Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Investments by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- To provide assurance over the ongoing management of the portfolio of investment projects and how well the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) is meeting its legislative objective.

Key facts

- The CEFC was established to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector.

- CEFC has been provided with access to $10 billion in capital.

- CEFC invests directly and indirectly, in clean energy technologies.

- Clean energy technologies include: energy efficiency technologies; low emission technologies; and renewable energy technologies.

- CEFC had investment commitments (deployed and contractually committed capital) of $5.95 billion as at 30 June 2020, of which:

What did we find?

- The CEFC has suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investments and for their ongoing management.

- The CEFC has met its legislative requirement to invest at least 50 per cent of funds into renewable technologies.

- The CEFC has not yet met either of the target medium to long term benchmark rates of return set by the Investment Mandate.

- The CEFC has largely effective risk management processes in place.

- The CEFC has facilitated increased funding into the clean energy sector, but the extent is unclear.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made eight recommendations to the CEFC.

- The CEFC agreed to seven recommendations.

35%

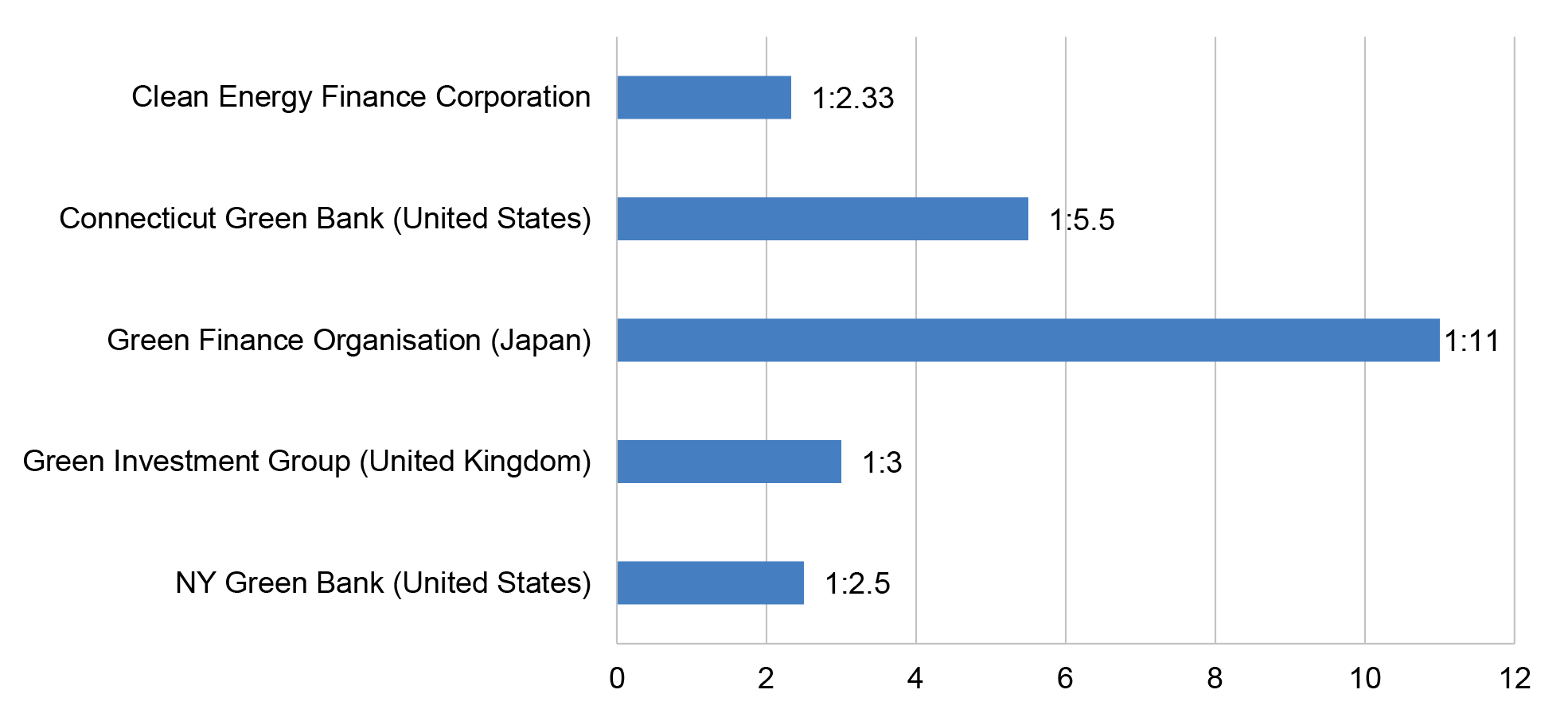

were in utilities

15%

were in commercial buildings

~77%

were in debt and the remaining 23% in equities

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) was established under the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 (CEFC Act) ‘to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector’ (section 3). It has been provided with access to $10 billion in capital through a special account, which is drawn down over time.

2. Section 58 of the CEFC Act states that the function of the CEFC is to invest, directly and indirectly, in clean energy technologies, which are defined in section 60 as:

- energy efficiency technologies;

- low emission technologies; and

- renewable energy technologies (under subsection 58(3), from 1 July 2018 at least half of the funds invested are to be in renewable energy technologies).

3. As at 30 June 2020, the CEFC had investment commitments (deployed and contractually committed capital) of $5.95 billion.

4. Section 64 of the CEFC Act provides for responsible Ministers1 to give the Board directions about the performance of the CEFC’s investment functions and the policies to be pursued. These directions together constitute the ‘Investment Mandate’. The current Investment Mandate (May 2020) requires the CEFC, among other things, to:

- target an average return (before operating expenses) of the five-year bond rate plus three to four per cent per annum over the medium to long term as the benchmark return of the Corporation’s core portfolio (section 7);

- in targeting this return and operating with a commercial approach, seek to develop a portfolio across the spectrum of clean energy technologies that in aggregate has an acceptable but not excessive level of risk (section 8);

- consider the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets and not act in a way that is likely to cause damage to the Australian Government’s reputation (section 12);

- include in its investment activities a focus on technologies and financial products as part of the development of a market for firming intermittent sources of renewable energy generation, as well as supporting emerging and innovative clean energy technologies (section 13); and

- make available funds for investment in clean energy projects and businesses through five nominated Funds and Programs (section 14).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of the CEFC’s selection of investments, including determination of an appropriate risk level and investment return. The audit also provides assurance over the ongoing management of the portfolio of funded projects, and the extent to which the CEFC is meeting its function of funding clean energy technologies through energy efficiency, low emission and renewable technologies.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit’s objective was to assess the effectiveness of the selection, contracting and ongoing management of investments by the CEFC and the extent to which the CEFC is meeting its legislated objective.

7. The following high level audit criteria were adopted:

- Does the CEFC have effective arrangements in place to assess potential investments and manage and report on the performance of its investments?

- Has the CEFC effectively met its objective under the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 consistent with legislative requirements and directions?

Conclusion

8. The CEFC has largely met its legislated objective of facilitating increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector, consistent with legislative requirements and directions.

9. The CEFC’s arrangements to manage and report on investments are largely suitable. There is a need for the CEFC’s policy statement to include more detail on its environmental, social and governance policies. There is an opportunity for the screening documents for new investments to specifically address all Investment Mandate requirements and for the CEFC to benchmark its performance in terms of clean energy outcomes and leverage against one or more other green banks.

10. The CEFC has not yet met the target benchmark rates of return set by the Investment Mandate and does not have a strategy in place to meet them. The CEFC also does not have a suitable measure of aggregate portfolio risk and the Board does not regularly record its assessment of the mandated requirement that the investment portfolio in aggregate has an acceptable but not excessive level of risk.

11. While the CEFC has facilitated increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector, the extent to which it has leveraged additional funds is unclear.

12. There is a lack of clarity in the Investment Mandate on whether CEFC investments in sustainable cities is restricted to the $1 billion limit for the Sustainable Cities Investment Program set by the Mandate.

Supporting findings

CEFC’s arrangements to monitor and report on its investments

13. The CEFC has suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investment opportunities. Its policy statement is broad and the section on environmental, social and governance policies does not adequately meet the requirements of section 16 of the Investment Mandate. There would be merit in the CEFC ensuring that all Investment Mandate obligations have been adequately considered in documentation for the assessment of new investment proposals.

14. The CEFC has implemented effective arrangements for sound contractual partnerships for new investment projects and for their ongoing management. Since inception the CEFC has not been involved in any legal cases.

