eligible placements. This is because many vacancies are not appropriate to job seekers' occupational preferences (there is, for example, a misalignment between job seekers with a preference for factory or cleaning work and the number of listed vacancies sourced from the commercial on-line job boards in these areas), and job seekers do not compete for vacancies on an equal footing.

DEWR has a reasonable level of assurance about the appropriateness of the content of vacancies lodged on JobSearch, for example, through the use of a ‘blue word' filter that prevents potentially inappropriate vacancies from being lodged on JobSearch. However, the ANAO's analysis has shown that DEWR does not have sufficient assurance about the duplication or age of vacancies listed on JobSearch.

The ANAO estimated that on a point in time basis, the level of duplication was approximately 14.4 per cent, while the average level of duplication on a monthly basis, looking at the flow data, was approximately 46.7 per cent.

During the audit, DEWR advised that it had taken steps to reduce the rate of duplication of vacancies sourced from on-line job boards, which contributed a substantial proportion of the duplicate vacancies on JobSearch. However, the ANAO also found duplication of vacancies sourced from JPOs increased substantially during 2004–05. To date, DEWR's reporting of vacancy numbers has not taken duplication rates into account.

Vacancies created by JPOs on JobSearch do not have an ‘expiry' date. The ANAO found that 50 per cent of vacancies on JobSearch were one week old, or less. During 2004–05, the majority of placements were made within three weeks of the vacancy being lodged on JobSearch. However, the ANAO's analysis shows that 17 per cent of vacancies in JobSearch were over eight weeks old and, based on the 2004–05 results, were unlikely ever to result in a paid placement. During the audit, DEWR advised that it was re-instating weekly ‘batch inactivation' to remove dated vacancies.

Reporting Job Placement and matching service outcomes (Chapter 5)

DEWR has three performance indicators relevant to Job Placement and matching services against which it reports publicly. These are: job placements; post-assistance outcomes; and JobSearch's share of the vacancy listing market.

In reporting job placements, DEWR uses a number of different performance measures. With the introduction of the APM in July 2003, DEWR changed the way it measured its performance in terms of job placements. This resulted in a substantial increase in reported performance from 284 825 ‘placements' in 2002–03, to 518 350 ‘placements' in 2003–04, and 665 868 ‘placements' in

2004–05. However, in reporting these ‘record' outcomes8, DEWR did not explain in its Annual Reports that it had changed the way it measured job placements to include placements where the job seeker may have obtained employment primarily through their own efforts, for which DEWR is not prepared to pay JPOs. In 2005–06, DEWR clarified its performance indicator. Using the original measure, ‘eligible job placements', which excludes placements that had not clearly resulted from the efforts of JPOs, the ANAO found that placements declined with the introduction of the APM, before recovering to slightly higher than historical levels in 2004–05 and 2005–06.

DEWR's second indicator relevant to Job Placement and matching services is for ‘positive outcomes', that is, the proportion of job seekers that are in employment, education or training three months after having been placed in a job. This indicator is measured using a survey of job seekers. DEWR has reported that Job Placement and matching services achieved 74 per cent against this indicator in 2005–06, against a target of 70 per cent. However, DEWR's data also indicates that the most recently surveyed population was younger, better educated and had been unemployed for a shorter period than previous populations. The ANAO suggests that DEWR assess and report on the extent to which demographic differences account for the increase in positive outcomes.

DEWR has not attempted to measure JobSearch's percentage of all advertised jobs in Australia, although there was a publicly stated expectation at the outset of the APM that JobSearch would contain 50 per cent of all advertised jobs. Instead, from 2001–02 to 2003–04 DEWR used the ANZ Bank's Internet job advertisements series to estimate the proportion of on-line advertised jobs on JobSearch. Using this measure, JobSearch's performance showed a steady decline over time, failing to meet its target of 40 per cent. During 2004–05, DEWR changed the way it measures and reports its performance in securing vacancy advertisements for JobSearch. It is too early to judge how JobSearch is performing using the new measure.

At the outset of the Job Placement and matching programme, the government announced that it expected that an additional 650 000 ‘vacancies' would be lodged by JPOs on the JobSearch website over the three year life of the licence. The ANAO found that the number of vacancies lodged by JPOs on JobSearch has been well below expectations. However, DEWR has reported its progress in terms of the number of ‘positions' lodged on JobSearch rather than ‘vacancies'. The terms ‘position' and ‘vacancy' have different meanings within DEWR. ‘Vacancy' means that a vacancy record has been lodged on JobSearch, while the term ‘position' refers to the number of positions vacant for any given vacancy. There may be many positions for a vacancy. For example, on 7 October 2005, there were almost twice as many positions listed on JobSearch as vacancies9. Given the difference between these two terms there is substantial room for confusion, both internally and in DEWR's external reporting, about the numbers presented by DEWR.