15. The CEFC has appropriate arrangements in place to manage its investments. All investments are overseen by either the Asset Management Committee or the Joint Investment Committee. These committees receive regular reports on the progress of the investments and take action to respond to market changes or to ensure compliance with the CEFC Act. Reports are also provided to the Board for information and, where needed, decision. Reviews of relevant projects are undertaken annually to ensure that they remain compliant with the CEFC Act.

16. The CEFC has met its reporting requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the CEFC Act. There is scope to include other information to more fully inform users about the performance of the Corporation.

CEFC performance in meeting its legislative obligations

17. The CEFC has met the requirement in section 58 of the CEFC Act for at least 50 per cent of funds invested at one time to be in renewable energy technologies. It has also met its investment obligations under the Clean Energy Innovation Fund and the Reef Funding Program. However, CEFC investments in sustainable cities was $3.4 billion as at 30 June 2020, $2.4 billion more than the limit of $1 billion set in the Investment Mandate of funds to be made available for the Sustainable Cities Investment Program. There is a lack of clarity on the CEFC’s ability to invest more than $1 billion in sustainable cities as part of its core investments. There is also a need for the CEFC, when reporting on investments included in each fund or program, to include amounts that have been included in other funds or programs.

18. Since 2014–15 the CEFC has not yet met either of the two portfolio target benchmark return rates set by the Investment Mandate. The CEFC does not have a strategy in place to enable the mandated rates of return to be achieved over the medium to long term (10 years).

19. The CEFC should document its operating procedure for calculating the actual rates of return and ensure that the calculation spreadsheets include references to all source data.

20. The CEFC has partially effective risk management processes in place. It has yet to develop a satisfactory measure of portfolio value-at-risk and the Board also does not regularly record its assessments against the mandated requirement to develop a portfolio that in aggregate has an acceptable but not excessive level of risk.

21. The concessionality charge each financial year has been well below the limit of $300 million set in section 9 of the Investment Mandate and the CEFC has not exceeded the limits on guarantees specified in section 10 of the Investment Mandate.

22. There is evidence that the CEFC has facilitated increased levels of funds into the clean energy sector from the private sector and other sources, but the extent of these increased funds is unclear because the calculations of leverage both overstates some leveraged funds and does not include funds that may have been indirectly leveraged.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.16

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation develop a more comprehensive statement of its investment policies in regard to environmental, social and governance issues in order to meet the requirement of section 16 of the Investment Mandate.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.50

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation include in its annual performance statements a carbon abatement capital efficiency metric as an additional performance measure.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.70

To help decision-makers take account of all mandated requirements when assessing investment proposals, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation include in its screening documentation for all projects information on:

- specific consideration of the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets; and

- a comparison of the rate of return with the relevant benchmark average rate of return in the Investment Mandate.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: (a) Agreed; (b) Not Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 2.116

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation benchmark its performance in terms of clean energy outcomes and leverage against one or more other green banks.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 3.32

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation:

- ask responsible Ministers to clarify in the Investment Mandate the intention of the requirement in subsection 14(2) that the Clean Energy Finance Corporation make available up to $1 billion of investment finance over 10 years for the Sustainable Cities Investment Program; and

- in reporting on investments included in each fund or program, include amounts that have been included in other funds or programs.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 3.51

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation document procedures for calculation of benchmarks and actual rates of return against the benchmarks, and ensure that the calculation spreadsheets include references to all source data.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.7

Paragraph 3.64

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation keep responsible Ministers informed of action it is taking to meet the target rates of return and any concerns it has about its ability to achieve the target rates.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.8

Paragraph 3.103

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation:

- develop a metric that provides an aggregate estimate of risk capital at the portfolio level; and

- include in the quarterly Enterprise Risk Report a specific statement as to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation’s assessment of risk against the mandated requirement to develop a portfolio that in aggregate has an acceptable but not excessive level of risk.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation summary response

The CEFC welcomes the ANAO’s performance audit report on Investments by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (Report). The Report notes, amongst other things, that the CEFC has facilitated increased funding into the clean energy sector, and that the CEFC has suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investments and for their ongoing management. This is consistent with the conclusion reached also by Deloitte in conducting the 2018 Independent Statutory Review of the CEFC.

We accept all but one of the recommendations contained in the Report and their implementation will be overseen by the CEFC Board’s Audit and Risk Committee. The CEFC has already started to address a number of the items identified by the ANAO and we have benefited from discussions with the audit team throughout this process.

Regarding the one recommendation in the Report not accepted by the CEFC, the difference in opinion would appear to stem largely from differing approaches in the way we analyse investment returns on an individual versus portfolio basis. The portfolio benchmark return is defined in the Investment Mandate and then managed consistently on a portfolio basis, and it is our view that this is not an integral part of each individual investment decision. Individual investment decisions more appropriately reference the relevant market-equivalent rate of return and the maximum rate that can be achieved while still ensuring the appropriate public policy outcome.

Notwithstanding this one area in which we respectfully disagree, we are absolutely committed to implementing the ANAO’s recommendations, and to continuously improving the efficiency and effectiveness of our operations and governance arrangements.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) was established under the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 (CEFC Act) ‘to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector’ (section 3). It has been provided with access to $10 billion in capital through a special account.

1.2 Section 58 of the CEFC Act states that the function of CEFC is to invest, directly and indirectly, in clean energy technologies, which are defined in section 60 as:

- energy efficiency technologies;

- low emission technologies; and

- renewable energy technologies (under subsection 58(3), from 1 July 2018 at least half of the funds invested are to be in renewable energy technologies).2

1.3 The CEFC is prohibited from investing in technology for carbon capture and storage, nuclear technology and nuclear power.

1.4 As at 30 June 2020, the CEFC had investment commitments (deployed and contractually committed capital) of $5.95 billion. The breakdown of commitments by industry sector is shown at Figure 1.1. Most investments were in the utilities (35 per cent), commercial buildings (15 per cent) and other (15 per cent) sectors.

Figure 1.1: CEFC investment commitments by Industry sector as at 30 June 2020

Source: ANAO analysis of CEFC data.

1.5 Section 64 of the CEFC Act provides for responsible Ministers3 to give the Board directions about the performance of the CEFC’s investment function and the policies to be pursued. These directions together constitute the ‘Investment Mandate’.4 The current Investment Mandate (May 2020) requires the CEFC, among other things, to:

- target an average return (before operating expenses) of the five-year bond rate plus three to four per cent per annum over the medium to long term as the benchmark return of the Corporation’s core portfolio (section 7);

- in targeting this return and operating with a commercial approach, seek to develop a portfolio across the spectrum of clean energy technologies that in aggregate has an acceptable but not excessive level of risk (section 8);

- consider the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets and not act in a way that is likely to cause damage to the Australian Government’s reputation (section 12);

- include in its investment activities a focus on technologies and financial products as part of the development of a market for firming intermittent sources of renewable energy generation, as well as supporting emerging and innovative clean energy technologies (section 13); and

- outside of its ‘core’ investment activities, make available funds for investment in clean energy projects and businesses through five nominated Funds and Programs (section 14):

- the Clean Energy Innovation Fund (up to $200 million) where technologies have passed beyond the research and development stages but require start-up support;

- the Sustainable Cities Investment Program (up to $1 billion);

- the Reef Funding Program ($1 billion over 10 years to support delivery of the Reef 2050 Plan);

- from 2020, the Australian Recycling Investment Fund (up to $100 million over ten years); and

- from 2020, the Advancing Hydrogen Fund (up to $300 million in concessional finance).5

1.6 Section 13 of the Investment Mandate also encourages the CEFC, in supporting clean energy technologies, to prioritise investments that support the reliability and security of the electricity supply.

1.7 The CEFC’s role in facilitating investment in clean energy is summarised in its policy statement as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: CEFC’s investment role in transforming clean energy investment

Source: CEFC Investment Policies, February 2019, p. 12.

1.8 A statutory review of the CEFC, commissioned by the Department of the Environment and Energy and published in October 20186, found that:

- the CEFC had been effective in facilitating increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector projects it supported although, given the nature and relative immaturity of a number of projects it supported, it was difficult to measure the full impact of the CEFC’s involvement in the clean energy sector more broadly;

- the CEFC invests in different industries and sectors across the economy, but with a concentration of most of its investments in the energy, property and industrial sectors;

- in making investments in clean energy, the CEFC had tended to invest in lower risk financial instruments, including senior debt (debt that takes priority over other unsecured or otherwise more ‘junior’ debt owed by the issuer); and

- in 2016–17, the CEFC’s actual investment return and forecast lifetime investment return was 4.5 per cent and 5.4 per cent respectively, both below the target range of 5.8 per cent to 6.8 per cent.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.9 The CEFC was established in 2012 and an audit of CEFC’s investment program was included in the Australian National Audit Office’s Annual Audit Work Program 2019–20.

1.10 The audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of the CEFC’s selection of investments, including determination of an appropriate risk level and investment return. The audit also provides assurance over the ongoing management of the portfolio of funded projects, and the extent to which the CEFC is meeting its function of funding clean energy technologies through energy efficiency, low emission and renewable technologies.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The audit’s objective was to assess the effectiveness of the selection, contracting and ongoing management of investments by the CEFC and the extent to which the CEFC is meeting its legislated objective.

1.12 The following high level audit criteria were adopted:

- Does the CEFC have effective arrangements in place to assess potential investments and manage and report on the performance of its investments?

- Has the CEFC effectively met its objective under the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 consistent with legislative requirements and directions?

1.13 The audit examined the financial performance of the CEFC’s investment portfolio since its inception in 2012 and the CEFC’s selection and management of investments from 1 July 2017 to 31 December 2019.7 In relation to externally managed ‘green funds’ (aggregation programs maintained by other institutions designed to fund ecological/environmental projects) in which the CEFC has invested8, the audit did not examine individual investment decisions, but examined arrangements the CEFC has in place to manage risks associated with such investments.

Audit methodology

1.14 The audit methodology comprised:

- collection and analysis of CEFC documents on investment policies and strategies, consideration and approval or rejection of investment proposals and the ongoing management of its investments;

- analysis of a sample of 23 investments (informed by statistical analysis) approved from 1 July 2017 to 31 December 20199, stratified by type of clean energy technology, investment sector and investment instrument as to how well they have met the CEFC’s legislative requirements and obligations under the Investment Mandate. This included analysis of how the CEFC manages investments to achieve the targeted rate of investment return set by the Investment Mandate;

- analysis of potential investments from 1 July 2017 onwards that were under active consideration, but had not proceeded;

- analysis of the performance of the CEFC’s investment portfolio since its establishment in 2012;

- interviews with the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources and the Department of Finance;

- consideration of the statutory review of the CEFC’s investments and other relevant reviews, including internal audit reports, and the implementation of relevant recommendations or other actions taken to address their findings/conclusions; and

- interviews with CEFC staff.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $458,147.

1.16 The team members for this audit were Michael White and Resolution Consulting Services Pty Ltd.

2. Arrangements to manage and report on investments

Areas examined

This chapter assesses the effectiveness of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation’s (CEFC) arrangements to assess potential investments and report on the performance of investments once selected.

Conclusion

The CEFC’s arrangements to manage and report on investments are largely suitable. There is a need for the CEFC’s policy statement to include more detail on its environmental, social and governance policies. There is an opportunity for the screening documents for new investments to specifically address all Investment Mandate requirements and for the CEFC to benchmark its performance in terms of clean energy outcomes and leverage against one or more other green banks.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made four recommendations aimed at providing better assurance that Investment Mandate requirements have been met and improving performance reporting.

2.1 In assessing the effectiveness of the CEFC’s arrangements for selecting investments and reporting on their performance once selected, the audit examined whether the CEFC has:

- suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investment opportunities and enable it to meet its investment performance obligations;

- implemented sound contractual and other partnership arrangements for the selection and management of its investments;

- appropriate arrangements in place to manage its investments; and

- reported accurately on the financial and non-financial performance of its investments, including the relevant requirements under section 74 of the CEFC Act.

Does the CEFC have suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investment opportunities and enable it to meet its investment performance obligations?

The CEFC has suitable arrangements in place to assess and approve investment opportunities. Its policy statement is broad and the section on environmental, social and governance policies does not adequately meet the requirements of section 16 of the Investment Mandate. There would be merit in the CEFC ensuring that all Investment Mandate obligations have been adequately considered in documentation for the assessment of new investment proposals.

2.2 To review the effectiveness of the arrangements that the CEFC has implemented to assess and approve new investments and to enable it to meet its legislative and Investment Mandate obligations, the audit examined:

- the governance, policy and other arrangements in place; and

- the processes for the assessment of individual investment proposals using a sample of investments approved from 1 July 2017 to 31 December 2019.

Arrangements that the CEFC has in place to assess and approve investments

2.3 Arrangements to assess and approve investments include: the overall governance arrangements for assessing and approving and later managing investments; the CEFC’s investment policies and strategy; and arrangements to manage potential conflicts of interest.

Governance arrangements

2.4 Under section 16 of the Investment Mandate, the CEFC must have regard to ‘Australian best practice’ in determining its approach to corporate governance principles.10 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), which establishes rules for financial management and also for the broader governance, performance and accountability for the Commonwealth public sector, applies to the CEFC.

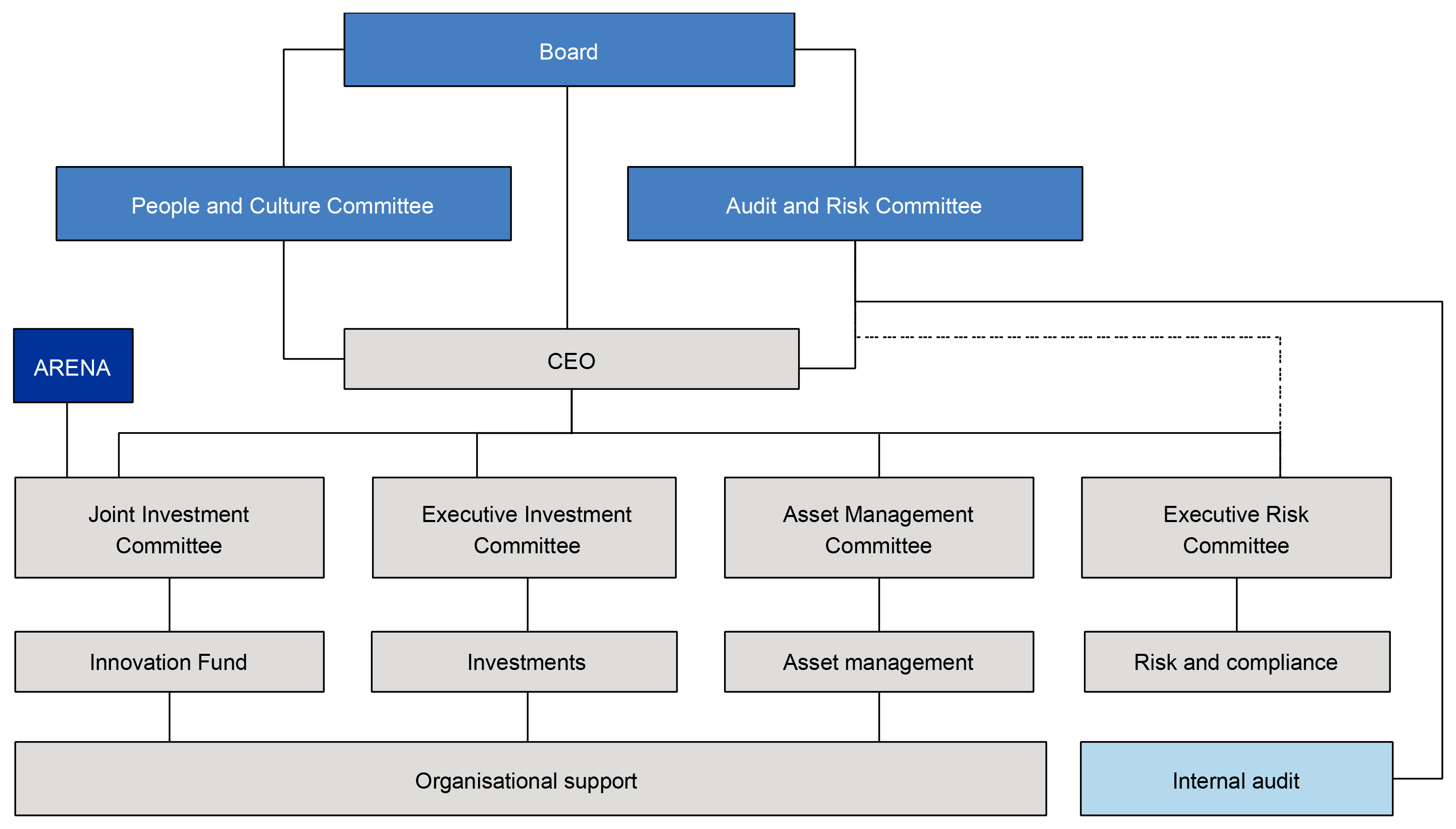

2.5 The CEFC’s governance structure is summarised in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: CEFC’s governance structure

Note: ARENA is the Australia Renewable Energy Agency, which is a separate Commonwealth entity.