Under the Outcomes and Outputs framework, DEWR publicly reports on the cost of its ‘Employment Services' Output (1.2.2) of which Job Placement and matching services is a part. It does not publicly report the particular cost of Job Placement and matching services, although this is reported and monitored internally.

The ANAO found that DEWR's Job Placement and matching arrangements are more costly than the comparable Job Matching arrangements under previous contracts, requiring outlays in 2003–04 and 2004–05 between $67 million and $100 million per year more than during the first and second Job Network contracts. This reflects the cost of upgrading self-help facilities for job search, such as new touch-screen kiosks, as well as the requirement under the APM that all ‘Fully Job Network Eligible' job seekers attend new referral interviews to register for Job Network services from the date of their receipt of income support payments. Self-help facilities cost $61.7 million and $37.2 million in 2003–04 and 2004–05 respectively. New referral interview services, which include, as the major component, the development of a ‘vocational profile' for the purposes of electronic matching (including auto-matching), cost $65.4 million in 2003–04 and $34.36 million in 2004–05.

As discussed, the APM is performing at or around historical levels for previous Job Matching services in terms of eligible placements (which excludes placements that had not clearly resulted from the efforts of JPOs). Consequently, the ANAO found that, after one-off transitional costs in 2003–04, the cost per eligible placement declined during 2004–05, but was still around 40 per cent higher than the average cost of eligible placements in previous contracts.

DEWR advised the ANAO that under the APM, all job seekers were provided with a basic level of service from their JNM, including, at a minimum, ensuring all job seekers have a résumé, and understand and have access to a range of self help services such as interactive JobSearch kiosks, auto matching and notification services. DEWR considers these basic services provide greater capacity for job seekers to be in control of their own job search activity than under previous arrangements. To support these claims, DEWR provided data from its job seeker survey research that shows that the proportion of job seekers that remember being helped by their JNM with a résumé has increased from 31 per cent under ESC2, to 89 per cent under the APM. 10

The ANAO notes that the increase in expenditure that has been required to ensure these minimum service levels are met has not resulted in a commensurate improvement in eligible placements. DEWR's own research has shown that only 54 per cent of job seekers recall completing a vocational profile (résumé)11, and that the frequency of contact between job seekers and their JNMs may have actually declined under the APM, in comparison to previous contracts12. The goal should be to strike an appropriate balance between ensuring minimum service levels are maintained, and maximising employment outcomes.

With the introduction of the APM, and the licensing of JPLOs, the government announced a major increase in the number of organisations and sites providing employment services compared to previous contracts. DEWR's reporting of JPO ‘service coverage' (the number of sites) has not distinguished between sites that are active or inactive. DEWR decided early in the APM that in order to maintain the reported number of sites nominally delivering Job Placement and matching services, unused JPLO licences would not be cancelled unless new providers were able to take their place. The ANAO found that the number of sites actively providing Job Placement services is between 20 and 36 per cent less than the number of sites listed on JobSearch, depending on the measure used. The ANAO considers that DEWR's practice of reporting nominal service coverage may lead Parliament and the public to form a mistaken impression that eligible job seekers receive Job Placement services from all reported sites. Job seekers accessing the JobSearch system may also form the mistaken expectation that all the sites listed provide Job Placement services.

Footnotes

1 JPLOs are mostly private recruitment organisations, but also include organisations contracted to DEWR to provide the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme and Harvest Labour Services. Like JNMs, these latter organisations have a Job Placement licence by virtue of their other contracts with DEWR.

2 JNMs also provide a wide range of other services that are not examined by this audit, including job search training, and intensive support customised assistance. The ANAO has examined these in other audits, including ANAO Audit Report No.51 2004–05, DEWR's oversight of Job Network services to job seekers.

3 To be eligible for Job Placement and matching services, a job seeker must be registered, and must not be: working in paid employment for 15 hours or more each week; a full–time student; an overseas visitor on a working holiday visa; or prohibited by law from working in Australia.

4 The ‘eligible placements' measure excludes placements that had not clearly resulted from the efforts of JPOs.

5 New referral interviews include, as the major component, the development of a ‘vocational profile' for the purposes of electronic matching (including auto-matching).

6 See ANAO Report No.51 2004–05, DEWR's Oversight of Job Network Services to Job Seekers.

7 Using a measure from Hitwise (an Internet monitoring company), based on page visits, JobSearch's market share is around 10 per cent. Using a measure from the Nielson Net Ratings (another Internet monitoring company), based on unique browsers, JobSearch's market share is higher, at around 20 per cent.

8 See DEWR, Annual Report 2003–04, pp. 54, 58-59 and DEWR, Annual Report 2004–05, p. 48.

9 DEWR, Job Seeker Omnibus Survey reports, March 2003 and August 2005.

10 DEWR, August 2005, Using the Job Automatch system.

11 DEWR, APM Evaluation Study 1C: Maintaining the Connection—Keeping Job Seekers in Touch with Job Network Services.