Source: Based on CEFC internal data.

2.6 All proposed investments other than those relating to the Clean Energy Innovation Fund are reviewed by the Executive Investment Committee before they are submitted to the Board for consideration.

2.7 The Joint Investment Committee reviews proposals relating to the Clean Energy Innovation Fund. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), a separate Commonwealth entity, is represented on this committee, as the Innovation Fund sponsors may also receive grant funds from it. Once investments have reached financial close11, they are monitored and managed by the Asset Management Committee or, in the case of Clean Energy Innovation Fund investments, the Joint Investment Committee.

CEFC investment policies

2.8 Section 68 of the CEFC Act requires the CEFC to prepare and publish on its website policies on:

- its investment strategy;

- benchmarks and standards for assessing the performance of investments and of the CEFC itself; and

- risk management for CEFC’s investments and for the CEFC itself.

2.9 Section 16 of the Investment Mandate also requires the CEFC to develop policies with regard to environmental, social and governance issues.

2.10 The CEFC has formulated investment policies and published them on its website since 2013.12 The CEFC has also published separate complementary guidelines on complying investments under the CEFC Act, which provide more information on investments the CEFC is permitted to make.

2.11 The policy statement notes Investment Mandate requirements. It provides broad descriptions of the CEFC’s legislative, governance and risk management frameworks. It also includes a description of the CEFC’s investment strategy. The CEFC advised that the description of its investment strategy allows for different technologies and industry focuses to be adopted over time as technologies mature and become more commercial.

2.12 The policy statement only briefly mentions (on page 24) the section 16 requirement in the Investment Mandate for it to develop policies with regard to environmental, social and governance issues. It states that:

the CEFC will act as any prudent investor would in seeking to encourage the adoption of good governance practices within the CEFC itself as well as in the businesses and projects in which it invests.

2.13 It does not indicate what its policies are in relation to environmental, social and governance issues. The CEFC has advised that it does have a number of discrete policies/methodologies that cover different aspects of environmental, social and governance issues (for example, employment, work health and safety, modern slavery and carbon abatement).

2.14 Given the requirement in section 16 of the Investment Mandate for the CEFC to develop policies on environmental, social and governance risk management, a more comprehensive statement of its policies on these issues is required.

2.15 The CEFC has advised that it engaged a consultant in May 2020 to develop a more holistic consolidated environmental, social and governance policy.

Recommendation no.1

2.16 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation develop a more comprehensive statement of its investment policies in regard to environmental, social and governance issues in order to meet the requirement of section 16 of the Investment Mandate.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

2.17 The CEFC has a number of discrete policies/methodologies that ensure ESG considerations are taken into account, and which have been ingrained in our practices and reinforced by our corporate culture. The CEFC engaged a consultant in May 2020 (prior to this recommendation being received) to assist with the development of a more holistic consolidated ESG Policy. Development of this policy is under way and will be made publicly available on our website when complete.

CEFC investment strategy

2.18 The CEFC’s investment approach and strategy are summarised in the CEFC’s policy statement, corporate plan and strategic plan.

2.19 The current 2019–20 corporate plan covers the four financial years commencing on 1 July 2019 and ending on 30 June 2023. It summarises the CEFC’s investment approach and investment strategy13 at a high level.

2.20 The strategic plan covers the period 2018–19 to 2021–22. It lists a number of strategic themes, including:

- transitioning from transaction volume for scale to seeking greater emissions impact from new investments;

- having an enhanced focus on emissions reduction outcomes from the CEFC’s existing investments;

- supporting nationally significant energy infrastructure projects that underpin the energy transition; and

- supporting energy innovation businesses and venture capital market through the Clean Energy Innovation Fund.

2.21 The strategic plan forecasts a portfolio mix of investments in 2021−22 in which large scale solar, grid and storage will each comprise 23 per cent of the portfolio, property 20 per cent and infrastructure and transport 10 per cent.

2.22 While the strategic plan is at a relatively high level, detailed investment plans have been presented to the Board. For example, in October 2019, the CEFC outlined its renewable energy strategy for 2019–20. This included a selective approach to solar projects (one to two utility scale projects) addressing market gaps and attracting capital. It also included one to two wind deals and supporting early stage projects and specialist development companies to bridge gaps in development funding and facilitate the next wave of projects. Similar presentations were provided to the Board in November and December 2019 on the CEFC’s proposed property and listed equities strategies.

2.23 As noted at paragraph 1.2, subsection 58(3) of the CEFC Act requires the CEFC to ensure that at least half of its invested funds are in renewable energy technologies. The CEFC does not set targets for each of the other technology groups — energy efficiency and low emissions.

2.24 The corporate plan’s list of key performance indicators do not include the need for the CEFC to target the key mandated benchmark rates of return, which are set by the Investment Mandate and are expected to be met over the medium to long term. There is an opportunity for the CEFC to indicate in the corporate plan specific strategies to enable the target benchmark returns to be met. Performance against the target benchmark rates is considered further in Chapter 3.

Management of conflicts of interest

2.25 The CEFC has developed and implemented appropriate arrangements to manage potential conflicts of interest, including:

- a conflicts and material personal interests policy, which requires all CEFC officials to declare their personal interests and specifies arrangements to manage any conflicts. This includes reporting to the Audit and Risk Committee and the Executive Risk Committee how any material personal interest conflicts are being managed;

- a conflicts of interest register that records employees’ declared conflicts of interest and is kept up-to-date; and

- routinely requiring those attending Board or committee meetings to declare any potential conflicts of interest and, if necessary, to absent themselves from the meetings during consideration of any investment proposals for which there may be a potential conflict.

Assessment of individual investment proposals

2.26 To consider the CEFC’s process for assessing investment proposals, and how well it assesses proposals against its obligations in the CEFC Act and Investment Mandate, a randomly selected sample of investments that were approved between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2019 was examined. These were stratified to enable a range of clean energy technologies, investment instruments, sectors and locations to be examined. There were 23 investments in the sample.

Process for assessing investment proposals

2.27 The investment lifecycle, including the process for considering investment proposals, is depicted in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Investment lifecycle

Source: CEFC.

2.28 Investment opportunities can arise in different ways. These include direct approaches from clean energy investment sponsors (such as clean energy technology companies, manufacturers, financial institutions, property developers, state and local governments and universities), initiatives by the CEFC itself to help address gaps in the clean energy market and indirect responses to market offerings, such as bonds.

2.29 Since inception, a large number of potential investment opportunities have been recorded by the CEFC. Only a small proportion of these were selected and approved (174 out of 1414 or 12 per cent).14

2.30 Analysis of the 23 approved investments in the sample showed that they mainly resulted from:

- direct approaches from sponsors — 11 projects, where the CEFC committed $776.5 million;

- the CEFC working with investors to develop project proposals — seven projects, of which two were considered strategic projects for the CEFC, where the CEFC committed $453.7 million;

- flow-ons from joint work with ARENA — three projects, where the CEFC committed $138.5 million; and

- projects previously financed by the CEFC with the same sponsor — two projects, where the CEFC committed $93.6 million.15

2.31 The CEFC undertakes detailed assessments of investment opportunities that it evaluates as having merit. Where there is a need to obtain in-principle support for an investment proposal, an initial assessment of the proposal (a ‘pre-screen’ paper) is submitted to the Executive Investment Committee or the Joint Investment Committee. If endorsed, it is then submitted to the Board for consideration. Pre-screen reports were prepared for 19 of the 23 investments reviewed by the ANAO. Depending on the nature of the proposal:

- the Board may approve the proposal at the pre-screen stage, subject to further detailed analysis and consideration by the Executive Investment Committee or Joint Investment Committee (through a ‘detailed screen’ paper), and delegate final approval to the Chief Executive Officer (the Board is later briefed on the outcomes of these proposals); or

- await later receipt of the detailed screen paper.

2.32 For the 23 investments examined, the main reasons identified in the screening papers for supporting the projects (more than one reason can be advanced for a project) were:

- the clean energy merit of the project (level of carbon abatement, innovative or significant clean energy product, supporting energy from waste) — 16 projects;

- influencing other providers and industry (market influence, improved leverage and standard setting) — 12 projects;

- a need for the CEFC to be involved (CEFC assessment that the investment was too risky for the private sector alone, that CEFC investment is needed for co-lender involvement and accelerating project development) — 10 projects;

- support for sponsors and clients (strong previous relationship with client, supporting the CEFC’s relationship with key parties, the client’s wish to maintain its existing banking group, support for a green energy client in difficulty, working with state governments and universities and refinancing on current market terms) — 14 projects;

- CEFC portfolio issues (diversification of the investment portfolio, meeting the 50 per cent renewables target and support for a target Fund, such as the Clean Energy Innovation Fund) — seven projects; and

- other reasons (energy security and reliability, increased consumer awareness and knowledge and data sharing) — five projects.

2.33 Once approval is given to a proposal, the CEFC will prepare and conclude the necessary contractual documentation to proceed with (‘close’) the investment. After financial close16, progress in relation to all executed investments, except Clean Energy Innovation Fund investments for which the Joint Investment Committee has responsibility, is overseen by the Asset Management Committee (see paragraphs 2.85 to 2.104).

2.34 Governance arrangements implemented by the CEFC for management of its investments, including consideration of investment proposals, were appropriate. The CEFC Board and oversight committees have met regularly, and clear records of their meetings (including management of potential conflicts of interest) have been kept.

2.35 In January 2020, the Department of Finance published a Resource Management Guide on Commonwealth investments. The CEFC procedures are broadly consistent with the relevant principles in the Guide.

Consideration of performance obligations in assessment of individual investment proposals

2.36 The CEFC’s performance obligations are set out in the CEFC Act and Investment Mandate. The Investment Mandate reflects the requirements of the responsible Ministers and includes matters that the CEFC must follow as well as other matters that the CEFC is encouraged to pursue in its investments. 17

Complying investments

2.37 Under section 59 of the CEFC Act, the CEFC is only permitted to invest in ‘complying investments’, namely energy efficiency, low emission and renewable energy technologies. For the sample of 23 investments, the CEFC sought to ensure that the investments complied with section 59 of the CEFC Act mainly by:

- reviewing proposals at the outset to ensure that they will comply;

- working with investment sponsors to tailor projects or components of projects to requirements and requiring that the funds will only be used to invest in the specified complying purposes; and

- implementing arrangements, such as having a representative on the project’s board or funding committees or undertaking sample audits of aggregation programs, to provide continuing oversight.

2.38 The CEFC has suitable arrangements in place to confirm compliance with section 59 of the CEFC Act. Compliance analysis is initially completed at the pre-screen level and the General Counsel confirms compliance with section 59 of the CEFC Act. In the sample of 23 investments, all pre-screen papers included statements that the investments would comply with the CEFC Act and 21 of the 23 detailed screen papers also included such statements. The 23 investments examined in the sample complied with the CEFC Act.

2.39 The screening papers included analysis of compliance with section 59 of the CEFC Act.18 The CEFC advised that its practice, consistent with guidance issued by the Australian Institute of Company Directors and Governance Institute of Australia19, is only to record outcomes on an exception basis (that is, where the Board or committee has a concern about the certification in the screening documents) and where further work is needed. For this reason, the CEFC advised that the records of decisions of the Board, Executive Investment Committee and Joint Investment Committee do not routinely mention the Board’s or committee’s express satisfaction with this assessment.

2.40 Complying technology investment requirements are considered further at the portfolio level in Chapter 3 (paragraphs 3.3 to 3.12).

Carbon abatement

2.41 Under section 6 of the Investment Mandate, the CEFC should have regard to positive externalities and public policy outcomes when making investment decisions and when determining the extent of any concessionality.20 The screening documents typically include estimated reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2-e) in this context.

2.42 The CEFC’s estimates of reductions in CO2-e by projects take a consistent approach, the main features of which are:

- establishing a counterfactual case, estimating emissions under ‘Business As Usual’ (for instance, estimating emissions when electricity is made by the grid);

- identifying the reduction in emissions that would result from the proposed project (for a solar power project, the reduction would be compared with the CO2-e had the same amount of electricity come from the grid)21;

- summing the CO2-e saved over the life of the project (say, 25 or 30 years for a solar power project22); and

- reporting all the reductions from the project.23

2.43 The CEFC’s calculation methodology is based on industry practice (such as accounting for the gradual decline in emissions savings as the emissions intensity of the grid is forecast to decrease over time) and official published data (such as the national emission intensity conversion factors). Where the estimates rely on forecasts (such as forecast levels of electricity generation), the CEFC’s calculations are conservative (based on the most likely outcome) and subject to quality assurance of the estimated amount of energy generated (a key variable in the carbon abatement calculation) by a qualified externally contracted party.

2.44 The ANAO reviewed the calculations for carbon abatement outcomes for the 23 investments in the audit sample and concluded that the methodology and calculations for determining overall carbon abatement were sound.

2.45 The CEFC considers a range of measures (that is, not a single metric) to provide a balanced approach to achieving a cost effective outcome for carbon abatement.24 However, in its annual performance statements, it only reports the cost of carbon. This is a net cost of less than $0 and results in a net return to the CEFC per tonne of CO2-e abated.

2.46 The CEFC uses two methods to calculate the net cost of carbon per tonne of CO2-e abated, both of which produce similar results:

- cost to CEFC of investment (calculated as expenses and the cost of capital (based on the five-year government bond rate25) less investment income), divided by the lifetime tonnes CO2-e abated (Method A); and

- cost to CEFC of investment (calculated as expenses and drawdowns less repayments and applying a discount factor), divided by the lifetime tonnes CO2-e abated (Method B).

2.47 The CEFC also considers, but does not publish, a capital efficiency measure, which compares investments based on capital investment per tonne CO2-e abated (that is, the upfront capital investment divided by the tonnes of carbon abated). There would be merit in also publishing performance against this measure, since this represents the opportunity cost of capital in terms of carbon abatement.

2.48 The following illustrates the results for two projects (Project Lafite, an equity investment of $85 million in a property investment fund, with an internal rate of return of 8.5 per cent and with around 38,000 lifetime tonnes CO2-e abated; and Project Coogee, a senior debt investment of $38 million in a wind farm with a return of 5.12 per cent and 8,222,072 lifetime tonnes CO2-e abated) using the cost of carbon measures and the capital efficiency.

- For Project Lafite the net cost is a negative value of around $1500 per tonne26, compared to a negative value of under $1.00 per tonne27 for Project Coogee. By this measure, Project Lafite has the higher financial return to the CEFC per tonne of carbon abatement. However, the CEFC advised that it favours a cost number closer to $0 while remaining negative (best carbon outcome for the return) rather than a higher negative number.

- For Project Lafite, the capital efficiency is over $2500 per tonne, compared to less than $5 per tonne for Project Coogee. By this measure, Project Coogee is the more capital efficient project for carbon abatement.

2.49 The carbon abatement estimated to be delivered by each of the key sectors of the CEFC’s investment portfolio as at 30 June 2020 is shown at Figure 2.3. Investments in wind and large scale solar projects have delivered lifetime CO2-e abatement of 78.44 and 58.58 megatonnes respectively, while a comparable commitment in property investments has produced 3.13 megatonnes of carbon abatement.

Figure 2.3: Lifetime carbon abatement by commitment amounts for key industry sectors, 30 June 2020

Note: The horizontal axis is logarithmic to encompass the very wide range of carbon abatement.

Source: ANAO analysis of CEFC data.

Recommendation no.2

2.50 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation include in its annual performance statements a carbon abatement capital efficiency metric as an additional performance measure.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: Agreed.

2.51 The CEFC agrees that there is merit in including in its annual performance statements a carbon abatement capital efficiency metric as an additional performance measure. A capital efficiency metric can be useful in comparing investment efficiency within specific industry sectors or technologies (e.g. property, or large-scale solar PV). It will be difficult to establish a meaningful target or single capital efficiency measure at the corporate whole-of-portfolio level as different sectors, technologies and financial asset classes have inherently different levels of capital intensity required to achieve the necessary carbon abatement, so we will look to report this on an appropriate segmented basis.

2.52 The CEFC has been established to facilitate increased financial flows to the clean energy sector and this is achieved by providing capital to economically viable projects that often suffer only from a lack of available capital. Therefore, caution must be employed when comparing capital efficiency across projects, technologies, between sectors and across different time periods. It would be inappropriate to simply conclude, for example, that projects requiring the least amount of capital per tonne of CO2-e should be favoured. Similarly, a capital efficiency metric needs to be interpreted in the context of other metrics such as the (negative) cost of carbon, as the CEFC is required to achieve a positive return on its investment and recover its investment capital.

Other externalities and public policy benefits

2.53 In addition to potential CO2-e abatement outcomes, CEFC screening documents frequently tabulate other potential externalities and public policy outcomes under the heading ‘Externalities/Public Policy Benefits’.

2.54 For example, the screening documents for a proposal to build facilities to a standard that would significantly reduce energy use and CO2-e included the benefits of demonstrating that the CEFC was a viable lender, as well as those of geographically extending the CEFC’s activities:

Investment in this Project would establish CEFC as a viable lender in concession based project finance transactions in this sector. The Project would be a strong precedent to pave the way for other similar student accommodation projects and their related energy efficiency/renewable outcomes.

There has been limited CEFC investment in the built environment in Western Australia. This Project is a significant investment amount, across multiple mixed use assets in a master planned site for WA’s largest university which will build CEFC’s profile in WA and the University Sector.

2.55 While the detailed screenings documents provided to the CEFC Board and decision-makers present a range of financial, environmental and other externalities for consideration prior to making investment decisions, it is unclear what consideration is given to these factors in decisions. There would be merit in recording this in decisions.

Financial outcomes

2.56 Section 6 of the Investment Mandate states that the CEFC should apply commercial rigour when making its investment decisions. The Mandate also provides that the CEFC is to target specified benchmark rates of return for its core portfolio (section 7), the Clean Energy Innovation Fund and the Advancing Hydrogen Fund (section 14).

2.57 For each of the investment projects examined, detailed screening reviews were prepared. The financial considerations focused primarily on the form of the CEFC investment (for example, equity or loan), other investors in the project, investment risk and risk mitigating strategies and the terms of the investment (for example, interest rate of loans). The business case presented in the screening documents is detailed and provides evidence of the application of commercial rigour in the assessment of proposals.

2.58 In considering investments, the CEFC has regard to market rates (for example, rates being offered by other lenders for loans with comparable terms and conditions) and rates it has offered on comparable projects. It does not consider how the expected return compares to the benchmark target average rates of return for the core portfolio, Clean Energy Innovation Fund and Advancing Hydrogen Fund.

2.59 Performance against these targets is only reviewed at the whole-of-portfolio level (assessed in Chapter 3) and it is acknowledged that simply because an individual transaction’s financing rate is lower than the benchmark, this is not an indication that the CEFC should not participate. Nonetheless there would be merit in also including in the screening documents a comparison with the relevant mandated benchmark average rate of return and any implications for the Corporation’s ability to meet the target over the medium to long term. Where the benchmark rates of return cannot be achieved, but the clean energy outcomes justify proceeding with the investment, this can be documented.

Market impact

2.60 While adopting a commercial approach, the CEFC is also to apply Australian Industry Participation (AIP) Plans, where required, and consider the impacts of its investment strategy when making investments.

Australian Industry Participation Plans

2.61 Section 11 of the Investment Mandate requires the CEFC to apply AIP Plans to projects in which the Corporation invests in accordance with the Government’s AIP Plan policy. In June 2013, the CEFC developed a protocol on the application of AIP Plans to CEFC investment projects, in consultation with the Australian Industry Participation Authority.28 This protocol has been updated periodically, with the latest on 1 April 2019. Under the protocol, AIP Plans are only required for certain projects (as detailed in the protocol) involving CEFC financing of $20 million or more.

2.62 As part of its closure procedures of investment projects, there is a sign-off of AIP Plan requirements. This process is managed by the CEFC’s legal team. AIP Plan Implementation Reports are provided to the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources for applicable projects.

2.63 The CEFC has efficiently implemented the protocols for the application of AIP Plans to investment projects. However, it is not usually clear from the screening documents whether an AIP Plan will apply to a project. In only three of the 23 projects examined was there any mention of AIP Plans. The CEFC could consider including information in screening documents on the application of the AIP Plans protocol to the proposed investment so that decision-makers are aware of whether the investment would need to comply with the policy and any implications for the implementation or cost of the project.

Other market participants and the operation of the Australian financial and energy markets

2.64 Section 12 of the Mandate requires the CEFC to ‘consider the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets’ when considering investment proposals.29 It must also ‘not act in a way that is likely to cause damage to the Australian Government’s reputation’.

2.65 While the screening documents include a ‘Rationale’ section, which lists reasons for CEFC involvement, they do not include specific consideration of the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets. Specific consideration of these issues in the screening papers would provide a clearer consideration of the obligation in section 12 of the Mandate.

2.66 Assessing the potential effect on other market participants also involves examination of the need for the CEFC to be involved. Some of these factors are listed at paragraph 2.32. As set out in that paragraph, in the 23 investments examined there were 10 where the rationale included reasons (too risky for the private sector alone, CEFC needed for co-lender involvement and accelerating project development) that the project may not proceed, or not proceed as quickly, without CEFC involvement.

2.67 The need for involvement is reasonably clear where the CEFC has been approached by an investor who has first approached other financial institutions or where the CEFC is endeavouring to fill a gap in the market. In other cases, the CEFC may support an investment because of the demonstration effect on the market and so influence decision-makers to achieve higher rates of carbon abatement or other outcomes, such as where CEFC involvement would accelerate the commencement of a project, and where benefits might include earlier reductions in CO2-e.

2.68 Examples of investments in the audit sample that would not have occurred without CEFC involvement include:

- Project Nebula, a large-scale solar farm in New South Wales, and Project Firestar, a solar farm in Victoria, where the commercial banking sector was unwilling to invest because power purchasing agreements had not yet been negotiated; and

- Project Coogee, a wind farm in New South Wales, where CEFC involvement was needed to attract co-lender involvement.

2.69 Project Firestar arose from a joint initiative of the CEFC and ARENA. Under this initiative, called Project Alceste, ARENA conducted a competitive round of up to $100 million in grant funding to successful applicants for large-scale solar projects as part of its Advancing Renewables Program and the CEFC agreed to provide secured debt to the successful developers. Some projects, such as Firestar, were unsuccessful in obtaining grant funding from ARENA, but still proceeded with debt finance provided by the CEFC. The CEFC’s assessment of the Firestar project indicated that it would not have proceeded without the CEFC at the time.30

Recommendation no.3

2.70 To help decision-makers take account of all mandated requirements when assessing investment proposals, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation include in its screening documentation for all projects:

- specific consideration of the potential effect on other market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets; and

- a comparison of the rate of return with the relevant benchmark average rate of return in the Investment Mandate.

Clean Energy Finance Corporation response: (a) Agreed; (b) Not Agreed.

Response to (a)

2.71 For each investment (either debt or equity), the CEFC does consider the need for CEFC involvement, the potential effect on other relevant market participants and the potential impact on the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets under the heading “Investment Rationale”. However, we agree that this could be made more explicit within our screening papers.

2.72 The impact on other relevant market participants and the efficient operation of the Australian financial and energy markets, is often best measured on an aggregate business platform, industry or portfolio basis rather than for each individual transaction.

2.73 The CEFC does not participate in transactions if it will lead to the exclusion of willing potential investors. This is manifest in the CEFC’s fundamental principle of “crowding in” not “crowding out”. Part of our investment rationale is our willingness to go first and trust that a successful initial investment will then encourage follow-on investment from other market participants. It is worthy of note that in its 2018 statutory review, Deloitte concluded (refer p.19) “…that the risk of CEFC crowding out private sector finance is minimal.”.

Response to (b)

2.74 The Portfolio Benchmark Return as specified in the Investment Mandate is a “portfolio” metric and not an “investment by investment” metric. This is fundamental to ensuring an appropriate risk weighted and balanced portfolio can be established and maintained.

2.75 Individual transactions are most appropriately benchmarked against the relevant market-based rates of return in view of their specific characteristics and private sector risk appetite – commensurate with standard market practice and commercial rigour. Simply because an individual transaction’s financing rate is lower than the benchmark is not an indication that the CEFC should not participate, as the object of the CEFC is to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector. The financing rate reflects the risk of an investment and, in some markets, undertaking a risk that warrants pricing that matches the benchmark return often assumes a level of risk that is non-commercial and either out-of-market or outside of the CEFC’s stated risk appetite.

Has the CEFC implemented sound contractual and other partnership arrangements for the selection and management of its investments?

The CEFC has implemented effective arrangements for sound contractual partnerships for new investment projects and for their ongoing management. Since inception the CEFC has not been involved in any legal cases.

2.76 This section of the audit focused on the effectiveness of the contracting arrangements from the time a proposal is selected for investment through to financial close (that is, when all conditions have been satisfied, documents have been settled and draw-downs are permissible). Following that, the audit reviewed the management of investment obligations through to the repayment of a loan or equity divestment. It did not include technical legal analysis of the specific clauses and content of the contractual documentation.

2.77 The CEFC has a General Counsel who manages an internal legal team and engages external legal advice as required. The internal legal team works with the deal team to financial close and to ensure the commercial terms negotiated with the counterparties meet the CEFC’s requirements and the CEFC’s standard terms are documented in the contract. It also provides appropriate legal support to the Asset Management Committee and the Portfolio Management team as and when required throughout the life of an investment.

2.78 Each investment made by the CEFC is bespoke. CEFC contractual documentation varies depending on the investment type and the obligations of the investment sponsor.

2.79 For example, equity investments typically follow the form of documents prepared by the issuer or its counsel, whereas debt documents will vary depending on whether the facilities are bilateral, syndicated, secured, unsecured, senior debt or subordinated debt and will depend on the nature of the facility.31 This can be contrasted to the ‘high volume, low value’ transactional work undertaken by the commercial banking sector which typically uses a standard suite of contractual documentation.

2.80 There can be large numbers of contract documents, and significant numbers of contract variations after execution of a project to address issues that arise during the course of a project. For instance, as at October 2019, there were 88 executed documents for Project Coogee, a wind farm in New South Wales.

2.81 Contractual documentation for the aggregation platform32 is typically limited to a program agreement. This sets out the framework under which the CEFC will invest in bonds or other debt instruments issued by the financial institution responsible for the program to provide the necessary capital for investment in clean energy technologies and the conditions on which the CEFC will make that investment.

2.82 Contractual documentation for equity investments varies on a case-by-case basis. It typically involves a form of subscription agreement under which the CEFC agrees to subscribe to certain equities and a side letter that sets out CEFC specific conditions to its investment being made. Investments in companies may be subject to a form of shareholders agreement, which regulates the relationship between shareholders or, in the case of an investment in a fund, a trust deed which sets out the terms of the trust in which the CEFC may hold units or shares as a beneficial owner.

2.83 In addition to contractual documentation for the CEFC investment, the CEFC may maintain a range of other contractual documentation that provides important supporting information. For example, the key project contracts for a large scale solar project may cover:

- engineering, procurement and construction of the solar farms;

- operation and maintenance of the solar farm;

- where ARENA is also involved, an ARENA Funding Agreement;

- an Asset Management Agreement to manage the day to day operations; and

- a Power Purchase Agreement.33

2.84 The CEFC maintains two contract records management systems—the Contractual Rights and Obligations Management system (CROMs) and the Contract Management System (CMS). CROMs assists the CEFC in ensuring that the terms of the contract are regularly reviewed and the counterparty fulfils those terms at the agreed time, location, standard and the price.34 The CMS supports the record keeping of contractual documentation, which is stored electronically on a secure database, to which there is restricted access.

Does the CEFC have appropriate arrangements in place to manage its investments?

The CEFC has appropriate arrangements in place to manage its investments. All investments are overseen by either the Asset Management Committee or the Joint Investment Committee. These committees receive regular reports on the progress of the investments and take action to respond to market changes or to ensure compliance with the CEFC Act. Reports are also provided to the Board for information and, where needed, decision. Reviews of relevant projects are undertaken annually to ensure that they remain compliant with the CEFC Act.

2.85 In assessing the arrangements that the CEFC has in place to manage investments, ANAO examined asset management responsibilities, the CEFC’s asset management framework and monitoring and reporting on investments.

Asset management responsibilities

2.86 Portfolio management activity is reported to the Joint Investment Committee for Innovation Fund investments and to the Asset Management Committee for all other investments and ultimately, to the CEFC Board. Both the Asset Management Committee and Joint Investment Committee meet on a monthly basis.

2.87 Each executed investment is allocated a dedicated portfolio manager (and secondary manager). The Portfolio Management team works closely with the Investment team up until financial close and liaises as needed after financial close and throughout the investment period. Contractual obligations are recorded in CROMs35, which enables a quarterly reminder to be sent to the Portfolio Management team alerting it to the contractual obligations that are due in the coming 90 days. The team then provides reminders to borrowers of the impending deadlines.

2.88 The key focus areas of each portfolio manager vary depending on the nature of the investments. For example, project finance projects have a high level of focus on the construction phase (that is, cost and time to complete) and formal sign-off on power purchase agreements, and the debt/equity funding required to achieve the key milestones.

2.89 Investment funds, green bonds and aggregation loans to major banks have a lower credit risk exposure.36 The focus with aggregation programs is on monitoring compliance of the issued loans with the eligibility criteria stated in program agreements. Equity investments are monitored more closely with more detailed and frequent reporting requirements. Innovation fund investments are generally rated as higher risk due to being classified as venture capital and are managed by the Innovation team.

Asset Management Framework

2.90 The key aspects of the CEFC’s asset management framework for all investments where relevant include:

- analysis of business plans and strategies and challenging the direction/approach where appropriate;

- preparation of asset management plans37;

- analysis of risks and opportunities;

- monitoring progress and reporting on performance of the investment and compliance with/progress on a counterparty’s sustainability commitments or obligations (where relevant);

- reporting to the Asset Management Committee, Joint Investment Committee and Board, including requesting necessary approvals;

- financial reporting and analysis;

- capital management strategies; and

- monitoring contractual obligations.

2.91 Portfolio management of debt finance investments focuses on the governance and compliance processes associated with the contractual obligations. The main areas of focus are ensuring that payments are made in accordance with the interest and debt repayment schedules and that the borrower meets the reporting requirements.

2.92 Indirect investments such as investment funds, green bonds and aggregation loans are monitored regularly.38 Aggregation programs focus on monitoring compliance of the issued loans with the eligibility criteria stated in program agreements (which is based on technical and compliance reviews conducted by an independent third party39) and monthly compliance reports from the banks.

2.93 Equity investments40 have a higher risk profile and are monitored more closely with more detailed and frequent reporting requirements than debt finance and indirect investments. The CEFC monitors the overall business performance of the investment including, profitability, liquidity and solvency.

2.94 Under its Valuation Policy, the CEFC undertakes or procures the valuation of direct equity investments41 that it manages. Equity interests (direct or indirect) that are managed by third party investment managers are subject to the specific manager’s valuation policy (although the CEFC does undertake analysis and assess the performance of these other investments). According to the CEFC’s Valuation Policy, the valuation of equity investments should consider the nature and outlook for the industry, maturity of the underlying assets, current market conditions, quality, reliability and availability of the source data and assumptions. This approach also applies to the Clean Energy Innovation Fund’s equity investments.42

2.95 A review of the acquisition financial model for Project Mistral was undertaken to ensure that the model aligned to the CEFC Valuation Policy.43 The spreadsheet-based model was accurate, robust and repeatable, and included reasonable assumptions. However, the model could be enhanced by documenting or referencing the methodology, formal review and approval procedures, change logs and a control sheet (section 4.2 of the Valuation Policy).

2.96 Asset Management Plans aim to provide a holistic overview of equity investments and inform the allocation of the CEFC’s asset management resources.44 The plans are initially developed by the Portfolio Management team with input from the Investment team responsible for originating and executing the transaction. The plans assist the teams to better understand the nature of the CEFC’s investments, how the profiles change over time and industry developments, and facilitate the proactive management of the CEFC’s investments.

Monitoring and reporting on investments

2.97 The Asset Management Committee receives a comprehensive suite of monthly/quarterly reports. These include:

- two portfolio level reports — portfolio commitment dashboard reports and portfolio investment quarterly reports;

- quarterly sustainability performance reports;

- performance rating reports — each investment is given a Performance Rating (PR) and any changes in the status of investments and analysis of the underperforming investments are reported to the Asset Management Committee for consideration;

- monthly updates on the progress of investments (such as wind and solar power generating facilities) under construction; and

- progress reports on approved projects under the aggregation partnership programs that have reached financial close.

2.98 Regular financial update reports are also provided to the Audit and Risk Committee and the Board. These provide financial analysis of revenue, expenditure, operating results, retained earnings, portfolio benchmark returns, and special account and portfolio investment assets by product line and business platform.

2.99 Each investment is reported on to the Asset Management Committee separately at least annually, with updates included in the other reports.45

2.100 Consent and waiver requests are assessed and negotiated by the responsible portfolio manager or Innovation Fund lead with the decisions being made in accordance with the relevant debt and equity and fund portfolio management authorisations and the Innovation Fund authorisations. Most reported contractual breaches relate to reporting requirements, with few financial breaches and a low level of write-offs to date.

2.101 The minutes of Asset Management Committee meetings record any approved corrective actions for an investment that are approved by that committee.46

2.102 The Chief Asset Management Officer is responsible for determining the approach for managing the portfolio, including reducing the level of investment or exiting the investment. Much of the CEFC senior debt investments are still early within their period of legal tenor and equity investments are still maturing. Most investments have not yet reached the point where consideration of whether to refinance (by a counterparty) or sell down (by CEFC) an investment has been made for a number of reasons, most notably relating to the investment’s lifecycle.47

2.103 Financial analysis on the CEFC Special Account completed in September 2019 indicated that the CEFC was likely to be able to maintain current investment levels into the future without additional funding from government.48

2.104 The analysis indicated that the CEFC would have no less than $1.965 billion of headroom within the existing $10 billion appropriation at any point over the next five years, with no active recycling.49 The CEFC has developed a Capital Management Strategy which includes an option to recycle (sell) assets in order to maintain sufficient funds for investment.

Does the CEFC accurately report on the financial and non-financial performance of its investments, including the relevant requirements under section 74 of the Act?

The CEFC has met its reporting requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the CEFC Act. There is scope to include other information to more fully inform users about the performance of the Corporation.

2.105 The CEFC is expected to meet reporting requirements in both the PGPA Act and the CEFC Act. These requirements and the assessment of performance against them are considered here.

Reporting requirements

2.106 The Finance Secretary direction under subsection 36(3) of the PGPA Act sets out the requirements for performance information to be included in Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS)50, including a strategically focused set of high-level performance information.51 Section 39 of the PGPA Act requires Commonwealth entities to prepare annual performance statements and include those statements in their annual reports. Commonwealth entities are to report, through the annual performance statements, the extent they have fulfilled their purpose(s) as articulated at the beginning of a reporting year in their PBSs and corporate plans.

2.107 In addition to the requirements of the PGPA Act:

- paragraph 68(1)(b) of the CEFC Act requires an investment policy to define benchmarks and standards for assessing the performance of the investments and the CEFC itself;

- section 74 of the CEFC Act lists a number of matters that are to be included in the annual report; and

- section 15 of the Investment Mandate requires the CEFC, as part of its annual report, to report on the non-financial outcomes of all of its investments, including those for the nominated funds under section 14 of the Mandate.

2.108 As required by section 15 of the Investment Mandate Direction 2016 (No. 2), the CEFC, in consultation with the then Department of the Environment and Energy, agreed a range of performance indicators against which to report these non-financial outcomes, and advised the responsible Ministers of those indicators on 10 July 2017. This information is reported in the CEFC’s annual report.

2.109 The CEFC has met its reporting requirements under the PGPA Act and the CEFC Act, but there is scope to include other performance information to more fully inform users about the performance of the Corporation.

Annual performance statements

2.110 The CEFC provides a set of high-level performance information in the PBS. A comparison of the performance targets and reported information for 2018–19 was undertaken.52 They were found to be consistent, although the level of detail varies. There is an opportunity to add a supporting table reconciling the components of the CEFC’s investment portfolio to the total portfolio commitment value.53

CEFC legislative obligations and other key performance indicators

2.111 The CEFC reports on the matters required by section 74 of the CEFC Act. These include compliance with the 50 per cent renewable energy technologies requirement (discussed at paragraphs 3.6 to 3.12) and a benchmark comparison of operating costs and expenses. To meet the latter requirement, the CEFC provided a benchmark comparison against the Future Fund, Export Finance Australia and Northern Australia Investment Fund.54 The commentary explained the nature of each comparator and the differences between them, and provided horizontal analysis using a percentage comparison for each cost pool.

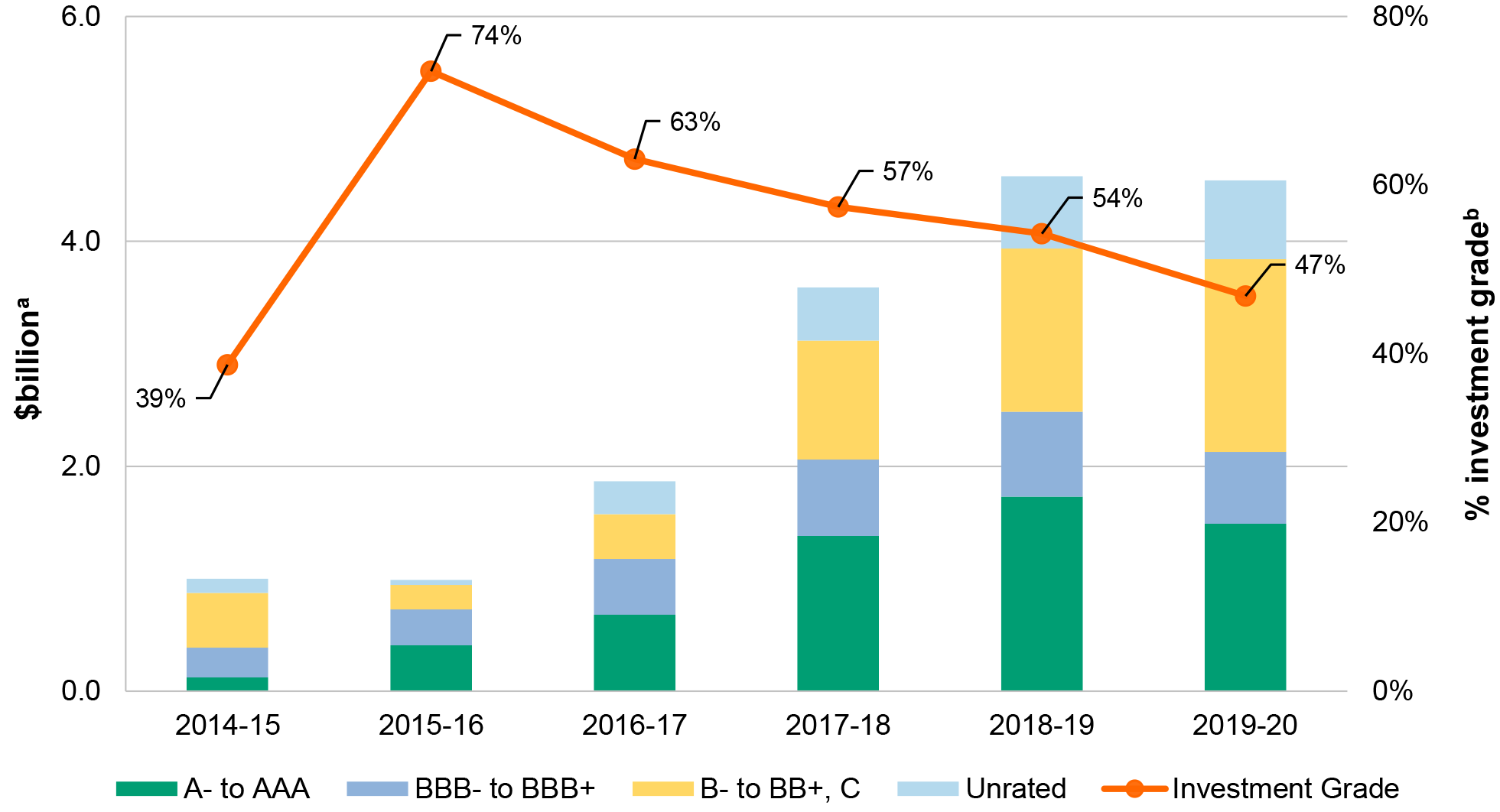

2.112 The CEFC has a single efficiency measure in its performance framework — operating expenditure as a percentage of the deployed portfolio balance. There is scope to include other measures, such as the time taken to close projects after approval. The average time to commitment per project has increased significantly from 189 days in 2012–13, 171 days in 2013–14, and 228 days in 2014–15 to 382 days in 2018–19.